ABSTRACT

As technical and vocational education and training (TVET) continue to occupy a prominent position in Africa’s development, addressing the growing concerns about young women’s under-participation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)-related TVET has become urgent. This paper draws on the critical capability approach of vocational education and training (CCA-VET) to critique the TVET policy discourse on the participation of girls and women in STEM-related TVET. The paper employed the practical argumentation approach, a critical discourse analysis approach to achieve the paper’s aims. The paper’s central thesis is that for education policies to transform young women’s under-participation in STEM-related TVET, it is urgent to move beyond human rights-based, and human capital approaches to adopt a comprehensive theoretical approach, such as the critical capabilities approach. The paper concludes that breaking this hegemony of human rights and human capital approaches to TVET policy can be achieved by re-conceptualising TVET policy discourses. The re-conceptualisation of TVET policy discourses can be achieved by admitting the critiques of these dominant theories that underpin most TVET policies and then adopting the CCA-VET as a better alternative approach to framing TVET policies.

Introduction

Globally it has become urgent to address the growing concerns about young women’s under-participation in Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (STEM)-related Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) (henceforth STEM-related TVET) (Tikly Citation2020; Mcdool and Morris Citation2020; UNESCO-UNEVOC Citation2019). In Ghana, like many other emerging economies, the problem begins at the upper secondary education level when education pathway selection and subject specialisation begin (Tikly et al. Citation2018; CAMFED Ghana Citation2012). Available administrative data on Ghana’s upper secondary school enrolment in the 2017/2018 academic year suggests that only 1,675 young women enrolled in STEM-related TVET courses in technical institutes, which was less than 3% of the total 57,746 enrolments recorded (Ministry of Education Citation2017).

The under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET needs urgent attention among TVET scholars, policymakers, and practitioners. Indeed, ignoring the problem is detrimental to making TVET an inclusive development approach. Recently, UNESCO-UNEVOC (Citation2019) emphasised that “policy frameworks, societal attitudes, and the nature of STEM in the classroom and workplace affect females’ mindset to pursue education and training in STEM subjects” (p. 1). For example, a substantial body of research has shown that child marriage, poverty, early pregnancy, child labour, gender-based violence, discrimination, family responsibilities, stigmatisation, and stereotypes limit girls’ and women’s access to STEM education (Atsu and Lartey Citation2018). Several studies have examined the under-participation of young women in education, with some focusing on the young women’s under-participation in STEM-related TVET (e.g. Atsu and Lartey Citation2018; Ngugi Citation2017; Stoet and Geary Citation2018)

However, there has been little discussion on how the inadequacies in education policy discourses, such as the deficit discourses concerning young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET, contribute to young women’s under-representation in STEM-related TVET. This paper aims to contribute to the current debate concerning inequalities in TVET, specifically the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET. The article examines the potential consequences of Ghana’s current education policy discourses on the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET. For TVET policies to adequately transform young women’s under-participation in STEM-related TVET, education policy discourse needs to move beyond human rights-based, and human capital approaches to adopt a comprehensive theoretical approach, such as the critical capability approach.

This paper draws on the critical capability approach of VET (CCA-VET) (Bonvin Citation2019; McGrath et al. Citation2020) to review TVET policy discourses in Ghana’s Education Strategic Plan 2018–2030 concerning young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET. Also, the paper discusses the provision of upper secondary STEM-related TVET education in Ghana. Afterwards, there is an analysis of Ghana’s current education policies and practices concerning upper secondary education and STEM-related education. The paper then proceeds to discuss the CCA-VET as the paper’s theoretical framework and the justifications for employing the practical argumentation approach of critical discourse analysis for the paper's analysis. Next, the paper presents findings from the critical discourse analysis (Fairclough Citation2013). The concluding section proposes using the CCA-VET to re-conceptualise Ghana’s TVET policy discourses since it presents a better alternative approach to increase young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET.

STEM-related TVET provision in Ghana

As of the 2017/2018 academic year, there were 47 Ghana Education Service (GES) upper secondary technical institutes, with a projected increase in student enrolment to 741,159 by the 2020/2021 academic year (Ministry of Education Citation2017). Technical institutes are all public pure TVET schools that the Ghana Education Service manages. Technical institutes offer specialised TVET programmes such as mechanical engineering, electrical engineering and automation, catering and hospitality, business, printing, computer hardware technology, and fashion design, in addition to general academic courses: mathematics, social studies, general science, and English language (Arthur-Mensah and Alagaraja Citation2013). Technical institute learners engage in school-based TVET for three years, and after successful examinations in theory and practice, they receive certifications recognised by higher education institutions and employers.

In many cases, STEM provision in technical institutes applies science through technology and engineering-focused programmes. Currently 47 technical institutes across Ghana offer about 22 STEM programmes. Some of these STEM programmes include autobody works, motor vehicle engineering, welding, and fabrication technology, diesel-mechanical/heavy engine, heavy-duty auto-mobile, industrial mechanics mechanical, engineering technology, minor engine repair, electrical engineering technology, and electrical machine/motor rewinding. Others are agricultural mechanisation technology, refrigeration & air-conditioning technology, electronics engineering, computer hardware technology, information technology, computer networking, software development, database management, digital designing technology, plumbing and gas fitting technology, building construction technology, and architectural drafting. It is important to note that the norm is for each technical institute to offer at least four STEM-related courses but not all.

The expectation is for technical institutes to have workshops for STEM practical lessons. Evidence shows that most schools have STEM workshops. However, over 50% of these school-based STEM workshops lack the necessary modern technological tools, materials, and machinery for practical lessons (Darvas and Palmer Citation2014; Wojcichowsky Citation2016; Amegah Citation2021). In the study by Amegah (Citation2021) on employer engagement in technical institutes in Ghana, all headteachers interviewed complained about inadequate machinery, tools, and materials deemed necessary for students to engage with employers and international development agencies. Over 90% of technical institutes have developed institutional strategies to complement practical-based learning in technical institutes. For instance, all three technical schools studied employed different strategies for practical-based learning. One of the schools was innovatively piloting the German dual system with local community-based industries for learners to assess industry space where tools, machines, and materials are available (Amegah Citation2021).

STEM-related TVET education policy in Ghana

Ghana’s advocacy for more girls and women to study STEM-related TVET programmes is well known (UNESCO-UIS Citation2018; Ministry of Education Citation2018a; Tembon and Fort Citation2008). The first clue in recent times is the inclusion of public upper secondary technical institutes in the Free Senior High School (FSHS) policy introduced in September 2017 (Ministry of Education Citation2018a). The policy was implemented to achieve Article 25(1)(b) of the 1992 Constitution that states: secondary education in its different forms, including TVET, shall be made generally available and accessible to all by every appropriate means, and in particular, by the progressive introduction of free education (CAMFED Ghana Citation2012; Dadzie, Fumey, and Namara Citation2020). The removal of all forms of fees associated with TVET, such as tuition fees, materials fees, tools fees, and feeding fees empirically and anecdotally known to be a significant barrier to girls’ education, especially in STEM-related TVET, points to the Ghana government’s drive for girls’ participation in STEM-related TVET (Ministry of Education Citation2018a). The FSHS policy affords young people who pass the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) free admission to public senior high schools (SHS) and Ghana Education Service (GES) TVET institutions (Ministry of Education, 2018). The FSHS policy aims to increase equitable access to public upper secondary education, emphasising TVET for all Ghanaian children and tracking students’ transition from junior high school (JHS) to senior high school. Notably, the objective and strategies for senior secondary and TVET education under the FSHS policy state the need to ‘increase enrolment of females and learners with special needs in male-dominated occupational areas and disabilities and invest in improving learning outcomes for girls in all subjects, especially STEM’ (Ministry of Education 2018, p. 36, 41).

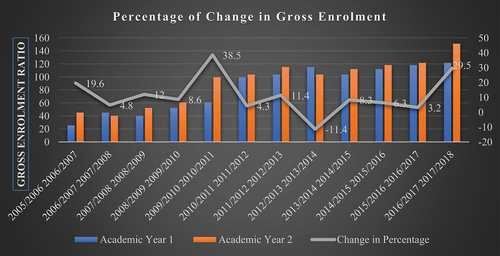

Generally, the FSHS policy has increased gross enrolment in Ghana’s public upper secondary education (Ministry of Education, 2018). Data from the Education Management Information System (EMIS) shows that between the 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 academic years, the gross enrolment rate increased by 29.5% (9.8% for public senior high schools and 19.7% for GES TVET institutions). A graphical representation of enrolment over fourteen academic years shows that apart from a 38.5% increment between the 2009/2010 and 2010/2011 academic years, the 29.5% increment between the 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 academic years of the beginning of the FSHS policy is one of the highest enrolment increments since the last 14 academic years. shows the percentage change in gross enrolment from 2005/2006 academic year to 2017/2018 academic year.

Figure 1. Percentage change in gross enrolment rates from 2005 to 2018.

Therefore, there is a noticeable drive for infrastructural development in education, especially TVET to meet the increased demand. For instance, in 2019, the government announced 500 million euros to fund the development of the TVET. The focus was to expand and to upgrad workshops and laboratories in 10 technical universities, two polytechnics, seventeen technical institutes, and thirty-five TVET schools (Ghana Business News Citation2019). In another policy announcement, the Ministry of Education announced 32 modern TVET institutions across Ghana to increase access and quality (Ekuful Citation2019). The extensive focus on infrastructure is essential; however, it limits the investment in other TVET sector problems, such as advancing TVET learners. However, anecdotally, the FSHS policy and it associated infrastructural development drive appears to be directly or indirectly limiting the government’s capacity to provide other necessary elements such as conducive learning environments, relevant curricula, and quality teachers needed to achieve quality education for all.

Finally, the government of Ghana, international development partners, and NGOs continue to initiate interventions and policies to increase females’ participation in STEM. The Women in Technical Education Department (WITED) is an example of a Ghanaian government policy initiative. The department supports young women in technical education through scholarships and mentorship (Wojcichowsky Citation2016; Tikly Citation2020). A more recent intervention is the Ghana Internship and Mentoring Programme by the Millennium Development Authority (MiDA). The initiative’s objective is to support females pursuing STEM-related TVET programmes to obtain practical skills relevant to Ghana’s power sector (Ministry of Gender Children and Social Protection Citation2018).

A second example is the MyTVET Campaign, where celebrated Ghanaians as are employed by the Commission for TVET (CTVET) as TVET ambassadors with the aim to make TVET attractive. For instance, on the CTVET Facebook page and YouTube channel, there are videos of MyTVET ambassadors talking about the relevance of women in STEM-related TVET careers such as construction, electrical engineering, and mechanical engineering. (COTVET Citation2020) A similar initiative is the Ghana Skills Development Initiative (GSDI). The GSDI encourages young women to choose STEM-related TVET courses through national skills competitions, junior high school TVET clubs, career guidance and counselling, TVET ambassadors, and role models. Despite these policies and initiatives, the overall concern is that young women’s enrolment in STEM-related TVET remains significantly low.

Young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET

Human rights-based approach is a standard theoretical approach to conceptualising the relevance of young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET. The global agenda to use TVET as a transformational pathway to achieve gender parity emphasises why the participation of young women in STEM-related TVET at all levels is non-negotiable (UNSECO Citation2017; Wingate Citation2017; Hoffmann-Barthes, Nair, and Malpede Citation1999; UNESCO Citation2015; Zancajo and Valiente Citation2019). Moreover, improving the participation of young women in STEM-related TVET is a global acknowledgement that every young person’s human right to access different forms of education is the responsibility of nations and a means to render inclusive education systems that aspire to achieve universalistic lifelong learning goals (Zancajo and Valiente Citation2019; DFID Citation2005; UNESCO Citation2015).

However, one challenge with the human rights-based approach to young women in STEM-related TVET is the narrow aim to increase young women’s enrolment numbers to improve gender parity. The target to increase gender parity could be driving the unfortunate description of STEM-related TVET programmes along gender lines. It is common to see descriptors such as ‘traditionally male-dominated programmes and male-dominated instead of STEM-related TVET courses throughout the literature (see Bannikova and Kemmet Citation2019; Bannikova, Baliasov, and Kemmet Citation2018; Buehren and Van Salisbury Citation2017; Misola Citation2010). Some scholars argue that using these descriptors does not contribute to the transformational role of TVET (Morgan Citation2013; Atsu and Lartey Citation2018). The concern is that overemphasising gender parity in STEM-related TVET from a human rights-based approach can potentially lead to the neglect of other relevant of quality education elements such as retention, transitions, and the holistic flourishing of young women STEM-related TVET.

Nonetheless, as the debate on girls’ and women’s participation in TVET continues to broaden and evolve, the discourse is beginning to change. The discourse is redirected to focus on the essence of STEM-related courses in TVET, not their gender representations and participation. For instance, in an international report on young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET courses, the author operationalises STEM-related TVET as ‘TVET programmes that aim to qualify students to proceed to occupations where STEM skills are needed’ instead of using male-dominated courses (Tikly Citation2020, 11). The report broadly classified courses in educational fields such as natural sciences, mathematics, and statistics: information and communication technologies; engineering, manufacturing, and construction: agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and veterinary as STEM-related TVET programmes (Tikly Citation2020).

The growing recognition of TVET in global education development plans such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 and 8 has stimulated global debates about the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET (UNESCO-UNEVOC Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2016; Tikly Citation2020). These renewed debates have centred on the critical need for the relevance of TVET for young people, including young women, to move beyond the neo-economic perspectives such as productivism and the human capital approach (Tikly Citation2013b; Tikly et al. Citation2018; McGrath et al. Citation2020; Powell Citation2012). The past two decades have seen neo-economic orthodoxy dominate the theoretical accounts of TVET in several policy discourses of international organisations such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the World Bank (UNESCO-UIS Citation2006; Zancajo and Valiente Citation2019; Arthur-Mensah and Alagaraja Citation2018). Typically, the ILO and the World Bank have primarily approached TVET for development from human capital, productivity, and economic gains perspectives (Zancajo and Valiente Citation2019; UNESCO-UIS Citation2006; Tikly Citation2020). The drive for global competitiveness, productivity, and economic growth has become a common argument most international organisations, local policies, and some TVET scholars advance as reasons for increasing young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET. For instance, Mongolkhatan and Enkhtuvshin (Citation2015) argue that TVET’s capacity to transform education, labour market approaches, countries’ economic development and human capital needs are why tapping young women’s potential in STEM-related TVET is essential. Ngugi (Citation2017) adds that girls’ and women’s participation in TVET enhances social inclusion and their participation in STEM-related TVET is essential to the economic development of Kenya. Dasgupta and Stout (Citation2014) also add that STEM innovations are vital for American economic competitiveness, national security, and quality of life, making it crucial to prepared girls and women to participate in STEM innovations adequately. For Dasgupta and Stout (Citation2014), women make up 50% of the American population and 50% of the American college population; therefore, the under-participation of girls and women in STEM is untapped human capital that can enhance the STEM workforce to create the economic growth and competitiveness of America. Finally, for other scholars like Makgato (Citation2019), the technological revolution, digitalisation, and industrialisation make it critical to increase young women’s access to STEM education for countries economic growth and global competitiveness.

Nevertheless, the human capital and productivism perspectives have several serious drawbacks (Anderson Citation2008; Ngcwangu Citation2019; Winch Citation2013). Critics argue that the dominance of the productivism and human capital approaches in international development agendas for TVET and education as a whole present a deficit discourse, where for instance, the discourse frames ‘women as a group who need to catch up on certain skills to become more active in development’ (Aikman et al. Citation2016, 314). McGrath (Citation2012) acknowledges the significance of work, which is one core component of the human capital and productivism approaches to VET but challenges these approaches to TVET for development by pointing out their theoretical and practical weakness. Three of McGrath’s theoretical and practical agruments against human capital and productivism are salient to the current paper. First, his argument that human capital approach is very individualistic in its assumptions regarding its chief goal of employability, where the focus is immediate short-term employability rather than lifelong processes. Second, his argument that the focus on work as paid employment has dire gender consequences that cannot be ignored and third, the focus on human capital underestimates the wider questions of preparation for the good life, ignoring capabilities in particular. These arguments prove that limiting TVET for development to productivity and human capital agenda is unsustainable in the face of major global challenges such as climate change (McGrath Citation2012, 625). The discussions so far paint a picture that shows that the human rights-based approach, the human capital approach, and the productivism approach as arguments for increasing young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET have some merit. Nevertheless, these approaches are not holistic to achieve sustainable policies and systems that ensure that young women have equal opportunities to participate in STEM-related TVET. Therefore, critics of the human capital and the productivism approaches argue for the human development and capability to be the central approaches to TVET for development, where issues of young women in STEM-related TVET are of relevance (McGrath Citation2012; McGrath et al. Citation2019; Pantea Citation2019; Aikman and Robinson-Pant Citation2016; Tikly Citation2013a; Allais Citation2012).

Drawing on seminal works on human development, social justice, and capabilities by Sen (Citation1999), Nussbaum (Citation2000), and Sen (Citation2009), critics of the human capital approach to TVET argue for TVET policies that do not narrow the focus of development to human capital and economic outcomes. These scholars propose a critical-capability approach to TVET with the argument for the expansion of the ‘TVET for development agenda’ to include the ‘agency freedom’ of VET learners; their voices and flourishing which are crucial to economic productivity and competitiveness of countries (Tikly Citation2013a; Powell Citation2012; Powell and McGrath Citation2014; McGrath Citation2012; McGrath et al. Citation2020). Zancajo and Valiente (Citation2019) add that a new transformative role of TVET under the CCA-VET framework is for TVET policies ‘to expand the actual freedom of learners to pursue their life projects’ (p. 582). For example, in a study to examine aspirations, agency, and well-being among young women in technical and vocational schools in rural Tanzania, DeJaeghere (Citation2016) conceptualises her work within the capability approach. She argues that ‘using a capability approach to analyse young women’s educational and livelihood aspirations allows us to analyse what they value for themselves and others over time’ (p. 250). Watson and Jeffrey (Citation2007) add that to ‘increase the diversity in STEM education, policies and scholars need to acknowledge the complex interactions among the development of self-identity, cognitive capabilities, and occupational choice’ (p. 25).

Conceptual framework and methodology

Towards a critical capability approach of VET

Ngcwangu (Citation2019) argues that the new capabilities perspective of VET provides a humanising discourse that is mostly missing in TVET policies. The recent VET scholarly discourse is shifting beyond the productivism outcomes to include the dimension of VET playing a human development role, where the realisation of the capabilities of TVET learners is crucial (Bonvin Citation2019; Powell and McGrath Citation2014; Powell Citation2012; McGrath Citation2012; McGrath et al. Citation2020; Ngcwangu Citation2019; Tikly Citation2013a). McGrath et al. (Citation2020) explained that the new transformative role of VET needs to become an essential underpinning of VET policies and practices and this new transformative role can propel societal change through ‘human flourishing across economic, environmental and social domains’ (p .2). The new perspective is what some VET scholars conceptualise as the ritical Capability Approach of VET (McGrath et al. Citation2020; McGrath Citation2012).

The CCA-VET draws on human development and capability arguments that focuses on individual’s opportunities to choose a combination of functions with the freedom to use them or not use them (Alkire and Deneulin Citation2009; Sen Citation1999; Nussbaum Citation2016; Robeyns Citation2016; Sen Citation2005). In Sen’s view, resources are insufficient to determine a just distribution of functions, therefore, individuals should have the abilities and opportunities to convert resources into functioning which can be personally, socially, or environmentally valuable (Sen Citation2009). Nussbaum (Citation2000), draws on the human development perspective to make a case for girls’ and women’s flourishing by stating that we need the capability perspective to provide special attention and aid women to develop girl's and women’s well-being.In the case of this paper, Sen's arguement will translate into ensuring the young women are provided with all the attention and have opportunities to value STEM-related TVET opportunities.

Method

Critical discourse analysis (CDA): practical argumentation approach

The practical argumentation approach allows problematising Ghana’s TVET policy to propose the re-conceptualisation of TVET policy discourses to increase young women in STEM-related TVET. The article draws on the CCA-VET to critically analyse the constructed policy discourses that concern young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET in the Education Strategic Plan (ESP) 2018–2030 (the most current education policy plan for Ghana). The ESP 2018–2030 captures the FSHS policy and the current TVET development plan and theory of change. One primary aim of the TVET development plan is to increase young women's participation in STEM-related TVET. The practical argumentation approch as a form of critical discourse analysis for this article provides an opportunity to suggest a more critical alternative transformative discourse that can advance a transformative change (Fairclough Citation2013, Citation2012; Graham Citation2018).

First, this paper conceptualises education policy as a discourse to analyse Ghana’s education policy. Some scholars have used a social construction process to understand policy design (Ball Citation1990; Ingram and Schneider Citation1997; Ingram and Smith Citation1997; Schneider and Sidney Citation2009). Ball argues for power and knowledge relationships as two educational policy sides (Ball Citation1990). He explains that the power and knowledge of education policy as ‘discourse concerns what can be said: thought and who can speak, when, where, and with what authority’ (Ball Citation1990, 17). Besides, Ball (Citation1990) argues that policy as discourse expresses ‘meanings and social relationships which constitute both subjectivity and power relationships’ (p. 17). He also adds that the notion of discourse is fundamental to the argument that policy concerns the ‘authoritative allocation of values, operational statement of values and statement of prescriptive intent’ (p. 3). I contend that the notion of policy as a discourse in this article concerns how policy actors conceptualise the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET through policy enactment, which translates into structural constraints and policy constraints that perpetuates the realities of the under-participation of yougn women in STEM-related TVET. On the one hand, the paper further argues that, in the face of these deficit discourses, incredibly the few young women who participate in STEM-related TVET, are using their capabilities and agencies to navigate these constraints and have shown that young women are capable and not a group that needs to catch-up.

The critique of ESP 2018–2030 is based on the practical argumentation analysis proposed by Fairclough (Citation2013; Citation2012). The practical argumentation assessment of policy discourses conceptualises policy from a problem-solution perspective, where policies are presuppose to provide practical solutions to identified public problems. The practical argumentation analysis consists of five elements: a value premise, a goal premise, a circumstantial premise, a means – goal premise, and a claim (or conclusion) (Fairclough Citation2012). Fairclough (Citation2012) explains that the circumstantial premise concerns the representations and problematisation of existing states of affairs in particular ways. The goal premise aspect relates to the achievement of potential desirable alternatives to future states of the affairs that can realise the values expressed in education policies. The value premise concerns the underlying values that inform the motivation to raise the concerns expressed in the circumstantial premise and the motives that drive the proposed means-goal to change the circumstantial premise. The means-goal premise concerns a conditional assumption suggesting that if policy actors take a set prescribed action, these actions become the means that can change the problem for desirable change and goals. The final premise: claim or conclusion points to the practice of a specific course of action to achieve the desired goals (Fairclough Citation2012).

The CDA used to scrutinise the TVET policy discourses in the ESP 2018–2030 involved seven primary processes. The first and second processes involved identifying and reading policy documents that concerned TVET. After the location and initial reading, there is another set reading to identify and explore the background of the documents. The next step was to use the different practical argumentation commitments presented in the policy documents to identify overarching themes and use a colour coding scheme of primary colours to highlight specific text extracts that were premises of interest. The circumstantial premises were identified with red, the value premise with green, the goal premise with yellow, and the means-goal premise with blue. There was a need to structure the text to enable proper scrutiny. Therefore, the next step was to copy and paste the selected text into a tabular format according to the four main premises. After the tabular presentation of the initial text, the next step was to critique the discourse concerning the problem-solution approach adopted in the policy document in connection with the realities of the problem and how the discourses may or may not address the problem adequately (Mullet Citation2018). The final stage was to draw on the existing literature to discuss and interpret the discourse used in these policy documents. The CDA in this work generally followed the General Analytical Framework for CDA proposed by Mullet (Citation2018).

Findings and discussion

This policy document critiqued was the current national education strategic plan, the ESP 2018–2030. During his tenure, the FSHS policy was implemented in September 2017. The general policy plans of the ESP 2018–2030 were to enable Ghana to achieve the Targets of the SDG 4.

The Education Strategic Plan 2018-2030 puts Ghana on the road towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals and represents a deliberate reorientation towards this aim, as it replaces the previous ESP 2010-2020. This plan sets the long-term vision and how this will be operationalised in the medium term through the accompanying Education Sector Medium Term Development Plan 2018-2021. (Ministry of Education Citation2018b, p. ii).

The key findings of the articles were extracted corpus of data from the Education Strategic Plan 2018–2030 according to the practical argumentation approach (Fairclough and Fairclough Citation2018). below presents extracts concerning young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET from the ESP 2018–2030 according to five practical argumentation premises.

Table 1. Practical argumentation of ESP 2010–2020 concerning and intersection of gender, STEM, and TVET.

Problematising the identified problem-solution approach

I now engage the corpus of extracts from the ESP 2018–2030 concerning females’ participation in STEM-related TVET presented in the practical argumentation analysis from the CCA-VET perspective. The paper extensively critiques the circumstantial premise compared to the other premises. The primary assumption for the deepened concentration on the circumstantial premise is that the discourse used in the circumstantial premise was narrow, simplistic, and could not conceptualise the nuances of the identified problem. Therefore, all the subsequent premises appeared to be limited in focus and largely failed to address the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET.

Circumstantial problem: a deficit discourse

The current circumstantial premises revealed a socially constructed discourse where the low participation of young women in STEM-related TVET has translated into the description of STEM-related TVET courses as male-dominated fields. Drawing on the CCA-VET perspective, the primary critique of the current constructed discourse is that the conceptualisation of STEM-related TVET as ’male-dominated courses’ is deficit discourse (Aikman and Robinson-Pant Citation2016). A deficit discourse derived from the assumption that young women must participate in STEM-related TVET to achieve gender parity, which has become a global educational priority that stems from constructing the participation of young women in education from human rights-based and human capital perspectives. The human rights-based and human capital perspectives underpin the reasons for demanding an improvement in the participation of young women in STEM-related TVET in the ESP 2018–2030. These dominant perspectives drive the conceptualisation of STEM-related TVET courses as male-dominated courses because there is a general conscious or unconscious need to prove a gender imbalance in these relevant skills areas.

Nevertheless, to prove that males who dominate many spheres of education and the labour market hold a dominant place in STEM-related TVET and for that reason women and girls who have been marginalised in many spheres of life, especially in patriarchal societies such as Ghana, need to play catch-up with men in STEM-related TVET is problematic. Even when the emphasis is not on girls and women playing catch-up for gender parity, the emphasis turns to girls and women playing catch-up for national development and economic growth. The notion that girls and women need to catch up with men in STEM-related TVET for gender parity and economic growth is not only deficit discourse because it presents girls and women as citizens in need of rescuing, but because it also fails to conceptualise girls and women as citizens who value participation in STEM-related TVET for their flourishing regardless of whether or not males dominate those fields.

A broad range of actors, including researchers, practitioners, policymakers, educational stakeholders, and feminists calling for an improvement in the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET, use the phrase male-dominated or traditionally male-dominated. Most of these actors use the phrase to initiate a discourse about the problem without necessarily reflecting on the embedded negative meanings it could carry for young women. While there are unintended consequences for using the term ‘male-dominated fields’, most of these actors do not reflect on these indirect consequences because the phrase has become a normative description to emphasise the reality that girls and women are underrepresented in STEM and STEM-related TVET and to use it as a reference point to call for attention and seek solutions. For instance, Eccles (Citation2011), in her seminal paper gendered education and occupational choices, used the term male-dominated occupations to emphasise her point that there are specific STEM fields that males dominate and women may not want to be associated with these occupations because of the discrimination. A superficial reading of her paper may not engender questioning the use of the phrase male-dominated courses as problematic. However, it becomes debatable when there is a deepened reflection about the relevance of the phrase to the discourse and problem she studies. In reality that phrase might not be doing justice to solving the problem and moving the discourse beyond gender differences and gender parity.

Indeed, males form the majority of enrolments in STEM-related TVET courses, as the introduction has shown. However, it does not merit the position to describe and, in most cases, call STEM-related TVET male-dominated courses. It has become the case that calling these programmes male-dominated can directly or indirectly institutionalise young women’s decision not to choose STEM-related TVET courses and careers (Renold et al. Citation2019). The name ‘male-dominated course’ inherently confirms that these courses are fit for male learners but not female learners. The name further categorises other TVET programmes outside the scope of STEM as areas fit for female learners but not male learners. The misconception of STEM-related TVET as traditionally male-dominated courses has become an institution with structures, culture, and sanctions (Renold et al. Citation2019), perpetuating the existing gender inequalities in STEM-related TVET. For instance, girls and women do not have a sense of belonging in STEM-related TVET courses (Starr Citation2018). This is because these courses are, in most cases, structured without the measures to ensure female learners’ retention and flourishing after enrolling in STEM-related courses (Misola Citation2010; Buehren and Van Salisbury Citation2017). The name ‘male-dominated’ already alienates these STEM-related courses from the female population.

Another concern is that constructing STEM-related TVET as ’male-dominated fields’ limits the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET to only a gender inequalities/parity discourse. However, beyond the ‘politically-claimed objective of gender parity’, there are other essential reasons girl's and women’s participation in STEM-related TVET is relevant for their flourishing. For instance, there must be an enabling school environment to promote retention after increasing young women’s access to STEM-related TVET , which is the main indicator of gender parity. Also, there should be robust systems to ensure that young women are progressing beyond compulsory education and achieving their aspirations. If not, then the idea of parity becomes detrimental. What becomes the critical question then is, while the ESP 2018–2030 is pursuing gender equality in STEM-related TVET, what other critical freedoms are neglected? McGrath et al. (Citation2020) express this concern by stating that it is necessary to ‘move the VET debate away from equality in terms of parity of esteem of knowledge or qualifications and towards considerations of equality in terms of human freedoms and flourishing’ (p. 3).

Furthermore, describing STEM-related TVET as male-dominated courses is connected to the productivism approach to TVET, where work, particularly men’s work, is considered valuable for economic development and growth. For instance, Ball et al. (Citation2017) emphasise that the worldwide technological terrain is changing work rapidly, increasing the demand for a well-educated and skilled labour force, including women, to fit these increasing STEM roles. These fields are opportunities to participate in the fourth industrial revolution, primarily driven by STEM advancement. Dasgupta and Stout (Citation2014) add that a scientific revolution is crucial for economic competitiveness, national security, and quality of life and well-being. While a major policy concern is that girls’ and women’s untapped intellect in STEM-related TVET can hamper economic growth, it is equally essential to highlight that these untapped intellects can deny girls and women opportunities to flourish. For example, it is widely known that technological innovation affects the quality and components of jobs, therefore girls and women need to receive the kinds of education and training that can equip them with the knowledge and skills to participate this technological revolution valuably (Adams Citation2018).

It is important to emphasise that the deficit discourse in policy and research, appears to be one of the many contributing factors to the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET. The inadequacies in the TVET theoretical frameworks designed to address the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET policy and research discourses directly or indirectly undermine the inequities in policy provisions, interventions, and TVET practices. Also, the deficit policy discourse more or less reflects a wrong diagnosis of the problem and hence leads to limited solutions, where significant policies and interventions that can bring change are unnoticed or neglected. The next session explores the limitation of having a deficit discourse about the under-participation of young women in STEM-related TVET.

Goal premise and means-goal premise: limited focused

Consequently, with a problematic conceptualisation of the problem, the ESP 2018–2030 cannot articulate clear, targeted means-goal premises and goal premise underpinned by human development motives that can encourage young women opportunities in STEM-related TVET. Therefore, although the circumstantial premise identifies females’ low participation in STEM-related TVET such as engineering and construction, there is no explicit means-goal premise targeting the long-term flourishing of young women. It is noticeable that the goals premise talks about an aspiration to increase enrolment in STEM-related TVET courses and improve learning outcomes for all, especially girls. However, the goal premise does not articulate specific targets to facilitate targeted efforts and actions to ensure that young women in STEM-related TVET flourish in further STEM-related TVET education. For instance, the ESP 2018–2030 fails to expand on specific targets to ensure the safety of young women in technical institutes. Again, the ESP 2018–2030 fails to describe a goal that aims to ensure the equitable transition of female STEM-related TVET learners into higher education and the labour market. There are no employment or further education securities; therefore, the chances of young women ending up in precarious employment after upper secondary STEM-related TVET education can be high. Policymakers are not engendering a discourse that can translate into valuable opportunities for young women to actualise their capabilities through STEM-related TVET.

One more concern is that without specific human development targets beyond increasing enrolment numbers of young women in STEM-related TVET programmes, accountability for the successes of proposed strategies in the ESP 2018–2030 becomes a problem. Thus, it can be challenging to assess the progress in addressing the circumstantial premise beyond increasing the enrolment numbers of young women in STEM-related TVET. For instance, although the ESP 2018–2030 aims to increase learners’ outcomes, without the human developmental goal premise, other critical outcomes such as happiness, well-being, and the training culture for young women studying STEM-related TVET are highly likely to be neglected. Questions such as the following can remain unanswered: a) Are TVET institutions providing a nurturing environment for young women studying STEM-related TVET to competitive in the labour market? b) Do young women who study STEM-related TVET value these programmes? c) Do young women who complete STEM-related TVET end up in further education or the labour market? d) How do their careers progress regarding wage outcomes, seniority, and satisfaction?

If the ESP 2018–2030 has no answers to these questions, then two primary reasons explain the situation. The first reason is that education policymakers are not inviting the voices of TVET learners, especially young women’s voices, to the design of TVET policies. The absence of learners’ voices can detach policies from the reality of learners’ experiences and how policies impact their lives. Therefore, it is unfortunate that the voices of VET learners’ whom VET systems are designed to serve, are primarily absent in the consultative process of designing and redesigning TVET systems (Powell Citation2012). The second reason is that the human capital theory underpinned ESP and emphasised economic growth and productivity. The value for economic growth and productivity drives policies that do not develop means-goal premise and goal premise that are person-oriented, development-centred, and aspiration-oriented. Therefore, the valuable freedom of young women studying STEM-related TVET courses as Ghana’s citizens was not explicitly discussed as a goal ESP 2018–2030. Soliciting the voices of young women and expanding the purpose of TVET beyond human capital development can enable policymakers to frame TVET policies that focus on making STEM-related TVET attractive and valuable for young women.

Value premise: oversimplified

Concerning the value premise, although the ESP 2018–2030 has a value premise that draws on human development elements, first ‘to deliver quality education service at all levels that will equip learners in educational institutions with the skills, competencies, and awareness that would make them functional citizens who can contribute to the attainment of the national goal’. (p. 14). Second to provide ‘equal opportunity to obtain access to education and to learn and the provision of an environment that is conducive to learning and achievement of learning outcomes and that demonstrates fair and just assessment’ (p. 14). The value premises can remain unachievable without specific goal and means-goal premises with human development and capability values. It is essential to point out that pursuing gender equity and increasing access without specific human development means-goal premise that can ensure that young women are flourishing in the long term is a local problem and a global problem. For instance, the SDG 4, Target 3 states that ‘countries must ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational, tertiary education, including university by 2030’. (UN Citation2019, 14)

Furthermore, the value premise targeted removing barriers to skills development and TVET, starting from the secondary level, but that is inadequate. Like the ESP 2018–2030, the goal premises of the SDG 4 also fail to articulate a discourse to ensure the long-term flourishing of female learners. Therefore, it is not surprising to notice that, like Ghana, most countries making education policies to meet the SDG 4 targets cannot address girls’ and women’s under-participation in STEM-related TVET. For instance, besides Ghana, Tikly (Citation2020) reports young women’s under-participation in STEM-related TVET in Australia, Chile, South Africa, Netherlands, Germany, Jamaica, Philippines, and Lebanon.

Claim premise: unrealised goals

Finally, though there is a clear picture of what the government aims to achieve, such as improving learning outcomes in STEM subjects and overall learning outcomes for girls (p. 133), the government is yet to show concrete evidence on how it is achieving this claim. The evidence shows that young girls in upper secondary education in the developing world face unfavourable conditions that do not allow young women to achieve outlined learning outcomes. In most cases, they drop out of upper secondary education (UNESCO UIS Citation2019; UNESCO-UNEVOC Citation2019; Tikly Citation2020). It is easier to argue that if girls do not get access in the first place, all other efforts to support them cannot be applied. However, the complexity is that, without grasping the problem in its entirety, girls can gain access but may still not choose STEM-related TVET. Even when they choose STEM-related TVET courses, the right environment to flourish might not be available.

Eventually, the claim premise becomes redundant when the policy design is contrasted with its circumstantial premise. It is not surprising to find throughout the literature that national and global policy targeting young women’s participation in STEM-related TVET has failed or is yet to be achieved (Tikly et al. Citation2018; Tikly Citation2020). In particular, the issues of the lack of guidance and counselling that can complement efforts to young women to improve girls learning outcomes in STEM subjects is lacking or absent in most TVET institutions (Tikly Citation2020)

Conclusion

The analysis and discussions in this article show that the absence of a critical capability framed TVET polic’ies results in missed opportunities to fully understand and design more effective policies and interventions to address young women’s under-participation in upper secondary school STEM-related TVET. The primary critique of Ghana’s Education Strategic Plan 2018–2030 through the lens of CCA-VET has been that conceptualising STEM-related TVET as male-dominated courses is a deficit discourse.. The concern is that this deficit discours evolve from the two dominant approaches to TVET policy: human rights-based and human capital. Even when the ESP 2018–2030 proposed to drive some elements of human development, it does not articulate specific human development and capability goals that can ensure young women who decide to study STEM-related TVET flourish in the means-goal premises . The urgency for young women to participate in STEM-related TVET is a gender parity concern, a developmental concern, and a capability concern; therefore, taking one perspective to policy concerning the problem can be detrimental. It appears that when human development and capability inequalities are the core concerns of of policy, the human rights-based and human capital approaches appear to be deficient in offering policy solutions.

The rhetoric of the human capital approach and the right to education discourse both fail to question how young women can be encouraged to value and choose STEM-related TVET beyond the need for employment, economic outcomes, and productivity in industries. It is an essential message for the TVET community not only in Ghana but also for the international TVET community, which in the last few years has been combining human capital and rights-based approaches to TVET without a proper engagement with alternative policy frameworks such as the human development and capability approach (McGrath et al. Citation2020; Zancajo and Valiente Citation2019)

The analysis of Ghana’s ESP 2018–2030 has drawn our attention to the reality that TVET policies that take gender parity and human capital perspectives alone cannot achieve the desired transformational change. It is now a national and global call to begin the re-conceptualisation of TVET policy discourses and agendas that incorporate the CCA-VET approach, where the values of learners and human development needs are central to achieving the new transformational role of VET. The proposal for policymakers to frame VET policies with the CCA-VET approach to VET can allow a better understanding of the valued functioning of young women and ways to address this meaningful yet challenging social condition of the participation of young women in STEM-related TVET. The Ghanaian experience shows that alternative frameworks are still far from becoming an alternative to TVET policies. Breaking this hegemony of the human rights and human capital approaches requires awareness-creation and the re-conceptualisation of policy discourses, which cannot be achieved through silo mindsets and theories. The problem cannot be solved by one education approach, theoretical framework, or approach. The change needed is only attainable by integrating the critiques of human capital to enable education policy discourse to address inequalities in STEM-related TVET. CCA-VET remains one such valuable lens to design TVET policy for development.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to all known and unknown reviewers who made substantial contributions the paper through their comments and corrections. I wish to express my gratitude to the Government of Ghana and other key sponsors for funding my PhD and fieldwork. Final appreciation to my supervisor at the University of Cambridge who continue to provide overall guidance for my PhD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, Abi. 2018. “Technology and the Labour Market: The Assessment.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 34 (3): 349–361. doi:10.1093/oxrep/gry010.

- Aikman, S., and A. Robinson-Pant. 2016. “Challenging Deficit Discourses in International Education and Development.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 46: 314–334.

- Aikman, Sheila, and Anna Robinson-Pant. 2016. “Challenging Deficit Discourses in International Education and Development.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 46 (2): 314–334. doi:10.1080/03057925.2016.1134954.

- Alkire, Sabina, and Séverine Deneulin. 2009. “The Human Development and Capability Approach.” In Severine Deneulin & Lila Shahani (Eds.), An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach: Freedom and Agency, 22–30.

- Allais, Stephanie. 2012. “Will Skills Save Us? Rethinking the Relationships Between Vocational Education, Skills Development Policies, and Social Policy in South Africa.” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (5): 632–642. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.01.001.

- Amegah, Alice. 2021. “‘Business Without Social Responsibility is Business Without Morality’: Employer Engagement in Upper Secondary Technical and Vocational Education and Training Schools in Ghana.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 1–25. doi:10.1080/13636820.2021.1879904.

- Anderson, Damon. 2008. “Productivism, Vocational and Professional Education, and the Ecological Question.” Vocation and Learning 1: 105–129. doi:10.1007/s12186-008-9007-0.

- Arthur-Mensah, N., and M. Alagaraja. 2013. “Exploring Technical Vocational Education and Training Systems in Emerging Markets: A Case Study on Ghana.” European Journal of Training and Development 37 (9): 835–850.

- Arthur-Mensah, Nana, and Meera Alagaraja. 2018. “Human Resource Development International Examining Training and Skills Development of Youth and Young Adults in the Ghanaian Context: An HRD Perspective.” doi:10.1080/13678868.2018.1468587.

- Atsu, Anthony Mawutor, and Rebecca Lartekai Lartey. 2018. “Enhancing Participation of Girls in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET): The Case of Tamale Technical University.” International Journal of Education Research 2 (1): 1–8. 208-2204.

- Ayonmike, C. Shirley. 2014. “Factors Affecting Female Participation in Technical Education Programme: A Study of Delta State University, Abraka.” Journal of Education and Human Development 3 (3): 227–240. doi:10.15640/jehd.v3n3a18.

- Ball, Stephen J. 1990. Politics and Policy Making in Education. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ball, Christopher, Kuo-Ting Huang, Shelia R Cotten, and R V Rikard. 2017. “Pressurizing the STEM Pipeline: An Expectancy-Value Theory Analysis of Youths’ STEM Attitudes.” Journal of Science Education Technology 26: 372–382. doi:10.1007/s10956-017-9685-1.

- Bannikova, Lyudmila N., Aleksandr A. Baliasov, and Elena V. Kemmet. 2018. “Attraction and Retention of Women in Engineering.” Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference “‘Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies’”, (IT and QM), 824–827. IEEE. 10.1109/ITMQIS.2018.8525043.

- Bannikova, L N, and E V Kemmet. 2019. “A Woman in the Man’s Culture of Engineering Education.” Vysshee Obrazovanie V Rossii = Higher Education in Russia 28 (12): 66–76. doi:10.31992/0869-3617-2019-28-12-66-76.

- Bonvin, Jean-Michel. 2019. “Vocational Education and Training Beyond Human Capital: A Capability Approach.” In Handbook of Vocational Education and Training, 1–17. Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49789-1_5-1.

- Buehren, Niklas, and Taylor Van Salisbury. 2017. “Female Entrollment in Male-Dominated Vocational Training Course: Preferences and Prospects.” Washington Dc. https://www.lkdfacility.org/wp-content/uploads/Female-Enrollment-in-Male-Dominated-Vocational-Training-Courses-Preferences-and-Prospects.pdf.

- CAMFED Ghana. 2012. “What Works in Girls’ Education in Ghana: A Critical Review of the Ghanaian and International Literature.” Accra. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/What-Works-in-Girls-’-Education-in-Ghana/8cd27806c42870f538678764df0da3a11137c45e?p2df.

- COTVET. 2020. “MyTvet Campaign: Machanical Engineer.” https://www.facebook.com/1928841527339742/videos/233984111232298.

- Dadzie, Christabel E, Mawuko Fumey, and Suleiman Namara. 2020. “Youth Employment Programs in Ghana Options for Effective Policy Making and Implementation.” Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34349/9781464815799.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

- Darvas, Peter, and Robert Palmer. 2014. Demand and Supply of Skills in Ghana: How Can Training Programs Improve Employment and Productivity? Washington DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0280-5.

- Dasgupta, Nilanjana, and Jane G. Stout. 2014. “Girls and Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics: Steming the Tide and Broadening Participation in STEM Careers.” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1177/2372732214549471.

- DeJaeghere, Joan. 2016. “Girls’ Educational Aspirations and Agency: Imagining Alternative Futures Through Schooling in a Low-Resourced Tanzanian Community.” Critical Studies in Education 59 (2): 237–255. doi:10.1080/17508487.2016.1188835.

- DFID. 2005. ”Girls’ Education: Towards a Better Future for All.” In Gender and Education. Vol. 1. London. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.92149-4.

- Eccles, Jacquelynne S. 2011. “Understanding Women’s Achievement Choices: Looking Back and Looking Forward.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 35 (3): 510–516. doi:10.1177/0361684311414829.

- Ekuful, C. 2019. Government to Construct 32 TVET Institutions. Ghanaian Times. https://www.ghanaiantimes.com.gh/govt-to-construct-32-tvet-institutions/.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2012. “Critical_discourse_analysis_and_critical.”

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. “Critical Discourse Analysis and Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 7 (2): 177–197. doi:10.1080/19460171.2013.798239.

- Fairclough, Norman, and Isabela Fairclough. 2018. “A Procedural Approach to Ethical Critique in Cda.” Critical Discourse Studies 15 (2): 169–185. doi:10.1080/17405904.2018.1427121.

- Ghana Business News . 2019. ”Ghana Government Invests €500m in TVET - Deputy Minister.” General News .

- Graham, Phil. 2018. “Ethics in Critical Discourse Analysis.” Critical Discourse Studies 15 (2): 186–203. doi:10.1080/17405904.2017.1421243.

- Hoffmann-Barthes, Anna Maria, Shamila Nair, and Diana Malpede. 1999. “Scientific, Technical and Vocational Education of Girls in Africa.” Paris.

- Ingram, Helen, and Anne L. Schneider. 1997. “Policy Analysis for Democracy.” The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy, No. October 2017. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199548453.003.0008.

- Ingram, Helen, and S. Rathgeb Smith. 1997. ”Public Policy for Democracy.” In Public Policy for Democracy, edited by S. Rathgeb Smith and Helen Ingram, 1–14. Washington, D.C: The Brookings Institution. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=cqsebYveaA4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=policy+design+for+democracy&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiZzu6R57zsAhVOXRUIHT29C-cQ6AEwAXoECAkQAg#v=snippet&q=redistributive&f=false

- Makgato, Moses. 2019. “Stem for Sustainable Skills for the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Snapshot at Some Tvet Colleges in South Africa.” doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.89294.

- Mcdool, Emily, and Damon Morris. 2020. “Gender and Socio-Economic Differences in STEM Uptake and Attainment.” 29. Centre for Vocational Educational Research London. CVER Discussion Paper Series. London.

- McGrath, Simon. 2012. “Vocational Education and Training for Development: A Policy in Need of a Theory?” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (5): 623–631. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.12.001.

- McGrath, Simon, Lesley Powell, Joyceline Alla-Mensah, Randa Hilal, and Rebecca Suart. 2020 June. ”New VET Theories for New Times: The Critical Capabilities Approach to Vocational Education and Training and Its Potential for Theorising a Transformed and Transformational VET.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 1–22. doi:10.1080/13636820.2020.1786440.

- McGrath, Simon, Presha Ramsarup, Jacques Zeelen, Volker Wedekind, Stephanie Allais, Heila Lotz-Sisitka, David Monk, George Openjuru, and Jo Anna Russon. 2019. “Vocational Education and Training for African Development: A Literature Review.” Journal of Vocational Education and Training 1–23. doi:10.1080/13636820.2019.1679969.

- Ministry of Education. 2017. “Report on Basic Statistics and Planning Parameters for Technical and Vocational Education in Ghana.” Accra.

- Ministry of Education. 2018a. “Education Strategic Plan 2018-2030.” Accra. https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/education-strategic-plan-2018-2030-ghana.

- Ministry of Education. 2018b. “Sector Performance Report.” Accra: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Gender Children and Protection Social. (2018, June). Ghana Women Internship and Mentoring Programme. News. http://www.mogcsp.gov.gh/index.php/ghana-women-internship-mentoring-programme/

- Misola, Nehema K. 2010. “Improving the Participation of Female Students in TVET Programmes Formerly Dominated by Males the Experience of Selected Colleges and Technical Schools in the Philippines 3 Case Studies of T VET in Selected Countries.” www.unesco.org/unevoc.

- Mongolkhatan, Ts, and S Enkhtuvshin. 2015. “Gender Survey Among TVET Teachers and Students in the Western Region of Mongolia.” https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/countries/countries-content/mongolia/en/VET_Gender_Survey_TVET_2015_Mongolia.pdf.

- Morgan, Gloria. 2013. “Women in TVET : Input into Ghana’s COTVET Gender Strategy Dialogue.” Accra.

- Mullet, Dianna R. 2018. “A General Critical Discourse Analysis Framework for Educational Research.” Journal of Advanced Academics 29 (2): 116–142. doi:10.1177/1932202X18758260.

- Mutarubukwa, A. Pelagia, and Mzomwe Y Mazana. 2017. “Stigmatization Among Female Students in Natural Science Related Courses: A Case of Technical and Vocational Education Training Institutions in Tanzania.” Journal, Business Education September I (Iv): 1–12.

- Ngcwangu, Siphelo. 2019. “Skills Development and TVET Policies in South Africa: The Human Capabilities Approach.” In Handbook of Vocational Education and Training, 1–14. Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49789-1_4-1.

- Ngugi, Margaret. 2017. “Female Participation in Technical, Vocational Education and Training Institutions (TVET) Subsector : The Kenyan Experience.” Public Policy and Administration Research ISSN 7 (4): 9–23.

- Nussbaum, Martha. 2000. ”Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach.” In Women and Human Development the Capabilities Approach. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511841286.003.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2016. ”Introduction: Aspiration and the Capabilities List.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 17 (3): 301–308. Routledge. doi:10.1080/19452829.2016.1200789.

- Pantea, Maria Carmen. 2019. “Perceived Reasons for Pursuing Vocational Education and Training Among Young People in Romania.” Journal of Vocational Education and Training. doi:10.1080/13636820.2019.1599992.

- Powell, Lesley. 2012. “Reimagining the Purpose of VET – Expanding the Capability to Aspire in South African Further Education and Training Students.” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (5): 643–653. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.01.008.

- Powell, Lesley, and Simon McGrath. 2014. “Exploring the Value of the Capability Approach for Vocational Education and Training Evaluation: Reflections from South Africa.” International Development Policy | Revue Internationale de Politique de Développement 5: 1–20. doi:10.4000/poldev.1784.

- Renold, Ursula, Ladina Rageth, Katherine M. Caves, and Jutta Buergi. 2019. “Theoretical and Methodological Framework for Measuring the Robustness of Social Institutions in Education and Training.” 461. KOF Working Papers. Zürich, Switzerland: KOF Working Papers. doi:10.3929/ethz-a-010782581.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2016. “Capabilitarianism.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 17 (3): 397–414. doi:10.1080/19452829.2016.1145631.

- Schneider, Anne, and Mara Sidney. 2009. “What is Next for Policy Design and Social Construction Theory?” Policy Studies Journal 37 (1): 103–119. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00298.x.

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press. https://books.google.com.gh/books/about/Development_as_Freedom.html?id=NQs75PEa618C&redir_esc=y.

- Sen, Amartya. 2005. “Human Rights and Capabilities.” Journal of Human Development 6 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1080/14649880500120491.

- Sen, Amartya. 2009. The Idea of Justice. London, England: Penguin Books.

- Starr, Christine R. 2018. “‘I’m Not a Science Nerd!’: STEM Stereotypes, Identity, and Motivation Among Undergraduate Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 42 (4): 489–503. doi:10.1177/0361684318793848.

- Stoet, Gijsbert, and David C. Geary. 2018. “The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education.” Psychological Science 29 (4): 581–593. doi:10.1177/0956797617741719.

- Tembon, Mercy, and Lucia Fort. 2008. “Girls’ Education in the 21st Century Gender Equality, Empowerment, and Economic Growth.” Washington DC. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/EDUCATION/Resources/278200-1099079877269/547664-1099080014368/DID_Girls_edu.pdf.

- Tikly, Leon. 2013a. “Reconceptualizing TVET and Development: A Human Capability and Social Justice Approach.” Bonn. https://unevoc.unesco.org/fileadmin/up/2013_epub_revisiting_global_trends_in_tvet_chapter1.pdf.

- Tikly, Leon. 2013b. “Reconceptualizing TVET and Development: A Human Capability and Social Justice Approach.” In Revisiting Global Trends in TVET: Reflections on Theory and Practice, edited by Katerina Ananiadou, 1–39. Bonn, Germany: UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training.

- Tikly, Leon. 2020. “Boosting Gender Equality in Science and Technology a Challenge for TVET Programmes and Careers.”

- Tikly, Leon, Marie Joubert, Angeline M Barrett, Dave Bainton, Leanne Cameron, and Helen Doyle. 2018. “Supporting Secondary School STEM Education for Sustainable Development in Africa.” Bristol. bristol.ac.uk/education/research/publications.

- UN. 2019. “Review of SDG Implementation and Interrelations Among Goals Discussion on SDG 4-Quality Education.” https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/hlpf/2019.

- UNESCO. 2015. “Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All.” UNESCO Publishing. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002456/245656E.pdf.

- UNESCO. 2016. “Strategy for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) 2016-2021.” Paris, France. www.unesco.org/education.

- UNESCO UIS. 2019. “New Methodology Shows That 258 Million Children, Adolescents and Youth are Out of School Out-Of-School Children, Adolescents, and Youth: Global Status and Trends No Progress in Reducing Out-Of-School Numbers.” http://uis.unesco.org.

- UNESCO-UIS. 2006. “Participation in Formal Technical and Vocational Education and Training Programmes Wolrdwide: An Initial Statistical Study.” Bonn.

- UNESCO-UIS. 2018. “Participation in Education.” http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/gh.

- UNESCO-UNEVOC. 2019. “Promoting Gender Equality in STEM-Related TVET.” Promoting Learning for the World of Work. https://unevoc.unesco.org/go.php?q=Gender_STEM_Workshop.

- UNESCO-UNEVOC. 2020. “Virtual Conference on Understanding the Causes of Gender Disparities in STEM-Related TVET.”

- UNSECO. 2017. “Measuring Gender Equality in Science and Engineering: The SAGA Toolkit.” http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0025/002597/259766e.pdf.

- Valenti, S S, A M Masnick, B D Cox, and C J Osman. 2016. “Adolescents’ and Emerging Adults’ Implicit Attitudes About STEM Careers: ‘Science is Not Creative.’.” Science Education International 40.

- Watson, K., and F. Jeffrey. 2007. “Diversifying the U.S. Engineering Workforce: A New Model.” Journal of Engineering Education 96: 19–32.

- Winch, Christopher. 2013. ”The Attractiveness of TVET.” In Revisiting Global Trends in TVET: Reflections on Theory and Practice, edited by Katerina Ananiadou, 85–122. Bonn: UNESCO-UNEVOC. www.unevoc.unesco.org

- Wingate, James C. 2017. “Cracking the Code: Girls’ and Women’s Education in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM).” In Education 2030. Paris, France: UNESCO. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1080/03064229508535979.

- Wojcichowsky, Angela. 2016. “Needs Assessment of the TVET System in Ghana as It Relates to the Skill Gaps That Exist in the Extractive Sector.” Saskatoon. https://saskpolytech.ca/about/organization/documents/needs-assessment-ghana-tvet-system.pdf.

- Zancajo, Adrian, and Oscar Valiente. 2019. “Tvet Policy Reforms in Chile 2006–2018: Between Human Capital and the Right to Education.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 71 (4): 579–599. doi:10.1080/13636820.2018.1548500.