ABSTRACT

Building on the Salamanca Statement from 1994, the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals 2030 embraces inclusion for children in early childhood education. The European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education in 2015–2017 completed a project on inclusive early childhood education, focusing on structures, processes, and outcomes that ensure a systemic approach to high-quality Inclusive Early Childhood Education (IECE). An ecosystem model of IECE was developed with a self-reflection tool for improving inclusion. This study’s aim was to investigate practitioners’ perspective on the inclusive processes and supportive structures defined in the ecosystem model, to contribute to a deeper understanding of how inclusive practice might be enabled and how barriers for inclusion can be removed. The self-reflection tool was administered in a heterogeneous municipality in Sweden, where inclusive settings are standard. Documentation from approximately 70 teachers on 27 teams was received. The documentation was analysed with qualitative content analysis based on the ecosystem model. The results showed a strong emphasis on group-related processes, whereas data on individual-related processes were scarce. This one-sided focus on the group level might endanger the inclusive processes and outcomes concerning the individual child.

Introduction

The importance of and far-reaching benefits of quality Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) have been acknowledged by the European community and international policymakers during the past few decades (the United Nations [UN]; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]; United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]; World Bank, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]). ECEC is highlighted as a foundation for later school achievement and lifelong learning. Building on the Salamanca Statement from 1994, as well as the Dakar Framework Education for All from 2000, UNESCO and other main international partners organised the World Education Forum 2015 in Incheon, Japan. The Incheon Declaration for Education 2030 sets out a vision for education for the next 15 years based on the UN Sustainability Development Goals ([SDG2030] UN Citation2015), and pre-primary education is highlighted with a special focus on inclusion. The definition of inclusion used in this paper is that adopted by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (Citation2015), namely that ‘The ultimate vision for inclusive education systems is to ensure that all learners of any age are provided with meaningful, high-quality educational opportunities in their local community, alongside their friends and peers’ (1).

Participation in high-quality ECEC has been proven to have long-lasting positive effects on children’s development and learning (Heckman Citation2006, Citation2011; Melhuish et al. Citation2015; Pianta et al. Citation2009; Shonkoff Citation2010; Shonkoff and Phillips Citation2000), and the benefits seem to be greater for children from disadvantaged backgrounds as well as children with disabilities (Frawley Citation2014; Hall et al. Citation2009; Melhuish et al. Citation2015). A central element of ECEC is the inclusion of all children, but there are concerns about the quality of ECEC provisions for all children. Inclusion not only means accessing and being present in ECEC, but also belonging, being engaged, and learning.

Inclusion, participation, and engagement

Participation can be conceptualised as ‘attendance’ and ‘involvement’ (Imms et al. Citation2017). The inclusion of all children requires both attendance and involvement. Involvement is closely related to engagement, defined as being active in everyday activities, and to the interaction between the child and the social and physical environments (Granlund Citation2013). Consequently, factors that are important for inclusion apply not only to the individual child but also to the entire group of children and to the practitioners. These factors also apply to social interaction, to the physical and material environments, and to collaboration with families or caregivers.

A characteristic of an inclusive ECEC environment is that universal measures are taken to provide in-built support to children in need of additional support through well-designed multi-level activities and cooperative work. Specific interventions for an individual child can be integrated into the general activities for all children to provide an inclusive experience. However, they can also be provided through specific activities in smaller groups or for individual children in the group (Sandberg et al. Citation2010).

The ecosystem model of Inclusive Early Childhood Education

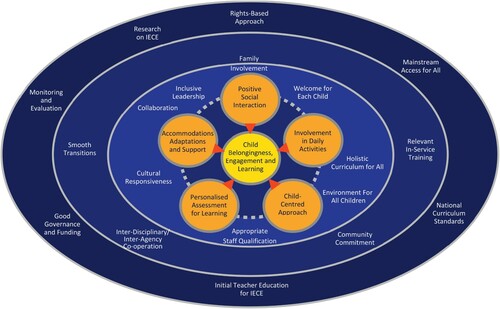

The ecosystem model for Inclusive Early Childhood Education ([IECE] see ) is inspired by the ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006). The model has been developed based on data that emerged from 32 European countries in a project by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education1 (EASNIE Citation2016, Citation2017a). The model is proposed to be used as a framework for planning, improving, monitoring, and evaluating inclusion in IECE. In the ecosystem model (EASNIE Citation2017a), a structure-process-outcome framework (Pianta and Hamre Citation2009) for the understanding of inclusive ECEC is suggested. Structure reflects the national/regional contexts and conditions in the surrounding environments. Process represents the interactions between the child and other children, the practitioners, and the physical environment. Outcome refers to the impact of structures and processes on child engagement and learning. The model’s main focus is on the processes or on the micro level in terms of Bronfenbrenner. This could be regarded as the practitioners’ domain, where inclusion is realised and can be improved in everyday life.

Figure 1. The Ecosystem Model of Inclusive Early Childhood Education. From New Insights and tools – Contributions from a European Study (EASNIE Citation2017a, 37).

Child outcomes, for example, ‘belongingness, engagement, and learning’, are in the centre of the model (cf. ). The five circles around the centre represent primary processes through which children are involved in the everyday life of the setting: positive interaction; involvement in daily activities; a child-centred approach; personalised assessment for learning and accommodations; and adaptations and support. These processes are, in turn, nested within supportive structures in the setting, such as involving parents, welcoming each child, providing a holistic curriculum and an environment for all children, qualified staff, cultural responsiveness, inclusive leadership, and collaboration. The setting’s processes and structures are also supported by structures in the surrounding community, for example, community commitment, in-service training, interdisciplinary/interagency cooperation, support of the family, and support of transitions. In the outer circle, structures at the national/regional levels, policies for ECEC, mainstream access, national curriculum standards, teacher education, governance and funding, and systems for monitoring and evaluation are identified.

Early Childhood Education and Care in Sweden – current structure

ECEC, referred to as preschool in this paper, plays a major role in the everyday lives of young children in Sweden. It is part of the national school system and is regulated by the Education Act and by the national curriculum for preschool (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011, Citation2018). The term ‘inclusion’ is not mentioned in official documents based on the conception that in a preschool for all children, every child is welcome. It is known to be of high quality in international comparisons (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] Citation2017). Every child is legally entitled to attend preschool. At the age of one to five years, 84% of the children attend preschool on a daily basis, and more than 95% of children four to five years old attend preschool (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2018). The provision is publicly subsidised and thus is affordable for parents. There are a few special preschools for children with disabilities (e.g. children with multiple disabilities, autism, and deafness), even though it is strongly recommended that all children attend regular preschool so that they will have maximal opportunities to interact with their peers.

The Education Act states that groups of children should have appropriate compositions and sizes. Recently, it was stated that the group size for children one to three years old should be 9–12 children, and for children three to five years old, it should be 12–18 children depending on the needs of the children, the premises, and the teacher and staff capacity. The average number of children in a preschool group is 15.9, and the average number of children per preschool staff is 5.2 (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2018). The premises and equipment must be ‘fit-for-purpose’; the preschool teachers and staff must have the education or experience necessary to support child development and learning; and premises and equipment must be accessible for all children so that the aim of a preschool for all children preschool can be fulfilled. About 40% of preschool practitioners have an academic degree at the bachelor’s degree level.

Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate the inclusive processes and supportive structures of the ecosystem model of IECE from the perspective of practitioners in Swedish inclusive settings. From the theoretical perspective of ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006), as expressed in the model, the findings are intended to contribute to a deeper understanding of how IECE practice might be enabled and how barriers for inclusion can be removed. A further issue is to identify areas where development is potentially needed, as well as possibilities for improvement to fulfil the goal of providing a preschool for all children.

Research questions:

How are inclusive processes and supportive internal structures in the ecosystem model of IECE manifested in everyday practice from the perspective of practitioners in Swedish inclusive settings?

What enabling processes and barriers for inclusion are identified from the perspective of practitioners in Swedish inclusive settings?

How can the findings regarding inclusion be understood in relation to supportive structures within the community and at the Swedish national level?

Method

The self-reflection tool

The previously mentioned ecosystem model highlighted the need for an instrument to look carefully at the social, learning, and material/physical environments in the IECE setting. Initially, an observation instrument based on the model was developed. During the implementation of the IECE project, the need for a tool for self-reflection on inclusiveness was realised, and the observation instrument was developed into such a tool. The self-reflection tool (EASNIE Citation2017b) was used for data collection in this study. The aim of the tool is to capture the social, learning, and material/physical environments in the IECE setting and to provide an overall picture of inclusiveness. It consists of the following eight dimensions:

Overall welcoming climate

Inclusive social environment

Child-friendly physical environment

Materials for all children

Opportunities for communication

Child-centred learning environment

Inclusive teaching environment

Family-friendly environment

Each dimension in the tool consists of a set of questions (see ). These questions are designed to provide a picture of the inclusiveness of the preschool setting. It is intended to be used by practitioners to reflect on and work with the improvement of inclusion. The tool can also aid in a reflective process by providing practitioners with a set of questions that focus on the provision of inclusive social, learning, and physical environments. The self-reflection tool is available in 25 languages at EASNIE’s website, free of charge. For the validation process of the tool, see EASNIE (Citation2017b). Additional studies based on the self-reflection tool have not been conducted according to our searches in various databases.

Procedure

Data were collected in a municipality in Greater Stockholm with about 90,000 inhabitants. It is one of Sweden’s most culturally heterogeneous areas; 58% of the population are either born in another country or have parents who were both born in another country. More than 100 languages are spoken in the municipality. There are 16.8 children per group (Swedish Teacher Union Citation2018). The average group size in Sweden is 15.9 (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2018). In addition, the proportion of teachers with a university degree is lower than in the majority of Swedish preschools (Swedish Teacher Union Citation2018). All preschools in Sweden cater for children aged one to five years old. Instructions and a link with the self-reflection tool were sent via the local administration to head teachers in the municipality’s 47 public preschools. The teachers also received a letter informing them of the purpose of the study, as well as a request for assistance in forwarding the tool to be filled in by the preschool teachers (i.e. teachers with a university degree). The teachers were asked to work in groups of a maximum of four people and to document their discussions on the tool’s electronic form. They were informed that they would be anonymous and that participation was voluntary.

Participants

The electronic form of the tool was filled in and returned from 24 preschools. A total of 27 groups, with two to four teachers per group, documented their work with the tool. Information on how many participated in filling out the form was missing on some forms, but approximately 70 preschool teachers participated. Background questions on the profession and on the number of years in the profession were answered by 65 and 62 teachers, respectively. Out of 65 teachers, 61 reported that they had a preschool teacher degree. The remaining had degrees for school teachers or social workers, for example. The median for the number of years in the profession was 15, and 58% of the teachers reported that they had 10 years or more of experience. A total of 28% reported 20 years or more of experience.

Analysis

Data were analysed using content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs Citation2008). In the preparation phase, data were organised for coding by collecting all answers in one document and assigning each form an identification number. A deductive approach was applied, and the categories were based on the processes and supportive structures defined in the ecosystem model ().

Initially, the first and second authors read through the entire data set, then used data from nine forms to specify the definitions of the categories. Based on the unconstrained matrix, the same authors independently coded data from the same two forms to seek agreement in the coding procedure. Minor disagreements in the coding procedure were discussed to develop a categorisation matrix. For example, the teachers’ description of dividing the children into smaller groups could be interpreted in different ways and consequently fit into different categories. The reason for the smaller groups could be partly an organisational issue for involving all children in daily activities, and it could also be an adaptation based on the needs of an individual child. After the final version of the categorisation matrix was developed and clarified (see ), a joint coding showed highly consistent results. Then, the coders shared the coding of the remaining data between them, and each dimension was coded by one coder. When all of the data were coded, they were checked for consensus.

Table 1. Categorisation matrix on inclusive processes and supportive structures.

The coded data within each category were reread and inductively grouped based on the content. The two coders grouped the data individually. Then, the grouped data were discussed and revised so that the general meaning of the content was abstracted for each category. In the analysis of the abstracted data, two underlying themes were identified. Finally, illustrative quotes for each category were identified.

Results

The content analysis was based on the ecosystem model’s processes and supportive structures, which served as categories for coding data. The results reflected the ecosystem model’s micro system as manifested in the teachers’ statements. The vast majority of the data were coded into the process categories. The presentation of the process categories is therefore are more extensively elaborated than the presentation of the supportive structure categories is.

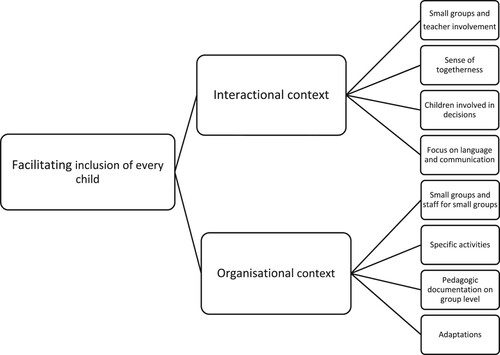

Processes

Two different contexts of inclusive processes were identified as underlying themes in several of the process categories. These themes were formulated as ‘the organisational context’ and ‘the interactional context’. The organisational context concerns how everyday practice is organised to promote inclusion. The interactional context refers to the promotion of inclusion in the actual interaction with the children.

Positive social interaction

In the positive social interaction category, both underlying themes – the organisational and the interactional context – were present. The teachers focused on how positive social interaction is promoted by the way in which the entire group of children is organised into smaller groups – for example, by combinations of children – and how they plan activities to be implemented in smaller groups.

The interactional context contains teacher’s efforts to improve the social climate and to promote children’s social skills. For example, children are encouraged to invite one another to engage in interactive play and are taught conflict management strategies. Circle-time activities are highlighted as opportunities for interactive activities, such as singing and storytelling. Promoting positive social interaction was reported by the teachers as requiring active involvement, for example, supporting social interaction, acting like models for the children, or actively participating in the children’s activities and games. In addition, strengthening the sense of ‘togetherness’ in the group was stressed as important for positive social interaction.

We support and participate in activities. Interaction and play are also facilitated when we divide the children into smaller groups and in different group constellations.

The youngest need more help and with increased age the older can to a greater extent solve their conflicts themselves. We educators are present.

Involvement in daily activities

The category of involvement in daily activities has resemblances with the category of positive social interaction. Both of the underlying themes were present. As in the former category, the organisational context largely concerned organising the children into smaller groups. In contrast to the category of positive social interaction, in this category, the goal of organising children into smaller groups is to enable all to be involved in daily activities. The teachers stressed the importance of language and communication for involvement. Therefore, involvement is regarded as being linked to the provision of environments that offer prerequisites for communication and language development for all children. Another central aspect of the involvement of all children is how transitions between activities are planned, organised, and performed. Other organisational strategies include repeating activities to ensure that every child has the opportunity to participate, formulating clear rules, and using activity boards.

As in the category of positive social interaction, the need for teacher involvement was found to be a prominent aspect of what was defined as the interactional context of the category of involvement in daily activities, for example, being present to spot signs of children who are in the periphery, or paying attention to children who are not engaged in an activity. The interactional context of involvement in daily activities was also manifested in the teachers’ descriptions of engaging children who tend to not be involved, by actively taking part in children’s play.

In the interactional context, the importance of language was stressed as being fundamental for engaging in communication with others. Teachers in the organisational context create prerequisites for language development and communication. However, in the interactional context, they promote these abilities in their interactions with the children. For example, they teach children how to express their needs, and they help them to put their actions into words. Similarly, transitions were characterised by teachers as interacting with children during transitions.

Furthermore, strengthening the group´s sense of togetherness was found to be an important aspect of the teachers’ interactional efforts to achieve the involvement of all. This is possible, for example, making all children feel secure in the group, using inclusive language (‘we’), and supporting a sense of togetherness during circle time.

This category also includes statements on barriers to involvement in daily activities, for example, factors related to children with special needs or children who tend to be involved in conflicts with other children. A lack of language was mentioned as a major obstacle for involvement.

The children are offered activities together with the whole group, where we use, among other things activity boards, signs as support, clear rules and routines where all children are or will be involved according to interest and needs.

We offer all children to participate in the way they want to participate. You can participate in different ways, get different roles. We organise various activities to suit everyone.

Child-centred approach

This category mainly characterises children’s participation in planning daily activities. Compared with previous categories, data are limited and rather shallow. However, the category consists of both the organisational context and the interactional context. In the organisational context, planning and organising are guided by the needs and interests of the children, for example, in adapting teaching, materials, and the environment. In the interactional context, statements describe how children get involved in decision processes – for example, in councils, voting on activities, and listening to and respecting children’s thoughts. The level of language development is expressed as limiting the degree to which children’s voices can be taken into consideration. The goals of the national curriculum are also expressed as raising a limit for the extent of the design of activities in line with children’s interests.

In project planning, children are given the opportunity to participate through, for example, reflection with the children.

Trying to answer all children’s questions and meet their opinions. What we cannot answer, we research on together with the children. We listen to their opinions and take them to us and use them to the extent possible.

Personalised assessment for learning

The category of personalised assessment for learning, and the following category of accommodation, adaptation, support differ distinctively from the other process categories. Compared with the three other categories, the data are far more limited. Only the underlying theme of the organisational context was identified.

The category of personalised assessment for learning lacks statements reflecting the actual assessment of individual children. Instead, the data showed that teachers organise observations and evaluations at a group level. The data showed how documentation (e.g. photos, films, notes) is performed on a general level in the daily activities. The documentation is used as the basis for discussing, reflecting, and evaluating with colleagues and parents, as well as with other professionals (e.g. special educators, speech therapists). A few teachers mentioned applying systematic evaluation using developmental criteria and templates but not in terms of enabling the inclusion of specific children.

Different forms of analyses for example in projects and language analyses, and for example development talks [with parents].

Through daily observations, documentation, reflections in the work group, notes and development talks. If necessary, extra meetings can also be made with parents and special educators.

Accommodation, adaptation, support

The category of accommodation, adaptation, support also reflects only the underlying theme of the organisational context. Again, dividing the whole group into smaller groups is central, and so is planning activities where teachers can provide sufficient support to all children. An example of providing support is to organise staff so that the same teacher spends the entire day with children who benefit from his or her support. In the interactional context, the use of sign language and pictures is mentioned. There are limited reports of adaptations in relation to the needs of specific children. Some teachers also express insufficient resources as an obstacle for being able to provide all children with the support they need.

There is support to get from the municipality, but it can take time to get help. There may be children who require extra support but do not meet the criteria for getting extra support from the municipality.

Working in smaller groups facilitates. Children have to wait sometimes but that does not mean that they do not get help. Teacher assistants are rarely found.

Supportive structures

The supportive structure categories are, as could be expected, less dynamic than the process categories are and thereby are more descriptive of their characters. Statements in these categories could not clearly be interpreted in the organisational and interactional contexts.

Family involvement

The category of family involvement is characterised by formalising a good relationship and communication with the caregivers. This is achieved by informing the caregivers about daily activities and having a continuous dialogue with them. The teachers stressed the importance of greeting the caregivers everyday. The period when the child starts preschool was expressed as particularly crucial for making the caregivers feel secure and involved in the preschool.

We build bridges with parents, “my parent trusts the preschool teacher, then I can trust her”.

All parents are welcome. They are met with a positive attitude when leaving and picking up their children. We treat them with respect and joy.

Welcoming each child

The welcome for each child statements focus on establishing structures that enable all children to feel seen. This was confirmed as being crucial for creating a secure atmosphere. The teachers expressed that this is sometimes at risk due to high workloads. They also mentioned the need to actively prevent aggressive behaviour to make all children feel secure.

We want to convey a welcoming atmosphere by seeing all the children during the day and being present. Welcome is one of our core values, therefore it is something we constantly pay attention to and think about.

To meet teachers who enjoy their work and have a reasonable workload makes the welcome and the pleasing atmosphere possible.

Holistic curriculum

The category of holistic curriculum for all is a category that basically lacks data, and therefore, no qutations are presented. The teachers seldom mentioned the curriculum. Some statements bring up projects as a part of the curriculum but not in the sense of a holistic curriculum.

Enviroment for all children

In the category of enviroment for all children, creating an environment that is welcoming and safe was emphasised. Such an environment was described as encouraging play, development, and learning, and it was emphasised that children should know what is expected of them yet have opportunities to make choices. The teachers described the environment as being accessible to children with disabilities and consequently varying according to the needs of the group.

There is an awareness and constant reflection on which materials make it easier for the children to learn through play and exploration.

We have materials that stimulate the children to dialogue and joint exploration. We have specified ares for language, mathematics and science where the children can meet in dialogue.

Appropriate staff qualifiaction

The category of appropriate staff qualification is characterised by statements regarding competence. Collaboration was mentioned as enabling the use of different competences and as complementing one another. The teachers said they believed that when competence is lacking, this might limit the promotion of social interaction, and materials might not be used to their full potential. Moreover, there are reports of receiving, not receiving, or having to wait too long for resourses (e.g. special educators, speech therapists).

We strive to make every teacher to develop their potential, we are all good at different things and we try to take advantage of different abilities.

We use special educational support in the municipality. Professionals from the habilitation and other services can visit us at the preschool and to some extent provide guidance on an individual child.

Cultural responsivness

The category of cultural responsiveness contains statements on working with acceptance for equality and seeing differences as assets. This means paying attention to children’s various languages and cultures, for example, by celebrating feasts as well as introducing languages, letters, food, and music from different cultures.

Diversity and children’s individual strengths are welcomed and seen as an asset and not an obstacle, so that all children should feel accepted.

We stress each other’s differences as assets. We learn and inspire each other. Everyone is not alike, but we lift the difference as an asset.

Collaboration

In the category of collaboration, data are limited. To some extent, collaboration within and between preschools was described. Collaboration with the surrounding society was rarely described, and some teachers mentioned that they want to extend cultural contributions.

We are sitated in a multi-faceted local area, that is exciting and easily accessible with forests, libraries, parks, play parks, water towers, bus stops and larger bus stations.

Good cooperation between the teachers, we have a transparent workplace. It creates security between both children and educators.

Inclusive leadership

In the category of inclusive leadership, the majority of the teachers interpreted the questions as if they themselves can participate and influence decisions in preschool activities. The few teachers who reflected on how the preschool’s leadership can contribute to the inclusion of all children systematically referred to the completion of quality work and the use of different types of educational forums.

The work is delegated and everyone is involved in planning and different types of decisions.

The management invites pedagogues to discuss and reflect in different contexts and in different constellations in order to create a shared attitude on how we relate to children and caregivers and to create collegial learning. We think this will generate an inclusive culture where everyone can participate.

In sum, the preschool teachers talked about inclusion from a general perspective, highlighting their work with a group of children (see ). Process factors that seem to be of most importance are positive social interaction, the planning of daily activities for all children, respect for children’s voices, the high-quality documentation of daily activities, and adaptations of the materials. The needs of the individual child were scarcely mentioned in the data.

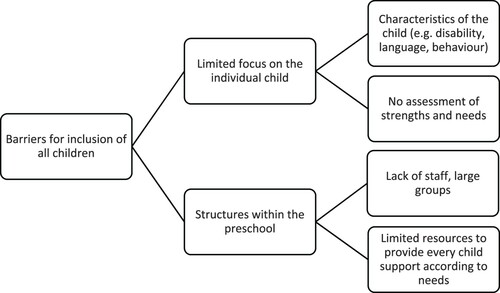

Barriers for inclusion tend to be factors in the everyday preschool environment (see ), such as the number of staff, the large group size, and limited resources for individual child support. Factors related to a limited focus on individual children were mentioned as barriers for inclusion.

Discussion

Inclusion demands both ‘attendance’ at and ‘involvement’ in preschool (Granlund Citation2013). Attendance is closely related to the distal structures in the ecosystem model (EASNI Citation2017a) and to the corresponding exo- and macrosystem in the ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006). With a national policy focusing on a preschool for all children, attendance at Swedish preschool is almost universal. Most children attend preschool from an early age, and preschools are obligated to welcome all children. Attending preschool sets the scene for engagement, i.e. being active in the everyday interactions between the child and the social and physical environment (Granlund Citation2013) which is necessary for inclusion.

As illustrated in , organising activities for children in small groups is identified as facilitating the inclusion of all children. Barriers to the inclusion of all children were identified in structures within the preschool as well as factors related to the individual child. It is notable that almost no strategies or factors were mentioned that are related to how support can be provided to children who are excluded or at risk for being excluded, for example, children who attend preschool but are not engaged in the school’s everyday activities (see ).

Particularly in statements coded in the category of accommodation, adaptation and support, it appears that the teachers were aware of the risk that all children might not get the support they need. A specific question in the self-reflection tool concerns all children’s access to individual support for learning when needed. On this question, the majority of the preschool teachers reported ‘no’. Among those who reported that all children do not have access to individual support, several referred to factors in the ecosystem model’s (EASNIE Citation2017a) outer circles, and they most commonly referred to the child–teacher ratio. To understand how the child–teacher ratio affects the capacity for sufficient individual support, one has to take the framework for Swedish ECEC into consideration. All individual preschools must be accessible for all children aged one to five years, and opening hours should adjust to the parents’ working hours. Thus, all Swedish preschools must be available for all children one to five years of age for up to 50 h per week. For settings organised in this way, the child–teacher ratio is naturally of more concern than it is for less inclusive settings with older children and more limited hours.

The preschools in the municipality where this study was conducted have larger groups and higher child–teacher ratios compared with the Swedish average (Swedish Teacher Union Citation2018). In line with a previous Swedish study (Pramling-Samuelsson, Williams, and Sheridan Citation2015), the strong focus on organising the group might be a consequence of the larger child groups. Furthermore, the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (Citation2018) concluded that preschools with higher child–teacher ratios have more developmental needs compared with those with lower teacher–child ratios. The group sizes are decided on the community level, but the sizes also depend on funding at a national level. Hence, the child–teacher ratio could be regarded as a factor in the model’s two outer circles (community and national level). This might partly explain the strong focus on the group as well as the reports of not being able to give all children the support they need.

The preschool teachers in this study clearly expressed that the group is the unit for inclusion. Belongingness, engagement, and learning for the individual child is, however, seldom brought up. From a theoretical perspective, both the ecosystem model and the ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006) are centred on the individual child, yet in the preschool teacher’s reflections on inclusion, the individual child is virtually invisible. Even though statements of inclusive processes were identified both in the organisational context and in the interactional context, there were virtually no statements concerning how the needs of individual children are assessed and catered to. From the theoretical perspective of this study, the one-sided focus on the group level might endanger the processes and outcomes concerning the individual child.

Limitations

The teachers’ reflections may have been influenced by social desirability, which may be related to Sweden’s strong policies for and culture of welfare and equality. Teachers are expected to welcome all children. In addition, the teachers could have felt that they were not totally anonymous, as the first contact was taken with the head teachers, and the forms were filled out group wise. On the other hand, the teachers described how children are involved in the daily activities. They also described a lack of individual assessments and accommodations, which indicates genuine reflections from the teachers.

Moreover, the self-reflection tool has several questions that can be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Consequently, these questions were responded to with short answers without further descriptions. With more open questions and richer descriptions, a more nuanced picture could have probably emerged of the teachers’ perceptions. In general, the format of the self-reflection tool, with its predesigned questions, affected the results. Individual interviews, focus groups, or observations might generate insights on other aspects of inclusion in preschool.

Conclusion

It could be concluded that to understand how the Salamanca Statement is translated into everyday practice, it is fruitful to investigate the practitioner perspective. Even if the conclusions that can be drawn from this study are limited, they are in line with a recent report from the Swedish School Inspectorate (Citation2018). In this report, it is concluded that Swedish preschools have high ambitions of attending to all children’s needs, but systematic methods for documenting, analysing, following up on, and evaluating the needs of individual children tend to be missing.

The guiding principle for the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO Citation1994) is that ‘all children, regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, linguistic or other conditions, shall attend the neighbourhood school in an inclusive setting’. The fundamental idea is that all children should belong, engage, and learn and that inclusive settings do attend to the diverse needs of all children and provide support that matches these needs. This study raises concerns regarding the provision of support to individual children in the preschool for all children. The teachers’ reports showed that the group and the environment are the focus of attention.

To conclude, in the Swedish preschool for all children, attendance is high. It is questionable, though, whether the goals of inclusion, belongingness, engagement, and learning are, in fact, fully realised for all children. It is ensured that all children are provided with educational opportunities in their local communities, alongside their friends and peers. However, whether every child is engaged and included in the everyday activities is not evident. Our results call for further practice-oriented studies on inclusion in Swedish preschools.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (21.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participating municipality and the preschools who generously contributed to this report. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Agency for Special Needs Education and Schools, SPSM. This work has developed from a project implemented and publications produced by the European Agency for 27Special Needs and Inclusive Education: https://www.european-agency.org/projects/iece.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hanna Ginner Hau

Hanna Ginner Hau, is currently a senior lecturer in Special Education at Stockholm University. She is a licensed psychologist and has a PhD in Psychology. She has been involved in several research projects conducted in collaboration with practice in health care and social services as well as in education. Her research interests concern children at risk, both in early childhood as well as in adolescence.

Heidi Selenius

Heidi Selenius, is currently a senior lecturer in Special Education at Stockholm University. She has a background as a special education teacher and has a PhD in Psychology. Her research interests include special needs among children and youngsters. Her main focus is on learning disabilities and aggressive behaviour.

Eva Björck Åkesson

Eva Björck-Åkesson is a professor of Special Education. Her research is focused on special education, early intervention and ECEC. Special interests are inclusion in early childhood education and participation of young children in need of support in preschool.

References

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments By Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. A. Morris. 2006. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” In Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol.1: Theoretical Models of Human Development (6th ed.), edited by W. Damon, and R. M. Lerner, 793–828. New York: Wiley.

- Elo, S., and H. Kyngäs. 2008. “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62 (1): 107–115. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE). 2015. Agency Position on Inclusive Education on Systems. Odense, Denmark: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE). 2016. Inclusive Early Childhood Education: An Analysis of 32 European Examples. Odense, Denmark: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

- European Agency for Special Needs Inclusive Education (EASNIE). 2017a. Inclusive Early Childhood Education: New Insights and Tools – Contributions from a European Study. Odense, Denmark: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE). 2017b. Inclusive Early Childhood Education Environment Self-Reflection Tool. Odense, Denmark: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

- Frawley, D. 2014. “Combating Educational Disadvantage Through Early Years and Primary School Investment.” Irish Educational Studies 33 (2): 155–171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2014.920608

- Granlund, M. 2013. “Participation – Challenges in Conceptualization, Measurement and Intervention.” Child: Care, Health and Development 39 (4): 470–473. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12080

- Hall, J., K. Sylva, E. Melhuish, P. Sammons, I. Siraj-Blatchford, and B. Taggart. 2009. “The Role of Pre-School Quality in Promoting Resilience in the Cognitive Development of Young Children.” Oxford Review of Education 35 (3): 331–352. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980902934613

- Heckman, J. J. 2006. “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children.” Science 312 (5782): 1900–1902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128898

- Heckman, J. J. 2011. “The Economics of Inequality: The Value of Early Childhood Education.” American Educator 35 (1): 31–35.

- Imms, D., M. Granlund, P. H. Wilson, and B. Steenbergen. 2017. “Participation, Both As a Means and an End: A Conceptual Analysis of Processes and Outcomes in Childhood Disability.” Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 59 (1): 16–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13237

- Melhuish, E., K. Ereky-Stevens, K. Petrogiannis, A. Aricescu, E. Penderi, K. Rentzou, and P. P. M. Leseman. 2015. A Review of Research on the Effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) on Child Development. WP4.1 Curriculum and Quality Analysis Impact Review (CARE). Unpublished document.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2017. Starting Strong 2017 – Key OECD Indicators on Early Childhood Education and Care. Accessed February 18, 2019. https://www.oecd.org/education/starting-strong-2017-9789264276116-en.htm.

- Pianta, R., W. Barnett, M. Burchinal, and K. Thornburg. 2009. “The Effects of Preschool Education: What We Know, How Public Policy Is Or Is Not Aligned with the Evidence Base, and What We Need to Know.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 10 (2): 49–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100610381908

- Pianta, R. C., and B. K. Hamre. 2009. “Conceptualization, Measurement, and Improvement of Classroom Processes: Standardized Observation Can Leverage Capacity.” Educational Researcher 38 (2): 109–119. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09332374

- Pramling-Samuelsson, I., P. Williams, and S. Sheridan. 2015. “Stora Barngrupper i Förskolan Relaterat Till Läroplanens Intentioner [Large Groups of Children in Preschool in Relation to the Intentions of the National Curriculum].” Nordic Early Childhood Education Research Journal 9 (7): 1–14.

- Sandberg, A., A. Lillvist, L. Eriksson, E. Björck-Åkesson, and M. Granlund. 2010. “‘Special Support’ in Preschools in Sweden: Preschool Staff’s Definition of the Construct.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 57 (1): 43–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120903537830

- Shonkoff, J. 2010. “Building a New Biodevelopmental Framework to Guide the Future of Early Childhood Policy.” Child Development 81 (1): 357–367. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01399.x

- Shonkoff, J. P., and D. A. Phillips. 2000. From Neurons to Neighbourhood. The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2011. Läroplan för Förskolan: Lpfö 98, Rev 2010 [National Curriculum for Preschool]. Skolverket: Stockholm. Accessed February 23, 2019. https://www.skolverket.se.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2018. Beskrivande data 2017-Förskola, skolaoch vuxenutbildning [Descriptive data 2017 – Preschool, school and adult education]. Accessed Feb 2019. www.skolverket.se.

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate. 2018. Förskolans Kvalitet Och Måluppfyllelse – Ett Treårigt Regeringsuppdrag att Granska Förskolan [The Preschools’ Quality and Goal Completion]. Accessed February 2019. www.skolinspektionen.se.

- Swedish Teacher Union. 2018. Så Här är Förskollärartätheten i Din Kommun [Preschool Teacher-Child Ratio in Your Municipality]. Accessed February 23, 2019. www.lararforbundet.se.

- United Nations. 2015. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Accessed February 23, 2019. http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework of Action on Special Needs Education. Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca, Spain, June 7–10.

Appendix

Questions and dimensions for the self-reflection tool (EASNIE Citation2017b).

The tool in its entirety is freely available at www.european-agency.org.

1. Overall welcoming atmosphere

2. Inclusive social environment

3. Child-centred approach

4. Child-friendly physical environment

5. Materials for all children

6. Opportunities for communication for all

7. Inclusive teaching and learning environment

8. Family-friendly environment