Abstract

Postsocialist urban development is partially characterised by housing deterioration and the perpetual overrepresentation of Romanian Roma in substandard dwellings. These phenomena are particularly noticeable in the margins of larger Romanian cities. Many poor Romanians found, in urban peripheries, a last resort during a period of economic crisis and housing shortages. In the meantime, public policy and urban planning have focused on maintaining ‘collective order’ and accommodating the wishes of the ‘decently’ housed residents of the city. This is certainly the case in Bucharest, where squatters and homeless people have been expelled from central districts and where the same privileged districts receive substantially more attention. This collective order is apparently deemed more important than the needs of marginalised groups in Romanian society. This article examines how urban marginality is addressed at the municipal level and how ‘parsimonious’ public intervention in poor residential areas is justified. In doing so, I highlight the roles of postsocialist devolution, inadequate use of EU and national funds, and reviving racialisation in reproducing housing poverty.

Introduction

Over the past three decades, Romanian politics and governance have been reconfigured dramatically. The centrally-led socialist planned economy was replaced by a decentralised and market-oriented model. Decentralisation of authority was one of the conditions of the European Union (EU) for Romania’s accession (Dobre Citation2010; Ion Citation2014; Profiroiu, Profiroiu, and Szabo Citation2017). Decentralisation was conflated with financial and political autonomy and more citizen participation. However, the devolution of authority has also meant that most socioeconomic challenges fell under the responsibility of local administrations. In return for these thoroughgoing reforms, the EU promised generous funding that would finance locally expressed needs. In practice, however, the situation has proven to be much less tractable (Clapp Citation2017; Profiroiu, Profiroiu, and Szabo Citation2017; Vincze and Zamfir Citation2019).

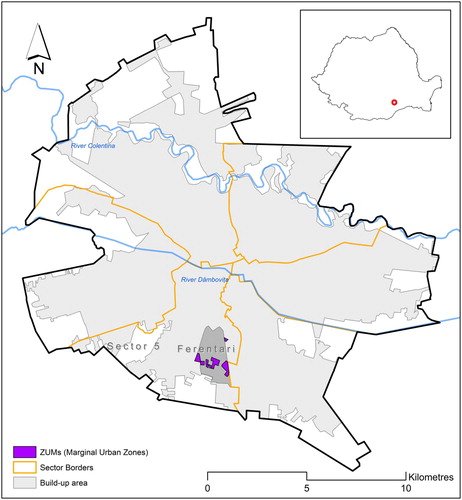

I focus on the decentralised governance of one of Bucharest’s administrative sub-units, Sector 5Footnote1 and aim to understand what role governing institutions in Bucharest play in the reproduction or mitigation of housing decay and severe socioeconomic deprivation. Sector 5 contains Ferentari (see ), a notorious neighbourhood with a disproportionately high presence of Romanian Roma.Footnote2 The neighbourhood exhibits severe social, technical, and economic difficulties. These issues could and should be eligible for EU Cohesion Policy funds or Romania’s own development funds, but are largely overlooked by local politicians, who are responsible for applying for grants-in-aid. Moreover, urban displacement and ‘Romaphobia’ has further pushed poor Roma to the urban margins in recent years (Lancione Citation2017; O’Neill Citation2010; Vincze Citation2018; van Baar Citation2018).

Racial and socioeconomic segregation worsened in Romania after the fall of state socialism (Berescu, Petrović, and Teller Citation2013; Powell and Lever Citation2017; Vincze and Zamfir Citation2019), with over 25% of all Romanians living in poverty (INS Citation2016) and Roma representing up to 50% of the population in deprived neighbourhoods (Vincze Citation2018). This situation can be partially explained by understanding the incapacity of local authorities and their apathy in absorbing available EU or national funds (Ion Citation2014) as creating a ‘local trap’ of decentralisation. Although governance and decentralisation in Romania are increasingly subjects of scholarly interest, no recent works have used the local trap concept in problematising local decision-making. According to Mark Purcell (Citation2006, 1921), the local trap is ‘the tendency to assume that the local scale is preferable to other scales’, because local decision-making supposedly reflects local, democratically-informed desires and requirements. But who informs these desires? Is it the electorate or rather local coalitions of private and public actors? For Purcell (Citation2006, 1921), this remains highly uncertain, and local decision-making gives no guarantee of increased popular participation, as ‘all depends on the agenda of those empowered’. By considering the case of Bucharest and the local-level actions there, this article supports the argument that the local scale is not a priori the best scale for producing good outcomes. Moreover, it also argues that racialised discourses at the local administrative level can only increase the hazards of the local trap.

I analyse the Bucharest’s housing governance in poor districts through two sets of data: interviews and document analysis. Through the interviews with officials, I attempted to obtain information about how substandard housing, external development funds and existing policies, and the situation of Bucharest’s poor are understood. The selected official documents are analysed in order to establish what the existing social housing policies are and what is proposed to desegregate Bucharest and increase the city’s number of affordable housing. The fieldwork took place in three periods: November 2011–March 2012, March 2014, and June–September 2015. The local housing and governance situation of Ferentari and Sector 5 was discussed with a total of fourteen informants. Of these, five were officials from Sector 5 and two were planners from Bucharest city hall.Footnote3 The informants from Sector 5 were active in the domains of housing, planning, public works, and racism and equal rights.

In total, I conducted 12 face-to-face interviews with these officials, interviewing one city hall planner four times and conducting follow-up interviews with two officials from Sector 5. These seven state officialsFootnote4 did not respond to my email and phone invitations, but were recruited through happenstance. Even when visiting the city hall and the Sector 5 office, I was repeatedly ignored. It was through an unplanned encounter with someone from Sector 5 that I gained access. This person also initiated a snowball effect by putting me in touch with other officials from Sector 5, only five of whom ultimately accepted my invitation to participate. My academic background raised suspicions, while race- and poverty-related questions often resulted in lack of interest in further cooperation.

Furthermore, I held two interviews with the French diplomat Jérôme Richard, serving as a coordinator of Sector 5’s master plan for Ferentari, and two with Petre Florin Manole, Romania’s secretary for the national minority commission and a Roma himself. All interviews were semi-structured and, as requested by some informants, anonymity was provided. I also interviewed five experts in housing exclusion (i.e. Cătălin Berescu, Liviu Chelcea, Florina Presada, Anemari Necsulescu, and Florin Botonogu) who shared critical reflections on the actual state of affairs and helped me analyse the gathered data.

In addition, I analysed: (1) Bucharest’s General Urban Plan, Plan Urbanistic General (PUG); (2) a master plan for the cohesive future urban development in the city, Strategic Concept Bucharest 2035, Concept Strategic Bucureşti 2035 (CSB); (3) Sector 5’s latest master plan, Regenerare Urbană Ferentari (RUF; Sector Citation5 Citation2017); (4) social housing allocation procedures; and (5) an internal housing project from Sector 5. The analysis of Ferentari’s housing and socioeconomic policies is primarily based on transcribed interviews, official documents, and social housing allocation procedures.

In what follows, I first ‘set the stage’ for the article’s theoretical framework by analysing a selection of remarkable quotes from one interviewed official. In the remainder of the section, I describe how a local trap was created in Romania’s Europeanisation and decentralisation processes, which involved the problematic pairing of centralised funding decisions and local decentralised socioeconomic policymaking. Second, I discuss the literature on the racialisation of Bucharest’s poor and their ongoing displacement from central areas. Third, by drawing on empirical data and local policy documents, this paper illustrates how local, everyday politics has unfolded and failed to address socioeconomic and housing problematics. While arguing that the ill-prepared decentralised governance structure of Bucharest has played a major role in reproducing poverty, I also comment on the racist sentiments that have further frustrated the implementation of inclusive policies.

Local governance, postsocialist citizenship and marginalising the poor

In March 2014, I first interviewed a public works official from Sector 5. A selection of his thoughts on Sector 5 in general and Ferentari in particular sets the stage for the literature to be discussed. When I first brought up the topic of ‘good governance’, he responded that his district was ‘probably leading in the country’, and continued to state that the sector ‘made schools, kindergartens … parks … in the poor areas of the sector … 99% of all streets are connected to the sewer system, all paved’. Furthermore, the official stressed that citizens were fully responsible for their living conditions. Even the serious issues of drug use, flooded cellars of apartment blocks, rat infestations, and the severe dilapidation of buildings in the sector’s poorest areas were deemed private concerns, matters to be addressed by local residents or by strict policing. Essentially, he underscored a narrow understanding of local governance in his sector that can be summarised as follows: the investments in local well-being and economic sustainability serve above all the ‘car-owning, tax-paying, and hard-working’ Romanian, while welfare support is kept at an insignificant level. When I tried to find out whether any efforts were really being made to construct much-needed public housing (he was after all a member of the Romanian Social Democratic Party), the conversation suddenly changed track. An extensive, disdainful account of poor Bucharesters followed, characterised by distrust, contempt, and hatred:

‘Let’s be honest here, didn’t we give them [i.e., the poor Bucharesters from Sector 5] these “vagabond” apartments on Livezilor, Zăbrăuţilor, and Carpaţi? We connected them to water, we cleaned the buildings, we did I don’t know what else … A kindergarten was built. But these people need to be adopted, and this is what the EU doesn’t understand. The EU is reacting like a freaked-out woman, and instead of adopting these people, to change them, to give them livelihoods [in richer parts of the Union], they provide these inclusion funds. Their reaction is like a guy who gives money to his hysterical wife, just so he can be left alone.’

‘Everywhere in the world, you encounter poor settlements, but in most cases people prove to be inventive, you understand? But my impression of Gypsies is that, wherever they settle, the fields are parched. If you’d return after two years to an abandoned settlement, it’d be a miracle if anything was actually growing where they pitched their camp. Not sure how, don’t know what they do, but there must be acid in their urine. Wherever they stop, they raze everything to the ground. I talk about the Gypsies that are not Romanianised … old habits persist and I am happy to see them leaving Romania. Because before they left, some ten years ago, they robbed us, they harassed our women – they grabbed purses out of their hands, [but] now they rob yours, you understand?’ (March, 2014)

Bucharest’s local trap: from top-down planning to badly managed governance

Bucharest’s spatial development is increasingly dictated by global capital investment (Nae and Turnock Citation2011), with local budgets being streamlined to sustain this processFootnote5 (Ion Citation2014; Light and Young Citation2015). The literature usually refers to streamlining as the process by which elected governing bodies become less influential over the patterns of urban development and less accountable to the electorate (Goodwin and Painter Citation1996; Purcell Citation2006). Streamlining can further be traced back to reduced taxes, increased—and yet selective—public infrastructure spending, the privatisation of municipal infrastructure, and the relaxing of planning permitting (e.g. Geddes Citation2005; Jessop Citation2005; Jessop, Brenner, and Jones Citation2008). This shift to streamlined governance did not start immediately after 1989. The first postsocialist decade was chaotic, during which the lack of financial resources reduced the role of the local governments to ‘the delivery of basic services, the reviewing of permit applications, the granting of zoning variances and the permitting of a patchwork of small- and medium-sized private building projects’ (Ion Citation2014, 177). From the late 2000s, increased investments from EU and national funds changed this situation. However, the new financial opportunities did not result in increased social expenditures. Local governments were instead active in financing, for example, renovation works, flagship projects (e.g. a new national stadium or the People’s Salvation Cathedral), and major infrastructural projects. An in-depth discussion of these urban developments and streamlining is beyond the scope of this paper; instead, I focus in the remainder of this section on how the imposed devolution is potentially a local trap due to the dismissal of local claims in governance.

According to Mark Purcell (Citation2002, Citation2006, Citation2013), an urban democratic crisis can emanate from the assumption that devolved decision-making equals increased public control. This assumption implies that local governance decreases the gap between elected representatives and the electorate. Local governance or ‘the local’ is thus ‘conflated with the good’ and becomes a political end in itself, rather than ‘a means to an end such as democracy, justice or sustainability’ (Purcell Citation2006, 1927). However, the transfer of administrative responsibilities from the national to local levels can risk reducing access to social services if local budgets are insufficiently bolstered. This problem can manifest itself in two ways. On one hand, the local can simply be a suboptimal scale at which to carry out complex tasks. Certain political interventions or certain contexts simply require different scalar arrangements, which are hard to establish a priori. Second, decentralisation can potentially marginalise the needs and rights of minority groups. Despite these being expressed, the majority of the electorate can silence these minorities by an overly narrow interpretation of urban democracy (Attoh Citation2011). Purcell does not entirely reject the local as a political scale for increased democracy, but he rejects the uncritical acceptance of devolved responsibilities that potentially undermine social justice.

In Romania’s case, the country underwent rigorous decentralisation during the 1990s in order to start the European integration process and become eligible for EU funds (Dobre Citation2010; Ion Citation2014; Profiroiu, Profiroiu, and Szabo Citation2017). At the same time, fund-granting decisions became increasingly ‘regionalised’. Romania has opted for ‘regional operational programmes’ that are created and administered by development regions.Footnote6 Through these programmes, local administrations are expected to (1) identify where people are at risk of poverty and exclusion and (2) submit application proposals for the EU’s structural and regional development funds. Subsequently, the development region is responsible for selecting funding applications and redistributing granted funds. The pervasive problems flowing from this approach can be captured in two developments. First, local politicians clearly favour ‘fast-track, large-scale’ infrastructural projects and city beautification programmes as a way to gain political capital among their electorate (Ion Citation2014; Marin and Chelcea Citation2018). Second, the political affiliations of local recipients are often of overriding importance, and funds are seen by state officials as a ‘vehicle for the extraction, instead of the redistribution, of public resources’ (Ion Citation2014, 172). Consequently, the use of national and EU funds is narrow (i.e. for infrastructure and beautification), leaving many vital and much-needed tasks, such as housing renovation and construction, unaddressed. Ample reason exists to question the effectiveness of Romania’s decentralisation process in reducing the gap between ‘local needs’ and actual policy outcomes.

The initial low absorption of EU and national funds and the subsequent urgency of increasing the use of allocated public funds have resulted in an increase in the number of ‘fast-track’ infrastructural and beautification projects (Ion Citation2014; Tosics Citation2016). This recent phenomenon has exposed the inability of local administrations in Romania to counter social polarisation with available public funds. Instead, projects approved in Bucharest have disregarded poorer parts of the city (Ion Citation2014; Surubaru Citation2017), destroyed cultural heritage (Calciu Citation2016), and stimulated car use in an already congested city (Chelcea and Iancu Citation2015; Ion Citation2014).

The above examples illustrate how development proposals originating from the drawing boards of local administrations do not necessarily consider the needs and desires of local inhabitants. This is not to say that the local level cannot be radically changed by effective resistance or citizen participation, but rather illustrates that in the Bucharest context, neoliberal urbanism prevails.

Governing Bucharest’s poor citizens: some examples of displacement practices

On top of the issues involving devolution, poor Bucharesters are also being actively displaced by the city’s governments. I follow here Vincze and Zamfir (Citation2019) who argue that much of the displacement politics in Romania are closely linked to spatial racialisation of the poor and the (often informal and substandard) settlements they inhabit. They argue that spatial racialisation enables authorities to ‘easily’ displace ‘the poor, the Roma [from] the spaces where they live’ in order ‘to increase their [the space’s] value’ (Citation2019, 445). Studies of evictions (Arpagian and Aitken Citation2018; Lancione Citation2017; Vincze and Zamfir Citation2019), gentrification (Chelcea, Popescu, and Cristea Citation2015), the policing of unwanted poor in central districts (Chelcea and Iancu Citation2015; O’Neill Citation2014, Citation2017; Vincze and Zamfir Citation2019), and the removal of illegal settlements (Lancione Citation2017; StudioBASAR Citation2010; Vincze and Zamfir Citation2019) have exposed some aspects of how the city and sector councils endeavour to move people away from squats, sidewalks, and central areas.

However, there are different interpretations of the local management of poor Bucharesters. Michele Lancione (Citation2017, Citation2019) has described, for example, the active banishment of an evicted Roma community that tried to resist eviction by camping in front of their former dwellings. He argued that within the overarching processes of the capitalist system, local politics further shape precarity. In particular, the violent reactions to re-squatting, the occupation of public space, and demonstrations reveal for Lancione a clear political choice: one engages constructively with deepened precarity or otherwise faces relentless violence.

Bruce O’Neill instead highlights the sophisticated politics of the domination and subjugation of poor and jobless Bucharesters. In his works (Citation2010, Citation2014, Citation2017), O’Neill has followed a group of what he calls ‘idle’, ‘bored’, and ‘invisible’ Bucharesters. His ethnographic engagements with this group reveal a different interpretation of the displacement policies targeting Bucharest’s most precarious groups. Instead of arguing that the activities and lifestyles of these impoverished people are ‘unrecognised social production’ or ‘radical contestations’, he identifies disguised forms of inhabiting that are intended to stay outside the institutional gaze (O’Neill Citation2017). Daily practices such as consuming, working, and dwelling are experienced by these poor Bucharesters as profoundly insignificant. Squatting, for example, is described as the art of not attracting the attention of the municipality or neighbours. This is achieved by making as little noise as possible and being home only at strictly necessary times of day. The labour activities of these marginal poor (mostly helping car drivers finding free spots) are marked by high stress levels due to a daily hide-and-seek with patrolling policemen, and the purchase of groceries takes place in small and unpretentious booths, as these people are denied access to regular supermarkets. Hence, seen from this perspective, precarity is not necessarily banished to more peripheral spaces but continues through humiliating rhythms outside the institutional gaze.

The situation in Ferentari

Ferentari takes a somehow unique place in Bucharest. It contains the highest concentrations of Bucharest’s most deprived communities and it is indeed also the place where many Bucharesters affected by the policies described above found a last resort. Although the actual number of impoverished Bucharesters inhabiting Ferentari is difficult to determine, estimates range from 12,000 to 40,000 (Teodorescu Citation2018; Sector Citation5 Citation2017). These people live concentrated in the south of the neighbourhood, the area also often called the ghetto (ghetou), ‘the Bronx’ (Bronxul), or ‘Gypsy land’ (ţigănie). Gergő Pulay (Citation2015) is right when he claims that an imaginary container was placed in Ferentari, filled with all the prejudices of majority society regarding socio–ethnically deprived areas—‘an internal Orient’, to paraphrase Edward Said. Imminent evictions are a smouldering threat here. However, in Ferentari, one can also see how a complex assemblage of informal economic activities animates hopes of improved living standards (Teodorescu Citation2018; Pulay Citation2015). Many apartments are used as workplaces where, for example, shoes and grave wreaths are manufactured, hair is cut for a fair price, and groceries can be bought on credit (cumpărături pe caiet).

Beyond this in situ entrepreneurship, Ferentari also hosts numerous flower warehouses, scrap recycling companies, and thriving networks of more obscure businesses. Pulay (Citation2015, 130) accurately suggested that ‘the neighbourhood can be understood as an extremely busy intersection between diverse local and transnational networks’. Nonetheless, this pauperised population’s urgent needs and critical housing situation are obvious. In the remainder of this article, I examine how these are understood and addressed by the local authorities.

Actual and future housing inclusion efforts: does it work and for whom should it work?

Analysis of my data identifies three distinct but related policy issues. First, the actual social housing provision in Bucharest is discussed. Second, I provide an overview of some policy plans that have been presented in recent years. At least on paper, these are intended to increase the number of social housing units and to improve the overall living conditions in Bucharest. Third, I situate local governance within a discussion of racism and political disregard for poor Bucharesters. Arguably, this section illustrates how unclear social housing rules, insufficient labour and know-how, scarce financial resources, and racist attitudes among local officials thwart effective housing policy implementation.

While this article offers a case study of local governance practices in administrative units with high Roma segregation, this does not mean that a poor Bucharester is necessarily a Romanian Roma. Poverty and exclusion are, however, heavily racialised in Romania (Creţan and Powell Citation2018; Csepeli and Simon Citation2004; Vincze and Rat Citation2013; Vincze and Zamfir Citation2019). According to Rughiniş (Citation2010), the racialisation of poor places results in the ‘hetero-attribution of ethnicity’ by officials to local residents, i.e. the ascription of ethnicity to an individual or community by Romanian officials based on a set of racialised stereotypes. For example, several residents I spoke with in Ferentari did not identify as Roma or said they were half-Roma, half-Romanian. Interviewed officials, on various occasions described Ferentari’s population as ‘Gypsies’ (ţigani) or ‘people of colour’ (oameni de culoare) only because they resided in the Sector’s poorest parts (the ‘Gypsy land’).

Existing social housing policies in Ferentari

The official introduced above mentioned that his sector ‘really insisted’ on offering better conditions to its impoverished residents. The experience of residents and my findings indicate the opposite. Romania became a ‘super homeownership society’ after 1989 through government decree No. 61/1990. By that decree, privatised state-built, socialist-era dwellings were offered at low prices to sitting tenants supported by advantageous loans—a so-called giveaway privatisation. As a result, the proportion of social housing units dropped to 2% at the national level and just below 1% in Bucharest (Romanian Statistics Institute, INS). In addition, the new National Housing Agency, Agenţia Naţională pentru Locuinţe (ANL),Footnote7 founded in 1998, did not meet the EU requirements to build 100,000 new units per year (Amann et al. Citation2013). In Ferentari, the little remaining social housing is concentrated in small one-room apartment blocks from the 1960s (the earlier mentioned ‘vagabond apartments’). The few newly built ANL social housing estates are far from Ferentari and mostly outside Sector 5. That is a problem, because some ANL dwellings are only available to Sector-residents. Furthermore, tenancy requirements are stringent. For example, one must prove that one has not previously owned a dwelling, as ANL dwellings are primarily intended to provide housing for groups that could not benefit from the large-scale housing privatisation of the early 1990s. One of the planners from city hall clarified this issue:

‘Of course, social housing or municipal housing companies are nonexistent and plans to build new houses for people living in inadequate dwellings do not exist, either. Not in a concrete sense, at least. Sure, there is the ANL, but that agency sets unrealistic goals and building criteria, which clearly do not correspond to the needs of such people.’ (Official A, March 2014)

I was intrigued by the words ‘such people’ and ‘unrealistic criteria’. The planner reasoned that the high prices and exclusive locations of most ANL projects make new social housing unaffordable for poor Bucharesters.

Also, the rental system for existing social housing stock has its limitations. First, the point system for applicants (based on Housing Law No. 144/1996) differs significantly between the sectors. Only Sectors 5 and 6 favour large families living in poor conditions. All other sectors and the city hall clearly favour young university graduates and households with stable incomes. When discussing this issue with an activist working at a local NGO, we realised that her situation (i.e. renting a house, having a stable income, and graduated) gave her more queuing points in Sector 1 or at the city hall than those of a large household with irregular or no income and living in poor conditions. However, in Sectors 5 and 6 there is a much smaller social housing stock and greater demand due to the larger number of poor Bucharesters and the much smaller budgets of these sectorsFootnote8 (Ghiţă et al. Citation2016; Zamfirescu Citation2015). Sectors 2, 3, and 4 did not publish their point system, but only stated that they followed the above mentioned law.

So, social housing is almost nonexistent, new plans to build additional social housing are lacking, and queuing rules differ from sector to sector. This problematic situation was emphasized by the planner quoted above:

‘So I do understand the frustration [among poor Bucharesters], but the problem comes from above, from the government that obstructs the proposals for EU funding, which surely could revitalise southern Bucharest … On the other hand, we have improved many areas … But a communist mentality persists among many people, people waiting for someone to come and help them. Yet, times have changed and we are not addressing every aspect of life for them. They [i.e. presumably poor households] also bear responsibility for their situation.’ (Official A, July 2015)

This critical narrative connects well with what Jessop (Citation1999, Citation2005) has called the critique of self-expanding welfare provision. This implies that extensive welfare regimes are blamed for generating the problems they seek to address. As a result, these regimes are not ‘responses to pre-given economic and social problems’ but constituents ‘of their objects of governance’ (Jessop Citation1999, 352). The ‘communist mentality’ was in that sense arguably generated by a previous system that addressed socioeconomic problems through self-expansion in the fields of, for example, housing and labour markets. That self-expansion, in its turn, nurtured a passive and indifferent ‘mentality’, because ‘everything was provided for’. However, that expansion stopped suddenly in 1989, and conditions in much of the sector’s public housing deteriorated rapidly. In the early 1990s, small and inadequate apartments were abandoned and no longer maintained by Sector 5. In the years to follow, instead of active maintenance and allocation policies, the sector adopted a policy of ‘finders keepers’ (interview with Berescu, July 2015; interview with Necsulescu, September 2015). All persons residing in an unclaimed apartment could register their apartment with Sector 5 as a social housing dwelling. The thousands of other impoverished Bucharesters who could not find a vacant spot or afford private rentals were condemned to the informal housing markets that emerged in southern Ferentari (Teodorescu Citation2018). These were, not unusually, apartments expropriated by local money lenders (cămătari) or drug barons. When I asked the planner whether economic downturns rather than a supposed communist mentality could explain much of the impoverished situation, he instead added ‘auto-segregation’ of the ‘Roma residents’ to the story:

‘One can observe that many of them, even the ones with income, prefer not to invest in houses. They keep the money for other things, for okay and less okay investments … It’s a strong community now … and they need to make an effort first to accept making investments themselves and to accept our presence. There is reticence [to do so].’

Plans and proposals for increased housing inclusion

As stated earlier, EU accession meant that increased public funds were available for local administrations in Romania. In the case of Bucharest, these financial possibilities finally offered a chance to set in motion plans for social inclusion. What are Bucharest’s concrete policy aims for targeting housing decay and concentrated spatial poverty? To answer this question, I analyse the city’s master plan on urban cohesion, Strategic Concept Bucharest 2035 (CSB) (PMB Citation2011), in relation to the existing plan, PUG (approved 2002). CSB is intended to update PUG and guide ongoing developments in a more satisfactory way. On numerous occasions, the two interviewed city hall planners expressed high hopes for CSB. Additionally, at the sector level, I highlight RUF together with some other local proposals intended to increase the number of affordable housing units.

CSB identifies serious postsocialist development setbacks that resulted in the present socio-economically segregated city. It characterises these recent developments as the outcome of unplanned, unequal, and uncontrolled spatial production (cf. Ion Citation2014; Marin and Chelcea Citation2018). It further states that the present situation can largely be attributed to

‘decreasing quality of local governance, weak involvement of the central administration in coordinating the issues of an area of national importance, inefficiency of local policies, and insufficient planning capacities.’ (PMB Citation2011, 39, author’s translation)

CSB also highlights the existence of chaotic and speculative development in thriving parts of the city, seeing it as one of the postsocialist root causes of the production of unaffordable housing, although the earlier quoted planner (Official A) would probably disagree. When it comes to policy proposals and potential revisions of existing government structures and planning forms, nothing rigorous is proposed to address the ‘weakly involved’ policymakers. CSB instead advises city hall on how to direct public investments to boost the competitiveness of Bucharest’s economy, i.e. how to adopt growth strategies and best practices from thriving urban regions elsewhere (e.g. focusing on biotechnology, IT, educational, and entrepreneurial hubs). Here, CSB clearly favours the flow of public money into projects that supposedly generate economic growth.

CSB’s ‘sub-strategy’ on housing states that housing is primarily the responsibility of the homeowner. Only cases of severely deprived tenants and homeowners should be supported by ‘co-financed programmes and projects, initiated by the city hall or sectors’ (PMB Citation2011, 141). Essentially, this open-ended formulation legitimates the current state of affairs that has tolerated segregation and housing decay. Concurrently, CSB’s more explicit calls for infrastructural projects and urban redevelopment might contribute to an even more competitive city. Or as Purcell (Citation2006, 1934) would have it, the promotion of economic growth allows money to flow into already thriving areas rather than bolstering the wellbeing of all Bucharest’s inhabitants: it is the ‘neo-liberal instinct to sacrifice such questions on the altar of competitiveness’.

In fact, PUG (from 2002) refers more explicitly to much-needed radical change in relation to social housing provision:

‘Though required by a large part of Bucharest’s population, nothing serious can be achieved within the domain of public housing without the elaboration of clear programmes and the existence of a new law. [New social housing programmes] should also not have any political connotation; they should be indifferent to whoever is in power.’ (p. 10 of Article 1:10, author’s translation)

Later in PUG (Article 2, on housing), it is mentioned that social housing dwellings should never exceed 20–30% of new private-led or PPPFootnote9 housing developments and not be inferior in quality to other dwellings. This is proposed to avoid socioeconomic segregation and blatant discrepancies in housing quality. However, while social housing dwellings are capped at 30% of new housing developments, reality shows that 0% is the more accurate output figure (INS Citation2016).

To further illustrate how local decision-making can disregard the needs of Bucharest’s poorest groups, I now discuss the lowest administrative level, the sector level, and specifically Sector 5. Although it was difficult to identify a coherent housing inclusion strategy, at least two plans were given to me and discussed. One of the recent ‘concrete’ policy outcomes was a 2014 document specifying that the sector’s then mayor, Marian Vanghelie, ‘signed a partnership agreement with the Chinese investment company Shandong Ningjian Construction Group, in order to form a public–private partnership (PPP) that would realise the construction of a neighbourhood of 25,000 dwellings’ (2014, 1, author’s translation). However, in 2017 several Romanian newspapers reported that the Chinese company had ceased its activities in Romania. Nevertheless, the trust in this plan exposes the limited role of the sector level in housing provision. When discussing the inclusion of affordable housing in the project, Official C assured me that an unspecified ‘percentage’ would consist of ‘social housing units’:

‘These houses will be made available for a period of 2, 3, or 5 years, until the people solve their problems and can move on to the regular housing market … [It is vital to have] those new apartments, because we now have over 10,000 people in the queue waiting for social housing and only 40Footnote10 administered dwellings in our stock.’

The strong desire to eliminate concentrations of poverty was incorporated in the latest master plan for Ferentari, RUF (Sector Citation5 Citation2017). This document identified seven ‘marginalised urban zones’ (ZUMs) in Ferentari (see ). According to RUF, these areas are characterised by (1) low human capital, (2) low legal employment rates, (3) precarious living conditions, and (4) ‘problems with the Roma population’. The seven ZUMs encompass 5700 dwellings and 36,544 inhabitants. The percentage of Romanian Roma differs between ZUMs, but is estimated in the document to be as high as 90% in the ‘vagabond block’ areas.

Briefly stated, the plans for the ZUMs are to regenerate and revitalise the areas. The regeneration implies, among other matters, stimulation of the local labour market, better healthcare, special attention to substandard housing, and increased green space. The revitalisation will focus instead on better urban services, such as new public and economic centres (e.g. squares with newly built market halls and cultural centres that ‘promote multicultural local traditions’). What is more important (and threatening) for the residents of the ZUMs, however, are the RUF’s aims to reclaim former public spaces and to demolish all ‘ghettoised’ blocks of apartments and unauthorised construction by the end of 2022 (Sector Citation5 Citation2017, 94 and 98). In turn, the construction of new condominiums is to be ‘promoted’ in the same period at a cost of over EUR 70 million. It is difficult to believe that this sum is enough to replace thousands of decayed dwellings, and the RUF schedule was already behind schedule as of 2017. During my most recent contact with Mr Manole (March 2018), I was informed that RUF is still in its initial phase: ‘Nothing has been concretised thus far’. By the end of 2018, for example, an entire new section of Bucharest’s former public transport depot was to be finished; this did not happen. Nonetheless, what did happen were the planned evictions from slums, for example, on Iacob Andrei Street. Following Lancione (Citation2017), these evictions demonstrate the local political choice to further shape precarity in Ferentari.

During my interviews with the sector’s officials, a clear narrative emerged in relation to decayed housing. Most officials expressed a desire to regenerate Ferentari by making it look ‘just like the rest’ of the city. This means, for example, that a science park and a creative industry hub need to appear in the areas around the ZUMs (Sector Citation5 Citation2017, 48), so that the ‘local potential is capitalised’ (Sector Citation5 Citation2017, 21). Whether the deprived households and unregistered residents will be re-housed in these major projects is arguably a subordinate consideration. To illustrate this point, I turn to the French partner’s impressions of RUF, which, following Purcell (Citation2006), clarify the incapacity of local-scale to ensure increased popular participation and inclusive policies. According to Mr Richard, in the years before RUF’s adoption, strong doubts existed about the sincerity of the involved actors and the feasibility of the set aims. Throughout RUF’s preparation stage, ‘storytelling strategies’ were used to camouflage the ‘local lack of interest in committing themselves’ to the promised and much-needed political agenda. Storytelling, he argued, was not helping the ‘40,000 people living in poverty’. In his eyes, this unwillingness was expressed through the obstruction of integrated multi-scalar collaboration with the national or EU levels. Furthermore, there was no broad interest in creating projects with inhabitants or in creating databases of the actual number of people in need of new housing (including unregistered residents).

Mr Richard was in Romania in the 2011–2015 period to help local officials formulate funding proposals and RUF. In his eyes, success in Ferentari was vital for the rest of the country and for Romania’s decentralisation process. He noted that if a local coalition succeeded in redeveloping such an impoverished urban setting, then ‘practically every other municipality in Romania should be able to follow the “successful Ferentari model”’. Real solutions, such as the reconstruction of much of Ferentari’s housing stock and the immediate start of temporary housing construction, are, in his words, ‘too complex projects for the sector’ and require a multi-scalar approach and much bigger budgets. Sector 5 showed no intention to cooperate: ‘It never registered the amount of squatters and other unregistered residents, [and it] does not commit itself to long periods of preparations for gigantic housing projects’ (interview, September 2015).

Finally, this article considers the influence of racism at the local institutional level and the role this has played in the unwillingness to combat poverty among Romanian Roma—or at least in areas where the inhabitants are regarded as belonging to this minority.

Racist prejudices among local officials

In the general narrative of the local officials, Ferentari was imagined to be a ‘Gypsy area’ of Bucharest. In line with Rughiniş (Citation2010), it was evident that Roma ethnicity was assigned to Ferentari’s residents and the spaces they inhabited by the officials. However, as well as this ‘hetero-attribution of Roma ethnicity to poor Bucharesters’, the narrative also revealed a strong racialisation of the Gypsy. ‘Lazy’, ‘stubborn’, ‘uneducated’, ‘auto-segregating’, and ‘unreliable’ are just a selection of the characteristics attributed to this imaginary group of ‘urban Roma’ by the interviewed officials. Racialisation should not be underestimated in Romania’s decentralised policy- and decision-making process.

Vermeersch (Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2017), van Baar (Citation2011, Citation2018), and Kóczé (Citation2018) have theorised about Romaphobia and public governance in the EU. Their studies have established the limits and risks of the Europeanisation process in relation to local efforts to facilitate Roma inclusion. For instance, Vermeersch specified (Citation2017) that in the Europeanisation process, a substantial legal and political framework for ‘European citizenship’ is missing. Although the EU has identified several policy fields as relevant to Roma inclusion (i.e. housing, health care, education, and employment), it also continues to allow full national autonomy in identifying and addressing the issues on the ground. Within this loose structure, numerous Eastern European local administrations frame their Roma communities as European and the majority groups as local. Given a neoliberal logic about the role of local government, racialisation of the Roma entitles politicians to argue that no or limited responsibility ought to be taken for the ‘transnational Roma minority’.

As discussed in the previous subsection, in Ferentari, local housing issues are to be reported by local authorities to the Bucharest development region. On top of the major structural funds, additional regional EU development funds can be tapped directly by local authorities—but only to complement larger applications with ‘soft measures’ such as vocational training. It is not unthinkable that, in Ferentari, local administrative willingness to undertake laborious poverty reduction projects is significantly diminished by Romaphobia and alienation from Sector 5’s ‘Gypsies’.

This assertion brings us back to the same ‘blunt’ official whose words I quoted earlier in this article, because he illustrates very clearly how the socioeconomic and housing-related problematics of the ‘Gypsies in Ferentari’ are overwhelmingly regarded as a European affair:

‘Just as the Americans did with the Mexicans, we need to invent unqualified work for Roma [across Europe]. Invite them and ask what they would most like to produce. My suggestion would be to let them produce fruit baskets, as they did under Ceauşescu … The kids, on the other hand, need good education. Let them learn French or German and read all the poems you have over there … and in three to four generations you’ll have well-educated Roma.’ (Interview, March 2014)

Although his proposal is obviously racist and colonialist, it is telling in two other ways. On one hand, it transfers responsibility for policymaking from the local level (Sector 5) to the EU. Second, it relates in a striking way to one of RUF’s employment proposals: the ‘creation of a Roma handcraft centre’ (meşteşug tradiţional). In this future centre, traditional Roma crafts can be deployed: ‘The Kaldaresh Roma can work as smiths; the Fierari can produce tools, etcetera’ (Sector Citation5 Citation2017, 97, author’s translation). This project will very likely not contribute to lift the thousands of poor Roma inhabitants out of poverty, nor is it rooted in local desires. While the project can be criticised for its limited impact, it can also be contrasted to the long-standing needs expressed by Ferentari’s residents.

In that sense, the plan to build a ‘Roma handicraft centre’ reveals both the racialised interpretation of Roma economic activities and the much broader and long-standing lack of interest in engaging with the local situation. Even if national or European funds are obtained, better multi-scalar collaboration and increased local involvement in decision-making are no guarantee of inclusive policies, though they can enable more and much awaited public funds to flow into areas of Bucharest where the needs are greatest. However, the considerable human resources needed to direct funds towards poverty reduction and to actively engage with local impoverished communities are, arguably, not stimulated by a context in which racism and distrust of ‘Gypsies’ is so openly expressed. Hence, also racism can aggravate the ultimate outcome of local politics when decentralisation is carried out incautiously. It can single out minorities and, thus, threaten urban democracy.

Conclusion

In the postsocialist period, decentralisation started under EU pressure. Initially, this was implemented in a chaotic and unplanned way (Profiroiu, Profiroiu, and Szabo Citation2017), and as a result, local authorities were able to carry out only a limited number of tasks in the 1990s. Following Romania’s EU accession, public expenditures rose again, empowering deprived local authorities. However, due to poor financial management, lack of expertise, and patronage networks, revitalisation programmes for poor districts and social investments were largely neglected (Ion Citation2014).

Though the case of Ferentari is well aligned with the above description, I also sought to reflect on the case using Mark Purcell’s local trap concept. In various ways, local-scale governance has proven problematic in Bucharest. To start, the existing social housing provision differs between sectors in Bucharest. There is also no consideration of the much higher number of social housing applicants in Sector 5 (Ghiţă et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, it is telling that the discussed policy documents from both city hall and Sector 5 lack clear and realistic statements about how the needs of Ferentari’s poor households will be met and how housing affordability will increase. One can certainly argue that this is due to a lack of funding, but that argument is only partially true. The reality is that Romania’s absorption of EU funds is low, and on top of that, large portions of the budgets are earmarked for large infrastructural budgets that disregard social cohesion. As such, the promotion of the economy clearly outweighs the long-standing needs of Bucharest’s poorest groups. Moreover, serious engagement with Ferentari’s residents has never been attempted. One plan, RUF, was made to address the impoverished ‘40,000’, but this group was never directly involved in discussions of how to spend future budgets for the neighbourhood. The reason for this is difficult to determine, but here I remind the reader that this same group was heavily racialised and distrusted by the interviewed officials. One could also conclude, at least hypothetically, that the racialisation of Romanian Roma makes the realisation of neoliberal principles easier for local administrations, which use racial prejudice to justify the passivity of the local state towards an extremely pauperised population.

In conclusion, what this case shows is that, although all actual housing procedures and future projects will be planned and implemented at the local level, this does not mean that this is the right scale. It can be stated that the actual local institutions are ill prepared for such a gigantic task, as Mr Richard suggests, and that therefore funds are not used for pressing social needs. It can also be argued that the process is not ‘localised’ enough, and I have noted that the voices of the ‘local Gypsies’ are deliberately excluded from local policymaking. These findings offer thereby important evidence of the problem with assuming that decentralisation will (automatically) lead to more positive outcomes.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my respondents, especially to Richard Jérôme, Petre Florin Manole, Liviu Chelcea, and Cătălin Berescu for giving their time and consideration to this study. Without them it would have been much harder to research a very opaque side of Bucharest’s local governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

ORCID

Dominic Teodorescu http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8287-2213

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dominic Teodorescu

Dominic Teodorescu recently obtained his PhD at the Uppsala University and is now a fixed-term lecturer at Uppsala University’s Social and Economic Geography Department. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Bucharest has a two-level governance structure with a city hall and six administrative units, called sectors (sectoare).

2 Roma comprised 1.27% of Bucharest’s total population and 2.57% of Sector 5’s population in 2011, though these figures are greatly underestimated. Sector 5’s master plan for Ferentari (Regenerare Urbană Ferentari, RUF; see Sector Citation5 Citation2017, 67–68) presents ethnic statistics for six of the seven most deprived areas of Ferentari. In these areas, 85.6% of the residents (or 19,628) are identified as Roma.

3 The two officials from city hall were part of a group of nine that together form the Urban Planning Commission. Sector 5 has no such commission. In a recent report (https://www.oar-bucuresti.ro/documente/sedinte_ctatu/2017-03-29/CTATU-2017-03-29.pdf) from the Urban Planning Commission, complaints are raised about receiving development requests from Sector 5 due to incompetence: ‘People continue being sent to the ‘Big’ city hall, as no specialised commission exists in Sector 5’. The five people I spoke with from Sector 5 include a large part of the staff involved in urban planning (Direcţia Arhitect Şef) and housing policy (Direcţia Generală Operaţiuni).

4 All officials are identified by letters: officials A and B are city hall planners; officials C to G are employed in Sector 5, C in public works, D in social assistance, E and F in public works, and G in urban planning.

5 In 2019, 27% of the city hall’s budget was earmarked for large investment projects and infrastructure, while only 9% would go to social assistance. See Proiectul de Buget al Municipiului Bucuresti pe anul 2019.

6 Romania has eight development regions. Of these, seven are ‘less developed’ while one, Bucharest-Ilfov, is classified as ‘more developed’. The governing council of a region is not directly elected; instead, it is appointed by the presidents and representatives of the counties and municipalities, respectively, that are part of the development region. The development regions correspond to the NUTS-2 level of the European statistics system (Profiroiu, Profiroiu, and Szabo Citation2017).

7 The ANL was ‘charged with the task of providing housing to certain disadvantaged groups with fewer chances on the housing market and that had not benefited from the earlier large-scale privatisation. The planned dwellings were to be sold with convenient mortgages, while the rentals were also to be subject to right-to-buy schemes in the future … With only 31,000 new public housing units built, 400 of which were for poor Roma households, ANL failed to increase housing affordability.’ (Teodorescu Citation2019, 29)

8 All sectors have autonomous budgets: Sector 1 has the largest one, while Sector 5 has the smallest.

9 PPP stands for public–private partnership.

10 This official refers to two centrally-located blocks of apartments used for emergency housing. The total number of social housing in Sector 5 is unknown to him or his colleagues and not made public either. Also the public housing administration (AFI) does not provide these figures.

References

- Amann, Wolfgand, Ioan Bejan, and Alexis Mundt. 2013. “The National Housing Agency–A Key Stakeholder in Housing Policy.” In Social Housing in Transition Countries, edited by József Hegedüs, Nora Teller, and Martin Lux, 210–223. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Arpagian, Jasmine, and Stuart C. Aitken. 2018. “Without Space: The Politics of Precarity and Dispossession in Postsocialist Bucharest.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2): 445–453. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1368986.

- Attoh, Kafui A. 2011. “What Kind of Right is the Right to the City?” Progress in Human Geography 35 (5): 669–685. doi:10.1177/0309132510394706.

- Berescu, Cătălin, Mina Petrović, and Nora Teller. 2013. “Housing Exclusion of the Roma. Living on the Edge.” In Social Housing in Transition Countries, edited by József Hegedüs, Nora Teller, and Martin Lux, 98–116. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Calciu, Daniela. 2016. “Memories and the City, Heritage and Urbanity.” In Space and Time Visualisation, edited by Maria Boştenaru-Dan, and Cerasella Crăciun, 113–124. Cham: Springer.

- Chelcea, Liviu, and Ioana Iancu. 2015. “An Anthropology of Parking: Infrastructures of Automobility, Work, and Circulation.” Anthropology of Work Review 36 (2): 62–73. doi:10.1111/awr.12068.

- Chelcea, Liviu, Raluca Popescu, and Darie Cristea. 2015. “Who are the Gentrifiers and How Do They Change Central City Neighbourhoods? Privatization, Commodification, and Gentrification in Bucharest.” Geografie 120 (2): 113–133.

- Chelcea, Liviu, and Gergő Pulay. 2015. “Networked Infrastructures and the ‘Local’: Flows and Connectivity in a Postsocialist City.” City 19 (2-3): 344–355. doi:10.1080/13604813.2015.1019231.

- Clapp, Alexander. 2017. “Romania Redivivus.” New Left Review 108: 5–41.

- Creţan, Remus, and Ryan Powell. 2018. “The Power of Group Stigmatization: Wealthy Roma, Urban Space and Strategies of Defence in Post-socialist Romania.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (3): 423–441. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12626.

- Csepeli, György, and Dávid Simon. 2004. “Construction of Roma Identity in Eastern and Central Europe: Perception and Self-identification.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (1): 129–150. doi:10.1080/1369183032000170204.

- Dobre, Ana M. 2010. “Romania: From Historical Regions to Local Decentralization via the Unitary State.” In The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe. https://search.crossref.org/?q=10.1093%2Foxfordhb%2F9780199562978.003.0030#.

- Geddes, Mike. 2005. “Neoliberalism and Local Governance–Cross-National Perspectives and Speculations.” Policy Studies 26 (3-4): 359–377. doi:10.1080/01442870500198429.

- Ghiţă, Alexandru F., Ciprian Ciucu, Alexandru Damian, Alexandra Toderiţă, Roxana Albişteanu, and Popescu. Ruxandra. 2016. Policy Paper Nr. 1 / Ianuarie 2016: Locuirea socială în Bucureşti. Între lege şi realitate. Accessed December 10, 2018 www.cdut.ro.

- Goodwin, Mark, and Joe Painter. 1996. “Local Governance, the Crises of Fordism and the Changing Geographies of Regulation.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 21 (4): 635–648. doi:10.2307/622391.

- INS (National Institute of Statistics). 2016. Dimensiuni ale incluziunii sociale în România. Bucharest: Institutul Naţional de Statistică. Accessed August 10, 2017. http://www.insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/dimensiuni_ale_incluziunii_sociale_in_romania_1.pdf.

- Ion, Elena. 2014. “Public Funding and Urban Governance in Contemporary Romania: The Resurgence of State-led Urban Development in an Era of Crisis.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7 (1): 171–187. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst036.

- Jessop, Bob. 1999. “The Changing Governance of Welfare: Recent Trends in its Primary Functions, Scale, and Modes of Coordination.” Social Policy and Administration 33 (4): 348–359. doi:10.1111/1467-9515.00157.

- Jessop, Bob. 2005. “The Political Economy of Scale and European Governance.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 96 (2): 225–230. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00453.x.

- Jessop, Bob, Neill Brenner, and Martin Jones. 2008. “Theorizing Sociospatial Relations.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26 (3): 389–401. doi:10.1068/d9107.

- Kóczé, Angéla. 2018. “Race, Migration and Neoliberalism: Distorted Notions of Romani Migration in European Public Discourses.” Social Identities 24 (4): 459–473. doi:10.1080/13504630.2017.1335827.

- Lancione, Michele. 2017. “Revitalising the Uncanny: Challenging Inertia in the Struggle Against Forced Evictions.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35 (6): 1012–1032. doi:10.1177/0263775817701731.

- Lancione, Michele. 2019. “The Politics of Embodied Urban Precarity: Roma People and the Fight for Housing in Bucharest, Romania.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 101: 182–191. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.008.

- Light, Daniel, and Craig Young. 2015. “Public Space and the Material Legacies of Communism in Bucharest.” In Post-Communist Romania at 25, edited by Lavinia Stan, and Diane Vancea, 41–62. Lanham: Lexington.

- Marcińczak, Szymon, Michael Gentile, Samuel Rufat, and Liviu Chelcea. 2014. “Urban Geographies of Hesitant Transition: Tracing Socioeconomic Segregation in Post-Ceauşescu Bucharest.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (4): 1399–1417. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12073.

- Marin, Vera, and Liviu Chelcea. 2018. “The Many (Still) Functional Housing Estates of Bucharest, Romania: A Viable Housing Provider in Europe’s Densest Capital City.” In Housing Estates in Europe, edited by Daniel Baldwin Hess, Tiit Tammaru, and Maarten van Ham, 167–190. Cham: Springer.

- Nae, Mariana, and David Turnock. 2011. “The New Bucharest: Two Decades of Restructuring.” Cities 28 (2): 206–219. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.04.004.

- O’Neill, Bruce. 2010. “Down and Then Out in Bucharest: Urban Poverty, Governance, and the Politics of Place in the Postsocialist City.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (2): 254–269. doi:10.1068/d15408.

- O’Neill, Bruce. 2014. “Cast Aside: Boredom, Downward Mobility, and Homelessness in Post-Communist Bucharest.” Cultural Anthropology 29 (1): 8–31. doi:10.14506/ca29.1.03.

- O’Neill, Bruce. 2017. “The Ethnographic Negative: Capturing the Impress of Boredom and Inactivity.” Focaal 78: 23–37. doi:10.3167/fcl.2017.780103.

- PMB (Primăria Municipiului Bucureşti). 2011. Conceptul Strategic Bucureşti. Bucharest: PMB.

- Powell, Ryan, and John Lever. 2017. “Europe’s Perennial ‘Outsiders’: A Processual Approach to Roma Stigmatization and Ghettoization.” Current Sociology 65 (5): 680–699. doi:10.1177/0011392115594213.

- Profiroiu, Constantin M., Alina G. Profiroiu, and Septimu R. Szabo. 2017. “The Decentralization Process in Romania.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Decentralisation in Europe, edited by José Ruano, and Marius Profiroiu, 353–387. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pulay, Gergő. 2015. “The Street Economy in a Poor Neighbourhood of Bucharest.” Gypsy Economy: Romani Livelihoods and Notions of Worth in the 21st Century 3: 127–144.

- Purcell, Mark. 2002. “Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant.” GeoJournal 58 (2-3): 99–108. doi:10.1023/B:GEJO.0000010829.62237.8f.

- Purcell, Mark. 2006. “Urban Democracy and the Local Trap.” Urban Studies 43 (11): 1921–1941. doi:10.1080/00420980600897826.

- Purcell, Mark. 2013. “The Right to the City: the Struggle for Democracy in the Urban Public Realm.” Policy and Politics 41 (3): 311–327. doi:10.1332/030557312X655639.

- Rughiniş, Cosima. 2010. “The Forest Behind the Bar Charts: Bridging Quantitative and Qualitative Research on Roma/Ţigani in Contemporary Romania.” Patterns of Prejudice 44 (4): 337–367. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2010.510716.

- Sector 5. 2017. Regenerare Urbană Ferentari. Bucharest: Sector 5. Accessed August 10, 2017. http://www.sector5.ro/media/2763/ruf-cld.pdf.

- Şoaită, Adriana M. 2017. “The Changing Nature of Outright Home Ownership in Romania: Housing Wealth and Housing Inequality.” In Housing Wealth and Welfare, edited by Caroline Dewilde, and Richard Ronald, 236–257. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- StudioBASAR. 2010. Evicting the Ghost: Architecture of Survival. Bucharest: Centrul de Introspecţie Vizuală.

- Surubaru, Neculai-Cristian. 2017. “Administrative Capacity or Quality of Political Governance? EU Cohesion Policy in the New Europe, 2007–13.” Regional Studies 51 (6): 844–856. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1246798.

- Teodorescu, Dominic. 2018. “The Modern Mahala: Making and Living in Romania’s Postsocialist Slum.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 59 (3-4): 436–461. doi:10.1080/15387216.2019.1574433.

- Teodorescu, Dominic. 2019. “Dwelling on Substandard Housing: A Multi-site Contextualisation of Housing Deprivation among Romanian Roma.” PhD diss., Uppsala University.

- Tosics, Ivan. 2016. “Integrated Territorial Investment: a Missed Opportunity?” In EU Cohesion Policy, edited by John Bachtler, Peter Berkowitz, Sally Hardy, and Tatjana Muravska, 284–296. Abingdon: Routledge.

- van Baar, Huub. 2011. “Europe’s Romaphobia: Problematization, Securitization, Nomadization.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (2): 203–212. doi:10.1068/d2902ed1.

- van Baar, Huub. 2018. “Contained Mobility and the Racialization of Poverty in Europe: The Roma at the Development–Security Nexus.” Social Identities 24 (4): 442–458. doi:10.1080/13504630.2017.1335826.

- Vermeersch, Peter. 2011. “Europeanisering en de Roma: op zoek naar maatschappelijke inclusie in een nieuwe politieke en institutionele contekst.” Tijdschrift voor Sociologie 3 (4): 414–436.

- Vermeersch, Peter. 2012. “Reframing the Roma: EU Initiatives and the Politics of Reinterpretation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (8): 1195–1212. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2012.689175.

- Vermeersch, Peter. 2017. “How Does the EU Matter for the Roma? Transnational Roma Activism and EU Social Policy Formation.” Problems of Post-Communism 64 (5): 219–227. doi:10.1080/10758216.2016.1268925.

- Vincze, Eniko. 2018. “Ghettoization: The Production of Marginal Spaces of Housing and the Reproduction of Racialized Labour.” In Racialized Labour in Romania: Spaces of Marginality at the Periphery of Global Capitalism, edited by Eniko Vincze, Norbert Petrovici, Cristina Raţ, and Giovanni Picker, 63–96. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vincze, Eniko, and Cristina Rat. 2013. “Spatialization and Racialization of Social Exclusion. the Social and Cultural Formation of ‘Gypsy Ghettos’ in Romania in a European Context.” Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai 58 (2): 5–21. doi: 10.5038/1937-8602.58.2.1

- Vincze, Eniko, and George I. Zamfir. 2019. “Racialized Housing Unevenness in Cluj-Napoca Under Capitalist Redevelopment.” City 23 (4–5): 439–460. doi:10.1080/13604813.2019.1684078.

- Zamfirescu, Irina M. 2015. “Housing Eviction, Displacement and the Missing Social Housing of Bucharest.” Calitatea vieţii 26 (2): 140–154.