ABSTRACT

Guest editorial for the special issue ‘CLIL for all? Attention to diversity in bilingual education’.

1. Introduction and justification

The European approach to bilingual education – CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) – has been enthusiastically embraced as a potential lever for change and success in language learning. Over the course of the past two decades, it has become a well-established part of education systems across Europe and is now also being increasingly adopted in Latin American and Asian countries as the potential lynchpin to move from monolingual education systems to bilingual ones. It has also been heralded as a way to make bilingual language learning more accessible to all types of learners, as CLIL has been held to afford all students, regardless of social class and economic consideration, the opportunity to learn additional languages in a meaningful way. Many authors thus maintain that CLIL promotes social inclusion and egalitarianism, as the introduction of this approach in mainstream education provides a greater range of students with opportunities for linguistic development which they were previously denied (cf. Marsh Citation2002; Coyle, Hood, and Marsh Citation2010; Pérez Cañado Citation2020).

However, the initial mise-en-scène of CLIL in public schools across Europe points to a very different reality. Indeed, one of the chief concerns which have repeatedly underpinned CLIL discussions affects the lack of egalitarianism, which, according to authors like Bruton (Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2019) or Paran (Citation2013), is inherent in the application of this approach. In this sense, a notable set of scholars have sounded a note of caution as regards the level of self-selection in CLIL strands, with its corollary inadequacy for attention to diversity (Lorenzo, Casal, and Moore Citation2009). The thrust of their argument is that CLIL branches normally comprise the more motivated, intelligent, and linguistically proficient students and that these differences are conducive to prejudice and discrimination against non-CLIL learners.

Now that CLIL is steadily embedding itself in mainstream education and the move is increasingly being made from bilingual sections to fully bilingual schools, all learners experience foreign language learning both in language-driven and subject content classes and it consequently becomes incumbent on practitioners to cater to diversity and to ensure CLIL enhances language and content learning in over- and under-achievers alike. This has surfaced as major challenge which could seriously curtail – or even fatally undermine – everything that has been achieved in the previous decades of CLIL implementation. One of the greatest problems plaguing CLIL implementation at present, according to the latest research (cf. Madrid and Pérez Cañado Citation2018), is catering to diversity, as there is a lack materials, resources and methodological and evaluative guidelines to step up to it successfully. Thus, prior investigation documents the urgent need for a study on attention to diversity within CLIL in order to shed light on the issue of how (and if) CLIL works across different levels of attainment and what types of curricular and organizational practices can be implemented to cater to it.

The extremely meager amount of research which has thus far been conducted into attention to diversity in CLIL has only focused on the topic superficially and in passing, and not as the chief goal of any investigation (cf. the final article in this special issue for an overview of the main types of studies conducted to date on the topic). Qualitatively, studies have mostly polled stakeholder perspectives of the way in which CLIL programs are playing out and attention to diversity has surfaced as a key challenge (Mehisto and Asser Citation2007; Pena Díaz and Porto Requejo Citation2008; Fernández and Halbach Citation2011; Pérez Cañado Citation2016a, Citation2016b). In turn, quantitatively, research has only indirectly explored how CLIL is working in diverse social contexts, socioeconomic levels, and types of schools while examining the effects of CLIL in terms of intervening variables (Alejo and Piquer-Píriz Citation2016; Anghel, Cabrales, and Carro Citation2016; Shepherd and Ainsworth Citation2017; Madrid and Barrios Citation2018; Pavón Vázquez Citation2018; Pérez Cañado Citation2018; Rascón and Bretones Citation2018; Fernández-Sanjurjo, Fernández-Costales, and Arias Blanco Citation2019). However, none have examined in a full-blown way the resources, materials, classroom organization, methodologies, or types of evaluation that are being deployed to cater to diversity within CLIL schemes or the main teacher training needs in this area. Furthermore, none have been international comparative studies into this issue, which pool and contrast the knowledge base and experience on this issue of northern, southern, and central European monolingual contexts, where there is an even more conspicuous ‘shortage of research in CLIL’ (Fernández-Sanjurjo, Fernández-Costales, and Arias Blanco Citation2019, 2). These are precisely the niches that the present special issue seeks to address.

2. The backdrop: the ADiBE projects

In doing so, it reports on the results of four governmentally funded research projects (at the European, national, and regional levelsFootnote1), encompassed with the acronym ADiBE: Attention to Diversity in Bilingual Education. These projects aim to carry out a large-scale comparative study into the effects and functioning of Content and Language Integrated Learning across different levels of attainment in monolingual contexts in six European countries (Spain, Italy, Austria, Germany, Finland, and the UK). They approximate the topic of inclusion in CLIL programs from diverse and complementary perspectives.

Quantitatively, they examine the impact of CLIL programs on the FL, L1, and content achievement of three different levels of learners in terms of verbal intelligence, motivation, English level, and general academic performance to determine whether CLIL truly works with all students and how it is functioning with over-, normal, and under-achievers at the end of both Primary and Compulsory Secondary Education. In turn, qualitatively, they probe teachers’, students’, and parents’ satisfaction with all the curricular and organizational aspects which are being deployed to cater to diversity within CLIL schemes and carry out an analysis of the main teacher training needs in this area. The outcomes obtained within each monolingual context sampled in the study are compared and contrasted in order to determine in which scenarios the measures for attending to diversity are the most successful and, thereby, to learn from the best practices of others.

From a methodological standpoint, original materials have been designed with differentiation triangulation, multi-tiered activities, and interdisciplinary cross-fertilization. They include three levels of activity at phase 1 (following Bloom’s cognitive levels), three types of student-centered methodologies at phase 2 (Project-based Learning, Multiple Intelligence Theory, and Cooperative Learning); and three levels of outputs at stage 3 (e.g. infographics, interactive presentations, or videos). They are interdisciplinary in nature, with each project involving L1, L2, and three non-linguistic area subjects and with all these subjects building on and supporting each other. A teacher training course has also been devised, with a three-pronged structure (theoretical foundations, examples of materials and best practices, and task design) which guides participants from more controlled to freer practice, until they can design their own didactic unit to cater for diversity in CLIL classrooms. Finally, from an ICT-based perspective, pedagogical videoguides have been drawn up to provide key tips based on the outcomes of the studies for teachers, students, teacher trainers, parents, and authorities to contribute to making CLIL accessible to all. An app is also being articulated which will allow teachers to take a personalized diagnosis of their main needs to cater for diversity and will redirect them to useful materials designed within the project to step up to this challenge.

This special issue reports specifically on the qualitative side of the overarching investigation. It aims to identify the chief difficulties and best practices in catering for diversity in CLIL from a supranational perspective through the use of questionnaires, focus group interviews, and classroom observation conducted with teachers, students, and parents in the afore-mentioned six European countries. It thus attempts to shed light on the issue of how (and if) CLIL works across different levels of attainment, what types of curricular and organizational practices can most effectively be implemented to cater to diversity, and which teacher education issues need to be most urgently addressed. Data, methodological, investigator, and location triangulation are employed in order to paint a comprehensive and empirically valid picture of where fully bilingual schemes stand in monolingual contexts across Europe, drawing a precise description of the way in which CLIL is working with different types of achievers.

3. Clarifying the concept of diversity: The DIDI framework

What exactly does the ADiBE Project understand by diversity or inclusion? Given their increasing growth, the potential of bilingual education programs to serve as an inclusive setting remains high. However, paradoxically, scant research, and practice have touched on the issue of diversity and differentiation, with only perfunctory attention being given to pedagogical considerations which accommodate learner integration in bilingual scenarios. We thus clearly stand in need of articulating a conceptual framework to approach diverse students in an asset-oriented and inclusive manner and of enacting dynamic, effective, and responsive pedagogical strategies to meet bilingual students’ needs.

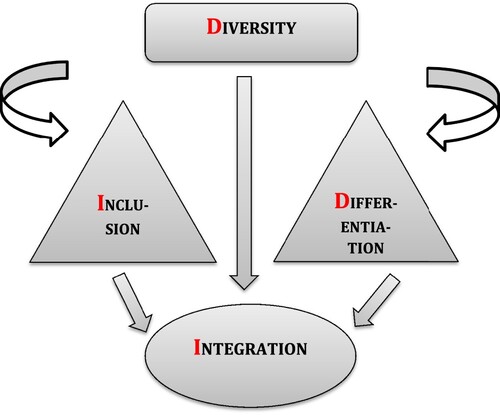

These guidelines are grounded within the framework of diversity, inclusion, differentiation, and integration (what we term DIDI) within a bilingual environment (cf. ). Since these concepts are complex and multi-faceted, let us briefly delineate exactly what is understood by each one in the ADiBE Project in order to fully grasp their manifold dimensions.

Diversity is the initial, overarching umbrella term. It entails providing an adequate education to all students, bearing in mind:

their personal traits;

cognitive, cultural, and linguistic needs;

individual differences in terms of learning styles;

diversity in experiences, knowledge, and attitudes;

varying achievement levels, learning paces, and intellectual capacity;

diverging interests, motivations, and expectations;

and different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds (Julius and Madrid Citation2017; Madrid and Pérez Cañado Citation2018).

Diversity is, in turn, grounded on the principles of inclusion and differentiation (Julius and Madrid Citation2017). Inclusive education, like diversity, in its broad definition, transcends the notion of disability ‘to include learner diversity on the grounds of students’ varied ethnic/race, linguistic, biographical and developmental characteristics’ (Liasidou Citation2013, 11). It is regarded as an educational model that aims to respond to the learning needs of all students (Martín-Pastor and Durán-Martínez Citation2019), especially those on the fringes, who are at risk of marginalization and social exclusion (Madrid and Pérez Cañado Citation2018). It approaches diversity from an asset-based perspective, viewing it as a source of enrichment and as an opportunity to overcome potential barriers in educational development (Cable, Eyres, and Collins Citation2006; Madrid and Pérez Cañado Citation2018). It thus provides effective learning opportunities for all students, focuses on achievement, and helps operate a procedural shift in the student from ‘outsider to participant’ (Cioè-Peña Citation2017, 906).

Differentiation, in turn, also targets students with diverse abilities and backgrounds. Roiha (Citation2014) considers it a phenomenon within inclusive education and a synthesis of diverse theories, such as Gardner’s Multiple Intelligence Theory (MIT) and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The chief aim of differentiation is to address each pupil’s individual abilities and needs, and to tailor teaching to correspond to each ZPD. It thus involves attending to both underachieving and gifted pupils (Roiha Citation2014).

Finally, a conflation of these three aspects (diversity, inclusion, and differentiation) leads to the integration of students with diverse ability levels (Cioè-Peña Citation2017). As Madrid and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018, 245) put it, ‘Both inclusion and attending to diversity are associated with the phenomenon of integration, which is a consistent response to the diversity of student needs’. The four concepts of our DIDI framework dovetail in order to reshape educational structures and safeguard equitable access to CLIL for all students.

4. Contents of the special issue

Against this research and terminological backdrop, the results of the ADiBE Project by specific country and from a supranational comparative perspective are presented. The volume kicks off with an initial article by María Luisa Pérez Cañado, Diego Rascón Moreno, and Valentina Cueva López which shares the three sets of questionnaires, interviews, and observation protocols that have been originally designed and validated for the project. Their research-based design and double-fold validation process are carefully rendered and the actual instruments are then placed at the service of the broader educational community for further iterations so that replication can ensue in all contexts and personalized diagnoses of teacher needs to cater for diversity can be carried out.

The outcomes by country are then rendered, beginning with the UK. Here, Do Coyle, Kim Bower, Yvonne Foley, and Jonathan Hancock explore diversity and inclusion in classroom practices in the UK through a case study at secondary education level which conflates two types of bilingual learning: CLIL and EAL (English as an Additional Language). The pluriliteracies lens is applied to identify optimal conditions for teaching and learning in the bilingual education scenario and to enable diverse learners to engage in more significant learning, develop academic literacies, and establish stronger learning partnerships with their teachers.

Silvia Bauer-Marschallinger, Christiane Dalton-Puffer, Helen Heaney, Lena Katzinger, and Ute Smit then delineate CLIL policy and practice in Austria and report on a mixed-methods study with secondary education teachers and students, employing questionnaires and focus group interviews, into self-reported experiences with diversity and the pedagogical practices harnessing it in CLIL classrooms. An interesting tension transpires between the notions of segregation and egalitarianism, and a rift is documented between teacher and learner views on student-centeredness in CLIL lessons and the use of scaffolding, peer support, or the L1 as a fallback strategy. Differences between the two chief contexts in which Austrian CLIL is applied are also ascertained, deriving in a noteworthy set of pedagogical implications for both grassroots practice and teacher development in this context.

Teacher and student outlooks are also explored in Finland by Tarja Nikula, Kristiina Skinnari, and Karita Mård-Miettinen. As in Austria, the ethos of equality is firmly entrenched in the Finnish educational system, and this ripples out over the concept of differentiation in CLIL contexts. Diversity policies in this country are initially explored and the study is subsequently reported on, in this case, through the use of teacher and student interviews. Unique traits such as the high-achieving nature of CLIL learners and the significance of upward differentiation stand out in the analysis. The lack of topicalization of diversity is also salient in the outcomes, concomitantly with the need to set in place strategies for individualized support, learning paces, and styles.

A similar predominance of high-performance learners within an explicit agenda of selectivity can be traditionally found in the German context, which is unpacked in the article by Philipp Siepmann, Dominik Rumlich, Frauke Matz, and Ricardo Römhildz. An increasing heterogeneity in the student body is now, however, being ascertained and the study with teachers and students which is rendered here delves deeper, through the use of questionnaires, interviews, and classroom observation, into the methods, materials, classroom arrangements, scaffolding, and assessment techniques which are being set in place to attend to diversity in CLIL streams. Interesting implications ensue, with a special onus on the use of digital media to foster the educational success of linguistically and academically diverse students.

The Italian context contrasts starkly with the previous ones and the article by Yen-Ling Teresa Ting offers extremely relevant insights into how diversity is being tackled in a firmly entrenched monolingual area such as the southern Italian one. The focus here is on students and, through surveys and interviews, the study taps into learners’ perceptions on methods, materials, groupings, awareness of diversity, teachers’ competences, or school-level organization. The most outstanding implications are signposted for the reader, both from a methodologically-oriented perspective and from the teacher education prism.

Also based in southern Europe, the study which Antonio Vicente Casas Pedrosa and Diego Rascón Moreno’s article chronicles centers specifically on Spain. After framing the investigation against the backdrop of this country’s highly inclusive approach to bilingual education, the authors carry out a detailed analysis of teacher and student views on diversity in CLIL programs within five main fields of interest: linguistic aspects, methodology and types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher coordination and development. Across-cohort comparisons are also carried out in order to determine whether stakeholder opinions are aligned or divergent. The chief pedagogical implications to continue pushing the CLIL agenda forward in the country are outlined, a particularly pertinent remit as bilingual education is increasingly being mainstreamed in the Spanish context.

If the previous articles drilled down into each specific country involved in the ADiBE project, the final one by María Luisa Pérez Cañado looks at the overall results in conflation. It tracks a cohort of 2,562 teachers, students, and parents at 59 sites in the six afore-mentioned European countries. After offering the global results by cohort, it carries out a cross-European comparison of stakeholder perspectives on catering to diversity within CLIL programs. Across- and within-cohort analyses are conducted and valuable lessons are gleaned on the implementation and teacher development actions currently being set in place within bilingual education from a pan-European perspective. The article showcases the main lessons learnt from the diverse contexts, identifies scope for improvement across countries, and establishes the future priorities which an inclusive education reform agenda necessitates in bilingual education scenarios.

Thus, taken jointly, the results presented herein will thereby yield important information on a substantial number of questions which are crucial for the successful development of CLIL programs in fully bilingual schools: Does CLIL have the potential to work with all types of learners? Which are the main difficulties that teachers face in catering to diversity within CLIL programs? What kinds of measures are being set in place to cater to diversity in monolingual contexts? What differences/similarities can be discerned between the measures implemented in northern, central, and southern Europe? Which measures are working better and why? What can we learn from the best practices of others on attention to diversity in CLIL in order to improve our own language learning situation and educational system? None of these questions has been explicitly addressed in prior studies; hence the contribution of this special issue.

Its ultimate aim is to foster the integration of all students, regardless of their socioeconomic status, educational background, or achievement level, and to contribute to making CLIL accessible to all. It will pool the insights of some of the most renowned researchers in the field and foster international dialogue in order to promote a multi-tiered system of support to cater to diversity in CLIL and promote the success of more vulnerable and underserved learners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

María Luisa Pérez Cañado

Dr. María Luisa Pérez Cañado is Full Professor at the Department of English Philology of the University of Jáen, Spain, where she is also Rector's Delegate for European Universities and Language Policy. Her research interests are in Applied Linguistics, bilingual education, and new technologies in language teaching. She is currently coordinating the first intercollegiate MA degree on bilingual education and CLIL in Spain, as well as four European, national, and regional projects on attention to diversity in CLIL. She has also been granted the Ben Massey Award for the quality of her scholarly contributions regarding issues that make a difference in higher education.

Notes

1 Project 2018-1-ES01-KA201-050356, supported by the European Union; RTI2018-093390-B-I00, funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades; and 1263559 and P18-RT-1513, financed by the Junta de Andalucía.

References

- Alejo, R., and A. Piquer-Píriz. 2016. “Urban vs. Rural CLIL: An Analysis of Input-related Variables, Motivation and Language Attainment.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 29 (3): 245–262.

- Anghel, B., A. Cabrales, and J. M. Carro. 2016. “Evaluating a Bilingual Education Program in Spain: The Impact Beyond Foreign Language Learning.” Economic Inquiry 54 (2): 1202–1223.

- Bruton, A. 2011a. “Are the Differences Between CLIL and Non-CLIL Groups in Andalusia due to CLIL? A Reply to Lorenzo, Casal and Moore (2010).” Applied Linguistics 2011: 1–7.

- Bruton, A. 2011b. “Is CLIL So Beneficial, or Just Selective? Re-evaluating Some of the Research.” System 39: 523–532.

- Bruton, A. 2013. “CLIL: Some of the Reasons Why … and Why Not.” System 41: 587–597.

- Bruton, A. 2015. “CLIL: Detail Matters in the Whole Picture. More Than a Reply to J. Hüttner and U. Smit (2014).” System 53: 119–128.

- Bruton, A. 2019. “Questions About CLIL Which Are Unfortunately Still Not Outdated: A Reply to Pérez-Cañado.” Applied Linguistics Review 10 (4): 591–602.

- Cable, C., I. Eyres, and J. Collins. 2006. “Bilingualism and Inclusion: More Than Just Rhetoric?” Support for Learning 21 (3): 129–134.

- Cioè-Peña, M. 2017. “The Intersectional Gap: How Bilingual Students in the United States Are Excluded from Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (9): 906–919.

- Coyle, D., P. Hood, and D. Marsh. 2010. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fernández-Sanjurjo, J., A. Fernández-Costales, and J. M. Arias Blanco. 2019. “Analysing Students’ Content-learning in Science in CLIL vs. Non-CLIL Programmes: Empirical Evidence from Spain.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22 (6): 661–674.

- Fernández, R., and A. Halbach. 2011. “Analysing the Situation of Teachers in the Madrid Autonomous Community Bilingual Project.” In Content and Foreign Language Integrated Learning: Contributions to Multilingualism in European Contexts, edited by Y. Ruiz de Zarobe, J. M. Sierra, and F. Gallardo del Puerto, 103–127. Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang.

- Julius, S., and D. Madrid. 2017. “Diversity of Students in Bilingual University Programs: A Case Study.” The International Journal of Diversity in Education 17 (2): 17–28.

- Liasidou, A. 2013. “Bilingual and Special Educational Needs in Inclusive Classrooms: Some Critical and Pedagogical Considerations.” Support for Learning 28 (1): 11–16.

- Lorenzo, F., S. Casal, and P. Moore. 2010. “The Effects of Content and Language Integrated Learning in European Education: Key Findings from the Andalusian Bilingual Sections Evaluation Project.” Applied Linguistics 31 (3): 418–442.

- Madrid, D., and E. Barrios. 2018. “CLIL Across Diverse Educational Settings: Comparing Programmes and School Types.” Porta Linguarum 29: 29–50.

- Madrid, D., and M. L. Pérez Cañado. 2018. “Innovations and Challenges in Attending to Diversity Through CLIL.” Theory Into Practice 57 (3): 241–249.

- Marsh, D. 2002. CLIL/EMILE. The European Dimension. Actions, Trends, and Foresight Potential. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Martín-Pastor, E., and R. Durán-Martínez. 2019. “La inclusión educativa en los programas bilingües de educación primaria: Un análisis documental.” Revista Complutense de Educación 30 (2): 589–604.

- Mehisto, P., and H. Asser. 2007. “Stakeholder Perspectives: CLIL Programme Management in Estonia.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10 (5): 683–701.

- Paran, A. 2013. “Content and Language Integrated Learning: Panacea or Policy Borrowing Myth?” Applied Linguistics Review 4 (2): 317–342.

- Pavón Vázquez, V. 2018. “Learning Outcomes in CLIL Programmes: a Comparison of Results Between Urban and Rural Environments.” Porta Linguarum 29: 9–28.

- Pena Díaz, C., and M. D. Porto Requejo. 2008. “Teacher Beliefs in a CLIL Education Project.” Porta Linguarum 10: 151–161.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2016a. “Teacher Training Needs for Bilingual Education: In-service Teacher Perceptions.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 19 (3): 266–295.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2016b. “Are Teachers Ready for CLIL? Evidence from a European Study.” European Journal of Teacher Education 39 (2): 202–221.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2018. “The Effects of CLIL on L1 and Content Learning: Updated Empirical Evidence from Monolingual Contexts.” Learning and Instruction 57: 18–33.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2020. “CLIL and Elitism: Myth or Reality?” The Language Learning Journal 48 (1): 4–17.

- Rascón, D. J., and C. M. Bretones. 2018. “Socioeconomic Status and Its Impact on Language and Content Attainment in CLIL Contexts.” Porta Linguarum 29: 115–135.

- Roiha, A. S. 2014. “Teachers’ Views on Differentiation in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Perceptions, Practices and Challenges.” Language and Education 28 (1): 1–18.

- Shepherd, E., and V. Ainsworth. 2017. English Impact: An Evaluation of English Language Capability. Madrid: British Council.