ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers in Aotearoa New Zealand to consider how effectively they promote Indigenous rights and the exercise of Māori law and relationships with place. We ask how these arrangements shape power relations and dynamics among different (human and non-human) actors and whether they foster relationality and create the enabling conditions that generate alternatives to modernist ways of governing. After examining the detail of these complex institutional arrangements in a way that exposes their ontological foundations, this paper argues that, despite limitations, particularly in relation to implementation, these arrangements operate to increase Iwi authority and, thus, promote Indigenous rights, and legal and ontological pluralism. This outcome demonstrates a vibrancy and plurality of thinking in relation to new models of law and institutional arrangements in settler-colonial contexts—beyond those grounded in rights of nature—and that there are a variety of pathways towards the realisation of Indigenous rights and authority, and the related promotion of legal and ontological pluralism.

Introduction

This paper analyses the legislative and institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers in Aotearoa New Zealand (‘Aotearoa’) to consider how effectively they promote Indigenous ontology, authority and rights, and provide for the exercise of Māori law and jurisdiction.

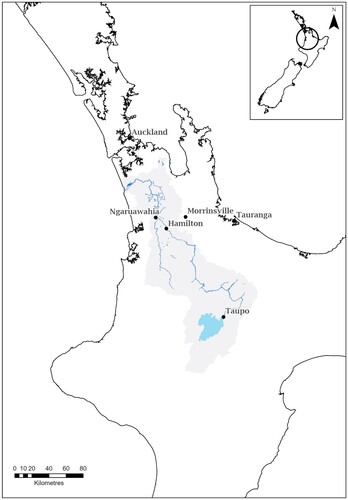

The Waikato River is the longest river in Aotearoa with a length of 425 km. The river flows from the slopes of Mt Ruapehu northwest to Port Waikato where it discharges into the Tasman Sea. The Waikato River flows through land that was once native cover, wetlands and peat bogs but is now dominated by pastoral agriculture along with human settlements.Footnote1 In 2010, the institutional arrangements governing the Waikato River (and the Waipā as the largest tributary) changed with the introduction of co-management and the establishment of the Waikato River Authority (‘WRA’)—providing the five River Iwi (tribes)Footnote2 who whakapapa (are connected by genealogy or descent)Footnote3 to the Rivers with enhanced opportunities to make decisions about the Rivers alongside local government actors.

This paper adopts an interdisciplinary approach, drawing from our disciplines in law and geography.Footnote4 In analysing the institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers (by which we mean ‘the set of working rules that are used to determine who is eligible to make decisions’ and the actions, procedures, and information sharing that is prescribed),Footnote5 we are concerned with understanding ‘how governance approaches are conceptualised, constituted, and enacted—the ontological dimensions of governance—and how this shapes power relations and dynamics among different (human and non-human) actors’.Footnote6 Drawing on Fisher et al.,Footnote7 we focus on the enabling conditions, or ‘pou’ (in te reo Māori, the Māori language) ‘that generate alternatives to modernist ways of governing and foster relationality’.Footnote8 We highlight the need to examine the detail of these often complex arrangements in a way that exposes the ontological foundations of environmental law and governance.

The focus here is on enabling conditions rather than outcomes in recognition of the fact that these institutional arrangements are relatively new. When compared against the timescale of the previous settler-colonial institutions in place for the Rivers, let alone against the pre-colonial institutions, we are evaluating a very short time period, and it is too soon to make an informed assessment of outcomes. Instead, we remain centrally focused on exploring how the institutional arrangements affirm Iwi authority and jurisdiction, including in relation to Crown authority (though not exclusively). We contend the recognition of Iwi authority and jurisdiction is an example of promoting the rights to self-determination and culture. Similarly, we examine how the inclusion of Indigenous language, values, principles, and ontologies pushes law to consider relationality, pluralism, and socionatural entanglements.

To undertake this institutional analysis, part one of the paper considers questions of ontology that must be examined when attempting to bridge the gap between settler-colonial and Māori approaches to environmental governance. We consider the significance of Indigenous ontology, authority, and rights within the legal institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, in contrast to the emphasis on Rights of Nature (RoN) that has been a feature of recent legal developments around environment governance.

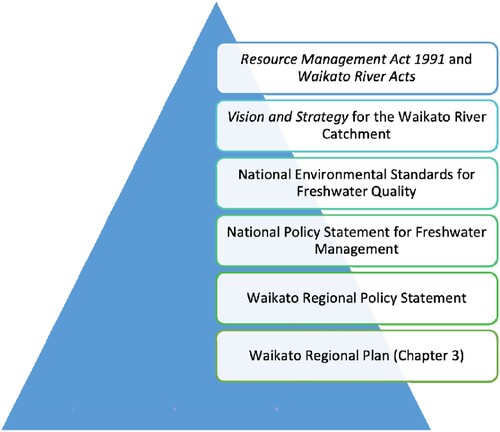

Part two of the paper moves to setting out the legal institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, starting with an overview of the Resource Management Act (‘RMA’) and the hierarchy of plans and policies under it. We highlight implementation challenges under these arrangements, and contrast these with reported developments under the Te Awa Tupua Act in relation to the Whanganui River.Footnote9

Finally, in part three of the paper, we argue that the new institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers can be understood as a model that foregrounds Indigenous ontology, authority, and relational rights, and allows for a new model of river governance to emerge. We contend, although they have clear limitations, the River arrangements allow for significant innovations—particularly by creating space for Iwi authority, Indigenous rights, and ontological shifts—that were not allowable before. This demonstrates a vibrancy and plurality of thinking in relation to new models of law in settler-colonial contexts, and that there are a variety of pathways towards the realisation of the rights to self-determination and culture, and towards legal and ontological pluralism.

Part 1: rights and ontology

Settler-colonial environmental law, and the institutions it establishes, are founded on a particular ontological (and epistemological) foundation that has been described as ‘Western’ and ‘modernist’. A central aspect of this foundation is its conception of the environment (or ‘Nature’). Boulot and Sterlin, for example, argue that this modernist ontology frames nature as ‘a resource empty of meaning and purpose and therefore available for human annexation’.Footnote10 This understanding of nature dovetails neatly with the project of modernity and with the colonial project, by operating to abstract nature, shearing it ‘from social context (both human and more-than)’ and rendering it ‘passive or non-agentic and therefore res nullius’, available for appropriation and extraction.Footnote11 The flip side of this dualist approach is the creation of ‘wilderness zones’ designated for conservation. Giacomini describes this as a colonial model of conservation, with an ‘underlying philosophy of uncontaminated nature’ in pursuit of selective environmental protection,Footnote12 and argues that, ‘despite the theoretically ‘noble’ end goal of protecting biodiversity and nature from human action, environmental conservation is rooted in colonial thought and colonial practices’, including the removal of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands.Footnote13

In contrast, Moreton-Robinson describes Indigenous ontologies or ‘ways of being Indigenous’ as being ‘inextricably connected to being in and of our lands’.Footnote14 She explains, ‘as humans we are the embodiment of our lands’.Footnote15 Mills argues that Indigenous ontology manifests in what he calls ‘rooted constitutionalism’, a form of constitutionalism best exemplified by Indigenous peoples, but ‘available to anyone willing to sustain it’.Footnote16 A core principle of rooted constitutionalism is reciprocity, described by Mills as ‘[m]utual aid, or wiisookodadiwin’.Footnote17

In the context of First Nations peoples in Australia, Graham articulates the reciprocal and relational connection between people and Country, and the role of living Country as the source of law, in the following way:

The great and venerable age of Aboriginal people also manifests itself in human beings patterning themselves into the Land via the Law. The result is that well-known phrase which is both a form of protest and a philosophical worldview: The Land is the law.Footnote18 This [Custodial] ethic, which grew out of the Land/Human relationship, … involves an obligation to look after the Land that nurtures us, the ancient reciprocal relationship with nature … Footnote19

It has been argued that the concept of different ‘worldviews’ implies that we are speaking about different perspectives on the same world, while the concept of ‘ontologies’ emphasises that what we are referring to are, in fact, different worlds.Footnote25 While we draw on this distinction by focusing primarily on questions of ontology, we also observe that it is not universally reflected in the literature (as demonstrated above) and the concept of ‘worldview’ is often used in place of both ontology and epistemology. The concept of Te Ao Māori, for example, is generally translated as ‘Māori worldview(s)’ and we have maintained this practice even where the meaning could also be described as ‘Māori world’ (or ontology).

Rights of nature

Returning to the dualistic ontology embedded within what Mills calls a one-world view, Berry characterises it as ‘radical discontinuity’Footnote26 and his early promotion of RoN is based on his belief that ‘the renewal of life on the planet must be based on the continuity between the human and the other than human as a single integral community’.Footnote27 This assertion that RoN is a key pathway to pursuing a more ecologically sustainable future is common amongst proponents of RoN or ‘earth jurisprudence’,Footnote28 and the adoption of RoN approaches in jurisprudence and legislation has been seen as evidence of a distinct ‘ontological turn’.

However, others have questioned whether RoN is an effective framework for moving beyond Western dualism. In his critique of the (global) RoN movement, Tănăsescu highlights the role of Berry’s ecotheological concept of ‘Nature [as a singular universal entity]’ in ‘perpetuat[ing] colonial relations aimed at cultural erasure’.Footnote29 He is particularly critical of the inherent lack of respect for place within such a universalist approach, and argues that ‘Nature is a concept that can only arise out of cultures seeking universality, and hence justifications for their right to rule over everything’.Footnote30

Here we argue that RoN does not inevitably result in such outcomes, and can be implemented in a way that is both sensitive to place, and to local Indigenous ontology, authority and rights.Footnote31 Indeed, in common with others, we argue that this is one of the key merits of the legal institutional arrangements put in place for the Whanganui River.Footnote32 Nonetheless, it is also apparent that RoN does not automatically lead to the legal ‘ontological turn’ necessary to foreground relationality or result in the adoption of legal institutional arrangements that recognise Indigenous law and jurisdiction.Footnote33 As such, this article explores an alternative approach to foregrounding relationality and Indigenous authority—one grounded instead in human rights. Our position is that focusing on people is not inherently anti-environmental, particularly when this focus is grounded in a reciprocal relationship to place.

Human rights

There are longstanding critiques levelled at rights, including the use of rights-frameworks for the recognition of Indigenous entitlements and legal and political authority. Burdon and Williams, for example, argue that ‘[l]egal rights are a liberal democratic construction that is predicated upon the abandonment of alternative political formations and more radical visions for the future’.Footnote34 Tănăsescu is similarly critical of rights discourses for supporting the expansion of capitalism and inequality, arguing that throughout the history of capitalism, ‘the power of nation state [has been used] to selectively apply rights in a way that matches with the interests of global capital expansion’.Footnote35

Scholars have warned that this risk of state capture or deradicalisation may be further exacerbated in the context of Indigenous relations with the settler-colonial legal system due to the added risk of what has been described as ‘ontological submission’.Footnote36 It is in this context, and bolstered by his concerns about incommensurability,Footnote37 that Mills has warned of the risk that Indigenous knowledge may be reconstituted ‘within the logic and structure of the constitutional order it’s translated into’Footnote38—a process he describes as ‘constitutional capture’ (‘meaning that attempts at legal pluralism may result in only further solidifying the dominant liberal legal order’).Footnote39

These critiques are, however, nuanced. Burdon and Williams, for example, emphasise that their critique is not a call to completely ‘abandon a liberal rights discourse’,Footnote40 since, ‘in the context of the impending environmental crisis … individuals and communities should have the liberty to deploy whatever discursive strategy or law is appropriate to attain even modest or perhaps temporary protection.’Footnote41 Instead, they offer their critique to support an ‘instrumental or political deployment of rights of nature’ (and, one assumes, rights more generally) that is strengthened through a better appreciation of its limits.Footnote42

Tănăsescu draws a clear distinction between the ‘dominant, orthodox view of the rights of nature’, and cases in Aotearoa New Zealand that are ‘markedly different’.Footnote43 He describes these latter examples as ‘legal compromise[s] reached through negotiation’ and ones that create space for innovation in governance arrangements,Footnote44 which enable Māori ‘to foreground the issues of ownership and authority’, along with ‘ontological mixing’.Footnote45 Boulot and Sterlin similarly argue that some rights of nature developments may represent ‘the radical leaking of Indigenous legal and, crucially, ontological orders into the legislation of the nation-state’.Footnote46 In this paper, we argue that certain human rights, such as the rights to self-determination and culture for Indigenous peoples—promoted through co-governance and co-management, and the recognition of relationality—offer a similar potential to foreground Indigenous authority and to promote pluralism and ontological mixing.

The right to self-determination is protected by article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and article 1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and includes the right of peoples (rather than individuals) to freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.Footnote47 Closely related is the right to culture, recognised in article 27 of the ICCPR.Footnote48 Under this right, the state is prohibited from denying individuals the right to enjoy their culture, and may be required to take positive steps to protect the identity of minority groups, particularly including Indigenous peoples, and the rights of members to enjoy and develop their culture.Footnote49

These rights have been further articulated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).Footnote50 While not legally binding, UNDRIP supports the interpretation of existing obligations of States Parties under binding international agreements, by providing ‘a contextualized elaboration of general human rights principles and rights as they relate to the specific historical, cultural and social circumstances of indigenous peoples’.Footnote51

In relation to the right to self-determination, UNDRIP emphasises the requirement for Indigenous peoples’ ‘free, prior and informed consent’ in relation to decisions that may affect them,Footnote52 and (relevant to this paper) for ‘any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources’.Footnote53 The right to self-determination means that settler-colonial states have an obligation under customary international law to consult with Indigenous peoples in relation to actions which may affect them.Footnote54 The UN Human Rights Council has clarified that consultation requires ‘a process of dialogue and negotiation over the course of a project, from planning to implementation and follow-up’,Footnote55 which protects the right of Indigenous peoples to ‘influence the outcome of decision-making processes affecting them’.Footnote56

Åhrén goes further, arguing that ‘the core element of the internal aspect of the right to self-determination is not a right to participate in decision-making processes, but to effectively determine the material outcome of such’.Footnote57 This does not necessarily mean that Indigenous peoples should always have the final say in the event of a conflict of views. Instead, Åhrén suggests a ‘sliding scale’ under which Indigenous people have a greater influence over the final outcome in relation to issues that are particularly important ‘to the indigenous people’s culture, society, and way of life’.Footnote58 Åhrén further suggests that ‘indigenous peoples’ decision-making power must reasonably be relatively extensive’ in relation to their lands and waters, given ‘that indigenous peoples’ societies, cultures, and ways of life are intrinsically rooted in lands and natural resources traditionally used’.Footnote59

Similarly to the right to self-determination, the obligations imposed under the right to culture are expanded upon in articles 25 and 31 of UNDRIP and include the obligation to protect and respect the right for Indigenous people to ‘maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their [traditional lands and waters] … and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard.’Footnote60

Ontologies of governance

So how can Indigenous rights and ontologies be enabled in legal governance arrangements for rivers? In a recent paper on broadening environmental governance ontologies to enhance ecosystem-based management in Aotearoa, Fisher et al. propose four pou (or enabling conditions) that generate alternatives to governance models underpinned by a ‘modernist’ (dualistic, technocratic) ontology: (i) enacting interactive administrative arrangements; (ii) diversifying knowledge production; (iii) prioritising equity, justice, and social difference; and (iv) recognising interconnections and interconnectedness.Footnote61 Below, we explore how the institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers provide opportunities for interaction, diversified knowledge production, equity, and interconnection through the recognition of relationality, or what we describe as ‘relational rights’ ().

Part 2: the legal governance arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers

Water governance in Aotearoa

Aotearoa is a constitutional monarchy, having been colonised by the British in the nineteenth century. Its founding constitutional document, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, was signed in 1840 between rangatira (chiefs) and the British Crown, alongside the English text—the Treaty of Waitangi. Crown breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi have led Māori to seek the return of land, water and other resources, the protection of natural environment, recognition and restoration of language and culture, equitable access to government resources and recognition of Māori sovereignty.Footnote62 In 1975, the Treaty of Waitangi Act was passed, establishing the Waitangi Tribunal, a standing Commission of Inquiry, to investigate Māori claims of Treaty breaches by the Crown.Footnote63 The negotiation of a claim culminates in Treaty Settlement, which signals the resolution of historical grievances between a Māori claimant group and the Crown.

Although, prior to colonisation, Māori exercised rights and authority over all waters in Aotearoa, upon colonisation the British Crown (unilaterally and without consultation or compensation) vested the right to use and manage water in itself.Footnote64 The Resource Management Act 1991 (NZ) (‘RMA’) is the primary legislation for environmental governance in Aotearoa, directed to support the ‘sustainable management’ of natural and physical resources through an integrated management approach.Footnote65 The RMA established an effects-based planning system with a hierarchy of standards, policy statements and plans to guide local government authorities (which comprises unitary authorities along with city, district and regional councils) in their decision making.Footnote66 Responsibility for managing water resources and controlling activities that could affect water bodies (including ecosystems) falls to regional councils.Footnote67 Regional councils are required to establish, implement and review objectives, policies and methods that achieve integrated management of natural and physical resources within their region.Footnote68

The RMA has enabled greater public participation in decision-making processes than previous legislation;Footnote69 however, it is still widely considered to inadequately reflect Māori rights and interests.Footnote70 The RMA includes specific provisions related to Māori in achieving the purpose of the Act whereby all persons exercising functions and powers under it: shall ‘recognise and provide for’ the relationship of Māori and their culture and traditions with their ancestral lands, water, sites, waahi tapu (sacred sites), and other taonga (treasures);Footnote71 ‘have particular regard’ to kaitiakitanga (which is often narrowly translated to equate to a Western concept of guardianship, stewardship or custodianship, but has a more expansive definition in tikanga Māori that encompasses reciprocal obligations and rights/authority, and the kinship system within which they exist);Footnote72 and ‘take into account’ the principles of the Treaty.Footnote73 The RMA also provides for collaborative governance arrangements including joint management agreements,Footnote74 transfers of RMA powers and functions,Footnote75 mana whakahono ā rohe agreements (Iwi participation arrangements),Footnote76 and water conservation orders.Footnote77

Water governance in Aotearoa is also directed by the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 (‘NPS-FM’).Footnote78 The NPS-FM directs regional councils to set objectives for freshwater management within their region. It also requires regional councils to make or change regional plans consistent with its policies ‘as soon as is reasonably practicable’,Footnote79 including managing water in a way that ‘gives effect’ to Te Mana o Te Wai—a hierarchy of obligations now applying to all aspects of freshwater management (as a ‘fundamental concept’) that prioritises the health and well-being of water bodies and freshwater ecosystems ahead of economic, social or cultural needs. To achieve this, regional councils are required to work with tangata whenua (Māori, ‘people of the land’) in water planning.Footnote80 The NPS-FM includes a number of specific policies around involving tangata whenua in freshwater management, as well as policies about integrated catchment management, protection of outstanding water features and habitats for indigenous species, water quality, and efficient water allocation.Footnote81

Water governance for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers

The Waikato Regional Council (WRC) is responsible under the RMA for managing the Waikato and Waipā Rivers and for water management more generally in the Waikato Region. WRC has prepared both statutory and non-statutory planning and policy documents to support it in achieving the purpose of the RMA. Since 2010, governance and management of the Waikato and Waipā Rivers has grown more complicated as a result of legislation arising out of Te Tiriti o Waitangi settlements between five River Iwi and the Crown.Footnote82 The Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act 2010, Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act 2010 and Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act 2010 (‘Waikato River Acts’), provide specific policy direction to central and local government, to ‘protect the health and wellbeing of the Waikato River for future generations’, as part of a co-management arrangement for the Waikato River (see ).

The Waikato River Authority (WRA) was established in 2010 and formally recognised as the co-governance entity for the Waikato River. The WRA has representation from the Crown and River Iwi—Waikato-Tainui, Ngāti Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, Te Arawa, and Ngāti Maniapoto.Footnote83 WRA are the sole trustees of the Waikato River Clean-up Trust (WRCuT) and oversee Te Ture Whaimana o Te Awa o Waikato/Vision and Strategy (‘V&S’) for the Waikato River, which applies to 11,000 km2 of the Waikato catchment including the length of the Waipā River.Footnote84 Roles and responsibilities that fall to the WRA include to:Footnote85

prepare, review and promote the implementation of the V&S;Footnote86

request Ministerial call-ins under the RMA; and

facilitate Iwi membership in resource consent hearings.Footnote87

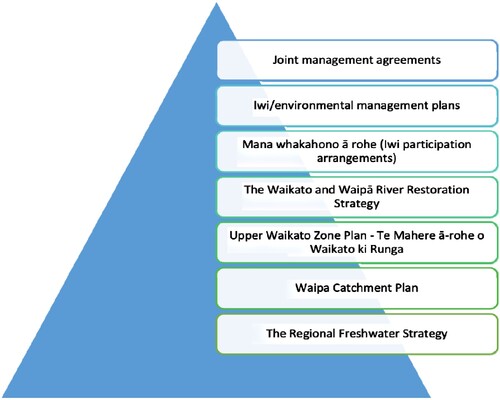

In 2012 the co-governance framework was extended to include the Waipā River through separate legislation establishing co-governance and co-management. The Waipa River Act distinguishes co-governance from co-management whereby ‘co-governance’ refers to the relationship (and institutional arrangements) between the Waikato and Waipā Rivers and their Iwi (while acknowledging the multifaceted relationship between Ngāti Maniapoto and the Waipā River).Footnote88 provides a high-level summary of the co-governance framework that applies to both the Waikato and Waipā Rivers.Footnote89

Table 1. Co-governance framework for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers.

The Waikato River Acts provide for the V&S as the primary policy direction for the management of the Waikato River.Footnote90 The legislation forms part of, and prevails over, the Waikato Regional Policy Statement and over any national policy statements or national environmental standards with respect to the management of the Waikato River and its tributaries.Footnote91 The V&S includes a number of objectives and strategies for the management of the Waikato River, which include protecting the health and well-being of the river through use of mātauranga (broadly understood as Māori knowledge), integrated and holistic management, the precautionary approach and management of cumulative effects, and recognition and protection of Iwi relationships.

The importance of river restoration in achieving the objectives set out in the V&S is reflected in efforts by WRA to allocate WRCuT funding to support physical (and cultural) enhancement. The first round of funding was awarded in 2011. By 2014, the WRA, River Iwi and key stakeholders had identified the need for a more strategic approach to ensure restoration activities would successfully deliver on the V&S. This led to the establishment of the Waikato River Restoration Forum, comprised of representatives from the five River Iwi, the Waikato River Authority, Waikato Regional Council, DairyNZ, Fonterra, territorial local authorities, Mercury, Genesis Energy, and the Department of Conservation, with a purpose of ‘maximising opportunities to realise the Vision & Strategy for the Waikato River catchment’.Footnote92 This group facilitated the development of the Waikato and Waipā River Restoration Strategy, which is a non-regulatory non-binding strategic plan for river restoration to ensure a more integrated and coordinated approach to funding and management. The plan guides organisations undertaking restoration activities and identifies projects likely to make the greatest difference in improving the condition of the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, and which reflect ‘the values and goals of the iwi and communities within the catchment’.Footnote93 The approach adopted to develop the Restoration Strategy reflects an attempt by WRA to ‘attend to different knowledges, values, interests and perspectives’ in achieving the V&S and aspirations for River Iwi.Footnote94

The Waikato River Acts necessitated changes by WRC in terms of its approach to managing the Rivers. This was accomplished through changes to policies, plans, and agreements enabled under the RMA but revised to reflect WRC responsibilities to River Iwi in exercising their authority.

The Waikato Regional Policy Statement: Te Tauākī Kaupapahere Te-Rohe O Waikato (‘WRPS’) sets out the resource management issues and objectives within the Waikato region.Footnote95 These include the V&S and other policies related to integrated catchment management,Footnote96 collaboration with tangata whenua, and maintaining the mauri (vital essence or life force) and values of freshwater bodies.Footnote97 The requirements of the NPS-FM concerning Te Mana o Te Wai and tangata whenua participation are likely to be consistent with (and already broadly satisfied by) the arrangements set up as part of the V&S, but in the event of any inconsistency, the V&S would prevail.

The Waikato Regional Plan (WRP), developed in 2007, is a resource-based plan that covers matters of importance to environmental management, matters of significance to Māori in the region, water, river and lake beds, land and soil, air, and geothermal resources.Footnote98 In 2014, WRC pursued a Regional Plan change to give effect to the V&S in the form of a chapter specifically focused on the Waikato and Waipā River catchments. Referred to as Healthy Rivers/Wai Ora Proposed Waikato Regional Plan Change 1, the community-based collaborative process sought to make recommendations to enable the restoration and protection of the health and wellbeing of the Rivers. The focus was diffuse pollution, with specific reference to the management of four contaminants—Escherichia coli (E. coli), nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment—those things ‘scientifically’ identified by Council as causing the most harm. In taking a limits-based approach to these contaminants, the scope of the plan change was narrower than what is possible under the V&S and what was pursued elsewhere (for example, the Waikato and Waipā River Restoration Strategy, which included cultural restoration initiatives).

There are other smaller-scale and non-statutory institutional arrangements, which may be made under several of these high-level laws and policies, including those listed in the image below in :

For Iwi, each of the Waikato River Acts have provisions for iwi management plans to be prepared and for joint management agreements between River Iwi and local government authorities.Footnote99 Both iwi management plans and joint management agreements are also mechanisms under the RMA.Footnote100 Iwi environmental management plans are non-statutory planning documents that may be prepared by an Iwi or Hapū (subtribe). These plans privilege Te Ao Māori (Māori worldviews—or what we might call ontologies and epistemologies) and allow for the articulation of Māori aspirations and values specific to Iwi/Hapū and their rohe (tribal area) while also providing a means by which to express grievance and loss (especially historic loss). Local authorities are required to keep iwi management plans created by recognised Iwi authorities.Footnote101 They must be taken into account when preparing or changing regional policy statements and regional and district plans,Footnote102 and the WRC must ‘have regard to’ them in resource consent decisions.Footnote103

Joint management agreements for each of the Iwi operate within existing statutory frameworks. These agreements provide an opportunity for River Iwi to work with local authorities on matters relating to the Waikato and Waipā Rivers in a manner consistent with the overarching purposes of the Waikato River Acts, and guiding principles articulated by each Iwi. For the acts relating to the Waikato River, this includes respecting mana whakahaere (authority and jurisdiction) rights and responsibilities of each of the Iwi in relation to the river.Footnote104 For the Waipā River, this includes respecting the mana of Ngāti Maniapoto in caring for and protecting the mana tuku iho o WaiwaiaFootnote105 for present and future generations.Footnote106

The co-management arrangements enabled through the Waikato River Acts provide a place-based extension of existing provisions in the RMA by reflecting Iwi law and ontology and providing specific mechanisms for the exercise of Iwi authority (see ). Importantly, the values and principles underpinning co-management, summarised below, are unique to each River Iwi and reflect the specific relationship between each Iwi and the Rivers. This is evident in the use of different terminology and prioritisation of distinct concepts and principles within each of the Acts as determined and negotiated by each Iwi. This gives rise to a complicated set of tools to guide co-management constituted by three separate yet connected pieces of legislation that aim to protect the authority of five distinct Iwi. The arrangements encompassed by the Waikato River Acts represent an institutional formalisation of relationships (between humans, and with more-than-humans) that pre-dates European colonisation and which maintains the mana of all involved.

Table 2. Summary of co-management arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā River.

Enacting institutional change

The establishment of the co-governance framework for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, and the formalisation of co-management mechanisms, has improved the ability for Iwi to assert their authority and culture in relation to caring for and protecting both Rivers. The institutional complexity of these arrangements does, however, present challenges for the WRA, individual Iwi, WRC and other local authorities with responsibilities in relation to one or both of the Rivers. Some of the key challenges reflect ontological differences—including governance models, conceptions of the relationship between people and nature, and of what restoration entails—as well as practical challenges associated with degradation, pressures on the Rivers, resourcing and capacity. Some of these challenges have been documented in formal evaluations, although a comprehensive review has yet to be completed.

By 2017, and in accordance with the deeds of settlement, an evaluation of the effectiveness of the co-governance and co-management arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers was conducted, which considered the perspectives of River Iwi, the Crown and central government agencies, local government, and the WRA. The review comprised a collaborative review between the Crown and River Iwi (which commenced in 2016), mana whakahaere reports prepared by each of the River Iwi, and independent consultant reports.Footnote107 The reviews considered the effectiveness of the deeds in relation to co-governance and co-management for each Iwi, the legislation for each Iwi, the WRA (the co-governance entity), the WRCuT, and V&S. Review reports acknowledged differences in terms of the implementation of co-governance and co-management mechanisms. For instance, by 2017, the WRA had been operational for over five years, and good progress had been made in establishing joint management agreements and preparing accords. Conversely, other mechanisms were either newly implemented or yet to be implemented (such as integrated management plans and the ability to make specific regulations) and were, therefore, too nascent to assess.Footnote108

The reports identified a number of ongoing challenges to implementation, including pressures on the Waikato and Waipā Rivers arising from competing uses in the catchment, as well as the need for capability building and awareness raising among local and central government authorities.Footnote109 The WRA was generally considered to be working well in giving effect to the V&S, although there were some suggestions that the WRA could take a greater leadership role in advocating for the Waikato River and in direct decision-making (for example, in relation to resource consent applications).Footnote110 The level of degradation in both the Waikato and Waipā Rivers means it may take some time to see significant improvements in river condition and water quality associated with restoration efforts.

Research by Muru-Lanning and Parsons et al. touches upon the challenges in implementing co-governance and co-management over the Waikato River given the reliance on a governance model that reflects a Western model rather than a Māori or hybrid model of governance.Footnote111 Similarly, Parsons et al. draw attention to some of the criticisms levelled at co-governance and co-management of the Waipā River by Iwi and Hapū members operating at the ‘flax-roots’ (on-the-ground) as kaitiaki (guardian) and in restoration, and who are not involved in higher-order decision-making or who have not benefited directly from WRCuT funds.Footnote112 A comprehensive review of the V&S is expected to be completed in 2025; it was last reviewed in 2011 (prior to the inclusion of the Waipā River), with no amendments made. The current review is, therefore, the first major review of the V&S since it was established.Footnote113

The Waikato and Waipā Restoration Strategy was developed in response to concerns over the limits of an ad hoc and annualised approach to funding priorities, but the Restoration Strategy, and the process undertaken to produce it, was not wholly without criticism.Footnote114 Paterson-Shallard et al. report some of the limitations identified by Māori regarding different conceptions of the relationship between people and nature and what restoration entails, discomfort over prioritisation based on a cost-benefit analysis approach, and a desire for greater use of mātauranga into specific restoration projects. These limitations reflect some of the challenges associated with ontological and epistemological differences, but also more practical challenges associated with resourcing and capacity.

In the case of individual Iwi, managing multiple relationships, preparing new (or revising existing) Iwi management plans, negotiating accords and joint management agreements, and designing and implementing restoration projects present enormous challenges. Although funding to support certain activities has been made available since the passing of the Acts, this does not necessarily address capacity issues (especially in the short-term). Notably, developing capacity among Iwi to ensure ongoing care and protection of the Rivers is a feature of the Waikato River Acts, and reflects an increasingly recognised need for capability building and succession planning within Iwi authorities.Footnote115 Additionally, while River Iwi representatives (and staff) come together and learn from each other in navigating co-governance and co-management (as the Restoration Strategy demonstrates), the focus of each of the River Iwi is to achieve the purpose of their respective Acts (which, as discussed above, differ).

The WRC and local authorities also have capacity issues, particularly in terms of dealing with ontological and epistemological differences, but also in terms of practical experience in working with Māori. Part of the challenge for local authorities, and especially WRC, is the fact that Crown responsibilities have seemingly been (unofficially) delegated to them by virtue of the scope of their functions under the RMA and the place-based nature of Treaty settlements. Rather than allowing the Crown to abdicate its responsibilities to Iwi, local authorities need to consider how their role as a Treaty partner fits into wider responsibilities and obligations. For instance, local authorities have been given increased responsibilities by way of Iwi management plans and joint management agreements. While these provide opportunities for more grassroots participation and inclusion and could support the possibility for greater collaboration between regional councils and Iwi/Hapū groups, these opportunities are not always realised due to a lack of capacity.

Challenges arising from epistemological and ontological differences also manifest in how co-governance is conceptualised and operationalised. Specifically, the structure of the WRA has been criticised as ‘an inherently western model with appointed representatives making formal statutory decisions on behalf of the various groups’ and providing a ‘model or way of viewing the river which is foreign to most Māori and one in which they cannot easily participate’.Footnote116 Similarly, the plan change to give effect to the V&S (Healthy Rivers/Wai Ora Proposed Waikato Regional Plan Change 1, discussed above) reverted to a technomanagerial approach to water management focused on establishing limits on contaminants and putting rules in place to manage effects. Meanwhile, the V&S provides opportunities for utilising mātauranga, for attending to social, cultural and spiritual values, and for protecting and enhancing relationships between people and the Rivers, among other things, that were not taken as part of the plan change. While it could be argued that a plan change is not the place for seeking to achieve values-driven objectives, especially given the duties and functions of regional councils, questions arise as to who is responsible for realising these objectives within a co-governance/co-management context.

The complex interplay of legislation, strategic plans and other institutional arrangements determines who is eligible to make decisions in relation to the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, and what kinds of actions, procedures and information sharing is prescribed as part of the process. These working rules shape the power relations around the river and relationships dynamics between human and non-human actors—including the river itself, which may, ‘generate alternatives to modernist ways of governing and foster relationality’.Footnote117

Part 3: discussion and evaluation

In our analysis of the legal institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, we have emphasised those aspects that create space for the exercise of Māori authority and jurisdiction.

Ontology and authority

A key component of Waikato and Waipā River arrangements is the recognition of an ontology and epistemology of human enmeshment with the rest of the natural environment—particularly with local lands and waters.Footnote118 This recognition is also key to creating space and legal hooks for the exercise of Iwi authority and jurisdiction in relation to the Rivers, even if the potential is not yet always realised. When examining the institutional arrangements, we argue that epistemological and ontological inclusion is facilitated by the recognition of mātauranga in the text of the resulting policies,Footnote119 in particular the V&S. Similarly, Iwi management plans enable the recognition of values and principles that reflect Iwi relationships with the Rivers (see above).

Inclusion of River Iwi mātauranga is provided for in a way that allows for the diversity of ontological perspectives of the five River Iwi. The legislation, for example, reflects different tikanga and kawa (Māori law and custom) as well as mana (prestige, power and authority) of Iwi over their respective Rivers. While the Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act recognises the River as an ancestor (or tupuna), the Tuwharetoa, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Arawa River Iwi Act and the Waipā River Act do not. Instead, the Tuwharetoa, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Arawa River Iwi Act emphasises mana whakahaere rights and responsibilities in relation to the Waikato River. The Waipā River Act recognises the care and protection of the mana tuku iho o Waiwaia or the ancestral authority and prestige handed down from generation to generation in respect of Waiwaia, a taniwha (supernatural creature) and kaitiaki (guardian) of the Waipā River and its people. This further highlights the inherent link between ontological inclusion and Iwi authority.

As noted above, the establishment of the WRA, with responsibilities in relation to the V&S and the WRCuT, ensures River Iwi (and their rights and interests) are represented as decision-makers alongside the Crown. The inclusion of the V&S in the WRPS, and the Regional Plan change, also foregrounds the importance of protecting and restoring the Rivers from a biophysical perspective, as well as acknowledging ‘the relationships of Waikato River iwi according to their tikanga and kawa with the Waikato River, including their economic, social, cultural, and spiritual relationships’.Footnote120 In addition to the political significance of recognising the need to ‘restore and protect’ Iwi relationships to and with the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, this ontological broadening of what environmental governance encompasses better reflects relational ways of knowing, being and doing that characterise many Indigenous ontologies.Footnote121 The commitment to the social, cultural, and spiritual relationships that entangle people and rivers is further evident in the approach to funding projects as part of the WRCuT. Specifically, the Waikato and Waipā River Restoration Strategy, which prioritises restoration and includes Iwi priority projects, guides the WRA in making funding decisions through the WRCuT,Footnote122 which has resulted in projects that support strengthening connections between River Iwi and their Awa (river) in addition to projects focused on riparian planting, ecological restoration and sediment controls.

In addition to the overarching co-governance framework, co-management mechanisms within each of the Acts provide further opportunities for Iwi to assert their authority (and cultural rights). For instance, the Kiingitanga Accord, the collateral Deed between the Crown and Waikato-Tainui dated 22 August 2008, describes a set of principles that underpin the new regime established through the Treaty settlement. These principles emphasise the ongoing authority, rights, and responsibilities of Waikato-Tainui in respect of the Waikato River (as reflected, for example, in te mana o te awa and mana whakahaere, and the practice of tikanga). They also set out the commitment by the Crown and Waikato-Tainui to good faith engagement and consensus decision-making and the significance of Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi to the relationships arising through the new institutional arrangements. Similarly, the Waiwaia Accord, a Deed between the Crown and Ngāti Maniapoto,Footnote123 affirms the commitment between the Crown and Ngāti Maniapoto in respect of the co-governance and co-management arrangements for the Waipā River. The Accord also recognises the special relationships between Ngāti Maniapoto and the Waipā River along with their ongoing responsibilities to care for the Waipā River and the mana tuku iho o Waiwaia. For both the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, these accords set the basis for how the Crown and Iwi ought to relate to each other as they engage in the care and protection of both rivers and affirm and recognise the cultural authority and rights of the Iwi.

There are, however, limitations to this largely paper-based recognition (of both ontology and authority), as there are few enforcement mechanisms and recognition does not always fully translate to the (largely settler-colonial dominated) implementation stage of the policy cycle—as we saw with the WRC’s plan change. Similarly, many of the policy documents (and legal instruments) recognise relationality, but translating this into the implementation stage remains an issue. Often, the implementation of values-based commitments is reduced to project-based funding, mostly for restoration activities, rather than transformative changes to ways of doing business. Restoration is beneficial and important, and the funding often provides important opportunities to practise culture, but this appears to fall short of self-determination or enabling the exercise of authority. As the River returns to health, what will be the next steps to return Iwi authority and power?

Rights and risks

In foregrounding Iwi ontology and authority, the legal institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers promote human rights—the rights to self-determination and culture—and provide a model for how these can be realised in a manner that is both place-based and relevant to Indigenous peoples. Rights themselves are not as important as what they can enable, but one of the key impacts of colonisation has been the stripping away of rights. In the context of the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, rights facilitate the exercise of Māori law and authority (self-determination) and relationships, including with the Rivers (culture), and this creates space for an understanding of governance and authority that emphasises relationality and place-based Māori law, knowledge and values. Although recognition in settler-colonial law is not required for any of this—these laws and relationships pre-exist colonisation and have continued to be exercised throughout the colonial period—the power of the settler-colonial state cannot be ignored.

The legislation that formalises co-governance and co-management of the Waikato and Waipā Rivers makes it clear that, from the perspective of River Iwi, their cultural rights and jurisdiction over the Rivers are undeniable. For example, for Waikato-Tainui, the purpose of the Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act includes recognising the significance of the Waikato River to Waikato-Tainui along with certain customary activities of Waikato-Tainui.Footnote124 Part 2 of the Waikato River Act, ‘Settlement redress through legislation’, provides an account of the significance of the Waikato River to Waikato-Tainui, where the river is identified as a tupuna (ancestor) and the relationship with the Waikato River:

… gives rise to our [Waikato-Tainui] responsibilities to protect mana o te Awa and to exercise our mana whakahaere in accordance with long established tikanga to ensure the wellbeing of the river. Our relationship with the river and our respect for it lies at the heart of our spiritual and physical wellbeing, and our tribal identity and culture.Footnote125

It is the values-based principles of interpretation woven through each legal instrument that operate to recognise and promote Iwi rights to self-determination and culture in relation to the Rivers. In acknowledging some of the challenges to delivering on the potentially transformative aspects of legal institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers, we highlight evidence that this epistemological and ontological inclusion, and increasing recognition of Iwi authority, has a clear influence on programmes of work and drives best practice in the catchments. Despite not usually being considered the Treaty partner for the Iwi (the Treaty partner is the Crown), the WRC have started to behave more like the Treaty partner, due to their relationships with the community and their regulatory responsibilities.

From rights to relationality

By emphasising reciprocity and relationality, the values and principles accompanying the arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers have the potential to guide implementation in a manner that enhances the mana of each River and its people, and to emphasise the inseparable relationship between Iwi and the Rivers, for a wide set of values from environmental protection to extractive use, under the authority, mana whakahaere and rangatiratanga of the River Iwi. In this way, environmental protection is understood through the lens of a two-way reciprocal relationship in contrast to ‘wilderness’ or ‘fortress conservation’ approaches that cordon off ‘nature’ as something that needs to be protected from people to off-set the extractive exploitation of everywhere else.Footnote130

One of the strengths of a human rights-based approach to environmental governance (rooted in the rights to self-determination and culture) is that it provides an opportunity to centre the relational connection between Indigenous peoples and Rivers. This reduces the risk of environmental colonialism—under which Indigenous peoples are separated from their lands and waters in the name of environmental protection. In this context, Salomon argues that culture facilitates the promotion and protection of alternative forms of economic organisation.Footnote131 Here it can be understood that Indigenous land and water management (and relationships) are ‘expressions of identity and culture, protected characteristics under international human rights law’.Footnote132

The rights to self-determination and culture also entail the necessary recognition of the value of diverse systems of knowledge beyond Western law and science.Footnote133 Giacomini emphasises that, ‘Indigenous knowledge is locally situated, and it can be maintained, transmitted and applied only if its holders are granted access to their traditional territories and lands where such knowledge originated and to which it is deeply tied.’Footnote134 Giacomini proposes that a ‘human rights-based conservation should be at the centre of environmental policies at the local level, in order to avoid the perpetration of a colonial model of evictions from natural areas of strategic importance to a State’.Footnote135

The institutional arrangements for another river in Aotearoa, the Whanganui, are often put forward as a gold standard for relational river governance. As Cribb et al. have highlighted in this Special Issue,Footnote136 interactive administrative arrangements for the Whanganui River under the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement Act) 2017 have enabled an Iwi-led Indigenous approach to environmental management. Similarly to the Waikato River Acts, the Whanganui legislation recognises the status of the River (and its tributaries) as ‘an indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and meta-physical elements’.Footnote137 Iwi law and values, or Tupua Te Kawa,Footnote138 have also been embedded in the river governance framework, or Te Pā Auroa,Footnote139 which comprises a range of legal entities involving Iwi, Hapū, government and community and recreational interests.Footnote140

A key difference between the Waikato River Acts and the Te Awa Tupua Act is that the Whanganui River has been recognised as a ‘legal person’,Footnote141 with corresponding rights, powers, duties, and liabilities.Footnote142 It is this specific legal innovation that has attracted international attention,Footnote143 but many scholars (particularly those with a closer connection to Aotearoa) argue this is far from the most significant aspect of the new legal institutional arrangements.Footnote144 Macpherson, for example, argues that ‘the Pā Auroa model set up in the legislation reflects significant foresight and provides for institutionality far beyond the legal fiction’.Footnote145 Similarly, Gilbert et al. and Tănăsescu emphasise the radical potential of the Te Awa Tupua Act lies in the space created for legal ontological pluralism, including relationality, and the increase in Iwi authority.Footnote146

Conclusions

Woven throughout the legal institutional arrangements for the Waikato and Waipā Rivers are interpretive principles that foreground Iwi ontology and authority. This can be understood as the promotion of human rights—namely the rights to self-determination and culture—in a manner that is both place-based and relevant to Indigenous peoples.

Given the global focus on RoN and legal personhood—often illustrated by the Te Awa Tupua Act—we suggest that more attention be paid to the vibrancy and plurality of thinking in relation to new models of river governance in settler-colonial contexts, especially the variety of pathways for realising the rights to self-determination and culture, and legal and ontological pluralism. These innovations offer potential pathways to destabilise the ontological foundations of the global environment crisis. A clear benefit of the (relational) human rights-based approach illustrated by the Waikato and Waipā River Acts is the foregrounding of a rooted, relational connection between people and place. Ontological mixing pushes back against environmental colonialistic approaches to the protection and management of rivers. While there are still challenges in implementation, due to limitations in capacity (for both Iwi and Crown agencies) and settler-colonial avoidance of enabling Indigenous authority and jurisdiction, our research points to the considerable institutional potential for ethical and just river futures.

Glossary

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr Karen Grant, Rachael Mortiaux and Leane Makey for their helpful research assistance and Miriama Cribb and Dr Julia Talbot-Jones for their kind and constructive guidance and feedback about this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cristy Clark

Dr Cristy Clark is a white-settler and an Associate Professor in Law at the University of Canberra, Australia. Her research focuses on the intersection of human rights and the environment – particularly on water and its intersections with relational rights, legal geography, and ecological jurisprudence. She is the co-author (with Dr John Page) of The Lawful Forest: A Critical History of Property, Protest and Spatial Justice (2022, Edinburgh University Press).

Karen Fisher

Dr Karen Fisher is Māori (Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato-Tainui) and Pākehā (a New Zealander of European-settler descent) and a Professor in Geography at the University of Auckland. Her research interests are in society-environment interactions, environmental governance and policy, and the politics of resource use. She is a co-author (with Dr Meg Parsons and Roa Crease) of Decolonising Blue Spaces in the Anthropocene: Freshwater management in Aotearoa New Zealand (2021, Palgrave Macmillan).

Elizabeth Macpherson

Dr Elizabeth Macpherson is Pākehā (A New Zealander of European-settler descent) and a Professor in Law and Rutherford Discovery Fellow at the University of Canterbury. Her research interests are in comparative environmental and natural resources law, human rights and Indigenous rights in Australasia and Latin America. She is the author of the award-winning book Indigenous Water Rights in Law and Regulation: Lessons from Comparative Experience (2019, Cambridge University Press).

Notes

1 Heather Paterson-Shallard et al., ‘Holistic Approaches to River Restoration in Aotearoa New Zealand’, Environmental Science & Policy 106 (2020): 250–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.12.013.

2 These River Iwi are Waikato-Tainui, Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, Te Arawa, and Ngati Maniapoto.

3 A glossary of te reo Māori (Māori language) terms is included at the end of the article.

4 The authors also acknowledge their diverse standpoints in coming to the research. We are based in Aotearoa New Zealand and Ngunnawal Country in Australia, and are Māori (Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato-Tainui) and non-Māori (Pākehā/white-settler).

5 Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 51, cited in Daniel H. Cole, ‘The Varieties of Comparative Institutional Analysis’, Articles by Maurer Faculty 2013, 834. (This paper does not include organisations within the definition of institutions.)

6 Fisher et al., ‘Broadening Environmental Governance Ontologies’, Maritime Studies 21 (2022): 610, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-022-00278-x.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid., 611.

9 Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act (NZ) 2017.

10 Emille Boulot and Joshua Sterlin, ‘Steps Towards a Legal Ontological Turn: Proposals for Law’s Place beyond the Human’, Transnational Environmental Law 11 (2022): 13, 14, https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102521000145.

11 Ibid.

12 Giada Giacomini, ‘Human Rights Violations in the Name of Environmental Protection: Reflections on the Reparations Owed to the Ogiek Indigenous People of Kenya’, Ordine Internazionale e Diritti Umani no. 3 (2023): 508–20, https://www.rivistaoidu.net/rivista-oidu-n-3-2023-15-luglio-2023/.

13 Ibid., 510.

14 Aileen Moreton-Robinson, ‘Incommensurable Sovereignties: Indigenous Ontology Matters’, in Routledge Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies, ed. Brendan Hokowhitu et al. (Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2022), 259.

15 Ibid., 259.

16 Aaron Mills, ‘A Preliminary Sketch of Anishinaabe (a Species of Rooted) Constitutionalism’, special issue, ‘Rooted Constitutionalism’, Rooted, 1, no. 1 (2021): 2–16, 3, https://indigenous-law-association-at-mcgill.com/rooted-publication/rooted-constitutionalism/.

17 Ibid., 4.

18 Chris Black, The Land Is the Source of the Law: A Dialogic Encounter with Indigenous Jurisprudence (New York: Routledge, 2010) cited in; Mary Graham, ‘The Law of Obligation, Aboriginal Ethics: Australia Becoming, Australia Dreaming’, Parrhesia 37 (2023): 1–21, 5.

19 Mary Graham, ‘The Law of Obligation, Aboriginal Ethics: Australia Becoming, Australia Dreaming’, Parrhesia 37 (2023): 1–21, 5, https://parrhesiajournal.org/past-issues/.

20 For a critical description of this process, see, e.g., Mihnea Tănăsescu, Understanding the Rights of Nature: A Critical Introduction, (Bielefeld: Verlag, 2022), https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839454312.

21 John Law, ‘What’s Wrong with a One-World World?’, Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 126 (2015), cited in Boulot and Sterlin, ‘Steps Towards a Legal Ontological Turn’, see note 10).

22 Emille Boulot and Joshua Sterlin (see note 10), 14–15.

23 Aaron Mills, ‘Miinigowiziwin: All That Has Been Given for Living Well Together: One Vision of Anishinaabe Constitutionalism’ (PhD thesis, University of Victoria, BC, Canada, 2019), http://hdl.handle.net/1828/10985 cited in Boulot and Sterlin, ‘Steps Towards a Legal Ontological Turn’ Transnational Environmental Law 11, no. 1 (2022): 16, https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102521000145.

24 Aileen Moreton-Robinson, ‘Incommensurable Sovereignties: Indigenous Ontology Matters’, in Routledge Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies, ed. Brendan Hokowhitu et al., (London: Routledge 2020), 19.

25 See, eg, Sarah Laborde and Sue Jackson, ‘Living Waters or Resource? Ontological Differences and the Governance of Waters and Rivers’, Local Environment 27 (2022): 357.

26 Thomas Berry, The Great Work: Our Way into the Future (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999), 80.

27 Ibid., 80.

28 For a critical discussion of the literature on this topic, see, for example, Mihnea Tănăsescu, Understanding the Rights of Nature (see note 20) chaps. 1–2; Peter Burdon and Claire Williams, ‘Rights of Nature: A Constructive Analysis’, in Research Handbook on Fundamental Concepts of Environmental Law, ed. Douglas Fisher (Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, USA: Elgar Online, 2016), 196 -2019, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784714659.00014.

29 Mihnea Tănăsescu, Understanding the Rights of Nature (see note 20), 63.

30 Ibid., 64.

31 Several examples of this place-sensitive approach can be observed in Aotearoa, in relation to the Whanganui River and the Te Urewera. See, eg, Mihnea Tănăsescu, Understanding the Rights of Nature, (see note 20), 69–82; Miriama Cribb, Jason P. Mika, and Sarah Leberman, ‘Te Pā Auroa Nā Te Awa Tupua: The New (but Old) Consciousness Needed to Implement Indigenous Frameworks in Non-Indigenous Organisations’, AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 18, no. 4 (2022): 566–75, https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801221123335; Miriama Cribb, Elizabeth Macpherson, and Axel Borchgrevink, ‘Beyond Legal Personhood for the Whanganui River: Collaboration and Pluralism in Implementing the Te Awa Tupua Act’, The International Journal of Human Rights (2024), https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2024.2314532.

32 Ibid.

33 For a detailed exploration of how Western law can become more relational and recognise Indigenous law and authority, and why this is so important, see Elizabeth Macpherson, ‘Can Western Water Law Become More “Relational”? A Survey of Comparative Laws Affecting Water across Australasia and the Americas,’ Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, (2022), 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2022.2143383.

34 Peter Burdon and Claire Williams, Rights of Nature: A Constructive Analysis (see note 28), 210.

35 Mihnea Tănăsescu, Understanding the Rights of Nature (see note 20), 11, 14. For an earlier critique of rights that informs that of Burdon and Williams (note 28), and Tănăsescu (note 20), see Costas Douzinas, Human Rights and Empire: The Political Philosophy of Cosmopolitanism (Abingdon: Routledge-Cavendish, 2007).

36 Anne Salmond, Tears of Rangi (Auckland University Press, 2017).

37 See Aaron Mills, ‘A Preliminary Sketch of Anishinaabe’, (see note 16); and Aaron Mills, Miinigowiziwin: All That Has Been Given for Living Well Together (see note 23), and related text.

38 Aaron Mills, Miinigowiziwin: All That Has Been Given for Living Well Together, (see note 23), 271.

39 Ibid, 16.

40 Peter Burdon and Claire Williams, Rights of Nature: A Constructive Analysis, (see note 28), 205.

41 Ibid., 205.

42 Ibid., 205.

43 Mihnea Tănăsescu, Understanding the Rights of Nature, (see note 20) 73.

44 Ibid., 80.

45 Ibid., 81.

46 Emille Boulot and Joshua Sterlin, Steps Towards a Legal Ontological Turn, (see note 10), 16.

47 The United Nations (UN) Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has stated that this includes ‘the rights of all peoples to pursue freely their economic, social and cultural development without outside interference’, General Recommendation 21 on the Right to Self-Determination (UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 1996).

48 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (n.d.), 27; United Nations Human Rights Committee, ‘CCPR General Comment No. 23: Article 27 (Rights of Minorities)’, (1994), para. 5.2.

49 United Nations Human Rights Committee, ‘CCPR General Comment No. 23: Article 27 (Rights of Minorities)’.

50 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007).

51 Ibid., art. 3.

52 Ibid., art. 19.

53 Ibid., art. 32(2).

54 International Labour Organization (ILO), Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, C169 (n.d.), 6; James Anaya, Indigenous Peoples in International Law, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 153–6.

55 United Nations Human Rights Council Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous People, ‘Free, prior and informed consent: a human rights-based approach: study of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’, 2018, A/HRC/39/62, paras. 15–16.

56 Ibid.

57 James Anaya, Indigenous Peoples in International Law, (see note 54), 138.

58 Ibid., 139.

59 Ibid., 140.

60 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples GA Res 61/295, art 25.

61 Fisher et al., Broadening Environmental Governance Ontologies (see note 6).

62 Margaret Mutu, ‘Behind the smoke and mirrors of the Treaty of Waitangi claims settlement process in New Zealand: no prospect for justice and reconciliation for Māori without constitutional transformation’, Journal of Global Ethics 14, no. 2, (2018): 208–21.

63 Waitangi Tribunal (2020), ‘Claims process’, https://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/claims-process/.

64 Elizabeth Macpherson, Indigenous Water Rights in Law and Regulation: Lessons from Comparative Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2018.1507003.

65 Resource Management Act 1991 (NZ), sec. 5.

66 Derek Nolan, Environmental and Resource Management Law, 6th ed. (LexisNexis, 2018), 588.

67 Resource Management Act 1991 (NZ), sec. 30.

68 Ibid.

69 Lloyd Burton and Chris Cocklin, ‘Water Resource Management and Environmental Policy Reform in New Zealand: Regionalism, Allocation, and Indigenous Relations’, Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy 7, no. 1 (1996): 75–106; Amanda Lowry and Rachel Simon-Kumar, ‘The Paradoxes of Māori-State Inclusion: The Case Study of the Ōhiwa Harbour Strategy’, Political Science 69, no. 3 (2017): 195–213, https://doi.org/10.1080/00323187.2017.1383855.

70 Elizabeth Macpherson, Indigenous Water Rights in Law and Regulation (see note 64).

71 Resource Management Act 1991 (NZ), sec. 6(e), sec 65.

72 Resource Management Act 1991 (NZ), sec. 7(a). See, e.g., Merata Kawharu, ‘Kaitiakitanga: A Maori Anthropological Perspective of the Maori Socio-Environmental Ethic of Resource Management’, Journal of the Polynesian Society 109, no. 4 (2000): 349–70.

73 Resource Management Act (NZ), sec. 8.

74 Ibid., sec. 36B.

75 Ibid., sec. 33. This power has only been exercised once to transfer powers to Māori—for the transfer of water monitoring functions to Tūwharetoa in 2021.

76 In 2017, the RMA was amended to enable Iwi and Hapū to enter into voluntary mana whakahono ā rohe agreements (secs. 58L–U), intended to increase Māori participation in collaborative governance of local resource management. In October 2020, the first mana whakahono ā rohe agreement was signed in New Zealand between Poutini Ngāi Tahu and the West Coast Regional Council.

77 Resource Management Act (NZ), sec. 199(2)(e); See the 2011 amendment to the water conservation order for Te Waihora, which recognises the significance of the lake to Ngāi Tahu: Environment Canterbury, Report of the Hearing Committee on an Application to Vary a National Water Conservation Order for Lake Ellesmere/Te Waihora in Canterbury, 2011.

78 New Zealand Government, ‘National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020’, 2020, <https://www.mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/Fresh%20water/national-policy-statement-for-freshwater-management-2020.pdf>.

79 Ibid., pt. 4.1.

80 Ibid., pt. 1.3(2).

81 Ibid., pt. 2.2, 3.4, 3.5.

82 Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act (NZ).

83 Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act (NZ); Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act (NZ) schedule 2 contains the Waikato River Authority, ‘Vision and Strategy for the Waikato River Te Ture Whaimana’, 2008, http://versite.co.nz/~2013/16230/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#1.

84 Karen Fisher and Meg Parsons, ‘River Co-Governance and Co-Management in Aotearoa New Zealand: Enabling Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being’, Transnational Environmental Law 9, no. 3 (2020): 455–80, https://doi.org/10.1017/S204710252000028X.

85 Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act (NZ), sec. 23.

86 Ibid., sec. 24.

87 Ibid., secs. 27–32.

88 Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act (NZ), sec. 7.

89 Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act (NZ).

90 Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act (NZ); Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act (NZ), Sch. 2.

91 Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act (NZ), secs. 11, 12.

92 Keri Neilson et al., Waikato and Waipa River Restoration Strategy (Waikato Regional Council in association with DairyNZ and Waikato River Authority, 2018), 14; Keri Neilson et al., Waikato and Waipā River restoration strategy. Volume 1: Report and References (Waikato Regional Council Technical Report 2018/08), 5.

93 Keri Neilson et al., Waikato and Waipa River Restoration Strategy, (see note 92), 15.

94 Ibid., 258.

95 ‘Waikato Regional Policy Statement: Te Tauākī Kaupapahere Te-Rohe O Waikato (No 2)’ (2006), https://www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/council/policy-and-plans/regional-policy-statement/.

96 Ibid., cl. 8.

97 Ibid., cl. 3.14.

98 Waikato Regional Council, Waikato Regional Plan 2007, https://www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/council/policy-and-plans/regional-plan/#e5931.

99 Iwi management plans are referred to as environmental plans in the Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act 2010 (Upper Waikato River Act) (NZ) and iwi environmental management plans in Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act 2012 (NZ).

100 Resource Management Act 1991 (NZ), secs. 35A and 26B respectively.

101 Ibid., sec. 35a.

102 Ibid., secs. 61(2A)(a), 66(2A)(a), and 74(2a).

103 Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act (NZ), sec. 42(2).

104 Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act (NZ), secs. 41–4; Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act (NZ), secs 41–4.

105 Defined in Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act 2012 (NZ), sec. 4 as ‘the deep felt obligation of Maniapoto to care for and protect te mana tuku iho o Waiwaia and to instil knowledge and understanding within Maniapoto and the Waipa River communities about the nature and history of Waiwaia’.

106 Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act 2012, (NZ) secs. 17–20.

107 Ministry for the Environment (NZ), ‘Review of the Waikato and Waipa Rivers Arrangements 2016-17’ (Crown Report for Collective Review 2017); Waikato River Authority, ‘Five Year Report’ (Waikato River Authority 2015); Brough Resource Management Ltd, ‘Effectiveness Review of the Waikato and Waipa Rivers Co-Governance and Co-Management Framework’ (Report prepared for the Ministry for the Environment 2017).

108 Ministry for the Environment (NZ) (see note 107).

109 Waikato River Authority (see note 107); Brough Resource Management Ltd (see note 107).

110 Ministry for the Environment (NZ) (see note 107); Auditor General of New Zealand, Principles for Effectively Co-Governing Natural Resources (2016).

111 Marama Muru-Lanning, ‘The Key Actors of Waikato River Co-Governance: Situational Analysis at Work’, AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 8 (2012): 128; Marama Muru-Lanning, Tupuna Awa: People and Politics of the Waikato River (Auckland University Press 2016); Meg Parsons, Karen Fisher and Roa P. Crease, Decolonising Blue Spaces in the Anthropocene: Freshwater Management in Aotearoa New Zealand (Palgrave Macmillan 2021).

112 Meg Parsons, Karen Fisher and Roa P. Crease, Decolonising Blue Spaces in the Anthropocene: Freshwater Management in Aotearoa New Zealand, (see note 111).

113 Waikato River Authority, ‘Review of Te Ture Whaimana’ <https://waikatoriver.org.nz/te-ture-whaimana-review/>.

114 Heather Paterson-Shallard et al., ‘Holistic approaches to river restoration’, (see note 1).

115 Margaret Kawharu, ‘The “Unsettledness” of Treaty Claim Settlements’, The Round Table, 107, no. 4 (2018): 483–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2018.1494681.

116 Marama Muru-Lanning, The key actors of Waikato River co-governance: Situational analysis at work, (see note 111), 130.

117 Fisher et al., Broadening Environmental Governance Ontologies, (see note 6), 611.

118 As mentioned above, local Iwi and Hapū are called tangata whenua, which literally means ‘people of the land’, emphasising this deep connection.

119 Fisher et al., Broadening Environmental Governance Ontologies, (see note 6), 611.

120 ‘Waikato Regional Policy Statement: Te Tauākī Kaupapahere Te-Rohe O Waikato (No 2)’.

121 Fisher et al., Broadening Environmental Governance Ontologies, (see note 6).

122 Neilson et al., Waikato and Waipa River Restoration Strategy (see note 92); see also Waikato Regional Council, Freshwater Policy Review.

123 The Waiwaia Accord was signed on 27 September 2010.

124 Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act (NZ), sec. 4.

125 Ibid., sec. 8(3).

126 Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act (NZ), sec. 4.

127 Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act (NZ), sec. 3.

128 Ibid., sec. 3.

129 Ibid, sec. 4.

130 Elizabeth Macpherson, Can Western Water Law Become More “Relational”? (see note 33).

131 Margot E Salomon, ‘Culture as an Alternative to “Sustainable Development”’, Third World Approaches to International Law Review (TWAILR): Reflections (blog), July 7, 2022, https://twailr.com/culture-as-an-alternative-to-sustainable-development/. While Salomon is particularly focused on the distinct forms of culture reflected by peasants, she acknowledges the relevance of this argument to Indigenous peoples.

132 Ibid.

133 Giada Giacomini, Human Rights Violations in the Name of Environmental Protection, (see note 12), 509.

134 Ibid., 509.

135 Ibid., 518–19 citing H. Jonas, D. Roe, J. E. Makagon, ‘Human Rights Standards for Conservation An Analysis of Responsibilities, Rights and Redress for Just Conservation’, Natural Justice & IIED, 2014, available at https://naturaljustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Human-Rights-Standards-Conservation.pdf.

136 Miriama Cribb, Macpherson, and Axel Borchgrevink, Beyond Legal Personhood for the Whanganui River, (see note 31).

137 Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act (NZ), sec. 12.

138 Ibid., sec. 15.

139 Miriama Cribb, Jason P. Mika, and Sarah Leberman, Te Pā Auroa Nā Te Awa Tupua, (see note 31).

140 Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act (NZ), secs. 27–35.

141 Linda Te Aho, ‘Ruruku Whakatupua Te Mana o Te Awa Tupua – Upholding the Mana of the Whanganui River’, Māori Law Review, 2014, http://maorilawreview.co.nz/2014/05/ruruku-whakatupua-te-mana-o-te-awa-tupua-upholding-the-mana-of-the-whanganui-river/. The origins of this idea is usually credited to a 2010 research paper by Morris and Ruru, which referred to Christopher Stone’s 1972 article ‘Should trees have standing?’, see James D K Morris and Jacinta Ruru, ‘Giving Voice to Rivers’, Australian Indigenous Law Review 14, no. 2 (2010): 49–62.

142 Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act (NZ), sec. 14.

143 See, e.g., Craig M. Kauffman and Pamela L. Martin, The Politics of Rights of Nature: Strategies for Building a More Sustainable Future (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2021), https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13855.001.0001; Cristy Clark et al., ‘Can You Hear the Rivers Sing? Legal Personhood, Ontology and the Nitty Gritty of Governance’, Ecology Law Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2019): 787; Abigail Hutchison, ‘The Whanganui River as a Legal Person’, Alternative Law Journal 39, no. 3 (2014): 179–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X1403900309; Christopher Rodgers, ‘A New Approach to Protecting Ecosystems: The Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017’, Environmental Law Review 19, no. 4 (2017): 266–79, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461452917744909.