Abstract

Background

Unintended pregnancy has a huge adverse impact on maternal, child and family health and wealth. There is an unmet need for contraception globally, with an estimated 40% of pregnancies unintended worldwide.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed and specialist databases for systematic reviews addressing contraceptive choice, uptake or use, published in English between 2000 and 2019. Two reviewers independently selected and appraised reports and synthesised quantitative and qualitative review findings. We mapped emergent themes to a social determinants of health framework to develop our understanding of the complexities of contraceptive choice and use.

Findings

We found 24 systematic reviews of mostly moderate or high quality. Factors affecting contraception use are remarkably similar among women in very different cultures and settings globally. Use of contraception is influenced by the perceived likelihood and appeal of pregnancy, and relationship status. It is influenced by women’s knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions of side effects and health risks. Male partners have a strong influence, as do peers’ views and experiences, and families’ expectations. Lack of education and poverty is linked with low contraception use, and social and cultural norms influence contraception and expectations of family size and timing. Contraception use also depends upon their availability, the accessibility, confidentiality and costs of health services, and attitudes, behaviour and skills of health practitioners.

Interpretation

Contraception has remarkably far-reaching benefits and is highly cost-effective. However, women worldwide lack sufficient knowledge, capability and opportunity to make reproductive choices, and health care systems often fail to provide access and informed choice.

摘要

背景:意外怀孕对孕产妇、儿童和家庭的健康和财富产生巨大的不利影响。全球对避孕的需求未得到满足, 全世界估计有 40% 的怀孕是意外怀孕。

方法:我们系统地搜索了 PubMed 和专家数据库, 查找2000年至2019年间以英语发表的关于避孕药具选择、获取或应用的系统评价。两名评价者独立选择和评估报告, 并综合定量和定性评价结果。我们将新兴主题映射到健康框架的社会决定因素, 以加深我们对避孕选择和使用复杂性的理解。

结果:我们发现了 24 篇大部分为中等或高质量的系统评价。在全球不同文化和环境中的女性中, 影响避孕使用的因素非常相似。选择避孕受怀孕的感知可能性和吸引力以及关系状况的影响。它受女性知识、理念和药物副作用和健康风险的看法的影响。男性伴侣具有强大的影响力, 同龄人的观点和经历以及家庭的期望也是如此。缺乏教育和贫困与避孕药具使用率低有关, 社会和文化规范会影响避孕药具以及对家庭规模和时间的期望。避孕的使用还取决于其可用性、卫生服务的可及性、保密性和成本, 以及卫生从业人员的态度、行为和技能。

解释:避孕具有非常深远的好处, 并且具有很高的成本效益。然而, 世界各地的妇女缺乏足够的知识、能力和机会来做出生殖选择, 而医疗保健系统往往无法提供知情选择和获取方式。

Introduction

The responsible planning of births [is] one of the most effective and least expensive ways of improving the quality of life on earth […] and one of the greatest mistakes of our times is the failure to realise that potential.

UNICEF. The state of the World’s children 1992 [Citation1].

Globally, an estimated 40% of pregnancies are unintended (that is, they occur too soon or are not wanted) [Citation2]. An estimated 43% of pregnancies in the global south are unintended, and 84% of those occur in women with an unmet need for reliable contraception [Citation3]. If all unmet need for contraception were satisfied in low income regions, unintended pregnancies could fall by an estimated three-quarters, and maternal deaths by a third [Citation4]. Two Lancet series have highlighted the extent of both the achievements and the neglect of contraception worldwide [Citation5,Citation6], and there are a raft of international initiatives to reduce the global unmet need [Citation7].

The far-reaching benefits of contraception relate to many of the sustainable development goals [Citation8] and reducing unplanned pregnancy is a priority for the global health community [Citation9]. There are now many different contraception products, although access to any or all of these is difficult or impossible in many countries [Citation10]. However, even in countries where contraception is free and widely available, there are many obstacles to access and successful use of contraception.

This review aimed to systematically synthesise the global evidence about factors that influence contraception access, choice, and use, to inform policy and clinical practice.

Methods

We registered a protocol with PROSPERO [Citation11] and systematically searched PubMed and databases of systematic reviews for systematic reviews which addressed factors influencing contraceptive choice, uptake, or use, published in English, from the year 2000 to June 2019 and applied pre-determined eligibility criteria (see Supplementary Material Appendix 1). Two reviewers independently selected and appraised reports. We relied on review authors’ assessments of the quality of primary studies. Established frameworks for assessing quality differ for quantitative and qualitative studies; we dealt with this by applying a checklist that focuses on the appropriateness of methods considering the review’s purpose [Citation12]. We extracted data using EPPI-Reviewer software [Citation13] (Supplementary Material Appendix 3).

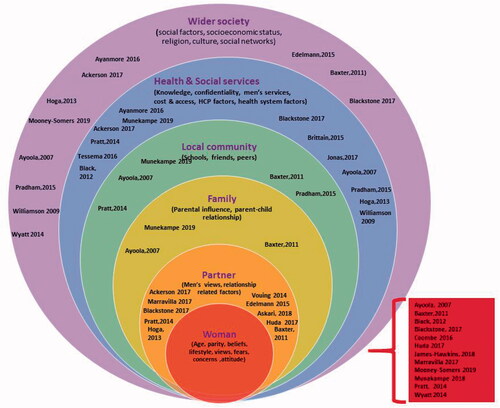

We conducted framework synthesis to categorise and combine quantitative and qualitative review findings [Citation14], seeking congruent and contradictory findings and patterns across the data. A social determinants of health framework was used to locate emergent themes across different domains: individuals, partners, family, peers, community, health services and wider society [Citation15]. Emerging themes were discussed by the whole team to develop our understanding of the complexities of contraceptive choice and use. Evidence supporting each synthesis statement was considered reliable where it was drawn from one or more high or medium quality systematic review; or where congruent findings were drawn from different systematic reviews or individual studies (triangulation). Medium quality systematic reviews reported a clear review question, and appropriate inclusion criteria, search strategy and appraisal and synthesis methods. High quality reviews also reported independent critical appraisal by two or more reviewers and procedures to minimise errors when extracting data. In this overview, systematic reviews are referred to as ‘reviews’ and primary studies included in those systematic reviews are referred to as ‘studies’.

Results

Our findings are based on 24 systematic reviews comprising 508 primary studies with participants from all over the world, published between January 2000 and June 2019 (Supplementary Material Appendices 3 and 4).

There were 8 reviews from the global north, 12 from the global south and 4 worldwide reviews. Of the 24 reviews, 12 included only women, 2 included only men, 9 both men and women, 6 were specific to adolescents and young adults, and one focussed on health care workers.

Supplementary Material Appendix 5 reports the quality of the included reviews. The two high quality reviews meta-analysed studies correlating people’s characteristics with contraception use [Citation16,Citation17]. Eleven moderate quality reviews synthesised views and experiences, employing appropriate methods but not clearly avoiding error or bias in critical appraisal or data extraction [Citation18–28]. Eleven reviews did not clearly use appropriate methods for searching and/or critical appraisal [Citation29–39]. Supplementary Material Appendix 6 notes the quality of primary studies included in the reviews.

Team discussions resulted in nine synthesis statements that spanned the social determinant of health domains ()

Women’s perceptions of fertility, pregnancy and contraception

Synthesis statement 1:

Contraception use is influenced by perceived likelihood and appeal of pregnancy, and relationship status

Contraception use is influenced by judgements about the likelihood and consequences of pregnancy in the context of different types of relationship [Citation16,Citation17,Citation19,Citation25,Citation29].

One low quality review found that some women did not use contraception because they believed they were at low risk of pregnancy because of being too old, breast feeding or having sex too infrequently for example, or thinking that they or their partners were infertile [Citation29]. Others held passive, ambivalent, negative, or fatalistic attitudes towards pregnancy.

In the USA, gaps in method use were more common among cohabitating women compared to married women, among those with no current relationship, and among those believing that their partner was not monogamous [Citation16]. Some North American women saw benefits in having babies early: ‘asserting adulthood, developing family stability, getting attention and attaining greater influence with their partner’ [Citation25]. In a meta-analysis of studies mostly from the USA, repeat teenage pregnancy was more likely when there was a wide age difference between the woman and partner, more partner support, and living with a partner [Citation17].

Relationship status does not have a consistent impact upon contraception use. For example, some Irish women use contraception once in an established relationship, while others took more risks in loving relationships [Citation25]. Young Britons showed greater pregnancy risk-taking in long-term trusting relationships and where there was a strong emotional attachment [Citation19], and less risk taking with non-regular partners [Citation16].

Adolescents in low- or middle-income countries sometimes avoided contraception because they needed to prove to their partners and their communities that they were fertile, particularly if they were recently married [Citation39].

Synthesis statement 2:

Contraception use is influenced by women’s knowledge, beliefs, perceptions of health risks and previous experience.

Insufficient or inaccurate knowledge, and concerns about side effects are major barriers to contraception use globally [Citation24,Citation25,Citation27–31,Citation35,Citation37–39].

Most evidence comes from the global north where barriers included poor understanding of the reproductive cycle, fertility, and ‘safe’ periods, sometimes over-estimating the effectiveness of withdrawal methods. Women had poor knowledge about how to access services [Citation29] and how to use contraception correctly, and poor capability to integrate knowledge into practice [Citation25]. Approximately half of American women who had never been pregnant had incorrect knowledge about contraception use and side-effects, and most had not heard of intrauterine contraceptives [Citation30].

Women are influenced by perceived characteristics of different contraceptives [Citation34], including ease of use, probability of omission, perceived efficacy, and health benefits, return to fertility, foreign body aversion, needle phobia, compatibility with breast feeding, pre-sex preparation, and concerns about contraceptive side effects, hormones, health risks, effect on sexual pleasure, menstrual changes, and the need to visit to a health care provider. Also influential in contraception uptake is prior experience, vicarious experience, expectations, and concealability.

Evidence from the USA identified concerns that contraception is unnatural, foreign, and invasive, and worries about retention of blood or irregular bleeding when using hormones [Citation29]. Other concerns include weight gain or loss, headaches, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, dizziness, breast enlargement, acne, leg pain, varicose veins, bloating, low energy, depression, stress, and mood changes as well as concerns about future infertility and cancer. Young people in the UK were also concerned that hormonal contraception (including emergency contraception) is ‘unnatural’ and could be harmful and cause side effects [Citation19]. Women in the global south expressed similar concerns about side effects (menstrual disruption, fears concerning fertility and cancer and weight gain or loss) which deterred them from using contraception [Citation27,Citation31,Citation39]. Concerns about future infertility present a barrier [Citation29], particularly to the use of IUDs [Citation30], and to hormonal contraceptives [Citation31].

Studies of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) from the global north highlighted women’s concerns about weight gain, pain, cramping, irregular bleeding and moodiness, insertion and removal procedures, side effects, potential impact on fertility and the term ‘long acting’, while the most important positive qualities were high efficacy, long-term protection and ‘fit and forget’ [Citation32].

Condoms can be difficult to acquire, store, remember and use (e.g., discomfort, breakage, and messiness), and condoms can reduce sexual pleasure, spontaneity, fun and romance [Citation29]. Women in the global north disliked condoms because they interrupt sex, are seen as unromantic, a barrier to intimacy, uncomfortable, not at hand when needed, difficult to organise and forgotten under the influence of alcohol or not used in the heat of the moment [Citation19,Citation25]. Some methods can be difficult to use correctly, for example oral contraceptives which must be remembered every day [Citation25]. In a UK study, condoms were perceived positively for protecting against sexually transmitted disease as well as pregnancy [Citation19].

Many Australian women were misinformed about how to access emergency contraceptive pills, and about how they work, with many women believing they induce abortion [Citation38].

Lack of sex and relationships education is associated with increased rates of adolescent pregnancy in developing countries [Citation24,Citation28]. Limited knowledge about sexual and reproductive health among adolescents led to reduced access to contraception and safe abortion services, especially among unmarried adolescents [Citation39]. For example, most women in Bangladesh were aware of several family planning methods but often did not know how to use them correctly and had misconceptions or fears about side effects [Citation37]. Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa confirms that lack of knowledge or misinformation is a barrier to contraception use [Citation28,Citation31,Citation35]. In crisis affected areas of sub-Saharan Africa [Citation35], most women knew that different methods were available, but there were many misconceptions, such as fear of death, infertility and side effects, which contributed to lack of use, despite a desire to space and limit births.

Influence of social networks and wider society

Families’ expectations and relationships with partners have a strong influence on contraceptive use [Citation16,Citation17,Citation19,Citation25,Citation31]. Women’s use of contraception is positively associated with self-efficacy and self-esteem [Citation31] but globally, women’s contraception decision-making is heavily influenced by others including partners, peers, family, and wider society.

Synthesis statement 3:

Male partners have a powerful influence on contraception use

Men around the world see contraception to be a woman’s responsibility [Citation21,Citation25,Citation33], but men are, nevertheless, very influential, and women’s choices are influenced by their support or opposition [Citation8,Citation28,Citation34–36].

North American men felt that preventing unplanned pregnancies was not their concern. They showed little responsibility and inconsistent use of condoms [Citation20].

Male partners of disadvantaged women in the USA often influenced decisions about contraception: not wanting to wear a condom, not wanting women to use birth control, disapproving of specific methods, discomfort with changes in women’s bodies, and women were sometimes reluctant, embarrassed, or afraid to ask a partner to use condoms [Citation21,Citation29]. Similarly in the UK, reasons for not using condoms included partners’ views, not having condoms available, not having the skills to discuss condom use, the impact on pleasure, and fear of conflict or losing partners if they insisted [Citation19,Citation25].

Increased interaction between couples was seen in some studies (20) to lead to increased willingness to have children, and in other studies (9) to more use of contraception and fewer children [Citation36]. Together these associations may be evidence of joint decision-making.

Power dynamics within relationships are important [Citation33]. Men’s attitudes to contraception use vary widely in Sub-Saharan Africa [Citation31]. Studies suggest men support contraceptive use in general, and have a role in decisions about family size, but a lesser role in contraception choice and use [Citation33]. Men who accompanied their wives to family planning services could be negatively perceived as being dominated by their wives, and may be embarrassed to find themselves in ‘female’ places. Male partners were more likely to be involved in family planning decisions if they were co-habiting and older [Citation31].

A husband’s disapproval of contraceptives (or fear of a husband’s disapproval) may prevent women’s use of contraception [Citation31]. A woman adopting modern contraception, could be considered disrespectful, and condoms can be viewed as suggesting infidelity [Citation31]. Also in sub-Saharan Africa, non-use of contraceptives and male’s responsibility for condoms influence adolescent pregnancy [Citation29]. Husbands and others influenced women’s avoidance of contraceptives in crisis affected areas of Sub Saharan Africa [Citation35]. For instance, men had a desire for large families, and held misperceptions and a lack of trust in western medicine. Men were more in favour of contraception if they were better educated or if they wanted to avoid a pregnancy that could jeopardise a move to another refugee camp [Citation35]. In Uganda, men’s perceptions positively influenced women’s uptake and use of contraception, and relationship satisfaction was positively associated with contraceptive use in Ghana [Citation31].

Coercion, control, and forced sex can be factors in unprotected sex [Citation29]. Contraceptive use may be controlled by providing gifts or money in exchange for sex and women may be coerced into condom-less sex because condoms reduce sexual pleasure [Citation27].

Synthesis statement 4:

Family members’ expectations have a powerful influence on contraception use

Families’ attitudes (especially parents’) shape women’s uptake of contraception [Citation19,Citation24–26,Citation39].

Family and friends’ attitudes influenced unprotected intercourse in North America [Citation29]. Some families were opposed to the use of birth control; other parents wanted a grandchild. Unprotected sex was sometimes the result of women not wanting parents to know they were having sex or using birth control.

In the UK, parents were influential in different ways [Citation19]. Some parents supported women obtaining contraceptives, whilst others prevented them. Although parents could be a source of information and advice, young people could only talk to them if their relationships were close. School students were often embarrassed and reluctant to discuss contraception with their parents. Where parents were involved, school students often perceived it negatively, with an overemphasis on abstinence. Swedish teenagers feared disapproval from parents and felt unable to discuss contraception, and Irish women reported using contraception secretly as pre-marital sex was not culturally accepted and they feared detection by parents or siblings [Citation25].

Parental influence has been studied a little in the global south [Citation24]. In Nepal, children of educated parents were more likely to delay marriage and pregnancy, whereas parents’ education made no difference to this in Nigeria, when parents had poor knowledge and negative attitudes towards contraception. A lack of ‘strict’ family rules was associated with a greater risk of adolescent pregnancy in Sri Lanka and Kenya. A systematic review of adolescents in developing countries identified parents, health workers, and teachers as trusted sources of information, but young people often received the most information from peers and other family members instead; girls mostly confided in their aunts, cousins, and peers while boys learnt from peers, media and pornography [Citation39].

Synthesis statement 5:

The views and experiences of peers influence women’s contraception decisions

Friends, peers and school influence young people’s use contraceptives around the world [Citation17,Citation19,Citation24,Citation25,Citation29,Citation30].

Friends and peers were sources of information for adolescent girls from Sri Lanka, Nigeria, Nepal and Kenya [Citation24]. There is a strong link between friends’ views and the use of contraception; for instance, women in Norway preferred to trust anecdotal experiences from friends and peers rather than health professionals’ advice about contraception [Citation19]. Global evidence reveals that knowing other teenage mothers is associated with repeat teenage pregnancy [Citation17].

Women in North America were influenced by friends not using birth control [Citation29]. Women in Ireland were discouraged from using contraception by worries about peers knowing they were sexually active, or using condoms or pills, due to the general unacceptability of pre-marital sex [Citation25].

Social networks play an important role in attitudes towards contraceptives in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly for men [Citation31]. In Ghana, encouragement towards contraceptive use from men’s social networks positively influenced contraceptive uptake by their wives. In Ethiopia, support for contraceptive use in women’s social networks was largely independent from men’s social network support.

A UK study linked unprotected sex with alcohol use, with decision-making compromised by lowered inhibitions, impaired judgement, and loss of control [Citation19].

Synthesis statement 6:

Social norms influence contraception use

Social norms have a powerful influence on contraception use across the world, especially attitudes to sex, contraception and (age of) motherhood.

Multiple studies reported negative perceptions of women in the global north who carry condoms [Citation19,Citation25]. Irish women reported pre-marital sex as not culturally acceptable and feeling embarrassed about going to see a doctor or buying condoms [Citation25]. Some UK studies found that using condoms or emergency contraception was perceived positively as being ‘responsible’; while in other studies termination of pregnancy and emergency contraception use can be viewed as ‘irresponsible’[Citation19]. An Australian study reported moral misgivings about using emergency contraceptive pills [Citation38].

There is a positive relationship between women’s agency (e.g., decision-making, freedom of movement) and contraceptive use in the global south [Citation22]. Studies from Sub-Saharan Africa reported positive associations with self-efficacy, self-esteem, and equitable gender attitudes, whilst men who hold a strong influence over their wives often oppose the use of contraceptives [Citation31].

Studies throughout the global south identified considerable social disapproval of premarital sex and pregnancy for young women, which affects their reputations and social status, and limits access to contraception [Citation27]. Adolescent pregnancy is strongly associated with young marriage [Citation24] with younger women in Sub-Saharan Africa being less likely to use contraception [Citation31].

Some young women in Sub-Saharan Africa used pregnancy as a bargaining tool to solidify relationships [Citation27]. Where social norms allow polygamy, women may see having more children as a way to stabilise marriages, compete with other wives, and prevent husbands from taking more wives [Citation18,Citation24], although in Nigeria, husbands believed that having more children justified taking additional wives [Citation18,Citation23]. A preference for sons may lead women without sons to have more subsequent babies, and sooner (e.g., in Bangladesh)[Citation37].

There are links between religion and contraception use globally, which vary by religious background, affiliation or denomination of men or women, and of health care providers; personal beliefs and strength of belief or strictness of doctrine; degree of involvement in religious events; and the influence of religious leaders [Citation16–18,Citation21,Citation23,Citation24,Citation31,Citation34,Citation35]. The likelihood of adolescent pregnancy varies with religion in African and Asian countries, but without consistent patterns [Citation24]. In studies from Ireland, where religious influence is strong, women noted cultural, but not specifically religious, influences on their contraceptive choices [Citation25], and another review noted religious objections which were not specified [Citation29]. A systematic review of 20 surveys globally did not identify religious or moral reasons as important factors in contraception decision-making [Citation34], although evidence concerning religious influence on contraceptive choice and use is scarce from highly religious countries and sub cultures

Synthesis statement 7:

Lack of education and poverty is linked with low contraception use

Socio-economic status influences contraception use and attitudes to pregnancy, motherhood and abortion across the world.

In the global North, lower educational attainment is associated with repeat teenage pregnancy [Citation17]. In the UK, early pregnancy and young motherhood is more acceptable within disadvantaged populations and ethnic minority communities [Citation19], and early pregnancy was associated with negative attitudes towards contraception. Women from advantaged backgrounds viewed emergency contraception and abortion more positively than women from disadvantaged backgrounds [Citation19], and family planning was more accepted among men from higher social class in the US [Citation21].

In the global south, low socio-economic status, little or no education, and lack of access to employment are the most common risk factors associated with adolescent pregnancy [Citation24,Citation35]. Conversely, better educated adolescents knew more about contraception [Citation39] and are more likely to use modern contraceptives [Citation31].

Attitudes to early pregnancy vary with ethnicity [Citation24]. For example, young motherhood was perceived more positively among some UK minority ethnic communities [Citation19,Citation24].

Characteristics of health services

Synthesis statement 8:

Contraception use depends upon the availability of methods, accessibility, confidentiality, and costs of health services

Health service availability influences contraceptive use globally [Citation18,Citation25–27,Citation29–31], with greatest negative impact in the global south.

In the global north, contraceptive provision is influenced by guidelines, regulatory approval, health care practices and practitioner training [Citation30]. Cost, health insurance cover, and access to services influence contraception uptake [Citation16,Citation25,Citation29,Citation30]. In the USA, some gynaecologists cited lack of reimbursement as a barrier, and others feared lawsuits against them [Citation30].

Organisational factors such as staffing levels, management, and availability of materials and equipment are associated with the quality of care in family planning services [Citation26]. In African settings, clients were more satisfied with family planning services that were cleaner, open more days in the week, at more convenient times, with shorter waiting times and closer to home. Lack of information (e.g., about how to use the contraceptive method) was associated with low satisfaction with a service [Citation26]. In West Africa, contraceptive use is influenced by poor health infrastructure, unfriendly attitudes of health providers, method choices available and ineffective leadership [Citation18].

The scarcity of healthcare facilities in rural areas impacts on contraceptive use in Sub-Saharan Africa [Citation28,Citation31]. Distance to family planning clinics is a barrier in crisis affected areas, and clinics may not offer contraceptives other than condoms [Citation35].

Health service confidentiality is a very important factor for young people [Citation20]. Young people in the USA who believed that services were confidential were more likely to obtain health care without parental knowledge, discuss sex-related topics, and accept pelvic examination and contraceptive injections. Similarly in the UK, students said that they were more likely to access sexual health services if confidentiality is maintained, with confidentiality a concern in the waiting room, when seeing the doctor, and at a pharmacy. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy include long waiting time and lack of privacy at clinics [Citation28].

Confidentiality and privacy were positively associated with client’s satisfaction with family planning services in studies from Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Ghana, and Egypt [Citation26].

Synthesis statement 9:

Contraception use depends upon the attitudes, behaviour, and skills of health care personnel

Healthcare professionals have a powerful influence on access to contraception, and choice and use of methods.

Women in the global north can be dissatisfied with communication with health care professionals [Citation25,Citation29]. North American women were dissatisfied with information and explanations offered by health care professionals, discussion of side effects, lack of personalisation, lack of privacy and poor clinic environments [Citation29]. Elsewhere in the global north, women had difficulty in obtaining information about IUDs and the method was not recommended even though they were eligible, and women felt they lacked control over decision-making [Citation25].

Adolescents are more likely to be single and have poor knowledge about contraception and abortion, but in low- and middle-income countries, contraception was seen as for married people [Citation39]. Young women from Tanzania, Nigeria and South Africa feared negative reception from staff, and felt that health services were not accessible to unmarried women [Citation27]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, young women found health services unfriendly, with health workers holding negative attitudes towards adolescents. Lack of skilled health workers is associated with adolescent pregnancy [Citation28].

Young Vietnamese women felt that they rarely received adequate information about contraceptives and sex because of the sensitivity of the topic [Citation27], and American women felt embarrassed about purchasing contraceptives [Citation29]. Women seeking emergency contraception in Australia did not expect pharmacists to question them about their sexual history and considered this intrusive [Citation38].

In Sub-Saharan Africa, healthcare workers in Kenya and Zambia said that they would advise adolescents to abstain from sex if they seek contraceptives [Citation23]. In Senegal, healthcare workers imposed minimum age restrictions for providing contraceptives, as well as restrictions according to clients’ marital status. However, healthcare workers with more education and those who had received continuing education on adolescent sexuality and reproduction showed more youth- friendly attitudes and were in support of adolescent contraceptive use.

In the global south, studies from Africa (Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana) found that client satisfaction with family planning services was linked with information offered (such as information about how to use a method) [Citation26]. Providers’ age and experience were associated with client satisfaction in Kenya and Senegal; and in Egypt, client satisfaction was associated with client-provider interaction in the form of positive talk by the provider, client-centred family planning, the client choosing which contraceptive method to use, and the provider’s technical competence [Citation26]. In crisis affected areas of Sub Saharan Africa, women believed that health care providers were unqualified, and many women described being treated with disrespect in clinics [Citation35].

Negative patient–provider interactions influence the uptake of contraceptives in Sub-Saharan Africa [Citation31]. In West Africa, unintended pregnancies were associated with contraceptive shortages, and with provider attitudes such as scolding and intimidation [Citation18]. In Ghana, limited contraception options, and limited provider skills and educational tools reduced contraceptive uptake. Provider preferences for particular methods influenced how they counselled patients, leading to incomplete counselling and often excluding IUDs as an option [Citation31].

A review of intrauterine contraception (IUC) revealed a global lack of knowledge, training, and confidence among health care providers for inserting intrauterine devices, particularly in nulliparous women [Citation30]. Health care providers believed that IUC insertion carries a risk of pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. They are reluctant to offer IUCs to women who have not previously been pregnant because of perceived technical challenges, risk of uterine perforation, and risk of expulsion. Providers overestimate the risk of ectopic pregnancy and consider a past history of ectopic pregnancy to be a contraindication. Some health care providers were reluctant to recommend IUC because of beliefs that preventing implantation of a fertilised egg is morally unacceptable. Women and health care providers in Ghana feared that the IUD could migrate from the uterus to the heart, causing death.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Factors affecting contraception choice, uptake and use are remarkably similar in very different cultures and settings globally. Contraception use depends on perceptions of motherhood, the likelihood and implications of pregnancy, and perceived side effects and health risks. Women’s choices are influenced by partners, family, peers, health care providers and wider society; and by their knowledge and capacity to make decisions. Contraceptive choice is also influenced by the characteristics of methods, particularly the ease of use, invasiveness, discreteness, and impact on intimacy; and the characteristics of services, including accuracy of information provided, convenience, confidentiality, costs, and the attitudes and behaviour of healthcare professionals.

Beliefs about negative attributes of contraception are powerful and more prominent than perceived benefits. Factors such as inconvenience, concerns over side effects, and worries about future health discourage women from using contraception globally.

Stigma and secrecy concerning sex, sexuality and contraception, and gendered power imbalance impedes women’s access to accurate information and control over fertility. Women are often influenced by informal sources of information (such as friends) rather than authoritative sources.

Contraception services are unavailable or costly in many parts of the world, and embarrassment, concerns about confidentiality and health care providers’ attitudes can obstruct access and informed choice.

Strengths and limitations of this overview

This review of reviews synthesises the findings from 508 primary studies on factors influencing contraception choice and use across the world, using a rigorous synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence.

Our synthesis is limited by the geographical coverage and quality of studies included. For example, there were no studies from Central Asia, but most other global regions were represented. In addition, we would have not included certain region-specific factors by selecting only English language articles. The quality of the reviews was good enough to draw robust conclusions.

The search end date was June 2019, and the included studies were conducted some years before then. This is a potential limitation, although the review of reviews is likely to be still highly relevant because the themes apply across time and geography. The findings are theoretically transferable, and an evidence update is unlikely to add to the relevance of the findings.

Implications for policy

We propose a framework for a comprehensive policy approach to improve uptake and use of contraception. Contraception is remarkably effective and safe, with wide-ranging health benefits and a high return on investment. However, evidence consistently shows that women lack sufficient knowledge, and that myths and concerns about side effects are major obstacles to contraception uptake and adherence. Interventions that deliver accurate information about the benefits and drawbacks of all contraceptive methods are urgently required, as a necessary pre-requisite to informed choice.

Interventions tend to focus on individual women’s knowledge and decision-making [Citation40–43], but the attitudes and expectations of partners, peers, family, and wider society have a powerful influence. Strategies to increase men’s involvement in contraception are needed. Parent-led interventions can be effective [Citation44,Citation45], but our evidence shows that young people lack adequate support from parents to use contraception. Friends strongly influence choice of contraceptives, although peer-led interventions are not necessarily effective [Citation46,Citation47]. Combined educational and contraceptive-promoting interventions reduce unintended pregnancy among adolescents [Citation48].

Inadequate health services, inadequately trained or judgemental health professionals, and concerns about confidentiality are common and important barriers to contraception use, especially for young people. Better provision of services and training of heath service providers is clearly needed. For real traction, however, such efforts will need to be underpinned by attention to the complex web of social, cultural, religious factors that facilitate or hinder the use of contraception.

Implications for research

More research is needed on men’s perspectives, and those of other family members. Evidence about factors such as cultural and social norms is sparser, of variable quality and under-theorized. These are challenging areas to research, but evidence on how to support change in gender power dynamics and other socio-cultural influences that affect women’s capacity to control her fertility is needed. We have observed that evidence concerning religious influence on contraceptive choice and use is scarce from highly religious countries and sub cultures; hence, more exploratory primary studies are required to understand the influence of religion.

Conclusions

Contraception has remarkably far-reaching benefits and is highly cost-effective. However, women worldwide lack sufficient knowledge, capability, and opportunity to make reproductive choices, and health care systems often fail to provide access and informed choice. Urgent action is needed to enable informed decision-making on contraception and family planning to enhance the life chances of women and their families.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design, interpretation and reporting of the review. All contributed to and agreed the final manuscript. Dr Preethy D’Souza and Prof Sandy Oliver identified, appraised, and extracted the findings from the systematic reviews included. Prof Sandy Oliver, as corresponding author, had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (69.4 KB)Acknowledgement

The review was part of a larger study funded by National Institutes of Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- UNICEF. The state of the World’s children 1992; [cited 2018 July16]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/about/history/files/sowc_1992.pdf.

- Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R. Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45(3):301–314.

- Guttmacher Institute. ADDING IT UP: investing in Contraception and Maternal and Newborn Health; [cited 2019 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/adding-it-up-contraception-mnh-2017.

- Ahmed S, Li Q, Liu L, et al. Maternal death averted by contraceptive use: an analysis of 172 countries. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):111–125.

- Horton R. Reviving reproductive health. Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1549.

- Horton R, Peterson HB. The rebirth of family planning. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):77.

- UN. Every woman every child. Family planning 2020; [cited 2018 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.everywomaneverychild.org/commitment/family-planning-2020/.

- Dockalova B, Lau K, Barclay H, et al. Sustainable development goals and family planning 2020. London (UK): International Planned Parenthood Federation; 2016.

- Obare F, Kabiru C, Chandra-Mouli V, et al. Family planning evidence brief – reducing early and unintended pregnancies among adolescents: WHO/RHR/17.10. Geneva: World Heath Organisation; 2017.

- Alkema L, Kantorova V, Menozzi C, et al. National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1642–1652.

- Oliver S, Stephenson J, Bailey JFactors in contraception choice and use: a synthesis of systematic reviews. PROSPERO, et al. 2017. CRD42017081521. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017081521.

- Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, et al. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–140.

- Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4: software for research synthesis. EPPI-Centre. Software. London: Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education; 2010.

- Oliver S, Rees R, Clarke-Jones L, et al. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Expect. 2008;11(1):72–84.

- Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Tackling inequalities in health: what can we learn from what has been tried? Working paper prepared for the King’s Fund International Seminar on Tackling Inequalities in Health; 1993.

- Edelman NL, de Visser RO, Mercer CH, et al. Targeting sexual health services in primary care: a systematic review of the psychosocial correlates of adverse sexual health outcomes reported in probability surveys of women of reproductive age. Prevent Med. 2015;81:345–356.

- Maravilla JC, Betts KS, Couto e Cruz C, et al. Factors influencing repeated teenage pregnancy: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):527–545.

- Ayanore MA, Pavlova M, Groot W. Unmet reproductive health needs among women in some West African countries: a systematic review of outcome measures and determinants. Reprod Health. 2016;13:5.

- Baxter S, Blank L, Guillaume L, et al. Views regarding the use of contraception amongst young people in the UK: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011;16(3):149–160.

- Brittain AW, Williams JR, Zapata LB, et al. Confidentiality in family planning services for young people a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 Suppl 1):S85–S92.

- Hoga LA, Rodolpho JR, Sato PM, et al. Adult men’s beliefs, values, attitudes and experiences regarding contraceptives: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(7-8):927–939.

- James-Hawkins L, Peters C, VanderEnde K, et al. Women’s agency and its relationship to current contraceptive use in lower- and Middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(7):843–858.

- Jonas K, Crutzen R, van den Borne B, et al. Healthcare workers’ behaviors and personal determinants associated with providing adequate sexual and reproductive healthcare services in Sub-Saharan africa: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):86.

- Pradhan R, Wynter K, Fisher J. Factors associated with pregnancy among adolescents in low-income and lower middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(9):918–214.

- Pratt R, Stephenson J, Mann S. What influences contraceptive behaviour in women who experience unintended pregnancy? A systematic review of qualitative research. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34(8):693–699.

- Tessema GA, Streak Gomersall J, Mahmood MA, et al. Factors determining quality of care in family planning services in africa: a systematic review of mixed evidence. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165627.

- Williamson L, Parkes A, Wight D, et al. Limits to modern contraceptive use among young women in developing countries: a systematic review of qualitative research. Reprod Health. 2009;6:3.

- Yakubu I, Salisu WJ. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):15.

- Ayoola AB, Nettleman M, Brewer J. Reasons for unprotected intercourse in adult women. J Womens Health. 2007;16(3):302–310.

- Black K, Lotke P, Buhling KJ, et al. A review of barriers and myths preventing the more widespread use of intrauterine contraception in nulliparous women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2012;17(5):340–350.

- Blackstone SR, Nwaozuru U, Iwelunmor J. Factors influencing contraceptive use in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2017;37(2):79–79.

- Coombe J, Harris ML, Loxton D. What qualities of long-acting reversible contraception do women perceive as desirable or undesirable? A systematic review. Sex Health. 2016;13(5):404–419.

- Vouking MZ, Evina CD, Tadenfok CN. Male involvement in family planning decision making in Sub-Saharan Africa- what the evidence suggests. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19:349.

- Wyatt KD, Anderson RT, Creedon D, et al. Women’s values in contraceptive choice: a systematic review of relevant attributes included in decision aids. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):28.

- Ackerson K, Zielinski R. Factors influencing use of family planning in women living in crisis affected areas of Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the literature. Midwifery. 2017;54:35–60.

- Askari F, Khadivzadeh T, Maleki-Saghooni N. Spousal relationship and childbearing: a review article. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2018;5(2):68–73.

- Huda FA, Robertson Y, Chowdhuri S, et al. Contraceptive practices among married women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: a review of the evidence. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):69.

- Mooney-Somers J, Lau A, Bateson D, et al. Enhancing use of emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review of women’s attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and experiences in Australia. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(2):174–195.

- Munakampe MN, Zulu JM, Michelo C. Contraception and abortion knowledge, attitudes and practices among adolescents from low and Middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):909.

- Ferreira AL, Lemos A, Figueiroa JN, et al. Effectiveness of contraceptive counselling of women following an abortion: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2009;14(1):1–9.

- Wilson A, Nirantharakumar K, Truchanowicz EG, et al. Motivational interviews to improve contraceptive use in populations at high risk of unintended pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;191:72–79.

- Halpern V, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Strategies to improve adherence and acceptability of hormonal methods of contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(10):CD004317.

- Lopez LM, Grey TW, Chen M, et al. Strategies for improving postpartum contraceptive use: evidence from non-randomized studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;27(11):CD011298.

- Dittus PJ, Michael SL, Becasen JS, et al. Parental monitoring and its associations with adolescent sexual risk behavior: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1587–e1599.

- Gavin LE, Williams JR, Rivera MI, et al. Programs to strengthen parent-adolescent communication about reproductive health: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 Suppl 1):S65–S72.

- Tolli MV. Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention, adolescent pregnancy prevention and sexual health promotion for young people: a systematic review of European studies. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(5):904–913.

- Kim CR, Free C. Recent evaluations of the peer-led approach in adolescent sexual health education: a systematic review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(3):144–151.

- Oringanje C, Meremikwu MM, Eko H, et al. Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2(2):CD005215.