ABSTRACT

Educational reforms fail again and again. One reason for the failure is that educational reform stops just outside the classroom door. During the last 25 years, the dominant educational reform initiatives in the US have operated under the misguided conventional wisdom that the educational system is loosely coupled. With this model in mind, decades of educational reform efforts have focused on tightening the system. Based on empirical results we argue that the educational system is neither loosely or tightly coupled, but bifurcated in that (to borrow a metaphor from geoscience) it is comprised of two tectonic plates. The first plate consists of the state, district and school levels, and the second is the classroom, with a fault line between them. The theory of bifurcated system not only explains why past educational changes have stopped at the classroom door, but also raises the key question of how to bridge the fault line. We propose two principles for school improvement in the bifurcated context. The first principle is to integrate principal and teacher leadership, effectively bridging the fault line in both directions. The second principle is the school renewal process, helping transform the classroom practice by emphasizing implementation integrity rather than fidelity.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to propose a theory to explain why educational reforms fail again and again and advocate for a new approach to improving schools and student achievement in the US context. The article integrates four related sets of empirical studies. After describing the phenomenon of repeated failures of educational reforms and the intractability of school improvement, the first set of empirical studies is introduced to argue that the assumption of ‘loosely coupled’ system (thus the approach to school improvement is to tighten the educational system via standards and accountability assessments) is untenable; rather, the educational system is bifurcated, with state-district-school as one plate and classroom as the other, resulting in a fault line between the school (principal) and the classroom (teachers) and the failure of educational reform initiatives being materialized in the classroom. The second set of empirical studies illustrates that the relationship between the principal and teachers is characterized by the ‘win-win situation,’ rather than ‘zero-sum game’. Therefore, it is feasible to promote the concept of integrated school leadership to bridge the fault line. The third set of empirical studies finds that the construct and practice of learning-centered, integrated school leadership are positively related to student achievement. The fourth set of empirical studies reveals that the construct and practice of school renewal predict not only the current level, but also the growth, of student achievement.

Thus, to bridge the fault line via integrated school leadership, a new school improvement approach – with dual foci on the learning-centered, integrated school leadership as the ‘content’ and school renewal as the ‘process’ – is proposed. This article is a synthesis of the above four related sets of empirical studies, with relevant key results from these empirical studies being presented. The four sets of empirical studies are synthesized for the first time to propose the bifurcation theory and advocate for a new school improvement model with dual foci on both the content of learning-centered, integrated school leadership and the process of school renewal.

The issue of the intractability of school improvement

How to improve our schools has been a perennial question in American education. In his classic piece, ‘Reform Again, Again and Again,’ Cuban (Citation1990) lamented that educational reform had failed repeatedly. In explaining why educational change fails, he moved beyond the argument of lack of rationality and focused on the political and institutional perspectives. Similarly, Sarason’s (Citation1990) book, The Predictable Failure of Educational Change, also noted the predictability of the failure of educational reform, primarily from the cultural perspective. So why is school improvement so difficult?

A common theme of the classic studies on the failure of educational reform is that educational reforms could not get through the classroom door. On this topic, Cohen (Citation1990) has written an insightful essay of why educational change fails called, ‘A Revolution in One Classroom: The Case of Mrs. Oublier.’ (Oublier is a pseudonym based on the French word meaning ‘to forget.’) Cohen studied the teaching practice of Mrs. Oublier, who enthusiastically embraced a new math initiative in the 1980s. She felt she was fluent in the new math language and successful using the new curriculum. However, when Cohen observed her classroom, he found that not much had changed. While her teaching did reflect the new math in many ways (e.g. she adopted the curriculum’s innovative instructional materials and activities), Mrs. Oublier ‘forgot’ about the new math as far as her teaching practice was concerned, treating the new mathematical topics designed to help students make sense of mathematics as though she were teaching the old math curriculum. According to Cohen, she has revised the content, but taught the class ‘in ways that discourage(d) exploration of students’ understanding’ (p. 312), a phenomenon of old wine in a new bottle.

Cohen’s case study was a good example of how difficult it is to change a teacher’s classroom instructional practices, even when teachers are enthusiastic about a new curriculum initiative. In concluding his article, Cohen (Citation1990) identified the essence of the intractability of the school improvement issue as ‘whether federal, state, and district mandates to alter schooling will get past the classroom door’ (p. 3).

One of the most systematic studies that illustrates how difficult it is for educational reform to penetrate through the classroom door was Goodlad and Klein (Citation1975), Looking Behind the Classroom Door. The book was a summary of the data that Goodlad and his research team collected and analyzed while visiting hundreds of classrooms across the country. Goodlad and Klein (Citation1970) first formulated 10 reasonable expectations for classroom instruction based on if the slogans of educational reform were translated into classroom-level practice. For example, one of the expectations was ‘individualized instruction,’ but they did not see much of individualized instruction in classrooms. In fact, to their dismay, Goodlad and his team found that none of these so-called reasonable expectations had been translated into classroom practice.

The issue of the intractability of school improvement continued to be revisited after the seminal work by Goodlad, Cuban, and Cohen. For example, Spillane (Citation1999) demonstrated the complexity in changing teachers’ instructional practices. O’Day (Citation2002) suggested that teachers are inclined to metaphorically and literally ‘close’ the classroom door ‘as a coping strategy that potentially allows them to focus, but it also leads to isolation’ (p. 301). Shen and Ma (Citation2006), using a nationally representative sample of teachers from National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Schools and Staffing Survey, investigated the relationships among the state’s curriculum guidelines, schools’ curriculum and classroom teachers’ instruction and found that the influence of states and schools stopped at the classroom door. More recently, Bryk et al. (Citation2009) noted that teachers tended ‘to determine their own objective and enact instruction accordingly, leading to variation within the same school’ (pp. 264–265).

Therefore, one of the reasons that we ‘reform again, again and again’ – to use the title of Cuban’s (Citation1990) article – is that educational reform agendas have not been translated into classroom practice. This begs the question: Why is it so hard to translate educational reform agendas into classroom practice?

The theory of loose coupling

Weick’s (Citation1976) loose coupling theory has been used to explain the intractability of school improvement. Weick’s seminal paper, ‘Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems,’ defined ‘loose coupling’ as events that are attached to each other to a certain extent, yet each retains its discrete identity. Over the years, several researchers have studied the application of loose coupling in education, notably, Hautala et al. (Citation2018) recent integrative review of the literature. As a result, a general mental model that educational organizations are loosely coupled has emerged and essentially become the consensus model.

There have been a variety of reactions to the loose coupling theory applied to educational systems. One school of thought regards loose coupling as a problem to be solved and is interested in employing approaches to tightening the loose coupling (e.g. Fusarelli, Citation2002; Lutz, Citation1982; Morley & Rassool, Citation2000; Smith & O’Day, Citation1990). The systemic change movement is an example of this approach. Smith & O’Day (Citation1990), for example, regarded ‘fragmented, complex, multi-layered educational policy system in which they (schools) are embedded’ as a ‘fundamental barrier to developing and sustaining successful schools in the USA’ (p. 237). They argued that efforts must be made at the state level in order to target the whole system through an alignment of the intended changes on standards, curriculum, and student tests. By targeting the whole system, the reform efforts could be more consistent and effective. The fundamental assumptions of the systemic change movement are that (a) only systemic reform can tighten the school system and (b) these reform efforts will indeed penetrate all the way down to the classroom level.

Generally speaking, educational reform policies at the federal and state levels in the last 25 years have gone down this path of tightening the loosely coupled system. Clinton’s Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994 started curriculum standards for mathematics and English language arts, among others. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act of 2002 required, based on curriculum standards, state-wide testing and accountability measures for schools, principals, and teachers. Obama’s Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 continued the accountability measures. The strategy in the above reauthorizations of the Elementary and Secondary School Act and ensuing state policies was first to develop, promulgate, and implement curriculum standards. Once the curriculum standards were in place, state-wide testing of student achievement became possible. With the data from state-wide testing, policies were proposed and implemented to hold schools, teachers, principals, and other educators accountable. All of these policy efforts have aimed at tightening the loosely coupled system. As Mason (Citation2001) summarized, the core logic of systemic change is to align a system of standards and instructional guidance at all levels of the educational system, and the alignment is reinforced by accountability measures based on mandatory state-wide standardized testing.

Given the seemingly unsuccessful development and implementation of systemic change, researchers have sought to understand how standards-based policy and practice have played out at the district and school levels and have influenced teaching and learning in the classroom (Mason, Citation2001). Shen and Ma (Citation2006) study used nationally representative school and teacher samples from the NCES Schools and Staffing Survey to investigate ‘how the systemic change theory transpires when it was applied to the technical core of teaching and learning’ (p. 235). They found that, from the states’ guidelines, to the schools’ curriculum, to classroom teachers’ instruction, systemic change was able to penetrate all the way down to the school level, but again stopped just outside the classroom door.

A bifurcated educational system

Empirical studies have continued along this line over the years, testing the relationship between the district and school, and between the school and classroom. As mentioned in the foregoing, Shen and Ma (Citation2006), studying the relationship among the state’s curriculum guidelines, schools’ curriculum and classroom teachers’ instruction, found that state’s curriculum guidelines and schools’ curriculum were tightly aligned and that the influence of states and schools stopped at the classroom door. Most recently, they found that the relationship between the school and the classroom was loose (Shen et al., Citation2017), but the relationship between the district and the school was very tight, particularly in the technical core of schooling (performance standards, establishing curriculum, and teachers’ professional development programs) (Xia et al., Citation2020). The summary of the above empirical findings, all based on multi-level analyses of nationally representative data, suggests that the educational system is not loosely coupled throughout, as previously thought. Instead, the technical core of the educational system is ‘bifurcated’ – with tight coupling from the state level to the district level and to the school level, and loose coupling from the school level to the classroom level. Borrowing a metaphor from geoscience, it appears that the educational system is comprised of two ‘tectonic plates’. One plate includes the state, the district, and the school, and the second plate is the classroom. These two tectonic plates are separated by a ‘fault line’ between them. As documented in previous studies (Bryk et al., Citation2009; Cohen, Citation1990; Goodlad & Klein, Citation1975; O’Day, Citation2002; Shen & Ma, Citation2006; Spillane, Citation1999), ‘the fault line’ is an important reason for the perennial phenomenon of the failure of educational reform because the practices advocated by the reform fail to materialize in the classroom.

The theory of bifurcated systems challenges the conventional wisdom that the educational system is loosely coupled and calls into question the dominant reform agenda for the last 20 years, which advocated tightening the system via curriculum standards, accountability tests, and evaluation as the way to improve the K-12 schools. In other words, one of the major issues in educational policy today is that policy initiatives at the federal and state levels are not consistent with the nature of the educational system. As far as the technical core of the schooling – teaching and learning – is concerned, the schooling system is tightly coupled from the state to the school level, but it becomes loosely coupled where classroom level teaching is concerned. This bifurcation explains the perennial phenomena of ‘teachers closing their classroom doors’ (Goodlad & Klein, Citation1975), ‘reforming again, again, and again’ (Cuban, Citation1990), and the nonevent of ‘revolution in a classroom’ (Cohen, Citation1990).

Classroom door as a fault line and the role of principalship and school leadership

To continue the metaphor of tectonic plates, the theory of bifurcated systems indicates that there is a fault line between the school/principal level, on the one hand, and the classroom level, on the other. Among other implications, the fault line points to the importance of the role of principalship and the concept of integrated school leadership in bridging the fault line.

The role of principal leadership in bridging the fault line between the school and the classroom

There has been much literature on the role of principals. For example, Portin (Citation2004) and Portin and Shen (Citation2005) summarized principals’ roles based on the following observation: Principals remain key individuals as school managers, personnel administrators, problem solvers, boundary spanners, initiators of change, and instructional leaders. While not explicitly stated at the time, embedded in roles such as boundary spanner and instructional leader is the idea that principals must pay attention to bridging the fault line between the school and the classroom. Generally speaking, in both the literature and in practice, this important role of principalship to bridge the two tectonic plates has not been emphasized. Therefore, more attention must be paid to the role principals play in the bifurcated educational system.

The role of integrated school leadership

Given the multiple roles that principals play, they are hailed as ‘super heroes’ (Celio & Havey, Citation2005). However, principals alone cannot bridge the fault line between the school level and the classroom level. Therefore, we need to promote a strengthening of school leadership through the integration of principal and teacher leadership.

In the literature, there is much evidence about the effect of principal leadership (Leithwood & Louis, Citation2011; Leithwood et al., Citation2004; Marzano et al., Citation2005) and teacher leadership on the success of students and schools (Harris & Muijs, Citation2003; Reeves, Citation2008; Wenner & Campbell, Citation2017; York-Barr & Duke, Citation2004; Zepeda et al., Citation2013). However, these theories and models of principal leadership and teacher leadership are developed on separate and distinct tracks, with studies tending to focus on one and ignoring the other. When principal and teacher leadership are treated separately in either research or practice, it is difficult to estimate the interactional effects of principal leadership and teacher leadership (Leithwood & Jantzi, Citation1999; Citation2000). This limitation is not surprising given the classic understanding that the impacts of principal leadership tend to be mediated through teachers, particularly when concerning student achievement (e.g. Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996a; Citation1996b; Citation1998; Leithwood & Jantzi, Citation2000). To date, very rarely has research focused on the integration of principal leadership and teacher leadership, which can be referred to as ‘integrated school leadership.’

Through comprehensive literature Hallinger and Heck (Citation1996a; Citation1996b; Citation1998; Citation2011a; Citation2011b)) developed a typology of leadership effectiveness: (a) the direct-effect model (teachers do not interact with principals), (b) the mediated-effect model (teachers passively mediate principal’s influence), and (c) the reciprocal-effect model (teachers actively interact with principals). Hallinger and Heck (Citation2010) argued both the direct and the mediated effects do not fully capture the leadership effects and suggested reciprocal-effects model to account for the interaction between principal leadership and teacher leadership.

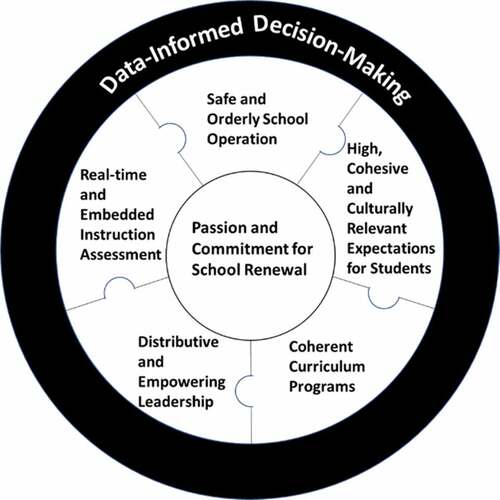

Moreover, given the bifurcated system and the fault line between the school/principal level and the teacher/classroom level, it is more constructive to develop and practice integrated school leadership. Shen and his colleagues conducted an extensive literature review and mapped out the dimensions of integrated school leadership based on comprehensive reviews of literature. From it, they developed a typology of Seven Dimensions of Learning-Centered Leadership to understand integrated school leadership, as well as an instrument to measure it (see and .) (J. Shen & Burt, Citation2015; J. Shen & Cooley, Citation2012; Citation2013; J. Shen et al., Citation2018).

Table 1. Seven dimensions of learning-centered leadership and empirical evidence.

indicates that (a) commitment and passion for school renewal is at the center of learning-centered school leadership, and that (b) data-informed decision-making supports the key substantive dimensions of (c) safe and orderly school operation, (d) high, cohesive, and culturally relevant expectations for all students, (e) distributive and empowering leadership, (f) coherent curriculum, and (g) real-time and embedded instructional assessment. shows the literature base for the seven dimensions of learning-centered school leadership.

These seven dimensions are the integration of principal and teacher leaders because the dimensions encourage principals and teachers to enter each other’s sphere of leadership. Based on the seven-dimension typology of school leadership, J. Shen et al. (Citation2018) developed and validated an instrument that can be used to measure the collective effort of principals and teachers who exercise their own unique leadership to generate integrated school leadership. It is an instrument called ‘Learning-Centered School Leadership,’ which has the above seven dimensions or subscales ( and ). Their empirical research indicates that the instrument has sound psychometric properties, including using the subscales and the whole scale to predict school-level student achievement as measured by the state’s standardized accountability tests (J. Shen et al., Citation2018). In other words, schools that have higher ratings on these dimensions tend to have higher school-level student achievement.

The seven learning-centered leadership dimensions illustrated above are examples of integrated school leadership, a combination of both principal and teacher leadership (J. Shen et al., Citation2018). They illustrated an image of distributive leadership, but with a content focus, i.e. emphasizing those dimensions of work associated with student achievement. They also represented what Cohen (Citation2011) discussed as ‘capacity’ to address the issues associated with fragmented education system. The construct of integrated school leadership includes the elements of, for example, principal’s instructional leadership (Y. L. Goddard et al., Citation2019; R.D Goddard et al., Citation2015) and teacher leadership (Sebastian et al., Citation2016; Citation2017; Shen, Wu, Reeves, Zheng, Ryan, & Anderson, Citation2020). The seven dimensions illustrated above are just examples of integrated school leadership. More indicators of integrated school leadership should be developed based on practice and research.

Integrated leadership as a zero-sum game or a win-win situation?

There are deeply rooted doubts about whether it is ever possible to bridge the fault line by integrating principal and teacher leadership. This is because, in the general leadership arena, there is a philosophical debate on whether leadership is zero-sum or win-win. On the one hand, the zero-sum theory posits that the amount of leadership is finite, and the increase of leadership on the part of one player will necessarily reduce leadership on the other player(s). On the other hand, win-win theory postulates that the amount of leadership is expandable, and the leadership pie can grow. The idea of integrated school leadership, which increases the leadership of both the principal and teachers, would be opposed by those who believe in the zero-sum theory. However, empirical research suggests that the power relationship could indeed be a win-win. Shen and his colleague (J. Shen & Xia, Citation2012; Xia & Shen, Citation2019) used the nationally representative data from the NECS Schools and Staff Survey to study the power relationship between the principal and teachers in seven decision making areas: ‘set performance standards,’ ‘establish curriculum,’ ‘determine content of professional development,’ ‘evaluate teachers,’ ‘hire new full-time teachers,’ ‘set discipline policy,’ and ‘decide how to spend school budget’. Their multiple level modeling indicated that the power relationship between the principal and their teachers was characterized by win-win theory in all decision-making areas, except for the area of ‘evaluating teachers’. This empirical finding supports the idea of integrated school leadership. Integrated school leadership is not a utopian ideal. Rather, it is a practical approach to bridging the fault line between the two bifurcated tectonic plates of the educational system and, ultimately, improving our schools.

Moving toward school renewal: a new approach to school improvement

A second principle for school improvement in the bifurcated educational context is the school renewal process, which emphasizes implementation integrity by placing less emphasis on the accuracy and completeness of applying a program model and more on the internal conditions and external pressures of a given context. This is counter to conventional lines of research and practice that focus on implementation fidelity, which emphasizes the extent to which a project follows a prescribed model (Bond et al., Citation2000). Proponents of implementation fidelity assert that if we ‘faithfully’ carry out the innovations, we will see results. However, given (a) the bifurcated educational system (i.e. the loose coupling between the school level and the classroom level) and (b) the unique ecology of the implementation sites, to ‘faithfully’ carry out prescribed educational innovations becomes a fantasy that has repeatedly resulted in the failure of educational reform.

Scholars (e.g. J. I. Goodlad, Citation1975a; Citation1975b; J. Shen, Citation1999; J. Shen & Burt, Citation2015; Soder, Citation1999) have been advocating for a model of school renewal to initiate and sustain educational change. There has been sustained research and practice on this topic, with contrasts between ‘school reform’ and ‘school renewal’ developed. For J. I. Goodlad (Citation1975a; Citation1975b)) distinguished the research, development, dissemination and evaluation (RDDE) process (associated with school reform) and the dialogue, decision, action and evaluation (DDAE) process (associated with school renewal); Soder (Citation1999) observed that ‘you can tell people what to do [reform], or you can let people determine their purposes and ways to achieve them [renewal]’ (p. 568). The differences between ‘reform’ and ‘renewal’ could be summarized in the following table (J. Shen & Burt, Citation2015, p. 219).

In most studies on program effect, fidelity was measured as a moderator to explain the variation of the program effects across different sites. Carroll et al. (Citation2007) developed a two-facet framework for implementation fidelity: adherence and moderators. Adherence is the bottom-line indicator of implementation fidelity, which includes four elements: content, coverage, frequency, and duration. Four factors or moderators may also influence the degree of fidelity: intervention complexity, facilitation strategies, quality of delivery, and participant responsiveness.

However, Bryk (Citation2016) has indicated that in the social sciences, improvement programs are often designed with high complexity, which involves multiple roles, processes, and tools, as well as interactions among people, and change agents in these improvement programs face a wide range of factors in their organization and local context. In many situations, the program effects are often moderated by these local contextual conditions. Therefore, when designing an improvement program, we must consider what we care about: to know the true effect of our program or to improve a situation using this program. If we emphasize the first purpose, we may care only about the nature of the program itself, while in the latter, we must focus on ‘the implementation demands that the intervention places on local contexts and organizational structures’ (Bryk, Citation2016, para. 4). Under the first purpose or in a situation Bryk (Citation2016) called ‘Simple-Simple’ that the programs are well-defined by explicit sequences of steps and require little changes in broad organizational process, the implementation with fidelity is a right concept to apply. However, in complex situations, ‘successful implementation requires learning how to get this intervention to work reliably in the hands of many different professionals working in varied organizational contexts; it is a problem of local adaptive integration’ (Bryk, Citation2016, para. 9). Thus, in those circumstances, it is more sensible to adopt the idea of implementation integrity.

Implementation integrity puts less emphasis on the accuracy and completeness of applying the program model, and focuses instead on the given internal conditions and external pressures, i.e. what are the most appropriate things to do? That is why the renewal model emphasizes the creative tension between the external and internal influences, a non-linear and vaguely goal-oriented path, implementers as active developers, and the process of dialogue, decision, action and evaluation (J. Shen & Burt, Citation2015). Even though some researchers argued that the adaption of implementation to different sites may comprise the program’s efficacy, the rigid adherence to program procedures is counterproductive to the renewal process (Dane & Schneider, Citation1998). Moreover, J. Shen et al. (Citation2008) suggested that the adaptions promote program fidelity rather than competing with it. Thus, in education settings, the idea of implementation integrity is more reasonable and feasible given the complex local contexts (LeMahieu, Citation2011). Finally, implementation integrity empowers schools, principals, teachers and others to reconceptualize with critical thinking and be creative in developing renewal activities in their unique settings.

One of the issues in improving classrooms is the personal, interpersonal and organizational capacity that exists within the system (Mitchell & Sackney, Citation2011). Given the context of the bifurcation theory, the issue of the capacity at the school level, and particularly at the classroom level, becomes even more prominent. The constructs of bifurcation theory, integrated leadership, and school renewal have three implications for policy, practice and research. First, these constructs provide a perspective that is different from the externally-driven reform model, focuses more on the internal responsiveness, and blurs the lines of teacher leadership and principalship to align and increase the capacity at various levels. Second, these constructs also point to those practices that are consistent with school improvement in the context of the bifurcation theory, integrated leadership and school renewal, such as engaging in (a) working in learning communities according to Mitchell and Sackney (Citation2011) framework (e.g. ‘the construction of knowledge’ in personal capacity, ‘building the team’ in interpersonal capacity, and ‘leadership for learning’ in organizational capacity”), (b) practicing along the dimensions measured in the instrument titled ‘Orientation to School Renewal’ (J. Shen et al., Citation2020), and (c) going outside the school walls to create networked improvement communities (Bryk et al., Citation2010; Chapman, Citation2008; Chapman & Muijs, Citation2014; Wohlstetter et al., Citation2003). Third, more research is needed to promote the practices of integrated leadership and school renewal in the context of the bifurcation theory. Developing and validating practices for integrated leadership and school renewal to enhance the capacity at various levels should continue to be at the core of the school improvement efforts.

Moving into the future: promising evidence

Two groups of promising evidence start to emerge when employing ‘school renewal’ as an approach for school improvement in the context of the theory of bifurcated educational system. The first group of evidence is the positive correlation between the school’s level of renewal activities and student achievement. Working with more than 120 principals and 360 teacher leaders over the years, Shen and his colleagues have gradually distilled the seven dimensions of school renewal (see ). They took one more step and developed and validated an instrument called, ‘Orientation to School Renewal’ (J. Shen et al., Citation2020). Through the validation process, they found that the instrument has good psychometric properties. As to factorial validity, comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.931, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) 0.913, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) 0.037, all indicating good data-model fit. As to reliability, the internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) across the seven factors of school renewal ranged from 0.807 to 0.923 and for the whole instrument 0.974, all above the typical 0.80 cutoff value. Therefore, the mental model of the seven dimensions of school renewal has good factorial validity and reliability, and the seven dimensions of school renewal are supported by the empirical data (J. Shen et al., Citationunder review).

Table 2. School reform model versus school renewal model.

More importantly, Shen and his colleagues went one step further to test the predictive power of the instrument, and found that the ratings on the school renewal instrument, both the subscales and the whole scale, are generally able to predict not only the school’s current student achievement, but also the growth in student achievement on the Michigan Student Test of Educational Progress (M-STEP). In other words, if a school is rated higher in terms of the level of the school renewal efforts as measured by the instrument, the school’s student achievement level tends to be higher and grow more. For example, as to the gain in student achievement, one-unit increase (on the measurement scale of 1 to 6) in school renewal efforts was associated with 4.23 and 2.74 percentage points higher from the prior to the current year in terms of the gain in proportion of students who reached the proficient and advanced categories in mathematics and English language arts, respectively, at the grade level. They also found that the multiple regression models accounted for 65% of the variance in gains in the proportion of students who reached the proficient and advanced categories in mathematics at the grade level and between 62% and 64% of the variance in gains in the proportion of students who reached the proficient and advanced categories in English language arts at the grade level. These percentages were highly substantial, indicating great performance of the multiple regression models in accounting for the variance in gains in the proportion of students who reached the proficient and advanced categories in both mathematics and ELA at the grade level (J. Shen et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the instrument could be used as a tool to guide and monitor the school renewal process, an effort that is effective given the context of the bifurcated system.

The second group of evidence to support the concept of ‘school renewal’ is the actual school improvement that took place in schools. Through the Learning-Centered Leadership Development Program funded by the School Leadership Program of the US Department of Education, 50 schools were engaged in the school renewal process as described in , to develop, implement and evaluate school renewal activities. As a result, evidence of positive effects emerged. First, participating schools reported that the school renewal process helped the development of the renewal activities and that the renewal activities were sustained (Reeves et al., Citation2014). One of the reasons for the sustainability is that the renewal activities were developed together by the principal and teachers to address the unique needs of the school. Second, principal leadership has been statistically significantly improved as measured by (a) Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED) and (b) Data-informed Decision-Making on High-Impact Strategies (DIDM). Comparing with principals in the control group, those in the experimental group improved over a 2.5-year period by 0.52 more on a 5-point scale for VAL-Ed and 0.42 points more on a 4-point scale for DIDM. Both results were statistically significant. Third, the successful school renewal activities and the learning from these cases were documented in eight case studies, with the school as the unit of analysis (J. Shen, Citation2015). The summary across these eight case studies suggested that school renewal activities penetrated classroom doors and improved student learning in these high-needs schools by (a) having integrated school leadership to blur the line between principal and teacher leadership, (b) facilitating teachers’ investment and engagement in initiating and implementing school renewal activities that have implications for classroom instruction, and (c) improving the overall climate of the school, particularly the expectations for teachers and how to meet these expectations (Poppink, Citation2015).

More recently, based on survey data from principals from 2018 and 2020 for a multi-year experimental study project that embodies the constructs of learning-centered, integrated school leadership and school renewal with a focus on literacy, principals in the experimental group reported statistically significantly more growth on two out of three instruments – (a) Principal Leadership and (b) Data-Informed Decision-Making – than their counterparts in the control group, with Hedge’s g (an effect size measure) being 0.90 and 0.43, respectively. Also based on survey data from teachers from 2018 and 2020, teachers in the experimental group reported statistically significantly more growth on all three instruments of (a) Learning-Centered Leadership, (b) Orientation to School Renewal, and (c) Principal Leadership, than their counterparts in the control group, with Hedge’s g being 0.53, 0.50, and 0.22, respectively. Typically, 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 are the thresholds for small, medium, and large effects for Hedge’s g. Based on publicly available school-level, state-accountability achievement data for the panel of ‘the 3rd grade in April 2017, to the 4th grade in April 2018, and to the 5th grade in April 2019,’ schools in the experimental group grew, annually, 2.05 points more than those in the control group in percentage of students who were proficient in English Language Arts, a statistically significant result (J. Shen et al., Citationin progress).

Summary

Educational reforms fail again and again. One major reason for the failure is that educational reform stops at the classroom door. The dominant educational reform initiatives in the last 20 years, have focused on the mechanisms for tightening the loosely coupled educational system. This focused attention on curriculum standards, state-wide accountability testing, and evaluation of the school and educator was based on the misguided conventional wisdom that the educational system is loosely coupled from the state down through to the classroom. Instead, the educational system is a bifurcated system, with the connected space between the state, district and school being one tectonic plate, and the classroom another tectonic plate, with a fault line between the two. The theory of bifurcated systems not only explains why educational reforms stop at the classroom door, but also raises the key issue of how to bridge the fault line between the two tectonic plates.

In the context of the theory of bifurcated system, two principles are proposed for school improvement. The first principle is to integrate principal leadership and teacher leadership to develop and practice the construct of integrated school leadership. One model for the school leadership is the seven dimensions of learning-centered leadership. The second principle is the renewal process that emphasizes implementation integrity, versus the reform model that emphasizes fidelity. Reform stops outside the classroom door, while the renewal process penetrates it, helping to transform classroom instructional practices that increase student achievement. The first principle focuses on the content and the second on process. The combination of these two principles helps bridge the fault line and improve our schools. The improvement of our schools is reflected in not only enhancing learning for all students, but also achieving equity within and between schools for various subgroups of students based on gender, race, language, social economic status, specialized service designations and others.

The empirical bases of the current article – such as (a) the structural nature of the school system (loosely coupled, tightly coupled, or bifurcated), (b) the nature of the relationship between the principal and teachers in various professional domains (a zero-sum game or win-win situation), (c) the seven dimensions of learning-centered, integrated school leadership, and (d) the seven dimensions of school renewal – have been developed solely in the US context, which is a limitation of the current article. Similar studies could be conducted in other countries to investigate, for example, the structural nature of the school system, the nature of the power relationship between the principal and teachers, and leadership constructs and practices based on the findings on the structural nature of the system and the power relationship in the system. The findings from similar studies in other countries could yield insights for school improvement, particularly for how to raise student achievement. A new topic for research – how to improve the relationship between and among various levels of the structure of the educational system to enhance student achievement – appears to emerge. We have much work to do on this topic.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jianping Shen

Dr. Jianping Shen received his Ph.D. in educational leadership and policy studies from the University of Washington in Seattle. He is currently the John E. Sandberg Professor of Education and the Gwen Frostic Endowed Chair in Research and Innovation at Western Michigan University. He published extensively on educational leadership, policy analysis, and research methods.

References

- Allen, N., Grigsby, B., & Peters, M. L. (2015). Does leadership matter? Examining the relationship among transformational leadership, school climate, and student achievement. NCPEA International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 10(2), 1–22. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1083099

- Anderson, S., Leithwood, K., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading data use in schools: Organizational conditions and practices at the school and district levels. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 292–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700761003731492

- Bond, G., Evans, R., Salyers, L., Williams, M., & Kim, P. (2000). Measurement of fidelity in psychiatric rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research, 2(2), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010153020697

- Boykin, A. W., & Cunningham, R. T. (2001). The effects of movement expressiveness in story content and learning context on the analogical reasoning performance of African American children. Journal of Negro Education, 70(1–2), 72–83.

- Bryk, A. S. (2016, March 17). Fidelity of implementation: Is it the right concept? Carnegie Commons Blog https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/blog/fidelity-of-implementation-is-it-the-right-concept/

- Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., & Grunow, A. (2010). Getting ideas into action: Building networked improvement Communities in education. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/spotlight/webinar-bryk-gomez-building-networked-improvement-communities-in-education

- Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. (2009). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

- Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-40

- Celio, M. B., & Havey, J. (2005). Buried treasures: Developing a management guide from mountains of school data. Wallace Foundation.

- Chapman, C. (2008). Towards a framework for school-to-school networking in challenging circumstances. Educational Research, 50(4), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880802499894

- Chapman, C., & Muijs, D. (2014). Does school-to-school collaboration promote school improvement? A study of the impact of school federations on student outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(3), 351–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2013.840319

- Cohen, D. K. (1990). A revolution in one classroom: The case of Mrs. Oublier. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 12(3), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737012003311

- Cohen, D. K. (2011, August 31). Predicaments of reform. Albert Shanker Institute. http://www.shankerinstitute.org/blog/predicaments-reform

- Cotton, K., & Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. (2003). Principals and student achievement: What the research says. ASCD.

- Crum, K. S., & Sherman, W. H. (2008). Facilitating high achievement: High school principals’ reflections on their successful leadership practices. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(5), 562–580. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810895492

- Cuban, L. (1990). Reforming again, again, and again. Educational Researcher, 19(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019001003

- Dane & Schneider. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00043-3

- Day, C., Gu, Q., & Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 221–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X15616863

- Dill, E. M., & Boykin, A. W. (2000). The comparative influence of individual, peer tutoring, and communal learning contexts on the text recall of African American children. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798400026001004

- Dutta, V., & Sahney, S. (2016). School leadership and its impact on student achievement. International Journal of Educational Management, 30(6), 941–958. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-12-2014-0170

- Fusarelli, L. D. (2002). Tightly coupled policy in loosely coupled systems: Institutional capacity and organizational change. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(6), 561–575. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210446045

- Goddard, R. D. (2001). Collective efficacy: A neglected construct in the study of schools and student achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(3), 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.3.467

- Goddard, R. D., Goddard, Y., Kim, E. S., & Miller, R. (2015). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the roles of instructional leadership, teacher collaboration, and collective efficacy beliefs in support of student learning. American Journal of Education, 121(4), 501–530. https://doi.org/10.1086/681925

- Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Hoy, A. W. (2004). Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033003003

- Goddard, Y. L., Goddard, R. D., Bailes, L. P., & Nichols, R. (2019). From school leadership to differentiated instruction a pathway to student learning in schools. Elementary School Journal, 120(2), 198–219. https://doi.org/10.1086/705827

- Goodlad, J. I. (1975a). Schools can make a difference. Educational Leadership, 33, 108–117.

- Goodlad, J. I. (1975b). The uses of alternative views of educational change (The Phi Delta Kappa Meritorious Award Monograph). Phi Delta Kappa.

- Goodlad, J. I., & Klein, M. F. (1970). Behind the classroom door. Charles. A. Jones Pub. Co.

- Goodlad, J. I., & Klein, M. F. (1975). Looking behind the classroom door. Charles. A. Jones Pub. Co.

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1996a). The principal’s role in school effectiveness: An assessment of methodological progress, 1980-1995. In K. Leithwood & P. Hallinger (Eds.), International handbook of educational leadership and administration (pp. 723–783). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1996b). Reassessing the principal’s role in school effectiveness: A review of empirical research, 1980-1995. Educational Administration Quarterly, 32(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X96032001002

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1998). Exploring the principal’s contribution to school effectiveness: 1980-1995. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 9(2), 157–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/0924345980090203

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010). Collaborative leadership and school improvement: Understanding the impact on school capacity and student learning. School Leadership & Management, 30(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632431003663214

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2011a). Conceptual and methodological issues in studying school leadership effects as a reciprocal process. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2011.565777

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2011b). Exploring the journey of school improvement: Classifying and analyzing patterns of change in school improvement processes and learning outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.536322

- Harris, A., & Muijs, D. (2003). Teacher leadership: A review of the research. National College for School Leadership.

- Hautala, T., Helander, J., & Korhonen, V. (2018). Loose and tight coupling in educational organizations – An integrative literature review. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(2), 236–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-03-2017-0027

- Heck, R. H. (1992). Principals’ instructional leadership and school performance: Implications for policy development. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737014001021

- Heck, R. H., & Hallinger, P. (2010). Collaborative leadership effects on school improvement: Integrating unidirectional- and reciprocal- effects models. Elementary School Journal, 111(2), 226–252. https://doi.org/10.1086/656299

- Heck, R. H., & Marcoulides, G. A. (1993). Principal leadership behaviors and school achievement. NASSP Bulletin, 77(553), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263659307755305

- Johnson, P. A. (2013). Effective board leadership: Factors associated with student achievement. Journal of School Leadership, 23(3), 456–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268461302300302

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children. Jossey-Bass.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995a). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995b). But that’s just good teaching? The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1998). Teaching in dangerous times: Culturally relevant approaches to teacher assessment. The Journal of Negro Education, 67(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2668194

- Lee, V., & Smith, J. B. (1996). Collective responsibility for learning and its effects on gains in achievement and engagement for early secondary school students. American Journal of Education, 104(2), 103–147. https://doi.org/10.1086/444122

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (1999). The relative effects of principal and teacher sources of leadership on student engagement with school. Educational Administration Quarterly, 35(5), 679–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X99355002

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2000). Principal and teacher leadership effects: A replication. School Leadership and Management, 20(4), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/713696963

- Leithwood, K., & Louis, K. S. (2011). Linking leadership to student learning (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. University of Minnesota, Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement.

- LeMahieu, P. (2011, October 11). What we need in education is more integrity (and less fidelity) of implementation. Carnegie Commons Blog. https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/blog/what-we-need-in-education-is-more-integrity-and-less-fidelity-of-implementation/

- Louis, K. S., Marks, H. M., & Kruse, S. D. (1996). Teachers’ professional community in restructuring schools. American Journal of Education, 33(4), 757–798. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312033004757

- Lutz, F. W. (1982). Tightening up loose coupling in organizations of higher education. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(4), 653–669. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392536

- Manthey, G. (2006). Collective efficacy: Explaining school achievement. Leadership, 35(3), 23, 36. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ743234

- Marks, H. M., Louis, K. S., & Printy, S. (2000). The capacity for organizational learning: Implications for pedagogy and student achievement. In K. Leithwood (Ed.), Organizational learning and school improvement (pp. 239–266). JAI.

- Marks, H. M., & Louis, K. S. (1997). Does teacher empowerment affect the classroom? The implications of teacher empowerment for instructional practice and student academic performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 19(3), 245–275. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737019003245

- Marks, H. M., & Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 370–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X03253412

- Marzano, R. J., Waters, T., & McNulty, B. A. (2005). School leadership that works. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Mason, S. A. (2001). Turning data into knowledge: Lessons from six Milwaukee public schools. Using data for educational decision making (Newsletter of the Comprehensive Center-Region VI). 6, 3–6, Spring.

- Mitchell, C., & Sackney, L. (2011). Profound improvement: Building learning-community capacity on living-system principles. Routledge.

- Morley, L., & Rassool, N. (2000). School effectiveness: New managerialism, quality and the Japanization of education. Journal of Education Policy, 15(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/026809300285881

- Newmann, F. E., Smith, B., Allensworth, E., & Bryk, A. S. (2001). Instructional program coherence: What it is and why it should guide school improvement policy. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(4), 297–321. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737023004297

- O’Day, J. A. (2002). Complexity, accountability, and school improvement. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 293–329. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.72.3.021q742t8182h238

- O’Donnell, R. J., & White, G. P. (2005). Within the accountability era: Principal instructional leadership behaviors and student achievement. NASSP Bulletin, 89(645), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263650508964505

- Poppink, S. (2015). Lessons from eight schools: Leadership teams and direction from a school renewal activities matrix. In J. Shen & W. Burt (Eds.), Learning-centered school leadership: School renewal in action (pp. 189–207). Peter Lang Publishing.

- Portin, B. (2004). The roles that principals play. Educational Leadership, 61(7), 14–18.

- Portin, B., & Shen, J. (2005). The changing principalship. In J. Shen. (Ed.), School Principals (pp. 179-199). Peter Lang Publishing.

- Pounder, D. G. (1995). Leadership as an organization-wide phenomenon: Its impact on school performance. Educational Administration Quarterly, 31(4), 564–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X9503100404

- Reeves, D. B. (2008). Reframing teacher leadership to improve your school. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Reeves, P., Palmer, L. B., McCrumb, D., & Shen, J. (2014). Sustaining a renewal model for school improvement. In Z. Sanzo (Ed.), From policy to practice: Sustaining innovations in school leadership preparation and development (pp. 282–283). Information Age Publication.

- Sarason, S. (1990). The predictable failure of educational reform: Can we change course before it’s too late? Jossey-Bass.

- Schrum, L., & Levin, B. B. (2013). Leadership for Twenty-First-Century schools and student achievement: Lessons learned from three exemplary cases. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 16(4), 379–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2013.767380

- Sebastian, J., Allensworth, E., & Huang, H. (2016). The role of teacher leadership in how principals influence classroom instruction and student learning. American Journal of Education, 123(1), 69–108. https://doi.org/10.1086/688169

- Sebastian, J., Huang, H., & Allensworth, E. (2017). Examining integrated leadership systems in high schools: Connecting principal and teacher leadership to organizational processes and student outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(3), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1319392

- Sebring, B., & Bryk, A. (2000). School leadership and the bottom line in Chicago. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(6), 440–443. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/school-leadership-and-bottom-line-chicago

- Shatzer, R. H., Caldarella, P., Hallam, P. R., & Brown, B. L. (2014). Comparing the effects of instructional and transformational leadership on student achievement: Implications for practice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(4), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213502192

- Shen, J. (1999). Connecting educational theory, research, and practice: A comprehensive review of John I. Goodlad’s publications. Journal of Thought, 34(4), 25–96.

- Shen, J., & Cooley, V. E. (2012). Learning-centered leadership development program for practicing and aspiring principals. In K. L. Sanzo, S. Myran, & A. H. Nomoore (Eds.), Successful school leadership preparation and development: Lessons learned from US DoE school leadership program grants (pp. 113–135). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Shen, J. (2015). Summaries and reflections: Toward school renewal. In J. Shen & W. L. Burt (Eds.), Learning-centered school leadership: School renewal in action (pp. 209–222). Peter Lang Publishing.

- Shen, J., & Burt, W. (Eds.). (2015). Learning-centered school leadership: School renewal in action. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Shen, J., Cooley, V., Ma, X., Reeves, P., Burt, W., Rainey, J. M., & Yuan, W. (2012). Data-informed decision-making on high-impact strategies: Developing and validating an instrument for Principals. Journal of Experimental Education, 80(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2010.550338

- Shen, J., Cooley, V., Reeves, P., Burt, W., Ryan, L., Rainey, J. M., & Yuan, W. (2010). Using data for decision-making: Perspectives from 16 principals in Michigan, USA. International Review of Education, 56(4), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9172-x

- Shen, J., & Cooley, V. E. (2008). Critical issues in using data for decision-making. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 11(3), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701721839

- Shen, J., & Cooley, V. E. (Eds.). (2013). A resource book for improving principals’ learning-centered leadership. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Shen, J., Gao, X., & Xia, J. (2017). School as a loosely coupled organization? An empirical examination using national SASS 2003-04 data. Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 45(4), 657–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216628533

- Shen, J., & Ma, X. (2006). Does systemic change work? Curricular and instructional practice in the context of systemic change. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5(3), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760600805832

- Shen, J., Ma, X., Cooley, V. E., & Burt, W. L. (2016a). Measuring principals’ data-informed decision-making on high-impact strategies: Validating an instrument used by teachers. Journal of School Leadership, 26(3), 407–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268461602600302

- Shen, J., Ma, X., Cooley, V. E., & Burt, W. L. (2016b). Mediating effects of school process on the relationship between principals’ data-informed decision-making and student achievement. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 19(4), 373–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2014.986208

- Shen, J., Ma, X., Gao, X., Palmer, B., Poppink, S., Burt, W., Leneway, R., McCrumb, D., Pearson, C., Rainey, M., Reeves, P., & Wegenke, G. (2018). Developing and validating an instrument measuring school leadership. Educational Studies, 45(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2018.1446338

- Shen, J., Ma, X., Mansberger, N., Gao, X., Palmer, L. B., Burt, W., Leneway, R., Mccrumb, D., Poppink, S., Reeves, P., & Whitten, E. (2020). Testing the predictive power of an instrument titled “Orientation to School Renewal”. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1749087

- Shen, J., Ma, X., Mansberger, N., Palmer, L. B., Burt, W., Leneway, R., Reeves, P., Poppink, S., McCrumb, D., Whitten, E., & Gao, X. (under review). Developing and validating an instrument measuring school renewal: Testing the factorial validity and reliability.

- Shen, J., Reeves, P., Ma, X., Anderson, D., & Ryan, L. (in progress). Efficacy studies for the High-Impact Leadership for School Renewal Project.

- Shen, J., Wu, H., Reeves, P., Zheng, Y., Ryan, L., & Anderson, D. (2020). The association between teacher leadership and student achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100357

- Shen, J., & Xia, J. (2012). The relationship between teachers’ and principals’ power: Is it a win-win situation or zero-sum game? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 15(2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2011.624643

- Shen, J., Yang, H., Cao, H., & Warfield, C. (2008). The fidelity-adaptation relationship in non-evidence-based programs and its implication for program evaluation. Evaluation, 14(4), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389008095488

- Smith, M. S., & O’Day, J. A. (1990). Systemic school reform. In S. Fuhrman & B. Malen (Eds.), The politics of curriculum and testing (pp. 233–267). The Falmer Press.

- Smith, W., Guarino, A., Strom, P., & Adams, O. (2006). Effective teaching and learning environments and principal self-efficacy. Journal of Research for Educational Leaders, 3(2), 4–23.

- Soder, R. (1999). When words find their meaning: Renewal versus reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(8), 568–570.

- Spillane, J. P. (1999). External reform initiatives and teachers’ efforts to reconstruct their practice: The mediating role of teachers’ zones of enactment. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(2), 143–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/002202799183205

- Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2001). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030003023

- Supovitz, J., Sirinides, P., & May, H. (2010). How principals and peers influence teaching and learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670509353043

- Sweetland, S. R., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). School characteristics and educational outcomes: Toward an organizational model of student achievement in middle schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36(5), 703–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131610021969173

- Tan, C. Y. (2016). Examining school leadership effects on student achievement: The role of contextual challenges and constraints. Cambridge Journal of Education, 25(3), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2016.1221885

- Weick, K. E. (1976). Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391875

- Wenner, J. A., & Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 134–171. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316653478

- Whitt, K., Scheurich, J. J., & Skrla, L. (2015). Understanding superintendents’ self-efficacy influences on instructional leadership and student achievement. Journal of School Leadership, 25(1), 102–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268461502500105

- Witziers, B., Bosker, R. J., & Kruger, M. L. (2003). Educational leadership and student achievement: The elusive search for an association. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39(3), 398–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X03253411

- Wohlstetter, P., Malloy, C., Chau, D., & Polhemus, J. (2003). Improving schools through networks: A new approach to urban school reform. Educational Policy, 17(4), 399–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904803254961

- Xia, J., & Shen, J. (2019). The principal-teacher’s power relationship revisited: A national study based on the 2011-12 SASS data. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2019.1586962

- Xia, J., Sun, J., & Shen, J. (2020). Tight, loose, or decoupling? A National study of the decision-making power relationship between district central offices and school principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(3), 396–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X19851174

- York-Barr, J., & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 255–316. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074003255

- Zepeda, S. J., Mayers, R. S., & Benson, B. N. (2013). The call to teacher leadership. Routledge.