ABSTRACT

Do populist parties refer to class identities in their discourses or do they, as most populism literature assumes, mainly highlight a moral distinction between ‘people’ and the ‘elite’? To explore these questions, this research uses dictionary-based methods and discourse analysis to identify the various ways to reconstruct such identities in Spanish populist left (Podemos) and right (Vox) political parties between 2014 and 2023. Our findings reveal that both the populist left and populist right politicise class divisions as much as moral divides, even more so in the case of the left. Moreover, we observe significant differences in the class identities mobilised by Podemos and Vox and their evolution over time.

Introduction

Social class and populism are closely related phenomena that are, however, understudied in their interrelations. Conventional wisdom assumes that populism is a political discourse or ideology that offers a response to a perceived or real representative deficit in liberal democracies. In line with a minimalist definition, populism is conceived as an ideational or discursive phenomenon characterised by an opposition between the people and the elites and by the claim to represent popular sovereignty (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2018; Stavrakakis & Katsambekis Citation2019). Populist discourse is presupposed to appeal to the ‘people’ as a whole and not to a restricted or identified class. The dominant perspective in the field of populism studies, known as the ideational approach, contends that the definition of the ‘people’ by populists is primarily based on a moral distinction between the people and elites, e.g. by defining the former as virtuous or pure against corrupt and evil elites (see Mudde Citation2004, p. 543, Citation2021, p. 579; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012, p. 8; Urbinati Citation2019, pp. 116–7; Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020, p. 3). Simultaneously, those socioeconomically marginalised or deprived are expected to be more prone than the general population to embrace populism, since a lack of representation and societal exclusion tend to go hand to hand. In this vein, most research focuses on populism’s demand side to analyse the individual level socioeconomic conditions that increase the likelihood of voting for a populist party. What this research commonly finds is that it is the least privileged who are most likely to support populist actors (Kriesi et al. Citation2006; Spruyt, Keppens & Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016). In a more recent turn in the literature, scholars have combined the cultural and economic theses and argued that socioeconomic status and social identity are inseparable phenomena (Gidron & Hall Citation2020). Others, in contrast, question the accuracy of broad cross-national causal claims relating low socioeconomic status to the populist vote (Rooduijn Citation2018; Berman Citation2021).

Although research on the demand side and its relationship with socioeconomic class is developing fast, the supply side of populism regarding this topic has been relatively unexplored. This paper argues that this is highly problematic since the perception of citizens about their class identity is also related to the political discourse and group appeals by key political actors, for example, populist parties. Political actors may influence citizens’ self-perception about their class and how this intervenes in their political preferences via their public discourse (Thau Citation2021, Citation2023; Stuckelberger & Tresch Citation2022; Häusermann, Kurer & Zollinger Citation2023; Roch Citation2024a). In fact, recent cross-national research on the topic of socioeconomic class shows that the mutual relation between class and parties is mediated by the position and discourse of parties on this question (see Evans, Stubager & Egge Langsæther Citation2022; Steiner et al. Citation2023; Thau Citation2023). Therefore, it is critical to explore if populist parties on both sides of the ideological spectrum articulate socioeconomic categories in their political discourse about the ‘people’ or if they conceive them as a homogeneous group, simply defined as virtuous in contrast to the ‘elite’.

This article aims to fill this research gap by investigating the ability of populist actors to rearticulate class identities. To do so, we develop a comprehensive supply-side study to evaluate the relevance of class-related identities in comparison to moral identities in the construction of the populist subject. We analyse both the main Spanish populist radical right party (PRRP, Vox) and the populist radical left party (PRLP, Podemos – ‘We Can’) to capture their supply side discursive dimension.Footnote1 Spain represents an excellent case study, as it is home to populist parties that emerged simultaneously but on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum. This allows us to analyse how, within the same social, economic, and political context, two distant populist parties construct their images of the ‘people’. Since their inception, both political parties have evolved electorally, transitioning from challenger to governing parties. This evolution has also impacted their political strategies: over the years, the presence of populist discourses in Vox and Podemos have varied (Mazzolini & Borrielo Citation2022; Roch Citation2024a; Rico Motos & Del Palacio Martín Citation2023), although their speeches are still commonly defined as populist or as having a variable degree of populism (Olivas-Osuna & Rama Citation2022; Rico Motos & Del Palacio Martín Citation2023; Zanotti & Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2022).

The article uses a dictionary-based method to measure the relevance of socioeconomic categories related to class over time for the two parties in comparison to the moral definition of the ‘people’. The results indicate that socioeconomic class identities are as relevant as moral identities (and even more so in most of the periods analysed) to construct the ‘people’ of Podemos and Vox. This finding invites us to revise the central assumption of the ideational approach that contends that populism is defined primarily by a moral and homogeneous construction of the ‘people’ (Mudde Citation2021, p. 579; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012, p. 8; Urbinati Citation2019, pp. 116–7). Moreover, this study unpacks two complementary ways to construct the ‘people’ through socioeconomic class identities (the integrated-stable workers versus the precariat – those poor, unstable, or unemployed), showing significant differences in the use of these categories by Podemos and Vox. As the findings suggest, variation in the emphasis that the parties place on integrated workers or precariat identities can be related to broader political strategies, as will be discussed in the following sections.

The study of the interlinkages between socioeconomic class and populism

The relationship between populism and socioeconomic class has been extensively explored in the literature. However, this research has primarily focused on the demand side of populism, that is, the specific socioeconomic profile of those supporting or voting for populist parties. The literature on this topic seeks to identify a citizen profile, in socioeconomic terms, that is inclined to support populism or have populist attitudes: famously known as ‘those left behind’ or the ‘losers of globalisation’ (Kriesi et al. Citation2006; Kriesi & Schulte-Closs Citation2020; Rodrik Citation2018, Citation2021; Steiner, Schimpf & Wuttke Citation2023). The evidence is contradictory in this respect with recent studies rejecting the idea of a ‘populist citizen’ or a single citizen profile supporting populism (Rooduijn Citation2018; Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020). Moreover, there is evidence questioning that those with low socioeconomic status are more likely to support populist parties (Berman Citation2021, p. 75).

Recent advances in the ‘losers of globalisation literature’ argue that the very category of ‘losers’ is highly context dependent. While in some countries, the ‘losers’ more prone to support populist parties are the less educated and skilled workers (Häusermann & Kriesi Citation2015; Rooduijn Citation2018; Goodwin Citation2014; Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020), in other countries the ‘losers’ are highly skilled and educated individuals (Teperoglou, Tsatsanis & Nicolacopoulos Citation2015; Stockemer Citation2017). A further complication with generalising a single profile of a ‘populist citizen’ across national contexts relates to the wide diversity of populist actors with different ideologies, discourses, and political strategies (Rooduijn Citation2018; Roch Citation2024a; Kriesi & Schulte-Closs Citation2020). According to this view, the socioeconomic conditions of individuals can be decisive in a specific context and time, and irrelevant in determining the ‘populist vote’ in other scenarios. This may be because populist actors on the right and left may make divergent appeals to socioeconomic circumstances, thus offering different strategies to activate this cleavage to attract electoral support. In fact, there is ample literature on how parties´ appeals to specific group identities serve to crystallise, amplify, or downplay group identities and the specific identification of voters with a particular class (Thau Citation2023; Angelucci & Vittori Citation2023; Häusermann, Kurer & Zollinger Citation2023). It is also empirically substantiated that this is a two-way relationship, in which parties’ appeals influence voter identification, and voter identification has, in turn, an effect on parties’ appeal to specific social groups (Stuckelberger & Tresch Citation2022).

However, although the heterogeneity of the people has been empirically explored on the demand side (Rooduijn Citation2018; Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020), there has been no systematic analysis on the role of socioeconomic and moral identities on the supply side of populism. Research on the supply side by ideational scholars has explored, in contrast, the populist nature or degree of populism of political parties (Aslanidis Citation2017; Rooduijn et al. Citation2019; Meijers & Zaslove Citation2021, Gründl Citation2020). There is also research on the interlinkages between the ‘thin’ ideology of populism (people centrism, anti-elitism) and party positions based on broader ‘thick’ ideologies (anti-immigration, economic policies, Euroscepticism, and anti-globalism; see Taggart & Szczerbiak Citation2002; Pirro, Taggart & van Kessel Citation2018; Taggart & Pirro Citation2021). Close to this paper´s approach, Heinisch and Werner (Citation2019) examine descriptive representation by populist radical right parties, finding broad diversity in the appeals to different socioeconomic groups. Notwithstanding the diversity found in ideational studies on populist actors’ appeals, there is no specific research on the relative importance of socioeconomic class versus moral identities on the supply side of populism. This question is theoretically relevant since there is an ongoing debate on the centrality of the moral construction of the people by populist actors (see Mudde Citation2021, p. 579; De Cleen & Glynos Citation2021; Katsambekis Citation2020; Roch Citation2024a, Citation2024b).

Academics supporting the discursive approach to populism have devoted considerable time to exploring the way in which populist discourse may articulate heterogeneous demands and potentially disparate identities (Laclau Citation2005; Katsambekis Citation2020). Following this approach, ‘the people’ of populist discourse are not homogeneous but composed of various and mixed demands. These scholars also reject the argument, contending that the central trait to distinguish the people defined by populist actors is virtuous morality, as the ideational approach suggest (Katsambekis Citation2020; De Cleen & Glynos Citation2021). Furthermore, the discursive approach shows particular interest in divergences between right and left populist actors; the latter being more inclined towards discourses that include diverse population groups (Katsambekis Citation2020, p. 14). Notwithstanding this interest in the differentiated appeal to the people on the supply side of populism, there is no empirical evidence on the degree of relevance of ‘class-related identities’ compared with ‘the people’ defined in ‘moral terms’ and no exploration of how this varies for right and left populist parties. This lack of empirical evidence on class-related identities can be related to the Laclaudian idea that identities do not pre-exist the articulatory discursive logic of populism but are rather constructed via the identification of an empty signifier of populism and a chain of equivalence of demands antagonising the elites (Laclau Citation2005, pp. 158–61).

This paper contends that there are pre-existing socioeconomic and moral identities that can be identified, and at the same time populist discourse serves to articulate and unify them. Although based on different strategies, PRRP and PRLP might use social class divisions as well as moral markers to structure, define, and mobilise distinct electorates, and these electorates might act in response (Akkerman, Zaslove & Spruyt Citation2017; Stuckelberger & Tresch Citation2022). Therefore, it is critical for the analysis of populism to elucidate how populist parties on the right and left reconfigure class identities. It is also pressing to collect systematic evidence that serves to arbitrate the long-term academic dispute between those arguing that the populist subject is defined in moral terms and those defending a more plural and heterogeneous people also on the supply side of populism.

Towards an analytical framework to study populism and class

Populist discourse seeks to build a legitimate popular subject that is opposed to elites, with both the people and elites being defined in various ways depending on the political actor’s ideology and strategy (Laclau Citation2005; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2013; Urbinati Citation2019; Katsambekis Citation2020). Assuming the premise of heterogeneity within this popular subject, we expect that populist discourse articulates disparate identities to construct the people. As noted, the people are in part constructed in opposition to the elites, but also by referring to their own characteristics, delimiting and distinguishing the people from other social groups. Based on the populism literature, there are two central ways to identify and delimit the characteristics of the people. One, which is extensively studied, is the moral construction, whereby ‘the legitimate people’ are described as virtuous (good, honest, loyal, or brave) in contrast with the corrupt and evil elites (Mudde Citation2004, Citation2021; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012; Müller Citation2016; Urbinati Citation2019). In the words of Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘populism is in essence a form of moral politics, as the distinction between “the elite” and “the people” is first and foremost moral (i.e. pure vs. corrupt), not situational’ (Citation2012, p. 8). This does not imply that the moral construction of the people excludes socioeconomic class, ethnicity, race, or other markers, but that they are secondary in the overall structuration of the populist discourse (Mudde Citation2021, p. 579).

There is another key way to construct the people by referring to their socioeconomic conditions, or what might be called socioeconomic class identities. Socioeconomic class as an identity marker can appear articulated with or complemented by the moral construction as well as other secondary identity markers (such as gender or ethnicity). According to demand side studies, it would be reasonable to expect that parties with populist discourses appeal to specific subgroups among the people, that is, the lower or excluded socioeconomic classes, since these strata seem to be attracted by populist ideas (Steiner, Schimpf & Wuttke Citation2023; Heinisch & Jansesberger Citation2022; Stuckelberger & Tresch Citation2022; Thau Citation2023). However, it is unknown the extent to which this is an important way to construct the people and which discursive strategies are mobilised by populist parties in this direction.

In the view of Gidron and Hall (Citation2020), social disintegration and fragmentation are the breeding ground for populism as a political discourse that seeks to articulate and unify disperse demands and identities (see also Laclau Citation2005). Those left behind or lacking recognition, in the words of Steiner, Schimpf and Wuttke (Citation2023), are united by a populist discourse that empowers and legitimises them (p. 4). As mentioned, these feelings of marginalisation can be explained in various ways and are employed differently by populist parties to articulate these groups and identities. First, the degree and type of appeal to those left behind depend on the ideological orientation of the political party. Whereas PRLP focus more on the socioeconomic cleavage, PRRP more markedly exploit the cultural cleavage or fears about immigration (Rodrik Citation2018; Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020, p. 6). Right-wing populist parties tend to employ moralistic discourses to a greater extent, emphasising traditional values, national identity, and cultural homogeneity, appealing to a more abstract audience against perceived threats to their way of life, such as immigration, globalisation, or liberal elites (Roberts Citation2017, Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2014, p. 480;, p. 14; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2013, pp. 159–61). By contrast, left-wing populist parties tend to employ a political discourse with a clear focus on economic inequality and social justice (Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020, p. 5; Hutter, Kriesi & Vidal Citation2018; Vachudova Citation2021, pp. 477–8; Venizelos & Stavrakakis Citation2022, pp. 4–5) and seek to mobilise support among the working classes by highlighting the divide between the elite and the masses. Therefore, we expect that

H1:

Socioeconomic class identities have greater salience in constructing ‘the people’ in PRLP than in PRRP.

Second, the relevance of class-related identities on populism’s supply side is conditioned by the party’s strategic orientation, which may focus on specific class fractions and ignore others. It is well established in the literature how parties’ appeals to certain socioeconomic strata of the population may increase the likelihood of being supported by them. For instance, Steiner et al. (Citation2023) argues that ‘the less libertarian PRLPs [radical left parties] are, the higher their support among production workers relative to their support among socio-cultural professionals’ (p. 2). In the same vein, other authors show how the class-based discourse of political parties reinforces the identities of those voting based on class-related issues (Thau Citation2021; Angelucci & Vittori Citation2023; Häusermann, Kurer & Zollinger Citation2023; Langsæther, Evans & O’Grady Citation2022; Evans, Stubager & Egge Langsæther Citation2022).

Assuming heterogeneity within the working population, there is a crucial divide for political preferences based on the distinction between those poor, unstable, or unemployed (precariat) and those integrated and stable workers. These two subgroups within the working population are expected to have divergent world views and political preferences (Oesch & Rennwald Citation2018). We know that both precariousness and working conditions can increase affinity with populist parties (Zagórski, Rama & Cordero Citation2021; Ramaekers et al. Citation2023), but it is unknown to what extent there is an emphasis on the most precarious or on the contrary on those integrated and stable sectors of the working population in populist parties’ discourses. While the former would need access conditions to the labour market, for instance benefits and stabilisation measures, the latter would be more interested in protection and improvement of their current conditions (related to salary, workplace, etc.). On the one hand, there is evidence (although no definitive consensus) on how workers in precarious conditions are one of the most well-established bases for the political left (Oesch & Rennwald Citation2018; Angelucci & Vittori Citation2023, Gómez & Ramiro Citation2022; Steiner et al. Citation2023; Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020, p. 4). On the other hand, PRRPs have, over the last two decades, made inroads among working-class electoral voters, especially those resentful of migration or ‘globalisation threats’ reducing their salaries (Oesch & Rennwald Citation2018; Kriesi & Schulte-Closs Citation2020, p. 2; Heinisch & Werner Citation2019; Häusermann, Kurer & Zollinger Citation2023). Therefore, we expect that PRLP and PRRP articulate their populist discourse with a strategic appeal to class-related identities pertaining to the specific sectors that are most inclined to becoming potential voters.

H2:

PRLP are more inclined to politicise class-identities related to precarious, poor, and unstable sectors.

H3:

PRRP are more inclined to politicise class identities related to the integrated and stable working population.

These party appeals would vary over time according to the degree of populism expressed by the political actor and in relation to more general conditions shaping the political context and the overall strategy of the parties. Recent literature has shown that political actors can vary their degree of populism based on strategic adaptation to the political context (see Mazzolini & Borriello Citation2022; Roch Citation2021, Citation2024a; Hunger & Paxton Citation2022; Bonikowski & Gidron Citation2016). In this sense, the degree of populism may impact, in turn, the relative appeal to socioeconomic or moral identities or, within the working population, the precarious or integrated and stable workers. Primarily, we expect variation depending on the degree of electoral success and the level of institutionalisation of the parties.Footnote2 Research has shown that those outsiders with little chance of directly influencing public policy tend to both employ stronger anti-elite discourse and be more innovative in introducing new issues into public debate that are commonly ignored by mainstream parties (De Vries & Hobolt Citation2020, p. 4; Vachudova Citation2021, pp. 476–477). The role of parties as serious contenders with high electoral expectations may affect their attempt to moderate the message and downplay some problematic issues in seeking to broaden their electoral base (Schmidt Citation2023, pp. 15–17). Finally, entrance into parliamentary institutions and active involvement in parliamentary activities and coalition-seeking attempts may also force populist actors to adapt and assume some normative constraints in their political discourse (Roch Citation2024a, pp. 56–7; Askim, Karlsen & Kolltveit Citation2022, pp. 730–731). Therefore, we expect a decline in populist discourse over time parallel to national election competition and institutionalisation of parties. This expected variability in populist actors’ political discourse invites exploration of populism’s supply side over time and across different periods.

Spain as a case study

The Spanish party system has traditionally been characterised as ‘imperfect bipartisan’, in which two mainstream parties competed in the national arena to form a government either through an absolute or simple majority (Linz & Montero Citation1999). However, as in other European countries, the Great Recession led to a profound change in party competition and opened the door to the entrance of new parties (Orriols & Cordero Citation2016; Rodríguez-Teruel, Barrio & Barberà Citation2016). The starting point was the 15-M (15 May 2011) movement, which involved millions of people demonstrating in major cities against the PSOE’s (Spanish Socialist Party) social welfare cuts. Despite the significant impact of these street protests, the Spanish party system did not experience an immediate shock. During that same year, the PP (Popular Party, conservative party) emerged victorious with the promise of reverting the PSOE’s economic measures (Orriols & Cordero Citation2016). However, just a few months later, the bail out negotiated between the PP government and the Troika (comprising the European Commission, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund) eroded the trust of Spanish citizens on both sides of the ideological spectrum, resulting in the dismantling of the Spanish bipartisan structure (Cordero & Simón Citation2016).

Thus, during the European elections in the spring of 2014, Podemos emerged embodying a populist discourse and crystalising the 15-M social movements. The low popularity of the two mainstream parties was the perfect breeding ground for anti-elite ideas and the characteristics of a second-order election were the perfect framework for a recently created party to gain electoral support. In the Spanish context, Podemos represented a leftist populist party with the strong leadership of Pablo Iglesias, who had gained popularity in media appearances. Though Podemos only secured five out of the 54 seats for Spain in the European elections, this unexpected result clearly disrupted, for the first time, the traditional bipartisan Spanish party system.

At the national level, two general elections were held in Spain in six months, in December 2015 and June 2016 (Rodríguez-Teruel, Barrio & Barberà Citation2016). The difficult negotiations to select a prime minister following these elections brought to light the so far unknown pivotal role of the emerging parties to form a government. Podemos and Ciudadanos (Citizens, a newly formed centre-liberal party) were now essential in negotiations as the third and fourth political forces in the national arena. During these elections, Vox also began its transformation into its present form. If Podemos primarily grew on the left as a populist response to the Great Recession, Vox predominantly expanded within the right as a populist and nationalist response to the secessionist movements in Catalonia. Throughout these events, Vox positioned itself as a plaintiff in the case against the promoters of Catalonia’s secession and garnered attention for its opposition to the conservative government’s failure to prevent the referendum.

Although Vox was founded in December 2013, it gained its first parliamentary seats in December 2018, in the regional Andalusian election (Rama, Cordero & Zagórski Citation2021). In this context, the party entered a new period of development and popularity, positioning itself as the representative of the ‘revolution of the balconies’ (‘revolución de los balcones’; referring to the multitude of secessionist flags on the balconies of Catalonia and Spanish flags in other areas of Spain), criticising the position of the Spanish government in the Catalan secessionist conflict. The numerous cases of corruption affecting the PP led to the PSOE tabling a successful no-confidence motion and the subsequent call for elections in April 2019. However, parliament’s growing fragmentation resulted in the PSOE again calling for elections in November after not being able to approve budgets. The role of the recently created parties was again made evident. In this new call, Vox had outstanding electoral success with 52 seats, and became the third party in parliament. Despite the poor results of Unidas Podemos (United We Can, with 35 seats) and PSOE (120 seats), both formed the first coalition government in Spain’s recent history.

Podemos’ and Vox’s electoral developments, following their first emergence at the national level in 2015 and 2019, respectively, were variable. In July 2023, Vox re-ran as a populist alternative to the PP, obtaining 33 seats, while Podemos only reached 31, this time in the form of Sumar (Add Up).Footnote3 Although these results were not as good as those obtained in previous elections, they seem to be pointing towards the consolidation of a multi-party system, in which populist parties, both on the left and the right, play a fundamental role in facilitating the formation of governments.

In relation to the GAL-TAN axis, Vox is positioned towards the Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist end of the axis, emphasising traditional values, law and order, and Spanish nationalism. In contrast, Podemos aligns more with the Green-Alternative-Libertarian side, supporting progressive policies, civil liberties, and environmental sustainability (Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama & Santana Citation2020). Throughout various elections, both parties have used populist discourse less, although they have never entirely abandoned these arguments (Zanotti & Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2022).

Since its birth, Podemos has evolved, and its complex internal dynamics have become apparent, resulting in the emergence of divergent strategies within the party (Mazzolini & Borriello Citation2022). While its leader Pablo Iglesias advocated for a strategic partnership with Izquierda Unida (the United Left; of which the Communist Party is an important part), reflecting a more traditional leftist approach, Íñigo Errejón emphasised a clearer populist strategy, prioritising broad appeal and outreach to a wider segment of the electorate (Rico Motos & Del Palacio Martín Citation2023). Although this ideological rift eventually culminated in Errejón establishing his own political party and Podemos prioritising the more traditional divide between left and right instead of the divide between ‘the caste’ (elite) and the people (Rico Motos & Del Palacio Martín Citation2023), Podemos never abandoned a populist rhetoric and is still considered a populist party in most of the literature (Mazzolini & Borriello Citation2022; Roch Citation2024a). In the case of Vox, there is a lack of consensus regarding its classification as a populist party. While much of the literature identifies it as right-wing populist (Rama, Cordero & Zagórski Citation2021; Zanotti & Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2022), the nationalist and conservative elements often take precedence over its populist characteristics (Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro & O’Flynn Citation2021). However, the primary focus of this article is not to quantify the degree of populism within Podemos and Vox, but rather to examine how they exploit class differences in their depiction of the people. In the following section, we elaborate on our analytical strategy to study the extent to which and in what form these parties, from different ideological perspectives, have used class identities and moral identities to construct the people.

Data and methods

This study relies on a dictionary-based method of quantitative text analysis. Textual data (campaign speeches and manifestos) from Podemos and Vox were compiled between January 2014 and May 2023. As shows, the time-span analysed in this study covers four comparable stages in the parties’ development, since they entered the institutional landscape. These time periods are coherent with the expected changes described above about the overall strategy of the parties and their populist discourses. First, there was an initial election campaign in which they emerged and entered parliament for the first time (party in the making). In the case of Vox, this was in the Andalusian regional elections in December 2018 and in the case of Podemos, the May 2014 European parliamentary elections. The second period covers their first election campaign as ‘serious competitors’ in the national election (running for elections): in the case of Podemos for the general elections of December 2015 and June 2016, and for Vox in April and November 2019. The third stage refers to the period of institutionalisation (party in opposition/in office; 2017–22 in the case of Podemos and 2020–2022 in the case of Vox). Finally, we examine the speeches in the May 2023 regional election campaign (further institutionalisation); before the party Podemos was integrated into the Sumar coalition.

Table 1. Speeches, manifestos, and time periods of Podemos and Vox.

We explore a data set of 134 campaign speeches and 10 manifestos by using dictionary-based methods. Party speeches are especially relevant for exploring the construction and appeal to the people due to the direct communication of the representative with the represented (see Roch Citation2021; Laclau Citation2005). Manifestos are used to include a more formal genre in the analysis and because it is one of the most important documents defining the position of a party. All national and European manifestos are collected, and the selected speeches include every speech delivered and published on parties’ official accounts during the electoral campaigns by the party’s executive leaders and the main candidates in the elections (note that candidates and heads of party have been changing over time in the case of Podemos; see ).

In the tradition of text-as-data or quantitative text analysis, dictionary-methods are one of the tools that can be used to systematically measure analytical categories in text that are related to theoretical concepts, causal relationships, or external events. There are two main ways to use dictionary methods in social research. The most popular uses available dictionaries designed to capture sentiments (Proksch et al. Citation2019; Castanho Silva, Schürmann & Proksch Citation2023), or party positions (Laver, Benoit & Garry Citation2003). While this is a popular and relatively fruitful approach to dictionary methods, the clear limitation is its lack of precision for fine-grained or very specific research questions (see Gründl Citation2020; Wouter van Atteveldt Citation2021; Macanovic Citation2022; Muddiman, McGregor & Stroud Citation2019). The specific nuances of language and the variable impact of political phenomena such as migration or class politics in different countries shape the word constellations referring to these categories. However, it is possible to increase recallFootnote4 by reducing precision and developing a valid set of words or multiword expressions apt for general cross-country comparisons. This approach is especially advanced in the field of sentiment analysis (see, for instance, Proksch et al. Citation2019).

For this study, in accordance with the recommendations by experts on dictionary methods (Song et al. Citation2020; Wouter van Atteveldt Citation2021; Macanovic Citation2022; Muddiman, McGregor & Stroud Citation2019), the most cautious approach is to develop our own dictionary. The exploration of very specific research questions (such as the extent to which political parties construct ’the people’ as a moral or socioeconomic identity) demands very detailed and inductive explorations to ensure precision and exclude false positives. Self-created dictionaries have to be very well validated, since they have not been previously tested, but at the same time they have the potential to increase the a priori low validity of dictionary methods (see Grimmer & Stewart Citation2013, pp. 8–9; pp. 2–3; Young & Soroka Citation2012; or Solis & Sagarzazu Citation2020, p. 30).

The goal of our dictionaries is to ensure precision and validity without undermining recall (see Grimmer & Stewart Citation2013; Gründl Citation2020; Nelson Citation2018), which implies pre-measurement validation checks as suggested by various scholars (Muddiman, McGregor & Stroud Citation2019; Macanovic Citation2022). In doing so, we first focus on ensuring recall by including in our dictionaries all terms and multi-word expressions that (1) are related to socioeconomic class or moral identities and (2) serve to qualify ‘the people’, as the subject of populism. The first step is to identify all signifiers used by the parties, Vox and Podemos, to refer to ‘the people’ (citizens, persons, common people, etc; see Annex A). Secondly, we undertake a collocation and concordance analysis of these terms with the corpus linguistic software Wordsmith (Scott Citation2016). Collocation analysis is a technique of corpus linguistics which serves to identify all words co-occurring with the node word (e.g.: ‘the people’, ‘the citizens’). At this stage, we aim to maximise the number of collocates by providing socioeconomic or moral connotations for the people, for instance, ‘poor Spaniards’ or ‘honest people’.

In a third step, we manually revise the list of collocates of all node words for the parties and identify those related to our categories of interest (socioeconomic class and moral identity). At this point, there is a first pre-measurement validation check (following recommendations by Song et al. Citation2020, 552; Muddiman, McGregor & Stroud Citation2019) seeking a balance between high recall and high precision: the software Wordsmith allows us to access all the concordance lines (all sentences in which the collocates co-occur with the node words) and validate them manually. We validate a sample of these concordance lines to see if the collocate is attributing the expected meaning to the node word. For instance, if we identify ‘decent’ as a collocate of ‘the people’ (gente decente in Spanish, ‘decent people’) in the case of Podemos, we expect that this is a moral attribution to the people, but we cannot be totally sure until we check the specific sentences (concordance lines in linguistics) in which this attribution occurs.

Fourthly, after identifying all valid collocates and classifying them as indicators of socioeconomic class or moral identity, we search for frequent terms (in a frequency list) in the overall corpus of Podemos and Vox that can directly signify the people as socioeconomic class or moral identity, not as a collocate-adjective but as a noun. For instance, ‘poor’ (pobre) can operate as a collocate-adjective for the people indicating a socioeconomic identity (poor people). However, there are also compound nouns such as working class (clase obrera, clases populares in Spanish) signifying a class identity or moral identity. Finally, a second pre-measurement validation check is conducted at this stage to disambiguate single words that can take ambiguous or diverging meanings depending on the parties’ use. For instance, ‘work’ (trabajo) is a vague word that can refer to the class identity of the people or to more general work activities (e.g. parliamentary activities). We follow the suggestion by Young and Soroka (Citation2012, p. 212) to include these words in longer sentences that capture the particular use of a word. Hence, the detailed exploration of the concordance lines allowed us to identify those words that needed to be included in bigrams, 3-grams or 4-gramsFootnote5 to avoid false positives and ensure precision (see, for a similar approach, Gründl Citation2020, p. 9). All identified false positives and the process of disambiguation are reported in Annex A (see also Annex F and G).

This results in two main dictionaries formed by words and multiword expressions (bigrams, 3 and 4-grams) for the categories ‘socioeconomic class’ and ‘moral identities’ (see Annex B). Two additional dictionaries are created to measure the appeal to integrated workers or the precariat. Using the general dictionary about socioeconomic class identity, we extract those words corresponding to the precariat (poor, precarious, unemployed) and those related to stable and integrated workers. The selection criterion is based on the conditions of stability of the latter and the precarious and poor conditions of the precariat (see Annex B).

These four dictionaries are tested for validity in three post-measurement validation checks. First, there is a feature-based validation check, based on detailed exploration of the features (words and multiword expressions), which is highly recommended by leading scholars in the field (Muddiman, McGregor & Stroud Citation2019; Song et al. Citation2020; Macanovic Citation2022). We extract a sample of at least 70 per cent of all the occurrences of each feature included in the dictionary to be manually evaluated. After this validation check, those terms producing false positives have been deleted from the dictionary (Grimmer & Stewart Citation2013; Soroka Citation2015). Secondly, we evaluate, with the help of individual researchers, dictionary performance by manually hand-coding a sample of random text segments identified by our dictionaries. The text segments are evaluated to consider if they represent a socioeconomic class identification or a moral identification of ‘the people’. shows the reliability estimates comparing the hand-coder evaluation with the dictionary-based classification. Based on Cohen’s Kappa measures, the performance of the dictionaries is highly reliable, with rates between 87 and almost perfect agreement between hand-coding and dictionary-based calculations. Finally, our dictionaries’ performance is compared with that of already available dictionaries, in particular, the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) categories on work and moralisation.Footnote6 All figures, procedures, and false positives are reported in and in the Appendix. In sum, we conduct two pre- and three post-measurement validation checks, which guarantee the proper recall and precision required for our dictionaries’ good performance.

Table 2. Reliability estimates.

The occurrence of the categories socioeconomic class and moral identity are quantified measuring the relative salience of these dictionaries from 2014 to 2023. Salience is measured based on the number of occurrences of the word and multiword expressions in each text document (speech or manifesto) of Podemos and Vox. Salience is conceived as the frequency of words and multiword expressions and not based on the positionality of those words in the texts. This absolute occurrence is divided by the total number of words of each document, yielding a relative measure of the salience of socioeconomic and moral dictionaries per document and over time. All these pre-processing steps and the computation of the dictionaries are carried out with the R package tidytext (Silge & Robinson Citation2016) and other additional packages necessary for calculations in R.

In a second step, we compare the salience (understood as frequency) of the categories in quantitative terms (as shown in the graphs). Comparability is ensured based on objective and systematic procedures to extract the collocates and form lists of words and multiword expressions that guarantee the exhaustiveness and maximum recall of our dictionaries. The difference in the salience of socioeconomic and moral identities also serves to compare Vox and Podemos and to observe to what extent both parties’ salience is similar – or markedly different – for the two categories. Finally, the comparison shows how the relevance of these categories evolves. Therefore, these three levels of analysis offer comparative evidence on how the use of moral and socioeconomic categories differs in qualitative and quantitative terms between these two parties and over time.

Results

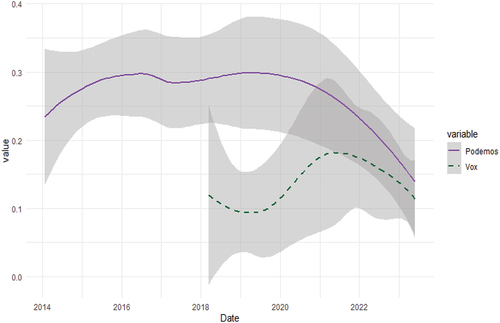

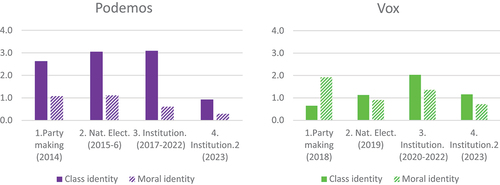

Confirming our first hypothesis, shows a significant disparity in the salience of class identities in constructing ‘the people’ within the speeches and manifestos of Podemos compared to Vox. The gap between these two parties was particularly wide between 2018 and 2020. During this period, while Vox placed little emphasis on class-based grievances, Podemos’ discourse highlighted the struggles of the working class. However, our analysis reveals that the difference in the salience of class identities between Podemos and Vox narrowed between 2020 and 2022.

As shows, during Vox’s early period (2018), ‘the people’ was primarily constructed in moral terms: Spaniards were defined as ‘brave’ and simple ‘people’, and Vox was ‘the party of the brave […] made up of brave Spaniards’ (Vox Citation2018a). The main threat during this period was represented by the Catalan secessionist conflict. Thus, the central divide invoked by the rightist party was a moral clash between the brave, honest, and normal Spaniards versus the ‘others’, as the following extract illustrates:

They are incapable of understanding that all of you here are normal people, people who have common sense, people who love their homeland and who want to live by the values that their parents have taught them and nothing else, in their lives going forward. As they do not understand what is happening and will continue to stigmatise usFootnote7 (Vox Citation2018d).

In contrast and questioning the broadly accepted assumptions in the literature on populism, socioeconomic class identities were more relevant than moral divides for Podemos, including in the first two periods of the party (2014–16) in which Podemos had a prominent populist discourse (see Franze Citation2017, Mazzolini & Borrielo Citation2022; Roch Citation2024a). In line with our first hypothesis, although ‘the people’ is also defined in moral terms as decent, ordinary, and honest, it was primarily linked to socioeconomic situations and social and economic rights.

Why do you think that in the end there is a health system that everyone can use, that even poor people can take their children to school? Because of rich people’s fear [of the poor] that has been a fundamental historical operator to spread democracy (Podemos Citation2014b).

The construction of the people as a socioeconomic class relies, as can be seen, on its antagonism with a specific segment of the elites – the rich people in Spain – with their interests clearly and explicitly confronted against the poor and working people and the expansion of democracy. When Vox refers to the elites, this party focuses rather on the political class instead of the economic elites or the rich and confronts these political elites to the ‘normal Spaniards’.

The difference between Podemos and Vox has narrowed since 2020, particularly since the two parties’ period of institutionalisation, underscoring the dynamic nature of political discourse and the strategic adaptation of parties to changing political landscapes. This was especially due to the prominence gained by socioeconomic class identities in the political discourse of Vox, their relevance becoming greater than moral divides since 2019, the first-time Vox competed in national elections. Vox increasingly turned its attention to the middle and lower classes, which are portrayed in opposition to political ‘globalist’ elites, as the following excerpt illustrates: ‘The so-called “green transitions” consist of transferring huge amounts of money from the middle and working classes to the elites driving the climate agenda’ (Vox Citation2021a). The rise of socioeconomic class identities in the case of Vox also relates to its attempt to replace traditional left-wing unions in Spain, creating its own union: Sindicato Solidaridad (Solidarity Union). The following excerpt shows how Vox attacks traditional unions:

The unions’ harmony with the unpatriotic oligarchies on the one hand, and with the separatist oligarchies on the other is absolute: they support open borders and illegal immigration that impoverish our workers (Vox Citation2022a).

Podemos remains more or less constant in the balance between moral and socioeconomic class elements in constructing ‘the people’. The moral dimension, although it is comparatively low in the first period, even decreases in salience over time, falling to the lowest in the 2023 election campaign when the party was already in the coalition government. This can be related to the decay of the populist discourse of Podemos as a response to institutionalisation processes and coalition-seeking constraints. There is a lower salience of the construction of the people, both moral and socioeconomic, in the last period analysed of the party Podemos in 2023. Although it is not as clear, Vox also decreased its populist discourse, referring less to the people, both in moral and socioeconomic terms, during the 2023 election campaign. However, there is a pattern that persists over the periods analysed: the higher salience of socioeconomic identities in the case of Podemos and the greater prominence of the moral construction of the people in the discourse of Vox, which confirms our first hypothesis. This is not to say that socioeconomic and moral aspects are mutually exclusive; on the contrary, they appear intertwined in discourses and frequently reinforce each other. For instance, in the following excerpt Podemos attacks the rich and the ruling class using moral and socioeconomic markers to construct the people and its opposition to the elites:

Most people want the rich to pay taxes sometime; most people love their country and love their people and want to keep their dignity; most people do not want to be a colony; most people are fed up with these crooks and scoundrels who are the ones who rule (Podemos Citation2014a).

Similarly, Vox combines the socioeconomic and moral identity to construct the people and criticise the political class, as in the following example: ‘The posh left (izquierda pija) does not pay attention to the needs of the workers and the simple people and only brings frivolity’ (Vox Citation2021b).

Integrated workers versus the precariat

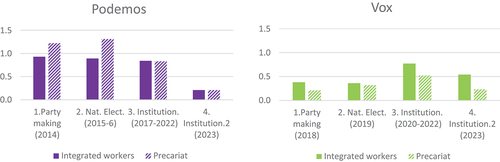

Our research findings partially support our second hypothesis, which posited that populist left parties are more inclined to politicise class identities related to precarious, unstable, and atypical workers (the precariat) rather than focusing on the stable and integrated working population. Our analysis of Podemos’ speeches and manifestos reveals a clear emphasis on addressing the concerns and grievances of these precarious workers, as shown in . Especially during the first two periods, Podemos refers to dependent people, in poverty, unemployed, and precarious workers, arguing for social and citizen rights to restore the dignity of these people. This focus on the specific struggles of these groups demonstrates a deliberate effort by Podemos to politicise their class identities and mobilise support from these sectors, as exemplified in the following excerpt: ‘People who work are in scandalously precarious situations. Intermón Oxfam and Caritas say that there are poor people who have a job’ (Podemos Citation2014c).

As expected in our third hypothesis, Vox focuses mainly on those integrated workers demanding good salaries and conditions and pays less attention to the precarious working population. The party linked the defence of the workers with a strong nation stating that ‘this is the party of the workers, the party of the self-employed, the party of housewives, the party of those who need a strong state because their economic weakness is reinforced and protected by a strong nation’ (Vox Citation2018c). Famously claimed by Vox, Spain is identified with ‘the Spain that gets up early, the Spain that gets up every day to raise its family’ (Vox Citation2018b).

There are also significant variations when analysing the salience of precarious versus integrated workers over time. The emphasis on class identities related to precarious workers by Podemos is confined to the early years of the party, especially the first two periods (2014–16). As Podemos underwent a process of institutionalisation and consolidation, their discourses gradually included more references to the integrated workers, reaching the same level of salience as the precariat during the last two analytical periods (2017–2023; see ). This evolution could be related to the institutionalisation process (normative constraints and coalition-seeking attempts with the centre left). This change might have been accelerated by the abandonment of the more clearly populist strategy advocated by Iñigo Errejón, and its replacement by a traditional strategy of defending workers, especially after the agreement with Izquierda Unida, with strong union ties and, therefore, an interest in defending stable and integrated workers.

Thus, in addition to appealing to the precarious, vulnerable, and poor strata of society, Podemos directed its attention to those consolidated working populations, who are probably more politicised and linked to trade unions, specifically Comisiones Obreras (Workers’ Commissions). Comisiones Obreras is the largest trade union in Spain, linked in its origins to the Communist Party, which is now part of Izquierda Unida. During the two last periods of institutionalisation since 2017 Podemos referred increasingly to those workers that struggle for a good salary and good conditions in their workplace and used terminology alluding to the traditional working class in Spain, as the following excerpt exemplifies: ‘there are many people, many working class people who are fed up and sometimes they may even consider it [vote for the right or the extreme right]. I ask them not to forget their class instinct’ (Podemos Citation2017). This evolution suggests that Podemos, on their way towards greater levels of institutionalisation, recognised the need to appeal to a more specific base of supporters, those from a low but more stable sector of society and adapted its discourse accordingly.

However, against our expectations (see hypothesis 3), shows that in the case of Vox the salience of the precariat increases during periods 2 and 3 but returns to the previous low levels in the last period of analysis (2023). Since the second period (2019 onwards), Vox refers to the ‘social emergency’ or ‘social protection’ needed by Spaniards and concentrates their specific appeal on people suffering from unemployment or poverty. Again, rejecting what they call ‘the climate consensus’, Vox considers that ‘ecological fanaticism […] makes people poorer because they were the poorest and the weakest and those who needed most support’ (Vox Citation2022b). This suggests that Vox recognised the importance of appealing to a broader range of voters and addressing the concerns of those outside their traditional support base. This evolution took place in parallel with the creation of the Solidarity union, linked to Vox, which was interested in attracting atypical and unstable workers, a less unionised sector of the working population. By incorporating references to the precariat, this party sought to expand their appeal to a wider working-class constituency and demonstrate their responsiveness to the economic hardships faced by precarious or non-stable working groups.

Discussion and conclusions

This article has addressed the question of how socioeconomic class identities are mobilised in populist discourse. Using data from Podemos and Vox between 2014 and 2023, we demonstrate that class identities are highly relevant when constructing the popular subject by populist actors, both on the right and on the left of the ideological spectrum. This pivotal finding contributes to the traditional academic debate on the homogeneity/heterogeneity of ‘the people’ in the populist discourse of political actors. This study has shown that the moral construction of the people as pure and virtuous on the supply side of populism is fruitfully articulated with specific socioeconomic identities. More importantly, socioeconomic class identities have not only been combined with moral definitions, but we have shown that the former is more relevant than moral identities to construct ‘the people’ of populist parties.

This is clearer in the case of the PRLP, such as Podemos, but also in the case of the PRRP Vox since the party first competed as a serious contender in national elections in 2019. Therefore, the relevance of socioeconomic class to construct the people of the populists seems to cross-cut political ideologies, especially during their processes of institutionalisation. This central finding invites us to reconsider or refine the homogeneity thesis (Mudde Citation2004, Citation2007, Citation2021). We have demonstrated that for the populist discourse, class-based identities are not ‘secondary criteria’ at all, as Mudde suggests (see Citation2021, p. 579; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012, p. 8; Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020, p. 3), but they are central and decisive features, both for the PRRP and the PRLP, to construct ‘the people’ on the supply side. Scholars working within the ideational approach have empirically demonstrated the heterogeneity of the people of populism on the demand side (Rovira Kaltwasser & Van Hauwaert Citation2020; Kriesi et al. Citation2006; Spruyt, Keppens & Van Droogenbroeck Citation2016; Rooduijn Citation2018), but we did not know much about how this heterogeneity was reflected on the supply side. The ‘monist’ and ‘moralist’ assumptions (Mudde Citation2021, p. 579; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012, p. 8) could have prevented the systematic exploration of heterogeneity on the supply side in previous analyses of populist discourses. Rather than a homogeneous, morally defined, and stable ‘people’, our study shows that the populist discourse portrays a people comprising several identities linked to both moral and economic grievances and varying over time.

The results have also shown how flexible the strategic PRLP and PRRP appeals are, which may accommodate the situation of the party and prospective electoral support to different political contexts. Both parties have changed their tactics over time, shifting from a more open strategy in times of upsurge, to more focused and innovative, following times of institutionalisation. On the left, Podemos has turned to the traditional working class as a typical constituency of the left, linked to trade unions and political militancy, whereas Vox has paid more attention to the precarious sectors over time, although this trend fades during the fourth period. This article corroborates the specialisation and contingency of populist actors’ discourse, as we can see how they have adapted to specific contexts in their various phases of development, and therefore confirms previous analyses in this direction.

Research on Podemos (Franze Citation2017; Kioupkiolis & Pérez Citation2019; Roch Citation2024a) has shown the impact of institutionalisation processes on this party, which has downplayed its antagonistic populism and turned to a more conservative strategy relying on traditional symbolic and discursive elements of the left. This can be related to the increasing reliance on the traditional working class when projecting the representation of the people, especially during periods of institutionalisation. By incorporating the concerns of a specific range of workers into their discourse, Podemos aimed to solidify its position as a representative of the working class and strengthen its appeal to a more specific constituency, surrendering the idea of ‘storming the heavens’ (asaltar los cielos in Spanish) and becoming the main left-wing party in Spain by attracting a more diverse electorate.

Regarding Vox, the increasing salience of socioeconomic issues resonates with previous studies on PRRP and welfare chauvinism (Abts et al. Citation2021; Careja & Harris Citation2022), but this study also reveals some aspects of the specific representation of working populations. When it is generally assumed that PRRP refers to the traditional working class as stable and integrated, we find an increasing appeal to precarious sectors. During the birth of its associated trade union Solidarity, Vox innovated by appealing not only to the stable and traditional working population but also to those suffering exclusion, instability, and precariousness. This shift suggests a strategic adaptation in Vox’s messaging to encompass a more diverse set of concerns beyond the focus on cultural and nationalistic issues and the traditional working class. It is open to speculation whether Vox seeks strategically to gain votes in constituencies abandoned by the left and in particular by Podemos. This research´s results show that Vox increases references to socioeconomic class identities over time, including integrated and precarious workers, and thus it appeals to traditional constituencies of the left.

This article innovated in three regards. First, it has analysed the relation between class and populism on the supply side of populism, shedding light on the changing ways populist parties mobilise class identities versus moral identities. Second, at the methodological level, we have employed dictionary-based methods to examine, measure, and compare the various ways populist parties represent class identities and moral identities in their discourses. Our self-designed dictionaries have ensured reliability and precision through the objective selection of words and multiword expressions and multiple rounds of validation checks (Grimmer & Stewart Citation2013; Muddiman, McGregor & Stroud Citation2019; Song et al. Citation2020). Third, the analysis is developed over time, which makes it sensitive to context-bound variation in parties’ discourse. This is important in a context of high vote volatility (Dassonneville Citation2023), which impacts parties’ adoption of innovative strategies to appeal to new or swing voters. This applies especially to populist parties since recent evidence indicates the contingent nature of their populist discourse and the mutable ways to adapt their appeals to ‘the people’ using more concrete and ideologically defined proposals (Bonikowski & Gidron Citation2016; Roch Citation2024a, Mazzolini & Borriello Citation2022; Hunger & Paxton Citation2022).

With the analysis of the Spanish case, we have contributed to the growing field of populism studies by providing a closer look at the relevance of class identities in populist discourses in contexts in which left- and right-wing parties grow in parallel. Spain demonstrates that populist parties on both sides of the ideological spectrum can mobilise social divisions through their definition of the people, although there is still a need to confirm this article’s findings via a cross-national exploration of more populist parties. Due to this study’s approach, we have had access to privileged and detailed measures of Spanish class and moral identities rather than simply the identification of cross-national patterns. However, it is highly probable that the cross-national examination of the relevance of class identities for the supply side of populist parties may offer interesting and surprising insights when comparing left and right. Further research may also explore the causal relationship between the salience of class identities on the supply side and the increase in voting intention on the demand side to reveal how voters respond to a particular party’s appeal, or whether parties adapt to the perceived support of specific socioeconomic groups and class identities.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (926 KB)Acknowledgments

This article has been made possible thanks to the grant PID2022-139755NB-I00 funded by the AEI (10.13039/501100011033) and by the European Union (NextGenerationEU) and the grant SI3/PJI/2021-00384 funded by the Comunidad de Madrid and the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. We would like to express our gratitude for the insightful feedback received from the anonymous reviewers and editors of the journal.

Supplemental data

Supplementary data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2024.2369463

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Juan Roch

Juan Roch is a postdoctoral researcher of political science at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the Free University of Berlin and has been a visiting researcher at the University of Berkeley in 2019 and at the European University Institute in Florence in 2023. He has published numerous book chapters and articles in prestigious international journals such as Political Studies, Journal of European Integration, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, or Nations & Nationalism. He is also the author of the book The populism-Euroscepticism nexus: A discursive comparative analysis of Germany and Spain, published by Routledge.

Guillermo Cordero

Guillermo Cordero is a Professor of Political Science at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM). He has been visiting research fellow at the University of Essex, the University of Michigan, the Universität Mannheim, the Université de Montréal and the University of California, Berkeley. He has published in Political Studies Review, Government & Opposition, Parliamentary Affairs, and West European Politics, among others.

Notes

1 We follow the predominant classification in political science, which characterises Vox and Podemos as radical populist parties on the right and left, respectively. This characterisation is supported by most of the empirical analyses, which demonstrate the populist discourse of Podemos (Mazzolini & Borriello Citation2022; Kioupkiolis Citation2016; Roch Citation2024a) and Vox (see Rama, Cordero & Zagórski Citation2021; Zanotti & Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2022; Galais & Pérez-Rajó Citation2023), although there remains no definitive consensus on the degree of populism of the latter party(Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro & O’Flynn Citation2021).

2 We understand party institutionalisation as the complex process by which political parties consolidate stable organisational structures in the territory and enduring patterns of behaviour, establishing durable electoral support bases that facilitate political representation in the institutions (Mainwaring Citation2016; Scarrow, Wright & Gauja Citation2023).

3 Sumar is a coalition of parties created for the July 2023 national election and encompassing, among others: Movimiento Sumar, Podemos, Izquierda Unida, Más País/Más Madrid, Compromís, Catalunya en Comú, Chunta Aragonesista and Més. Podemos had only five MPs in the overall 31 of the Sumar coalition.

4 In dictionary methods, recall refers to the ability of dictionaries to capture a high number of true positives, that is, positive examples in the textual corpus of the words or multi-word expressions included in a dictionary.

5 Bigrams are multi-word expressions of two words, 3-grams of three words and 4-grams of four words.

6 See a description of the categories at the LIWC website (only completely accessible through payment):https://www.liwc.app/.

7 The translations are our own throughout the text.

References

- Abts, K., Dalle Mulle, E., van Kessel, S. & Michel, E. (2021) ‘The welfare agenda of the populist radical right in Western Europe: combining welfare chauvinism, producerism and populism’, Swiss Political Science Review, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 21–40.

- Akkerman, A., Zaslove, A. & Spruyt, B. (2017) ‘“We the people” or “We the peoples”? A comparison of support for the populist radical right and populist radical left in the Netherlands’, Swiss Political Science Review, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 377–403.

- Angelucci, D. & Vittori, D. (2023) ‘Look where you’re going: the cultural and economic explanations of class voting decline’, West European Politics, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 122–147.

- Askim, J., Karlsen, R. & Kolltveit, K. (2022) ‘Populists in government: normal or exceptional?’, Government and Opposition, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 728–748.

- Aslanidis, P. (2017) ‘Measuring populist discourse with semantic text analysis: an application on grassroots populist mobilization’, Quality & Quantity, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 1241–1263.

- Berman, S. (2021) ‘The causes of populism in the West’, Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 71–88.

- Bonikowski, B. & Gidron, N. (2016) ‘The populist style in American politics: presidential campaign discourse, 1952–1996’, Social Forces, vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 1593–1621.

- Careja, R. & Harris, E. (2022) ‘Thirty years of welfare chauvinism research: findings and challenges’, Journal of European Social Policy, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 212–224.

- Castanho Silva, B., Schürmann, L. & Proksch, S. (2023) ‘Modulation of democracy: partisan communication during and after election campaigns’, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 1–16.

- Cordero, G. & Simón, P. (2016) ‘Economic crisis and support for democracy in Europe’, West European Politics, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 305–325.

- Dassonneville, R. (2023) Voters Under Pressure. Group-Based Cross-Pressure and Electoral Volatility, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- De Cleen, B. & Glynos, J. (2021) ‘Beyond populism studies’, Journal of Language and Politics, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 178–195.

- De Vries, C. E. & Hobolt, S. B. (2020) ’Challenger parties and populism’, LSE Public Policy Review, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 1–8.

- Evans, G., Stubager, R. & Egge Langsæther, P. (2022) ‘The conditional politics of class identity: class origins, identity and political attitudes in comparative perspective’, West European Politics, vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 1178–1205.

- Franze, J. (2017) ‘La trayectoria del discurso de Podemos: del antagonismo al agonismo’, Revista Española de Ciencia Política, vol. 44, no. 44, pp. 219–246.

- Galais, C. & Pérez-Rajó, J. (2023) ‘Populist radical right-wing parties and the assault on political correctness: the impact of Vox in Spain’, International Political Science Review, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 492–506.

- Gidron, N. & Hall, P. A. (2020) ‘Populism as a problem of social integration’, Comparative Political Studies, vol. 53, no. 7, pp. 1027–1059.

- Gómez, R. & Ramiro, L. (2022). Radical Left Voters in Western Europe. Routledge, London.

- Goodwin, M. J. (2014). ‘A breakthrough moment or false dawn? The great recession and the radical right in Europe’, in European Populism and Winning the Immigration Debate, ed C. Sandelind, European Liberal Forum, Stockholm, pp. 15–40.

- Grimmer, J. & Stewart, B. (2013) ‘Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts’, Political Analysis, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 267–297.

- Gründl, J. (2020) ‘Populist ideas on social media: a dictionary-based measurement of populist communication’, New Media & Society, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 1481–1499.

- Häusermann, S. & Kriesi, H. (2015) ‘What do voters want? Dimensions and configurations in individual-level preferences and party choice’, The Future of Democratic Capitalism Conference, Zurich, 18 June 2011.

- Häusermann, S., Kurer, T. & Zollinger, D. (2023) ‘Aspiration versus apprehension: economic opportunities and electoral preferences’, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 1–22.

- Heinisch, R. & Jansesberger, V. (2022) ‘Lacking control. Analysing the demand side of populist party support’, European Politics and Society, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 266–285.

- Heinisch, R. & Werner, A. (2019) ‘Who do populist radical right parties stand for? Representative claims, claim acceptance and descriptive representation in the Austrian FPÖ and German AfD’, Representation, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 475–492.

- Hunger, S. & Paxton, F. (2022) ‘What’s in a buzzword? A systematic review of the state of populism research in political science’, Political Science Research and Methods, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 617–633.

- Hutter, S., Kriesi, H. & Vidal, G. (2018) ‘Old versus new politics: the political spaces in Southern Europe in times of crises’, Party Politics, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 10–22.

- Katsambekis, G. (2020) ‘Constructing ‘the people’ of populism: a critique of the ideational approach from a discursive perspective’, Journal of Political Ideologies, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 53–74.

- Kioupkiolis, A. (2016) ‘Podemos: the ambiguous promises of left-wing populism in contemporary Spain’, Journal of Political Ideologies, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 99–120.

- Kioupkiolis, A. & Pérez, F. S. (2019) ‘Reflexive technopopulism: Podemos and the search for a new left-wing hegemony’, European Political Science, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 24–36.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Romain, L., Martin, D., Simon, B. & Frey, T. (2006) ‘Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: six European countries compared’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 921–956.

- Kriesi, H. & Schulte-Closs, J. (2020) ‘Support for radical parties in Western Europe: structural conflicts and political dynamics’, Electoral Studies, vol. 65, pp. 102138.

- Laclau, E. (2005) On Populist Reason, Verso, London.

- Langsæther, P., Evans, G. & O’Grady, T. (2022) ‘Explaining the relationship between class position and political preferences: a long-term panel analysis of intra-generational class mobility’, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 958–967.

- Laver, M., Benoit, K. & Garry, J. (2003) ‘Extracting policy positions from political texts using words as data’, The American Political Science Review, vol. 97, no. 2, pp. 311–331.

- Linz, J. & Montero, J. R. (1999) ‘The party system of Spain: old cleavages and new challenges’, Working Paper 138, Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales.

- Macanovic, A. (2022) ‘Text mining for social science. The state and the future of computational text analysis in sociology’, Social Science Research, vol. 108, pp. 102784.

- Mainwaring, S. (2016) ‘Party system institutionalization, party collapse and party building’, Government and Opposition, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 691–716.

- Marcos-Marne, H., Plaza-Colodro, C. & O’Flynn, C. (2021) ‘Populism and new radical-right parties: the case of Vox’, Politics.

- Mazzolini, S. & Borriello, A. (2022) ‘The normalization of left populism? The paradigmatic case of Podemos’, European Politics and Society, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 285–300.

- Meijers, M. J. & Zaslove, A. (2021) ‘Measuring populism in political parties: appraisal of a new approach’, Comparative Political Studies, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 372–407.

- Mudde, C. (2004) ‘The populist zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 541–563.

- Mudde, C. (2007) Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Mudde, C. (2021) ‘Populism in Europe: an illiberal democratic response to democratic liberalism (The Government and Opposition/Leonard Schapiro lecture 2019)’, Government and Opposition, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 577–597.

- Mudde, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2012). ’Populism and (liberal) democracy: a framework for analysis’ in Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy?, eds C. Mudde & C. R. Kaltwasser, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 1–26.

- Mudde, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2013) ’Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America’, Government and Opposition, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 147–174.

- Mudde, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018) ‘Studying populism in comparative perspective: reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda’, Comparative Political Studies, vol. 51, no. 13, pp. 1667–1693.

- Muddiman, A., McGregor, S. C. & Stroud, N. J. (2019) ‘(Re)Claiming our expertise: parsing large text corpora with manually validated and organic dictionaries’, Political Communication, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 214–226.

- Müller, J. W. (2016) What is Populism?, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

- Nelson, L. K., Burk, D., Knudsen, M. & McCall, L. (2021) ‘The future of coding: a comparison of hand-coding and three types of computer-assisted text analysis methods’, Sociological Methods & Research, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 202–237.

- Oesch, D. & Rennwald, L. (2018) ‘Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right’, European Journal of Political Research, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 783–807.

- Olivas-Osuna, J. J. & Rama, J. (2022) ’Recalibrating populism measurement tools: methodological inconsistencies and challenges to our understanding of the relationship between the supply- and demand-side of populism’, Frontiers on Sociology, vol. 7, no. 970043.

- Orriols, L. & Cordero, G. (2016) ‘The breakdown of the Spanish two-party system: the upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 general election’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 469–492.

- Pirro, A. L. P., Taggart, P. & van Kessel, S. (2018) ’The populist politics of Euroscepticism in times of crisis: comparative conclusions’, Politics, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 378–390.

- Podemos (2014a) ‘Pablo Iglesias campaign speech, April 2014, Albacete’, available online at: https://rb/gy/2sappe

- Podemos (2014b) ‘Pablo Iglesias campaign speech, January 2014, Gijón’, available online at: https://t.ly/i_Vnd

- Podemos (2014c) ‘Pablo Iglesias campaign speech, May 2014, Soria’, available online at: https://t.ly/xJkEg

- Podemos (2017) ‘Pablo Iglesias campaign speech, December 2017, Barcelona’, available online at: https://rb.gy/2sappe

- Proksch, S. O., Lowe, W., Wäckerle, J. & Soroka, S. (2019) ’Multilingual sentiment analysis: a new approach to measuring conflict in legislative speeches’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 97–131.

- Rama, J., Cordero, G. & Zagórski, P. (2021) ’Three is a crowd? Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox: the end of bipartisanship in Spain’, Frontiers in Political Science, vol. 3, no. 688130.

- Ramaekers, M., Karremans, T., Lubbers, M. & Visser, M. (2023) ’Social class, economic and political grievances and radical left voting: the role of macroeconomic performance’, European Societies, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 444–467.

- Rico Motos, C. & Del Palacio Martín, J. (2023) ’Constructing the enemy: the evolution of Podemos’ populist discourse from anti-system movement to power (2014–2021)’, Journal of Political Ideologies, pp. 1–23.

- Roberts, K. M. (2017). ’Populism and political parties’ in The Oxford Handbook of Populism, eds C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart & P. O. Espejo, Ostiguy Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 287–306.

- Roch, J. (2021) ’Friends or foes? Europe and “the people” in the representations of populist parties’, Politics, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 224–239.

- Roch, J. (2024a) ’De-centring populism: an empirical analysis of the contingent nature of populist discourses’, Political Studies, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 48–66.

- Roch, J. (2024b) The Populism-Euroscepticism Nexus: A Discursive Comparative Analysis of Germany and Spain, Routledge, London.

- Rodríguez-Teruel, J., Barrio, A. & Barberà, O. (2016) ’Fast and furious: Podemos’ quest for power in multi-level Spain’, South European Society and Politics, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 561–585.

- Rodrik, D. (2018) ’Populism and the economics of globalization’, Journal of International Business Policy, vol. 1, no. 1–2, pp. 12–33.

- Rodrik, D. (2021). ’Why does globalization fuel populism? Economics, culture, and the rise of right-wing populism’, Annual Review of Economics, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 133–170.

- Rooduijn, M. (2018) ’What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties’, European Political Science Review, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 351–368.