ABSTRACT

Rights of Nature or Pacha Mama (RoN), as recognised in the Constitution of Ecuador, are developed through an intercultural dialogue with Indigenous Peoples, encompassing various forms and senses of justice and nature conceptions. RoN has been embraced within their struggle and should support their legal instruments, such as the Kawsak Sacha or Living Forest declaration. This declaration serves as a legal and political tool for achieving self-determination and autonomy, with the Kichwa People of Sarayaku as legal and political actors, designating their territory in the Ecuadorian Amazon as ‘a living and conscious being, the subject of rights.’ In this article, I explore the interplay and sometimes conflicting relationship between RoN and Kawsak Sacha or Living Forest law, in which the Living Forest itself is the source of the law. Through co-theorization, ethnography, and scholar-activism, I delve into the legal foundations of Kawsak Sacha law, its collective intercultural and intercosmic translation into written textual form, and its enforcement grounded in forest moralities, kindred knowledge, and Sacha Runakuna – the Living Forest entities that shape the legal landscape within the territory of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku.

Setting the living forest scene

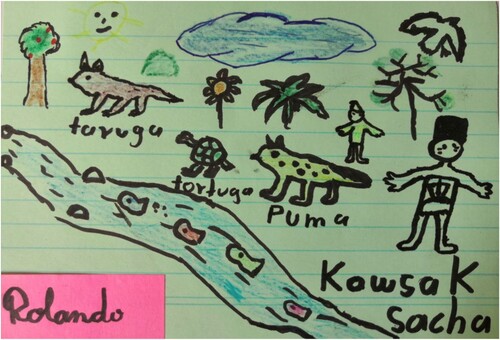

The drawing below, created by Rolando,Footnote1 a young member of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku in the Ecuadorian Amazon, uses markers, crayons and colours to feature a range of elements. These include trees, a puma [jaguar – Panthera onca], a river with fish, stones, a bird, a human person and a supay [spirit, legal guardian]. For Rolando, this drawing represents his interpretation of ‘Kawsak Sacha’ as ‘the world of the forest’ .

In this paper, I delve into the intricate relationship between various legal frameworks, with particular focus on the Rights of Nature (RoN) as recognised in the Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador (CRE), and their interaction with a crucial element of Sarayaku’s legal framework: The Kawsak Sacha declaration. This declaration represents Sarayaku’s engagement and ‘Indigenous lawyering’,Footnote2 considering a specific cosmos and a minga jurídica or collective legal work.Footnote3 The concept refers to the collective word and action in assemblies, decision-making and the creation of concepts and law.

Kawsak Sacha, translated as ‘Living Forest’, holds immense political significance, deeply intertwined with the historical struggle for the self-determination and autonomy of the Kichwa Nationality within their ancestral lands.Footnote4 The concept of Sumak Kawsay [Good living], originally theorised in the 1990s by Kichwa anthropologist Carlos Viteri Gualinga,Footnote5 has played a pivotal political role, positioning the Kichwa People of Sarayaku as influential political actors in shaping the CRE and within the Latin American Indigenous movement. Notably, the 2002 trial against the Ecuadorian state,Footnote6 which had allowed an oil company access to the territory, exemplifies how the law can be mobilised for political purposes.

The Kichwa People of Sarayaku are not isolated actors but part of a collective, joined by other Peoples and NationalitiesFootnote7 in Ecuador. They have not only advocated for the well-being of all life in the forestsFootnote8 but have also gained support from powerful allies and political figures,Footnote9 including those represented by Rolando. Through their political efforts, rights have been, negotiated, gained and achieved,Footnote10 significantly influencing the state’s legal framework. Examples of this influence include the recognition of plurinationality and interculturality principles under the CRE, the incorporation of the Sumak Kawsay principle, the establishment of collective rights for Peoples and Nationalities (Art. 57–66), the acknowledgment of their own legal systems (Art. 171) and innovations aimed at asserting rights to Pacha Mama, commonly known as RoN (Arts 10, 71–74).

Within this constitutional framework, the Kichwa People of Sarayaku have strategically coordinated their political actions, engaging not only to protect their fundamental human rights but also to assert their specific rights as Indigenous Peoples. They have established a robust political organisation, structure and legal frameworkFootnote11 that operates together with customary, state and international law. This engagement goes beyond addressing resource conflicts and extractivism; it encompasses a unique cosmic conception, Kawsak Sacha, which influences the enforcement of laws within the Sarayaku territory.

In the Kawsak Sacha cosmos, the entities or life forms that inhabit the Living Forest play a central role in shaping the laws and norms within the territory. Inspired by scholars like Kirsten Anker, Margaret Davies, Cormac Cullinan and Ursula Biemann,Footnote12 whose works resonate with RoN, Earth JurisprudenceFootnote13 and the legal practices of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku, the law is not confined to the written legal framework of Sarayaku but is embodied in the Living Forest itself. It finds expression in various forms,Footnote14 including bodies, poems, stories and songs. The law is articulated within the pluriverse of the Kawsak Sacha, which encompasses six worlds – animal, cosmic, spiritual, vegetal, mineral and human – along with the Sacha Runakuna, the (in)visible forest beings/dwellers.Footnote15

Kawsak Sacha law is engraved in the forest entanglements, with the territory serving as the source of law.Footnote16 For the Runa,Footnote17 their territory, officially recognised with land titles since 1992, represents ‘the place where their coexistence takes shape, where the necessary conditions exist for the life of the Sacha Runakuna in all its diverse forms’.Footnote18 This ‘forest normative web’Footnote19 is evident in the knowledge of the forest kin, where the law coexists with the lives of the Sacha Runakuna.

The concept of ‘kindred knowledge’, referred to as Sacha Runa Yachay,Footnote20 is interwoven through the people’s coexistence with the beings of the Living Forest and their teachings. In this context, the forest’s normative web extends beyond human-constructed moral worlds,Footnote21 navigating the fluid interplay between good and evil, sharing moralities among the Sacha Runakuna.

Sarayaku, a single territory comprising seven ancestral communities, is home to 1,270 people and 289 families. Within this territory, the application of Kawsak Sacha law, what I call ‘selvar’, considers intercultural and intercosmic elements, specific rights and duties, and adheres to the rhythms of Living Forest law.Footnote22 This application goes beyond constitutional rights, articulating its principles both within and beyond the territory through the Living Forest declaration, designating the 135,000-hectare territory as ‘Kawsak Sacha, a living and conscious being, the subject of rights’.Footnote23

This declaration raises intriguing questions, particularly when considering that the CRE itself already grants rights to Pacha Mama. The coexistence of RoN with the existing legal framework sometimes leads to conflicts and challenges the definitions of justice and beings: for ‘whom’ and ‘what justice’ is at stake.Footnote24 Within the RoN framework, anthropologist Erin Fitz-Henry calls for the preservation of the rich diversity of human and more-than-human relations in Indigenous contexts regarding RoN and multispecies justice,Footnote25 emphasising the importance of embracing ‘ontological and cosmological differences’.Footnote26

Drawing on over four years of fieldwork, I present an ethnography of Kawsak Sacha law, building on scholar-activist research, multispecies ethnography and an in-depth analysis of the Kawsak Sacha declaration. My scholar-activism involves collaborative work with the Kichwa People of Sarayaku in general, in the form of co-theorisationFootnote27 of reports and academic publications,Footnote28 drafting legal documents, accompaniment of community group discussions with other legal scholars and participation in conferences.

In the initial section of my paper, I approach the RoN framework from an intercultural perspective, examining its application, including recent instances in the Constitutional Court rulings of Ecuador. Kawsak Sacha represents a distinct cosmopolitical legal project,Footnote29 complemented by RoN. Moving on to the second section, I delve into the legal framework of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku, offering an in-depth exploration of Kawsak Sacha law and its role in shaping the legal framework of Sarayaku. The third section addresses the translation challenges and tensions, particularly in translating Living Forest law into the Kawsak Sacha declaration. In the fourth section, I focus on the application of Kawsak Sacha law within the territory, emphasising that Kawsak Sacha law serves as a map,Footnote30 with a tolerance for legal enactments and forest moralities.

In conclusion, the integration of RoN into the struggle of Peoples and Nationalities represents a strategic move that serves as a vital component of their toolbox. Sarayaku, as a political actor, goes beyond mere recognition by embodying the Kawsak Sacha declaration, legitimising and materialising Living Forest law. This innovative approach is driven by the pursuit of basic human rights, the empowerment of RoN through intercultural and intercosmic dialogue and the assertion of control over the ‘goods of life’.

Within the territory of Sarayaku, the justification for the Kawsak Sacha declaration echoes sentiments about ‘the persistence of extractivism’, ‘the need for the execution of nature’s rights,’ and the desire for a ‘legal instrument for self-armoring’. For Sarayaku, Kawsak Sacha is seen not only as the ‘true application of RoN’ but also as a ‘pathway to autonomy’Footnote31 fostering co-governance with all Living Forest entities. As expressed by a woman leader, ‘we only want to defend life, why is the legal system so complicated?’Footnote32

Pacha Mama’s rights (dis)enchantment

Ecuadorian scholars Adriana Rodríguez Caguana and Viviana Morales Naranjo aptly assert that ‘rights of nature have sparked a legal and political debate in the region and the world’.Footnote33 These rights have taken many shapes,Footnote34 have been legally transplanted and are gaining traction even in far-away Europe,Footnote35 with their roots found in the recognition of these rights in the CRE in 2008. This recognition was loaded with criticism and even ‘attacks and ridiculisations’, including statements such as: ‘Will a plant be able to sue, will the mangrove or the forest be able to fit in a court of law, will the white cockroach be able to defend itself against its inevitable extinction?’Footnote36

RoN are perceived to have Indigenous law and jurisprudence as their foundations, although not always articulated explicitly in the language of RoN. Moreover, not all Indigenous Peoples support these rights; some even distance themselves from this legal framework.Footnote37 Wiradjiri Nyemba legal scholar Virginia Marshall argues that RoN strips nature into parts by endowing it with rights.Footnote38 Legal anthropologists Keebet von Benda-Beckmann and Bertram Turner point out ‘how actors use and generate the law’ and it merits, emphasising that this is the case with RoN where ‘law is central to any ontological notion of reality. From this, further points follow. Assemblages of normativity are diverse and the same legal phenomenon can be differently enacted in different realities’.Footnote39

The CRE is described as an ‘intercultural constitutionalism’,Footnote40 deeply rooted in the principles of plurinationality and interculturality, aligning with the political project of Peoples and Nationalities.Footnote41 This aligns RoN with the decolonising agenda in Ecuador,Footnote42 extending beyond granting rights to Pacha Mama and nurturing a broader perspective on ‘natures’Footnote43 and cosmos as well as on communitarian forms of senses of justice for Pacha Mama in line with intercultural justice.Footnote44

Recent theoretical engagements with RoN in the CRE interpretate them as ‘ontologies of Amazonian indigenous nature’,Footnote45 reflecting a ‘politico-cultural hybridisation […],’ ‘including many romanticised constructions’Footnote46 of the non-indigenous, ch’ixi in Bolivian Aymara Silvia Rivera Cusiqanqui’s sense.Footnote47 RoN are also seen as an expression of customary lawFootnote48 and ‘ethno-environmental concerns’Footnote49 alongside Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

Nevertheless, the application of RoN in the Ecuadorian context, especially under article 71, has been met with ambivalence and (dis)enchantment.

Possible reasons are that under Art. 71, everyone can speak for Pacha Mama and misuse these rights. Plus there are contradictions in the CRE, a not uncommon aspect of all constitutions,Footnote50 as in Arts. 1 and 408, which state that non-renewable natural resources are property of the state.

In sum, Ecuadorian actors themselves have not made much use of these rights until 2017, which also had an impact on the process of the cases and the sentences, if they have been politicised.Footnote51 And as one of my Runa interlocutors, who participated in the process behind the recognition of RoN, mentioned, ‘not even we are sure how to enforce these rights’.

The latest jurisprudence on these rights shows more positive advancements, with even cloud forests, monkeys and frogs winning in court.Footnote52 Contrary to scholars’ criticism of the anthropocentric character of the CRE,Footnote53 the Constitutional Court of Ecuador has now elaborated on the right to a healthy environment, human rights and rights to the city by affirming that RoN operate together with these human-centred rights.Footnote54 Moreover, in the context of developing RoN jurisprudence, an interspecies principle has been proposed, suggesting that ‘specific characteristics, processes, life cycles, structures, functions and evolutionary processes differentiate each species’. For example, an Andean condor [Vultur gryphus] will have different rights than an Amazonian pink dolphin [Inia geoffrensis].Footnote55 The other principle is the ecological interpretation, ‘which respects the biological interactions that exist between species and between populations and individuals of each species’.Footnote56

In January 2022, the A’i Cofán community of Sinangoe obtained a court ruling that links the right to prior consultation with the principles of plurinationality and interculturality.Footnote57 Although they received a favourable verdict on 31 October 2023, they mobilised from the Amazonian territory to the Constitutional Court to demand compliance with environmental remediation and the removal of mining concessions.

There is a research gap regarding how RoN and collective rights or specific rights of Peoples and Nationalities are invoked and how their effects relate to or enter into potential conflicts.Footnote58 In this sense, Peoples and Nationalities in Ecuador expressed concerns that their traditional practices, as recognised in the CRE in the sections on collective rights (Arts. 56–60), were under threat. This sentiment is also shared by the Sarayaku Runa.

In the case of the ‘Triángulo de Cuembí’, the court affirmed the following:

[A]lthough environmental conservation and the protection of the rights of nature is a valid objective, it cannot be achieved at the cost of denying the rights of Peoples, communities, and Nations, but in harmony with these rights.Footnote59

In examining the role of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku, legal scholar Ramiro Ávila Santamaría describes the Kichwa People of Sarayaku as ‘the best constitutionalists’Footnote63, underscoring their pivotal contribution of giving content to RoN. Similarly, researcher and political activist Leonidas Oikonomakis contextualises the Kawsak Sacha declaration within the RoN framework, emphasising its core objective of granting rights to the Sacha Runakuna [(in)visible forest beings/dwellers].Footnote64 Anthropologist Eduardo Kohn underscores the document’s radical nature, describing it is a ‘political proposal […] to transform our laws’.Footnote65

These insights shed light on three significant dimensions: firstly, the declaration is interpreted as promoting RoN; secondly, the perception of RoN as not inherently bestowing rights upon Living Forest entities; and thirdly, the transformative impact of RoN recognition on state law, making it adaptable for Kawsak Sacha. As eloquently articulated by feminist scholar Andrea Sempértegui, ‘The Living Forest is a political forest because it sustains territorial struggles through practices of forest-making that nourish these practices’.Footnote66

Despite Sarayaku’s utilisation of its Living Forest law, which encompasses the declaration and employs the language and terminology of RoN, it is imperative to exercise caution when framing the Kawsak Sacha declaration solely within the RoN context. There are other significant considerations at play, which may limit the seamless integration of RoN into Kawsak Sacha. RoN could intentionally colonise political projects through environmental colonialism and ‘environmentality’, to use Foucault’s terminology.Footnote67

In this context, the rights-bearing status of Pacha Mama should not overshadow the ongoing decolonisation efforts in law, potentially being wielded against the Kichwa People of Sarayaku without due respect for their intercultural, intercosmic and understandings. Instead, the Runa are incorporating RoN into their own forest normative framework, Kawsak Sacha law. RoN should function as a complementary legal element, strengthening the foundations of Kawsak Sacha.

I argue that Kawsak Sacha should not be equated with RoN but should be acknowledged as a cosmopolitical legal project in its own right. It represents a way of enacting worlds by building upon forest moralities, Sacha Runakuna and kindred knowledge. Kawsak Sacha, as a form of law, utilises the ‘law as a language of politics’,Footnote68 acknowledging that law encompasses ‘not just rules, but a complex set of intellectual, social, political, and ethical practices’.Footnote69

Kawsak Sacha as a law

As legal anthropologist Rachel Sieder argues, the question of ‘what is and what is not law?’ is widely discussed in the anthropology of law.Footnote70 Legal scholar Brian Tamanaha, for instance, agrees that if actors choose to call their normative ways ‘law’, they have the right to do so and we need to accept this.Footnote71

Legal anthropologist Sally Engle Merry provocatively says in her still very relevant work on legal pluralism:

Why is it so difficult to find a word for nonstate law? It is clearly difficult to define and circumscribe these forms of ordering. Where do we stop speaking of law and find ourselves simply describing social life? Is it useful to call all these forms of ordering law?Footnote72

One of these normative systems is Kawsak Sacha law, a normative forested web in a specific space, the territory of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku. Kawsak Sacha law is what Nicole Graham calls a lawscape,Footnote78 the expressions of law in a certain space. It is in this sense that my Runa companions say ‘each forest is different’.

Other than RoN, Kawsak Sacha law is a Living Forest that does not need to be endowed with rights or legal personhood as it exists without human normativity. However, while writing this, I am thinking of how in the Spanish version of Wild Law, Ramiro Ávila Santamaría describes the rights ‘of mammals, plants, minerals, planets and stars. In each of them there are the rights of the dolphins, lions, dogs, rats, forests, plants, grass, mountains, rivers, water basins, subsoil, atmosphere. All these juridical systems make the Earth Law. […] The right of humans to adapt to Earth Law is the right that is call Wild Law’.Footnote79

Such a reading of the law resonates with what Margaret Davies calls ‘Ecolaw,’ where ‘human law is not the only part of the story’ and it ‘is not human law that governs the environment or ecosystems’Footnote80 – or, from a multispecies justice angle, when natural entities have their own life projects.Footnote81 In line with Davies’ approach, Kawsak Sacha law rather operates in biological processes and in the ‘onto-juridical conviviality’ with exchanges between the Kawsak Sacha pluriverse, to which the human world also belongs.

Following von Benda-Beckmann and Turner’s affirmation that law can be codified, written and oral,Footnote82 the Kawsak Sacha law is codified along similar lines, as alluded by Indigenous intellectual Irene Watson for the Australian context:

Law stories lie across the land: they are alive and can be revived and regenerated … The law is my centre, from which my life forms … Law is sung into place, land, waters, people, the natural world and the cosmos, the sky-world. It is law that I speak of here, not ‘customary law’, lore, myth or story.Footnote83

Other sources come from ‘re-storying the law’Footnote86 or ‘law as stories’Footnote87 in the context of Sarayaku. For example, wise woman Doña Narciza told me the story of kushillu, the chorongo monkey [Lacroix lacroix]:

The ancients say that in a festival of the Uyantza, a man was not hunting anything and he met the Kuraka of the kushillu, a chorongo monkey, who told him that he can take only ten monkeys and cannot tell anyone how he got them, if he told what happened he would die, and indeed that is what happened.

As pointed out by von Benda-Beckmann and Turner, ‘[e]ach system has its laws of dealing with other legal systems’,Footnote88 and this is also characteristic of Kawsak Sacha law. In this sense, Kawsak Sacha law exists on its own but has shaped the legal instruments of Sarayaku, the CRE and instruments of international law, with which it operates and coexists together and sometimes even clashes. And when, in the words of legal Scholars Louis Kotzé and Rakhyun Kim, ‘humans make laws to regulate society’,Footnote89 the Runa take part in the normativity of the Living Forest as part of the pluriverse.

Together, all these instruments form the specific legal order of Sarayaku, which reflects all the dimensions of legal order as defined by von Benda-Beckman: ‘degree of regulation, institutionalization, differentiation, systematization, modes of sanctioning, spatial and social scope of validity, and basis of legitimacy’.Footnote90 The important notion underlying these dimensions is that Living Forest law is independent in some respects, like biological law,Footnote91 while relying on other instruments and dimensions in other respects – all forms of law are mixed in some way. This echoes de Sousa Santos’ concept of interlegality, ‘the mixture of legal orders’.Footnote92

The following legal instruments, codified and written down on paper, are part of the legal framework in Sarayaku:

The Statutes are the Sarayaku local Constitution, last revised on 29 August, 2021. The preamble, inspired by the preamble of the CRE, reinforces the concept of Kawsak Sacha as a form of Living Forest Constitutionalism grounded in the existence of the Sacha Runakuna and their kindred knowledge:

CELEBRATING Kawsak Sacha – Living Forest of which we are a part and which is vital for our existence, INVOCATING the protective beings of the Living Forest – Kawsak Sacha, RECOGNISING our diverse forms of spirituality, RESPECTING and APPEALING to the wisdom of our ancestors who enriched us as the Original Kichwa People of Sarayaku, and as HEIRS of 528 years of struggle and resistance for life.

The statutes regulate, among other things, the juridical collective personhood of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku (Art. 6), Peoples and Nationalities’ behavioural norms as the foundations ‘for building a plurinational and intercultural state’ in line with the Sumak Kawsay, in particular with Runawas sachawas sumaklla kawsana [respect for Pacha Mama and balance of the Kawsak Sacha]. Other regulations include the rights and duties of the Runa (Art. 14 & 15), institutionality (Art. 40), the administration of Indigenous justice (chapter 7), the territory as a collective property (Art. 51) and a reaffirmation of the declaration of Kawsak Sacha as a ‘living entity, conscious with rights’ (Art. 58).Footnote93

The Life plan or Sumak Kawsay plan, the plan to reach a good life, as its name says. For the Runa, their Sumak Kawsay has three pillars: the Sacha Runa Yachay [knowledge of the Amazonian being], Sumak Allpa [land without evil] and Runa Kawsay [life of the people].Footnote94 To this date, there exists only one version of 2011, which is for all the seven ancestral communities, but there is a current project on developing one for each community since they differ in terms of their needs and size.

The Norms of conviviality, last updated in 2013, with a short preamble and nine chapters that regulate a variety of aspects with regard to hunting, the usage of goods of life, fishing, threats to members or Yachaks [wise person], the regulation of prices of game meat and other ‘products’, the rights of youth and children and sanctions.Footnote95

The Kawsak Sacha Declaration of 2018, with a philosophical preamble and six articles that elaborate the concept of Kawsak Sacha. While not having specific rules of enforcement, it has two main foundations: (Art. 1) the territory is declared as Living Forest, with rights and (Art. 2) free of extractivism.Footnote96

The Sarayaku community’s own written legal interpretation of the right of free, prior and informed consent.Footnote97

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) sentence against the Ecuadorian state.Footnote98

In terms of institutionalisation, the Tayjasaruta [government council] with its respective Tayak apu [president] as well as a group of ten leaders [dirigencias] are elected by the people for a three-year term: they are in charge of matters concerning women and family, education, community management and economy, wise (wo)men, goods of life and territory, Kawsak Sacha, transportation, communication, international relations, youth and health. The Kurakas [traditional authorities] for the seven ancestral communities, who rotate every year, are a figure that is inspired by the Sacha Runakuna and kindred knowledge. Each group has its own Kuraka, who organises, guides, protects and gathers them and is accompanied by the Likuatis, who are the escort of the Kurakas. However, the Sacha Runakuna, especially the vegetal beings, rotate less often than the Runa, as my host mother intimated me.

We may thus say that there is a form of territorial governance among the Sacha Runakuna, too, which could be read as traditional figures. A form of co-governance exists with this Living Forest pluriverse because the Runa dwell together with the forest beings and enact the forest normative web, and thus decision-making in the territory is a joint endeavour involving all of its inhabitants. For example, Article14.b (statutes) stipulates that everyone has a voice and a vote in the assembly. Humans raise their own voices, while other beings, like, for example, toucans (Ramphastos) or maniocs (Manihot esculenta) are represented by humans if there is something to complain about, such as hunting excesses or bad crop maintenance.

The office of the human political representative, on the other hand, has been adopted from the state’s institutions to enforce the law. One time when I met Guido, the previous political representative, he had in his one hand the CRE and the Ecuadorian penal code, while holding the statutes and the norms of conviviality in the other. The ancestral judges are another key figure contributing to law enforcement. Specific punishments and their case-to-case application are discussed within the community. While Sarayaku has advanced regulations in terms of managing the goods of life – the result of an ongoing learning process – other aspects, such as domestic violence, are not addressed, but the Runa are aware of these deficits.

In summary, Kawsak Sacha law as a practice has already been there before the act of writing it on paper Kawsak Sacha law operates as a map, and in line with the understanding of the Runas, each forest is different. Therefore, the act of selvar refers to the application and enforcement of Kawsak Sacha law within the ‘mapas mentales de la selva’ [mental maps of the forest] of a specific forest and its logics. This makes reference to the perspective of the Runa, who claim to have mental maps of the Living Forest.

Cartographies of forest law-making

‘We have orality, not paper or pencil.’ Hilda – Sarayaku leader

The intercultural and intercosmic process of translating Kawsak Sacha law to outside the territory has caused debates among the Runa: would ‘people from outside’ interpret the declaration differently than it is interpreted in the territory? Formulating the declaration in legal language understandable for external audiences has been a major challenge for the Runa, as there have been different unwritten interpretations as to what type of legal instrument the declaration actually is – RoN, a new category, a new form of territorial governance, etc.

Anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro points out that such translations are not exempt of equivocations.Footnote100 Moreover, and once again picking up on the metaphor of ‘law as a map’, maps ‘distort reality, have tensions, are inaccurate,’Footnote101 an exact map of Kawsak Sacha law in the declaration is thus not possible.

There are different definitions of the attempts to translate Kawsak Sacha law into text, which have been developed throughout the four existing versions of the declaration and complement each other organically.Footnote102 Kawsak Sacha can be a philosophical principle,Footnote103 the living space of all beings in the forestFootnote104 or a being in itself.Footnote105 In the fourth version of the declaration, Kawsak Sacha has rather multiple meanings in one passage:

It is our life, our vision, our knowledge and wisdom, our principles and values, our freedom and joy, our sumak kawsay … It is our territory, its forests, rivers and streams, our natural medicine; it is the exchange, the good dialogue, living and working together … in unity … Footnote106

The Living Forest pluriverse lays the foundations for a guiding concept of Kawsak Sacha, which has been developed throughout four versions and adapted in article three of the 2018 official version.

Through my analysis of the declaration’s different versions, I have identified certain dimensions in the versions: reasons for or foundations of the declaration, the objectives, the legal status given to the Living Forest or to the Sacha Runakuna and, last but not least, existing legal instruments on which the declaration builds, including the adoption of the legal language of RoN. All these dimensions influence the structure of the versions. For reasons of space, this paper will present only the ones that are most repeated throughout the different versions. The reasons for or foundations of the declaration are that the forest is alive due to the beings inhabiting it. Other reasons refer to ancestry, as attributed to the Sacha Runa Yachay, to prevent extractivism and false consultations. Finally, the most relevant or most repeated reason is the fact that the declaration is an urgent and concrete proposal from the territory, specific to (its) Peoples and Nationalities. The objectives take different forms, from the continuity of life, so that the songs in the forest continue, to protecting the rights of Peoples and Nationalities. In the same vein, arguing that Peoples and Nationalities are part of the forested worlds, anthropologist Lisset Coba and geographer Manuel Bayón write:

There is no indigenous territory without forest, the people are part of the forest, the forest is part of their political organisation. Territory is a political concept with porous borders that link history, geography and the body. The defence of the place is the defence of existence, the forest has an intrinsic value.Footnote108

Other sources on which the declaration draws are international law instruments, the ILO Convention 169 of 1998, the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the Declaration of the Peoples of the Inter-American Court, which allow to defend these worlds on the basis of reasonable arguments.Footnote110

It is remarkable that only Art. 1 of the third version and the Pakkiru (Kichwa Nationality political umbrella organisation) proclaim the forest as a ‘living and conscious being, a subject of rights’. Furthermore, having endowed the forest with rights, the official third version states, ‘[t]his is something that we, an ancestral nation, have recognised since time immemorial’.Footnote111

The first and the second versions, on the other hand, do not attribute the forest with a legal status. In the first version, however, the RoN are described together with Sumak Kawsay and plurinationality as the ‘best weapon of territorial defence’. The second version, while also not giving legal personhood to the Living Forest, makes reference to CRE Arts. 71–74.

The Runa argue that the Living Forest has intrinsic value for the collective of beings inhabiting it and affirm its aliveness and kin relationship with Peoples and Nationalities in the Amazon. As Hilda, a Sarayaku leader, reflects on the Kawsak Sacha articulated in these rights:

We have learned to use the law, they give you importance if you speak with state law, we have recognised our existing rights and we articulate this in the Kawsak Sacha. We are not afraid to be declared Kawsak Sacha and thus enforce the rights in the Constitution.

Kawsak Sacha pedagogies: vegetal laws

Yaku once told me about an exchange he had with a member of the Wampis nation, who elucidated his People’s understanding of the concept of ‘conserving the territory’: neither does ‘conserving’ mean that a forest is put into a closed tin can nor that the Indigenous person is the guardian on the side. As Sônia Guajajara of the Arariboia Indigenous Land in Brazil recounts, ‘we cannot live without the river and the river cannot live without us’.Footnote112 It is the relationship with these forest livesFootnote113 that opens the still very relevant discussion about conscious or unconscious conservation.Footnote114

A discussion not without challenges is whether the Kawsak Sacha needs to be sustained in the territory in line with traditional intercultural elements and the act of selvar. Similar challenges are described for RoN, that they ‘require an epistemic, ontological and axiological exercise corresponding to the ecological balance’.Footnote115

In this sense, the Kawsak Sacha pedagogy of making everyone acquainted with the declaration helps to incorporate the concept and to change practices while remembering the kindred knowledge learned from the Sacha Runakuna. But although the declaration was drafted collectively, not all Runa accept or have read the declaration, and not all of them participate in the forested normative web in the same manner. Or, in the words of von Benda-Beckmann and Turner, the ‘interpretation, confirmation, validation, reproduction’Footnote116 differs.

Organising and adapting to new circumstances has proven key to the care for the forest kin, for example, by developing a legal framework as elaborate as the Kawsak Sacha declaration. Incorporating the work of the kaskiruna team [guardians of the forest] (Art. 49 statutes and Art. 3, Chapter III, norms of conviviality) in creating territorial governance plans has been part of the learning process of documenting, defending and sustaining the territory. The kaskiruna team monitors the forest beings and subsequently makes collective decisions. They convene every six months in each ancestral community to discuss how and to what extent hunting should be conducted.

While everyone in Sarayaku may know stories about plants that contain a normative message – the dos and donts associated with specific vegetal beings –, they may not consciously these as law.Footnote117 The wituk [Genipa americana] and the achiote [Bixa Orellana] were sisters who were turned into vegetal beings. Depending on how the forest beings behaved with them, they decided what colours to paint them. This is why there are distinctions, for instance, in the colours of parrots [Psittacidae] and monkeys – serving as a kind of colour indicator for morality.Footnote118

Other norms engraved in the Living Forest, I was told, are expressed in the form of dreams. In these dreams, trees appear with battered human faces to invoke the forest moralities when cut down in excess. These dream-based laws can be seen as conflicts arising from different interestsFootnote119 in environmental conflicts, leading to ‘potential disagreements’.Footnote120 For instance, consider the conflict over the lispungu, a 20-metre high tree providing fruits to the guantas [Cuniculus paca] and other rodents, used by the Yachak César Vargas for strength and healing medicine.Footnote121 To the oil company CGC, which felled the lispungu, it was just an ordinary tree. For the Runa, however, these trees are part of the forest kin. ‘[T]he aloe vera of the trees signifies the blood of the human beings of ancient times and, although they are no longer human beings, their spirit remains to this day’,Footnote122 and ‘the great trees […] have their own Guardians: they are the Runayuk’.Footnote123 Great trees like the uchuputu and the kamaktua, the home of the Yashinku [protective being], are central to the Kawsak Sacha declaration and featured prominently. While animals are allowed to roam among them or feed on them during their fruiting seasons, they cannot simply be cut down by the Runa.

In my ethnography of Kawsak Sacha law, I have identified practice-changing initiatives in the life plan, such as the sacharuya [botanical garden] where medicinal species are cultivated and seeds are collected for planting .

One species cultivated in the sacharuya is the wayuri palm [Geonoma sp.], the leaves of which are used for weaving the roofs of the wasis [houses] as the one on the meeting house of the sacharuya in the picture in . However, this practice has actually posed a threat to the wayuri population as this palm needs twenty years to grow. The Sarayaku Runa have decided by law to leave four leaves on the palm when they harvest it, ensuring it remains alive and can be harvested again. There are comprehensive rules governing the use of the wayuri.Footnote124 Enforcement is straightforward in case of forest moralities since the entire village can observe a person carrying ‘too many’ palm leaves, and roofing requires a minga, collective work.

The vegetal kindred knowledge of how a house is built ensures its durability, for example, by using woods such as the Kara kaspi, wambula, pujal, known for their longevity. The same principle applies to the wayuri roof. If woven correctly, it can last between 20–30 years, unlike other palm leaves like the makana and yutupi, which require more frequent replacement.Footnote125 Knowing how to care for the wayuri kin woven in the roof, such as exposing them to smoke daily, ensures their longevity as good companions.

The discussion concerning the wayuri palm has led to transformations in its usage. I was informed that ‘it has been a 15-year project to produce seeds for distribution within the community, sowing them on four hectares, and soon, planting them closer to the houses or in the chakra, reducing the need for extensive cleaning and distant repopulation’. Another response to the perceived scarcity of wayuri palms is to purchase leaves from other communities. Some have opted for zinc roofs, ultimately altering the Kichwa house culture. However, some Runa hold a different perspective on this matter. As my host brother Benhur mentioned, ‘they are not in danger; planting them in the sacharuya is merely to have them closer to the village’.

The beat of the drum

Moving beyond the vegetal world’s laws, there has been a process of both agreement and disagreement as hunting weapons have also evolved over time.Footnote126 Carbines and dogs have been introduced, and particularly the older generations believe that hunting does not influence the decline of species.Footnote127 However, not only the older ones share this view. Hilda once recounted an anecdote illustrating forest morality when her children happily brought four guantas. She questioned them, asking, ‘Why did you kill so many? What will you eat tomorrow?’

In Sarayaku, only 10% of the food consumed comes from ‘outside’,Footnote128 while the rest relies on the forest through locally specific agriculture, hunting and gathering practices. Hunting practices are regulated in the norms of conviviality: hunting is permitted only for subsistence (Chapter 1, Art.1) and forbidden for commercial purposes (Art. 5).

If such forms of care for the sacha are expressed in (un)conscious everyday conservation practices, then those who inhabit the forest must be protected, as stated in article four of the Kawsak Sacha declaration.Footnote129 The Sarayaku Runakuna rely on their forest kin and are part of it; hence, they must take care of it. This sometimes entails changing and adapting long-cherished traditions to new situations and challenges. A prime example of the collective learning process required for taking care of the sacha is the recent adding of atayas [chicken] to the local diet. Initially, this was met with disapproval ‘as they were not part of the sacha’, as wise woman Doña Narciza explains. Now, chickens have consciously become important allies and part of the forest entanglements, along with fish farming and hatcheries to enhance food autonomy.

However, the political economy of lifeFootnote130 associated with bushmeat is inherent in the very act of hunting, from teaching a guagua [child] to load the carbine, imitate the forest sounds and learn where the kushillu [chorongo monkeys] can be found during different times of the year. The act of consuming bushmeat establishes a relationship with the forest kin that many are reluctant to abandon for the domestication of the Living Forest pluriverse. For instance, raising peccaries instead of hunting them presents its own challenges. As Benhur explains, ‘You have to know its routines and movements’. Killing a domesticated peccary may feel ‘unfair’ and, most importantly, does not involve any form of engagement with the sacha. From this perspective, domestication means losing the transmission of untamed vitality and the relationality with the forest. This notion is also embedded in the traditional drum, made from the dried hides of a peccary and a cosumbo monkey [Potus flavus], as shown in the picture below. The beat of the drum symbolises the vitality and energy of the peccary, which is not the same when the hides come from domesticated animals. The drumbeat symbolises the Kawsak Sacha law and the practice of selvar as it materialises the actions and changing practices of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku to find once again the legal rhythm with the Living Forest itself ().

Another remarkable example of forest moralities is the Uyantza, a traditional hunting festival that used to be held annually but now takes place every three years. On the one hand, it is considered a festival of abundance, aimed at restoring the balance with the Living Forest, while on the other hand, it is a competition between the prioste [festival hosts] over who hunts more.

In line with lessons from the Living Forest law or the Sacha Runakuna as law-makers, the Runa have consciously chosen to introduce practices of ‘good hunting’. These include not hunting female monkeys carrying babies, not hunting certain species like the tapir [Tapirus terrestris] (Art. 1, Chapter III, norms of conviviality), only hunting one or two specimens of one type of monkeys or other species during traditional festivities and on a daily basis (Art. 7, Chapter III), hunting only three wanganas [Tayasu peccari] and not the entire herd (Art. 7, Chapter 1, norms of conviviality) and allowing the forest to recover.

Quantifying and monitoring the forest kin by the kaskirunas is a challenge that goes hand in hand with forest moralities. But then again, hunting reveals how these forest moralities can be fluid, such as when encountering beings forbidden to hunt or when hunters’ personal decisions depend on sentires [feelings] and the moment.

Hunting tapirs is the most controversial issue, as there is a collective (dis)agreement over whether is prohibited. While in the territory, I once participated in a minga that was the punishment for having hunted a tapir. The fine is 500 dollars or 100 hours of community work (general sanctions, b), as per the norms of conviviality).

Performing the minga is a way of collectively sharing the punishment. This practice, however, is not without dispute: ‘For some, it would be better to use conventional state methods of punishment’ (as outlined under Art. 247 of the Penal Code) to ensure that the law is genuinely enforced, one woman told me, ‘three to four years in prison’. When I asked the person who had hunted the tapir at the last Uyantza about the reason for his fluid morality, his answer was: ‘For feeling and being a real kari [man]’. The act of hunting is directly linked to notions of masculinity in the territory and to subjective manhood. This is also why it is not easy to cease this practice in a setting where hunting is performed by men.

The species hunted during this festival are considered uncommon, not part of daily consumption but reserved for special occasions.Footnote131 Conscious and sometimes disputed practices that make Sarayaku a territory of lifeFootnote132 are the result of kaskiruna monitoring and self-criticism. Notions such as ‘we have depredated the forest’, authors writing about ‘a possible tragedy of the commons’Footnote133 influence the condition that this festival takes place only when the forest kin has had the chance to replenish.

To illustrate these contradictions and fluid moralities, a Sarayaku warmi who ‘defends the forest from her heart’ suggest that the festival should no longer be held ‘because it is the worst enemy, it is not tradition’. In contrast, a male member of the community, after seeing tapir tracks and chorongo monkeys during a trip around the territory, happily concluded that these species may now be hunted again at the next Uyantza after being exempt from hunting for the past four years.

As an expression of resilience in the forms of selvar, the ‘ontological occupation’Footnote134 of the territory had to be zoned: Kawsak Sacha zones, habitable zones, zones for chakra and tree felling, hunting, fishing zones and timbering zones, sometimes leading to fluid moralities and disputes when these zones are not respected.

Forest moralities, kindred knowledge and Sacha Runakuna intersect in practices that cannot necessarily be explained because they are not solely due to human action. Animals already know the hunting grounds, recognise human tracks and avoid these spots. Kaskiruna Dionisio curiously mentioned that he cannot explain why the little agouti [Dasyprocta punctata] and a species of squirrel are no longer present in the territory: ‘How do you explain that they migrated? It’s a lengthy process of understanding that we are investigating. However, other species, like the bigger agouti or the guanta, remain present.’

There is the idea that protector entities, such as the Yashinku, warn the monkeys when humans are approaching, causing them to leave. A similar notion exists regarding the decline of migratory fish, where the Yakuruna and Yakumama, described in the declaration as beings controlling the abundance of the river, ensure that fish migration cycles synchronise with the cycles of vegetal beings, particularly the guabas [Inga edulis].

Over the last few years in Sarayaku, it has been a process of learning, making mistakes and realising that there are fewer goods of life in this forest conviviality. Unconscious practices must become conscious and conscious practices even more conscious. As Rachel Sieder states, ‘law is inherently unstable, dynamic, and constantly contested’,Footnote135 and the same applies to Kawsak Sacha law.

Final reflections

The political ontological act of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku to activate the Kawsak Sacha as a law that ‘interprets the politics of the forest’ and ‘translates the perspectives of other worlds’Footnote136 has been a long-standing endeavour and integral to the activation of RoN within the political project of Peoples and Nationalities. Kawsak Sacha as a law is intricately interwoven with the recognition of specific rights that collectively operate for Peoples and Nationalities in the CRE. Selvar is thus articulated within a plurinational territory, Ecuador, yet it is embedded in ontological occupations and multiple ontologies concerning existence, much like the pluriverse of the Kawsak Sacha.

In their struggle for environmental rights, the RoN and their territory, the Runa reshape the use of state law by referring to ‘living and thinking beings’ instead of ‘natural resources’ and ‘conscious use’ instead of ‘sustainable use’. Kawsak Sacha as a law transcends mere recognition of a forest as ‘a living and conscious being, a subject of rights’; it carries substantive weight. The primary objective is to re-signify internally the concept of Kawsak Sacha as expressed in territorial practices. In other words, as Yaku and I concluded in a conversation on a rainy day, ‘it is not only necessary to understand how a forest thinks but also to question how humans think’. This implies rethinking everyday practices, forest moralities and responsibility to the forest kin. It is ultimately about ‘changing paradigms and actions in the forest without believing that there are more than enough of these living beings’. Sarayaku thus shows that it is possible to preserve the forest and, at the same time, live with it [conservar selvando] and its challenges, such as articulating the Kawsak Sacha outwards and counteracting difficult circumstances in the territory.

In July 2022, an Amazonian COP (Climate Change Conference) was held in the territory of Sarayaku. The idea was to adopt Kawsak Sacha as a global category, ‘minga global por la vida’ [global collective mobilisation for life],Footnote137 in territories of Peoples and Nationalities, as articulated in RoN but with Kawsak Sacha as the source of law.Footnote138 When radical contents start being recognised and ‘when (ontological) alterity is mobilised as a strategy of resistance to dispossession’Footnote139 – as in the living notion shared by Peoples and Nationalities in the AmazonFootnote140 – the positioning of homogenisations of common cosmopolitan projects requires caution.Footnote141 In the common cosmopolitan project of Kawsak Sacha in Amazonian territories, ‘Peoples and Nationalities are not prepared in the same way to live it, we do not want a simple and marketised Kawsak Sacha’, one of the pioneers of the Living Forest declaration sadly reflects.

I argue that the constitutional recognition of Pacha Mama has become a door opener for Kawsak Sacha as a concept – but can also be a straitjacket for a declaration still waiting to be recognised by state law (even though it has already been recognised under the CRE’s principle of interculturality). It opens doors because it actually opens the possibility for ‘living and thinking beings’Footnote142 from this specific cosmos to be recognised by the state. For Mihnea Tănăsescu, RoN are not an ‘end state’ but rather an experiment designed to further empower Indigenous political authority.Footnote143 Nonetheless, it is also a straitjacket because one can argue the case for state legal recognition of the Kawsak Sacha as this forest is already endowed with rights under the legal framework of the CRE.

From my perspective and considering what I have learned from the Kichwa People of Sarayaku, it is crucial that the legal proposals of Peoples and Nationalities are protected. RoN should reinforce these proposals instead of being employed against them. RoN discourses should not impose themselves on Living Forest law; Living Forest law exits in its own right, yet it is intertwined with kindred knowledge and the conviviality of all its six worlds.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my gratitude to the peer reviewers who enriched this text with their invaluable comments and to the editors of the special issue, Rachel Sieder and Ainhoa Montoya. I am also grateful to the conversatorio on rights of nature and territory in Abya-Ayala with the Universidad Salesiana, the IAEN, and the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, in 2021. Special thanks to the comments from the Max Planck Werkstatt last November and to Andreas Gutmann for extensively reviewing the content of the text. This article has evolved from the preliminary results of my forthcoming doctoral thesis and my understanding of the Living Forest and conviviality and engagement in the Amazon with Sarayaku.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jenny García Ruales

Jenny García Ruales, an Amazonian anthropologist, is currently pursuing her PhD at the Philipps University of Marburg and the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Germany. Additionally, she specialises in Peritaje antropológico (anthropological legal expertise) at the Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. She is more recently a research assistant in a project called ‘Amazon of Rights.’

Notes

1 In this paper, I use the names of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku without last names because this is how we relate to each other.

2 I am adopting this notion from a Guatemalan context in which Indigenous lawyering is defined as ‘a unique agency with a direct voice connecting worlds and plurilegal realities.’ For more on this concept, see: Lieselotte Viaene and María Ximena González-Serrano, ‘The Right to be, to Feel and to Exist: Indigenous Lawyers and Strategic Litigation Over Indigenous Territories in Guatemala’, The International Journal of Human Rights, no. 27 (2023): 1–23. doi:10.1080/13642987.2023.2279165.

3 Legal minga o minga jurídica is an adaptation of the concept of faena jurídica, a theoretical and methodological tool developed in collaboration with law-makers and knowers in Indigenous struggles for self-government in Mexico. Orlando Aragón Andrade, ‘El trabajo de coteorización en la antropología jurídica militante. Experiencias desde las luchas por el autogobierno indígena en México’, Inflexiones, no. 6 (2020): 75–106, 90–2.

4 Forest entities have been incorporated into political discourses, and their origins can be traced back, in the case of Sarayaku, to initiatives like the Plan Amazanga by the OPIP, the former Kichwa political umbrella organisation (1992). See, also Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘El Libro de la Vida de Sarayaku para Defender Nuestro Futuro’, in Sumak Kawsay Yuyay: Antología del Pensamiento Indigenista Ecuatoriano sobre Sumak Kawsay, eds. Antonio Hidalgo Capitán et al. (Cuenca: FIUCUHU, 2014), 77–102, 79.

5 Carlos Viteri, ‘Mundos Míticos Runa: Pueblos y Culturas de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana’, in Mundos Amazónicos, eds. Noemi Paymal and Catalina Sosa (Quito: Ediciones Sinchi Sacha, 1993), 144–57.

6 IACtHR, 27th of June 2012, File Number Series C No 245 – Kichwa Indigenous People of Sarayaku v. Ecuador.

7 In the Ecuadorian context, Indigenous Peoples identify themselves as Pueblos y Nacionalidades ‘Peoples and Nationalities,’ a term recognised in the Spanish-written Constitution. This term is capitalised throughout the paper.

8 Translation of Spanish and German texts are mine. Lisset Coba, ‘Memorias de la Gran Marcha. Política, resistencia y género en la Amazonía ecuatoriana’, ARENAL 28, no. 2 (2021): 597–626, 620.

9 cf. Marisol de la Cadena, ‘Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual Reflections beyond “Politics”’, Cultural Anthropology 25, no. 2: 334–70.

10 Fernando García Serrano, Del Sueño a la Pesadilla: El Movimiento Indígena en Ecuador (Quito: Flacso -Abya Yala, 2021).

11 ICCA Consortium, ‘Territories of Life: 2021 Report’, https://report.territoriesoflife.org/ [accessed April 15, 2022].

12 Kirsten Anker, ‘Law as Forest: Eco-logic, Stories and Spirits in Indigenous Jurisprudence’, Law Text Culture 21 (2017): 191–213; Margaret Davies, EcoLaw: Legality, Life, and the Normativity of Nature (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2022); Cormac Cullinan, Derecho Salvaje. Un Manifiesto por la Justicia de la Tierra (Quito: Huaponi Ediciones-UASB, 2019; Ursula Biemann, ‘The Cosmo-Political Forest: A Theoretical and Aesthetic Discussion of the Video Forest Law’, GeoHumanities 1, no.1 (2015): 157–70.

13 Anker, ‘Law as Forest’, 198.

14 Michael Uzendoski, ‘Beyond Orality: Textuality, Territoriality, and Ontology among Amazonian People’, HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2, no. 1 (2012): 55–80.

15 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, Declaration Kawsak Sacha-The Living Forest (Sarayaku, 2018).

16 Christine Black, The Land is the Source of the Law (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011).

17 Please note that in the Kichwa language, and in this case, Runa denotes the Kichwa People of Sarayaku. It is worth mentioning that in Kichwa, some plural forms are adopted from Spanish, such as Runas, Kurakas, mukawas, wasis, warmis, and so on. Additionally, the Kichwa names are used exactly as they appear in legal documents created by the Kichwa People of Sarayaku.

18 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, Territorios de Vida Kawsak Sacha – Selva Viviente, (Sarayaku, 2022).

19 I am adapting this term from Alessandro Pelizzon, ‘Earth Laws, Rights of Nature and Legal Pluralism’, in Wild Law- In Practice, eds. Michelle Maloney and Peter Burdon (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2014), 176–89, 177.

20 Jenny García Ruales, ‘Encuentros (Horizontales) con el Mundo Humano y Vegetal en el Jatun Kawsak Sisa Ñampi’, in Producción de Conocimientos en Tiempos de Crisis: Dialogando desde la Horizontalidad, eds. Olaf Kaltmeier and Sarah Corona (Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara-Calas, 2022), 15.

21 Eduardo Kohn, Cómo Piensan los Bosques: Hacia una Antropología más allá de lo Humano (Quito: Abya Yala, 2021). I am using this version because it has a prologue in which Kohn elaborates on RoN and Kawsak Sacha.

22 I am adopting the expression of ‘Rhythms of Law’ and adapting to Kawsak Sacha law from Kate Wright, ‘Rhythms of Law: Aboriginal Jurisprudence and the Anthropocene’, Law and Critique 31, no. 3 (2020): 293–308.

23 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

24 Eben Kirksey and Sophie Chao, ‘Introduction. Who benefits from Multispecies Justice?’, in The Promise of Multispecies Justice, eds. Sophie Chao, Karin Bolender, and Eben Kirksey (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), 1–22, 6.

25 Erin Fitz-Henry, ‘Multi-species Justice: A View from the Rights of Nature Movement’, Environmental Politics, no. 31 (2022): 338–59, 343.

26 Pelizzon, ‘Earth Laws, Rights of Nature and Legal Pluralism’, 186–7.

27 Orlando Aragón Andrade, ‘El Trabajo de Coteorización en la Antropología Jurídica Militante’.

28 Jenny García Ruales and Yaku Viteri Gualinga, ‘A Well-braided (Knowledge) Braid: Lessons learned from the Kawsak Sacha and the Forest Beings to Europe’, in Rights of Nature in Europe: Encounters and Visions, eds. by Jenny García Ruales, Katarina Hovden, Helen Kopnina, Colin Robertson, and Hendrik Shoukens (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2024), 27–44.

29 On the concept of cosmopolitics, see Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics I (Minneapolis, M.N.: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

30 Boaventura De Sousa Santos, ‘Law: A Map of Misreading. Toward a Postmodern Conception of Law’, Journal of Law and Society 14, no. 3 (1987): 279–302. Hereby I acknowledge the misconduct of the scholar and the harassment situation.

31 Asier Martínez de Bringas, ‘Selva Viviente: El Corazón de la Autonomía Kichwa en Sarayaku’, REAF-JSG, no. 34 (2021): 85–111.

32 Maria Cecilia Oliveira and Michael Riegner, Documentary Jatun Yaku- Amazon of Rights, 2021.

33 Adriana Rodríguez Caguana and Viviana Morales Naranjo, Los Derechos de la Naturaleza Desde una Perspectiva Intercultural en las Altas Cortes de Ecuador, la India y Colombia. Hacia la Búsqueda de una Justicia Ecocéntrica (Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar-Huaponi Ediciones, 2022), 21.

34 For an overview, see The Eco Jurisprudence Monitor: https://ecojurisprudence.org/ [accessed April 11, 2024].

35 Jenny García Ruales, Katarina Hovden, Helen Kopnina, Colin Robertson and Hendrik Shoukens, Rights of Nature in Europe: Encounters and Visions (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2024).

36 María José Narváez Álvarez and Jhoel Escudero Soliz, ‘Los Derechos de la Naturaleza en los Tribunales Ecuatorianos’, Iuris Dictio, no. 27 (2021): 69–84, 83. doi:10.18272/iu.v27i27.2121.

37 Erin O’Donnell et al., ‘Stop Burying the Lede: The Essential Role of Indigenous Law(s) in Creating Rights of Nature’, Transnational Environmental Law 9, no. 3 (2020): 403–27. doi:10.1017/S2047102520000242.

38 Virginia Marshall, ‘Removing the Veil from the ‘Rights of Nature’: The Dichotomy between First Nations Customary Rights and Environmental Legal Personhood’, Australian Feminist Law Journal 45, no. 2 (2019): 233–48. doi:10.1080/13200968.2019.1802154.

39 cf. Keebet von Benda-Beckmann and Bertram Turner, ‘Anthropological Roots of Global Legal Pluralism’, in The Oxford Handbook of Global Legal Pluralism, ed. by Paul Schiff Berman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 65–142.

40 Catherine Walsh, Interculturalidad, Estado, Sociedad, Luchas (De)coloniales de Nuestra Época (Quito: Abya Yala-UASB, 2009).

41 CONAIE, Propuesta de la CONAIE Frente a la Asamblea Constituyente: Principios y Lineamientos para la Nueva Constitución del Ecuador. Por un Estado Plurinacional, Unitario, Soberano, Incluyente, Equitativo y Laico (Quito: CONAIE, 2007).

42 Rodríguez Caguana and Morales Naranjo, ‘Los Derechos de la Naturaleza Desde una Perspectiva Intercultural’, 32.

43 Andreas Gutmann, Hybride Rechtssubjektivität (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2021), 204.

44 Rodríguez Caguana and Morales Naranjo, ‘Los Derechos de la Naturaleza Desde una Perspectiva Intercultural’.

45 Juan José Guzman, ‘Decolonizing Law and Expanding Human Rights: Indigenous Conceptions and the Rights of Nature in Ecuador’, Deusto Journal of Human Rights, no. 4 (2019): 59–86, 60.

46 Carolina Valladares and Rutgerd Boelens, ‘Extractivism and the Rights of Nature: Governmentality, ‘Convenient Communities’ and Epistemic Pacts in Ecuador’, Environmental Politics 26, no. 6 (2017): 1015–34, 1027.

47 Gutmann, ‘Hybride Rechtssubjektivität’, 34.

48 Helen Dancer, ‘Harmony with Nature: Towards a New Deep Legal Pluralism’, The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 53, no. 1 (2020): 1–21.

49 Rickard Lalander, ‘Rights of Nature and the Indigenous Peoples in Bolivia and Ecuador: A Straitjacket for Progressive Development Politics?’, Revista Iberoamericana de Estudios de Desarrollo 3, no. 2 (2014): 148–73.

50 ‘All law and every constitution is contradictory’, Gutmann, ‘Hybride Rechtssubjektivität’, 18.

51 Craig Kauffman and Pamela Martin, ‘Can Rights of Nature Make Development More Sustainable?’, World Development 92 (2017): 130–42, 134.

52 Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, 10th November 2021, File Number: 1149-19-JP/21 – Los Cedros; 15th December 2021, File Number: 1185-20-JP – Río Aquepi; 19th January 2022, File Number: 2167-21-EP/22 – Río Monjas; 27th January 2022, File Number: 253-20-JH/22 – Mona Estrellita.

53 Louis Kotzé and Paola Villavicencio Calzadilla, ‘Somewhere between Rhetoric and Reality: Environmental Constitutionalism and the Rights of Nature in Ecuador’, Transnational Environmental Law 6, no. 3 (2017): 401–33.

54 Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, 10th November 2021, File Number: 1149-19-JP/21 – Los Cedros; Court, 19th January 2022, File Number: 2167-21-EP/22 – Río Monjas.

55 Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, February 2023, Guía de Jurisprudencia Constitucional – Derechos de la Naturaleza, 30.

56 Ibid, 99.

57 Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, 27th January 2022, File Number 273-19-JP –A’I Cofán de Sinangoe.

58 Mary Whittenmore, ‘The Problem of Enforcing Nature’ s Rights under Ecuador’s Constitution: Why the 2008 Environmental Amendments Have No Bite’, Washington International Law Journal 20, no. 3 (2011): 659–91, 670.

59 Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, 1st of July 2020, File Number: 20-12-IN/20 –Triángulo de Cuembí, paragraph 128.

60 See, Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, 27th January 2022, File Number: 253-20-JH/22 – Mona Estrellita.

61 Roberto Narváez Collaguazo, ‘La Justicia en un Estado Plurinacional con Garantismo Penal: interculturalidad en ciernes,’ Revista de Derecho FORO, no. 34 (2020): 124–45.

62 Kirsten Anker, ‘Ecological Jurisprudence and Indigenous Relational Ontologies: Beyond the “Ecological Indian”’, in From Environmental to Ecological Law, eds. Kirsten Anker et al. (London: Routledge, 2020), 68–85.

63 Ramiro Ávila Santamaría, ‘Las Lecciones del Incansable Pueblo Sarayaku’, available at: https://gk.city/2022/08/22/lecciones-incansable-pueblo-sarayaku/ [accessed April 3, 2023].

64 Leonidas Oikonomakis, ‘We Protect the Forest Beings, and the Forest Beings Protect us: Cultural Resistance in the Ecuadorian Amazonia’, Anthropological Notebooks 26, no. 1 (2020): 129–46, 140.

65 Eduardo Kohn, Cómo Piensan los Bosques, XIX.

66 Andrea Sempértegui, ‘La Selva Viviente como Selva Política: Prácticas de Hacer-Selva en la Lucha de las Mujeres Amazónicas en Ecuador’, Revista Antropologías del Sur 9, no.17 (2022):147–67, 147.

67 O’Donnell et al., ‘Stop Burying the Lede’, 411; Pelizzon, ‘Earth Laws, Rights of Nature and Legal Pluralism’, 185.

68 cf. Rachel Sieder, ‘Legal Pluralism and Fragmented Sovereignties: Legality and Illegality in Latin America’, in Routledge Handbook of Law and Society in Latin America, eds. Rachel Sieder, Karina Ansolabehere and Tatiana Alfonso (London: Routledge, 2019), 51–65, 60.

69 Lieselotte Viaene, ‘Indigenous Water Ontologies, Hydro-Development and the Human/More-Than-Human Right to Water: A Call for Critical Engagement with Plurilegal Water Realities’, Water 13, no. 12 (2021), 1–22, 19.

70 Sieder, ‘Legal Pluralism and Fragmented Sovereignties’, 56.

71 Brian Tamanaha, ‘Understanding Legal Pluralism: Past to Present, Local to Global’, Sydney Law Review 30, no. 3 (2008): 375–411.

72 Sally Merry, ‘Legal Pluralism’, Law & Society Review 22, no. 5 (1988): 869–96, 878.

73 von Benda-Beckmann and Turner, ‘Anthropological Roots of Global Legal Pluralism’.

74 Sieder, ‘Legal Pluralism and Fragmented Sovereignties’, 53.

75 Ramiro Ávila Santamaría, El Neoconstitucionalismo Transformador: el Estado y el Derecho en la Constitución de 2008 (Quito: AbyaYala -UASB, 2011), 146.

76 Agustín Grijalva Jiménez, Constitucionalismo en Ecuador (Quito: Corte Constitucional para el Período de Transición, 2011), 95. See also Art. 344, Código Orgánico de la Función Judicial.

This legal pluralism encompasses a range of structures, forms of justice and ancestral traditions. While these legal systems can be applied in many scenarios, exceptions arise when they contradict the CRE and human rights (Art. 171).

77 Rodríguez Caguana and Morales Naranjo, ‘Los Derechos de la Naturaleza Desde una Perspectiva Intercultural’, 34.

78 Nicole Graham, Lawscape (New York: Routledge, 2011).

79 Cullinan, ‘Derecho Salvaje’, 24.

80 Davies, ‘EcoLaw’, 2–11.

81 Danielle Celermajer et al. ‘Multispecies Justice: theories, challenges, and a research agenda for environmental politics’, Environmental Politics 30, no. 1–2 (2021): 119–40, 126.

82 von Benda-Beckmann and Turner, ‘Anthropological Roots of Global Legal Pluralism’.

83 Irene Watson, Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law (London: Routledge, 2015), 29–30.

84 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

85 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘El Libro de la Vida de Sarayaku para Defender Nuestro Futuro’, 79.

86 cf. Kathleen Birrell and Daniel Matthews, ‘Re-storying Laws for the Anthropocene: Rights, Obligations and an Ethics of Encounter’, Law and Critique 31, no. 3 (2020): 275–92.

87 cf. Martuwarra RiverOfLife, et al. ‘Yoongoorrookoo’, Griffith Law Review 30, no. 3 (2021): 505–29 doi:10.1080/10383441.2021.1996882.

88 von Benda-Beckmann and Turner, ‘Anthropological Roots of Global Legal Pluralism’, 18.

89 Louis Kotzé and Rakhyun Kim, ‘Earth System Law: The Juridical Dimensions of Earth System Governance’, Earth System Governance 1 (2019): 1–11, 3.

90 Franz von Benda-Beckmann and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann, ‘The Dynamics of Chance and Continuity in Plural Legal Orders’, Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 38, no. 53–54 (2006): 1–44.

91 Davies, ‘EcoLaw’.

92 Boaventura, De Sousa Santos, ‘Law: A Map of Misreading’.

93 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, Estatutos (Sarayaku, 2021).

94 In this article, I am referring to the 2011 version of the Plan de Vida by the Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku (Sarayaku, 2011).

95 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, Normativas de Convivencia (Sarayaku, 2013).

96 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

97 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, Ley Propia: el ejercicio de la Libre Determinación en aplicación del derecho al Consentimiento Previo, Libre e Informado del Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku (Sarayaku, 2022).

98 IACtHR– Kichwa Indigenous People of Sarayaku v. Ecuador.

99 cf. Arturo Escobar, ‘Sentipensar con la Tierra: Las luchas Territoriales y la Dimensión Ontológica de las Epistemologías del Sur’, Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana 11, no. 1 (2016): 11–32, 17.

100 Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, ‘Perspectival Anthropology and the Method of Controlled Equivocation’, Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 2, no. 1 (2004): 3–22.

101 De Sousa Santos, ‘Law: A Map of Misreading’.

102 The declaration has four different versions in various contexts and strategies, all with the participation of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku: the first as part of the life plan (2011), the second one in 2013 by the Mujeres Amazónicas del Centro Sur, the one from Pakkiru, the Kichwa political umbrella Nationality (2018) and the one of Sarayaku (2018). The one I mainly focus on in this article is the latter, the official and actual one from 2018.

103 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Plan de Vida’.

104 Mujeres Amazónicas del Centro Sur, Declaratoria del Kawsak Sacha (Puyo, 2013).

105 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

106 Pakkiru, Declaración Kawsak Sacha – Selva Viviente (Puyo, 2018).

107 José Antonio Marina, ‘Prólogo’ in Aina S. Erice, La Invención del Reino Vegetal: Historias sobre Plantas y La Inteligencia Humana (Barcelona: Ariel, 2020), 19.

108 Lisset Coba and Manuel Bayón, ‘Kawsak Sacha: La Organización de las Mujeres y la Traducción Política de la Selva Amazónica en el Ecuador’, in Cuerpos, Territorios y Feminismos, eds. Delmy Cruz and Manuel Bayón (Quito: Abya Yala, 2020), 141–60, 156.

109 Ancestral knowledge is not included in Amazonian environmental protection schemes from the state, see Pablo Ortiz, Planificación y Autogestión Territorial de los Kichwa de Pastaza en Ecuador. Sumak Kawsay y Autodeterminación en la Amazonía (Copenhagen: IWGIA, 2021).

110 Mario Blaser, ‘Reflexiones Sobre la Ontología Política de los Conflictos Medioambientales’, América Crítica 3, no. 2 (2019): 63–79, 69.

111 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

112 Oliveira and Riegner, Jatun Yaku – Amazon of Rights.

113 Kohn, ‘Cómo Piensan los Bosques’.

114 Michael Dove, ‘Indigenous People and Environmental Politics’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 35 (2006): 191–208.

115 Narváez Álvarez and Escudero Soliz, ‘Los Derechos de la Naturaleza en los Tribunales Ecuatorianos’, 76.

116 cf. von Benda-Beckmann and Turner, ‘Anthropological Roots of Global Legal Pluralism’, 92.

117 For another vegetal reading of law in the Amazon, see Iván Darío Vargas Roncancio, Law, Humans and Plants in the Andes-Amazon: The Lawness of Life (Routledge: Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 2024).

118 cf. Pedro Alvarado et al., Sabiduría de la Cultura Kichwa de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana (Cuenca: Universidad de Cuenca, 2012), 390.

119 Mario Blaser, ‘Political Ontology: Cultural Studies without ‘Cultures’?’, Cultural Studies 23, no. 5–6 (2009): 873–96, 879.

120 Marisol de la Cadena, ‘Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes’, 365.

121 Mario Melo, Caso Pueblo Indígena Kichwa de Sarayaku Vs. Ecuador: Caso No. 12.465 (CEJIL, 2009), 92.

122 Rommel Lara et al., Sarayaku: El Pueblo Del Cenit. Identidad y Construcción Étnica (Quito: Flacso, 2005), 47.

123 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

124 Anders Sirén, ‘Natural Resources in Indigenous Peoples' Land in Amazonia: A Tragedy of the Commons?’, The International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 13, no. 5 (2006): 363–74, 369.

125 Alvarado et al., ‘Sabiduría de la Cultura Kichwa’, 170–1.

126 Anders Sirén, ‘History of natural resource use and environmental impacts in an interfluvial upland forest area in western Amazonia’, Fennia 192, no. 5 (2014): 36–54, 46.

127 Sirén, ‘Natural Resources in Indigenous Peoples' Land in Amazonia’, 372.

128 Mariana Monteiro de Matos, Indigenous Land Rights in the Inter-American System (Leiden: Brill, 2020), 189.

129 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

130 Fernando Santos-Granero, ‘Amerindian Political Economies of Life’, HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 9, no. 2 (2019): 461–82.

131 Anders Sirén, ‘Festival Hunting by the Kichwa People in the Ecuadorian Amazon’, Society of Ethnobiology 32, no. 1 (2012): 30–50, 34.

132 ICCA Consortium, ‘Territories of Life: 2021 Report’, https://report.territoriesoflife.org/ [accessed April 15, 2022].

133 Sirén, ‘Natural Resources in Indigenous Peoples’ Land in Amazonia’.

134 cf. Arturo Escobar, ‘Sentipensar con la Tierra’, 17.

135 Sieder, ‘Legal Pluralism and Fragmented Sovereignties’, 60.

136 cf. Coba and Bayón, ‘Kawsak Sacha’.

137 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Acuerdo Global de Sarayaku’, 27 July 2022, available at: https://sarayaku.org/acuerdo-global-sarayaku/ [accessed April 3, 2023].

138 Jenny García Ruales, ‘Kawsari: Kawsak Sachamanda Rimanakuy’, in Derechos de la Naturaleza y Territorio en Ecuador. Diálogos desde los Saberes y Quehaceres Jurídicos y Antropológicos, eds. Rommel Lara, Jenny García Ruales and Alex Valle (Quito: Abya Yala-UPS, 2024) 59-82.

139 Sian Lazar, ‘Anthropology and the Politics of Alterity: A Latin American Dialectic and its Relevance for Ontological Anthropologies’, Anthropological Theory 22, no. 2 (2021): 131–53, 145.

140 Pueblo Originario Kichwa de Sarayaku, ‘Declaration Kawsak Sacha’.

141 Michael Cepek, ‘There Might Be Blood: Oil, Humility, and the Cosmopolitics of a Cofán Petro-Being’, American Ethnologist 43, no. 4 (2016): 623–35.

142 cf. Kohn, ‘Cómo Piensan los Bosques’, XXVII.

143 Mihnea Tănăsescu, ‘Rights of Nature, Legal Personality, and Indigenous Philosophies’, Transnational Environmental Law 9, no. 3 (2019): 429–53, 452.