Abstract

Objectives

The Contraceptive Counselling (COCO) study tested whether a structured approach to assessing patient needs and expectations improved method choice and satisfaction with the contraceptive decision-making process.

Methods

Physicians and women were invited to complete needs-based contraceptive counselling sessions using a structured questionnaire. Physicians recorded the individual responses online; women evaluated the process using an immediate post-consultation questionnaire and then via a structured online interview 6 months later.

Results

A total of 92 gynaecologists and 1176 women participated: 951 women completed the immediate post-consultation survey and 145 took part in the 6 month online evaluation. There was a substantial increase in satisfaction with the current contraceptive method: the number of women reporting they were ‘very satisfied’ with their contraceptive method increased by 30%. This applied to starters and switchers as well as to women continuing with their previous method. Women were highly satisfied with the structured approach; 95% rated the counselling as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ and ‘comprehensive and detailed’.

Conclusion

Using a structured approach to share information tailored to women’s needs can help them choose from a broader range of methods and, in some cases, change to a method more suitable to their individual needs, and ultimately increase satisfaction with their choice.

摘要

目的:避孕咨询(COCO)研究测试了评估患者需求和期望的结构化方法是否改善了方法选择和避孕决策过程的满意度。

方法:咨询者和医生应用结构化问卷完成基于需求的避孕咨询。医生在线记录每例咨询者的反应;咨询者在咨询后立即进行问卷调查, 并在6个月后通过结构化的在线随访来评估整个过程。

结果:共有92名妇科医生和1176名女性参与:951名女性完成了咨询后的即时调查, 145名妇女参加了6个月后的在线评估。对目前避孕方法的满意度有了很大提高:结果显示对避孕方法“非常满意”的妇女人数增加了30%。这包括启用、更换以及维持避孕方法。女性对这样的结构化方法非常满意;95%的女性认为咨询是“好的”或“非常好的”和“全面详细的”。

结论:采用结构化方法传递适合该女性需要的特定信息, 可以帮助她们从广泛的避孕方法中进行选择, 在某些情况下, 还可以更换更适合个人需要的避孕方法, 并最终提高对选择的满意度。

Introduction

Shared decision making between women and healthcare providers (HCPs) plays an important role in contraceptive counselling. It supports patient decision making by helping women consider their preferences and values regarding their contraceptive needs at different stages of reproductive life and then allows HCPs to structure the discussion to support a decision. Shared decision making can lead to greater satisfaction with contraceptive counselling when compared with provider-led decisions [Citation1,Citation2]. Women are also more likely to be satisfied with their chosen method when compared with those reporting a solely patient-driven decision [Citation2]. Such an approach also addresses the potential mismatch between women's and HCPs’ information priorities for contraceptive decision making and counselling [Citation3].

A key step in achieving a shared decision-making approach is understanding what is important to women seeking contraception. Although there is a high prevalence of contraceptive use among women in Germany, there is a lack of valid data regarding their contraceptive needs and preferences [Citation4,Citation5]. Surveys of contraceptive use in Germany show that combined oral contraceptives (COCs) remain the most commonly used method, with little use of methods such as the contraceptive ring, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), copper intrauterine device (IUD) or hormonal implant [Citation4,Citation5]. These surveys also show a lack of knowledge regarding how different methods work [Citation5] and their effectiveness [Citation6,Citation7]. For example, studies show that women consistently overestimate the effectiveness of COCs and underestimate the effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods [Citation6–8].

The Thinking about Needs in Contraception (TANCO) studies, conducted initially in Germany [Citation5] and then expanded across 10 EU countries [Citation8], showed that HCPs consistently underestimate women’s interest in hearing about different methods. This mismatch in understanding the need for knowledge and information may contribute to dissatisfaction with contraceptive methods [Citation9]. One particular example is the growing discontent with hormone-containing contraceptives [Citation7]. The resulting ‘hormonophobia’, where women feel they need to take a break from the hormones or are concerned about the impact of hormone-containing methods on emotional well-being [Citation7,Citation10,Citation11], can deter women from considering these highly effective options [Citation7]. The importance of shared information was highlighted in the Contraceptive Health Research of Informed Choice Experience (CHOICE) study [Citation12]. Involving over 9000 women aged between 14 and 45 years, the study showed that expanding the information about different methods and allowing women to choose or make the decision with their HCP helps them to select options that encourage continuation and satisfaction [Citation12].

The assessment of needs and expectations as a first step in the patient-centred counselling process can be done by either directly asking women using mainly open questions (interview approach) or using a systematic set of questions which could be given to women in advance of the consultation (questionnaire approach).

The Contraceptive Counselling (COCO) study was designed to test whether a systematic assessment of contraceptive needs and preferences via standardised questions (questionnaire approach) could:

Allow the physician to tailor the information given to a woman during a consultation, i.e., include those methods that match her needs and exclude those that are incompatible with her preferences.

Allow the woman to become more involved in the decision-making process and potentially increase her satisfaction with the currently used method or with the decision to use another method that better fits her needs.

Increase satisfaction with the consultation on both sides (women and physicians).

Methods

In the first phase of the study, we defined the needs-based structured approach as a model. First, we defined a list of questions to assess needs, concerns and expectations. (questionnaire approach) (). The questionnaire content was based on insights gathered from the TANCO [Citation5,Citation8] and CHOICE [Citation12] studies and the professional counselling experience of the authors (PGO and JB).

Table 1. The COCO study structured decision-making approach.

Using the responses to the questionnaire, the gynaecologist could exclude, or demote to second line, those methods that were incompatible with the identified needs, as part of the ‘exclusion’ step. The remaining list of methods compatible with the woman’s identified needs would then be established as part of the ‘inclusion’ step. These needs-oriented methods would then be at the core of the information provided by the gynaecologist and discussed with the woman as part of an educative and shared decision-making process.

Office-based gynaecologists (n = 149) were invited to participate in the second phase of the study. They were asked to conduct structured, needs-based contraceptive counselling sessions with fertile women, aged 16–30 years attending their office or practice for contraceptive advice, and record the individual responses online.

Participating women were invited to evaluate the process, initially via an immediate post-consultation questionnaire and then approximately 6 months after the consultation. Feedback on the clarity and usefulness of the structured approach was also gathered from participating physicians via an online questionnaire.

Survey design, distribution logistics and administration were coordinated by Psyma Health and Care, an independent market research company, and funded by the sponsor (Jenapharm). International review board approval was not sought as patient response data would be anonymised. Statistical analyses of descriptive and comparative data (χ2 test) were carried out by Psyma Health and Care using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Participating HCPs did not receive any fees for taking part in the study but could elect to receive an informational incentive in the form of office/practice reports with aggregated study results. Women who participated in the study were invited to take part in an online competition to win a tablet device. The study took place between October 2018 and March 2019. The follow-up survey with women took place in June 2019.

Results

Participants

An invitation to take part in the COCO study was sent to 149 gynaecologists; 92 gynaecologists (62%) conducted a minimum of five contraceptive counselling sessions and completed the survey regarding the COCO concept.

Participating gynaecologists held structured counselling sessions with 1176 women aged between 16 and 30 years. The women’s mean age was 23 years and 75% were nulliparous. The three most commonly used contraceptive methods by participating women were the COC (41%), condoms only (22%) and the LNG-IUS (5%); 17% reported they were not using any contraception (). The immediate post-consultation questionnaire was completed by 951 women; 338 expressed interest in the follow-up survey and 145 completed the structured online interview 6 months after the consultation.

Table 2. Use of contraceptive methods by women participating in the structured counselling sessions (N = 1176).

Needs assessment questionnaire

The structured needs assessment identified four key findings:

Of the participating women, 86% (n = 1011) had no plans for children in the next 3+ years.

Contraceptive reliability was regarded as most important by 49% of women and was of particular importance to younger women (16–20 years, 71%). Only 19% of the women considered contraceptive reliability ‘relatively important’.

More than half of all women in the study (55%, n = 647) reported they would like their contraceptive method to have a positive effect on their periods (shorter, lighter, less painful, less often or not at all); while 45% (n = 529) wanted to have their periods as before (29% regularly as before, and 16% as before but not heavier or more painful).

Almost 40% (n = 447) of participating women expressed concerns about hormone-containing contraception: 20% (n = 235) of women reported a preference for hormone-free contraception and 18% (n = 212) for methods containing a lower hormone dose. Concerns about the negative impact of hormones on mental well-being/mood swings (58%) were the main driver of these negative attitudes to hormones. Other areas of concern included the risks of thrombosis (35%) and cancer (20%).

Number of methods discussed, preferences and recommendations

All contraceptive methods were scored according to the women’s answers to the individual questions, hence reflecting the capability of the methods to meet their needs. The resulting ranking, however, was only informative and did not prevent the women and gynaecologists from discussing all appropriate methods. On average, four to five contraceptive methods were discussed with the women during the structured consultation. In 30% of consultations, five methods or more were discussed. The number of contraceptive methods discussed was independent of the women’s age, parity and current contraceptive behaviour and did not influence women's preference for a method, with one exception: the more methods that were discussed, the less often copper-based methods were considered an option. The number of methods discussed had a slight influence on satisfaction with the counselling process: 91% of women advised about one or two methods (n = 314) were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the counselling compared with 96% of women advised about three or more methods (n = 862). Nonetheless, the number of contraceptive methods discussed ultimately had no influence on a woman’s confidence in her current method or desire to reconsider or change method (details not shown).

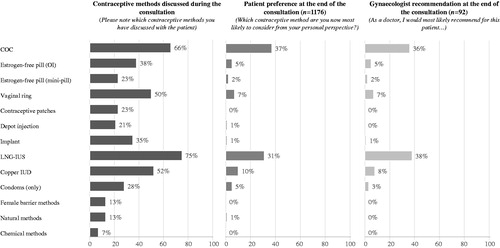

A summary of the methods discussed, the gynaecologist’s recommendation and the women’s final preference are shown in . Contraceptive reliability featured in 25% of women’s preferences and 26% of gynaecologists’ recommendations. Consideration of tolerability/side effects (total 22%, but 27% for women aged 16–20 years) was equally important for both gynaecologists and women. Hormonal burden and method application were cited as the main reasons for a specific recommendation by 10% and 13% of gynaecologists, respectively (compared with 16% and 26% of women, respectively).

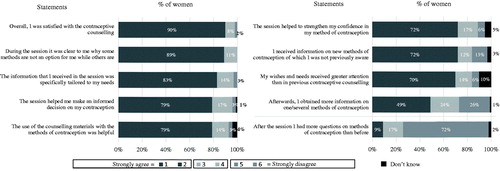

Evaluation of the counselling session

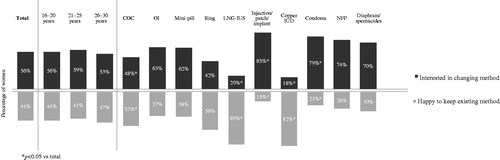

Both participating women and gynaecologists were asked to evaluate the needs-based structured counselling session in terms of the overall value of the approach, specific questions related to its clarity, and whether it was helpful and identified their needs ( and ). The counselling was rated ‘very good’ or ‘good’ and ‘comprehensive and detailed’ by 95% (n = 903) of the women. It was rated ‘understandable’ and ‘identified my situation well’ by 93% (n = 884) of women. Over half of the women (56%, n = 533) expressed interest in changing their current method as a result of the counselling (). The gynaecologists (n = 92) were somewhat more critical of the counselling approach overall, with 72% rating it as ‘very good’ or ‘good’ (). However, 81% considered the questions to be ‘very good’ or ‘good’ in terms of being understandable for women and 83% ‘completely agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that the counselling sessions were helpful for women.

Figure 2. Impact of the structured counselling approach on considering change of method (immediate post-counselling survey; all women using contraception, n = 790) (*p < .05). IUD: intrauterine device; NFP: natural family planning; OI: ovulation inhibitor.

Table 3. Women’s feedback on the use of the structured counselling approach (n = 951).

Table 4. Gynaecologists’ feedback on the use of the structured counselling approach (n = 92).

Post-consultation survey at 6 months

Of the 951 women who took part in the immediate post-consultation survey, 338 (36%) shared contact details for follow-up. Of this subgroup, 43% (n = 145) took part in the structured online evaluation at 6 months. The majority (90%, n = 131) provided a positive assessment of the contraceptive counselling (): 83% (n = 120) of women agreed with the statement that they had received information based on their needs. Importantly, 79% (n = 115) indicated that it had helped them to make an informed decision and 72% (n = 104) said that they had received information on new methods of contraception of which they were previously unaware. In addition to the focus on individual needs, particular mention was made of the extensive and comprehensive counselling on different methods of contraception, the time taken by the gynaecologists and the open atmosphere during the session. However, 40% of women could see how the counselling approach could be optimised. Criticism of the approach focussed on the (still) lack of time, the occasionally impersonal nature of the interaction, the inability of the predefined questions to adequately reflect the reality for some women, and the lack of neutrality in some cases.

At 6 months, 15% (n = 22) of the women taking part in the 6 month follow-up reported a change of contraceptive method and a further 8% (n = 12) started using contraception as a result of the contraceptive counselling. When asked which aspects of the counselling had led them to (re)consider their contraception, the two biggest factors were ‘good involvement in the decision-making process/ability to have a say’ (85%) and ‘my specific needs/wishes were considered’ (84%) (details not shown).

Satisfaction with contraceptive method

The results showed that a high percentage of women were dissatisfied with their current contraceptive method (). Prior to the counselling, 35% (n = 340) of the women currently using contraception (n = 972) reported they were very satisfied with their current method; 33% (n = 321) reported they were somewhat satisfied but also aware that an alternative method might be more suitable, and 32% (n = 311) were generally rather dissatisfied with the current contraceptive method and considered switching.

Table 5. Women’s satisfaction with their contraceptive method.

When looking at users of different methods, the proportion of women very satisfied with use of the LNG-IUS was significantly greater when compared with women’s satisfaction overall (83% vs 35%; p < .05). The proportion of women very satisfied with the use of condoms was significantly lower when compared with women’s satisfaction overall (12% vs 35%; p < .05). The most common reasons for dissatisfaction included reliability of the current method, particularly for younger women and those using condoms and natural family planning methods. This was followed by the application/handling, particularly in condom users and women aged 26–30 years. Tolerability (side effects) was the main concern expressed by women using hormonal methods.

At the time of the follow-up survey at 6 months, two-thirds (65%, n = 83) of the women using any contraceptive method reported they were very satisfied and/or now felt very comfortable with their current method; 30% reported they were somewhat satisfied but still considered that an alternative method might be more suitable, and only 5% expressed dissatisfaction with their current method. This was highly statistically significant when compared with all women using contraception and answering the questionnaire prior to the consultation (p < .01), and even more so when only the women were considered who took part in the follow-up survey. Owing to the small sample size, no further subgroup analyses were done.

Discussion

Findings and interpretation

The COCO study evaluated the systematic assessment of women’s needs, preferences and concerns regarding contraceptive methods as a first step in the counselling process and the potential for this information to allow the health care professional to adapt his/her sharing of information about methods to those needs.

Women were highly satisfied with the structured approach. It helped them to consider their preferences and values and look at how these related to the available contraceptive options and, in some cases, reconsider their current method. After counselling, women chose from a broader range of methods, reflecting the value in receiving more information about the different options. Some women also felt more confident with their current method of contraception, which may contribute to improved adherence and correct method use. Overall, the structured approach and the associated counselling were largely perceived positively, particularly by the women involved.

From the gynaecologists’ perspective, individual reports indicated that the structured approach was in some cases seen as very insightful. It helped gynaecologists to structure the decision support around preferences and values expressed by women and tailor the discussion accordingly. It was regarded as cumbersome by some gynaecologists, which might partly explain the somewhat lower overall rating ( and ).

The considerable diversity regarding the main reason behind contraceptive choice, and lack of emphasis on any particular attribute, further emphasises the highly individual nature of that choice. However, our approach shows that women’s decisions can be supported very effectively with a small number of key questions about reliability, application, effect on menstruation, and hormone content.

In a study that looked at whether a structured approach to counselling could tailor the number and type of methods discussed to the individual, it is interesting to note that the number of contraceptive methods discussed was independent of the age, parity and current contraceptive behaviour of the women. It did not play a part in which methods were discussed, or influence the satisfaction or consideration of a change of methods. This suggests that providers need not think about limiting the number of methods discussed per se but be guided by women’s individual needs and preferences. Furthermore, responses were often an opportunity for the doctors to configure the counselling more or less comprehensively.

Differences and similarities in relation to other studies

Contraceptive use among women in this study reflects the findings of other national and European surveys regarding use of COCs and LARC methods [Citation6–8]. Similar to the findings in the TANCO studies [Citation4,Citation8], women’s interest in reconsidering and changing their method was underestimated by the HCPs participating in the COCO study. We observed that 56% of the women were inclined to change their current contraceptive method, more than was estimated by the gynaecologists (42%).

Previous studies support the influence of patient-centred counselling on contraceptive method choice [Citation13,Citation14]. These studies involved the use of an algorithm comprising approximately 50 questions, and the underlying scoring incorporated both participants’ responses and the effectiveness of the available methods [Citation14]. Of note, the effectiveness of the contraceptive method chosen at the time of the visit was the primary outcome in the first study [Citation13]. In the COCO study, this was considered to be of secondary importance; however, we did observe a substantial shift in women’s preference towards more effective methods ().

A further study by Garbers et al. [Citation15] showed that tailored health materials significantly improved contraceptive method continuation and adherence. A patient-centred study by Holt et al. [Citation16] showed that use of a contraceptive decision support tool comprising educational and interactive modules, prior to contraceptive counselling, enhanced the experience of contraceptive counselling and informed decision making. Although the tool enhanced contraceptive knowledge [Citation16], it had no effect on 7 month continuation [Citation17].

Strengths and weaknesses

As with all studies, there are some limitations. There are potential biases around the selection of gynaecologists and possibly patients for counselling, and the follow-up at 6 months post-consultation must be subject to some recall bias, despite the majority of women reporting they remembered the consultation well. Other limitations include the contradictory nature of some of the findings in the study, e.g., high need for contraceptive reliability but low impact of this question in the counselling session and methods discussed. The results of the algorithm do not necessarily allow true neutrality and objectivity: when stratified by age groups and current contraceptive method, there were few observed differences even though the needs of a woman vary at different ages and stages of life.

In the counselling sessions, the mean number of methods discussed was 4.5 (range 1–14), indicating that some gynaecologists did not always use the preferences and values expressed by women to focus on a few methods but used the structured approach to provide comprehensive and very broad advice as part of best practice (do a ‘good job’). There are likely to be considerable differences regarding gynaecologists’ preference for the extent and coverage of the counselling, particularly given the limited availability of guidelines except for those around medical eligibility. Also, only office-based gynaecologists took part in the study. While the vast majority of contraceptive counselling is undertaken by gynaecologists, the potential for different approaches to other health care providers, such as general/family physicians, cannot be excluded. Similarly, differences in health insurance coverage may affect counselling delivery and outcomes. Importantly, most women in Germany have to pay for contraceptives after reaching the age of 22. While we recognise that economic issues can impact the choice of a contraceptive method, this aspect was not in the scope of this study.

Relevance of the findings: implications for clinicians and policy-makers/health care providers

This is the first survey in Germany looking at the use of a structured approach to contraceptive counselling. It shows that providing more, detailed information tailored to women’s needs can lead to a consideration of other methods and even a change of method more suitable to individual needs, in some cases, but ultimately to increased satisfaction with the chosen method. This was observed not only for starters or switchers but also for women who continued with their previous method. This suggests that a structured counselling approach can provide reassurance to a woman that the chosen method best matches her contraceptive needs.

Unanswered questions and future research

Future progress can be made by optimising the structured approach by either building in a method to weight the ‘need’ in terms of relevance and/or including a ‘screening’ process prior to counselling. The individual reports from gynaecologists indicated that the effort required was too high for the doctors. Initial insights from the follow-up survey at 6 months also revealed that some patients found the counselling rather impersonal due to their gynaecologist’s focus on inputting data into a tablet. Therefore, the format of the structured approach should be reviewed and perhaps supplemented by self-report questionnaires for women to complete in the waiting room and share during the consultation.

Conclusion

Effective contraceptive counselling remains a challenge. The inclusion of individual needs in the decision-making process is highly valued and could contribute not only to a higher level of satisfaction, acceptance and adherence to the current method but also to a better choice of or change to a more suitable method. In many cases, compromises are needed that could best be achieved in a process of shared decision making where there is a balancing of risks and benefits relevant to a woman’s needs and her medical profile.

Acknowledgements

This publication and its content are solely the responsibility of the authors. Medical writing assistance was provided by Lynn Hamilton of Clark Health Communications under the direction of the authors and paid for by Jenapharm GmbH & Co. KG.

Disclosure statement

Johannes Bitzer has worked as an adviser for and received honoraria from Bayer AG, Merck, Teva, Exeltis, Lilly, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Vifor and Gedeon Richter. He has also given invited lectures and received honoraria from Bayer AG, Merck, Johnson and Johnson, Teva, Mylan, Allergan, Abbott, Lilly, Pfizer and Gedeon Richter. Patricia Oppelt has no disclosures. Alexander Deten is an employee of Jenapharm GmbH & Co. KG.

References

- Bitzer J, Marin V, Lira J. Contraceptive counselling and care: a personalized interactive approach. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22(6):418–423.

- Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Steinauer J, et al. Development and field testing of a decision support tool to facilitate shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1374–1381.

- Donnelly KZ, Foster TC, Thompson R. What matters most? The content and concordance of patients’ and providers’ information priorities for contraceptive decision making. Contraception. 2014;90(3):280–287.

- Oppelt PG, Baier F, Fahlbusch C, et al. What do patients want to know about contraception and which method would they prefer? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(6):1483–1491.

- Oppelt PG, Fahlbusch C, Heusinger K, et al. Situation of adolescent contraceptive use in Germany. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018;78(10):999–1007.

- Kopp Kallner H, Thunell L, Brynhildsen J, et al. Use of contraception and attitudes towards contraceptive use in Swedish Women-A Nationwide Survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125990.

- Hellström A, Gemzell Danielsson K, Kopp Kallner H. Trends in use and attitudes towards contraception in Sweden: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24(2):154–160.

- Merki-Feld GS, Caetano C, Porz TC, et al. Are there unmet needs in contraceptive counselling and choice? Findings of the European TANCO study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23(3):183–193.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(5):1105–1113.

- Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA). Contraceptive behavior in adults 2018 (in German); [cited 2021 Mar 18]. Available from: www.bzga.de/infomaterialien/sexualaufklaerung/verhuetungsverhalten-erwachsener-2018.

- Fiala C, Parzer E. 2019. Austrian contraception report 2019 (in German); [cited 2021 Mar 18]. Available from: www.verhuetungsreport.at.

- Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE Project in review. J Womens Health. 2015;24(5):349–353.

- Garbers S, Meserve A, Kottke M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a computer-based module to improve contraceptive method choice. Contraception. 2012;86(4):383–390.

- Kottke M, Cwiak C, Goedken P, et al. Development of a contraceptive survey to be used in a computerized tool providing personalized output (meeting abstract). Contraception. 2007;76(2):174.

- Garbers S, Meserve A, Kottke M, et al. Tailored health messaging improves contraceptive continuation and adherence: results from a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2012;86(5):536–542.

- Holt K, Kimport K, Kuppermann M, et al. Patient-provider communication before and after implementation of the contraceptive decision support tool My Birth Control. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(2):315–320.

- Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Fox E, et al. Cluster randomized trial of a patient-centered contraceptive decision support tool, My Birth Control. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):565.e1–565.e12.