ABSTRACT

This literature review focuses on managerial shared leadership in the education sector, commonly conceptualized as co-principalship. School principals’ difficult work situation, in combination with school leadership being significant for students’ learning, call for organizational solutions where co-principalship can be a part. This review aims to deepen knowledge about co-principalship by focusing on its antecedents and constellation-level outcomes, and their relationship to trust in co-principalship. A secondary aim is to discuss the role of trust theory in empirical co-principalship studies. The promotion of antecedent conditions was found significant for the success of co-principalship. Three types of antecedent were identified: organization-level antecedents, antecedents in relation to staff and others, and constellation-level antecedents. A number of advantages were reported for the sharing principals themselves, including reduced workload and improved work-life balance. The constellation level is where the principals in their interaction continuously build trust, and where either trust or distrust are produced. A variety of both positive and negative outcomes were reported. The empirical literature reviewed was shallow in terms of understanding trust beyond that it is critical for success in co-principalship. Theory-based studies are suggested as a way to deepen understanding of trust content and development with regards to co-principalship.

Introduction

This literature review focuses on managerial shared leadership (MSL) in the education sector, commonly conceptualized as co-principalship. The emphasis is on its antecedents and constellation-level outcomes – particularly their relationship to trust as a vital relationship quality in co-principalship (Döös et al., Citation2018b). The review covers a knowledge gap in bringing together such existing knowledge about co-principalship. In addition to trust being essential for co-principalship, it has relevance for leadership in general including for successful schools (e.g. Tschannen-Moran, Citation2014). Robinson et al. (Citation2009) highlight, with reference to Bryk and Schneider (Citation2002), that leaders’ ability to build relational trust is important for students’ academic achievement.

A problem in school life that motivates this review of co-principalship is the tasks and the work situation of school principals. Principals’ work tasks are described as difficult to handle, even threatening their health and well-being (Beausaert et al., Citation2021). In addition, principals’ leadership is found crucial for effectiveness and pupils’ learning (Böhlmark et al., Citation2012; Huber & Muijs, Citation2010; Leithwood et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2008). This combination of severe challenges and huge importance creates a dilemma where various solutions are, in research and practice, sought for such as distributed leadership (Harris, Citation2013; Leithwood et al., Citation2020), social capital (Beausaert et al., Citation2021) and instructional leadership (Hallinger, Citation2005; Neumerski, Citation2012). The solution to address these challenges, that this paper investigates, is co-principalship as an organizational model. The typical approach for co-principalship studies is to depart from the principals’ difficult work situation and propose co-principalship as a solution (e.g. Eckman, Citation2018; West, Citation1978). There are no previous reviews of co-principalship.

Although research on MSL, including co-principalship, has expanded over the last twenty years (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021) this stream of research has problems in being incorporated into studies by established school leadership researchers. It rather continues to be small and separate from other studies of school leadership and organization with a few notable exceptions (e.g. Gronn, Citation1999; Gronn & Hamilton, Citation2004). Thus, the so called ‘two-person case’ (Pearce & Conger, Citation2003, p. 8) is largely ignored in school research. For example, co-principalship is disregarded in Leithwood et al. (Citation2020) claims about successful school leadership. Whereas widely distributed leadership is regarded as increasingly successful, the co-principalship case is not touched upon despite co-principalship constellations being suggested beneficial and role-modeling for democratic ways of working and the wider distribution of school leadership (e.g. Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2016). Naturally, the co-principalship subset has both similarities and differences compared to the MSL whole. An important difference motivating this review is the legal hindrances that have affected co-principalship in special, to our knowledge in New Zealand (Court, Citation1998, Citation2004a) as well as in Sweden (Döös et al., Citation2018a; Öman, Citation2005; Örnberg, Citation2016). As co-principalship is an existing way of organizing, research based knowledge is important to counteract failure and enhance favorable outcomes.

The next section presents conceptual clarifications and delimitations, followed by the review’s aim and research questions. Thereafter we account for trust as a theoretical construct, methods and findings. Finally, the paper is closed with a discussion ending with conclusions.

Some conceptual clarifications and delimitations

A few concepts need to be clarified here. In this paper, the concepts managerial shared leadership (MSL) and co-principalship are both used. MSL is where two, three or more individuals conjointly work as managers, and it is defined as ‘an organisational phenomenon where a few individuals have and/or take mutual responsibility for the tasks included in holding a managerial position’ (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021, p. 717). They share leadership within the frame of a managerial position and distribute leadership tasks and power within the sharing constellation. In order to differentiate MSL from distributed leadership and from other teams, it should be noted that the sharing here takes place between formally appointed leaders (ibid.). Co-principalship is a subset of MSL, and is by far the most frequently used concept in the education sector. In this review, therefore, the term co-principalship is used when referring to the reviewed papers. When referring to the wider shared leadership context, MSL is used. MSL and co-principalship incorporate both formally equal and non-equal forms (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). However, beyond these formal aspects, co-leaders commonly view themselves as equals (Heenan & Bennis, Citation1999).

The term constellation is used to refer to the co-principal team (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021; Hodgson et al., Citation1965). This avoids confusion with other team types in schools. Hodgson et al. (Citation1965) coined the constellation concept as a way of labeling a tight interrelatedness among sharing individuals; the opposite of this is the loosely structured aggregate. In this paper, constellation-level outcomes refer to outcomes within the co-principal constellation. Besides these outcomes, for the leaders themselves, there are outcomes for the organization and for subordinates. These are not the focus of this review. The term antecedents refers to circumstances that are either enabling factors or necessary preconditions for a well-functioning co-principalship (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021).

Aim and research questions

This review is centered on MSL in the education sector. The aim is to deepen knowledge about co-principalship by focusing on its antecedents and constellation-level outcomes, and their relationship to trust in co-principalship. A secondary aim is to discuss the role of trust theory in empirical co-principalship studies. From these aims come four research questions (RQ):

RQ1:

To what extent and how has co-principalship been studied empirically?

RQ2:

How is trust explicitly treated in the co-principalship papers?

RQ3:

How are antecedents and constellation-level outcomes detailed and seen in the light of trust?

RQ4:

How could trust theory contribute to a deeper understanding of trust in co-principalship studies?

Trust as a theoretical construct

Trust as a theoretical construct separate from the MSL and co-principalship literature is here accounted for, as we will later try to grasp whether using such theory could deepen the understanding of trust as a central relationship quality in co-principalship.

Trust is interpersonal in the sense that it exists between specific individuals. It is understood as a mechanism for the reduction of social complexity (Luhmann, Citation1968) and concerns expectations that may turn into disappointment. Luhmann describes that trust becomes a generalized expectation that the other person will use his freedom to act in line with the personality he made visible as his own. He argues that trust and its opposite mistrust cannot exist simultaneously in a relationship. However, there is domain specific trust (Näslund, Citation2018) indicating that it is for example possible to limit trust to somebody’s ability or competence within a certain area. Furthermore, trust does not only encompass beliefs about the other, it can as well concern the risk of acting on the basis of the other’s experiences (Luhmann, Citation1979). According to Tschannen-Moran (Citation2014), trust paradoxically works both as glue and as a lubricant; it holds things together and reduces friction which makes it easier for an organization to function smoothly. Trust is understood to bind organizational members to one another and ‘schools need trust to foster communication and facilitate efficiency’ (p. 18).

In the trust literature it is common to theorize trust regarding relationships that are formally non-equal (Dietz et al., Citation2006; Kosonen & Ikonen, Citation2022; Macmillan et al., Citation2004; Wilson & Cunliffe, Citation2022), such as between a manager and a staff member or between a leader and followers. This stands in contrast to the symmetrical mutuality and responsibility-taking of MSL and co-principalship.

Defining trust

Dietz et al. (Citation2006) say that the most-quoted definitions of trust can ‘be broken down into three constituent parts: trust as a belief, as a decision, and as an action’ (p. 558). Out of the many definitions of trust (p. 559) they present, the following two were selected for this paper:

The willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party. (Mayer et al., Citation1995)

The extent to which a person is confident in, and willing to act on the basis of, the words, actions and decisions, of another. (McAllister, Citation1995)

The reasons for choosing these definitions in relation to co-principalship are that, in the first (Mayer et al., Citation1995), the two central trust components of expectation and vulnerability are stressed, and in the second (McAllister, Citation1995), the trustor’s willingness to act is mentioned. The latter is highly relevant to principals sharing leadership. Overall, conceptualizing trust is ‘generally considered the expectations of another’s conduct and/or an acceptance of vulnerability’ (Hacker et al., Citation2019, p. 3, authors’ emphasis).

Trust as development process

The definitions above suggest that trust is a mutual quality that may or may not develop in a relationship. It involves risk-taking actions and the development of trust can become stalled or even disrupted. Wilson and Cunliffe (Citation2022) assert that trust develops when ‘both participants increasingly value and respect what each other brings to the relationship’ (p. 2), whereas trust disruption is defined as ‘an event, action, comment, or interaction on the part of either a leader or a follower, that is contrary to the other person’s expectations and causes that person to question and reassess the relationship’ (p. 2). They critique the simplified view of trust as an outcome of relationship development and emphasize that relationship quality, trust, and trusting behaviors are ‘interrelated constituents of an iterative and emergent process of relationship development’ (p. 4).

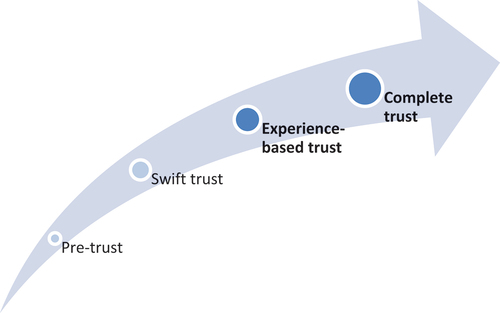

The trust literature generally views trust as taking different forms over time (Dietz et al., Citation2006, as having degrees of intensity (Dietz et al., Citation2006), or as consisting of phases (Macmillan et al., Citation2004). Despite the wordings used, there seems to be agreement that, as the development process proceeds, additional qualities are added where qualitative improvements change and deepen the relationship.

The start of trust building is, for example, conceptualized as calculative trust (Macmillan et al., Citation2004) or as a belief (Dietz et al., Citation2006), which both point to the assumptions parties make in lieu of experience of each other. There is also so-called swift trust, which claims that trust may be built quickly based on surface-level cues rather than interaction or knowledge of the trustee (Hacker et al., Citation2019). Also, initial trust is where trust is not yet based on any kind of experience with, or first-hand knowledge of, the other party. Instead, trust is ‘based on an individual’s disposition to trust or on institutional cues that enable one person to trust another without firsthand knowledge’ (McKnight et al., Citation1998, p. 474).

Further along the trust development process comes ‘an extension of the previous level of trust’ based ‘also on observed practice’ (Macmillan et al., Citation2004, p. 280, with reference to Bottery, 2003). In Dietz and Den Hartog’s paper, this is termed knowledge-based trust, and is regarded as having passed the threshold where real trust begins. Even further along the continuum or trust hierarchy, trust takes place as an action and the relationship quality becomes increasingly effective as relational-based and identification-based trust develop (Dietz et al., Citation2006; Hasel & Grover, Citation2017). Identification-based trust is referred to as complete trust and signifies ‘extremely positive confidence based on converged interests’ (Dietz et al., Citation2006, p. 563). In a similar vein, Macmillan et al. (Citation2004) describe the integrative phase where expectations include what is ethically right, and the identificatory phase at the end of the continuum where trust is based on a ‘complex intertwining of personal thoughts, feelings and values’ (p. 280).

The content of trust

This leads to the issue of the content of trust and what increases when trust is developed as a relationship quality. Various aspects or dimensions are described in the literature and, as most scholars regard trust as a multi-dimensional construct, there are many differing opinions about which dimensions are central when trust is measured (Dietz et al., Citation2006). However, for the purpose of this paper, it is possible to highlight some key themes. For example, it is common to differentiate between cognition-based trust (evident in competence, performance, reliability, dependability) and affective-based trust (relating to emotional issues such as care, concern, integrity, honesty, friendship) (Dietz et al., Citation2006; McAllister, Citation1995; Wilson & Cunliffe, Citation2022). Holste and Fields (Citation2010) differentiate between trust as sharing one’s own experiences with another, and trust as choosing to act upon another’s experiences. Furthermore, Dietz et al. (Citation2006) point out that a classic article by Mayer et al. highlights benevolence, ability/competence and integrity as important qualities of trust, and that powerful arguments later added predictability/reliability. These qualities are very similar to the multidimensional qualities given by Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (Citation2000): benevolence, honesty, openness, reliability and competence.

To conclude this section on the theoretical understandings of trust, Wilson and Cunliffe (Citation2022) are persuasive when asserting that ‘trust and trusting behaviours are embedded in the lived relationships’ (p. 17). Moreover, mutual trust is a sine qua non quality in the bedrock of all successful MSL (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). Wilson and Cunliffe (Citation2022) further argue that trusting relationships are mutable, mutual, complex and idiosyncratic. Hence, the theoretical lens of trust used for this paper is delimited to apply to specific individuals and relationships.Footnote1

Methods

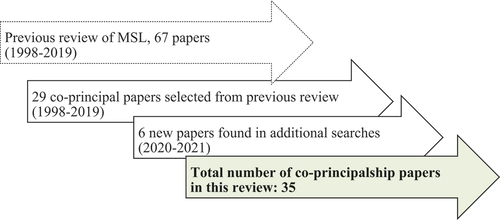

Thirty-five co-principalship papers were included in this review, all of which were empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals. The review was performed in two steps (see ) and this section outlines how. As Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) state, review types ‘despite their different names, share certain essential characteristics, namely, collecting, evaluating and presenting the available research evidence’ (p. 20). Below, we carefully account for what we have done, and how, when carrying out this review. Thus, we first describe the two steps, followed by identification of papers, reading of papers, data collection and registration, and data analysis. Thereafter, in the findings section, the available research evidence is presented. We do not adhere to any specific review type or method.

The two steps

Co-principalship, a subset of MSL, is a research field in which we have worked for many years. Thus, literature searches were carried out both before deciding to prepare this review of co-principalship and in direct relation to the review. The first step behind this review was a review of all empirical studies of MSL that were published in scientific journals (mainly peer-reviewed journals in the English language) (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021); it included 67 studies with sufficient empirical depth (qualitative or quantitative) published during 1998–2019.Footnote2 In the second step we separated all co-principalship papers (29) of the previous review and searched for new co-principalship papers from two additional years (2020–2021); six more papers were added. Thus, the 35 papers here reviewed are all empirical scientific co-principalship papers that were possible to find. The authors own work is included (9 papers).

Identification of papers

Both search steps involved searching for candidate papers and a removal of those papers that, on closer inspection, were not relevant. Reasons for removal were: a) a focus on subjects other than co-principalship, b) not being empirical, and c) having insufficient data quality.

The review work of step 1 started by bringing together publications about managerial shared leadership that had accumulated in our reference library and computer folders over 20 years in the field. Next additional papers were identified checking our digital reference library for other conceptual terms (e.g. dual leadership and co-principalship). Furthermore, new papers were added if found when checking the references in already identified the papers. Toward the end of the identifying process we searched the last three years of ten key journals, i.e. journals in which we had found three or more papers. This search was made on the basis of titles and abstracts, and we found two more papers to read. Finally, we searched the SCOPUS database for articles using the following search terms: managerial shared leadership, shared leadership between managers, shared principalship, dyadic leadership, co-CEO, co-leadership, joint leadership, co-principalship, shared leadership AND manager, dual leadership, and co-principal. We found eleven new papers during this search. In all, our search actions generated 132 papers that we read and we identified 67 as fulfilling the requirements mentioned above (29 were co-principalship papers).

In step 2, papers published in 2020–2021 were searched for, resulting in the addition of six new papers (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2020; Ho et al., Citation2021; Hughes & James, Citation1999; Notman, Citation2020; Wadel, Citation2021)Footnote3 to the 29 co-principalship papers found in step 1. These were mainly found through targeted searches in all 15 education-related journals and a few general leadership journals, in which the papers in the previous review were published. Furthermore, GoogleScholar was searched for co-principal and shared leadership papers from 2020–2021. The reference lists of the reviewed papers were also searched for additional papers. In total, 11 new papers were found, of which five were not relevant as they on a closer look were not about co-principalship.

Reading of papers, data collection and registration

Each author read roughly half of the papers in their entirety and data from the 35 relevant papers were collected in two data matrices (see Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021, p. 719, for more details). Matrix 1 mainly contained basic bibliometric and methodological information as well as conceptual usage. In addition, journal information was created using EndNote software. Matrix 2 aimed at understanding co-principalship and mainly contained structural characteristics as well as antecedents for and outcomes of co-principalship according to each study. There was significant variation in the amount of relevant information to collect from each paper which follows from the fact that the author(s) aim and purpose varied. Common to all the studies was the co-principalship topic and it was possible to identify antecedents and outcomes also for papers that mainly focused on other aspects. Some papers contributed a plethora of antecedents while others did not deal with the issue of antecedents at all. The vast majority of papers (30) identified antecedents that were important for co-principalship to develop and persist. Positive outcomes of co-principalship were described in 25 of the 35 papers, and negative outcomes in 29 papers.

Reading and registering data in the matrices alternated with meetings where we (first and second author) talked through uncertainties, decided which papers to include and corrected the data registered in the matrices when necessary. This adjustment of the data continued until the last round. For the first two reading-meeting rounds, we both read the same papers in order to coordinate our judgments. Finally, the mention of trust was searched for in the papers after having registered the data as above. All mentions of the existence of trust as a theoretical construct or as empirical findings in the papers were collected to enable analysis.

Data analysis

The data collected in the two matrices were treated in different ways depending on the type of column content. Some matrix columns were easily compiled while for example those about the characteristics of the studied managerial sharing constellation(s) required extra attention as several papers studied more than one constellation.

The data collected about antecedents and outcomes were analyzed with thematic content analysis. In these analyses, each theme was treated separately allowing the categorization to emerge from the empirical data. The only exception to this was one category within the antecedent theme that was theoretical and based on previous research about a relational bedrock for MSL (Döös, Citation2015). All the occurrences of each theme were compiled and linked to one of the papers by a number (1–35).

That trust was identified as an essential antecedent for co-principal constellations motivated a closer look at how trust was treated in the papers. It was found that trust was empirically portrayed both as antecedent and outcome. All mentions of trust in the papers were analyzed to separate empirical findings from theory use. Next the theory use was classified as either total absence, referring to a theoretical definition or referring to some research-based understanding of trust. After having collected all empirical mentions of trust these were compiled thematically. The trust theoretical lens described above was used to sharpen our eyes in the search for trust findings in the reviewed papers.

Reflections on method

During the identification of papers in review step 1 we explored the possibility of using the software tool VOSviewer (https://www.vosviewer.com/) to construct and visualize bibliographic connections between the papers. This was not possible since the software required that the papers were selected from a data base, preferably from Web of Science (WoS). A side effect of this trial was realizing that the majority of our selected papers (57 per cent) could not be found in WoS at all. This indicates that our own search actions were important and powerful in finding the relevant literature. For transparency, and to facilitate for future researchers to find and add references all 35 reviewed papers are marked with an asterisk (*) in the reference list.Footnote4

As far as antecedents are concerned, organization-level antecedents and antecedents in relation to staff and others were above included in the findings. This choice was based on the knowledge that these two antecedent types create conditions that influence co-principalship and the work processes in which trust develops. In terms of outcomes, the focus is only on constellation-level outcomes, because it is behind these outcomes that we find the essential interaction where both trust and distrust are produced. This means that the outcomes of co-principalship for the organization and for other organizational members have been left aside and remain to study. Some indications of positive outcomes for the organization have been summarized elsewhere: the principals’ cooperation functioned as a role model, spreading a spirit of cooperation; accessible and confident principals had more time for instructional leadership, enabling them to make better decisions collectively and exert force in crisis handling (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citationin press). It remains to study whether and, if so, how co-principalship would support students’ learning and academic results. Among the reviewed papers, no study had such a focus.

We use education and school as generic labels for what has been studied. The reviewed papers varied in whether they were precise about school level and organizer, several simply referred to ‘school’ while some gave more or less precise information (e.g. ‘small primary school’, ‘secondary school’, ‘compulsory and upper secondary schools’, ‘pre-school’). Several papers did not provide information about type of organizer, while a few stated that both private and public schools were studied. Thus, it is beyond this review’s possibility to be more context specific. To be noted, trust as a prerequisite for successful co-leading is identified for MSL in all kinds of branches (Döös, Citation2015; Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). This said, we have indications from a study of organizational change, where the introduction of MSL into schools and pre-schools was smoother for the pre-schools (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2020). This was understood as a consequence of a culturally favorable context, characterized by greater cooperation. Hence, it could be relevant to address context in future empirical studies.

Findings

First, a brief overview is given of the extent to which co-principalship has been studied empirically and how (RQ1). Bibliometrics, information on methods, and managerial sharing form characteristics are all accounted for. Then, the issue of trust is approached in two ways. The first details whether, and how, trust was explicitly treated in the reviewed co-principalship papers (RQ2). The second details antecedents and constellation-level outcomes, and gives more weight to those that emerge as particularly relevant to the potential for trust development in co-principalship and for the existence and development of trust within sharing constellations (RQ3). Thus, some explicit trust is accounted for, but also more implicit trust through the use of the trust theoretical lens described above, in order to gain a deeper knowledge about how trust emerges as both a development process and as an outcome of co-principalship. Based on the findings below RQ4 is given emphasis in the discussion.

Empirical studies of co-principalship – a brief overview (RQ1)

The review covers studies over a period of 23 years. The first study was published in 1998 (Court, Citation1998) and the most recent in 2021 (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Ho et al., Citation2021; Wadel, Citation2021). Since 1998, the research interest has grown (see ). Thirty-one of the papers were published in the English language, three in Swedish and one in Norwegian.

Table 1. Publishing year of the papers in five-year intervals (35 papers).

The studies were mainly qualitative and predominantly used interviews, but at times they combined observations, documents and a few papers used recorded meetings. Quantitative methods were used in six papers (mainly surveys) and three papers used mixed methods (e.g. a combination of interviews and surveys). The studies were mostly cross-sectional, with the exception of the longitudinal studies by Court (Citation1998, Citation2002, Citation2003, Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2007) and Gronn (Citation1999). Most papers approached co-principalship by focusing on specific sharing constellations of between two and eight people. Duos were the exclusive focus of 24 papers, while nine focused on larger constellations or both duos and larger constellations. The studies were mostly carried out in Europe, Oceania and the US. Three researchers or research groups authored 20 of the 35 papers (57 per cent): Marianne Döös and Lena Wilhelmson with colleagues (Sweden) published nine papers, Marian Court (New Zealand) published six, and Ellen Eckman (U.S.A) published five (twice with a colleague). The bulk of the studies reflected the perspective of the sharing principals themselves (77 per cent).

According to the reviewed papers, co-principalship can either emerge informally between the sharing people themselves or be implemented by the organizational level above, for example through a decision by a board or a superordinate manager. Most papers studied cases in which the sharing principals were equals in the organizational hierarchy. Five papers featured non-equal sharing and five others studied sharing cases of both equals and non-equals.

The papers featured different ways to solve task distribution between the sharing principals. The tasks were either held in common (studied in 14 papers) or divided (12 papers). Five papers focused on both types of case.

Trust as explicitly treated in the reviewed co-principalship papers (RQ2)

This section details how, if at all, trust is explicitly treated in the reviewed papers. Two aspects are dealt with: the extent to which the papers were grounded in trust as a theoretical construct, and how trust was explicitly treated in the empirical findings of the papers. See .

Table 2. Trust in the reviewed papers (35 papers).

The absence of trust theory was striking. Only one paper (Bunnell, Citation2008) defined trust theoretically, referring briefly to it as a four-phase continuum starting on the arrival of a new principal. A few other papers briefly referred to a previous research-based understanding of trust (e.g. Gronn & Hamilton, Citation2004). The absence of theory is particularly interesting in contrast to trust being present in the empirical findings of several studies. Half of the reviewed papers (18) dealt with trust empirically to some extent. Mainly it was trust between the leaders that was studied. Trust in relation to others was touched upon in the studies both when problems had materialized (e.g. Court, Citation2002) and on occasions where the co-principalship served as a role model (e.g. Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2016).

It is somewhat contradictory that the overall contribution about trust at the same time emerges as empirically essential and theoretically shallow. In the following, we present the rather meager findings of trust in the reviewed co-principalship papers. Trust was in a number of studies empirically only described as existing, as an already developed relationship quality essential and critical for success, as an antecedent (e.g. Döös et al., Citation2018b; Gronn & Hamilton, Citation2004; Grubb & Flessa, Citation2006; Notman, Citation2020; Wadel, Citation2021; Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2017). When trust was more explicitly described, it was as part of a necessary foundation or bedrock (e.g. Court, Citation2004a; Döös et al., Citation2018b) and in relation to other interacting constituents of the bedrock, such as shared values (e.g. Döös et al., Citation2018b; Eckman, Citation2006; Hughes & James, Citation1999). The shared values and beliefs were described as a foundation for mutual trust development in successful relationships. Here, loyalty and support were useful, as was a mutual willingness to talk, which took time and required a lot of meetings.

Court (Citation1998, Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2007) described the process of trust development as the building of a foundation for shared leadership, where open and honest communication was essential. If communication stalled, no trust was developed, and distrust might even develop (Court, Citation2003). Moreover, some studies identified that problems and challenges that principals had to handle, became productive situations where trust developed by talking through issues (Eckman, Citation2006, Citation2007; Grubb & Flessa, Citation2006). Furthermore, Döös and Wilhelmson (Citation2019) identified recruitment as a potential starting point for trust development, while Gronn and Hamilton (Citation2004) suggested that new co-principals were likely to be under pressure to establish trust whilst also fulfilling their job demands and adjusting to expectations.

There were only some brief mentions of specific qualities of trust in the reviewed papers. Here some examples illustrate this shallowness. Eckman (Citation2007) asserted that complete trust was required, while Gronn and Hamilton (Citation2004) identified that trust can erode. Court (Citation2004b) reported that no higher level of trust was developed, while Gronn (Citation1999) explained that the whole school was run on trust. Also, trust was mentioned as a feeling of warmth and consideration (Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2017), as mutual dependency (Gronn, Citation1999), and as bringing about confidence in things being done (Döös et al., Citation2018b).

Antecedents and constellation-level outcomes – and their relation to trust (RQ3)

This section details the antecedents and constellation-level outcomes of co-principalship per se, but gives more weight to those that emerge as particularly relevant to trust existence or development. The latter was reached through our use of the trust theoretical lens when analyzing the empirical findings of the reviewed papers.

Three types of antecedent

Three types of antecedent were described in the reviewed papers: organization-level antecedents (20 papers), antecedents in relation to staff and others (11 papers), and constellation-level antecedents (27 papers). The latter antecedents existed within the sharing constellation and were essential as they predict the quality of collaboration and responsibility-taking between the principals. The other two antecedent types played an enabling, enhancing role.

Organization-level antecedents concerned very different matters, here organized into three categories (a–c) that all point to adjustments and decisions the organization can make to facilitate trust and co-principalship (see ).

Table 3. Three categories of organization-level antecedents (20 papers).

The development of a favorable organizational context (category a) concerned good general conditions for shared leadership such as power-sharing organizational practices (Court, Citation2007; Wadel, Citation2021) and a willingness and courage from managerial levels above the co-principalship to explore and lead a non-traditional leadership form (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2020). Categories b and c provided specific preconditions for the sharing constellation’s work processes, through which trust could be developed in close and frequent interaction. Category b dealt with spatial proximity, meaning close offices and office sharing, which gave easy access to one another in the co-principalship constellation (Bunnell, Citation2008; Thomson & Blackmore, Citation2006). With spatial proximity, the frequent, open and honest communication necessary to develop trust could thrive. Furthermore, spatial proximity had a signal value to the organization (Eckman, Citation2018) as it reflected mutual and collective ways of working.

In category c, antecedents could be promoted through relevant recruitment processes (Eckman, Citation2018; Hughes & James, Citation1999; Masters, Citation2013) and the employing authorities could contribute to the process of appointment in various ways. A school organization could work to establish skills in recruitment processes for co-principalship, processes where extra steps were needed. Meetings for a task-solving dilemma as part of the recruitment process might be when the first constellation-related antecedents started to grow trust and to investigate their potential conditions (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2020). Furthermore, unfair salary differences within a sharing constellation hampered possibilities to succeed and threatened trust development (ibid.). The level of compensation needed to be addressed (Eckman & Kelber, Citation2010). It was also important to develop other evaluation processes for co-principals in order not to be measured by a single leader standard (Eckman, Citation2018).

Antecedents in relation to staff and others, such as boards, parents, students/children, worked in two directions. When co-principals acted in certain ways, trust would be created among staff and others, meaning that the leaders emerged as trustworthy. In turn, this became an antecedent that further strengthened the co-principalship. Thus, the constellation’s own work in relation to others could create favorable conditions for the co-principalship, which in turn could be used for transparent and widened decision-making (Court, Citation2002). It was crucial that the sharing leaders created and showed a united front, thereby sending the message of being a team to staff (Eckman, Citation2007, Citation2018) and communicating unity and a professional vision in words and deeds (Notman, Citation2020). It was at times necessary to go behind closed doors and keep talking until arriving at an agreement (Eckman, Citation2007). Subordinates stressed the importance of co-principals making their collaboration visible (Döös et al., Citation2018b) through, for example, jointly led meetings and possibilities for staff to see their principals in frequent dialogue (Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2017).

Constellation-level antecedents focus on the sharing principals and their ways of working. These antecedents emerged as decisive, were brought up in 27 papers, and were mentioned from a variety of angles. Here, they are organized into four categories (a-d) within the constellation (see ).

Table 4. Four categories of constellation-level antecedents (27 papers).

Reciprocal bedrock qualities (category a) within the sharing constellation were described as necessary. The bedrock was a foundation (Court, Citation2004b), a solid relational and value-based platform formed out of mutual trust, reciprocal lack of pretension, and values held in common (Döös, Wilhelmson, et al., Citation2018b). Such relationship qualities were built through everyday interactions (Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2016). The values held in common seemed to be the basis out of which trust and lack of pretension would develop (Notman, Citation2020; Wadel, Citation2021). In successful co-principalship, there was a collective vision for the school (Court, Citation1998) where the leadership was based on shared values and goals, and where the principals shared similar philosophies and core beliefs (Court, Citation2007; Eckman, Citation2006, Citation2007). There was a commitment to a shared ideal and its realization (Gronn, Citation1999) and shared values anchored the relationship (Gronn & Hamilton, Citation2004). Trust was thought to develop over time when co-principals worked closely together and negotiated their expectations of one another (Court, Citation1998) with mutual dependence and synergy (Gronn, Citation1999; Gronn & Hamilton, Citation2004). A lack of pretension grew out of healthy, non-egocentric personalities and high levels of humility (Eckman, Citation2006; Notman, Citation2020). Capable co-principals challenged, interrogated, respected and complemented each other.

Interactive ways of working (category b) were where trust might develop and sustain. A sharing constellation was understood to work in close collaboration and tasks could either be divided or held in common (Aravena & Quiroga, Citation2019; Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2020; Grubb & Flessa, Citation2006). Co-principals stood in for each other, took turns, and rotated roles (Gronn & Hamilton, Citation2004). Frequent open communication and interaction within the constellation was a tool for problem-solving, sorting out conflicts, and promoting shared thinking (Ho et al., Citation2021; Wadel, Citation2021). It was essential to constantly communicate, to talk informally whenever needed as well as at regular meetings. Co-principals thought and talked together, and acted together or apart (Döös et al., Citation2018b). It was important to handle the power balance (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Ho et al., Citation2021), and the ability to let go of control seemed equally important as the sense of shared responsibility for operations through mutually agreed decisions (Eckman, Citation2018; Wadel, Citation2021). When a leadership constellation was larger than three people, it became more difficult to maintain the close communication needed (Döös et al., Citation2017).

Competence differences (category c) within the constellation created synergy through complementary skills and different points of view. Differences could be challenged, negotiated, tolerated, accepted and beneficial (Court, Citation2002; Hughes & James, Citation1999; Notman, Citation2020). The capacity to continuously learn, to force each other to think further, and to moderate each other’s thinking and behaviors created the ability to be prepared and handle change and development (Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2016).

Examples of individual qualities (category d) within the constellation that enhanced co-principalship were: being curious, open-minded, mature, honest, responsive, friendly, loyal, generous, and having integrity (Eckman, Citation2006; Wilhelmson & Döös, Citation2017). Communication skills were important, as was being adaptive and skilled at understanding the ideas and needs of partners. Also, courage and risk-taking capability were important skills for some co-principals (Notman, Citation2020).

Constellation-level outcomes

An outcome may be defined as either an intended result or an unintended consequence (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). The emphasis below is on constellation-level outcomes, i.e. outcomes within the sharing team and for the co-principals themselves (see ). The reason for this choice is that it is behind these outcomes that the interaction was found where trust and distrust were produced.

Table 5. Positive constellation-level outcomes (23 papers) and negative constellation-level outcomes (18 papers).

The positive outcomes for leaders can be seen as potentials that might develop when the bedrock qualities and other favorable antecedents are at hand (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). In the reviewed papers a number of advantages were reported for the co-principals themselves such as reduced workload (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2019), reduced isolation (Wadel, Citation2021), reduced stress (Grubb & Flessa, Citation2006), and reduced conflict with their private life (Eckman & Kelber, Citation2009). Overall, the burdens were more distributed, the demands and troubles more manageable, and the number of meetings and diversity of tasks were reduced. Consequently, co-principals would experience enhanced learning and capability (Döös, Wilhelmson, et al., Citation2018b), an increase in job satisfaction and trust (Eckman & Kelber, Citation2010; Gronn, Citation1999), better collaboration and communication (Cunningham et al., Citation2022; Notman, Citation2020), and improved work-life balance (Eckman, Citation2018).

In contrast, the negative outcomes can be seen as difficulties that may occur when certain antecedents do not exist, and as hindrances for shared leadership to thrive (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). They concerned negative consequences that were described as difficulties, weaknesses and problems related to co-principalship. In the reviewed co-principalship papers constellation-level difficulties resulted from factors such as a lack of co-operation and communication (Court, Citation2003; Cunningham et al., Citation2022), distrust (Court, Citation2004b; Eckman, Citation2006), a lack of common values (Ho et al., Citation2021), a lack of competence (Flessa, Citation2014), conflict between the co-principals (Cunningham et al., Citation2022), problems in handling others (Eckman, Citation2018), excessive workload (Court, Citation2003), task division (Wadel, Citation2021), and a lack of time (Eckman, Citation2018). Constellation-level difficulties contributed to organizational problems and difficulties, as a well-functioning and productive co-principalship required a solid relational bedrock as a foundation. The difficulties could as well lead to an early end of the co-principalship.

Discussion

This review focuses on the stream of research dealing with MSL in the education sector, which is commonly conceptualized as co-principalship. As stated in the introduction it aims to deepen knowledge about co-principalship by focusing on its antecedents and constellation-level outcomes, and their relationship to trust, with a secondary aim to discuss the role of trust theory in empirical co-principalship studies. Below, antecedents and outcomes in relation to the issue of trust in the reviewed papers are discussed followed by a commentary on the role of trust theory (Dietz et al., Citation2006; Macmillan et al., Citation2004; Wilson & Cunliffe, Citation2022) in the reviewed and future co-principalship studies. The paper ends with conclusions including condensed answers to the research questions, identified gaps to address in future research, and briefly, some practical implications.

The picture emerging from the 35 reviewed papers shows that the development or promotion of antecedent conditions was significant for the success of co-principalship. A number of organization-level antecedents pointed to adjustments and decisions that an organization can make to facilitate and support co-principalship as an organizational model. It was about creating a favorable organizational context, offering suitable office solutions for sharing, and developing relevant selection, compensation and evaluation processes. It was also the case that a constellation’s own work in relation to staff, parents, students and subordinates, had the potential to create favorable conditions for co-principalship. The vast majority of the reviewed studies identified constellation-level antecedents that enhanced qualities within the co-principal constellation and its work processes, namely reciprocal bedrock qualities, interactive ways of working, competence differences, and individual qualities. The constellation level was essential, as this was where sharing principals continuously built trust, and where trust was also at risk.

The issue of trust related to antecedents and outcomes

On the basis of the findings we below discuss and provide our interpretations regarding the issue of trust in relation to antecedents and outcomes of co-principalship. In doing this a number of issues of practical relevance are integrated in the reasoning.

Trust is vital for successful MSL, including co-principalship (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). As shown in this paper trust is seldom, if ever, understood as a theoretical construct in studies of co-principalship. This results in a fairly shallow understanding of trust and its development processes and difficulties. As shown in the findings, trust was reported in several empirical parts and portrayed as a central relationship quality within sharing constellations. The literature was thin when it came to understanding trust beyond its importance for the success of co-principalship. Yet, this paper’s closer look at what was said about constellation-level outcomes in the reviewed papers increases knowledge about the existence and development of trust in MSL, and especially in co-principalship. It is important to understand that co-principalship is based on mutual accountability and responsibility for an organization and its results, as this is both a task-based and position-based relationship. This is in contrast to the theorizing of trust in asymmetrical relationships between leaders and staff (Macmillan et al., Citation2004; Wilson & Cunliffe, Citation2022).

Empirically, trust was voiced in the reviewed co-principalship papers as a critical antecedent. Interesting to understand here is the relationship to shared values, another critical antecedent within managerial constellations that share leadership. Shared values are essential for the building of trust, and have previously been found to concern two aspects: the goal and vision of the activity, and how to lead and treat people (e.g. Döös, Citation2015). Our interpretation in relation to trust in the reviewed papers is that shared values were important for determining how to behave and act toward each other within the co-principal constellation, and they also seemed to motivate sharing principals to communicate with each other. Communication was the interaction where trust developed, where experiences (and thus learning) were made about the relationship’s quality and where the trusting relationship continued to develop. Open, honest communication was crucial within the constellation, but also between the constellation and others (board, parents, staff, children/students). From this, it follows that when sharing leaders, early on in their sharing of leadership, refer to time as a hindrance to communication, it is a severe warning and needs to be dealt with, as do other issues pointing to communication deficiencies. Difficulties in developing open communication may result in distrust, painful experiences and the co-principalship being dissolved.

What, then, do the 35 papers have to say about the interaction and learning processes taking place behind trust outcomes of co-principalship? Essentially, that co-principals learned from each other and developed new competencies in their task-based interaction. They forced each other to examine issues from different perspectives, within mixed gender constellations also through different gendered lenses, in thoughtful discussions where they worked out problems and arrived at consensus. On this basis, they took action with confidence and made fewer poor decisions. Thus, differences in opinion gave way to learning conversations, personal development and built a common competence base. In such work processes, competence-bearing relationships (Döös, Citation2007) are constructed. The empirical findings of the reviewed papers showed that it was valuable to have a person to bounce ideas off, to help prepare for difficult parent meetings, or to rehearse coming events together – a person who took equal responsibility for the principal’s assignment. Such conversations, with an equal, supported collaborative planning, joint problem-solving and decision-making, and were useful for instructional leaders as well as for doing the administrative tasks needed in a school organization. The findings also showed that tight co-operation brought about enhanced professional stimulation, joy, security and strength. This interaction is where the trusting relationships of co-principalships are to be found.

What, then, about the processes that take place in the more problematic cases? These were cases where it was difficult or impossible to develop trust, and where swift (Hacker et al., Citation2019) or initial (McKnight et al., Citation1998) trust was in danger. In cases where there was a lack of cooperation, co-principals were not able to agree strategies for collaboration and consequently the co-principalship might rapidly disintegrate. This lack of cooperation was usually related to difficulties with open and honest communication, meaning that co-principals could not establish mutual understandings and agreements and, as a result, distrust would grow. Behind these communication difficulties were competence problems such as insufficient experience and skills for leadership and administrative responsibilities, or lack of management training and skills as instructional leader. When a co-principal was not confident in the competence of the other, conflicts might arise; conflicts that one might try to ignore or hide, but which sooner or later came to the surface. In order to manage others, it was described that co-principals had to present a unified front, otherwise they might be played off against each other by teachers, parents or community. This is where pretension and self-importance created situations where trust was threatened. Hence, there were circumstances where those superordinate to the co-principalship constellation had to step in and solve the situation. In some cases, co-principals had imbalances in workload and problems in determining how to divide tasks and responsibilities; one might be afraid of responsibility for the other’s mistakes, and it could be a challenge for the co-principals to find enough time for the necessary dialogue and joint planning. Certainly, time is necessary for the establishment of trust, and it could be difficult to find while also fulfilling job demands. However, we suggest that lack of time is seldom relevant as a main explanation. Rather, behind the scenes, there is a lack of shared values that motivate communication, and when communication stalls, so does the development of trust.

A commentary on the role of trust theory in reviewed and future co-principalship studies (RQ4)

The issue of trust in empirical studies of MSL could, in principle, range from being theoretically grounded in trust theory, with such theory being used to analyze the trust phenomenon and its content and development processes, to simply stating that trust exists and is important. To some extent, it could be possible to place the papers on a sliding scale: 1) trust treated as a theoretically developed construct used for analysis, 2) support taken from some research-based statement about trust, 3) trust used as an everyday word to describe empirical results, 4) trust not explicitly mentioned (as a word) but similar content implicitly described in the empirical findings, and finally, 5) trust not touched upon at all. The first stage of this scale was not found at all among the 35 reviewed papers, and there were only a few examples of the second stage. The third and fourth stages with explicit or implicit use of trust were common. So the papers neither use nor develop theory of trust in any of the three relevant fields: trust definition, trust development or distortion, and trust content. However, all three seem potentially valuable in furthering knowledge about co-principalship and other kinds of MSL.

In our view, a definition of trust, that emphasizes the expectations of another person and the willingness to render oneself vulnerable (Hacker et al., Citation2019; Mayer et al., Citation1995; McAllister, Citation1995) would be relevant to employ also in empirical studies of co-principalship. The lens of such a definition would allow for deeper findings about how such willingness and vulnerability play out in the co-principals’ development of trust. Also, we suggest more emphasis in a definition of trust on the willingness to act on the basis of somebody else’s competence and on the symmetrical mutuality of sharing constellations that, by definition, have a managerial assignment in common; a mutuality where both parties are both trustors and trustees. Perhaps the following adjusted definition of trust could be useful in future studies of co-principalship and MSL:

The willingness of a close colleague to be vulnerable to the actions of his/her close colleague based on the expectation and experience that the other will act in line with shared values, and the extent to which both are confident in, and willing to act on the basis of, the competence of the other.

The processes behind trust development and trust distortion are important to grow increased knowledge about. In some empirical papers, there were indications of the existence of high stages of trust in the use of terms such as complete trust (Dietz et al., Citation2006) and trust based on the intertwining of personal thoughts, feelings and values (Macmillan et al., Citation2004). Above we have presented work processes that we believe are important in the development of trust in sharing constellations. In contrast to an aggregate, which is loosely structured, a constellation has room for both complementarity and integration, as well as for a tight interplay between the two (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021; Hodgson et al., Citation1965). Thus, the constellation concept points to the tight collaboration and mutual taking of responsibility for tasks that comprise the sharing principals’ assignment. In cases with severe problems between the sharing principals, where no solid bedrock is developed, the intended constellation would move along the continuum toward the aggregate. Here, more studies are needed to confirm, nuance and deepen the knowledge.

The early stages of trust (see ), what we understand as pre-trust and swift trust, are important in the beginning of a co-principalship. More knowledge is needed on how this can be promoted during recruitment and facilitated through the first months of sharing principalship – before reaching the point where real trust begins (Dietz et al., Citation2006), i.e. experience-based trust and complete trust. In our understanding trust development involves an increase in depth and strength and new qualities may grow. Furthermore, we notice a lack of studies about whether and if so how trust can be restored when a transgression occurs that severely harms the relationship. Trust repair is described as any increase in trust above a post-transgression level, while complete repair refers to an increase to the pre-transgression level (Sharma et al., Citation2022). However, following Luhmann (Citation1968) trust and its opposite mistrust cannot exist simultaneously in a relationship. Thus, once trust between co-principals is broken it turns into mistrust. This points to the importance of preventive measures and early support.

In the literature reviewed the content aspects were rather meager. The two aspects identified were to trust each other’s competence and each other as people. In terms of the four aspects (benevolence, ability/competence, integrity and predictability) mentioned by Dietz et al. (Citation2006), studies are needed to determine how these emerge in cases of co-principalship, beyond them being very likely important.

Conclusions for further research and practical implications

Condensed answers to our research questions are here provided, with an eye toward future studies. The amount of co-principalship studies has grown, reaching its peak during the 2016–2020 interval. Yet, there is a looming risk of stagnation unless new angles and themes are developed in future studies. Besides emphasizing trust as an indispensable bedrock quality, this review identifies a lack of depth in the treatment of trust. The qualitative dominance reflects a lack of studies that map the extent of co-principalship. In particular, qualitative process studies of trust and trust development (e.g. as taking place in the everyday task-related interaction and problem solving) are missing as are studies rooted in trust theory. Despite the absence of trust theory in the reviewed papers our use of a trust theoretical lens allowed us to interpret how antecedents and constellation-level outcomes could be seen in the light of trust. We found that trust in co-principalship comes about in the communication and interaction processes of daily leadership work.

Rather than repeating trust as a study finding, future studies are suggested to start out from trust as essential and use trust theory as a theoretical point of departure. This would for instance enable the investigation of trust establishment and how to promote favorable conditions for co-principalships. Thereby valuable knowledge would contribute to practice and enable the development of favorable antecedents and preconditions, at constellation and organization level as well as in national policy and legislative contexts.

The use of trust theory is suggested to contribute to a deeper understanding of trust in future co-principalship studies. Despite what has been conceivable to report about trust from our analysis of the empirical studies in this review the main observation is the absence of trust theory and the following shallow treatment of trust. This causes surprise and leaves much to be explored in future research. The paper offers a revised definition of trust to acknowledge the equality inherent in co-principalship and to the joint responsibility for the assignment. Theories about trust often focus on non-equal relationships, such as between leaders and followers or managers and staff members. When trust is developed between equals (e.g. co-principals), we suggest that a higher degree of mutuality and common responsibility is required for their assignment and the tasks they have in common. Our view is that a growing co-principalship develops in integration with the development of trust between the sharing principals and over time also between the principals and other organizational members. Future studies are needed to deepen the understanding of these processes.

MSL may in general provide organizational solutions where there is an imbalance between demands and resources while managing complex situations (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). The case for co-principalship is a strong one, given the inherent conflict between the need for principals both to be instructional leaders and to complete vast amounts of administrative work. As shown in this review there are a number of advantages reported for the sharing leaders themselves, including reduced workload and improved work-life balance. The question of why co-principalship, with a few exceptions (Gronn, Citation1999; Gronn & Hamilton, Citation2004), goes under the radar in prominent school leadership research remains to be answered. On the one hand, there is the general inability and resistance in society to abandon the hero myth (Örnberg, Citation2016; Schweiger et al., Citation2020); on the other hand, and in the eyes of leadership researchers within the frame of shared and distributed theory, MSL might be of less interest as being rooted in traditional vertical organizations’ appointment of managers (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021). Researchwise, value is potentially added would it awaken school leadership researchers’ interest in the co-principalship field.

In practice, the review adds value to principals and educational organizers engaged in different forms of co-principalship. This is particularly relevant given that co-principalship in both New Zealand and Sweden has faced legal obstacles (Court, Citation1998, Citation2004a; Döös et al., Citation2018a; Örnberg, Citation2016), partly due to uninformed notions of leadership among legislators. For shared leaders it is important to make their cooperation visible to staff. Well-functioning task-based interaction and problem solving bring about competence-bearing relationships of use in crisis handling. For managers overseeing co-principalship arrangements there is a severe warning to deal with if co-principals early on in their sharing of leadership, refer to time as a hindrance to communication. Difficulties in establishing open communication can lead to distrust, painful experiences and the co-principalship being dissolved. The proposed trust growth illustration () can help identify early relationship problems, and guide interventions to ease trust development in co-principalships. Since trust is delicate and easily damaged, it is crucial to understand how sharing principals themselves as well as their surrounding organization can enhance positive antecedents. We have pointed to several adjustments and decisions that organizations can make to facilitate trust in co-principalships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianne Döös

Marianne Döös is Professor Emeritus and a senior researcher in Organisational Pedagogy at Department of Education, Stockholm University, Sweden. Her research deals with the processes of experiential learning in contemporary settings. Topical issues concern managerial shared leadership and interaction as carrier of competence in relationships.

Lena Wilhelmson

Lena Wilhelmson is Associate Professor in Organisational Pedagogy at Department of Education, Stockholm University, Sweden. Studies have been conducted concerning: dialogue and learning, learning processes in organisational renewal work, shared leadership and learning-oriented leadership.

Notes

1. For more collective interpretations, see for example system trust (Luhmann, Citation1968) or non-personal trust (Näslund, Citation2018).

2. The search period was 1965–2019 and 1998 was the first year when a paper was published.

3. Cunningham et al. (Citation2022) was first published online 2021. The paper by Hughes and James (Citation1999) should have been included in the previous review (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2021) had it been found in step 1.

4. All but three (Hewitt et al., Citation2012; Madestam, Citation2017; Marks, Citation2013) are directly referred to in the text.

References

- *Aravena, F., & Quiroga, M. (2019). Bicephalous leadership structure: An exploratory study in Chile. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 22(6), 670–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1492022

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Beausaert, S., Froehlich, D. E., Riley, P., & Gallant, A. (2021). What about school principals’ well-being? The role of social capital. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(2), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143221991853

- Böhlmark, A., Grönqvist, E., & Vlachos, J. (2012). The headmaster ritual: The importance of management for school outcomes ( Working paper 2012:16). The Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy (IFAU).

- Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Rusell Sage Foundation.

- *Bunnell, T. (2008). The Yew Chung model of dual culture co-principalship: A unique form of distributed leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 11(2), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701721813

- *Court, M. R. (1998). Women challenging managerialism: Devolution dilemmas in the establishment of co-principalships in primary schools in Aotearoa/New Zealand. School Leadership & Management, 18(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632439869763

- *Court, M. R. (2002). “Here there is no boss”?: Alternatives to the lone(ly) principal. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (3), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0729

- *Court, M. R. (2003). Towards democratic leadership. Co-principal initiatives. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 6(2), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120304823

- *Court, M. R. (2004a). Talking back to new public management versions of accountability in education: A co-principalship’s practices of mutual responsibility. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 32(2), 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143204041883

- *Court, M. R. (2004b). Using narrative and discourse analysis in researching co-principalships. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 17(5), 579–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839042000253612

- *Court, M. R. (2007). Changing and/or reinscribing gendered discourses of team leadership in education?. Gender and Education, 19(5), 607–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701535642

- *Cunningham, C., Zhang, W., Streipe, M., & Rhodes, D. (2022). Dual leadership in Chinese schools challenges executive principalships as best fit for 21st century educational development. International Journal of Educational Development, 89(March). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102531

- Dietz, G., Den Hartog, D. N., & Sanders, K. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35(5), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610682299

- Döös, M. (2007). Organizational learning. Competence-bearing relations and breakdowns of workplace relatonics. In L. Farell & T. Fenwick (Eds.), World year book of education 2007. Educating the global workforce. Knowledge, knowledge work and knowledge workers (pp. 141–153). Routledge.

- Döös, M. (2015). Together as one: Shared leadership between managers. International Journal of Business & Management, 10(8), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v10n8p46

- *Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2019). Att förändra organisatoriska förutsättningar: Erfarenheter av att införa funktionellt delat ledarskap i skola och förskola. Arbetsmarknad & arbetsliv, 25(2), 46–66. https://journals.lub.lu.se/aoa/article/view/20015/18046

- *Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2020). Changing organisational conditions: Experiences of introducing and putting function-shared leadership (FSL) into practice in schools and pre-schools. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 20(4), 672–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2020.1734628

- Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (2021). Fifty-five years of managerial shared leadership research: A review of an empirical field. Leadership, 17(6), 715–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/17427150211037809

- Döös, M., & Wilhelmson, L. (in press). Delat rektorskap: Om samarbete byggt på förtroende. In N. Rönnström & P. Skott (Eds.), Rektorers praktiska yrkeskunnande och vetenskapliga lärande (prel. title). Gleerups.

- *Döös, M., Wilhelmson, L., Madestam, J., & Örnberg, Å. (2017). Shared principalship: The perspective of close subordinate colleagues. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 18(4), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2017.1384503

- *Döös, M., Wilhelmson, J., Madestam, L., & Örnberg, Å. (2018a). The principle of singularity: A retrospective study of how and why the legislation process behind Sweden’s education act came to prohibit joint leadership for principals. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 2(2–3), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2757

- *Döös, M., Wilhelmson, L., Madestam, J., & Örnberg, Å. (2018b). The shared principalship: Invitation at the top. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 21(3), 344–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2017.1321785

- *Eckman, E. W. (2006). Co-principals: Characteristics of dual leadership teams. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5(2), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760600549596

- *Eckman, E. W. (2007). The coprincipalship: It’s not lonely at the top. Journal of School Leadership, 17(3), 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460701700303

- *Eckman, E. W. (2018). A case study of the implementation of the co-principal leadership model. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 17(2), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2016.1278243

- *Eckman, E. W., & Kelber, S. T. (2009). The co-principalship: An alternative to the traditional principalship. Planning and Changing Journal, 40(1/2), 86–102.

- *Eckman, E. W., & Kelber, S. T. (2010). Female traditional principals and co-principals: Experiences of role conflict and job satisfaction. Journal of Educational Change, 11(3), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-009-9116-z

- *Flessa, J. (2014). Learning from school leadership in Chile. Canadian and International Education, 43(1), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5206/cie-eci.v43i1.9237

- *Gronn, P. (1999). Substituting for leadership: The neglected role of the leadership couple. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)80008-3

- *Gronn, P., & Hamilton, A. (2004). “A bit more life in the leadership”: Co-principalship as distributed leadership practice. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 3(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1076/lpos.3.1.3.27842

- *Grubb, W. N., & Flessa, J. J. (2006). “A job too big for one”: Multiple principals and other nontraditional approaches to school leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(4), 518–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X06290641

- Hacker, J. V., Johnson, M., Saunders, C., & Thayer, A. L. (2019). Trust in virtual teams: A multidisciplinary review and integration. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 23, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v23i0.1757

- Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760500244793

- Harris, A. (2013). Distributed leadership: Friend or foe? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(5), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213497635

- Hasel, M. C., & Grover, S. L. (2017). An integrative model of trust and leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(6), 849–867. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-12-2015-0293

- Heenan, D. A., & Bennis, W. (1999). Co-leaders. The power of great partnerships. John Wiley & Sons.

- *Hewitt, P. M., Denny, G. S., & Pijanowski, J. C. (2012). Teacher preferences for alternative school site administrative models. Administrative Issues Journal, 2(1), 74–82. https://dc.swosu.edu/aij/vol2/iss1/8

- Hodgson, R. C., Levinson, D. J., & Zaleznik, A. (1965). The executive role constellation. An analysis of personality and role relations in management. Harvard University.

- Holste, J. S., & Fields, D. (2010). Trust and tacit knowledge sharing and use. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(1), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271011015615

- *Ho, J., Shaari, I., & Kang, T. (2021). The distribution of leadership between vice-principals and principals in Singapore. International Journal of Leadership in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1849811

- Huber, S. G., & Muijs, D. (2010). School leadership effectiveness: The growing insight in the importance of school leadership for the quality and development of schools and their pupils. In S. G. Huber (Ed.), School leadership – international perspectives (Studies in Educational Leadership 10, pp. 57–77). Springer Science+Business Media.

- *Hughes, M., & James, C. (1999). The relationship between the head and the deputy head in primary schools. School Leadership & Management, 19(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632439969357

- Kosonen, P., & Ikonen, M. (2022). Trust building through discursive leadership: A communicative engagement perspective in higher education management. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(3), 412–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2019.1673903

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

- Luhmann, N. (1968). Vertrauen. Ein Mechanismus der Reduktion sozialer Komplexität. Ferdinand Enke Verlag.

- Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust - a mechanism for the reduction of social complexity. (H. Davis, J. Raffan, & K. Rooney, Trans.). In T. Burns & G. Poggi (Eds.), Trust and power. Two works by Niklas Luhmann (pp. 1–103). John Wiley & Sons.

- Macmillan, R. B., Meyer, M. J., & Northfield, S. (2004). Trust and its role in principal succession: A preliminary examination of a continuum of trust. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 3(4), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760490901993

- *Madestam, J. (2017). En rektor när staten åter vill styra. Förändringar i skollagen som uttryck för metagovernance. Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift, 94(2), 37–58. https://www.djoef-forlag.dk/openaccess/nat/index.php

- *Marks, W. (2013). The transitional co-principalship model: A new way forward. Australian Educational Leader, 35(2), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.898541902934248

- *Masters, Y. (2013). Co-principalship: Are two heads better than one?. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education, 4(3), 1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijcdse.2042.6364.2013.0170

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/256727

- McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L. (1998). Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.2307/259290

- Näslund, L. (2018). Förtroende och tillit – vad är det? Organisation & Samhälle-Svensk företagsekonomisk tidskrift, 2018(2), 18–23.

- Neumerski, C. (2012). Rethinking instructional leadership, a review: What do we know about principal, teacher, and coach instructional leadership, and where should we go from here? Educational Administration Quarterly, 49(2), 310–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X12456700

- *Notman, R. (2020). An evolution in distributed educational leadership: From sole leader to co-principalship. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 35(January), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.21307/jelpp-2020-005

- Öman, S. (2005). Juridiska aspekter på samledarskap - hinder och möjligheter för delat ledarskap. Arbetslivsinstitutet.