ABSTRACT

The protection and promotion of human rights is experiencing increased commitment around the globe. Many organisations, groups and movements have strategically employed ‘rights-based’ agendas in order to advance issues and accomplish particular objectives. However, despite this ongoing mainstreaming and dominance, there is little time to reflect on the efficacy, sustainability and shortcomings of taking rights-based approaches. In this introduction to the volume ‘Beyond ‘rights-based approaches’?’ we think critically about – and beyond – ‘rights-based’ approaches. As part of our review of the existing literatures (which we organise around three key waves in rights-based focused research), we introduce new research that seeks transformative solutions to systemic patterns of injustice, while considering the real changes in peoples’ lives. Central to our discussion is the proposal and then the deployment of a new framework, based on a ‘process/outcome axis’. From this vantage point we identify and discuss how our contributors challenge the prevailing assumptions and practices in the fight for human dignity, by addressing the gap between theory and practice, and between scholars, activists and practitioners.

Introduction

We have lived with a tension. This tension began to emerge around 2008 and has grown steadily since. It concerns a disjuncture between what our research participants have been communicating (which confirmed some of our own experiences of practice), and what we were observing in the existing literatures. This disjuncture stemmed from the dominance of ‘rights-based approaches’ to development. These influential approaches were habitually received and promoted as the way to incorporate a human rights practice within the development sector. Despite the fact that they were fraught with definitional issues, their dominance prevailed (both across the existing literatures and within various fields of practice). However, as Miller has previously acknowledged, this led some of her research participants to make claims to the effect of,

I hate the rights-based approach; I don’t need a Bible to tell me what to do … [Other NGOs] use it as a doctrine. It’s like if you break those rules you are wrong … You can’t use human rights as a sort of fixed thing that tells you what’s right and what’s wrong. It’s more complex than that.Footnote1

Or, others would similarly gest, ‘remember … [laughing] … whatever you do, don’t paint how we use human rights as similar to those rights-based groups’.Footnote2 Quickly Miller’s findings established that many grassroot activists and development practitioners were practicing rights outside and beyond formal rights-based approaches.

As time progressed, we began to further understand that what our research partners and participants were sharing with us was not necessarily unique or unusual, but rather something that was bourgeoning in everyday practice. Consequently, as the hegemony of all things ‘rights-based’ grew to wider sectors our tension grew too.

We started to discuss this disconnect with colleagues, peers and practitioners, and from there we identified the need to bring together others that were also feeling something similar. Late 2015 we called for interests in research that looked progressively beyond ‘rights-based approaches’. Our ambition, in calling for research findings in this area, was to provide a space where we might take stock of some key practices that have developed in new directions. These directions were important because they were not so closely observed in the existing literatures. That is, whilst there is an important cross-section of literatures that provides a wealth of insight into the various interpretations and practices of rights-based approaches (as we indeed go on to identify below), there are many other expressions that clearly and explicitly fall outside the broad umbrella concept of rights-based approaches. In particular, we wanted to find research that challenged the status quo of mainstream right-based discourses, and that identified new opportunities, models and initiatives of transformative practice.

We were hugely encouraged by the uptake, and in spring 2016 we hosted a one-day workshop at Kingston University, London, where we began to further question what it would mean to think more critically about and beyond ‘rights-based approaches’. Leading practitioners and scholars presented a fascinating collection of studies and wider discussions were plentiful. This volume is a culmination of that endeavour.

In this introduction to the volume ‘Beyond “Rights-Based Approaches”?’ we first outline the growth of rights-based approaches alongside their dominance in the existing literatures. We do this through our observation of three critical phases in rights-based focused research. We then introduce the various UN agencies’ understandings of human rights-based approaches. The latter is introduced for the purpose of identifying the significance of ‘process’ and ‘outcomes’ in human rights approaches and methodologies. We then use this identification to propose a new lens (based on a ‘process/outcomes axis’) through which ‘rights-based approaches’ and approaches ‘beyond’ can be analysed. Finally, we employ our lens as a means by which to identify some of the key contributions of the volume, and in so doing we introduce the articles by turn.

Situating ‘rights-based approaches’: three phases in research

‘Rights-based approaches’ first emerged within the development sector, before transcending to wider areas. It was (and still is) the dominant way in which a human rights discourse and practice has been received by development actors and scholars. At its most primal level, it involved a shift in focus from meeting vital ‘needs’ to claiming and protecting ‘rights’.Footnote3 Approaches were to be ‘participatory’, built on the active involvement and ‘advocacy’ of ‘poor’ and ‘excluded’ peoples.Footnote4 Analysis and programming were to be grounded on rights standards and principles (thereby prioritising properties such as universality, non-discrimination and equality) whilst also recognising the critical role of states as ‘duty-bearers’.Footnote5

To date there is still little consensus over exactly when the precise concept of ‘rights-based approaches’ emerged, however, it is easy to trace various international development agencies’ explicit talk of an integration of rights within development practice in the post-Cold war period of the early 1990s (with momentum building around the 1995 Copenhagen Summit on Social Development).Footnote6 From the mid-1990s onwards, a whole host of development actors started to adopt and promote ‘rights-based approaches’, ranging from United Nations’ (UN) agencies, major donors, international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and local grassroots NGOs and social movements.Footnote7

Phase one (mid-1990s–early 2000s)

Given the diverse actors involved, the first phase of rights-based focused research (mid-1990s–early 2000s) unsurprisingly sought to document the approaches’ growth and popularity, whilst also focusing on the different ‘rights-based’ understandings, forms and expressions.Footnote8 As part of this a number of key studies and edited collections revealed diverse interpretations of rights-based theory and practice and put forward some important case study examples.Footnote9 However, as Miller has previously identified, this led to a concern as to whether actors were discussing (and implementing) ‘human rights-based approaches’ or ‘rights-based approaches’, or whether they were one and the same thing. This distinction proved problematic when some development actors were identified to be inconsistent in their usage of the terms, whilst others saw a distinction between the two. As Miller noted,

For some, emphasis of the ‘human’ suggests an eminence of the legal implications and normative quality of human rights as defined within international law, whilst ‘rights-based approaches’ can imply a certain distance from the international human rights system, with an increased association with citizen rights. For others, the label ‘rights-based approaches’ represents shorthand for [both] ‘human rights-based approaches’ [and rights-based approaches] … Footnote10

(We, like many, incorporate the latter option.) Accordingly, it became more than apparent that there was no one-size-fits-allFootnote11 way of doing ‘rights-based’ work, with numerous researchers and practitioners identifying their expansive nature. During this time ‘rights-based approaches’ appeared to represent a complex ‘mantle’, ‘slogan’ or ‘metaphor’ that could cover a variety of ‘organisations’, ‘programmes’, ‘commitments’, ‘set of values, trends and initiatives in development practice’.Footnote12 This issue led to Miller’sFootnote13 identification of the ‘broad umbrella concept’ of rights-based approaches. This relates to the idea that by invoking a label that pertains to multiple expressions, ‘rights-based approaches’ could (and at times, have) covered most (or, worst all) incorporations of human rights within the development sector. Uvin’sFootnote14 questioning of different levels of rights incorporation (through his ‘rhetorical incorporation’, ‘political conditionality’, ‘positive support’ and ‘rights-based approaches’ categories) therefore represented a significant deviation at this time, albeit with his firm support for a linear progression towards rights-based approaches. In a similar vein Piron and O’NeilFootnote15 also furthered this important line of analysis through their acknowledgement of different donor approaches. They too promoted a more fully integrated rights methodology (i.e. rights-based approaches) whilst identifying analogous categories to Uvin (‘human rights mainstreaming’; ‘human rights dialogue’; ‘human rights projects’ and ‘implicit human rights work’).

Phase two (mid-2000s–mid-2010s)

The second phase in rights-based focused research (mid-2000s–mid-2010s) concentrated on establishing in-depth analyses of rights-based practices. With over a decade of practice to analyse, key studies provided new and important insights. Off the back of renewed and ongoing commitments by various actors,Footnote16 many sought to establish what best practice might look like, and in so doing, questioned what the ‘added value’, ‘potentials’ and ‘successes’ were to this new wave of development practice.Footnote17 Further to this was the desire to understand the various ‘pitfalls’, ‘failures’ and even liabilities of rights-based approaches.Footnote18 Others sought to address more challenging aspects related to real organisational change. For instance, Vandenhole and GreadyFootnote19 provided an important study, investigating evidence of key ‘drivers’, ‘obstacles’ and ‘spoilers’ to organisational change. There were also studies and volumes that organised around a concern for understanding how human rights principles and norms were being reinforced within the development context.Footnote20 Some for instance sought to examine key ways in which human rights were being mainstreamed and institutionalised in ‘judicial, bureaucratic and organisational processes’.Footnote21

By this point the broad umbrella concept of rights-based approaches to development had manifested further, with influential studies starting to talk of a rights-based ‘sector’ and ‘cascade’.Footnote22 What’s more, the hegemony of rights-based approaches no longer appeared to be just limited to the traditional development sector. A whole host of studies started to document new and emerging rights-based approaches, which had expanded into key areas. For instance, they included rights-based approaches to: conservation,Footnote23 healthFootnote24 (including maternal health,Footnote25 public health,Footnote26 HIV/AIDs,Footnote27 and lesbian and bisexual women’s healthFootnote28), world heritage site management,Footnote29 fisheries,Footnote30 local water governance,Footnote31 disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration,Footnote32 food security,Footnote33 and social work.Footnote34 Such studies typically examined how rights-based approaches had been translated from theory into practice and with what degrees of success (with many maintaining a keen focus on limitations, tensions and ambiguities).

During the latter part of this second phase it became increasingly clear that the ‘rights-based’ label was being used and practiced in a whole host of different ways by numerous different actors, and thus the broad umbrella concept of rights-based approaches was continuing to expand even further in its reach.

Phase three (mid/late 2010s to the present day)

Our observation is that we are now entering into the early stages of a third wave of rights-based focused research (mid/late 2010s to the present day). To date this phase has seen a steady resurgence in research that seeks to establish how rights-based approaches are being implemented after more than two decades of practice. Key studies are starting to re-analyse the extent to which there have been actual systematic changes in practice by contrast to mere rhetorical incorporation, and what this may mean for those actually claiming their rights. For instance, Nelson and DorseyFootnote35 have very recently re-visited what they deem as the ‘nexus’ of human rights and development, seeking to establish the extent to which rights-based approaches have led to ‘transformative changes’ and overcome numerous constraints that previously impacted effective implementation. Whilst they observe the continued growth in rights-based approaches, they also reach the conclusion that approaches that fully embrace human rights principles have been both slow and difficult to advance (essentially due to a problematic range of political, organisational and conceptual issues).Footnote36

Like the second phase, there continues to be a growth in actors that are implementing ‘rights-based approaches’ in broader fields. Alongside the wider areas identified above, more recent research details right-based approaches to areas related to global health,Footnote37 federal food assistance,Footnote38 broader food and nutrition security,Footnote39 as well as wider childhood policy making.Footnote40 There is also plenty of evidence of more enhanced rights-based work, by both human rights and development actors, in sectors related to ‘women’s health, children’s health and education, housing and essential medicines’.Footnote41

The ongoing growth of rights-based approaches (in both practice and research) has led to a further critical strand within this third phase of research. This relates to a move by practitioners and scholars to establish, understand and critique the boundaries of the broad umbrella concept of rights-based approaches and to better understand emerging human rights approaches whose practices are intentionally distinct from (or beyond) rights-based ones. We locate the contributions of this volume here. As we noted within our opening to this article, we became aware of the need to bring together leading practitioners, activists and scholars who were already starting to take stock of these key issues. This direction was, and is, important, because it has not been so closely observed in the existing literatures in the earlier phases of rights-based research. Consequently, the articles presented in this volume (and introduced later below) represent an emerging critical lens through which established institutional conceptualisations and practices of human rights protection are contested. This new area of research exposes how the hegemony of rights-based approaches is problematic (both in the understanding of human rights and in the ability to deliver human rights protection) and also how approaches can, and do, exist beyond.

We now turn to introduce the various UN agencies’ involvement with rights-based approaches, which we do for the purpose of identifying the significance of ‘process’ and ‘outcomes’ in numerous human rights approaches. Before doing this, however, we note here that we now intentionally switch to the UN’s lexicon of ‘human rights-based approaches’. Whilst we remain steadfast to our earlier assertion (that ‘rights-based’ is typically used as a shorthand for ‘human rights-based’ and ‘right-based’ approaches), we choose to be consistent with how the various UN agencies choose to explicitly self-identify.

UN agencies and ‘human rights-based approaches’

There are a number of key international milestones which led directly to the formation and adoption of the UN agencies’ human rights-based approachesFootnote42 to development (which – akin to the rights-based approaches to development discussed above – also stand as the precursor to broader UN human rights-based approaches). An excellent overview of these milestones can be found within Andre Frankovits’Footnote43 analysis of the ‘human rights-based approach and the UN system’. As FrankovitsFootnote44 details, key milestones include: the 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights and the reaffirmation of the Vienna Declaration (unequivocally acknowledging the linkages between human rights and development); UNICEF’s 1996 announcement that the Convention on the Rights of the ChildFootnote45 would frame UNICEF’s work (and it’s later 1998–2004 executive directive concerning the implementation of the ‘human rights-based approach’); Kofi Annan’s 1997 UN reform (leading to the explicit integration of human rights across all principal UN organs); the UN Development Programme’s (UNDP) 1998 formal integration of human rights frameworks across all its work; the establishment of HURIST 1999–2002 (designed to support the UNDP’s policy for integrating human rights); Amartya Sen’s co-authorship of the 2000 Human Development Report (within which Malloch Brown explicitly stated the direction for UNDP and the wider UN system, centred around a ‘human rights-based approach to human development and poverty eradication’Footnote46); The Millennium Declaration 2000 (which included the commitment for governments to take action on issues of human rights and poverty eradication); the further UN reforms in 2002 (where the UN Secretary-General developed the call for further promotion and protection of human rights across the UN machinery); the UNESCO General Conference 2003 (leading to the further integration of human rights-based approaches across all UNESCO’s programmes), and; the UN Common Understanding on a Human Rights-Based Approach to Development Cooperation (approved by the UN Development Group, and concurrently established as the formal UN ‘understanding’ on rights-based approaches).Footnote47

When taken as a whole, Frankovits’ review helps to map how key branches within the UN sought to clarify the relationship between human rights, poverty and development. What his work highlights is that the incorporation of human rights-based approaches emerged from the backdrop of greater UN reform (emerging from the Secretary-General’s position on and strong promotion of rights) and from there we can see a somewhat linear progression amongst agencies (albeit not equally parallel across all UN agencies at the same time). The picture that emerges is one that demonstrates a marked difference between the early 1990s (where ideas of rights were being explored and reaffirmed within and across agencies) and the early 2000s (where fully fledged human rights-based approaches were being operationalised and developed across different UN agencies). However, further to this, and as others have later detailed, various challenges and constraints came to the fore from the mid-2000s onwards. These included: staffing issues (for e.g. resistance from staff – questioning the extent to which it was the latest ‘fad’; tensions with rights-based approach leadership); conceptual problems (for e.g. lack of clarity caused by different understandings, stemming from UN system coordination); political issues (for e.g. the identification of states as the primary site of accountability; government and non-government partners unfamiliar with such approaches; tension between civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights); issues related to practical application (for e.g. the issuing of realistic time frames; challenges with rights-based development in contexts of extreme poverty).Footnote48

Following the adoption of human rights-based approaches to development, further approaches were subsequently adopted by different UN agencies. For instance, 2006 saw the formal adoption of ‘rights-based approaches to disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration’ (DDR) by UN Peacekeeping. Based on the work of the Inter-Agency Working Group on DDR, the UN Secretary General launched the UN Integrated Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration Standards, which set out the remit for best practice in rights-based DDR programming.Footnote49 Likewise UN Mission adopted formal ‘rights-based approaches to community policing’, which included critical right-based training for police officers.Footnote50 The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN (FAO) is a further classic example where we see rights-based approaches coming to the fore in different fields across the UN. Specifically, the FAO moved from having ‘little experience’ of incorporating rights-based agendas, through to a clear shift in focus, where the FAO made clear its position to realise the right to adequate food in the context of national food security, via the development and promotion of Guidelines that serve as a ‘rights-based practical tool addressed to all states’.Footnote51

To date, there are, however, a few UN bodies that are still to conform to the wider UN position on human rights-based approaches. One key area relates to the UN’s drug control system. Principally, whilst there is good and clear evidence as to the negative human rights impact of international drug control policies, an expansion of the legal framework for drug control is still desperately needed (specifically in regard to the requirements to respect, protect and fulfil human rights obligations).Footnote52 The latter stand as a key blockage to any meaningful attempt to implement a human rights-based approach. The UN’s taskforce on Tobacco Control is also in a similar position.Footnote53

Why ‘process’ and ‘outcomes’?

Given the diverse uses and expressions of rights-based approaches over the last two and half decades, there are of course a number of ways in which the boundaries of RBAs might be considered. This for instance could include the level of human rights integration,Footnote54 the ways in which activities have been assessed based on human rights norms,Footnote55 or the extent to which there has been real organisational change due to the incorporation of human rights strategies.Footnote56 However, we argue that a key foundational unit for analysis emerges when we take the UN’s conceptual understanding of RBAs as a frame of reference and then use it to expand the offering. We use the UN’s conceptual understanding here, not because it speaks of the ultimate definition of RBAs, nor because the UN has the definitive voice on such matters, but rather because of the overwhelming size and influence that is instilled within and across the UN architecture and machinery.

We propose a distinction here based on two central components of rights-based approaches: namely, process, and outcomes. These components can be traced back to the UN’s earlier proclamations of what (human) rights-based approaches are,Footnote57 and then later, how they are to be outworked in practice.Footnote58 Consistent with our stated argument (together with the overall contributions of this volume); clearly our intention is not to suggest that these two aspects are the only way to receive rights-based approaches, but rather, to propose that they offer an important lens through which alternative human rights methods and approaches can be analysed. For the purpose of developing this line of inquiry, we first provide a brief overview of these two rights-based components, as disseminated by the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights and other key UN agencies – especially through the UN’s ‘Common Understanding on the Human Rights-Based Approach to development’.Footnote59

UN agencies and the significance of ‘outcomes’

Critical to UN agencies’ conceptual understandings of rights-based approaches is the notion of ‘outcomes’. Put plainly, any rights-based approach (whether to: development; disarmaments, demobilisation and reintegration; health; education; governance; food security; water and sanitation; HIV/AIDS; employment and labour relations; social and economic security) must firmly and intentionally seek the actual realisation of a human right (or set of rights) as central to its overall objective and purpose. All UN agencies’ rights-based work must therefore seek to ‘contribute directly’ to the realisation of human rights.Footnote60 Further to this – and as addressed in the Common Understanding – any activities that ‘incidentally contribute to the realization of human rights does not necessarily constitute’ as part of a rights-based approach.Footnote61 From this perspective we therefore note the assertion that explicit and purposeful intent is critical. In other words, the intentionality of an outcome to directly contribute to the realisation of human rights, stands as a central component of such rights-based approaches.

Formal outcomes also start from and are defined by legally codified human rights standards and principles. These stem from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent international human rights instruments.Footnote62 The latter for instance may include: the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights, and Economic Social and Cultural Rights; the International Convention on the Rights of the Child; the Declaration on the Rights to Development; the International Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. National standards are also used for the purpose of developing various rights-based approach outcomes. Such standards broadly classify who the ‘rights-holders’ are, which according to the property of universality would delineate all as rights-holders. However, such approaches pinpoint critical excluded and marginalised peoples and those that are at most risk of having their rights violated.

The legal standards are also used to identify the core minimum threshold of entitlements, and to also highlight the key areas that should be addressed by any rights-based approach.Footnote63 Consequently, outcomes are frequently framed through the idea that a full realisation of a right (or set of rights) will necessitate a behavioural change in the ‘duty-bearer’ Footnote64 to protect, respect and fulfil such rights. Likewise, outcomes also rest heavily on the idea that ‘rights-holders’ will be able to identify, exercise and demand their right (or set of rights). From this basis, rights-based approaches are hoped to bring about positive and sustained changes in the lives of people, precisely because their intended outcomes rest heavily on the full realisation of human rights as defined in international law.Footnote65

UN agencies and the significance of ‘process’

Legally codified human rights standards are also used to directly guide all formal processes of any UN agencies’ rights-based approach (again, whether to: development; disarmaments, demobilisation and reintegration; health; education; governance; food security; water and sanitation; HIV/AIDS; employment and labour relations; social and economic security and so on). Core programme and policy processes will typically include: assessment and analysis; planning and design (inclusive of goals at various levels); implementation and delivery; monitoring and evaluation.Footnote66 The essential human rights principles that direct these processes are based on international standards (again, as normatively defined by international law and identified above) and are directed by the following human rights properties: universality and inalienability; indivisibility; interdependence and interrelatedness; non-discrimination and equality; participation and inclusion; accountability and the rule of law. The UN’s Common Understanding offers a succinct explanation of these properties,

Universality and inalienability. Human rights are universal and inalienable. All people everywhere in the world are entitled to them. The human person in whom they inhere cannot voluntarily give them up. Nor can others take them away from him or her. As stated in article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’.

Indivisibility. Human rights are indivisible. Whether of a civil, cultural, economic, political or social nature, they are all inherent to the dignity of every human person. Consequently, they all have equal status as rights, and cannot be ranked, a priori, in a hierarchical order.

Interdependence and interrelatedness. The realisation of one right often depends, wholly or in part, upon the realisation of others. For instance, realisation of the right to health may depend, in certain circumstances, on realisation of the right to education or of the right to information.

Equality and non-discrimination. All individuals are equal as human beings and by virtue of the inherent dignity of each human person. All human beings are entitled to their human rights without discrimination of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, ethnicity, age, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, disability, property, birth or other status as explained by the human rights treaty bodies.

Participation and inclusion. Every person and all peoples are entitled to active, free and meaningful participation in, contribution to, and enjoyment of civil, economic, social, cultural and political development in which human rights and fundamental freedoms can be realised.

Accountability and rule of law. States and other duty-bearers are answerable for the observance of human rights. In this regard, they have to comply with the legal norms and standards enshrined in human rights instruments. Where they fail to do so, aggrieved rights-holders are entitled to institute proceedings for appropriate redress before a competent court or other adjudicator in accordance with the rules and procedures provided by law.Footnote67

When taken together, these legal rights’ properties provide the foundation on which all processes are to be operationalised.Footnote68 The reason behind this explicit grounding emerges from the conceptual understanding that such properties will strengthen and deepen situation analysis (with the express purpose of advancing the full realisation of human rights or set thereof).Footnote69 For instance, the initial assessment of a situation should be directly transformed through the principles of equality and non-discrimination (precisely because there is a clear understanding that all human beings are entitled to their human rights without discrimination of any kind on the grounds of race, colour, sex, ethnicity …).Footnote70 This would in turn transform conventional development approaches, that have typically benefitted ‘national and local elites’.Footnote71 What we see therefore is that these properties and rights principles directly influence the way in which work is done. It is thus important to underline the professed ‘people-centred’ nature of the UN agencies’ rights-based approaches. As can be seen, this is built on a conceptual foundation that aims to respect the agency of all individuals (and conceivably, their communities) – irrelevant of distinction. Processes aim to be participatory (centred around those whose rights are being violated), whilst also explicitly seeking to protect and promote fundamental human rights (inclusive of addressing inequality and redressing discriminatory practices). Added to this, human rights principles also direct the focus of the process in regard to the role of ‘duty-bearers’. From this perspective, a light is directly shone on the need to ensure transparency and accountability of key duty-bearers (which should theoretically empower right-holders as part of the wider process).Footnote72

A further implication of drawing on those normative rights’ properties rests on the identification that all processes must seek to address key human rights concerns through a holistic rights analysis. That is, the properties of indivisibility, interdependence and interrelatedness should directly dictate the scope of practice and how it is to be operationalised. As the ‘Common Understanding’ identifies, this for example could involve rights-based processes that addresses the realisation of the right to health alongside issues related to the right to education and so on. Again, we make reference here to policy and programming processes, which will include: assessment and analysis; planning and design; implementation and delivery, and; monitoring and evaluation.

The process/outcomes axis

We noted at the start of this article that our ambition in calling for research papers beyond rights-based approaches emerged as a result of what our research participants were sharing with us, and what we were directly observing in practice. We also began to realise that there could be a new frame of reference from which different analyses might develop. As we started to bring together leading practitioners and academics, it was obvious that there was a need to re-consider whether a broader lens could be applied. This lens needed to not just be applicable to the development sector, but to other areas too (which in the case of our contributors related to: peace and security, economic justice, terrorism, military intervention, crime and justice, migration, poverty, indigenous peoples and peasants’ movements, as well as development). It also needed to be applicable to different research locations across the world (which for our contributors included: Mexico, Australia, Cambodia, Israel, Palestine, Syria, the United Kingdom, as well as transnational movements operating across Europe, Latin America, Asia, North America, Central America and Africa). Further to this was the key related requirement, namely, how we might better understand practices that squarely operate as human rights ones, whilst remaining distinct from rights-based approaches.

With this in mind, we employ a foundational framework built on the UN’s rights-based distinction of process and outcomes. This framework is not only relevant to bilateral and multilateral agencies, but also to non-governmental organisations, civil society organisations and social movements. We consciously do this in a way that does not suggest (or, advise) a progression toward rights-based approaches,Footnote73 but rather helps to situate different human rights approaches outside of that frame of reference.

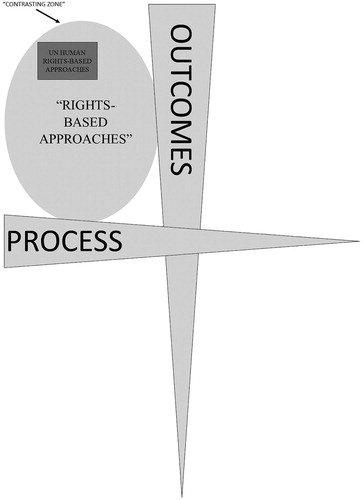

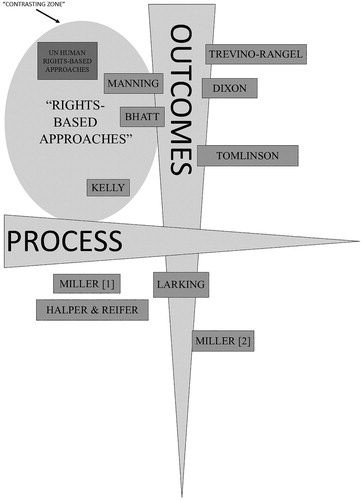

Our framework is built on a process/outcomes axis (as shown in ). The two perpendicular lines allow for an enhanced recognition of two critical spectrums of practice. The horizontal (x-)axis details the process spectrum, with a thick versus thin scale of human rights practice. ‘Processes’ typically include (but are not limited to) those identified in the UN agencies’ approaches (i.e. assessment and analysis; planning and design; implementation and delivery; monitoring and evaluation). The vertical (y-)axis details the outcomes spectrum, likewise with a thick versus thin scale of human rights practice. ‘Outcomes’ explicitly relate to the overall objectives, aims and purposes of an approach.

At the absolute ‘thickest’ region on the x-axis, legally codified human rights standards directly guide how formal processes are to be understood, organised and operationalised. Within the ‘thick to middle’ region, processes are more broadly aligned to international, regional and/or national human rights frameworks – however, they allow for a wider interpretation and selection. From this position (‘thick to middle’) the way in which work is carried out is still directly filtered through a human rights lens. By contrast, at the ‘middle to thin’ region, rights approaches are further distinguished by processes that incorporate a much broader idea of rights, and in a way that is far more selective and sparing. In practice, processes that operate at this level on the spectrum will likely utilise other lenses too (which, as our contributors evidence, could include social justice/liberalism/humanitarianism/radical ‘left’ politics/social transformation/social solidarity).Footnote74 At the absolute ‘thinnest’ region on the x-axis, processes are not aligned to any formal human rights norms or standards, neither are rights concepts a defining feature of how processes are to be understood and/or operationalised. They will, however, incorporate broader ideas of rights and ‘right talk’ at specific points in process cycles.Footnote75

At the absolute ‘thickest’ range on the y-axis, outcomes are based on and legally defined by normative principles and standards. Those operating within this region will see the full realisation of human rights (or set of rights) to be the raison d'être of their approach. Within the ‘thick to middle’ region outcomes are still based on the full realisation of human rights (or set of rights), however, these are more broadly interpreted and selected. At the ‘middle to thin’ range, formal outcomes are not aligned to codified human rights norms but may instead make reference to wider ideas and concepts of rights. The latter may be done selectively. In practice, approaches located within this region (‘middle to thin’) will typically prioritise outcomes that pull on different frames of reference (which, as our contributors evidence, could include social justice/ radical ‘left’ politics/ social solidarity).Footnote76 At the absolute ‘thinnest’ region on the y-axis, the overall outcome of an approach is not aligned to any formal realisation of human rights, however, it may make reference to broader rights concepts and ideas.Footnote77

The example of the UN agencies’ human rights-based approaches therefore epitomises a ‘thick’ practice of rights on both the x- and the y-axis. Accordingly, they are located within the top-left locale of the process/outcomes axis (see ). As we have identified, such approaches are conceptuallyFootnote78 built on overarching objectives that seek to contribute directly to the full realisation of human rights, whilst processes are intentionally filtered through international, regional and/or national human rights frameworks and broader properties of rights. This in turn impacts the critical classification of: who the ‘rights-holders’ are; what the core minimum thresholds of entitlements are; what key areas need to be addressed; what behavioural changes are required in the ‘duty-bearers’ (in relation to requirements to protect, respect and fulfil), and; how all work is to be understood, organised and operationalised.

not only identifies where the UN agencies’ approaches are to be located, but it also proposes where the wider boundary of ‘(human) rights-based approaches’ can rest. This wider boundary is based on the contributions of this volume and the trends within the existing literatures, as respectively discussed below and above. Consequently, the dominant message of an inherent broad umbrella concept of rights-based approaches becomes defunct, precisely because ‘rights-based approaches’ are to be located within one expansive region of the axis. With this in mind, the top-left locale of the axis houses both ‘rights-based’ and ‘human rights-based’ approaches, and thus functions as the contrasting zone for the axis. As we now demonstrate below, this zone stands as the reference point for identifying rights approaches beyond and outside rights-based approaches.

Introducing the articles by their place in the process/outcomes axis

The articles in this volume represent an emerging critical lens through which established institutional conceptualisations and practices of human rights protection are contested. This new area of research exposes rights-based approaches as problematic (both in their understanding of human rights and in their ability to deliver human rights protection). A reliance on a (‘thick’) legalistic solution to human rights problems often overlooks the social, cultural and political dynamics of the problems. Our contributors draw attention to deficiencies in rights-based approaches and offer instead examples, from across the globe, of new and innovative models of human rights work.

The articles in this volume are organised around their position on the process/outcomes axis (as illustrated in ), starting with those that offer examples of innovation (located within the lower region of the y-axis) and ending with those articles whose critique is oriented towards ‘thick’ human rights practice (located in the higher region of the y-axis). This rationale is designed to enable readers to first get a clear picture of the tensions between practice and research, and then to see problems associated with ‘rights-based’ practice.

We begin at the lower region of the process/outcomes axis, with Hannah Miller’s article, ‘Human Rights and Development: The Advancement of new Campaign Strategies.’Footnote79 Miller critically examines why some influential (and more radical) NGOs have been firmly rejecting rights-based approaches whilst simultaneously incorporating one of two new human rights models. Her analysis stems from an in-depth 10-year research project, which focused on activist experiences and understandings. Uniquely, the offering of two distinct models locates Miller’s contribution within two locales of the process/outcomes axis. First Miller details the development of ‘rights-framed approaches’ (located within the bottom-left), and then she sets out the proposal of ‘rights-referenced approaches’ (located within the bottom-right). Both approaches are identified to offer an innovative, strategic and instrumental embedding of a human rights discourse and practice. Miller’s research highlights key social, political and cultural contexts that have necessitated the emergence of these different models, and in so doing reveals some of the crucial limitations associated with rights-based approaches.

Jeff Halper and Tom Rifer focus on the contradiction between having rights and actualising them in their exploration of the work of a grassroots Israeli organisation in their article ‘Beyond ‘The Right To Have Rights’: Creating Spaces of Political Resistance Protected By Human Rights’.Footnote80 Their work is also located within the bottom-left of the process/outcomes axis. Identifying the political will of states to be the largest barrier to rights enforcement, they question whether a rights-based approach to conflict resolution is even possible? States’ failures to protect human rights in practice when a legal structure is in place for them to do so, renders human rights frameworks impotent. Halper and Rifer use Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD) to demonstrate how activism has abandoned rights-based approaches because a focus on (‘thick’) outcomes is fruitless in prolonged conflict zones. Activists are now locating new spaces within civil society in order to engage with the political dynamics of human rights, the needed piece of the puzzle in order to effectively provide human rights for all.

In her article ‘Mobilising for Food Sovereignty: The Pitfalls of International Human Rights Strategies and an Exploration of Alternatives’,Footnote81 Emma Larking investigates the international peasant’s movement Via Campesina. Larkin’s research is located within the middle region of both axis. She shows how activists have creatively engaged with rights-based approaches to issues surrounding the globalisation of agricultural markets and neoliberal interventions in food production. Her evidence challenges well established sociological conceptions of ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ accounts of rights development. The Via Campesina movement is presented as an innovative strategy that combines a desire for legal reform while also advocating for more radical social and political transformations. Her case study seeks to move beyond rights-based approaches into a field of practice that engages with political, social and cultural aspects of rights protection, as well as adoption and adherence to international legal mechanisms.

We then move near the centre top of the process/outcomes axis with Peter Manning’s contribution, entitled ‘Recognising Rights and Wrongs in Practice and Politics: Human Rights Organisations and Cambodia’s “Law Against the Non-Recognition of Khmer Rouge Crimes”’.Footnote82 In this article he uses the controversial case of the 2013 Cambodian atrocity denial law, embroiled within the debate between the curtailment of free speech and the potential harm of hate speech, to evaluate how human rights-based organisations think about and intervene in the political and social environments in which they work. He is critical of a tendency toward legalistic solutions as they are decontextualising and de-historicising. He identifies a preoccupation with the symptoms of human rights problems rather than their possible causes, which obscures the social and political components of the human rights work that is needed.

Chetan Bhatt’s article ‘Human Rights Activism and Salafi-Jihadi Violence’,Footnote83 an examination of contemporary western left-wing anti-imperialist politics, is also located near the centre top of the process/outcomes axis. Bhatt identifies a worrying link between politics and violence. He argues that a centrist consensus about human rights can no longer be assumed in several western and non-western democratic countries. This leads to his critique of human rights activism that has (thick) legal outcomes as their goal. He claims such a focus fails to recognise the erosion of the moral fabric of human rights, a loss he considers problematic in the practice and purpose of human rights. His case studies look at how knowledge and social action are related to human rights activism. He is critical of politics that reduces human rights to a legal framework because he claims this dilutes the potency of the concept of human rights and reduces its potentially radical power.

Keeping within the ‘thick’ range of the y-axis (but moving to the right), Paul Dixon’s article ‘Endless Wars of Altruism? Human Rights, Humanitarianism and the Syrian War’,Footnote84 conducts an analysis of the arguments Jo Cox MP and Hilary Benn MP used to justify increased British military involvement in Syria in 2015. He demonstrates how the ending of human rights abuses and providing humanitarian assistance are rationalised as arguments to escalate war. He is critical of how rights-based approaches present human rights as natural, absolute, universal and non-political, because this view has seeped into humanitarian work causing a shift from needs-based immediate relief to the advocacy of military intervention. He illustrates that in the UK, British Liberals Hawks have a track record of using human rights and humanitarianism to legitimise war on moral grounds.

Javier Trevino-Rangel’s article ‘Magical Legalism: Human Rights Practitioners and Undocumented Migrants in Mexico’Footnote85 also shows the pitfalls of (thick) legalistic ‘solutions’ to human rights problems in his investigation into how human rights practitioners and rights-based organisations in Mexico talk about the suffering and violence routinely experienced by transmigrants. His work is located within the top-right of the process/outcomes axis. He argues that the political and social conditions that make the abuses possible in the first place remain unchallenged when the goal is a change in the law or the inclusion of new legal provision. He acknowledges the important normative dimension to human rights but warns that no proper protection can be granted to transmigrants in Mexico, if the human rights practitioners and organisations are not willing to address the political circumstances in which they are operating.

Ruth Kelly’s research is firmly located in the top-left of the process/outcomes axis. Kelly writes from a practitioner’s perspective in her article ‘Translating Rights and Articulating Alternatives: Rights-Based Approaches in Action Aid’s work on Unpaid Care’.Footnote86 She evaluates how Action Aid’s adoption of a human right-based approach has transformed the non-governmental organisation’s structure, processes and priorities. She identifies the challenges of organisational alignment but posits this shift in focus as producing new and innovative ways of adapting and expanding what human rights-based approaches mean. She consequently offers new and important insights from within the ‘contrasting zone’ of the process/outcomes axis.

Finally, the last article – located at the top of the process/outcomes axis – is by Kathryn Tomlinson. Her piece ‘Indigenous Rights and Extractive Resources Projects: Negotiations over the Policy and Implementation of FPIC’Footnote87 critically examines how free, prior, informed consent (FPIC) has emerged as the focal rights-based approach to ensuring indigenous peoples are not negatively impacted, and benefit from extractive projects (e.g. oil, gas and mining). Also writing from the position of a practitioner with over 10 years’ experience working within the extractive industries, Tomlinson evaluates the efficacy of using FPIC in the process of safeguarding indigenous rights. She highlights the difficulties of applying a legal framework wherein there remains a lack of agreement on what the language means, especially what ‘consent’ means in practice. This highlights the disjuncture between the theory of human rights-based approaches advocated by NGOs and international organisations (as located in the ‘contrasting zone’ of the process/outcomes axis), and practical problems of delivering this approach (which therefore moves Tomlinson’s research to the top-right position of the axis). Tomlinson provides critical examples which include governments’ reluctance to confer ‘veto’ rights to indigenous peoples and mining companies’ lack of understanding of how to implement FPIC in practice.

This volume revels the tension between research and practice and the emergence of a new way of thinking that goes beyond the hegemony of rights-based approaches. It begins a dialogue between practitioners, activists and scholars on how to improve the effectiveness of human rights work by using a wider variety of human rights methodologies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Hannah Miller, ‘From “Rights-Based” to “Rights-Framed” Approaches: A Social Constructionist View of Human Rights Practice’, International Journal of Human Rights 14, no.6 (2010): 915.

2 Hannah Miller, ‘From Rights-based to Rights-framed Approaches: “Rights Talk”, Campaigns and Development NGOs’ (PhD thesis, Roehampton, Roehampton University, 2010).

3 Maxine Molyneux and Sian Lazar, ‘Doing the Rights Thing: Rights-based Development and Latin American NGOs’, Viewpoints (London: ITDG Publishing, 2003), 6.

4 Paul Nelson and Ellen Dorsey, ‘Who Practices Rights-Based Development? A Progress Report on Work at the Nexus of Human Rights and Development’, World Development 104 (2018): 99.

5 Brigette Hamm, ‘A Human Rights Approach to Development’, Human Rights Quarterly 23 (2001); Nelson and Dorsey, ‘Who practices rights-based development?’ 99.

6 Sam Hickey and Dian Mitlin, eds, Rights-Based Approaches to Development: Exploring the Potentials and Pitfalls (Sterling: Kumarian Press, 2009); Andrea Cornwall and Celestine Nyamu-Musembi, ‘Putting the “Rights-Based Approach” to Development into Perspective’, Third World Quarterly 25, no. 8 (2004): 9–18.

7 IGOs have included: UNDP, UNIFEM, UNICEF, UNHCHR. Major donors have included: the UK’s DFID and SIDA. INGOs include Oxfam International, Save the Children, ActionAid, and CARE International. See Paul Gready and Jonathan Ensor, ‘Introduction’, in Reinventing Development? Translating Rights-based Approaches from Theory into Practice, ed. Paul Gready and Jonathan Ensor (London: Zed Books, 2005), 1; Celestine Nyamu-Musembi and Andrea Cornwall, ‘What Is the “Rights-Based Approach” All About? Perspectives from International Development Agencies’. IDS Working Paper 234 (Brighton: IDS, 2004), 12–42; Andrea Cornwall and Celestine Nyamu-Musembi, ‘Why Rights, Why Now? Reflections on the Rise of Rights International Development Discourse in “Developing Rights”’, IDS Bulletin 36, no. 1 (2005).

8 See for instance, Gready and Ensor, ‘Introduction’, 1; Nyamu-Musembi and Cornwall, ‘What Is the “Rights-Based Approach” All About? 12–42.

9 See for instance, Nyamu-Musembi and Cornwall, ‘What Is the “Rights-Based Approach” All About?; Raymond Offenheiser and Susan Holocombe, ‘Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing a Rights-Based Approach to Development: An Oxfam America Perspective’, Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly 32 (2003): 268–306; Overseas Development Institute, "What can we Do with a Rights-based Approach to Development?", Briefing Paper 1 (1999); Paul Gready and Jonathan Ensor (Eds.) Reinventing Development? Translating Rights-Based Approaches From Theory into Practice, (London: Zed Books, 2005); Emma Harris-Curtis, Oscar Marleyn and Oliver Bakewell, The Implications for Northern NGOs of Adopting Rights-Based Approaches (Oxford: INTRAC, 2005), 558–64; Stephen Plipat, ‘Developmentalizing Human Rights: How Development NGOs Interpret and Implement a Human Rights-Based Approach to Development Policy’ (Thesis, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2005); Joachim Theis and Claire O’Kane, ‘Children’s Participation, Civil Rights and Power’, in Reinventing Development? Translating Rights-Based Approaches from Theory into Practice, ed. Paul Gready and Jonathan Ensor (London: Zed Books, 2005), 156–70.

10 Miller, ‘From “Rights-Based” to “Rights-Framed”’, 915–31.

11 Joachim Theis, Promoting Rights-Based Approaches: Experiences and Ideas from Asia and the Pacific (Stockholm: Save the Children Sweden, 2004), 19.

12 Harris-Curtis, Marleyn and Bakewell, The Implications for Norther NGOs, 39–40; Paul Nelson and Ellen Dorsey, New Rights Advocacy: Changing Strategies of Development and Human Rights NGOs (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2008), 93; Nyamu-Musembi and Cornwall, ‘What Is the “Rights-Based Approach” All About? 5.

13 Hannah Miller, ‘From “Rights-Based” to “Rights-Framed” Approaches: A Social Constructionist View of Human Rights Practice’, in Sociology and Human Rights: New Engagements, Pracillia Hynes, Michele Lamb, Damien Short, Matthew Waites (London: Taylor and Francis, 2012).

14 Peter Uvin, Human Rights and Development (Bloomfield: Kumarian Press, 2004).

15 Laure-Hélène Piron with Tammie O’Neil, Integrating Human Rights into Development. A synthesis of donor approaches and experiences (Brighton: Overseas Development Institute, 2005).

16 For example, Oxfam’s 2013-2019 Strategic Plan, which explicitly addressed its ongoing commitment to rights-based approaches (built around its five “rights-based aims” – to life and security; sustainable livelihoods; essential services; to be heard, and; an identify). See Oxfam International, The Power of People Against Poverty, Oxfam Strategic Plan 2013–2019 (Oxford: Oxfam, 2013), https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/story/oxfam-strategic-plan-2013-2019_0.pdf.

17 See for e.g. Hickey and Mitlin, Rights-Based Approaches to Development; Nelson and Dorsey, New Rights Advocacy; Shannon Kindornay, James Ron, and Charli Carpenter, ‘Rights-Based Approaches to Development: Implications for NGOs’, Human Rights Quarterly 34, no. 2 (2012): 472–506; Paul Gready, ‘Organisational Theories of Change in the Era of Organisational Cosmopolitanism: Lessons from ActionAid's Human Rights-Based Approach’, Third World Quarterly 34, no. 8 (2013): 1339–60.

18 Hickey and Mitlin, Rights-Based Approaches to Development; Nelson and Dorsey, New Rights Advocacy; Kindornay, Ron, and Carpenter, ‘Rights-Based approaches’, 472–506; Gready, ‘Organisational Theories’, 1339–60.

19 Wouter Vandenhole and Paul Gready, ‘Failures and Successes of Human Rights-based Approaches to Development: Towards a Change Perspective’, Nordic Journal of Human Rights 32, no.4 (2013).

20 See for instance the special issue of the Nordic Journal of Human Rights 32, no.4 (2013).

21 Maija Mustaniemi-Laakso and Hans-Otto Sano ‘Editorial note’, Nordic Journal of Human Rights 32, no.4 (2013).

22 Kindornay, Ron, and Carpenter, ‘Rights-Based approaches’, 472–506.

23 Jessica Campese, Terry Sunderland, Thomas Greiber, Gonzalo Oviedo eds. Rights-based approaches: exploring issues and opportunities for conservation (CIFOR and IUCN, 2009).

24 Sofia Gruskin, Dina Bogecho, Laura Ferguson, ‘Rights-Based Approaches to Health Policies and Programs: Articulations, Ambiguities and Assessment’, Journal of Public Health policy 31, no. 2 (2010): 129–45.

25 Alicia Yamin, ‘Towards Transformative Accountability: Applying a rights-based approach to fulfil maternal health obligations’, SUR – International Journal of Human Rights 12 (2010): 95–122.

26 Elvira Beracochea, Corey Weinstein, Dabney Evans eds., Rights-based approaches to public health (New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2011).

27 Alessanddra Sarelin, ‘Human Rights-based approaches to development cooperation, HIV/AID and food security’, Human Rights Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2007): 460–88.

28 Julie Fish and Susan Bewley, ‘Using human rights-based approaches to conceptualise lesbian and bisexual women’s health inequalities’, Health and Social Care in the Community 18, no. 4 (2010).

29 Stener Ekern, William Logan, Birgitte Sauge and Amund Sinding-Larsen, ‘Human Rights and World Heritage: Preserving Our Common Dignity Through Rights-Based Approaches to Site Management’, International Journal of Heritage Studies 18, no. 3 (2012): 213–25, doi:10.1080/13527258.2012.656253.

30 Edward Allison, Blake Ratner, Bjorn Asgard, Rolf Willmann, Robert Pomeroy, John Kurien, ‘Rights-Based Fisheries Governance: From Fishing Rights to Human Rights’, Fish and Fisheries 13, no. 1 (2011): 14–29.

31 Peter Laban, ‘Accountability and Rights in Right-based Approaches for Local Water Governance’, International Journal of Water Resources Development 23, no. 2 (2007): 355–67, doi:10.1080/07900620601183008.

32 Lars Waldorf, ‘Getting the Gunpowder Out of their Heads: The Limits of Rights-Based DDR’, Human Rights Quarterly 35, no. 3 (2013): 701–19.

33 Sarelin, ‘Human Rights-based Approaches’.

34 David Androff, Practicing Rights: Human Rights-based Approaches to Social Work Practice (Oxon: Routledge, 2015).

35 See Nelson and Dorsey, ‘Who Practices Rights-based Development?’, 97–107.

36 Ibid., 99.

37 Matheus de Carvalho Hernandez and Inga Winkler, ‘Human Rights in Global Health: Rights-based Governance for a Globalizing World by Benjamin Mason Meier and Lawrence O. Gostin’ (review), Human Rights Quarterly 40, no.4 (2019): 1045–8.

38 Molly Anderson, ‘Make Federal Food Assistance Rights-based’, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 1 no. 3 (2019).

39 Anna Jenderdijann and Anne Bellows, ‘Addressing Food and Nutrition Security from a Human Rights-based Perspective: A Mixed-methods Study of NGOs in Post-Soviet Armenia and Georgia’, Food Policy 84 (2019), doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.02.002.

40 Bronagh Byrne and Laura Lundy, ‘Children’s Rights-based Childhood Policy: A Six-P Framework’, The International Journal of Human Rights (2019), doi:10.1080/13642987.2018.1558977.

41 Nelson and Dorsey, ‘Who Practices Rights-based Development?’, 106.

42 From the offset UN agencies have spoken of “human rights-based approaches” or HRBAs (rather than, RBAs). This is important because it further exposes the particular weight that is placed on the UN agencies’ understanding and emphasis.

43 Andre Frankovits, The Human Rights Based Approach and the UN System, UNESCO Strategy on Human Rights (UNESCO, 2006). See https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000146999.

44 For further detail, see Frankovits, The Human Rights Based Approach, 13–22.

45 It also made clear that the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women underpinned UNICEF’s work. Ibid., 16.

46 Ibid., 19.

47 As discussed below.

48 Lauchlan Munro ‘The “Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming”: A Contradiction in Terms? in Hickey and Mitlin, Rights-Based Approaches to Development (Sterling: Kumarian Press, 2009); Dzodzi Tsikata ‘Annoucing a New Dawn Prematurely? Human Rights Feminists and the Rights-based Approaches to Development’, in Feminisms in Development: contradictions, contestations and challenges, ed. Andrea Cornwall, Elizabeth Harrison and Ann Whitehead (London: Zed Books, 2007); Frankovits, The Human Rights Based Approach.

49 United Nations Department of Peace Keeping Operations, The UN Approach to DDR in Integrated, Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Standards 2.10 at 8-15 (2006). For an excellent discussion on this more broadly, see Waldorf ‘Getting the Gunpowder Out’.

50 These approaches have been adopted in places like South Sudan, see United Nations Peace Keeping, UN Mission trains South Sudanese Police Officers on Rights-based Community Policing (2019), https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/un-mission-trains-south-sudanese-police-officers-rights-based-community-policing (last accessed March 2019).

51 FAO Council, Voluntary Guidelines: To Support the Progressive Realization of the Right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2005), http://www.fao.org/3/a-y7937e.pdf.

52 See Barrett, Damon and Manfred Nowak. ‘Chapter Twenty-Seven. The United Nations And Drug Policy: Towards A Human Rights-Based Approach’, in The Diversity of International Law, ed. Aristotle Onstantinides and Nikos Zaikos (Leiden, 2010).

53 See Carolynn Dresler, Harry Lando, Nick Schneider and Hitakshi, ‘Human Rights-based Approach to Tobacco Control’, Tobacco Control 21 (2012): 208–11.

54 Uvin, Human Rights and Development.

55 Piron with O’Neil, Integrating Human Rights.

56 Vandenhole and Gready, ‘Failures and Successes’.

57 See for instance, United Nations, The Human Rights-based Approach to Development Cooperation, Towards a Common Understanding Among the United Nations Agencies UN Common Understanding on Rights-based Approaches to Development (Stamford: Second Inter-agency Workshop, 2003), https://undg.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/6959-The_Human_Rights_Based_Approach_to_Development_Cooperation_Towards_a_Common_Understanding_among_UN.pdf.

58 See for instance, HRBA portal 2019. We also note that we are indebted to Vandenhole and Gready, who in their very brief but important discussion on ‘process’ and ‘outcome’, led to the development of our analysis as proposed here. See Vandenhole and Gready, ‘Failures and Successes’, 293

59 See for instance, United Nations, The human rights-based approach.

60 See Ibid.

61 OHCHR, Frequently Asked Questions on a Rights-based Approach to Development Cooperation (New York: United Nations, 2006), 35 https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FAQen.pdf.

62 OHCHR, Frequently Asked Questions.

63 For instance, ‘that priority attention should be given to the poorest of the poor and groups suffering discrimination. Even if not all can be reached at once, efforts should be made to identify these groups at the outset and include them immediately in planning.’ Ibid., 28.

64 ‘Duty-bearers’ typically refer to those working as agents of the State, however, they can also involve agents of transnational corporations and other influential actors. The latter is obviously more problematic.

65 See for instance the example of the right to food campaign.

66 United Nations, The Human Rights-based Approach.

67 Ibid., 2 (italics in original).

68 OHCHR, Frequently Asked Questions, 23.

69 Ibid., 23.

70 Ibid., 24.

71 Ibid., 24.

72 Ibid.

73 By contrast to Uvin, Human Rights and Development; Piron with O’Neil, Integrating Human Rights; WB/OECD-Compendium, Integrating Human Rights into Development. Donor approaches, 2nd edition (Washington, DC: The World Bank and the OECD, 2013).

74 See, Hannah Miller, ‘Human Rights and Development: The Advancement of New Campaign Strategies’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue; Emma Larking, ‘Mobilising for Food Sovereignty: The Pitfalls of International Human Rights Strategies and an Exploration of Alternatives’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue; Paul Dixon, ‘Endless Wars of Altruism? Human Rights, Humanitarianism and the Syrian War’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue; Javier Trevino-Rangel, ‘Magical Legalism: Human Rights Practitioners and Undocumented Migrants in Mexico’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue.

75 See Miller, ‘Human Rights and Development’ and Larking, ‘Mobilising for Food Sovereignty’.

76 See Miller, ‘Human Rights and Development’; Larking, ‘Mobilising for Food Sovereignty’; Dixon, ‘Endless Wars of Altruism? Jeff Halper and Tom Rifer, ‘Beyond ‘The Right To Have Rights’: Creating Spaces of Political Resistance Protected By Human Rights’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue

77 See Miller, ‘Human Rights and Development’ and Larking, ‘Mobilising for Food Sovereignty’.

78 Throughout this article we have pointed to the ‘conceptual’ understandings of different approaches (which we especially highlighted in our discussions of the various UN agencies’ understandings). This is deliberate. We note (as in deed many of our contributors do too), there can of course be a schism between conceptual understandings and actual practice, or between theory and practice. We situate the UN agencies’ approaches within the process/outcomes axis by their conceptual understandings alone.

79 Miller, ‘Human Rights and Development’.

80 Halper and Rifer, ‘Beyond “The Right To Have Rights”’.

81 Larking, ‘Mobilising for Food Sovereignty’.

82 Peter Manning, ‘Recognising Rights and Wrongs in Practice and Politics: Human Rights Organisations and Cambodia’s ‘Law Against the Non-Recognition of Khmer Rouge Crimes’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue.

83 Chetan Bhatt, ‘Human Rights Activism and Salafi-Jihadi Violence’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue.

84 Dixon, ‘Endless Wars of Altruism?’.

85 Trevino-Rangel, ‘Magical Legalism’.

86 Ruth Kelly, ‘Translating Rights and Articulating Alternatives: Rights-Based Approaches in Action Aid’s work on Unpaid Care’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue.

87 Kathryn Tomlinson, ‘Indigenous Rights and Extractive Resources Projects: Negotiations over the Policy and Implementation of FPIC’, International Journal of Human Rights (2019) this issue.