ABSTRACT

This article investigates practices that engage preservice teachers’ ideas of professionalism within the context of a university-based mentoring programme. The case is explored by observation of mentoring sessions, analysis of documents grounding the mentoring sessions, and mentor and mentee interviews. Practices are investigated through the theory of practice architectures and made the subject of a thematic analysis. The purpose of the investigation is to highlight how practices can contribute to enhancing preservice teachers’ understanding of different aspects of professionalism, particularly those related to expectations of teachers’ professional competence. The findings show how mentoring practices can contribute to widening preservice teachers’ understanding and how contextual factors, like power relations, can come into play in mentoring practices. The analyses illuminate how professionalism is being negotiated in a third space institutionalised in a campus-based mentor programme in teacher education.

Highlights

A mentor programme is understood as an institutionali

mme is understood as an institutionalisation of a third space.

Mentoring practices are studied in terms of practice architectures.

Understanding of teacher professionalism is developed by relating theory and practice.

Power relations are highlighted as essential for how mentoring practices play out.

Introduction

The preparation of future teachers for their professional careers is often described as challenging, particularly the creation in students of a sense of coherence between theoretical and research-based knowledge taught on campus and competence demands in professional teaching practice. The gap metaphor used to describe the relationship between theory and practice can underpin teacher education as structures that are built in separate fields characterised by different and occasionally conflicting values, beliefs, and knowledge (Allen, Citation2009; Korthagen, Citation2010). However, in Norwegian and international teacher education, efforts are made to enhance quality and coherence in teacher education (Lejonberg, Elstad, & Hunskaar, Citation2017; Lund, Jakhelln, & Rindal, Citation2015). Other researchers have argued that there is a need to connect teacher preparation to teacher induction and universities must take the lead in such efforts (Bastian & Marks, Citation2017). They also find that spending more time with mentors can boost initial teacher retention and teaching skills.

In the current study, we investigate one of many quality-focused endeavours in teacher education that helps preservice teachers understand the connection between theoretical and research-based knowledge (theory) and professional teaching practice in schools (practice) through interactions between preservice teachers and mentors in a mentor programme. In the mentor programme focused upon here, called profession-oriented mentoring (PROMO), the learning activities offered are physically located both on campuses and in schools. The practices are led by a mentor, which is an experienced schoolteacher with formal mentor education.Footnote1 PROMO is offered as an addition to traditional teaching on the campus led by teaching staff at the university and placement learning in practice schools mentored by schoolteachers (with or without mentor education). PROMO can be understood as a ‘third space’ (Daza, Gudmundsdottir, & Lund, Citation2021; Lejonberg, Elstad, & Hunskaar, Citation2017; Lillejord & Børte, Citation2016; Zeichner, Citation2010) for student learning. Zeichner (Citation2010) used the term ‘third space’ as a metaphor to describe the creation of ‘hybrid spaces in teacher education, where academic and practitioner knowledge and knowledge that exists in communities come together in new, less hierarchical ways in the service of teacher learning’ (p. 89). According to Zeichner’s work (Zeichner, Citation2010), the third space idea acknowledges that tensions among various types of professional knowledge are part of preservice teachers’ knowledge construction. Bringing experienced teachers from schools to campus courses and activities, like the mentors in PROMO, is one of the examples Zeichner (Citation2010) describes as the creation of a third space for student learning. Thus, PROMO mentors become hybrid teacher educators who cross the boundaries between school and universities and between practice and academic knowledge. Those recruited as PROMO mentors were assumed to possess favourable attributes to assist preservice teachers in this regard, as they navigate among different spheres. The mentors primarily work as teachers in schools; they have received mentor education at the university level, and many of them are also involved in teacher and mentor education as lecturers, seminar leaders, practicum mentors, examiners, and actors participating in research and development work in cooperation with the university.

For the preservice teachers who chose to participate, PROMO is the first of several meetings within a third space understood as efforts made throughout teacher education programmes to address the challenges that arise in connecting theory and practice. When students begin their five-year teacher education programme, they are divided into groups (PROMO groups) based on subject speciality and matched with a PROMO mentor who teaches the same subject as the preservice teachers are studying. Such matching based on subject area are in accordance with research findings that indicate that a fit of mentor-mentee similarities can impact in the mentoring relationship and, eventually, teacher outcomes (Kwok, Mitchell, & Huston, Citation2021). We also know from earlier research that quality mentor relationships can contribute to preservice teachers’ well-being and professional development. Dreer (Citation2021) argued that mentor – mentee relationships should be established early and nurtured over time by continuously working on stable mentee – mentor pairings over time. Efforts are done for the PROMO group and the relationship to the mentor to remain stable through the entire five-year teacher education programme.

In the current study, we investigated preservice teachers’ and mentors’ actions and reflections related to the planning and execution of interaction in the first year of the teacher education and PROMO programme. It is relevant to note that in the teacher education programme illuminated in this work, preservice teachers’ first year of teacher education is taken in different faculties where they study one of the subjects they are to teach in the future. The preservice teachers participating in this study have not yet begun studying pedagogy or subject didactics and, therefore, the PROMO programme constitutes a structured relation to the teacher education programme this first year. This implies that PROMO is a significant structure to help preservice teachers relate the subject knowledge from their different faculties to the role as a schoolteacher. An important focus in this programme is mentors’ contribution to preservice teachers’ understanding of how theory and practice can be linked. In this respect, PROMO can be understood as a measure that aims to create in students a sense of coherence between theoretical knowledge and professional practice as well as between learning on campus and as part of practicum (Hatlevik, Citation2014; Hatlevik & Havnes, Citation2017).

Inspired by Antonovsky’s (Citation1987; Citation1993) concept of the sense of coherence, Hatlevik (Citation2014) argues that students’ perceptions of educational content and demands as being comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful are the core components of sensing coherence in professional education. In teacher education, comprehensibility refers to students’ perception of educational content as understandable. Manageability refers to students’ confidence in their ability to develop skills or access the support and resources required to master educational and professional demands. Meaningfulness refers to students’ perception of educational content as relevant and useful for professional practice (Hatlevik & Havnes, Citation2017; Hatlevik & Hovdenak, Citation2020; Hatlevik, Citation2014). Kvernbekk (Citation2001) argues that the degree to which a given theoretical contribution is experienced as meaningful and relevant to practice depends on actors’ understanding and use of it, not by the inherent features of the theory itself. Professional development requires active knowledge work characterised by a reflective room in which theoretical understanding and practical teaching experience mutually illuminate each other (Chitpin & Evers, Citation2005). However, previous research indicates that numerous schoolteachers to a limited extent translates research-based knowledge to their own practice, which they consider as unique and extremely complex (Cain, Citation2016), and use practical knowledge when they plan their teaching and personal knowledge when they reflect on their teaching (Wieser, Citation2016).

The mentors of preservice teachers may play an important role in contributing to future teachers’ understanding of and use of theoretical and research-based knowledge to plan for, justify, and reflect on professional practice. However, previous studies indicate that contributing to preservice teachers’ linking of theory and practice is difficult to master for mentors. Findings from an investigation of preservice teachers’ perceptions of mentors’ use of theory in practicum conversations indicate that mentors use of theory contributes, to a small extent, to perceived developmental support. Actually, pre-service teachers’ perceived use of theory was found to have a slightly negative association with perceived developmental support (Lejonberg, Elstad, Sandvik, Solhaug, & Christophersen, Citation2018). Further, findings from another study complement the image of efficient theory use in mentoring as overwhelmingly difficult for mentors (Christophersen, Elstad, Solhaug, & Turmo, Citation2016). Although beneficial use of theory in mentoring can be difficult for mentors to master, mentoring is an arena where efforts made to understand practice in light of theory can facilitate and develop critical reflection among preservice teachers (Garrigan & Pearce, Citation1996; Hatlevik, Citation2014; Lejonberg, Citation2016; Lejonberg, Elstad, Sandvik, Solhaug, & Christophersen, Citation2018; Toom, Husu, & Patrikainen, Citation2015). In the current article, we investigate how such work can be done in a third space when mentors and preservice teachers both move between the school and campus context and explore links between theory and practice. Thus, this article provides new knowledge on how mentors with formal mentoring competences working primarily in schools can contribute to developing a sense of coherence between theoretical knowledge and professional practice among preservice teachers. The current work sheds light on the practices adopted by mentors and preservice teachers that are related to the development of preservice teachers into professionals.

The data used in this study is derived from multiple sources: session plans structuring the PROMO programme, mentors’ planning sessions, interaction between preservice teachers and mentors, interviews with mentors and preservice teachers, and surveys among preservice teachers. The theory related to practice architectures has the potential to highlight specific aspects of mentoring new teachers (Kemmis, Heikkinen, Fransson, Aspfors, & Edwards-Groves, Citation2014). In the current study, theory regarding practice architectures is used as a framework for analysing the contributions of mentoring practices to the formation of a connection between theory and practice among preservice teachers. This investigation is based on the following research question: How can mentoring practices in a third space contribute to preservice teachers’ understanding of theory as relevant in practical teaching?

To answer the research question, we have chosen to focus on a core theme in the investigated mentor scheme: teacher professionalism. We investigate how mentors can contribute to mentees’ linking of theory and practice. To illuminate such practices, we investigate activities related to the term ‘teacher professionalism’ understood as the competences teachers require (i.e. what constitutes teachers’ professional competence). Teacher professionalism is a lex but vague concept (Mausethagen, Citation2012). Linda Evans describes professionalism as ‘professionally influenced practice that is consistent with commonly-held consensual delineations of a specific profession and that both contribute to and reflects perceptions of the profession’s purpose and status and the specific nature, range and levels of service provided by, and expertise prevalent within, the profession, as well as the general ethical code underpinning this practice’ (Evans, Citation2008: p. 29). Further, the term professional competence is a multifaceted concept that integrates all that is necessary to manage professional practice (Illeris, Citation2009). Professional practice requires interaction among different types of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and judgement (Sullivan & Rosin, Citation2008). Moreover, the task of the practitioners also includes ‘responsibilities for selecting, validating and in other ways safeguarding knowledge in the context of everyday work, for keeping issues open to investigation, and for taking active steps to explore opportunities for improvement’ (Jensen, Lahn, & Nerland, Citation2012, p. 4). There exists a large body of research on the constitution of teacher competence and knowledge and on various aspects of propositional knowledge (Shulman, Citation1987), personal knowledge (Day & Sachs, Citation2004), societal issues (Ben-Peretz, Citation2011) contextual knowledge, as well as practical knowledge and skills, all of which have been emphasised (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999; Verloop, Van Driel, & Meijer, Citation2001). In short, teachers’ professional competence includes knowing what (subject knowledge) and how (methodological knowledge) to teach as well as how to reflect upon why-related questions linked to educational goals, content, methods of teaching and learning, and the school’s role in society (general pedagogical and subject-specific didactical knowledge) (Carr, Citation1993; Shulman, Citation1987; Winch, Citation2014).

In the following account, we present the theoretical approach to this work by first introducing theory on practice architectures used to illuminate practices within the PROMO structures relevant to the development of mentees’ understanding of teacher professionalism. We then describe how the data were collected and analysed and show how our findings are relevant to the understanding of how mentoring programme structures can contribute to mentor and mentee interactions bringing theory and practice.

Theoretical approach: exploring practice through the lens of practice architectures

In the current contribution, we explore how mentoring practices in a third space can contribute to professionalism. To fulfil such a goal, a theoretical framework developed to unpack aspects of practices is useful. As described by Kemmis et al. (Citation2014), the theory of practice architectures can enable an understanding of professional practice. The approach can illuminate how phenomena interact, as opposed to hierarchical approaches illustrating phenomena placement in relation to other phenomena from a more static perspective. Such a theoretical frame has earlier been used to develop an understanding of mentoring. For example, theory on practice architectures has been used to illuminate how different approaches to mentoring can be understood as describing different projects (Kemmis, Heikkinen, Fransson, Aspfors, & Edwards-Groves, Citation2014), to highlight complexities and variability in mentoring (Lofthouse & Thomas, Citation2014), and as an anchoring of discussions related to ‘good mentoring’ (Pennanen, Bristol, Wilkinson, & Heikkinen, Citation2016). For the purpose of this article, this theoretical lens is used to investigate aspects of the interaction between mentors and preservice teachers in the PROMO programme that are relevant to developing an understanding professionalism in a third space.

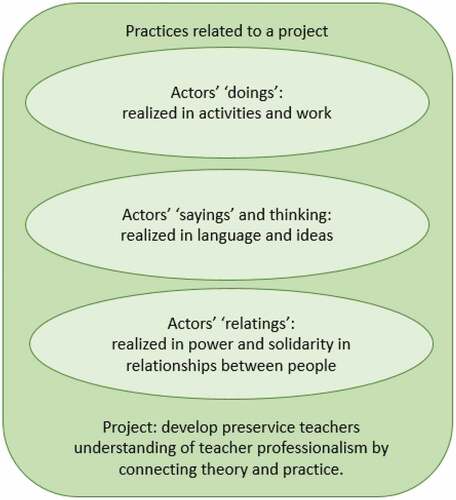

Kemmis, Heikkinen, Fransson, Aspfors, and Edwards-Groves (Citation2014) describe and visualise how practice can be understood by investigating its ‘doings’, ‘sayings’, and ‘relatings’ related to a specific ‘project’ directing the practices. Such a project could be to develop preservice teachers’ understanding and skills to help them become professional teachers. Typical ‘doings’ related to developing preservice teachers’ understanding of teacher professionalism could be preservice teachers leading class discussions in practicum or preparing arguments for discussions regarding the competences teachers must master. Typical ‘sayings’ could be the preservice teachers’ discussions on campus regarding the term ‘teacher professionalism’. More specifically, such sayings could consist of preservice teachers’ and mentors’ comments regarding what teacher professionalism means and how one can develop professionally as a teacher. However, it is important to note that cognition is also considered ‘sayings’ in this framework. Consequently, preservice teachers’ reflections related to a certain discussion or task given by a mentor can be relevant ‘sayings’ that characterise an investigated practice. This implies that we understand sayings as an aspect of collaborative meaning-making.

Further, the term ‘relatings’ is used to denote ‘the affective’ that is realized in power and solidarity – for example, that is available to us through the study of the relationships among people. The relevant ‘relatings’ in the area of focus in the current study could be understood as the relationships between the mentor and the mentees (or between the mentees as a group) or between the mentees. Moreover, the ‘relatings’ between mentees and future pupils and between colleagues and pupils’ parents could be relevant in this matter, as such ‘relatings’ could be a relevant focus for conversations in a mentor programme. Given that the question regarding symmetry and power is assumed to be particularly important in the practice of mentoring (Aspfors, Citation2012; Bjørndal, Citation2008; Moberg & Velasquez, Citation2004), we have chosen to focus on the power aspect when commenting on ‘relatings’ in the current study. These categories are used to analyse the practices that are part of the mentor programme investigated, as illustrated in .

Method and data collection

In this study, inspired by qualitative single case study designs, we conducted an in-depth exploration of the practices constituting PROMO, from different perspectives (Bennett, Citation2004; Yin, Citation2009). To develop understanding of PROMO as a phenomenon, we have explored PROMOs practices within its context based on multiple data sources. The data material consists of data from several sources and are presented in . The activities of PROMO are structured according to subject plans, as presented on the teacher education institution home page. These subject plans were developed by a group that comprised participants from teacher education, mentor education, and school-based mentoring when the structure of PROMO was developed (Source 1 in ).Footnote2 The subject plans then laid the foundation for discussion among the PROMO mentors in meetings at campus. The mentors together operationalised the subject plans, thereby resulting in detailed mentor plans that provided guidelines for sessions with preservice teachers. These guidelines included activities, tasks, and questions to ground discussions (Source 2 in ). At the end of the semester, the mentors participated in an evaluation meeting. The authors of this article were present in these meetings, observing the discussions and taking field notes from mentors’ planning and evaluation meetings (Source 3 in ). The mentor plans then came into play in PROMO sessions at campus and in school visits with mentors and preservice teachers. The authors of this article were present in these sessions and observed the practices and took field notes from PROMO sessions (Source 4 in ).

Table 1. Overview of data sources.

At the end of the second semester of the mentor programme, focus group interviews with preservice teachers were conducted in four groups of two to four persons. The preservice teachers were recruited through self-selection based on the possibility of entering a name if willing to be contacted for further participation in PROMO-related research. Of the 31 preservice teachers who were willing to be contacted for an interview, 12 met for group interviews. Both authors attended the interviews. One conducted the interviews, while the other took notes. The interviews were audio recorded. The transcriptions from the group interview with preservice teachers are also part of the data material (Source 5 in ). Moreover, a group interview with a group of four mentors was held after the second semester. We recruited mentors with experience from different PROMO topics, geographical areas, and school types (lower and higher secondary school mentors). Transcriptions from group interviews with mentors are Source 6 in . Further, observation notes from mentor sessions and school visits together with the other written material formed guides for the semi-structured interviews.

As part of the quality assurance system at the university, all preservice teachers registered at the relevant semester received a survey evaluation by e-mail from the Study Administration (Source 7 in ). Of the 253 preservice teachers, 105 responded. A total of 190 preservice teachers participated in the PROMO1 programme. In PROMO2, 145 of the preservice teachers completed the programme. The second evaluation was conducted by 68 of the 198 preservice teachers in the teacher education programme of that semester. This yielded a response rate of 42% for PROMO1 and 34% for PROMO2. However, of those preservice teachers who participated in PROMO, the response rates were significantly higher – with close to 57% for PROMO1 and 47% for PROMO2, which is an acceptable response rate. Nevertheless, a higher response rate would have been desirable, and we have no basis for claiming that this data is representative of all preservice teachers in PROMO1 and PROMO2.

presents an overview of the data sources.

Analysis

This multifaceted data material was made the object of a theoretically driven thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Silverman, Citation2011), where the data set was selected from the data corpus to extract relevant data to illuminate how mentors and preservice teachers worked to develop an understanding of teacher professionalism. Such an approach to data is based on the assumption that meaning and interpretation are social constructions, and that we – by focusing on talk and interaction – can contribute to understanding of situated contexts and structural conditions that have implications for individuals’ understanding and development. In other words, the data analysis approach is based on an assumption that investigation of mentors’ and mentees’ interaction regarding professionalism within the PROMO structures are relevant to understanding preservice teachers’ professional identity development.

To anchor the thematic analysis, the PROMO subject plans were selected as a starting point. Given that the PROMO subject plans indicate a commitment of the university, through the PROMO mentors, to focusing on particular content, we analysed these plans for content that was illuminated in both PROMO1 and PROMO2 (the first two semesters of teacher education). The theme of professionalism was most prevalent across the plans. The PROMO1 subject plan commits the university through PROMO to contribute to students’ understanding of the teacher profession and reflections regarding teachers’ professional competence. Similarly, the PROMO2 subject plan highlights discussions regarding the content of teacher professionalism and concepts such as profession, professionalism and professional development. In order to illuminate how practices within the PROMO programme can contribute to linking theory and practice related to the selected theme (teacher professionalism), data was analysed by categorising extracts relevant to teacher professionalism. Thereafter, we coded the extracts, defining different practices and the sub-goals of the practices related to the overarching goal of contributing to developing preservice teachers’ understanding of professionalism.

Five practices were selected from the material to illuminate how practices institutionalised by PROMO at different stages expand preservice teachers’ understanding of professionalism: The PROMO subject plans present the university’s intended content, and the meetings in which mentors develop plans and the plans they develop are indicative of mentors’ operationalisation of the anchoring plans and their planned practices in campus-based lessons and school visits. The activities on campus and in school visits present enacted practices and data from surveys, while the interviews present perceived practices and reflections related the PROMO programme. In other words, the thematic analysis focuses on practices institutionalised by PROMO’s goal of contributing to preservice teachers’ understanding of teacher professionalism by relating theory and practice.

Findings

In the following account, we present our findings as described through the lens of practice architectures. This approach highlights how different practices occurring in the material consists of ‘doings’, ‘sayings’, and ‘relatings’, which in turn constitute practices related to the overarching project goal being to develop preservice teachers’ understanding of teacher professionalism. Examples of how designed (planned and actual) practices can contribute to the development of preservice teachers’ understanding of teacher professionalism are visualised by focusing on the ‘sayings’, ‘doings’, and ‘relatings’ of the practices. The presentation organises descriptions in subcategories by features that were found to be characteristic of the selected practices. This implies that it is not a full description of ‘doings’, ‘sayings’, and ‘relatings’ but a representation highlighting characteristic features. In this visualisation, we have represented practices from different sources, thereby resulting in a presentation of practices in different stages (before being conducted, when conducted, and after being conducted). Such a presentation illuminates how practices related to the same project can develop or occur differently in different stages, varying with its source. Such differences can occur as a result of change over time (e.g. the practice was not executed exactly as planned), as a result of the different perspective employed (e.g. actors experience practices differently if they are mentors or preservice teachers), or as a combination of such premises.

provides an overview of illustrating practices related to the ‘project’ of developing mentees’ understanding of teacher professionalism. These practices are elaborated on in the following.

Table 2. Overview of illustrating practices related to the ‘project’ of developing mentees’ understanding of teacher professionalism.

Practice 1: discussing which abilities and skills are called for in job ads and relating this to definitions of teacher professionalism

The first of our five empirical examples presented in the current work is the presentation of a planned practice taken from a mentor session plan (marked Data Source 2 in ). This practice accommodates the given foci from the PROMO subject plans (marked Data Source 1 in ) to highlight teacher professionalism. In the mentor session plan, we find a planned practice described as activities related to ‘defining teacher professionalism’. The descriptions indicate that mentors must include preservice teachers in discussions regarding teacher professionalism and present a theoretical definition of it. However, it appears relevant to mention that no such definition is included in the plan, thereby leaving it to each mentor to provide such theoretical anchoring. To ground the discussion, the plan suggests that preservice teachers and mentors can begin by analysing job ads and note the skills and abilities highlighted as relevant competencies for teachers.

The relevant ‘doings’ that characterise this practice are the analysis of job ads, presentation of a definition of teacher professionalism, and participating in accompanying discussions. This practice lays the groundwork for both mentors’ and mentees’ ‘sayings’, understood as both talk and reflection (Mahon, Francisco, & Kemmis, Citation2017). Mentors are to present a definition of professionalism and mentees are to reflect on mentors’ introduction of theory. Such practice may result in ‘sayings’ in the form of reflection and discussion on teacher professionalism as it is interpreted and deduced from job ads. This planned practice can also be clarified by investigating the ‘relatings’ used in such an activity. Given that in this case job ads are used as a means to explore teacher professionalism, the relation to society (represented through the job ads) is characteristic of this practice. In this case, society could be interpreted as a premise provider that demands certain expertise from preservice teachers. Teacher professionalism in relation to a labour market, steered by supply and demand, is visualised by this practice. The mentor-mentee relationship is characterised by mentors as actors of power (as experienced actors legitimised by their expertise and knowledge of theory regarding professionalism). Such practice can contribute to perceived coherence by developing preservice teachers’ comprehension of the concept of professionalism by relating theoretical with practical perspectives in ‘doings’ and ‘sayings’.

Practice 2: preparing observation of mentors’ interaction with pupils in practice, based on introduced theory regarding teacher professionalism

The second practice selected in this work is also illuminated as a planned practice, as described in a mentor session plan (Data Source 2 in ). The relevant ‘doings’ in this activity are related to mentees preparation of observing interaction with pupils. An observation is planned on campus after the previously described discussions regarding professionalism. The mentor session plan indicated that mentees and mentors should discuss how teacher professionalism, as introduced earlier as based on theory, can be implemented in interactions with pupils. This is then planned to lead to discussions on grounding an agreement ‘on what to observe on the school visit’ to enact and observe teacher professionalism in practice. In other words, the planned practice is a preparation for mentees to observe mentors when they model practice. Preservice teachers’ observations will be structured by a common grounding in theory regarding professionalism and a discussion on how professionalism can be acted out in classrooms. Preservice teachers are required to observe and reflect upon mentors’ practice based on theory. Subsequently, the modelling of practice and mentees’ observations and reflections will lay the groundwork for further thinking and discussion regarding teacher professionalism.

The ‘doings’ of this planned practice involves participating in discussions on what teacher professionalism can ‘look like’ in theory and practice, mentors’ modelling, and mentees’ observation. The relevant ‘sayings’ characterising this observation-related practice involve discussion and reflections regarding professionalism when preparing the observation, mentors’ conversation in class with pupils, and preservice teachers’ reflections regarding how professionalism acts out in practice. Such reflections have the potential to be theory-based, given the grounding discussions on campus. By focusing on the characterising ‘relatings’ in this case, the mentor can be viewed as an actor of power legitimised by the experience of performing teachers’ work in practice. Nevertheless, the mentees can also be characterised as actors of power in this context, as they hold the role of the observer and are also invited to assess mentors’ practice based on the common theoretical grounding. In addition, they are invited to express their personal opinions related to professional performance by teachers in the discussions that are conducted as follow-up on the mentor modelling session. Such sayings can contribute to coherence by widening preservice teachers’ (and mentors’) understanding of teacher professionalism as well as developing an analytical approach that is relevant to managing the teacher role.

Practice 3: reflecting on and discussing the complexity of teacher professionalism

The third example of empirical data selected here to illuminate the linking of theory and practice in mentoring sessions is taken from an observed mentor session (Source 4 in ) where mentors and preservice teachers put into practice the earlier described planned practices. Therefore, the following example is linked to the above-described findings from mentor session plans. In one of the observed mentor sessions, which took place after a school visit, we observed practices where the mentor engaged the preservice teachers in discussions regarding teacher professionalism. This session was grounded in earlier described observations and reflections relevant to challenge and develop mentees’ understanding of the complexity of professional competence. After a discussion on the importance of different kinds of knowledge for a professional teacher, the mentor asked the preservice teachers the following question: ‘Is there anything more to professionalism than knowledge?’ Raising this question was followed by reflections by the preservice teachers on this question on their own, in groups, and in plenary discussions.

Several aspects related to teacher professionalism – such as how to speak to pupils, how personal one should be, and being a good role model – were discussed. Complex and possible contradictory dimensions were also identified, such as possible challenges related to interaction dynamics and loyalty to pupils, parents, and colleagues. The ‘doings’ characterising this practice involve mentors initiating the reflection task with a question and structuring the practice. Preservice teachers’ ‘doings’ are characterised by participating in a discussion regarding the complexity of teacher professionalism and possible dilemmas. The relevant ‘sayings’ in this practice are primarily characterised by preservice teachers’ reflections and discussions regarding the complexity related to teacher professionalism, as mentors assumed a rather distant role in this practice. By focusing on the ‘relatings’ of this practice, the possible empowering functions of practices become apparent, as this practice invites preservice teachers to question and challenge the content of teacher professionalism, based both on theory and on the earlier mentor observation in practice. Nevertheless, a mentor can also be understood as an actor of power who is legitimised by theoretically and experience-based knowledge regarding the complexity of teacher professionalism.

The group interviews with preservice teachers can also provide an indication of how mentors can contribute to broaden mentees’ understanding of teacher professionalism and the complexity of the teacher’s role. In the group interviews, the preservice teachers shared a few general insights they had gained related to theoretical and practice-based discussions when asked how experiences from participating in PROMO were relevant to clarifying teacher professionalism. One preservice teacher expressed that being a part of PROMO made her aware that ‘the teaching profession is not one that everyone can perform’. Another preservice teacher had a similar perception: ‘One gets like a kind of revelation about being a teacher, that there are some expectations toward us as teachers. And it’s good to be aware of it and work actively in teacher education.’ Such statements possibly indicate that PROMO serves as a platform for preservice teachers’ reflections regarding what it means to be a professional teacher and about the complexity of the teaching profession by linking preservice teachers’ understanding of practice to theory.

Similar perceptions were expressed by mentors. According to one mentor: ‘When we discussed the teaching profession and all the dilemmas one must stand in […]. The complexity of the profession struck them’. The preservice teachers’ reflections, as investigated through the current work, present early observations and reflections from preservice teachers at the beginning of the journey to professional teaching. If they had taken part in similar practices at a later stage, other observations and reflections could have been the result. For example, it appears reasonable to assume that as preservice teachers gain more experience and insight in the complexity of the teaching profession, they will interpret observations in a more nuanced manner. The fact that mentors, within the context of the mentor programme investigated here, bring the preservice teachers to observe mentors’ practice with pupils as well as facilitate the processing of thoughts and experiences on campus can be important to broaden the perceptions of preservice teachers regarding the complexity of teacher professionalism. Such practices can contribute to preservice teachers’ perception of coherence by introducing ‘doings’ intended to develop meaning related to the term ‘teacher professionalism’ based on both theoretical and practical perspectives.

Practice 4: observing classroom teaching to identify teacher professionalism

The fourth example selected in this work illuminates how a practice can contribute to preservice teachers’ understanding of one element of the complex competences that professional teachers are required to master. The following example is a referred practice taken from group interviews with preservice teachers (Source 5 in ). In this case, topics arising from preservice teachers’ reflections on school visits were illuminated and further explored in the group interviews. One preservice teacher described how relationships with pupils were the focus for observations in her group. As mentioned earlier, most mentees observed their mentors during school visits. In this particular case, however, the mentor had other obligations on the day of the school visit. Therefore, the mentees observed one of the mentor’s colleagues. One preservice teacher expressed certain reflections and perceptions after the observation:

I saw problems with how he spoke to the pupils […]. I reacted to the categorisation of the pupils. Comments like ‘you are a girl’, ‘stop being so boyish or noisy’. In the reflection with the other preservice teacher afterwards, we discussed this. The other preservice teacher reacted to the same. We think the goal was to make them talk. But it was counterproductive. Not a good way to build relationships.

The above quotation reveals how the observation of practice provides space for grounded reflection and further discussions regarding how a teacher should interact with pupils and build professional relationships. The most relevant ‘doings’ in this practice appear to be the teacher’s teaching of pupils, preservice teachers’ observations, and subsequent discussions. This sequence from the preservice teacher group interview refers to a practice where ‘sayings’ are characterised by an experienced teachers’ discussions with pupils in class and preservice teachers’ reflections and conversations when following up on their observations. A further investigation of the relevant ‘relatings’ in this practice illuminates how mentors have the power to put mentees in empowering roles – for example, by giving them opportunities to observe actual practice and by inviting them to discuss practice based on theory and such observations.

During a discussion in the mentor group interview, one mentor shed light on personal thoughts regarding this practice: ‘What I want to convey is that becoming a blueprint does not work. Let yourself be inspired, but you must find it yourself. One cannot copy. But I can show preservice teachers that I care about the pupils’. Such statements, together with presented findings, also shed light on how modelling can be useful for preservice teachers. By using experienced teachers’ practice as an approach to investigate teacher professionalism, the mentor presents a ‘doing’ intended to trigger ‘sayings’ in order to develop meaning related to the term ‘professionalism’. Such practices can contribute to creating perceived coherence for preservice teachers.

Practice 5: modelling teacher professionalism: introducing preservice teachers to strategies to develop relations with pupils and explain the purpose of such practices

The last example of practices selected from the empirical data in this work is taken from the group interview with mentors (Source 6 in ), referring to another practice that could contribute to mentees’ understanding of the complex competences that professional teachers must master by highlighting how a teacher could employ strategies to build relationships with pupils and develop a beneficial learning atmosphere. On several occasions, the mentors express the importance of using the PROMO seminars as an arena to model the strategies they use with learners in their classrooms. For example, one of the mentors described how she modelled strategies related to relational aspects that, in her opinion, is an essential part of being a professional teacher. When they discussed the importance of building relationships with pupils, she wanted to show the preservice teachers the value of showing interest in the learners. She exemplified this by explaining how she had made an effort to learn all the preservice teachers’ names in their first meeting and elaborated on how this was a strategy to build relations with them. The relevant ‘sayings’ characterising this practice include the mentor’s effort to learn the preservice teachers’ names, using their names throughout the mentor session and, later in the session, expressing this acts as a conscious strategy and the justification of using it.

The ‘doings’ characterising this practice is mentor’s memorising and use of preservice teachers’ names and mentor’s explanation of this practice as a strategy she also employs with pupils. Characterising ‘sayings’ for preservice teachers includes their cognitive perception related to this mentor strategy. In this practice, the relevant ‘relatings’ are characterised by mentors as actors of power, as they use and demonstrate a strategy based on their own experience and are framed as a beneficial approach in preservice teachers’ work. On the contrary, the preservice teachers appear to have a less empowered role in this matter, being objects for a hidden strategy that is revealed later in the lesson when they are invited to reflect on such approaches. However, such practice has the potential to enhance preservice teachers’ meaning-making related to teacher professionalism and thereby equip them with analytical skills relevant to managing their impending profession.

Discussion

In the current study, the theory of architectures (Kemmis et al., Citation2014) is employed to understand mentoring practices as related to the goals of such practices. Based on how such practices are presented in the data, our aim was to unpack practices related to developing preservice teachers’ notion of teacher professionalism. The analysis illuminates practices at different stages, as they were planned and subsequently employed, as they were perceived when implemented and as they were referred to as practices that had been implemented. All investigated practices are related to the overarching project of developing preservice teachers’ understanding of teacher professionalism. Based on an understanding of coherence in teacher education as preservice teachers’ perceptions of educational content and demands of being comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful (Hatlevik & Havnes, Citation2017), the theory of architectures highlights how the sub-goals of each investigated practice are related to the larger goal of preservice teachers relating theory and practice to contribute to their comprehension of professionalism, their ability to manage the teaching profession, and forming an understanding of what the role entails.

For example, the selected practice of introducing a theory on teacher professionalism to prepare the observation of mentors’ interaction with pupils (practice 2) indicates how a sub-goal of anchoring a given observation in theory can contribute to the larger goal of expanding mentees’ understanding of professionalism. The potential of linking mentoring to observation is well known (Schwille, Citation2008; Wang & Odell, Citation2002). Observing mentors’ teaching practice has the potential to drive preservice teachers’ understanding of teaching practice (Zanting, Verloop, & Vermunt, Citation2003). As revealed in the analysis, this practice is characterised by preparing observation by extending a theoretically based discussion and can contribute to ‘sayings’ in the form of theoretically based reflections on how a professional teacher practice can play out. Such interpretation presupposes that such efforts are relevant for preservice teachers to perceive coherence in teacher education (Hatlevik & Havnes, Citation2017).

The use of practice architectures in this work also shed light on how mentors can act in a third space (Daza, Gudmundsdottir, & Lund, Citation2021; Lejonberg, Elstad, & Hunskaar, Citation2017; Lillejord & Børte, Citation2016; Zeichner, Citation2010), for example, by introducing doings to engage preservice teachers in investigating teacher professionalism. Such practice can be driven by mentors’ own sayings and by inviting certain sayings fruitful to extend comprehension of teacher professionalism. Using the theory of practice architecture to investigate the presented practice where mentees observed teaching (Practice 4) puts into practice visualisations of how alternative ‘doings’ can drive different ‘sayings’—in this case, how mentees’ observation of another experienced teacher than their own mentor can invite more critical ‘sayings’. The presented analysis reveals how one of the mentees distanced herself/himself from the observed practice when expressing critical sayings related to the observations that were contrary to his/her comprehension of professional practice. Although others have argued that the observation of one’s own mentor enables the investigation of mentor knowledge and presumptions of practice (Zanting, Verloop, & Vermunt, Citation2003), the findings presented in the current study indicate how preservice teachers can utilise modelling to distance themselves from the practice of experienced teachers. Observing another teacher other than the mentor can encourage mentees to discuss observations freely with their peers and mentor and, thus, foster critical thinking. Such practice is assumed to be relevant to developing a perception of the teaching profession as being manageable as well as equipping pre-service teachers with experiences relevant to developing a complex understanding of teacher professionalism, which corresponds to the second (manageability) and the first (comprehensibility) core components in experiencing a sense of coherence in teacher education (Hatlevik & Havnes, Citation2017).

Further, mentoring relationships are acknowledged as asymmetric, thereby giving mentors the ability to exercise power (Auster, Citation1984; Bjørndal, Citation2008). The focus on ‘relatings’ has the potential to enhance the understanding of mentors’ and mentees’ interactions by applying the perspective of power. Such a focus can shed light on how mentors can initiate practices that have the potential to empower mentees and how mentors can use their power to turn preservice teachers to objects in their own strategy. The included Practice 5, where mentors implemented a hidden strategy regarding learning by using preservice teachers’ names as an approach to build relationships in a new group, can be interpreted as a practice made possible by mentors’ and preservice teachers’ difference in power status. However, such practice can also be interpreted as practice objectify preservice teachers in order to link theory to practice. Moreover, data reveal how practical grounding (in the form of a strategy for building relationships) can give direction to more theoretically grounded follow-up discussion – for example, when mentor and mentees discuss teachers’ strategies for relationship building with students. Such practices can illustrate how mentors can contribute to meaning-making by relating theory and practice, which is the third core component in sensing coherence in teacher education (Hatlevik & Havnes, Citation2017).

Further, aspects related to power and mentoring also become visible when investigating the practice (4) of a mentor modelling one’s own teaching for preservice teachers. Investigating the practice through the lens of visualising ‘relatings’ in the form of power relations lay the groundwork for interpretation of a practice that empowers mentees when inviting them to fill the role of observers and commentators. Although mentors also enact power in this practice, in the role of the experienced teacher, the analysis can contribute to understanding why it takes humility and courage for mentors to invite mentees to reflect upon teacher professionalism based on observations of their own practice. The matching between mentor and mentees are likely to enhance preservice teachers opportunity to relate to mentors contributions to own future practice (Kwok, Mitchell, & Huston, Citation2021).

Understanding a third space as a potential arena of the ‘indirect presence’ of a third aspect (Lejonberg, Elstad, & Hunskaar, Citation2017) highlights how practices, as presented in the current work, can be initiated by mentors and contribute to the interplay between theoretical and practical knowledge. For example, we find in the presented material, practices (2) that introduce theory regarding teacher professionalism to preservice teachers to ground discussions regarding the competences that teachers need to master in practice. Similarly, the notion of power structures in ‘relatings’ shed light on how a practice (1) of the interpretation of job ads can be understood as the indirect presence of a third part by giving society’s expectations the power to ground discussions regarding teacher professionalism.

Implications for practice and further research

The presented findings indicate that a mentor programme like the one described in this work could be understood as a relevant area for discussions regarding the mandate of teachers and ‘relatings’ to society understood through terms such as power and solidarity. The idea of mentor conversations as a space for ‘relatings’ can be fruitful to describe the potential and relevance of mentoring, thereby highlighting how such institutionalisations can function as third spaces (Daza, Gudmundsdottir, & Lund, Citation2021; Lejonberg, Elstad, & Hunskaar, Citation2017; Lillejord & Børte, Citation2016; Zeichner, Citation2010). Through the institutionalization of such designs, we can develop areas for discussions and reflections that empower future teachers and enhance the understanding of their role as the teachers of the future.

However, mentors contributing to mentees’ development, as described in this work, is assumed to be a complex and demanding responsibility. Facilitating beneficial use of theory in mentoring is demanding for mentors to master, but it is believed to be valuable in enhancing preservice teachers’ development towards becoming professional teachers (Garrigan & Pearce, Citation1996; Toom, Husu, & Patrikainen, Citation2015). It is relevant to note that all mentors investigated in the current work have undergone extensive mentor education, most of them have conducted 30 credits (ECTS) of university-based mentor education. some even more. Such schooling, in addition to the mentors’ connection to both the teacher education institution and the practice field, makes the mentors exceptionally well equipped to facilitate the development of mentees’ linking of theory and practice.

Further, the term ‘gap’ has been used by several researchers to describe how values, beliefs, and knowledge can be perceived as conflicting (Allen, Citation2009; Korthagen, Citation2010). Nevertheless, theoretical and practical knowledge can also be understood as phenomena characterised by several common features; several researchers have contributed to nuancing the idea of a gap between theory and practice in teacher education (Christensen, Eritsland, & Havnes, Citation2014; Grimen, Citation2008; Hatlevik & Havnes, Citation2017; Lundsteen & Edwards, Citation2013; Sjøli, Citation2016). For example, Sjølie (Citation2016) suggests that the focus must be moved from closing the fictive gap between theory and practice to the support of preservice teachers who are navigating between different practices and developing ‘skills to anticipate and respond productively to differences and tensions’ (p. 59). Given such approaches to understanding the relevance of theory and practice in teacher education, we argue that the findings presented in this work are relevant in a more principal discussion regarding what it means to use theory and how mentors can contribute to practices that challenge mentees’ understanding of the relationship between theory and practice. For example, challenging mentees’ understanding related to the teacher’s role by encouraging them to reflect on what competences teachers need to master can be understood as interaction relevant to develop the understanding of teacher professionalism by relating theory and practice. Similarly, mentors inviting mentees to reflect upon teaching they have observed can provide a framework for setting practical and theoretical justifications into play. However, if such thoughts are not phrased in theoretical terms and refer to explicit research or theory, is it then ‘use of theory’?

As reflection related to practice can be understood in different ways, the notion of ‘sayings’, ‘doings’, and ‘relatings’ as different aspects of practices can be understood in light of different forms of reflection. Refection in action, on action, and over action are used to indicate how reflection can play out in different stages related to a practice (Convery, Citation1998; Schön, Citation1983, Citation1987). Such an approach to understanding reflection can shed light on how ‘sayings’, ‘doings’, and ‘relatings’ can appear at different stages of a practice and also promote, or constitute, reflection in different forms. For example, a given ‘saying’ in the form of a verbal statement can promote reflection over action for a listening preservice teacher and simultaneously be understood as an expression of reflection in action by the one who stated the ‘saying’. Such relationships among ‘sayings’, ‘doings’, and ‘relatings’ on the one hand and different forms of reflection on the other could be an interesting subject for further analysis of mentoring practices.

It must be emphasized that data in the current work suffer from relevant limitations due to issues such as sample size and methodological approach. The sample size is small, and interviewees were recruited based on voluntariness. Such an approach could enhance the impression that students found the investigated design meaningful for own development. Further efforts to recruit students with more critical opinions towards PROMO – for example, those who did not conduct the program – could have challenged the impression of PROMO as an advantageous design in teacher education. However, the aim of this article was to describe practices taking place within the program through a sample taken from students who chose to participate. Further, there are also limitations related to observation as method. Although both authors observed the lessons included in the data material to compare and secure the data, there are always potential biases related to observations; for example, it could be that our presence in the lessons influenced the discussions. However, despite such limitations, we argue that the findings presented within this work have the potential to illuminate how mechanisms within an institutionalized mentoring program have the potential to enhance the linking of theory and practice among students. The mentioned limitation can direct further research, for example, within other contexts and with larger samples.

Another relevant issue to investigate further is how interactions like those described here can take place in different contexts. When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, teacher education institutions had to identify alternative platforms to support preservice teachers. In line with other mentoring programs for preservice teachers (such as described by Goodrich, Citation2021; Kier & Clark, Citation2020), PROMO was also moved to digital surroundings. Given that the relationships between mentors and mentees were already established, the first impression is that the transition to digital surroundings worked satisfactorily due to mentors’ effort to promote student activity and reflection in digital tools like Zoom. Others have found that mentoring adapted to online tools is characterized by constraints and limitations, although such interaction also can engage students in debates on the theory and practice of teaching (Flores & Gago, Citation2020). Structured empirical evidence regarding how interaction in PROMO was adapted to accommodate restrictions and digital soundings could add to mentoring knowledge, for example, regarding relevant strategies to promote growth through online mentoring (Mullen, Citation2020).

Conclusion

The findings presented in this work explore how a mentor programme can be understood as an institutionalisation of a third space, which is created by mentors to contribute to preservice teachers’ linking of theory and practice. The theory of practice architecture’s division of practices into ‘doings’, ‘sayings’, and ‘relatings’ is a potent tool that allows us to dissect compound practices and can contribute to broadening our understanding by introducing new perspectives. The presented practices drawn from the empirical material visualise how practices in a mentor programme can be both practically and theoretically grounded and have the potential to enhance comprehension and develop experiences that are valuable to the management of the teaching profession. Focusing on ‘relatings’ also has the potential to enhance the understanding of how mentors’ and mentees’ work as part of a mentor programme can take advantage of the potential related to establishing third spaces in teacher education. Based on the presented analysis, we also argue that the investigated practices have the potential to contribute to preservice teachers’ linking of theory and practice, and thereby develop their understanding of teacher professionalism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For more information about this mentor education, see Lejonberg, Elstad, & Christophersen (Citation2015).

2 The authors of this article were also part of this group.

References

- Allen, J. M. (2009). Valuing practice over theory: How beginning teachers re-orient their practice in the transition from the university to the workplace. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 647–654. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.11.011

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unravelling the mystery of health—how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Antonovsky, A. (1993). Complexity, conflict, chaos, coherence, coercion, and civility. Social Science & Medicine, 37(8), 969‒974. doi:10.1016/0277-

- Aspfors, J. (2012). Induction practices: Experiences of newly qualified teachers. Retrieved from: https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/85054

- Auster, D. (1984). Mentors and protégés: Power-dependent dyads. Sociological Inquiry, 54(2), 142–153. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.1984.tb00053.x

- Bastian, K. C., & Marks, J. T. (2017). Connecting teacher preparation to teacher induction. American Educational Research Journal, 54(2), 360–394. doi:10.3102/0002831217690517

- Bennett, A. (2004). Case study methods: Design, use, and comparative advantages. Models, Numbers, and Cases: Methods for Studying International Relations, 2(1), 19–55.

- Ben-Peretz, M. (2011). Teacher knowledge: What is it? How do we uncover it? What are its implications for schooling? Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.015

- Bjørndal, C. R. P. (2008). Bak veilUniversity ofedningens dør: symmetri og asymmetri i veiledningssamtaler [Behind the mentoring door: symmetry and asymmetry in mentoring conversations] ( Doctoral dissertation). University of Tromsø, Norway. Munin Open Research Archive. Retrieved from: https://hdl.handle.net/10037/7092

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cain, T. (2016). Research utilisation and the struggle for the teacher’s soul: A narrative review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(5), 616–629. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1252912

- Carr, D. (1993). Questions of competence. British Journal of Educational Studies, 41(3), 253–271.

- Chitpin, S., & Evers, C. W. (2005). Teacher professional development as knowledge building: A Popperian analysis. Teachers and Teaching, 11(4), 419–433. doi:10.1080/13450600500137208

- Christensen, H., Eritsland, A. G., & Havnes, A. (2014). Curricula in teacher education. Bridging the gap? Students’ attitudes about two learning arenas in teacher education. A study of secondary teacher students’ experiences in university and practice. In E. Arntzen (Ed.), Proceedings of the Conference Educating for the Future, 2013. Halden, Norway, Association for Teacher Education in Europe.

- Christophersen, K.-A., Elstad, E., Solhaug, T., & Turmo, A. (2016). Antecedents of student teachers’ affective commitment to the teaching profession and turnover intention. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 270–286. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1170803

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1999). Relationships of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. Review of Research in Education, 24(1), 249–305.

- Convery, A. (1998). A teacher’s response to ‘reflection‐in‐action’. Cambridge Journal of Education, 28(2), 197–205. doi:10.1080/0305764980280205

- Day, C., & Sachs, J. (2004). Professionalism, performativity and empowerment: Discourses in the politics, policies and purposes of continuing professional development. In International handbook on the continuing professional development of teachers (pp. 3–32). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Daza, V., Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Lund, A. (2021). Partnerships as third spaces for professional practice in initial teacher education: A scoping review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103338. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103338

- Dreer, B. (2021). The significance of mentor–mentee relationship quality for student teachers’ well-being and flourishing during practical field experiences: A longitudinal analysis. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 10(1), 101–117. doi:10.1108/IJMCE-07-2020-0041

- Evans, L. (2008). Professionalism, professionality and the development of education professionals. British Journal of Educational Studies, 56(1), 20–38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.00392.x

- Flores, M. A., & Gago, M. (2020). Teacher education in times of COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: National, institutional and pedagogical responses. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 507–516. doi:10.1080/02607476.2020.1799709

- Garrigan, P., & Pearce, J. (1996). Use theory? Use theory! Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 4(1), 23–31. doi:10.1080/0968465960040103

- Goodrich, A. (2021). Online peer mentoring and remote learning. Music Education Research, 23(2), 256–269. doi:10.1080/14613808.2021.1898575

- Grimen, H. (2008). Profesjon og kunnskap. [Profession and knowledge. In A. Molander & L. I. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier [Studies of professions] (pp. 71–86). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hatlevik, I. K. R. (2014). Meningsfulle sammenhenger : en studie av sammenhenger mellom læring på ulike arenaer og utvikling av ulike aspekter ved profesjonell kompetanse hos studenter i sykepleier-, lærer- og sosialarbeiderutdanningene. [Sense of coherence. A study of relationships between learning in different arenas and development of various aspects of professional competence among students in initial nursing, teaching and social work programmes]. [ Doctoral thesis]. Høgskolen i Oslo og Akershus, Norway.

- Hatlevik, I. K. R., & Havnes, A. (2017). Perspektiver på læring i profesjonsutdanninger. Fruktbare spenninger og meningsfulle sammenhenger. [Perspectives on learning in professional educations. Tensions and meaningful coherence. In J.-C. Smeby & S. Mausethagen (Eds.), Kvalifisering til profesjonell yrkesutøvelse [Qualifying for professional careers] (pp. 191–203). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hatlevik, I. K. R., & Hovdenak, S. S. (2020). Promoting students’ sense of coherence in medical education using transformative learning activities. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 807–816. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S266960

- Illeris, K. (2009). Competence, learning and education: How can competences be learned, and how can they be developed in formal education? In K. Illeris (Ed.), International perspectives on competence development: Developing skills and capabilities (pp. 83–98). Routledge.

- Jensen, K., Lahn, L. C., & Nerland, M. (2012). Introduction. In K. Jensen, L. C. Lahn, & M. Nerland (Eds.), Professional learning in the knowledge society (pp. 1–24). Sense Publishers.

- Kemmis, S., Heikkinen, H. L. T., Fransson, G., Aspfors, J., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2014). Mentoring of new teachers as a contested practice: Supervision, support and collaborative self-development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 154–164. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.001

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Springer.

- Kier, M., & Clark, K. (2020). The Rapid Response of William & Mary’s School of Education to Support Preservice Teachers and Equitably Provide Mentoring to Elementary Learners in a Culture of an International Pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 321–327.

- Korthagen, F. A. (2010). How teacher education can make a difference. Journal of Education for Teaching, 36(4), 407–423. doi:10.1080/02607476.2010.513854

- Kvernbekk, T. (2001). Om pedagogikkens faglige identitet. [About the professional identity of pedagogy. In T. Kvernbekk (Ed.), Pedagogikk og lærerprofesjonalitet [Pedagogy and teacher professionalism] (pp. 17–30). Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Kwok, A., Mitchell, D., & Huston, D. (2021). The impact of program design and coaching support on novice teachers’ induction experience. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 1–28.

- Lejonberg, E. (2016). Hva kan bidra til god veiledning? En problematisering basert på veilederes og veisøkeres perspektiver på veiledning av begynnende lærere. [What can contribute to good mentoring? A problematization based on mentors and mentees perspectives on mentoring of beginning teachers]. [ Doctoral thesis]. University of Oslo, Norway.

- Lejonberg, E., Elstad, E., & Christophersen, K.-A. (2015). Mentor education: Challenging mentors’ beliefs about mentoring. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 4(2), 142–158.

- Lejonberg, E., Elstad, E., & Hunskaar, T. S. (2017). Behov for å utvikle «det tredje rom» i relasjonen mellom universitet og praksisskoler [The need to develop “the third space” in the relation between the university and the practice field]. Uniped, 40(1), 68–85. doi:10.18261/ISSN.1893-8981-2017-01-06

- Lejonberg, E., Elstad, E., Sandvik, L. V., Solhaug, T., & Christophersen, K.-A. (2018). Developmental relationships in schools: Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of mentors’ effort, self-development orientation, and use of theory. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 26(5), 524–541. doi:10.1080/13611267.2018.1561011

- Lillejord, S., & Børte, K. (2016). Partnership in teacher education–a research mapping. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(5), 550–563. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1252911

- Lofthouse, R., & Thomas, U. (2014). Mentoring student teachers; a vulnerable workplace learning practice. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education.

- Lund, A., Jakhelln, R., & Rindal, U. (2015). Fremgragende lærerutdanning—hva er det og hvordan kan vi få det? [Excellent Teacher Education - what is it and how can we achieve it?]. In U. Rindal, A. Lund, & R. Jakhelln (Eds.), Veier til fremragende lærerutdanning [Roads to excellent teacher education]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Lundsteen, N., & Edwards, A. (2013). Internship: Navigating the practices of an investment bank. In G. Wells & A. Edwards (Eds.), Pedagogy in higher education: A cultural historical approach (pp. 155–168). Cambridge University Press.

- Mahon, K., Francisco, S., & Kemmis, S. (2017). Exploring education and professional practice. Springer.

- Mausethagen, S., & Granlund, L. (2012). Contested discourses of teacher professionalism: Current tensions between education policy and teachers’ union. Journal of Education Policy, 27(6), 815–833.

- Moberg, D. J., & Velasquez, M. (2004). The ethics of mentoring. Business Ethics Quarterly, 14(1), 95–122. doi:10.5840/beq20041418

- Mullen, C. A. (2020). Online doctoral mentoring in a pandemic: Help or hindrance to academic progress on dissertations?. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education.

- Pennanen, M., Bristol, L., Wilkinson, J., & Heikkinen, H. L. (2016). What is ‘good’ mentoring? Understanding mentoring practices of teacher induction through case studies of Finland and Australia. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 24(1), 27–53. doi:10.1080/14681366.2015.1083045

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Schwille, S. A. (2008). The professional practice of mentoring. American Journal of Education, 115(1), 139–167. doi:10.1086/590678

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–23. doi:10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Silverman, D. (2011). Interpreting qualitative data. SAGE Publications.

- Sjølie, E. (2016). Å lære teori; en studie av lærerstudenters læringspraksiser [To learn Theory; a study of preservice teachers learning practices. In A.-L. Østern & G. Engvik (Eds.), Veiledningspraksiser i bevegelse. Skole, utdanning og kulturliv [Mentoring practices in motion. Schools, education and cultural life]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Sullivan, W. M., & Rosin, M. S. (2008). A new agenda for higher education: Shaping a life of the mind for practice. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass.

- Toom, A., Husu, J., & Patrikainen, S. (2015). Student teachers’ patterns of reflection in the context of teaching practice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 320–340. doi:10.1080/02619768.2014.943731

- Verloop, N., Van Driel, J., & Meijer, P. (2001). Teacher knowledge and the knowledge base of teaching. International Journal of Educational Research, 35(5), 441–461. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00003-4

- Wang, J., & Odell, S. J. (2002). Mentored learning to teach according to standards-based reform: A critical review. Review of Educational Research, 72(3), 481–546. doi:10.3102/00346543072003481

- Wieser, C. (2016). Teaching and personal educational knowledge-conceptual considerations for research on knowledge transformation. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(5), 588–601. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1253673

- Winch, C. (2014). Education and broad concepts of agency. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(6), 569–583.

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zanting, A., Verloop, N., & Vermunt, J. D. (2003). How do student teachers elicit their mentor teachers’ practical knowledge? Teachers and Teaching, 9(3), 197–211. doi:10.1080/13540600309383

- Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college-and university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 89–99. doi:10.1177/0022487109347671