ABSTRACT

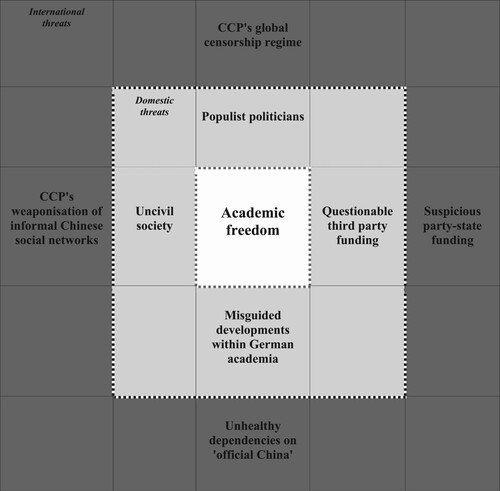

The authors probe whether or not the ecosystem of organised academia in Germany provides sufficient academic autonomy for scholars to conduct their research without fear or favour. Despite constitutional guarantees of academic freedom, academics face multiple threats from populist politicians, dubious third party funding, uncivil society, and misguided developments within German academia itself. These domestic threats are exacerbated on the international stage by the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) globalised censorship regime, dubious party-state funding from China, the weaponisation of informal Chinese social networks, and an unhealthy dependency among Western China scholars on ‘official China’. The authors reveal that the German state, universities, and learned societies have so far failed to properly identify – let alone mitigate – threats to academic freedom emanating from state and non-state agents under control of the CCP. They argue that while German parties have largely abdicated political leadership, German universities exhibit shortcomings in terms of their ethical leadership. Drawing on an in-depth analysis of a controversial statement by the Board of the German Association for Asian Studies (DGA) the authors argue that leading China scholars also seem unwilling or unable to exercise intellectual leadership. The article concludes with policy recommendations to remedy this problem.

Introduction

Very interesting positioning, indeed. It should've been titled: ‘The attempt to stay neutral’. Which is the main problem of the text! You may not want to share a Trumpian perspective or might abhorr a CCP perspective, but you can't ‘stay neutral’, even if you'd like to, @klamuhFootnote1

Such an arrogant statement that doesn't even pretend to be not arrogant!Footnote2

On 20 June 2020 the Board of the learned society German Association for Asian Studies (DGA) published a statement titled ‘Beware the polarisation’.Footnote3 It addressed ‘the geopolitical consequences of the Corona crisis and the role of modern Asian Studies’.Footnote4 Following its publication the statement was criticised on social media. The prominent German MEP Reinhard Buetikofer accused the authors of fence sitting. The Brussels-based journalist Stuart Lau considered it as highly patronising.

This conceptual article situates DGA's controversial statement in the global discourse about the fraught relationship between academia and (geo-)politics. In this article we address two research questions: What are the biggest domestic and international threats to academic freedom in Germany? And to what extent does the DGA statement attempt to mitigate risks emanating from the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) attacks on independent academia? Treating the DGA statement as a revelatory case study we argue that it sheds light on deep-seated structural problems in German academia in general and Chinese Studies in particular. Our research reveals that the German state, universities, and learned societies have so far failed to properly identify – let alone mitigate – threats to academic freedom emanating from state and non-state agents under control of the CCP. We conclude our article with specific policy recommendations to remedy this problem.

Knowledge production with German characteristics

The internationalisation of higher education has implications for academic freedom worldwide. The national context of Germany, however, has so far attracted only little attention. At the heart of this article lie often overlooked undercurrents which are influencing knowledge production in Germany.

One of these undercurrents is the contested relationship between science, the state, economy and society. In their seminal study ‘The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies’ (1994) Gibbons et al argue that

(science) does not stand outside of society dispensing its gifts of knowledge and wisdom; neither is it an autonomous enclave that is now being crushed under the weight of narrowly commercial or political interests. On the contrary, science has always both shaped and been shaped by society in a process that is as complex as it is variegated; it is not static but dynamic.

Other undertows relate to competing modes of knowledge production. Gibbons et al distinguish between Mode 1 and Mode 2. Gall et al. have explained them as follows:

(while) ‘Mode 1’ research follows a linear model, refers to the conventional production of scientific-expert knowledge, is traditionally organised around universities and is mainly disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, ‘Mode 2’ knowledge is produced in the context of application, in problem solving, and in the spaces formed by relationships.Footnote6

Bresnon and Burrell have pointed out that Mode 1 arose in nineteenth century Germany. They write that

(in) Germany, the banks and industrial corporations were much more closely allied than they were in the British context and it should not surprise us that it was there that the reforms of the university system to create Humboldt’s vision of a university in the service of the State arose.Footnote7

When discussing the origins of scientific inquiry in Germany Dahrendorf has similarly argued that

there were two notions of science, the experimental and the German, and this to him was crucial. ‘Knowledge by conflict corresponds to government by conflict … At any given time, a lively conflict of minds provides the market of science with the best possible result of knowledge.’ On the other hand, ‘knowledge in the sense of both speculation and understanding [the German way] does not require debate. This resulted, he said, in a particularly German idea of truth, not one battered out by public debate, after a set of experimental results, but instead a way of ‘certain knowledge’ available ‘at least for the chosen few’ (i.e. the experts).Footnote10

Another tension in the field of German academia concerns the relationship between science and politics.Footnote12 Weber advocated a separation between the roles of a supposedly neutral scholar and an expert who is free to express political viewpoints as a pundit. Whilst Weber's ‘freedom from value principle’Footnote13 has coexisted with alternative concepts of ‘the political’ (‘das Politische’) by German thinkers like Habermas and Arendt, it nevertheless had a lasting effect on German academia.Footnote14 Attempts were made throughout the 1960s to critically assess the fact/value dichotomy during the positivism dispute (Positivismusstreit). Also referred to as the value judgment dispute (Werturteilsstreit) this debate between proponents of a ‘qualitative-hermeneutic approaches and those of quantitative-metrifying methods’Footnote15 came to a preliminary end in 1969 without a conclusive result. Dahms has rightly pointed out that subsequently ‘the discussion that had begun came to a standstill in the day-to-day operations of the mass university and then completely silted up’.Footnote16 But while academics in Germany may disagree whether they shall seek ‘certain’ or ‘experimental’ knowledge and what role universities should play in their respective communities, genuinely pluralistic knowledge production will arguably only be possible if the ecosystem of organised academia in Germany provides sufficient academic autonomy for scholars of all disciplines and persuasions to conduct their research without fear or favour.

Domestic threats to academic freedom in Germany

Academic freedom is enshrined in Germany's Basic Law under Article 5 (‘Art and scholarship, research, and teaching shall be free’).Footnote17 Germany's Constitutional Court has made it clear that academics employed by German universities enjoy a high degree of autonomy. The German state has thus devolved considerable power allowing German scholars to develop organisational norms which are commensurate with the goal of academic freedom as part of their self-governance. At the same time, academic autonomy in Germany is circumscribed by numerous other factors. Tiffert has argued that ‘(intellectual) freedom flourishes only so long as we sustain and invest in the ecosystem that supports it, and that ecosystem is prone to exploitation and despoilment by those with incompatible agendas.’Footnote18 On the domestic front, we distinguish between four major threats emanating from populist politicians, dubious third party funding, uncivil society, and misguided developments within German academia itself. What follows is a brief overview of the nature of these four threats.

Populist politicians

Germany has always had its fair share of fringe political parties which have had little qualms to interfere in academic autonomy. One contemporary example is the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). This right wing party recently proposed to cut all funding for gender studies at German universities.Footnote19 Nettesheim, the founder of the newly established German Network Academic Freedom describes the challenge as follows:

Science is not a handy-man of politics. Science will insist that excessive politicization through legal or social control of issues and results will impair its functional value (…) Anyone who tries to intervene here with moralization, irrelevant arguments or political criteria fails to recognize the challenge.Footnote20

Uncivil society

Academics in Germany also face growing pressures from societal actors who no longer believe in the merits of science and freedom of speech. With the help of social media anti-vaxxers or flat earth conspiracy theorists can communicate and mobilise across national boundaries. It is widely acknowledged that social media can have a corrosive effect on public debate,Footnote21 especially when legitimate critiques of positions held by academics degenerate into ‘trolling, “doxxing” (publicizing someone’s personal details such as home address and phone number without consent), or (…) public shaming’.Footnote22 Incessant public shaming of the German virologist Drosten for his Covid-related research mark a new low in this regard.Footnote23

Questionable third party funding

Threats to academic autonomy, however, are not only political in nature. An over-reliance on third party funding can also create threats to academic freedom. Partnerships between universities, industry and government – commonly referred to as the triple helixFootnote24 – are often lauded as an engine of innovation. One only needs to think of a pharmaceutical company supporting a university-based science lab in the rapid development of life-saving vaccines to see the tangible benefits of such public-private partnerships. Yet the flip-side of ever increasing malleability of the boundaries between academia and industry is that ‘commercial interests increasingly determine which scientific approaches are followed and how research results are presented.’Footnote25 This is all the more a problem since by now one in four posts at German universities are funded by third parties.Footnote26 Non-transparent and unaccountable third party funding furthermore runs the danger that universities engage in reputation laundering for corporate entities, e.g. by allowing Gazprom to sponsor an opulent dinner at an academic conference in Berlin.Footnote27

Misguided developments within German academia

The question whether academic freedom is sufficiently protected requires us to also briefly examine the impacts of financialisation and performance evaluation based on reductionist metrics. In theory Germany, just like the Netherlands, could be considered ‘a less market-based and a more negotiated, coordination-oriented political economy (2001)’Footnote28 and thus German universities should ‘be well protected against the forces of financialization to which the UK and US-based universities are especially subjected’.Footnote29 Yet in the wake of the Bologna processFootnote30 German universities were subject to cost-cutting measures and increasingly fierce inter-university competition. The reforms led to the emergence of the ‘entrepreneurial university’ in Germany, in which the size, role and function of administrators has steadily grown at the expense of academic faculty staff.Footnote31 The financialisation of German academia has also led to the introduction of reductionist performance evaluation. The numbers of published articles, the value of raised third party funds or registered patents are now key performance indicators (KPI). Becker highlights that German ‘researchers are stuck in a corset of formal measured values that ultimately limit their scientific freedom. Deviations are punished with career disadvantages – even if these were scientifically productive in terms of content’ .Footnote32

International threats to German academia: the case of China

The aforementioned four domestic threats to academic freedom are mirrored on the international stage. In the following we examine how the CCP has started to mould western academia in its own image. International threats to academic freedom lie in the CCP's globalised censorship regime, dubious party-state funding from China, the weaponisation of informal Chinese social networks, and an unhealthy dependency among Western China specialists on ‘official China’.

CCP's global censorship regime

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, the Chinese higher education (HE) sector has been subordinate to the whims of the party-state.Footnote33 During the Cultural revolution Chinese HE institutions were destroyed to such a degree that in 1979 the Ford Foundation was invited help with the reconstruction effort by providing ‘funding for academic and professional exchanges between institutions in China and their counterparts in the US.’Footnote34 And while during times of political thaws (e.g. mid-1980s, early 2000s) Chinese academics have enjoyed greater license to address issues which are considered sensitive by the CCP, the party-state has never granted scholars intellectual independence along the lines of the 1997 UNESCO Statement on Academic Freedom.Footnote35

Following General Secretary Xi Jinping's ascent to power in 2012, the CCP first weaponised Chinese academia through the party directives Seven Don’t SpeaksFootnote36 and Document No 9 (2013).Footnote37 In 2019 the party-state imposed changes on university charters such as ‘dropping the phrase “freedom of thought” and the inclusion of a pledge to follow the Communist party’s leadership’.Footnote38 This is just one building block of a broad trend towards the political annihilation of dissonant voices and a totalitarian Gleichschaltung of Chinese academia, society, media by a unified narrative, strictly controlled by the party-state – a trend which could be observed in action at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis.

Investigating the phenomenon of ‘learned acquiescence’ among Chinese intellectuals Perry has highlighted that ‘Chinese universities have introduced new regulations that encourage intellectuals to align their academic output even more closely with official priorities’.Footnote39 Many academics whose voices were considered as political threats have been heavily sanctioned, often by terminating their employment contract, sometimes even by cancelling their right to pension and sometimes by long, arbitrary prison sentences. According to Cai Xia, a former renowned professor at the Central Party School

over the course of (Xi Jinping’s) tenure, the regime has degenerated further into a political oligarchy bent on holding on to power through brutality and ruthlessness. It has grown even more repressive and dictatorial. A personality cult now surrounds Xi, who has tightened the party’s grip on ideology and eliminated what little space there was for political speech and civil society. People who haven’t lived in mainland China for the past eight years can hardly understand how brutal the regime has become, how many quiet tragedies it has authored.Footnote40

Hotz-Hart has furthermore pointed out, that ‘the authorities have started to influence the academic discussion also in other countries’ under the pretext of defending the national sovereignty of China, which nowadays means defending the leadership of the party-state, the so-called centre.Footnote41 The CCP has now codified its illiberal values in form of the Hong Kong National Security Law (2020).Footnote42 In an open letter more than 135 globally leading academics decried the ‘national security law, which under article 38 is global in its scope and application, will compromise freedom of speech and academic autonomy, creating a chilling effect and encouraging critics of the Chinese party-state to self-censor.’Footnote43 The proliferation of highly illiberal party edicts and laws make it clear that the party-state sees independent academia at home and abroad as a threat to its authority.

A particular egregious example of the CCP's globalising censorship regime are CCP sanctions against the European scholars Jo Smith Finley, Björn Jerdén and Adrian Zenz as well as the Berlin-based think tank Merics.Footnote44 These were issued in direct response to sanctions imposed by the EU, UK, US and Canada on four Chinese officials and one Chinese entity implicated in the crimes against humanity in Xinjiang. This prompted thirty directors of research institutes to express their concern about the ‘targeting [of] independent researchers and civil society institutions [which] undermines practical and constructive engagement by people who are striving to contribute positively to policy debates’.Footnote45

The CCP's political warfare against independent academia is organised by the United Front Work Department, which according to Mattis ‘includes mobilizing overseas Chinese to support friendly politicians and official narratives as well as sponsoring research at foreign academic institutions’.Footnote46 Confucius Institutes serve to foster China-related self-censorship at western universities.Footnote47 A report by Jamestown Foundation revealed that

organizations central to China’s national and regional united front systems spent more than $2.6 billion in 2019, exceeding funding for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (…) Nearly $600 million (23 percent) was set aside for offices designed to influence foreigners and overseas Chinese communities.Footnote48

Weaponisation of informal Chinese social networks

While a political discourse on influence by the CCP on academic freedom has been an ongoing public debate in many democracies around the world for many years, this debate in Germany has only started within the past two years. Moreover, the public debate in Germany mainly focusses on the role of Confucius Institutes as shown by several parliamentary inquiries on this issue. Other issues threatening academic freedom, such as intimidation of Chinese students and scholars by CCP representatives have been briefly recognised by the Federal Government but not addressed.Footnote50

It is widely known that the Chinese party-state is weaponising students to monitor their university instructors in mainland ChinaFootnote51 and Hong Kong.Footnote52 Such attempts do not stop at China’s border. Frangville has revealed that the Chinese embassy in Belgium tried to hire Brussels campus students to express their disapproval of a Uyghur demonstration in 2018.Footnote53 Thorley has highlighted the ‘weaponization of informal Chinese social networks by the Party-state’.Footnote54 Referring to the Chinese Student and Scholars Associations as ‘latent networks’ Thorley points out that the CCP ‘manifests itself most forcefully only at times, or relating to subjects, it considers critical’.Footnote55 Such phenomena are seldom discussed, whether in the German or global discourse. When a courageous Australian academic analysed this thorny issueFootnote56 his attempts to understand how the Chinese diaspora is being influenced by the CCP was quickly denounced as a ‘witch hunt’.Footnote57

Suspicious party-state funding

Academic freedom is also at risk from dubious party-state funding. German universities such as TU Berlin and TU München have receive hundreds of thousands of euros from companies such as Huawei. The University of Göttingen, University of Freiburg and University of Bremen have accepted funding from PRC entities which are directly controlled by the CCP. Many degree programmes at German universities could not be offered without funding from PRC entities.

In most of the German state’s freedom of information (FOI) laws, higher education institutions are excluded and therefore not accountable to the public regarding funding received from authoritarian actors and the conditions of this funding.Footnote58 Ironically, the exclusion of universities from FOI laws is justified under the pretext of ‘the constitutional rights of science and research’, which according to court rulings based on restrictive FOI laws should not be ‘jeopardize[d]’ by access to information and must be ‘protected […] from interference by third parties, if necessary’.Footnote59

In only four German states, FOI laws include higher education institutions.Footnote60 Thanks to a local FOI law the public learned about a highly problematic contract between a PRC education ministry agency (the Hanban) and the Free University of Berlin (FU Berlin). In this contract, inter alia, the university agrees to adhere to Chinese law and an annual evaluation by the Chinese side. In case of failing the evaluation or contravening Chinese law, Hanban has the right to terminate the cooperation and in some cases even can demand a refund of previously paid funds. Due to public pressure regarding the problematic legal terms, the Berlin state government demanded the FU Berlin to renegotiate the contract. This is the only case known to the authors, where the German state tried to protect academic freedom from Chinese influence.Footnote61

German universities which depend on the funding are at a high risk of conducting self-censorship to not lose this funding.Footnote62 The recently published ‘Guiding questions on university cooperation with the People’s Republic of China’ by the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK) reveals a general awareness about the China-specific challenge from the vantage point of the association of public and government-recognised universities in Germany.Footnote63 Yet while they call for ‘transparent communication’, which should ‘document [the universities] cooperation activities with China, the objectives and the foundations of the cooperation in a manner that can be understood by the general public’ the HRK does not offer actionable remedies.

A vast majority of German universities do not provide any transparency about their funding from PRC sources when asked to do so, thus raising doubts about the efficacy of HRK's soft approach to change management.Footnote64

Unhealthy dependencies on ‘official China’

Individual researchers and learned societies representing these researchers could form an opposite pole to a passive state and university administrators who fail to protect academic freedom against CCP interference. Unfortunately, some of the leading German China specialists try to enjoy the best of both worlds: by playing the role of the China expert in the western discourse who is (mildly) critical of the party-state, whilst signalling virtue to the regime by including key CCP talking points in their public statements. This phenomenon is best exemplified by a wide-ranging interview which the German Sinologist Schmidt-Glintzer gave NZZ Standpunkte in 2017.Footnote65 In one of his answers he rightly critiques the Chinese political system for unnecessarily curtailing citizen participation. Yet in the same answer he also makes excuses for the party-state's draconian Overseas NGO Law, which he describes as a ‘catch up development’. The fact that the law has not only destroyed trust networks between Western and Chinese civil societyFootnote66 but also prevents more cooperative state-society relations in China does not seem to matter. His widely inconsistent views should not be interpreted as nuance, as the former insight contradicts the latter. Johnson describes this as ‘Sinologists wanting to have it both ways – being experts at home and accepted in China’.Footnote67

Such attempts at triangulation do not inspire confidence in the impartiality of German China experts as honest ‘knowledge brokers’.Footnote68 Many China scholarsFootnote69 in Germany also collaborate with local Confucius Institutes while at the same time claiming that they are ‘not a representative of any interest group’.Footnote70 The euphemism inherent in such a statement is laid bare in a position paper signed by a group of China academics aiming to justify the existence of Confucius Institutes at German universities, which was sent to more than 200 parliamentarians in August 2020.Footnote71 Such lobbying efforts reveal that they are an interest group. It also reveals an unhealthy dependence among some German China scholars on what could be termed ‘official China’. Their desire to maintain party-state funding and access to China appear to outweigh any other considerations related to ethical due diligence and reputation management.Footnote72

A critique of the DGA statement ‘beware the polarisation’

A major learned society in the field of Asian studies, the DGA also misses the opportunity to stand up for academic freedom as this section will show. In the DGA statement titled ‘Beware the polarization’ (henceforth referred to as ‘the statement’) – which was already mentioned in the introduction – DGA Board members laud the virtues of taking a supposedly ‘neutral’ position when it comes to China. As we will show such a supposedly apolitical position in fact is highly political.

Two assertions stand out in particular. The authors grudgingly concede that ‘(we), of course, accept if scholars engage in political discourses or reflect about their personal position to critical issues of our time’, but not without adding a caveat to such exercise of free speech. They go on to argue that ‘(however), we oppose any attack against scholars for their scholarly attitude of questioning positions, for looking deeper and for sometimes opposing to the mainstream.’ While the call for civility in public discourse is unobjectionable, the statement also makes it clear that it relegates free speech and academic freedom to what Frank Furedi calls a ‘second-order value’.Footnote73 Whereas ‘opposing the mainstream’ could be seen as granting academics license to engage in contrarian thinking, the authors also argue that ‘Cold war rhetoric and de-coupling fantasies are combined as if there were no alternatives. For many countries in Asia-Pacific and Europe this is no reasonable choice given the complex supply chain networks which have emerged over the past decades.’

Given that the global discourse about possible western de-coupling from China is rather new, it becomes clear that the DGA Board is in fact defending a rather mainstream view among establishment academics that there is no alternative to deepening Western economic entanglement with China. With their explicit support for ever closer economic integration between Europe and China the authors mirror German Chancellor Merkel's mercantilist approach.Footnote74 The latter, however, is not supposed to be challenged, thus reflecting Merkel's politics of ‘no alternative’ (Alternativlos).Footnote75 More worryingly, by speaking of ‘Cold war rhetoric and de-coupling fantasies’ the DGA statement's framing is not dissimilar from the ultra-nationalist party-state mouthpiece Global Times.Footnote76

Such a normalisation of the CCP's political rhetoric directly benefits the party-state, which aims to create an atmosphere where it can claim that a vast majority of foreigners supports its rule and only a small minority of ‘enemies of the people’ opposes it. And while academics are supposedly free to state their political views and allowed to question group think, the DGA statement itself can be seen as a rather explicit warning to scholars in the Asian Studies field not to attempt to address thorny issues such as the cooptation of German industry by Chinese SOEs,Footnote77 Europe's over-reliance on China-manufactured PPE during the Covid-19 crisis,Footnote78 or the weaponisation of multinational corporations doing the CCP's bidding.Footnote79 The statement establishes nothing short of a dogma, which tells the reader not to challenge Western commercial engagement with China. This underscores Schmoll's observation that in Germany ‘the academic controversy has been forgotten, whoever fostered it was all too often marginalized as a troublemaker.’Footnote80

The statement is also let down by a reductionist view of geopolitics, which is exclusively seen through the lens of great power rivalry between the US and China. The remedy is a vague call for global action: ‘If the rest of the countries joined hands to reign into this bifurcated narrative, new option (sic) could arise’. The term ‘Germany’ is not mentioned even once. The authors do not offer any reflections on the current state of Sino-German relations. The role of sovereign nation-states is only indirectly touched upon, e.g. when the authors mention ‘national policies’, ‘some countries’, or bemoan ‘protectionism and nationalism’ prior to Covid-19. The German government which could articulate a different China policy does not feature, neither as a unit of analysis nor as an activity field for German academics providing foreign policy advice. The statement also fails to provide any specific advice to European Institutions. Instead it attempts to address issues exclusively on an individual and global level.

The statement is also remarkable for its inability to address misguided developments in Asian Studies. At one point the authors lament that

the scholarly community is increasingly confronted with the bifurcated narrative mentioned above for their positioning as researchers. Scholars are expected to take sides. The attempt to stay neutral and contribute to understanding rather than fuelling the conflict is either interpreted as weakness or even as moral decay.

The statement also doesn't offer any advice on how academics can deal with the CCP's political censorship other than engage in self-censorship. The latter phenomenon has been extensively discussed by Greitens and Truex in their widely noted research article ‘Repressive Experiences among China Scholars: New Evidence from Survey Data’. They found that ‘most China scholars believe their research to be sensitive; a majority adapt their conduct to protect themselves and others; and most express concern about potential self-censorship.’Footnote81 Asian Studies scholars need to be mindful that their pre-scientific value choices and world views will inevitably shape their scholarship – therefore, an ‘objective science’ is impossible. Applied to the case of China, Weber's ‘freedom from value principle’ carries enormous risks. According to Kränzle ‘(the) dispensation of science from the normative opinion has also made it submissive to powers by which it can be abused at the utmost as a victim and servant of dubious objectives.’Footnote82 His warning aptly captures the conundrum of Chinese Studies in Germany. Many China scholars exercise self-censorship by being silent on the civil rights movement and its severe repression in China and even much less willing to publicly support it whilst defending the view of the CCP that China is ‘not suited’ for democracy. In 2010 the German journalist Kai Strittmatter bemoaned a ‘silence across the board’Footnote83 among many German China experts. He also observed that those China scholars who were speaking in public had a tendency to ‘seek understanding for the Chinese government’.Footnote84 Besides financial and cooperative ties with Chinese counterparts rather peculiar epistemological choices by German China scholars contribute to this posture. According to Roetz a reason for this ‘sympath[y] […] with the dictatorial regime’ being ‘a syndrome of culturalistic, relativist, and exotic convictions’, i.e. many sinologists see Chinese people as ‘the Other’ not being able or willing to oppose dictatorship due to cultural or historical reasons.Footnote85

The statement furthermore complains that Asian Studies scholars are not heard enough by the public, that ‘[a]ttracting attention to their insight proved difficult’. When confronted with the lack of a public profile among many leading German China specialists a scholar responded by saying that they are discussing all topics in their ‘adequate’ forum, i.e. academic publications, or behind closed-door–courses at universities.Footnote86 Yet it is also true that relegating the discourse about human rights violations in China to closed door discussions is in the interest of the CCP.Footnote87 Such a defence of Ivory tower Mode 1 knowledge production also neglects the fact that while journalists have the duty to obtain information (Holschuld), scholars have the duty to provide these (Bringschuld). And while comments such as ‘Twitter is not the only outlet on which one can express oneself’Footnote88 are not completely wrong, it has now become an important public sphere where the global discourse on China takes place. Twitter has also become a marketplace of ideas where many journalists find academics who are willing to share their expertise with the wider public.

Last but not least the statement complains that ‘the discourse on China is dominated by representatives of think tanks that are […] (co-)financed by the parties of the dual conflict’. The authors assume this critique being an indirect swipe against the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) or perhaps also the German Marshal Funds of the United States (GMFUS). This complaint is questionable as at least the MERICS is nearly completely funded by a German foundation, and also the GMFUS receives extensive funding from European countries.Footnote89 Moreover, while criticising this think tank funding, the authors remain completely silent about Chinese financial support for German universities and stress that they would like to ‘encourage the public to take more advantage of the independent research and findings of scientists that our publicly funded university system and other politically neutral research institutions produce (emphasis added)’. How ‘independent’ and ‘neutral’ this research amid massive funding from China really can be is debatable. It is highly problematic that the DGA statement does not mention this funding by a ‘part[y] of the dual conflict’ at all.

How to better address the political dimension of Asian studies

The DGA statement reveals a profound lack of understanding of the Chinese Communist Party's threat to academic freedom. Due to its polemical and polarising nature it is rather unlikely that the statement will contribute to raising sector-wide standards and help its members in developing more reflexive practices. The dogmatism inherent in the DGA statement carries the danger of a ‘double bind’, whereby unfounded allegations against outspoken critics of the CCP could lead to an overreaction of the accused making their own unreasonable demands on German China scholars having to subscribe to a however defined ‘politically correct’ form of China-related knowledge production. To prevent such a vicious circle we suggest the following three mitigating measures.

We argue that there cannot be academic excellence without a robust defence of academic freedom. As a minimum, China specialists should openly discuss the dangers of the CCP's globalising political censorship regime and critically assess the issue of individual and institutional self-censorship. Teng Biao has rightly pointed out that ‘(most) Chinese intellectuals practice self-censorship, as do most international scholars focusing on China.’Footnote90 Instead, he calls on western academics to follow Havel's maxim of ‘living in truth’. Teng argues that ‘(the) most horrible autocracy is not the one that suppresses resistance, but the one that makes you feel that it is unnecessary to resist, or even makes you defend the regime.’Footnote91 It is heartening that in response to the illiberal Hong Kong National Security Law more than one hundred signatories of an open letter representing 71 academic institutions across 16 countries have exercised solidarity by pushing back against the CCP's authoritarian overreach, including three China specialists working at German universities. And following the CCP sanctions in March 2021 one thousand three hundred and thirty-six academics signed a public statement in which they ‘[expressed] solidarity with all our persecuted colleagues’. It signified a rare act of public defiance against the CCP's authoritarian overreach. The statement was co-signed by eighty China scholars working for German universities.Footnote92

Western China specialists also need to be conscious that while the CCP under Xi Jinping seeks a Gleichschaltung of Chinese academia, civil society and media under a unified narrative this remains a totalitarian ambition, not yet a fait accompli. Western China scholars should continue to research both what could be termed ‘official China’ (represented by the party-state) and ‘unofficial China’ (which includes independent-minded academics, doctors, entrepreneurs, citizen journalists, public interest lawyers and young students who no longer accept the CCP’s rule by fear) as well as the interactions between ‘official China’ and ‘unofficial China’. It should also be more widely recognised that Western scholars who publicly critique the CCP are routinely subject to cyber bullying and smear campaigns carried out by state or non-state agents acting on behalf of the party-state.Footnote93 Academics who incur the wrath of the CCP for their critique of the party-state's authoritarian overreach deserve solidarity and support by their respective universities, learned societies and parliamentarians alike.

Last but not least greater attempts should be made to strike a better balance between a generalist and specialist approaches to the study of contemporary China. Barmé reminds us that ‘all too often modern disciplinary specialisation limits the conception of the Chinese world, a world that has always placed such great faith in the holistic understanding of the full range of interwoven human activities’.Footnote94 Greater efforts should be made to analyse China simultaneously from holistic and reductionist perspectives. This is particularly important when dealing with what Hoffman has refered to as ‘China's tech-enhanced authoritarianism’.Footnote95 A closer study of China's smart city technologies, eg the widespread use of CCTV cameras, can reveal that in the case of the PR China technology will always have ‘dual use’Footnote96: whilst the CCTV cameras can help solve local problems such as traffic congestion (a reductionist perspective), they simultaneously augment the central party-state's ability to exercise social and political control through grid management (a holistic perspective).Footnote97

Conclusion

Our research reveals that the German state, universities, and learned societies have so far failed to properly identify – let alone mitigate – threats to academic freedom emanating from state and non-state agents under control of the CCP. We conclude our article with specific policy recommendations to remedy this problem. Key stakeholders will have to exercise more decisive leadership. When it comes to the role of the German regulatory state, German parties appear to have largely abdicated their political leadership role. On the federal level only the Greens as well as the FDP have paid some attention to the relationship between German academia and China. A recent example is the motion by the FDP to ‘Protect research and teaching – Ending the cooperation between German universities and China's Confucius Institutes’.Footnote98 On the state level various other parties – typically those who are in opposition – have sporadically raised concerns about Confucius Institutes at German universities. None of these activities on state or federal level have led to any new legislation aimed at addressing the CCP's threats to academic freedom in Germany. While the most recent FDP motion calls for the establishment of an expert commission investigating the influence and interference of the CCP on German academia we suggest that such measures are too compartmentalised. Instead, the there is a need to establish an whole-of-government task force which critically examines the systemic challenge of the CCP. Such a task force should not only address the issue of academic freedom but also investigate the threat of industry cooptation, IP theft, cyber attacks and disinformation campaigns, harassment of the Chinese diaspora, hostage diplomacy, etc. In terms of the task force composition key stakeholders to be involved are The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, The Federation of German Industries (BDI), BMBF and other relevant ministries and agencies. It should be tasked to develop suggestions for actionable counter-measures for key stakeholders on the federal and state level.

German universities, on the other hand, exhibit serious shortcomings in terms of their ethical due diligence. University administrators so far have failed to show ethical leadership, e.g. by ensuring greater transparency and accountability about the Chinese party-state funding for universities. Inaction by universities will only be curtailed if all German states start including universities in their FOI laws and make it less expensive for investigative journalists to obtain relevant information. The BMBF, in conjunction with the HRK, have so far failed to provide political guidance which goes beyond supporting the strengthening of China competence at German schools and universities.Footnote99 While such soft methods of mainstreaming China competence are to be welcomed there is also a need for hard measures of change management, e.g. HRK-led audits of university compliance with new transparency and accountability requirements.

And with its controversial public statement, the Board of the DGA has failed to exercise intellectual leadership. Board members may want to consider the words by Desmond Tutu, who famously said that ‘(if) you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor’.Footnote100 Roetz said it best in an op-ed for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in 2011: ‘Sinology is not a neutral “outsider” (…) She is part of the problem she's talking about.’Footnote101 Rather than pacifying the public debate the statement from 2020 could be seen as highly incendiary, as it not only fails to address misguided developments in German academia but also paints legitimate critique of the Chinese party-state as Cold War rhetoric. As a leading learned society for Asian Studies in Germany, the DGA has special responsibility to help develop sector-wide standards and protocols aimed at protecting academic freedom. The 12-point Code of Conduct by Human Rights Watch on how HE institutions like ‘colleges and universities [can] respond to Chinese government threats to the academic freedom of students, scholars, and educational institutions’Footnote102 could serve as a useful starting point. The DGA could also consider adopting recommendations about Sino-German academic cooperation by the Deutsche Vereinigung für Chinastudien e.V. (DVCS) from 2018 either in part or in full.Footnote103 The DGA could also make the case for full disclosure of third-party funding by German universities. Greater transparency would empower academics to critique unhealthy financial dependencies in their home institutions. Less reliance on funding from PRC sources could also help reduce self-censorship among China scholars.

The widespread abdication of leadership now risks to entrench censorship and self-censorship in academia, which in the medium – to long-term will severely undermine national and democratic securityFootnote104 in Germany. It should be a concern for both the German state and civil society that so far neither politicians nor academics have come up with sensible suggestions on how to mitigate such risks. While we do not wish the German state to directly interfere in the self-government of German universities, it has a constitutional obligation to mitigate domestic and international threats to academic freedom. This will require a political debate about the merits and demerits of relying too much on third party funding in general and from the Chinese party-state in particular. The German state also has to create a regulatory framework for greater transparency and accountability of German universities. This will require reforming FOI laws at the federal and state level.

Last but not least it is incumbent upon German academics to critically reflect on their respective position towards the Chinese party-state. Attempts by individual academics to try to enjoy the best of both worlds need to stop. At the minimum the evident conflict of interest should be transparent for all, in view to facilitate accountability and public questioning. Here we would like to emphasise that neither do we advocate a hegemonic view of ‘correct’ ways of knowledge production – Mode 1 and Mode 2 will co-exist for the foreseeable future – nor do we prescribe a particular political position that academics should take. At the same time, we would welcome if more China specialists were willing to publicly acknowledge, analyse and critique the totalitarian turn in Xi's China. At the very least German China scholars should be upfront with members of the public how their prescientific value orientations and long-held views of what constitutes a good state and society inform their respective takes on current Chinese affairs. Such a reflective attitude would also go a long way in facilitating a more respectful professional and public discourse about sensible strategies how to best mitigate the threats of the Chinese Communist Party to academic freedom in Germany.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andreas Fulda

Andreas Fulda is Associate Professor at the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham and the author of The Struggle for Democracy in Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong: Sharp Power and Its Discontents.

David Missal

David Missal holds a master’s degree in Journalism from The University of Hong Kong. During his studies, he lived in Nanjing, Beijing, Berlin and Hong Kong. He has organised several campaigns focusing on China’s influence in Germany as well as human rights issues in China.

Notes

1 Reinhard Bütikofer @bueti, ‘Very interesting positioning, indeed. It should’ve been titled: “The attempt to stay neutral”. Which is the main problem of the text! You may not want to share a Trumpian perspective or might abhorr a CCP perspective, but you can’t “stay neutral”, even if you’d like to, @klamuh’, Tweet from June 14, 2020, bit.ly/3qQS4T3

2 Stuart Lau @StuartKLau, ‘Such an arrogant statement that doesn’t even pretend to be not arrogant!’, Tweet from June 15, 2020, bit.ly/3aOVMXB

3 DGA. ‘Beware the polarisation’, https://bit.ly/3kn94h9

4 Ibid.

5 Peter Watson, The German Genius. Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution and the Twentieth Century (London: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 764.

6 STACS, ‘Participation of Civil Society Organisations in Research’, https://bit.ly/3kjMINz

7 Mike Bresnen and Gibson Burrell, ‘‘Journals à la mode? Twenty Years of Living Alongside Mode 2 and the New Production of ’Knowledge’, Organization 20, no. I, (2012): 34.

8 Lenore O’Boyle, ‘Learning for its Own Sake: The German University as Nineteenth-Century Model’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 25, no. 1 (Jan. 1983): 11.

9 Peter Kühl, ‘Die deregulierte Hochschule ist ein Mythos’, Forschung & Lehre, https://bit.ly/3tj9Wb2.

10 Peter Watson, The German Genius. Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution and the Twentieth Century (London: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 764.

11 Manfred Ronzheimer, ‘Raus aus dem Elfenbeinturm’, taz, June 24, 2018. https://bit.ly/3DMk2Gi.

12 Karl Kränzle, ‘Entpolitisierte Wissenschaft — verwissenschaftlichte Politik’, https://bit.ly/2P6IrSe

13 Hans-Günther Assel, ‘NORMEN IN DER POLITIK: Eine Kritische Betrachtung Zum Wertfreiheitsprinzip Max Webers’, Zeitschrift Für Politik 16, no. 2 (1969): 198–222.

14 The authors would like to thank Reviewer 2 for highlighting that Hannah Arendt and Jürgen Habermas have not been without influence and that their assumptions about the relationship between scientific truth and value differ greatly from Weber’s.

15 Gerald Wagner, ‘Ein Quexit in der Soziologie?’, FAZ, January 23, 2019, bit.ly/3bgpjtw.

16 Hans-Joachim Dahms, Positivismusstreit (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag), 15.

17 The Federal Government, ‘Basic Law’, https://bit.ly/3sn65YR.

18 NED, ‘Compromising the Knowledge Economy’, https://bit.ly/37KwBnb.

19 Science.Lu, AfD will Gender-Forschung ausbremsen - SPD: Angriff auf Wissenschaftsfreiheit, https://bit.ly/3sn6sTf.

20 Thomas Thiel, ‘Wir erleben eine Refeudalisierung der Diskussion’, FAZ, February 10, 2021. Please note that all translations from German to English are by the authors, unless otherwise noted.

21 Matthew Moore, ‘Twitter has Corrosive Effect on Debate, Says Jonathan Dimbleby’, The Times, October 9, 2018. https://bit.ly/3dDHifb.

22 Sara Polak and Daniel Trottier, eds, Violence and Trolling on Social Media (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020), https://bit.ly/3somZqc.

23 Scientists for Future, ‘Gegen Angriffe auf die Wissenschaft’, https://bit.ly/3uvcWkM.

24 G. Fuerlinger, U. Fandl, and T. Funke, ‘The Role of the State in the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem: Insights from Germany’, Triple Helix 2, no. 1 (2015): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40604-014-0015-9.

25 Matthias Becker, ‘Die Grenzen der Forschungsfreiheit’, Deutschlandfunk Kultur, https://bit.ly/3qPT35H. For a critique of corporate funding of university-based vaccine research see also Ilari Kaila and Joona-Hermanni Mäkinen, ‘Finland Had a Patent-Free COVID-19 Vaccine Nine Months Ago — But Still Went With Big Pharma’, bit.ly/2Pww1mP.

26 Ibid.

27 Deutsche Welle, ‘Made in Germany Porträt Lars Hendrik Röller’, https://bit.ly/3pOb9UB.

28 Reijer Hendrikse, How finance penetrates its other: A cautionary tale on the financialization of a Dutch university, Reijer Hendrikse, The Long Arm of Finance, PhD thesis, 39.

29 Ibid.

30 Guy Neave and Amélia Veiga, ‘The Bologna Process’, Higher Education 66, no. 1 (2013): 59–77.

31 Matthias Becker, ‘Die Grenzen der Forschungsfreiheit’.

32 Ibid.

33 Immanuel C. Y. Hsu, ‘The Reorganisation of Higher Education in Communist China, 1949-61’, The China Quarterly (London) 19 (1964): 128–60. Web.

34 Ford Foundation, ‘Our work around the world China. History’, https://bit.ly/3hkzlMW

35 Dondald C. Savage and Patricia A. Finn, ‘The Road to the 1997 UNESCO Statement on Academic Freedom’, https://bit.ly/2YKWVfl.

36 David Bandurski, ‘Control, on the shores of China’s dream’, China Media Project, bit.ly/2MquM7C.

37 ChinaFile, ‘Document 9: A ChinaFile Translation’, bit.ly/3qKlH8t.

38 The Guardian, ‘China cuts ‘freedom of thought’ from top university charters’, bit.ly/3qkhNCb.

39 Elizabeth J. Perry, ‘Educated Acquiescence: How Academia Sustains Authoritarianism in China’, Theory and Society 49, no. 1 (2020), 15.

40 Cai Xia, ‘The Party That Failed’, Foreign Affairs, fam.ag/3t6npSo.

41 Beat Hotz-Hart, ‘Sorge um China-Strategie im Bereich Hochschulen’, NZZ, February 15, 2021.

42 BBC, ‘Hong Kong security law: What is it and is it worrying?’, bbc.in/3uv34Ye.

43 Patrick Wintour, ‘Academics warn of ‘chilling effect’ of Hong Kong security law’, The Guardian, bit.ly/2NrF4oB.

44 Reuters. 2021, ‘China hits back at EU with sanctions on 10 people, four entities over Xinjiang’, March 22, 2021. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://reut.rs/3dNSYuR.

45 Yojana Sharma, ‘China fights back with sanctions on academics, institute’, University World News, https://bit.ly/3E1vmyt.

46 Peter Mattis, ‘China’s ‘Three Warfares’ in Perspective’, War on the rocks, bit.ly/37H6D47.

47 Marshall Sahlins, ‘Confucius Institutes: Academic Malware and Cold Warfare’, Inside Higher Ed, July 26, 2018, bit.ly/30jmnWC.

48 Ryan Fedasiuk, ‘Putting Money in the Party’s Mouth: How China Mobilizes Funding for United Front Work’, bit.ly/3pVLFos.

49 Ralph Weber, Unified message, rhizomatic delivery: A preliminary analysis of PRC/CCP influence and the united front in Switzerland, bit.ly/2ZM5u6U.

50 Daniel Broessler, ‘China setzt Exil-Hongkonger in Deutschland unter Druck’, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, bit.ly/3up2wmS.

51 Javier C. Hernandez, ‘Professors, Beware. In China, Student Spies Might be Watching’, New York Times, nyti.ms/37DC3Z5.

52 Shui-Yin Sharon Yam, Fear in the Classroom, Made in China Journal, bit.ly/3usxBGk.

53 Vanessa Frangville, ‘La chronique de Carta Academica – «Liberté académique sous pression en Belgique: le long bras de Pékin»’, Le Soir, bit.ly/3kj1nZm.

54 Martin Thorley, ‘Huawei, the CSSA and beyond: “Latent networks” and Party influence within Chinese institutions’, The Asia Dialogue, bit.ly/3kkONsQ.

55 Ibid.

56 Clive Hamilton, Understanding China’s Threat to Australia’s National Security, bit.ly/3qWlgYY.

57 David Brophy, Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia by Clive Hamilton, Australian Book Review, bit.ly/3sqXbcK.

58 FragDenStaat, ‘Bereichsausnahmen’, bit.ly/3byrZlb.

59 OVG Nordrhein-Westfalen, ‘Urteil vom 18.08.2015 - 15 A 97/13’.

60 FragDenStaat, ‘Bereichsausnahmen’.

61 David Missal, Unpublished paper on PRC funding for German academia, Sinopsis.

62 Ibid.

63 German Rectors’ Conference, ‘Guiding questions on university cooperation with the People’s Republic of China’, September 9, 2020, bit.ly/2ZKPfab.

64 Around 80 out of the largest 100 German universities refuse to provide any information on their funding from the PRC (David Missal, Unpublished paper on PRC funding for German academia, Sinopsis).

65 NZZ Standpunkte, ‘Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer | China - Anatomie einer Weltmacht (NZZ Standpunkte 2017)’, bit.ly/3ealVT3 The exchange starts from 32:32.

66 University of Nottingham, ‘Civil society trust networks are being replaced by centralised and strictly controlled party-state power hierarchies’, bit.ly/3qKASyt.

67 Ian Johnson @iandenisjohnson, ‘A really excellent thread by Andreas Fulda on German Sinologists wanting to have it both ways--being experts at home and accepted in China. This theme is one familiar to many countries’, Tweet from February 17, 2021, bit.ly/3aKYfCp.

68 Marina Rudyak, ‘Keine Orchidee. Über Chinakompetenz und Sinologie’, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ), bit.ly/3bDKx3q.

69 A brief note about terminology. In the German-languagae academic and public discourse China experts are often referred to as ‘Sinologists’. This catch-all description is problematic since it does not distinguish between the more historically and linguistically oriented philological Sinologists (who primarily specialise in pre-modern China) and sociological China researchers in Germany (who primarily specialise in modern China after 1840). Yet both in the academic and the public discourse the terms ‘Sinologe’ and ‘sozialwissenschaftliche Chinaforscher’ (sociological China researcher) are often being used interchangeably. For the sake of greater consistency we have adopted the term ‘China scholars’. When alternative terms appear this is due to their use by quoted discourse participants.

70 Deutscher Bundestag, ‘Anhörung zur Lage der Menschenrechte in China’, November 19, 2020, YouTube, bit.ly/3ulY9ca.

71 Konfuzius-Institut an der Freien Universität Berlin, ‘News. Konfuzius-Institute in Deutschland – Positionspapier’, August 14, 2020, bit.ly/3pTpKxY.

72 Andreas Fulda, ‘Wissenschaftsautonomie wahren. China und die Wissenschaft in Großbritannien’, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ), bit.ly/2ZL1fs9.

73 Frank Furedi, What’s Happened to the University. A Sociological Exploration of its Infantilisation (Routledge: London and New York), 179.

74 Andreas Fulda, ‘China Is Merkel’s Biggest Failure in Office’, Foreign Policy, bit.ly/2P3fvKJ.

75 Marcus Colla, ‘‘Alternativlos’? The future of Angela Merkel’s chancellorship’, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, bit.ly/2ZKR8DN.

76 Global Times, China can gain final advantage by preventing a new Cold War, bit.ly/3qRzf1V.

77 Emily de La Bruyère and Nathan Picarsic, ‘Made in Germany, Co-opted by China’, Foundation for Defense of Democracies, bit.ly/37EOYKc.

78 Business Standard, ‘Covid-19 affect: European leader calls for reducing dependence on Chinese goods of critical importance’, bit.ly/2ZMcW1S.

79 Financial Times, ‘Why Ericsson took on its own government to defend rival Huawei’, on.ft.com/2P9JdOj.

80 Heike Schmoll, ‘Selbstzerstörung der Wissenschaft’, FAZ, November 4, 2019.

81 Sheena Chestnut Greitens and Rory Truex, ‘Repressive Experiences among China Scholars: New Evidence from Survey Data’, The China Quarterly (London) 242 (2020): 370.

82 Karl Kränzle, ‘Entpolitisierte Wissenschaft — verwissenschaftlichte Politik’. 607.

83 Kai Strittmatter, ‘Das Schweigen der Chinakenner’, Süddeutsche Zeitung, bit.ly/2O9h0H4.

84 Ibid.

85 Heiner Roetz, ‘Who Is Engaged in the “Complicity with Power”? On the Difficulties Sinology Has with Dissent and Transcendence’, in Transcendence, Immanence, and Intercultural Philosophy, ed. Nahum Brown and William Franke (Palgrave Macmillan), 307.

86 David Missal, Unpublished paper on PRC funding for German academia, Sinopsis.

87 Clive Hamilton and Mareike Ohlberg, Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World (Oneworld Publications).

88 Marina Rudyak 卢玛丽 @RudyakMarina, ‘Mühlhahns letztes Buch und seine anderen Forschingspublikationen nicht gelesen, oder? Twitter ist nicht das einzige Outlet, auf dem man sich äussern kann’, Tweet from June 17, 2020, bit.ly/2ZIbsWq.

89 For more information see Merics, https://merics.org/de/governance and GMFUS https://www.gmfus.org/our-partners.

90 Teng Biao, ‘Oppression, Resistance and High-Tech Totalitarianism’, Public Seminar, bit.ly/37IxRHD.

91 Ibid.

92 Solidarity statement on behalf of scholars sanctioned for their work on China. April 14, 2021. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://bit.ly/3jOaxPe.

93 Ed Lucas, ‘Our universities have sacrificed academic liberty for Chinese cash’, The Times, bit.ly/2ZKY3Nh.

94 Geremie R. Barmé, ‘On New Sinology’, A New Sinology Reader, The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology, bit.ly/3dI8ER6.

95 ASPI, ‘China’s Tech-Enhanced Authoritarianism’, bit.ly/2OWqR3m.

96 Foreign Affairs Committee, ‘Tuesday March 2, 2021’, bit.ly/38Cl5uB.

97 Cai Yongshun, ‘Grid Management and Social Control in China’, The Asia Dialogue, bit.ly/3ct2yBX.

98 Deutscher Bundestag, Drucksache 19/27109, bit.ly/3uOTJLd.

99 BMBF, ‘Projekte der BMBF-Fördermaßnahme “Ausbau der China-Kompetenz an deutschen Hochschulen”, bit.ly/3sL7850.

100 The Guardian, ‘The secrets of a peacemaker’, bit.ly/2NUPrkI.

101 Heiner Roetz, ‘Sinologie als Problem’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, April 27, 2011, bit.ly/3rs7rBE.

102 Human Rights Watch, ‘China: Government Threats to Academic Freedom Abroad’, https://bit.ly/2XgppNs.

103 DVCS, ‘Handlungsempfehlungen der Deutschen Vereinigung für Chinastudien e. V. zum Umgang deutscher akademischer Institutionen mit der Volksrepublik China’, December 29, 2018, https://bit.ly/3z7pkJa.

104 Didi Kirsten Tatlow, ‘How “Democratic Security” can protect Europe from a rising China’, DGAP Policy Brief, bit.ly/3khwnsK.