ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the extreme hardship suffered by migrants crossing through Libya to reach Italy and Europe. The paper documents and defines the notion of extreme hardship and argues in favour of an ethics of care that provides for protection for those migrants who may not be asylum seekers for what concerns their initial motivation for migrating but who need humanitarian protection because of the harm suffered while en route. Starting with a normative exploration of how an ethics of care can and should inform the policy of countries of arrival, this paper analyses the specific case of Italy and the emerging case law and legal practice in relation to the humanitarian stay permits. Based on the analysis of relevant scholarly literature, policy and legal texts and interviews with expert informants (lawyers and judges) and taking stock of an innovative practice that emerged in Italy in the period 2015–2020, the paper also discusses similar provisions in other European countries and argues for the possibility to develop and codify a humanitarian permit, at national or also European level.

1. Introduction

In March 2023, the report of the latest UN Independent Fact-Finding Mission on Libya states:

”The Mission has found reasonable grounds to believe that crimes against humanity were committed against Libyans and migrants throughout Libya in the context of deprivation of liberty. Notably, the Mission documented and made findings on numerous cases of, inter alia, arbitrary detention, murder, torture, rape, enslavement, sexual slavery, extrajudicial killing and enforced disappearance, confirming their widespread practice in Libya.”

The conditions in Libya for migrants are increasingly well known, however, how to deal with migrants arriving from such a context in safe third countries has been a significant policy challenge. This paper explores the ways in which Italy has used its humanitarian permit provision during the period 2015–2020 to provide protection for people who did not qualify for asylum but who had faced extreme hardship while in transit through Libya. The paper puts the Italian case study in comparative perspective discussing similar practices in other European countries.

Italy has been at the forefront of migrants arriving via Libya over the past decade. In Italy annual arrivals remained above 150,000 in the period 2014–2016 and only receded in 2017 to 120,000 after the Italian government engaged with Libyan authorities to reduce departures from the Libyan coast. Since 2018, arrivals in Italy through the Central Mediterranean route have been lower ranging between 23,370 (2018) and 34,154 (2020): the pandemic of COVID-19 had a significant impact on patterns of mobility along the routes to and through North Africa (UNHCR, Citation2021). However irregular movements re-emerged in early 2021 with 67,040 which have reached almost 115,000 in the first eight months of 2023 (Ministero dell’Interno, Citation2023).

What remains particularly salient in the case of crossings from Libya to Italy is the hardship that people have gone through while in transit: focusing on the arrivals by the Central Mediterranean route, migrants and asylum seekers face uncertainty and violence already at beginning of the route back in Niger (Yuen, Citation2019) or in Sudan (Kuschminder, Citation2020). As documented by the UN, migrants arriving in Italy have faced violence, abuse, kidnapping and extortion, and outright torture en route in Libya that amount to crimes against humanity (Kuschminder & Triandafyllidou, Citation2020).

However, once in Italy, the majority of these migrants do not qualify for refugee protection. In this paper, we do not consider the complexities and reasons of leaving nor if the decision to leave was forced or voluntary, or somewhere in between (Crawley & Skleparis, Citation2018; Erdal & Oeppen, Citation2018; Jubilut & Martins, Citation2019). While many of these migrants do not qualify for asylum as their main motivation for leaving their country of origin has been the search for a better future rather than the search for international protection, we argue that the hardship and mental/physical damage suffered in Libya makes individuals eligible for a humanitarian permit, on the basis of ethics of care considerations. Building on our fieldwork in Italy and the implementation of the permit for humanitarian reasons there in the period 2015–2019 and again since 2020, we analyse the socio-legal reasoning behind it and how it actually constructs a notion of relational care, which could be used as the basis for creating a European humanitarian stay permit, providing protection to those migrants who have suffered significant moral and physical harm while in transit.

This paper thus focuses on the analytical and policy question of what kind of protection should be afforded to migrants who have faced such extreme hardship and abuse when they arrive at a safe third country. The ‘politics of bounding’ – the process by which categories are constructed, their purposes and consequences – has great power within the migration-asylum nexus (Crawley & Skleparis, Citation2018). Increasingly, there is a misalignment between legal and normative frameworks that afford protection with contemporary forms of migration (Zetter, Citation2015). This is reflected in the growing literature that recognizes the inadequacies of the categorical boundaries of refugee and migrant, highlighting the need for more space between these categories (Crawley & Skleparis, Citation2018; Jubilut & Martins, Citation2019).

Despite this recognition, there is a gap in the literature on potential solutions upon arrival in a safe third country for those in need of assistance, such as from experiences of extreme hardship, but excluded from asylum processes. There is an increasing body of literature on alternatives for return for those refused by the asylum system, on ‘sanctuary cities’ and local solutions to irregular migration (see Spencer, Citation2022), but there is a gap in how policy makers could normatively and legitimately provide statuses and protection to new categories of migrants. Naturally, we acknowledge that the onus of responsibility for the hardship that many migrants suffer and for which we argue an ethics of care is required, partially lies with Europe. While Europe is not itself the perpetrator of this extreme hardship, Italy and the EU have been complicit in actively funding the Libya coast guard to return migrants to Libya, in criminalizing actors engaged in search and rescue in the Mediterranean, and in refusing disembarkation to migrants (see for example: Mainwaring & Debono, Citation2021). The IOM reported 32,425 people were returned to Libya by the coast guard in 2021 (IOM, Citation2022) and in October 2021, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights found in a fact-finding mission that the ‘acts of murder, torture, imprisonment, rape and enforced disappearance perpetrated in Libya’s prisons may amount to crimes against humanity’ (OHCHR, Citation2023). The EU has been silent and inactive on these issues, continuing to fund the return of migrants to such conditions. Recently other authors have underlined the contradiction by discussing the legal responsibilities on search and rescue under international law as an ethics of care (notably the extent to which they are able and willing to care for those at grave risk) (Mann & Mourão Permoser, Citation2022; Mcdowell, Citation2022). They note though that such legal and moral frameworks collide with wider geopolitical considerations turning eventually migrants into collateral damage (Mcdowell, Citation2022).

How to reconcile the contradiction of arguing for protection for migrants experiencing extreme hardship that arrive in Europe, when the EU itself is funding external action to prevent their arrival that places them in such conditions of extreme hardship? It is not the first time that policies contradict each other, and in this case, we argue that once in the EU and entering asylum processes in EU member states there is an accountability to due process of the asylum and refugee system for arrivals to Europe. It is within this process that we therefore focus in this article on how to manage cases of extreme hardship of migrants arriving in the EU. We recognize the contradiction of this process with external action, however, it is not the focus of this article to reconcile these two oppositional branches of EU policy.

This paper seeks to make three important contributions. First, to present a socio-legal analysis of the development and implementation of the Italian humanitarian permit from 2015 to 2020 and point to its special features notably of considering the notion of hardship in transit. Second, to put the Italian experience into a comparative perspective. Third, inspired by the Italian case study, the paper puts forward suggestions for codifying the right to humanitarian protection at the EU level in destination countries for those who suffer extreme hardship while in transit.

This paper is particularly timely after the Italian election of September 2022 which has brought to power a far right government that promised to close the sea borders with Libya, has reduced avenues for protection but at the same time have found itself unable to stem the flow of migrants and asylum seekers across the Mediterranean shores.

2. Documenting and defining extreme hardship

Recent research has demonstrated the extreme hardship that asylum seekers and other migrants experience in Libya (Kirby, Citation2020; Kuschminder, Citation2020; Kuschminder & Triandafyllidou, Citation2020; Palillo, Citation2020; Reques et al. Citation2020). This includes systemic kidnapping and extortion experiences (Kuschminder & Triandafyllidou, Citation2020); extended arbitrary detention (Angeletti et al., Citation2020; Reques et al., Citation2020); sexual violence (Palillo, Citation2020; Reques et al., Citation2020), torture (Kuschminder & Triandafyllidou, Citation2020), forced labour (Kuschminder, Citation2020; Reques et al., Citation2020), and experiences of hunger, thirst and illnesses (Ortensi and Kingston, Citation2021). These hardships manifest physically and emotionally resulting in significant harm and vulnerabilities to the asylum seekers and other migrants (Angeletti et al., Citation2020; Reques et al., Citation2020). We argue that such hardship includes what is defined by the European Convention on Human Rights (article 3) as ‘inhumane and degrading treatment’ but also goes beyond it as the hardship experienced is particularly violent, protracted and results in long lasting damage to the people involved. In this section, we provide an overview of the current evidence of hardships experienced by migrants in Libya. The number of recent studies on this topic stresses the frequency and regularity of multiple forms of abuse experienced by migrants in Libya.

Two recent medical studies provide important evidence of the hardships and violence migrants experience in Libya. First, Angeletti et al. (Citation2020) assessed health records of 190 migrants (almost all from Eritrea) disembarking from sea rescue in 2018 in Sicily. The asylum seekers had been held in detention in Libya for up to 21 months wherein they were kept in the dark continually and given one meal a day to share while being repeatedly beaten. Upon arrival, 30 were immediately transferred for medical assistance and the remaining 160 asylum seekers were brought to asylum reception. All of the asylum seekers in reception were severely malnourished with abnormal levels of haemoglobin, serum creatinine, cobalamin, folic acid and Vitamin D. The severe vitamin D deficiency was attributed to being forcibly kept in the dark and not having any access to sunlight. All asylum seekers received a psychological evaluation via the Refugee health screener which pays specific attention to experiences of torture, sexual abuse, post-traumatic stress and anxiety disorder and chronic disease. The study by Angeletti et al. (Citation2020) is highly unique in that first, often reception facilities are not able to provide this level of physical and mental health screening, and second, access to health data is rarely shared with researchers. The results of this study demonstrate how the extreme hardship faced by Eritreans in Libya has physically and emotionally manifested upon these individuals’ bodies and lives as all respondents suffered both physically and psychologically.

In a second study Reques et al. (Citation2020) conducted in an asylum reception centre in France 72 migrants were interviewed regarding their experiences in Libya. The majority of respondents were from the Ivory Coast and Mali, were male and had an average stay in Libya of 180 days. Ninety-four per cent of respondents suffered some type of violence in Libya with 91 per cent suffering physical violence. Forty-nine percent of men reported forced labour in Libya. Women were more likely to experience sexual violence with 53 per cent of women reporting experience sexual violence compared to 18 per cent of men. The results of this study are also striking, demonstrating systemic violence against migrants in Libya. After completing the interview, the majority of respondents asked for psychological help. Request et al (Citation2020) conclude that ‘psychosocial support for this population is urgent’ (p. 5).

Qualitative research (including original data collection by the authors) details the horrific situations faced by migrants in Libya, which makes the above findings unsurprising. Kuschiminder and Triandafyllidou (Citation2020) show how Eritrean migrants entering Libya in the South-east are systemically kidnapped and extorted for ransom by the Tebou tribe. Men and women are aware of the conditions that will face them and often plan for this. Married couples migrate separately as both a risk-diversification strategy and to prevent the potential death of the husband if he were to try and protect his wife from sexual based violence (Kuschminder, Citation2018). Palillo (Citation2020) reports similar findings of the psychological strain on male migrants’ witnessing women being raped and being unable to assist them. One young Gambian respondent stated:

”Blood was coming everywhere; a girl came to me and said ‘Why don’t you help me?’ I told her in the Sahara, the law is this people. They [the smugglers] can do whatever they want to us. Only god can help you.” (Quote in Palillo, Citation2020, p. 8)

The bearing witness to the atrocity and the powerlessness of the experience can formulate severe trauma. The Mixed Migration Centre has also found that women are more likely to witness or experience sexual abuse in Libya (Citation2020). Palillo (Citation2020) also discusses how the migration plans of family back home planning to come to Italy via Libya cause severe emotional distress to the migrants already in Italy that have experienced the hardships en route and desperately try to convince them not the make to journey. Kuschminder and Triandafyllidou (Citation2020) term the desire to migrate despite knowing the potential hardships ahead as ‘self-deception’; reflecting that migrants deceive themselves of the knowledge of hardships in order to propel themselves forward. The reality once experienced is often beyond their possible imaginations.

Having faced extreme hardship in Libya, some migrants are able to make it to Europe – wherein they may face deportation, while others are returned from Libya. Kleist (Citation2020) examined the experiences of Ghanaian returnees from both Europe (whom has travelled through Libya on their journey to Europe) and directly from Libya. Kleist (Citation2020) states: ‘several returnees described coming back unrecognizable, looking like bushmen or ghosts, as they said, with unkempt hair and beards, dirty clothes, and starved or sick bodies’. Return was a challenging endeavour as the migrants’ experience precariousness and social reintegration challenges in that they looked different than prior to their migration (Kleist, Citation2020). Several respondents aspired to re-migrate as they lacked embeddedness and belonging since their experiences.

The frequency and severity of hardships including kidnapping and extortion, physical violence, sexual based violence, and extended arbitrary detention experienced by migrants in Libya are increasingly well documented and indisputable. The above findings demonstrate not only the frequency of these hardships, but more importantly how these hardships lead to lasting physical and psychosocial challenges that extend beyond immediate arrival and arguably will become a defining piece of these individuals lives.

We define extreme hardship as a situation in which the person experiences the following: (a) lack of control of their own circumstances, including imprisonment, kidnapping or enslavement, (b) extreme physical and emotional violence including torture, sexual violence, or extreme psychological violence (c) lasting mental, physical and psycho-social damage arising from the hardship experienced. Extreme hardship is even more pronounced when the conditions protract in time for several weeks or months, and is understood as causing severe physical or mental health problems to the individual that endured it. Standard asylum definitions include different forms of persecution on the basis of a variety of grounds but do not refer to the hardship experienced as a qualifying principle, even though at asylum determination processes, asylum seekers are required to show proof of their having been persecuted including physical scarring for instance (EASO, Citation2018).

3. The humanitarian protection in Italy and the related law and practice

Based on the above considerations and having observed through the volunteer work of the first author that a different practice had emerged in Italy during the last few years and until 2019, whereby refused asylum seekers were provided with a stay permit for humanitarian reasons, we have focused on Italy as a suitable case study. Our aim has been to analyse the Italian practice of providing humanitarian stay permits to migrants who crossed through Libya in order to arrive in Italy and whose applications for asylum had been refused. Below we first provide some information on the methodology adopted for this case study, while in subsequent sections we present the Italian legal and policy framework, the related judicial practices and discuss the implications of our findings in relation to the notion of extreme hardship, and the emerging legal framework of a specific status providing humanitarian protection.

3.1 Methodological considerations

This case study has been based on the review of relevant legal and policy texts concerning the implementation of the stay permit for humanitarian reasons in Italy in the period 2015–2020, the review of relevant statistical data, court decisions and selected interviews with key informants, notably lawyers, judges and social workers that have been involved in judicial cases attributing the stay permit for humanitarian reasons. While our study started with a focus on Tuscany which was the region that we had initially observed this practice through our volunteer work, it expanded to both northern and southern Italian regions (notably Veneto, Lazio, Sicily and Calabria) through chain referral among our interviewees with a view to document more broadly how the stay permit for humanitarian reasons was implemented.

The interviews were semi-structured, took place between April and July 2020, and were mostly conducted via zoom or on the phone because of the pandemic restrictions in place in the country during this time. The interviewees have been anonymized and de-identified. For this reason, we do not provide any further details about their positions, roles or the cities in which they work but only provide the relevant regions. The interviews focused specifically on the relevant legal provisions and the way in which these were interpreted in courts when considering relevant cases. The interviews were conducted in Italian by the first author, while interview protocols were completed in Italian and translated in English (two of the three authors are fluent in both languages, while the third author is fluent in English and has a working knowledge of Italian). Our interviews included 11 experts, notably an ethno-psychologist that provided clinical assessments on the mental health of the applicants, a lawyer and a judge from the Veneto region (North-East); a judge and two lawyers from the region of Tuscany (Centre-West); one judge and two lawyers from Sicily (South); one judge from Lazio (Centre-West) and one judge from the region of Calabria (South-East). The interviewees were recruited purposefully because they all had dealt with cases of asylum seekers, who have received humanitarian protection in appeal (after having received a denial on the first instance) by the regional asylum commissions (Territorial Commissions for the recognition of international protection, hereafter Territorial Commissions).

3.2 The stay permit for humanitarian reasons: Legal framework and reform in 2018

The stay permit for humanitarian reasons has been created in Italy as a residual form of protection available to those not eligible for refugee status, who do not have a right to subsidiary protection but cannot be removed from national territory because of objective and serious personal situations following the prescriptions of art.33 of the Geneva Convention (1951) (Morgese, Citation2015; Open Migration Glossary, Citation2020). In Italy an asylum seeker could receive three types of protection: refugee status, subsidiary protection and humanitarian protection. While the first two are directly regulated by international norms, the humanitarian protection is provided by the Italian legislation, the comprehensive immigration law known as Testo Unico sull’Immigrazione, and more specifically article 5(6) (law 286/Citation1998 (Testo Unico sull’Immigrazione), even though the law serves also to implement the more general duties of protection that Italy has under the European Convention of Human Rights (1953, hereafter ECHR).

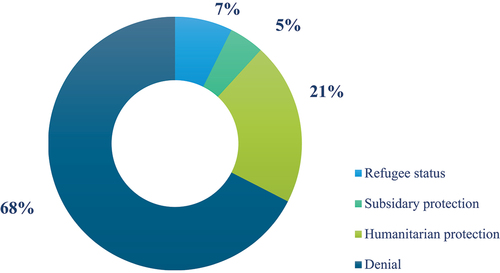

While the first two types of protection are granted to persons who run the concrete risk of being individually persecuted or seriously harmed in their country of origin, the humanitarian protection is conceived for people who face special circumstances. The stay permit for humanitarian reasons is issued by the Questore (who is an executive of the Italian Ministry of Interior), following a recommendation by Territorial Commissions, when ‘serious reasons of a humanitarian nature’ exist or at the direct request of the foreign citizen.Footnote1 The permit is valid for a period ranging from six months up to two years and can be converted into a temporary stay permit for employment purposes, thus providing a bridge to a temporary or long-term residence status. However, it does not provide for family reunification and can be renewed only for the period during which the situation that motivated its issuance, persists (Morgese, Citation2015; Open Migration Glossary, Citation2020). For many people the humanitarian protection – like the other two protections – represents a possible stepping-stone towards achieving a long-term residence status in the country ().

Figure 1. First instance decisions on asylum seekers, Italy, 2018.

It is important to note that the Italian comprehensive immigration law (the Testo Unico referred to above) underwent a significant reform in December 2018, by law no. 132 of Citation2018 (which was strongly advocated by the then Minister of Interior, Matteo Salvini) and a second reform – largely annulling the ‘Salvini decree’, in 2020. Below we explain briefly this double reform with a view of providing the overall legal and socio-political framework of this study.

The Salvini decree abolished the stay permit for humanitarian reasons and introduced two new permits to replace it: a permit for serious health reasons and one for people fleeing environmental disasters. The scope of these permits was narrower and difficult to interpret, they had a limited duration (1 year and 6 months respectively) and could not be converted into stay permits for employment purposes. In addition, the Salvini decree limited the use of the Italian Protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees (the so-called SPRAR) to recognized refugees and holders of subsidiary status excluding those with humanitarian permits. The SPRAR system provided asylum seekers, refugees and people holding humanitarian stay permits with housing, food, language courses, employment-training programs and other activities for up to one year. Humanitarian permit holders accounted for 42.5 per cent of the total beneficiaries served by the SPRAR system (SPRAR, Citation2019). Indeed, Amnesty International Italy warned that the Salvini decree would lead many humanitarian permit holders to homelessness and destitution, making them easy prey to severe exploitation and organized criminal networks (Amnesty International Italia, Citation2020).

In we present the relevant data which show the relative importance of the humanitarian protection status as a means of providing international protection in Italy during the period 2015–2021. While in 2015–2018 this permit accounted for nearly one fourth of all types of protection offered in the country, it fell to 1–2 per cent in 2019–2020 after the Salvini decree entered into force and back to 12 per cent in 2021 in the new formulation.

Table 1. Asylum and international protection numbers in Italy, 2015–2021.

The data provided in show a clear increase in the refusals of applications for international protection which reached over 65 per cent in 2019 and more than 81 per cent considering also those receiving negative decisions since not reachable or for other reasons.

The Salvini decree has been reversed to a large extent by more recent legislation – the so-called Lamorgese decree (decree law 130/2020) which introduced a new stay permit for special protection (casi speciali), similar to the former humanitarian protection status, granted to migrants in special situations. It is noted that protection provided under this permit results from ‘constitutional or international obligations of the Italian state’. This new permit is valid for 2 years and can be converted to a stay permit for employment. The Lamorgese Decree reintroduced the decentralized reception system now renamed SAI (System of Reception and Integration, in sostitution to SPRAR) and restored the asylum seekers’ access to that system.Footnote2

This paper focuses on the previously existing humanitarian protection permit exploring the judicial practice developed around it for three reasons: because of its innovative and path-breaking character, because of the high number of cases that received protection under this regime since 2015 (see above), because our interviewees noted that in 2020, they were still dealing with a high number of pending cases from 2016–2017 as the Court of Cassation (Corte Suprema di Cassazione) had ruled that the ‘Salvini decree’ was not valid retroactively (Sentenza Cassazione Civile Citation2020), and last but not least because this initial humanitarian permit practice was taken up again by the Lamorgese Decree further building this alternative framework of protection. What emerges from our analysis is that the protection granted by the humanitarian permit would not work as a magic solution for all the cases not covered by the international protection forms, but it would work as an effective system of protection for migrants under particular situations caused by extreme hardship while in transit.

3.3 An emerging legal practice

The different Territorial Commissions and Specialised SectionsFootnote3 at ordinary courts examining migration and asylum claims issues in Italy are faced with a varied workload of cases in line with their geographical location. Those near the southern sea borders or at major cities face usually a higher caseload compared to those in other regions. Nonetheless, our fieldwork revealed the emergence of a consistent legal practice across different regions as regards the legal reasoning and arguments used to motivate decisions to assign a stay permit for humanitarian reasons to an applicant. In motivating their reasoning, judges and lawyers relied on international law (relevant international conventions as listed below), European Union law, national law including the Italian Constitution and relevant jurisprudence from the courts to support their arguments.

For what concerns international conventions, the following were cited in judicial decisions: the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (1958); the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984); the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), and the Istanbul Convention (2011) against violence against women and domestic violence.

In addition, judges and lawyers interviewed referred to the Italian Constitution, article 10(3) with regard to the International guarantees provided by it, and also article 5(6) of law 286/1998 with regard to definition of vulnerability and art. 32 of the legislative decree 25 of Citation2008 relative to the implementation of the Council Directive 85 of 2005 on minimum standards on procedures for granting and withdrawing refugee status (Council Directive, Citation2005). Interestingly, after the entry into force of the Salvini decree in December 2018 (and therefore with the effective abolition of humanitarian protection), the President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella (Office of the President of the Republic, Citation2018) reaffirmed the obligation of Italy to guarantee and enlarge the forms of international protection in line with article 10 of the Italian Constitution (Decreto Sicurezza e Immigrazione, Citation2018).

Given our interest in exploring if and how extreme hardship was used in the judicial reasoning, and whether a broader notion of an ethics of care emerged, we asked our interviewees to reconstruct for us the main elements of their reasoning that led them to attribute a stay permit for humanitarian reasons. Our analysis of the relevant court decisions and of our interviews with judges and lawyers showed that the following legal instruments were implemented in relation to the arising issues of protection. The concept of extreme hardship suffered by migrants while transit seems to overlap with multiple articles of ECHR as Italian Constitution according to the different cases analysed.

Where asylum seekers faced human rights violations in their country of origin: for instance due to the danger of inhuman and degrading treatments due to heritage, land division or family conflicts, lawyers and judges recalled the provisions of article 3 (ndr. Prohibition of torture) article 14 (ndr. Non-discrimination) of the ECHR as well as article 3 of the Italian Constitution (ndr. Equal dignity).

When asylum seekers had faced slave-like conditions in their country of origin: our interviewees noted that in some cases religious schools and communities had been used to limit the freedom of the applicants and reduce them to slave-like treatment. In those cases, lawyers and judges made reference to article 2 (ndr. Fundamental rights) of the Italian CitationConstitution of the Italian Republic as much as article 3 (ndr. Prohibition of torture) and article 4 (ndr. Prohibition of slavery and forced labour) of the European Convention on Human Rights and article 19(1) of law 286/1998 or art. 3(4) and 14 of dlgs. 251/Citation2007.

When asylum seekers faced acute economic hardship and risk of abject poverty, a stay permit for humanitarian reasons was used through reference to serious socio-economic factors including environmental degradation and climate change. The legal basis used in this case was that of article 14 of the legislative decree n. 251/Citation2007, providing subsidiary protection for ‘serious damage’.

With reference to asylum seekers excluded from refugee status and subsidiary protection, judges and lawyers used the principle of non-refoulement, particularly when in the countries of origin there was instability and the risk of conflict and violence. In these cases they considered the humanitarian permit as a residual form of protection for those individuals who would suffer if returned to the country of origin because of their own situation but who could not benefit from better forms of international protection.

With regard to asylum seekers who faced serious health issues, lawyers and judges made reference to article 32 of the Italian Constitution (ndr. Health right) as well as article 35 of law 286/1998 with regard to ‘repatriation prohibition’ for people suffering of severe physical or psychological health issues.

Beyond evoking the above specific laws and provisions, the lawyers interviewed actively worked with their clients to bring to the surface the extreme hardship suffered in transit. Territorial Commissions assessing the asylum applications did not inquire about the journey in transit through Libya to reach Italy as this did not pertain strictly to the asylum application.

As reported by a lawyer:

”Neither for the Territorial Commissions nor for the Tribunals, Libya constitutes the main reason for giving humanitarian status and often Libya has represented a consistent piece of life for asylum seekers. The violence and torture suffered there represent one element of the whole framework and they can be proven through certificates or telling of particular personal violence.”

Since Libya is a transit country and not the country of origin, what happened there was not considered relevant for the purposes of the asylum application despite the extreme hardships and related mental and physical health consequences that this had on the applicants. Tellingly, our interviewee lawyer from Sicily reported that once a component of a Territorial Commissions has stopped asylum seeker who was talking about her Libyan experience during her audit, saying ‘no thanks, it is not of our interest’.

A judge from Sicily also added:

”I have been dealing with humanitarian protection for years: before Ghedaffi falling, all applicants went to Libya to work, now instead they suffered torture or, if women, end up in the connecting houses. Obviously, Libya is a transit country, not a country of origin as the humanitarian protection discipline would like, so it is difficult to take the best out of this experience.”

An ethno-psychologist providing mental health assessments showed how the questions asked by the Territorial Commissions could mislead the final assessment:

”I also remember a Nigerian woman, arrived in Italy in 2011 as adult after Libya collapse, but kidnapped when she was 9 years for prostitution in the connecting houses. All her life she was abused in Libya but she hadn’t been trusted by the Territorial Commission since she answered ‘Yes’ to the question ‘would you like to come back home one day?’. She received the humanitarian protection in the appeal.”

Given that hardship suffered in Libya was not included in the initial assessment of the grounds for providing asylum, the lawyers often advised their clients to speak specifically about the hardship suffered there and the related consequences. In contrast to relevant literature that points to asylum hearings and legal aid privileging formal-institutional instead of experiential accounts (Good, Citation2011; Jacobs & Maryns, Citation2021), two of our interviewees (a judge and a lawyer from central Italy) emphasized that:

”[...] the pure tale of asylum seekers, their psycho-physical expressiveness, the ostentation of the wounds and the exhibition of the same: just thinking about is something which provokes reaction [raises sensitivity], along with the medical certification.”

3.4 An indirect evocation of care ethics

Our analysis revealed that the permit for humanitarian reasons was used to provide protection in a wide range of situations in which the need was both individual and situational: the personal story of applicant; the situation of the applicant in the country of origin; the violence suffered during the journey in third countries. While lawyers and judges utilized different legal resources to provide applicants with protection through a humanitarian permit, a decision of the Supreme Court of Cassation in 2018 marked a turning point in the jurisprudence and legal practice and led to the indirect development of an ‘ethics of care’ (Tong & Williams, Citation2018; Tronto, Citation2009). The notion of an ethics of care emerges since the 1980s as part of feminist ethical scholarship which juxtaposes an ethics of justice and rights to one that constructs the moral problem as one of care and responsibility ‘in relationships rather than as one of rights and rules (.) Thus the logic underlying an ethic of care is a psychological logic of relationships, which contrasts with the formal logic of fairness that informs the justice approach’ (Gilligan, Citation1982, p. 73). The central insight in this ethics of care is that the self and others are interdependent (Gilligan, Citation1982).

This logic indirectly informs in fact Decision 4455/Citation2018 of the Cassation Court which noted the importance of assessing the hardship that would be caused to the individual by sending them back to the country of origin in violation of several of their basic human rights (notably putting them at risk of violence and degrading treatment while also depriving them from the private and family life established in Italy). This decision introduced thus an element of comparison between the situation of the applicant in Italy and their situation if they were returned to the country of origin, where they lacked familial or social support or where they could be subjected to downgrading treatment because of what happened to them during the migration. Attention was paid by contrast to the network of support that the applicant had formed in Italy through actively participating in their local society.

While this element of social integration had started being discussed already during 2017 according to our interviewees, decision 4455/Citation2018 of the Cassation Court turned social integration into a crucial element for deciding in favour of a stay permit for humanitarian reasons. This landmark decision affirmed important principles concerning the nature of the humanitarian protection, as distinct from international protection (Favilli, Citation2018). The Court of Cassation’s decision particularly emphasized the need for a concrete comparative assessment between the current condition of the applicant and the risk of human rights violation in the event of his repatriation, assessing if there is any ‘effective and unbridgeable disproportion’ between the two contexts in terms of enjoyment of fundamental rights (Palumbo & Marchetti, Citation2021, p. 69).

The notion of social integration at the destination country was brought forward by several interviewees as a key element in assigning the stay permit on humanitarian grounds. This was a very surprising but also innovative and interesting finding. Judges noted that in consideration of article 8 Right of respect for private and family life, home and correspondence of the European Convention on Human Rights there was an obligation to consider whether the person seeking protection had – while waiting – developed a consolidated life project in Italy, which had to be respected. In Italy this element had been codified in relevant jurisprudence by the Supreme Court of Cassation in 2018. As explained by one of the judges we interviewed:

”The integration path is always a positive factor, however without the Supreme Court of Cassation’s decision no. 4455 of 2018 it would not have been sufficient. A strong integration predisposes also to feel a certain empathy for the asylum seeker: it should be said but it is a sort of subliminal effect. Let’s think about the Georgian caregivers: their repatriation would be absurd given that they also contribute to our society and welfare state. A second effect should be the comparative one: what would happen if you would come back to your country given the absolute lack of any means or familial ties.”

The right to family life supported by the specific decision of the Cassation Court became actually a strong pillar in the processing of applications for the stay permit for humanitarian reasons. Applicants were encouraged to demonstrate that while waiting for their case to be decided, they had been learning the Italian language, and integrating in their local environment whether through participating in activities organized by relevant non-governmental organizations, by taking up work or employment training. Overall renting one’s own accommodation and having a local circle of activities and even friendships that proved a stable private and family life in Italy were all important elements that were considered in court. Proving stable employment was often problematic in southern Italian regions (as our interviewees from southern regions argued) as the jobs available to asylum seekers were often informal but all other aspects were considered crucial too.

Overall it is clear that our interviewees referred to relevant national law but were inspired by relevant rights codified in European and international conventions. They actually invented a humanitarian legal practice inspired by an ethics of care, to cover for what they perceived as important gaps in the national and European asylum system that left out the journey and the hardship suffered while in transit, from the formal consideration of the case for international protection. In fact the analysis of this emerging Italian practice suggests that there is a clear gap in the asylum system that puts at risk important fundamental rights of the applicants, neglects the serious mental and physical health consequences that they have suffered while in transit and overall falls short from the state’s duty to protect fundamental rights.

4. Comparative overview with European countries

A comparative overview of legal provisions and policy practice across a number of European and other countries reveals interesting similarities as well as important differences between other countries and Italy (DLA Piper and OHCHR, Citation2018; European Migration Network, Citation2020). The EMN (2020) study includes in its scope ”protection statuses granted to third-country nationals on the basis of national provisions that do not fall under international protection as established in EU asylum law (i.e., refugee, subsidiary and temporary protection) […] The types of statuses considered include those granted on ‘humanitarian grounds’ but the report does not consider ‘protection grounds deriving directly from international law and for which there are specific EU instruments in place, namely protection for stateless persons and victims of trafficking in human beings or victims of violence, nor does it look at humanitarian visas. The study does not analyse statuses granted to third-country nationals who are considered non-removable due to the impossibility of technically carrying out the return (for lack of travel or identification documents, available transportation, etc.)” (p.5).

The EMN (2020) study notes that ‘The grounds for the national protection statuses remain largely undefined in national legislation’ (p.4) and that ‘Humanitarian reasons’ is not a defined concept, although references to humanitarian grounds can be found in the EU’s subsidiary protection status, in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and in national provisions’ (p.5). On p.9, the report further emphasizes that ‘National protection granted for humanitarian (or compassionate) reasons is one of the most common discretionary grounds in national legislation, and is often a product of national protection policies and encompasses a variety of situations, eventually decided by national authorities and judges, including ministers or even heads of state, with varying levels of discretion’. It is thus clear that humanitarian permits exist across European countries although their implementation and their defining elements remain quite nebulous and open to interpretation, as in fact we have documented in our study.

Considering grounds for humanitarian protection in 27 countries around the world, the study by DLA Piper and OHCHR (Citation2018) shows that a number of elements considered in Italy’s humanitarian permit characterize generally provisions providing grounds for humanitarian protection in 27 countries around the world (p. 4), notably:

An absolute prohibition of non-refoulement under international human rights law arising from the right to life and the prohibition of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment;

The risk of human rights violations in case of return to the country of origin, which are different from and broader than the absolute prohibition of non-refoulement;

Presence of situations of serious human rights violations in the country of origin;

Occurrence of natural disasters in the country of origin;

Health status and unavailability and/or inaccessibility of the right to health in the country of origin;

Protection of the right to private and family life in the country of destination;

Presence of bonds with the country of destination, which take into account length of stay, as well as employment, social, family and emotional ties;

Where migrants are victims of smuggling and witnesses or victims of trafficking, in some cases including when they do not cooperate with authorities because of safety or humanitarian considerations;

Being a pregnant woman;

Being an unaccompanied child.

Looking more closely into European countries bordering the Mediterranean, both Spain and France have similar humanitarian permit provisions concerning the vulnerability of the applicant (who has not qualified for asylum or other such protection) including illness or risk of being subject to inhumane treatment at the country of origin but also emphasizing cases in which the applicant was the victim of labour exploitation, domestic violence or a racist crime in Spain (DLA Piper and OHCHR, Citation2018, p. 22) and previous stays in France with proper status, ties with family in France or contributions to French society.Footnote4 In Greece a similar humanitarian permit also exists (AIDA ECRE, Citation2022) but at the time of publication of that report it had never been applied.

The elements considered for humanitarian permits in Europe and around the world, with the exception of point 8 cited above concerning victims of smuggling or trafficking, do not include experiences ‘in transit’. Instead the issues considered refer mostly to circumstances/experiences in either the country of origin or the country of destination. There are several converging factors that have facilitated the emergence of this practice in Italy from the ground up, which are not shared by Spain for instance or Greece. While all three are frontline countries in receiving migrants and asylum seekers crossing the sea in unworthy dinghies, it is Italy that received the highest number of people who spent time in Libya while in transit, experiencing extreme hardship. As argued earlier in this paper, that hardship was such that it had serious and lasting effects on the mental and physical health of the people concerned. Thus, Italian judicial authorities had to face a legal and moral puzzle on providing for these people even though they did not qualify for asylum, based on considerations concerning their country of origin and their reasons for leaving.

Searching further the humanitarian permit legislation and practices emerging across Europe, it is only in Germany (Gonzalez Beilfuss & Koopmans, Citation2021, p. 21) where we find an explicit mention of hardship: in exceptional cases, foreigners can qualify for a residence permit under a discretionary clause, the so called ‘hardship rule’ if there are urgent personal or humanitarian reasons to authorize their stay. This rule is applied on a case-by-case basis, at the request of a ‘hardship committee’ introduced by the state. There are no set criteria or procedures for this permit and issues like the means of subsistence of the foreigner are to be taken into account, and permits to be refused when a return date has already been determined or if the applicant has committed criminal offences of substantial weight (op. cit). During 2022, the Hardship CommitteeFootnote5 examined 305 cases affecting 483 people and the positive answers rate for the 202 cases examined was 96% . A small number of cases were considered also in 2021 and about three quarters of them were approved. Germany also offers residence permits based on the applicant proving they have been integrated in society including speaking the language, having spent in the past periods of legal albeit temporary status (Gonzalez Beilfuss & Koopmans, Citation2021, pp. 20–21). The situation though in Germany is quite different as these provisions were not aimed to particularly address a significant number of people needing protection because of hardship experienced in transit but rather aimed to cast a broader even if exceptional protection net for those that had experienced hardship in Germany but had at the same time sought to integrate in the country.

This comparative review shows that the Italian provisions for humanitarian permits are in line with those of other European countries but the legal and judicial practice presents two unique innovative features: considering the extreme hardship that the applicant has gone through while in transit (rather than at destination or origin); and also considering as a supportive element the establishment of a life at destination and the applicant’s efforts to become ‘integrated’. Interestingly while these two elements are present in the German legislation, they are implemented very differently as they are not considered explicitly in tandem and most importantly they do not include considerations of hardship en route. It may well be argued that the Italian case shows how judicial practice supported by civil society interventions can pilot solutions from the ground up that are then enhanced by legislation, where existing legal provisions may fall short of the complexities of actual cases.

5. Discussion and conclusion

It is evident that Italy has become the foreground for a changing category of migrants in need of protection and has developed an innovative humanitarian permit that is unique from other European countries to address this group. The hardships faced by migrants in Libya while in transit to Italy are well-documented and indisputably cause lasting physical and mental conditions. This group of arrivals does not fit existing labels: they are not refugees, nor merely migrants, nor victims of trafficking. The extreme hardship suffered en route is rarely acknowledged by the Italian Territorial Commissions, and this permit is rarely tied to this suffering. We propose the label of migrants experiencing extreme hardship and argue that they these hardships place them in need of protection: the humanitarian permit could be used for this purpose, although evidence that it has been used for these purposes remains thin.

Since 2016 the number of asylum seekers receiving refugee status or subsidiary protection in Italy has been less than one quarter of applicants. It is well demonstrated in the literature that there is need for reform in the refugee protection regime that is based on a seventy-year-old convention (see for example Collins, Citation2019; Harvey, Citation2015) and this is exemplified in the Italian case wherein current arrivals do not fit the existing protection regime. The Italian case elucidates an alternative to meet the protection needs of a changing cohort of migrants that have experienced extreme hardship while en route. Our analysis of the Italian case points to the importance of including the ‘transit’ phase in the codification of humanitarian permits.

The emergence of the Italian humanitarian permit as an effective system of protection for migrants under particular situations caused by extreme hardship while in transit – and even the abolition and restoration of this system – testifies to the importance and need for a special status that would provide protection to migrants who suffered extreme hardship while in transit and who do not qualify either for subsidiary protection or asylum. We point out that the international protection regime does not account for experiences in transit while privileges the linear notion of the journey from the source country to the destination country without taking in consideration what migrants suffer in between. And yet extreme hardship while in transit is not a unique phenomenon in the Mediterranean area, such hardship has been recently documented for migrants seeking to cross the Darien gap, a 100-kilometre stretch of treacherous jungle shared by Colombia and Panama (Basok & Candiz, Citation2023).

The creative jurisprudence and legal practice that have developed in Italy point to the importance of fundamental rights and to the multiple national, European and international law instruments that can contribute towards filling this gap and avoiding exposing people who have suffered significant physical and mental health harm to further hardship and risks. At the European level such protection could take a variety of legislative forms. An appropriate and comprehensive form of protection would involve the introduction through a relevant Directive of an EU level permit for humanitarian protection that would apply to people who do not qualify for asylum, who have lived in the EU for a certain period of time (whether with or without status), who are unable to return to their country of origin or last country of residence for various reasons and who have suffered significant mental or physical health damage in relation to extreme hardship experienced while in transit towards the EU.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank those, doctors, lawyers and judges, who gave time for interviews.

They also wish to thank Dr. Talitha Dubow for her invaluable help.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Asylum seekers lodge their initial application with the Territorial Commissions. They may receive a positive first instance decision, providing to them one of the three types of international protection, notably refugee status, subsidiary protection or humanitarian protection. They may receive a negative first instance decision to which they can appeal. A stay permit for humanitarian reasons can be provided therefore also as a second instance decision based on their appeal to the negative first instance outcome.

2. For a full analysis of these changes see Palumbo and Marchetti (Citation2021), VULNER report.

3. The Security Decree no. 13/2017 - also known as ‘Minniti-Orlando Decree’ (later converted with amendments into law no. 46/Citation2017) introduced Specialized Sections in matters of migration, international protection and free movement of citizens of the European Union at the ordinary courts where the Courts of Appeal are located.

4. For more information, see https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F2209 and https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F16053.

References

- AIDA ECRE. (2022). Temporary ProtectionGreece. Available: https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/AIDA-GR_Temporary-Protection_2022.pdf

- Amnesty International Italia, (2020), I sommersi dell’accoglienza, Available at: https://immigrazione.it/docs/2020/amnesty-i-sommersi-dellaccoglienza.pdf Available at

- Angeletti S., Ceccarelli, G., Bazzardi, R., Fogolari, M., Vita, S., Antonelli, F., Florio, L. D., Khazrai, Y. M., Noia, V. D., Lopalco, M., Alagia, D., Pedone, C., Lauri, G., Aronica, R., Riva, E., Demir, A. B., Abacioglu, H., & Ciccozzi, M. (2020). Migrants rescued on the Mediterranean Sea route: Nutritional, psychological status and infectious disease control. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 14(5), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.11918

- Attuazione della direttiva 2005/85/CE recante norme minime per le procedure applicate negli Stati membri ai fini del riconoscimento e della revoca dello status di rifugiato, pubblicato nella Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 40 del. (2008 Febbraio, 16). ( Italian) Available at: https://www.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/Testi/08025dl.htm

- Basok, T., & Candiz, G. (2023) Darien Gap: As migrants take deadly risks for better lives, Canada and the U.S. must do much more. The Conversation, published on 30 October 2023, Retrieved November 7, 2023. https://theconversation.com/darien-gap-as-migrants-take-deadly-risks-for-better-lives-canada-and-the-u-s-must-do-much-more-215520

- Cassazione. (2018 Febbraio, 23). I Sezione Civile. n. 4455, Available at: https://www.questionegiustizia.it/data/doc/1584/cassazione_4455_2018.pdf

- Cassazione Civile. (2020 January 20). n. 1104 Sentenza. Available at: https://sentenze.laleggepertutti.it/sentenza/cassazione-civile-n-1104-del-20-01-2020

- Collins, E. (2019). The case for reforming the definition of ‘refugee’ in the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the status of Refugees. Bristol Law Review, 90–113.

- Constitution of the Italian Republic. Available at: https://www.senato.it/documenti/repository/istituzione/costituzione_inglese.pdf

- Council Directive. (2005). 85/EC of 1 December 2005 on Minimum Standards on Procedures in Member States for Granting and Withdrawing Refugee Status. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32005L0085

- Crawley, H., & Skleparis, D. (2018). Refugees, migrants, neither, both: Categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe’s ‘migration crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224

- Decreto Legislativo. (2007 Novembre, 19). n. 251 Attuazione della direttiva 2004/83/CE recante norme minime sull’attribuzione, a cittadini di Paesi terzi o apolidi, della qualifica del rifugiato o di persona altrimenti bisognosa di protezione internazionale, nonché’ norme minime sul contenuto della protezione riconosciuta. ( Italian). Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/04/18/17G00059/sg/

- Decreto Sicurezza e Immigrazione. (2018 October 04). Mattarella emana e scrive a Conte, Comunicato del Quirinale. ( Italian) Available at: https://www.quirinale.it/elementi/18098/

- DLA Pipe & OHCHR. (2018). Admission and Stay Based on Humanitarian Rights and Humanitarian Grounds: A Mapping of National Practice. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Migration/OHCHR_DLA_Piper_Study.pdf

- Erdal, M. B., & Oeppen, C. (2018). Forced to leave? The discursive and analytical significance of describing migration as forced and voluntary. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(6), 981–998. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384149

- European Migration Network. (2020). Comparative Overview of National Protection Statuses in the EU and Norway (EMN Synthesis Report for the EMN Study 2019). last Retrieved September 15, 2023. Available at: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/news/emn-study-comparative-overview-national-protection-statuses-eu-and-norway-2020-05-27_en

- European Union Agency for Asylum. (2018). Evidence and Credibility Assessment in the Context of the Common European Asylum System – Judicial Analysis. Available at: https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/easo-evidence-and-credibility-assesment-ja_en.pdf

- Favilli, C. (2018). La protezione umanitaria per motivi di integrazione sociale. Prime riflessioni a margine della sentenza della Corte di Cassazione, no. 4455/2018. Questione Giustizia, Available at: https://www.questionegiustizia.it/articolo/la-protezione-umanitaria-per-motivi-di-integrazion_14-03-2018.php ( Italian)

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. CUP.

- Gonzalez Beilfuss, M., & Koopmans, J. (2021). Alternatives to pre-removal detention in return procedures in the EU. University of Barcelona. AdMiGov Deliverable 2.5.

- Good, A. (2011). Witness statements and credibility assessments in the British asylum courts. In L. Holden (Ed.), Cultural Expertise and Litigation: Patterns, Conflicts, Narratives (pp. 94–122). London: Routledge.

- Harvey, C. (2015). Time for reform? Refugees, asylum-seekers, and protection under international human rights law. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 31(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdu018

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2022), IOM Libya 2021 Annual Report. Available at: https://libya.iom.int/

- Jacobs, M., & Maryns, K. (2021). Managing narratives, managing identities: Language and credibility in legal consultations with asylum seekers. Language in Society, 51(3), 375–402. Retrievedonline on March 4, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404521000117

- Jubilut, L. C., & Martins, M. (2019). Shortcomings and/or missed opportunities of the Global compacts for the protection of forced migrants. International Migration, 57(6), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12663

- Kirby, P. (2020). Sexual violence in the border zone: The EU, the women, peace and security agenda and carceral humanitarianism in Libya. International Affairs, 96(5), 1209–1226. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa097

- Kleist, N. (2020). Trajectories of involuntary return migration to Ghana: Forced relocation processes and post-return life. Geoforum, 116, 272–281.

- Kuschminder, K. (2018). Afghan refugee journeys: Onwards decision making in Turkey and Greece. Journal of Refugee Studies, 31(4), 566–587. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fex043

- Kuschminder, K. (2020). Before disembarkation: Eritrean and Nigerian migrants journeys within Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(14), 3260–3275. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804192

- Kuschminder, K., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2020). Smuggling, trafficking, and extortion: New conceptual and policy challenges on the Libyan route to Europe. Antipode, 52(1), 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12579

- Legge. (2017, Aprile 13). n. 46 Conversione in legge, con modificazioni, del decreto-legge 17 febbraio 2017, n. 13, recante disposizioni urgenti per l’accelerazione dei procedimenti in materia di protezione internazionale, nonché’ per il contrasto dell’immigrazione illegale, Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/04/18/17G00059/sg ( Italian)

- Legge. (2018, Dicembre 1). n. 132 , Conversione in legge, con modificazioni, del decreto-legge 4 ottobre 2018, n. 113, recante disposizioni urgenti in materia di protezione internazionale e immigrazione, Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/12/03/18G00161/sg ( Italian)

- M. M. C. (2020). MMC North Africa 4Mi snapshot protection risks within and along routes to Libya - a focus on sexual abuse. Available at: https://mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/075_snapshot_na.pdf

- Mainwaring, C., & Debono, D. (2021). Criminalizing solidarity: Search and rescue in a neo-colonial sea. Environment & Planning C Politics & Space, 39(5), 1030–1048. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420979314

- Mann, I., & Mourão Permoser, J. (2022). Floating sanctuaries: The ethics of search and rescue at sea. Migration Studies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3913982

- Mcdowell, S. (2022). Geopoliticizing geographies of care: Scales of responsibility towards sea-borne migrants and Refugees in the Mediterranean. Geopolitics, 27(2022), 444–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1777400

- Ministero dell’Interno. (2023). Cruscotto statistico giornaliero. Available at: http://www.libertaciviliimmigrazione.dlci.interno.gov.it/it/documentazione/statistica/cruscotto-statistico-giornaliero

- Morgese, G. (2015). Lineamenti della normativa italiana in materia di immigrazione. Università di Bari.

- Office of the President ff the Republic. (2018). Press Release. Available at: https://www.quirinale.it/elementi/18098

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). (2023). Independent Fact Finding Mission on Libya. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/libya/index

- Open Migration Glossary. (2020). Humanitarian protection. Open Migration. Available at: https://openmigration.org/en/glossary-term/humanitarian-protection/

- Ortensi, L. E., & Kingston, L. N. (2021). Asylum seekers’ experiences on the migration journey to Italy (and beyond): Risk factors and future planning within a shifting political landscape. International Migration, 00, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12849

- Palillo, M. (2020). He must be a man’. Uncovering the gendered vulnerabilities of young Sub-Saharan African men in their journeys to and in Libya. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1816813

- Palumbo, L., & Marchetti, S., (2021), Vulnerability in the asylum and protection system in Italy: Legal and policy framework and implementing practices, VULNER project, Research Report, Available at: https://www.vulner.eu/78645/VULNER_WP4_Report1.pdf

- Reques L., Aranda-Fernandez, E., Rolland, C., Grippon, A., Fallet, N., Reboul, C., Godard, N., & Luhmann, N. (2020). Episodes of violence suffered by migrants transiting through Libya: A cross-sectional study in “médecins du Monde’s” reception and healthcare centre in seine-saint-denis, France. Conflict and Health, 14(12). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-0256-3

- Sistema di protezione per i richiedenti asilo e i rifugiati (SPRAR). (2019). Rapporto Annuale SPRAR/SIPROIMI 2018. Available at: https://www.retesai.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Atlante-Sprar-Siproimi-2018-leggero.pdf

- Spencer, S. (2022). Migrants with Irregular Status in Europe, COMPAS. Available at: https://cmise.web.ox.ac.uk/

- Testo unico sull'immigrazione. (1998). Available at: https://www.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/98286dl.htm

- Tong, R., & Williams, N. (2018). Feminist ethics. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/feminism-ethics/

- Tronto, J. (2009). Un monde vulnérable. Pour une politique du care. La Découverte.

- United High Commissioner For Refugees (UNHCR). (2021). Available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5205

- Yuen, L. (2019). Overview of migration trends and patterns in the Republic of the Niger, 2016–2019. In F. Fargues, M. Rango, E. Börgnas, & I. Schöfberger Eds., Migration in west and North Africa and across the Mediterranean. International Organization for Migration (IOM. Chapter 52020Available at https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/migration-in-west-and-north-africa-and-across-the-mediterranean.pdf

- Zetter, R. (2015). Protection in crisis: Forced migration and protection in the Global Era. Migration Policy Institute.