Abstract

Well-owners are exposed to substantial health risks but rarely test their water and infrequently maintain their wells. We designed and tested an intervention aimed to promote voluntairy risk detection behavioiur. The intervention was based on a trending social norm message (suggesting an increasing trend of well-owners testing their wells) with emotional appeals. Two emotional appeals were used: fear frames (an indication of the severity of the risk) and worry appeals (indication of how many well-owners worried about contamination risks). In an online experiment, 262 Irish private well-owners were randomly allocated to six different risk communication messages that followed the design described above. The results showed a trending social norm message combined with a strong worry appraisal primarily raised levels of worry which, in turn, influenced attitudes towards water testing and behavioural intentions to maintain wells. Our results illustrate the potential of stressing a trending social norm and worry appraisal to promote voluntary risk detection behaviours.

Introduction

Many health policies rely on promoting voluntary behaviour such as risk detection behaviour and screening, as these are cost-effective, and they promote commitment and responsibility for one’s own health. However, interventions aimed at changing voluntary behaviour often have limited effects if targeted at a broad audience (Keller and Lehmann Citation2008; Snyder et al. Citation2004). In many cases, changing voluntary risk detection behaviour is especially difficult when only a minority engages in this behaviour, implying that there is no social norm to guide their behaviour (Schultz et al. Citation2018; Stok et al. Citation2012). The contribution of this paper is the development and test of an intervention strategy that could promote voluntary risk detection behaviour in a weak social norm context. As a case in point, the focus is on private well-owners’ detection behaviour of the potential contamination of their drinking water supply. This is a known health risk area where the uptake of water testing and management is low (indicating a weak social norm), despite the existence of real health risks (Flanagan, Marvinney, and Zheng Citation2015; Geiger and Eshet Citation2011; Hooks, Schuitema, and McDermott Citation2019; Hynds, Misstear, and Gill Citation2013).

In rural areas across the world people rely on private wells to provide them with drinking water. Private wells are known to be susceptible to bacterial contamination from the land surface, for example due to anthropogenic activities such as the run-off from processing, agricultural land use, and waste-water systems. Well water can also pose serious health risk from natural or geogenic contamination (e.g., arsenic, uranium, nickel, chromium), which arises from the interaction of groundwater with rocks and minerals in the sub-surface (Ayotte, Gronberg, and Apodaca Citation2011; Rao and Mamatha Citation2004). The estimates of private wells that contain at least one hazardous element at a concentration that exceeds health regulations and guidelines vary from 13% in the US (Ayotte, Gronberg, and Apodaca Citation2011) to 30% in Bangladesh (Ahmad, Khan, and Haque Citation2018) and 30% in Ireland (EPA Citation2020). Drinking contaminated water can have acute health effects, such as vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea, however, consistent exposure to toxic chemicals via groundwater can have more long-term effects too such as diabetes, pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular diseases (WHO Citation2018). Also, several types of cancer have been associated with long-term exposure to arsenic, one of the most prominent natural contaminants in groundwater-derived drinking water (Smith, Lingas, and Rahman Citation2000).

Unlike public water suppliers, private well-owners are usually not legally obliged to test their drinking water quality to ensure compliance with drinking water regulations (US EPA Citation2019). Thus, well-owners are largely responsible for the overall management of their own drinking water systems including well drilling, maintenance, water quality management, and water testing. Despite recommendations to test their well water on a regular basis for contaminants (EPA & WHO Citation2002; US EPA Citation2019), private well-owners rarely do so. They tend to test their water on an ad-hoc basis, that is, as a one-off or if issues arise (Flanagan, Marvinney, and Zheng Citation2015; Hooks, Schuitema, and McDermott Citation2019; Hynds, Misstear, and Gill Citation2013; Imgrund, Kreutzwiser, and de Loë Citation2011; Kreutzwiser et al. Citation2011).

Most campaigns to encourage well-owners to test their water and maintain their wells on a regular basis focus on information provision, that is, they inform people about the risks and what may be done to minimise these (e.g., Islam et al. Citation2011). While this may stimulate people to search for more information and increase their knowledge, it often does not change their behaviour in the desired direction (Huurne and Gutteling Citation2008). Some have argued this is because private well-owners generally do not perceive large risks (Flanagan, Marvinney, and Zheng Citation2015; Hanchett et., 2002; Jones et al. Citation2006), whilst others argue that a lack of worry explains why messages are not very effective (Morris, Wilson, and Kelly Citation2016; Schuitema, Hooks, and McDermott Citation2020; Syme and Williams Citation1993).

In this paper, we present an intervention study that was designed to test if enhancing risk perceptions and/or worry would be most effective in affecting well-owners’ attitudes to well water testing and well maintenance intentions. This intervention includes the use of a trending social norm (TSN) message, which was included to take the weak social norm around well water testing and maintance into consideration..

Intervention design

Trending social norms

One noticeable feature among well-owners is that relatively few well-owners test their water (Flanagan, Marvinney, and Zheng Citation2015; Hynds, Misstear, and Gill Citation2013; Imgrund, Kreutzwiser, and de Loë Citation2011; Kreutzwiser et al. Citation2011), which indicates that there is weak social norm around water testing (Hooks, Schuitema, and McDermott Citation2019). Social norms are defined as ‘rules that are understood by members of a group, and that guide/constrain human behaviour’ (Cialdini and Trost Citation1998, 152). They essentially act as cues for people in social situations surrounding what actions are (dis)approved or expected within society (Cialdini and Goldstein Citation2004). People tend to comply with social norms when existing social norms are strong (Schultz et al. Citation2018). However, when social norms are weak, it is difficult to encourage behaviour change.

An emerging line of research suggests that in case of a weak existing social norm, the use of trending (also referred to as dynamic) social norms may be an effective way to change people’s behaviours (De Groot Citation2022; De Groot, Bondy, and Schuitema Citation2021; Loschelder et al. Citation2019; Mortensen et al. Citation2017; Sparkman et al. Citation2021; Sparkman and Walton Citation2017). TSN refer to information about how other people’s behaviour changes over time. As such, despite a weak social norm, one may indicate that the trend of a social norm is gradually changing in the desired direction. Mortensen et al. (Citation2017) found that while brushing teeth more people reduced their water consumption after reading a TSN message, compared to a descriptive social norms message (i.e., emphasising that a minority engages in certain behaviour). Similar results were found in studies on reducing meat consumption (Sparkman et al. Citation2021; Sparkman and Walton Citation2017). As there is a weak social norm to test and frequently maintain private well, we used a TSN message as a starting point for our intervention design and combined this with emotional appeals.

Emotional appeals

Emotional appeals have long been used in health communication campaigns, which aim to arouse specific emotional responses, such as fear, guilt, or pleasure, which in turn may lead to changes in health behaviours (for reviews see Cameron and Chan Citation2008; Nabi Citation2015; Yousef, Rundle-Thiele, and Dietrich Citation2023). However, there are various reasons why emotional appeals fail at doing so. For example, if the audience’s involvement is low, an emotional response is not likely to occur (Turner Citation2012) or they feel in control over risks (Hooks, Schuitema, and McDermott Citation2019; Nordgren, Van der Pligt, and Van Harreveld Citation2007). This is likely to be the case for well-owners, as they are found to have low risk perceptions (Flanagan, Marvinney, and Zheng Citation2015; Hanchett et al. Citation2002; Hooks, Schuitema, and McDermott Citation2019; Jones et al. Citation2006) and are not very worried (Morris, Wilson, and Kelly Citation2016; Schuitema, Hooks, and McDermott Citation2020; Syme and Williams Citation1993).

Conceptually, perceived risks and worry are related, but distinct concepts. The perception of risk is conceptualised as an assessment of the likelihood that there will be harm (Brewer et al. Citation2007; Loewenstein et al. Citation2001; Sjöberg Citation1998; Weinstein Citation1999). In this definition, two dimensions underpin the perceived risks, that is, an assessment of the likelihood that some sort of harm will occur (‘likelihood of harm’) and an assessment of the consequences of risks (‘consequences of harm’). Thus, risk perceptions are a cognitive process in which the likelihood of a risk (e.g., how likely is it that my drinking water is contaminated?) and its consequences (e.g., how ill would I get if I drank contaminated water) are assessed.

Worry is originally also perceived as a cognitive process, that is, as a process that describes a gradual involvement with external threats due to its relevance to some anxiety-inducing content (Breznitz Citation1971). Tallis and Eysenck (Citation1994), for example, propose that worry is the relatively automatic response to the evaluation of a thread in terms of its imminence, likelihood, and cost set against ones perceived self-efficacy. Here, worry is seen as a cognitive process that influences and informs situations that are perceived as a risk or a threat. Partly in response to this, Loewenstein et al. (Citation2001) propose that worry can also be seen as an emotional response to a risk, which diverges from cognitive evaluations and hasa different impact on risk-taking behaviour (see also Schwartz, Sagiv, and Boehnke Citation2000; Sjöberg Citation1998, Citation2007; Slovic et al. Citation2002). Building on this, worry is increasingly conceputalised as an active emotional state that is linked to an adaptive behavioural response which aims to reduce a particular thread (Van der Linden, 2017; Smith and Leiserowitz Citation2014). In line with this, we consider worry as an emotional state that is the response to a perceived risk.

Research has shown that both risk perceptions and worry can transfer via social networks (Parkinson Citation2011; Parkinson and Simons Citation2009, Citation2012). For example, Hendriks, de Bruijn, and van den Putte (Citation2012) found that the exposure to health messages on binge drinking led to more conversations about the negative effects of alcohol consumption, which in turn increased intentions to refrain from binge drinking. The suggestion that health messages can trigger social conversations about related health risks is based on the idea that emotional appeals can spread through social networks, typically referred to as emotional contagion, and implies that people’s emotions can be influenced by the way others feel (Parkinson Citation2011; Parkinson and Simons Citation2009). As risk perceptions and worry have been pointed out as emotions that can transfer via social networks (Parkinson Citation2011; Parkinson and Simons Citation2009, Citation2012), we designed an intervention that combines a TSN message with emotional appeals that could arouse risk perceptions and worry. The emotional appeals we focus on are fear framing and worry appraisal.

Fear framing (FF)

An overwhelming part of risk communication research focuses on how evoking fear can be used as emotional appeals (Nabi Citation2015). Fear appeals are persuasive messages that attempt to arouse fear by emphasizing the potential danger and harm that will befall individuals if they do not adopt the recommendations (Maddux and Rogers Citation1983). FF is the manipulation of the amount of fear that is aroused, thus the manipulation of the fear levels. Typically, a thread, the size of potential losses, or severity of risks are stressed in a high-fear frame (high-FF) message.

The general assumption is that FF messages cause arousal, which is why risk perceptions (Keller and Lehmann Citation2008; Lu, Xie, and Zhang Citation2013; Slovic Citation1987) and worry (Hine and Gifford Citation1991; Sobkow et al. Citation2020; Tanner et al. Citation2008) will increase. This is because arousal increases people’s motivation to elaborate on the message, and therefore people are more likely to pay attention to the message and ignore other cues and act on it. Consequently, we expect that high-FF messages will increase well-owners’ worry and risk perceptions about contamination levels of their drinking water.

H1: A high-FF message leads to higher levels of worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) compared to a low-FF message.

Worry appraisals (WA)

The term emotional contagion is used to describe how emotions can move from one person to another. It means that the way someone feels can be transferred to other people (Parkinson Citation2011; Parkinson and Simons Citation2012). Worry is an emotional state that was shown to spread in social contexts (Parkinson Citation2011; Parkinson and Simons Citation2012; Schwab, Cullum, and Harton Citation2016), which suggests that feelings of worry can be transferred to other people. Parkinson and Simons (Citation2012) suggested that the transfer of worry across social groups serves as a warning signal to other people and signals that there may be a risk or threat present. Consequently, a health message that stresses that others are worried about a risk (high-WA) may amplify worry and risk perceptions. Hence, we hypothesise that strong-WA messages can raise levels of worry and risk perceptions as follows:

H2: A strong-WA message increases worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) more than a weak-WA or no-WA message

Interaction FF and WA

It can be argued that the intensity of the message depends on the combination of messages: a multiple message, for example sending a TSN message in combination with a high-FF message and strong-WA message would combine all intensifying features. We expect that such a combination would increase the level of arousal, and therefore increase worry levels and risk perceptions:

H3: Worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) increase most under the condition of a high-FF and strong-WA message in comparison to conditions whereby either FF or WA are low/weak.

Worry and risk perceptions as mediators

As described above, we designed our intervention strategy to directly target worry levels and risk perceptions among well-owners. We expect that an increase in worry and risk perceptions, in turn, affect well-owners’ attitudes and behavioural intentions. In other words, we expect that our intervention indirectly influences well-owners’ attitudes and behavioural intentions, with worry and risk perceptions acting as mediators.

H4: Worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) mediate the influence of the WA intervention on well-owners’ attitude to water testing.

H5: Worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) mediate the influence of the FF intervention on well-owners’ attitude to water testing.

H6: Worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) mediate the influence of the WA intervention on well-owners’ behavioural intentions to maintain their wells.

H7: Worry (a) and risk perception (b) mediate the influence of the FF intervention on well-owners’ behavioural intentions to maintain their wells.

Moderated mediation effect: perceived control as moderator

Increasing risk perceptions and worry are only likely to lead to changes in attitudes and behavioural intentions if various preconditions are in place (Milne, Sheeran, and Orbell Citation2000). According to the Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers Citation1975), one important pre-condition is self-efficacy, which refers to the belief in one’s own ability to influence events (Bandura Citation1977). Self-efficacy is very closely related to the concept of perceived control, i.e., one’s perception of how well they are able to perform a given behaviour (Meyerowitz and Chaiken Citation1987; Nordgren, Van der Pligt, and Van Harreveld Citation2007). Previous studies show that well-owners who feel strong control, compared to those who do not, believe that that their water quality is higher and maintain their wells more frequently (Schuitema, Hooks, and McDermott Citation2020). Therefore, for those who feel in control, increasing worry and risk perceptions may lead to more positive attitudes to water testing and well maintenance. Those who perceive low control over contamination risks may not feel capable to act and thus one may expect that when people perceive low levels of control, increased worry levels and risk perceptions will not change their attitudes and behavioural intentions.

As we assume that worry and risk perception are mediators (H4–H7), this implies that there could be a moderated mediation effect (Hayes Citation2015). A moderated mediation effect implies a conditional indirect effect, depending on the value of the moderator. Concretely, we propose that worry and risk perceptions only mediate the influence of the interventions on attitudes and behavioural intentions under the condition that perceived control is high (as opposed to low):

H8: Worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) increase well-owners’ attitude to water testing when perceived control is high as opposed to low.

H9: Worry (a) and risk perceptions (b) do not increase well-owners’ behavioural intentions when perceived control is high as opposed to low.

Method

Procedure and sample

An online panel was used to collect data among 262 private well-owners in Ireland. As there is no registry of the exact number or location of private well-owners in Ireland, a panel study allowed us to pre-screen for private well-owners among the panel. All participants provided consent before filling out the survey and the study was accepted as a low-risk study by the Research Ethics committee of University College Dublin on the grounds that the research was done through anonymous surveys that do not involve the collection of identifiable data or health data. As a result, the research was exempt from seeking full ethics approval.

All respondents lived in rural areas, as that is where private wells are typically used. The mean age category was 45–54 years old. Educational and income levels were lower than the national average, which is common in rural areas. Females were largely overrepresented in our sample (n = 209), which is probably because in rural areas, women are more often involved in panel studies. Attempts to increase the number of male private well-owners largely failed because it was hard to identify male well-owners in the online panel. To investigate whether the overrepresentation of women could have influenced our results, we tested if men and women differed on the variables used in our analyses, and no significant differences were found. We also asked respondents whether they identified as the main householder (202 respondents did (74%); of which 153 were women). We assumed that people who identify as the main householder also had influence on the household decision making process.

Experimental design

There were six experimental conditions following a 2 (FF) by 3 (WA) between-subjects design (sample size per condition ranged between 42 and 46). In all six conditions, respondents saw the same TSN message, which read ‘Research found that 16% of private well-owners tested their water. This has increased from 11% in 2016’.

The manipulation of FF was done by stressing the severity of the health risks. In the high-FF condition, the text read ‘drinking contaminated water can pose serious health risks’ and was accompanied by a red triangle with a with exclamation mark, to stress danger. The low-FF condition was presented as ‘drinking contaminated water can pose some health risks’ and there was no exclamation mark presented.

There were three levels of WA. In the first level WA was not mentioned to create a benchmark. The second level presented a weak-WA message indicated that a minority of well-owners worried about contamination of their wells: ‘Only 20% of private well-owners worry about contamination of their wells’. The last level presented a strong-WA message, indicating that 16% of private well-owners worry about contamination of their wells’.

All messages began with the FF, followed by a WA and TSN message. After this, we provided some advice, which was the same in every condition: ‘You can test your water by contacting your local authority, the health service executive or a number of private water testing facilities’. The message was printed in front of a picture where a hand is pouring water in a glass from a jar. See for an overview of the conditions, the exact order in which the manipulated texts were presented, and the visual presentation of the messages.

Table 1. Overview of experimental design and scenarios.

Variables

For information to be effective in changing people’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours, it is important that they believe the information is realistic and true. To check whether this was the case, we asked respondents to indicate how credible, realistic, and convincing they thought the information was after reading it. We used 5-point binary scales (not very credible/very credible; unreliable/reliable; unconvincing; convincing) to measure this. Next, respondents filled out a survey in which we measured the following variables.

Risk perceptions were measured with 3 items: ‘My water is a health risk’, ‘My water is not suitable for drinking purposes’, and ‘My water is generally free of contaminants [reversed]’. The items formed a reliable scale (α = .78; M = 2.14, SD = .92).

Worry was measured with 4 items, that is, ‘I am not concerned about my water quality [reversed]’, ‘I worry about contamination of my drinking water’, ‘I worry about contamination of my water harming the health of my family’, and ‘I worry about harmful bacteria in my drinking water’ (α = .79; M = 2.09, SD = 1.04).

Perceived control was measured with the items ‘I feel in control of my water quality’, ‘I have the ability to detect my contamination within my water supply’, ‘I am best placed to manage my water quality’, and ‘Contamination of my water is not easy to detect or contain [reversed]’ (α = .74; M = 3.11, SD = 0.83).

Attitudes to water testing was also measured with 4 items: ‘Testing my water is a good way to manage my water quality’, ‘Water testing is a waste of time [reversed]’, ‘Water testing is unnecessary [reversed]’, and ‘Water testing should be done every year’ (α = .78; M = 3.46, SD =0.39).

Behavioural intentions to well management was measured by asking respondent about the likelihood that they would carry out six types of behaviour. Going forward, how likely are you to carry out the following behaviours? ‘I will test my water on a regular basis’, ‘I will seek information on water testing in my area’, ‘I will seek information on drinking water contamination in general’, ‘I will seek more information on the maintenance of my well’, ‘I will seek information on water testing in general’, ‘I will not change my current behaviour at all’ [reversed]. These 6 items formed a reliable scale (α = .71 (M = 3.56, SD = 0.77).

All items were scored on 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), apart from behavioural intentions, which ranged from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely).

Results

Check information quality

All six messages were perceived to be credible (across all 6 messages: M = 3.96; SD = 1.13), realistic (across all 6 messages: M = 3.98; SD = 1.10), and convincing (across all 6 messages: M = 3.84; SD = 1.16). Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) showed no significant differences between the six messages in how credible (F (5, 256) = 0.68, ns), realistic (F (5, 256) = 0.73, ns), or convincing (F (5, 256) = 1.77, ns) the information was. Therefore, we concluded that the messages were generally considered as realistic and true.

Direct and indirect effects of interventions on attitudes and behavioural intentions

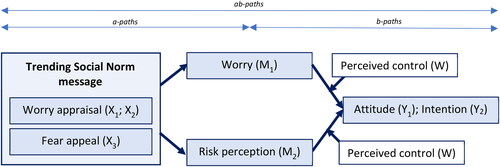

We tested the moderation-mediation model using the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (Citation2013) version three (template 14) to test our hypotheses (see also ). We ran this macro twice with attitudes (Y1) and behavioural intentions (Y2) as dependent variables separately. FF (X3) and WA (X1 and X2) were included as independent variables. FF was used as moderator (X1*X3 and X2*X3) to test the interaction between WA and FF on worry and perceived risks. Worry (M1) and perceived risks (M2) were included as mediators and perceived control as moderator (W) of the effect of worry (W*M1) and perceived risks (W*M2) on the two dependent variables attitudes and behavioural intentions. All results are presented in .

Table 2. Influence of intervention strategies on attitudes and behavioural intentions with risk and worry as mediators and perceived control as moderator.

Effects of interventions on worry and perceived risks (a-paths)

Firstly, we investigated how the FF and WA interventions affected participants worry levels and perceived risks (the a-paths in ; see also ). We found that the high-FF message resulted in increased worry levels compared to the low-FF message (a3_worry = .50, p ≤.05), but no significant effect on perceived risks were found. Hence, H1b was confirmed, whilst H1a was rejected. For the WA intervention, the results showed that both worry (a2_worry= .51, p ≤.05) and risk perceptions (a2_risk= .43, p ≤.05) were higher in the strong-WA condition compared to the average of the other two WA messages. Thus H2 was confirmed.

Next, we investigated if there was an interaction effect of the FF and WA interventions on worry and perceived risks. Specifically, it was hypothesised in H3 that worry and perceived risks would be highest when a TSN message was combined with both the high-FF and strong-WA message as opposed to the other messages. The results did not confirm such an interaction effect of FF and WA on worry or risk perceptions, and thus H3 was rejected.

In summary, the analyses indicated that worry was significantly higher for the strong-WA and high-FF message; risk perceptions were higher for the strong-WA message; and the expected interaction effect of the WA and FF interventions on worry and risk perceptions was not confirmed.

Effects of worry and perceived risks on attitudes and behavioural intentions (b-paths)

H4, H5, H6, and H7 proposed that the effect of the WA and FF interventions on well-owners’ attitudes and intentions were mediated by worry and risk perceptions. To assess if there were such mediation effects, we first looked at how the proposed mediators, worry and perceived risks, influenced attitudes and behavioural intentions (indicated by the b-paths in ; See also ). The results showed that the more well-owners worried about the contamination risks of their wells, the more positive their attitude towards well water testing was (b1_attitude= .22, p ≤.05) and the stronger their behavioural intentions to maintain their wells (b1_intention= .69, p ≤.001). Contrary to the expectations, risk perceptions did not significantly predict attitudes and, unexpectedly, a negative relationship between risk perceptions and behavioural intentions was found (b2_intention= −0.56, p ≤.001). The latter meant that well-owners had weaker intentions to maintain ther wells when they perceived high contamination risks. We believe that this may be explained by the moderating role of perceived control, which we will go into in the next section.

Worry and risk perceptions as mediators (ab-paths)

The next step is to investigate the mediating role of worry and risk perceptions on the influence of the interventions on attitudes and behavioural intentions (indicated by the ab-paths in ; see also ). As expected, worry was found to mediate the effect of the WA message on attitudes to water testing and intentions to well maintenance. Specifically, a strong-WA message led to higher levels of worry, which in turn, resulted in more positive attitudes to water testing (ab2 = .04 [95% CI: .002; .087]; confirming H4a) and intentions to maintain their wells (ab8=.10 [95% CI: .002;.212]; confirming H6a). Worry did not significantly mediate the effect of the FF message on well-owners’ attitudes and behavioural intentions (thus rejecting H5a and H7a), despite the positive effect that the high-FF message had on worry levels. This suggested that the strong-WA message, but not the FF message, increased attitudes and behavioural intentions because it raised the extent to which well-owners’ worried about the quality of their drinking water.

Risk perceptions did not significantly mediate the effect of the WA and FF interventions on attitudes or behavioural intentions and thus H4b, H5b, H6b, and H7b must be rejected. In conclusion, worry, but not risk perceptions was a mediator for the effect of the WA interventions on attitudes and intentions.

Perceived control as moderator (mediation moderation effect)

We expected a moderated mediation effect (H8–H9), meaning that we expected the mediating role of worry and risk perception to depend on the level of perceived control over contamination risks.Footnote1. The analysis did not demonstrate such a mediation moderation effect. When looking at the perceived control as a moderator (indicated by the b-paths in ; see also ), we found that perceived control was a significant moderator in the mediation effect of perceived risks on behavioural intentions (b5_intention= .15, p ≤.001; confirming H9b)Footnote2. However, as risk perception was not a significant mediator, it is no surprise that there was no significant moderation mediation effect found. The remainding mediation moderation effects were not statistically significant either, and therefore we conclude that perceived control did not moderate the mediation effect of worry and risk perceptions on well-owners’ attitudes (rejecting H9) behaivoural intentions (rejecting H8).

Conclusion and discussion

We designed and tested an intervention that aimed to encourage voluntary risk detection behaviours by tailoring it to its social context. Specifically, we aimed to encourage positive attitudes and well maintenance intentions among private well-owners, for which there is generally a weak social norm. We found that a TSN message (i.e., stressing that an increasing number of well-owners tested their water) combined with a strong-WA message (i.e., stressing that a majority of well-owners worried about contamination risks) indirectly influenced attitudes and behavioural intentions because it raised worry levels among well-owners. Thus, worry, but not risk perceptions, mediated the effect of the WA intervention on attitudes and behavioural intentions. This is line with other studies who found that worry was the main predictor of voluntary health risk detection or prevention behaviours. This was for example found for genetic testing for health risks (Cameron and Reeve Citation2006), cancer screening (Cameron Citation2008; Janssen et al. Citation2013), heart disease risk prevention (Lee et al. Citation2011), smoking (McCaul et al. Citation2007), and COVID-19 prevention behaviours (Sobkow et al. Citation2020). It has been reasoned that worry triggers negative arousal, which is important to stimulate positive attitudes and behavioural intentions (Leventhal Citation1970; Leventhal, Phillips, and Burns Citation2016) as it can enhance information processing (Meijnders, Midden, and Wilke Citation2001), feelings of responsibility to act (Bouman et al. Citation2020), and reduce uncertainty (Smith et al. Citation2007). We believe that our WA intervention may serve as a confirmation of one’s own (latent) worries, which may increase their confidence to act on them and overrule the effects of a weak social norm. Further research should confirm this hypothesis.

The result that worry can encourage voluntary health risk detection behaviour does not mean that we should unrestrictedly aim to raise worry levels. In fact, interventions should only raise worry levels moderately to be effective (Rothman et al. Citation2006). Increasing the extent to which people worry too much may be counterproductive as well as a risky or unethical intervention strategy (see Duke et al. Citation1993 for a comprehensive discussion about the ethical implications). In addition, it is also important that people can act on their worry (Sobkow et al. Citation2020; Tannenbaum et al. Citation2015; Witte and Allen Citation2000) and, for example, have access to knowledge, test facilities and practical advice on which actions can address these concerns.

Our findings further suggest that the use of FF messages is not the most effective way to change attitudes and behaviours of health risk detection behaviours. Although we did see that worry increased when well-owners read the high-FF message, there was no indirect effect on well-owners’ attitudes and behavioural intentions. Our findings contrast with research on health risks that suggests increasing perception of risks as a tool to change people’s attitudes or behaviours towards those risks (Hanchett et al. Citation2002; Hynds, Misstear, and Gill Citation2013; Lund and Helgason Citation2005). Contrary to these studies, we found that stronger risk perceptions reduced the intention to maintain wells.

In sum, our results suggest that interventions based on trending social norms and worry appraisals can raise feelings of worry, which is more effective in promoting voluntary health risk detection than increasing risk perceptions. When designing this type of intervention, caution is needed with its specific wording as boomerang effects can occur (Schultz et al. Citation2007, Citation2018). For example, because we used a TSN message as a baseline in all interventions and combined this with emotional appeals messages, we cannot separate the effect of both messages.

We note that the effect sizes of the interventions were rather small, which is common for interventions based on social influence techniques (Abrahamse and Steg Citation2013). Therefore, we believe that health communication and social influence interventions like ours should be combined with other (policy) measures and changes. In the case of well water management, one may think of facilitating well-owners in managing their wells, for example by providing a (free) water testing service. In addition, when new wells are drilled and constructed there are requirements to adopt current best practices in relation to well-head design that provides protection from surface-derived contaminants and, more broadly, good groundwater governance and management is crucial (Di Pelino et al. Citation2019; Megdal Citation2018).

One caveat of our results is that we had a large overrepresentation of women. Women are known to worry more and perceive risks differently than men (McQueen et al. Citation2008; Sjöberg Citation1998) and be more sensitive to emotional appeals (Dube and Morgan Citation1996). Therefore, our results need to be interpreted with care and we cannot generalise our results to all (male) well-owners. However, gender differences in worry and risk perceptions are typically found in research that focuses on individual risks, like specific illnesses. The risk of well water contamination applies to a household and typically require joint decisions made by household members. Men and women play a different role in such intra-household decisions, but both contribute to them (De Palma, Picard, and Ziegelmeyer Citation2011). As 74% of our sample identify as the main householder, we assume they have influence on household-based decisions around well management, but we have no data support this assumption.

In conclusion, we have shown the potential of an intervention approach to encourage voluntary risk detection behaviours that moderately raises the extent to which people worry about risks. This approach relies on the social context of the behaviour at stake. Specifically, when a social norm to act is weak, stressing a trending social norm in combination with a strong worry appraisal could play a role in the promotion of voluntary risk detection behaviours.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the input of Prof Frank McDermott on earlier drafts of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Note there was a significant main effect of perceived control on attitudes to water testing, implying that well-owners who felt more in control had more positive water testing attitudes. As we did not have specific hypothesis about main effects for perceived control, we do not go further into this effect.

2 Asimple slope analysis revealed that for those who perceived low levels of control, behavioural intentions decreased when risk perceptions were high (β = 0.22, p ≤.01), which was opposite to our expectations. This may be because high risk perceptions in combination with feeling incapable to act (indicated by low perceived control) could result in a type of in-action or paralysis to act. For those who perceived high control, risk perceptions did not influence their intentions to maintain their wells (β = 0.03, ns). Perhaps they felt that they already maintained their wells sufficiently or overly confident in their abilities to detect, monitor and prevent contamination risks.

References

- Abrahamse, W., and L. Steg. 2013. “Social Influence Approaches to Encourage Resource Conservation: A Meta-Analysis.” Global Environmental Change 23 (6): 1773–1785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.029.

- Ahmad, S. A., M. H. Khan, and M. Haque. 2018. “Arsenic Contamination in Groundwater in Bangladesh: Implications and Challenges for Healthcare Policy.” Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 11: 251–261. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S153188.

- Ayotte, J. D., J. A. M. Gronberg, and L. E. Apodaca. 2011. Trace Elements and Radon in Groundwater across the United States, 1992–2003. Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey.

- Bandura, A. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioural Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191.

- Bouman, Thijs, Mark Verschoor, Casper J. Albers, Gisela Böhm, Stephen D. Fisher, Wouter Poortinga, Lorraine Whitmarsh, and Linda Steg. 2020. “When Worry about Climate Change Leads to Climate Action: How Values, Worry and Personal Responsibility Relate to Various Climate Actions.” Global Environmental Change 62: 102061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102061.

- Brewer, N. T., G. B. Chapman, F. X. Gibbons, M. Gerrard, K. D. McCaul, and N. D. Weinstein. 2007. “Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Risk Perception and Health Behavior: The Example of Vaccination.” Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 26 (2): 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136.

- Breznitz, S. 1971. “A Study of Worrying.” British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 10 (3): 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1971.tb00747.x.

- Cameron, L. D. 2008. “Illness Risk Representations and Motivations to Engage in Protective Behavior: The Case of Skin Cancer Risk.” Psychology & Health 23 (1): 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320701342383.

- Cameron, L. D., and C. K. Y. Chan. 2008. “Designing Health Communications: Harnessing the Power of Affect, Imagery, and Self-Regulation.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2 (1): 262–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00057.x.

- Cameron, L. D., and J. Reeve. 2006. “Risk Perceptions, Worry, and Attitudes about Genetic Testing for Breast Cancer Susceptibility.” Psychology & Health 21 (2): 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320500230318.

- Cialdini, R. B., and N. J. Goldstein. 2004. “Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity.” Annual Review of Psychology 55 (1): 591–621. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015.

- Cialdini, R. B., and M. R. Trost. 1998. “Social Influence: Social Norms, Conformity and Compliance.” In The Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by D.T. Gilbert, S.T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, 151–192. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- De Groot, J. I. M. 2022. “The Effectiveness of Normative Messages to Decrease Meat Consumption: The Superiority of Dynamic Normative Messages Framed as a Loss.” Frontiers in Sustainability 3: 968201. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.968201.

- De Groot, J. I. M., K. Bondy, and G. Schuitema. 2021. “Listen to Others or Yourself? The Role of Personal Norms on the Effectiveness of Social Norm Interventions to Change Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 78: 101688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101688.

- De Palma, A., N. Picard, and A. Ziegelmeyer. 2011. “Individual and Couple Decision Behavior under Risk: Evidence on the Dynamics of Power Balance.” Theory and Decision 70 (1): 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-009-9179-6.

- Di Pelino, S., C. Schuster-Wallace, P. D. Hynds, S. E. Dickson-Anderson, and A. Majury. 2019. “A Coupled-Systems Framework for Reducing Health Risks Associated with Private Drinking Water Wells.” Canadian Water Resources Journal/Revue Canadienne Des Ressources Hydriques 44 (3): 280–290.

- Dube, L., and M. Morgan. 1996. “Trend Effects and Fender Differences in Retrospective Judgments of Consumption Emotions.” Journal of Consumer Research 23 (2): 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1086/209474.

- Duke, C. R., G. M. Pickett, L. Carlson, and S. J. Grove. 1993. “A Method for Evaluating the Ethics of Fear Appeals.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 12 (1): 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569501200112.

- EPA & WHO. 2002. Water and Health in Europe. Brussels, Belgium: World Health Organisation European Office.

- EPA. 2020. Ireland’s Environment: An Intergrated Assessment. Wexford, Ireland: Environmental Protection Agency.

- Flanagan, S. V., R. G. Marvinney, and Y. Zheng. 2015. “Influences on Domestic Well Water Testing Behavior in a Central Maine Area with Frequent Groundwater Arsenic Occurrence.” Science of the Total Environment 505: 1274–1281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.017.

- Geiger, B., and Y. Eshet. 2011. “Two Worlds of Assessment of Environmental Health Issues: The Case of Contaminated Water Wells in Ramat ha‐Sharon.” Journal of Risk Research 14 (1): 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.505688.

- Hanchett, S., Q. Nahar, A. Van Agthoven, C. Geers, and M. D. Rezvi. 2002. “Increasing Awareness of Arsenic in Bangladesh: Lessons from a Public Education Programme.” Health Policy and Planning 17 (4): 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/17.4.393.

- Hayes, A. F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analyses: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F. 2015. “An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 50 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

- Hendriks, Hanneke, Gert-Jan de Bruijn, and Bas van den Putte. 2012. “Talking about Alcohol Consumption: Health Campaigns, Conversational Valence, and Binge Drinking Intentions.” British Journal of Health Psychology 17 (4): 843–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02080.x.

- Hine, D. W., and R. Gifford. 1991. “Fear Appeals, Individual Differences, and Environmental Concern.” The Journal of Environmental Education 23 (1): 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1991.9943068.

- Hooks, T., G. Schuitema, and F. McDermott. 2019. “Risk Perceptions towards Drinking Water Quality among Private Well Owners in Ireland: The Illusion of Control.” Risk Analysis: The journal is Risk Analysis 39 (8): 1741–1754. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13283.

- Huurne, E. T., and J. Gutteling. 2008. “Information Needs and Risk Perception as Predictors of Risk Information Seeking.” Journal of Risk Research 11 (7): 847–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870701875750.

- Hynds, P. D., B. D. Misstear, and L. W. Gill. 2013. “Unregulated Private Wells in the Republic of Ireland: Consumer Awareness, Source Susceptibility and Protective Actions.” Journal of Environmental Management 127: 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.05.025.

- Imgrund, Krystian, Reid Kreutzwiser, and Rob de Loë. 2011. “Influences on the Water Testing Behaviors of Private Well Owners.” Journal of Water and Health 9 (2): 241–252. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2011.139.

- Islam, M. A., H. Sakakibara, M. R. Karim, and M. Sekine. 2011. “Evaluation of Risk Communication for Rural Water Supply Management: A Case Study of a Coastal Area of Bangladesh.” Journal of Risk Research 14 (10): 1237–1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2011.574315.

- Janssen, E., L. Van Osch, H. De Vries, and L. Lechner. 2013. “The Influence of Narrative Risk Communication on Feelings of Cancer Risk.” British Journal of Health Psychology 18 (2): 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02098.x.

- Jones, A. Q., C. E. Dewey, K. Doré, S. E. Majowicz, S. A. McEwen, W. T. David, M. Eric, D. J. Carr, and S. J. Henson. 2006. “Public Perceptions of Drinking Water: A Postal Survey of Residents with Private Water Supplies.” BMC Public Health 6 (1): 94–94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-94.

- Keller, P. A., and D. R. Lehmann. 2008. “Designing Effective Health Communications: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 27 (2): 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.27.2.117.

- Kreutzwiser, Reid, Rob de Loë, Krystian Imgrund, Mary Jane Conboy, Hugh Simpson, and Ryan Plummer. 2011. “Understanding Stewardship Behaviour: Factors Facilitating and Constraining Private Water Well Stewardship.” Journal of Environmental Management 92 (4): 1104–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.11.017.

- Lee, T. J., L. D. Cameron, B. Wünsche, and C. Stevens. 2011. “A Randomized Trial of Computer-Based Communications Using Imagery and Text Information to Alter Representations of Heart Disease Risk and Motivate Protective Behaviour.” British Journal of Health Psychology 16 (Pt 1): 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910710X511709.

- Leventhal, H. 1970. “Findings and Theory in the Study of Fear Communications.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, edited by L. Berkowitz, Vol. 5, 119–186. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Leventhal, H., L. A. Phillips, and E. Burns. 2016. “The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): A Dynamic Framework for Understanding Illness Self-Management.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 39 (6): 935–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2.

- Loewenstein, G. F., E. U. Weber, C. K. Hsee, and N. Welch. 2001. “Risk as Feelings.” Psychological Bulletin 127 (2): 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267.

- Loschelder, D. D., H. Siepelmeyer, D. Fischer, and J. A. Rubel. 2019. “Dynamic Norms Drive Sustainable Consumption: Norm-Based Nudging Helps Café Customers to Avoid Disposable to-Go-Cups.” Journal of Economic Psychology 75: 102146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2019.02.002.

- Lu, J., X. Xie, and R. Zhang. 2013. “Focusing on Appraisals: How and Why Anger and Fear Influence Driving Risk Perception.” Journal of Safety Research 45: 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2013.01.009.

- Lund, K. E., and Á. R. Helgason. 2005. “Environmental Tobacco Smoke in Norwegian Homes, 1995 and 2001: Changes in Children’s Exposure and Parent’s Attitudes and Health Risk Awareness.” European Journal of Public Health 15 (2): 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cki075.

- Maddux, J. E., and R. W. Rogers. 1983. “Protection Motivation and Self-Efficacy: A Revised Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 19 (5): 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(83)90023-9.

- McCaul, K. D., A. B. Mullens, K. M. Romanek, S. C. Erickson, and B. J. Gatheridge. 2007. “The Motivational Effects of Thinking and Worrying about the Effects of Smoking Cigarettes.” Cognition & Emotion 21 (8): 1780–1798. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701442840.

- McQueen, A., S. W. Vernon, H. I. Meissner, and W. Rakowski. 2008. “Risk Perceptions and Worry about Cancer: Does Gender Make a Difference?” Journal of Health Communication 13 (1): 56–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730701807076.

- Megdal, S. B. 2018. “Invisible Water: The Importance of Good Groundwater Governance and Management.” NPJ Clean Water. 1 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-018-0015-9.

- Meijnders, A. L., C. J. H. Midden, and H. A. M. Wilke. 2001. “Communications about Environmental Risks and Risk-Reducing Behavior: The Impact of Fear on Information Processing.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 31 (4): 754–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb01412.x.

- Meyerowitz, B. E., and S. Chaiken. 1987. “The Effect of Message Framing on Breast Self-Examination Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52 (3): 500–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.500.

- Milne, S., P. Sheeran, and S. Orbell. 2000. “Prediction and Intervention in Health-Related Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of Protection Motivation Theory.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30 (1): 106–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02308.x.

- Morris, L., S. Wilson, and W. Kelly. 2016. “Methods of Conducting Effective Outreach to Private Well Owners - a Literature Review and Model Approach.” Journal of Water and Health 14 (2): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2015.081.

- Mortensen, C. R., R. Neel, R. B. Cialdini, C. M. Jaeger, R. P. Jacobson, and M. M. Ringel. 2017. “Trending Norms: A Lever for Encouraging Behaviors Performed by the Minority.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 10 (2): 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617734615.

- Nabi, R. L. 2015. “Emotional Flow in Persuasive Health Messages.” Health Communication 30 (2): 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.974129.

- Nordgren, L. F., J. Van der Pligt, and F. Van Harreveld. 2007. “Unpacking Perceived Control in Risk Perception: The Mediating Role of Anticipated Regret.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 20 (5): 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.565.

- Parkinson, B. 2011. “Interpersonal Emotion Transfer: Contagion and Social Appraisal.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 5 (7): 428–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00365.x.

- Parkinson, B., and G. Simons. 2009. “Affecting Others: Social Appraisal and Emotion Contagion in Everyday Decision Making.” Personality and Social Psycholical Bulletin 35 (8): 1071–1084.

- Parkinson, B., and G. Simons. 2012. “Worry Spreads: Interpersonal Transfer of Problem-Related Anxiety.” Cognition & Emotion 26 (3): 462–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.651101.

- Rao, S. M., and P. Mamatha. 2004. “Water Quality in Sustainable Water Management.” Current Science 87 (7): 942–947.

- Rogers, R. W. 1975. “A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change.” Journal of Psychology 91 (1): 93–114.

- Rothman, A. J., R. D. Bartels, J. Wlaschin, and P. Salovey. 2006. “The Strategic Use of Gain- and Loss-Framed Messages to Promote Healthy Behavior: How Theory Can Inform Practice.” Journal of Communication 56 (suppl_1): S202–S220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00290.x.

- Schuitema, G., T. Hooks, and F. McDermott. 2020. “Water Quality Perceptions and Private Well Management: The Role of Perceived Risks, Worry and Control.” Journal of Environmental Management 267: 110654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110654.

- Schultz, P. W., J. M. Nolan, R. B. Cialdini, N. J. Goldstein, and V. Griskevicius. 2007. “The Constructive, Destructive, and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms.” Psychological Science 18 (5): 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x.

- Schultz, P. W., J. M. Nolan, R. B. Cialdini, N. J. Goldstein, and V. Griskevicius. 2018. “The Constructive, Destructive, and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms: Reprise.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 13 (2): 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617693325.

- Schwab, N. G., J. C. Cullum, and H. C. Harton. 2016. “Clustering of Worry Appraisals among College Students.” Journal of Social Psycholy 156 (4): 413–421.

- Schwartz, S. H., L. Sagiv, and K. Boehnke. 2000. “Worries and Values.” Journal of Personality 68 (2): 309–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00099.

- Sjöberg, L. 1998. “Worry and Risk Perception.” Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 18 (1): 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00918.x.

- Sjöberg, L. 2007. “Emotions and Risk Perception.” Risk Management 9 (4): 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.rm.8250038.

- Slovic, P. 1987. “Perception of Risk.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 236 (4799): 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3563507.

- Slovic, P., M. L. Finucane, E. Peters, and D. G. MacGregor. 2002. “The Affect Heuristic.” European Journal of Operational Research 177 (3): 1333–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2005.04.006.

- Smith, J. R., M. A. Hogg, R. Martin, and D. J. Terry. 2007. “Uncertainty and the Influence of Group Norms in the Attitude–Behaviour Relationship.” British Journal of Social Psychology 46 (4): 769–792. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466606X164439.

- Smith, N., and A. A. Leiserowitz. 2014. “The Role of Emotion in Global Warming Policy Support and Opposition.” Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 34 (5): 937–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12140.

- Smith, A. H., E. O. Lingas, and M. Rahman. 2000. “Contamination of Drinking-Water by Arsenicin Bangladesh: A Public Health Emergency.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78 (9): 1093–1103.

- Snyder, L. B., M. A. Hamilton, E. W. Mitchell, J. Kiwanuka-Tondo, F. Fleming-Milici, and D. Proctor. 2004. “A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Mediated Health Communication Campaigns on Behavior Change in the United States.” Journal of Health Communication 9(Suppl. 1): 71–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730490271548.

- Sobkow, A., T. Zaleskiewicz, D. Petrova, R. Garcia-Retamero, and J. Traczyk. 2020. “Worry, Risk Perception, and Controllability Predict Intentions toward COVID-19 Preventive Behaviors.” Frontiers of Psychology 11: 582720.

- Sparkman, G., B. N. J. Macdonald, K. D. Caldwell, B. Kateman, and G. D. Boese. 2021. “Cut Back or Give It up? The Effectiveness of Reduce and Eliminate Appeals and Dynamic Norm Messaging to Curb Meat Consumption.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 75: 101592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101592.

- Sparkman, G., and G. M. Walton. 2017. “Dynamic Norms Promote Sustainable Behavior, Even If It is Counternormative.” Psychological Science 28 (11): 1663–1674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617719950.

- Stok, F. M., D. T. D. De Ridder, E. De Vet, and J. B. F. De Wit. 2012. “Minority Talks: The Influence of Descriptive Social Norms on Fruit Intake.” Psychology & Health 27 (8): 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.635303.

- Syme, G. J., and K. D. Williams. 1993. “The Psychology of Drinking Water Quality: An Exploratory Study.” Water Resources Research 29 (12): 4003–4010. https://doi.org/10.1029/93WR01933.

- Tallis, F., and M. W. Eysenck. 1994. “Worry: Mechanisms and Modulating Influences.” Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 22 (1): 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800011796.

- Tannenbaum, M. B., J. Hepler, R. S. Zimmerman, L. Saul, S. Jacobs, K. Wilson, and D. Albarracín. 2015. “Appealing to Fear: A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeal Effectiveness and Theories.” Psychological Bulletin 141 (6): 1178–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039729.

- Tanner, J. F., L. A. Carlson, M. A. Raymond, and C. D. Hopkins. 2008. “Reaching Parents to Prevent Adolescent Risky Behavior: Examining the Effects of Threat Portrayal and Parenting Orientation on Parental Participation Perceptions.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 27 (2): 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.27.2.149.

- Turner, M. M. 2012. “Using Emotional Appeals in Health Messages.” In Health Communication Message Design: Theory and Practice, edited by H. Cho, 59–72. Washington, D.C.: Sage.

- US EPA. 2019. Potential well water contaminants and their impacts. Accessed July 11, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/privatewells/potential-well-water-contaminants-and-their-impacts.

- Weinstein, N. D. 1999. “What Does It Mean to Understand a Risk? Evaluating Risk Comprehension.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI) Monographs 25: 15–20.

- WHO. 2018. Fact sheet: Arscenic. Accessed July 11, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/arsenic

- Witte, K., and M. Allen. 2000. “A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeals: Implications for Effective Public Health Campaigns.” Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education 27 (5): 591–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810002700506.

- Yousef, M., S. Rundle-Thiele, and T. Dietrich. 2023. “Advertising Appeals Effectiveness: A Systematic Literature Review.” Health Promotion International 38 (4): daab204. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab204.