ABSTRACT

Due to the rising linguistic heterogeneity in schools, the inclusion of pupils with a first language other than the language of instruction is one of the major challenges of education systems all over the world. In this paper, attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the inclusion of pupils with a first language other than the language of instruction are examined. Additionally, as the paper focused on how the participants perceive the development of this pupils in different school settings (fully included, partly included, fully segregated).

Data from 1501 participants were investigated. Descriptive results showed that pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusive schooling of pupils with different language skills in composite classes were rather positive, while attitudes of in-service teachers and parents rather tend to be neutral. Regarding the results concerning the participants’ attitudes towards the pupils’ development in different school settings, all three sub-groups belief that pupils with German as first language would develop in a more positive way, compared to pupils without German as first language. Moreover, the migration background of pre-service teachers and parents had a positive influence on the participants’ attitudes.

Introduction

Due to increasing language heterogeneity in classroom, caused by the rise of pupils with migrant background, it is essential to investigate how school systems respond to these circumstances. Since the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations Citation2006) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs – specifically SDG 4), equal education and the promotion of lifelong learning for everyone is emphasised. The SDG 4 highlights the relevance of teachers’ engagement with diversity of pupils and their professionalisation within this field (United Nations Citation2017).

Inclusion is often used in connection with ‘special educational needs’ and since the late 1990s, this expression is used for ethnic minorities also (De Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2011). Accordingly, it should be the main duty of each education system to include all pupils, no matter which linguistic, ethnic or cultural background they belong to (OECD Citation2016). But at the same time, their integration seems to be one of the major challenges for European countries (Crul, Schneider, and Lelie Citation2012).

The rise of language heterogeneity in our classrooms

Linguistic diversity in classrooms has been increasing: in 2015, 12.5% of the pupils in OECD countries had a migrant background – which means both of the parents were born in another country than the pupil studying at the school and speak a language other than the language of instruction. Beyond this, the past results of PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) encouraged scientific and social discussions about the low school performance of pupils with migrant background, compared to their non-migrant peers. Reasons are mainly seen as insufficient language skills in the language of instruction (OECD Citation2016). Pupils with insufficient language skills are also often those ones who sought refuge because they have to leave their home-country as a result of wars (Plutzar Citation2016). These pupils are not only faced with a foreign language of instruction, but also with an unknown culture and an unfamiliar school system (De Boer, Brass, and Bruns Citation2018). For instance, research showed that culture may influence the pupils’ learning (Ameta Citation2013). Further, school performances of pupils with migrant background in general are influenced not only by language barriers but also by teachers’ judgments and attitudes (Glock, Kovacs, and Pit-ten Cate Citation2018). As inclusion refers to produce inclusive communities within an inclusive school environment that further appreciates heterogeneity (Norwich and Koutsouris Citation2017) the attitudes of the involved people towards inclusive schooling are important for its high-quality implementation. In the present context, not only do the attitudes of in-service teachers (as they already work in the field) play a key role in the inclusion of pupils with language barriers, pre-service teachers’ attitudes are also important because they have to be prepared for the increasing heterogeneity in classrooms (Forlin et al. Citation2009). Likewise, parents’ attitudes are important too, because children learn and adopt attitudes from their parents (Aboud and Amato Citation2001) and through their perspective, it is possible to obtain an external view of inclusive education practices and therefore parents can also promote inclusive practices (Paseka and Schwab Citation2020).

The concept of attitudes towards the inclusion of pupils with different first languages

Attitudes towards inclusion influence someone’s behaviour and the teachers’ educational practices. Their attitudes are in further consequence affected by their values of teaching and learning (Pit-ten Cate and Glock Citation2019). Therefore, researchers highlighted the importance to investigate attitudes towards specific subgroups within educational research in the field of inclusive education (Pit-ten Cate et al. Citation2019).

A review of the literature revealed that the concept of attitudes is described in different ways, with there being no uniform definition (de Boer et al. Citation2012). Gall, Borg, and Gall (Citation1996, 273) stated broadly, ‘an attitude is an individual’s viewpoint or disposition towards a particular ‘object’ (a person, a thing, an idea, etc.)’. Eagly and Chaiken (Citation1993, 1) defined attitudes as ‘a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favour or disfavour.’ The three-component theory of Eagly and Chaiken (Citation1993) constitutes a theoretical framework in which attitudes consist of three components: (1) cognitive, (2) affective and (3) behavioural.

Teachers and as well parents should keep in mind that learning a foreign language is a major challenge for pupils. In this line, Canagarajah (Citation2016) emphasised that being a native speaker in the host country should not be the main target for the pupils with another first language. They should have the chance to adopt different strategies to communicate successfully with their peers. Acquiring a foreign language should not be tied on testing pupils’ skills and abilities (Gee Citation2003).

Research on attitudes of teachers and parents

The results of the author’s extended literature review indicated that there is a lack of research relating to the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents in the context of language heterogeneity.

A lot of research about teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion in general had been carried out so far. Literature reviews of Schwab (Citation2018) and De Boer et al. (Citation2012) showed that attitudes of female in-service teachers tend to be more positive, compared to those of male in-service teachers. Another important factor concerning the attitudes of in-service teachers towards inclusion in general is the duration of their teaching experience. However, research indicated that experience can have either a positive (Avramidis, Bayliss, and Burden Citation2000) or a negative effect (Alghazo and Naggar Gaad Citation2004). For instance, Alghazo and Naggar Gaad (Citation2004) demonstrated that the attitudes of teachers with one to five years of teaching experience towards the inclusion of pupils with special needs are more positive, compared to those with 12 or more years of experience.

Addressing attitudes towards cultural diversity, the teachers’ own ethnic background has a positive influence on their attitudes towards ethnic and linguistic heterogeneity (Glock and Kleen Citation2019).

Referring to pre-service teachers’ attitudes, literature review showed that there are demographic differences that influence such attitudes towards inclusion in general: Avramidis, Bayliss, and Burden (Citation2000) for example, reported that female pre-service teachers are more tolerant of implementing inclusive education. Another important factor is the ethnic background of pre-service teachers: those who belong to an ethnic minority group have a more positive attitude towards pupils from ethnic minorities, compared to pre-service teachers who belong to an ethnic majority (Glock and Kleen Citation2019).

As stated above, the attitudes of parents towards the inclusion of pupils with special educational needs is considered to be relevant as well; but relatively little research has focused on this issue. Parents want to have the best support and the best educational opportunities for their children. Therefore, they play a certain role in decisions regarding school choices for their children (Schwab Citation2018).

Austria’s current way of dealing with pupils with a first language different from the language of instruction

In the school year 2018–2019, Austrian policymakers developed a new model to promote pupils’ German language skills: all pupils with immigrant background are tested with a standardised measurement when they enter school. Based on this result, it is determined whether (a) the pupil has sufficient language skills (‘ordentlicheR SchülerIn’) and visits a regular class (b) the pupil has deficient language skills (‘außerordentlicheR SchülerIn’), visits a regular class and receives additional language promotion (6 h/week – German language support course) or (c) the pupil has insufficient language skills (‘außerordentlicheR SchülerIn’), visits the German language support class and receives 15 h per week of language training in primary school or 20 h per week of language training in secondary school (BMBWF Citation2018).

The current study

Hence, the introduction of German language tuition and support classes and German language tuition and support courses is a new strategy in Austria, it is important to investigate the attitudes of those who are faced with this support measure.

The first research question refers to the general attitudes towards the inclusion of pupils with different language abilities:

(1a) Do the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the inclusion of pupils with different language skills tend to be neutral, positive or negative?

(1b) Do the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the inclusion of pupils with different language skills differ from each other’s?

(1c) Does gender, migration background or experience influence the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the inclusion of pupils with different language skills?

(1c/a) Female in-service and pre-service teachers have more positive attitudes towards the inclusion of pupils with different language skills, compared to male in-service and pre-service teachers.

(1c/b) Participants with migration background have more positive attitudes towards the inclusion of pupils with different language skills, compared to those without a migration background.

(1c/c) Teaching experience is positively correlated with more positive attitudes towards the inclusion of pupils with different language skills.

(1c/d) Parents whose children attend classes where pupils with different language skills are educated have more positive attitudes towards this matter than parents whose children visit regular classes.

The next research questions focuses on different school settings (fully included, partly included, fully – segregated):

(2a) Do the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the development of pupils with and without German as first language differ from each other?

(2b) Does the school setting (fully included, partly included, fully segregated) influence the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the development of pupils without German as first language?

(2c) Does gender, migration background or experience influence the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the development of pupils with different language skills in different school settings (fully included, partly included, fully segregated)?

(2c/a) Female in-service and pre-service teachers have more positive attitudes towards the development of pupils with and without German as first language in the varying case vignettes, compared to male in-service and pre-service teachers.

(2c/b) In-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents with migration background have more positive attitudes towards the development of pupils with and without German as first language in the varying case vignettes, compared to those without a migration background.

Method and materials

Research instruments

General attitudes towards teaching pupils with different abilities in the instruction language German in composite classes

To assess the general attitudes towards teaching pupils with different language abilities in German as the language of instruction in composite classes, a translated and adapted version of the Attitudes to Inclusion Scale (AIS; Sharma and Jacobs Citation2016) was used (see Appendix 1). Original items like: ‘I believe that all students regardless of their ability should be taught in regular classrooms’ were modified to the present context (‘I believe that all students regardless of their German language abilities should be taught in the regular classrooms.’).

Modelling results indicated that the scale measures ‘feelings’ and ‘beliefs’ about inclusion. Sharma and Jacobs (Citation2016) showed acceptable levels of reliability for the original AIS. The internal consistency of the 10 items for the three present samples was high (Cronbach’s alpha = .91 – .94).

The scale consists of 10 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Within this study, all items were used in the same way for the three samples (in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents).

Attitudes towards the inclusion and development of pupils in different school settings

Preliminary work of de Boer (2012), Schwab et al. (Citation2012) and Schwab (Citation2018) showed that it is important to use case vignettes to assess specifically for the characteristics of the pupil and the specific school settings. Therefore, different case vignettes with varying types of language abilities were developed (see Appendix 2). The case vignettes consisted of a short text introducing the school setting. Those for the in-service teachers and pre-service teachers started with: ‘Imagine yourself teaching in a class with pupils with … ’

The case vignettes for the parents were slightly modified to: ‘Imagine your child visits a class, where … ’ For the different types of school settings, a total of five varying case vignettes were constructed:

participation in a regular class (fully included; example above)

attendance in a German language tuition and support course (partly included)

attendance in a German language tuition and support class (fully segregated)

Most of the studies do not use any references to pupils without special educational needs in relation to language barriers. Thus, we constructed a case vignette representing a regular pupil who has German as first language as a reference (control case).

Each case vignette consisted of six items (‘I think that this child feels alone and excluded in this class.’) and were rated on a four-point Likert scale from not at all true (1) to certainly true (4).

In order to assess participants’ attitudes towards the development of pupils in different school settings, the ‘Attitudes towards Inclusion Scale’ (Schwab et al. Citation2012) was translated and adapted for the purpose of the present study. Schwab et al. (Citation2012) showed high reliability for the six items of the integration case (Cronbach’s alpha = .82). Regarding the internal consistency for the different vignettes for the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .82 to .88 for the fully included setting, .79 to .86 for the partly included setting, .82 to .91 for the fully segregated setting and .76 to .87 for the control case.

Participants and settings

The data collection for the present study was carried out from May to October 2019 in six (out of nine) different federal states of Austria and consists of three different samples.

Sample A: in-service teachers

Two-hundred twenty-one in-service teachers (188 female and 33 male) which were mostly trained as regular or subject teacher and some of them were special needs teachers in Vienna (Austria’s capital), Lower Austria and Burgenland (federal states of Austria) participated in the survey using a paper pencil version of the questionnaire. The age of the in-service teachers varied from 24 to 63 (M = 42.43, SD = 11.9) and they had between 2 months and 43 years of work experience. 92.4% were teaching in regular classes, 3.9% in German language tuition and support courses and 1.5% in German language tuition and support classes. 9.5% of them had an additional training in teaching pupils having German as second language. 5.5% had a migration background. In this survey, having a migration background is defined by having either a first language other than German or having German and another language as first language. Due to the small sample size of in-service teachers having a migration background this subsample was excluded for examining the effect of participants’ migrant background on attitudes.

Sample B: pre-service teachers

In total, 899 pre-service teachers (686 female, 208 male and 5 neutral) were questioned online using a tool called ‘lime survey’, of whom 677 fully completed the questionnaire. The sample consisted of pre-service teachers of different fields of study in Vienna, Styria and Vorarlberg (federal states of Austria). The age varied from 18 to 54 years (M = 23.88, SD = 5.87) and 14.9% of them had a migration background. Regarding the experience with pupils with different German language abilities, 75.9% of the pre-service teachers indicated that they had already gained experience with pupils having another first language as German, with insufficient German language skills. Only 5.7% gained practical experience in German language tuition and support classes and 4.7% in German language tuition and support courses.

Sample C: parents

In total, 381 parents (296 female and 85 male) filled out the questionnaire in paper pencil format that was handed out in public places and schools in Vienna and Upper Austria (federal state of Austria). The age varied from 25 to 85 years (M = 40.53, SD = 6.93) and 25.7% had a migration background. 9.9% indicated that their child would visit a German language tuition and support class or a German language tuition and support course. Further, 72.3% of the parents stated that their child would visit a class where pupils with different language abilities (speaking other first languages than German) are educated.

Data analysis

To answer the research questions descriptive statistics, t-tests and univariate analyses of variance were used. Parametric analyses were preferred even if the data were not normally distributed. This procedure is relatively robust towards the violation of normal distribution of the data if the sample size is big enough (Tabachnick and Fidell Citation2006). Cohen’s d and eta square (Eta2) were used to interpret the effect sizes. According to Cohen (Citation1988), values around d = .2 or Eta2 = .01 can be interpreted as weak effect. Values around d = .5 or Eta2 = .06 can be interpreted as medium effect. If the Cohen’s d is around .8 and Eta2 around .14 the effect size is high.

To evaluate the attitudes of pre-service teachers, in-service teachers and parents, the sum of the items was computed, divided by the number of items. Since a 7-point Likert scale was used for the general attitudes towards pupils with language barriers, the theoretical mean of the scale is 4. Similar to other studies (e.g. Schwab Citation2018), a rule of thumb was used: attitudes that were 3.0 or lower were defined as negative and values from 5.0 upwards were defined as positive attitudes. For the attitudes towards inclusion and the development of pupils in diverse school settings, a 4-point Likert scale was used. The theoretical mean of the scale is 2.5. Following the rule of thumb, attitudes that were 2.0 or lower were defined as negative and values from 3.0 upwards as positive attitudes.

Results

General attitudes towards teaching pupils with different language skills in composite classes

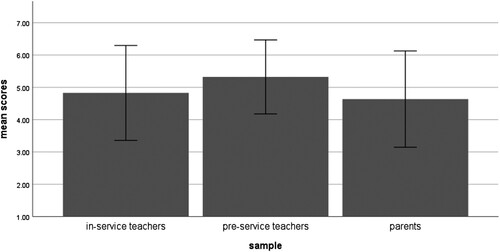

provides an overview of the scale means for the three sub-samples (see also ). Results indicated that the pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of pupils with different language skills were positive, while attitudes of in-service teachers and parents tend to be rather neutral. A closer look at item 10 (‘I think that pupils with poor German language abilities should be taught in separate German language tuition and support classes’) showed that 20.8% of in-service teachers and 23.1% of parents rated this item with ‘strongly agree.’ Contrary results showed the pre-service teachers’ sample: only 6.7% of the sample agreed with this statement.

Table 1. Mean scores towards the common teaching of pupils with different language skills.

An univariate analysis of variance with the independent variables sub-sample (in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents), gender (female and male) and migration background (no migration background vs. migration background) was calculated. Results confirmed a significant main effect for the sub-sample (F2 = 4.514, p < .05, partial Eta2 = .006). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that pre-service teachers have significantly more positive attitudes towards teaching pupils with different language abilities in composite classes, compared to in-service teachers (p < .01) and parents (p < .01). No significant difference was found between the in-service teachers and parents attitudes. Moreover, a significant main effect for the migration background revealed (F1 = 21.259, p < .01, partial Eta2 = .014). Participants with migration background tended to have more positive attitudes towards the teaching pupils with different language abilities in composite classes, compared to participants without migration background. For gender, no group difference was found (F1 = .245, n.s.).

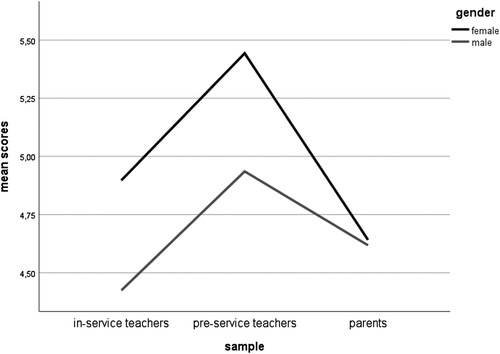

The results of the univariate analysis of variance showed a significant interaction effect for sample and gender (F2 = 4.552, p < .05, partial Eta2 = .006; see ). Female pre-service teachers tended to have more positive attitudes towards teaching pupils with different language abilities in composite classes, compared to male pre-service teachers (p < .01, d = .44). Further, mothers had more positive attitudes compared to fathers (p < .05, d = .01). For the sub-sample of in-service teachers, no effect for gender was found (n.s.).

Figure 2. Attitudes towards the common teaching of pupils with different language skills separately for female and male participants.

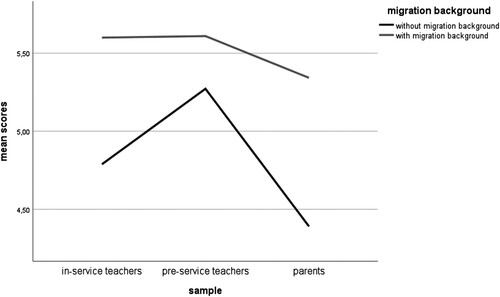

In addition, an interaction effect between the sample and migration background (F2 = 6.301, p < .01, partial Eta2 = .009, see ) was shown. While parents with migration background tended to have more positive attitudes compared to people without migration background (p < .01, d = .64), for the sub-sample of pre-service teachers, no effect for migration background was found (n.s.).

Figure 3. Attitudes towards the common teaching of pupils with different language skills separately for participants with and without migration background.

To ascertain whether teaching experience has an influence on in-service teachers’ attitudes, Pearson’s correlation was applied and showed that participants with more years of service had less positive attitudes towards teaching pupils with different language skills in composite classes (r = −.32, p<.01).

Further, t-test results showed that parents whose children attend a class with pupils with German as first language, had less positive attitudes towards teaching pupils with different language skills in composite classes, compared to parents whose children attended classes where pupils with different language abilities were educated (t310 = −2.067, p < .05, d = .3).

Attitudes concerning the pupils’ development in different school settings

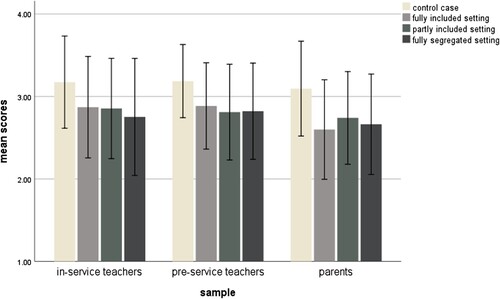

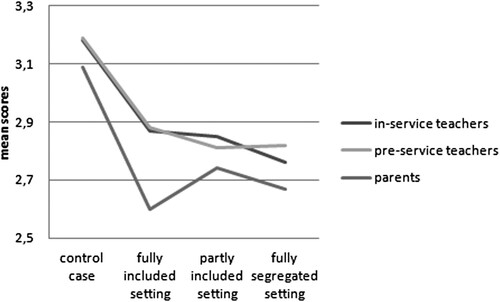

presents the mean scores of the attitudes towards the development of pupils in different school settings (see also ). Results indicated that each sub-sample has the most positive attitudes towards the development of pupil with German as first language.

Figure 4. Mean scores and standard deviations of the different integration settings of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents.

Table 2. Mean scores of the attitudes towards the development of the pupils in the different integration settings.

To examine whether the school setting (fully included, partly included, fully segregated and the control case) influenced the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the development of pupils in the different school settings, a variance analysis for repeated measurements (between subject factors: sub-group, gender and migration background; within subject factors: mean scores of the different school settings) was computed. Results indicated a significant main effect for the different school settings (F3 = 20.16, p < .01, partial Eta2 = .05). The attitudes within the control case (pupils with German as first language) were more positive, compared to pupils without German as first language within the fully included setting (p < .01, d = .59), the partly included setting (p < .01, d = .55) and within the fully segregated setting (p < .01, d = .53). However, neither the attitudes towards the development of pupils within the fully included setting differ from the partly included setting and the fully segregated setting, nor do the attitudes differ between the partly included setting and the fully segregated setting (n.s.).

Additionally, an interaction effect between the school settings and sub-group was found (F3 = 3.245, p < .05, partial Eta2 = .008; see ). According to the results of follow-up analyses, pre-service teachers believed that pupils without German as first language develop more positively in the fully included setting, compared to the partly included (t747 = 3.616, p < .01, d = .1) and the fully segregated setting (t734 = 2.450, p < .05, d = .09). Further, parents had more negative attitudes towards the development of pupils without German as first language in a fully included setting as in a partly included setting (t345 = 4.439, p < .01, d = .2). Comparing the parents’ attitudes within the partly included and the fully segregated settings, t-test for dependent samples showed that parents had more positive attitudes within the partly included setting, compared to the fully segregated setting (t350 = 2.038, p < .05, d = .1).

Figure 5. Attitudes towards the development of pupils within the different integration settings separately for the three sub-groups.

Results further showed a significant main effect for the sub-sample (in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents) (F2 = 4.859, p < .01, partial Eta2 = .008). Post-hoc tests indicated that parents had more negative attitudes within the different school settings than in- service teachers and pre-service teachers (p < .01).

In addition, a main effect for gender was found (F2 = 4.960, p < .01, partial Eta2 = .008). Females had more positive attitudes compared to males (p < .01). No effect for the migration background was found (F1 = .289, n.s.)

Discussion

The present literature review showed a lack of research in examining attitudes towards language heterogeneity. There are many studies that focus on attitudes towards inclusion in general or with a focus on special educational needs, but relatively little research focused on pupils with language barriers. However, according to scientific literature, lacking competences in the language of instruction can be seen as a significant learning barrier. The purpose of the current study was to determine the attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards the inclusive schooling of pupils with different language skills and how the participants perceive their development in different school settings (fully included, partly included, fully segregated) which have recently been installed in Austria.

Results indicate that in-service teachers’ and parents’ attitudes towards teaching pupils with different language abilities in composite classes tend to be neutral while pre-service teachers’ attitudes are rather positive. This might underpin earlier studies indicating that the general philosophy and the normative idea of inclusive schooling is seen to be important for teachers but attitudes are more reserved when it comes to practice in the teachers’ own class (see e.g. Schwab Citation2018; Hecht, Niedermair, and Feyerer Citation2016). However, it also indicates that there exists reservation within the inclusion of pupils with migrant background. As Austria is placed in a multilingual, multicultural and multi-ethnic society it is important that diversity is positively valued from its population.

One possible explanation for the differences in attitudes of the three groups can be higher awareness of possible challenges of in-service teachers in the context of language heterogeneity as they have to deal day by day with teaching those students. The question arises how to reduce this effect - for example, further training of in-service teachers or a better preparation during teacher training can be contemplated. Taking this into account, Austria has therefore established a new concept of teacher education where inclusive competences of pre-service teachers should be acquired (Braunsteiner et al. Citation2019) as it was proven that teacher education has a relevant effect on in-service teachers’ attitudes (Symeonidou Citation2017). These are very important aspects as the implementation of German language tuitions and support classes and German language tuition and support courses is new in Austria. This involves that also and teachers have to get prepared to teach not only within heterogeneous classes but also within these new integration settings. As it was further found out that teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion decrease over time (Mintz et al. Citation2020) it is of major importance to focus on the pre-service teachers. They may need additional support to transfer their skills from teacher education to the classroom. For parents, however, it might be possible to include awareness programs too. They also need to realise also the advantages of inclusion for their own child and also other children. Referring to the findings of Esses, Hamilton, and Gaucher (Citation2017) parents’ attitudes towards immigrants in general tend to be rather negative. So it should not be forgotten to focus as well on parents’ attitudes as they play a certain role in promoting inclusive education from an external position. Not just for ethics, social inclusion and social justice, providing the best learning opportunities for all pupils is important also for the inclusion in future labour market. Giving all students the maximum possibilities for their social, emotional and especially learning development seems to be important for Austria’s future. Furthermore, it is crucial that teachers are aware of the fact that many pupils with migration background sought refuge due to wars and maybe some of them experienced trauma (Plutzar Citation2016). Due to this, education systems have to sensitise teachers to these aspects. Moreover, in such special situations, education systems have to support teachers in the form of appropriate resources within these heterogeneous settings as it was found out that they play a certain role in the context of the teachers’ attitudes within the inclusion of pupils with different language abilities (Gitschthaler et al. Citation2020).

According to the present results, the migration background of pre-service teachers and parents (speaking either a first language other than German or German and another language as first language) has a positive influence on the participants’ attitudes These findings are consistent with those of Glock and Kleen (Citation2019). The question rises as to whether there is a need to improve the understanding and openness for cultural diversity during teaching education or in further training, especially for people without migration background.

Implications of results

Teachers have to keep in mind that learning a foreign language should not be tied on acquiring the basic skills of reading and writing (Gee Citation2003). Moreover, teachers and parents should never forget to consider multilingualism as uniqueness (Canagarajah Citation2016). It is essential to impart these findings to in-service teachers who are already working in heterogeneous classrooms, pre-service teachers who are in training and of course parents who need to have an understanding for the inclusion of pupils with different language abilities. This needs to be addressed more specifically in the in- as well as pre-service teacher training. Within the training teachers need to face their responsibility for promoting the various needs of all learners. The appropriate preparation of teachers should be the overall objective during teacher education.

Limitations

One major limitation – which might fit for a lot of quantitative studies – is that students with a first language other than the language of instruction were rather considered as a homogeneous group within this study. Only their language competencies in the German language were taken into account and more detailed information (e.g. their previous school experiences, culture etc.) was neglected. Therefore, the results of this study are limited to a rather narrow picture and more research –especially with qualitative methods- is needed. The design of this study was also rather experimental (within imagination of a specific child and setting) which leads to the fact that the external validity is rather low. As results from other studies already indicated, the concrete description of a case vignettes can easily cause changes in mean scores. The mean scores should therefore only be interpreted with caution. More information would be needed about concrete settings in teachers’ schools and about circumstances which can explain positive or negative attitudes in the future. With a focus to this study, the investigated predictors (gender, experience, migrant background) were very limited and only represented a rather low amount of variance. Further research therefore is also needed to include other possible explanatory variables. For instance, one variable that could influence differences between groups of teachers is the extent of appropriate training in instructional practices for second language learners. Within the literature focusing the inclusion of students with special educational needs in mainstream classes, it was shown that their lack of (appropriate) training in intensive instructional or classroom management practices was an important variable (Schwab Citation2018).

Conclusion

The present study was designed to examine the actual attitudes of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers and parents towards inclusive education of pupils with different language abilities. Results indicated rather ambivalent attitudes and showed that a significant proportion of parents and in-service teachers think that pupils with lacking German skills should be educated in separate settings. Generally, the results highlighted a need to improve the understanding and openness for cultural diversity, especially for people without migration background. Moreover, the qualification of every person and his or her further integration into the local social and economic life should be the main functions of an education system (OECD Citation2016). Therefore, Austria still needs to move forward to ensure equality in education and promote attitudes towards inclusive education of the persons involved.

Teachers play a certain key role within the successful implementation of inclusive education (Pit-ten Cate et al.Citation2019). Due to this it is important to keep in mind how to further develop teacher education. These days it is crucial to promote teachers’ awareness towards heterogeneity and to increase their responsibility within the inclusion of pupils with different language abilities in different school settings (Jordan Citation2018).

Author contributions

Julia Kast served as primary author, wrote major parts of the manuscript, initiated data analyses and drafted the results section. Susanne Schwab reviewed the results and wrote the discussion section.

Acknowledgements

Data were collected within the course at the University of Vienna, leaded by Susanne Schwab. We specially thank Amina Alagic, Julia Daneczek, Nina Leyer, Christina Popp, Estelle Burger, Stefanie März, Carina Neumann, Dragana Serafimovic, Merve Cihan, Amandine Diederich, Ivona Ilic, Naemi Klinge, Ines Mayr and Jasmin Pauer who collected and entered the data under the supervision of the project team. Very special thanks as well to Tanja Ganotz for her support during the preparation of the questionnaire and the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Julia Kast

Julia Kast is a Ph.D. candidate at the Centre for Teacher Education at the University of Vienna. Her research focus is on inclusive education and her experiences as a primary school teacher fostered a particular interest in equity in the classroom.

Susanne Schwab

Susanne Schwab is Full Professor at the Centre for Teacher Education at the University of Vienna, Austria. As of March 2017, she has also held the position of Extraordinary Professor in the Optentia Research Focus Area at North-West University, South Africa. Her research specifically focuses on inclusive education, as well as teacher education and training.

Notes

1 An adapted version of the Attitudes to Inclusion Scale (AIS; Sharma and Jacobs Citation2016) was used.

2 Adapted version based on preliminary work of de Boer (Citation2012), Schwab et al. (Citation2012) and Schwab (Citation2018).

References

- Aboud, F. E., and M. Amato. 2001. “Developmental and Socialisation Influences on Intergroup Bias.” In Blackwell Handbook of Social Pschology: Intergroup Processes, edited by R. Brown, and S. L. Gaertner, 65–85. Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

- Alghazo, E. M., and E. E. Naggar Gaad. 2004. “General Education Teachers in the United Arab Emirates and Their Acceptance of the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities.” British Journal of Special Education 31 (2): 94–99. doi:10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335.x.

- Ameta, E. S. 2013. “Building Culturally Responsive Family-School Relationships. Boston: Pearson.

- Avramidis, E., P. Bayliss, and R. Burden. 2000. “Student Teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs in the Ordinary School.” Teaching and Teacher Education 16 (3): 277–293. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00062-1.

- BMBWF. 2018. ‟Deutschförderklassen und Deutschförderkurse.” [German language tuition and support classes and German language tuition and support courses]. Accessed 30 January 2019. https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/Themen/schule/schulpraxis/ba/sprabi/dfk.html.

- Braunsteiner, M.-L., C. Fischer, G. Kernbichler, A. Prengel, and D. Wohlhart. 2019. “Erfolgreich Lernen und Unterrichten in Klassen mit Hoher Heterogenität” [Learning and Teaching Successfully in Classes with High Heterogeneity]. In Nationaler Bilungsbericht 2018 [National Education Report 2018], edited by S. Breit, F. Eder, K. Krainer, C. Schreiner, A. Seel, and C. Spiel, 19–62. Salzburg: Bundesinstitut BIFIE.

- Canagarajah, S. 2016. “Crossing Borders, Addressing Diversity.” Language Teaching 49 (3): 438–454. doi:10.1017/S0261444816000069.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Science. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

- Crul, M., J. Schneider, and F. Lelie. 2012. The European Second Generation Compared. Does the Integration Context Matter? Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- De Boer, H., B. Brass, and H. Bruns. 2018. “It’s Sad and Nice at the Same Time”: Challenges to Professionalization in Pedagogical Work with Migrant Children.” In Challenges and Opportunities in Education for Refugees in Europe, edited by F. Dovigo, 1–30. Leiden: Brill.

- De Boer, A., S. J. Pijl, and A. Minnaert. 2011. “Regular Primary Schoolteachers‘ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: a Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (3): 331–353. doi:10.1080/13603110903030089.

- De Boer, A., M. Timmerman, S. J. Pijl, and A. Minnaert. 2012. “The Psychometric Evaluation of a Questionnaire to Measure Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 27 (4): 573–589. doi:10.1007/s10212-011-0096-z.

- Eagly, A. H., and S. Chaiken. 1993. “The Nature of Attitudes.” In The Psychology of Attitudes, edited by A. H. Eagly and S. Chaiken, 1–21. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College.

- Esses, V. M., L. K. Hamilton, and D. Gaucher. 2017. “The Global Refugee Crisis: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications for Improving Public Attitudes and Facilitating Refigee Resettlement.” Special Issues and Policy Review 11 (1): 78–123.

- Forlin, C., T. Loreman, U. Sharma, and C. Earle. 2009. “Demographic Differences in Changing Pre-Service Teachers’ Attitudes, Sentiments and Concerns About Inclusive Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 13 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1080/13603110701365356.

- Gall, M. D., W. R. Borg, and J. P. Gall. 1996. “Research Methods.” In Educational Research: An Introduction, edited by W. R. Borg and D. M. Gall, 165–370. New York: Longman.

- Gee, J. P. 2003. “Opportunity to Learn: A Language-Based Perspective on Assessment.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 10 (1): 27–46. doi:10.1080/09695940301696.

- Gitschthaler, M., J. Kast, R. Corazza, and S. Schwab. 2020. “Resources for Inclusive Education in Austria: An Insight Into the Perception of Teachers.” In International Perspectives on Inclusive Education - Resourcing Inclusive Education, edited by T. Loreman, J. Goldan, and J. Lambrecht (in print). Emerald: Amsterdam.

- Glock, S., and H. Kleen. 2019. “Attitudes Toward Students From Ethnic Minority Groups: The Roles of Preservice Teachers’ own Ethnic Backgrounds and Teacher Efficacy Activation.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 62: 82–91. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.04.010.

- Glock, S., C. Kovacs, and I. Pit-ten Cate. 2018. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Ethnic Minority Students: Effects of Schools’ Cultural Diversity.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 89 (2): 616–634. doi:10.1111/bjep.12248.

- Hecht, P., C. Niedermair, and E. Feyerer. 2016. “Einstellungen und Inklusionsbezogene Selbstwirksamkeitsüberzeugungen von Lehramtsstudierenden und Lehrpersonen im Berufseinstieg – Messverfahren und Befunde aus Einem Mixed-Methods-Design.” [Attitudes and Inclusion-Related Self-Efficacy Believes of pre-Service Teachers and in-Service Teachers in Their Carrier Start – Measurement Methods and Results of a Mixed-Methods Design.].” Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2016 (1): 86–102.

- J. Mintz, P. Hick, Y. Solomon, A. Matziari, F. Ó’Murchú, K. Hall, K. Cahill, C. Curtin, J. Anders, and D. Margariti. 2020. “The Reality of Reality Shock for Inclusion: How Does Teacher Attitude, Perceived Knowledge and Self-efficacy in Relation to Effective Inclusion in the Classroom Change from the Pre-service to Novice Teacher Year?” Teaching and Teacher Education 91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103042.

- Jordan, A. 2018. “The Supporting Effective Teaching Project: 1. Factors Influencing Student Success in Inclusive Elementary Classrooms.” Exceptionality Education International 28: 10–27. Accessed 4 July 2020. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/eei/vol28/iss3/3.

- Norwich, B., and G. Koutsouris. 2017. “Addressing Dilemmas and Tensions in Inclusive Education.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, 1–26. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.154.

- OECD. 2016. “PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education.” PISA, OECD Publishing. Accessed 5 August 2019. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/pisa-2015-results-volume-i_9789264266490-en.

- Paseka, A., and S. Schwab. 2020. ‟Parents’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education and Their Perceptions of Inclusive Teaching Practices and Resources.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 35 (2): 245-272. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1665232..

- Pit-ten Cate, I. M., and S. Glock. 2019. “Teachers’ Implicit Attitudes Toward Students From Different Social Groups: A Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1–18. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02832.

- Pit-ten Cate, I. M., S. Schwab, P. Hecht, and P. Aiello. 2019. “Editorial: Teachers’ Attitudes and Self-Efficacy Beliefs with Regard to Inclusive Education.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 19 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12480.

- Plutzar, V. 2016. “Sprachenlernen nach der Flucht. Überlegungen zu Implikationen der Folgen von Trauma und Flucht für den Deutschunterricht Erwachsener.“ [Learning languages after refuge. Considerations for implications of consequences of trauma and refuge for German lessons for aduts.] In OBST (Osnabrücker Beiträge zur Sprachtheorie), Flucht. Punkt. Sprache, 89, 109–132.

- Schwab, S. 2018. Attitudes Towards Inclusive Schooling. A Study on Students', Teachers’ and Parents'Attitudes. Münster: Waxmann Verlag.

- Schwab, S., M. Gebhardt, E. M. Ederer-Fick, and B. Gasteiger-Klicpera. 2012. “An Examination of Public Opinion in Austria Towards Inclusion. Development of the ‘Attitudes Towards Inclusion Scale’ – ATIS.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 27 (3): 1–17. doi:10.1080/08856257.2012.691231.

- Sharma, U., and K. Jacobs. 2016. “Predicting In-Service Educators’ Intentions to Teach in Inclusive Classrooms in India and Australia.” Teaching and Teacher Education 55: 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2015.12.004.

- Symeonidou, S. 2017. “Initial Teacher Education for Inclusion: A Review of the Literature.” Disability & Society 32 (3): 401–422. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1298992.

- Tabachnick, B., and L. Fidell. 2006. Using Multivariate Statistics. New York: Allyn & Bacon.

- United Nations. 2006. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol.” Accessed 27 May 2019. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf.

- United Nations. 2017. “Sustainable development goals: Quality education.” Accessed 30 June 2020. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/4.pdf.

Appendices

Appendix 1

General Attitudes towards Teaching Pupils with different Abilities in the language of Instruction German in Composite ClassesFootnote1

Adapted AIS scale in comparison with the original AIS version of Sharma and Jacobs (Citation2016).

Appendix 2

Attitudes towards the Inclusion and the Development of Pupils in different Integration SettingsFootnote2

Case descriptions for the teachers’ sample:

Fully included Integration Setting:

‘Imagine yourself teaching in a class with pupils with German as a first language (approx.60-70%) and pupils without German as a first language (approx.30-40%). A new child joins this class and doesn’t speak German as first language and is not able to follow the language of instruction German very well.’

Partly included Integration Setting:

‘Imagine yourself teaching in a class with pupils with German as a first language (approx.60-70%) and pupils without German as a first language (approx.30-40%). Pupils with deficient German language abilities are supported for 6 h in German language tuition and support courses. Otherwise, they are educated in regular classrooms together with the other pupils. A new child joins this class and doesn’t speak German as first language and is not able to follow the language of instruction German very well.’

Fully segregated Setting:

‘Imagine yourself teaching in a German language tuition and support class, exclusively for pupils without German as a first language. Pupils speak different first languages. A new child joins this class and doesn’t speak German as first language and is not able to follow the language of instruction German very well.’

Control Case:

‘Imagine yourself teaching in a class with pupils with German as a first language (approx.60-70%) and pupils without German as a first language (approx.30-40%). A new child joins this class and speaks German as first language and is able to follow the language of instruction German well.’

The case vignettes for the parents’ sample were the same wording except the introductory words: ‘Imagine your child visits a class, where … ’.

To assess the participants’ attitudes the following items were used for each case vignette

Appendix 3

Items in German of the Attitudes towards Inclusion and the Development of Pupils in different Integration Settings

Fully included Integration Setting

‘Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie unterrichten in einer Klasse, in der SchülerInnen mit Deutsch als Erstsprache (ca. 60-70%) und SchülerInnen mit nicht deutscher Erstsprache (ca. 30-40%) unterrichtet werden. In diese Klasse kommt ein neues Kind. Es spricht nicht Deutsch als Erstsprache und kann der Unterrichtssprache Deutsch nicht gut folgen.’

Partly included Integration Setting

‘Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie unterrichten in einer Klasse, in der SchülerInnen mit Deutsch als Erstsprache (ca. 60-70%) und SchülerInnen mit nicht deutscher Erstsprache (ca. 30-40%) unterrichtet werden. SchülerInnen mit mangelhaften/unzureichenden Deutschkenntnissen werden für 6 Schulstunden in Deutschförderkursen gefördert, sonst sind sie gemeinsam mit den anderen SchülerInnen in der Klasse. In diese Klasse kommt ein neues Kind. Es spricht nicht Deutsch als Erstsprache und kann der Unterrichtssprache Deutsch nicht gut folgen.’

Fully segregated Setting

‘Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie unterrichten in einer Deutschförderklasse, in der nur SchülerInnen mit nicht deutscher Erstsprache unterrichtet werden. Die SchülerInnen sprechen unterschiedliche Erstsprachen. In diese Klasse kommt ein neues Kind. Es spricht nicht Deutsch als Erstsprache und kann der Unterrichtssprache Deutsch nicht gut folgen.’

Control Case

‘Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie unterrichten in einer Klasse, in der SchülerInnen mit Deutsch als Erstsprache (ca. 60-70%) und SchülerInnen mit nicht deutscher Erstsprache (ca. 30-40%) unterrichtet werden. In diese Klasse kommt ein neues Kind. Es spricht Deutsch als Erstsprache und kann der Unterrichtssprache Deutsch gut folgen.’

Items in German to assess the participants’ attitudes for each case vignette: