ABSTRACT

Multi-source feedback is a ‘rare bird’ in higher education and yet recent research suggests multi-modal approaches to enhance university teachers’ academic development. This article reports a qualitative interview study using a social constructionist approach to explore the storylines and positions of university students and teachers when they participate in a formal ‘frontstage’ feedback process during facilitated multi-source feedback (the FMSF-model) as part of an academic development program. Our study showed that the FMSF-model disturbs hierarchical orders of rights and duties in feedback processes and constructs new positions related to providing feedback on university teachers’ professional work.

Introduction

Settings for feedback on teaching are numerous and range from ‘backstage’ informal conversations between a few trusted teachers (Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009; Thomson & Trigwell, Citation2018) to ‘frontstage’ conversations with students in classes (Cook-Sather, Citation2020), anonymous, written student ratings (Darwin, Citation2017), or peer-feedback conversations among teachers in academic development activities (Kraut et al., Citation2015; Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2015). Students’ and teachers’ conversations – oral and written, informal and formal – about teaching and learning are embedded in sociocultural contexts and understandings (Trowler, Citation2008) pertaining to being a ‘student’ and a ‘teacher’ in a ‘university’ at a certain point in time and in certain micro cultures (Mårtensson et al., Citation2014). Our aim is to advance the understanding of how students and teachers engage in feedback processes using the facilitated multi-source feedback model (Pedersen et al., Citation2020), which is an innovative and multi-modal academic development model for university teachers. More specifically, we explore how positioning (Harré & van Lagenhove, Citation1999) of university students and teachers is established and re-established during participation in facilitated multi-source feedback, which includes an integration of student and teacher voices in a formal feedback process.

Background

Student evaluations of teaching are criticized as being prone to measurement bias and equity bias (Kreitzer & Sweet-Cushman, Citation2021) and unreliable for assessing teacher competencies (Hornstein, Citation2017), and for being mono-source rating instruments primarily used for summative purposes, benchmarking and guiding decision-making without embracing the micro-culture and context of teachers’ pedagogical practice (Harrison et al., Citation2020; Tran, Citation2015). Without formative purposes, student evaluations seem to have a limited effect on teachers’ academic development (Darwin, Citation2017). As an alternative, many universities employ teacher-oriented conversations such as peer-to-peer feedback and peer observation to enhance the quality of teaching practice (Bell & Cooper, Citation2013; Dillon et al., Citation2020). A study on significant peer-to-peer conversations showed that these conversations are characterized by privacy and mutual trust among a few significant others, which is assumed to have a positive impact on the teacher’s academic development (Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009). Despite the potential benefits, there remain doubts about the quality of such conversations due to the informal and unsystematic format and the capacity of colleagues to provide useful feedback (Yiend et al., Citation2014). Consequently, it seems that the informal and unsystematic peer-to-peer conversations cannot stand alone in academic development strategies, but should be supplemented with formal and systematic conversations, where peer review practices are formally embedded in the organization culture and based on a range of integrated methods such as peer review, self-assessment and student evaluations. According to a recent meta-review (Harrison et al., Citation2020), such a multi-modal academic development approach, which includes both the teachers’ and the students’ voices, has a strong evidence base and a positive role in enhancing teaching quality in higher education. In the same vein, student-faculty partnerships are reported to have the potential to produce transformative learning experiences among teachers (Barrineau et al., Citation2016), to transform teaching and learning into shared responsibilities of faculty and students (Cook-Sather, Citation2014), and to contribute to the development of more equitable practices in higher education (Cook-Sather, Citation2020). Accordingly, we argue that the separation of students’ and teachers’ voices in the feedback to teachers may hinder the integration of knowledge and experiences from a range of agents and significant others, and consequently restrict the occurrence of academic development.

To integrate students’ and teachers’ voices in the formal and systematic conversations about teaching that are not possible with either student rating or informal peer conversations, we developed the facilitated multi-source feedback model (the FMSF-model). The development of the FMSF-model was inspired by the concept of multi-source feedback, but opposite to many multi-source feedback models, this model builds on principles of facilitated feedback (Sargeant et al., Citation2015) and is designed to provide formative and multi-modal feedback on a broad range of teachers’ professional work.

From 360° feedback to facilitated multi-source feedback

Multi-source feedback – so-called 360° feedback – provides a window into complex areas of performance in real workplace settings (Mackillop et al., Citation2011). 360° feedback is questionnaire-based anonymous feedback collected from multiple perspective groups in quantifiable form, designed to provide feedback about workplace performance to individuals. It is applied in human resources processes (Bracken & Rose, Citation2011) and in medical education (Ferguson et al., Citation2014) at individual, group and organizational levels, and considered valuable for both formative and summative evaluations as well as for performance improvement (Smither et al., Citation2005). 360° feedback is a well-known and valid way to measure professional behaviors and can lead to a perceived positive effect on practice (Saedon et al., Citation2012), enhance team-working, productivity, good communication and generate trust (Ferguson et al., Citation2014; Wood et al., Citation2006). Across many 360° feedback approaches, a general feature is that a number of colleagues and other significant agents in the workplace act as evaluators of an individual by filling out the same feedback form (often a questionnaire including narrative comments). Only some 360° feedback approaches facilitate the feedback from the questionnaire (Sargeant et al., Citation2015), but recent studies found that the facilitator is key to enhance acceptance and the formative use of the feedback, because the facilitated feedback supported a reflective process ensuring that strengths, weaknesses and potential development of the individual are focused on (Ferguson et al., Citation2014; Sargeant et al., Citation2015). Thus, the context-specific use of 360° feedback legitimate particular conversations about the development of professional practices. This means that the standards, norms and values of an organization are explicated in the 360° feedback, and therefore this feedback approach should always be tailored to a particular context and a particular purpose (McCarthy & Garavan, Citation2001). Higher education teaching cultures may differ considerably from the abovementioned disciplines and 360° feedback is a ‘rare bird’ in these cultures. In our search for literature on 360° feedback applied in academic development of higher education teachers, we found only one article (Berk, Citation2009). In the article, Berk (Citation2009) presented a complex multi-source feedback model, which included students, peers, self-ratings, videotaped recordings, and mentors as feedback providers for medical education faculty. However, the author did not report empirical findings, only that it was difficult to define the domain of ‘professional’ behaviors of medical education faculty and that the model may provide more fair and reliable decisions than the one based on just a single source.

The facilitated multi-source feedback model

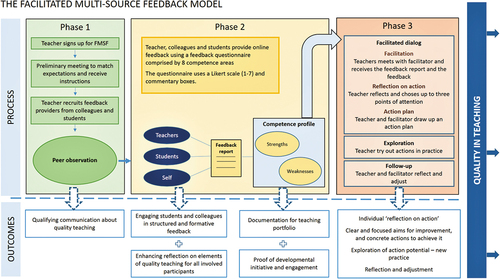

The FMSF-model (Pedersen et al., Citation2020) has a formative purpose; to support the potential of the individual teacher, and to enhance team effectiveness by allowing students’ and peers’ voices to be heard and by providing the teacher with a reflective point of departure for new directions in their academic development (see ). The iterative development of the model is described in detail in the supplemental file: Development of the FMSF-model.

First, the teacher (the feedback recipient) invites teacher colleagues and students (up to 14 feedback providers) to provide feedback and to engage in peer observation if possible. Secondly, the teacher, the recruited teacher colleagues and students all fill out an online questionnaire comprising narrative comments and eight pedagogical competence areas to be rated on a Likert scale (see supplemental file). Thirdly, a trained feedback facilitator generates a feedback report conveying the narrative comments and the ratings from the questionnaire, whereupon the teacher and the facilitator meet to talk about the report and about an action plan for further academic development (see supplemental file).

In the following, we report a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with teachers and students who participated in facilitated multi-source feedback. The aim is to understand the impact and effect of the FMSF-model on feedback processes among teachers and students in a specific higher education context.

Material and methods

Context

The context of the study was the Department of Public Health at a large public university in Denmark. Although the organizational structure of Danish universities is hierarchical, recent years have seen an enhanced focus on student-centeredness and building a democratic student environment. In addition, the need for high quality education has founded a political interest and demand for strategies to support pedagogical competence development of higher education teachers. Moreover, pedagogical competence development of higher education teachers is now pivotal to meet the accreditation requirements of universities.

Data and participants

We conducted semi-structured interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009) with 15 participants (two teachers, five colleagues, and eight students) who had completed the FSMF-model. Themes guiding the interview included the participants’ experiences of providing and receiving feedback through a FMSF process. Open questions encouraged rich and nuanced descriptions and enabled participants to introduce important dimensions within the themes. All participating teachers and students volunteered for the interview study, and in all transcribed interviews the participants were pseudonymous. We used the labels ‘Colleague’ for colleagues, ‘Self’ for teachers and ‘Students’ for students, and the numbers 1–8 to distinguish the interviewees during the analyses.

Data analyses

Our analytical strategy followed three analytical cycles (Charmaz, Citation2014). First, we read the first interview in each participant group – three in total – to explore participant views on the social episode of providing and receiving feedback when using the FMSF-model. All views on providing or receiving feedback were pinned, labelled, and finally categorized into clusters of themes. This process was iterative and undertaken in turns by the first and last author in order to prevent bias. This first cycle of coding resulted in a coding framework consisting of seven themes:

The teacher as a private practitioner

The student-teacher relationship

‘Good’ and ‘bad’ teachers

The lifelong learning process

The good colleague (providing and receiving feedback)

The role of direct observation

Teacher-colleague relationship

In the second cycle of coding, the first and last author read the 12 remaining interviews systematically to categorize the views on providing and receiving feedback within the coding framework, or to enhance the framework with new themes. No new themes emerged from the second cycle of coding.

The third cycle of our analysis was a theoretical reading of the material using Positioning Theory as an analytical framework. Positioning Theory is a social constructionist approach and an analytical tool for understanding intentional social interactions in specific social episodes (Harré & Moghaddam, Citation2003) under a local order of rights and duties (Harré & van Lagenhove, Citation1999). We found this framework suitable, as it allows for an analysis that captures the dynamics of conversations, e.g. changes in and negotiations of positions entailed by the FMSF-model. Previously, it has been used to analyze higher education activities and feedback conversations (see for example, Christensen et al., Citation2017). We used it to grasp the interactions surrounding the implementation of the FMSF-model and the conversations about feedback enabled by this new format. Positioning Theory has three core concepts: storyline, action (including speech acts), and position, known as the positioning triangle.

In this study, the process of providing and receiving facilitated multi-source feedback is a social episode. Social episodes do not develop randomly; they follow already established patterns of movement, so-called storylines. A storyline is defined as ‘what is to be expected in the episode being studied and comprise the conventions under which to make sense of the events that have been recorded and to express them in narrative’ (Harré & Moghaddam, Citation2003, p. 9). Several storylines may simultaneously be at work in the same episode and provide different positions among the participants in the social interaction. A position is associated with moral orders consisting of a cluster of rights and duties to perform certain actions, e.g. to say certain things or to keep something back. Any social environment has a range of positions that people may adopt, or be pushed into, or move away from, etc. (Harré & van Lagenhove, Citation1999). For example, in a conversation (an action) between a university teacher and a student the right to make certain remarks will be differently distributed, hence the conversation will involve two different positions and the storyline ‘student-teacher’. On this backdrop, all three authors undertook the theoretical reading of the themes identified in the first and second cycle coding. At this point, the themes were combined into storylines, positions, and speech acts in three overall clusters pertaining to the role of feedback (theme 1, 3, 5, and 6), the teacher-colleague relationship (theme 4 and 7), and the student-teacher relationship (theme 2). The storylines, positions and speech acts are highlighted with italics in the findings section.

Results

A key finding was that the FSMF-model changed the storylines and positions normally related to providing feedback on university teachers’ teaching. New kinds of distributions of rights and duties to perform certain speech acts in feedback conversations between university teachers, their colleagues, and students were seen.

Feedback: crossing boundaries or developmental support?

A storyline among students was that the university did not take any action regarding the reality of many students, namely that ‘students frequently meet bad teachers’. Because the teaching skills level varied so much, students welcomed the FMSF-model, as it would supposedly remedy this problem. They saw their own part in providing feedback as a contribution to such a process:

‘Also, because you meet many very bad teachers, so I think it is a good initiative to try to improve university teaching in general.’ (Student 1)

The key speech acts mentioned when both students and collegial participants reflected on why they accepted the invitation to provide feedback was ‘helping’ and ‘supporting’ the teacher in question:

‘I thought, that of course you want to help your colleagues, when they have appointed you to do it [provide feedback].’ (Colleague 2)

‘[The teacher] has expressed that she would like to develop and I would like to support that […] the advantage is to give something back and help […].’ (Student 8)

This displayed a storyline of ‘helper and teacher asking for help’ from the perspective of the feedback givers. By inviting colleagues and students to provide feedback, the teachers were perceived as positioning themselves as someone in need of help. The request for feedback facilitated the students’ and colleagues’ access to providing it, as helping and supporting seemed a more legitimate action for students and colleagues than taking the initiative to provide feedback without this request. In addition, it enabled the students not to hold back as the teacher had requested constructive criticism. The FSMF-model thus changed the speech acts normally related to providing feedback, seen as ‘crossing the boundaries of a teacher/colleague’ to ‘help a teacher with professional development’. However, the permission given by the teacher was pivotal, because it ascribed the students and colleagues a right and duty to provide feedback. In addition, the specific experience with the teacher played a role as to how easy it was to provide feedback varied according to how ‘good’ or ‘bad’ the teacher in question was perceived to be. The point here is that the students and colleagues spontaneously constructed a distinction between a ‘good’ teacher and a ‘bad’ teacher when they positioned themselves as feedback providers:

‘It also played a role that I find that X is a good teacher. I felt more like doing it than if I was asked by a mediocre or even bad teacher.’ (Student 6)

‘I think the reservation one has is that no one likes to say something bad. If I was [saying something critical], I would think that I ought to say it directly to the person instead of through a thing like this. […] I would feel that I went behind the person’s back […] I would prefer a one-to-one with the person.’ (Colleague 3)

Giving feedback to ‘bad teachers’ was thus a challenge, whereas providing feedback to ‘good teachers’ was less problematic. This was expressed as a general challenge that did not relate specifically to the model. However, the FMSF-model re-positioned the mode of communication from an informal conversation between colleagues where one could in private provide a bit of advice, to a more formal mode of communicating in writing. As seen in the quote, one-to-one informal conversations were perceived as a more suitable position for providing constructive criticism. In some ways, the model makes visible a pre-established norm. The quote illustrates that the colleague positioned herself as following the common norm that criticizing colleagues is going beyond one’s rights as a colleague (or student). Providing critical feedback was thus perceived as illegitimate. In addition, the anonymity imbedded in the positions of the FMSF-model created different types of positions between students and colleagues. In the quote above, providing negative feedback anonymously was regarded as somehow disloyal as a colleague, whereas students expressed that it gave them the opportunity to speak more freely.

The teacher-colleague relationship

Some storylines concerned the collegial relations and the manner in which the model reshaped how collegial conversations about teaching took place. The model created new opportunities, highlighted existing barriers and created new barriers. In general, the teachers saw themselves as per se interested in the development of their teaching skills, as witnessed in the following quote:

‘We are all teachers, and we want to teach as well as possible. We all know that everyone can develop and do better.’ (Colleague 1)

This self-positioning of university teachers expresses an ideal understanding of ‘who we are as teachers’, i.e. that as a member of the teacher community one is obligated to constantly look for ways of improving one’s teaching skills in a lifelong effort of developing them. Some expressed that using the FMSF-model facilitated this by creating new opportunities for academic development, because the formal way of organizing the feedback conversation forced the teachers to reflect on how to improve:

‘This [FMSF] was beneficial to me, because it forced me to stop and think about whether we could achieve more if we occasionally co-teached or paid more attention to each other’s doings.’ (Colleague 5)

This was echoed by the feedback-receiving teachers who found it highly rewarding to receive collegial feedback in this manner, as a means to engage in the ongoing refinement of their teaching skills:

‘It was nice to experience that people wanted to do that [provide feedback] for me, and it really was nice to receive the feedback that showed that I was not totally wrong about myself and the things I say and do. Of course, you can always improve things.’ (Self 1)

Thus, the model seemed to reinforce a storyline of ‘teachers as obligated to a never-ending search for development’, by creating a space for reflecting and sharing not normally seen in university practice. The model contributed to making this ideal a reality. This norm or ideal was explicitly expressed in the following quote:

‘Well, I feel it is almost like a public duty [to provide feedback]. When one of the younger [teachers] takes teaching seriously and wants to develop teaching competences, then of course you want to support that.’ (Colleague 1)

The speech act ‘to follow one’s duty’ to contribute to teachers’ development was explicitly observed here: teachers owe it to each other to provide feedback, and the model contributed to fulfilling this duty. However, the specific mentioning of the younger colleague provides a glimpse of the fact that hierarchy amongst colleagues played a role. The right to provide feedback was distributed differently across the hierarchy, which was mentioned by several teachers. One example was:

‘I have had many young co-workers with me, when I’m teaching – young colleagues whom I will ask to teach later on […] And it doesn’t bother me at all. But if it was some of my close colleagues, who is at the same academic level as I […], then I would think “no, what do they think about my teaching,” right? […] I think that would be crossing my boundaries.’ (Colleague 2)

The hierarchical structure mentioned in the above quote marked a difference between the right and duty to provide peer-feedback. The duty was evident when it concerned junior colleagues, though concerning same-level peers it was seen as problematic. This reservation was founded in a concern about the colleagues’ views on the academic content rather than a concern for their peer-feedback on didactics. The act was therefore not understood as providing feedback, but more like an academic assessment. As explicated by one colleague:

‘It’s a bit like an exam, isn’t it?’ (Colleague 2)

Being observed by colleagues at an equal level was thus conceived as somehow jeopardizing one’s position as an expert academic. Initiating an exam-like situation and thus a storyline of ‘examiner and assessed’ was seen as inappropriate between equal academics, and the colleague as violating personal rights. This was in contrast to the ideal storyline of teachers being obligated to always seek the opportunity to improve teaching. Thus, the model created new forms of opportunities, simultaneously with its highlighting of existing hierarchical structures and positions. The positions prompted by the FMSF model disturbed the existing hierarchy, because it entailed that all peers independent of their place in the hierarchy had the right to provide feedback, which also introduced new possibilities for conversation.

The transformation of the existing storyline concerning who has the right to provide feedback was seen as something that, despite being challenging, was worthwhile to use:

‘I think it would be a good idea [to expand the FMSF-model to include all of the university]. But I also told you that it would be crossing boundaries. It is something we would have to grow accustomed to, but actually I think we could learn something from it. As long as it is not used against us [laughs].’ (Colleague 2)

Being observed by fellow colleagues at an equal level entailed a potential risk of the feedback being used to harm as opposed to help the teacher in question, and thus a potential change of storyline. In addition, it was assumed that using the model would make the differences between teachers’ skills more visible, which would create an unpleasant atmosphere among colleagues.

The student-teacher relationship

Another positioning pattern concerned the students’ rights and duties to provide feedback to teachers about their teaching. A storyline among students was that ‘academic development of teachers do not involve the students in any direct way’. The students were used to filling out standardized course evaluations or offering their comments in class. Either way, the students were not attributed the competence to provide feedback to teachers on their teacher competence, and thus adopted the traditional, asymmetrical ‘student-teacher’ positioning pattern. From the students’ perspective, the FMSF-model is a novel feedback approach, requiring another kind of feedback:

‘[…] to participate in a thing like this, is just a little more than raising your hand in class to say that something is not working. […] I just think it seems more as if you have involved yourself in something’. (Student 1)

‘We normally fill out evaluation surveys during a course, but this is a more personal feedback.’ (Student 2)

The model seemed to expand the range of positions for students to adopt, requiring their involvement and dissolving the traditional student-teacher asymmetry by focusing the feedback on the teacher rather than the course. In such a manner, the FMSF-model not only facilitated new rights for the students, but also new duties to provide a focused feedback to one teacher.

From the students’ perspective, the new positioning opportunities had both some advantages and some disadvantages. An advantage was that the involvement and entrustment following the FMSF format empowered the students and motivated them to adopt a thorough and constructive approach. As explicated:

‘[Written feedback] can elaborate and support [the ratings] if it has been difficult to do them, and explain why you have rated the way you have. I think it is more constructive for the ones who are to receive the feedback.’ (Student 2)

‘It is good to be able to provide some pointers at the end of the questionnaire for what she could do to improve […].’ (Student 8)

The self-positioning of the students as ‘constructive reviewers’ was founded both in their wish to support their teachers’ development and in the anticipation that their voice would be considered actively in a development process:

‘I think this [FMSF] is great, because you know it will be used for something, whereas the course evaluations are a little … you know, “what happened with it?” […] this is different I think because it relates to them personally.’ (Student 8)

The new approach to feedback also caused the students to reflect upon the relation between themselves and the teachers, and the didactic reciprocity within the learning situation:

‘The advantage [of FMSF] is definitely that you reflect upon the situation you are in, […] that is definitely constructive. You get to reflect on both the relation and the reciprocity of it all.’ (Student 2)

It seems that even though the feedback was facilitated by a questionnaire, the setup differed from the usual course evaluations in a way that not only leveled out some of the asymmetry in the student-teacher relation, but also provided the space for a more personal relation that is not present in a standardized survey. The new positioning pattern displays a storyline of ‘students as equally valuable to colleagues in formative feedback’. However, some of the students expressed ambivalence about the novel approach of being directly included in the teachers’ academic development process. Not only was the feedback centered around a person – the teacher – but it also singled out a few feedback-providing students, who by adopting the position of feedback provider placed themselves on the line in their efforts to help their teacher. Thus, some of the students expressed an uncertainty about how the teacher would perceive the feedback and whether the feedback provided would affect their student-teacher relationship:

‘The teacher might take it personal because it is not just a small in-class evaluation or a course evaluation with a 20% response rate.’ (Student 1)

‘I might have thought it to be a disadvantage, that if I said no to provide feedback it would maybe influence her approach to me as my master thesis supervisor.’ (Student 5)

The key speech acts when student reflected on the disadvantages of providing feedback was centered around the ‘personal risks’ of entering a new, more personal and symmetrical position that legitimized a critique which was not appropriate before. Moreover, a risk was seen in the right to decline the invitation, thereby not adopting to the ‘constructive reviewer’ position. In other words, the model’s multi-source format in itself obligated the students to position themselves as either a ‘constructive reviewer’ or an ‘uncooperative student’. Hence, it seemed that both accepting and declining the invitation to provide feedback posed a risk to the students because of the teachers’ superior position. By challenging the established storylines and conversational structures, the FMSF-model thus introduced ambiguity into the student-teacher relation.

From the teachers’ point of view, there were two differing attitudes towards involving the students as feedback providers alongside colleagues. On the one hand, teachers welcomed the new approach, because they found the students’ perspectives key to their development:

‘I really wanted to hear from the students who were a little challenged with the subjects I teach. […] those are the ones I would like to help, and whom I lack the tools to help.’ (Self 2)

The teacher’s speech act here being ‘to help me help you’ underlines a view on teaching and learning as reciprocal and displays a collaborative student-teacher positioning pattern. On the other hand, teachers did not wish to swap places with the students and enter a new position as ‘learner’ instead of ‘teacher’:

‘I did not want to volunteer in this [FMSF] because I did not want to ask five students to evaluate me. […] I simply found that to be uncomfortable […] reversing the roles in a way … ’ (Colleague 3)

Not wanting to ‘reverse the roles’ displays the self-positioning of the teacher in the traditional, hierarchical ‘student-teacher’ positioning pattern, which validates the students’ hesitance to adopt the ‘constructive reviewer’s’ position.

Discussion

Some studies show that informal conversations help academics to develop their teaching (e.g. Thomson & Trigwell, Citation2018), but at the same time other studies recommend formal multi-source feedback processes as a way to enhance quality teaching (Harrison et al., Citation2020; Sargeant et al., Citation2015). Our study demonstrated a similar duality. On the one the hand, teachers and colleagues seemed to prefer the already established one-to-one informal conversations, which they regarded a more comfortable positioning of themselves, because they avert 1) exposing the teacher to the risk of feeling judged, or 2) reversing the roles among teachers and students. One could speculate that the distinct preference for this type of conversation reflects teachers’ need for preserving a secure and private space to discuss personal theories about teaching in the everyday life of academics, where most other aspects of academic work (research, applications for funding, student ratings, etc.) take place in a ‘frontstage’ public space (Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2009). However, the one-to-one informal conversations rely on significant others – or a microculture with high levels of trust and shared responsibility (Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2015) – and might thus exclude teachers with limited access to such social contexts. On the other hand, the findings from our study suggest that the formal structure of the FMSF-model acknowledges the need for a secure space (such as the facilitated feedback session) to discuss the feedback in relation to the teacher’s personal theories about teaching, but also paves the way for multiple voices in the conversation about teaching to participate. In this way, the FMSF-model disturbs this local order of rights and duties by introducing a more democratic manner of providing and receiving feedback by engaging students and colleagues as partners in the teachers learning.

A growing interest in student-faculty partnerships (Cook-Sather et al., Citation2014) indicates a movement towards the de-privatization of teaching where students and colleagues are invited to share experiences and participate in the development of a teacher’s pedagogical practice. Recent research also suggests that feedback partnerships (such as the FMSF-model) may carry the potential to develop staff and student feedback literacy (Carless, Citation2020). Our results showed that by using the FMSF-model some students could speak more freely while some colleagues felt disloyal and some appreciated the structured feedback approach. Therefore, the FMSF-model seemed to disclose diverse feedback cultures in the studied context and thus introduced reflections about how and why we engage in feedback processes.

Based on this study, we suggest the FMSF-model has the potential to complement existing academic development strategies such as collegial feedback (Bell & Cooper, Citation2013; Dillon et al., Citation2020), students-as-partners initiatives (Cook-Sather, Citation2014), and holistic teaching evaluation rubrics (Weaver et al., Citation2020). This is because it establishes a transparent and structured framework for involving colleagues and students in in-depth feedback to the teacher, which is not possible with either informal peer conversations or student ratings.

The FMSF-model is a rather resource demanding process and perhaps not suitable for large scale and often recurring feedback. Instead, it is well-suited for in-depth feedback on the multiple facets of a teacher’s pedagogical competences and thus an appropriate tool for teachers to underpin writing of different types of teaching portfolios (Smith & Tillema, Citation2003). Similar to the teaching portfolios, the FMSF-model is a step toward a more public, professional view of teaching as a scholarly activity. A recent study on the scholarship of teaching and learning through the writing of teaching portfolios (Pelger & Larsson, Citation2018) suggested that a reflective approach to teaching can be encouraged within the community of academic teaching practice if portfolio writing – accompanied by peer feedback – is integrated into teacher training courses. Likewise, we suggest to integrate the FMSF-model into teacher training courses with a focus on shared reflections on practice and preparation of teaching portfolios. However, further research is needed to outline the ways in which the FMSF-model may be integrated into academic development practices.

Limitations

This study has limitations. One is the relatively low number of participants due to the circumstance that the study was based on a piloting of the FMSF-model. To counterbalance this limitation, findings were thoroughly discussed between the investigators, and we recruited interviewees from all participant groups and thus ensured participant triangulation (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009). Other limitations are the lack of observation of the facilitated feedback session and lack of interview with the facilitator. These data could have strengthened the study’s reliability (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009).

Conclusion

Our aim of the study was to advance the understanding of how conversations among students and teachers are established and re-established during feedback processes using the FMSF-model. We found that the FMSF-model disturbs a local order of rights and duties in feedback processes in two distinct ways: By including students and colleagues as partners in providing feedback to teachers, it establishes a more democratic mode of conversation. However, the FMSF-model also challenges traditional hierarchical conversational structures and constructs new positions, which evokes conflicting emotions within the participating students and teachers. Consequently, we suggest that academic development practices such as the FMSF-model should include teachers’ and colleagues’ preparation for engaging in structured, formative feedback processes supported by a careful, trained facilitation of the feedback.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (256.8 KB)Disclosure statement

There is no known conflict of interest by any of the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.2016413

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mette K. Christensen

Mette K. Christensen Christensen is PhD and Associate Professor. Her expertise revolves around qualitative research and sociological aspects of academic development and situated learning, in particular in the fields of health sciences education and their professions.

Jane E. Møller

Jane E. Møller, PhD and Associate Professor. She works with qualitative methodology and her research on medical education contributes to gaining new understandings of how words work in educational practices.

Iris M. Pedersen

Iris M. Pedersen is MSc and Educational Consultant. She explores new models for academic development and holds a special interest in peer-feedback processes and their potential to aid reflection on teaching practice, and guide development.

References

- Barrineau, S., Schnaas, U., Engström, A., & Härlin, F. (2016). Breaking ground and building bridges: A critical reflection on student-faculty partnerships in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1120735

- Bell, M., & Cooper, P. (2013). Peer observation of teaching in university departments: A framework for implementation. International Journal for Academic Development, 18(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2011.633753

- Berk, R. A. (2009). Using the 360° multisource feedback model to evaluate teaching and professionalism. Medical Teacher, 31(12), 1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590802572775

- Bracken, D. W., & Rose, D. S. (2011). When does 360-degree feedback create behavior change? And how would we know it when it does? Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9218-5

- Carless, D. (2020). Longitudinal perspectives on students’ experiences of feedback: A need for teacher–student partnerships. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1684455

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Christensen, M. K., Henriksen, J., Thomsen, K. R., Lund, O., & Mørcke, A. M. (2017). Positioning health professional identity: On-campus training and work-based learning. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 7(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-01-2017-0004

- Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching. Jossey-Bass.

- Cook-Sather, A. (2014). Student-faculty partnership in explorations of pedagogical practice: A threshold concept in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(3), 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.805694

- Cook-Sather, A. (2020). Respecting voices: How the co-creation of teaching and learning can support academic staff, underrepresented students, and equitable practices. Higher Education, 79, 885–901. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00445-w

- Darwin, S. (2017). What contemporary work are student ratings actually doing in higher education? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.002

- Dillon, H., James, C., Prestholdt, T., Peterson, V., Salomone, S., & Anctil, E. (2020). Development of a formative peer observation protocol for STEM faculty reflection. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(3), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1645091

- Ferguson, J., Wakeling, J., & Bowie, P. (2014). Factors influencing the effectiveness of multisource feedback in improving the professional practice of medical doctors: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 14(76), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-76

- Harré, R., & Moghaddam, F. M. (Ed.). (2003). The self and others: Positioning individuals and groups in personal, political, and cultural contexts. Praeger.

- Harré, R., & van Lagenhove, L. (1999). Introducing positioning theory. In L. van Langehove (Ed.), Position theory: Moral contexts of intentional action (pp. 14–31). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Harrison, R., Meyer, L., Rawstorne, P., Razee, H., Chitkara, U., Mears, S., & Balasooriya, C. (2020). Evaluating and enhancing quality in higher education teaching practice: A meta- review. Studies in Higher Education. Published online 29 Feb 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1730315

- Hornstein, H. A. (2017). Student evaluations of teaching are an inadequate assessment tool for evaluating faculty performance. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1304016.https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1304016

- Kraut, A., Yarris, L. M., & Sargeant, J. (2015). Feedback: Cultivating a positive culture. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 7(2), 262–264. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-15-00103.1

- Kreitzer, R. J., & Sweet-Cushman, J. (2021). Evaluating student evaluations of teaching: A review of measurement and equity bias in SETs and recommendations for ethical reform. Journal of Academic Ethics, 1–12. Published online 09 Feb 2021 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09400-w

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Mackillop, L., Parker-Swift, J., & Crossley, J. (2011). Getting the questions right: Non-compound questions are more reliable than compound questions on matched multi-source feedback instruments. Medical Education, 45(8), 843–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03996.x

- Mårtensson, K., Roxå, T., & Stensaker, B. (2014). From quality assurance to quality practices: An investigation of strong microcultures in teaching and learning. Studies in Higher Education, 39(4), 534–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.709493

- Mårtensson, K., & Roxå, T. (2015). Academic development in a world of informal learning about teaching and student learning. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), 109–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1029736

- McCarthy, A. M., & Garavan, T. N. (2001). 360 degree feedback processes: Performance improvement and employee career development. Journal of European Industrial Training, 25(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590110380614

- Pedersen, I. M., Pedersen, K., Stentoft, D., & Christensen, M. K. (2020). Faciliteret Multi-Source Feedback som pædagogisk kompetenceudvikling – Et dansk casestudie [Facilitated multi-source feedback as educational development – A Danish case study]. Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift, 15 (28), 124–148. https://tidsskrift.dk/dut/article/view/115654

- Pelger, S., & Larsson, M. (2018). Advancement towards the scholarship of teaching and learning through the writing of teaching portfolios. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(3), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1435417

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks: Exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597200

- Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2015). Microcultures and informal learning: A heuristic guiding analysis of conditions for informal learning in local higher education workplaces. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1029929

- Saedon, H., Salleh, S., Balakrishnan, A., Imray, C. H., & Saedon, M. (2012). The role of feedback in improving the effectiveness of workplace based assessments: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 12(25), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-25

- Sargeant, J., Lockyer, J., Mann, K., Holmboe, E., Silver, I., Armson, H., Driessen, E., MacLeod, T., Yen, W., Ross, K., & Power, M. (2015). Facilitated reflective performance feedback: Developing an evidence-and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Academic Medicine, 90(12), 1698–1706. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000809

- Smith, K., & Tillema, H. (2003). Clarifying different types of portfolio use. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(6), 625–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293032000130252

- Smither, J. W., London, M., & Reilly, R. R. (2005). Does performance improve following multisource feedback? A theoretical model, meta-analysis and review of empirical findings. Personnel Psychology, 58(1), 33–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.514_1.x

- Thomson, K. E., & Trigwell, K. R. (2018). The role of informal conversations in developing university teaching? Studies in Higher Education, 43(9), 1536–1547. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1265498

- Tran, N. D. (2015). Reconceptualisation of approaches to teaching evaluation in higher education. Issues in Educational Research, 25(1), 50–61.

- Trowler, P. (2008). Cultures and change in higher education. Theories and practices. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Weaver, G. C., Austin, A. E., Greenhoot, A. F., & Finkelstein, N. D. (2020). Establishing a better approach for evaluating teaching: The TEval project. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 52(3), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2020.1745575

- Wood, L., Hassell, A., Whitehouse, A., Bullock, A., & Wall, D. (2006). A literature review of multi-source feedback systems within and without health services, leading to 10 tips for their successful design. Medical Teacher, 28(7), e185–e191. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600834286

- Yiend, J., Weller, S., & Kinchin, I. (2014). Peer observation of teaching: The interaction between peer review and developmental models of practice. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(4), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.726967