Abstract

Objectives

Informal caregivers of people living with dementia (ICPDs) experience stressors that can lead to adverse outcomes. Although apps for ICPDs are available, evidence to support their effectiveness is limited. This investigation was aimed at providing an evaluation of available apps for ICPDs.

Methods

We conducted two studies: 1) search and evaluation of available apps; and 2) controlled trial of two apps identified in the Study 1 (NCT05217004). For Study 2, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two app-using groups or a control group. Outcome measures were administered before, post-intervention, and at a follow-up. Interviews with caregivers were conducted to examine their needs regarding the development of future apps.

Results

Sixteen apps were examined in Study 1. Results suggest that the number and type of features present in each app may not be sufficient to address the multifaceted needs of ICPDs. In Study 2, contrary to expectation, we did not identify differences between the app-using and control conditions on our outcome measures. Participants noted several content and user-experience needs to consider in developing new apps.

Conclusion

Findings from the investigation can inform future developments of apps to address the needs of ICPDs.

Keywords:

Introduction

Innovations in mobile health can improve the delivery of and access to interventions for caregivers of people living with dementia. The global prevalence of dementia is projected to increase to 65 million people by 2030 (Prince et al., Citation2013). This rise will result in a proportional increase in the number of people caring for individuals living with dementia. Informal caregivers of people living with dementia (ICPDs) experience higher levels of stress than other caregivers (Riffin et al., Citation2017; Sheehan et al., Citation2020). Understanding the factors that may ameliorate caregiver burden and stress among ICPDs is paramount.

The needs of caregivers are multidimensional. Moreover, expressions of unmet needs of ICPDs are associated with negative outcomes (Rosa et al., Citation2010). Although still in their infancy, efforts to deliver interventions for ICPDs through mobile app formats have aimed to address the needs for support and objective demands experienced by caregivers (e.g. Núñez-Naveira et al., Citation2016; Thorpe et al., Citation2019). Further studies about mobile health interventions for caregivers are warranted as little is known about the scope and effectiveness of publicly available apps for ICPDs.

The ubiquitous nature and expanded use of smartphones have led to a proliferation of apps (MindSea, Citation2021). Brown et al. (Citation2019) and Wozney et al. (Citation2018) searched available apps for ICPDs and failed to identify any that had been subjected to controlled evaluation or were rigorously tested. Although Brown et al. (Citation2019) and Wozney et al. (Citation2018) described the features and content of available apps, the extent to which apps address the needs of caregivers remains unclear. Moreover, a lack of research evaluating the needs and experiences of caregivers in using available apps is apparent (Wozney et al., Citation2018). The purpose of this investigation was to provide a review and evaluation of currently available apps for ICPDs. We conducted two studies: 1) a search and quality assessment of available apps (Study 1); and 2) a clinical trial evaluation of two selected apps identified in Study 1 and interviews with ICPDs (Study 2). Detailed methodologies of each of the two studies are outlined in Supplementary file 1.

Study 1

Methods

Search strategy

Searches of apps on Google Play and Apple’s App store were conducted to ensure that both IOS and Android operating systems were covered. These app stores were searched individually by two coders using the following search terms: ‘caregiver, dementia’, ‘caregiver, Alzheimer’s’, ‘caregiver, dementia, stress’, and ‘caregiver, dementia, burden’. During the initial screen, the coders excluded apps if their descriptions did not explicitly indicate that the app was developed for ICPDs. As such, apps that provided general information about dementia (i.e. no mention of caregivers) or apps that provided information for caregivers in general (i.e. did not specify that they related to dementia) were excluded. To be included in the review, an app needed to: 1) have been developed specifically for ICPDs; 2) address either care-related needs of the care-recipient or the needs of the caregiver; and 3) be operable without the use of a second device (e.g. smartwatch). We defined care-related needs and caregiver needs based on the categories identified by McCabe et al. (Citation2016; i.e. care recipient needs and caregivers’ needs) in their review. Our inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Supplementary file 2.

Content analysis and quality assessment

All the apps meeting criteria were downloaded and analyzed. Two researchers conducted the content analysis and quality assessment. First, the coders independently examined a randomly selected 30% of apps to code prevalent features, content, and quality as noted for each component below. They then met to finalize the coding scheme and applied it to 30% more of the apps in order to ensure consistency. Communication between the researchers was ongoing and discrepancies between them were discussed. The primary coder coded 10 of the 16 apps, while the secondary coder coded the remaining apps. To establish reliability, a randomly selected subset of the apps, coded by both coders, was examined. Cohen’s Kappa and intraclass coefficient (ICC) were calculated to assess interrater reliability.

App features and content

The coders independently examined a subset of apps to note prevalent app features and code each identified feature in relation to the broad categories specified by McCabe et al. (Citation2016): care-related needs (e.g. assisting with caring for the person living with dementia) and caregiver’s personal needs (e.g. psychological health needs).

Assessment of consistency with theoretical frameworks

The features of each app were assessed based on consistency with the components found in theoretical frameworks of stress: Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping and Pearlin et al. (Citation1990) Stress Process Framework. The frameworks are complementary, and the identified apps were assessed based on whether they address the components found in the two frameworks: 1) coping strategies; 2) social support; 3) objective indicators of stress; 4) subjective indicators of stress); and 5) background and context of stress. Apps were rated based on the presence of each component (i.e. Present =1 and Not Present = 0) and a total score was calculated for each identified app.

Quality assessment

Each app was assessed using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS; Stoyanov et al., Citation2015). The MARS is a 23-item questionnaire designed to assess the quality of mHealth applications. Each item was rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (inadequate) to 5 (excellent). An overall mean and subscale scores are obtained with higher scores indicating more positive perceptions.

Results (Study 1)

App search

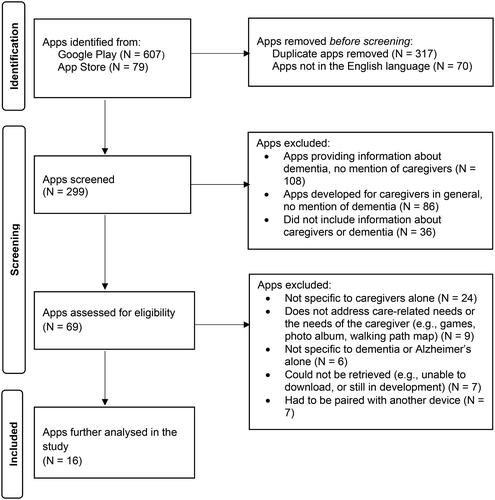

The final search flow is outlined in . We identified 686 apps. Reliability analysis was conducted for a randomly selected 35% of the searched and screened apps to ensure agreement between the two coders. Agreement between the two coders was satisfactory (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.73, p < 0.01). After exclusion of apps that were not specific to dementia caregivers and did not provide features related to caregiver needs, 16 apps met criteria. The characteristics of the apps are outlined in Supplementary file 2.

Content analysis

App features

Nine features emerged from the content analysis: 1) Information on dementia and care management; 2) information on caregiver well-being; 3) external/additional resources; 4) behavior/symptom management and monitoring; 5) task and appointment scheduling; 6) stress management strategies; 7) social networking; 8) task coordination with other care providers; and 9) medication management. The intercoder reliability was satisfactory for the app features (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.73, p < 0.01) and excellent for the total number of features (ICC = 0.95, p < 0.01). The occurrences of specific app features are summarized in . The apps had an average of 3.56 (SD = 1.93) features.

Table 1. Frequency of app features.

Assessment of consistency with a theoretical framework

The frequencies of the various components as they relate to the two theoretical frameworks of stress (i.e. Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping and Stress Process Framework) are summarized in Supplementary file 2. The reliability between the two coders was established (ICC = 0.80, p < 0.01). The mean number of components present in each app was 3.13 (SD = 0.81).

Quality assessment

outlines the mean subscale and overall app quality scores. The reliability between the two coders for each subscale and the overall app quality ranged from 0.78-0.90. The Engagement subscale was rated lowest across all subscales. Within the Information subscale, three of the 16 apps (e.g. Dementia Advisor, Alzheimer’s Daily Companion, DementiAssist) were noted to have some evidence (e.g. usability, app characteristics) in support of the app outlined in the literature (Brown & Kim, Citation2019; Krauskopf & Golden, Citation2016; Wozney et al., Citation2018). None of the apps identified, to our knowledge, had been subjected to controlled empirical evaluation.

Table 2. Means (SDs) of app quality ratings.

Discussion (Study 1)

Given the proliferation and ever-growing number of apps with a variety of goals, we conducted an updated search of apps for ICDPs. Although several hundred apps for caregivers are available, only a small fraction these, have been specifically designed for ICDPs. That is, only 16 apps met our inclusion criteria for a specific focus on dementia care. The most common features in the apps were provision of information on care management. Nonetheless, the information that the apps provide is limited and a caregiver would likely exhaust the content in a short amount of time. Moreover, this limited number and type of features would likely not be sufficient to address the multifaceted needs of ICPDs (McCabe et al., Citation2016). Most of the app features are related to managing the care recipient needs (e.g. symptom monitoring, medication management). A small subset of apps focused on the personal needs of the caregiver (e.g. stress management, social networking) and within this, only a few included activities (e.g. journaling, breathing exercises) that the caregiver could engage in to manage stress.

Apps were also evaluated based on whether they included components (e.g. coping strategies, social support, objective and subjective indicators of stress, and context of stress) found in theoretical frameworks of stress. Consistent with Pearlin et al. (Citation1990) and Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), most of the apps reviewed in the study included features that provided strategies to cope with provision of care or caregiver well-being. This coincided with the features identified in the content analysis, such as information about dementia and managing care. A majority of the apps also addressed objective and subjective indicators of stress by providing features such as information about the etiology of dementia and emotional well-being. A key element missing from the apps but important in Pearlin et al.’s (Citation1990) framework, was consideration of the context of stress (e.g., relation with the care recipient and gender).

In terms of the MARS app quality ratings, overall app quality was acceptable. This is consistent with the MARS quality scores identified by Brown et al. (Citation2019). In examining each subscale of the MARS, apps had low engagement scores highlighting potential areas for improvement. The lower degree of interactivity in current apps is concerning given that uninteresting and disengaging apps may be less utilized. Since mobile apps rely heavily on user involvement and self-direction, low engagement can impact the effectiveness of apps. None of the apps identified, to our knowledge, had been subjected to controlled empirical evaluation. With the growing field of mHealth, there is a corresponding need for efficacy studies for commercially available apps.

Limitations

We conducted our search for the apps in November and December 2021. Given the proliferation of apps on the market, any more recently developed relevant apps would have been excluded. Moreover, apps were excluded if they were not tailored for ICPDs. Perhaps a broader investigation of available apps for caregivers could delineate features that may be beneficial to dementia caregivers.

Study 2

Methods

Study 2 was approved by our institutional ethics review board (#2021-177). It focused on testing the efficacy of apps developed for ICPDs in comparison to a control group on various outcome measures. Two apps were selected from the apps identified in Study 1. The evaluation study was registered as a clinical trial through clinicaltrials.gov: NCT05217004.

App selection

Of the 16 apps meeting Study 1 inclusion criteria, two apps were selected for Study 2 based on: 1) content (whether or not the app included a stress management feature); 2) MARS quality rating; and 3) consistency with theoretical frameworks of stress score. Accordingly, one app was chosen from each group (i.e. with vs. without a stress management component) with the highest overall mean score.

The scores of the three highest scoring apps for each group are outlined in Supplementary file 2. The Dementia Talk (App 1) app provides users with information about dementia and allows users to track the frequency and intensity of an observed behavior. It also provides activities related to stress and its management. The CLEAR Dementia Care app (App 2) provides information about dementia, offers suggestions and alternative approaches to various care-related situations, and allows users to record the frequency of observed behaviors.

Participants

Power analyses using G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2009) indicated that a sample size of 108 participants would provide more than adequate power for all main analyses of this investigation assuming medium effects with 1-beta set at .80 and alpha level at .05. Inclusion criteria were the following: 1) living in Canada or the United States; 2) providing informal/unpaid care; 3) providing primary care (i.e. care recipient is currently not living in a long-term care facility); 4) own a smartphone; and 5) not currently using an app for caregiver stress/burden. All participants provided informed consent. They were recruited primarily via online advertisements and were compensated for their participation (i.e. up to $75 for participation). Detailed information on our recruitment approach has been added to Supplementary file 1.

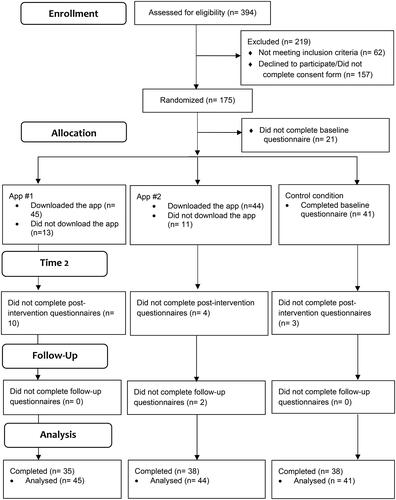

shows the flow and assignment of participants into conditions. All participants (n = 175) completed a consent form. Of those who completed the baseline questionnaire and were provided instructions based on their group assignment, 45 and 44 participants downloaded the app in the App 1 and App 2 conditions respectively (i.e. started the intervention) and 41 in the control group. As such, a total of 130 participants started the intervention and their data were analysed consistent with intent-to-treat methods. Nineteen participants (10 in App 1; 6 in App 2, 3 in the control) were lost at Time 2 and follow-up. Accordingly, 111 participants completed the entire study. The demographic characteristics of the participants are outlined in .

Figure 2. Flow diagram of the participants included in the study. App 1 = Dementia Talk app; app 2 = CLEAR Dementia Care. Time 2 = after the 2-week period.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics for the app-using and control conditions.

Measures

Dementia knowledge assessment tool Version 2 (DKAT2)

Knowledge about dementia was assessed using the DKAT2 (Toye et al., Citation2014). DKAT2 is a valid and reliable 21-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess knowledge about dementia among caregivers and health-care staff. (Toye et al., Citation2014). In this study, the internal consistency of the measure was 0.75.

Short-form health survey-12 (SF-12)

We used the SF-12 (Version 1) (Ware et al., Citation1996). The SF-12 is a reliable and valid questionnaire that measures overall health (e.g. physical and mental) (Montazeri et al., Citation2009). In this study, the internal consistency of the scale was 0.24. Due to the low internal consistency, this measure was not included in the main analysis.

Perceived stress scale-10 (PSS-10)

Perceived stress over the course of the intervention was assessed using the PSS-10 (Cohen et al., Citation1983). The PSS-10 is a reliable and valid 10-item questionnaire designed to measure general feelings of stress and overload in the past four weeks (Nielsen et al., Citation2016). In this study, the internal consistency of the measure was 0.88.

Zarit caregiver burden interview (ZBI)

The ZBI (Zarit et al., Citation1985) is a reliable and valid 22-item questionnaire designed to measure the burden experienced in various dimensions life as a result of caregiving (Yap, Citation2010). In this study, the internal consistency of the measure was 0.94.

System usability scale (SUS)

The SUS (Brooke, Citation1996) is a reliable and valid 10-item questionnaire designed to efficiently assess the usability of a technology or product (Bangor et al., Citation2008). In this study, the internal consistency of the measure was 0.36.

Subjective app quality rating

The subjective quality section (4 items) of the MARS (Stoyanov et al., Citation2015) was used to assess users’ overall satisfaction with their app. The MARS has good concurrent validity and reliability (Terhorst et al., Citation2020). In this study, the internal consistency of the measure was 0.82.

Procedure

Prospective participants completed an eligibility screen to assess the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study. Procedure descriptions were provided to eligible participants as part of the consent process. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions: 1) App #1 group; 2) App #2 group; and 3) control group. They were asked to complete the demographics questionnaire and baseline measures (e.g. PSS-10, DKAT2, ZBI, SF-12). Participants were given the option to complete the measures online using the Qualtrics (Version 10) platform or to be mailed printed versions of the measures. All participants completed the questionnaires online. Participants in the app-using groups were asked to download the selected app on their mobile phones. A short video tutorial on how to use and download the app was provided to each participant. Participants were asked to indicate that they felt confident in using the app prior to commencing the app-use period. They were asked to use the app for at least an hour per week over a two-week period. To encourage compliance, participants in all groups were asked to complete a weekly diary questionnaire. Participants in the app-using groups recorded the time they spent using the app per week. Participants in the control group reported if they had sought information on care management. The same measures were completed after the intervention period (i.e. two weeks) and at a follow-up period (i.e. three weeks after the end of the intervention period). Participants in the two app-using groups were also asked to complete the SUS and MARS after the intervention period. A randomly selected subsample was invited to participate in a semi-structured interview over Zoom/phone.

Analyses

Multiple imputation

Intent to treat methods were employed to account for participants who were lost at Time 2 and follow-up periods (McCoy, Citation2017). Multiple imputations were used to account for missing responses using predictive mean matching (Jakobsen et al., Citation2017; Kleinke, Citation2017; McCoy, Citation2017). For each outcome measure, estimates from the imputation models were collated and averaged to obtain data points for missing data (Baranzini, Citation2018).

Group comparisons

To test whether app-using participants would improve overtime in comparison to the control group, a 3 between (group: App #1, App #2, control) x 3 within (time: baseline, post, follow-up) mixed-model multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted with PSS-10 and ZBI scores as the dependent variables. Univariate repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to determine significant main and interaction effects for specific variables.

Thematic analysis

Textual data from the semi-structured interviews with ICPDs were examined using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022; Vaismoradi et al., Citation2016). Our approach followed a coding reliability thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). As such, our analytic procedures were oriented to establishing agreement of data coding grounded by a post-positivist perspective (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Two independent researchers initially organized 30% of data into clusters based on commonalities and recurring ideas to develop a coding book (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Discrepancies between the researchers and decisions to merge or split categories were communicated throughout the process. Each coder coded half of the remaining data. The developed coding book was then applied to the rest of the data to identify prevalent categories and obtain a frequency count of the identified themes.

Results (Study 2)

Quantitative analysis

Group differences

There were no baseline group differences on the outcome measures. The descriptive statistics for the dependent variables for the main analyses are summarized in Supplementary file 2. The repeated measures MANOVA indicated that the within-subjects main effect of time on the combined dependent variables (PSS-10, ZBI) was significant, F(4, 124) = 4.67, p < 0.01, Wilks’ λ = 0.87, partial η2 = 0.13. The between-subjects effect of group and group x time interaction were not significant.

Follow-up repeated measures ANOVAs for each variable examined the main effect of time. The effect of time for PSS-10 was significant, F(2, 126) = 8.18, p < 0.01, Wilks’ λ = 0.89, partial η2 = 0.12. Baseline perceived stress scores were higher in comparison to the Time 2, 1.55, 95% CI (0.80, 2.31), p < 0.01, and follow-up scores, 1.00, 95% CI (0.12, 1.90), p < 0.01. There were no significant differences in caregiver burden. Univariate analysis was conducted with the DKAT2 dependent variable. There was a significant main effect of time, F(2, 126) = 11.36, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.15. Knowledge about dementia increased at Time 2, −0.59, 95% CI (-0.89, −0.30), p < 0.01, and follow-up periods, −0.73, 95% CI (-1.04, −0.41), p < 0.01, relative to baseline knowledge. There were no other significant effects.

Subjective app ratings and usability

Only participants who downloaded and used app for the two-week period were included in this analysis. Higher app ratings were associated with greater perceived app usability, r (69) = 0.38, p < 0.01, while controlling for comfort with using technology. There were no significant group differences on app ratings, F(1, 71) = 2.29, p > 0.05, and perceived app usability, F(1, 71) = 0.61, p > 0.05.

Time spent using the app

The mean time spent using the app was 67.56 min/week (SD = 56.85) for App 1 and 97.05 min/week (SD = 63.19) for App 2. Sixty eight percent of participants in the control condition reported that they had sought/learned information relating to care management within the two-week period.

Qualitative analysis

A total of 35 participants completed the interview: 10 participants from the App 1 group, 17 participants from the App 2 group, and eight participants from the control group. The interviews covered questions relating to perceptions of using the apps and perceptions of unmet needs that can be met with future mobile health apps for caregivers. The intercoder agreement for each topic was as follows: 1) 0.89 (p < 0.01; app-use); and 2) 0.73 (p < 0.01; future apps).

Experiences in using the app

Two broad categories emerged from this topic: positive and negative aspects of the apps. In general, the comparable frequencies of the themes for each app group indicate that participants noted similar positive aspects and difficulties in using the apps irrespective of their app condition. As such, the themes were discussed together in subsequent sections. See Supplementary file 2 for frequency counts of each theme.

Positive aspects

Three sub-themes emerged as positive aspects of the apps: 1) Informative; 2) visual appeal and layout; and 3) facilitated monitoring of behaviors/symptoms.

A majority of participants in both app conditions indicated that the apps were informative. Positive perceptions regarding the information presented in the apps were coded under this theme. Participants in the App 1 group commented that the strategies provided in the app in relation to care management were helpful. For example, a participant expressed, ‘I think my favorite part was where you had different behaviors and there was like a question mark and then it gave you information about the behaviour’ (App 1). Participants reported that the information presented in the app was comprehensive and would be helpful for caregivers who are in the start of their caregiving journey, ‘I just found it very supportive and informative because I’ve had no experience on this’ (App 2).

Many participants commented on the visual appeal and layout of the apps. Responses commenting on the display or organization of the app were coded under this theme. For example, one participated noted that their ‘first impression [of the app] was that it was beautiful. It’s beautiful, it’s really nice, it was laid out with the colours, so super engaging visually’ (App 2). Other participants expressed that the app was simple and useful. For example, a participant thought that the app ‘was very helpful’ and that ‘it was very easy to navigate around it’ (App 1).

Lastly, participants noted that features within the app facilitated monitoring of behaviors/symptoms in the care recipient. Responses that described how the app features supported their ability to monitor behaviors/symptoms in the care recipient were coded under this theme. For example, a participant noted that ‘there were a number of those behaviors that came up with care plans suggestions, the suggestions were really helpful’ (App 1). Similarly, participants in the App 2 condition noted that the recording behavior tracker allowed them to record patterns in their care recipient’s behaviour. A participant expressed: ‘I reviewed the app and I looked at the information and think well ‘wow’ you know that happened today or I dealt with that Tuesday or something’. You know it kind of comes back and hits you that there is support there and that this is something that is real but it’s something that you can work through’ (App 2).

Negative aspects

Four sub-themes emerged in the negative aspects of the apps noted by participants: 1) Difficulty navigating the app; 2) lack of customization; 3) no added value; and 4) presentation of information.

Participants in both conditions experienced difficulties navigating the app; responses expressing these sentiments were coded under this theme. A few participants described both of the apps as difficult to use and not intuitive, for example, one participant noted: ‘I found it a bit clunky and I’m pretty good at technology’ (App 1). Other participants reported experiencing difficulties using certain features within the app. A few participants in the App 2 group noted difficulties using the behavior tracker feature. For example, ‘the recording behaviors, seriously, I mean, I understand the concept, but…the functionality escaped me. And there were only two behaviors’ (App 2).

Many participants in both app groups also reported that the apps lacked customization. Responses that provided suggestions to expand the utility of the app were coded under this theme. Some participants clearly expressed this need: ‘I would like to see more opportunity to customize the whole thing, and behaviors to look for, patterns to look for what worked; what didn’t work’ (App 1). Other participants noted that the apps were restrictive. For example, a participant reported: ‘I mainly used the behavior log, which I found difficult to use because what I wanted to document wasn’t a choice. I would’ve liked to type in my own questions or at least leave room for others’ (App 2).

Other participants noted that the app did not add value to their caregiver needs. Responses from participants indicating that they did not learn additional information by using the apps were coded under this theme. For instance, some participants expressed that they did not benefit from the app because they already knew most of the information provided in the app, ‘some of the stuff that I was reading like I already knew, since we’d already been through that’ (App 2). Moreover, a participant expressed that ‘the app turned [them] off from the get-go’ and ‘[they] didn’t find utility in it’ (App 1).

A few participants commented on the presentation of information. Comments about missing relevant information in the apps were coded under this theme. A participant in the App 1 group commented that the information provided in the app focused heavily on dementia as a condition, ‘it was very, obviously, [about] dementia, which is okay, but as a caregiver, I have to deal with the whole person’ (App 1). Another participant expressed that an app may not be a sufficient format to deliver resources: ‘I would have rather had a book with that information than an app to read about strategies and on how to deal with some behavioral issues’ (App 1).

Perceptions on the development of future mobile apps

Two broad categories emerged from this topic: 1) Content and feature considerations; 2) and user experience considerations. See Supplementary file 2 for frequency counts of each theme.

Content and feature considerations

Five sub-themes emerged in the features participants expressed were important in the development of apps for caregivers: 1) Connections to other supports; 2) recordkeeping and monitoring; 3) information and tips; 4) strategies to manage stress; and 5) coordination of care.

Many participants expressed that developed apps could facilitate connections to other supports. Responses that expressed the need to include avenues for users to receive support were coded under this theme. For instance, a participant suggested incorporating a ‘live chat built into an app that has some resources attached to it’ and noted that this feature has the potential ‘to build a network of people they can reach out [to]’ (App 1). A few participants noted the need for apps to incorporate features that could help caregivers connect with physicians to ask questions. For example, a participant expressed, ‘what I would have benefited would be like a community of professionals volunteering their time to answer quick questions things like that’ (App 2).

Responses with comments on the need for an app to facilitate recordkeeping and monitoring of the care recipient’s health were coded under this theme. Participants frequently noted that the primary value that apps could provide to caregivers is allowing users to store, record, and make notes on their care recipient’s health. For instance, a participant expressed, ‘the best thing about using an app would be if I was able to write things down’ (Control). As another example, a participant noted that an app could facilitate a ‘case management system’. A participant expressed a need for ‘tracking [the care recipient’s] day-to-day activities’, ‘keeping track of medical appointments’ and ‘somewhere to kind of put all that information, kind of like a central repository’ (App 1). In addition, they expressed that an app could replace the paperwork associated with various notes.

Responses that indicated the need to incorporate pertinent information and tips in future apps were coded under this theme. Participants noted that they would like to see tailored information and strategies based on the caregiver’s experience. As an example, a participant expressed ‘I don’t know if this exist…well let’s say stages, if there are four stages, you know, breaking it down to what resources would be helpful at this stage or at this point’ (App 2).

Participants highlighted the limited number of stress management resources directed to caregivers. Responses outlining strategies to manage stress and self-care activities that could be provided in an app for caregivers were coded under this theme. One participant expressed, ‘you have to take care of yourself. Some reinforcement of tips like a take a five-minute meditation, I think is really important. And [stress] is often the part of caregiving that gets forgotten…you have to stop and take care of yourself to acknowledge, some of those feelings and emotions’ (App 1). Examples of strategies that participants noted could be included in apps include journaling and information about helpful coping strategies. Another participant expressed the value of self-care: ‘relaxation techniques, reminders to think about yourself, like go get a pedicure manicure, you know just leaving the house’ (App 2).

Participants indicated that apps developed for ICPDs could facilitate care by involving the circle of care (e.g. other family members) in using the app. As such, responses that described ways an app could assist in coordination of care were coded under this theme. For example, a participant felt that the benefit of an app could be ‘having a tool to monitor different kind of behaviors or things that the [the care recipient] is experiencing so that other care providers could also be on the same page’ (App 2). Participants also noted that an app in which users could store information about the care recipient and have shared access with other care providers would be helpful. A participant noted that this would be helpful for their situation as a large family facilitating care for a parent, ‘I have two sisters and brothers, we are pretty much in constant contact about who is taking mom food, who has done medication for the day…so I can definitely see the value in it’ (App 1).

User experience considerations

Three sub-themes emerged in participants’ considerations on important user-experience factors in developing new apps: 1) ease of use; 2) layout; and 3) cost.

A majority of the participants noted ease of use as the most important consideration when developing apps for caregivers. For instance, a participant expressed the need to ‘[m]ake sure that it’s user friendly’ and that ‘[they are] fairly computer savvy, but what about people who are not’ (App 2). This could be facilitated by including ‘a summary page [of all the information]’ (App 1). Other participants also noted that with the tasks and challenges experienced by caregivers on a daily basis, an app has to be intuitive and should not add an additional burden, ‘it needs to be really easy because taking care of somebody is already stressful and so something that’s on your fingertips and that’s already laid out. So, when you open it…you don’t have to take 10,000 steps to get to it’ (App 2). To facilitate this, participants suggested providing a video tutorial on how to use the app or providing technical live chat support within the app.

Responses that commented on the layout of a developed app were coded under this theme. Participants provided practical suggestions (e.g. large print, white space) for the layout of a prospective app. Other participants commented on including videos, graphics, and images from caregivers when presenting information to increase appeal and engagement.

If costs need to be associated with using an app, participants expressed that an app needed to be cost-effective and affordable. In particular, participants expressed that developers should consider that cost may be a barrier for caregivers.

Discussion (Study 2)

We examined the utility of the Dementia Talk and CLEAR Dementia Care apps among ICPDs. Although our participants identified positive characteristics of the apps, this did not translate to improvements in outcome measures. Despite the absence of apparent benefits of apps on our outcome measures, we found a significant main effect for time. That is, participants in all conditions showed reductions in overall stress and improved knowledge about dementia over the course of the study. The learned information from the app and extraneous information learned by participants in all groups may have contributed to these results.

Regarding the lack of evidence for the efficacy of app use in our controlled comparison, existing apps are simple and do not seem capable of fully addressing the complex psychological concern of caregiver burden. Interviews with participants indicated that, while participants found the apps to be informative, they often noted negative aspects of the user experience. As such, difficulties using the apps may have attenuated their potential benefits.

Caregivers commented on two major areas to consider when developing apps for them: content and user-experience. Participants reported that the primary value they see in mobile apps is their potential to maintain a record of and collate information about the care recipient. This is not surprising as caregivers often juggle multiple responsibilities at once. Recordkeeping and monitoring are unique contributions that mobile apps and technologies can make in care management distinguished from strategies provided by other approaches (e.g. psychosocial interventions). The expressed need for support relating to caregivers’ mental health is not surprising as this is the most frequently cited need of caregivers (e.g. Queluz et al., Citation2020; McCabe et al., Citation2016; Black et al., Citation2013). This underscores the importance of digital technologies to incorporate components addressing the mental health needs of caregivers.

The importance of user experience is highlighted in the technical considerations outlined by participants in the development of future mobile health apps for ICPDs. A majority of participants reported ease of use as a critical component to consider in developing apps. Many participants raised the importance of being cognizant of user age and experience with technology in designing mobile apps. These sentiments suggest that the development and evaluation of technologies for ICPDs can be facilitated and informed by ICPD input (Harrington et al., Citation2018).

Limitations

We acknowledge the possibility that our outcome measures may not have adequate sensitivity to detect change over our relatively short intervention period. Although this time frame was chosen because the apps lacked complexity and variety of features, it remains possible that a lengthier intervention period or different outcome measures (e.g. daily hassles) may have rendered different results. We recognize that delivering instruments in alternative formats could impact the validity of the tools. The measures used in the study have been found to be valid when administered online (e.g. Greeson et al., Citation2020; Klug, Citation2017; Lynch et al., Citation2018; Pieh et al., Citation2020). Internal consistency values for the measures that were included in the main statistical analysis (i.e., DKAT2, PSS-10, ZBI) also supported retention of their psychometric properties. Unfortunately the internal consistency of the SUS scale was low limiting conclusions that can be drawn from the group comparison of the subjective app ratings (secondary analysis). Although prior research has demonstrated that economic incentives increase participation rates in research, they may introduce a bias as individuals with financial needs may be more likely to participate. As such, our offering monetary incentives to our participants could have limited the generalizability of the findings.

General discussion

With the advent of technology, apps for ICPDs provide various opportunities to improve the delivery of and access to interventions. We contributed an updated review and evaluation of apps available for caregivers, tested the efficacy of selected apps, and assessed the needs of ICPDs in relation to the development of future apps.

Our two studies taken together demonstrate an urgent need to develop and evaluate better apps for caregivers that are capable of addressing caregiver stress. Empirical evidence in support of the use of such apps would be necessary prior to their widespread distribution. Existing apps for ICPDs are very limited in their features and unlikely to adequately address psychological distress and caregiver burden. Moreover, apps for ICPDs have significant limitations in their content and design, as well as an insufficient evidence base. The lack of significant differences between the app and control groups also supports the need for improved apps for caregivers. The development of better and more comprehensive apps, in collaboration with ICPDs, has the potential to contribute to reductions in the burden associated with caregiving. The outlined needs of caregivers (e.g. monitoring, connections to support, psychological resources, ease of use) identified in this study can help guide future mHealth developments to adequately address the needs of ICPDs.

Our innovative assessment of apps based on theoretical frameworks of stress, is unique in this area, and can inform the development and evaluation of future apps. This assessment identified significant gaps. For instance, none of the apps available for ICPDs included any features that considered the background and context of stress (e.g. age, ethnicity, gender, relationship with care recipient) which are deemed important in Pearlin et al. (Citation1990) Stress Process Framework. In a mobile app, adding context might involve optimizing app customization and providing resources tailored to the unique needs of different subgroups of caregivers (e.g. issues specific to female caregivers or spouses). More than simply assisting future development, the frameworks of stress can also be used in future evaluations on the effectiveness of apps. For example, the number of theoretical framework components incorporated within an app would be expected to be predictive of its success in ameliorating caregiver stress and burden. We are optimistic that our investigation will help propel both app development and evaluation in this area.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Regina Research Ethics Board (#2021-177).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (41.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Portions of this paper were previously presented at the AGE-WELL 2022 Annual Scientific Conference.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data will be made available upon reasonable request from [email protected].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bangor, A., Kortum, P. T., & Miller, J. T. (2008). An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(6), 574–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447310802205776

- Baranzini, D. (2018). SPSS single dataframe aggregating SPSS multiply imputed split files. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.33750.70722

- Black, B. S., Johnston, D., Rabins, P. V., Morrison, A., Lyketsos, C., & Samus, Q. M. (2013). Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: Findings from the maximizing independence at home study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(12), 2087–2095. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12549

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Brooke, J. (1996). Usability evaluation in industry, chap. SUS: A “quick and dirty” usability scale.

- Brown, E. L., Ruggiano, N., Li, J., Clarke, P. J., Kay, E. S., & Hristidis, V. (2019). Smartphone-based health technologies for dementia care: Opportunities, challenges, and current practices. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 38(1), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464817723088

- Brown, J., & Kim, H. N. (2019). Lessons learned from conducting Alzheimer’s disease caregiver mHealth app training and focus group sessions [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Conference, Los Angeles, CA. November.

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Greeson, J. K., Treglia, D., Morones, S., Hopkins, M., & Mikell, D. (2020). Youth Matters: Philly (YMP): Development, usability, usefulness, & accessibility of a mobile web-based app for homeless and unstably housed youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 104586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104586

- Harrington, C. N., Wilcox, L., Connelly, K., Rogers, W., & Sanford, J. (2018). Designing health and fitness apps with older adults: Examining the value of experience-based co-design [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 12th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, New York, NY. May.

- Jakobsen, J. C., Gluud, C., Wetterslev, J., & Winkel, P. (2017). When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials–A practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1

- Kleinke, K. (2017). Multiple imputation under violated distributional assumptions: A systematic evaluation of the assumed robustness of predictive mean matching. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 42(4), 371–404. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998616687084

- Klug, B. (2017). An overview of the system usability scale in library website and system usability testing. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 1(6). https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.602

- Krauskopf, P., & Golden, A. (2016). AIDSInfo HIV/AIDS Guidelines App and DementiAssist App. Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 12(8), E373–E375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2016.06.001

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lynch, S. H., Shuster, G., & Lobo, M. L. (2018). The family caregiver experience–examining the positive and negative aspects of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue as caregiving outcomes. Aging & Mental Health, 22(11), 1424–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1364344

- McCabe, M., You, E., & Tatangelo, G. (2016). Hearing their voice: A systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. The Gerontologist, 56(5), e70–e88. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw078

- McCoy, C. E. (2017). Understanding the intention-to-treat principle in randomized controlled trials. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(6), 1075–1078. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2017.8.35985

- MindSea. (2021). 28 mobile app statistics to know in 2021. https://mindsea.com. https://mindsea.com/app-stats/

- Montazeri, A., Vahdaninia, M., Mousavi, S. J., & Omidvari, S. (2009). The Iranian version of 12-item short form health survey (SF-12): Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 341–310. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-341

- Nielsen, M. G., Ørnbøl, E., Vestergaard, M., Bech, P., Larsen, F. B., Lasgaard, M., & Christensen, K. S. (2016). The construct validity of the perceived stress scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 84, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.03.009

- Núñez-Naveira, L., Alonso-Búa, B., de Labra, C., Gregersen, R., Maibom, K., Mojs, E., Krawczyk-Wasielewska, A., & Millán-Calenti, J. C. (2016). UnderstAID, an ICT platform to help informal caregivers of people with dementia: A pilot randomized controlled study. BioMed Research International, 2016, 5726465. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5726465

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583

- Pieh, C., Budimir, S., & Probst, T. (2020). The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 136, 110186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110186

- Prince, M., Bryce, R., Albanese, E., Wimo, A., Ribeiro, W., & Ferri, C. P. (2013). The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9(1), 63–75.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007

- Queluz, F. N., Kervin, E., Wozney, L., Fancey, P., McGrath, P. J., & Keefe, J. (2020). Understanding the needs of caregivers of persons with dementia: A scoping review. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.2196/12274

- Riffin, C., Van Ness, P. H., Wolff, J. L., & Fried, T. (2017). Family and other unpaid caregivers and older adults with and without dementia and disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(8), 1821–1828. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14910

- Rosa, E., Lussignoli, G., Sabbatini, F., Chiappa, A., Di Cesare, S., Lamanna, L., & Zanetti, O. (2010). Needs of caregivers of the patients with dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 51(1), 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2009.07.008

- Sheehan, O. C., Haley, W. E., Howard, V. J., Huang, J., Rhodes, J. D., & Roth, D. L. (2020). Stress, burden, and well-being in dementia and nondementia caregivers: Insights from the Caregiving Transitions Study. The Gerontologist, 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa108

- Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L., Kavanagh, D. J., Zelenko, O., Tjondronegoro, D., & Mani, M. (2015). Mobile app rating scale: A new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(1), e27. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3422

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.), Pearson, London, England.

- Terhorst, Y., Philippi, P., Sander, L. B., Schultchen, D., Paganini, S., Bardus, M., Santo, K., Knitza, J., Machado, G. C., Schoeppe, S., Bauereiß, N., Portenhauser, A., Domhardt, M., Walter, B., Krusche, M., Baumeister, H., & Messner, E.-M. (2020). Validation of the mobile application rating scale (MARS). PloS One, 15(11), e0241480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241480

- Thorpe, J., Forchhammer, B. H., & Maier, A. M. (2019). Adapting mobile and wearable technology to provide support and monitoring in rehabilitation for dementia: Feasibility case series. JMIR Formative Research, 3(4), e12346. https://doi.org/10.2196/12346

- Toye, C., Lester, L., Popescu, A., McInerney, F., Andrews, S., & Robinson, A. L. (2014). Dementia knowledge assessment tool version two: Development of a tool to inform preparation for care planning and delivery in families and care staff. Dementia (London, England), 13(2), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301212471960

- Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, H., & Snelgrove, S. (2016). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 6(5), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100

- Ware, J. E., Jr, Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003

- Wozney, L., de Souza, L. M., Freitas, Kervin, E., Queluz, F., McGrath, P. J., & Keefe, J. (2018). Commercially available mobile apps for caregivers of people with Alzheimer disease or other related dementias: Systematic search. JMIR Aging, 1(2), e12274. https://doi.org/10.2196/12274

- Yap, P. (2010). Validity and reliability of the Zarit Burden Interview in assessing caregiving burden. Annals of the Academy Medicine of Singapore, 39, 758–763.

- Zarit, S., Orr, N. K., & Zarit, J. M. (1985). The hidden victims of Alzheimer’s disease: Families under stress. New York, NY: NYU press.