ABSTRACT

Some of the earliest voice recordings of Arabic made for linguistic purposes date from World War I and were made by German authorities who recorded prisoners of war in the Halbmondlager camp outside of Berlin. This study analyzes two voice records in particular, which are labelled ‘Tripolitanisch-Arabisch (Tunesien)’ and stem from what is now southern Tunisia. This study seeks to historicise the scientific context of these voice records as well as interpret the linguistic data preserved by them in the light of Arabic dialectology. It also raises questions about the reliability of both voice recordings and printed linguistic data from the time.

1. Introduction

On March 2, 1918, a young prisoner of war named Sliman from ‘Gaṣr Mednīn’ in North Africa stood in front of a gramophone funnel in Halbmondlager, a prison camp on the outskirts of Berlin, to recite a short fairy tale. The sound of his voice was etched onto a shellac disc for future study by linguists, who, taking advantage of the numerous languages spoken by prisoners in the camp, had set up a large-scale, if impromptu, recording project. One week later, on March 9, Sliman returned to the gramophone, where he recited a list of words and numbers, likewise recorded onto a shellac disc. Sliman’s fate after these sessions is unknown. Perhaps he died somewhere in Europe, or perhaps he was able eventually to return home to Gaṣr Mednīn. But his voice has remained, imprinted within the crevices of a fragile shellac disc and stored in the cabinets of an archive in Berlin, for over a century.

2. The Lautarchiv recordings

Following the outbreak of World War 1, German linguist Wilhelm Doegen (1877-1967), had ‘the idea of using the involuntary stay of the prisoners of war held in Germany for sound recordings of speech,’ and to this end he petitioned the Prussian War Ministry, and then the Ministry of Culture and Education, to create a large-scale project (Doegen Citation1925, 9). The Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission was founded in Berlin in 1915 with this very goal, and Doegen at its head. Its task was to ‘systematically record on sound discs the languages, the music, and the sounds of all the peoples residing in German prisoner-of-war camps according to methodological principles and in relation to accompanying texts’ (Doegen Citation1925, 10).Footnote1 As the title of Doegen’s volume of studies on the recordings suggests, he envisioned pioneering a totally new kind of ethnology (‘eine neue Völkerkunde’). By the end of the war only three years later, an impressive number of recordings had been made. On the music side, Carl Stumpf (1848-1936) and his team recorded over 1,000 wax phonograph cylinders of music by 1918. In 1920, these were handed over to the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, which had itself been founded in 1900 to record the music of ‘non-European’ peoples (Ziegler Citation2006). On the spoken language side, a team of linguists under the direction of Doegen produced some 1,650 shellac discs of sound recordings between 1915 and 1918. These became the basis of the Lautabteilung of the Preußische Staatsbibliothek in Berlin and today are stored in the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Located in the village of Wünsdorf outside of Berlin, the prisoner-of-war camp known as Halbmondlager (‘Half Moon Camp’) was chosen as a particularly promising site for the work of the Phonographic Commission, as it was populated by Asian and African conscripts to colonial armies who were in German captivity. The initial purpose of gathering these disparate peoples together, in the Halbmondlager as well as in the Weinberglager in nearby Zossen, was not simply to detain them as enemy troops: the captives were to be indoctrinated through German-conceived extremist Islamic instruction with the ultimate aim of persuading them, once returned home, to rebel against their colonial rulers, be they the English in southern Asia or French in northern Africa (Höpp Citation1997).

Since prisoners in the camps spoke a number of Asian and African languages, the Phonographic Commission naturally included an ‘Orientalist’, Hubert Grimme (1864-1942). Grimme, who served as translator for Arabic-speaking prisoners, was present, in addition to Doegen, for most of the recording sessions of North African prisoners, which yielded about 100 shellac discs with texts in ‘Algerisch-Arabisch’, ‘Marokkanisch-Arabisch’, ‘Berbersprache’, ‘Maltesisch’, and other language varieties. The comparative dialectological intention of some of the recordings is clear: a number of the discs recorded in March 1918 contain the same wordlists, primarily ‘Zahlen’ and ‘Wörter’, in different varieties.Footnote2 In addition, the same speakers also provided a variety of folktales, songs, poems, and even Quran recitations. In comparison, the recordings made in 1916 largely seem to be freely chosen or spontaneously composed texts. For example, in a recording session in May 1916, Sadok Ben Rachid, a prisoner from Monastir, recited a poem of his own composition in which he recalled his experience fighting in the trenches of Europe.Footnote3

This extremely early collection of Arabic and Berber recordings, possibly the first recordings of either language ever made for linguistic purposes, however, was hardly used. Grimme contributed a chapter, entitled ‘Die Farbigen von Nordwestafrika’, on the North African recordings to Doegen’s Citation1925 ethnographic volume, focusing on what he called ‘Schützengrabenpoesie’ of Algerian and Tunisian prisoners (Grimme Citation1925). In 1928 the Arabist Hans Stumme (1864-1936), professor at Leipzig, transcribed and translated six recordings—five in Tunisian Arabic by Sadok Ben Rachid from Monastir and one in Shawi Berber by Mehiddin Ben Buzid from Algeria—for a short pamphlet published by the Lautabteilung der Preußischen Staatsbibliothek (Stumme Citation1928). While only very recently have scholars and practitioners in sound studies begun to devote attention to these materials, in particular those recorded by Sadok Ben Rachid,Footnote4 the recordings have otherwise escaped the notice of linguists of Arabic or Berber.

The present article is therefore the first to use one of the Lautarchiv recordings from North Africa for a linguistic study. But as these are recordings made in a prisoner of war camp, proper contextualisation is imperative, as is careful consideration of the research purposes to which they are put. Though they may appear to the linguist to be merely raw data, the recordings are part of an archive which is formed by and dependent on imperial power relations.Footnote5 Moreover, an awareness of just what it is that we are listening to is important. As Hoffmann has pointed out, the recorded voices of the Lautarchiv are characterised by being not only acousmatic, but also by the delocalisation of the speaker: their recited or sung material is separated, in the recorded object, from its social and epistemic contexts, thus complicating or obscuring the meaning of a recorded piece and the position of the speaker (Hoffmann Citation2015, 77–80). These recorded voices, as ‘voice-only characters in the form of archived recordings that stem from projects of colonial knowledge production’, are what Hoffmann refers to as colonial acoustic figures, or ‘colonial acousmêtres’ (ibid., 79).

Britta Lange gives three examples of ways in which these recordings can potentially be used: for linguistic purposes, as ‘documents for historicizing spoken language and for exploring how dialects were shaped and pronounced nearly one hundred years ago’; for history of science, in reconstructing how ‘science’ was used in the war and what categories and products of knowledge were relevant; and for cultural history as documents representing the perspective of the colonised serving as soldiers in European armies (Lange Citation2014, 372). The possible uses for a recording depend to some extent on the nature of that recording. The original intentions behind them mean that specific recordings (e.g. music performances, word-lists, etc.) were intended for specific areas of knowledge. Our study follows the groove of archival intentions, at least for some of the way. And while ours is a linguistic study, we do not foreclose the possible use of this and similar recordings for additional purposes, scientific, creative, or otherwise. Some prisoners, for example, composed texts which represent an important perspective on a part of history for which there is little documentation, especially not directly in the voice of colonised conscripts (Lange Citation2011; Citation2014). Bringing out these subaltern voices as part of cultural history is of great importance.

But what about the records which do not contain compositions commenting directly on the war or on imprisonment, but rather contain the productions based on and intended for traditional dialectology—such as that of Sliman? We think such recordings can make a critical contribution to Arabic dialectology, when examined with care not only as voice recordings, but as ‘sensitive documents’ and cultural-historical artefacts. The two discs recorded by Sliman are the only two from this particular region of North Africa. They represent a unique case, since there are also no contemporary linguistic studies from this region either. As what Lange refers to as ‘documents for historicizing spoken language’, that is, as linguistic data, this case can help us reconsider older sources which make claims, sometimes even without written data, about the dialects of North Africa in general and Tunisia in particular. In addition, this case can provide diachronic data which, in comparison with current data, can shed valuable light on language change over time. While we can uphold these points about the linguistic value of these early voice recordings, we also must sound a note of ambivalence. Sliman and others were coerced into recording for a European project conceived with the expressed intention to use them as nonconsensual sources for ‘modern’ linguistic analysis. But most of the records were never used for such, and have lain in the archive for more than a century, only even heard a handful of times. Is it then better, to finally make use of the recordings for that original purpose, or to leave them mostly unheard for yet another century?

3. The ‘Tripolitanisch-Arabisch (Tunesien)’ discs

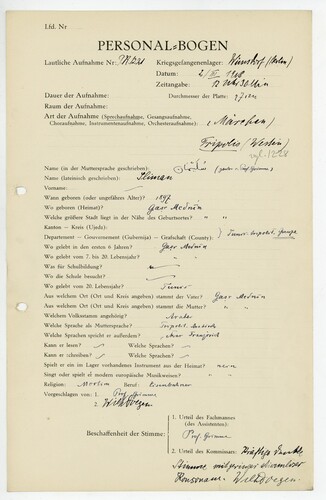

The two discs recorded by Sliman were labelled ‘Tripolitanisch-Arabisch (Tunesien)’ and numbered PK 1221 and PK 1228. The first disc, PK 1221, contains a ‘Märchen’ of 3’23” in length, and the second disc, PK 1228, contains ‘Zahlen’ and ‘Wörter’ and is recorded on both sides, totalling 3’08” in length.Footnote6 According to the accompanying Personalbögen (personal information sheets, see ) made at the time of recording and signed by Grimme and Doegen, PK 1221 was made at 12:30 on March 2, 1918 and PK 1228 exactly one week later, at 12:30 on March 9, 1918. The exact technique used to guide the speakers through the wordlists and texts is not always clear, but in some cases it is known that an assistant would whisper the words to the speaker, who would repeat them into the gramophone funnel. The Personalbogen for PK 1228 even adds a note to the entry ‘Art der Aufnahme’ (‘type of recording’): ‘vorgeflüstert von dem Fachmann’ (‘whispered out by the specialist’).Footnote7 On the other hand, PK 1221 containing the ‘Märchen’ does not have this comment, as the speaker simply seems to have recited or improvised the story in a relatively fluid manner; however, some accounts seem to indicate that the speakers practiced their texts beforehand so as to minimise errors or pauses (Scheer Citation2010, 306). In neither recording, however, can background sounds or the voices of other persons be heard. Doegen also added a comment about the quality of Sliman’s voice, describing it as a ‘kräftige dunkle Stimme mit geringer stimmloser Konsonanz’. The Personalbögen record that Sliman was born in 1897 in ‘Gaṣr Mednīn’ (an older name for today’s Medenine), to parents from the same place. The only other personal information provided is that Sliman had been living in Tunis at the age of 20, was an ‘Arab’ and ‘Muslim’, was illiterate but could speak a bit of French, and that he worked on the railroad. Geographically, the two Personalbögen give the location of ‘Gaṣr Mednīn’ as on the Tunis-Tripolitanian border, but also add a comment that the general region is ‘western Tripoli’.Footnote8 Again, the colonial acousmêtre confronts us: only the recorded voice of Sliman exists, but Sliman as a speaker and his position as a speaker are unknown, and potentially unknowable.Footnote9

Image 1. The Personalbogen (personal information sheet) for Sliman from Gaṣr Mednīn, accompanying disc PK 1221 in the Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Published with permission of the Lautarchiv.

In this section, both discs will be transcribed in their entirety and furnished with an English translation. The transcription of both discs has been divided into sections for ease of reference and translation; it should be noted that these do not represent any divisions in the audio recording itself. Likewise, the thematic labels for the transcription of the second disc have been added by us but are not present in the original audio.

3.1. Disc one: PK 1221 ‘Märchen’

Notes on the transcription and translation:

Note assimilation for wēn ṛuḥt.

A ġūl is a kind of monster or demon that forms part of the traditional folklore in many Arab societies (see Szombathy Citation2013).

The speaker starts to stay ʕAlī bin … and then corrects himself to Mḥammid Bit-Tǟžir.

The word here cannot be heard clearly.

Perhaps the speaker intended Classical farḥan šadīdan here.

For kullha, but the h is not audible.

This is not the name the speaker uses in section 9; see (iii) above.

faṛxa usually designates a ‘baby bird’, ‘a child out of wedlock’ or ‘a nasty child’. But as was confirmed by a Tunisian native speaker, it can mean ‘a young girl’ without any negative connotation in Central Tunisia; the same is true for western Libyan dialects as well.

The speaker actually says ‘She said to him’, and as such uses the masculine forms to address the man. The context, however, definitely calls for the girl being addressed.

Here the speaker actually says ‘he said to her’.

3.2. Disc two: PK 1228/1 ‘Zahlen’

3.3. Disc two: PK 1228/2 ‘Wörter’

Notes on the transcription and translation:

This word does not appear in the sources for South Tunisian dialects, but is documented in the glossary of Takrouna as ‘terrain bas et humide en cuvette qui fournit un bon pâturage; endroit où se déverse le trop plein d’un oued’ (Marçais & Guîga Citation1958-61, 3792).

gamṛa ‘moon’ seems to be out of place here and is already mentioned above within the word field ‘nature’.

In the recording tamir ‘dates’ is mentioned, seemingly out of order, after the metals.

4. Linguistic notes

In the following, the most striking phonological, morphological and syntactic peculiarities of the text and the word lists are described, and the most important lexical characteristics are noted. In and in the discussion (Section 5) these features are embedded into the Tunisian dialectal landscape and an attempt will be made to characterise and localise the speaker’s dialect in view of the existing literature on Tunisian dialects.

4.1. Phonology

Vowels: The speaker seems to rely mainly on a system of three short vowels (a, i and u), the allophones of which depend on their consonantal environment. However, in some words, clearly ә is audible. As for the long vowels, he uses ā, ǟ,Footnote10 ī, ū and the monophthongized vowels ō and ē.

Monophthongization: aw is generally monophthongized as ō; ay as ē: zōz ‘two’; fōg ‘above’; bēt ‘tent’; xēl ‘horses’; kēf ‘when; if (conjunction)’; but līl ‘night’ and ʕaynē-k ‘your eyes’.

g: gal-lu ‘he said to him’; gʕad ‘he sat, he stayed’; gaṭṭūs ‘cat’; il-gāyla ‘noon’. The only occurrences of q in the text and the word lists are tqābiḏ̣ hūw w-yā-h ‘they struggled with each other’; qahwa ‘coffee’; qudṛa ‘omnipotence’ and qasim ‘lot’, the two latter used in a religious context.

ž: žwǟd-u ‘his horse’; žā ‘he came’; mā-nnažžim-š ‘I can’t’.

Interdentals are retained: fiḏ̣ḏ̣a ‘silver’; ṯamma ‘there is’; ṯlǟṯa ‘three’; tāxuḏ-ha ‘you (m.) take her/it’; hǟḏi ‘this (f.)’.

There is no vowel change from a > i/u in the verbal and nominal pattern C1vC2C3v(C) as in the other Southern Bedouin dialects (see ). On the contrary, we have forms that are common in the urban dialects as well as in the Central Tunisian dialects: laṭx-u ‘he seized him and threw him on the ground’; šarbu ‘they drank’ and farḥu ‘they welcomed; they were happy’ (but rislit-ni ‘she/it sent me’), forms which would be lutx-a or lutux-a, širbu and firḥu in the South Tunisian dialect of Douz.Footnote11 An example of a noun is bagṛa ‘cow’ which is bugṛa in other South Tunisian dialects.

No Imāla of stressed word-final ā or a: l-ihnā ‘here’; mā, ma ‘water’; šta ‘winter’; žā ‘he came’; lga ‘he found’; ṯlǟṯa mya ‘three hundred’. This clearly distinguishes our speaker’s dialect from both the urban dialects (mǟ) and the South Tunisian Bedouin-type dialects (mē, mī).

Generally, also the word-internal Imāla is less strong than in many Tunisian dialects, e.g. wiṣfān ‘black people (pejorative)’, which would be wiṣfǟn in Tunis and in Douz, or ayyām ‘days’.

No traces of a short a in open unstressed syllables (as is for instance common in Douz): žbal ‘mountain’; nsīb-i ‘my father-in-law’; xrīf ‘autumn’; irgad ‘he fell asleep’.

The distribution of short vowels in verbs does not follow the Classical Arabic pattern but is subject to consonantal influence. Examples are the perfect forms tqābiḏ̣ hūw w-yāh ‘they struggled with each other’, ġammiḏ̣ ‘he closed (his eyes)’ (also the imperative which has exactly the same form occurs in the text); and the imperfect form mā-tfaṛṛaṭ-š ‘you (sg.m.) don’t ignore’.

An epenthetic vowel between two word final consonants is not the rule: mutt ‘I died’; bint ‘girl’; il-xubz ‘bread’; but qasim ‘lot’; samiš ‘sun’.

There are no pausal forms in the text that could be dinstinguished from their respective contextual forms; and no vowel harmony caused by the suffix -ha (fī-ha ‘in it/her’, and not fǟ-ha as for instance in Douz).

4.2. Morphology

Personal pronouns: ǟna, ana ‘I’; hūwa, hūw ‘he’.

Gender distinction with verbs in the 2.p.sg.: sǟmḥī-ni ‘excuse (f.) me’; il tḥibbi xūḏi ‘take (f.) whatever you want (f.)’.

3.p.sg.m. pronominal suffix after -(C)CC or -VC is u: ʕand-u ‘he has’; minn-u ‘from him’; ʕṭāt-u ‘she gave him’; gat-l-u ‘she said to him’, as is the case in urban and Central Tunisian dialects but contrasts to South Tunisian dialects which have -a (see ).

Change of syllable structure in fvʕl-forms to fʕvl: ḏ̣baʕ ‘hyena’; l-axšam ‘nose’; iṣ-ṣbaʕ ‘finger’; l-wḏin ‘ear’; ḏ̣fiṛ ‘finger nail’. As in Tunisia’s sedentary varieties this resyllabification does not happen in all fvʕl-forms, as the examples bint ‘girl’; xubz ‘bread’; samiš ‘sun’; ṯalž ‘snow’; kalb ‘dog’; gamaḥ ‘wheat’; xamir ‘alcohol’; wižah ‘face’ show, where the ‘original’ structure remains dominant.Footnote12

3.p.sg.f. of verbs in the perfect is -it and as such conforms to the sedentary varieties as well as to many Tunisian Bedouin-type varieties: žǟbit-ni ‘she brought me’; rislit-ni ‘it/she sent me’.

Perfect 3.p.sg.f. in combination with a vocalic suffix shows a long -ā: ʕṭāt-u ‘she gave him’; žǟt-u ‘she came to him’; xaṛṛžǟt-u ‘she brought him out’. This is characteristic of all Bedouin-type dialects in Tunisia known so far.

Perfect 3.p.pl. of III-weak verbs is -ū: žū ‘they came’; mšū ‘they went’ (as opposed to žǟw in sedentary dialects and žaw in the dialect of Douz).

The irregular verb ‘to take’ is formed with a long ā: tāxuḏ-ha ‘you (sg.m.) take her/it’, and as such conforms with the sedentary as well as the South Tunisian-Bedouin varieties. But it contradicts our findings for the Central Tunisian dialects where we have yōxuḏ ‘to take’ and yōkul ‘to eat’.

Conjunctions: bǟš ‘so that, in order to’; kēf ‘when; if’; lamkín ‘but’.

Interrogative pronouns and adverbs: wēn-hum? ‘where are they?’; ǟš ‘what?’.

Demonstrative pronoun: hǟḏi ‘this (f.)’.

Relative pronoun illi, il: il tḥibbi xūḏi ‘Take (sg.f.) whatever you want (f.)!’; rǟ-hi qudrit Aḷḷāh illi rislit-ni bǟš inṭallʕ-ik ‘It was God’s omnipotence that sent me to bring you out’.

Future marker maš and intention marker tawwa: xallī-ni maš nurgud ‘Let me sleep!’; tawwa yžū ‘they will come’.

Negation: mā-taʕraf-ši? ‘don’t you (sg.m.) know?’; mā-nnažžim-š ‘I can’t’; mā-naʕraf-hā-š ‘I don’t know her/it’; mā-nḥibb ḥatt šayy ‘I don’t want anything at all’.

There is no genitive marker in the text, and no passive verb forms.

4.3. Syntax

Indefinite specifying article: wāḥid is-srāya ‘a multi-storey house’, waḥd it-tǟžir ‘a merchant’, waḥd il-faṛxa ‘a young girl’; wāḥid il-bīr ‘a well’. This is another remarkable feature of Sliman’s speech, as it is so far not attested in Tunisian dialects. In most Tunisian varieties, indefinite nouns simply occur without the definite article; constructions like wāḥid fṛanṣāwi imply a specific indefinite ‘a certain French man’, and the noun has no article.Footnote13 Although texts of the TUNOCENT-corpus which could provide counterevidence have not been transcribed yet, the project collaborators from Central Tunisia confirmed that they were unaware of constructions like wāḥid il-bīr. They are, however, found in Morocco and also in (the Western part of) Algeria.Footnote14 Constructions comparable to wāḥid + article + noun in Sliman’s text are šwayya l-mā ‘some water’, and yā l-bint ‘oh girl’, both usually found without the definite article in Tunisian dialects.

4.4. Lexis

Among the characteristic lexical items used by Sliman are the following: ṯamma ‘there is’; l-ihnā ‘here’; yǟsir ‘very; a lot’; ṛāḥ - yṛūḥ ‘to go (off)’; yḥawwis ʕa-l-mā ‘to search for water’; samiš ‘sun’; naww ‘rain’; bēḏ̣a ‘egg’; žwǟd ‘horse’; faṛxa ‘young girl’. Whereas the existential marker ṯamma is typically found in all of Tunisia, and the adverb yǟsir and the noun naww are commonly found in Tunisian Bedouin-type dialects, faṛxa with the meaning ‘young girl’ seems to be restricted to Central Tunisian dialects. Some of the other lexical items seem to be more common in Algeria (see Section 5). Finally, there are no French loanwords in the text.

5. Dialectological analysis

The retention of interdentals and the use of ž described in Section 4.1 are almost pan-Tunisian phonological phenomena common in both sedentary and Bedouin-type dialects. The voiced realisation of q as g, gender distinction with verbs, the conjugation of III-weak verbs (žū as opposed to žǟw in sedentary dialects) and the lengthening of the short vowel of the perfect 3.p.sg.f. in combination with a vocalic suffix (ʕṭāt-u ‘she gave him’), even the adverb yǟsir ‘very’, clearly mark the dialect under investigation here as of the type traditionally called ‘Bedouin’ within the dialectal landscape of Tunisia.

For discussion of isoglosses separating the two major groups of Bedouin-type dialects known so far in Tunisia, the starting point is usually W. Marçais’ 1950 article where he divides the Tunisian Bedouin dialects into Hilāli and Sulaymi subgroups.Footnote15 Though this study has some problems, due to its scarce linguistic data and possibly misleading categorizations, to a certain degree, it may indicate what the dialectal landscape of Tunisia might have looked like approximately in the colonial period.Footnote16 On the basis of what W. Marçais proposes, the Medenine region would be located among the so-called ‘Sulaymi’ dialects that cover all of Southern Tunisia. In W. Marçais’ description, the ‘Sulaymi’ dialects are also spoken by the tribes along the eastern coastline, and in northern Tunisia between the Medjerda River and the Mediterranean Sea. He lists the tribes in these areas as follows: ‘les Ouerghemma, les Marâzîg et les gens du Nefzâoua, les ‘Akkâra, les Hamârna, les Benî Zîd, les oasis de la région de Gabès, les Mhâdhba, les ‘Agârba, les Neffât, les Mthâlîth, les Souâsi, les Oulâd Sa‘îd, les Hdîl, les Mog‘od et les groupes humains de la Kroumirie’ (Marçais Citation1950, 214).Footnote17 Of these, the Medenine area would be occupied by the Ouerghemma confederation, as a map from the middle of the 19th century shows, and to be even more precise, by the Touazine tribe.Footnote18

If we assume that the information provided by Marçais is accurate, then the dialect of Medenine in the first half of the 20th century would be a ‘Sulaymi’-type dialect. However, one of the main issues with Marçais’ classification of Tunisian dialects is that he provides very little data to demonstrate them, indeed sometimes no data at all, making it difficult on linguistic grounds to accept their validity. But before dealing with these issues in more detail, let us examine what is known about the dialects of southern Tunisia first.

Though there is no publication concerned with the dialect of Medenine itself, we have sufficient knowledge of the varieties spoken in the proximity of Medenine (shown in and ) in essentially all the cardinal directions.

Map 1. Dialects of southern Tunisia for which studies or data have been published (in black circles).

Table 1. Studies on Arabic dialects of southern Tunisia.

These studies vary in the linguistic domains and amount of material presented; some present only transcribed texts while others provide linguistic analysis but mostly in the domains of phonology or morphology. Regarding the potential relationships between these different dialects, Behnstedt (Citation1998, 53f.) mentions some Arabic-speaking groups on the island of Djerba who originate from Medenine or its environs, while P. Marçais and Viré characterise the dialect of a member of the Mahāḏba tribe in the region of Skhira and Mezzouna as close to the dialects spoken in Gabis, Gafsa, and by the Nefzaoua tribe (Marçais and Viré Citation1981, 369).

As shown in , all of these dialects are quite consistent in the use of certain features which can be considered as isoglosses for this group. Among them is the vowel change from a > i/u in the verbal and nominal pattern C1vC2C3v(C) (bugṛa ‘cow’ vs. bagṛa), the suffix of the 3p.sg.m. being -a (dāṛ-a ‘his house’ vs. dāṛ-u) and the imāla of final ā that is realised as ē or even ī (mē, mī ‘water’ vs. mǟ, mā). As lexical isoglosses we include the verbs ‘to go’ and ‘to search for’.

Table 2. Selected isoglosses for southern Tunisian dialects.

As is shown in , the features attested for the dialects surrounding Medenine mostly do not agree with those used by Sliman. He uses forms that are widespread in central and northwestern Tunisia, but not in southern Tunisia around the region of Medenine. The phonological and morphological features used by Sliman seem to be more of the so-called Tunisian Hilāli dialects (H-dialects) that are spoken in Central Tunisia, at least within W. Marçais’ categorisation.Footnote19 Sliman uses these forms consistently throughout the recordings, and does not give the impression of pretending to speak another dialect than he actually does. The contemporary linguistic data collected during the TUNOCENT-project in the past few years provides useful comparanda. It shows only bagṛa for the governorates of Kef, Siliana, Kasserine, and Sidi Bouzid, no final imala for the adverb l-ihnā, l-ihna ‘here’ and only -u as suffix for the 3.p.sg.m. in the verb rīt-u or šuft-u ‘I saw him/it’. The future marker maš (miš) on the other hand, is frequent not only in southeastern TunisiaFootnote20 but is also widespread in the governorates of Beja, Jendouba, Kef, Siliana, Kasserine, and Sidi Bouzid.Footnote21

On the lexical level the verb yḥawwis with the meaning ‘to search for’ is not attested in the larger Medenine area, where it means ‘to go for a walk, to go on vacation’. However, we find the verb yḥawwis with the meaning ‘to look for’ documented for Algeria (Behnstedt & Woidich Citation2014, Map 346) and it occurs also in our TUNOCENT data for the governorate of Gafsa. ṛāḥ - yṛūḥ ‘to go, to leave’ is only rarely attested in the TUNOCENT data where primarily the imperative aṛṛāḥ occurs, but perhaps it was more common in Sliman’s time, as the entry ṛāḥ - yrūḥ ‘partir; s’en aller’ in Marçais and Farès’ glossary of the Ḥāmma dialect shows (Citation1931-1933, 230). Additionally, the use of bēḏ̣a for ‘egg’ is very uncommon for Tunisia as a whole (and within the data for the TUNOCENT-project bēḏ̣a for ‘egg’ is not documented at all), but has also been documented for Algeria (Behnstedt and Woidich Citation2012, Map 245).

The use of ǟna and of yāxuḏ is unclear. ǟna is usually considered as urban form (though we also find it in our data in many locations within the governorate of Gafsa), used among others in Tunis, whereas in Central Tunisian dialects forms like nǟ, nǟy and nǟya are used. In the South Tunisian dialects the realisation of the verbs ‘to take’ and ‘to eat’ is yāxuḏ and yākul as opposed to yōxuḏ and yōkul in Central Tunisian dialects. Finally, as far as syntax is concerned, the use of an indefinite article (e.g. wāḥid il-bīr ‘a well’), attested only for Moroccan and Algerian dialects, leaves us with another big question mark.

After comparing with the existing data for central and southern Tunisian dialects, it seems that the dialect of Sliman points unexpectedly towards the regions of northern Gafsa, Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine, Kef, and Siliana, that is, towards Tunisia’s central and northwestern dialects, and, especially on the lexical and syntactic level, even Algerian dialects. What to make of this conclusion?

If we assume that the linguistic situation according to W. Marçais was actually the case in the early 20th century and that Sliman’s dialect was representative of Medenine at the time, then his recordings contradict the expectation that Medenine would have a ‘Sulaymi’-type dialect, or to put it more generally, that the dialect of Medenine would be roughly similar to that of its neighbours. But if W. Marçais was only making conjectures about certain regions, and he did not have complete data, then we have no comparative information about the dialect of Medenine in the early 20th century, and we cannot say whether or not Sliman’s dialect is representative of Medenine’s dialect at the time. This latter case leads to more open possibilities, which cannot be proven: perhaps Medenine centre itself had a different dialect than the surrounding rural areas; or perhaps different social groups, such as tribes, had different dialects. Of course, another possibility is that Sliman’s place of origin was not recorded correctly by the Halbmondlager authorities—but other studies have shown successfully that these places of origin, including some in Tunisia, seem to be quite accurate (Kropotkine Citation2021). And in any case, we do not have any information about Sliman’s tribal affiliation.

There are additional possibilities worth exploring, though. Perhaps Sliman’s original dialect changed for some reason, such as living or working in another region of Tunisia. Although we know next to nothing about his life before his internment in Germany, the Personalbögen give his profession as ‘Eisenbahner’ (railroad worker). This may be significant, as there was never a railroad in Medenine; railways were concentrated in northeastern Tunisia and the farthest south they extended in the 1910s was Gafsa, only reaching Gabes and Tozeur, and not any further south, after 1930 (Brant Citation1971, 97–136). As a railroad worker, Sliman is likely to have spent time all over Tunisia and thus may have adjusted his dialect to accommodate to more central or northern Tunisian Arabic features. But, Sliman was only about 21 at the time of the recordings; he may not have spent a long period of time in other regions than Medenine, and even though it seems that he stayed in Tunis for a year at least before his internment, his dialect features do not really point towards the dialect of the city of Tunis.

It could also be the case that Sliman adjusted his dialect during his conscripted service in the French army, or his stay of indeterminate length in the Halbmondlager, where he would have interacted with speakers of numerous Algerian and Tunisian dialects. Even though this scenario is possible, one might expect a kind of partial accommodation to these other dialects and a fair amount of variation, but the linguistic features in Sliman’s speech are rather stable and consistent. Likewise, one might expect that when relating a traditional piece of oral literature, one would do so in one’s original dialect, but we cannot necessarily make this assumption for every speaker. At the same time, we might also question the pronunciation or variety used by the specialist who prompted Sliman as he recited the wordlists, or the scholar who may have helped him write and practice his tale, if this latter situation did occur. About either of these possibilities we have no information. The data provided by Sliman may therefore show a kind of idiolect that has accommodated to various features of other dialects, rather than an ‘authentic’ Medenine dialect. Indeed, given the paucity of early dialectological sources and their at times questionable reliability, we may never be able to judge this matter adequately.

6. Conclusions

In sum, this voice recording from 1918—one of a group of the earliest voice recordings of Arabic dialects in existence—presents us with valuable data. But this data is far from straightforward. Even though we are able to show how Sliman’s speech, at least as it was at one point in time, differs from later data on nearby dialects of southern Tunisia, we are still left with many open questions.

Despite the obvious advantages of sound recordings over written data, this record shows that they do not provide easy-to-use, reliable snapshots back in time. They cannot be considered without social and historical context. Indeed even with what can be found of relevant context, our analysis has become more, rather than less, complicated. Further work using materials from the Lautarchiv for linguistic purposes must therefore also historicise the recordings and the data they contain, rather than taking them at face value.

The difficulties in analyzing this voice recording also suggest that written sources from the time, where we are additional steps removed from firsthand linguistic data—lacking information about the speakers who were consulted and their social contexts, (and in some cases lacking even substantial transcribed material)—may have similar complications and problems. Likewise, we should continue to rely on those early written sources likewise only with appropriate historicization.

Acknowledgements

The digital files for the two records discussed here were kindly made available by the Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. We are grateful to the Lautarchiv for permission to use the records for this study and to publish images of the Personalbögen. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for helpful remarks and the suggestion of useful additional resources.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For more on the founding and general activities of the Phonographische Kommission and the history of the Lautarchiv see Mehnert Citation1996 and Lange Citation2017. For more on recordings in the camps, see Scheer Citation2010, esp. 302-308.

2 On the dialectological motivation behind the recordings, see Lechleitner Citation2010.

3 The paperwork accompanying his recordings transcribes his name Sãdåk Berrĕʃid. For a discusssion of this poem, see Lange Citation2014; Lange Citation2019, 237–253. The recording is available online at https://www.lautarchiv.hu-berlin.de/bestaende-und-katalog/beispiele/phonographische-kommission-kriegsgedichte/.

4 See the works of Britta Lange cited above. On the effort to track down the life story of Sadok Ben Rachid and to repatriate the recordings of him to his place of origin in Monastir, see Kropotkine Citation2021.

5 See Hoffmann Citation2015, and especially Hoffmann and Mnyaka Citation2015, 141–146 for discussion of the organizing logic of these kinds of archives.

6 Information about each disc can be accessed through the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin’s online Wissenschaftliche Sammlungen catalog (https://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de/objekte/lautarchiv/): PK 1221 at http://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de/dokumente/13797/, PK 1228/1 at http://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de/dokumente/13808/, and PK 1228/2 at http://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de/dokumente/13809/.

7 The procedure and setup for the recording sessions can be seen in one known image depicting the process, see Scheer Citation2010, 305 Fig. 1.

8 The use of the term “Tripolitanisch” (Tripolitanian) reflects the somewhat ambiguous status of what is now southern Tunisia in the eyes of Europeans at that time. While the region was contested between the rulers of Tunis, Tripoli, and the Ottomans, it was home to nomadic groups which moved easily between there and what is now western Libya. It had not yet become totally colonized by Italy, and the border separating Italian Tripolitania from the French protectorate of Tunisia was not yet solidified. This is also reflected in other works at the time, for example, the study of Stumme (Citation1894) on oral literature from Maṭmāṭa, also in today’s southern Tunisia, is titled Tripolitanisch-tunisische Beduinenlieder.

9 The case of Sliman can be contrasted, to some extent, with that of Sadok Ben Rachid mentioned above, about whom a fair amount is now known. Hoffmann and Mnyaka Citation2015 are similarly faced with limitations on knowing recorded subjects in their study of an isiXhosa speaker recorded in the Lautarchiv.

10 The phonemic status of ǟ in Tunisian dialects is not clear. Still it is part of the transcription system here, as it differs fundamentally from ā.

11 Cf. Boris Citation1958, 552; 457 where the t in lutux-a is not emphatic. For the vowel change in general see Ritt-Benmimoun Citation2014a, 60–62.

12 For more information on this change in syllabic structure see Singer Citation1984, 165f., 501f. for the urban variety of Tunis and Ritt-Benmimoun Citation2014a, 231 for the Bedouin-type variety of Douz.

13 Cf. Singer Citation1984, 282 for Tunis, and Ritt-Benmimoun Citation2014a, 102 for Douz.

14 For Morocco see Aguadé Citation2009: “The specifying article wāḥǝd (sometimes wāḥ) is also invariable and precedes the definite substantive: wāḥǝd lbǝnt ‘a girl’”. See also Guerrero (Citation2014, 228) for the dialect of Oran.

15 In fact, W. Marçais was the first to use the term “Sulaymi” to designate a dialect type (Benkato Citation2019, 8–12).

16 For a critique of mostly French dialectology of Arabic and its problematic use of dialect categories, see Benkato Citation2019.

17 For some update to Marçais’ comments, see also Ritt-Benmimoun Citation2014b.

18 For the Ouerghemma, see Fig. 15 in al-Ḥabbāšī Citation2017, 132; for the Touazine see Louis Citation1979, 16; and the map in Despois Citation1950, 137. The Ouerghemma’s area, including Medenine, is also described in a pamphlet on the location of tribes in colonial Tunisia (Secrétariat général du gouvernement tunisien Citation1900, 286-297); this is perhaps one of the sources of Marçais’ statements about tribal distribution. According to Martel (Citation1965, 98) the Ouerghemma had approximately 15,000 members between 1884 and 1887.

19 According to W. Marçais (Citation1950, 211, 214) Group H comprises the dialects spoken in Central Tunisia, extending from north of the region of the Chotts to the Medjerda River in Northern Tunisia; see also Ritt-Benmimoun Citation2014b.

20 E.g. Singer Citation1980, 271, māš among the Mahāḏba, see Marçais and Viré Citation1981, 373.

21 Data from the TUNOCENT-project.

22 Singer (Citation1996, 31) states that some of the speaker’s inconsistencies are due to influence from Standard Arabic and the urban Tunisian varieties.

References

- Aguadé, Jorge. 2009. “Morocco.” In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, edited by Lutz Edzard, and Rudolf de Jong, 287–297. Leiden: Brill.

- Behnstedt, Peter. 1998. “Zum Arabischen von Djerba (Tunesien) I.” Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik 35: 52–83.

- Behnstedt, Peter. 1999. “Zum Arabischen von Djerba (Tunesien) II: Texte.” Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik 36: 32–65.

- Behnstedt, Peter, and Manfred Woidich. 2011-2021. Wortatlas der arabischen Dialekte. Band I: Mensch, Natur, Fauna und Flora. Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2011; Band II: Materielle Kultur. Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2012; Band III: Verben, Adjektive, Zeit und Zahlen. Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2014; Band IV: Funktionswörter, Adverbien, Phraseologisches: eine Auswahl. Leiden-Bosten: Brill, 2021 (Handbook of Oriental Studies, Section one: The Near and Middle East, 100).

- Benkato, Adam. 2019. “From Medieval Tribes to Modern Dialects: On the Afterlives of Colonial Knowledge in Arabic Dialectology.” Philological Encounters 4: 2–25.

- Bin Murād, Ibrāhīm. 1999. al-Kalima al-ʔaʕǧamīya fī ʕarabīyat nifzāwa (bi-l-ǧanūb al-ġarbī at-tūnisī). Tunis: Markaz al-dirāsāt wa-l-buḥūṯ al-iqtiṣādiyya wa-l-iǧtimāʿiyya.

- Boris, Gilbert. 1951. Documents linguistiques et ethnographiques sur une région du sud tunisien (Nefzaoua). Paris: Maisonneuve.

- Boris, Gilbert. 1958. Lexique du parler arabe des Marazig. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Librairie G. Klincksieck.

- Bouaicha, Mouldi. 1993. Le parler de Zarzis. Etude descriptive d’un parler arabe du Sud Est tunisien. Thèse pour le doctorat de linguistique. Université René Descartes. Paris.

- Brant, E. D. 1971. Railways of North Africa. The Railway System of the Maghreb: Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco and Libya. London: David & Charles.

- Cantineau, Jean. 1951. “Analyse phonologique du parler arabe d’El-Ḥâmma de Gabès.” Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 47: 64–105.

- Despois, M. J. 1950. “Les Tunisiens.” In Initiation à la Tunisie, edited by A. Basset, 135–148. Paris: Librairie d'Amérique et d'Orient, Adrien Maisonneuve.

- Doegen, Wilhelm. 1925. “Einleitung.” In Unter fremden Völkern: Eine neue Völkerkunde, edited by Wilhelm Doegen, 9–17. Berlin: Stollberg.

- Grimme, Hubert. 1925. “Die Farbigen von Nordwestafrika.” In Unter fremden Völkern: Eine neue Völkerkunde, edited by Wilhelm Doegen, 40–64. Berlin: Stollberg.

- Guerrero, Jairo. 2014. “Preliminary Notes on the Current Arabic Dialect of Oran (Western Algeria).” Romano-Arabica: Arabic Linguistics 15: 219–233.

- al-Ḥabbāšī, Muḥammad ʕAlī. 2017. ʕUrūš tūnis. 3rd ed. Tunis: Manšūrāt Sūtīmīdiya.

- Hoffmann, Anette. 2015. “Introduction: listening to sound archives.” Social Dynamics 41 (1): 73–83.

- Hoffmann, Anette, and Phindezwa Mnyaka. 2015. “Hearing voices in the archive.” Social Dynamics 41 (1): 140–165.

- Höpp, Gerhard. 1997. Muslime in der Mark: Als Kriegsgefangene und lnternierte in Wünsdorf und Zossen, 1914-1924. Berlin: Zentrum Moderner Orient.

- Kropotkine, Anne. 2021. La chanson de Sadok: Du camp de Zossen-Wünsdorf à Monastir, le cheminement d’un voix (1916-2020). Rennes: Éditions Goater.

- Lange, Britta. 2011. “South Asian Soldiers and German Academics: Anthropological, Linguistic and Musicological Field Studies in Prison Camps.” In “When the War Began, We Heard of Several Kings:” South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, edited by Ravi Ahuja, Heike Liebau, and Franziska Roy, 149-184. New Delhi: Social Science Press.

- Lange, Britta. 2014. “History and Emotion: The Potentiality of Laments for Historiography.” In The World during the First World War, edited by Helmut Bley, and Anorthe Kremers, 371–376. Essen: klartext.

- Lange, Britta. 2017. “Archive, Collection, Museum: On the History of the Archiving of Voices at the Sound Archive of the Humboldt University.” Journal of Sonic Studies 13, Online: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/326465/326466/0/28.

- Lange, Britta. 2019. Gefangene Stimmen: Tonaufnahmen von Kriegsgefangenen aus dem Lautarchiv 1915-1918. Berlin: Kadmos.

- Lechleitner, Gerda. 2010. “ … den lebendigen Klang der Mundart hören … ’: Dialektologie als Impulsgeber in der Anfangszeit des Phonogrammarchivs.” In Fokus Dialekt: Analysieren – Dokumentieren – Kommunizieren: Festschrift für Ingeborg Geyer zum 60. Geburtstag, edited by Hubert Bergmann, Manfred Michael Glauninger, Stefan Winterstein, and Eveline Wandl-Vogt, 251–262. Hildesheim: Georg Olms.

- Louis, André. 1979. Nomades d’hier et d’aujourd’hui dans le Sud tunisien. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud.

- Marçais, William. 1950. “Les parlers arabes.” In Initiation à la Tunisie, edited by A. Basset, 195–219. Paris: Maisonneuve.

- Marçais, William & Jelloûli Farès. 1931-1933. “Trois textes arabes d’el-Ḥâmma de Gabès.” Journal Asiatique 218 (1931), 193-247; 221 (1932), 193-270; 223 (1933), 1-88.

- Marçais, William, and Abderrahmân Guîga. 1958-61. Textes arabes de Takroûna. II. Glossaire. 8 vol. Paris: Geuthner.

- Marçais, Philippe, and F. Viré. 1981. “Gazelles et outardes en Tunisie: reportage en parler arabe de la tribu des Mahâdhba.” Arabica 28 (2-3): 369–387.

- Martel, André. 1965. Les confins saharo-tripolitains de la Tunisie (1881-1911). 2 vols. Paris: Presse Universitaires de France.

- Mehnert, Dieter. 1996. “Historische Schallaufnahmen: Das Lautarchiv an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.” In Studientexte zur Sprachkommunikation: Tagungsband der siebenten Konferenz Elektronische Sprachsignalverarbeitung, edited by Dieter Mehnert, 28–45. Dresden: TUD press.

- Ritt-Benmimoun, Veronika. 2011. Texte im arabischen Beduinendialekt der Region Douz (Südtunesien). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz (Semitica Viva 49).

- Ritt-Benmimoun, Veronika. 2013. “Giftiges aus Gafṣa. Ein Text im arabischen Beduinendialekt von Bil-Xēr (Gafṣa).” In Nicht nur mit Engelszungen. Beiträge zur semitischen Dialektologie. Festschrift für Werner Arnold zum 60, edited by R. Kuty, U. Seeger, and S. Talay, 289–300. Wiesbaden: Geburtstag.

- Ritt-Benmimoun, Veronika. 2014a. Grammatik des arabischen Beduinendialekts der Region Douz (Südtunesien). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz (Semitica Viva 53).

- Ritt-Benmimoun, Veronika. 2014b. “The Tunisian Hilāl and Sulaym Dialects: A Preliminary Comparative Study.” In Alf lahǧa wa lahǧa. Proceedings of the 9th Aida Conference, edited by O. Durand, A. D. Langone, and G. Mion, 351–359. Wien-Münster: LIT-Verlag.

- Scheer, Monique. 2010. “Captive Voices: Phonographic Recordings in the German and Austrian Prisoner-of-War Camps of World War I.” In Doing Anthropology in Wartime and War Zones: World War I and the Cultural Sciences in Europe, edited by Reinhard Johler, Christian Marchetti, and Monique Scheer, 279–309. Bielefeld: transcript verlag.

- Secrétariat général du gouvernment tunisien. . 1900. Nomenclature et répartition des tribus de Tunisie. Chalon-sur-Saone: Imprimerie française et orientale E. Bertrand.

- Singer, Hans-Rudolf. 1980. “Das Westarabische oder Maghribinische.” In Handbuch der arabischen Dialekte, edited by O. Jastrow, and W. Fischer, 249–291. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Singer, Hans-Rudolf. 1984. Grammatik der Arabischen Mundart der Medina von Tunis. Berlin-New York: de Gruyter.

- Singer, Hans-Rudolf. 1996. “Ein arabischer Text aus Ṭaṭawîn.” In Romania Arabica. Festschrift für Reinhold Kontzi zum 70, edited by J. Lüdtke, 31–36. Tübingen: Geburtstag.

- Skik, Hichem. 1969. “Description phonologique du parler arabe de Gabès (Tunisie).” Travaux de Phonologie. Cahier du C.E.R.E.S., Série Linguistique 2: 83–114.

- Stumme, Hans. 1894. Tripolitanisch-tunisische Beduinenlieder. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung.

- Stumme, Hans. 1928. Arabische und berberische Dialekte (Lautbibliothek, Phonetische Platten und Umschriften 45), ed. Lautabteilung der Preußischen Staatsbibliothek. Berlin.

- Szombathy, Zoltan. 2013. “Ghūl.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson, 144–146. Leiden: Brill.

- Ziegler, Susanne. 2006. Die Wachszylinder des Berliner Phonogramm-Archivs (Veröffentlichungen des Ethnologischen Museums Berlin 73). Berlin.

- https://tunico.acdh.oeaw.ac.at/dictionary.html