ABSTRACT

Many pupils with disabilities receive schooling in segregated contexts, such as special classes or special schools. Furthermore, the percentage of pupils educated in segregated settings has increased in many European countries. Studies suggest that there is high commitment to the general ideology of inclusive education among teachers in ‘regular’ education in many countries. This survey study investigates the views of teachers in segregated types of school about education. A questionnaire was sent out, in 2016, to all Swedish teachers (N = 2871, response rate 57.7%) working full time in special classes for pupils with intellectual disability (ID). On a general level results show that there is a strong commitment to preserving a segregated school setting for pupils with ID, a limited desire to cooperate with colleagues from ‘regular schools’ and a view that schooling and teaching are not quite compatible with the idea of inclusive education. The results highlight the importance of investigating processes of resistance within segregated schools to the development of inclusive schools and education systems. We argue that, while research and debate about inclusive education are important, both are insufficient without analyses of existing types of segregated schooling.

Introduction

For several decades now, inclusive education has been a goal supported by many countries and their school systems. This goal does, however seem to be hard to achieve (e.g. Arnesen, Mietola, and Lahelma Citation2007; Ferguson Citation2008; Nilsen Citation2010; Norwich Citation2008; Sturm Citation2018). Studies suggest that there is high commitment to the general ideology of inclusive education among teachers in ‘regular’ education (e.g. Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006; Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002; Croll and Moses Citation2000). Less attention has been paid to the views on education of teachers teaching in segregated contexts. Like Slee (Citation2011), we argue that ‘the point of research on inclusive education should be to build robust and comprehensive analyses of exclusion in order that we might challenge social and cultural relations as mediated through education’ (83).

In several countries, on organisational national, or local levels, schooling for many children with disabilities is provided in more or less segregated contexts: for example, in special schools or in special groups or special classes in regular schools. According to the latest statistical report from the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE Citation2018) an average of 1.62% of pupils were educated in separate educational settings (special classes or special schools) during the 2014–2015 school year. The latest report on education from the OECD even states that equity in education has decreased in many countries on a general level (OECD Citation2018), i.e. pupils’ outcomes are related to their background or other economicand social factors over which the pupils have no control. Sweden has gone from having one of the most equitable and inclusive education systems (OECD Citation2011), to ranking merely average in this respect. Statistics from the European Commission (Citation2005) and EASNIE (Citation2018) show that the percentage of pupils with an official special educational needs (SEN) decision who are educated in separate educational settings increased in several European countries between the 2002–2003 and 2014–2015 school years. Exclusion seems, as Slee (Citation2011) puts it to be ‘a general though, not always acknowledged, social condition’ (15).

Educators in many countries have also experienced changes within the domain of educational ideologies as expressed in education policies – regarding ideas about the objectives of school systems, schools, and classrooms – that emphasise ideas other than inclusion. For example, there is an increased focus on goal achievement, or as Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson (Citation2006) formulate it ‘to drive up standards of attainment’ (296) and a tendency to regard the objectives of education as ‘private goods’ rather than ‘public goods’ (Bunar and Sernhede Citation2013; Labaree Citation2010). Many advocates of inclusion regard this as quite contrary to the idea of inclusion, which is more linked to an egalitarian view of the purpose and primary goal of schooling; they emphasise that the main purpose of education should be to foster a more equitable society through equity and equality in education (e.g. Florian and Kershner Citation2009; Kluth, Straut, and Biklen Citation2003; Naraian Citation2011; c.f. Labaree Citation1997). Thus, one could argue that the described developments are inconsistent with the efforts toward inclusion formulated in international documents such as the Salamanca Declaration (UNESCO Citation1994) and Article 24 on education in the UN Convention on Rights for Persons with Disabilities, (UN Citation2006).

Arguably, national and international education policies and other steering documents, such as education legislation and national curricula, express value frames that make certain processes more likely to occur than others (cf. Lundgren Citation1999), affecting the interpretation and enactment of inclusive education at different levels of the education system. However, such steering documents are often characterised by a multitude of sometimes unrelated goals and purposes that are at times contradictory. Many formulations are also quite abstract and not easy to put into everyday school practice. One might say that they are characterised by an ideological openness bordering on ideological fuzziness. This ideological openness leaves considerable room for interpretation, by teachers and other actors working with designing curricula and everyday school practice (cf. Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2012; Clark, Dyson, and Millward Citation1998; Florian and Kershner Citation2009; Labaree Citation1997). To better understand processes of exclusion and inclusion it is therefore not enough to study educational policy documents and other steering documents. One also needs knowledge about the views on education, teaching, and learning held by professionals who work in segregated contexts as well as in regular school.

As pointed out by several researchers fostering inclusive education further requires models of collaboration where new relationships between segregated school contexts and ‘regular’ school are developed (e.g. Florian Citation2008; Rix et al. Citation2013). Cooperation between different professionals has been identified as a key factor for developing inclusive processes (e.g. van Garderen, Stormont, and Goel Citation2012). In an international review Rix et al. (Citation2013) identify collaboration and cooperation between professionals as one of the challenges of inclusive education. To our knowledge, however, little attention has been paid to how teachers teaching pupils with official SEN decisions in segregated settings perceive collaboration.

This paper proposes a complementary understanding of the prerequisites for inclusive processes by investigating teachers of pupils with intellectual disability (ID) in special classes in Sweden with respect to the following: (1) their beliefs about what characterises teaching in special classes for pupils with ID (SCIDs) and teaching in ‘regular schools’; (2) their conceptual frameworks concerning learning and teaching pupils with ID, and (3) their actual and desired collaboration with their teaching colleagues working in the SCID sertting and their teaching colleagues in the ‘regular’ school. The education of pupils with ID in Sweden is a particularly interesting case for studying processes of inclusion because, even though Sweden is renowned for its aspiration to offer a ‘school for all’, it has a long tradition of educating this group of pupils in segregated classes and schools, while it is also one of the few countries where the education of this particular group of pupils is singled out and has separate national curricula, course syllabi and timetables – that is, where education is segregated at a national organisational level. The results are unique insofar as they are derived from a large data set comprising all class teachers of pupils with ID in SCIDs in Sweden.

Education for pupils with intellectual disability

Historically, the focus of education for pupils with ID has been formulated differently than that for pupils without ID. The first educational initiatives for pupils with ID were inspired by a medical paradigm and focused on physical training, everyday hygiene, and perception training, such as distinguishing colours, forms, and sounds (Areschoug Citation2000; Røren Citation2007; Wehmeyer and Smith Citation2017). Further, as public education initiatives started to emerge, pupils with ID were to acquire the minimum theoretical and practical knowledge needed to contribute to society. Although the curriculum did contain traditional subjects such as mathematics, science and language arts, the focus was primarily on implementing knowledge and skills in everyday life (Bouck Citation2004).

Curricular content for pupils with ID is considered in research overviews of the periods 1976–1995 (Nietupski et al. Citation1997) and 1996–2010 (Shurr and Bouck Citation2013). These overviews show that research has primarily focused on functional life skills. However, lately there has been a shift towards a focus on cognitive academic skills (Moljord Citation2017). Moljord discusses this shift as a move towards mainstream schooling and suggests that it could be understood as an ‘influence of the ideology of inclusion’ (10). Research on teaching pupils with ID has focused less on the reasons for teaching certain content, although cognitive academic skills and functional life skills have been discussed in relation to the everyday usefulness of such skills for pupils with ID (Moljord Citation2017; Shurr and Bouck Citation2013). When it comes to the Swedish educational context, compulsory schooling for pupils with ID has been criticised for focusing on care and not providing the pupils with enough content knowledge (Berthén Citation2007; Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE] Citation1996, Citation1999, Citation2001; Swedish Schools Inspectorate [SSI] Citation2010).

Education of pupils with ID in the Swedish school system

There are four school types within the Swedish compulsory school system: the comprehensive school (‘regular school’), SCID, the Sami school, and special school (659 pupils or 0.06% of pupils in compulsory school). In upper secondary school there are two types of schools: upper secondary ‘regular’ and upper secondary SCID. In this paper SCID refers to both compulsory SCID and upper secondary SCID, unless otherwise noted.

Schooling of pupils with ID is primarily regulated in the Education Act (Public Law 800 Citation2010) and national curricula for the SCID compulsory school (Government Office Citation2011) and SCID upper secondary school (Government Office Citation2013). The Education Act stipulates that children who are not expected to meet the knowledge objectives of the comprehensive school or upper secondary school because of an ID must receive their schooling in compulsory or upper secondary schools for pupils with ID (Chapter 7 §5; Chapter 18 §4). The two national curricula for SCID include course syllabi and timetables that differ from those of regular comprehensive and upper secondary schools. Both compulsory and upper secondary SCIDs have two main orientations, with their own course syllabi and timetables: one for pupils with moderate to mild ID and one for pupils with more severe ID. During the 2018–2019 school year, 1.2% (n = 17,132) of the pupils aged 7–19 attended SCID (Official Statistics of Sweden [OSS] Citation2019). Most pupils in SCID receive their schooling in special classes in ‘ordinary’ schools. A smaller share, around 12% of pupils in compulsory SCID, spend half or more of their time in school in regular classes, that is in mainstream settings. In Sweden, these pupils are referred to as ‘integrated’.

Theoretical foundations

We argue that processes of inclusion (or exclusion) develop in relation to different value frames concerning ideas about the purposes of schooling and methods of how to achieve those purposes – value frames that can be more or less compatible with the idea of inclusive education. The position of this paper regarding inclusive education is that we understand inclusion as creation of communities characterised by equity, care justice, honouring of subjugated knowledge and valuing diversity. To quote Narian (Citation2011):

an important construct with which inclusive education has come to be strongly affiliated is the notion of community. The successful participation of students with disabilities in a general education classroom is premised on the creation of classroom communities that can nurture the qualities of equity and care (Erwin and Guintini Citation2000; Kluth Citation2003; Meyer et al. Citation1998; Sapon-Shevin Citation1999; Villa and Thousand Citation2000). Simultaneously, the task of making classrooms hospitable to all learners, particularly those whose social histories reflect marginalisation by dominant groups, has also called for the creation of just communities where subjugated knowledges are honoured and where different forms of diversity are valued (Kluth, Straut, and Biklen Citation2003). (956, italics in original)

As explained above, we further argue that educational value frames can be traced in different levels of the education system, such as in different steering documents, in public debate, and in the everyday school practice. The focus in this paper is on value frames that can be traced in teachers’ conceptual frameworks for teaching and learning.

To understand these value dimensions we draw on Schiro’s (Citation2013) work on curriculum ideologies. He identifies four curriculum ideologies: the scholar academic, the social efficiency, the learner-centred, and the social reconstruction ideologies. Each ideology represents different views on the purposes of education and ‘embodies distinct beliefs about the typeof knowledge that should be taught in school, the inherent nature of children, what school learning consist of, how teachers should instruct children, and how children should be assessed’ (Schiro Citation2013, 2). The four ideologies should be treated as archetypes ‘that portray an idealized model of a particular view of curriculum’ (Schiro Citation2013, 12). They exist side by side but can be more or less salient in different time eras and in different arenas.

The scholar academic ideology is characterised by a ‘traditional’ view of teaching and learning. The purpose of schooling is focused on sharing and transmitting knowledge developed within the Western humanistic tradition as codified in the academic disciplines. This wordings in the Swedish SCID national curricula, that education is about, ‘transmitting and developing a cultural heritage – values, traditions, language, knowledge – from one generation to the next’ (5), is an expression of this ideology. The importance of the teacher’s subject knowledge is emphasised. The social efficiency ideology emphasises the training of skills that are relevant in a competitive and changing labour market. Accountability and the importance of educational objectives, specified in terms of student performance, characterise this ideology. The wording of the SCID national curricula, when stating that education should develop ‘an approach that encourages entrepreneurship’ (6) is an expression of this ideology. The learner-centred ideology views the purpose of schooling to be self-actualising growth: teaching should be based on the motivation and interests of individual pupils. This ideology is characterised by the importance of individual learning styles and the integration of curricula. The SCID national curricula’s statement that education should ‘stimulate curiosity, creativity and self-confidence’ (6) corresponds to his ideology. Advocates of the social reconstruction ideology believe that the main purpose of education is to contribute to a more equal and equitable society. Wordings in the Swedish SCID national curricula along the lines that education should foster the development of pupils into ‘responsible individuals and citizens’ (5) or that nobody in school ‘should be discriminated on account of … functional disability’ (2) are expressions of this ideology. This ideology typically emphasises the importance of recognising that all knowledge bears social values and that schools should consider the problems and injustices of our society.

Schiro’s curriculum ideologies can be related to Labaree’s (Citation1997) discussion of three alternative goals for education: democratic equality, social efficiency, and social mobility (cf. Manzer Citation2003). Labaree relates these goals to ‘a fundamental source of strain at the core of any liberal democratic society, the tension between democratic politics (public rights) and capitalist markets (private rights), between majority control and individual liberty, between political equality and social inequality’ (Labaree Citation1997, 41). He argues that criticism of tracking and ability grouping and efforts to ‘reintegrate special education students in the regular classroom’ (45) are expressions of the democratic equality goal, which corresponds to Schiro’s social reconstruction ideology.

Aim and research questions

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to a better understanding of prerequisites for inclusive processes in education for pupils with ID. There are three research questions:

What characterises teaching in Swedish SCID and in comprehensive/upper secondary school according to teachers in SCID?

What characterises these teachers’ conceptual frameworks for teaching pupils with ID?

What is the actual and desired extent of collaboration with colleagues teaching in SCID and in comprehensive/upper secondary school?

Method

This study is part of a larger research project concerning teaching and learning environments for pupils with ID in the Swedish education system.

Participants

In the fall of 2016, a questionnaire was sent out to all teachers of pupils in SCID who were employed 100% in SCID and to all class teachers or mentors teaching pupils with ID in regular classes. For the purpose of this study results from teachers in SCID grades 1–9 and SCID upper secondary school (N = 2,871; 57.7% response rate) are included in the analysis.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of six parts, comprising 32 overarching questions with sub-questions. Most questions had closed response alternatives and some of them space for the participants to formulate their own responses. The majority of the questions employed a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = very important, 2 = rather important, 3 = not very important, 4 = not important at all and 5 = no opinion). Some questions asked participants to enter their response (e.g. age) whereas others involved choosing among multiple categories of responses. Finally, some questions involved ranking different statements about the purposes of schooling and schooling for pupils with ID (from 1 = most important to 4 = least important). In this paper, results from a selection of questions on teaching and learning and collaboration are reported.

Procedure

The questionnaire was pilot tested by six teachers and reviewed by experts from Statistics Sweden. It was distributed by post by Statistics Sweden and two reminders were sent out. Statistics Sweden also collected and compiled the responses. Upon submission, Statistics Sweden scanned and coded each questionnaire, scanned the information and then destroyed the questionnaires. The results were delivered to the research team in a de-identified data file, meaning that the researchers had no access to the personal data of the respondents. The data file was stored on a password-protected digital network. Furthermore, an information letter was attached to the survey explaining the purpose of the study, how results were to be used, how anonymity was protected, and that participation in the study was voluntary. It was not deemed necessary for the study to be reviewed and approved by an ethics committee. The study was conducted according to national ethical guidelines for social science research (The Swedish Research Council Citation2017).

Data analysis and presentation

In order to report a whole population response (i.e. for 2,871 respondents), Statistics Sweden calculated and constructed a statistical weight for each respondent. The weight was calculated through the translation vector type of teacher, that is, in SCID or comprehensive/upper secondary school, sex + age + marital status + foreign/Swedish background + city + income. Descriptive statistics are used in the presentation of the data, as the whole population was studied. The questions with graded responses were often dichotomised: for example, the response alternatives 1–4 (1 = very important, 2 = rather important, 3 = not very important and 4 = not important at all) were dichotomised into important (ratings of 1 and 2) and unimportant (ratings of 3 and 4). Regarding the questions that involved ranking, the percentage of respondents who ranked an item as the most important (i.e. = 1) is presented. This was done to present the complex set of data in a more accessible manner.

Results

Before reporting on the results of this study, some background information summarising responses from the questionnaire is presented on the organisation of learning environments and the teachers of pupils with ID. At the time of the survey a majority of SCIDs (74.4%) were situated in schools where there were two or more SCIDs. Only a minority (11.8%) were located at schools with only SCIDs. The most common SCID class size was 2–12 pupils (2–5 pupils = 44.6%; 6–12 pupils = 45.1%). In almost half of the classes (45.5%) there were usually three or more adults present during lessons; teachers very rarely worked alone in the class (11.0%). A majority of the teachers had a degree in preschool education (23.6%) or in comprehensive/upper secondary education (31.5%). Furthermore, 78.6% of the teachers had some university-level training in special needs education. Around a third (32.5%) had the equivalent of a master’s degree in special needs education.

What characterises teaching in SCID and in comprehensive/upper secondary school according to teachers in SCID?

To find out more about the teachers’ conceptions of teaching in SCID and comprehensive/upper secondary school three questions were posed: To what degree do you believe that teaching in SCID is characterised by … ? To what degree do you believe that teaching in comprehensive/upper secondary school should be characterised by … ? To what degree do you believe teaching in SCID should be characterised by … . Each question had three response alternatives regarding the holistic nature, care orientation and knowledge orientation of the curriculum/teaching in the two school forms. Answers were provided using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = to a very high degree, 2 = to a rather high degree, 3 = to a rather low degree, 4 = to a very low degree and 5 = no opinion). Here, the percentage of respondents who selected numbers 1 and 2 is reported.

The data showed that the teachers consider teaching in SCID to be of a more holistic nature (91.3%)and more care oriented (61.4%) than teaching in comprehensive/upper secondary school. Only a minority believed that teaching is more knowledge oriented in SCID than in comprehensive/upper secondary school (14.5%). Further, a majority believed that teaching in SCID should be of a more holistic nature than it is (60.7%). Less than half of the teachers believed that it should be more knowledge oriented (41.8%) and about a fifth believe that it should be more care oriented (20.5%). Regarding teaching in comprehensive/upper secondary school, a majority believed that teaching should be of a more holistic nature (83.6%), while less than half of the teachers believed that teaching in comprehensive/upper secondary school should be more knowledge oriented (42.2%) or more care oriented (30.8%) ().

Table 1. Teachers’ conception of teaching in SCID and comreprehensive/upper secondary school. Percentage of respondents agreeing to a very high or rather high extent.

What characterises the teachers’ conceptual frameworks for teaching pupils with ID?

In order to find out more about the teachers’ conceptual frameworks, five questions were posed on their views about the purpose of schooling, teaching, learning, knowledge, and childhood in relation to SCID. Each question had four alternatives representing the four different curriculum ideologies: social efficiency (SE), scholar academic (SA), learner-centred (LC) and social reconstruction ideology (SR). There were no explicit references to the different ideologies in the survey questions. For clarification purposes the ideologies are presented in parenthesis in the following example:

What should characterise childhood from a learning perspective?

a time of learning in preparation for a future career (SE);

a period of intellectual development with focus on developing a growing body of knowledge (SA);

a period when children should be children and their personalities allowed to develop according to their innate nature and interests (LC); or

a period of practice and preparation for acting for a better society (SR).

The respondents had to rank the alternatives from 1 (most important) to 4 (least important).

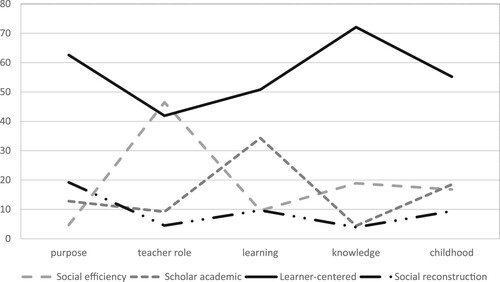

shows the percentage of respondents who ranked the different curriculum ideologies first, distributed over the five different areas (purpose, teaching, learning, knowledge and childhood). Results show that a majority of the teachers’ conceptual frameworks are in alignment with a learner-centred ideology in most areas.

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents who ranked different curriculum ideologies first, distributed over the five different areas.

A majority of the teachers (62.6%) believe that the most important purpose of schooling in SCID is offering a pleasant, stimulating and child-centred environment focused on the interests and abilities of the individual child, rather than, for example, developing the ability to understand societal problems in order to contribute to a more equitable and just society, in accordance with a social reconstruction ideology (4.7%).

Almost three quarters of the teachers (72.1%) believe that the most important knowledge for pupils in SCID is that which develops their personality. A minor share believe that the most important knowledge is that which strengthens their competitiveness on the labour market (18.9%). Only a very small share of the teachers believe that the most important knowledge is that which has been developed in Western cultures (4.4%) or knowledge in the form of social ideals such as equity and justice and an understanding of the implementation of theses ideals (3.9%).

A majority of the teachers (55.2%) also believe that the most important characteristic of childhood from a learning perspective is that it should be a period when children can be children and when their personalities are allowed to develop according to their innate nature and interests. A minor share believe that it should be a time of learning in preparation for a future career (16.8%) or a period of intellectual development with focused on developing a growing body of knowledge (18.5%).

As can be seen in , there is greater variety among the teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning. One group believe that the most important thing for a teacher is to supervise the teaching using evidence-based teaching strategies in order to optimise pupils’ knowledge development (46.5%). Another group of teachers (41.9%) believes, in contrast, that the most important role of a teacher is to be a mentor who creates learning and teaching situations that challenge pupils’ creation of meaning.

Regarding views about the most important factors for learning, two different ideologies emerge as most common. Half of the teachers (50.8%) express a learner-centred ideology, that is that the most important factor is that the pupil is motivated and actively engaged in learning activities, whereas, a third (34.3%) instead express a scholar academic view – namely, that the most important factors are accurate and precise learning goals and a structured knowledge content.

A sixth, complementary question was posed in order to find out more about the basis for the teachers’ conceptual frameworks: To what extent do you believe that SCID as a separate type of school form … ? The question had two response alternatives (is a good alternative to comprehensive/upper secondary school or should be dismantled). The respondents had to answer using a five-point Likert-type scale to indicate the extent of their agreement. Here, the percentage of respondents who chose number 1 (= agree to a very high extent) and number 2 (=agree to a rather high degree) is reported. Results show that an overwhelming majority of the respondents, 94.0 percent, believe that SCID is a good alternative to comprehensive/upper secondary school. A minority of 9.5%, believe that SCID should be dismantled as a separate type of school.

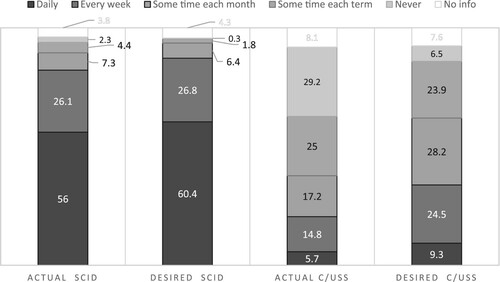

What is the teachers’ actual and desired collaboration with colleagues teaching in SCID and in comprehensive/upper secondary school?

Two questions – Do you often cooperate … .? How often would you like to cooperate … ? – were posed in order to learn more about cooperation between teachers. Each question had two sub-questions: … with teachers from comprehensive/upper secondary school in questions related to teaching? and … with teachers from SCID in questions related to teaching?. The respondents had to choose from among the following multiple-choice answers: yes, daily; yes, every week; yes, some time each month; yes, some time each term; and never.

As can be seen in the teachers tend to collaborate with colleagues in SCID, that is, they keep to their own school form. A large group of SCID teachers (82.1%) report that they collaborate with colleagues in SCID on a daily or weekly basis. Concerning collaboration between school types, only 20.5% of SCID teachers report that they collaborate on a daily or weekly basis. As mentioned above, however, almost 90% of the teachers in SCID do work in schools where teachers from comprehensive/upper secondary school constitute the majority of the teaching staff. While the teachers report a low frequency of collaboration between school types, shows that the teachers’ desired collaboration between school types is higher than their actual collaboration. A minority, but still a considerable share of the teachers, would like to cooperate regularly (every day or once a week) with teachers from the other school type (= 33.8%). However, a majority (52.1%) do not not wish to cooperate more than once a month or some time each term and 6.5% do not desire any cooperation at all.

Discussion

Based on the rationale that ‘the point of research on inclusive education should be to build robust and comprehensive analyses of exclusion’ (Slee Citation2011, 83), this study investigates views on education of teachers working in a segregated type of schooling, SCID. Hypothetically, results could have shown that a majority of the teachers believed that SCID should be dismantled, desired regular cooperation on a daily or weekly basis with teachers from comprehensive/upper secondary school and embraced a curriculum ideology in alignment with a social reconstruction ideology. However, actual views expressed by teachers working in SCID displayed a quite different pattern.

But, before discussing the results it is important to examine the limitations of the study. The response rate was 57.7%, which is acceptable, but an even higher value would have clearly been desirable. Altogether, the survey was rather extensive, and some questions may have been perceived as difficult to answer, which may have affected the response rate. We asked ‘big questions, such as questions about the purpose of schooling. The participants’ responses to some of the questions were limited to ranking different alternatives. In addition, since this article only reports on the highest-ranked alternatives for some of the questions, the result should be read as a first overview of some very complex issues, issues that have not previously been explored within the context of special classes for students with ID. The different results from the study do confirm each other, however, which strengthens the credibility of the study.

On a general level the results show that the teacher group as a whole represents a rather united group concerning views on education for pupils with ID. More specifically, they believe teaching in SCID to be of a more holistic nature than teaching in comprehensive/upper secondary school. They further believe that teaching in comprehensive/upper secondary school should be more like SCID in this respect. They consider SCID to be a good alternative to comprehensive/upper secondary school that should not be dismantled. They have a limited desire to cooperate with collegues from comprehensive/upper secondary school. Overall, they embrace a curriculum ideology with much resemblance to a learner-centred ideology, while very few embrace a social reconstruction ideology.

According to Abbott’s theory of systems of professions (Abbott Citation1988), professions are established partly through competition over who shall have the interpretative prerogative of certain problems, in this case the problem of teaching pupils with ID. This interpretation forms the basis for jurisdictional ‘claims to classify a problem, to reason about it, and to take action on it’ (Abbott Citation1988, 40). Evidently, dismantling SCID would threaten the (SCID) teachers’ jurisdictional claims on teaching pupils with ID. Following this line of reasoning it also becomes important to position the teaching and learning environment in SCID as a highly qualified environment compared to comprehensive/upper secondary school. Further, in order to protect the SCID teachers’ interpretative prerogative, it becomes important to establish the need for specialised knowledge and the need for developing such knowledge through cooperation within the specialised profession, that is, with other special teachers in SCID. This highlights the need consider how processes of protecting jurisdictional claims of special teachers in segregated school types operate in the development of inclusive education systems.

In the introduction we discussed that educators in many countries have experienced changes within the domain of educational ideologies, changes that many advocates of inclusion regard as quite contrary to ideas of inclusion: for example an increased focus on goal achievement (Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006) and seeing the objectives of education as ‘private goods’ rather than ‘public goods’ (Bunar and Sernhede Citation2013; Labaree Citation2010). Several studies have analysed how these and similar educational policy changes operate within the ‘regular’ school system creating processes of resilience to inclusive development (e.g. Isaksson and Lindqvist Citation2015; Magnússon, Göransson, and Lindqvist Citation2019; Ramberg Citation2015). Less attention has been paid to how such policy changes operate within segregated types of schools by creating or sustaining special teachers’ conceptual frameworks for teaching and learning within segregated types of schools. In other words, why should we expect teachers in segregated school types to embrace educational ideologies different from those embraced by teachers in ‘regular’ school? We argue that the last decade’s focus on education as ‘private goods’ can be traced, or detected, in the conceptual framework for teaching – with an accent on learner-centred ideology, rather than reconstructive ideology. The shift in conceptualisation is also reflected in the views on collaboration expressed by teachers who participated in this study, and how they consider the status of SCID as a segregated type of school.

To summarise, the results of this study highlight the importance of investigating, within segregated types of schools, processes of resistance to and processes promoting the development of inclusive schools and education systems. We argue that, while research and debate about inclusive education are important, both are insufficient without analyses of existing types of segregated schooling.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kerstin Göransson

Kerstin Göransson is a professor in special needs education at Karlstad University. Her research interests include inclusive education in relation to educational ideologies, curriculum theory and sociology of professions.

Karin Bengtsson

Karin Bengtsson is a senior lecturer in special needs education at Karlstad University. Her research interests include teaching and learning of children in need of special support, with a special focus on communication and interaction.

Susanne Hansson

Susanne Hansson is a senior lecturer in education, specialising in special education at Karlstad University. Her research concerns teaching of children in need of special support, ethics and interpersonal relations in educational contexts.

Nina Klang

Nina Klang is a senior lecturer in education, specialising in special education at Uppsala University. Her research interests center on instruction and curriculum for pupils in need of special support.

Gunilla Lindqvist

Gunilla Lindqvist is associate professor in education and senior lecturer in education, specialising in special education at Uppsala University. She conducts research in preschool, primary school and special needs school. Gunilla´s research focus is especially directed towards occupational groups' views on special needs, mostly related to the concept of inclusion.

Claes Nilholm

Claes Nilholm is a professor in education, specialising in special education at Uppsala University. His main research focus is theories of inclusion and inclusion as a concept and phenomenon.

References

- Abbott, A. 1988. The System of Professions. An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- Ainscow, M., T. Booth, and A. Dyson. 2006. “Inclusion and the Standards Agenda: Negotiating Policy Pressures in England.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 10 (4-5): 295–308. doi:10.1080/13603110500430633.

- Areschoug, J. 2000. “Det sinnesslöa skolbarnet: Undervisning, tvång och medborgarskap 1925/1954.” [The Feeble-Minded Schoolchild: Education, Coercion and Citizenship 1925/1954]. Doctoral thesis. Linköping: Linköping University. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-29748</div>

- Arnesen, L., R. Mietola, and E. Lahelma. 2007. “Language of Inclusion and Diversity: Policy Discourses and Social Practices in Finnish and Norwegian Schools.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 11 (1): 97–110. doi:10.1080/13603110600601034.

- Avramidis, E., and B. Norwich. 2002. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Integration/Inclusion: A Review of the Literature.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 17 (2): 129–147. doi:10.1080/08856250210129056.

- Ball, S. J., M. Maguire, and A. Braun. 2012. How Schools Do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary Schools. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Berthén, D. 2007. “Förberedelse för särskildhet. Särskolans pedaggiska arbete i ett verksamhetsteoretiskt perspektiv.” [Preparing for Segregation: Educational Work Within the Swedish Special School – An Activity Thepretical Approach]. Doctoral thesis. Karlstad: Karlstad University.

- Booth, T., M. Ainscow, K. Black-Hawkins, M. Vaughan, and L. Shaw. 2000. Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools. Bristol: Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education.

- Bouck, E. C. 2004. “State of Curriculum for Secondary Students With Mild Mental Retardation.” Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities 39 (2): 169–176.

- Bunar, N., and O. Sernhede. 2013. Skolan och ojämlikhetens urbana geografi [School and Inequalities' Urban Geography]. Stockholm: Daidalos.

- Clark, C., A. Dyson, and A. Millward. 1998. “Theorising Special Education: Time To Move On?” In Theorising Special Education, edited by C. Clark, A. Dyson, and A. Milward, 156–173. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Croll, P., and D. Moses. 2000. “Continuity and Change in Special School Provision: Some Perspectives on Local Education Authority Policy-Making.” British Educational Research Journal 26 (2): 177–190. doi:10.1177/001440290607200401. doi: 10.1080/01411920050000935

- EASNIE. 2018. European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education: 2016 Dataset Cross-Country Report. Edited by J. Ramberg, A. Lénárt, and A. Watkins. Odense. Accessed April 2019. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/european-agency-statistics-inclusive-education-2016-dataset-cross-country.

- Erwin, E. J., and M. Guintini. 2000. “Inclusion and Classroom Membership in Early Childhood.” International Journal of Disability 47 (3): 237–257.

- European Commission. 2005. Key Data on Education in Europe 2005. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Ferguson, D. L. 2008. “International Trends in Inclusive Education: The Continuing Challenge to Teach Each One and Everyone.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 23 (2): 109–120. doi:10.1080/08856250801946236.

- Florian, L. 2008. “Inclusion: Special or Inclusive Education: Future Trends.” British Journal of Special Education 35 (4): 202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2008.00402.x

- Florian, L., and R. Kershner. 2009. “Inclusive Pedagogy.” In Knowledge, Values and Educational Policies: A Critical Perspective, edited by H. Daniels, H. Lauder, and J. Porter, 177–183. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Government Office. 2011. Läroplan för grundsärskolan (Lsär11) [National Curriculum for the Compulsory School for Students With Intellectual Disability]. Stockholm: Swedish Natiojnal Agency for Education Fritzes AB.

- Government Office. 2013. Läroplan för grundsärskolan [National Curriculum for Upper Secondary School for Students With Intellectual Disability]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education Fritzes AB.

- Isaksson, J., and R. Lindqvist. 2015. “What Is the Meaning of Special Education? Problem Representations in Swedish Policy Documents: Late 1970s–2014.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 30 (1): 122–137. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2014.964920

- Kluth, P. 2003. ‘You’re Going to Love this Kid!’: Teaching Students with Autism in the Inclusive Classroom. Baltimore: Paul Brookes.

- Kluth, P., D. M. Straut, and D. Biklen. 2003. Access to Academics for All Students: Critical Approaches to Inclusive Curriculum, Instruction, and Policy. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

- Labaree, D. 1997. “Public Goods, Private Goods: The American Struggle Over Educational Goals.” American Research Journal 34 (1): 39–81. doi:10.3102/00028312034001039.

- Labaree, D. F. 2010. Someone Has To Fail: The Zero-Sum Game of Public Schooling. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lundgren, U. P. 1999. “Ramfaktorteori och praktisk utbildningsplanering.” [Frame Factor Theory and Curriculum, in Swedish]. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 4 (1): 31–41.

- Magnússon, G., K. Göransson, and G. Lindqvist. 2019. “Contextualizing Inclusive Education in Educational Policy: The Case of Sweden.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy. doi:10.1080/20020317.2019.1586512.

- Manzer, R. 2003. Educational Regimes and Anglo-American Democracy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Meyer, L. H., H. S. Park, M. Grenot-Scheyer, and I. S. Schwartz. 1998. Making Friends: The Influences of Culture and Development. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Moljord, G. 2017. “Curriculum Research for Students With Intellectual Disabilities: A Content-Analytic Review.” European Journal of Special Needs Education. doi:10.1080/08856257.2017.1408222.

- Naraian, S. 2011. “Seeking Transparency: The Production of an Inclusive Classroom Community.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (9): 955–973. doi:10.1080/13603110903477397.

- Nietupski, J., S. Hamre-Nietupski, S. Curtin, and K. Shrikanth. 1997. “A Review of Curricular Research in Severe Disabilities from 1976 to 1995 in Six Selected Journals.” The Journal of Special Education 31 (1): 36–55. doi:10.1177/002246699703100104.

- Nilsen, S. 2010. “Moving Towards an Educational Policy for Inclusion? Main Reform Stages in the Development of the Norwegian Unitary School System.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (5): 479–497. doi:10.1080/13603110802632217.

- Norwich, B. 2008. “Special Schools: What Future for Special Schools and Inclusion? Conceptual and Professional Perspectives.” British Journal of Special Education 35 (3): 136–143. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8578.2008.00387.x.

- OECD. 2011. Social Justice in the OECD: How Do the Member States Compare? Sustainable Governance Indicators 2011. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- OECD. 2018. Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility. Paris: PISA, OECD. doi:10.1787/9789264073234-en.

- OSS. 2019. Barn/elever läsåret 2018/19 [Children/pupils academic year 2018/19]. www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sok-statistik-om-forskola-skola-och-vuxenutbildning?sok=SokC&verkform=Grundsärskolan.

- Public Law 800. 2010. Skollagen [Education Act]. Stockholm: Swedish Code of Statutes.

- Ramberg, J. 2015. “Special Education in Swedish Upper Secondary Schools. Resources, Ability Grouping and Organisation.” Diss. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Rix, J., K. Sheehy, F. Fletcher-Campbell, M. Crisp, and A. Harper. 2013. “Exploring Provision for Children Identified With Special Educational Needs: An International Review of Policy and Practice.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 28 (4): 375–391. doi:10.1080/08856257.2013.812403.

- Røren, O. 2007. “Idioternas tid: Tankestilar inom den tidiga idiotskolan 1840–1872.” [The Time of the Idiots: Thought-Styles in the Early Institutional Schools for Idiots 1840–1872]. Doctoral thesis. Stockholm: Stockholm University. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-7105</div>.

- Sapon-Shevin, M. 1999. Because We Can Change the World: A Practical Guide to Building Cooperative, Inclusive Classroom Communities. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Schiro, M. S. 2013. Curriculum Theory: Conflicting Visions and Enduring Concerns. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Shurr, J., and E. C. Bouck. 2013. “Research on Curriculum for Students With Moderate and Severe Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review.” Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 48 (1): 76–87.

- Slee, R. 2011. The Irregular School: Exclusion, Schooling and Inclusive Education. Oxon: Routledge.

- SNAE. 1996. Kvalitet i särskola samt Skolverkets planerade insatser och prioriteringar [Quality in the SCIDs and the Agency’s Planned Actions and Priorities]. (Dnr 1996:565). Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- SNAE. 1999. Uppföljning och utvärdering av försöksverksamheten med ökat föräldrainflytande över val av skolform för utvecklingsstörda barn [Follow-Up and Assessment of the Experimental Work of Increased Parental Influence Over Choice of School Form for Children With Intellectual Disability]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- SNAE. 2001. Kvalitet i särskola: en fråga om värderingar [Quality in SCIDs: A Question of Values]. (Dnr: 2000:2037). Stockholm: Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education].

- Sturm, T. 2018. “Constructing and Addressing Differences in Inclusive Schooling: Comparing Cases from Germany, Norway and the United States.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–14. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1444105.

- The Swedish Research Council. 2017. God forskningssed [Good Research Practice]. Stockholm: The Swedish Research Council.

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate. 2010. Undervisningen i svenska grundsärskolan [Teaching of Swedish in Schools for Pupils With Intellectual Disability]. Stockholm: Skolinspektionen.

- UNESCO. 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education: Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO.

- United Nations. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities. New York: United Nations. http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf.

- van Garderen, D., M. Stormont, and N. Goel. 2012. “Collaboration Between General and Special Educators and Student Outcomes: A Need for More Research.” Psychology in the Schools 49 (5): 483–497. doi:10.1002/pits.21610.

- Villa, R. A., and J. S. Thousand. 2000. Restructuring for Caring and Effective Education: Piecing the Puzzle Together. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Paul Brookes.

- Wehmeyer, M. L., and D. J. Smith. 2017. “Historical Understandings of Inteelectual Disability and the Emergence of Special Education.” In Handbook of Research-Based Practices for Educating Students With Intellectuakl Disability, edited by M. L. Wehmeyer and K. A. Shogren, 3–16. New York, NY: Routledge.