ABSTRACT

This study explores the desired future images of an inclusive school. In its policy documents, Finland has been committed to goals of inclusive education for decades; however, there are still challenges in its implementation. By utilising futures workshops, our research explores the factors envisioned by special education teacher students regarding the desired future of an inclusive school. The factors form three dimensions: structural, social, and emotional. Additionally, certain factors were assessed to fit into more than one dimension, which results in four overlapping aspects of services, commitment, a meaningful school path, and the school’s comprehensive role in the community. Our results emphasise the systemic nature of inclusion in education, which further reinforces the understanding of inclusion as a process.

Introduction

This article explores factors that are considered essential by special education teacher students in their preferred future of an inclusive school. Inclusive education is a universal political goal, as indicated by internationally agreed-upon declarations (UNESCO Citation1994, Citation2000; United Nations Citation1994). Inclusive education involves equal access to education in general and regardless of students’ individual qualities (Rizvi and Lingard Citation2010), and it encompasses the presence, participation, valuing of diversity and achievement of all students in joint environments (Booth Citation2011). However, the tension between the perspectives of policy texts and practical implementations has challenged the development of inclusive education from its inception (Florian Citation1998, 14). The definition of inclusion and the means to achieve it are still under discussion. In our case country, Finland, there has been a critical public discussion (e.g. YLE, Citation18.Citation2.Citation2019) of how to initiate inclusive teaching in practice and whether it actually works equally for all students who need support. Both in Finland and internationally (Hodkinson Citation2010; Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006), the concept of inclusion is contradictory and context dependent. The term is adopted from English, and there is no clear Finnish translation. Furthermore, the perspectives of discussions differ depending on how the concept is understood, which has led to many approaches to implementation.

Changes to education to align with the ideals of inclusive education have proceeded slowly in Finland (Jahnukainen Citation2011). In the 2000s, an increase in the number of children needing special education and substantial variance in the organisation of special education between municipalities prompted special education reform and legislative changes in 2010 (Act Citation642/Citation2010; Ministry of Education Citation2007, 27, 58). This reform shifted the focus to early support and preventive action (Ministry of Education Citation2007). The support for schooling now consists of three stages – general, intensified, and special – instead of the former division to general and special education. The reform reduced state funding for the municipalities responsible for organising education and left the implementation of inclusion vague in national guiding policy texts. Consequently, constraints and factors in promoting inclusion in education relate to the different levels of education policy and delivery.

Comprehensive inclusive educational research has been conducted since the 1990s after the World Conference on Special Education (UNESCO Citation1994) led to the emergence of inclusive education at the international level. This study advances the understanding of the topic from a future-oriented perspective. We understand inclusion to be an endless process of adjusting the education system to meet the needs of all learners within a single system (Booth and Ainscow Citation2002; UNESCO Citation2005). To guide these adjustments, this research investigates the factors that special education teacher students consider important when imagining their preferred future of an inclusive school. By extending beyond problem-oriented discourse while creating alternative visions of the future and assessing their desirability (Amara Citation1981), inclusive environments can be more successfully planned and implemented in education. We are perpetually shaping the future, and our study aims to gain novel insights and deeper comprehension of the factors that are vital to the future of inclusive education. Special education teacher studentsFootnote1 were recruited for this participatory study because they possess essential, up-to-date knowledge about inclusive education as a result of their studies. After their graduation, they will assume a key role in implementing inclusive education, which distinguishes them as especially interesting subjects for exploring the preferred future of inclusive education.

In this article, we first outline the contextual aspects of special education in the Finnish educational system together with the theoretical elements of desired future visions. Then, we explain the empirical materials and methods of our research followed by our results with the reflections of previous studies. Finally, we discuss the implications of this article in addition to suggestions for further research.

Finnish special education policies and practices: past and present

School reforms are influenced by cultural-historical roots. Therefore, this section briefly reviews the history of special education in Finland. The arrangement of special education in Finland reflects public tolerance towards people with disabilities in society. Thus, the arrangement of special education should be viewed as part of society. The development of special education in Finland has progressed through steps that are similar to those of many other countries (see, e.g. Werner-Putnam Citation1979). Around the early twentieth century, the students with special educational needs were marginalised by having their education arranged in separated settings, being released from teaching or forced to repeat a class year (Kivirauma Citation2009). After the Second World War, the provision of special education increased, and various types of special education classes were established to form groups that were as homogenous as possible in segregated environments (Jahnukainen Citation2011).

The shift to the comprehensive school system in the 1970s and beyond entailed a transition towards an ideology of pursuing social equality with integration. Therefore, special education became part of the standardised national education policy (Lintuvuori, Hautamäki, and Jahnukainen Citation2017). Remedial teaching and part-time special education became new sources of support alongside segregated arrangements (Kivirauma Citation2009). Although the new basic education act in 1998 more comprehensively targeted the integration of students with special educational needs into mainstream education (Act Citation628/Citation1998), the vestiges of different eras are still present (Lintuvuori, Hautamäki, and Jahnukainen Citation2017).

Today, the implementation of inclusive education depends largely on the municipality or the school. The Finnish education system is currently mixed; it includes both special schools and classes wherein all of the pupils have special needs and, in parallel, inclusive schools and classes. Pihlaja and Silvennoinen (Citation2020, 54) have noted that, in the Core Curriculum (CC), which is the norm in Finland, the word ‘inclusion’ is mentioned only once: ‘compulsory education should be developed according to inclusive principles’ (CC Citation2014, 18). They found that the CC does not directly define this principle, though it extensively discusses the values associated with inclusive education by emphasising equality, participation and communality. However, one key value of inclusive education is absent: valuing diversity (Pihlaja and Silvennoinen Citation2020).

The present education policy in Finland also reflects a neoliberal ideology (Rizvi and Lingard Citation2010), as policy documents address excellent learning outcomes, individual responsibility, competition, and efficiency. However, the topics of children’s special needs and the possibility of learning ‘less’ have been marginal and almost completely overlooked (Ketovuori and Pihlaja Citation2016). Still, a slight ongoing shift is evident in Finnish education policy. The current Ministry of Education and Culture (Citation2019) has highlighted that children need support at school with an education programme that presents the ‘Right to Learn’ goals. The programme stresses equality, enhanced support, and quality. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen how the new policy ideas will be applied in the schools and municipalities that are responsible for their implementation.

Desired future visions

This study uses a futures study perspective with the specific focus of desired future visions. According to Gidley (Citation1998), when talking about ‘the future’ in everyday discussions, we usually perceive it as a single option. However, we can create alternative images and thoughts of various possible events that we may encounter in the future. One concept for examining alternative futures is that of ‘future images’ (see, e.g. Rubin Citation2013), which refers to the mental representations that are directed to a future state (Nikula, Järvinen, and Laiho Citation2020, 469) and, particular, expectations of the state of things after a certain time (Bell and Mau Citation1971, 23). Future images, together with our expectations and values connected to the future, play an important role in setting goals and choosing the means of promoting them (Rubin and Linturi Citation2001). Future images may be conscious, latent or both, and they might contain contradictory elements that are ‘inconsistent and illogical by nature’ (Rubin Citation2013, 40).

Exploring alternative futures contributes to an understanding of the basis for decision-making (Amara Citation1981). By forming and discussing alternative future images, we can reflect on the desirability of the alternatives and the factors that we need to address to realise the desired future. The concept of ‘vision’ can be used as a reference to a desirable state of affairs in the future (Masini Citation2006; Wiek and Iwaniec Citation2014). Masini (Citation2006) has acknowledged the importance of aspirations of the present for visions of the future. The formation of a vision is a process that calls for the emergence of choice and grounds itself in the belief that change can occur (Masini Citation2006; Wiek and Iwaniec Citation2014). It is a value-driven endeavour, and the aspirations that motivate us must be examined to change reality according to specific models and ideals (Amara Citation1981). Furthermore, when developing a shared vision, that vision should be desirable for the majority of people who are involved. In this process, the elements of shared vision, positivity and normativity are involved in complex interactions with one another (Costanza Citation2000).

Future-oriented studies of inclusion in education have been scarce. Research by Putnam, Spiegel, and Bruininks (Citation1995), which employed the Delphi method, concluded that, at the time, the movement towards inclusion would continue. Their results forecasted education to develop to meet the needs of diverse students, however still considering integration to be grounded in individual needs (Putnam, Spiegel, and Bruininks Citation1995).

Several studies have explored the factors contributing to inclusion. Many scholars (see, e.g. Tomé Fernández Citation2017; Yada, Tolvanen, and Savolainen Citation2018) have suggested that teachers’ positive attitudes and beliefs about inclusion support an effective inclusive school practice. Attention to teachers’ values (Väyrynen and Paksuniemi Citation2020) and epistemological beliefs about knowledge (Jordan, Schwartz, and McGhie-Richmond Citation2009) is crucial prerequisite to achieve inclusion in education. However, inclusion cannot be implemented only through classrooms, as it is linked to many international and national policy documents, the execution of which is shaped by a wide range of contexts and traditions (Magnússon Citation2019).

Our interdisciplinary research is rooted in the fields of education and futures studies. Masini (Citation2006) has suggested that change is embedded in future visions and that the driving forces of the change must be examined to develop the future according to those ideals. Thus, when cultivating an inclusive school, it is imperative to address the essential factors for accomplishing the desired goal.

Methodology

We examined the preferred futures of the inclusive school in three similarly implemented futures workshops in Finland in 2019. Futures workshops, as a form of group work, are deliberative meetings for analysing a focal issue, debating, and designing proposals, visions, or solutions (Nygrén Citation2019). A total of 61 special education teacher students (18% male, and 82% female) participated in the workshops. In Finland, special education teachers in compulsory education hold a higher university degree with studies centred on special education professional studies (60 credits; Decree Citation986/Citation1998, 8a§). The module is retrieved through an application process during the undergraduate period or after graduation with working life experience. This study was implemented during the inclusive pedagogy course. Prior to the workshops, students received lectures and small group teaching on the concepts and ideology of inclusion from multiple perspectives (see, e.g. Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006; Väyrynen Citation2006; Booth Citation2011), and on the service system and legislation from early childhood education to adulthood.

The futures workshop, which was created by Jungk and Müllert (Citation1987) and refined by others (see, e.g. Nygrén Citation2019), was selected as the method. The negative experiences of the present stage of inclusion were viewed not as obstacles but as points of departure for imagining possibilities and exploring new meanings to structure the images of the future. Approximately 20 individuals participated in each of the workshops, which were run in similar phases and instructed by the first author, who actively engaged as a workshop facilitator. Prior to the data collection, the participants received an explanation of the research project. Ethical considerations were also taken into account by obtaining the approval of the institution as well as written consent to the research from participants. Participants worked in heterogeneous groups of four to five people. Each group had students from different backgrounds, including undergraduate students in special education, undergraduate students in class teacher training, class teachers with working life experience and subject teachers with working life experience. Accordingly, the participants varied in age, career stage, and work experience.

The workshop model was customised for this study since the context and participants were unique (Nygrén Citation2019). However, the implementation sought to follow the formula of futures workshop theory and the steps presented by Jungk and Müllert (Citation1987, 49–73). The steps of the workshops were as follows:

Preparatory phase (all together):

Objective: to gain a shared understanding of what we will do together

Action: explaining the aims, and practical aspects of the workshop

Critique phase (in groups):

Objective: to identify present impediments to the implementation of inclusive education as well as reflect on and identify values that guide thinking

Actions: gathering the current problems of an inclusive school and forming a shared understanding of key values in the group

Fantasy phase (in groups):

Objective: to discover desires and expectations for the future of an inclusive school and increase participants’ futures awareness

Actions: imagining a school of the future that preferably implements inclusive teaching and education; encouraging participants to find new ways of thinking without any limitations to approach the familiar topic in a new light and broadly consider the actors and practices of schooling; preventing a dominating role of any members of the group or criticism of the ideas of others during the fantasy phase; producing posters as a tool for groups to compile their ideas and present the output to other groups

Implementation phase (all together):

Objective: to ‘return to reality’ by reviewing concrete proposals of the envisioned ideas

Action: presentations of the groups’ outputs and joint discussion by considering useful ideas to integrate into the current educational system

In addition to the research purposes, an important aim was for participants to learn by finding, valuing and suggesting future opportunities, recognising the existence of different options in the future, increasing their self-confidence and hope for the future, and believing in their own decision-making abilities. The role of the facilitator was to lead and promote the process as part of the interaction, and the research material consisted of the written outputs of the participants as well as the researcher’s complementary field notes.

Data analysis

Since there was no clear or essential theoretical framework for the purpose of the research, we conducted an inductive content analysis (see, e.g. Elo and Kyngäs Citation2008) to capture the complexities of the phenomenon. Because the approach was interpretive, we assigned importance to approach the topic from detailed observations to a broader whole (Mason Citation2002, 150–151). The analysis progressed in phases of gradually increasing depth. First, the material was transcribed from the posters and field notes and read numerous times to become fully acquainted with it. Subsequently, through clustering, the expressions were simplified and coded into subgroups. The abstraction was then performed; on the basis of the classification, we generated umbrella concepts, which were framed as dimensions that depicting the theme from distinct viewpoints.

The analysis was guided by the question of which factors special education teacher students identify as important when imagining their preferred future of an inclusive school. In the analysis process, coding, clustering and abstraction were carried out in several rounds while testing ideas that emerged in the analysis. During this process, some factors in the data were matched with more than one dimension. These factors formed overlapping aspects that were assigned illustrative labels.

Visions of the desirable inclusive school

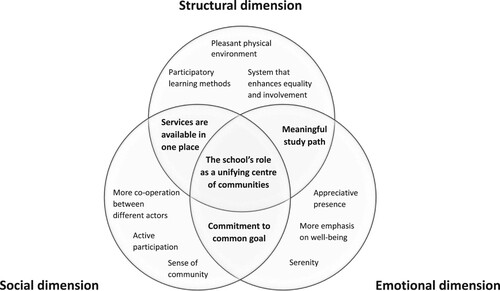

presents the results in terms of three partially overlapping dimensions and the specific factors from which they are formed. The overlapping aspects are expressed in boldface in the centre of the figure. The dimensions consist of the structural, social and emotional dimensions. Each dimension contains three specific factors. The nomination of these factors sought to attentively describe both the content of the classification and the change to the present situation. Because some factors fit into more than one dimension, overlapping aspects were formed. These aspects contain factors from two or all three dimensions; thus, they are not equivalent to specific factors of dimensions but are rather combinations of the factors which were clustered into more than one dimension. For this reason, they are called ‘aspects’ instead of ‘factors’ or ‘dimensions’.

Figure 1. Visions of inclusive school – Three dimensions and the specific factors from which they are formed, together with the overlapping aspects.

The combination of the structural and social dimensions is ‘Services are available in one place’, while that of the social and emotional dimensions is ‘Commitment to a common goal’. Finally, the combination of the emotional and structural dimensions is ‘A meaningful study path’. These aspects describe different levels of schooling. The combination of all three dimensions is entitled ‘The school’s role as a unifying centre of the community’. Descriptions of the preferred vision of an inclusive school involved pupils with and without special educational needs and their families, teachers and staff, the education system, and also other actors in society. The following sections introduce the dimensions and their specific factors with quotations from the data before explaining the overlapping aspects.

Structural dimension

The structural dimension consists of a pleasant physical environment, participatory learning methods, and a system that enhances equality and involvement. This dimension represents practical perspectives that participants identified in regard to necessary structural factors to promote the desired inclusion.

A pleasant physical environment was characterised as healthy and comfortable. In contrast to the present school buildings, participants described the desired future school as more ‘homelike’ or as a multipurpose community centre. There were several possibilities for the preferred physical environment, which would be flexible, take a range of disabilities into account and support every person’s well-being. The ideal physical environment would offer ‘closeness to nature’ (group 2), ‘the opportunity to move around and relax (hammocks, sack chairs, etc.)’ (group 4), ‘modifiable spaces’ (group 7). Facilities were also considered relevant, as the accessibility, comfort, and versatility of the operating environment can enable a broad spectrum of activities and promote participation. Lundahl et al. (Citation2018) have similarly concluded that well-designed, flexible spaces are crucial preconditions to enable positive results in both promoting learning and increasing communication in the higher education context. Nevertheless, such perspective has received only minor attention previous discussions of advancing inclusive education.

The factor of participatory learning methods emphasises that learning must be holistic and organised flexibly to honour the individuality of students and create individual learning paths. The school day would be built upon flexible groups and diverse opportunities for students to engage in experimental learning. Collaboration between students of different ages and peer-learning were viewed as essential forms of learning. Participants envisioned that ‘the basic education can be completed at your own pace’ (group 6) and ‘there is a purpose in working’ (group 1) and ‘doing together’ (group 12). They considered emotional and interaction skills, the arts, and self-awareness to be crucial and possible to pursue via, for instance, action-based learning. This result is particularly interesting given that this perspective has received scarce attention in the context of inclusive education. On the other hand, it may be interpreted as a way to support all students, which previous research has addressed (Väyrynen and Paksuniemi Citation2020).

The factor of a system that enhances equality and involvement concerns all procedures that contribute to inclusion and participation. For example, more adults with various professional backgrounds and roles would be needed to support all the students. Administrations could work in teams, and equitable distribution of resources is preferred. Participants imagined that the ‘school is managed by a team’ (group 9), ‘open and supportive management’ (group 7) and ‘shared resources’ (group 8). Consistent with earlier findings (Woodcock and Woolfson Citation2019), it is imperative to have structural support for successful implementation of an inclusive school. In our study, distributive leadership was considered significant for the development of an inclusive school.

Social dimension

The social dimension consists of increased cooperation between actors, active participation and a sense of community. This dimension must be understood in a broad sense when promoting inclusive education. Collaboration involves several actors who are internal or external to the school. The involvement and action of families and students are vital, as is a sense of community is important in the school’s operating culture, which implies feelings of mutual support and unity and demands that the views of students and their families are heard and valued.

According to the inclusive teacher profile (EADSNE Citation2012), core values include collaboration and teamwork. These elements are also emphasised in the factor of increased cooperation between actors. Besides co-teaching, multidisciplinary work was highlighted, which includes a range of actors, such as teachers, school assistants, school health care personnel, therapists, welfare officers, and actors in the third sector. Sharing knowledge and working in teams were especially preferred, which further supports Väyrynen and Paksuniemi’s (Citation2020) claim that teachers excel by sharing the workload through collaboration. This factor is evident in the mentions of ‘co-teaching and shared expertise’ (group 7), ‘planning together’ (group 11) and ‘work community actors: bringing different services close to the school’ (group 14). This interesting result is consistent with previous literature (Robinson Citation2017) and underlies the need to move away from a culture of working alone in classrooms towards a more collaborative pedagogy. Moreover, the result reveals that an inclusive school requires a wide range of actors as well as more shared responsibility and collaborative problem-solving amongst all the actors in connection with students and their families.

The factor of active participation prioritises active involvement of students in the decision-making of the school. Collaboration with parents was framed as an educational partnership that values the expertise of families. Participants envisioned ‘involving students in the daily planning of the school’ (group 2), where ‘students have the opportunity to influence’ (group 12) and ‘parents and grandparents are involved in the daily life of the school’ (group 13). A concrete activity in one’s community strengthens the sense of meaningfulness and belonging (Raivio and Karjalainen Citation2013). Likewise, the involvement of both students and their families is a contributing factor in the preferred inclusive schooling.

In the factor of a sense of community, the school is perceived as part of its surrounding community. This factor includes community support and shared responsibilities. The participants described the school as ‘a meeting place for families’ (group 5) and a ‘mutually supportive work atmosphere’ (group 12). These results suggest that a school community that shares a sense of community through team spirit and openness has a higher chance of successfully delivering inclusive education. Although the community is implicit in inclusive values (Booth Citation2011), it has not been directly acknowledged in existing studies. However, the feature could be interpreted as belonging to the school climate and culture, which has been highlighted (Tomé Fernández Citation2017). Still, it is important to precisely specify the elements of the culture and atmosphere; in this respect, the current study contributes to previous knowledge.

Emotional dimension

The emotional dimension strongly relates to well-being and presence together with experiences of meaningfulness and competence. It consists of three factors – appreciative presence, serenity and well-being – and is characterised by humanity and a focus on strengths.

In the factor of appreciative presence, the value of student diversity and a respect for their personalities are key elements. This view was seen to come true in the situations of encountering. Participants referred to ‘compassion; positive atmosphere’ (group 11), ‘lots of (hourly) resources to meet families’ (group 2), ‘encountering the student every day’ (group 8) and ‘nothing unequal (e.g. that someone falls into a different group)’ (group 10). In this context, any exclusion was denied. Some groups advocated for removing any concept that signals difference. For example, they argued that the term ‘special class’ and even that of ‘inclusion’ are unnecessary because they are stigmatising. This makes a question whether the concept of inclusion is narrowly understood to involve only the participation of students with special educational needs in mainstream education if the term ‘inclusion’ is condemning. If so, this study supports evidence from prior observations that the concept itself is problematic (Hodkinson Citation2010).

The factor of serenity conveys that the everyday life of the desired inclusive school is unhurried and flexible. Inclusion is supported by a peaceful atmosphere. The participants described ‘serenity’ as offering ‘time for students, e.g. for chatting’ (group 11), ‘time to create a peaceful atmosphere’ (group 15) and ‘flexible school day’ (group 13). Thus, successful inclusion in education would seemingly require more tranquillity and flexibility in the schools’ operating culture. One obstacle in the present day is an overwhelming sense of hurry in society. This phenomenon applies not only to the implementation of inclusion but also, according to the Finnish Evaluation Report of the Curriculum 2014, to the achievement of curriculum content objectives, which is partly hampered by urgency and a lack of joint discussion (Venäläinen et al. Citation2020, 4). Teachers face pressure about what is needed and should be taught in schools (Bateman Citation2012), and there is perhaps excessive emphasis on cognitive aspects. This phenomenon may be one reason for the frequent marginalisation of efforts, such as inclusion, which seek deeply rooted change.

Emphasis on well-being centres on features which increase psychological well-being, such as positivity and a focus on strengths and joy. Relevant remarks highlighted the well-being of teachers, which is enhanced by work supervision, continuous training, and self-development. Participants cited ‘continuous development’ (group 2) and ‘work atmosphere: encouraging, enabling, inspiring – mutually supportive’ (group 12). Professional competence is vital to the realisation of inclusion (EADSNE Citation2012). This view may be intertwined with well-being in that a sense of ability to perform one’s work increases comfort and motivation and, in turn, well-being.

Overlapping aspects

The label of ‘services are available in one place’ indicates that the needs of students and families should be extensively addressed with a wide range of activities. For example, after-school activities and various professionals should be available on school premises to support the students and families. Participants recommended ‘various specialists under one roof’ (group 8) and desired that ‘the school would also be open to students outside of class, in the mornings and afternoons. Then there would be freer action’ (group 10). Such viewpoint dictates that the school’s operating culture should extend beyond only matters of learning and teaching. The desired state of an inclusive school requires structures and working conditions that support collaboration and involvement.

Commitment to a common goal is characterised by efforts towards shared educational responsibility, openness, and respect for individuality, and diversity, wherein all parties are committed to a common approach. Participants encouraged ‘shared educational responsibility’ (group 3) and envisioned that ‘the school staff is passionate about their work and supportive of a common goal. Time will be set aside for a joint discussion.’ (group 10). It is critical to formulate a shared vision in schools that specifies common goals and objectives, especially when promoting inclusion.

The aspect of a meaningful study path conveys that the organisation of learning and teaching should be founded on emotionally significant factors, such as experiencing meaningfulness in one’s learning, individual learning, a holistic perspective for learning, and adults’ support for students. Participants recommended ‘reducing bureaucracy: more time to plan cross-curricular study modules and encounter the student’ (group 9) and ‘more adults supporting individual learning paths’ (group 5). This aspect emphasises equality and the human side of schooling by prioritising the pursuit of well-being over money in the organisation of education.

The school’s role as a unifying centre of the community suggests that the school should not be a separate ‘island’ but rather a community that connects people in a novel way. The participants described it as ‘more than just a school’ (group 10) and as an ‘open wellness centre’ (group 5). From this perspective, a school is not simply a place for teaching and learning – it can also be a key part of the activities of the surrounding community. This viewpoint should be incorporated into efforts to attain the desired future of an inclusive school.

Discussion

This study analyses key factors for the desired future of an inclusive school in terms of three dimensions and four overlapping aspects. Participants expressed a broad understanding of inclusion as a promise of quality education and training for all (Booth Citation2011; Messiou Citation2017). The dimensions reflect the multidimensional reality of the preferred future of inclusive education, which reinforces the notion of inclusion as a process (Azorín and Ainscow Citation2020).

The findings reveal an intriguing conceptualisation of the systemic nature of inclusion in education and related school reforms, as the factors in inclusive education are multileveled and interact in numerous ways. Our results evidence that the preferred future of an inclusive school involves interdependencies whereby structural, social, and emotional dimensions are interlinked. There is a tendency to address issues of inclusion as either problems that individual students or teachers encounter or issues of education policy – thus, as separate, non-connected entities (Moberg Citation2003). The school, as an organisation, influences the students’ experiences of themselves as both learners and individuals. When students enter school, they bring a frame of based on societal phenomena (Baum Citation2002). Thus, at school, students and teachers are connected daily, but there is also a wider network of influences. Societal zeitgeist affects the school institution; if the surrounding society values competition and individual success, it may be challenging for inclusion, which supports disadvantaged individuals, to materialise in the school context. Therefore, inclusive education cannot be viewed as independent of society.

While we are aware of the limitations related to the generalizability of qualitative research and the limitation of the research group to special education teacher students, the findings of this study indicate at least three practical implications. First, the results depart from the traditional notion of a school, including its policies and their implementation. Even though the visions of participants seem to partly reflect the image of inclusion within policy texts, they also present a third image that does not correspond to the views in policy or the current practical implementation of inclusion. A preferred future frames the school as participatory on many levels: the teacher is not alone with one class, and parents and other societal actors have a role that is more active than that of a bystanders.

Second, this work further clarifies the need to reform school structures. Schools need to embrace more open interaction with the surrounding society, but advancing beyond the traditional role of the school requires changes. Inclusion in education combines various stakeholders who need to produce a shared vision and commitment to a common goal to collectively promote an inclusive school in their desired direction. Leadership has an essential role in promoting inclusion (Azorín and Ainscow Citation2020). We complement this finding by suggesting distributed leadership and organised administration teams. Furthermore, the participants in our study referred to a more even distribution of resources. This recommendation does not necessarily entail a constant increase in resources but rather a reconsideration of how and where they are directed.

Third, the desired future of an inclusive school is strongly linked to well-being. Our study recognises the importance of encouraging participation and communality in school environments. Both team spirit in the school and the heavier involvement of the surrounding community in school activities can enhance experiences of relevance and well-being. The sense of urgency, as an ongoing challenge, might be alleviated by focusing on social and emotional factors through, for instance, facilitating collaboration and allotting more time to appreciative encounters. Likewise, in line with Foshay’s curriculum matrix (Citation1991), increased attention to the use of spaces to maximise accessibility and comfort of the physical environment can positively affect people’s well-being and possibilities for participation.

This study provides new insights to inclusion in education by providing viewpoints of futures studies that have been scarce in the field of education. Likewise, futures thinking has not commonly been used in the training of the special education teacher students. The time span, how far to the future the visions are supposed to reach, was not given, but it could have helped some participants with the visioning. In addition, questions designed to facilitate visioning might have laid assumptions embedded and direct thinking in a certain direction. However, the results contain elements that were not mentioned in questions or in the definition of inclusion.

Notably, the term ‘preferred future’ can support alternative understandings of who a situation is desirable for. The same applies to the concept of inclusion. According to Moberg (Citation2003), there are power relationships in discourses of inclusion, which may be used to maintain the prevailing structures. Therefore, in order to gain more insight into the future potential of inclusive schools, a considerable amount of further research should be done with extended stakeholders such as pupils and their families, teachers in-service and leaders, other school staff and health care representatives. It would be also worthwhile to test the relevance of the dimensions developed in this study in real-life contexts to explore how the desired futures can be implemented in practice, and whether our results are comparable to other countries and school systems.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Päivi Pihlaja

MA (Education) and M. Soc. Sc. (Futures studies) Elina Nikula currently works in basic education as special needs education teacher in inclusive unit and has experience on teaching at the University of Turku in special education studies. She is a doctoral candidate in faculty of education. Her main research interest are interdisciplinary focusing on special education, the future images of the young people and the future of education.

PhD, special teacherPäivi Pihlaja is an adjunct professor (docent) at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research interests are related both to early childhood education and special education. Currently, she is leading a research project in which inclusive education and co-teaching are being studied. She is leading EduSteps – longitudinal study, which is part of a large multidisciplinary study and also Toddlers study. In this study social-emotional competence and difficulties are in focus. She has supervised doctoral students and has been teaching at the Universities of Turku and Helsinki in special education studies.

Petri Tapio

Petri Tapio is Professor of Futures Research at Finland Futures Research Centre in the University of Turku, Finland. His specialties include futures research methodology, participatory foresight work and sustainability education. He is currently the leader of the major subject of Futures Studies, comprising of an international Master's degree programme and Doctoral studies provided by the University of Turku. Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches are close to his heart. In addition to dozens of peer-reviewed articles, he is the co-editor of the book ‘Transdisciplinary Sustainability Studies’ (Routledge).

Notes

1 In Finland, to educate as a special teacher is possible for class- and subject teachers who have already a master’s degree and work experience. The other way to educate is to study special education teacher studies at the same time when doing master’s degree either in class teacher education or in special education subject.

References

- Act 628/1998. Perusopetuslaki [Basic Education Act]. 1.8.1998/628.

- Act 642/2010. Laki perusopetuslain muuttamisesta [Act Amending the Basic Education Act]. 24.6.2010/642.

- Ainscow, M., T. Booth, and A. Dyson. 2006. “Inclusion and the Standards Agenda: Negotiating Policy Pressures in England.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 10 (4–5): 295–308.

- Amara, R. 1981. “The Futures Field: Searching for Definitions and Boundaries.” The Futurist, XV(1): 25–29.

- Azorín, C., and M. Ainscow. 2020. “Guiding Schools on Their Journey Towards Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (1): 58–76.

- Bateman, D. 2012. “Transforming Teachers’ Temporalities: Futures in an Australian Classroom.” Futures 44 (1): 14–23.

- Baum, H. S. 2002. “Why School Systems Resist Reform: A Psychoanalytic Perspective.” Human Relations 55 (2): 173–198.

- Bell, W., and J. A. Mau. 1971. “Images of the Future: Theory and Research Strategies.” In The Sociology of the Future: Theory, Cases and Annotated Bibliography, edited by W. Bell, 6–44. New York: Russell Sage.

- Booth, T. 2011. “The Name of the Rose: Inclusive Values Into Action in Teacher Education.” Prospects 41: 303–318.

- Booth, T., and M. Ainscow. 2002. Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools. Bristol: Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education.

- CC. 2014. Opetussuunnitelman perusteet [The National Core Curriculum for Basic Education]. Helsinki: Finnish National Agency for Education. https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/new-national-core-curriculum-basic-education-focus-school.

- Costanza, R. 2000. “Visions Of Alternative (Unpredictable) Futures and Their Use in Policy Analysis.” Conservation Ecology 4: 5–22.

- Decree 986/1998. Asetus opetustoimen henkilöstön kelpoisuusvaatimuksista [Regulation on Teaching Staff]. 14.12.1998/986.

- Elo, S., and H. Kyngäs. 2008. “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62 (1): 107–115.

- European Agency for the Development of Special Needs Education (EADSNE). 2012. Profile of Inclusive Teachers. Odense: EADSNE.

- Florian, L. 1998. “Inclusive Practice: What, Why and How?” In Promoting Inclusive Practice, edited by C. Tilstone, 13–26. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Foshay, A. W. 1991. “The Curriculum Matrix: Transcendence and Mathematics.” Journal of Curriculum and Supervision 6 (4): 277–293.

- Gidley, J. M. 1998. “Prospective Youth Visions Through Imaginative Education.” Futures 30 (5): 395–408.

- Hodkinson, A. 2010. “Inclusive and Special Education in the English Educational System: Historical Perspectives, Recent Developments and Future Challenges.” British Journal of Special Education 37 (2): 61–67.

- Jahnukainen, M. 2011. “Different Strategies, Different Outcomes? The History and Trends of the Inclusive and Special Education in Alberta (Canada) and in Finland.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 55 (5): 489–502.

- Jordan, A., E. Schwartz, and D. McGhie-Richmond. 2009. “Preparing Teachers for Inclusive Classrooms.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25: 535–542.

- Jungk, R., and N. Müllert. 1987. Future Workshops: How to Create Desirable Futures. London: Institute for Social Inventions.

- Ketovuori, H., and P. Pihlaja. 2016. “Inklusiivinen koulutuspolitiikka erityispedagogisin silmin [Inclusive Education Policy with the Eyes of Special Education].” In Koulutuksen tasa-arvon muuttuvat merkitykset [The Changing Meanings of Educational Equality], edited by H. Silvennoinen, M. Kalalahti, and J. Varjo, 159–182. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopistopaino, Kasvatussosiologian vuosikirjaI.

- Kivirauma, J. 2009. “Erityisopetuksen historialliset kehityslinjat [Historical Development Lines of Special Education].” In Erityispedagogiikan perusteet [Basics of Special Education], edited by S. Moberg, J. Hautamäki, J. Kivirauma, U. Lahtinen, H. Savolainen, and S. Vehmas, 25–45. Helsinki: WSOYpro Oy.

- Lintuvuori, M., J. Hautamäki, and M. Jahnukainen. 2017. “Perusopetuksen tuen tarjonnan muutokset 1970–2016 – erityisopetuksesta koulunkäynnin tukeen [Changes in the Provision of Support for Basic Education 1970–2016 – from Special Education to Support for Schooling].” Aika 11 (4): 4–21.

- Lundahl, L., E. Gruffman-Cruse, B. Malmros, A.-C. Sundbaum, and Å Tieva. 2018. “Catching Sight of Students’ Learning: A Matter of Space?” In Core Meets E-LAW: Innovation in Higher Education. Heidelberg.

- Magnússon, G. 2019. “An Amalgam of Ideals – Images of Inclusion in the Salamanca Statement.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (7–8): 677–690.

- Masini, E. 2006. “Rethinking Futures Studies.” Futures 38 (1): 1158–1168.

- Mason, J. 2002. Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. London: Sage publications.

- Messiou, K. 2017. “Research in the Field of Inclusive Education: Time for a Rethink?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (2): 146–159.

- Ministry of Education. 2007. “Erityisopetuksen strategia [Special Education Strategy].” Opetusministeriön Työryhmämuistioita ja Selvityksiä 2007: 47. [Reports of the Ministry of Education, Finland]. Helsinki University Press.

- Ministry of Education and Culture. 2019. Right to Learn Development Programmes. https://minedu.fi/en/qualityprogramme.

- Moberg, S. 2003. “Education for All in the North and the South: Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education in Finland and Zambia.” Education and Training in Development Disabilities 38 (4): 417–428.

- Nikula, E., T. Järvinen, and A. Laiho. 2020. “The Contradictory Role of Technology in Finnish Young People’s Images of Future Schools.” Young 28 (5): 465–484.

- Nygrén, N. 2019. “Scenario Workshops as a Tool for Participatory Planning in a Case of Lake Management.” Futures 107: 29–44.

- Pihlaja, P., and H. Silvennoinen. 2020. “Inkluusio ja koulutuspolitiikka [Inclusion and Education Policy].” In Mahdoton inkluusio? Tunnista haasteet ja mahdollisuudet [Impossible Inclusion? Recognizing the Challenges and Possibilities], edited by M. Takala, A. Äikäs, and S. Lakkala, 45–71. Jyväskylä: PS-kustannus.

- Putnam, J. W., A. N. Spiegel, and R. H. Bruininks. 1995. “Future Directions in Education and Inclusion of Students with Disabilities: A Delphi Investigation.” Exceptional Children 61 (6): 553–576.

- Raivio, H., and J. Karjalainen. 2013. “Osallisuus ei ole keino tai väline, palvelut ovat! [Involvement is Not a Means or an Instrument, Services Are!].” In Osallisuus – oikeutta vai pakkoa? [Involvement – Justice or Coercion?], edited by T. Era, 12–34. Jyväskylän ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisuja 156. Jyväskylä: Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy.

- Rizvi, F., and B. Lingard. 2010. Globalizing Education Policy. London and New York: Routledge.

- Robinson, D. 2017. “Effective Inclusive Teacher Education for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities: Some More Thoughts on the Way Forward.” Teaching and Teacher Education 61: 164–178.

- Rubin, A. 2013. “Hidden, Inconsistent, and Influential: Images of the Future in Changing Times.” Futures 45: S38–S44.

- Rubin, A., and H. Linturi. 2001. “Transition in Making: The Images of the Future in Education and Decision Making.” Futures 33 (3–4): 267–305.

- Tomé Fernández, M. 2017. “Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education and Practical Consequences in Final Year Students of Education Degrees.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 237: 1184–1188.

- UNESCO. 1994. Salamanca Statement and Framework on Action for Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2000. Dakar Framework for Action: Education for All: Meeting our Collective Commitments. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2005. Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000140224. Retrieved 4.1.2020.

- United Nations. 1994. Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities. General Assembly Resolution A/RES/48/96.

- Väyrynen, S. 2006. “Kuka kuuluu mukaan ja mitä arvostetaan? Esimerkki osallistavien ja ei-osallistavien käytänteiden suhteesta suomalaisessa ja eteläafrikkalaisessa koulussa [Who is Involved and What is Valued? An Example of the Relationship Between Inclusive and Non-Inclusive Practices in a Finnish and South African School].” Kasvatus 37 (4): 371–385.

- Väyrynen, S., and M. Paksuniemi. 2020. “Translating Inclusive Values Into Pedagogical Actions.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (2): 147–161.

- Venäläinen, S., J. Saarinen, P. Johnson, H. Cantell, G. Jakobsson, P. Koivisto, M. Routti, et al. 2020. “Näkymiä OPS-matkan varrelta: Esi- ja perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelmien perusteiden 2014 toimeenpanon arviointi [Prospects from CC Journey: Evaluation of the Implementation of the 2014 Criteria for Pre-Primary and Basic Education Curricula].” Julkaisut 5: 2020. Helsinki: Kansallinen koulutuksen arviointikeskus.

- Werner-Putnam, R. 1979. “Special Education – Some Cross-National Comparisons.” Comparative Education 15 (1): 83–98.

- Wiek, A., and D. Iwaniec. 2014. “Quality Criteria for Visions in Sustainability Science.” Sustainable Science 9: 497–512.

- Woodcock, S., and L. M. Woolfson. 2019. “Are Leaders Leading the Way with Inclusion? Teachers’ Perceptions of Systemic Support and Barriers Towards Inclusion.” International Journal of Educational Research 93: 232–242.

- Yada, A., A. Tolvanen, and H. Savolainen. 2018. “Teachers’ Attitudes and Self-Efficacy on Implementing Inclusive Education in Japan and Finland: A Comparative Study Using Multigroup Structural Equation Modelling.” Teaching and Teacher Education 75: 343–355.

- YLE [Finnish National Broadcasting Company]. 2019. Suomi siirsi erityisoppilaat suuriin luokkiin, eivätkä kaikki opettajat pidä muutoksesta: “En ole koskaan ollut näin väsynyt” [Finland Transferred Students with Special Educational Needs to Big Classes, and Not All Teachers Like this Change: “I Have Never Been so Tired Before”]. YLE News. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10644741.