ABSTRACT

This paper reports on an exploratory survey investigating both translingual practices in English language classrooms in India and attitudes towards translanguaging and L1 use among teachers surveyed. 169 teachers from primary, secondary, tertiary and adult sectors responded to 33 quantitative and six qualitative items investigating nine research questions. The majority of respondents reported making only occasional use of other languages in English language classrooms, most often for comparing and contrasting language features, explaining concepts, managing the classroom and translating for learners. Only a minority of teachers reported actively facilitating translanguaging during language practice activities. English medium institutions were found to be less tolerant of L1-use practices than non-English medium institutions. More experienced teachers were more likely to express more pro-translanguaging beliefs and report more L1-inclusive practices. Important differences between urban, semi-urban and rural contexts were also found, indicative of a need for varied, context-sensitive approaches to multilingual practices in English classrooms across India. We argue that there is a need for an explicit focus on use of other languages in Indian English language teacher education and suggest more cohesive support for translingual practices across the education system. We also propose an additional ‘inclusive position’ to Macaro’s (Citation2001) three ‘codeswitching’ positions.

1. Introduction

Translingual practices are, and have always been, fundamental to communication in India. As a linguistically diverse country, the flexible blending of features from different languages is common in interactions from the home to the marketplace and from street signs and adverts to cinema and high literature (see Meganathan Citation2017). While this blending has traditionally been referred to as code-switching, the terms translanguaging (to describe the act; García Citation2009) and translingualism (to refer to translingual practices in society at large; Canagarajah Citation2013) have recently been adopted to recognise that such practices do not so much involve ‘switching’ between separate systems, but instead involve drawing flexibly on resources from a single, unified languaging system, appropriate to context, interlocutor and interaction. The competence underlying such practices has been referred to as ‘performative competence’ by Canagarajah (Citation2013) and ‘translingual competence’ by Anderson (Citation2018). García (Citation2009, 140) defines ‘translanguaging’ as ‘the act performed by bilinguals of accessing different linguistic features or various modes of what are described as autonomous languages, in order to maximise communicative potential’, the definition that will be used in this article.

For much of the twentieth century, approaches to language teaching disseminated from historically monolingual communities in Europe and North America tended to favour target-language only teaching (Hall and Cook Citation2012), what Cook (Citation2010) calls ‘intralingual’ approaches. However, the recent multilingual turn (García and Li Citation2014; May Citation2014; Sembiante Citation2016) has questioned this monolingual assumption, instead arguing for approaches to education that are more inclusive of learners’ holistic languaging resources. While this reorientation is significant, as part of the predominantly western discourse on the history of language teaching, it neglects an important reality: approaches to teaching in many multilingual countries have often involved more pragmatic use of learners’ prior languaging resources throughout the twentieth century (Lin Citation1996; Sridhar Citation1994).

By default, classrooms across India are multilingual in nature. Decisions about language(s) of instruction are loosely governed by India’s national language in education policy: the Three Language Formula. This recommends children are taught in their home language at primary level, with a second Indian language taught as a subject along with (usually) English introduced later (Mohanty Citation2010). In practice, the ‘home language’ of primary schools generally defaults to the state language and the introduction of additional languages varies across the country. Meanwhile, the majority of state governments are struggling to make decisions to retain students whose parents are considering opting for low-cost private school education – often ‘English medium’, on paper, if not in practice (Erling, Adinolfi, and Hultgren Citation2017). Policy documentation, including the legally binding Constitution of India and its recent amendment, the Right to Education Act (Ministry of Law and Justice Citation2009), champions the multilingual nature of India and recognises the need for its preservation:

It shall be the endeavour of every State and of every local authority within the State to provide adequate facilities for instruction in the mother-tongue at the primary stage of education. (Government of India Citation2012, Part XVII Chapter IV, 177)

Medium of instructions shall, as far as practicable, be in child’s mother tongue [sic]. (Ministry of Law and Justice Citation2009, Chapter V section 29.1 (f))

While discussion of translingual practices in academic literature has focused extensively on how they can become incorporated into educational systems in multilingual communities in western countries, there have been relatively few peer-reviewed studies on translingual practices in multilingual communities in the east and the south (García and Li Citation2014; Kachru Citation1994; May Citation2011; Sridhar Citation1994). Thus, in light of India’s linguistic diversity, its naturally translingual practices and its forward-looking, L1-inclusive educational policy documentation, we aim firstly to explore recent research on translingual/multilingual approaches in English language classrooms in India and secondly to report on a survey conducted with English language teachers across India, investigating teachers’ self-reported practices and attitudes with regard to the use of other languages in the English classroom. We discuss the implications of these research findings and make a number of recommendations based on them.

Given the pervasiveness of linguistic terminology, and the need to describe holistic languaging practices simply in the survey itself, we use the traditional term ‘L1’, but reconceptualise it as a holistic, single resource: a ‘languaculture’ (Agar Citation1994) that may include features of a number of different languages (e.g. the L1 of a learner from a Bengali family living in New Delhi may include features of Bangla, Hindi, English and Urdu). We also use the term ‘other languages’ (OLs), especially in the survey questions to refer to codes, dialects and other resources that are not traditionally associated with English as the language under discussion.

2. Literature review

Aside from the recent arguments in favour of translingual practices in education discussed above, the revival of support for L1 use in language learning has been relatively cautious in the West. Macaro’s (Citation2001, 535) three codeswitching positions summarise three predominant attitudes towards L1 use at the turn of the century in the UK:

The Virtual Position: The classroom is like the target country. Therefore we should aim at total exclusion of the L1. There is no pedagogical value in L1 use. The L1 can be excluded from the FL classroom as long as the teacher is skilled enough.

The Maximal Position: There is no pedagogical value in L1 use. However, perfect teaching and learning conditions do not exist and therefore teachers have to resort to the L1.

The Optimal Position: There is some pedagogical value in L1 use. Some aspects of learning may actually be enhanced by use of the L1. There should therefore be a constant exploration of pedagogical principles regarding whether and in what ways L1 use is justified.

It is notable that even Macaro’s ‘Optimal Position’ appears to be more tolerant (seeking justification), rather than inclusive (recognising it as part of the learner’s identity and resources) of other languages, despite his regular advocacy for L1 use (see Macaro Citation2005). This L1-tolerant position is reflected in several more recent publications on L1 use in the West where ‘judicious’ use of L1 is often recommended (see, e.g. the edited volume by Turnbull and Dailey-O’Cain Citation2009, 5, 17, 34). However, the use of languages in classrooms in multilingual countries such as India is less explored – to what extent have approaches here been either tolerant or inclusive of learners’ other languages? For the remainder of this literature review we focus on studies from India, all of which attest to more widespread use of OLs in the classroom. Readers interested in the more general arguments and evidence for and against L1 use are advised to read Hall and Cook’s (Citation2012) detailed overview.

Rahman’s study of English language teaching in Assam (Citation2013) used classroom observation, interviews and questionnaires to collect data. He noted that 65% of 25 teachers surveyed use L1 (65% of this usage involved explaining concepts to learners), and 95% of 300 learners surveyed felt that they needed the help of Assamese in English classes. He concluded, ‘carefully used, Assamese (L1) can play a facilitative and supportive role in the English classroom’ (221). His recommendations include the flexible use of linguistic resources through encouraging students ‘to use Assamese vocabulary in English sentences’ (220), judicious use of L1 depending on variables such as cognitive level of learners and teaching objectives, and the recommendation that use of L1 should be ‘legalise(d)’ (221) to lead to more systematic use. Rahman calls for standardised guidelines to support this, and the need for active support for such policies at school level by head teachers and others in the teaching-learning community.

As part of a larger study on English as a medium of instruction (EMI) education, Erling, Adinolfi, and Hultgren (Citation2017) observed 11 teachers working in both private low-cost English-medium schools and a Hindi-medium government school in Bihar, all at upper primary level. They report that 10 of the 11 observed teachers used a combination of languages (Hindi and English) for instruction, with just under half of the time spent speaking in Hindi. Hindi was mainly used for classroom management purposes or paraphrasing parts of a text: ‘In the [low cost English medium schools], there was an overwhelming sense that classroom codeswitching was a legitimate practice that was needed due to students’ developing competence in English’ (106). The students, when they spoke, mainly used English but this was predominantly in response to choral drilling or other repetition of what the teacher had said. Interestingly, the teachers and head teachers did not report any conflict with the use of ‘dual language’ instruction (the use of Hindi and English in the classroom) when interviewed. However, there were several instances of teachers reporting that the use of other more local languages is ‘not allowed’, for example by head teachers. One teacher reported, ‘I do not speak Bajjika here with children because it does not feel good. A complaint may go to the parents immediately’ (120).

Chimirala’s (Citation2017) more extensive survey of teachers of all subjects in English-medium state schools in Andhra Pradesh analysed data from 276 questionnaires and 40 interviews. She found that 95% of teachers reported using languages other than English in the classroom (69% of this usage involves explaining concepts and difficult words), but that only 71% allow their students to use other languages. Chimirala uncovers ‘conflicting discourses’ in the extensive interview data, but notes that the majority of teachers recognise that ‘if learners have to connect to the lesson, they should be allowed to use their multilingual repertoires’ (165–166). She cautions that ideologies driven by both institutional norms and pre-service and in-service programmes are perpetuating a monolingual mindset inappropriate to the multilingual diversity of India, a mindset that, she suggests, may account for the behaviour of the 24% of teachers who reported using L1 in class but, paradoxically, did not allow their learners to do so.

Durairajan (Citation2017) reviewed 19 studies of more L1-inclusive approaches and strategies implemented in Indian English language classrooms since 1981, mainly at secondary level. This included 16 studies since 2000 using L1 in a scaffolding role, and three earlier studies into bilingual learning. The most consistent finding across these studies was an increased sense of empowerment and self-confidence among learners through L1-mediated learning, but she also notes reports of improved fluency in storytelling, greater metalinguistic awareness, better recall and use of vocabulary in English. Of particular note are three studies into the use of L1 for planning and organising writing that ‘showed remarkable improvement’ (313). Durairajan recommends using L1 to tap existing capabilities, to plan for L2 use, to encourage greater use of bilingual texts, and, importantly, suggests curriculum designers need to reconceptualise linguistic competence as a holistic entity ‘to enable growth across languages’ (314), envisaging a translingual competence of sorts to replace the monolingual mindset that Chimirala (Citation2017) alludes to. Durairajan concludes that ‘a course in multilingual education practices ought to be mandated in all teacher education programmes’ (314).

While this research reveals both extensive, principled use of OLs in some contexts, and an interest in understanding and using OLs in the English classroom especially within a social constructivist framework, it is clear that at least in some cases this is inhibited by the perpetuation of a more monolingual mindset through the practices of both institutions and practitioner culture, leading to a state of ‘guilty multilingualism’ (Coleman Citation2017, 31), in which L1-use practices are often stigmatised and drawn upon secretly. This mirrors findings from studies conducted in comparable contexts, which highlight teachers’ reticence to use languages other than the prescribed medium of instruction in the classroom for fear of retribution by their supervisors or due to a general belief that it is not beneficial for student learning (e.g. Clegg and Afitska Citation2011; Ferguson Citation2003; Probyn Citation2009).

3. Methodology

3.1. Aims and research questions

The aim of our survey was presented in the survey introduction: ‘to better understand how teachers of English in India do or don’t make use of other languages in the English language teaching and learning process’. Our intention was to investigate such practices from a more holistic, translingual perspective than traditional research on ‘L1 use’ in the classroom has tended to do (e.g. De la Campa and Nassaji Citation2009; Duff and Polio Citation1990; Hall and Cook Citation2013), as appropriate to the translingual heritage and practices of India. Our research questions were exploratory, as follows:

Use of languages other than English in relation to teaching contexts

(A1) To what extent do teachers of English in India feel free to make use of OLs in their classrooms?

(A2) Does this vary depending on contextual factors, such as medium of instruction (MOI), shared language availability and type of institution?

Translanguaging in the community and classroom

(B1) How extensively is translanguaging reported in communities around schools?

(B2) Do translanguaging practices extend into English language classrooms?

Teachers’ self-reported classroom practices

(C1) In what ways are OLs involved in English language learning (as reported by respondents), and to what extent is translanguaging part of this?

(C2) To what extent do teachers actively encourage, rather than simply allow, use of OLs in the classroom?

Teachers’ beliefs and opinions concerning OL use

(D1) What attitudes and beliefs exist among teachers of English in India towards OL use in the classroom?

(D2) What contextual factors correlate with more OL-inclusive opinions among these teachers?

(D3) Are teachers’ attitudes towards OL use consistent with their self-reported classroom practices?

3.2. The questionnaire

The questionnaire (see Appendix for wording of all items as presented to respondents) consisted of four sections, with 33 closed, quantitative items and six open-ended opportunities to add qualitative comments (mainly at the end of sections, as recommended by Dörnyei [Citation2003, 48]). As well as asking questions commonly presented in surveys investigating L1 use (e.g. use of OLs for classroom management, explanation or translation activities; Chimirala Citation2017; Hall and Cook Citation2013), we also included one item on whether teachers actively encourage use of other languages (item 26), and several items to explore translanguaging practices (items 19, 21–24). Two items investigated whether teachers engaged in comparative analysis of languages (16 and 18). Six items were also included to elucidate teachers’ beliefs regarding OL use (28–33), including one (28) based on Macaro’s (Citation2001) three codeswitching positions (see Literature Review above), but adding a fourth ‘inclusive’ position in anticipation of more OL-inclusive practices among Indian teachers (see below for wording: position names were not included in the questionnaire itself). Guidelines by Dörnyei (Citation2003, Citation2007) were followed, with careful attention to ensure that the survey was appropriate in length and organisation, and that specialist terms (e.g. translanguage, comparative analysis) were avoided. Email addresses were requested (in case of the need to clarify or further investigate qualitative responses), but optional. The survey was piloted with 10 teachers working in, or with experience of, similar teaching contexts to those targeted. Based on this piloting, several minor changes were made to improve clarity, including rewording of survey items to simplify structure, and choice of lexis.

3.3. Administration

The survey was administered online using Google Forms. Respondents provided informed consent and also confirmed that they were teachers of English in India before proceeding to the survey itself. Invitations to participate were sent out via the British Council’s networks in India (project databases and social media sites for English language teachers). The survey link remained live for two weeks, with two reminders sent to potential respondents. The limitations of this non-probability volunteer sampling are discussed below.

Early analysis of demographic data indicated the presence of distinct contexts suspected to relate to a rural-urban divide. Those who had provided email addresses were contacted to ask whether they taught in urban, semi-urban or rural communities.Footnote1 76 replies were received (45% of total survey respondents), enabling cross-tabulation of this variable with others, although this variable was not included in contextual factor analyses in sections A-D due to smaller sample sizes.

3.4. Data analysis

Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS 24. Frequency counts and exploratory graphs were used to check for potential correlations. Several statistical tests were also performed to examine the significance of potential correlations with respondent characteristics and contextual variables. Fisher’s exact test was used in all cases as dependent variables were categorical and involved low frequencies for some values (Field Citation2009).

Qualitative data was analysed in two ways. As is typical in survey studies (Dörnyei Citation2003), it initially served to inform, support and expand upon the statistical data. As such, responses mentioning specific questions were categorised and codified, then selected to provide exemplification or clarification of points made. However, given the extent and ‘richness’ of the qualitative data (over 5000 words), it was also deemed appropriate to analyse it as a whole. This involved a second categorisation and codification stage, to enable key narratives to inform the Discussion section of the paper alongside, rather than subordinate to, the quantitative data. Quotes selected included those that were representative of common opinions, challenges or narratives and those that revealed specific, often innovative insights into the respondents’ worlds.

4. Findings

4.1. Respondents’ characteristics and contexts

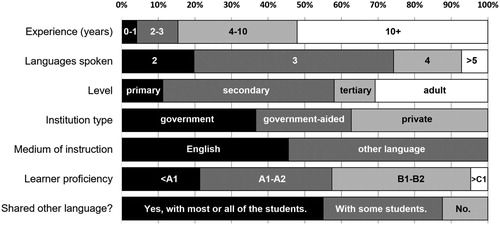

169 teachers completed the 33 quantitative items in the survey. 70 of these also provided additional qualitative data (see Appendix for frequencies and percentages). summarises key demographic data reported, revealing that most had extensive teaching experience, almost half (47%) were secondary teachers, the majority were working in state-school education, and represented a balance of teachers working in both EMI and non-EMI institutions (Marathi [12%], Hindi [10%], and Kannada [9%] were the most common non-English mediums reported). Learner proficiency levels reported were mainly in the A1-B2 range and, reflecting what we know about multilingualism in India, 80% of the teachers reported speaking three or more languages.

compares six contextual factors for urban, semi-urban and rural locations, suggesting a rural-urban continuum, with values for teachers working in semi-urban contexts typically lying part-way between those in urban and rural contexts.

Table 1. The rural-urban continuum (n = 76). *1 = beginner; 2 = elementary/pre-intermediate; 3 = intermediate/upper intermediate; 4 = advanced.

4.2. Use of languages other than English in relation to teaching contexts

(A1) To what extent do Indian teachers feel free to make use of OLs in their classrooms?

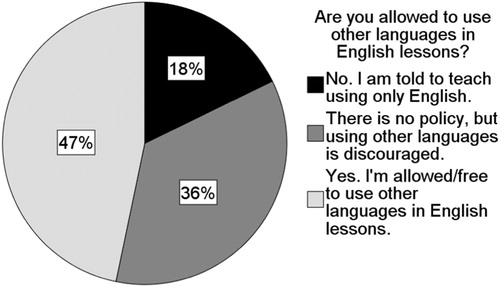

Item 7 investigated this question. displays responses. Just over half felt they were either discouraged from using OLs or told to use only English.

Figure 2. Teachers’ perceptions of freedom to use other languages. Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

(A2) Does freedom to use OLs vary depending on contextual factors?

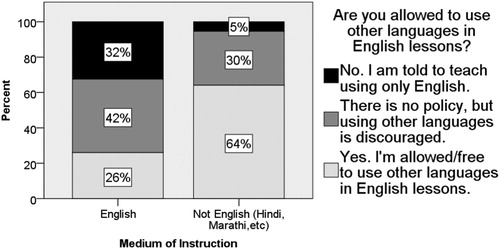

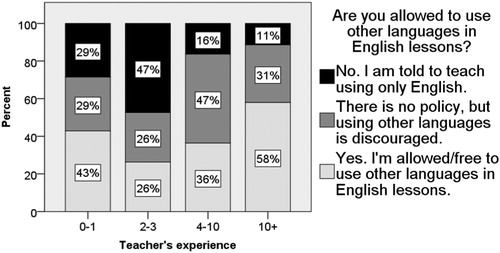

Exploratory graphs indicated correlations with several contextual variables, which were tested for significance. Unsurprisingly, MOI was significant, with respondents in EMI schools much less likely to indicate freedom to use OLs (Fisher’s χ2(2, n = 169) = 32.813, p ≤ 0.001; see ). Likewise, teachers who shared OLs with their learners expressed more freedom to use them than those who did not (Fisher’s χ2(4, n = 169) = 25.182, p ≤ 0.001). Institution type was significant, with teachers in private schools less likely to indicate freedom to use OLs (Fisher’s χ2(4, n = 169) = 32.491, p ≤ 0.001), and, interestingly, teacher experience was also significant, with more experienced teachers being more likely to indicate freedom to use OLs (Fisher’s χ2(6, n = 169) = 18.114, p = .003; see ).

Figure 3. Freedom to use other languages by medium of instruction. Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Figure 4. Freedom to use other languages by teacher experience. Notes: Only 7 respondents had 0–1 years’ experience. Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Of 28 qualitative responses offered at the end of Section A, 11 specifically mentioned item 7, and another five were evidently referring to this issue. Most chose to explain how or why they used OLs, several of whom were clearly well-informed in their choices:

In my English language class I do use code mixing or code switching so that my learners can also confidently respond in English using same technique. In this way I help them in their second language acquisition.

Sometimes I have to use Mother tongue when the tribal students are unable to understand the concept. The basic knowledge of the students is very poor. They are not well prepared in their primary classes.

4.3. Translanguaging in the community and classroom

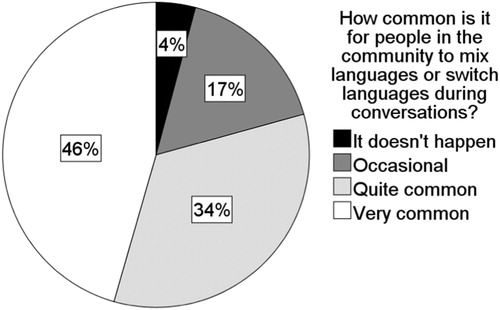

(B1) How extensive is translanguaging reported in communities around schools?

Responses indicated that two (27%), three (36%) or four (15%) languages were present in the majority of local communities around respondents’ schools, with higher linguistic diversity found in urban contexts (a mean of 4.81 languages, compared to 2.67 in rural contexts; see ). A number of the 74 qualitative responses following this question indicated extremely high linguistic diversity, for example by listing all the languages in question:

English, Marathi, Hindi, Gujarati, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Urdu

Besides there are regional dialects which overpower the atmosphere. The dialects are Bhilori, Pawari and Ahirani.

(B2) Do translanguaging practices extend into English language classrooms?

Responses to item 11 (see ) indicated that the majority of teachers share a language other than English with most/all (55%) or some (33%) of their learners, clear evidence of the potential to exploit this shared resource in the classroom, however, in many cases this lingua franca may be the official state language, rather than learners’ ‘mother tongue’, where this is different.

Figure 5. Translanguaging in the community. Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

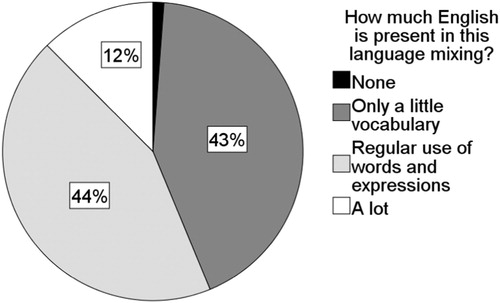

Figure 6. English in community translanguaging. Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

The majority of respondents reported that the mixing of languages in English lessons by students was either very common (34%) or quite common (36%). Comments provided for section B (n = 29) shed some light on translanguaging in the classroom, most involving neutral or slightly negative attitudes towards such practices:

Hindi is used most of the time for inter-personal communication, both inside and outside the classroom.

Yes, it’s common with students to mix Gujarati with English when they don’t know English counterparts of some words.

My students mix English and Tamil. Telugu and English. Because when they don’t understand a concept they mix it up.

4.4. Teachers’ self-reported classroom practices

(C1) In what ways are OLs involved in English language learning (as reported by respondents), and to what extent is translanguaging part of this?

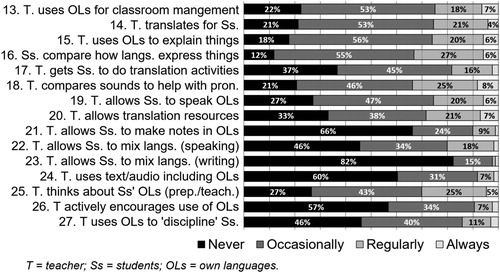

summarises responses to 15 items designed to elicit teachers’ reported practices concerning OL use (see Appendix for exact wording). The majority reported using OLs ‘occasionally’ or ‘never’. Comparison of languages (both ‘how they express things’ and comparing sounds between languages) and teacher explanations in OLs were the most frequently reported uses of OLs, followed closely by use of OLs for translation and classroom management. Skills activities involving translanguaging were comparatively rare among responses, especially those involving writing and translingual texts. There was greater tolerance of OLs in speaking activities, with 34% indicating ‘occasionally’, and 18% ‘regularly’, allowing students to mix languages.

Figure 7. Respondents’ self-reported reasons for using other languages. Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

The majority of comments offered for Section C of the survey either described in more detail how they use OLs, or justified their use of OLs, with several feeling the need to make specific reference to students’ backgrounds (especially rurality):

Due to lack of knowledge of English in rural area we have to use their local language to give instructions, guidance, etc.

If there is a text or poem which is available in their mother tongue, I recommend my learners to read it.

(C2) To what extent do teachers actively encourage, rather than simply allow, use of OLs in the classroom?

also shows responses to item 26. 57% of respondents reported never actively encouraging use of OLs, and a further 34% only doing so occasionally. 7% selected ‘regularly’ and only four respondents stated that they ‘always’ encourage use of OLs. Only three qualitative responses to Section C indicated encouraging use of OLs, two of which, interestingly, were from teacher trainers:

I occasionally encourage teacher trainees to translate from other languages to English especially in my writing classes.

I never [en]courage them to use other language. But I allow them to use other language as most of them can’t express themselves properly in English.

4.5. Teachers’ beliefs and opinions concerning OL use

(D1) What attitudes and beliefs exist among Indian teachers towards OL use in the classroom?

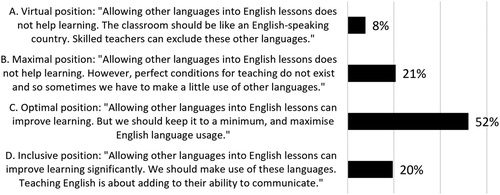

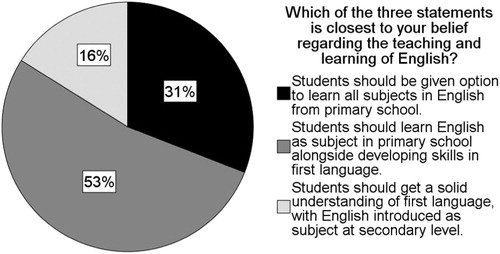

The first item (28) in this section sought to investigate attitudes towards OL use among respondents, drawing on our adapted version of Macaro’s (Citation2001, 535) codeswitching position statements. shows wording and responses. While just over half the respondents selected the optimal position, 33 respondents (20%) selected the inclusive position, justifying its inclusion.

A number of teachers chose to expand on the options they had chosen in the comments for section D, representing the four positions (virtual, maximal, ‘optimal’ and inclusive) well:

Virtual position:

I have a strong feeling that English lessons should be taught only in English and it should not be mixed with L1.

Maximal position:

Depends on the prerequisite I mean we may ask them to use other languages initially later we should not encourage the use of other languages. If they use any other language how will they learn English.

‘Optimal’ position:

I occasionally use Kannada in my explanation of lessons. But strictly allow only English for writing in English lessons. I never encourage using other languages during English class, but when it is entirely difficult for the child to express in English, I allow them to mix up Kannada (to open up).

Inclusive position:

In group work or pair work, the students are allowed to talk in their own language, so that they feel comfortable to share their views, then they report in English.

Figure 9. English teachers’ opinions on MOI in India. Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Items 30 and 31 investigated teachers’ attitudes to translanguaging in the classroom and in future careers. While almost all teachers recognised translanguaging as either natural (80%) or inevitable (15%) in the classroom, fewer seemed to recognise the likelihood of students needing to translanguage with English in their future careers (only 29% considered that they will need to mix languages frequently or all the time). Given recent findings reporting the likely translingual futures of adult learners of English from less multilingual countries than India (Anderson Citation2018Footnote2), this difference is of note.

Items 32 and 33 elicited teachers’ opinions on two Likert scale items. Responses to item 32 indicated that 46% of respondents believe languages should be treated separately to avoid confusion compared to 34% who disagree with this opinion, and responses to 33 indicated that there was majority agreement for the opinion that teaching should always build on students’ prior knowledge (82% chose either ‘agree strongly’ or ‘agree’).

(D2) What contextual factors correlate with more OL-inclusive opinions among Indian teachers?

Exploratory graphs were used to examine relationships between items 28–30 and 32, and respondents’ characteristics and contextual variables, with Fisher’s exact test used to identify significant associations. For item 28 (respondents’ choices between the four OL-use positions) MOI was, unsurprisingly, found to be significant, with teachers working in EMI schools more likely to adopt virtual positions and teachers in government and government-aided schools more likely to adopt the other three positions (Fisher’s χ2(3, n = 169) = 15.780, p = .001). Whether teacher and learners shared OLs also proved significant for item 28. None of the teachers who did not share OLs with learners adopted the inclusive position, and those who did share OLs were found to be less likely to adopt virtual positions (Fisher’s χ2(6, n = 169) = 31.568, p ≤ 0.001).

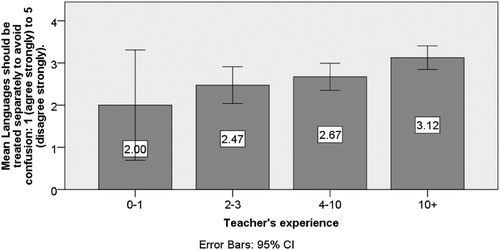

For item 32 (whether languages should be treated separately to avoid confusion), two interesting correlations were found, with teacher experience and learner proficiency. Teachers who had more experience (Fisher’s χ2(12, n = 169) = 23.164, p = .010), and teachers who reported higher English proficiency levels among their learners (Fisher’s χ2(12, n = 169) = 22.390, p = .017) were less likely to believe that languages should be treated separately in teaching practices (see ).

(D3) Are teachers’ attitudes towards OL use consistent with their self-reported classroom practices?

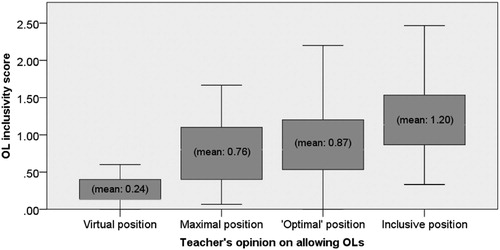

In order to assess how well respondents’ chosen OL-use positions from item 28 correlated to their self-reported classroom practices, frequency ratings for items 13-27 were converted to numeric scales (0 = never; 3 = always) and averaged to create multi-item scales (Dörnyei Citation2007, 103) indicative of each teacher’s willingness to include OLs in their practices, termed ‘OL-inclusivity scores’. These ranged from 0 (indicating an average of ‘never’) to a highest score of 2.5 (averaging half way between ‘regularly’ and ‘always’) with a sample mean of 0.86. Mean values for the four OL-use positions were found to correlate with respondents’ OL-inclusivity scores (see ), offering further validity for the addition of the ‘inclusive position’ to Macaro’s (Citation2001) model.

5. Discussion incorporating the voices of our respondents

The findings of this survey support those of previous studies revealing that other language use is common in English language classrooms in India (e.g. Chimirala Citation2017; Rahman Citation2013). The following discussion of the more complex questions as to who uses which languages, when, why, how and how much must remain tentative and cognisant of the limitations of the study (see below).

5.1. How much OL use was reported, and what for?

The vast majority of respondents reported using OLs at least occasionally, with only two respondents reporting that they never use or allow OLs. The sample mean OL-inclusivity score of 0.86 (0 = never; 1 = occasionally) indicates occasional use on average, but not for all purposes indicated. This is consistent with the ‘English-mainly’ belief expressed in several qualitative responses offered, with terms such as ‘practice’, ‘exposure’ and ‘use’ frequently used as justification:

I strongly agree that students who hesitate to speak in English in the class should be given lot of practise in conversations even though they make lot of grammatical mistakes. This builds up their confidence and they enjoy learning the subject as well.

I’m a teacher of spoken English for secondary level students who have had very little exposure to spoken English. Therefore, many concepts have to explained to them in L1 and sometimes they have to be allowed to express their views in L1 to help them say it in English.

An important finding of this study is that the most commonly reported use of OLs among respondents is for comparative analysis of languages (see items 16 and 18 in above). This use is rarely asked about on questionnaires of OL use (e.g. Hall and Cook Citation2013; Levine Citation2003; Liu et al. Citation2004), although Hall and Cook (Citation2013) found it was the most commonly added suggestion in qualitative responses. To our knowledge, the question on ‘comparing sounds’ has never been asked before, but clearly appeared to be an important way of building English language awareness upon L1 knowledge.

Among the least commonly reported OL uses, skills practice involving translanguaging (especially translingual writing) stands out, reflecting both the more conservative entrenched norms of writing (Canagarajah Citation2013), and the ‘negative attitudes’ towards translanguaging in academic contexts prevalent in many countries (Simpson Citation2017, 12), although the flexibility of a number of respondents, especially to allow more use of OLs to scaffold the emergence of English, should be noted:

At the primary and secondary stage I feel using another language as a scaffolding device to teach English is fine. The children can lean on to Hindi or mother-tongue to learn English. Using only English in the classroom, may induce a feeling of alienation which may discourage them from learning English or slow down the process of learning.

In order to develop their listening skills, I’ve exposed them to Hindi songs before sharing English songs. For our Cultural evenings, we encourage them to present some typical song or dance from their country (for foreigners) or state (for Indians).

5.2. MOI and EMI

While there were clear, obvious correlations between MOI and whether teachers reported being allowed to use OLs, another correlation is of note, that of a much higher percentage of respondents working in EMI schools in urban locations (74%) compared to semi-urban (46%) and rural (17%) schools (see ). Further analysis of the data revealed that 25 of the 77 respondents who work in EMI schools reported above-average OL inclusivity scores, indicating that they have adopted more OL-inclusive practices, despite the official status of their institutions, as similarly found by Erling, Adinolfi, and Hultgren (Citation2017). This appears to be evidence of what Simpson calls ‘the rise of low-fee private schools – frequently labelled ‘EMI’, though actual language practice may be unknown’ (Citation2017, 7). Although most respondents who provided qualitative data had little difficulty expressing themselves in English, the errors in the following comment from a teacher working in an EMI school reveal that at least some of those asked to teach only in English may not have levels of English adequate to the task (also noted by Erling, Adinolfi, and Hultgren [Citation2017]):

This on and off of proper use of Eng is because ,despite of having an English medium school ,students are from villages.

5.3. The rural-urban continuum

above provides evidence of something that most Indian teachers and teacher educators are very much aware of, that is, the existence of a rural-urban continuum in English language teaching in India. Important differences in a number of contextual factors shown in this table (e.g. mean number of languages in the community) likely influence detectable differences in pedagogic practices, such as higher mean scores for OL inclusivity in rural schools (1.00) when compared to semi-urban (0.87) and urban (0.72) schools, something that is also echoed in the qualitative data. Several references (12 respondents) to ‘rural’ contexts, including ‘tribal students’, ‘village background’ and ‘rural children’, are of note among the comments volunteered, with many respondents invoking rurality to explain either the challenges they face, or the ‘need’ to use OLs:

Most of the students come from semi-rural area. They are very poor in English and therefore prefer to talk in Gujarati mixing some common English words only.

Since i teach for rural children, sometimes it requires to explain it in other language to encourage them to respond, make the concept clear.

In colleges of rural or semi-rural areas, English teachers and students are not encouraged.

As my school is in Mumbai but it is a slum, students use Hindi while they are with their friends, at their house they speak Marathi.

For other students I take the help of other students who use good English in the class. Peer help is very important in such situation.

6. Conclusion

6.1. Limitations

The limitations of the non-probability volunteer sampling used in this study are here acknowledged (Hewson et al. Citation2003) and caution should be used when attempting to generalise from our findings. While the fairly large sample size and diversity of respondent contexts suggests a reasonable balance of representation across major contextual factors in Indian ELT, it is likely that respondents to our survey have a greater than average interest in their professional development and in contributing to the wider body of knowledge relating to language teaching and learning. Primary and tertiary teachers are underrepresented in our data. Teachers without easy internet access are also likely to be underrepresented.

The danger of interpreting self-reported data as evidence of actual classroom practice is also acknowledged. As such, we have been careful in this paper not to assume such reports to be evidence of actual practice. Likewise, where we have asked respondents to report on linguistic diversity and translanguaging in the community, these reports have been interpreted as perceptions, rather than evidence of such phenomena.

6.2. Recommendations

Alongside ‘guilty multilingualism’ (Coleman Citation2017, 31), our data reveal that a feeling of ‘guilty translanguaging’ is also tangible in the voices and self-reported practices of our respondents. While translingual interactions involving English are a central feature of the performative competence of Indians in their daily lives (Anderson Citation2017), it seems that comparatively few of the Indian teachers we surveyed believe in encouraging the development of such competence in their classrooms, or purposefully make use of translanguaging practices to facilitate learning. This is likely due to a range of influences and beliefs among these teachers, including the pressure to (pretend to) teach only in English for some, disdain for hybrid languaging practices for others, and conservative curricula and assessment criteria that lead many Indian teachers to force their learners to use English in ways that contrast with their own behaviour, even in the classroom. We suggest that teachers of English in India could incorporate more flexible, natural processes to facilitate more learning and prepare their learners more appropriately for participation in society at large.

We echo Durairajan’s (Citation2017) call for an explicit focus on OL use in teacher education in India, and also suggest that such support should recognise natural language-use practices present in society and reflect this in pedagogic guidance offered to teachers, so that ‘both the content and the processes of instruction for learners … might usefully be modified to prepare them for future translingual environments’ (Anderson Citation2018, 32), a belief that several of our respondents have exemplified when describing their own attitudes and classroom practices. Particularly at primary level, where the focus should ideally be on developing literacy in mother tongue or closest possible dialect first whenever possible, and OLs including English after this, translanguaging can be seen as a legitimate way to scaffold learning. It can help to build new knowledge on current understandings and to develop new ways of languaging from within current practices, thereby developing learners’ languaging resources holistically. In relation to this, we believe our fourth ‘inclusive position’ is an important addition to Macaro’s (Citation2001) three codeswitching positions, and suggest that his so-called ‘optimal position’ might more accurately be labelled a ‘judicious position’ given that the normative question of which position is ‘optimal’ requires further research and is likely to vary depending on context. Considering the diversity of contexts found within India itself, the question of exactly how classroom practices should make use of learners’ languaging resources remains an area where much discussion and local innovation is required, based on practitioner experience at grass roots level. Bringing this discourse into the open makes it possible for teachers to share personal solutions and to reflect critically on their own language-use practices when teaching to identify more and less effective translingual practices.

Nonetheless, we also caution that the support for such practices needs to be provided at all levels of the educational system for real change to happen. While policy documentation has long recognised the need for what we advocate here, if the guidelines and edicts issued at state, division and district level contradict national guidelines, coherent change becomes more difficult, teachers receive mixed messages, and, perhaps most importantly, the materials that could support more translingual practices in the classroom do not get developed or promoted.

In this paper, we have endeavoured to shed light onto both current perceptions and future possibilities concerning translingual practices in Indian classrooms without, we hope, simplifying the undeniable complexities relating both to socio-political contexts and the tasks of awareness raising and skills development required in order to change mindsets and practices for the better. At the root of these complexities lie fundamental questions of rights and equity that remain as relevant today as they were a decade ago when A.K. Mohanty noted:

The exclusion and non-accommodation of languages in education denies equality of opportunity to learn, violates linguistic human rights, leads to the loss of linguistic diversity and triggers a vicious cycle of disadvantage perpetuating inequality, capacity deprivation and poverty. (Mohanty Citation2009, 121)

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to all participants in this study and would like to thank them for their time and for sharing their views. We also thank John Simpson for his comments on an earlier draft of this piece, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and critique.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jason Anderson

Jason Anderson is a teacher educator, educational consultant, and award-winning author of books for language teachers. He has taught languages, trained teachers, and developed materials to support teachers in primary, secondary, and tertiary contexts, both pre-service and in-service, in numerous countries across Africa, Asia, and Europe. He has worked for national ministries of education and development partners including UNICEF, the British Council, and VSO. His interests include pre-service and in-service teacher education, translingualism in language teaching, and issues of appropriacy of methodology and social context, especially in low-income countries.

Amy Lightfoot

Amy Lightfoot is the Regional Education and English Academic Lead for the British Council in South Asia. She leads on the academic strategy and quality assurance of education projects and related research programmes across the region. She has been working in the field of education for 20 years, with over a decade of specialising in South Asian contexts. She has special interests and expertise in multilingual education, the use of digital platforms and alternative models for professional development and the monitoring and evaluation of teacher competence and performance.

Notes

1 ‘Semi-urban’ in India denotes population centres of 10,000–99,999 citizens (Government of India Citation1961).

2 Anderson (Citation2018) found that 76.7% of 116 English language learners studying in the UK “perceived a need for translingual practices in the future” (313).

References

- Agar, M. 1994. Language Shock: Understanding the Culture of Conversation. New York: William Morrow.

- Anderson, J. 2017. “Translanguaging in English Language Classrooms in India: When, Why and How?” Paper presented at 12th international ELTAI conference, Ernakulum, India, June 29–July 1.

- Anderson, J. 2018. “Reimagining English Language Learners from a Translingual Perspective.” ELT Journal 72 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1093/elt/ccx029.

- Canagarajah, A. S. 2013. Translingual Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Celic, C., and K. Seltzer. 2013. Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide for Educators (Revised). New York: CUNY-NYSIEB. Accessed 22 May 2018. https://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Translanguaging-Guide-March-2013.pdf.

- Chimirala, U. M. 2017. “Teachers’ ‘Other’ Language Preferences: A Study of the Monolingual Mindset in the Classroom.” In Multilingualisms and Development: Selected Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi, India, edited by H. Coleman, 151–168. London: British Council.

- Clegg, J., and O. Afitska. 2011. “Teaching and Learning in Two Languages in African Classrooms.” Comparative Education 47 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1080/03050068.2011.541677.

- Coleman, H. 2017. “Development and Multilingualism: An Introduction.” In Multilingualisms and Development: Selected Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi, India, edited by H. Coleman, 15–34. London: British Council.

- Cook, G. 2010. Translation in Language Teaching: An Argument for Reassessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- De la Campa, J. C., and H. Nassaji. 2009. “The Amount, Purpose, and Reasons for Using L1 in L2 Classrooms.” Foreign Language Annals 42 (4): 742–759. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2009.01052.x.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2003. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration and Processing. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2007. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Duff, P. A., and C. G. Polio. 1990. “How Much Foreign Language is There in the Foreign Language Classroom?” The Modern Language Journal 74 (2): 154–166. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1990.tb02561.x.

- Durairajan, G. 2017. “Using the First Language as a Resource in English Classrooms: What Research From India Tells us.” In Multilingualisms and Development: Selected Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi, India, edited by H. Coleman, 307–316. London: British Council.

- Erling, E., L. Adinolfi, and A. K. Hultgren. 2017. Multilingual Classrooms: Opportunities and Challenges for English Medium Instruction in Low and Middle Income Contexts. London/Milton Keynes/Reading: British Council/Open University/Education Development Trust.

- Ferguson, G. 2003. “Classroom Code-switching in Post-colonial Contexts: Functions, Attitudes and Policies.” AILA Review 16 (1): 38–51. doi:10.1075/aila.16.05fer.

- Field, A. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. London: Sage.

- García, O. 2009. “Education, Multilingualism and Translanguaging in the 21st Century.” In Social Justice Through Multilingual Education, edited by T. Skutnabb-Kangas, R. Phillipson, A. K. Mohanty, and M. Panda, 140–158. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- García, O., and W. Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave.

- Government of India. 1961. Census of India. Vol 1, Part II-A(i), General Population Tables, New Delhi, India: Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India.

- Government of India. 2012. The Constitution of India. https://www.india.gov.in/my-government/constitution-india/constitution-india-full-text.

- Hall, G., and G. Cook. 2012. “Own-language Use in Language Teaching and Learning.” Language Teaching 45 (3): 271–308. doi:10.1017/S0261444812000067.

- Hall, G., and G. Cook. 2013. Own-language Use in ELT: Exploring Global Practices and Attitudes. London: British Council.

- Hewson, C., P. Yule, D. Laurent, and C. Vogel. 2003. Internet Research Methods. London: Sage.

- Jørgensen, J. N., M. S. Karrebæk, L. M. Madsen, and J. S. Møller. 2011. “Polylanguaging in Superdiversity.” Diversities 13 (2): 23–37. http://www.unesco.org/shs/diversities/vol13/issue2/art2.

- Kachru, Y. 1994. “Monolingual Bias in SLA Research.” TESOL Quarterly 28 (4): 795–800. doi: 10.2307/3587564

- Levine, G. S. 2003. “Student and Instructor Beliefs and Attitudes about Target Language Use, First Language Use, and Anxiety: Report of a Questionnaire Study.” The Modern Language Journal 87 (3): 343–364. doi:10.1111/1540-4781.00194.

- Lin, A. M. Y. 1996. “Bilingualism or Linguistic Segregation? Symbolic Domination, Resistance and Code Switching in Hong Kong Schools.” Linguistics and Education 8: 49–84. doi: 10.1016/S0898-5898(96)90006-6

- Liu, D., G. S. Ahn, K. S. Baek, and N. O. Han. 2004. “South Korean High School English Teachers’ Code Switching: Questions and Challenges in the Drive for Maximal Use of English in Teaching.” TESOL Quarterly 38 (4): 605–638. doi:10.2307/3588282.

- Macaro, E. 2001. “Analysing Student Teachers’ Codeswitching in Foreign Language Classrooms: Theories and Decision Making.” The Modern Language Journal 85 (4): 531–548. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00124

- Macaro, E. 2005. “Codeswitching in the L2 Classroom: A Communication and Learning Strategy.” In Non-native Language Teachers: Perceptions, Challenges and Contributions to the Profession, edited by E. Llurda, 63–84. Boston, MA: Springer.

- May, S. 2011. “The Disciplinary Constraints of SLA and TESOL: Additive Bilingualism and Second Language Acquisition, Teaching and Learning.” Linguistics and Education 22: 233–247. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2011.02.001.

- May, S. 2014. The Multilingual Turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and Bilingual Education. New York: Routledge.

- McIlwraith, H. 2013. Multilingual Education in Africa: Lessons from the Juba Language-in-Education Conference. London: British Council.

- Meganathan, R. 2017. “The Linguistic Landscape of New Delhi: A Precursor and a Successor of Language Policy.” In Multilingualisms and Development: Selected Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi, India, edited by H. Coleman, 225–238. London: British Council.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. 2009. Right to Education Act. New Delhi: Ministry of Law and Justice. http://righttoeducation.in/sites/default/files/Right%20of%20Children%20to%20Free%20and%20Compulsory%20Education%20Act%202009%20%28English%29%20%28Copiable_Searchable%29.pdf#overlay-context.

- Mohanty, A. K. 2009. “Perpetuating Inequality: Language Disadvantage and Capability Deprivation of Tribal Mother Tongue Speakers in India.” In Language and Poverty, edited by W. Harbert, S. McConnell, A. Miller, and J. Whitman, 102–124. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Mohanty, A. K. 2010. “Languages, Inequality and Marginalization: Implications of the Double Divide in Indian Multilingualism.” International Journal of Society and Language 205: 131–154. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2010.042.

- NCERT (National Council of Educational Research and Training). 2006. Position Paper of the National Focus Group on Teaching of English. New Delhi: National Council of Educational Research and Training.

- Probyn, M. 2009. “‘Smuggling the Vernacular into the Classroom’: Conflicts and Tensions in Classroom Codeswitching in Township/Rural Schools in South Africa.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 12 (2): 123–136. doi:10.1080/13670050802153137.

- Rahman, A. 2013. “Role of L1 (Assamese) in the Acquisition of English as L2: A Case of Secondary School Students of Assam.” In English Language Teacher Education in a Diverse Environment, edited by P. Powell-Davies, and P. Gunashekar, 215–222. London: British Council.

- Sembiante, S. 2016. “Translanguaging and the Multilingual Turn: Epistemological Reconceptualization in the Fields of Language and Implications for Reframing Language in Curriculum Studies.” Curriculum Inquiry 46 (1): 45–61. doi: 10.1080/03626784.2015.1133221

- Simpson, J. 2017. English Language and Medium of Instruction in Basic Education in Low- and Middle-income Countries: A British Council Perspective. London: British Council.

- Sridhar, S. N. 1994. “A Reality Check for SLA Theories.” TESOL Quarterly 28 (4): 800–805. doi:10.2307/3587565.

- Turnbull, M., and J. Dailey-O’Cain, eds. 2009. First Language Use in Second and Foreign Language Learning. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.