ABSTRACT

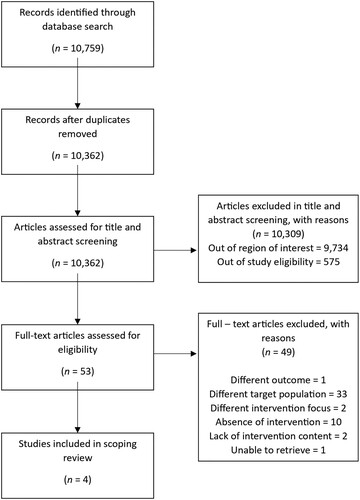

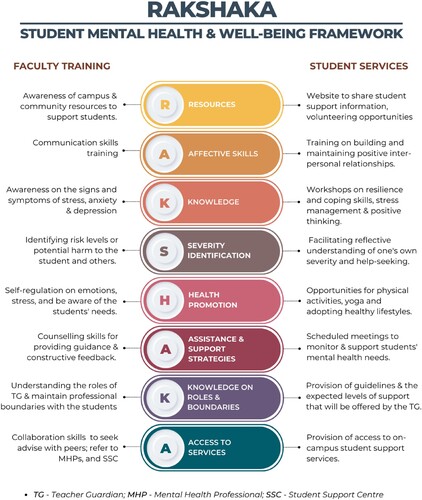

Students in higher education institutes (HEI) often face mental health issues that challenge their well-being. Faculty members, as crucial points of contact for academic programmes, play a pivotal role in supporting their well-being. Some HEIs offer training programmes to support the faculty in this role. We conducted a scoping review to examine such faculty training programmes by considering data from four of the 10,362 studies and 21 university sources for analysis. Synthesizing the data, we identified the components, format, mode, and evaluation of faculty training programmes. The components were based on the RAKSHAKA framework, which includes resources, affective skills, knowledge in recognising students in distress, severity identification of mental health issues, health promotion, assistance and support strategies, knowledge on roles and boundaries, and access to student services. The proposed framework would provide academics and HEI administrators a reference for implementing faculty training programmes to support student mental health and well-being.

Introduction

Students pursuing higher education are primarily emerging adults, moving through a critical developmental period defined by greater autonomy and responsibility, family separation, and individuation (Duffy et al. Citation2019). During this transition, they develop physically, emotionally, and personally (Sharma and Sharma Citation2018) while adjusting to a new learning environment (Cleary, Walter, and Jackson Citation2011). Students who have difficulties coping with the transition often face short-term challenges in engaging in regular academic activities, resulting in a shortage of attendance, poor academic performance, and academic attrition in the short term and an increased likelihood of experiencing mental health issues like depression and anxiety in the long-term (Jaisoorya Citation2021). For example, problems connecting with peers at the university and negative social encounters lead students to re-evaluate their social skills, leading to a sense of loneliness (Matthews et al. Citation2019). Such mental health problems can negatively impact the student's ability to engage in academic activities, thus affecting their academic concentration performance (Eisenberg et al. Citation2009). These difficulties can further lead to reduced employment and personal income among this cohort (Hernández-Torrano et al. Citation2020). Thus, during this transition period (Gall, Evans, and Bellerose Citation2000), the universities can provide opportunities for accessible interventions to support and nurture the student's mental health and well-being (Campbell et al. Citation2022), targeting to optimise their academic performance and to prevent student attrition.

Reducing the burden of mental illness is going to require a shift from reactive to proactive approaches (Thomas et al. Citation2016). For universities, this will involve following a whole-university or settings-based approach (Fernandez et al. Citation2016; Hughes and Byrom Citation2019; Upsher et al. Citation2022), embedding initiatives to support student mental health within the day-to-day student experience. Pedagogy and the curriculum are the only guaranteed point of contact between universities and their students (Upsher et al. Citation2022). Faculty, in their role as liaisons of the curriculum and the students through the delivery of instructional content, provide an opportunity for the students to build connections with them. Where there is a connection between faculty members and students, the student may be more willing to reach out for support; young adults tend to prioritise seeking help from existing known contacts (Brown et al. Citation2016; Rickwood et al. Citation2005). This tendency of developing a natural connection with the faculty by the students provides faculty with an excellent opportunity to intervene with the students at their developmental stages of mental health problems and offer necessary support or resources (Dawson et al. Citation2006; Yung et al. Citation2007). However, this ‘frontline’ role is challenging, with faculty raising concerns about their ability to respond to student mental health problems (Hughes and Byrom Citation2019).

The World Mental Health Survey of college students across 21 countries found that approximately 20% of these individuals experienced mental disorders (Auerbach et al. Citation2018). One other study reported that the university student population faces a higher level of mental health problems as compared to other peers in the community (Cvetkovski, Reavley, and Jorm Citation2012; Stallman Citation2010), which continues to increase at an alarming rate (Lipson et al. Citation2022). Considering the high rate of mental health distress among students at higher education institutes (HEIs), it is essential to equip the faculty with the skills and resources required to respond (Gulliver et al. Citation2018). Many universities have started adopting faculty training programmes and providing faculty with resources to help them support their students. Universities often ask faculty to determine risks, differentiating between day-to-day emotional ups and downs and emergent mental illness (Hughes and Byrom Citation2019). The faculty needs to be aware of the myriad support services available and the process for accessing them. Finally, the faculty must be able to encourage students to seek further help, moving from talking to a known and trusted contact to an unknown, new support service (Hughes and Byrom Citation2019).

A lack of prior knowledge of mental health problems was a significant factor leading to educators feeling unprepared to support students (Constantinou et al. Citation2022). Educators are concerned about the lack of clear boundaries for their roles as providers of pastoral support (Hughes and Byrom Citation2019; Payne Citation2022; Spear, Morey, and Van Steen Citation2021). Gauging one's professional and academic duty while supporting students regarding mental health matters becomes difficult. Educators may also feel that managing student mental health is not a part of their role as faculty member (Gulliver et al. Citation2018). Educators find it challenging to implement confidentiality protocols and gain students’ consent to share severe concerns with the concerned university services (Gulliver et al. Citation2018; Payne Citation2022).

While the need for faculty training increases, the scope and the evidence on the existing faculty training programmes is unknown. In this context, it becomes imperative to identify the components and develop a core curriculum for the faculty training programme on student mental health and well-being. This scoping review aimed to identify faculty development programmes to improve mental health literacy and support and nurture student mental health in HEIs. This review explores and offers a conceptual framework highlighting the core components of such existing faculty training programmes in fostering the knowledge and skills of the faculty on student mental health.

Methods

Study protocol

Given the multidimensional nature of faculty development in student mental health and well-being, a scoping review study design offers an appropriate method to survey and synthesise the literature comprehensively, encompassing a wide range of interventions, strategies, and approaches utilised in different educational contexts (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010). We followed the steps enumerated in the Arksey and O'Malley framework for conducting scoping reviews (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005).

The investigators employed the SPIDER framework for scoping reviews for the literature search, which offers a structured approach to scoping reviews, defining the sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type, and guiding the selection process (Cooke, Smith, and Booth Citation2012; Methley et al. Citation2014) (see ). By specifying each framework component, we identified relevant studies that address the specific aspects of faculty development in student mental health and well-being within higher education settings. The protocol has been registered in the Open Science Framework before we began our scoping review. We report our study using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al. Citation2018).

Table 1. SPIDER framework for scoping reviews.

Search strategy

The investigators developed a search strategy using appropriate keywords to include components of the SPIDER framework to search the databases (Supplementary Material S1). Four electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest, were searched limited to the English language for a period of ten years (Jan 2013 – Dec 2022).

Selection of sources of evidence

The investigators imported the search results to the Rayyan software, de-duplicated the searched records, screened the title and abstract of 10,362 studies for eligibility, and identified 53 articles relevant for subsequent full-text screening (see ).

While two researchers independently screened the full-text articles against their inclusion criteria, the other researchers resolved any discrepancies in the screening process. Heterogeneity and a lack of robust scientific methodology in the articles of interest were the main sources of discrepancies challenging the screening and selection of articles among the investigators. The challenges of the screening and selection processes were resolved by an agreement to include articles of all types, highlighting the focus of this review. Despite the extensive screening process, the investigators agreed to include only four studies for the review synthesis. The findings from the literature review synthesis have been tabulated in the Supplementary Material S2.

At this point, the investigators realised that the faculty training programmes implemented at the university level have their faculty as a potential audience. The HEIs have not followed the methodological approach to report and publish it as an article in the journal. The dearth of reported studies on faculty training programmes on student mental health and well-being prompted the investigators to scope, in addition to the literature search described above, to hand search relevant information from the websites of globally ranked top 50 universities (QS World University Rankings Citation2023) as on December 31, 2022. A scoping review by Pollock et al., (Citation2022) reported a similar search strategy combining the website search as an additional source for the scoping review. While nineteen websites provided open-access information about their faculty training programme, the investigators contacted the other universities for such information. Only two university contacts responded to the request by providing the details of their university's faculty training programme. The investigators then tabulated the relevant data from the available information from 21 university sources (website search and university contacts) (see Supplementary Material S3).

Synthesis of results

The investigators identified and selected eight themes around student mental health and well-being a priori through a preliminary search from the broader literature and university websites, which informed the review process. Based on these themes, the investigators constructed a conceptual framework, RAKSHAKA, an acronym of the eight themes viz., Resources, Affective skills, Knowledge of mental health issues, Severity identification, Health promotion, Assistance & support strategies, Knowledge of roles and boundaries, and Access to services (). The investigators used the RAKSHAKA framework to review and synthesise the sources of information from the included studies and the university websites, which detail faculty training and student services in the context of student mental health and well-being. The investigators developed a data extraction format (see supplementary material S2 and S3) to chart the data from the information sources in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The investigators screened the sources for any emergent themes while reviewing, focusing on the components of faculty training on student mental health and well-being. However, the investigators did not find any emergent themes. Therefore, the investigators have not used any analysis methodology.

Results

General characteristics of sources of evidence

Of the three empirical studies and one non-empirical study, two included the context of a healthcare education setting, and two other studies did not specify the context. Four studies included in the review represent different geographical locations, one each from the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada. Most of the identified universities are in the North American (n = 11) and European regions (n = 7), while three are in the Asian and Australian continents.

Synthesising the information from the data sources, the investigators mapped the information to the eight interrelated themes of the RAKSHAKA framework on the components of faculty training on student mental health and well-being. The summary of the review synthesis is presented in the .

Table 2. Synthesis of information reviewed from the sources.

Components of the training programme

Resources (for faculty)

The sources reviewed provide the details on the required resources for the faculty to undertake student support practices. The resources were diverse in the form of faculty guides, standard operating protocols and procedures, reporting systems, emergency contact information for seeking and directing the students for assistance and support within and outside campus, information videos and flyers, internal and external information weblinks, and mobile applications, to name a few. The Counselling and Mental Health Centre (CMHC) at the University of Texas at Austin conducted a pilot programme called the Well-being in Learning Environments (WBLE), where the WBLE staff developed a faculty guide made available for the faculty through a weblink (Wash et al. Citation2021). The guide contained specific conditions of well-being and suggested activities to fulfil the same. Similarly, McMaster University published the Professor Hippo-on-Campus mental health education programme on its website for its faculty and staff to support and promote student mental health. (Halladay et al. Citation2022). Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) used information handouts, flowcharts covering the student referral pathways, and discussion material for the videos for the faculty as workshop resources in their faculty training programmes.

Most universities provide resources to the faculty in the form of faculty guides on their websites. Such universities have guidelines available on their respective counselling and psychological services (CAPS) platforms for students. For instance, the University of Manchester published a flowchart of standard operating procedures (SOPs) delineating professional consultation services available for students according to their needs and urgency. The University of Michigan followed a similar approach where their CAPS webpage covers the referral procedure for students according to the situation (safety issues and unusual behaviour). Like the others, Cornell University also lists the professional services available for student mental health support on its website while conducting regular mental health training courses for its faculty.

Affective skills (of faculty in holding engaging conversations)

The affective skills of the faculty manifested in different ways. Halladay et al. (Citation2022) and Wash et al. (Citation2021) mentioned tips for acknowledging emotions by recommending communication strategies. In contrast, Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) included practical steps such as acknowledging students’ emotions, creating a positive learning environment, recognising and responding to distressed students, and suggesting techniques to cope with their own stress. Similarly, Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021) recommend engaging strategies such as active listening and open-ended questions to gain greater clarity regarding distressed students’ experiences and foster more trusting and non-judgmental relationships between staff and students.

While most universities stressed providing access points in the university for professional mental health support, some also mentioned affective listening tips to hold conversations with distressed students. For instance, the University of Edinburgh has a guide published on its website, which provides standard operating procedures (SOPs) for assisting students in non-urgent situations. Particularly, techniques fostering active listening and sympathetic responses in various situations involving mental health concerns have been enlisted for the faculty. In their guide, Harvard University also provides a list of behaviours for the faculty, like maintaining eye contact, responding with calmness, and manner of asking questions to promote affective listening skills of the faculty while supporting students.

Knowledge and skills (of faculty in recognising students in distress)

While both Wash et al. (Citation2021) and Halladay et al. (Citation2022) build from a holistic approach, Halladay et al. (Citation2022) consider the elements of student life that may exacerbate mental health problems, such as accommodation difficulties and the impact of stigma. Halladay et al. (Citation2022) presented a Mental Health Education Program (Professor Hippo-on-Campus), including modules centred on providing knowledge for university faculty and staff about mental health disorders, notably the Keyes Dual Continuum Model of Mental Health (Keyes Citation2002). Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) emphasise the societal and cultural issues that may impact students, and like Halladay et al. (Citation2022), their training also addressed the skill of assessing mental health disorders and their associated risks. Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021) briefly mention signs to look out for to identify a student with acute mental health episodes while focussing more on how to deal with them.

Most globally ranked universities curated resources for the faculty to guide recognising students in distress. One such example is the ‘i care’ initiative by the University of Pennsylvania, which offers resources for the faculty to recognise stress, distress and crisis among students and provides critical do's and don'ts of this process. John Hopkins University also provides a faculty guide in identifying the behavioural, physical, cognitive, and emotional signs of students facing psychological distress. Markedly, the guide directs the faculty to assist the students with appropriate help available across the university for the issues identified. Other universities, like the University of Oxford and Cornell University, host frequent workshops and training sessions for faculty members to understand the symptoms of distress among students.

Severity identification (skills of the faculty)

Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) addressed issues of severity analysis of mental health via video-triggered discussions on identifying cases involving the risk of suicide. Furthermore, the Professor Hippo-on-Campus module (Halladay et al. Citation2022) trained the faculty to rate the severity of distress under their ‘5 R’ protocol for responding to students in distress and difficulty.

Information on assisting faculty with signs of severe distress was also a point of focus for some universities. For instance, in their crimson folder guide for faculty, Harvard University lists student distress under three categories (mild, moderate, and severe), with behaviours indicating each. Importantly, these behaviours are related to the students’ everyday classroom activities, providing faculty with areas to look out for. The guidance provided by Hong Kong University primarily focuses on recognising signs of suicide and psychosis among students. Similarly, a faculty guide by the Australian National University also assists the faculty in identifying the severity of distress among students based on the risk of suicide and self-harm.

Health promotion (strategic skills of faculty directing the students to seek health promotion)

Opting for a proactive approach to supporting students with distress, Wash et al. (Citation2021) and Halladay et al. (Citation2022) included aspects of health promotion in their training by creating a safe and open environment for discussing matters of mental health to reduce stigma. As a proactive strategy for promoting students’ mental health and well-being, academics should foster an accommodative and inclusive classroom environment. The training programme reported by Wash et al. (Citation2021) suggests creating an environment that ensures open communication in the classroom and self-care practices to promote mental health for the students. They addressed specific strategies and resources centred around engaging and motivating students, with faculty utilising a holistic well-being lens to guide their syllabus. The core competency identified in their module is the ability of the academics to create an effective learning environment that fosters mindfulness, gratitude, resilience, and the use of affective skills as conditions for well-being among students. Similarly, Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) suggested creating a safe environment in the classroom to foster discussion about sensitive matters of mental health and well-being. In their training, Halladay et al. (Citation2022) also fostered health promotion by suggesting the creation of a positive mental health environment while supporting inclusive learning by reducing biases and stigmas.

A common theme among a few universities was creating an environment conducive to mental health. The University of Manchester endeavours to promote proactive communication concerning mental health and well-being while helping the faculty promote positive mental health behaviours among students. The University directs its faculty to ensure that the information about professional services across campus is readily available to the students to access help for their mental health issues in an attempt to reduce stigma regarding the same. The University of Michigan, in its guide, directs the faculty to promote mental health awareness in the classroom and structure the classes to reflect the faculty's approach toward supporting students’ mental health.

Assistance and support resources (The faculty skills to offer appropriate student assistance and use support resources)

Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021) and Halladay et al. (Citation2022) mentioned tips for acknowledging emotions by recommending communication strategies. For example, Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021) suggested that if students feel overwhelmed with their issues, faculty should normalise the distress by reassuring them that such emotional responses are an expected part of difficult circumstances. Other studies also report similar support strategies. Suggestions to reduce distress, coping strategies, and signposting were common themes identified (Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu Citation2016; Halladay et al. Citation2022; Hodgson and Bretherton Citation2021). However, only Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) included a transparent student management system in their suggestions for supportive practices. Additionally, Wash et al. (Citation2021) only suggested everyday classroom activities to improve aspects of student's well-being like resilience, gratitude, and inclusivity.

The information on student assistance and support strategies is one of the common features in the materials provided by the universities. For example, the University of Michigan offers helpful tips for conducting supportive conversations with students in case the faculty is unaware of this process. Such tips have been listed based on different situations that the faculty may encounter with the students, a notable situation being the refusal of students to undertake professional help. The University of Edinburgh's faculty guide on supporting students lists various modes of action for the faculty to undertake while helping students, including providing practical advice and making referrals. Likewise, Hong Kong University provides training to the faculty to assist multiple mental health problems like depression, academic setbacks, substance use disorders and adjustment difficulties among students.

Knowledge on roles and boundaries (of the faculty)

The synthesis identified academics’ roles, responsibilities, and boundaries in offering student support as a theme. Even though all studies have included training components around this theme, two studies have elaborated on upholding the boundaries as a faculty while supporting students. Wash et al. (Citation2021) underlined protocols for navigating difficult dialogues in situations where boundaries are difficult to maintain. The authors suggest laying down clear expectations for the students by the faculty while supporting the students. Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021) highlight the differentiating role of academics as educators and clinical supervisors involved in teaching and clinical training while providing student support in the context of a medical school programme. The other studies, too, have highlighted clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the academics while offering student support as a component in the training programmes offered; however, they did not explain the scope further (Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu Citation2016; Halladay et al. Citation2022). Notedly, Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) quote the example of the possibility of students disclosing the experience of sexual harassment with academics, which poses a challenge to academics to limit confidentiality. The proposed training equips the academics to investigate disclosures and ambiguous presentations.

Providing clear roles and boundaries for the faculty while offering support to students was an essential part of the resources offered by some universities. For example, Cambridge University clarifies the faculty's role in high-risk situations, which advises the faculty to be aware of their limits and seek additional support from available services. Similarly, Johns Hopkins University also reminds the faculty about their limits in providing support and clarifies the breach of confidentiality allowed in cases of emergencies like sexual misconduct and discrimination.

Access to support services (collaboration skills of the faculty in directing the students to access support services)

The synthesis of information sources also details how the faculty can signpost the students’ mental health issues. Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021), while not providing individual sources for signposting, discussed the importance of the same and the different ways in which they are made available (peer welfare teams, education advice, etc.). It makes a valuable suggestion of providing Standard Operation Procedures (SOP) in the form of flow charts to effectively refer students for their respective concerns. Both Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) and Halladay et al. (Citation2022) included resources for educators to navigate professional student mental health support across the University, while the training by Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) also included web-based mental health support resources available freely.

It is important to note that all universities provide a set of professional help services available and the manner of referring students to them for the faculty. Like most universities, the University of California and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have information for the faculty about various centres offering emotional support and wellness to students. Some universities also included self-help resources for students on their websites. For instance, Standford University provides self-care strategies in the form of books and audio recordings while also including various self-care videos for issues surrounding sleep and stress. Similarly, Imperial College London and the University of British Columbia have uploaded self-help resources for students with detailed explanations of signs and symptoms of various mental health problems commonly associated with this cohort.

Format of the training programme

The training modules have incorporated videos, case-based scenarios, avatars (Halladay et al. Citation2022), and practical examples for the faculty to relate to and have an immersive experience with the contents. Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) included video scenarios addressing discussions involving sexual harassment and related concerns with confidentiality. More examples included ways of helping students adapt to new environments and assessing the risk of issues presented. The other studies included practical examples of communicating with distressed students (Halladay et al. Citation2022; Hodgson and Bretherton Citation2021; Wash et al. Citation2021). One intervention focused on instilling trust and sensitivity while holding conversations with students; it provided practical examples for managing situations of emotions (Hodgson and Bretherton Citation2021), such as encouraging moments of silence and avoiding forcing conversations.

The format of the information offered for the faculty was broadly similar across all universities. Most universities, such as Standford University, Harvard University, and the University of Toronto, provided resources to the faculty in a readable format. However, Standford University listed information about the ways of coping in video and audio formats as well. Additionally, Cornell University represented information in the form of PowerPoint presentations during their workshops on student mental health and well-being.

Modes of the training programme

While Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021) only provided a list of tips the faculty can implement, Wash et al. (Citation2021) developed a guidebook made available for the faculty through a web link. Halladay et al. (Citation2022) provided a two-hour workshop and three hours of asynchronous online modules to increase the acceptability of their training. Similarly, Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) also disseminated their module through a 90-minute workshop, which included activities and discussions about anonymous scenarios related to student mental health issues.

All the information from the university sources was in the form of web pages under the student centre tab. Universities like Johns Hopkins University and Harvard University provide all the necessary information to extend support to students as faculty guides on their websites. Other HEIs like Cornell University, Oxford University, and Hong Kong University undertake training sessions for the faculty, focussing primarily on advancing knowledge about mental health issues along with the available resources at the university. Such trainings are either paid in-person workshop events or free asynchronous online modules that faculty can access.

Evaluation of the training programme

The information on programme evaluation of the training programme was available in only two of the four articles evaluating the effectiveness of implementing mental health training programmes for faculty members. The study on Professor Hippo-on-Campus programme reports significant improvements in faculty attitudes, knowledge, and stigma toward student mental health issues (Halladay et al. Citation2022). The other study reported positive results in evaluating the academic practices of the faculty in their classroom, including mindfulness, group discussion, inclusive language and teaching practices, and open discussion of mental health issues and resources (Wash et al. Citation2021). The other two articles included in this review, while illustrating the training components, did not evaluate its implementation as Hodgson and Bretherton (Citation2021) only provided expert advice on handling student mental health issues, and Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu (Citation2016) focussed more on evaluating the mode of delivery of training.

Discussion

The lack of literature on university faculty training programmes on student mental health and well-being contrasts with the volume of such training reports for school teachers, which were excluded during the full-text screening (see ). It is further mismatched by the level of concern in the prevalence of mental health issues among university students (Auerbach et al. Citation2018; Browne, Munro, and Cass Citation2017; Chaudhary et al. Citation2021) and the lack of capacity building of the faculty in responding to student distress (Dittakavi Citation2022; Gulliver et al. Citation2018; Hughes and Byrom Citation2019).

Overall, most of the training programmes addressed a common element in their content, which included advice for faculty on recognising and responding to students seeking help. The common suggestion to address the mental health issues revolved around effective conversations with the students and signposting. Additionally, a few training sessions addressed the roles and responsibilities of the faculty members while including practical examples to explain the contents of the training module. The majority of the information sources also address specific affective skills required to undertake effective conversations with students with mental health issues.

The primary purpose of this scoping review is to identify the components and core curriculum for the faculty training programme on student mental health and well-being. While reviewing the broader literature on the components of the training programme, the investigators identified eight interrelated themes. The investigators were intrigued to relate these themes to a conceptual model aligning the university's faculty development strategies on promoting student mental health and well-being for effective student support. Further, the investigators were intrigued that the name of this conceptual model, by itself, should reflect the essence of faculty training and student services around student mental health and well-being at our university. The investigators, reorganising the a priori themes, identified RAKSHAKA as a nomenclature of the conceptual framework, an acronym, and a common noun that reflects the faculty role as ‘Teacher Guardian’ in providing student support. RAKSHAKA, in vernacular Kannada language, means ‘Guardian’ or ‘Protector’. Thus, the acronym RAKSHAKA synchronises and aligns the themes around student mental health and well-being in a higher education setting. The investigators constructed this thematic framework under two dimensions (). While the dimension of the faculty training is the focus of this scoping review, we believe the effectiveness of the mental health programme can be enhanced only when the dimension of student services aligns with the components of faculty training on student mental health.

A thematic analytical study sharing the student perspectives on issues and challenges around university student mental health and well-being services, reports the recommendations of the student panels on support services which cites the need for an overarching framework that integrates the policies, procedures, training, and resources linking faculty training and support services (Priestley et al. Citation2022). The RAKSHAKA incorporates the dimensions of faculty training and student support services, thus providing an overarching framework around student mental health and well-being in the higher education setting. Several universities have adopted similar overarching models and frameworks. A study reports the findings of the ABC-uni framework, an adaptation of ABC (act, belong, commit) of mental health programmes (Nielsen et al. Citation2023). One of the critical elements of ABC-uni involves staff capacity building on student mental health promotion. Several universities have adopted the 5-step ALGEE framework of the Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training programme offered by the National Council for Mental Well-being (NCMW) for training its faculty (Mental Health First Aid USA Citation2021).

The proposed RAKSHAKA framework can serve several purposes. It delineates individually and together links the components of the faculty training programme and student support services. The faculty training initiatives using this framework could enhance opportunities for faculty to collaborate as a community of practice in innovating pedagogical approaches that support and nurture positive student learning environments. The framework can be useful in developing the faculty competencies to effectively support the students. The framework can also guide the HEI administrators in aligning the strategic plans, policies, and practices to the student support initiatives. One can view the RAKSHAKA framework through two different lenses. RAKSHAKA, when viewed through the lens of a service provider, the University empowers its faculty as RAKSHAKA in identifying students in distress and offering mental health support. RAKSHAKA, when viewed through the lens of service training, the university should train its faculty on the various components identified in the mental health literacy programme to provide adequate student support.

The synthesised conceptual framework covers aspects of recognising signs and symptoms and assessing the severity of those symptoms (Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu Citation2016; Halladay et al. Citation2022), using effective communication skills to respond to students who require support (Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu Citation2016; Halladay et al. Citation2022; Hodgson and Bretherton Citation2021; Wash et al. Citation2021) signposting resources in case of severe and emergency situations (Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu Citation2016; Hodgson and Bretherton Citation2021), upholding one's boundaries as a faculty member (Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu Citation2016; Halladay et al. Citation2022; Hodgson and Bretherton Citation2021; Wash et al. Citation2021) and taking a proactive approach to health promotion (Flynn, Woodward-Kron, and Hu Citation2016; Halladay et al. Citation2022; Wash et al. Citation2021).

Gatekeeper training focussed on enhancing mental health literacy (MHL) to identify and communicate with individuals experiencing distress has been deemed necessary (Halladay et al. Citation2022; Upsher et al. Citation2022). The conceptual framework presented in this review covers all the aspects defining MHL (Kutcher et al. Citation2016), including improving knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in dealing with mental health issues. Additionally, it has been stated that, the nature of MHL programmes requires them to be integrated into the context of organizations implementing the same (Kelly, Anthony, and Jorm Citation2007). The training and service dimensions of the proposed framework list elements which can be easily modified to be inculcated by HEIs in concordance to their available services and resources.

Limitations (of review process and training evidence)

One major limitation encountered is the limited availability of published peer-reviewed literature on the faculty training programmes focusing on student mental health and well-being. Further, there is limited open-access information on such faculty training programmes on the university websites, and we could include only scope 21 sources of information from the top 50 globally ranked universities. Another major limitation is that the investigators could not consolidate the effectiveness of the faculty training programmes due to the heterogeneity in the study design. Only two of the four studies discussed in this review reported the characteristics of the sample population. This limitation echoes concerns raised more generally about the quality of reporting mental health studies in higher education (Upsher et al. Citation2022).

Suggestions for future research

The current review reflects the lack of peer-reviewed literature on university faculty training programmes on student mental health and well-being. Future research should extensively focus on finding the effectiveness of faculty training programmes and their impact on student mental health outcomes and academic performance. The investigators plan to develop the RAKSHAKA training module, implement the training programme for its faculty, and report its effectiveness. Future studies should explore the utility of this conceptual framework in providing student mental health services in the context of higher education settings. As student support and assistance is one of the quality assurance mandates of the universities, future research should focus on reviewing the faculty training information from the top 500 globally ranked universities, which would represent universities from regions world-wide.

Conclusion

We identified and synthesised the themes around the core contents of the existing faculty training programmes and the competencies of faculty in providing student mental health services. We propose the RAKSHAKA framework on student mental health and well-being, which other global universities can adapt to align the faculty training and student support services around student mental health and well-being.

Supplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (30.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arush Goel

Mr. Arush Goel worked as a project assistant for project RAKSHAKA with the Department of Physiotherapy of Manipal College of Health Professions, Manipal Academy of Higher Education. His research interests are driven by the socio-cultural constraints impacting student mental health in higher education institutes, and he seeks to investigate ways of addressing students’ mental health challenges. Prior to this, he completed his BSc. in Psychology (Honours) from CHRIST (Deemed to be University) along with an MSc. in Clinical Psychology from Manipal Academy of Higher Education.

Rubbia Ali

Ms. Rubbia Ali, who is currently pursuing her DClinPsy, joined Kings College London in 2021, where she worked as a researcher assisting on the ‘Safewards in Children and Young People’ project. She holds a Masters in Psychiatric Research along with a PGDip. in Cultural Psychology and Psychiatry. She has also worked as a mental health worker with NHS services while additionally supporting mental wellbeing of vulnerable groups in both within the UK and abroad countries like Nepal, Turkey, Morocco, Tanzania and Greece.

Rebecca Upsher

Dr. Rebecca Upsher is a Lecturer in Psychology (Education) at Kings College London where she actively supports research and teaching practices to enhance university student wellbeing. Dr Upsher has conducted high-quality research to improve student wellbeing and learning through curriculum, assessment and pedagogy. She has completed her MSc. in Health Psychology from Kings and later pursued a PhD in Diabetes, Psychiatry and Psychology research group.

Sebastian Padickaparambil

Dr. Sebastian Padickaparambil currently serves as an Additional Professor in the Department of Clinical Psychology, Manipal College of Health Professions, Manipal Academy of Higher Education. In addition to the teaching responsibilities of M.Phil and MSc. Clinical Psychology, he is a clinical supervisor for M.Phil and MSc. students. He has a PhD in Psychology from the University of Kerala and an M.Phil in Clinical Psychology from Manipal Academy of Higher Education. His areas of interest include positive psychology, sports psychology and clinical psychology.

Nicola Byrom

Dr. Nicola Byrom is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Kings College London. She has conducted extensive work in the field of student mental health, as denoted by her projects ‘Student Minds’ and ‘SMaRteN’. Dr Byrom is passionate about the role of research in shaping policies and practices across the higher education sector. By training, she is an experimental psychologist who has completed her DPhil from the University of Oxford. Dr Byrom's other research interests include peer support, mental health in emerging adulthood and lived experience perspectives.

Selvam Ramachandran

Dr. Selvam Ramachandran is an Associate Professor in the Department of Physiotherapy and Coordinator of Health Professions Education Unit at Manipal College of Health Professions, Manipal Academy of Higher Education. His areas of interest include paediatric neurological rehabilitation, developmental care interventions for at-risk infants and pedagogical innovations. He is passionate about aspects of health professions education and faculty development in academic practice. He is the principal investigator of the collaborative project RAKSHAKA, a joint-seed funding project between Manipal Academy of Higher Education and Kings College London, which focused on faculty development to support student mental health and wellbeing.

References

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Auerbach, Randy P., Philippe Mortier, Ronny Bruffaerts, Jordi Alonso, Corina Benjet, Pim Cuijpers, Koen Demyttenaere, et al. 2018. “WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and Distribution of Mental Disorders.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 127 (7): 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362.

- Brown, Adrienne, Simon M. Rice, Debra J. Rickwood, and Alexandra G. Parker. 2016. “Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators to Accessing and Engaging with Mental Health Care among At-Risk Young People.” Asia-Pacific Psychiatry: Official Journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists 8 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12199.

- Browne, Vivienne, Jonathan Munro, and Jeremy Cass. 2017. “Under the Radar: The Mental Health of Australian University Students.” JANZSSA - Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Student Services Association 25 (2), https://doi.org/10.30688/janzssa.2017.16.

- Campbell, Fiona, Lindsay Blank, Anna Cantrell, Susan Baxter, Christopher Blackmore, Jan Dixon, and Elizabeth Goyder. 2022. “Factors That Influence Mental Health of University and College Students in the UK: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 22 (1): 1778. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13943-x.

- Chaudhary, Amar Prashad, Narayan Sah Sonar, Jamuna Tr, Moumita Banerjee, and Shailesh Yadav. 2021. “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of College Students in India: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Study.” JMIRx Med 2 (3): e28158. https://doi.org/10.2196/28158.

- Cleary, Michelle, Garry Walter, and Debra Jackson. 2011. ““Not Always Smooth Sailing”: Mental Health Issues Associated with the Transition from High School to College.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 32 (4): 250–254. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2010.548906.

- Constantinou, Costas S., Tinna Osk Thrastardottir, Hamreet Kaur Baidwan, Mohlaka Strong Makenete, Alexia Papageorgiou, and Stelios Georgiades. 2022. “Training of Faculty and Staff in Recognising Undergraduate Medical Students’ Psychological Symptoms and Providing Support: A Narrative Literature Review.” Behavioral Sciences 12 (9): 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12090305.

- Cooke, Alison, Debbie Smith, and Andrew Booth. 2012. “Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.” Qualitative Health Research 22 (10): 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938.

- Cvetkovski, Stefan, Nicola J. Reavley, and Anthony F. Jorm. 2012. “The Prevalence and Correlates of Psychological Distress in Australian Tertiary Students Compared to Their Community Peers.” The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 46 (5): 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867411435290.

- Dawson, Deborah A., Bridget F. Grant, Frederick S. Stinson, and Patricia S. Chou. 2006. “Estimating the Effect of Help-Seeking on Achieving Recovery from Alcohol Dependence.” Addiction 101 (6): 824–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01433.x.

- Dittakavi, Snigdha. 2022. “Students Mental Health In India.” BW Defence. 21 March 2022. http://bwhealthcareworld.businessworld.in/article/-Students-Mental-Health-In-India-/21-03-2022-423253.

- Duffy, Anne, Kate E. A. Saunders, Gin S. Malhi, Scott Patten, Andrea Cipriani, Stephen H. McNevin, Ellie MacDonald, and John Geddes. 2019. “Mental Health Care for University Students: A Way Forward?” The Lancet Psychiatry 6 (11): 885–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30275-5.

- Eisenberg, Daniel, Marilyn F. Downs, Ezra Golberstein, and Kara Zivin. 2009. “Stigma and Help Seeking for Mental Health among College Students.” Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR 66 (5): 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709335173.

- Fernandez, A., E. Howse, M. Rubio-Valera, K. Thorncraft, J. Noone, X. Luu, B. Veness, M. Leech, G. Llewellyn, and L. Salvador-Carulla. 2016. “Setting-Based Interventions to Promote Mental Health at the University: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Public Health 61 (7): 797–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0846-4.

- Flynn, Eleanor, Robyn Woodward-Kron, and Wendy Hu. 2016. “Training for Staff Who Support Students.” The Clinical Teacher 13 (1): 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12392.

- Gall, Terry Lynn, David R. Evans, and Satya Bellerose. 2000. “Transition to First-Year University: Patterns of Change in Adjustment across Life Domains and Time.” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 19 (4): 544–567. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.4.544.

- Gulliver, Amelia, Louise Farrer, Kylie Bennett, Kathina Ali, Annika Hellsing, Natasha Katruss, and Kathleen M. Griffiths. 2018. “University Staff Experiences of Students with Mental Health Problems and Their Perceptions of Staff Training Needs.” Journal of Mental Health 27 (3): 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1466042.

- Halladay, Jillian, Rachel Woock, Annie Xu, Marina Boutros Salama, and Catharine Munn. 2022. “Professor Hippo-on-Campus: Developing and Evaluating an Educational Intervention to Build Mental Health Literacy among University Faculty and Staff.” Journal of American College Health, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2115305.

- Hernández-Torrano, Daniel, Laura Ibrayeva, Jason Sparks, Natalya Lim, Alessandra Clementi, Ainur Almukhambetova, Yerden Nurtayev, and Ainur Muratkyzy. 2020. “Mental Health and Well-Being of University Students: A Bibliometric Mapping of the Literature.” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (June), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01226.

- Hodgson, Jessica C., and Roger Bretherton. 2021. “Twelve Tips for Novice Academic Staff Supporting Medical Students in Distress.” Medical Teacher 43 (7): 839–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1831464.

- Hughes, Gareth J., and Nicola C. Byrom. 2019. “Managing Student Mental Health: The Challenges Faced by Academics on Professional Healthcare Courses.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 75 (7): 1539–1548. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13989.

- Jaisoorya, T. S. 2021. “A Case for College Mental Health Services.” The Indian Journal of Medical Research 154 (5): 661–664. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_37_20.

- Kelly, Claire M., F. Anthony, and Annemarie Wright. Jorm. 2007. “Improving Mental Health Literacy as a Strategy to Facilitate Early Intervention for Mental Disorders.” The Medical Journal of Australia 187 (S7): S26–S30. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01332.x.

- Keyes, Corey L. M. 2002. “The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43 (2): 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197.

- Kutcher, Stan, Yifeng Wei, and Connie Coniglio. 2016. “Mental Health Literacy: Past, Present, and Future.” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 61 (3): 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743715616609.

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K. O’Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (1): 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Lipson, Sarah Ketchen, Sasha Zhou, Sara Abelson, Justin Heinze, Matthew Jirsa, Jasmine Morigney, Akilah Patterson, Meghna Singh, and Daniel Eisenberg. 2022. “Trends in College Student Mental Health and Help-Seeking by Race/Ethnicity: Findings from the National Healthy Minds Study, 2013–2021.” Journal of Affective Disorders 306 (June): 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.038.

- Matthews, Timothy, Candice L. Odgers, Andrea Danese, Helen L. Fisher, Joanne B. Newbury, Avshalom Caspi, Terrie E. Moffitt, and Louise Arseneault. 2019. “Loneliness and Neighborhood Characteristics: A Multi-Informant, Nationally Representative Study of Young Adults.” Psychological Science 30 (5): 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619836102.

- Mental Health First Aid USA, National Council for Mental Wellbeing. 2021. “ALGEE: How MHFA Helps You Respond in Crisis and Non-Crisis Situations.” Mental Health First Aid. 15 April 2021. https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/2021/04/algee-how-mhfa-helps-you-respond-in-crisis-and-non-crisis-situations/.

- Methley, Abigail M., Stephen Campbell, Carolyn Chew-Graham, Rosalind McNally, and Sudeh Cheraghi-Sohi. 2014. “PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A Comparison Study of Specificity and Sensitivity in Three Search Tools for Qualitative Systematic Reviews.” BMC Health Services Research 14 (1): 579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0.

- Nielsen, Line, Cecilie Schacht Madsen, Line Nielsen, Malene Kubstrup Nelausen, and Charlotte Bjerre Meilstrup. 2023. “Together at Social Sciences - the ABCs of Mental Health at the University.” Population Medicine 5 (Supplement), https://doi.org/10.18332/popmed/164071.

- Payne, Helen. 2022. “Teaching Staff and Student Perceptions of Staff Support for Student Mental Health: A University Case Study.” Education Sciences 12 (4): 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040237.

- Pollock, Danielle, Andrea C. Tricco, Micah D. J. Peters, Patricia A. Mclnerney, Hanan Khalil, Christina M. Godfrey, Lyndsay A. Alexander, and Zachary Munn. 2022. “Methodological Quality, Guidance, and Tools in Scoping Reviews: A Scoping Review Protocol.” JBI Evidence Synthesis 20 (4): 1098–1105. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00570.

- Priestley, Michael, Emma Broglia, Gareth Hughes, and Leigh Spanner. 2022. “Student Perspectives on Improving Mental Health Support Services at University.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 22 (1), https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12391.

- ‘QS World University Rankings 2023: Top Global Universities’. 2023. Top Universities. 10 June 2024. https://www.topuniversities.com/world-university-rankings/2023.

- Rickwood, Debra, Frank P. Deane, Coralie J. Wilson, and Joseph Ciarrochi. 2005. “Young People’s Help-Seeking for Mental Health Problems.” Australian E-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health 4 (3): 218–251. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.3.218.

- Sharma, Arvind, and Richa Sharma. 2018. “Internet Addiction and Psychological Well-Being among College Students: A Cross-Sectional Study from Central India.” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 7 (1): 147–151. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_189_17.

- Spear, Sara, Yvette Morey, and Tommy Van Steen. 2021. “Academics’ Perceptions and Experiences of Working with Students with Mental Health Problems: Insights from across the UK Higher Education Sector.” Higher Education Research & Development 40 (5): 1117–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1798887.

- Stallman, Helen M. 2010. “Psychological Distress in University Students: A Comparison with General Population Data.” Australian Psychologist 45 (4): 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2010.482109.

- Thomas, Steve, Rachel Jenkins, Tony Burch, Laura Calamos Nasir, Brian Fisher, Gina Giotaki, Shamini Gnani, et al. 2016. “Promoting Mental Health and Preventing Mental Illness in General Practice.” London Journal of Primary Care 8 (1): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17571472.2015.1135659.

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

- Upsher, Rebecca, Anna Nobili, Gareth Hughes, and Nicola Byrom. 2022. “A Systematic Review of Interventions Embedded in Curriculum to Improve University Student Wellbeing.” Educational Research Review 37 (November): 100464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100464.

- Wash, Andrew, Samantha Vogel, Sophie Tabe, Mitchell Crouch, Althea L. Woodruff, and Bryson Duhon. 2021. “Longitudinal Well-Being Measurements in Doctor of Pharmacy Students Following a College-Specific Intervention.” Currents in Pharmacy Teaching & Learning 13 (12): 1668–1678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2021.09.032.

- Yung, A. R., E. Killackey, S. E. Hetrick, A. G. Parker, F. Schultze-Lutter, J. Klosterkoetter, R. Purcell, and P. D. Mcgorry. 2007. “The Prevention of Schizophrenia.” International Review of Psychiatry 19 (6): 633–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701797803.