ABSTRACT

This systematic review explores what is known about the relationships between characteristics of pedagogical development programmes (PDP) in higher education, context characteristics within which PDPs take place, and teacher development outcomes. Thirty-one peer-reviewed articles were reviewed using the Interconnected Model of Professional Growth (IMPG) and curriculum spiderweb. PDP characteristics, context characteristics, and teacher development outcomes appeared to vary widely. Still, several relationships were identified between specific PDP characteristics and teacher development. The review yielded an enriched model (building on the IMPG) of the pedagogical development of higher education teachers. This model and the results of this review can help academic developers to improve the design of PDPs and provide guidelines to further investigate the value of PDP.

Introduction

The quality of teaching is widely seen as a key factor that positively impacts student learning. Over the past decades, pedagogical training of university teachers and the recognition for teaching in university career advancement have received growing attention (Graham, Citation2018). Higher education institutes have set up their own pedagogical development programmes (PDPs), and in many cases, these activities have become mandatory for (new) academic staff. In this study, a PDP is defined as a coherent set of activities targeted at stimulating pedagogical teacher development (De Rijdt et al., Citation2013). Previous review studies have shown that pedagogical development initiatives play an essential role in stimulating university teacher development. In their review of studies in higher education, Stes et al. (Citation2010) concluded that most studies found positive effects on teachers’ behaviour and learning (i.e. attitudes, conceptions, knowledge, and skills) and in a few cases, studies measured institutional impact and change within students. In their review of studies in medical education, Steinert et al. (Citation2016) concluded that PDP initiatives received high satisfaction among participants and resulted in changes in teachers’ behaviour and learning. According to Steinert et al. (Citation2016), the impact on organisational practices and student learning remained relatively unexplored. These review studies did not describe how changes in teachers’ behaviour affects student learning.

There is consensus on at least some of the characteristics of high-quality PDPs that stimulate teacher development (Desimone, Citation2009). For example, in their review study, De Rijdt et al. (Citation2013) focused on influencing variables that fostered teachers’ transfer of learning into practice. They identified three categories of influential variables, namely learner characteristics, intervention design, and work environment. Moreover, Stes et al. (Citation2010) and Steinert et al. (Citation2016) defined specific characteristics of pedagogical development initiatives that seemed to have a positive impact on teacher development, such as longitudinal program design; the relevance of the content for practice; the nature of the intervention (i.e. on the job, collective course, alternative/hybrid format); and teaching methods wherein teachers have opportunities for feedback, reflection, practice, and application. While these studies do offer relevant insights into effective ingredients of PDPs, they lack information on relationships between PDP characteristics and specific teacher development outcomes. This is problematic, as a list of effective characteristics does not help to understand how these characteristics relate to and affect different teacher development outcomes, let alone, student learning (Van Veen et al., Citation2012). As a result, it is unclear how academic developers could use these characteristics effectively when designing PDPs. The current study aims to update the existing literature with a focus on exploring what is already known about the relationships between PDP characteristics and teacher development outcomes.

Theoretical background

The conceptual framework guiding this review study is the Interconnected Model of Professional Growth (IMPG) (see ; Clarke & Hollingsworth, Citation2002) and has been used in a previous review study on teacher development in science education (i.e. Van Driel et al. Citation2012). According to the IMPG, teacher development can be related to the external domain (i.e. PDP characteristics) and takes place in a change environment consisting of hindering and stimulating factors (i.e. context characteristics). Teacher development is categorised into three domains: the personal domain, referring to changes in teacher knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes; the domain of practice, referring to changes in teachers’ behaviour in designing and executing education; the domain of consequence, referring to outcomes in student learning or on the organisation.

Figure 1. The interconnected model of professional growth.

Because the IMPG does not provide detailed information on specific PDP characteristics, we used the ‘curriculum spiderweb’ (Van den Akker, Citation2003) to operationalise the external domain more precisely. The spiderweb distinguishes ten components that, when aligned, form an inherently consistent curriculum (in this study the PDP) with the rationale being the core component (see ).

Table 1. Curriculum components in the curriculum Spiderweb.

Research questions

The central question of the current review is How are characteristics of pedagogical development programmes (PDPs) for higher education teachers, and the context wherein these programmes take place, related to different domains of teacher developmentFootnote1?

This question is subdivided into the following research questions:

What PDP characteristics are described in the literature?

What context characteristics within which PDPs take place are described in the literature?

What teacher development outcomes resulting from PDP have been reported in the literature?

How are PDP characteristics and the context characteristics within which PDPs take place related to domains of teacher development?

Method

Literature search procedure

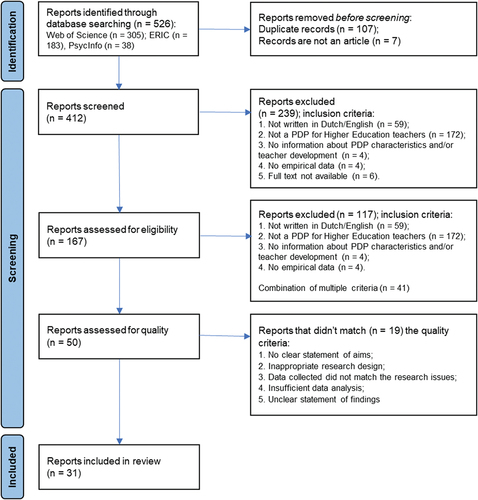

This systematic review involved several steps (cf. Petticrew et al. Citation2006). The flow diagram of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009) shows the process of data collection and inclusion (see ).

Databases and literature search terms

Web of Science, ERIC, and PsycINFO were used as databases. Because of the inconsistent use of terminology in the literature, we used a variety of synonyms for PDP based on the aforementioned review studies and our first readings of studies. We combined the search term ‘pedagogical development’ with three other sets of search terms (see Appendix A): synonyms for ‘university teacher’, ‘higher education or university’, and ‘programme or trajectory’. Because the review of De Rijdt et al. (Citation2013) was the last review that focused specifically on key characteristics of pedagogical development in higher education, we focused on articles published between 2013 and 2019. After deleting duplicates, the search (executed in August 2020) resulted in 412 articles.

Inclusion process and quality check

The first author read the titles, abstracts, and key words of retrieved articles to check if these met the inclusion criteria (see ), resulting in 167 articles. After having read the full-text articles, 50 articles remained. The quality of the included articles was checked by the first author using five quality criteria drawn from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Citation2018, 31) articles complied with all five quality criteria (see ). In all these steps, the co-authors reviewed a subset of articles and agreed with the decisions made by the first author.

Description of the dataset (Appendix B)

Most of the 31 studies included in the review have been conducted in North America (n = 11) and Europe (n = 11). PDPs focused on different topics, varying from general ‘teaching in higher education’ (n = 14) to specific (combinations of) topics, such as learner-centred approach (n = 8), technology integration (n = 4), English foreign language education (n = 3), or specific theories. To measure teacher development (i.e. personal domain, domain of practice, and domain of consequence), most studies relied on teachers’ self-perceptions through surveys (n = 17), interviews (n = 14), reflections (n = 8), and focus groups (n = 6). Observations (n = 8), student evaluations (n = 4), rubrics (n = 3), and decibel analysisFootnote2 were used to measure changes in the domain of practice. Student outcomes (n = 2) were used to measure changes in the domain of consequence. Three articles used a control group and eight used pre- and post-measurements.

Data analysis

The Best Fit Framework Synthesis (BFFS) method (Booth & Carroll, Citation2015) was used for analysing the included studies. BFFS builds further on established theories (here, the IMPG and the Curriculum spiderweb) starting with a deductive phase of data analysis, followed by an inductive phase to explore data further. See Appendix C for an overview and description of the codes.

First, deductive coding was applied by using the domains of the IMPG to cluster the data. The second author checked the reliability of the coding process. After several rounds of coding, discussion, and sharpening the code book, sufficient reliability was reached (Krippendorff’s Cu-α = 0.743).

Second, deductive and inductive coding were used to further analyse the fragments in the different domains. The PDP characteristics (i.e. external domain), RQ1, were deductively coded using only the curriculum spiderweb components of learning goals, timeframe, teaching methods, and grouping because the other components (e.g. assessment, resources) were not included in the majority of studies. The context characteristics (i.e. change environment), RQ2, were inductively coded leading to the codes voluntary/compulsory, funding, facilitation, and accreditation. Teacher development fragments, RQ3, were further coded by analysing if the reported outcome was positive, neutral, or negative and by specifying the domains in subcodes. Within the personal domain, the subcodes knowledge, attitude/belief, confidence, skills, and intention to apply emerged from the data; within the domain of practice, these were design and teaching; within the domain of consequence, the subcodes organisation, student, and teacher emerged.

Concerning RQ4, it appeared that relationships between the domains of IMPG were not the focus of the included articles. Therefore, three steps were taken to identify relationships. First, the first author analysed the reviewed articles that used perception data showing some relationships between a PDP characteristic (external domain) or context characteristic (change environment) and a change in the domains of teacher development (i.e. personal domain, domain of practice, or domain of consequence). For example, the fragment, ‘when my peers shared lessons learnt when things went wrong for them, this helped me build up my own digital skills, knowledge, and confidence’ (Donnelly, Citation2019, p. 319), was coded as a perceived relationship between the PDP characteristic teaching method ‘collaboration’ and development within the personal domain.

Second, the first author analysed five articles that used triangulated data (i.e. using a control group or combining multiple data sources). It can be assumed that measured teacher development controlled by a control group or with multiple data sources are actually an effect of the PDP and thus imply a relationship. The PDP characteristics, the context characteristics, and the teacher development domains of these five articles as analysed in RQs 1, 2, and 3 were visualised with the IMPG. The measured outcomes with triangulated data were connected to the external domain (i.e. PDP characteristics) by an arrow, which implies a relationship. Subsequently, commonalities in PDP characteristics identified in more than one article were established.

Third, in answering RQ4, the results of steps one and two were combined by analysing which relationships between characteristics and teacher development domains were coded both in the perception and triangulated data. A selection of the relationships found in steps 1 and 2 was checked by one other co-author, and the entire process and results were discussed several times with the co-authors.

Results

The following sections describe the results in relation to the four research questions. See Appendix B for an overview of the articles, as well as for the specific PDP characteristics, context characteristics, and teacher development described in each article.

PDP characteristics (RQ1)

Learning goals

About two-thirds of the articles (n = 20) described a learning goal regarding the personal domain: attitudes/beliefs (e.g. ‘a positive reinforcing attitude towards learners’); teaching effectiveness and confidence (e.g. ‘bolstering teaching assistants’ confidence and teaching effectiveness’); and knowledge and skills (e.g. ‘pedagogical and technological knowledge and skills for effective online tutoring’). Thirteen articles described learning goals regarding the domains of practice (e.g. ‘implementing ICT supported student-centric teaching strategies’), and 11 articles described learning goals in the domain of consequence, subdivided into student-level goals (e.g. ‘to help their students improve their technology skills’) and organisation-level goals (e.g. ‘support iterative change in biology teaching’). Half of the articles (n = 16) described learning goals in multiple domains. In five articles, the overall PDP’s learning goals were not specified further then describing the generic purpose of aiming to enhance teaching quality.

Timeframe

The PDPs varied in timeframe from less than two weeks (short, n = 6), between two weeks and a semester (medium, n = 6), and longer than a semester (long, n = 18). Once, no time indication was described.

Teaching methods

Twelve different teaching methods were described: discussion, collaboration, instruction, portfolio/reflection, study material, feedback, mentoring, designing teaching, observation, micro teaching, modelling, and investigating effects. Discussion, instruction, and collaboration were mentioned most (n = 20). The articles varied in the number of teaching methods included. For example, Toding and Venesaar (Citation2018) solely described collaboration, while Jarvis (Citation2019) described nine different teaching methods. None of the articles described the same set of teaching methods.

Grouping

Three aspects of grouping appeared: disciplinarity (17 multidisciplinary and 9 monodisciplinary), intercultural (n = 4), and teaching experience (2 experienced, 2 inexperienced, and 6 using a mix of the two).

Context characteristics (RQ2)

Most PDPs were voluntary (n = 14), and four were compulsory. Two types of funding were mentioned: received from the government (n = 7) or from the university itself (n = 6). Five articles reported on participants receiving facilitation for participation in PDP in terms of time or money. Four articles mentioned that the PDP was accredited by other universities or the government.

Teacher development (RQ3)

Personal domain

Twenty-seven articles reported positive outcomes in the personal domain. Teacher development of knowledge was described most (n = 24; e.g. ‘additional depth of understanding of academic areas’), followed by change in attitude/belief (n = 23; e.g. ‘the PDP made me see the value of engagement’), confidence (n = 19; e.g. ‘many participants voiced strengthened self-efficacy’), skills (n = 14; e.g. ‘I did feel it did make me more reflective’), and intention to apply (n = 7; e.g. ‘I’d like to further increase the use of active learning methods’). Eight articles reported a negative or neutral change as a result of PDP: confidence (n = 7), attitude/belief (n = 2), skills (n = 2), and knowledge (n = 1) for example, ‘I end up feeling horribly under-prepared’.

Domain of practice

In total, 24 articles reported a positive change in the domain of practice: application in teaching (n = 19; e.g. ‘the teaching practice of the 2014 group developed over the three years in this study’) and application in design (n = 21, e.g. ‘I reduced number of topics covered and focused on fundamentals’). Seven articles described a negative or neutral change, such as ‘Neither students nor faculty reported differences between PDP and non-PDP instructors in the use of traditional lecture, which was commonly used in both groups’.

Domain of consequence

In 19 articles, a positive change in the domain of consequence was measured: at the organisation level (n = 12, e.g. ‘It has created a community of digital research informed teachers’), student level (n = 11; e.g. ‘more student behavioural and cognitive engagement’), and teacher level (n = 7; e.g. ‘now having a leading role in the department’). Two articles reported no or a neutral change at the student level (e.g. ‘When I gave them a question they were quiet and clearly they were working but I’m trying to get them to be talking and discussing’).

Relationship of PDP and context characteristics with domains of teacher development (RQ4)

Perception data

In 19 articles, teachers reported a perceived relationship between specific PDP characteristics and their pedagogical development. All teaching methods, except for ‘mentoring’, were perceived to be related to changes in the personal domain (n = 18; e.g. collaboration: ‘when my peers shared lessons learnt when things went wrong for them, this helped me build up my own digital skills, knowledge, and confidence’). ‘Collaboration’, ‘instruction’, ‘designing teaching’, ‘mentoring’, ‘discussion’, and ‘feedback’ appeared related to the domain of practice (n = 4; e.g. instruction: ‘learning new teaching tools and methods was the most useful part of the studies … it provided a framework with the help of which I could reflect upon my teaching practice, develop, and implement new solutions appropriate to the subject’). ‘Collaboration’ and ‘investigating effects’ were related to change in the domain of consequence (n = 2; e.g. collaboration: ‘It was nice to meet other new lecturers … just to get to know other people in the faculty’).

The PDP characteristic multidisciplinary grouping was related to change in both the personal domain (n = 2) and domain of consequence (n = 1). For example, ‘ I’m probably now, from the PDP, more tolerant of listening to other people [from other departments]. There’s always that sort of … enclosure that you exist within. So whether I took things on board or not, at least I came out of my enclosure and actually listened and engaged with other people’. Practical relevance was related to change in the personal domain (n = 3; e.g. ‘Yeah, because you’re putting the theory into practice again, even though you’ve been doing the practical I felt as … it was making more academic sense what we were doing’). Other characteristics that were mentioned were the trainers of the PDP (n = 2) and the encouragement to experiment (n = 2) in relation to the personal domain (e.g. ‘I was able to take more calculated risks and constantly change as I was actually delivering’).

Only three articles described a perceived relationship between a context characteristic and teacher development. Receiving a certificate (i.e. qualification) was related to change in the personal domain (n = 2) and domain of consequence (n = 1; e.g. ‘certainly I’ve been able to support colleagues with issues that I’ve got some background knowledge as a result of the PDP’).

Triangulated data

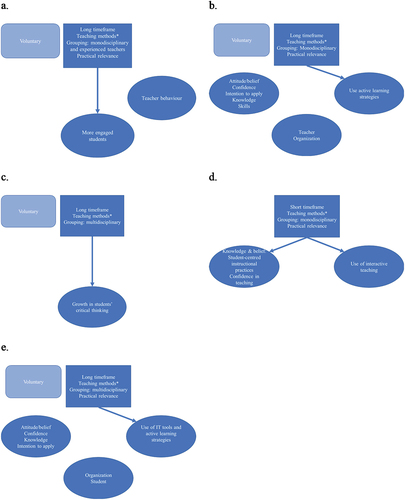

We first report changes in teacher development that were shown in the five reviewed articles using triangulated data or a control group (see ). Then, we describe commonalities and differences between the characteristics of the reported PDPs that were connected to these identified changes in teacher development.

Figure 3. Visualisation of found relationships among the various domains of IMPG. *teaching methods a. Hilpert & Husman (Citation2002) discussion, study material. b. Owens et al. (Citation2018) discussion, collaboration, instruction, portfolio/reflection, mentoring, observation, modelling, investigating effects. c. Sanders et al. (Citation2019) instruction, portfolio/reflection, feedback, mentoring, observation. d. Stain et al. (Citation2015) collaboration, instruction, feedback, designing teaching, micro teaching, modelling. e. Zheng et al. (Citation2017) discussion, collaboration, instruction, study material, feedback, designing teaching, observation, modelling.

In Stains et al. (Citation2015; see ), teachers changed in the personal domain. In Owens et al. (Citation2018; see ), Stains et al. (Citation2015, see ), and Zheng et al (Citation2017; see ), teachers changed in the domain of practice, using more active learning strategies or IT tools in the classroom. Hilpert and Husman (Citation2017; see ) and Sanders et al. (Citation2019; see ) reported a change in the domain of consequence: students with teachers who had followed the PDP reported more engagement or critical thinking skills compared to students who were taught by a teacher who did not attend the PDP.

shows an overview of commonalities and differences in PDP and context characteristics per teacher development domain. The PDPs that resulted in a change in the domain of practice used a variety of teaching methods, of which all three used ‘instruction’, ‘collaboration’, and ‘modelling’. All three PDPs explicitly focused on practical relevance. The PDPs differed in the characteristics of timeframe, grouping, and whether participation was voluntary or not. The PDPs that resulted in a change in the domain of consequence had a long timeframe and teachers voluntarily participated. In addition, Sanders et al. (Citation2019) concluded that a longer timeframe resulted in more growth in students’ critical thinking. The PDPs differed in grouping and teaching methods used.

Table 2. PDP- and context-characteristics that stimulate teacher development.

Combining perception and triangulated data

When combining relationships between PDP characteristics and teacher development found in both perception data and triangulated data, we saw that for changes in the personal domain, several teaching methods (i.e. ‘instruction’, ‘collaboration’, ‘feedback’, ‘designing teaching’, ‘modelling’, and ‘micro teaching’) as well as practical relevance, seemed effective. Also, for influencing the domain of practice, the teaching methods ‘instruction’, ‘collaboration’, ‘discussion’, ‘feedback’, and ‘designing teaching’ were found in both perception and triangulated data. For impacting the domain of consequence, only the characteristic ‘multidisciplinary’ grouping was found in both perception and triangulated data.

Discussion

This review was conducted to explore what is known about the relationships between PDP or context characteristics and the changes in teacher development in Higher Education.

Our review, which included 31 articles, showed that PDPs vary widely in terms of design characteristics (RQ1). Moreover, studies paid little attention to context characteristics in measuring PDPs’ results (RQ2). Given the importance of work-environment factors in transfer of learning (e.g. Burke-Smalley & Hutchins, Citation2007, De Rijdt et al., Citation2013), this calls for more research on how context affects the effectiveness of PDPs. Regarding teacher development (RQ3), we found that PDPs can result in a variety of outcomes in teacher development (i.e. change in the personal domain, domain of practice, and domain of consequence). For example, our review showed teacher development in the domain of consequence on the organisation level (38%) and the student level (35%). Interestingly, this is more than the outcomes found in previous reviews (33% and 5% in Steinert et al., Citation2016; 25% and 33% in Stes et al., Citation2010). This suggests that more recent studies do pay more attention to studying the effects of PDPs on the organisation or student levels. However, as the quality of teaching is widely seen as a key factor that positively impacts student learning, more research is needed to evidence the value and impact of PDPs on students learning.

Regarding research question four (i.e. relation between characteristics and domains of teacher development), our study corroborated findings from previous review studies regarding the overall positive impact experienced from PDP characteristics like longitudinal programme design, practical relevance of the content, and several teaching methods (De Rijdt et al., Citation2013, Steinert et al., Citation2016, Stes et al., Citation2010). In addition to the previous reviews, this review showed which PDP characteristics (i.e. external domain) stimulate what domain of teacher development (i.e. change in the personal domain, domain of practice, or domain of consequence). For example, the teaching methods ‘instruction’, ‘collaboration’, ‘feedback’, and ‘designing teaching’ seemed to be related to teacher development in the personal domain and domain of practice. Knowing what domain of teacher development is stimulated with a specific PDP characteristic is just the first step. More research is needed to investigate in what way these characteristics contribute to student learning and how changes in teachers’ knowledge and behaviour affect student learning (Van Veen et al., Citation2012) in order to improve the effectiveness of PDP.

Limitations

The relationships explored in this study are based on a small sample of studies using triangulated data and a wider range of studies using perception data only and thus must be interpreted with care. More research, also using triangulated data, is needed to establish relationships between specific PDP or context characteristics and teacher development. In line with former reviews (e.g. Stes et al., Citation2010) we found that PDPs are only briefly described in half of the articles. We recommend further research to report PDP characteristics by using the components of the curriculum spiderweb (Van den Akker, Citation2003) and specifically mentioning which PDP characteristic is evaluated.

Implications

We used the Interconnected Model of Professional Growth (IMPG; Clarke and Hollingsworth, Citation2002) as an analytical framework, and enriched the model with the curriculum spiderweb (Van den Akker, Citation2003) and inductive codes from the data (see ). The enriched IMPG proved useful to identify specific PDP characteristics and relationships between specific characteristics and domains of teacher development. We recommend future research to further develop the model and study PDP characteristics (i.e. external domain) and context characteristics (i.e. change environment) and their effect on teacher development by using the enriched IMPG (see ).

Figure 4. Enriched IMPG. Italic: indication of a relationship between characteristics and domains of teacher development. Based on the Interconnected model of Professional Growth (Clarke & Hollingsworth, Citation2002) and curriculum spiderweb (Van den Akker, Citation2003).

The enriched IMPG model and the specific relationships identified in our review can help academic developers to design more evidence-informed PDPs with a ‘theory of change’ (i.e. assumed relationship between PDP characteristics and the change in teacher knowledge and/or instruction) in mind (Van Veen et al., Citation2012). In and , examples of relationships are presented and visualised. The following example shows how this can be used: if a PDP intends to stimulate teachers to use more active learning strategies in their classroom (i.e. change in domain of practice), our results suggest incorporating the teaching methods ‘instruction’ and ‘collaboration’ in the design. While instruction and collaboration can be operationalised in a variety of ways in practice, this could mean, for example, that a trainer gives instruction about what active learning looks like in the classroom by showing different examples from practice. Afterwards, participants will observe each other (collaboration) in the classroom and give peer feedback (collaboration) regarding whether and how the teacher used active learning in the classroom.

Conclusion

Studies on PDPs’ effectiveness appeared to vary widely in terms of how PDPs were designed, as well as how effects were measured. Firm conclusions about what is known from research about relationships between specific PDP characteristics and changes in teacher development could therefore not be drawn. However, the review yielded an enriched model (Interconnected Model of Professional Growth) on pedagogical development of higher education teachers, which may benefit future studies, as well as the design of more evidence-informed PDPs in practice.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (210.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2023.2233471

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marloes Vreekamp

Marloes Vreekamp is a PhD student at the Education and Learning Science (ELS) chair group of Wageningen University & Research (WUR) and educational trainer and advisor at the WUR. Her research is focused on pedagogical development programmes in higher education institutes.

Judith T. M. Gulikers

Judith Gulikers is an associate professor at the ELS chair group (WUR). Her research, innovation, and professional development activities are focused on formative assessment, assessment of ‘difficult things’ (like boundary crossing), assessment in learning lines, and programmatic assessment.

Piety R. Runhaar

Piety Runhaar is an associate professor at the ELS chair group (WUR). Her research is focused on professional development of teachers and teacher teams and the roles of Human Resources Management and leadership in stimulating professional development in various educational contexts.

Perry J. Den Brok

Perry den Brok is a professor and chair in ELS (WUR). His research is focused on educational innovation, rich and innovative learning environments, teacher learning and professional development. Perry is also the chair of the 4TU.Centre for Engineering Education, a centre that initiates, supports, and studies course and curricular innovations at the four universities of technology in the Netherlands.

Notes

1. Referring to the outcome domains as described by Clarke and Hollingsworth (Citation2002): personal domain, domain of practice, and domain of consequence.

2. Decibel Analysis for Research in Teaching (DART) tool – a tool that measures classroom sounds to classify teaching practices in college science courses.

References

- *Adnan, M., Kalelioglu, F., & Gulbahar, Y. (2017). Assessment of a multinational online faculty development program on online teaching: Reflections of candidate E-Tutors. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.285708

- *Ansyari, M. F. (2015). Designing and evaluating a professional development programme for basic technology integration in English as a foreign language (EFL) classrooms. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(6), 699–712. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1675 .

- *Bain, Y., Brosnan, K., & McGuigan, A. (2019). Transforming practice, transforming practitioners: Reflections on the TQFE in Scotland. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 24(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2018.1526907.

- Booth, A., & Carroll, C. (2015). How to build up the actionable knowledge base: The role of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Quality & Safety, 24(11), 700–708. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003642

- Burke-Smalley, L., & Hutchins, H. (2007). Training transfer: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 6(3), 263–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484307303035

- Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 947–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X-02-00053-7

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklis-2018.pdfhttps://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf

- De Rijdt, C., Stess, A., Van der Vleuten, C., & Dochy, F. (2013). Influencing variables and moderators of transfer of learning to the workplace within the area of staff development in higher education: Research review. Educational Research Review, 8, 48–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2012.05.007

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

- *Donnelly, R. (2019f). Supporting pedagogic innovators in professional practice through applied eLearning. E-Learning & Digital Media, 16(4), 301–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019836317.

- *Fong, C. J., Gilmore, J., Pinder-Grover, T., & Hatcher, M. (2019). Examining the impact of four teaching development programmes for engineering teaching assistants. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(3), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1361517.

- Graham, R. (2018). The career framework for university teaching: Background and overview. Royal academy of engineering. https://www.teachingframework.com/resources/Career-Framework-University-Teaching-April-2018.pdf

- *Gunbay, E. B., & Mede, E. (2017). Implementing authentic materials through Critical Friends Group (CFG): A case from Turkey. The Qualitative Report, 22(11), 3055–3074. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2744

- *Gunersel, A. B., & Etienne, M. (2014). The impact of a faculty training program on teaching conceptions and strategies. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 26(3), 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440701604898.

- *Hilpert, J. C., & Husman, J. (2017). Instructional improvement and student engagement in post-secondary engineering courses: The complexity underlying small effect sizes. Educational Psychology, 37(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2016.1241379.

- *Jääskelä, P., Häkkinen, P., & Rasku-Puttonen, H. (2017). Supporting and constraining factors in the development of university teaching experienced by teachers. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(6), 655–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1273206.

- *Jarvis, C. (2019). The art of freedom in HE teacher development. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1456422.

- *Kensington-Miller, B. (2019). ‘My attention shifted from the material I was teaching to student learning’: The impact of a community of practice on teacher development for new international academics. Professional Development in Education, 47(5), 870–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1677746

- *Lamers, A. M., & Admiraal, W. F. (2018). Moving out of their comfort zones: Enhancing teaching practice in transnational education. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1399133.

- *Langdon, J. L., & Wittenberg, M. (2019). Need supportive instructor training: Perspectives from graduate teaching assistants in a college/university physical activity program. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1530748.

- *Lauridsen, K. M., & Lauridsen, O. (2018). Teacher capabilities in a multicultural educational environment: An analysis of the impact of a professional development project. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(2), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1357557.

- *Lavis, C. C., Williams, K. A., Fallin, J., Barnes, P. K., Fishback, S. J., & Thien, S. (2016). Assessing a faculty development program for the adoption of brain-based learning strategies. The Journal of Faculty Development, 30(1), 57–69.

- *McLeod, P., Steinert, Y., Capek, R., Chalk, C., Brawer, J., Ruhe, V., & Barnett, B. (2013). Peer review: An effective approach to cultivating lecturing virtuosity. Medical Teacher, 35(4), 1046–1051. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.733460

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- *Murthy, S., Iyer, S., & Warriem, J. (2015). ET4ET: A large-scale faculty professional development program on effective integration of educational technology. Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 16–28.

- *Nevgi, A., & Löfström, E. (2015). The development of academics’ teacher identity: Enhancing reflection and task perception through a university teacher development programme. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.01.003

- *Owens, M. T., Trujillo, G., Seidel, S. B., Harrison, C. D., Farrar, K. M., Benton, H. P. , and Tanner, K. D. (2018). Collectively improving our teaching: Attempting biology department-wide professional development in scientific teaching. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 17(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-06-0106

- *Owusu-Agyeman, Y., Larbi-Siaw, O., Brenya, B., & Anyidoho, A. (2017). An embedded fuzzy analytic hierarchy process for evaluating lecturers’ conceptions of teaching and learning. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 55, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.07.001

- *Pekkarinen, V., & Hirsto, L. (2017). University lecturers’ experiences of and reflections on the development of their pedagogical competency. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(6), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1188148.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H., Petticrew, M., Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887

- *Sanders, A. L., Snyder, S. J., & Mathews, S.-K. (2019). Fostering student motivation to think critically: Critical thinking dispositions in higher education. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 30(2), 133–160.

- *Sonntag, U., Peters, H., Schnabel, K. P., & Breckwoldt, J. (2017). 10 years of didactic training for novices in medical education at Charite. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 34(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001116.

- *Stains, M., Pilarz, M., & Chakraverty, D. (2015). Short and long-term impacts of the cottrell scholars collaborative new faculty workshop. Journal of Chemical Education, 92(9), 1466–1476. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00324.

- Steinert, Y., Mann, K., Anderson, B., Barnett, B. M., Centeno, A., Naismith, L., Prideaux, D., Spencer, J., Tullo, E., Viggiano, T., Ward, H., & Dolmans, D. (2016). A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Medical Teacher, 38(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2016.1181851

- Stes, A., Min-Leliveld, M., Gijbels, D., & Van Petegem, P. (2010). The impact of instructional development in higher education: The state-of-the-art of the research. Educational Research Review, 5(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.07.001

- *Stewart, M. (2014). Making sense of a teaching programme for university academics: Exploring the longer-term effects. Teaching and Teacher Education, 38, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.006

- *Toding, M., & Venesaar, U. (2018). Discovering and developing conceptual understanding of teaching and learning in entrepreneurship lecturers. Education & Training, 60(7/8), 696–718. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-07-2017-0101

- *Tsui, C. (2018). Teacher efficacy: A case study of faculty beliefs in an English-medium instruction teacher training program. Taiwan Journal of TESOL, 15(1), 101–128. https://doi.org/10.30397/TJTESOL.201804_15(1).0004.

- Van den Akker, J. (2003). Curriculum perspectives: An introduction. In J. Van den Akker, W. Kuiper, & U. Hameyer (Eds.), Curriculum landscapes and trends (pp. 1–10). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-1205-7_1

- Van Driel, J. H., Meirink, J. A., van Veen, K., & Zwart, R. C. (2012). Current trends and missing links in studies on teacher professional development in science education: A review of design features and quality of research. Studies in Science Education, 48(2), 129–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2012.738020

- Van Veen, K., Zwart, R., & Meirink, J. (2012). What makes teacher professional development effective? A literature review. In M. Kooy & K. van Veen (Eds.), Teacher learning that matters (pp. 23–41). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203805879

- *Van Wyk, C., Nel, M. M., & van Zyl, G. J. (2019). Practise what you teach: Lessons learnt by newly appointed lecturers in medical education. African Journal of Health Professions Education, 11(2), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2019.v11i2.1115.

- *Wilson, G., Myat, P., & Purdy, J. (2018). Increasing access to professional learning for academic staff through open educational resources and authentic design. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 15(2), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.15.2.5

- *Wurgler, E., Van Heuvelen, J. S., Rohrman, S., Loehr, A., & Grace, M. K. (2014). The perceived benefits of a preparing future faculty program and its effect on job satisfaction, confidence, and competence. Teaching Sociology, 42(1), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055x13507782.

- *Zheng, M., Bender, D., & Nadershahi, N. (2017). Faculty professional development in emergent pedagogies for instructional innovation in dental education. European Journal of Dental Education, 21(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12180