ABSTRACT

This research investigates the perceptions of a group of secondary science teachers (26) from six schools in a remote part of northern Scotland of the opportunities afforded to them for effective professional learning. Focus groups of science teachers were conducted, and the findings identified a number of key areas they perceived as effective professional learning, including the availability of a wide range of opportunities for professional learning from a number of providers, the professional learning in their own schools and collaboration with colleagues. However, they also identified a number of key barriers including their remote location from the Central Belt of Scotland, which they perceived to be the key source of effective professional learning in Scotland. They also identified lack of time, workload and initiative overload as key barriers. Finally, implications for further research are explored.

Introduction

The study sought to determine the views of physics teachers (physics specialists and other science specialists teaching some physics) in secondary schools across the north of Scotland about their access to professional learning (PL), what they value in PL and barriers to PL. The study was conducted as an initial ‘fact-finding’ stage which helped inform and shape a subsequent research project into the support and development of improved networking and collaborative working between physics teachers in a relatively remote rural area in the north of Scotland. This initial stage draws upon the study conducted by Tytler et al. (Citation2011) in similar remote communities in Victoria, Australia.

Throughout this article, the term ‘PL’ is used to describe the range of activities and events which teachers might engage with that result in professional development or growth. This usage is consistent with Fullan and Hargreaves (Citation2016, 3) where they reject the term ‘professional development’ as describing an event attended by teachers. They define PL as including attending events and conferences, collaborative enquiry, reading and other activities that introduce a teacher to something new. They define professional development as a change in the person as a professional, referring to previous work of Hargreaves (Citation2003, 48): ‘It is through personal and professional development that teachers build character, maturity, and virtues in themselves and others, making their schools into moral communities.’

Physics education is used as the context for this study as it is the subject area in which the lead author has a professional role and extensive contacts. There is no evidence that the experiences of effective PL in remote areas (the focus of this article) are significantly different for physics teachers than for teachers of other subjects. Physics education provides a good case study for investigating more generic PL issues as physics is a subject experiencing teacher shortages, a particular challenge for remote and rural areas (Seith and Hepburn Citation2017). The provision of good-quality PL has been shown to be a factor in retaining teachers (Allen and Sims Citation2017).

The policy background and literature are first explored before providing details of the research questions and methodology. The findings and discussion are structured around the main themes emerging from the data.

Policy background

In recent years in Scotland, there have been moves to increase the emphasis on collaborative enquiry and research in the PL of teachers. This has been largely in response to a review of teacher education in Scotland (Donaldson Citation2010). Enquiry and research are included in the General Teaching Council for Scotland’s (GTCS) standards documents (GTCS Citation2012a, Citation2012b), and the Scottish College for Educational Leadership (SCEL Citationn.d.-a) was set up to deliver support programmes such as in Teacher Leadership (SCEL Citationn.d.-b), which has a strong focus on enquiry approaches. The OECD review of Scottish education also recommended that ‘a coherent strategy for building teacher and leadership social capital’ be developed (Hargreaves et al. Citation2015, 140). It stated:

Teachers who work in cultures of professional collaboration have a stronger impact on student achievement, are more open to change and improvement, and develop a greater sense of self-efficacy than teachers who work in cultures of individualism and isolation. Not all kinds of professional collaboration are equally effective.

This highlights that teacher collaboration can take many forms, but here we define it as any activities where teachers work together with a common purpose.

As part of the national teachers’ contract in Scotland, there is a requirement, and entitlement, for all teachers to undertake 35 hours of PL activities per year.

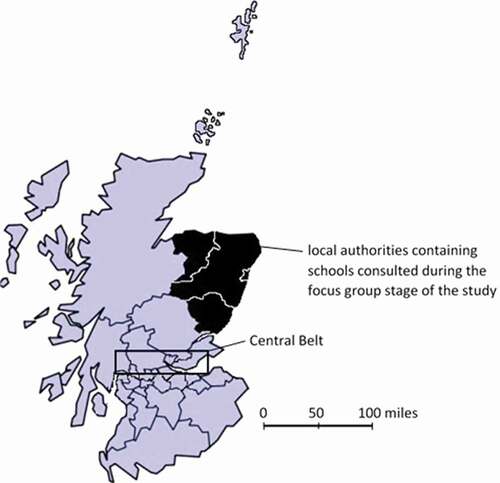

Apart from a relatively small independent-school sector, Scottish schools are governed and funded through 32 local authorities (LA). These vary in size from having two secondary schools, along with their associated primary schools, to a few with more than 20 secondary schools. The geography of Scotland is such that the great majority of its population resides in the Central Belt with more sparsely populated rural areas to the north and south. See for a map of the area under study.

Figure 1. The local authorities areas of Scotland and the location of schools in this study relative to the main population centres in the Central Belt.

In 2017 it was proposed by the Scottish Government that six Regional Improvement Collaboratives be set up (Priestley Citation2017; Scottish Government Citation2017a) to promote and improve collaborative working across and between LAs. This is potentially a significant challenge for schools in more remote and rural areas, and these schools and the physics teachers within them are the focus of this study.

The literature

This study was particularly informed by the work of Tytler et al. (Citation2011) which explored similar issues with teachers with similar subject backgrounds in schools in similar locations remote from the main population centre, in the state of Victoria. Hargreaves, Parsley, and Cox (Citation2015) describe similar issues with regard to supporting effective collaborative PL between small geographically remote schools in the Pacific Northwest. The design of the study was also informed by the work of Kennedy which considered the views and values of teachers in Scotland regarding the effectiveness of their PL, especially collaborative learning. Kennedy’s semi-structured interview schedule was used as the basis for questions during the focus groups (Kennedy Citation2011, 41).

Over the last two decades, there has been a significant growth in the literature which shows that collaborative PL has impact on both the professional practice of teachers and the outcomes of their pupils (Cordingley et al. Citation2003, Citation2005, Citation2015; CUREE Citation2018; Darling-Hammond, Hyler, and Gardner Citation2017; Harris, Jones, and Huffman Citation2017; Lieberman, Campbell, and Yashkina Citation2017; Stoll et al. Citation2006; Timperley et al. Citation2007). Collaborative working can manifest itself in various forms from informal to more formal. Informal PL can occur frequently between colleagues on a daily basis in staff bases, over lunch, or whenever the opportunity arises (Mawhinney Citation2010; McNicholl, Childs, and Burn Citation2013; Williams Citation2003; Williams, Prestage, and Bedward Citation2001). More formal arrangements can also take many forms from relatively loose networks of teachers to more structured and focussed professional learning communities (PLC) or teacher learning communities (TLC). In secondary schools, these are likely to be organised around departmental teams or cross-curricular teams of a few teachers. There are various approaches such teams may take in their PL such as coaching, mentoring and peer networking (Rhodes and Beneicke Citation2002), lesson study (Lewis, Perry, and Murata Citation2006), action research (Fazio and Melville Citation2008), practitioner enquiry (Gilchrist Citation2018) and PLC (Bolam et al. Citation2005; Stoll et al. Citation2006). All such collaborative practices display characteristics of what Wenger (Citation1998) describes as ‘communities of practice’ whereby groups work towards a shared purpose through shared knowledge, shared values, mutual engagement and joint enterprise.

In her summary of the research on the PL which has the most impact on improving pupil outcomes, Timperley (Citation2008) identifies 10 principles. These include that PL should include opportunities for collegial interaction and the input of expertise external to this collegial group. Timperley’s 10 principles do not operate independently; rather, they are integrated to inform cycles of learning and action, such as those described by Korthagen and Kessels (Citation1999, 13), Timperley et al. (Citation2007, xliii) and Donohoo and Velasco (Citation2016, 6). It can be seen from these principles that, in order for PL to have maximum impact for teachers, it must be embedded in the context of the teacher, integrate new and worthwhile subject knowledge with pedagogical knowledge, have input from knowledgeable others (KO) to ensure development occurs rather than the ‘sharing of ignorance’ (Guskey Citation1999, 12), be truly collaborative rather than display ‘contrived collegiality’ (Hargreaves and Dawe Citation1990), be sustained and very much focused on pupil outcomes. In the CUREE (Citation2018, 5) review of subject-specific PL, it is stated that ‘An important feature of effective CPD [Continuing Professional Development] is that it is either focussed directly on developing knowledge or practice in a subject area, or focussed on developing an aspect of teaching and learning in ways that are contextualised for specific subjects.’ Later in the report, it also cautions that ‘There is also a need to ensure that research- and evidence-informed practice does not become distorted, and distract from a focus on subject-specific approaches and implications’ (7).

Secondary schools are commonly split into departments or faculties; these act as more than administrative units, they provide the professional identity and context for many secondary teachers (Brooks Citation2016; Siskin Citation1994). As well as generic pedagogical knowledge, secondary teachers have subject matter knowledge (SMK) and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) (Shulman Citation1986, Citation1987) which is specific to the subject(s) they teach, and the department provides the locus for much professional discussion and collaboration. Subject departments therefore act as ‘communities of practice’ for many secondary teachers and are the primary site for the PL for many secondary teachers (Tytler et al. Citation2011, 872).

Effective collaboration within departments is an issue for small departments in small schools in rural and relatively remote geographical areas as there are few subject colleagues within any one school, and adjacent schools are some distance apart (Hargreaves, Parsley, and Cox Citation2015, 306; Tytler et al. Citation2011, 877). Schools in more remote areas tend to be some distance from universities, science industries and other sources of KOs in science or education. In addition, in many countries, the recruitment and retention of staff has been shown to be difficult in rural areas, particularly in subjects such as science and mathematics (Azano and Stewart Citation2016; CUREE Citation2018; Kaden et al. Citation2016; Kitchenham and Chasteauneuf Citation2010; Lock et al. Citation2009; Seith and Hepburn Citation2017; Tytler et al. Citation2011).

There are therefore a number of issues which may impact on the effectiveness of PL for teachers of physics in schools across the north of Scotland. This study therefore set out to determine teachers’ views regarding opportunities and constraints for PL in remote communities in Scotland in a way that could inform future work in this area.

The research questions

1. What PL opportunities and resources do teachers perceive are available to them?

2. Which PL opportunities and resources are most valued and least valued by participating teachers?

3. What are the key issues that teachers perceive constrain PL?

Methodology

This study sought to elicit teachers’ perceptions of their PL, therefore a qualitative methodology was adopted using six focus groups, involving a total of 26 teachers, in six secondary schools across four LAs across the north of Scotland. It is normal in Scotland, due to GTCS requirements for registration as a teacher, that specialist teaching of physics to pupils aged 15 to 18 is to be taught by a teacher meeting the GTCS standards for registration as a teacher of physics with science. Courses at this age range lead to Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) National Qualifications. However, in the Broad General Education (BGE) phase in lower secondary for pupils aged 12 to 15, physics is normally taught as part of a general science course by teachers with a main subject specialism of either biology, chemistry or physics, but also registered to teach science at this phase of education. Therefore, it is normal for all secondary science teachers in Scotland to be teaching some physics in the BGE phase. The study thus sought to include teachers registered to teach not only physics but also biology and chemistry.

The sample was partly a convenience sample for geographical reasons with all schools being within a 100-minute drive of the first researcher’s base. It was also chosen to give a good range of schools across the different LAs involved in order to try and identify generic issues as well as ones which might be LA specific. The schools chosen were all ones where staff had a good record of engaging with PL activities, and/or hosting PL events, and/or had expressed an interest in using educational research. As such, this is likely to be a ‘best-case’ sample consisting of teachers relatively well engaged with PL. They were also likely to have given greater thought and consideration to the issues involved than teachers in some other schools. Focus groups were used with the intention, as Wilkinson and Birmingham (Citation2003, 92) say, ‘that the discussion will be richer, deeper and more honest and incisive than any interview with a single participant could produce’. Physics, biology and chemistry specialists were all well represented in the sample. Whilst the researcher did not set out to construct a representative sample of teachers from across the four LAs involved, nevertheless although those involved are likely to be, as said, a ‘best-case’ and somewhat self-selecting, the final sample does give a good representation. Descriptions of the schools and teachers are provided in .

Table 1. Schools visited and teachers interviewed in the focus groups

The Scottish Government (Scottish Government Citation2018) defines remote rural areas as settlements with populations of less than 3000 and more than 30 minutes from a population centre of more than 10,000. Whilst this may be a good definition for basic healthcare, schooling or retail, in this article it is argued that it is not applicable to the case of teacher PL. All schools included in the sample are considered remote because it is a drive of approximately 100 to 250 minutesFootnote1 north to the main population centres in the Central Belt of Scotland where much teacher PL is available.

To arrange the focus groups, the lead author approached a known contact in each of the six schools and asked if they would be willing to be involved in the study, and if so if they could arrange a small group of their colleagues to form a focus group. All contacts approached agreed to do so and arranged the six focus groups described in .

The questions for the focus groups were designed to address the research questions and covered the following areas: PL opportunities – in schools and elsewhere; how this PL is valued by teachers; access to knowledgeable others during PL; barriers to PL, and how participants would wish their PL to develop in the future. They were sent to the teachers in the focus groups a few days in advance of the focus group meetings to allow them to give the questions some consideration in advance of the interviews. All staff in each school were interviewed as one group, and the lead author facilitated the focus groups. Whilst it is acknowledged that the lead author is well known to the participants and this may affect objectivity in the study, the focus group format was chosen because it allowed the teachers to discuss the questions posed amongst themselves with the lead author taking a facilitating role.

Extensive and detailed notes were taken at each of the focus group interviews. All the notes from each focus group were coded according to which teacher made the comment and also in relation to the topics covered in the focus group interview schedule (Kennedy Citation2011, 41). As the teachers often made comments ranging over different research questions and topics, all of the comments relating to each were collated together regardless of the timing of their occurrence during the focus group discussions. These collations were subsequently typed up and summarised by the lead author. Analysis of the focus group data was undertaken by both authors following the advice of Onwuegbuzie et al. (Citation2009) where we took a more grounded approach informed by constant comparative analysis. This process identified the following recurring themes which emerged in the different focus groups:

collaboration with colleagues;

remoteness and rurality;

school and local authority professional learning;

subject-specific professional learning;

access to knowledgeable others;

barriers to effective professional learning.

That the researcher was well known to many of the participants had the advantage of allowing easy access and little time needed to build a trusting relationship. However, in this type of ‘insider’ research there is a danger of the researcher being too closely involved to be fully objective. This was minimised by the researcher not imposing a framework on the analysis and, as discussed above, using the focus group format for eliciting their perspectives.

Findings

This section is structured around the research questions and the main themes for each that emerged from the analysis of the data. The first section addresses research question 1, the second research question 2 and the third section addressed research question 3.

What PL opportunities and resources do teachers perceive are available to them?

Teachers in all six schools all valued opportunities for PL and perceived that there were a wide range of opportunities for PL. The responses from the focus groups identified all of the following opportunities for PL: learning from and with colleagues; school provided PL sessions – twilights, lunchtimes and in-service days; LA provided sessions; university courses, including the Open University; Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs); Scottish Schools Education Research Centre (SSERC) courses; learned society and professional association events and conferences; subject-specific email fora and sharing websites; TeachMeets and Pedagoo eventsFootnote2 and events provided by SQA on national curriculum and assessment changes.

Which PL opportunities and resources are most valued and least valued by participating teachers?

Working with departmental colleagues

All teachers interviewed identified their departmental colleagues as a valuable source of PL. This was clearly the most significant source of teacher learning in all schools and was valued highly by all. It consisted of discussion and questioning in both formal and informal meetings and through observation.

All teachers reported informal learning with colleagues, during non-contact periods, at breaks, lunchtime and before or after the timetabled school day, and opportunities for doing this were recognised as important:

There is lots of talking to colleagues, especially about developing practical work. (Teacher 45)

All schools had some form of periodic departmental or faculty meeting arrangement which met at different frequencies from weekly to termly, and it was considered that these provided an opportunity to share good practice. Some schools also organised twilight or lunchtime PL sessions and made use of time made available on in-service days for sharing best practice and discussing teaching and learning issues.

In all schools, collaboration between teachers across science was strong in the BGE phase with specialists frequently assisting their non-specialist colleagues, particularly when developing new courses and when setting up apparatus for practical work:

We learn by doing and talking to colleagues who have done things before. (Teacher 51)

It was acknowledged that the level of collaboration depended on the culture and management of the collaborative group and that some leadership or facilitation for the group is required.

Teachers saw their colleagues as very significant and accessible sources of professional advice but indicated they needed more time, both formally and informally, to discuss the development of teaching and learning in their context. This was particularly significant at times of high levels of change taking place in national curriculum and assessment arrangements which add significant pressure on teacher workload.

Professional learning within schools

While the support from immediate departmental colleagues was widely valued and welcomed, whole-school opportunities gained a more mixed response from teachers. All focus groups indicated that there was a lot of expertise within their schools, but this was not always identified and opportunities to share this expertise were often limited. A few indicated that school Senior Leadership Teams (SLT) were valuable in identifying staff who had useful expertise to share.

Several schools organised a programme of PL sessions in the form of lunchtime or twilight workshops and these were generally viewed positively. However, time was a restriction on these, as well as child-care and similar issues for some staff. Some schools offered a wide range of options delivered by school staff, but these did not always run due to lack of uptake, and the offer was generally the same for all teachers regardless of experience.

Whole-school in-service day activities were generally rated poorly. Many commented on SLT members and LA staff being removed from the realities of teaching and presenting poorly organised and structured sessions in a top-down fashion with little explanation of the rationale behind what they were doing, or opportunities for teachers to question or discuss this. Teachers therefore felt they were frequently being told to do things without understanding why.

Teachers in schools in all LAs were, or had been, involved in some form of in-school PLC or TLC, often facilitated by an external organisation, either directly or through a cascade model through some ‘lead’ staff members. These were generally seen as being a good idea but were often perceived to be implemented badly and were not always sustained beyond an initiative phase. Many of the TLCs had been initially set up on a voluntary basis, mostly involving cross-curricular groups of teachers. Frequently, schools had then decided that these groups become mandatory. Teachers reported that this decreased the usefulness and effectiveness of these groups as this changed the culture and nature of participation. Teachers reported that to be effective TLCs needed to be well led and to have a clear rationale, focus and purpose. Many reported that better facilitation and better input from appropriate KOs were required. Staff in one school in particular were very positive about the principles of the TLC work with which they were engaged, particularly its focus on collaborative enquiry and using research in the classroom. However, they thought they lacked good input from KOs to move their own PL and practice forward. They considered the support from the commercial organisation facilitating the TLC poor and also rated their experiences of inputs from university staff poorly, considering them lacking in an appreciation of the interplay between theory and practice in their context.

Between-school professional learning in local authorities

The importance and value teachers placed on being able to work collaboratively with colleagues in their own schools and with subject staff from other local schools was very apparent. However, centrally provided LA support for this was generally seen as not meeting teachers’ needs well. For example, when commenting about a large centrally organised LA Learning Festival, one teacher said:

[The Learning Festival was] as much use as a hole in the head. We were told to go but it was the biggest waste of my time and not appropriate for our needs at the time. (Teacher 13)

LA subject networks were seen by most as an important opportunity for collaborative between-schools working, and all LAs currently or recently had some sort of subject network in place. Teachers in all LAs did not think these meetings operated effectively. While many saw them as good opportunities to share resources and compare progress between schools, others saw them as largely ineffective as nothing more than this was achieved. The effectiveness of LA subject networks was seen to be compromised by there being a lack of leadership, support, time for meeting and group administration, and there being too little focus on teaching and learning but too much on administrative issues and accountability agendas dictated by the LA. Too often, network meetings were seen only as opportunities for teachers to share surface details of their work, rather than to discuss and work on deeper teaching and learning matters, or worse still, little more than opportunities for teachers to vent their frustrations with the demands put upon them. Opportunities for all physics teachers in an LA to meet together on some in-service days were welcomed, but these meetings suffered from similar problems to those of the network meetings.

Support from KOs

Having subject-specialist teachers in all three sciences within school science faculties was seen to be valued as they can act as KOs for teachers when working outside their own specialist area. A range of other KOs were acknowledged to exist within schools, such as an excellent librarian mentioned by staff in one school.

SSERC and Institute of Physics (IOP) staff were widely acknowledged to be KOs and their high-quality subject-specific advice appreciated, as well as their work in helping improve communication, bringing people together and providing shared resources. In addition, support for new subject-specific pedagogical approaches to, for example, practical work was valued, and when equipment was also provided it was greatly valued. They were also accessible remotely via subject email fora and directly by telephone and email.

Teachers in most schools talked positively about the use of subject email fora as a means of helping teachers communicate with each other and to provide help and advice to each other in a manner where hierarchies and other barriers are diminished, although some mentioned these provided a means for some to ‘share ignorance’.

Some schools had developed good industry links bringing teachers in contact with KOs from business and industry.

Support from university sources received a more mixed response. Teachers mentioned contact with KOs from universities, either when student teachers were placed in their school, or for a small number of teachers when undertaking leadership, Masters or doctoral studies. Some were very positive about MOOC and Open University courses for developing SMK. However, leadership and more generic education courses received a mixed response with some positive but several others very negative, stating that what had been studied was not particularly relevant to their context. One group was particularly scathing of university staff being out of touch with classroom realities.

What are the key issues that teachers perceive constrain PL?

Having considered the PL opportunities and resources teachers perceived are both available and valued by them (research question 1), the final section presents the findings in relation to research question 2, the key issues that teachers perceive constrain PL.

Lack of time, workload and initiative overload

The overwhelming response to asking what barriers prevented effective PL was ‘lack of time’, very closely followed by the related issue of ‘workload’. Teachers in all schools complained about not having enough non-teaching time, once other demands were acted upon, or insufficient non-teaching time in common between teachers to facilitate meetings and collaborative working for teachers to discuss teaching and learning together and share professional knowledge and experiences with colleagues in their own schools, at subject and more generic levels, and with subject staff from other local schools. Teachers indicated they needed more time, both formally and informally, to discuss the development of teaching and learning in their context, particularly at times of curriculum and assessment change.

Teachers frequently commented that when teachers were released or supported to attend external courses or conferences, there was insufficient time for them to share their learning with their colleagues, or for follow-up and consolidation thereafter. There was a ‘dribble’ rather than a ‘cascade’.

Initiative overload was frequently identified, and teachers wished to see developments be given enough time to bed in properly before being evaluated. Those having impact then being supported on a sustainable basis rather than drop down the priority list, only to be replaced with other initiatives which further increased workload and reduced time for effective PL focused on improving teaching and learning.

Rurality and remoteness

Not all were in rural areas, but remoteness from the main population centres was a consistent issue and obviously considered by many to be a constraint on their PL, for example:

Much of the good PL happens in the Central Belt. It would be good to have more opportunities in this area without the need for travelling and overnight accommodation. (Teacher 63)

The need for such travel and accommodation puts further pressure on budgets and supply teacher cover, which was in short supply. Although teachers thought that SSERC in particular provided excellent advice on science practical work and health and safety, access to its base in the Central Belt was seen as an issue for those in more remote schools. It was appreciated, and commented upon favourably, that many SSERC courses came with funding schemes to assist with costs.

Restricted funding was also seen as being a significant barrier for many attending courses or taking part in PL. Often teachers were self-censoring with regard to asking for PL, which they thought was likely to be refused due to lack of funding for course fees, accommodation, travel or supply teacher cover. Remoteness from the Central Belt was seen to exacerbate this issue.

The lack of effective support from the LA

Teachers in all schools saw the need for an LA science officer/advisor who should be well placed to identify expertise and help coordinate, communicate and share this with others. Teachers also thought LA science officers/advisors would be able to identify and communicate available PL opportunities, this currently being seen by many to be somewhat haphazard. Therefore, the lack of a science officer/advisor in any of the LAs was seen to be a barrier to improving PL and more effective working of LA subject networks.

Accountability

Accountability procedures for PL, both local in terms of schools and LAs and nationally in terms of the GTCS and its five yearly Professional Update process (GTCS Citationn.d.), were seen to be inefficient and time-consuming. This ironically resulted in time taken away from effective PL and was also a disincentive for some to engage in PL. Although some saw the completion of evaluation and Professional Update as a useful process for themselves, others saw it as a top-down quality assurance process which was largely not acted upon. The LAs, and Education Scotland, which is both the national inspection and support agency, retain a relationship which has a quality assurance and accountability element as well as a supportive PL one with schools and teachers. A teacher commented:

It feels like there is ‘Big Brother’ even if there is no-one actually watching, and this is not an appropriate manner to treat professionals. (Teacher 61)

Teachers in some of the focus groups indicated they had very little direct contact with LA central staff, did not know their remits, did not know if there was anyone tasked with supporting their PL, and doubted the capacity of the LA to provide such support, especially in subject-specific matters.

Lack of PL leadership, facilitation or coordination within and between schools

Changes to the range of promoted posts in recent years was widely recognised as a disincentive for many to undertake PL. Many staff saw the removal of Chartered TeacherFootnote3 (CT), again for financial reasons, as a retrograde step which disincentivised teachers wishing to remain in the classroom from undertaking PL to a Masters level, by removing an important source of extrinsic motivation. Similarly, the removal of Assistant Head of Department (APT) and Head of Department (PT) posts was considered to be detrimental with a loss of subject expertise in many schools. The jump from being an unpromoted teacher to a Head of Faculty (HoF) was thought to be too large and resulted in the HoF post being one involving too much administration and insufficient opportunity to lead teaching and learning. Having subject leadership more distributed across APT and PT posts was considered to better allow teachers to focus on the leadership of teaching and learning as well as complete the inevitable administration involved.

Many teachers commented on the provision of PL being disjointed, perhaps an indication of too much PL being delivered at teachers from above. Many also commented on the lack of consultation and choice in the use of school in-service days and the lack of explanation or a rationale being given for the PL provided on such occasions. Teachers commented on much of the PL provided for them resulting in the feeling of bouncing from one initiative to the next with little or no opportunity for consolidation or for an opportunity to evaluate whether the PL actually met teachers’ needs. Furthermore, whole-school in-service day activities were generally rated poorly. Many commented on SLT members and LA staff being removed from the realities of teaching and presenting poorly organised and structured sessions in a top-down fashion. Teachers felt they were frequently being told to do things without understanding why.

Whether schools, faculties or departments were seen to operate as effective PLCs depended on the culture of the school and the relationships between the teachers involved, and while this was good in some schools and departments it was less so in others.

Discussion

The findings identified a considerable amount of PL that was valued by these teachers but also some serious and significant barriers to PL. Many of the issues described by science teachers across the north of Scotland are very similar to those described by Tytler et al. (Citation2011) in their article describing the circumstances of subject-based mathematics and science teachers in rural northern Victoria in Australia, a drive of several hours from Melbourne, the main population centre of the state. The discussion takes the findings above and explores these through the issues and challenges Tytler et al. raise in their study of rural communities in Australia which resonate significantly with this study’s findings.

The tension between generic and subject-specific professional learning provision

Tytler et al. (Citation2011, 876) identified the tension between generic and subject-specific PL as one of the main concerns for secondary teachers in rural Australia. This is also the case for the teachers in this study. As can be seen above, the teachers interviewed valued highly PL opportunities with their departmental colleagues and also the subject-specific PL from the likes of SSERC and IOP. Organisations such as SSERC and the IOP provided support in areas like practical work in physics, with its associated health and safety implications, therefore it is unsurprising that this sort of PL, so firmly embedded in the context of the subject, is rated so highly by teachers. This is consistent with one of the criteria for PL programmes to achieve their full potential identified by Cordingley et al. (Citation2015, 18) and CUREE (Citation2018): that both subject knowledge and subject-specific pedagogy be considered together. Likewise PL which integrates knowledge and skills is a principle for effective PL identified by Timperley (Citation2008, 11).

Whilst having concerns about the operation of LA subject networks, there was nevertheless a desire to see them become more effective through a greater focus on subject-based teaching and learning with good leadership and facilitation. This contrasted with the negative views displayed towards much generic and less context-specific PL and the PL often available during events such as whole-school in-service days. This is consistent with the findings of CUREE (Citation2018, 20), where subject-specific PL was valued and sought after much more strongly by class teachers than senior leaders in schools.

Collaboration and discourse communities

Our findings show that teachers in all focus groups exhibited a desire to collaborate with others, both formally and informally, a principle for effective PL described by Timperley (Citation2008, 19) and Cordingley et al. (Citation2015, 28). All focus groups interviewed valued collaboration with KOs from outside their immediate environment, another principle identified by Timperley (Citation2008, 20), and sought greater contact, even if struggling to identify the best sources to meet their needs. The KOs were sought to input new ideas, facilitate PL and bring an element of challenge.

It was also recognised that it was appropriate for any teacher to be a member of several discourse communities, as described by Tytler et al. (Citation2011, 877) and, as seen above, the department being one discourse community, particularly for PL with colleagues possessing other subject expertise when teachers were working outside their subject specialism. The research of McNicholl, Childs, and Burn (Citation2013) demonstrated the significance of having such people accessible in a secondary school department and the importance of having a site, such as a departmental base, to facilitate the informal PL which is so valued by teachers. The identity of teachers in secondary school as subject specialists has long historical and cultural roots. The organisation of secondary schools into departments or faculties is a universal phenomenon (Siskin Citation1994, 9), and these act as ‘communities of practice’ (Wenger Citation1998) or ‘discourse communities’.

Despite usually identifying with their subject and department first, consistent with Siskin (Citation1994) and Brooks (Citation2016), teachers saw the benefits of the whole school, or the cluster of secondary school and its associated primary schools, working together as a second discourse community and were positively disposed to the concept of cross-curricular PLC/TLC even if their experiences of the implementation of these had been disappointing in the past. There is clear potential for the further development of this discourse community, although this is challenging in secondary schools because, as Tytler et al. (Citation2011) acknowledge, teachers’ identities are intricately bound up in their subject:

Secondary teachers’ identities are seen to be grounded in their knowledge and appreciation of the subject. Further their view of the subject is linked to their knowledge of what it means to teach it. (877)

A third potential discourse community across LAs or appropriate geographical regions has yet to be fully realised, despite the desire to see effective subject networks across LAs. A potential fourth discourse community is the wider community in which a school sits. This was not considered to any significant extent in this study. Many teachers are members of at least four fairly well-defined overlapping discourse communities.

The overlapping but different agendas of the major stakeholders in teacher professional learning

Teachers and schools are subject to a mixture of not necessarily well-aligned competing policy agendas: national; LA; school; department; and individual. Gilchrist (Citation2018) describes the traditional LA approach to PL for teachers in a rural LA in the south of Scotland as:

a mish-mash of different activities that teachers opted in or out of, or which were imposed on us from outside by our local authority, and which usually changed on a yearly basis, or when we got a new Director of Education. (69)

The teachers in this study made similar comments regarding the lack of clear vision or leadership for PL in their LA or school and the frequent lack, or poor communication, of any justification of why certain courses of action were taken. In many cases a lack of consultation or involvement in decision making around PL resulted in the experience of a top-down, transmissive approach to much LA-provided PL. It lacks the active leadership identified as one of the principles for effective PL by Timperley (Citation2008, 22).

Comments such as the one made by a teacher referring to ‘Big Brother’ are echoed by Gilchrist (Citation2018) when describing submitting his School Improvement Plan to his LA:

it was submitted just before the start of our summer break, which meant no one could challenge anything in it until we returned in August, that is if anyone actually bothered to read these plans at all. (89)

It was clear that teachers in all LAs wished to see a better alignment of national, LA and school policy and a coherent approach to PL which would be consistent with the characteristics for effective PL described by Cordingley et al. (Citation2015). Cordingley et al. (Citation2015, 16) reported that positive PL environments, sufficient time and a consistency with participants’ wider context were all more important than whether teachers were conscripted or had volunteered to take part in PL. This was reflected in the comments of teachers who all held positive dispositions towards PL with what they considered worthwhile content (Timperley Citation2008, 10). Such PL is well focused on teaching and learning, aimed at improving pupil outcomes (Timperley Citation2008, 8) and firmly embedded in their context. Resentment and negativity occurred when teachers felt conscripted and being told what to do with little explanation or apparent benefit to teaching and learning.

As a Head Teacher who wished to align the PL of his staff to their needs and to build their teacher agency through practitioner enquiry, Gilchrist (Citation2018, 46) describes the importance of a Head Teacher ‘gate-keeping’ on behalf of their teachers to protect them from the ‘initiativitis’ and competing demands of others and the ‘constant barrage of change and interference, most of which is imposed from above them in the hierarchies that still exist in most systems and many schools’.

Remoteness and rurality

Remoteness from the Central Belt of Scotland, see , is a more significant issue than rurality in this study. There was a general willingness on the part of many teachers in the schools in the rural areas to meet for twilight sessions with teachers from nearby schools, issues such as child-care notwithstanding, provided the purpose was worthwhile.

In Scotland most schools have more than one teacher in each of the three sciences within their science faculties. The issues described by Tytler et al. (Citation2011, 877) in Australia and Hargreaves, Parsley, and Cox (Citation2015) in the Pacific Northwest regarding the isolation of individual subject specialists in very small schools, or teachers having to teach outside their specialism, do not occur widely. However, there were nevertheless concerns regarding the attraction of sufficient numbers of teachers, especially experienced teachers, in subjects such as physics to more remote areas and about the availability of suitable supply cover teachers. The recent trend in many LAs to replace the three PTs of biology, chemistry and physics with a single PT of science was seen as a disincentive to attracting experienced members of staff in all three sciences to more remote schools where recruitment and retention can be an issue (Seith and Hepburn Citation2017). This has the effect of reducing the likelihood of there being good KOs in all three subject disciplines for non-specialist teachers to draw upon, especially for the informal day-to-day PL valued so highly by teachers in this study.

On a positive note, the findings show that the use of electronic communication such as the subject-based email fora gave all science teachers the ability to discuss subject matters with colleagues from across the country and ready access to a variety of KOs, reducing the effects of distance compared to previous generations of teachers.

Recruitment and retention of teachers in subjects such as physics to remote areas is an ongoing issue. It has been shown that the provision of good-quality subject-specific PL can reduce the numbers of teachers leaving the profession (Allen and Sims Citation2017), but also in small schools working under difficult circumstances there is a tendency for more generic PL to be used rather than subject-specific PL (CUREE Citation2018). There is a need to improve the awareness of LA and school leaders of the benefits subject-specific PL may bring to recruitment and retention of teachers in shortage-subjects in remote areas as well as to the quality of teaching and learning.

Conclusions

A clear outcome from the research described in this article is that the remoteness from the main sites where much teacher PL occurs, or is perceived to occur, is a greater issue than rurality in terms of teachers accessing certain types of PL and the support of suitable KOs. This finding is consistent with, but also has a subtle difference in emphasis compared to, those of Tytler et al. (Citation2011) in Australia and Hargreaves, Parsley, and Cox (Citation2015) in the Pacific Northwest.

Despite considerable efforts to simplify national curriculum and assessment guidance since the OECD review of Scottish education (Hargreaves et al. Citation2015), teachers in Scotland continue to receive conflicting policy messages. They are encouraged to exercise teacher leadership and teacher agency, but simultaneously accountability and performativity agendas act against this. Despite this, in all the schools visited there is a strong desire by teachers to undertake effective PL and to grow as professionals.

Subsequent to this study, and informed by its findings, SSERC introduced a ‘blended learning’ approach to some of its PL provision with a mix of face-to-face and online learning, and the IOP Teacher Network has started delivering PL online, giving improved equity of access to those in remote areas. Time will tell whether the new Regional Improvement Collaboratives (RICs) will improve the collaborative working of Scottish teachers, help facilitate the PL they desire and impact positively on pupil attainment and achievement. LAs should be well placed to do this at the moment, but this study would indicate they are not functioning as well as they ought, despite being on a scale more likely to enable groups of subject specialists to collaborate both virtually and face to face than an, RIC. However, an RIC may be able to provide specialist support the smaller LAs currently do not have the capacity to deliver. The Northern Alliance RIC, which covers a vast geographical area of Scotland, 58% of its total land area (Scottish Government Citation2017b, 24), would appear to run the risk of being another layer in a hierarchical structure on the wrong geographical scale to fulfil the needs of the teachers in this study.

It is much more likely that an approach more akin to that described by Gilchrist (Citation2018) in his book Practitioner Enquiry will improve teaching and learning and the achievement and attainment of their pupils. In this scenario teachers are protected from competing demands and interference from above and, working in small groups, allowed to focus, with input from appropriate KOs, on evidence- and research-informed PL firmly embedded in their context. Genuine teacher agency can occur as a result. It appears that the protection of sufficient time to do this is a significant barrier and will require a change in mind-set for many at various leadership levels as well as for many teachers themselves. However, as is very clear from both Cordingley et al. (Citation2015) and CUREE (Citation2018), improvements will be best achieved through a focus on subject-specific PL. If this is implemented well, perhaps the wish of one teacher interviewed will be met, and he will be:

trained to within an inch of my life. (Teacher 53)

Next steps and further study

The research described here was the first phase of a longer study into the effective PL of teachers of physics in the northeast of Scotland. The findings helped shape the next phase of the study, which involved the lead author working with teachers in a relatively remote area to develop a discourse community of subject teachers across an LA. This includes research into the role of KOs in supporting and facilitating a network of teachers and providing PL which meets their needs. This article also raises the questions around how remoteness and rurality are defined and used in relation to different types of activities and in different jurisdictions, not only Scotland and Australia but similar areas in North America, Scandinavia and New Zealand, for example.

Appendix

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stuart Farmer

Stuart Farmer. Before taking up his current post of Education Manager for the Institute of Physics in Scotland, Stuart Farmer taught physics in Scottish secondary schools for almost 35 years. During this time, he was involved in a wide range of professional activities including curriculum and assessment development, pre-service and in-service teacher education, science engagement and providing independent advice on science and education to government via several advisory committees. Stuart’s research interests include improving the effectiveness of the professional learning of science teachers, and the resourcing of practical science in schools.

Ann Childs

Ann Childs is an Associate Professor in Science Education at Oxford University, where she teaches on the Postgraduate Certificate in Education and directs and teaches on the Masters in Teacher Education as well as supervising a number of PhD students. Her recent research interests and writing have been in policy work on teacher education in England, and she had been involved in a two-year project, ‘Closing the Gap: Test and Learn’, with partners from the National College of Teaching and Leadership, Education Development Trust, CUREE and Durham University, which resulted in an edited book. Currently she is working on two research projects, the first on the assessment of practical work in England funded by the Wellcome Trust and another project funded by Templeton on developing school students’ argumentation practices through the collaboration of science and religious education teachers in secondary schools in England. She is currently joint editor of the Journal of Research in Science and Technology Education.

Notes

1. Typical journey times were determined using AA Route Planner, http://www.theaa.com/route-planner/classic/planner_main.jsp.

2. TeachMeets are non-commercial teacher sharing events organised ‘by teachers, for teachers’ consisting of short 2- or 7-minute presentations. Pedagoo events are similar to TeachMeets but with longer presentations or learning conversations typically of 30 or 40 minutes’ duration.

3. Chartered Teacher status was introduced in Scotland in 2001 to reward teachers who wished to stay in the classroom rather than take up a management position with an increased salary, but it was dependent on their completing a Masters-level education qualification. This arrangement was terminated in 2012 as part of a review of teachers’ salaries and conditions.

References

- Allen, R., and S. Sims. 2017. Improving Science Teacher Retention: Do National STEM Learning Network Professional Development Courses Keep Science Teachers in the Classroom? London: Wellcome Trust.

- Azano, A. P., and T. T. Stewart. 2016. “Confronting Challenges at the Intersection of Rurality, Place, and Teacher Preparation: Improving Efforts in Teacher Education to Staff Rural Schools.” Global Education Review 3 (1): 108–128.

- Bolam, R., A. McMahon, L. Stoll, S. Thomas, and M. Wallace. 2005. Creating and Sustaining Effective Professional Learning Communities. Bristol: University of Bristol.

- Brooks, C. 2016. Teacher Subject Identity in Professional Practice: Teaching with a Professional Compass. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Cordingley, P., M. Bell, B. Rundell, D. Evans, and A. Curtis. 2003. “The Impact of Collaborative CPD on Classroom Teaching and Learning. Review: How Does Collaborative Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers of the 5-16 Age Range Affect Teaching and Learning?” Research Evidence in Education Library, i–113.

- Cordingley, P., M. Bell, D. Evans, and A. Firth. 2005. “The Impact of Collaborative CPD on Classroom Teaching and Learning. Review: What Do Teacher Impact Data Tell Us about Collaborative CPD?” Research Evidence in Education Library, i–147.

- Cordingley, P., S. Higgins, T. Greany, N. Buckler, D. Coles-Jordan, B. Crisp, and R. Coe. 2015. Developing Great Teaching: Lessons from the International Reviews into Effective Professional Development. London: Teacher Development Trust.

- CUREE. 2018. Developing Great Subject Teaching: Rapid Evidence Review of Subject-Specific CPD in the UK. London: Wellcome Trust.

- Darling-Hammond, L., M. E. Hyler, and M. Gardner. 2017. Effective Teacher Professional Development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- Donaldson, G. 2010. Teaching Scotland’s Future: Report of a Review of Teacher Education in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Donohoo, J., and M. Velasco. 2016. The Transformative Power of Collaborative Inquiry: Realizing Change in Schools and Classrooms. London: Corwin.

- Fazio, X., and W. Melville. 2008. “Science Teacher Development Through Collaborative Action Research.” Teacher Development 12 (3): 193–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530802259222.

- Fullan, M., and A. Hargreaves. 2016. Bringing the Profession Back In. Oxford, OH: Learning Forward.

- Gilchrist, G. 2018. Practitioner Enquiry: Professional Development with Impact for Teachers, Schools and Systems. Abingdon: Routledge.

- GTCS (General Teaching Council for Scotland). 2012a. The Standard for Career-Long Professional Learning: Supporting the Development of Teacher Professional Learning. Edinburgh: General Teaching Council for Scotland.

- GTCS (General Teaching Council for Scotland). 2012b. The Standards for Registration: Mandatory Requirements for Registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland. Edinburgh: General Teaching Council for Scotland.

- GTCS (General Teaching Council for Scotland). n.d. “Professional Update.” Accessed 11 November 2019. http://www.gtcs.org.uk/professional-update/professional-update.aspx

- Guskey, T. R. 1999. “Apply Time with Wisdom.” Journal of Staff Development 20 (2): 10–15.

- Hargreaves, A., D. Parsley, and E. K. Cox. 2015. “Designing Rural School Improvement Networks: Aspirations and Actualities.” Peabody Journal of Education 90 (2): 306–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2015.1022391.

- Hargreaves, A., H. Timperley, M. Huerta, and D. Instance. 2015. Improving Schools in Scotland: An OECD Perspective. Paris: OECD.

- Hargreaves, A., and R. Dawe. 1990. “Paths of Professional Development: Contrived Collegiality, Collaborative Culture, and the Case of Peer Coaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 6 (3): 227–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(90)90015-W.

- Hargreaves, A. 2003. Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity. New York: Teachers College.

- Harris, A., M. S. Jones, and J. B. Huffman. 2017. Teachers Leading Educational Reform: The Power of Professional Learning Communities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kaden, U., P. P. Patterson, J. Healy, and B. L. Adams. 2016. “Stemming the Revolving Door: Teacher Retention and Attrition in Arctic Alaska Schools.” Global Education Review 3 (1): 129–147.

- Kennedy, A. 2011. “Collaborative Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers in Scotland: Aspirations, Opportunities and Barriers.” European Journal of Teacher Education 34 (1): 25–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2010.534980.

- Kitchenham, A., and C. Chasteauneuf. 2010. “Teacher Supply and Demand: Issues in Northern Canada.” Canadian Journal of Education 33 (4): 869–896.

- Korthagen, F. A. J., and J. P. A. M. Kessels. 1999. “Linking Theory and Practice: Changing the Pedagogy of Teacher Education.” Educational Researcher 28 (4): 4–17.

- Lewis, C., R. Perry, and A. Murata. 2006. “How Should Research Contribute to Instructional Improvement? The Case of Lesson Study.” Educational Researcher 35 (3): 3–14.

- Lieberman, A., C. Campbell, and A. Yashkina. 2017. Teacher Learning and Leadership of, by, and for Teachers. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lock, G., J.-A. Reid, B. Green, W. Hastings, M. Cooper, and S. White. 2009. “Researching Rural-Regional (Teacher) Education in Australia.” Education in Rural Australia 19 (2): 31–44.

- Mawhinney, L. 2010. “Let’s Lunch and Learn: Professional Knowledge Sharing in Teachers’ Lounges and Other Congregational Spaces.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (4): 972–978. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.039.

- McNicholl, J., A. Childs, and K. Burn. 2013. “School Subject Departments as Sites for Science Teachers Learning Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” Teacher Development 17 (2): 155–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2012.753941.

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., W. B. Dickinson, N. L. Leech, and A. G. Zoran. 2009. “A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (3): 1–21.

- Priestley, M. 2017. “Regional Improvement Collaboratives: A New Strengthened Middle in Scottish Education?” June 27. https://mrpriestley.wordpress.com/2017/06/27/regional-improvement-collaboratives-a-new-strengthened-middle-in-scottish-education/

- Rhodes, C., and S. Beneicke. 2002. “Coaching, Mentoring and Peer-Networking: Challenges for the Management of Teacher Professional Development in Schools.” Journal of In-Service Education 28 (2): 297–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580200200184.

- SCEL (Scottish College for Educational Leadership). n.d.-a. “Scottish College for Educational Leadership.” Accessed 1 September 2018. http://www.scelscotland.org.uk/

- SCEL (Scottish College for Educational Leadership). n.d.-b. “Teacher Leadership Framework.” Accessed 1 September 2018. http://www.scelscotland.org.uk/what-we-offer/teacher-leadership/

- Scottish Government. 2017a. Education Governance – Next Steps: Executive Summary. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2017b. Empowering Schools: A Consultation on the Provision of the Education (Scotland) Bill. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2018. “Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification.” Accessed 18 January 2019. https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/About/Methodology/UrbanRuralClassification

- Seith, E., and H. Hepburn. 2017. “Councils Demand Powers to Tackle Teacher Shortage.” Tes Magazine. https://www.tes.com/news/tes-magazine/tes-magazine/councils-demand-powers-tackle-teacher-shortage

- Shulman, L. S. 1986. “Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching.” Educational Researcher 15 (2): 4–14.

- Shulman, L. S. 1987. “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 57 (1): 1–22.

- Siskin, L. S. 1994. Realms of Knowledge: Academic Departments in Secondary Schools. Abingdon: Falmer Press.

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, and S. Thomas. 2006. “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change 7: 221–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Timperley, H., A. Wilson, H. Barrar, and I. Fung. 2007. Teacher Professional Learning and Development Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Education.

- Timperley, H. 2008. Teacher Professional Learning and Development. Brussels: IBE.

- Tytler, R., D. Symington, L. Darby, C. Malcolm, and V. Kirkwood. 2011. “Discourse Communities: A Framework from Which to Consider Professional Development for Rural Teachers of Science and Mathematics.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (5): 871–879. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.02.002.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilkinson, D., and P. Birmingham. 2003. Using Research Instruments: A Guide for Researchers. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Williams, A., S. Prestage, and J. Bedward. 2001. “Individualism to Collaboration: The Significance of Teacher Culture to the Induction of Newly Qualified Teachers.” Journal of Education for Teaching 27 (3): 253–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02607470120091588.

- Williams, A. 2003. “Informal Learning in the Workplace: A Case Study of New Teachers.” Educational Studies 293 (2–3): 207–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690303273.