ABSTRACT

This article develops a conceptual taxonomy of five emerging digital citizenship regimes: (i) the globalised and generalisable regime called pandemic citizenship that clarifies how post-COVID-19 datafication processes have amplified the emergence of four intertwined, non-mutually exclusive, and non-generalisable new techno-politicalised and city-regionalised digital citizenship regimes in certain European nation-states’ urban areas; (ii) algorithmic citizenship, which is driven by blockchain and has allowed the implementation of an e-Residency programme in Tallinn; (iii) liquid citizenship, driven by dataism – the deterministic ideology of Big Data – and contested through claims for digital rights in Barcelona and Amsterdam; (iv) metropolitan citizenship, as revindicated in reaction to Brexit and reshuffled through data co-operatives in Cardiff; and (v) stateless citizenship, driven by devolution and reinvigorated through data sovereignty in Barcelona, Glasgow, and Bilbao. This article challenges the existing interpretation of how these emerging digital citizenship regimes together are ubiquitously rescaling the associated spaces/practices of European nation-states.

Introduction

COVID-19 has hit European digital citizens dramatically, not only creating a generalised risk-driven environment encompassing a wide array of biopolitical vulnerabilities but also exposing them to pervasive digital risks, such as biosurveillance, misinformation, and algorithmic threats to e-democracy (Cheney-Lippold Citation2011; Foucault Citation2003). Over the course of the pandemic, a debate has emerged about the appropriate techno-political response when national and city-regional governments use disease surveillance technologies to address the spread of COVID-19, illustrating the dichotomy between state-Leviathan cybercontrol and protection of civil liberties and further resulting in techno-political and city-regional dynamics in certain urban areas (Calzada Citation2018a; Isin and Ruppert Citation2020; Kitchin Citation2020).

As such, the pandemic crisis, and the advent of the post-COVID-19 biopolitical times, has explicitly intensified the way algorithms and data directly affect citizens’ ordinary life by further provoking their awareness of their own digital rights and thus encouraging local and regional governments to take the lead through a proactive techno-political response (Calzada Citation2021d; Fourcade Citation2021). Thus, post-COVID-19, as an ongoing biopolitical continuum since the pandemic outbreak began, is defined in this article as an uncertain era with a profound algorithmic aftermath which has enabled the emergence of new forms of digital citizenship very much dependent on specific locations. This context-aware path-dependency is more selective than universal in that specific locations are particularly represented through emancipatory imaginaries, political representations, data-related practices, and eventually and gradually, even altering algorithmically the highly mediated relationship between citizens and nation-states by challenging the existing interpretation of the notion of the latter (Cheney-Lippold Citation2017).

In these unprecedented post-COVID-19 biopolitical times, these dynamics may have fostered pervasively new modes of being a digital citizen (Isin and Ruppert Citation2015; Isin Citation2012; Bigo, Isin, and Ruppert Citation2019; Nyers Citation2006; Hintz, Dencik, and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2017) in certain urban areas while unwittingly or deliberately contributing to rescaling – not eroding or dismantling – the nation-state in Europe (Agnew Citation2017; Bianchini Citation2017; Calzada Citation2020a; Henderson, Jefferey, and Wincott Citation2013; Jonas and Wilson Citation2018; Keating Citation2013; Sassen Citation2002; Schou and Hjelholt Citation2018). On the one hand, regarding the techno-political awareness of data, these dynamics involve addressing concerns about biometric technologies (e.g. vaccine passports), rolling out algorithmic identity tools for citizenship (e.g. the ongoing e-Residency policy framework) and engaging in counter-reaction to extractivist data models (e.g. through digital rights claims). On the other hand, they relate to the increasing socio-economic re-foundational awareness and counterreaction (e.g. through internal post-Brexit response in Wales) and city-regional self-confidence through community empowerment (e.g. through data co-operatives) as well as socio-political self-determination through devolution (and independence) and demands in favour of the right to decide (e.g. on indigenous data sovereignty; Kukutai and Taylor Citation2016).

This article is structured as follows: In the next section, it presents the context in which emerging digital citizenship regimes are rescaling European nation-states through the associated state spaces and practices in the post-COVID-19 era. In the third section, it introduces the emerging globalised digital citizenship regime called (i) pandemic citizenship to clarify how post-COVID-19 datafication processes (van Dijck Citation2014) have fostered the emergence of interrelated, non-mutually exclusive, and non-generalisable techno-politicalised and city-regionalised digital citizenship regimes in urban areas of certain European nation-states. Then, the article elucidates these regimes: (ii) algorithmic citizenship, which is driven by blockchain and underpins Tallinn’s e-Residency policy framework; (iii) liquid citizenship, driven by dataism (the deterministic ideology of Big Data) and contested through the claiming of digital rights in Barcelona and Amsterdam; (iv) metropolitan citizenship, as revindicated in reaction to Brexit and reshuffled through data co-operatives in Cardiff; and (v) stateless citizenship, driven by devolution and reinvigorated through data sovereignty in Barcelona, Glasgow, and Bilbao. Finally, this article offers concluding remarks on this taxonomy and discusses some its limitations and future research avenues.

Context: how emerging digital citizenship regimes are rescaling European Nation-States in the Post-COVID-19 realm

Euphoria over the digital renaissance and the advent of the Internet as a free network of networks have characterised the first two decades since the dawn of the new millennium. Recent years have witnessed widening concerns about the surveillance effects of the digital revolution (van Dijck Citation2014). Expressions such as algocracy, digital panopticon, and algorithmic surveillance have revealed a spreading scepticism about the rise of new governance models based on Big Data analysis and Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI is the intelligence demonstrated by machines, as opposed to the natural intelligence displayed by humans. Consequently, AI allows machines to increasingly approach human capacities for perception and reasoning in narrow domains (Dyer-Witheford, Kjosen, and Steinhoff Citation2019). The Cambridge Analytica scandal in the UK offered a dystopian representation of our digital present. These issues have given rise to an urge to systematically address the question of whether and to what extent ubiquitous dataveillance is compatible with citizens’ digital being (Floridi Citation2020).

Furthermore, against this post-COVID-19 backdrop, the global phenomenon of algorithmic disruption has intensified, with new consequences – such as hypertargeting through data analytics, facial recognition, and individual biometric profiling – perceived by many as threats and resulting in undesirable outcomes such as massive manipulation and control via a surveillance capitalism push in the United States (US) (Zuboff Citation2019) and Social Credit Systems in China (Brown, Davidovic, and Hasan Citation2021; Kostka and Antoine Citation2020; Vinod and Prabaharan Citation2020). In contrast, against the backdrop of the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), in Europe – unlike the US and China, which are characterised by AI and data governance paradigms commanded by big tech corporations and super-state power, respectively – a debate emerged, extending beyond nation-states and playing out primarily in European city-regions (Calzada Citation2015), regarding the role of citizens and their relationship with data. The emergence of algorithmic disruption has spurred a call to action for city-regions in Europe, establishing the need to map out the techno-political debate on datafication processes or dataism, Big Data’s deterministic ideology (Lohr Citation2015; Harari Citation2018; van Dijck Citation2014). Moreover, this disruption has highlighted the potential requirements for establishing regulatory frameworks to protect citizens’ digital rights and facilitate data sovereignty, altruism, and donations through data co-operatives (Scholz and Calzada Citation2021). At the same time, this process has resulted in a hollowing-out of nation-state space through rescaling, undermining its heretofore privileged position as the only natural platform and geographical expression for the monopoly of sensory and political power so far (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020; Moisio et al. Citation2020), and further creating techno-political and city-regional dynamics inside states’ borders while paradoxically reinforcing their external borders (Chouliaraki and Georgiou Citation2022; Dijstelbloem and Broeders Citation2015; König Citation2016; Latonero and Kift Citation2018; Shachar Citation2018). Such frameworks cover demands for data privacy, ownership, sovereignty, donation, co-operation, self-determination, trust, access, and ethics as well as AI transparency, algorithmic automatization, and, ultimately, democratic accountability for digital citizenship, which inevitably may transform our current interpretation of the nation-state as ‘the clear and coherent mapping of a relatively culturally homogeneous group onto a territory with a singular and organized state apparatus of rule’ (Agnew Citation2017, 347) and its relationship with digital citizenship.

Broadly, studies on citizenship have combined the right of soil or birthright citizenship (jus soli) and the right-of-blood citizenship (jus sanguinis) (Sadiq Citation2008). While the jus soli principle states that a person’s citizenship is determined by the place where the person was born, the jus sanguinis principle states that citizenship rather is granted when one or both parents are citizens of the state. Moreover, recent post-COVID-19 biopolitical dynamics demand further empirical, timely, and ambitious inter-disciplinary research on the right to algorithmic transparency, borderless residency, digital rights and privacy, data co-operatives, donation and altruism, data sovereignty (jus nexum), and overall democratic city-regional accountability (jus algoritmi). Such approaches have advanced our knowledge of the relationship between the rescaling of nation-states and the emergence of new forms of citizenship in Europe (Arrighi and Stjepanović Citation2019). Thus, this article adopts an interdisciplinary standpoint to open new pathways of enquiry on how European nation-states’ rescaling can be interrogated through a digital citizenship approach drawing from the fields of regional studies, social innovation studies, critical data science, digital studies, and political geography.

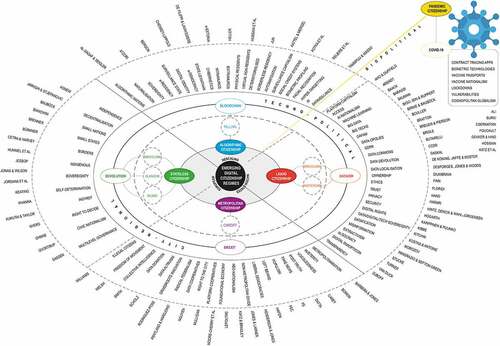

Although ‘digital citizenship is typically defined through people’s action, rather than by their formal status of belonging to a nation-state and the rights and responsibilities that come with it’ (Hintz, Dencik, and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2017, 731), by contrast, this article, opening the Citizenship Studies special issue entitled Digital Citizenship in the Post-Pandemic Urban Realm, aims to challenge the existing interpretation of how five emerging digital citizenship regimes together are ubiquitously rescaling the current conceptualisation of European nation-states in relation to datafied and surveillance societies. In doing so, the article questions whether in the post-COVID-19 European realm, borders – as they are being reinforced externally and are liquifying the lives of citizens internally – still matter as much as nation-states, although the current significance of both might be shifting rapidly and the latter being rescaled accordingly (Bauman Citation2000). To provide several pieces of evidence on this, the article presents a highly generalisable, emerging, globalised digital citizenship regime called (i) pandemic citizenship – to further develop a prior and preliminary taxonomy proposed by the author, based on four ideal types (Calzada Citation2020a) – as well as four unique, non-generalisable, and interrelated emerging citizenship regimes that are techno-politicised and city-regionalised, identifying and examining them in certain urban areas. Overall, pandemic citizenship is a necessary and novel term insofar as state-citizenship relations have been highly mediated through data and algorithms in the post-COVID-19 era by demanding in-depth examination of the transformations in several digital citizenship regimes. These regimes include (ii) algorithmic, (iii) liquid, (iv) metropolitan, and (v) stateless citizenship; these intertwined citizenship regimes are not necessarily mutually exclusive and overlap to greater or lesser degrees (Turner Citation2017). A formulation of this expanded and updated taxonomy of five digital citizenship regimes is presented in by providing and thus validating internal and external differences, similarities, and exceptions of this taxonomy.

Table 1. A conceptual digital citizenship taxonomy: One globalised/generalisable and four non-generalisable/techno-politicised/city-regionalised digital citizenship regimes (Rescaling European Nation-States) (Stemming/adapted/extended from and inspired by Calzada Citation2020a).

Table 1. (Continued).

The five intertwined emerging digital citizenship regimes discussed here – the generalisable one as pandemic and the non-generalisable four as algorithmic, liquid, metropolitan, and stateless – are significant for two key reasons. First, they are novel, dynamic, and real-time representations of the permanent processes of reconstitution of digital citizenship within nation-states in liberal democracies, actually attempting to overcome the conventional static analysis of the increasingly brittle relationship between citizenship and the state by suggesting nuanced explanations featuring a diverse set of drivers of rescaling (such as COVID-19, blockchain, dataism, Brexit, and devolution). Second, and consequently, they are constantly in flux and are rescaling nation-states in an unexpected fashion by altering techno-political and city-regional configurations that directly affect digital citizenship by either undermining or bolstering citizens’ rights to have digital rights (Calzada Citation2021d). As a result of this rescaling of nation-states in Europe, since external borders are solidifying while citizens’ lives are liquifying and the influence of digital forms of being is increasing, the concept of citizenship is in flux; in this context, the urban is a quintessential setting to investigate the global swing towards pandemic citizenship regimes and forms (Calzada Citation2021a).

The emerging globalised digital citizenship regime: pandemic citizenship

As increasingly proven in the aftermath of the pandemic lockdowns, citizens in Europe today are increasingly (though unwittingly) digitally connected through AI and machine-learning devices that remain unevenly and pervasively distributed, fuelling a liquid sense of globalised pandemic citizenship (Bridle Citation2016; Khanna Citation2016). This liquid sense of citizenship has been driven by a general biopolitical dynamic worldwide – rather selective than universal though – and has contributed to state rescaling through a diverse set of city-regional and techno-political dynamics in particular urban areas in Europe, as shown in .

Furthermore, citizens in Europe have likely been pervasively surveilled during and probably as a result of the COVID-19 crisis (Aho and Duffield Citation2020; Csernatoni Citation2020). Alongside this, although vaccine production has sped up, equitable global distribution of vaccine cannot be ensured (Burki Citation2021). The coronavirus does not discriminate and affects citizens translocally, yet it has unevenly distributed biopolitical impacts across and within state borders, producing an ongoing pandemic citizenship regime that exposes health, socio-economic, cognitive, and even digital vulnerabilities. Nonetheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has also shown that digital platforms and transformations offer opportunities in several city-regions even during times of crisis to connect with local communities and attempt to secure the data commons, allow the creation of data co-operatives (Scholz and Calzada Citation2021; Calzada Citation2020b), and nurture data sovereignty (Calzada Citation2021b).

However, can e-democracy be ensured for all citizens and democratic citizenship further structured to avert consolidation of the algorithmic and data-opolistic (see Stucke Citation2018 data oligopolies) extractivist hegemonic paradigm shaped by Big Tech firms? Similarly, can the Orwellian cybercontrol that serves as the nation-state’s Leviathan digital panopticon be subvert, thus ensuring citizens’ digital rights (Calzada Citation2021; Gekker and Hind Citation2019; Masso and Kasapoglu Citation2020)?

Cybercontrol through mass contact-tracing applications on mobile phones, biometric technologies, and vaccine passports have raised a vibrant debate on vaccine nationalism (ALI Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Ammann Citation2020; Bieber Citation2020; Katz et al. Citation2021; Nguyen Citation2017; Wang Citation2021) and capture the magnitude of contemporary trends to incorporate algorithmic computation into governance. Insofar as the COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated the growing impact of digital technologies in political and social life, how can citizens react to these unprecedented challenges and equip themselves with the best tools? What do residence (algorithmic citizenship), privacy (liquid citizenship), solidarity (metropolitan citizenship), and sovereignty (stateless citizenship) actually mean for citizens amidst a pandemic crisis playing out in a context of algorithmic global disruption? This crisis has clearly accelerated the need to increase human and social understanding of the potential and risks of techno-politics – the entrenchment of digital technologies in political and governmental practices – for pandemic citizens.

Nominally, over the last few decades, globalisation has led to a new class of global citizenship characterised by the widespread notion of world citizens, exemplified by the sense of belonging to everywhere worldwide – without any particular preference of attachment, a rootless global identity. While access to this global citizenship remains uneven, many have enjoyed unlimited freedom to move, work, and travel. However, COVID-19 has drastically slowed the expansion of this global citizenship regime and introduced a ubiquitous new vulnerability in global affairs by giving rise to an ongoing pandemic citizenship regime in which citizens – regardless of their locations – share fears, uncertainties, and risks. Furthermore, COVID-19 is deeply and pervasively related to data and AI governance issues, which expose citizens’ vulnerabilities under potential surveillance states and markets (Morozov Citation2019). Under these extreme circumstances, pandemic citizenship thus can be contextually characterised as follows: The post-COVID-19 era, on the one hand, has dramatically slowed several mundane citizen routines such as mobility patterns, while on the other hand, it has exponentially increased new professional demands, emotional fears, life uncertainties, algorithmic exposure, data privacy concerns, direct health risks, and socio-economic vulnerabilities depending largely on the material and living conditions shared by a wide range of citizens regardless of their specific geolocation worldwide (Newlands et al. Citation2020).

The responses to the pandemic emergency have varied enormously from location to location and, in Europe, even within the same nation-state. The pandemic led many nation-states to lock down, which then boosted online work and the delivery of goods via online platforms, putting further pressure on citizens. However, it also allowed many communities and particularly civic groups and activists in city-regions in Europe to respond resiliently, pushing forward co-operatives and reinforcing social capital (Calzada Citation2020b). Among the resilience strategies adopted by governments in Europe, collective intelligence stemming from proactive citizen responses has been given great consideration as a means to largely forestall further dystopian measures that could exacerbate existing social inequalities and techno-political vulnerabilities among pandemic citizens. A particular collective intelligence response emerging in Europe has been the creation of digital co-operatives, also known as platform co-operatives (Calzada Citation2020b; Scholz Citation2016) and data co-operatives (Calzada Citation2021c; Pentland and Hardjono Citation2020; Scholz and Calzada Citation2021).

This currently emerging pandemic citizenship regime clearly contrasts with the cosmopolitan globalised and borderless citizenship mainstream regime known as world citizens. The later regime has been euphorically and hegemonically spreading over the last decades, producing a new class of global citizens. While access to this global citizenship was still not evenly spread even before the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, many citizens enjoyed the freedom to move, work, and travel with no limits, without borders (Couldry and Mejias Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Gaspar and de Haro Citation2020; Mavelli Citation2018).

The rhetoric of a borderless world under cosmopolitan globalisation has been dramatically invalidated by the COVID-19 crisis, introducing a new level of uncertainty in global affairs and leading many citizens to question whether they will enjoy the freedom of movement once again. Ironically, this circumstance resonates with the popular quote from the former UK primer minister Theresa May: ‘If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere’. Indeed, in the current post-COVID-19 climate in the UK, further exacerbated by post-Brexit nationalist momentum, we must acknowledge that for the moment, this quotation makes total sense.

In this vein, the imposition of radical lockdown measures by many nation-states’ governments and the generalisation of disruptions to borders, complemented by the anxiety produced by the post-Brexit scenario, particularly in the UK and Europe, may well lead us to re-assert that nation-states’ borders will increasingly matter (Welsh Citation2020). However, what is the significance of nation-states and citizenship in this rapidly shifting context given the challenges and limitations of methodological globalisation in state theory (Moisio et al. Citation2020)? Different pandemic adjustments all have different consequences both directly for citizens (depending on which country they call home and their living conditions) and indirectly for nation-states. Therefore, the main hypothesis of this article is that amplified by the generalisable globalised digital citizenship regime of pandemic citizenship, the seeming return of the salience of nation-states’ external borders might affect pandemic citizens directly but not all equally, whereas internal borders might undergo a process of rescaling through a new set of non-generalisable and ongoing emerging digital citizenship regimes. This article illustrates this hypothesis by characterising four non-generalisable and unique techno-politicalised and city-regionalised regimes. In this context, this article argues that the current pandemic crisis is pervasively related to data governance issues that expose pandemic citizens to vulnerability from a potential surveillance state. At this stage, the debate regarding urban liberties, digital rights, and cybercontrol has led some pandemic citizens to consider post-COVID-19 society a society of control, with abundant critique on this topic flourishing from cybernetic and disease surveillance perspectives. Moreover, the flagship Big Tech firms of surveillance capitalism, such as Google and Facebook, have already assumed many functions previously associated with the nation-state, from cartography to citizen surveillance, which has deterritorialised citizenship, that is, made it liquid. Consequently, nation-states are unable to fully interpret the changing regimes and patterns of viralised/hyper-connected citizenship since often within nation-states, urban, and regional governments behave differently by claiming a say in digitally affected socio-economic and socio-political policy matters.

Nation-states’ borders may still matter more than even before – a reality that substantially differs from the portrayals of cosmopolitan global citizenship that have been mainstream among hyperglobalist scholars. These forecast the imminent demise of national state power, and consequently borders because of the purportedly borderless, politically uncontrollable forces of global economic integration (Moisio et al. Citation2020; Ohmae Citation1995). In contrast, a growing literature on state rescaling and associated state spaces and practices provides a strong counterargument: namely, that national states are being qualitatively transformed – not eroded or dismantled – under contemporary capitalist conditions (Brenner Citation2009). Moreover, the current post-COVID-19 crisis is increasingly showing that the more nation-states are reinforced, the more pandemic citizens’ lives seem to be liquified. This means that their uncontrollable algorithmic exposure, which translates to massive digital vulnerability, is being combined with a lack of civil liberties and constant limitations on their freedom of movement (Dumbrava Citation2017). Nation-states, thus, exercise both biopolitical and geopolitical power as modes of social regulation (Moisio et al. Citation2020).

A rescaling of outcomes is actually being provoked by the emergence of new techno-politicised and city-regionalised citizenship regimes: Regarding techno-political dynamics, (i) algorithmic citizenship aims to enable democratic accountability through citizen-centric technologies, even beyond national borders, via, for example, an e-Residence policy framework, and (ii) liquid citizenship aims to assert citizens’ digital rights by protecting users from data extractivism and surveillance by global data-opolistic forces of the Big Tech firms. Regarding city-regional dynamics, (iii) metropolitan citizenship aims to revert the effects of COVID-19, Brexit and post-austerity periods and re-establish social capital among left-behind fractions of communities through resilient responses grounded in Wales’s Foundational Economy, Radical Federalism, and data co-operative strategies (Barbera and Jones Citation2020). Finally, (iv) stateless citizenship involves claiming the right to decide on the present and future relationship with the current state and consequently demanding data sovereignty to manage home rule on data matters (Bauböck Citation2019).

While COVID-19 may be spreading in new ways across space, it is likely that it will stay among us for a long time by scattering long-lasting effects among digital citizens worldwide. Pandemic citizenship will remain as an emerging citizenship regime by both reinforcing the role of nation-states’ external borders while triggering the rescaling of internal governance and further liquifying the daily life of pandemic citizens worldwide (McCosker, Vivienne, and Johns Citation2016). Pandemic citizens are digital citizens on permanent alert, with reduced mobility patterns, hyper-connected 24/7, and affected consciously or unconsciously by a globalised interdependence. Consequently, pandemic citizens are also those directly affected by biometric technologies such as vaccine passports (ALI (Ada Lovelace Institute) Citation2021a) or contact tracing apps and clearly exposed to subtle campaigns designed by several nation-state governments that have been internally reinforcing the importance of keeping national borders closed to protect fellow citizens, implicitly advocating vaccine nationalism, understood as the priority of nationals over anybody else worldwide to secure vaccine access (Bieber Citation2020).

In the context of the globalised pandemic citizenship regime in Europe and in light of the fact nation-states’ territorial coincidence, governing order, economy, citizenship, and identity can no longer be taken for granted (Jessop Citation1990), this section characterises two city-regional and two techno-political dynamics to capture the four emerging techno-politicised and city-regionalised digital citizenship regimes identified in . In doing so, this section conceptualises these regimes in response to four timely drivers of rescaling in Europe (blockchain, dataism, Brexit, and devolution) that stem from two techno-political and two city-regional dynamics occurring in four European nation-states: Estonia, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK). These emerging digital citizenship regimes are presented as specifically politically produced and socially constructed phenomena that also capture matters of global concern. Within the overarching frame of the globalised pandemic citizenship regime, it is precisely this intersection of city-regional realities and European concerns that informs the selection of the regimes. depicts the conceptual digital citizenship taxonomy presented in this article as an overarching, heuristic, and comprehensive assemblage, and framework of the five emerging digital citizenship regimes.

Figure 1. Emerging techno-politicalised and city-regionalised digital citizenship regimes: algorithmic, liquid, metropolitan, and stateless citizenships (Stemming/adapted/extended from and inspired by Calzada Citation2020a).

Algorithmic citizenship: techno-political dynamics in the case of tallinn (Estonia)

Europe increasingly operates online, although geography and physical infrastructure remain crucial to controlling and managing borders through undersea fibre optic cables that trace documented or undocumented citizens. Corresponding to political geography is a reality in which political decisions and national laws transform physical space into virtual territory. This virtual territory represents the arena in which algorithmic e-Residents exist (or simply do not). However, this virtual and analogic merger does not occur automatically and has even less regard for fixed territorial borders. Thus, techno-political infrastructures blend with algorithmic protocols by modifying the established notion of borderless nationhood for their residents, whether intramuros or extramuros.

The contemporary techno-political dynamics of algorithmic citizenship as instantiated in decentralised blockchain ledgers implemented by the small state of Estonia might offer a model for rethinking citizenship in other European city-regions (Tammpuu and Masso Citation2018). Insofar as a pluralist societal pattern has emerged in which groups increasingly claim recognition and demand equal treatment for minorities and voiceless citizens, the regional political agenda could become increasingly Europeanised through multi-level governance schemes. This trend could result in a form of citizenship that can be delinked from territory. Current debates on citizenship, changing geography patterns, political and democratic governance challenges, and more generally the legitimisation of institutional and territorial nation-state power in liberal democracies could be addressed through cutting-edge transitions towards algorithmic discovery embodied in blockchain e-state projects, such as Estonia’s e-Residence policy framework, thereby rescaling the nation-state in the post-COVID-19 digital era (e-Estonia Citation2016).

In 1991, Estonia restored its independence as a small sovereign state, defeating the Soviet Union. In 2000, the government declared Internet access a human right. In 2014, Estonia became the first country to offer electronic residency to people from outside the country, moving towards the idea of a nation-state without borders. e-Estonia refers to a government initiative based on blockchain technology to facilitate citizen interactions with the state through electronic solutions. Estonia has undoubtedly been the leader in the use of blockchain technology for e-identity verification for its citizens as well as for electronic voting systems and digital currency (De Filippi, Reijers, and Reijers Citation2020). Ironically, however, Estonia has one of the largest stateless populations in Europe. Similar to its Baltic neighbours, Estonia has a significant population share that is effectively stateless due to naturalisation laws passed after the fall of the Soviet Union (Bianchini Citation2017; Birnie and Bauböck Citation2020). Indeed, regarding its Russian-speaking minority and the Estonian-speaking majority, Tallinn, portrayed as the leading avant-garde entrepreneurial urban hub, shows that exposure to ethno-linguistically mixed activity is associated with a tendency to have interethnic networks and to visit places outside the city with higher proportions of the other ethno-linguistic group (Silm et al. Citation2021). This raises aspects of inclusivity, digital inequalities, and nation-state rescaling stemming from the interplay between ethno-national/linguistic communities in the core urban area in Tallinn and Estonia’s borderless e-Residency scheme for non-physical-residents. Consequently, although the e-Residency is the national innovation brand and programme of Estonia applying datafied control practices and selections (e-Residency 2.0 Citation2018; Männiste and Masso Citation2020; Tammpuu and Masso Citation2018, Citation2019), it is equally true that this programme could be seen as a phenomenon itself impacting eminently the networking structures of the global urban spaces, making Tallinn a global, pivotal, leading digital hub attracting algorithmic citizens worldwide.

In this context, nation-state rescaling is occurring in Estonia driven by the mechanisms of digital identity and algorithmic coding (ALI, ANI, and OGP Citation2021). Blockchain ledgers are decentralised information architectures that are increasingly used to provide a consensus of replicated, shared, and synchronised digital data geographically spread across multiple sites, states, regions, cities, and institutions (Atzori Citation2017; De Filippi and Lavayssiére Citation2020; Jun Citation2018; Reijers, O’Brolcháin, and Haynes Citation2016). These systems have allowed the establishment of an algorithmic citizenship regime for physical residents and virtual non-residents through a data exchange layer called X-Road, which allows government agencies to gather citizens’ data just once and securely exchange them among agencies instead of requesting them from citizens many times. Tallinn, as the city-regional flagship and leading city in e-government, e-identity, and e-citizenship initiatives, has deployed its e-residency policy framework since December 2014: the first transnational digital identity scheme. This offers non-residents in Estonia, regardless of their citizenship and place of residence, remote access to Estonia’s advanced digital infrastructure for global (now pandemic) digital citizenship e-services via government supported digital identity documents issued in the form of smart identity cards (e-Resident IDs). The aims of this algorithmic citizenship regime were to attract foreign entrepreneurs and investors to Tallinn by giving them remote access to the country’s electronic environment and services, including the possibility of registering a business in Estonia and remotely administering it online. Thus, from the early beginning of this scheme, the objective has been to expand Estonia’s economic base using Tallinn’s leading position as an entrepreneurial urban hub, expanding the opportunities available to the country’s limited population of only 1.3 million inhabitants woldwide.

According to Tammpuu and Masso (Citation2018, Citation2019), although the non-residents attracted by the e-Residence policy scheme are primarily entrepreneurs from digitally advanced countries outside the EU who do not have EU citizenship, this policy scheme may also appeal to e-Residents from countries with lower levels of e-government development. This aspect seems particularly pertinent for citizens and entrepreneurs from non-EU countries and likewise for British citizens who may have lost their status as EU citizens as a result of Brexit. It remains to be seen whether this leading country in digital transformations can spur an inclusive algorithmic citizens regime or by contrast falls into the same scenario of citizenship revocations and naturalisation-driven divisions that ended in Brexit (Welsh Citation2020). Another pending question is whether this emerging regime of algorithmic citizenship can change traditional notions of residency based on fixed geographical location to ultimately alter the notions of (im)migration and citizenship by opening the way to universal and inclusive digitally enabled de-territorial and transnational citizenship. In light of the potential emerging practices of algorithmic citizenship, Tammppu and Masso wisely question ‘whether or not technological innovations such as e-Residency will benefit those who could benefit most from such re-engineered systems of citizenship or merely augment the agency of those who are already (digitally) more privileged’ (Tammpuu and Masso Citation2019, 624). Tammpuu and Masso reveal that the e-Residency programme tends to further increase the digital opportunities of citizens and entrepreneurs who are digitally better positioned by their own national governments.

Algorithmic citizenship may therefore pose a paradox in post-COVID-19 times: While Tallinn is vaunted as a leading avant-garde entrepreneurial flagship urban area, it may also reproduce transnational digital inequalities in the long run, in addition to the fact that the existence of the Russian-speaking stateless population may present particular burdens amidst the pandemic disruption. Nonetheless, the dynamism of Tallinn, together with Estonia’s small size, may help the country face the COVID-19 crisis due to higher social cohesion, more flexible crisis management, and easier tracking of infection with the sophisticated digital infrastructure stemming from, among others, its e-identity and e-Residency schemes.

This regime of algorithmic citizenship bears out that state rescaling could still involve a role for the nation-state as a necessary central point of coordination, showing that decentralised architecture through blockchain and algorithm-based consensus is still an organisational theory – with not a few internal contradictions – not a stand-alone political theory (Atzori Citation2017). However, allowing non-physical residents outside external borders to become e-Residents while a non-naturalised stateless population remains inside internal borders leads to significant and unresolved techno-political dilemmas for even digitally advanced urban areas such as Tallinn and, as a consequence, for the rescaling of the Estonian nation-state. Given the intertwined relationship between the state-driven algorithmic citizenship essentially as an enabler, as seen in Tallinn, and the Big Tech firms-driven liquid citizenship as a constraint (as it will be shown in the next section with Amsterdam and Barcelona), this article argues that the techno-political domain is still at stake.

Liquid Citizenship: Techno-Political Dynamics in the Cases of Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain) and Amsterdam (Netherlands)

Digital philosopher Evgeny Morozov (Morozov Citation2019) has argued that the economics of data extraction by Big Tech firms has enabled the emergence of a new global protectionist geopolitical order called AI nationalism, which contrasts with citizens’ needs and claims of digital rights. According to billionaire investor and social philanthropist George Soros, these giant platforms have become obstacles to innovation and menaces to citizenship.

As Bauman (Bauman Citation2000) suggested, hitherto seemingly solid European nation-states have been abruptly liquefying in the face of algorithmic disruption and data-opolies. The giant technological flagship firms of surveillance capitalism, such as Google and Facebook, have already assumed many functions previously associated with the nation-state, from cartography to the surveillance of citizens, which has deterritorialised citizenship to produce liquid citizenship. While liquid citizens remain highly distributed across a global grid of networks, the data that they produce are concentrated in the hands of a few companies through the implementation of dataism: an emerging ideology in which citizens are dispossessed of their data and digital rights.

Recently, a range of literature about digital rights has appeared from different disciplinary perspectives (Karppinen and Puukko Citation2020; Pangrazio and Sefton-Green Citation2021) alongside a large corpus of high-profile reports, institutional declarations from different supranational, national, regional, and global contexts and empirical datasets such as atlases and rankings. On the one hand, for several authors, algorithmic disruption has raised the question of how liquid citizenship can be defined through the incorporation of new digital rights related to the status of a citizen in cyberspace – namely access, openness, net neutrality, digital privacy, and data encryption, protection, control, and sovereignty. On the other hand, the authors of recent declarations include not only civil society organisations but also various coalitions of states, international organisations, and industry actors – framing digital rights in terms of corporate social responsibility – as well as city coalitions such as the one used to illustrate liquid citizenship in this sub-section: The Cities’ Coalition for Digital Rights (CCDR) (Calzada, Pérez-Batlle, and Batlle-Montserrat Citation2021).

In the aftermath of the GDPR, Amsterdam and Barcelona in Europe – alongside New York in the US – counter-reacted against dataism by launching the CCDR, a joint initiative to claim, promote, and track progress in protecting citizens’ digital rights to revert the extractivism of data-opolies. CCDR reflects a joint city-network policy reaction through an inter-urban digital rights advocacy by struggling against the (globalised) pandemic citizenship regime (Calzada Citation2021d). As such, a direct outcome of this policy advocacy was the Declaration of the Cities’ Coalition for Digital Rights (CCDR (Cities’ Coalition for Digital Rights) Citation2019), which was translated into data policy by through the building of networked data infrastructures and institutions along with the provision of policy recommendations (Calzada and Almirall Citation2020). Under the leadership of Barcelona and Amsterdam, this movement has been expanding worldwide, reaching an additional 46 cities – including Athens, Balikesir, Berlin, Bordeaux, Bratislava, Cluj-Napoca, Dublin, Glasgow, Grenoble, Helsinki, La Coruña, Leeds, Leipzig, Liverpool, London, Lyon, Milan, Moscow, Munich, Nice, Porto, Rennes Metropole, Rome, Stockholm, Tirana, Turin, Utrecht, Vienna, and Zaragoza in Europe; Amman in the Middle East; Atlanta, Austin, Cary, Chicago, Guadalajara, Kansas City, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Montreal, Philadelphia, Portland, San Antonio, San José, Sao Paulo, and Toronto in the Americas; and Sydney in Australia.

During the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, Amsterdam and Barcelona conducted resilience actions including, respectively, (i) mapping public safety risks in supply chains, gathering data to measure the impact of the outbreak on mobility, and researching how tech could ease the lockdown process (‘Unlock Amsterdam’) and (ii) extending Telecare, which had almost 90,000 users; the Radars programme (1,600 users), which monitors people living alone with the collaboration of the neighbourhood network; and the VinclesBCN App service (2,400 users), which monitors elderly people (through health channels).

In recent years, European cities and regional authorities have claimed, in directly bypassing nation-states’ central authorities, that (smart) citizens are as important to a successful smart city programme as the underlying data and technology and that these citizens must be convinced of the benefits and security that such initiatives offer (Calzada Citation2018b). Cities such as Barcelona and Amsterdam are leading a new digital transformation agenda that complements the EU’s GDPR, which mandates the ethical use of data to protect (smart) citizens from risks inherent in new, data-intensive technologies. Several authors have traced the contours of the liquid citizenship debate. They have explored the problem of how city and regional authorities can proactively establish policies, strategies, and initiatives to locally enhance digital rights and give citizens more control over personal data by protecting them from discrimination, exclusion, and the erosion of their data privacy and ownership (Park and Humphry Citation2019).

In the European data-driven economy, AI, big data, machine learning, and blockchain technologies are reshaping the notion of citizenship in Europe by, on the one hand, pervasively challenging nation-states’ fixed dynamics through rescaling and, on the other hand, triggering a counter-reaction by city-regions seeking to give citizens control over their data. Claims of technological sovereignty through data commons policy programmes and the Decode EU experimental project currently taking place in Barcelona and Amsterdam are presented as the flagship initiatives of this movement, which has already been replicated throughout other European city-regions. In the post-GDPR scenario, (smart) liquid citizens’ data privacy, security, and ownership ultimately need to be protected through the localisation of personal data via grassroots innovation and platform and data co-operatives (Calzada Citation2020b). Nevertheless, recent research also reveals that while data protection impacts smart city development, liquid citizens’ meaningful influence remains very limited insofar as already dominant actors and decision-makers remain in control of urban developments while citizens often lack awareness and data literacy. Consequently, digital rights advocacy has occurred in cities like Barcelona and Amsterdam, which implemented an active intermediation agency with participatory methods to ameliorate representation deficits (Calzada Citation2020c). How this type of liquid citizenship will be influenced and shaped by the geopolitical dynamics between city-regions, nation-states, and Big Tech firms is still unfolding (Ernst Citation2021).

Metropolitan Citizenship: City-regional Dynamics in the Case of Cardiff (Wales, UK)

In the European context, metropolitan citizenship is a two-sided coin that involves blurred meanings and ambiguous political interests (Moore-Cherry, Pike, and Tomaney Citation2021). Europe, now split into the EU and the UK separately, is a continent with intensifying incompatibilities in the legacies of its nation-states, and demands for transnational governance are escalating, with potentially widespread consequences in terms of social and political conflicts – not only between nation-states but also (and most likely) across nation-states through city-regions.

In the UK in particular, the outcome of Brexit was fuelled by a growing sense of disempowerment and alienation among those not part of the system, those living in ‘places that do not matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018, 189). Therefore, city-regional spaces beyond nation-states are seen as constitutive fields of tensions between different spatial policy representations, discourses, and practices, embodied by different rationales for action and with potentially different scalar effects (de Koning, Jaffe, and Koster Citation2015). Paralleling the pervasive side effects for metropolitan and non-metropolitan citizens, nation-states are being rapidly rescaled through a metropolitanisation trend (Katz and Bradley Citation2013). As demonstrated in Wales, this trend can be defined by the distinction between a more visible, articulate, progressive, and metropolitan class (Wyn Jones and Larner Citation2020) and those in the more peripheral, less articulate, conservative, non-metropolitan (rural), and often less-developed areas.

Brexit revealed deep divides within the UK, such as that between the metropolitan citizenry and the rest, to be simmering under the surface of the discursive homogeneity characteristic of democratic representation in nation-states (Welsh Citation2020). These divides not only derive from the unevenness in perceived opportunities and stakes in political decisions about state development but also shape those very divisions and borders. Such city-regional dynamics may lead to perceived underrepresentation or even voicelessness of non-metropolitan citizens (Mulligan Citation2013). Regarding this metropolitan divide, to an extent, the Brexit referendum in Wales clarified that the most potent divisions are between the so-called metropolitan pro-EU and the more peripheral (provincial), anti-EU, rural rest – that is, residents of places that do not matter. This has produced new socio-political cleavages between the often highly educated and mobile citizens who can benefit from globalisation and those left behind, who are dependent on weakened national welfare states or European structural funds and show a strong English nationalistic approach (Henderson and Jones Citation2021).

In Wales, 52.53% voted to leave the EU (854,572 votes; NAW Citation2016; WG Citation2021). In a closer examination, as Professor Danny Dorling has demonstrated, the pro-Brexit majority came not from those not identifying as Welsh but from English migrants who settled in non-metropolitan areas in recent decades. Metropolitan Cardiff had the highest Remain vote, with 60%, alongside the pro-EU Welsh nationalist and Welsh-speaking Plaid Cymru stronghold areas – Ceredigion, Gwynedd, Monmouthshire, and the Vale of Glamorgan – while non-metropolitan and border towns and areas of central Wales popular with English settlers and retired people who moved to Wales for its lower property prices saw a large proportion of Leave votes. Dorling estimates that 650,000 votes out of 854,572 total Leave votes might correspond to English-born people living in non-metropolitan Wales at the time of the referendum. The results caught many by surprise due to the high number of Leave votes; e.g. the valleys in the South Wales voted Leave (which garnered a vote share of approximately 60%) despite benefitting the most from EU structural funds among all nations in the UK.

Against this unexpected post-Brexit Welsh backdrop, Raymond Williams, in his writings in Who Speaks for Wales? (Williams Citation2021), anticipated the likely early consequences of political devolution (Wyn Jones and Larner Citation2020) and offered a robust narrative for progressivist metropolitan citizenship based on a Welsh-European vision of a Europe of the peoples and nations. Unexpectedly, however, Brexit has been accompanied by an increase in support for devolution and even independence among those self-identified as Welsh only. Therefore, the early call to action suggested in early days by Williams may well resonate these days with several initiatives and projects stemming from the re-elected Welsh government’s progressive agenda reinforcing home rule known as Radical Federalism (RF (Radical Federalism) Citation2021) as well as from an awakening of the civil society through a new socio-economic paradigm called ‘Foundational Economy’ (Barbera and Jones Citation2020; FEC Citation2020; FE (Foundational Economy) Citation2020): this paradigm encompasses those goods and services – together with the economic and social relationships that underpin them – that provide the everyday infrastructure of civilised life.

The Foundational Economy paradigm, as a socio-economic reaction, reform, and resiliency response taking its lead from Cardiff, could be a driver for nation-state rescaling insofar as it is deeply altering the policy context since the elections in May 2021 by establishing Radical Federalism (RF (Radical Federalism) Citation2021; YesCymru Citation2021), which aims to empower city-regional communities by pushing ahead a metropolitan citizenship agenda from Cardiff as a counter-reaction to the side effects of Brexit and COVID-19. This city-regional dynamic might nurture metropolitan citizenship through the creation of platform and data co-operatives (Calzada Citation2020b; Scholz and Calzada Citation2021) as a way to establish city-regional data ecosystems grounded at the regional level and foster rescaling through an intensive digital policy agenda empowering local communities through data donation and altruism (WG (Welsh Government) Citation2021; CU Citation2018).

Pandemic times have been a turning point for city-regional transformation and community awakening, offering an opportunity for experimentation with data co-operatives, working towards more responsive systems of care, adequate medical services, and a fairer, more participatory data economy. Data co-operatives from Cardiff and beyond within Wales must be shaped by those who need them most, grounded in the history and practices of local communities (Calzada Citation2021c). Foundational Economy has set the scene to re-empower communities in the spirit of metropolitan citizenship and solidarity. We have already witnessed the creation of some initiatives – Wales Co-operative Centre, Bank Cambria, IndyCube, CelynCymru, DriveTaxis, and Open Food Network – pushing the Radical Federalism agenda, which may reinvigorate the whole city-regional dynamic in rescaling the nation-state by emphasising a counter-power from the urban core in Cardiff and offering a joint, resilient policy reaction in the aftermath of Brexit and the COVID-19 crisis.

Stateless Citizenship: City-Regional Dynamics in the Cases of Glasgow (Scotland, UK), Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain) and Bilbao (Basque Country, Spain)

Stateless citizenship is frequently, but not always, fuelled by civic nationalism rooted in the metropolitan right to decide (as an updated version of the right-to-the-city principle) and bolstered by metropolitan hubs through an increasing push by grassroots movements (Calzada Citation2018c). Studies of stateless citizenship have been primarily carried out in Europe in three small, stateless, city-regionalised nation settings – Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Scotland – by paying special attention to their metropolitan hubs: Barcelona, Bilbao, and Glasgow (Keating Citation2013). Self-rule accommodation regimes provided by nation-states to city-regions continue to be perceived as insufficient by stateless civic nationalist movements and political representatives from the aforementioned city-regions, resulting in further tensions in relation to territorial statehood, spaces of historical identity, and future secessionist aspirations, and demands for claiming for devolution of powers to diverse degrees (Elias et al. Citation2021; Mulle and Serrano Citation2018; Calzada Citation2019). One means by which nation-states can address this tension is to seek outright independence to reconcile small city-regionalised nations’ spaces of identity and statehood through referenda, as occurred in Scotland in 2014. Nevertheless, Cetrà and Harvey (Citation2018, 1) predict that ‘independence referendums will continue to be rare events’.

On 1 October 2017, 2,286,217 Catalan citizens attempted to exercise the right to decide in an illegal and constitutive referendum that took place in Catalonia, to ultimately become stateless citizens (Calzada Citation2019). Unlike Catalonia – whose attempted referendum inspired a strong will to imitation among a considerable part of the Basque society – Scotland held a peaceful and bilaterally agreed referendum in 2014, resulting in a slight majority in favour of preserving the union. Nonetheless, even considering the outstanding regular performance of the SNP in the last Scottish elections on 6 May 2021, driven by its commitment to hold a second independence referendum once a large parliamentary majority has been secured with the Scottish Greens, it remains to be seen whether the right to decide could be ensured through a second referendum given the current hard-line refusal of the British prime minister to contemplate such a move, which might provoke the break-up of the UK, representing the most severe degree of nation-state rescaling considered in this article.

The right to decide on independence might be relatively in tune with the data sovereignty (Calzada Citation2021c; Kukutai and Taylor Citation2016), although some academic interpretations might limit the latter phenomenon related to self-determination to post-colonial cases by overlooking the historic path dependency of stateless nations and their current will to empower their stateless citizens and communities through data sovereignty. Data sovereignty in this context could be defined as bringing data flows under the control not only of nation-states’ jurisdiction but also that of indigenous communities and stateless nations (Hummel et al. Citation2021).

COVID-19 may have amplified the extent to which AI and digital transformations exacerbate existing social, economic, political, and geographic inequalities even within the same nation-state, affecting the most vulnerable segments of society in particular without providing the appropriate digital tools to empower the elderly people, youth, and citizens from socially and economically disadvantaged groups in stateless city-regionalised nations and their main urban areas, in this case Barcelona in Catalonia, Glasgow in Scotland, and Bilbao in the Basque Country. The context regarding data sovereignty in each of these urban areas is summarised as follows:

Barcelona has been focusing on digital inclusion, open technologies, and accountable decision-making in AI as its main priorities in implementing data sovereignty. This urban area is primarily emphasising existing projects in civil society and at universities. A specific contextual aspect that has underscored the relevance of data sovereignty in Barcelona is its strong civil society alongside the fact that it has assumed the lead in the paradigm of technological humanism through the Mobile World Congress. The most critical stakeholder group seeking more protection for data sovereignty is private companies, especially those providing public services. However, without the engagement of civil society, it is rather difficult to achieve an inclusive data-governance model (Dencik et al. Citation2019). Certain entrepreneurs, activists, and innovators are pushing Barcelona’s data sovereignty ecosystem forward. In post-COVID-19 Barcelona, digital inclusion and data sovereignty go hand in hand in a data commons strategy based on transparency, accountability, literacy, and the data sovereignty of citizens. At present, in search of a new equilibrium after times of conflict, the municipality and the regional government are coordinating a data sovereignty strategy with reference to AI and thereby rescaling the relationship with the nation-state towards further agreed – and most importantly realistic – devolved scenarios.

Glasgow has focused on digital inclusion and skills by establishing a data sovereignty strategy and engaging with elected officials to raise their awareness. The local authority has been actively implementing measures to achieve universal and equal Internet access and digital literacy. The aftermath of COVID-19 has seen much greater data sharing within the city and with national public bodies, which in itself may reinforce the idea that sooner or later, data sovereignty will be claimed at the national level in Scotland, although citizen-driven data initiatives still might lack consistency and leadership. Regarding AI implementation in the public sector, a lack of public trust is seen as the main obstacle. However, on the positive side, AI adoption is consequently being coordinated by the Scottish government through its data sovereignty-driven AI strategy, in which Glasgow has an active role, essentially showing what this article is attempting to depict: an inter-dependent, joint effort between Glasgow and Scotland. In this context, for the adoption of AI in the public sector from Glasgow and its extension throughout Scotland, it may be necessary to further devolve powers related to data sovereignty – which, in light of the potential for a second independence referendum, may be rather feasible.

Bilbao is making an effort to establish itself as a leading city in Industry 4.0 and advanced manufacturing. Therefore, data sovereignty in Bilbao and the Basque Country seems to be key to responding to the challenges exposed by digital European recovery funds insofar as it will allow the articulation of this industrial strategy by fostering new economic activity. The project AsFabrik, which is located in the heart of the city, attempts to shed light on advanced services for the digital transformation of the industry that inevitably will affect the consideration of citizen data sovereignty at not only the city level but also at the regional level. Data sovereignty in relation to AI and digital inclusion is being nurtured by several universities, including Deusto and Mondragon, through multi-stakeholder-driven initiatives at the city-regional level. The new initiative entitled https://euskalherriadigitala.eus/ advocating with a manifesto the need for technological sovereignty and stemming from a group of co-operatives, might well notice as an initial evidence of this preliminary socio-political claim for the right to decide on devolution of digital powers and data sovereignty (in education, industry, employment, robotics, automatization, digital humanities, and democracy). The Basque Country, encompassing and connecting three administrative entities’ multi-level governance policy inventories, will probably evolve towards greater devolution through an algorithm-driven digital internal architecture based on blockchain called algorithmic nation (Calzada Citation2018a) by further emulating what Estonia is implementing but with an internal dimension rather than an external e-Residency dimension.

Concluding remarks

Despite the literature on the role of the nation-state in urban development placing great significance on territory as a political technology of governance in the contemporary urbanised world, conceptual taxonomies and empirical evidence on digital citizenship remain scarce and inconclusive with regard to how different emerging citizenship regimes can affect the nation-state rescaling phenomena (Mossberger, Tolbert, and McNeal Citation2007). This trend poses ontological and methodological globalism-related challenges for contemporary political geography, critical data science, digital studies, social innovation, and regional studies. Methodological globalism is ‘a tendency for social scientists to prioritize the analysis of globalization processes over and above knowledge of the variety of socio-spatial structures, processes, and practices that shape state forms and functions at various territorial scales’ (Moisio et al. Citation2020, 14). This article revolved in particular around citizenship and state-geographies nexus that need further consideration and analysis related to the five emerging digital citizenship regimes presented so far: (i) indigenous geographies and digital rights, (ii) datafication and digitalisation, (iii) state-citizens relationship, and (iv) even thinking beyond the state (Moisio et al. Citation2020, 17–21), operationalising the cutting-edge term algorithmic nation (Calzada Citation2018a).

The aim of this article has been to suggest that citizenship regimes are emerging, at least in Europe, while assuming that the political authority of the nation-state is being transformed in this process – not eroded or dismantled (and not necessarily as a consequence of these emerging regimes) – through the triggering of wider debates regarding the spatial organisation and legitimation of nation-state power, institutionally and territorially as well as politically and democratically. To offer a reinterpretation and a new perspective on these intertwined phenomena of rescaling, the article has extended a conceptual taxonomy to interpret these alterations by describing one globalised and generalisable biopolitical dynamic as well as two city-regional and two techno-political non-generalisable dynamics, each fuelled by a specific driver of rescaling: COVID-19, blockchain, dataism, Brexit, and devolution. The article has focused on a new pandemic citizenship regime emerging alongside four already-existing regimes in the context of several European city-region-specific case studies: algorithmic (Tallinn), liquid (Barcelona and Amsterdam), metropolitan (Cardiff), and stateless (Glasgow, Barcelona, and Bilbao) citizenship.

The limitations of the current study relate mainly to the selection of case studies. As expressed throughout the article, except for the generalisable and globalised digital citizenship regime of pandemic citizenship – which is obviously a generic category – the selection of the rest of the cases responds to the fact that they offer sufficient evidence to consider the existence of an ongoing debate on state rescaling through either techno-political or city-regional territorialised dynamics. More cases could be probably considered for each regime or even further regimes could be identified and examined. This article aimed to better elucidate how post-COVID-19 datafication processes have amplified the emergence of interrelated, non-mutually exclusive, and non-generalisable digital citizenship regimes in certain European nation-states’ urban areas. Therefore, the examination of these current trends does not offer generalisable results but instead provides a potential path to follow in extending this taxonomy. Despite these limitations, this taxonomy encourages future research that not only (i) uses a similar approach to identify other regimes and broaden the taxonomy but also (ii) adds new cases to the existing regimes and (iii) deepens the analysis of the presented cases.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Igor Calzada

Dr Igor Calzada, MBA, FeRSA (www.igorcalzada.com/about) is a Senior Researcher working in smart city citizenship, benchmarking city-regions, digital rights, data co-operatives, and digital citizenship; since 2021 at WISERD (Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research and Data), Civil Society Research Centre ESRC, Cardiff University and since 2012 at the Future of Cities and Urban Transformations ESRC Programme, University of Oxford funded by EC-H2020-Smart Cities and Communities and EC-Marie Curie-CoFund-Regional Programmes. Additionally, he serves as Senior Advisor to UN-Habitat in Digital Transformations for Urban Areas, People-Centered Smart Cities. Previously, he worked at the DG Joint Research Centre, European Commission as Senior Scientist in Digital Transformations and AI. He has more than 20 years of research/policy experience as Senior Lecturer/Researcher in several universities worldwide and in public and private sector as director. Publications: 51 journal articles; 11 books; 18 book chapters; 27 policy reports; 147 international keynotes; and 32 media articles.

Notes

1. Because of length constraints, at the end of section 2, includes references detailed in and throughout the article.

References

- Agnew, J. 2017. “The Tragedy of the Nation-state.” Territory, Politics, Governance 5 (4): 347–350. doi:10.1080/21622671.2017.1357257.

- Aho, B., and R. Duffield. 2020. “Beyond Surveillance Capitalism: Privacy, Regulation and Big Data in Europe and China.” Economy and Society 49 (2): 187–212. doi:10.1080/03085147.2019.1690275.

- Al-Saqaf, W., and N. Seidler. 2017. “Blockchain Technology for Social Impact: Opportunities and Challenges Ahead.” Journal of Cyber Policy 2 (3): 338–354. doi:10.1080/23738871.2017.1400084.

- ALI (Ada Lovelace Institute), ANI (AI Now Institute), and OGP (Open Government Partnership. 2021. Algorithmic Accountability for Public Sector: Learning from the First Wave of Policy Implementation. Accessed 3 December 2021. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/documents/algorithmic-accountability-public-sector/

- ALI (Ada Lovelace Institute). 2021a. Checkpoints for Vaccine Passports: Requirements for Governments and Developers. London: Ada Lovelace Institute.

- ALI (Ada Lovelace Institute). 2021b. What Place Should COVID-19 Vaccines Passports Have in Society? London: Ada Lovelace Institute.

- Ammann, O. 2020. “Passports for Sale: How (Un)meritocratic are Citizenship by Investment Programmes?” European Journal of Migration and Law 22 (3): 309–337. doi:10.1163/15718166-12340078.

- Arendt, H. 1949. “The Rights of Man: What are They?” Modern Review 3 (26): 4–37.

- Arrighi, J.-T., and D. Stjepanović. 2019. “Introduction: The Rescaling of Territory and Citizenship in Europe.” Ethnopolitics 1–8. doi:10.1080/17449057.2019.1585087.

- Atzori, M. 2017. “Blockchain Technology and Decentralized Governance: Is the State Still Necessary?” Journal of Governance and Regulation 6 (1): 45–62. doi:10.22495/jgr_v6_i1_p5.

- Barbera, F., and I.-R. Jones. 2020. The Foundational Economy and Citizenship: Comparative Perspectives on Civil Repair. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Bauböck, R. 2019. “A Multilevel Theory of Democratic Secession.” Ethnopolitics 18 (3): 227–246. doi:10.1080/17449057.2019.1585088.

- Bauman, Z. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bianchini, S. 2017. Liquid Nationalism and State Partitions in Europe. Chentelham: Edward Elgar.

- Bieber, F. 2020. “Global Nationalism in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nationalities Paper 1–13. Accessed 3 December 2021. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/nationalities-papers/article/global-nationalism-in-times-of-the-covid19-pandemic/3A7F44AFDD6AC117AE05160F95738ED4

- Bigo, D., E. Isin, and E. Ruppert. 2019. Data Politics. London: Routledge.

- Birnie, R., and R. Bauböck. 2020. “Introduction: Expulsion and Citizenship in the 21st Century.” Citizenship Studies 24 (3): 265–276. doi:10.1080/13621025.2020.1733260.

- Brenner, N. 2009. “Open Questions on State Rescaling.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2 (1): 123–139. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsp002.

- Breuer, J., and J. Pierson. 2021. “The Right to the City and Data Protection for Developing Citizen-centric Digital Cities.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (6): 797–812. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2021.1909095.

- Bridle, J. 2016. “Algorithmic Citizenship, Digital Statelessness.” GeoHumanities 2 (2): 377–381. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2016.1237858.

- Brown, S., J. Davidovic, and A. Hasan. 2021. “The Algorithm Audit: Scoring the Algorithms that Score Us.” Big Data & Society 8 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1177/2053951720983865.

- Burki, T. 2021. “Equitable Distribution of COVID-19 Vaccines.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 21 (1): 33–34. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30949-X.

- Calzada, I., and E. Almirall. 2020. “Data Ecosystems for Protecting European Citizens’ Digital Rights.” Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 14 (2): 133–147. doi:10.1108/TG-03-2020-0047.

- Calzada, I., M. Pérez-Batlle, and J. Batlle-Montserrat. 2021. “People-centered Smart Cities: An Exploratory Action Research on the Cities’ Coalition for Digital Rights.” Journal of Urban Affairs 1–26. doi:10.1080/07352166.2021.1994861.

- Calzada, I. 2015. “Benchmarking Future City-regions beyond Nation-states.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2 (1): 351–362. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1046908.

- Calzada, I. 2018a. “‘Algorithmic Nations’: Seeing like a City-regional and Techno-political Conceptual Assemblage.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 5 (1): 267–289. doi:10.1080/21681376.2018.1507754.

- Calzada, I. 2018b. “(Smart) Citizens from Data Providers to Decision-makers? the Case Study of Barcelona.” Sustainability 10 (9): 3252. doi:10.3390/su10093252.

- Calzada, I. 2018c. “Metropolitanising Small European Stateless City-regionalised Nations.” Space and Polity 22 (3): 342–361. doi:10.1080/13562576.2018.1555958.

- Calzada, I. 2019. “Catalonia Rescaling Spain: Is It Feasible to Accommodate Its “Stateless Citizenship”?” Regional Science Policy & Practice 11 (5): 805–820. doi:10.1111/rsp3.12240.

- Calzada, I. 2020b. “Platform and Data Co-operatives Amidst European Pandemic Citizenship.” Sustainability 12 (20): 8309. doi:10.3390/su12208309.

- Calzada, I. 2020c. “Democratising Smart Cities? Penta-Helix Multistakeholder Social Innovation Framework.” Smart Cities 3 (4): 1145–1172. doi:10.3390/smartcities3040057.

- Calzada, I. 2021a. Smart City Citizenship. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Elsevier Science Publishing Co .

- Calzada, I. 2021b. Pandemic Citizenship Amidst Stateless Algorithmic Nations: Digital Rights and Technological Sovereignty at Stake. Brussels: Coppieters Foundation. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.36196.19849/3.

- Calzada, I. 2021c. “Data Co-operatives through Data Sovereignty.” Smart Cities 4 (3): 1158–1172. doi:10.3390/smartcities4030062. Special Issue ‘ Feature Papers for Smart Cities.’

- Calzada, I. 2021d. “The Right to Have Digital Rights in Smart Cities.” Sustainability 13 (20): 11438. doi:10.3390/su132011438. Special Issue ‘ Social Innovation in Sustainable Urban Development.’

- Calzada, I. 2020a. “Emerging Citizenship Regimes and Rescaling (European) Nation-States: Algorithmic, Liquid, Metropolitan and Stateless Citizenship Ideal Types.” In Handbook on the Changing Geographies of the State: New Spaces of Geopolitics, edited by S. Moisio, N. Koch, A. E. G. Jonas, C. Lizotte, and J. Luukkonen, 368–383. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781788978057.00048.

- CCDR (Cities’ Coalition for Digital Rights). 2019. “Declaration of Cities Coalition for Digital Rights.” https://citiesfordigitalrights.org/

- Cetrà, D., and M. Harvey. 2018. “Explaining Accommodation and Resistance to Demands for Independence Referendums in the UK and Spain.” Nations and Nationalism. doi:10.1111/nana.12417.

- Cheney-Lippold, J. 2011. “A New Algorithmic Identity: Soft Biopolitics and the Modulation of Control.” Theory, Culture & Society 28 (6): 164–181. doi:10.1177/0263276411424420.

- Cheney-Lippold, J. 2017. We are Data: Algorithms and the Making of Our Digital Selves. New York: New York University Press.

- Chouliaraki, L., and M. Georgiou. 2022. The Digital Border: Migration, Technology, Power. NYC: NYU Press.

- Couldry, N., and U. A. Mejias. 2019a. The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Couldry, N., and U. A. Mejias. 2019b. “Making Data Colonialism Liveable: How Might Data’s Social Order Be Regulated?” Internet Policy Review 8 (2). doi:10.14763/2019.2.1411.

- Csernatoni, R. 2020. “New States of Emergency: Normalizing Techno-surveillance in the Time of COVID-19.” Global Affairs 1–10. doi:10.1080/23340460.2020.1825108.

- CU (Cardiff University). 2018. Digital Technologies and Future Opportunities for the Foundational Economy in Wales. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

- Daskal, E. 2018. “Let’s Be Careful Out There …: How Digital Rights Advocates Educate Citizens in the Digital Age.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (2): 241–256. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1271903.

- De Filippi, M. M., W. Reijers, and W. Reijers. 2020. “Blockchain as a Confidence Machine: The Problme of Trust & Challenge of Governance.” Technology in Society 62 (101284): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101284.

- De Filippi, P., and X. Lavayssiére. 2020. Blockchain Technology: Toward a Decentralized Governance of Digital Platforms? the Great Awakening: New Modes of Life Amidst Capitalist Ruins. Goleta: Punctum Book.

- de Koning, A., R. Jaffe, and M. Koster. 2015. “Citizenship Agendas in and beyond the Nation-state: (En)countering Framings of the Good Citizen.” Citizenship Studies 19 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1080/13621025.2015.1005940.

- Dencik, L., J. Redden, A. Hintz, and H. Warne. 2019. “The Golden View: Data-driven Governance in the Scoring Society.” Internet Policy Review 8 (2): 2. doi:10.14763/2019.2.1413.

- Desforges, L., R. Jones, and M. Woods. 2005. “New Geographies of Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 9 (5): 439–451. doi:10.1080/13621020500301213.

- Dijstelbloem, H., and D. Broeders. 2015. “Border Surveillance, Mobility Management and the Shaping of Non-publics in Europe.” European Journal of Social Theory 18 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1177/1368431014534353.

- Dumbrava, C. 2017. “Citizenship and Technology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, edited by A. Shachar, R. Bauböck, I. Bloemraad, and M. Vink, 767–788. Oxford: OUP.

- Dyer-Witheford, N., M. Kjosen, and J. Steinhoff. 2019. Inhuman Power Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Capitalism. London: Pluto Press.

- e-Estonia. 2016. “Country as a Service: Estonia’s New Model.” https://e-Estonia.com/country-as-a-service-estonias-new-model/

- e-Residency 2.0. 2018. White Paper. Recommendations for Marking Estonia’s Ground-breaking e-Residency Initiative More Beneficial to Everyone Who Is Part of Our Digital Nation. Tallinn: e-Residency 2.0.

- Elias, A., L. Basile, N. Franco-Guillén, and E. Szocsik. 2021. “The Framing Territorial Demands (Fraterr) Dataset: A Novel Approach to Conceptualizing and Measuring Regionalist Actors’ Territorial Strategies.” Regional & Federal Studies 1–16. doi:10.1080/13597566.2021.1964481.

- Ernst, D. Supply Chain Regulation in the Service of Geopolitics: What Is Happening in Semiconductors? CIGI Papers No. 256 – August 2021. Centre for International Governance Innovation.

- FE (Foundational Economy). 2020. “2020 Manifesto for the Foundational Economy.” https://foundationaleconomy.com

- FEC (Foundational Economy Collective). 2020. What Comes after the Pandemic? A Ten-Point Platform for Foundational Renewal. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

- Floridi, L. 2020. “The Fight for Digital Sovereignty: What It Is, and Why It Matters, Especially for the EU.” Philosophy & Technology 33 (3): 369–378. doi:10.1007/s13347-020-00423-6.

- Foucault, M. 2003. ‘Society Must Be Defended’: Lectures at the College de France, 1975-76. New York: Picador.