ABSTRACT

This paper takes an interest in tackling inequalities in school communities and considers how networks of change agents can work together to enact change. To do so, an ethnographic study is conducted examining WomenEd, a charity and grassroots movement of aspiring and existing women leaders in education. Building upon the perspective of collective leadership as a social process, the ‘social-symbolic work’ perspective is applied to analyse the activities of the movement. By drawing upon observations and interviews conducted over a three-year period, this paper offers detailed depictions of the motivations, practices, and effects of the social-symbolic work of WomenEd. The study observes a form of collective leadership underpinned by valuing difference, which enables participants to respond to oppressive school conditions and achieve shifts in autonomy and agential institutional influence. The study thus advances understanding of collective power, or ‘power with’, and the practical activities which can affect change, ‘power work’. Building upon Crenshaw's concept of intersectionality, we term the WomenEd practices ‘intersectional collaboration’, a novel form of collective leadership for social change. The study highlights the significance of inclusion and intersectionality in theorising ‘collectivity’, which has implications for understanding collective leadership and social change.

Introduction

This section introduces and outlines how this study addresses critical gaps in understanding school leadership by prioritising issues of social justice. A focus upon the nuanced perspectives of women, via a study of their practices and lived experiences, offers a fresh conceptualisation of leadership which can respond to gaps in understanding both organisational and social change. A ‘critical perspective’ on leadership is defined as prioritising the interests of marginalised groups (Alvesson and Ashcraft Citation2010). This approach has been adopted by scholars of feminisms and critical management studies, who have, for several decades, taken issue with the focus of organisation and management studies upon a narrow set of managerial dilemmas (e.g. Acker Citation1990; Alvesson and Willmott Citation1992). In studying the practices of WomenEd, we thus respond to calls to study grassroots organising and solidarity building, which ‘remains under-theorized within organization studies’ (Smolović Jones, Winchester, and Clarke Citation2021, 2).

The study of social movements such as WomenEd, which seek to resist and challenge the status quo in education, enables us to illuminate practices and structures which are problematic for marginalised groups. As noted by Rodriguez et al. (Citation2016), studies of intersectional organising, such as WomenEd, offer the opportunity ‘to interrogate mainstream topics such as leadership’ (214), to understand how logics in both practice and theory may (re)produce inequalities. This approach shines a light on alternative forms, or ‘postmodern’ forms, of organising, through which logics of ‘hierarchy, formalization and unitary rationalization’ may be replaced by agility, specialisation, innovation, and social justice (Lawrence and Phillips Citation2019, 129). This study aims to contribute to an understanding of school leadership in the context of these ‘postmodern’ forms of organising, which have been conceptualised as ‘ecosystems’ of activity occurring in-between and across organisations (Heucher et al. Citation2024).

Participants in this study have come together as part of WomenEd to critically examine existing school leadership practices and to seek to address the interacting inequalities in their school communities. They have also practically realised a novel form of collective leadership through their organising activities within the movement. This form of collective leadership, ‘intersectional collaboration’, is underpinned by valuing intersectional differences and the expression of difference in identity. This study, therefore, presents an important opportunity to reflect and re-imagine school leadership, towards institutionalising more equitable forms of organising. To aid reflection, our table of practice descriptions () is intended as a tool for practitioners to consider, and contrast, with existing practice. Furthermore, given that participants in this study experience shifts in autonomy and agential institutional influence through their engagement with the WomenEd movement, this study both illustrates the function of a network organisation in affecting change, and provides insights into the social processes antecedent to change for marginalised insiders. The discussion section focuses on how these collective actors use the WomenEd movement to create and share resources. This article thus contributes to important ongoing debates in organisational studies regarding emancipatory social change and our capacity to respond to ‘Grand Challenges’ (Creed et al. Citation2022; Gray Citation2023).

Table 1. The practices of intersectional collaboration.

The next section provides a critical literature review which identifies gaps in leadership studies pertaining to conceptualising power dynamics and collective agency, within leadership theories.

Literature review

This critical literature review addresses gaps in leadership studies coalescing around the insufficient exploration of collective leadership (CL). In the first section, we explore existing critiques and limitations of school leadership, focusing on CL. In the second section, we engage these debates with broader critical perspectives in management and organisational studies which aim to address inequalities via an understanding of power.

Existing limitations and critiques

Critical perspectives of school leadership have often challenged neoliberal discourses associated with the use of ‘market’ logic. Blackmore (Citation2013) suggests school leaders are now ‘confronted with evidence of growing educational inequality’ linked to ‘neoliberal reforms and deindustrialization’ (140). She traces the evolution of contemporary educational leadership discourses, including those on ‘distributed leadership’, suggesting the emancipatory potential of critical scholarship has been ‘neutralized’ (145) in the implementation of leadership theories in practice. Similarly, Harris, Jones, and Ismail (Citation2022) highlight how distributed leadership can operate as a ‘palatable way of engineering greater organisational control’, arguing ‘it is important not to lose sight of these critical perspectives’ (439) (see also: Fitzgerald and Gunter Citation2008; Harris Citation2013; Mifsud Citation2017).

In addition to critiques of the implementation and impact of collective leadership (CL) in respect of inequalities, there exists a lack of empirical studies furthering our understanding of CL, together with methodological challenges (Harris, Jones, and Ismail Citation2022; Ospina et al. Citation2020; Ospina and Foldy Citation2016; Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond Citation2001). Methodological challenges emerge, at least in part, because CL represents an umbrella of diverse scholarship, a proportion of which seeks to re-conceptualise leadership. Harris, Jones, and Ismail (Citation2022) point to the foundational work of Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond (Citation2001) on distributed leadership as ‘a fundamental re-conceptualisation of leadership as practice’ (439). This practice perspective challenged the notion of heroic individuals leading change (Spillane Citation2005). It also challenged ‘conventional wisdom about leadership defined as discreet leadership roles or functions’ (Harris, Jones, and Ismail Citation2022, 439). Spillane, Halverson, and Diamond (Citation2001) referred to the ‘taken-for-granted’ artefacts of leadership, and to ‘structure’ more generally, which meant ‘not only organizational structures, but also broader societal structures, including race, class and gender’ (21). One challenge is the way in which an understanding of collective leadership requires an understanding of both ‘macro- and micro-understandings of the phenomenon of CL itself’ (Ospina et al. Citation2020, 455). However, studies which foreground power structures in understanding the social practices and processes of school leadership have not proliferated.

More broadly, there are calls to draw on the untapped potential of critical perspectives in leadership and organisation studies as a ‘neglected empirical and theoretical presence in the study of organisations and social relations at work’ (Bell et al. Citation2019, 4; Calas and Smircich Citation2010; Fotaki and Pullen Citation2023). By locating a control-resistance dynamic, such critiques highlight empirical gaps in which the taken-for-granted norms and practices of ‘leadership’ are contested and rearticulated. Furthermore, portraits of workplace deviance and risky activism do not well describe network organisations such as WomenEd which may even be endorsed by employers because of their professional development offering (Lawrence and Buchanan Citation2017; Oyakawa, McKenna, and Han Citation2021). There thus exist corresponding conceptual gaps in understanding the leadership processes engaged in both organisational and social change (Creed et al. Citation2022; Gray Citation2023). The following outlines two critical strands of work in organisation and management studies which we argue stand to enhance the CL lens, namely institutional and identity perspectives towards power.

Extending critical perspectives

Starting with the literature informed by new institutional theory, this strand of scholarship offers a way of foregrounding the operation of power via taken-for-granted arrangements, norms, logics and practices, and the role of institutions in reproducing inequalities. For example, Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell (Citation2010) conceive of a feminist institutional perspective which offers the opportunity to analyse mechanisms by which ‘power asymmetries are naturalized’ (582). Similarly, Amis, Mair, and Munir’s (Citation2020) extensive review identifies institutionalised ‘myths’ which are central to the reproduction of inequalities. The ‘institutional work’ perspective has also been applied to leadership by Novicevic et al. (Citation2017), drawing upon the ‘collective and situated lived experience of organisational leaders’ (591) to understand processes of social change (see also: Stott and Fava Citation2019). Similarly, Creed, Dejordy, and Lok (Citation2010) take an institutional perspective and examine the lived experience of LGBT ministers in the church. Their methodological imperative is to consider both emotions and identity within institutional perspectives. Their study provides an example of how ‘institutionalized marginalization’ (1336) may operate via roles. This perspective sees roles as exclusionary categories, and also points to stronger links between an institutional ‘taken-for-granted’ notion of power, and studies which treat power at the level of social identities such as sexuality, race and gender (see also: Styhre Citation2014; Yarrow and Johnston Citation2022).

Feminisms and critical management studies make important contributions to understanding leadership as a potential site of contestation and resistance over meanings connected to role and social identity. For example, for Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002), identity work is defined as ‘interpretative activity involved in reproducing and transforming self-identity’ (627), where leadership is a ‘commonsensically valued’ identity, with ‘positive cultural valence’ (Alvesson and Willmott Citation2002, 620). Also focusing on identity and power, intersectional perspectives have nuanced our understanding of social identity by suggesting that experiences of marginalisation are not universal, and depend upon complex intersections such as race, sexuality, class etc. Crenshaw’s (Citation1991) foundational work also highlighted the interplay between the empowering use of identity difference within social movements:

social power in delineating difference need not be the power of domination; it can instead be the source of social empowerment and reconstruction. (Crenshaw Citation1991 1242)

In conclusion, a critical literature review reveals the limitations of existing work coalescing around CL and highlights the advantages of integrating into leadership studies insight from scholarship on intersectionality and marginalised experience of identity with more institutional approaches to inequalities.

Research question

A thorough examination of the literature motivates our research question, context selection, theoretical framework, and methodological approach. A critical literature review points to the need to understand the social processes and practices through which leadership is shaped, contested, and rearticulated, leading to our over-arching research question:

How do members of WomenEd re-conceptualise leadership in organising for social change?

Theoretical framework

A critical literature review identified gaps in understanding the role of identity and institutions in the context of leadership. As a theoretical framework, social-symbolic work can integrate insights traditionally separated to ‘micro’ (identity) and ‘macro’ (institutional) levels of analysis, while offering a way of conceptualising leadership as a collective social process. Social-symbolic work sits within the interpretivist/symbolic paradigm and draws upon critical epistemologies in understanding power. Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2019) discuss how they integrate the social constructivist perspective with Foucault’s on power such that the processes through which ‘construction occurs are infused with heterogeneous forms of power’ (7). The framework considers two important analytical foci; ‘social-symbolic work’ (e.g. identity work, institutional work) and ‘social-symbolic objects’ (e.g. leadership, school), and considers their interplay. They suggest social-symbolic work is directed at observable social-symbolic objects and delineate social-symbolic work from other forms of practices by explaining it is intentional and sustained over time.

Allen (Citation2009) provides an excellent discussion of poststructuralist, intersectional, and ethnomethodological perspectives on power and agency which further elucidates the need for an understanding of leadership as collective. Her exploration highlights that both Butler’s (Citation2006) and West and Zimmerman’s (Citation1987) approaches reject the notion of social identity as reflecting a fixed nature, viewing them as a ‘performance’ or interactional accomplishment based upon norms, acceptability, or accountability. This perspective implies power structures and flows can be shaped through interactional performances. Allen also suggests the meeting point of these perspectives is an account of agency that recognises ‘it is always situated in existing relations of power and in relation to prevailing norms’ (Allen Citation2009, 302). Allen sets out the limitations of these perspectives and argues for a better understanding of collective power, or ‘power-with’.

Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative research strategy, chosen for its capacity to enable ‘critical listening’, as defined by Alvesson and Ashcraft (Citation2010). This approach aims to authentically capture the social realities of participants, identifying local themes significant to them that also intertwine with broader political, moral, or ethical phenomena of topical and theoretical interest. The qualitative strategy further facilitates the exploration of these themes, and their variations, by preserving the multiplicity of participant voices, including ‘competing participant voices’ (Alvesson and Ashcraft Citation2010, 68). Within the qualitative approaches examined in the literature review, a methodological focus upon emotion has been emphasised particularly by scholars integrating an understanding of identity with institutional perspectives when understanding power (e.g. Creed, Dejordy, and Lok Citation2010). The ethnographic approach undertaken engages the lead researcher in the emotional dynamics present in the setting as a way of understanding the motivations and effects of social-symbolic work through affect (Gherardi Citation2019; Lok et al. Citation2017).

In this study, ethnography offers the potential to examine leadership as a collective form of work, and as an object of contestation and rearticulation. As noted, developments in CL require that the locus of leadership is not presumed to reside only within specific organisational activity or with particular people. Critical perspectives have tended to view ethnographic approaches as ‘ambitious research practice offering rich and in-depth access to organizational life’ (Alvesson and Ashcraft Citation2010, 70). Studies of resistance have also highlighted ethnographic approaches as key to observing processes of emancipatory organising (Prasad and Prasad Citation2000; Thomas and Davies Citation2005). Similarly, Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2019) attribute success to ethnographic accounts of social-symbolic work, particularly when observations are triangulated with interviews (e.g. Smets, Morris, and Greenwood Citation2012). In summary, an ethnographic approach is informed by the need to move beyond traditional notions of leadership and to explore the role of emotion, resistance, and power in understanding the practices of leadership which can affect change.

Context selection

The literature review highlights the need to select an empirical context in which school leadership is contested and rearticulated, and to expand the notion of leadership beyond specific roles to consider collective social processes, and their implications for organisational and social change. In response, WomenEd is selected as a grassroot movement in which diverse women come together in solidarity to address systemic issues in education. Discourse regarding leadership is very prevalent in the movement and part of their mission: ‘WomenEd connects aspiring and existing women leaders in education and gives women leaders a voice in education’ (WomenEd Citation2020). WomenEd was founded in the UK and has expanded to twenty-one countries. It has recently become a charity in the UK. During the study the movement had over 44,000 followers on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter). The role of the Internet in the formation and daily activities of the movement is significant, for example, members may speak daily with each other online via X and WhatsApp, but infrequently meet in person. Members are also often recruited to support activities via social media, many of these activities involve mentoring members in the network and sharing skills by providing both informal and formal training. WomenEd operate a platform through which some members can also engage in publishing, including book chapters (Featherstone and Porritt Citation2021; Porritt and Featherstone Citation2019).

Ethical considerations and positionality

Scarce school leadership studies have noted an interest in marginalised experience, furthermore ethical implications can prevent data collection from vulnerable groups. For example, Creed, Dejordy, and Lok’s (Citation2010) study of institutional contradiction notes:

‘Snowballing’ and convenience sampling are common and often inevitable techniques for generating data in organizational research on groups with invisible, stigmatized identities because of secrecy and fear of discrimination (1340)

Sampling strategy

The sampling strategy adopted responds to the ethical concerns discussed in the previous section via the selection of those participants for interviews who were already active within the public domain. These were also members who occupied more formalised roles within the movement and represent a purposive sample with regard to understanding the shared practices established at WomenEd events (Bryman Citation2016). The observational data came from attendance of WomenEd’s ‘Unconferences’, selected because they represent the largest events held by the movement. Interview participants were all present at, and spoke, during these events.

To select interview participants, we contacted one of the founders and used a referral method to identify the most active members, this approach self-limited the sample size to seven. Participants self-described as: Asian, mixed-race, white, disabled, lesbian, queer, middle-class and working-class (or intersections of these). We did not attempt to control the social categories present in the sample, as this approach is problematised by the study which seeks to observe the intersectional organising practices. As Acker (Citation2006) observes, ‘focusing on one category almost inevitably obscures and oversimplifies other interpenetrating realities’ (2006, 442). For the ethical reasons discussed, ethnographic observations included in our dataset were restricted to data that were, or would be, published in the public domain. The ‘Unconference’ events, attended by the first author, were recorded and published on YouTube by the WomenEd organisation.

Social-symbolic work is defined as involving ‘intentional efforts’, therefore, the social-symbolic work perspective assumes that the motivations and effects of social-symbolic work are available for study. It is also assumed that the observations made of the practices of WomenEd are generalisable to the population of the movement because the events observed are attended by many members and are collectively practiced within these events. However, the motivations and effects are based upon interviews and a sampling size limited to seven members, who were at the time active members of the movement. We apply a form of heuristic generalisation (Tsoukas Citation2009) in understanding how these collective practices are linked to motivations and effects, which enables us to theorise a mechanism of change explored in the discussion section. This form of generalisation is unlikely to apply universally for all members of the network – in particular, one might expect periphery members to have different motivations and to derive different effects from their engagement. We align with Tsoukas (Citation2009) that the merits of a qualitative study are in capturing the particulars of a context to explain a social phenomenon of interest, and not in seeking to generate universally applicable ‘laws’ of social interaction.

Data collection

Alongside observation of practices via events, in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted which lasted between 1 and 3 h. We also invited participants to engage in follow-up questions, and to share archival materials they may have referred to during observations with us via social media or email. The use of digital ethnography as ‘the application of ethnographic approach to contexts where the field is predominantly a digital environment’ (Jensen et al. Citation2022, 1145) was central because of the Covid-19 pandemic, and because WomenEd is accessed by members predominately via the internet. As Jensen explains, ‘collection of rich data for digital ethnographies … often requires the researcher to follow study participants through several digital spaces’ (1145). We used field notes to capture observations of digital spaces, such as social media exchanges, together with audio and video capture which were then transcribed.

Given the critical underpinnings of this study, critique of the abstraction of lived experience from research concepts is important to consider (Hallett and Ventresca Citation2006; Lund Citation2012; Lok et al. Citation2017). For example, Lok et al.’s (Citation2017) critique of Zilber’s (Citation2002) study of an Israeli rape crisis centre highlights the value of a deeper methodological engagement with emotion, they assert ‘emotions do not figure expressly’ yet ‘emotions clearly animated the dialectical interplay of practices, actors and meanings, shaping how meanings were attached to practices’ (594). We therefore determined it was important to explore participants’ accounts of working in the teaching profession and to ask directly about the emotions experienced. Emotions towards practices were also explored, for example: ‘I understand there is a WomenEd Twitter policy regarding how to respond to harassment online; how do you feel about this policy?’. Attention to emotion in observational data proceeded either through explicit reference to emotions by members, or via field notes made by the first author – who captured instances when she was moved and affected by the emotions experienced via participating in the events, which could then be explored during interviews and via member checks (Gherardi Citation2019).

Data analysis

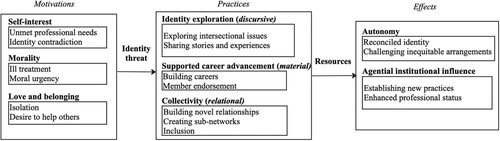

During analysis, we used a combination of NVivo’s manual coding functionality and visually mapping codes into the process diagram to generate the themes, illustrated in . In keeping with interpretive approaches (Creed, DeJordy, and Lok Citation2010), we moved iteratively between data, generated themes, and existing theory and began the process of coding before the completion of data collection. All generated themes were triangulated with observational and interview data. For clarity, it is useful to align our analytical method with what Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) define as ‘reflexive thematic analysis’ while noting deviations. An important difference in our method of thematic generation is that we used a process diagram to visually map themes and retrospectively group these themes into the theoretical dimensions proposed by Lawrence and Phillips’ (Citation2019). We conducted member checks which were used to discuss the themes generated by our analysis. Some themes were adapted during this process when they did not match with participants understanding of their work.

Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) suggest that thematic analysis is a wide-ranging approach which resides on a spectrum of more deductive and inductive reflexive approaches. The use of a process diagram acted as a deductive frame, through which, codes which did not fit into the categories of motivations, practices and effects, we excluded. Codes were grouped by considering whether they were best described as a motivation, practice, or effect and then used to generate themes. This process enabled a focus upon social-symbolic work at the exclusion of other phenomena, where social-symbolic work represent intentional and sustained change efforts and the practicalities of how these efforts operate. We found Lawrence and Phillips' (Citation2019) process diagram useful for conceptualising an emotion-informed account of the empirical setting. This is because emotions animate the cross-linkages of motivations, practices, and effects – for example, feelings of isolation can motivate practices of building relationships.

Following Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell (Citation2010), in addition to formal practices, we took an interest in informal practices, i.e. those practices which appeared spontaneous or unplanned, but which regularly occurred. We applied Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2019) definition of institutionalisation, that practices are institutionalised when they operate as self-policing ‘shared, social understanding’ (190), understanding that ‘all practices are indeed institutions’ to the extent they ‘involve a degree of institutionalisation which is independent of the size of the social group within which they are located’ (.219). We therefore understand the movements’ shared practices as institutionalised, irrespective of their diffusion more widely. Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2019) prompt consideration of how different forms of social-symbolic work are combined via: ‘sequencing, aligning and integrating’ (269). We considered the cross-linkages of motivations, practices and effects in determining the types of work.

Findings

This section presents the findings, focusing first upon the sub-practices of intersectional collaboration which are detailed in . A breakdown of each of the sub-practices is provided with exemplar data for each sub-practice in . In the last part of the findings section the motivations and effects of these practices are presented ( and ), illustrating themes and exemplar data. Each section indicates how the themes are grouped into the theoretical dimension of the process diagram by providing the dimension italicised in brackets.

Table 2. Practices of collectivity (the relational dimension).

Table 3. Practices of supported career advancement (the material dimension).

Table 4. Practices of identity exploration (the discursive dimension).

Table 5. Motivations.

Table 6. Effects (direct effects).

The practices of collectivity

The first set of practices to consider are the relational practices of ‘collectivity’, these relational practices form the backbone or ‘network’ through which other practices can then operate. These relational practices include forming sub-groups within the larger movement, within which novel relationships can be developed and maintained.

The practices of supported career advancement

The material dimension of these collective practices attends to the resources which network members require to advance their position in their employer organisations and to meet the challenges they face within their careers.

The practices of identity exploration

These practices constitute the discursive theoretical dimension and include collective practices through which members explore issues and share stories linked to their intersectional positionality.

Motivations and effects

Relating to motivations, illustrated in , there are three theoretical dimensions provided by Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2019), into which generated themes are grouped: (1) self-interest, (2) morality and (3) love and belonging. Within the ‘self-interest’ dimension, there are two themes: ‘unmet professional needs’, linked to participants’ challenges in their specific job roles, and ‘identity contradiction’ arising as a sense of discomfort or dissonance with a splitting of the self and values. Within the ‘morality’ dimension, are the themes ‘ill treatment’ and ‘moral urgency’, ill treatment refers to data in which participants describe upsetting experiences in relation to their motivation, while ‘moral urgency’ linked these experiences, or the experiences of others, to a sense of urgency to impact more systemic issues. The final category ‘love and belonging’ includes the themes of ‘isolation’ in which members describe their experiences of isolation as a motivator, and ‘desire to help others’, in which members express their felt responsibility to help others.

There are two theoretical dimensions which we provide in relation to effects: autonomy and agential institutional influence, as illustrated in and italicised in brackets. We suggest these dimensions fit into the ‘direct effects’ dimension of Lawrence and Phillips’ (Citation2019) process diagram, as the outcomes are all effects which members of the network hoped to achieve and have worked towards. The ‘indirect’ and ‘unintended’ effects are dimensions beyond the scope of the study, and we suggest could be further explored in future. The ‘reconciled identity’ theme represents statements by members in which they describe how WomenEd has enabled them to present a truer version of themselves within their work environments, and to hold a greater degree of self-insight or understanding. The ‘challenging inequitable arrangements’ theme refers to data in which members attribute their ability to challenge arrangements to their support from and involvement within WomenEd, while ‘establishing new practices’ refers to instances where tangible practice changes are described. Finally, ‘enhanced professional status’ refers to data in which members describe new jobs, qualifications and prestigious roles as a result of their engagement.

Discussion

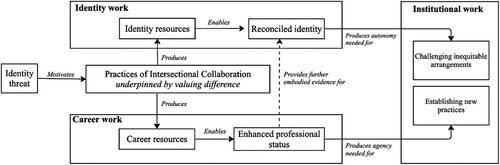

This section sets out a theoretical model for the form of collective leadership observed. The model advances understanding of power in relation to leadership by offering insights into the mechanism through which leadership is contested and reconceptualised. Drawing inspiration from Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2019), who discuss the possibility of aligning and integrating forms of social-symbolic work, three distinct processes are theorised: identity work, career work and institutional work, yet we caution against the assumption that these forms of work can be performed in isolation. The model illustrates that identity work and career work operate in parallel and are antecedent to institutional work, as depicted in . The proposition that these forms of work are unlikely to be separable is grounded in the belief that all three forms appear to be underpinned by the relational practices of collectivity. Collectivity is both constitutive of the relational network, and of the principles of organising via inclusion and embracing difference. The study thus provides a novel perspective on collective leadership, compelling us to contemplate how institutionalised relationships and roles contribute to leadership. We argue that the central locus of change lies in the ability to shift these relational networks, as this is where the resources for the effects of intersectional collaboration are derived.

Linking practices and effects

In we present our theoretical model of the integration of these three forms of work. Starting from the motivations on the left, we interpret the themes in (motivations) as posing an identity threat, which can be seen from the perspective of the three different themes generated in the analysis of motivations. The diagrams mid-section illustrates how the practices of identity exploration provide identity resources resulting in reconciled identity. In parallel, the career resources derived from the practices of supported career advancement enable enhanced professional status.

The dotted line connecting reconciled identity and enhanced professional status, builds upon Creed, Dejordy, and Lok’s (Citation2010), contribution which suggests ‘role claiming and role use’ enable participants to embody reconciled identities leading to shifts in autonomy and agency. We therefore suggest that these two processes are necessary for the possibility of institutional work in which these actors both experience the autonomy through which to challenge existing arrangements, and the agency to produce a change in their environment. In our model it is these actors’ legitimate professional status and reconciled identity which enables their influence. Our perspective thus contrasts with deviant or risk-based portraits of resistance and disruption (Lawrence and Buchanan Citation2017; Oyakawa, McKenna, and Han Citation2021). We suggest these risk-based accounts provide a one-sided view of risk which assumes actors engage in risk, yet fails to explain actor motivations in terms of risk, i.e. the risks associated with inaction. Our study shows that there are risks associated with inaction, namely the identity threat marginalised insiders experience as a motivator.

Concerning institutionalised norms, we emphasise that more work needs to be done to unpack the ways in which the practices of collectivity we observe might replace or subvert logics such as the ‘myth of meritocracy’ discussed by Amis, Mair, and Munir (Citation2020). However, we briefly explore the contrast here. A meritocratic logic might be understood to reproduce inequalities because it is assumed that opportunity is equally distributed. The relational arrangement of actors in a social network of influence in meritocratic institutions then reflects existing inequalities of opportunity, which are reinforcing. In contrast, an inclusive logic which acknowledges intersectional inequality assumes inequitable distribution of opportunity, and organising, therefore, proceeds by arranging actors to account for inequalities and to include diverse actors. It can then be seen that the introduction of logics of inequitable opportunity can reconfigure networks of influence in favour of marginalised groups.

An important contribution of our model is our application of Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2019) social-symbolic work to understanding endogenous shifts in autonomy and agency. Given the centrality of autonomy and agency to an understanding of power, our theorising responds to Allen’s (Citation2009) aforementioned critique in two important ways. Firstly, by emphasising collectivity and inclusion, the model is ‘capable of illuminating the intersectional and cross-cutting axes of power along lines of gender, race, class and sexuality’ (Allen Citation2009, 306). Secondly, by drawing upon both interpretivist and critical foundations, and using the concepts of ‘social-symbolic work’ and ‘social-symbolic objects’, the model takes account of the poststructuralist approach to power. In illuminating the power shifts produced by collective action, our model moves away from prior distinctions between ‘power-over’ and ‘power-to’ and provides a way of conceptualising Allen’s ‘power with’. To formalise this further, we suggest the following notions may be useful: (1) power work: social practices which are intentionally engaged in shaping power structures and flows, and indeed result in tangible shifts in autonomy and agency, and (2) power objects: the existing artefacts and categories which are taken-for-granted and pervasive, and which affect ‘the distribution of opportunities, benefits, and advantages within social systems’ (Lawrence and Phillips Citation2019, 25). Our findings indicate the integrated forms of identity work and career work observed constitute ‘power work’ because they produce shifts in autonomy and agency.

Further understanding of these social processes will likely have explanatory power for understanding social exclusion, and, moreover, the way to proceed to avoid reproducing inequalities (Amis, Mair, and Munir Citation2020). As Alvesson and Willmott (Citation2002) explain, ‘mechanisms and practices of control – rewards, leadership, division of labour, hierarchies, management accounting, etc – do not work ‘outside’ the individual’s quest(s) for self-definition(s), coherence(s) and meaning(s)’ (622). Several critical scholars have contributed to understanding the link between the ‘individual(s) quest for self-definitions’, identity and change efforts. Our work draws particularly upon Creed, Dejordy, and Lok’s (Citation2010) understandings of the relationship between identity, institutionalised roles, and agency, and Crenshaw’s (Citation1991) formative work on intersectionality. The notion of ‘power work’ indicates an interest in the forms of practical activity involved in promoting power shifts in favour of marginalised people. In the case of intersectional collaboration, ‘collaboration’ refers to coalitions between diverse actors. These actors have supported one another in their careers over time, while providing one another space to reflect upon challenging experiences in relation to their social identity and future aspirations.

Limitations and future directions

An important assumption of the social-symbolic work perspective is that practices are intentional and sustained within a particular context. Our findings do not presume the institutionalisation of these practices more widely at field level (as some institutional perspectives do), rather, these practices exist within and across the WomenEd movement, as supported by our ethnographic observation of their work. The unintentional and indirect effect of these practices are not explored, and so future research may also take an interest in these aspects. Furthermore, the study was limited in its scope to provide detailed accounts of an individual members’ project as it unfolded, which may facilitate understanding of whether the resolution of ‘identity threat’ might be an ‘ongoing reflexive accomplishment’ (Creed, Dejordy, and Lok Citation2010, 1341), rather than a final resolution.

In the second part of the findings section, we moved to consider the motivations and effects of the observed practices. We suggest these aspects may help us to build a conception of leadership as a social-symbolic object, or ‘power object’, by considering how these practices can also be linked to broader political, moral, or ethical phenomena. Conceiving of leadership as a power object would mean to regard the ways in which ‘leadership’ invokes taken-for-granted assumptions which operate pervasively and affect the distribution of opportunities and resources. For example:

the narrative that leadership has to be, um aggressive, that you have to be bossy to be a leader, that you have to be a certain kind of person … (fieldnotes, 2021)

Conclusion

A lack of studies focusing on the practices of solidarity building and feminist organising contribute to significant gaps in our understanding of emancipatory change processes. The ethnographic research strategy adopted by this study provides detailed observations of intersectional organising, facilitating a rich picture of the motivations, practices and effects of this work. The study builds upon understanding of how institutionalised representations of leadership exclude and marginalise particular intersections of social identity. The study finds that shifting such representations requires identity work, and embodying these identities and legitimising them requires career work. The model developed indicates how practices of ‘collectivity’, underpinned by intersectionality and inclusion, enable other processes of identity work and career work in this context, leading to shifts in autonomy and agency. Together these practices of ‘intersectional collaboration’ constitute a new form of collective leadership for social change, and provide a glimpse into the alternative forms of organising which may be mobilised to address ‘Grand Challenges’. The study deepens understanding of collective leadership as a form of collective power, or ‘power with’, and nuances the practical activity associated with driving change, ‘power work’. The shifts produced are illustrative of how change can occur for marginalised insiders, and we hope to spark further interest in this important area of research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rosie Boparai

Rosie Boparai: With a background in physics and computer science, Rosie is an experienced leader and educator, specialising in building communities and digital networks and in leading computer science, mathematics and physics pedagogy. She is a graduate of the MSt in social innovation at the University of Cambridge, where she focused upon teacher-led organising as a driver for innovation and systems change. Her present PhD research is located in the department of strategy and marketing at The Open University, where she is researching a global organisation navigating change, with a focus on tensions in strategic decision making. Rosie is also a board member of Journal of Physics Education, and a Graduate Research Associate at the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation.

Michelle Darlington

Michelle Darlington: Michelle is Head of Knowledge Transfer at the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation and holds a PhD in drawing and cognitive psychology. Her work applies cognitive principles to education, facilitation and research methods. She has written and edited academic publications on drawing, visual literacy arts integration, and social innovation. She is co-founder of the Thinking Through Drawing project, a research network and professional development provider that focuses on creativity and visual literacy in education and research.

References

- Acker, J. 1990. “Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations.” Gender & Society 4 (2): 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002.

- Acker, J. 2006. “Inequality Regimes: Gender, Class, and Race in Organizations.” Gender & Society 20 (4): 441–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243206289499.

- Acker, J. 2012. “Gendered Organizations and Intersectionality: Problems and Possibilities.” An International Journal 31 (3): 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610151211209072.

- Allen, A. 2009. “Gender and Power.” In The SAGE Handbook of Power. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom, edited by S. Clegg and M. Haugaard, 293–309. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857021014.

- Alvesson, M., and K. L. Ashcraft. 2010. “Critical Methodology in Management and Organisational Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, edited by D. A. Buchanan and A. Bryman, 61–77. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Alvesson, M., and Hugh Willmott, eds. 1992. Critical Management Studies, 230. Newbury Park, London: Sage.

- Alvesson, M., and H. Willmott. 2002. “Identity Regulation as Organizational Control: Producing the Appropriate Individual.” Journal of Management Studies 39 (5): 619–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00305.

- Amis, J. M., J. Mair, and K. A. Munir. 2020. “The Organizational Reproduction of Inequality.” Academy of Management Annals 14 (1): 195–230. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2017.0033.

- Bell, E., Susan Meriläinen, Scott Taylor, and Janne Tienari. 2019. “‘Time’s up! Feminist Theory and Activism Meets Organization Studies’.” Human Relations 72 (1): 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718790067.

- Bell, E., and E. Wray-Bliss. 2009. “Research Ethics: Regulations and Responsibilities.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, edited by D. A. Buchanan and A. Bryman, 77–92. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Blackmore, J. 2013. “A Feminist Critical Perspective on Educational Leadership.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 16 (2): 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2012.754057.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021. “One Size Fits all? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. International Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Butler, J. 2006. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge (Routledge classics).

- Calas, M., and L. Smircich. 2010. “Feminist Perspectives on Gender in Organizational Research: What is and is Yet to be.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, edited by D. A. Buchanan and A. Bryman, 246–269. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Creed, W. E. D., R. Dejordy, and J. Lok. 2010. “Being the Change: Resolving Institutional Contradiction Through Identity Work.” Academy of Management Journal 53 (6): 1336–1364. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318357.

- Creed, W. E. D., Barbara Gray, Markus A. Höllerer, Charlotte M. Karam, and Trish Reay. 2022. “Organizing for Social and Institutional Change in Response to Disruption, Division, and Displacement: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Organization Studies 43 (10): 1535–1557. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221122237.

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Featherstone, K., and V. Porritt. (eds) 2021. Being 10% Braver. London: CORWIN, a Sage.

- Fitzgerald, T., and H. M. Gunter. 2008. “Contesting the Orthodoxy of Teacher Leadership.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 11 (4): 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120802317883.

- Fotaki, M., and A. Pullen. 2023. “Feminist Theories and Activist Practices in Organization Studies.” Organization Studies 45 (4): 593–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406231209861.

- Gherardi, S. 2019. “Theorizing Affective Ethnography for Organization Studies.” Organization 26 (6): 741–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508418805285.

- Gray, B. 2023. “A Call for Activist Scholarship in Organizational Theorizing.” Journal of Management Inquiry 32 (3): 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/10564926231169160.

- Hallett, T., and M. J. Ventresca. 2006. “Inhabited Institutions: Social Interactions and Organizational Forms in Gouldner’s ‘Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy.” Theory and Society 35 (2): 213–236.

- Harris, A. 2013. “Distributed Leadership: Friend or Foe?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 41 (5): 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213497635.

- Harris, A., M. Jones, and N. Ismail. 2022. “Distributed Leadership: Taking a Retrospective and Contemporary View of the Evidence Base.” School Leadership & Management 42 (5): 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2022.2109620.

- Heucher, K., Elisa Alt, Sara Soderstrom, Maureen Scully, and Ante Glavas. 2024. “Catalyzing Action on Social and Environmental Challenges: An Integrative Review of Insider Social Change Agents.” Academy of Management Annals 18 (1): 295–347. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2022.0205.

- Jensen, L. X., Margaret Bearman, David Boud, and Flemming Konradsen. 2022. “Digital Ethnography in Higher Education Teaching and Learning—A Methodological Review.” Higher Education 84 (5): 1143–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00838-4.

- Lardner, Y. 2022. “Leadership, Race and Positive Professional Identity: Exploring the Black Experience.” In Tell me Something Good: Enabling Conditions for Positive Individual Outcomes Symposium, Creating a Better World Together, 82nd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management (AOM). Seattle, Washington, USA, 5-9 August 2022.

- Lawrence, T. B., and S. Buchanan. 2017. “Power, Institutions and Organizations.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. 55 City Road, edited by R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. Lawrence, and R. Meyer, 477–506. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526415066.

- Lawrence, T. B., and N. Phillips. 2019. Constructing Organizational Life: How Social-Symbolic Work Shapes Selves, Organizations, and Institutions. 1st ed., 1–394. Oxford University Press.

- Lok, J., W. E. D. Creed, R. DeJordy, M. Voronov. 2017. “Living Institutions: Bringing Emotions Into Organizational Institutionalism.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, edited by R. Greenwood, 591–620. London: SAGE publications..

- Lund, R. 2012. “Publishing to Become an ‘Ideal Academic’: An Institutional Ethnography and a Feminist Critique.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 28 (3): 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2012.05.003.

- Mackay, F., M. Kenny, and L. Chappell. 2010. “New Institutionalism Through a Gender Lens: Towards a Feminist Institutionalism?” International Political Science Review 31 (5): 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512110388788.

- McCluney, C. L., and V. C. Rabelo. 2019. “‘Conditions of Visibility: An Intersectional Examination of Black Women’s Belongingness and Distinctiveness at Work’.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 113:143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.09.008.

- Mifsud, D. 2017. “Distribution Dilemmas: Exploring the Presence of a Tension Between Democracy and Autocracy Within a Distributed Leadership Scenario.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 45 (6): 978–1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216653974.

- Mulholland, M, Natalie Arnett, Emma Knights, and Vivienne Porritt. 2021. Closing the Gender Pay Gap in Education: A Leadership Imperative. White Paper. https://www.nga.org.uk/Knowledge-Centre/research/Closing-the-gender-pay-gap-in-education.aspx.

- Novicevic, Milorad M., John H. Humphreys, Ifeoluwa T. Popoola, Stephen Poor, Robert Gigliotti, Brandon Randolph-Seng. 2017. Collective Leadership as Institutional Work: Interpreting Evidence from Mound Bayou.” Leadership 13: 590–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715016642510.

- Ospina, S. M., and E. G. Foldy. 2016. “Collective Dimensions of Leadership.” In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, edited by A. Farazmand, 1–6. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_2202-1.

- Ospina, S. M., Erica Gabrielle Foldy, Gail T Fairhurst, and Brad Jackson. 2020. “Collective Dimensions of Leadership: Connecting Theory and Method.” Human Relations 73 (4): 441–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719899714.

- Oyakawa, M., E. McKenna, and H. Han. 2021. “Habits of Courage: Reconceptualizing Risk in Social Movement Organizing.” Journal of Community Psychology 49 (8): 3101–3121. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22355.

- Porritt, V., and K. Featherstone (eds). 2019. 10% Braver: Inspiring Women to Lead Education. 1st edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Prasad, P., and A. Prasad. 2000. “Stretching the Iron Cage: The Constitution and Implications of Routine Workplace Resistance.” Organization Science 11 (4): 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.4.387.14597.

- Rodriguez, J. K., Evangelina Holvino, Joyce K. Fletcher, and Stella M. Nkomo. 2016. “The Theory and Praxis of Intersectionality in Work and Organisations: Where Do We Go from Here?.” Gender, Work & Organization 23 (3): 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12131.

- Smets, M., T. Morris, and R. Greenwood. 2012. “From Practice to Field: A Multilevel Model of Practice-Driven Institutional Change.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (4): 877–904. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0013.

- Smolović Jones, S., N. Winchester, and C. Clarke. 2021. “‘Feminist Solidarity Building as Embodied Agonism: An Ethnographic Account of a Protest Movement.” Gender, Work & Organization 28 (3): 917–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12453.

- Spillane, J. P. 2005. “Distributed Leadership.” The Educational Forum 69 (2): 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720508984678.

- Spillane, J. P., R. Halverson, and J. B. Diamond. 2001. “Investigating School Leadership Practice: A Distributed Perspective.” Educational Researcher 30 (3): 23–28. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030003023.

- Stott, N., and M. Fava. 2019. “Challenging Racialized Institutions: A History of Black and Minority Ethnic Housing Associations in England Between 1948 and 2018.” Journal of Management History 26 (3): 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMH-08-2019-0053.

- Styhre, A. 2014. “‘Gender Equality as Institutional Work: The Case of the Church of Sweden: Gender Equality as Institutional Work.” Gender, Work & Organization 21 (2): 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12024.

- Thomas, R., and A. Davies. 2005. “What Have the Feminists Done for Us? Feminist Theory and Organizational Resistance.” Organization 12 (5): 711–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508405055945.

- Tsoukas, H. 2009. “Craving for Generality and Small-N Studies: A Wittgensteinian Approach Towards the Epistemology of the Particular in Organization and Management Studies.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, edited by D. A. Buchanan and A. Bryman, 285–301. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- West, C., and D. H. Zimmerman. 1987. “Doing Gender.” Gender & Society 1 (2): 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002.

- WomenEd. 2020. WomenEd - About us, WomenED. Accessed December 5, 2020. https://www.womened.org/aboutus.

- Yarrow, E., and K. Johnston. 2022. “Athena SWAN: “Institutional Peacocking” in the Neoliberal University.” Gender, Work & Organization 30 (3): 757–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12941.

- Zilber, T. B. 2002. “Institutionization as an Interplay Between Actions, Meanings and Actors: The Case of a Rape Crisis Center in Israel.” Academy of Management Journal 45 (1): 234–254. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069294.