ABSTRACT

Armed conflict has tragically become commonplace in the lives of many children. Children do not only witness conflict violence and are subjected to it, but are also sometimes forced to perpetrate violence themselves. Recently, scholars from different fields have examined these experiences. However, few scholars have considered the experiences of girls or have compared these experiences to those of boys. This is surprising given the increased focus of the international community on the protection of girls. This exploratory study is an attempt to overcome this by examining the experiences of boys and girls during conflict and whether these gendered experiences have influenced social relationships in the aftermath of war. Empirically, we rely on 315 structured interviews with Congolese boys and girls. Some of these children were actively involved in armed groups in the Eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Our descriptive analysis shows remarkable differences between boys and girls. This work has important consequences for the study of the effect of conflict on children, the role of girls during and after conflict, and the international policy community.

Introduction

Tragically, violence and armed conflict have become commonplace in the lives of many children around the world.Footnote1 Tragically, violence and armed conflict have become commonplace in the lives of many children around the world. Not only have millions of children been forced to witness war and its atrocities, but many are drawn into conflict as active participants. Although exact numbers are lacking, it is recently estimated that one in six children worldwide lives in a conflict zone.Footnote2 Not only have millions of children been forced to witness war and its atrocities, but many are drawn into conflict as child soldiers.Footnote3 They are used as soldiers not only by non-state but also by state armies.Footnote4 Moreover, in some cases such as the genocide in Rwanda, violence is even specifically aimed at children: ‘To kill the big rats, you have to kill the little rats.’Footnote5

Increasingly, scholars from diverse disciplines have begun to analyse the effect of armed conflict on children, their families, and society at large.Footnote6 Human rights scholars, for instance, have examined how children’s rights have evolved over the years.Footnote7 Psychologists have made massive strides in understanding how armed conflict might cause mental and behavioural changes in children.Footnote8 Economists have focused on examining the income-earning capabilities of war-affected children and school attainment.Footnote9 Others have examined the long-term effects of armed conflict on the (political) attitudes of these children.Footnote10

Despite the broad ecological impact of war on children, few scholars have differentiated between the experiences and consequences of armed conflict for boys and girls. The role of gender has, however, been examined by those working on gender in international relations theory and those who work on the topic of girl soldiers.Footnote11 Notwithstanding, it often remains unclear how the experiences of girl soldiers differ from those girls that were not involved in armed groups, but also how it differs from the experiences of boys as well as boy soldiers.Footnote12 Moreover, existing research that has accounted for possible gendered experiences has been primarily focused on a child’s time in the armed group, thereby largely ignoring possible post-conflict differences.Footnote13

This lack of comparative research is surprising since scholars and the policy community have emphasised the fact that the experiences of girls during conflict are fundamentally different than those of boys.Footnote14 For instance, some human rights scholars have highlighted the need for a gendered security lens.Footnote15 Others have emphasised that children often have not participated in the establishment and implementation of child protective rights and that current measures often overlook the diverse experiences of children.Footnote16

This exploratory descriptive study attempts to overcome some of these problems by investigating the potential differences between boys and girls. To do so, we draw upon 315 structured interviews conducted with boys and girls in the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Some of these children were actively involved in the conflict as soldiers, while others were less exposed. Our analysis starts with systematically exploring what these boys and girls have experienced during conflict. Thereafter, we associate these gendered experiences with differences in social behaviour. That is, we examine whether these gendered conflict experiences are associated with differences in their relationship with their family, friends (and other social groups), and their relationship with teachers. Important to note is that we do not offer a causal framework explaining how conflict exposure might cause changes in social attitudes. Instead, we link our results to existing literature that explains these psychological processes in more detail. The potential differences identified in this study should then also become the basis for future empirical and theoretical work.

This study proceeds as follows: After reviewing existing literature on how children experience armed conflict and its consequences and emphasising the need for a more gendered analysis, we present the information collected in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). As this is largely an exploratory study, significant attention will be devoted to the discussion of the limitations of the data but also avenues for future research. We conclude with a brief discussion of the results and some policy implications.

An interdisciplinary focus: the effect of armed conflict on children

Children can experience armed conflict in different ways.Footnote17 Some become active participants and perpetrate violence. Many others become the subject of violence or witness violence. They live in areas from which parents, friends, and relatives are sent into battle, and may suffer from the consequences of school closure, economic hardships, and forced migration. The acknowledgment of these diverse experiences has resulted in a growing interdisciplinary literature that analyses the consequences of armed conflict for these children, families, and societies at large.

Human rights and legal scholars have, for instance, paid significant attention to the development and implementation of international law concerning the protection of children and child soldiers in particular.Footnote18 They show that significant progress has been made in developing a legal framework starting with the Geneva Convention to the adoption of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict and the adoption of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.Footnote19 These protocols and other legal instruments are, however, not uncontested. Some scholars have argued that children’s rights reflect primarily Western-based concepts of childhood superimposed onto a universal platform.Footnote20 Other human rights scholars have argued in favour of stricter protection measures for child soldiers and have emphasised that the existing legal framework needs to be reinterpreted.Footnote21 Additionally, some have argued that although the legal framework might have contributed to establishing norms and sponsoring important legislation and aid programs, they often neglect to include children’s and young people’s views.Footnote22 Collins,Footnote23 for instance, has argued that the relationship between agency and the vulnerability of children must be respected in international child protection efforts. Additionally, these protection efforts need to pay attention to and recognise their diversities.Footnote24 The tendency to homogenise children’s experiences, whereby children become only one category, directly goes against the rights of the child.Footnote25

Psychologists, on the other hand, have been focused on examining the (mental) health and behavioural consequences of war exposure. The resulting evidence has revealed a dark picture. For instance, Hermenau et al.Footnote26 show that growing up in a conflict area can lead to severe trauma and aggression among children. Moreover, children who have experienced and perpetrated violence during conflict are the ones that are most likely to suffer from trauma-related syndromes.Footnote27 Dyregrov, Gjestad & RaundalenFootnote28 have shown that exposure to war decreases happiness among children: they are in constant fear of losing their home and family members. In addition, they show that war exposure can lead to distress, anxiety, and depression, especially among older children.Footnote29

War exposure also significantly influences how these children interact with each other and others. For instance, in Uganda, Bauer et al. compared the behaviour of former Lord’s Resistance Army soldiers with their non-abducted peers.Footnote30 Their research shows that former child soldiers exhibit more trustworthy behaviour in comparison to those who were not involved with the Lord’s Resistance Army, especially if they were abducted at an early age.Footnote31 In addition, Blattman shows that child soldiering can increase political engagement; boys who had been abducted and forced into joining rebel forces are more likely to vote and participate in local community action later on in life.Footnote32 A more negative effect is found by Humphreys & Weinstein who demonstrate that past participation in Sierra Leonean abusive military fractions makes post-conflict reintegration in society harder.Footnote33

Other scholars have examined the impact of war on schooling and labour outcomes. Examining the effects of Uganda’s civil war, Blattman & Annan find that boys who were recruited into armed groups received less schooling, were less likely to have a skilled job and earned lower wages.Footnote34 Shemyakina finds that adolescent Tajik girls whose homes were destroyed during the civil war are less likely to obtain secondary education and that this affects their wages.Footnote35 Additionally, Chambarbawala & Moran find a strong negative impact of the Guatemalan civil war on education, reinforcing the idea that armed conflict strengthens poverty and social exclusion among the most vulnerable populations.Footnote36

While significant progress has been made in different disciplines on how armed conflict affects children, their families, and societies at large, the literature tends to reflect universalism and assumptions that generalise children as if they are identical across time and space.Footnote37 Most importantly, comparatively little attention has been given to possible gendered differences. Two important strands in the literature form an exception. First, several scholars have started working on the issue of gender, conflict, and international relations theory.Footnote38 These scholars show that gender influences the decisions of all actors involved. For example, Cynthia Enloe argues that we need to examine conflict from the ground up rather than simply focusing on the international.Footnote39 More specifically, she argues that the relationship between the international and the personal has often been overlooked and that to understand the militarisation of politics and society, we need to consider how women’s lives shape and are shaped by the everyday interactions between the military and the community. Her work has inspired many important feminist accounts. For instance, Carpenter shows that gender influences how the laws of war are implemented and promoted in international society, ultimately undermining the principle of civilian immunity.Footnote40 Saywell, on the other hand, describes the role of women in conflict more broadly and shows how diffuse and uncertain definitions of male and female roles become during war.Footnote41 This is discussed in more theoretical terms by Cockburn.Footnote42 She shows that before, during, and after wars important transformations occur in patriarchal ideology. Relatedly, Rehn and Sirleaf show in their impressive study how conflict affects women and women’s role in peacebuilding.Footnote43 For instance, they show that despite the enormous magnitude of violence suffered by women before, during, and after conflict, they still have the least access to protection and assistance provided by the state or international organisations.

Second and most closely related to this study are those scholars working on the recruitment of girls by armed groups.Footnote44 One of the very first studies on girl soldiers was conducted by Mazurana et al., who used descriptive data to identify girls’ involvement and roles in armed groups.Footnote45 Mckay & Mazurana focus on the context of Uganda, Sierra Leone, and Mozambique and describe the experience of girls in the fighting forces within these countries.Footnote46 These studies and their consequences are further explored by Denov (2008) and can also be found in some biographical accounts.Footnote47 Also, Wessells examines the recruitment of girls in the conflict of Angola, arguing that their recruitment was neither incidental nor driven by convenience but is solely owed to commanders’ desire to use them as resources needed to fight effectively.Footnote48

These studies have significantly increased our understanding of the experiences of girl soldiers during armed conflict. Yet, they suffer from several important drawbacks that limit our understanding of how exposure to armed conflict might be different for boys than for girls. First, the goal of most of these studies is to describe the experiences of girl soldiers. In doing so, few studies establish a counterfactual to the experience of these girls, such as boy soldiers or girls not involved in armed groups, and so struggle to isolate gender effects. Moreover, most studies on girl soldiers are qualitative and based on a limited number of observations. A low number of observations increases the potential for bias and reduces the possibility of generalizability. Second, most work on the experience of girl soldiers has focused on describing the role of girls within the armed groups but ignores potential differences between boys and girls after conflict. The study of Annan et al.Footnote49 is an important exception, in which it is shown that armed conflict impacts especially the economic situation of many former boy soldiers in comparison to girl soldiers. However, their study is less focused on how conflict might affect social relationships.

Given these understandable drawbacks, we are currently very limited in what we can say about the gendered experiences of armed conflict. That is, whether girls’ experiences are different than those of boys. As a result, it is difficult to include the diverse experiences of conflict-affected children in many child protective programs and legal frameworks.Footnote50

Exploring gendered experiences

Conflict exposure can affect a range of post-conflict experiences. However, in this study, we primarily focus on how it might influence post-conflict social relationships. In doing so, we focus on three post-conflict relationships that are considered to be crucial for a child’s development and well-being: family-child relationships, friendships, and teacher-pupil relationships.Footnote51 It is especially these social relationships that can provide children with the assurance of receiving help when needed and feedback about their behaviour, as well as to validate and share their feelings and experiences with others.

First, the experience of armed conflict can significantly influence the relationship between children and their families or caretakers. Death of family members and separation from home and community can seriously impact the family-child relationship.Footnote52 Even if families remain intact during armed conflict, the relationship can become strained. Not only does armed conflict interfere with the performance of basic family tasks of providing safety and security,Footnote53 but both children and their family/caretakers may suffer from the psychological and behavioural effects of war exposure which can constrain their relationships. For instance, some studies have shown that war exposure often increases frustration, demanding behaviour, attention-seeking, aggressiveness, and temper tantrums.Footnote54 Other studies have shown that children, parents, and caretakers can become psychologically inaccessible due to their experiences in conflict,Footnote55 which can disrupt traditional authority relations between generations.Footnote56

While familial relationships can suffer from the consequences of war exposure, these relationships can also be extremely important in moderating the potential negative effects of armed conflict.Footnote57 Parental compassion and warmth have been found to reduce emotional stress,Footnote58 and the propensity for dangerous behaviour,Footnote59 and promote healthy psychosocial development.Footnote60 Given these positive effects, it is not surprising that many disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) programs for former child soldiers strongly emphasise the importance of family reunification and acceptance.Footnote61 The few existing studies on this family effect show some potential gendered differences. For instance, Betancourt et al.’s study in Sierra Leone shows that former girl soldiers saw greater family acceptance over time, whereas their male counterparts perceived diminished acceptance.Footnote62 Quota, Punamäki, and El Saeeaj, examining war exposure in more general terms, show that it especially negatively affected the relationship between Palestinian parents and their sons.Footnote63

Second, friendships and belonging to social groups are extremely important for a child’s well-being. It contributes to learning communication and how to express and regulate emotions. Moreover, children learn mutual trust, fairness, empathy, loyalty, and responsibility.Footnote64 Consequently, the ability to make and maintain friendships is associated with good mental health and optimal development.Footnote65 Being exposed to armed conflict, however, can impact the quantity and quality of these social relationships. There is reason to believe that it can have a positive as well as a negative impact.Footnote66 On the one hand, children might be very preoccupied with family safety, which can disturb the maintenance of friendships and other social relations, resulting in isolation.Footnote67 Exposure to violent events can also result in mental and behavioural changes that might interfere with intimate sharing and trust among peers, especially with those who have not had similar experiences. For instance, Peltonen et al.Footnote68 and Paardekopper et al.Footnote69 show that children who witnessed or were themselves targets of military violence had poorer friendships than children who were spared such trauma. On the other hand, some scholar scholars have suggested that war exposure might increase altruism and willingness to share, promoting friendships and closeness to people.Footnote70 For instance, DenovFootnote71 encountered several instances where children sought the comfort, solace, and encouragement of other war-affected children. There is also some reason to believe that there might be some differences between boys and girls in the quality and quantity of post-conflict friendships. According to the traditional view, girls usually have a larger investment in relationships than boys. War exposure might then also have a more deteriorating effect on girls’ friendships.Footnote72 At the same time, some have suggested that boys tend to be more expressive with friends, especially during adolescence.Footnote73

Third, research has shown that armed conflict can have devastating effects on the educational attainment of children.Footnote74 Education, however, supports war-affected children and adolescents in several important ways. Structured rules, regulations, and activities organised by the school establish a sense of normalcy, which is crucial to the healing process and well-being of children.Footnote75 For instance, Loughery et al. found that attending school activities led to improved measures of children’s psychological health.Footnote76 Schools also naturally create support groups for young people outside of their extended families. Support of teachers and peers significantly helps war-affected children to maintain functionality.Footnote77 For instance, a study among Israeli adolescents found that a positive school climate, specifically the level of students’ school connectedness and teacher support, is an important factor in promoting resilience among secondary school students against the effects of armed conflict.Footnote78 There is reason to believe, however, that this positive effect is likely to be more found among girls. Girls seem to have a higher-quality relationship with teachers, which might be partially caused by the fact that they are less exposed to armed conflict.Footnote79

Important to note is that in exploring these potential gendered experiences empirically, we do not offer any causal explanation. Exploring the reasons why we might (or not) see differences across genders and experiences goes beyond the scope of this study. However, after each analysis, we draw attention to some potential future research questions and factors that might explain the observed associations.

Case and data

The Democratic Republic of the Congo

To examine the gendered experiences of children during and after the conflict, we look at the case of the two eastern provinces of the DRC. The origin of the current armed conflict in these two provinces lies in the massive refugee crisis and spillover from the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.Footnote80 After Hutu génocidaires fled to eastern DRC, many armed groups arose. The Congolese government was unable to control and defeat these groups, some of which directly threatened populations in neighbouring countries. As a result, Rwanda and Uganda invaded the eastern DRC in 1996.Footnote81 With the support of these countries, former President Mobutu Sese Seko was ousted, and Congolese opposition leader Laurent Désiré Kabila took control. After taking power, he ordered Rwanda and Uganda to leave the DRC, fearing annexation of the mineral-rich territory by the two countries. This resulted in the so-called Second Congo War, during which Congolese government forces supported by Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe fought rebels backed by Rwanda and Uganda over a period of five years.Footnote82 It is estimated that during this period, around 3 million people have been killed and millions more have been internally displaced.Footnote83 Despite a peace deal in 2002 and the formation of a transitional government in 2003, ongoing violence perpetrated by armed groups against civilians in the eastern region has continued, largely due to poor governance, weak institutions, and rampant corruption. In 2019, Félix Tshisekedi was inaugurated as the president of DRC, taking over the position of Joseph Kabila who was the president of the DRC for 18 years. Tshisekedi has inherited several crises across the country, including ongoing internal violence, with the activities of over a hundred armed groups representing the main threat, despite the presence of United Nations (UN) peacekeepers.

Human rights violations are widespread and continue to occur. The DRC is facing one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters, and children are paying the heaviest price. World Vision has called the situation ‘one of the worst child protection crises in the world’.Footnote84 The latest UN-Secretary General report on Children and Armed Conflict, for example, reported 3,377 verified grave violations against children in the DRC of which about 46% involved the recruitment of children – some as young as five – by armed forces or groups.Footnote85 Boys and girls in the DRC are then also exposed to a vast range of different conflict-related experiences: some have no experience at all, others have witnessed violence and perhaps experienced it themselves, while again others were forced to perpetrate violence while being active in armed groups. As such, the DRC is a good case to examine these experiences in detail, their gendered dimensions, and how they might influence social attitudes.

Methodology

To examine how the armed conflict has affected Congolese boys and girls, systematic data was collected in the period 2018-2019 in the South Kivu province. With the help and consent of five local child protective organisations,Footnote86 315 children and young adolescents were surveyed by a team of experienced social scientists and clinical psychologists. The sample of respondents was identified using the snowball method, a commonly used strategy in face-to-face surveys of very difficult-to-reach populations.Footnote87 The research team first identified child protective organisations active in providing support services in South Kivu. After explaining our research purpose and the questions, informed consent was received from these organisations and the caretakers within these organisations. Each organisation then invited children who engaged with their services to be interviewed. For those children who did not live on these organisations’ premises but were living with family members (few lived with family members), the organisations informed and consulted the parents and asked for permission. Only children between the ages of 12 and 18 were invited (although some younger and older children presented themselves for interviews) and each organisation screened potential respondents to ensure they were physically and mentally able to provide informed consent.

Before each interview, the content, procedure, risks, the right to withdraw, and confidentiality were explained, and informed assent was obtained from each child. All questions were translated from English to Swahili, Kinya-Rwanda, Lingala, or French by translators during the interview as needed. Each child received a small reimbursement, equivalent to around 5 USD, independent of whether they answered the questions or not.

The psychological welfare of respondents was prioritised throughout the survey; interviewers were trained psychologists or social scientists with prior experience interviewing children, former child soldiers, and war-affected people. Due to their experience, they would be able to recognise signs of distress and intervene when necessary. In addition, the translators were also trained in trauma-informed practices. Due to previous research experiences, all interviewers and translators had contacts with mental health providers in the area. Children who would show symptoms of psychological distress during or after the interview could be easily referred to these services when necessary. Moreover, each child protective organisation had its own well-established links to mental health providers and could refer these children in case symptoms appeared weeks or months after the interview. To our knowledge, however, none of the interviewed children experienced these symptoms during the interview or in the weeks after.

During the interview, which was conducted in a private setting, children were asked about their exposure to the armed conflict and issues related to their current situation. Of the 315 children that were interviewed, 199 were boys and 116 were girls. On average, they were 17 years of age during the interview. 186 children were involved in armed groups (76% were abducted), of which 136 were boys and 50 were girls.Footnote88 It is important to note, however, that this does not mean that these former child soldiers were all active as fighters since many children were solely used in support roles, such as carrying goods or cooking. On average, these former child soldiers stayed for more than 2 years in the armed group and very few went through the official DDR programme (15%). Around 23% of the interviewed children lost both parents. More descriptive statistics can be found in the Supplementary Appendix.

Before coming to our descriptive analyses, we must emphasise several caveats regarding our collected data that might impact the results presented below. First, although we have interviewed a relatively large number of children, we are still using a convenience sample as we interviewed those children who were available to us. Second, we worked with local organisations primarily active in the two eastern provinces of the DRC. These two provinces have a historical legacy of conflict in comparison to other provinces. However, it might be the case that different types of conflict might produce different effects on children. Despite these limitations, our sample is defined by significant variation; we have interviewed children of all ages, all genders, and with different levels of exposure to armed conflict.

Analyses

Our analysis of the potential gender differences is divided into two parts. First, we explore the statistically significant differences in war exposure between boys and girls. Second, we examine the gender differences in post-conflict social relationships. In doing so, we focus especially on the child’s relationship with parents and caretakers, friends, and with their teachers. To ease the interpretation, we display the most interesting results in the figures below. In the Supplementary Appendix, additional analysis, tables, and figures can be found.

During conflict

We begin by exploring the extent to which children were exposed to armed conflict. For this, we use Ertle’s et al. exposure scale.Footnote89 This scale consists of 30 questions (Cronbach’s alpha 0.92), asking about whether they have experienced, witnessed, and/or perpetrated specific kinds of violent acts. For instance, children were asked whether they have been close to combat, whether they have witnessed someone getting injured by members of armed groups, whether they have seen dead bodies, and whether they were forced to kill someone. This scale has often been used and validated in different contexts (that is different conflicts in different countries) and with different populations (children, adults, former combatants, former child soldiers, and refugees).Footnote90

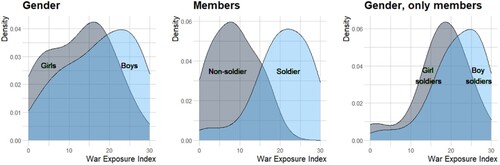

On average, children experienced around 16 of these kinds of events. Most of them indicated to had seen homes and property destroyed (88% of the children) and had witnessed people being beaten or tortured by armed personnel (79% of the children). Fewer indicated that they have been sexually assaulted or raped (21% of the children) or been injured by a weapon, such as being shot, stabbed, or mutilated (33% of the children), although these experiences were not uncommon. shows the distribution of our data via several Kernel Density Plots, which are often used to display the distribution of variables across groups. The curve represents the proportion of the data (in this case the number of children) in each range. The peaks of a Density Plot display where values are concentrated over the interval. For instance, Figure 1.1 shows that most boys were exposed to significantly more events than girls (an average of 17 events for boys and 12 for girls). That is, for almost all events, we find that boys (in contrast to girls) were exposed to them to a higher extent (see also Table A2 in the Appendix). For instance, girls were statistically significantly less often involved in battles, were less often harassed, or beaten by soldiers, and were less often involved in the killing or harming of civilians. One important exception is that girls are significantly more often indicated to have been sexually assaulted or raped.

Figure 1.2 shows that – unsurprisingly – former members of armed groups were exposed to more events than those who were not members of an armed group (around 20 events in contrast to 9 events). Only very few former child soldiers were exposed to less than 10 events (the density score is very close to 0). Within the armed group, there are also stark differences; boy soldiers were statistically more exposed than girl soldiers (see Figure 1.3). For instance, they indicated more often that they had seen mutilated people and dead bodies and that they witnessed people getting shot or stabbed by armed personnel. The difference in war exposure is primarily caused by the fact that boy soldiers were significantly more involved in perpetrating violence than girl soldiers. No significant differences, however, could be detected when examining witnessing violence or experiencing violence (see Table A3 in the Appendix).

After conflict

Family-child relationships

To explore the link between gender, war exposure, and its relationship with family, we adapted the Social Capital Questionnaire for Adolescent Students (SCQ-AS) developed by Paiva et al.Footnote91 We asked the children to react to 8 statements, such as ‘I feel safe at home,’ ‘I talk to my parents/caretakers when I am having a problem,’ ‘I can count on my parents/caretakers to help me when I have a problem,’ ‘I trust my caretakers/parents.’ Children could indicate to what extent they agreed or disagreed with it. We combined these answers in a Family index (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.87) ranging from 8 (indicating that the child experienced problems) to 40 (indicating a positive relationship).

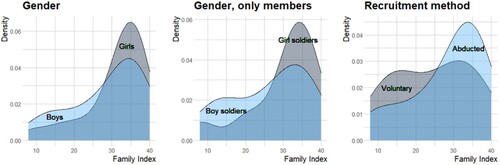

shows the Kernel Density Plots of some important statistically significant associations. Additional figures and tables can be found in the Supplementary Appendix (see Table A4 and Figure A2). First, the results show that girls have a significantly stronger relationship with their family and caretakers than boys. This is in line with some existing research suggesting that boys experience particularly acute problems with family.Footnote92 This gender difference is also observed when comparing former boy and girl soldiers (Figure 2.1); former girl soldiers have a significantly higher score than former boy soldiers, indicating a more general positive relationship with parents or caretakers.

Second, we also found that high levels of war exposure (defined as above-average scores on the War Exposure index) significantly influence the relationship between family/caretakers and children (see Figure A2 in the appendix). Those children who were exposed to armed conflict to a greater extent experienced more problems than those who had only limited exposure. This pattern also holds for former child soldiers who more actively participated in the conflict. Together, these findings confirm the relationship described by Annan et al. who found in Uganda that the amount of perpetrated violence was associated with higher levels of ever having family and community problems.Footnote93

Further, there is an interesting association was the one between the method by which children were recruited and their family context. Figure 2.3 shows that children who were abducted into an armed group have significantly higher family index scores than those who joined an armed group voluntarily. This association suggests that the choice to join has damaged their relationships with family.Footnote94

Although these statistical associations give some indication of the gendered effect of war exposure, future research should explore it in more depth. For instance, we do not offer any causal reasoning as to why boys might experience more problems than girls. Moreover, our measures do not examine the role of social isolation, discrimination, and community acceptance. Nor do they examine the potential differences between the relationship with parents and other family members or the amount of social support these children receive.

Friendships and social groups

Besides family relationships, children’s interaction with friends and other members of their social group is of importance. We examined the quality of post-conflict friendships and interactions with people in the same social group in two ways. First, focusing solely on former child soldiers, we explored the possible existing bond with fellow members. We examine this in-depth by measuring their so-called level of attachment to the group. For this, we adapted the belongingness measure of Malone, Pillow, and OsmanFootnote95 and asked former members of the armed group to react to 8 statements, such as ‘I feel accepted by people that were never a member of an armed group,’ ‘When I am with other people that were never a member of an armed group, I feel like a stranger’ and ‘Friends and family that were not involved in any armed group do not involve me in their plans.’ Based on their level of agreement, we create an index (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.78) ranging from 0 (feeling strongly connected to the armed group) to 40 (feeling less belongingness to the armed group).

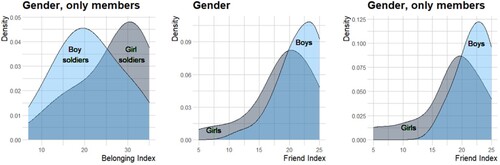

The results, some of which can be found in (left panel) and the rest in the Supplementary Appendix (Figure A3 and Table A4), show that on average, former girl soldiers report higher belonging scores than boys, indicating that they feel less attached to their armed group and feel stronger connections to those outside the group. Those former soldiers who were more exposed to conflict feel that they belong more in the armed group than in wider society. Girls were less exposed to conflict and less likely to perpetrate violence, so it is unclear whether gender directly affects social belonging or if it operates through gendered war exposure. We leave this causal question for future research, but our descriptive evidence indicates that gender and experiences during conflict interact to strongly affect children’s post-conflict reintegration in society.

Second, besides examining the existing bond with their former group, we also examine the diversification of friendship networks, regardless of whether they were former members of an armed group or not. Diversification of friendship networks, as part of bridging social capital (i.e. outward-looking and involves relationships and networks of trust and reciprocity between different groups and communities), is an important indicator of quality and reintegration.Footnote96 A friendship between people with different backgrounds diminishes the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ attitude, brings societies together and increases knowledge, understanding, and tolerance between people.Footnote97 To explore this, we use the validated scale made by Krasny et al.Footnote98 The friend index consists of 5 statements, such as ‘I have close friends who are of other ethnicities than me’ or ‘I have close friends who are all ages, not just my age.’ On each statement, the child could indicate their level of agreement or disagreement. The index (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.65) ranges from 5 (indicating that the child has only friends with similar backgrounds) to 25 (indicating that a child has also friends with different backgrounds). (middle and right panel) and the Supplementary Appendix show the results. It is apparent that boys have statistically significantly more diverse friendship networks than girls, even when comparing former boy soldiers to girl soldiers. Moreover, those who have had a high level of war exposure have a more diverse friendship network.

However, our results stand somewhat in contrast with those arguing that war exposure might negatively affect the quality of friendship.Footnote99 Future research should explore this association in more detail. It might be the case that girls compensate for the loss of friendships by focusing on other social relationships, such as those with family members. In addition, our results suggest that those who have experienced the conflict to a larger extent see value in diversifying their friendship network. It would be interesting to see whether this diversification results in significant behavioural changes, such as less aggression, less attachment to the armed group, and better reintegration effects.

Teacher-pupil and pupil-pupil relationship

Lastly, we explore how gender and war exposure might affect the post-war relationships between the school, teachers, and their pupils. We again made use of the SCQ-AS,Footnote100 which includes specific items on the relationship between teachers and pupils and between pupils. Children were asked to indicate whether they agreed or disagreed with 6 statements, including ‘I feel safe at this school,’ ‘The teachers at my school are sympathetic and give us support,’ and ‘The students at my school are having fun together.’ Based on these answers a scale was created that measured ranging from 5 to 30 (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.66) in which a higher number indicates a more positive relationship between the teachers and pupils and among pupils. Important to note is that from the 315 children interviewed, only 40 percent went to school or received some form of vocational training, such as carpentry, mechanics, or tailoring. In combination with some missing answers, we are only able to compile a school index score for 30% of the children.

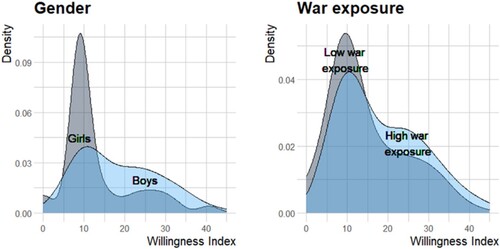

The interviewed children had generally a very positive relationship with their school or training program: they felt safe at their school, they felt as if they belonged to the school, they were having fun with their fellow students, they had the feeling that they could ask for help if needed, they trust their fellow students, and the teachers were seen as helpful and sympathetic. Importantly, there are no statistically significant differences in the school index scores between those children who were active in an armed group and those who were not recruited. Both groups of children have similar positive opinions and experiences. There is also no statistical difference in the scores between girls and boys.

For a closer look at school experiences, we examine differences across responses to each statement (see Table A5 and Figure A4 in the Supplementary Appendix). While responses were relatively uniform across most of the statements, there is an interesting variation in how children perceive their relationships with teachers. Girls are significantly more likely than boys to indicate that teachers are sympathetic and supportive. This gendered difference is even starker when looking exclusively at the responses of members of armed groups; former girl soldiers have significantly higher responses than boy soldiers, signifying strong agreement. Experience in an armed group appears to affect relationships with teachers, but only for girls.

Because of the extremely low response rate on the questions examining the relationship between teachers and pupils (many children simply did not attend school), we are careful in drawing strong conclusions. Although extremely important for the development of a child, not every child that we talked to went to school or received vocational training. Consequently, there are many avenues for future research. Not only do we need more information on factors explaining the teacher-pupil relationships but for the international community it is also important to know what the effect of a positive school environment is on the reintegration of former child soldiers, acceptance in the community, and whether it can help (under which circumstances) children to cope with their experiences.

Conclusion

Attention has increasingly been paid to how armed conflict affects children and young people. Scholars from diverse disciplines have examined, for example, how war exposure might cause attitudinal, mental, and behavioural changes and how it affects schooling and income-earning capabilities.Footnote101 In examining these important negative consequences, scholars have, however, made few attempts to explore potential differences between boys and girls. The few existing studies have been mostly descriptive thereby lacking a comparative perspective. Moreover, they have largely overlooked potential differences in post-conflict social relationships.Footnote102

Our study aims to overcome some of these problems by empirically examining the differences in experiences of 315 boys and girls in the DRC, some of whom were actively involved with different armed groups. The interview data allows us to explore potential differences during conflict (levels of war exposure) and differences after conflict (family-child relationships, friendships, teacher-pupil relationships). The results show that gender is a fundamental, neglected component in the analysis of the effect of armed conflict. Several significant differences are identified that can inspire future research. First, boys have a higher level of war exposure than girls. Even within the armed group, it is former boy soldiers who have experienced a relatively vast array of conflict-related events. Second, in the post-conflict environment, girls have generally a better relationship with their families and with their teachers. However, in contrast, boys and those with more war exposure are more likely to have a diverse friendship network. Lastly, girls are significantly more likely than boys to indicate that teachers are sympathetic and supportive.

Our study is an attempt to explore the gendered effect of armed conflict in more detail. In doing so, we hope to strengthen the nascent literature and envision gender as a core component in its analysis. Consequently, throughout our analyses, we have emphasised potential avenues for future research. We name a few of them. First and foremost, future research should explore each of these identified differences in more detail by exploring causality. To be precise, we have not explored in this study the ‘why’ underlying these differences, and have not sought to pinpoint the exact causal mechanism responsible for these gender differences (although our evidence points to some potential solutions). For instance, we have not explained why girls have a more positive experience in school than boys or the reason why boys have more difficulty with family relationships. These empirical differences might be caused by behavioural changes, psychological trauma, or specific experiences before and during war. It is then also crucial that more research is conducted that can explain this variation in more theoretical and empirical depth.

Second, we consider this study as an exploratory comparative empirical study. However, due to our sample characteristics, the identified gender differences need to be carefully interpreted and confirmed by other cases and analyses. It is likely that children’s experiences within the DRC are fundamentally different than those in other cases, such as in the Ukraine and Palestine. For instance, it might be that the DRC is a case where we see a relatively high number of child soldiers, fewer bombings, and overall a different type of conflict than in other cases. This all might influence children’s experiences and the identified gender differences.

Third, in this study, we have examined the effect of armed conflict via a cross-sectional setup. However, likely, the long-lasting effects of armed conflict on children may not be fully known for years after exposure.Footnote103 We should then also strive as a research community to examine this effect in more longitudinal studies. These types of studies can also give us more insight into factors that can strengthen the resilience of children and adolescents.

Concerning policy implications, our work highlights the fact that children’s experiences with armed conflict are significantly different across genders; it affects boys differently than girls. These differences are important considerations in building appropriate and effective psychosocial support programs. To put it differently, boys and girls might need access to different tools and resources at different periods. Developing and increasing the availability of these gender-responsive approaches and tools might help not only to strengthen the resilience of children after conflict but it might help also to strengthen their agency and resilience before conflict. At the same time, we applaud the current trend of focusing on and improving the position of girls in the international system by the United Nations Security Council. For instance, special DDR programs for girls are important in light of our results. Addressing the differences in needs of boys and girls after conflict will not only improve their situation but is likely to positively affect entire households, post-conflict regions, and post-conflict countries.

Appendix_22042024 file - 2.docx

Download MS Word (633.4 KB)Gendered_effect_war_SUPPLEMENTARY.docx

Download MS Word (840.2 KB)Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the Gerda Henkel Stiftung for their extensive support of this research. We are also grateful to all the children for their readiness to participate and willingness to talk about often intimate and painful subjects. We especially thank Tobias Hecker, Lars Arno Dumke, Charlotte Salem, Justin Maisha, Bahati Muchindi Chancelin, Aline Iragi Malekera, and Nicole Kaboyi, for their assistance with the data collection. Additionally, we want to thank the directors and staff of the following organisation: Le Bureau pour le Volontariat au service de l'Enfance et de la Santé (BVES), Centre d’Apprentissage Professionnel et Artisanal (CAPA), Collectif des Ongs Unies pour le Developpement Durable des Associations Pour L’encadrement Des Personnes Deœuvrees et Vulnerables COUD/AEPDV (Grand Lac), Centre ESSOLE, Association de Développement, Lutte contre la Pauvreté Et pour la Défense des Droits de la Femme (ADPF), Hekabana, and Laissez l’Afrique Vivre (LAV). We thank them for their warm welcome, interest in the project, and their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to ethical confidentiality requirements, individual interview responses cannot be made publicly available. These responses are only presented in this study in aggregated form.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Roos van der Haer

Roos Haer Senior Assistant Professor at Leiden University (2017-); main research interests: children and youth in conflict zones and consequences of armed conflict.

Kathleen J. Brown

Kathleen Brown PhD Candidate at Leiden University (2020-); main research interests: economic development and the consequences of fiscal crises in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Notes

1 The UN convention on the Rights of the Child considers a child to be anyone below the age of 18, the United Nations Populations Fund differentiate between ‘adolescents’ (15-19 years old), ‘youth’ (15-24 years old), and ‘young people’ (10-24 years old). In this proposal, the terms youth, adolescents, and children are used interchangeable and is used to identify everyone under 24 years of age. See Myriam Denov, Child Soldiers. Sierra Leone’s Revolutionary Front (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) for more information on the concept of childhood and its associated problems.

2 Karim Bahgat, Kendra Dupuy, Gudrun Østby, Siri Aas Rustad, Håvard Strand and Tore Wig, ‘Children Affected by Armed Conflict, 1990–2016’, Conflict Trends, 1. (Oslo: PRIO, 2018). https://www.prio.org/publications/10868

3 See among others, the annual reports on Children and Armed Conflict published by the United Nations Secretary-General (UNSG; https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/document-type/annual-reports/). Following UNICEF (2007; the paris principles), we define child soldiers as ‘‘any person below 18 years of age who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group’’. We recognize, however, that this threshold is not without controversy. It is especially contested by anthropologists and sociologists working in childhood studies (see, for instance, Jason Hart, ‘Saving Children, What Role for Anthropology?’ Anthropology Today 22, no. 1 (2006): 5–8; Allison James and Adrian James. Key Concepts in Childhood Studies (London: Sage Publications, 2011).

4 Vera Achvarina and Simon F. Reich, ‘No Place to Hide: Refugees, Displaced Persons, and the Recruitment of Child Soldiers’, International Security 31, no. 1 (2006): 127-64; P. W. Singer, Children at War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006); Robert Tynes, Tools of war, Tools of State (Albany: SUNY Press, 2018); Robert Tynes and Bryan R. Early, ‘Governments, rebels, and the use of child soldiers in internal armed conflict: a global analysis, 1987-2007’, Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 21, no. 1 (2007): 79-110.

5 Radio Mille Coins, cited in: Human Rights Watch, Rwanda Lasting Wounds: Consequences of Genocide and War on Rwanda’s Children (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2003).

6 See among others; the fammous report made by Graça Machel, The Impact of Armed Conflict on Children (New York: UN, 1996) for the United Nations.

7 See, for instance, Mark A. Drumble, Child Soldiers in International Law and Policy (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2012); Jay Williams, ‘The international campaign to prohibit child soldiers: a critical evaluation’, The International Journal of Human Rights 15, no. 7 (2011), 1072-109.

8 See among others; Milfrid Tonheim, ‘‘Who will comfort me?’ Stigmatization of girls formerly associated with armed forces and groups in eastern Congo’, The International Journal of Human Rights 16, no. 2 (2012): 278-97; Anett Pfeiffer and Thomas Elbert, ‘PTSD, depression and anxiety among former abductees in Northern Uganda’, Conflict and Health 5, no. 14 (2011). Doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-5-14; Katharin Hermenau, Tobias Hecker, Anna Maedl, Maggie Schauer and Thomas Elbert. ‘Growing up in armed groups: trauma and aggression among child soldiers in DR Congo’, European Journal of Psychotraumatology 4, no. 1 (2013): 21408.

9 See among others; Patricia Justino, Marinella Leone and Paola Salardi, ‘Short- and Long-Term Impact of Violence on Education: The Case of Timor Leste’, The World Bank Economic Review 28, no. 2 (2014): 320-53; Christopher Blattman and Jeannie Annan, ‘The Consequences of Child Soldiering,’ The Review of Economics and Statistics 92, no. 4 (2010): 882-98.

10 See among others; Christopher Blattman, ‘From Violence to Voting: War and Political Participation in Uganda’, American Political Science Review 103, no. 2 (2009): 231-47; Michal Bauer, Alessandra Cassar, Julie Chytilová and Joseph Henrich, ‘War’s Enduring Effects on the Development of Egalitarian Motivations and In-Group Biases’, Pychological Science 25, no. 1 (2014): 47–57.

11 See among others: Cynthia Enloe, Bananas, Beaches and Bases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000); Goldstein, Joshua. War and Gender (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001); R. Charli Carpenter, Innocent women and children. Gender, norms and the protection of civilians (Burlington: Ashgate, 2006); Roos Haer and Tobias Böhmelt, ‘Girl soldiering in rebel groups, 1989–2013: Introducing a new dataset’, Journal of Peace Research 55, no. 3(2018), 395-403; Mary-Jane Fox, ‘Girl Soldiers: Human Security and Gendered Insecurity’, Security Dialogue 35, no. 4 (2004): 465-479.

12 Michael Wessells, ‘The recruitment and use of girls in armed forces and groups in Angola: implications for ethical research and reintegration’, Ford Institute for Human Security (2007).

13 Theresa S. Betancourt and Kashif Khan, ‘The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience, International Review of Psychiatry 20, no. 3 (2008): 317-28; Michael Rutter, ‘Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder,’ British Journal of Psychiatry 147 (1985): 598-611; Theresa S. Betancourt, Ivelina I. Borisova, Marie de la Soudière and John Williamson, ‘Sierra Leone’s Child Soldiers: War Exposures and Mental Health Problems by Gender’, Journal of Adolescent Health 49 (2011): 21-28.

14 Catherine Baillie Abidi, ‘Prevention, Protection and Participation: Children Affected by Armed Conflict’, Frontiers in Human Dynamics 3, DOI: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.624133.

15 Ibid.; Fox, ‘Girl Soldiers’; Nidhi Kapur and Hannah Thompson, ‘Beyond the Binary: Why Gender Matters in the Recruitment and Use of Children’, Allons-Y. Journal of Children, Peace and Security 5 (2021). DOI: 10.15273/allons-y.v5i0.10214

16 E. Kay M. Tisdall, ‘Conceptualising children and young people’s participation: examining vulnerability, social accountability and co-production’, The International Journal of Human Rights 21, no. 1 (2017): 59-75.

17 Judith A. Myers-Walls, ‘Children as Victims of War and Terrorism’, Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 8, no. 1-2 (2004): 41-62.

18 See among others, Fox, ‘Child soldiers and international law’; Claire Breen, ‘When is a child not a child? Child soldiers in international law,’ Human Rights Review 8 (2007): 71-103; Drumble, Child Soldiers in International Law; Williams, ‘The international campaign to prohibit child soldiers’; Mark Drumble and Gabor Rona, ‘Navigating Challenges in Child Protection and the Reintegration of Children Associated with Armed Groups’, in Cradled by Conflict. Child Invovlement with Armed Groups in Contemporary Conflict, eds. Siobhan O’Neil and Kato van Broeckhoven (United Nations University, 2018), pp. 210-235.

19 Williams, ‘The International campaign’.

20 Michael Wessells, ‘How We Can Prevent Child Soldiering’, Peace Review 12, no. 3 (2000): 407-13; D. Rosen, Child Soldiers in the Western Imagination: From Patriots to Victims (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2015).

21 G. Alex Sinha, ‘Child soldiers as super-privileged combatants’, The International Journal of Human Rights 17, no. 4 (2013): 584-603.

22 Tisdall, ‘Conceptualising children’.

23 Tara M. Collins, ‘A child’s right to participate: Implications for international child protection’, The International Journal of Human Rights 21, no. 1 (2017): 14-46.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Hermenau et al ‘Growing up in armed groups’, 21408.

27 Ibid.

28 Atle Dyregrov, Rolf Gjestad and Magne Raundalen, ‘Children exposed to warfare: A longitudinal study,’ Journal of Traumatic Stress 15, no. 1 (2002): 59-68.

29 Ibid.

30 Michal Bauer, Nathan Fiala and Ian Levely, ‘Trusting Former Rebels: An Experimental Approach to Understanding Reintegration after Civil War’, The Economic Journal 128, no. 613 (2018): 1786-1819.

31 Ibid.

32 Christopher Blattman, ‘From violence to voting: War and political participation in Uganda,’ American Political Science Review 103, no. 2 (2009): 231-247.

33 Macarta Humphreys and Jeremey M. Weinstein, ‘Demobilization and Reintegration’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 51, no. 4 (2007): 531-67.

34 Christopher Blattman and Jeannie Annan. ‘The consequences of child soldiering’, The Review of Economics and Statistics 92, no. 4 (2010): 882-98.

35 Olga Shemyakina, ‘The effect of armed conflict on accumulation of schooling: Results from Tajikistan’, Journal of Development Economics 95 (2011): 186-200.

36 Rubiana Chamarbagwala and Hilcías E. Morán, ‘The human capital consequences of civil war: Evidence from Guatemala,’ Journal of Development Economics 94, no. 1 (2011): 41-46.

37 Collins, ‘A child’s right’, 6.

38 See among others, Enloe, Bananas, Beaches and Bases; Goldstein, War and Gender; Carpenter, Innocent women and children.

39 Enloe, Bananas, Beaches and Bases.

40 Carpenter, Innocent women.

41 Shelley Saywell, Women in War: First-Hand Accounts from World War II to El Salvador (New York: Viking, 1985).

42 Cynthia Cockburn, ‘War and security, women and gender: an overview of the issues’, Gender & Development 21, no. 3 (2013): 433-452.

43 Elisabeth Rehn and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Women, War and Peace: The Independent Experts’ Assessment on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Women and Women’s Role in Peace-building (New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women, 2002).

44 See among others, Augustine S. J. Park, ‘‘Other Inhumane Acts’: Forced Marriage, Girl Soldiers and the Special Court for Sierra Leone,’ Social & Legal Studies 15, no. 3 (2006): 315-37; Susan McKay and Dyan E. Mazurana, Where Are the Girls?: Girls in Fighting Forces in Northern Uganda, Sierra Leone and Mozambique: Their Lives During and After War (Montréal, Quebec: Rights & Democracy, 2004); Fox, ‘Girl Soldiers’; Myriam Denov, ‘Girl Soldiers and Human Rights: Lessons from Angola, Mozambique, Sierra Leone and Northern Uganda,’ The International Journal of Human Rights 12, no. 5 (2008): 813-36.

45 Dyan E. Mazurana, Susan A. McKay, Khristopher C. Carlson and Janel C. Kasper, ‘Girls in Fighting Forces and Groups: Their Recruitment, Participation, Demobilization, and Reintegration’, Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 8, no. 2 (2002): 97-123.

46 McKay and Mazurana, Where Are the Girls?

47 Denov, ‘Girl Soldiers and Human Rights’; China Keitetsi, Child Soldier: Fighting For My Life (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2002).

48 Wessells, ‘The Recruitment and Use of Girls’.

49 Jeannie Annan, Christopher Blattman, Dyan Mazurana and Khristopher Carlson, ‘Civil War, Reintegration, and Gender in Northern Uganda,’ Journal of Conflict Resolution 55, no 6. (2011):877-908.

50 Collins, ‘A child’s right’.

51 Kirsi Peltonen, Samir Qouta, Marwan Diab and Raija-Leena Punamäki, ‘Resilience Among Children in War: The Role of Multilevel Social Factors,’ Traumatology 20, no. 4 (2014): 232-40; Rutter, ‘Resilience in the face of adversity’; Betancourt and Khan, ‘The mental health of children’; Bonnie Benard, Fostering resilience in children (Urbana IL: University of Illinois, 1995). Cherylynn Bassani, ‘Five Dimensions of Social Capital Theory as they Pertain to Youth Studies’, Journal of Youth Studies 10, no. 1 (2007): 17-34.

52 Paul M. Kline and Erin Mone, ‘Coping with War: Three Strategies Employed by Adolescent Citizens of Sierra Leone,’ Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 20, no. 5 (2003): 321-33.

53 Judith A. Myers-Walls and Karen S. Myers-Bowman, ‘War and Families’ in The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies, ed. Constance L. Shehan (London: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 1-4.

54 See among others; Michelle Slone and Shiri Mann, ‘Effects of War, Terrorism and Armed Conflict on Young Children: A Systematic Review,’ Child Psychiatry and Human Development 47, no. 6 (2016): 950-65; Miriam Schiff, Ruth Pat-Horenczyk, Rami Benbenishty, Danny Broma, Naomi Baum and Ron Avi Astor, ‘High school students’ posttraumatic symptoms, substance abuse and involvement in violence in the aftermath of war’, Social Science & Medicine 75, no. 7 (2012): 1321-28; E Mark. Cummings, Alice C. Schermerhorn, Christine E. Merrilees, Marcie C. Goeke-Morey, Peter Shirlow and Ed Cairns, ‘Political violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland: Testing pathways in a social–ecological model including single-and two-parent families’, Developmental Psychology 46, no. 4 (2010): 827-41.

55 Kline and Mone, ‘Coping with war’.

56 Samit Qouta, Raija-Leena Punamäki and Eyad El Sarraj, ‘Child Development and Family Mental Health in War and Military Violence: The Palestinian Experience’, International Journal of Behavioural Development 32, no. 4 (2008): 310-21

57 See among others, Judith A. Myers-Walls, ‘Children as Victims of War and Terrorism’, Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 8, no. 1-2 (2004): 41-62; Nathaniel Laor, Leo Wolmer, Linda C. Mayes, Avner Gershon, Ronit Weizman and Donald J. Cohen, ‘Israeli preschool children under Scuds: a 30-month follow-up’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36, no. 3 (1997): 349-56; Myriam Denov and Meaghan C. Shevell, ‘Social work practice with war affected children and families: the importance of family, culture, arts, and participatory approaches’, Journal of Family Social Work 22, no. 1 (2019): 1-16.

58 Don Operario, Jeanne Tschann, Elena Flores and Margaret Bridges, ‘Brief report: associations of parental warmth, peer support, and gender with adolescent emotional distress’, Journal of Adolescence 29, no. 2 (2006): 299-305.

59 Nash, Susan G., Amy McQueen and James H. Bray, ‘Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: family environment, peer influence, and parental expectations’, Journal of Adolescent Health 37, no 1. (2005): 19-28.

60 Laurence Steinberg, ‘We know some things: parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect’, Journal of Research on Adolescence 11, no. 1 (2001): 1-19.

61 Beth Verhey, ‘Child Soldiers: Preventing, Demobilizing and Reintegrating’, Africa Region Working Paper Series No. 23 (2001). Available online via: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/4EE121110BC1BBBCC1256DAB004202C3-wb-child-nov01.pdf

62 Theresa S. Betancourt, Dana L. Thomson, Robert T. Brennan, Cara M. Antonaccio, Stephen E. Gilman and Tyler J. Vander Weele, ‘Stigma and Acceptance of Sierra Leone’s Child Soldiers: A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Adult Mental Health and Social Functioning’, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 59, no. 6 (2020): 715-26.

63 Qouta, Punamäki, and El Saeeaj, ‘Child Development’.

64 Marwan Diab, Raija-Leena Punamäki, Esa Palosaari and Samir R. Qouta, ‘Can Psychosocial Intervention Improve Peer and Sibling Relations Among War-affected Children? Impact and Mediating Analyses in a Randomized Controlled Trial’, Social Development 23, no. 2 (2014): 215-31; Kirsi Peltonen, Samir Qouta, Eyad El Sarraj and Raija-Leena Punamäki, ‘Military Trauma and Social Development: The Moderating and Mediating Roles of Peer and Sibling Relations in Mental Health’, International Journal of Behavioural Development 34, no. 6 (2010): 554-63.

65 Peltonen et al. ‘Military Trauma’; Kirsi Peltonen, Samir Qouta, Marwan Diab and Raija-Leena Punamäki, ‘Resilience among children in war: The role of multilevel social factors’, Traumatology 20, no. 4 (2014): 232-40.

66 Peltonen et al. ‘Military Trauma’.

67 Kline and Mone, ‘Coping with war’.

68 Peltonen et al. ‘Military Trauma’.

69 B. Paardekooper, J.T. de Jong and J.M. Hermanns, ‘The psychological impact of war and the refugee situation on South Sudanese children in refugee camps in Northern Uganda: an exploratory study’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 40, no. 4 (1999): 529-36.

70 Peltonen et al. ‘Military Trauma’; Mona S. Macksoud and J. Lawrence Aber, ‘The war Experiences and Psuchosocial Dveelopment of Children in Lebanon’, Child Development 67, no. 1 (1996): 70-88; Ervin Staub, and Johanna Vollhardt, ‘Altruism Born of Suffering: The Roots of Caring and Helping After Victimization and Other Trauma’, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 28, no. 3 (2008): 267-80.

71 Myriam Denov, ‘Coping with the trauma of war: Former child soldiers in post-conflict Sierra Leone’, International Social Work 53, no. 6 (2010): 791-806.

72 Peltonen et al. ‘Military Trauma’.

73 Diab et al. ‘Can Psychosocial Intervention’. Peltonen et al. ‘Military Trauma’.

74 See among others, Justino et al ‘Short- and Long-Term Impact’.

75 Jessica Alexander, Neil Boothby and Michael Wessells, ‘Education and protection of children and youth affected by armed conflict: An essential link’, Protecting education from attack: A state of the art review (2010): 55-67.

76 Maryanne Loughry, Alistair Ager, Eirini Flouri, Vivian Khamis, Abdel Hamid Afana and Samir Qouta, ‘The impact of structured activities among Palestinian children in a time of conflict’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 47, no. 12 (2006): 1211-18.

77 Yaacov B. Yablon, ‘Student–teacher relationships and students’ willingness to seek help for school violence’, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 27, no. 8 (2010): 1110-1123; Yaacov B. Yablon, ‘Positive School Climate as a Resilience Factor in Armed Conflict Zones’, Psychology of Violence 5, no. 4 (2015): 393-40; Christopher Blattman and Jeannie Annan, ‘Child Combatants in Northern Uganda: Reintegration Myths and Realities’, in Security and Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Dealing with Fighters in the Aftermath of War, ed. Robert Muggah (London: Routledge, 2009), 103-126.

78 Yablon, ‘Positive School Climate’.

79 Yablon, ‘Student-teacher relationships’; Merav S. Even-CHen and Haya Itzhaky, ‘Exposure to terrorism and violent behavior among adolescents in Israel’, Journal of Community Psychology 35, no. 1 (2007), 43–55.

80 See for excellent overview on the history of the Congo among others: Gérard Prunier, Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009); David Van Reybrouck, Congo: The Epic History of a People (New York: Harper Collins, 2014).

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid.

83 International Rescue Committee, ‘Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An ongoing crisis’, 2007. https://www.rescue.org/report/mortality-democratic-republic-congo-ongoing-crisis.

84 World Vision, ‘Conflict in Democratic Republic of Congo ‘one of the worst child protection crises’, 2017. https://www.wvi.org/it-takes-world/pressrelease/conflict-democratic-republic-congo-%E2%80%98one-worst-child-protection-crises%E2%80%99

85 UNHCR, ‘Democratic Republic of the Congo situation’, 2024. Available online via: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/democratic-republic-congo-situation. UNHCR, ‘Operational Data Portal: Refugees and asylum seekers from DRC’, 2024. Available online via: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/drc; UNICEF, ‘Child Protection’, 2024. Availabel online via: https://www.unicef.org/drcongo/en/what-we-do/child-protection; UNSG, ‘Secretary-General Annual Report on Children and Armed Conflict’, 2023. Available online via: https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/document-type/annual-reports/.

86 BVES, CAPA, COUD / AEPDV (Grand Lac), Centre ESSOLE, ADPF, Hekabana, and LAV.

87 Nissim Cohen and Tamar Arieli, ‘Field research in conflict environments: Methodological challenges and snowball sampling,’ Journal of Peace Research 48, no. 4 (2011): 423-35.

88 In addition to the upcoming analysis, we have conducted some interesting analysis concerning the role of abduction. These can be found in the supplementary file.

89 Verena Ertl, Anett Pfeiffer, Regina Saile, Elisabeth Schauer, Thomas Elbert, and Frank Neuner, ‘Validation of a mental health assessment in an African conflict population,’ Psychological Assessment 22, no. 2 (2010): 318-24.

90 See among others, Ertl et al. ‘Validation of a mental health assessment’; Hecker et al., ‘Growing up in armed groups’; Hawkar Ibrahim, Verena Ertl, Claudia Catani, Azad Ali Ismail and Frank Neuner, ‘The validity of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq’, BMC psychiatry 18, no. 1 (2018): 1-8; Regina Saile, Frank Neuner, Verena Ertl and Claudia Catani, ‘Prevalence and predictors of partner violence against women in the aftermath of war: a survey among couples in Northern Uganda,’ Social Science & Medicine 86 (2013): 17-25.

91 Paula Paiva, Cristina Pelli, Haroldo Neves de Paiva, Paulo Messias de Oliveira Filho, Joel Alves Lamounier, Efigênia Ferreira E. Ferreira, Raquel Conceição Ferreira, Ichiro Kawachi and Patrícia Maria Zarzar. ‘Development and validation of a social capital questionnaire for adolescent students (SCQ-AS).’ PloS one 9, no. 8 (2014): e103785.

92 See among others, Qouta, Punamäki and El Saeeaj, ‘Child Development’.

93 Annan et al. ‘Civil War, Reintegration’.

94 Kristin Barstad, ‘Preventing the Recruitment of Child Soldiers: The ICRC Approach’, Refugee Survey Quarterly 27, no. 4 (2008): 142-49.

95 Glenn P. Malone, David R. Pillow and Augustine Osman, ‘The General Belongingness Scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness’, Personality and Individual Differences 52, no. 3 (2012): 311–16.

96 Paula M. Pickering, ‘Generating social capital for bridging ethnic divisions in the Balkans: Case studies of two Bosniak cities’, Ethnic and racial Studies 29, no. 1 (2006): 79-103; Tracey Reynolds, ‘Friendship networks, social capital and ethnic identity: Researching the perspectives of Caribbean young people in Britain’, Journal of youth studies 10, no. 4 (2007): 383-98; Oliver Kaplan and Enzo Nussio, ‘Community counts: The social reintegration of ex-combatants in Colombia,’ Conflict Management and Peace Science 35, no. 2 (2018): 132-53.

97 Richard Bowd, From combatant to civilian: The social reintegration of ex-combatants in Rwanda and the implications for social capital and reconciliation. PhD thesis (England, University of York, 2008).

98 Marianne E. Krasny, Leigh Kalbacker, Richard C. Stedman and Alex Russ, ‘Measuring social capital among youth: applications in environmental education,’ Environmental Education Research, 21, no. 1 (2015): 1-23.

99 See among others, Peltonen et al. ‘Military Trauma’; Paardekooper, De Jong, and Hermanns, ‘The psychological impact’.

100 Paiva et al., ‘Development and Validation’.

101 See among others, Tonheim, ‘‘Who will comfort me?’’; Mazurana et al., ‘Girls in Fighting Forces’; Blattman and Annan, ‘The Consequences’.

102 Tonheim, ‘‘Who will comfort me?’’; Annan et al. ‘Civil War, Reintegration’.

103 Mone, ‘Coping with war’; Theresa S. Betancourt, ‘Attending to the Mental Health of War-Affected Children: The Need for Longitudinal and Developmental Research Perspectives’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 50, no. 4 (2011): 323-25.