ABSTRACT

Moving to online teaching is an emotional experience for university educators. With increased demand for online learning, understanding emotions associated with this change is important so support can be provided. In a novel use of the Kübler-Ross model to illuminate educators’ emotions about transitioning online, this study analysed texts from a collaborative autoethnography and identified emotions associated with each stage. Loss was related to changed relationships with students, curriculum, and teaching practice. To assist staff to navigate and learn from change, institutions should foster dialogue that surfaces emotions, while harnessing educators’ commitment to student success as sources of excitement and hope.

Introduction

Changing teaching practice is difficult, yet seemingly overnight, COVID-19 saw university teachers globally forced to rapidly shift from face-to-face on-campus teaching to online delivery (Bellaby et al., Citation2020), highlighting the need for adaptability in these unprecedented and uncertain times. While COVID-19 has accelerated this shift to online and blended learning, this trend was already evident within the sector, resulting in increasing numbers of teachers transitioning to online teaching (Educause, Citation2021).

When teachers make the change from face-to-face (f2f) to online and blended learning (OBL) models, they are confronted with an alternative pedagogical environment (Regan et al., Citation2012) requiring a significant transformation in their teaching practice. Indeed, some authors have viewed teaching online as a threshold concept, being troublesome because it requires a deep transformation in understanding, often associated with passing through a liminal state of uncertainty (Meyer & Land, Citation2005). Being in this sometimes prolonged liminal state can produce emotional reactions including loss (Timmermans, Citation2010) that make the transition unsettling (Kilgour et al., Citation2019) and stressful (Hodges et al., Citation2020). Such emotions are likely to have been exacerbated by the pandemic as teachers reported greater stress, additional workloads, deteriorating work-life balance, and poor wellbeing during this time (Watermeyer et al., Citation2021).

Teachers’ emotional states influence their wellbeing, job satisfaction, retention, and risk of burnout, while also influencing teaching quality and student learning (Naylor & Nyanjom, Citation2020; Trigwell, Citation2012). Teachers’ emotions also impact academic developers who provide support during the shift to online teaching. Indeed, despite such support being a priority for academic developers during COVID-19 (Popovic, Citationn.d.), it is troubling that, at the same time, some academic developers bore the brunt of academics’ frustration and anxiety (Bellaby et al., Citation2020).

Despite the impact of teachers’ emotions, there are few frameworks (Badia et al., Citation2019) and empirical studies that focus on university teachers’ emotional experiences of online teaching (Naylor & Nyanjom, Citation2020), with Naylor and Nyanjom (Citation2020) calling for more research on the nature and significance of emotions, specifically during the transition to online teaching.

This research paper aims to illuminate the emotional experiences of transitioning to teaching online using the Kübler-Ross grief model (Citation1970). The Kübler-Ross model is valuable for studying emotional dimensions of change, as emotional responses to change are similar to grief (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). Conceptualising the emotional experience of transitioning to online teaching as a form of grief acknowledges the intensity of emotions felt by educators and provides both institutions and academic developers with a new language and alternative way to consider and work with educators during this critical time.

Background

The impact of educators’ emotions on academic developers

During COVID-19, the higher education sector shifted to online learning, with teachers pivoting rapidly to emergency remote teaching without the institutional coordination and leadership critical to the success of OBL approaches (Huang et al., Citation2021). During this time, some academic developers felt the brunt of educators’ heightened emotional reactions, feeling that they were ‘at the mercy of academics’ emotional responses to technical difficulties and shifting priorities’ (Bellaby et al., Citation2020, p. 152). Due to the close working relationship with academics during this transition, at times, academic developers also bore the ‘brunt of academics’ frustrations and anxiety’ (Bellaby et al., Citation2020, p. 152). Even before COVID-19, academic developers were likened to ‘shock absorbers’, cushioning the strain of educational change initiatives (Kolomitro et al., Citation2020, p. 5), such that they needed support so as not to suffer from ‘compassion fatigue’ (Kolomitro et al., Citation2020, p. 15). These working relationships are not sustainable; therefore, there is an urgent need for academic developers to have a better understanding of how to manage the emotional experiences of educators.

Educators’ emotions during the transition to online teaching

The change in practice from teaching f2f to either online or blended modalities is known to be an emotional experience (Dhilla, Citation2017) that is often met with reluctance (Huang et al., Citation2021). Kilgour et al. (Citation2019) suggest this is because the transition requires ontological and epistemological shifts as teachers grasp threshold concepts that conflict with their existing approaches to teaching such that they experience feelings of liminality, uncertainty, and anxiety. The transformative learning that accompanies threshold concepts can be deeply emotional, causing feelings of loss as ways of thinking about and being in the world are transformed (Timmermans, Citation2010).

Naylor and Nyanjom (Citation2020) found that the change to online teaching required significant emotional energy, with educators reporting both positive and negative emotions associated with the rate of change and perceived institutional support. Huang et al. (Citation2021) also reported mixed feelings associated with an institutionally led change to blended learning, with educators feeling motivated by caring for their students, yet demotivated by a lack of agency. Overall, the educators in Huang et al.’s study did not feel cared for by the institution during this change. Some of their participants who had previous experience teaching in a blended mode expressed more positive sentiments, suggesting that a shift to online teaching is a process of transition (Huang et al., Citation2021). Regan et al. (Citation2012) found a similar variation in emotions depending on how long educators had been teaching online, with feelings evolving in valence from negative to positive as educators gained experience and skill in online teaching.

Feelings of loss related to the embodied nature of teaching, the loss of control in the online space, and the loss of time for the creation of online resources have also been reported (Palmer et al., Citation2007), as has a loss of self-efficacy (Geertshuis & Liu, Citation2020). In the collaborative autoethnography (CAE) which provides the data for this secondary analysis study (in which the authors participated) Fox et al. (Citation2021) also identified a sense of loss:

We therefore asked ourselves: why are we mourning these physical spaces and bodily connections so deeply? Is it that we have lost something or perhaps even that we cannot quite determine what we have lost? (p. 12)

This concept of mourning suggests that educators are experiencing a deep sense of grief for what has been lost. Therefore, we looked to the Kübler-Ross model of grief (Kübler-Ross, Citation1970) as an appropriate frame to further our understanding of educators’ experience of this change.

The Kübler-Ross model and change

The Kübler-Ross (KR) model of grief (Citation1970) has been applied to organisational change for some time, although apart from Kearney’s (Citation2002, Citation2003, Citation2013) work, it has rarely been applied to educational change. Despite this, Rosenbaum et al.’s (Citation2018) review of thirteen commonly used organisational change models highlights the KR model as offering explanatory power with respect to emotions. The KR model explains why people resist change and provides a means to understand how emotional responses to change evolve over time (Buller, Citation2014; Friedrich & Wüstenhagen, Citation2017; Kearney, Citation2003). Having identified loss as a predominant emotion experienced in the shift to online teaching (e.g., Fox et al., Citation2021; Palmer et al., Citation2007), we applied the KR model as a novel framework to analyse autoethnographic data that charts educators’ emotional experiences of this change.

The KR model suggests that all change requires letting go of something, and that for every change, someone loses something (Buller, Citation2014; Kearney, Citation2003, Citation2013). The KR model has six stages that can be thought of as fluid, often co-existing, overlapping, or repeating each other, rather than occurring as sequential stages (Kearney, Citation2013):

Denial: unwilling to accept that the change is occurring

Anger: expressing resentment and frustration that may be directed towards the person or organisation triggering the change

Bargaining: acknowledging the situation, but attempting to negotiate more time or better conditions

Depression: mourning the present conditions and better days of the past

Acceptance: adapting to the new reality

Hope: positivity threading through the other stages or re-emerging during Acceptance (Friedrich & Wüstenhagen, Citation2017; Kearney & Hyle, Citation2004).

Materials and methods

Study context

The research was undertaken in 2019 at a large Australian university during the implementation phase of a centrally led curriculum redesign project. In the project, a central team worked alongside faculty academics to co-design units for either fully online or blended (i.e. a combination of online and on-campus) delivery (Elliott & Taylor, Citation2019). The new delivery model involved the creation of an online curriculum spine consisting of a sequenced package of content (e.g., videos and teacher-generated text) interleaved with learning activities (e.g., quizzes and discussions) that were complemented by either synchronous online or on-campus active learning classes. Both the online and blended modes thus had identical asynchronous online content and activities and only differed in the synchronous aspects of the unit.

Method and participants

This study is based on data produced in 2019 through collaborative autoethnography (CAE) (Chang et al., Citation2012; Fox et al., Citation2021) to understand the lived experiences of transitioning to teaching online as part of the curriculum redesign project. The participant-researchers in the study included five teaching academics, an academic developer (the lead author of this paper), and two research academics, each with varying levels of experience in online teaching.

The original CAE data collection process occurred pre-COVID across five fortnightly cycles of individual and collective meaning making (Chang et al., Citation2012). The process began with an individual written reflection on a set of prompts (see online materials). This individual meaning making enabled each of us to interrogate ourselves (Chang et al., Citation2012), making our thoughts and emotions visible through our responses. These were then shared amongst the team before a 90-minute meeting the following week where we discussed the reflections as a group. This group meaning making enabled us to examine our individual voices, adding depth to our understanding (Chang et al., Citation2012). After each meeting, themes were distilled to form prompts for the following week. This led to the five group transcripts and 38 individual reflections forming the corpus of data for this study (see Fox et al., Citation2021, for an in-depth description of this method).

Given the monumental shift online due to COVID-19 and the relevance of our experience of loss, a sub-set of the original CAE research group re-analysed the full data set for this paper using the KR model as a conceptual frame. This secondary data analysis (occurring in 2021) utilised both deductive and inductive thematic analysis (Xu & Zammit, Citation2020). For the deductive analysis, authors were each allocated one week’s texts to code independently (thus authors were coding their own responses alongside those of the group), using Kearney’s (Citation2002) ‘feeling adjective list’ aligned to the KR model as a coding frame. To aid in the consistency of coding, we used definitions from the Macquarie Dictionary as a reference. Data could be coded to multiple adjectives as often excerpts contained a mixture of emotions, and any excerpts that weren’t captured by the ‘feeling adjective list’ were noted and discussed as a group as potential additions to the list, similarly to Kearney (Citation2002).

Data were transferred to NVivo 12 Plus so they could be further organised and discussed at two group meetings where we confirmed coding through dialogue and iteration. The first author then undertook an inductive analysis to identify themes and refined these with the group through further dialogue and iteration. This study was approved by the relevant university ethics group.

Results and discussion of the deductive analysis

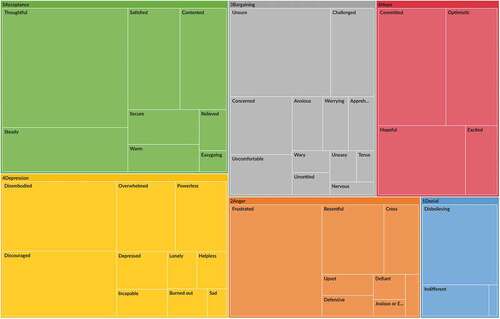

The range of emotions associated with each stage of the KR model identified in the data is illustrated in . While emotions associated with each stage of the KR model (as described in the Background section above) were present in the data, not all emotions in Kearney’s (Citation2002) list were identified. We did, however, identify four additional emotions indicated in italics in .

Table 1. Emotions experienced by participants aligned to KR stages.

The hierarchy chart in provides a visual representation of the relative amount of emotion in each stage, showing that acceptance and depression had the most coding, with thoughtfulness having the most codes. This illustrates that, as a group, emotions associated with acceptance and depression were most commonly expressed, albeit not necessarily experienced, by each individual. That is, some participants may have experienced no emotions reflective of depression, while experiencing numerous emotions associated with acceptance.

The sub-themes and illustrative quotes associated with the identified emotions in each stage are discussed below before moving to the results of the inductive analysis and discussion of implications for practice.

Denial

Denial for our educators centred around a disbelief that we could effectively make connections with students online to facilitate deep learning, a disbelief in being able to blend online and on-campus students effectively, and a disbelief in the efficacy of online learning if students didn’t choose to participate or if learning was made to be too easy:

If we do not engage or extend our student in ways that I/we know are confronting but impactful – and they [can] switch off and walk away from the screen when it gets too challenging- how does learning happen? Without struggle, no serious/real impactful learning occurs.

Paradoxically, feelings of indifference towards students stemmed from educators not feeling connected to their curriculum or their students in the same way they did f2f:

This is going to sound horrible … I’ve found my relationship with students, because I don’t meet them, I’m less emotionally attached. If I’m less emotionally attached, then I care less.

Anger

In this stage, educators were predominantly frustrated, resentful, cross, and upset. Educators were cross and frustrated if patterns of student engagement did not meet their expectations when educators felt they had put enormous effort into creating engaging learning opportunities that were not taken up by students:

Because we go to great lengths to find a certain calibre of people that have experience and then the students don’t show up … It does make you cross.

Despite the fact that I am very planned and organised … try to base my online learning environment on accepted best practice pedagogy, along with all the ‘bells and whistles’ … the majority of students just do not appear to want to fully engage.

Frustration was also related to a lack of agency and inflexibility in the curriculum design process and not being able to improvise during online teaching:

You’re not allowed to be playful or exploratory or push things back. We’ve got to get everything fitting together … But it seems to sort of impose a little.

I find that a little bit limiting, in a sense, because you make a video, you assemble things. And you know, with … the team that we were working with the learning development people, there is a straight jacket.

The clinical nature of the online space was seen as deterring students from having informal interactions, leaving some educators feeling upset:

I’ve found students being more overly polite in the online space … because it’s captured there. So I think that kind of messiness- I wish it could be a bit more messy.

Bargaining

In this stage, educators mainly felt unsure, challenged, concerned, anxious, and uncomfortable. Feeling challenged was a newly identified emotion related to the demanding nature of teaching online. For instance, challenges were associated with putting effective boundaries around time spent teaching online, and with developing and maintaining relationships with students:

Teaching and learning through a screen makes it harder to establish and maintain the relationship that I think is needed.

I think online education is really hard work and part of the demand is the asynchronous nature of it. I like boundaries in my life and online education never has any boundaries because you always have to be just a little bit present as oppose[d] to really completely present in one block.

Educators were also unsure about how their students viewed them behind the screen:

I have little idea really – from the students’ perspective I think I am possibly a shadowy figure with lots of words – sort of an intellectual, probably sometimes annoying, presence rather than a real embodied human.

Concern and worry were related to being unsure of how the students were doing, as educators were constantly looking for indicators of student satisfaction and learning:

I don’t really know how the[y] students are doing … I can tell if there are difficulties when they submit their first assessment in week 4 … I can only see what is made apparent by answering wrongly to a question; this is not giving me the full picture though.

It is more asynchronous now. Like developing a long-distance relationship by writing love letters. You have to wait till the other person responds and you don’t know what they are thinking until it is put out there.

Being uncomfortable related to not knowing what the student experience was like, but also to the permanency of online materials and the loss of control online:

I also feel that these set[s] of resources that now are out there have an ‘independent’ and separate life, which I cannot control

Now, students navigate it themselves … I do feel like a hands-off tour guide. ‘Ok kids, here is the zoo, here is your map and your book about the animals. I’ll wait for you outside the exhibit and then we will discuss the monkeys. No I won’t be going with you. I will wait for you here’. … At first I didn’t think there was a difference. But this is actually a big shift. I am far less in control.

Depression

This loss of control also caused feelings of powerlessness–a newly identified emotion that also stemmed from educators not having control over who was observing their teaching:

I feel like I’m being watched or judged or whatever, … ‘I’m being judged’, but on the flip side of that, you go, ‘Well, that’s me, I can just go no, no, that’s fine’. It’s my class and I know what I’m doing and people can come and watch me and I know that I’m right and they can have whatever opinion they like. But I think there’s an element with it that because there’s so much interest and pressure.

Disembodied was also identified as a new emotion that was seen as impacting on relationships with students, but also related to feeling disconnected from teaching:

My professional identity shifts when I teach online. I am curator of content, a performer in videos, a discussion board moderator, a facilitator. I don’t ‘feel’ like I am educating really because I don’t feel an attachment to my cloud site and don’t really feel connected with the students because there isn’t that online engagement I am looking for.

Acceptance

Our educators were thoughtful, content, steady, and secure. Thoughtfulness manifested as ongoing reflection on being an online teacher and imagining how students felt as online learners. There was uncertainty in not knowing whether students were learning online. As our educators are reflective practitioners, this stimulated a desire for continuous improvement and steadiness in the belief that things would improve as they gained experience in online teaching:

What is missing is the verbal cues that one picks up in a face-to-face situation, but I think we need to learn to let go of it somehow, and develop a different way of picking up cues.

This is one of the things that we’ve been looking across the project thinking whether or not, have we set up the expectations correctly in each unit, or is there something overall that we could have done?

There was also a sense of being steady and secure in their teaching philosophies and their judgement as expert educators:

The ethics of learning also matters to me – that is, in these times, I think it’s a responsibility of education to integrate ethics into courses and facilitate ethical orientations to modes of thought.

Good teaching [and learning] is about relationships, passion and meaning … Relationships between teacher and learner, and learner and learner, are vital because learning is a collaborative co-production with all sides of these relationships working together, and not necessarily in harmony – sometimes conflict and tension are just as important.

And finally, the educators reflected on the perceived shift towards transactional learning and whether online learning was somehow different from learning f2f:

Maybe it’s a mistake to think about online teaching and learning as teaching and learning because it’s a contortion of what we know as teaching and learning. And so we are forever trying to make this thing like that instead of going, it’s different, it has different outcomes. It looks different, it feels different. It comes back at as different and it achieves different things and we can do things that make it better.

Hope

Threaded throughout the experience of change were feelings of being hopeful and optimistic about the ability of online learning to democratise education, being committed to developing meaningful relationships with students, and seeking continuous improvement. Educators spoke of feeling simultaneously disembodied from, but also hopeful and excited by, the possibilities of online teaching and learning:

One of my students lives in Berlin. Watching live tweets of [a colleague’s presentation] in Germany feels so extraordinary: the way his work can be circulated and taken up for a broad audience. I don’t even know where I was when I was reading those tweets … It disembodied me, in a way, and in my mind’s eye all I see is the tweet on my phone and pressing the heart symbol, not where I was.

It made me think of the opportunities that online learning affords people who may have a disability or live-in remote areas where travelling to campus … is just not possible.

Hope was related to the curriculum redesign process as it enabled rare time and space for conversations about teaching and learning – an opportunity to reflect and to take a systematic approach to renewal:

I quite enjoyed the Cloud site creation phase and I think there is lots to be excited about. The making of the site was extremely collaborative and did enact a creative process.

Inductive analysis and discussion of implications for practice

Our inductive analysis identified three overarching themes associated with loss, grief, and hope. These themes related to educators’ perceived changes in relationships with their students, curriculum, and teaching practice.

Loss and the change in relationship between educator and student

The experience of loss associated with the change in educators’ relationships with their students was palpable, with educators feeling overlapping emotions across the KR stages of anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, and hope.

But we as teachers feel really isolated in the online environment too, and I don’t know how we overcome that because we’re feeling very isolated as well. And we’re feeling disconnected from our student cohorts and the learning that’s meant to be happening in our units.

They were unsure, discouraged, lonely, and resentful as they mourned the loss of, and reminisced about, connections with students. At the same time, they were thoughtful, optimistic, passionate, and committed to their students, working hard to overcome the challenge of fostering meaningful relationships with students online. When students were not interacting with content or educators in ways that were expected, educators felt a mixture of anger and depression and were cross, frustrated, resentful, lonely, and hurt. As they had a strong sense of commitment and care for their students, they felt unsure and concerned because this lack of interaction meant they could not see their students’ learning, which fuelled feelings of depression (discouragement, disconnection, loneliness, and sadness). This complex interplay of emotions supports Kilgour et al.’s (Citation2019) proposition that the notion of educator-student relationships is a threshold concept in transitioning to online teaching.

To support staff who feel loss associated with this change, student success stories could be used to demonstrate the ways in which online learning can lead to increased participation and access. Furthermore, Badia et al. (Citation2019) found that teachers who viewed their role as ‘guides on the side’ experienced pleasant emotions and greater satisfaction. Consequently, highlighting how teacher guidance is embedded in online content to scaffold self-directed learners and focusing on online facilitation strategies may encourage feelings of satisfaction, relief, and optimism. The positive impact on educators of seeing students apply their learning was evident in our study:

One of the aims of redesigning the … unit was to make it more practical and relevant to working professionals. In this case, it has worked! And a student is acknowledging the utility of theories!? And thanked me for it!? How often does this happen?! It makes me really happy to know that something from my class has improved the working life of a student.

Loss and the change in relationship between educator and curriculum

Educators also felt loss as they experienced a disconnection from their curriculum. Similar to Huang et al. (Citation2021) description of educator experiences of centrally led curriculum projects, our educators experienced a sense of loss of autonomy and agency over pedagogical decision making:

I feel that I am the one that is considered responsible for the material that is out there as the academic in ‘charge’ of the content, but in reality, I feel that I had little input in the way the actual content is presented and structured, and yet I am the one that is ‘responsible’ for it.

This led to feeling powerless and frustrated with the curriculum redesign process, and also to being discouraged and defensive as the newly designed curriculum wasn’t producing the desired effect in student learning. However, there was also excitement, hopefulness, thoughtfulness, and a commitment to continuous improvement. This shows the overlap of emotions across various stages of grief. Not only is curriculum being changed in the move online, but educators’ relationship to their curriculum is also being transformed.

Applying the KR model to conceptualise the change to OBL reminds us to acknowledge the emotional impact of change. It also normalises negative emotions and provides a framework for sensemaking (Kearney & Siegman, Citation2013). To support this process, centrally led online curriculum change projects should take a person-centred approach (Flynn & Noonan, Citation2020) that encourages collaboration and dialogue, while also privileging staff wellbeing over deadlines, so that educators feel empowered, respected, and cared for. Furthermore, in the context of such projects, feelings of powerlessness may be attenuated by increasing transparency so that staff do not feel that they are being unduly judged and accountability lines are clear. Since powerlessness was a new emotion identified in this study within the context of a centrally led project, it may be that this emotion is not expressed by educators who choose to move to OBL of their own accord, as was found by Huang et al. (Citation2021).

Loss and the change in relationship between educator and teaching practice

Finally, a sense of loss was associated with a change in practice to online teaching. Emotions centred around feeling disembodied as teaching identity and practices shifted. Teaching as performance was lost, as was physical connectedness with students. Educators felt overwhelmed and unsure as the security and comfort of tried and tested teaching strategies moved to those yet to be proven:

What I find myself doing a lot is questioning – questioning me, my methods, my abilities.

Educators were secure in their teaching philosophies and committed to student success and satisfaction. This mixture of emotions perhaps reflects the oscillations between stages of grief alongside liminality as they grappled with threshold concepts (Meyer & Land, Citation2005) around teacher presence as they repositioned themselves in the online world.

While it is tempting to view the vulnerability and anxiety experienced by educators during the transition online as problematic and negative, these emotions can indicate the transformational power of change (Timmermans, Citation2010). Emotions associated with denial, anger, and acceptance are sometimes referred to as ‘active’ responses which reflect energy within an individual (Buller, Citation2014). This energy can be harnessed by academic developers to stimulate creativity and energise the learning of new approaches to teaching (Bennett, Citation2014). In addition, these emotions can stimulate reflection and sensemaking, assisting staff to grow, be open to change, and adapt in the context of uncertainty (Critchley, Citation2012). Transitioning through grief and meaning making after loss can also be a learning process; however, as negative emotions associated with grief can obstruct learning, it is important that these emotions are recognised and managed to support growth (Shepherd & Kuratko, Citation2009).

To facilitate this growth, it may be beneficial to create structured opportunities for academic developers and educators to surface and make meaning of their emotional experiences and to work collaboratively to find solutions to the challenges of OBL. This could take the shape of a CAE process or a community of practice. Such collaborations may also provide an opportunity to nurture academics’ sense of self-efficacy (Shepherd & Kuratko, Citation2009), build academic and support staff relationships that have historically been strained (Bellaby et al., Citation2020), learn from each other’s experiences, and create space for dialogue to reinforce caring relationships (Huang et al., Citation2021).

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. Firstly, the results represent a snapshot of emotions experienced during the implementation of the centrally led change. Consistent with findings from previous studies (Huang et al., Citation2021; Regan et al., Citation2012) and the KR model (Friedrich & Wüstenhagen, Citation2017; Kearney, Citation2013), it is anticipated that the valence of emotions is likely to be more positive over time. Secondly, this paper reports on a change that happened within the context of one university. However, we believe the findings are applicable to similar planned and centrally led online curriculum change projects. Finally, in this study, the researchers were also the participants. While some may consider this dual role a methodological weakness, it is also a strength of CAE because it enables collective meaning making, investigation of researcher subjectivity, and community building (Chang et al., Citation2012).

Conclusion

Our study makes a valuable addition to the academic development literature by applying the Kübler-Ross model of grief (Citation1970) in a novel way to understand the emotional experience of transitioning to online teaching. It captures both the loss associated with the change itself and the loss associated with learning as new threshold concepts are mastered. The CAE data show that grief is experienced in relation to changes in relationships with students, curriculum, and teaching practice. Institutional processes can support both educators and academic developers to navigate this change by taking a person-centred approach to centrally led curriculum transformation projects.

By applying the Kübler-Ross model, this study has highlighted that the move to online teaching involves a significant transition from f2f teaching, requiring time and dialogue to support making sense of loss, grief, and growth as we transform ourselves and become online educators.

Ethics statement

This research was approved by the Faculty of Arts & Education Human Ethics Advisory Group, Deakin University, HAE-19-119.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to thank their other colleagues who were part of the original CAE group for participating in this research project. The authors also thank the reviewers for their generous advice that improved the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

As an in-depth qualitative project, open data access is not possible for ethical reasons

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Darci Taylor

Darci Taylor [BA Sc(Hons), GCHE, GDipEd] SFHEA, is the Director, Learning Design at Deakin University. She provides leadership, strategic direction, and operational advice on learning design to support student success and teaching excellence. Her research interests include students’ personal goals, students as partners, the changing nature of the higher education workforce, and the impact of teaching and learning innovations.

Margaret Bearman

Margaret Bearman PhD, is a Research Professor at the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning (CRADLE). Margaret researches higher and professional education with particular interests in assessment, feedback, and practice-informed understandings of post-digital learning contexts.

Simona Scarparo

Simona Scarparo (Phd Edinburgh, MSc Bologna, BSc Cagliari) is a Senior Lecturer in Accounting at Deakin Business School, Department of Accounting. Simona’s research explores contemporary critical accounting issues, focussing on research on gender in the accounting professions, accounting in popular culture, accounting and education, and management accounting in public sector organisations.

Matthew Krehl Edward Thomas

Matthew Krehl Edward Thomas [BA(Hons), GCertHELT, GCertAIB, GDipEd, PhD] SFHEA, is a Senior Lecturer in Pedagogy and Curriculum and the Academic Director of Professional Practice at Deakin University. Matthew’s research explores time, power, and human rights in the age of surveillance capitalism.

References

- Badia, A., Garcia, C., & Meneses, J. (2019). Emotions in response to teaching online: Exploring the factors influencing teachers in a fully online university. Innovations in Education & Teaching International, 56(4), 446–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2018.1546608

- Bellaby, A., Sankey, M., & Albert, L. (2020). Rising to the occasion: Exploring the changing emphasis on educational design during COVID-19. In Proceedings of ASCILTE’s First Virtual Conference, Armidale. University of New England

- Bennett, L. (2014). Putting in more: Emotional work in adopting online tools in teaching and learning practices. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(8), 919–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.934343

- Buller, J. L. (2014). Change leadership in higher education: A practical guide to academic transformation. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F., & Hernandez, K.-A.-C. (2012). Collaborative autoethnography. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Critchley, K. (2012). Managing change. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 5(3), 40–43. https://www.bjmp.org/content/managing-change

- Dhilla, S. J. (2017). The role of online faculty in supporting successful online learning enterprises: A literature review. Higher Education Politics & Economics, 3(1), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.32674/hepe.v3i1.12

- Educause. (2021). 2021 educause horizon report: Teaching and learning. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2021/4/2021-educause-horizon-report-teaching-and-learning-edition

- Elliott, J., & Taylor, D. (2019). ‘Okay, but what does it look like?’ Building staff capacity in online learning through role modelling. In Proceedings of ASCILITE, Singapore University of Social Sciences, Singapore.

- Flynn, S., & Noonan, G. (2020). Mind the gap: Academic staff experiences of remote teaching during the Covid 19 emergency. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 12(3), 1–19.

- Fox, B., Bearman, M., Bellingham, R., North-Samardzic, A., Scarparo, S., Taylor, D., Thomas, M. K. E., & Volkov, M. (2021). Longing for connection: University educators creating meaning through sharing experiences of teaching online. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(5), 2077–2092. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13113

- Friedrich, E., & Wüstenhagen, R. (2017). Leading organizations through the stages of grief: The development of negative emotions over environmental change. Business & Society, 56(2), 186–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315576151

- Geertshuis, S., & Liu, Q. (2020). The challenges we face: A professional identity analysis of learning technology implementation. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 59(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2020.1832904

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020, March 27). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Huang, J., Matthews, K. E., & Lodge, J. M. (2021). ‘The university doesn’t care about the impact it is having on us’: Academic experiences of the institutionalisation of blended learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1915965

- Kearney, K. S. (2002). A study of the emotional effects on employees who remain through organizational change: A view through Kubler-Ross (1969) in an educational instituions. Oklahoma State University.

- Kearney, K. S. (2003). The grief cycle and educational change: The Kubler-Ross contribution. Planning and Changing, 34(1), 32–57.

- Kearney, K. S., & Hyle, A. E. (2004). Drawing out emotions: The use of participant-produced drawings in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Research, 4(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104047234

- Kearney, K. S. (2013). Emotions and sensemaking: A consideration of a community college presidential transition. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 37(11), 901–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2012.744951

- Kearney, K. S., & Siegman, K. D. (2013). The Emotions of Change: A Case Study. Organization Management Journal, 10(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15416518.2013.801744

- Kilgour, P., Reynaud, D., Northcote, M., McLoughlin, C., & Gosselin, K. P. (2019). Threshold concepts about online pedagogy for novice online teachers in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(7), 1417–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1450360

- Kolomitro, K., Kenny, N., & Sheffield, S.-L.-M. (2020). A call to action: Exploring and responding to educational developers’ workplace burnout and well-being in higher education. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1705303

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1970). On death and dying. Macmillan.

- Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge 2 -Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49(3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6779-5

- Naylor, D., & Nyanjom, J. (2020). Educators’ emotions involved in the transition to online teaching in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1811645

- Palmer, S., White, R., & Holt, D. (2007). Conceptions of teaching with integrity online in higher education: A case in the field of engineering. In Proceedings of the ED-MEDIA 2007 World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications, Vancouver BC, Canada.

- Popovic, C. (n.d.). Chapter 11: Teaching online. York University. https://edta.info.yorku.ca/teaching-online/

- Regan, K., Evmenova, A., Baker, P., Jerome, M. K., Spencer, V., Lawson, H., & Werner, T. (2012). Experiences of instructors in online learning environments: Identifying and regulating emotions [Article]. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(3), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.12.001

- Rosenbaum, D., More, E., & Stean, P. (2018). Planned organisational change management: Forward to the past? An exploratory literature review. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 31(2), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-06-2015-0089

- Shepherd, D. A., & Kuratko, D. F. (2009). The death of an innovative project: How grief recovery enhances learning. Business Horizons, 52(5), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.04.009

- Timmermans, J. A. (2010). Changing our minds: The developmental potential of threshold concepts. In J. H. F. Meyer, R. Land, & C. Ballie (Eds.), Threshold concepts and transformational learning (pp. 3–19). Sense Publishers.

- Trigwell, K. (2012). Relations between teachers’ emotions in teaching and their approaches to teaching in higher education. Instructional Science, 40(3), 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9192-3

- Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(3), 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

- Xu, W., & Zammit, K. (2020). Applying thematic analysis to education: A hybrid approach to interpreting data in practitioner research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920918810