ABSTRACT

CLIL programmes are firmly established in German schools. While empirical studies have provided insights into aspects such as language- and content-related achievement, motivation, and cultural learning, little is known about classroom practices and students’ perceptions thereof. Using ADiBE’s instruments, this mixed-method study explores how teachers and students view differentiation and diversity-sensitive CLIL classroom practices in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. In total, 31 teachers and 595 students shared their experiences concerning methods, materials, classroom arrangements, scaffolding, and differentiation techniques used to foster the educational success of linguistically and academically diverse students. A classroom observation (45 minutes) geography lesson and an accompanying focus-group interview with six students allowed for deeper insights into specific practices and how they were perceived. The results show (how) diversity is frequently taken into account in various ways, yet there are also substantial challenges in catering to a diverse student population. The findings of this first phase of the ADiBE project lay the groundwork for further research on heterogeneity in CLIL and will be used as a stepping stone for the creation of research-informed CLIL teaching materials and teacher-training resources.

1. Introduction

In Germany, CLIL (or bilingual education as it is called in the country) dates back to the 1960s, but was only implemented on a noticeable scale in the 1990s. While schools are generally allowed to use flexible, episodic forms of CLIL across all subjects, such CLIL lessons, phases, modules, projects, extra-curricular activities, etc. remain comparatively rare outside of CLIL programmes or other more institutionalised CLIL-related initiatives such as CertiLingua (MSB Citation2021a) and a few binational, immersion or European schools. The majority of CLIL teaching, and also its most intense form, is realised in streams with a maximum of three simultaneous CLIL subjects at secondary schools (KMK Citation2013).

CLIL programmes are never compulsory as they come with additional lessons, increased study load and higher cognitive demands, all of which contribute to self-selection processes. At the same time, CLIL is also seen as a way to support language-apt students (KMK Citation2013), who exhibit above-average grades. As a result, while there are no admission requirements and the decision to enter a bilingual stream is up to students’ parents, (self-)selection processes and creaming become apparent when looking at CLIL student populations in Germany (cf. Dallinger, Jonkmann, and Hollm Citation2018; Frisch Citation2021; Rumlich Citation2016).

However, schools in Germany generally display an increase in the degree of heterogeneity among their students (Baumert and Köller Citation1998), which is also true for CLIL schools and streams despite substantial selection processes. Initiatives such as ‘CLIL for all’ (‘Bilingual für alle’; MSB Citation2021b) and the expansion of CLIL to less academically oriented types of school (Diehr and Rumlich Citation2021) further contribute to changes in the traditional composition of the CLIL student population. At the same time, ‘it is still largely unclear how exactly the educational potential of CLIL and bilingual education materialises; for whom, under what conditions, at what costs and what educational objectives can be attained’ (Rumlich Citation2020, 116).

Against this background, the international Erasmus+ ADiBE (Attention to Diversity in Bilingual Education) – CLIL for All project (Pérez Cañado et al. Citation2019) was formed in order to shed light on the area of heterogeneity and differentiation in CLIL, which has received very little attention in European CLIL in general and in Germany in particular. There are many ways in which learners can be diverse with varying degrees of influence on learning and achievement. In the context of the ADiBE project, however, particular attention was devoted to different levels of subject-related competences and language command. They are a key feature of all CLIL classes, no matter how homogenous they might be otherwise due to specific local contexts (determined by streaming, type/location of the school, etc.). In addition, language as well as subject-specific competences constitute highly influential factors in predicting learning success and overall achievement in general and in the context of content and language integrated learning in particular.Footnote1

The German sub-study was conducted in the most populous federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), which has by far the largest number of CLIL schools and is often considered a trailblazer in this area (see initiatives such as ‘CLIL for All’ or CertiLingua; MSB Citation2021a, Citation2021b). On the basis of student and teacher questionnaires together with one lesson observation and interviews, the present study provides comprehensive insights into the current state of diversity-sensitive CLIL practices. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first mixed-method study in Germany to investigate in a multi-perspective manner how the heterogeneity among students is addressed in CLIL classes.

2. CLIL in Germany

2.1. Educational context

In Germany, CLIL refers to education in which subject lessons (i.e. geography, history, social sciences, science, etc.) are taught in both the foreign language and, to a varying degree, also in German to develop subject-specific literacy in two languages (‘doppelte Sachfachliteralität’; Vollmer Citation2010, 133f). Hence, CLIL in Germany is bilingual education in the actual sense of the word. It is based on the curriculum of the respective subject, often supplemented by sample materials and/or recommendations by the respective Ministry of Education (e.g. MSW Citation2012). These resources illustrate (additional) CLIL-related educational objectives (e.g. subject-specific literacy in the foreign language, culture-related learning goals, etc.; Diehr and Rumlich Citation2021) and how they might be attained; a particular focus is placed on language-sensitive teaching (Leisen Citation2010) and academic language proficiency (QUA-LIS NRW Citation2021). For some CLIL subjects in some federal states, textbooks are available. To cater to the additional learning goals and the resulting challenges of the foreign language, CLIL subjects are timetabled with three instead of two lessons per week. In view of the depicted challenges and the wealth of learning objectives, CLIL classes are highly demanding for teachers and learners alike.

In Germany, teachers usually study two subjects plus educational sciences and complete both a Bachelor’s and Master’s teaching programme. As a result, prototypical CLIL teachers usually have a teaching degree in both the content subject and the target language, but no specific CLIL knowledge or training, for instance, with respect to subject-specific foreign-language literacy. Further qualifications can be obtained at some universities and teacher training centres. The popularity of combining languages with geography, history, social sciences, or biology is the major reason why these are the predominant CLIL subjects. English is by far the most popular CLIL language, followed by French.

2.2. Diversity of (German) CLIL students: existing research gaps

Although (self-)selection is observable and high achievers are openly encouraged to join CLIL programmes as a central measure to support language-apt students (KMK Citation2013), there are no admission criteria for CLIL streams and they are generally open to all students. Furthermore, these programmes are designed to be flexible, so that students can switch to regular strands (MSB Citation2021a), even though in practice they are discouraged to do so. On the basis of the broad and consistently positive experience with bilingual education (MSB Citation2021b), the Ministry of Education of NRW has been advertising the idea of ‘CLIL for All’ since 2007 (Mentz Citation2008). Hence, CLIL streams are in fact becoming more inclusive and their student population increasingly diverse, also outside of these initiatives (Breidbach and Viebrock Citation2012).

Yet, there is very little empirical research on heterogeneity and how it is dealt with in CLIL streams in Germany (Apsel Citation2012; Küppers and Trautmann Citation2013; Ohlberger and Wegner Citation2018), an exception being Abendroth-Timmer (Citation2009) on CLIL modules involving romance languages. Distantly related research from Canadian immersion programmes on necessary prerequisites for scholastic success suggests that there are none in particular, which is backed up by studies on the performance of weak learners (Genesee Citation2007; Fortune, Citation2011; Wode Citation1995). Studies on unselected students by Pérez Cañado (Citation2020) in a monolingual Spanish context and by Denman, van Schooten, and de Graaff (Citation2018) in non-academic streams at vocational school in the Netherlands indicate substantial benefits of CLIL without negating accompanying challenges, especially in the latter case. These findings are generally corroborated by German studies from Realschule (Glaap Citation2001; Schrandt Citation2003), a medium academic type of secondary school, and a classroom study on bilingual modules at a Hauptschule, the least academic type of school in the German school system (Schwab Citation2013; Schwab, Keßler, and Hollm Citation2014). The latter also identifies beneficial teaching principles to facilitate successful learning for weaker learners, such as illustrativeness, proceeding in small steps including regular repetition, student-centredness and interactional space for student participation, simplification/didactic reduction, and adequate language-sensitive preparation of subject matter. The majority of these also informed the ADiBE project (Pérez Cañado et al. Citation2019) on heterogeneity in CLIL.

All in all, the results reported above are an indication of the potential that CLIL might bear for unselected students and mixed-ability groups that have not been in the focus of CLIL programmes and research, although they ‘may well require additional scaffolding and special support to master the challenges of CLIL’ (Rumlich Citation2020, 116). Whether and how these and other kinds of differentiated and diversity-sensitive teaching are already being implemented in current classroom practice is the focus of the initial phase of ADiBE (Pérez Cañado et al. Citation2019), the first international project on heterogeneity and diversity in bilingual education and CLIL.

3. Research question

This study aims to explore how competence-related diversity and resulting learners’ needs are addressed in German CLIL classrooms and focuses on practices such as differentiated planning and teaching, individualisation, scaffolding, as well as the use of (digital) media to support learning. It seeks to answer the question: What are (the two main stakeholders’, i.e. teachers’ and students’, perceptions of) current measures taken to create diversity-sensitive, differentiated learning environments in CLIL lessons? Specifically, this study will concentrate on

content and language learning (i.e. how they are supported through scaffolding and other strategies),

methodology and grouping (i.e. how learning environments are designed, students are grouped and activities are structured),

materials and resources (i.e. their availability and use with regards to catering to individual differences),

assessment (i.e. how individual differences are considered in formative and summative assessment).

4. Method

The German sub-study used the research design and instruments of ADiBE (Pérez Cañado et al. Citation2019), following a multi-perspective and partially triangulated approach. It focuses, first, on the perceptions of teachers and students of their CLIL lessons in general (survey) and, second, more in-depth on the perspectives of one teacher and their students on one specific researcher-observed CLIL lesson (see Pérez Cañado et al. in this issue for a more comprehensive methodological account of ADiBE).

4.1. Research design and data analysis procedures

A mixed-methods approach was employed to include multiple perspectives, combining a variety of data-gathering procedures: Questionnaires, interviews, and the observation of an exemplary lesson. The aim of this design was to obtain a broad and general overview on the basis of a survey (incorporating learner and teacher questionnaires) and supplement this with more detailed context-specific insights from classroom observations and corresponding learner and teacher interviews.

The quantitative survey was conducted at 14 schools with considerable spread over NRW, including more rural and more urban areas in order to reduce location bias. The questionnaires developed for ADiBE were translated into German and, if necessary, items were adapted to suit the German CLIL context or excluded in case they did not apply to avoid confusion or unreliable data. The instrument consists of multiple sections (see a-d above) and included 53 items in total, with some semi-open and open questions, yet most of them were to be answered on six-point Likert scales (from ‘1’ indicating ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘6’ indicating ‘strongly agree’). The quantitative data was analysed with SPSS Statistics (version 27) and will be made comprehensively accessible on the basis of mean values with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) in order to obtain an information-rich general overview with respect to (dis)agreement among teachers’ and students’ perceptions of how diversity is addressed in CLIL lessons. (Non-)overlapping CIs will be used as indicators of (dis-)agreement.

The quantitative survey was enriched by qualitative data gathered through the observation (protocol) of an exemplary CLIL geography lesson and corresponding stakeholder interviews to obtain in-depth insights into (their perceptions of) CLIL practice catering to diversity. The topic of the ninth-grade lesson was demographic transition in India due to shifts in age structure. With a special focus on a population diagram, the central learning objective was to foster students’ skills of interpreting the demographic structure of India. Two guest researchers noted down their observations in a standardised ADiBE observation scheme. The stakeholder interviews followed the ADiBE guidelines and were conducted separately after the lesson. The teacher interview focused on planning decisions and common teaching practice that informed both the exemplary lesson as well as their CLIL teaching in general. In the focus group interview with six students who represented different levels of ability regarding subject-related competences and language proficiency, the students were asked to reflect on their experiences and perceptions in conjunction with the observed CLIL geography lesson and CLIL lessons in general.

In keeping with Germany’s strict data protection and privacy regulations, notes were taken throughout the lesson and the interviews, but no recordings were made. In line with the other ADiBE sub-projects, the qualitative data was analysed following the principles of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). To increase objectivity or inter-subjectivity, respectively, two researchers were involved in the lesson observations, the interviews and the analysis of the data.

4.2. Sample

The German sample (n = 626) accounted for 24.8% of the ADiBE sample (N = 2,526) and was comprised of 31 teachers (10.5% of the ADiBE sample) and 595 students (31.8% of the ADiBE sample). Missing cases were below 5% across all variables and excluded in a casewise manner.

All teachers’ first language was German and they reported a C1 (16.1%) or C2 (83.9%) level of English. Regarding the amount of work experience after their pre-service teacher training, the largest cohort was 1–10 years (41.9%), followed by 11–20 years (29%) and less than one year (16.1%). The majority of teachers had taught CLIL for 1–5 years (22.6%) or 6–10 years (22.6%). All but one teacher (96.8%) had studied English, all but two their CLIL content subject (93.6%). The majority of the teachers taught history (71%), followed by geography (29%) and social sciences (29%); the numbers equal more than 100% as teachers may study and/or teach more than two subjects.

The student cohort was comprised of 192 male (32.3%), 397 female (66.7%) and 6 diverse students (1%). An age breakdown reveals that the largest group of students were 13-year-olds (seventh/eighth grade, 25.4%), followed by 14-year-olds (eighth/ninth grade, 21.7%) and 12-year-olds (sixth/seventh grade, 17.7%). CLIL programmes in Germany usually start in seventh grade after two years of preparatory classes with one or two extra English lessons in addition to the usual four to five English lessons a week. About a quarter of the student population spoke languages other than German at home, with English (9.9%) being the most frequent, followed by Turkish (1.8%) and Arabic (0.9%) as well as a variety of other languages (12.5% in total).

For the case study, a Gymnasium (most academic type of school, predominant environment for CLIL streams) in the highly urban Ruhr area was chosen, one of Germany’s most densely populated and diverse agglomerations. Since it was not possible to choose a school based on their quantitative data as they remained anonymous in the survey, the school was selected based on its profile: It was not only among the very first in North-Rhine Westphalia to offer a bilingual stream with English as the target language in the 1970s, but can also be regarded as a trailblazer for diversity in CLIL. Unlike most CLIL programmes in Germany, bilingual education was basically mainstreamed from the outset, with three to four bilingual classes per year in contrast to the usual one or two. As a consequence, CLIL classes at this school have always been more heterogeneous and the school has rich CLIL experience.

The observed CLIL lesson was conducted in a ninth-grade geography class with 23 students. We had asked for an ‘average’ CLIL class with a noticeable, but at this school prototypical level of heterogeneity among students and considerable CLIL experience (they were in their third year of CLIL). The focus group consisted of six students, 14–15 years of age, half of them female. Languages spoken by the students at home besides German were Russian, Persian and Arabic. In addition to geography, they had been taking CLIL classes in biology and politics and were therefore able to compare different approaches across subjects and teachers. Their teacher of English and geography (without formal CLIL training) belonged to the category of 1–5 years of CLIL teaching experience.

5. Results

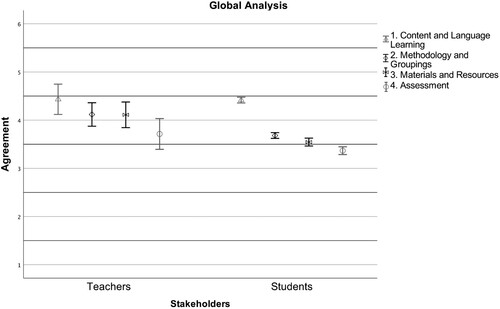

A global analysis of the entire item subsets (see a-d above) shows that they rank in the same order for teachers and students, with the teachers being more highly positive in their perceptions than the students. The perceptions of content and language support were most positive in both groups (). However, there was noticeable disagreement between the stakeholders regarding methodology and materials, plus a tendency towards disagreement on assessment.

Figure 1. Overall stakeholder perceptions (according to item subsets) of diversity-sensitive CLIL practice (1 = strongly disagree; bars represent 95% CI).

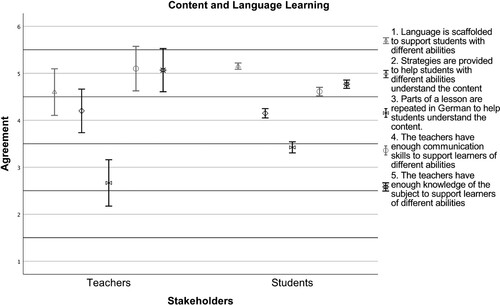

(A) Content and language learning

The overall perception of the diversity-sensitive support of content and language learning was positive (). Both stakeholder groups say that linguistic scaffolding is provided to support learners of different abilities and parts of the lesson are repeated in German to help students understand the subject-matter content, with the students’ agreement being even higher than the teachers’. With regard to content scaffolding/learning strategies, agreement was slightly lower among both stakeholder groups. Significant disagreement between teachers and students was found on whether parts of the lesson are repeated in German to help students understand the content. Here, the students perceived this strategy to be more common than the teachers. Students and teachers also tended to disagree on whether the teachers’ communication skills were sufficient to support learners of different abilities, with the teachers’ agreement being higher than the students’.

Figure 2. Stakeholder perceptions of diversity-sensitive support of content and language learning (1 = strongly disagree; bars represent 95% CI).

The qualitative data provided an additional perspective on how content and language learning is supported in CLIL classes. The observers estimated that the group was moderately diverse regarding their linguistic proficiency and academic achievement. Scaffolding was used extensively in the lesson to aid students in dealing with, and communicating about, the population diagram. For instance, the students were given a skills page on this diagram type with useful phrases to serve as output scaffolds. The task of interpreting the diagram carried out in pair work gave students an opportunity to support each other in preparing their report. As a result, there was no immediate necessity for repetition or auxiliary use of German during the entire lesson – at the same time, subject-specific literacy development in German as a major goal of German CLIL classes was also not explicitly supported. The teacher displayed a high level of both communication skills in basic interpersonal communication (BICS) and cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP; Cummins Citation1979) throughout the lesson. She modelled correct language usage and gave her students positive and encouraging feedback on their use of English. The teacher also showed considerable flexibility when briefly interrupting the pair work phase upon realising that several pairs were struggling with the task. The teacher then modelled the task by offering a step-by-step guide that served as a process scaffold.

In the interview, the teacher stressed that it was sometimes difficult to teach groups with different proficiency levels in the CLIL language and added that it was particularly challenging in the eighth grade when students with different levels of linguistic competence start CLIL geography. With regard to this specific subject, the teacher observed that mixed language skills became particularly noticeable when dealing with topics of physical rather than human geography. In contrast to the survey results, the teacher found it less demanding to cater to different levels of academic competence and subject knowledge than to different linguistic abilities as differentiation was easier on content level. At the beginning, she found it more challenging to incorporate differentiated and diversity-sensitive learning in CLIL than in parallel monolingual German geography classes. However, by the time the study was conducted, she had since developed a routine and the difficulties had vanished. A major obstacle to learning in the foreign language that the teacher was still grappling with was to adequately support newcomer students such as refugees, for instance. Some of these students must attend German as a second language classes at the same time and cannot regularly partake in the geography lessons. To address this problem, the teacher noted that she offered translations in the students’ first languages (e.g. Arabic) for self-study purposes. In the observed class, however, there were no newcomer students present.

To support language learning, the teacher reported that she made extensive use of linguistic scaffolding in her lessons. She noted that this applied to both CLIL and monolingual German geography lessons, since she considered language-sensitive learning in content subjects equally important in the predominant language of schooling. As examples of scaffolding techniques she used to foster language learning, she mentioned skills pages, sample texts and writing frames to raise her students’ awareness of the generic features of academic writing and subject-specific genres. The teacher also stated that she provided handouts with useful phrases as output scaffolds to students to lower inhibitions and the threshold to actively participate in discussions. Regarding the use of German in CLIL lessons, the teacher reported that she avoided teaching entire lessons in German, but purposefully used code-switching to ensure the comprehension of complicated topics, such as desertification processes. In such instances, she intentionally separated content from language learning and introduced the topic in German before switching back to English. The teacher also stressed the use of mediation tasks to develop bilingual discourse competence as part of subject-specific literacy.

The students confirmed the observation that they had different levels of English proficiency and stressed that some even had a much lower proficiency than the class average. One student explained that some students were very shy or reluctant to participate in classroom discussions. Some of the interviewees admitted that they were afraid that errors would be sanctioned by the teacher. What contributed to their anxiety was that their former teacher had used spontaneous tests as a means to exert pressure on the students. Whereas the students emphasised that their current teacher was very supportive and gave them encouraging feedback, some still feared being judged by their peers.

In general, the group said that the amount of German used in CLIL depended on the subject. In politics, the content would often require additional clarification in German, so estimates of the amount of German used in their politics lessons were as high as 80%. This number was considerably lower and almost zero for other teachers and CLIL subjects. The group also mentioned considerable differences in how teachers use German: While other teachers used German occasionally to support understanding, their geography teacher tried to use English throughout while actively trying to ensure that everyone was able to follow her lesson. The group generally viewed teachers critically who insisted on using English all the time and suppressed any use of German.

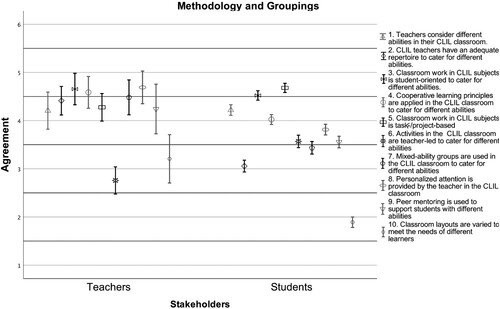

(B) Methodology and types of groupings

There was significant disagreement on a range of items in this subset of the questionnaire (). While teachers and students generally agreed that teachers considered students with different abilities in their lessons, there was a substantial discrepancy with respect to the more specific question whether CLIL teachers had an adequate repertoire of methods to address these abilities; the teachers’ own perception was much more positive than the students’. Both groups thought that classroom work tended to be student-centred to cater to the diversity of learners. However, there was significant disagreement concerning the application of cooperative learning principles: While the teachers were convinced that their classroom activities followed these principles, student agreement on this item was significantly lower. A similar pattern emerged regarding the use of mixed-ability grouping, individual attention to students as well as peer mentoring and assistance strategies to cater to different abilities. Both stakeholder groups disagreed that classroom layouts were varied to meet the needs of different learners in CLIL. However, it is striking that students’ disagreement was much stronger than that of the teachers.

Figure 3. Stakeholder perceptions of diversity-sensitive methodology and groupings (1 = strongly disagree; bars represent 95% CI).

The qualitative lesson-related data shed light on how methodology and groupings are considered in the teacher’s planning decisions and to what extent students became aware of these decisions through the lesson; the latter would be an important prerequisite for accurate student estimates. It emerged that the extent to which students feel that their abilities are sufficiently considered in CLIL depends more on perceptions of the teacher and their behaviour rather than on methodology. Over the course of the observed lesson, the teacher attended to different learner needs. Following a task-based approach, the teacher in the pre-task phase raised awareness for challenges related to population growth in India and involved the students in planning the task. The cooperative activity followed the think-pair-share principle and began with a phase in which students worked on their own, familiarising themselves with the materials before discussing them with their partner and jointly preparing a report for the class. The teacher used this phase to individually support students struggling with the task, thereby attending to different abilities among learners.

In the interview, the teacher stated that she frequently used pair and group work together with cooperative methods, such as expert groups and partner jigsaws, which use information gaps and/or require communication for the solution of a common problem. The teacher preferred pair or group work to individual work to foster her students’ cooperation skills and to create synergies through peer-mentoring. The teacher generally favoured learner-centred techniques and methods that allow students to support each other and learn at their own pace (e.g. bus stop), thereby freeing up time for the teacher to provide individual support. She also believed that project-based learning gave learners an opportunity to develop autonomy and self-regulation competences because the students work together to solve complex tasks. For example, the teacher had the students regularly conduct small research projects and create posters or Padlet pages summarising the core content while making creative decisions on how to best communicate the information. The teacher was convinced that this fostered deeper learning and critical thinking in CLIL lessons, for instance, by having students construct their own city structure models.

The students referred to their geography teacher as a positive example of how teachers can effectively aid students of different levels of English and subject-specific achievement. The teacher was said to offer sufficient individual support to those who need or request it. The group estimated that around 30% of a lesson was teacher-centred, while 30-40% of the time was usually spent on individual work and another 30% on group work. Although they considered group activities to be mostly fun and engaging (depending on the topic), they doubted that the bulk of students used their time efficiently. They estimated that about 60% of the time available to complete a task in groups was spent on private conversations. One student noted that they found it very helpful to compare their own results to those of a partner before discussing them in the plenum. The lesson observers had the impression that the students did not generally prefer group work or project-based learning to individual work or teacher-centred activities. Students’ responses to the questions in this section implied that the success of their learning depended less on the teaching methods themselves, but more on the perceived attention and support they received from their teacher.

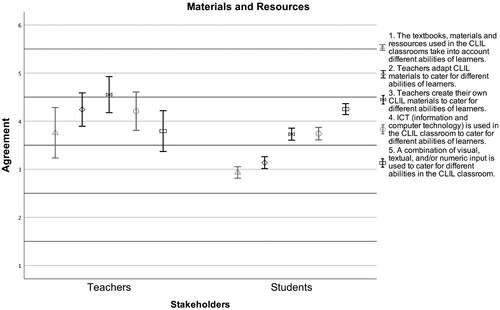

(C) Materials and resources

The views of teachers and students diverged significantly on most items of this subset (). While teachers tended to agree that available textbooks, materials and resources already take into account different levels of abilities, they also confirmed that they needed to adapt these materials or even create their own to meet their students’ needs. In contrast, students were less satisfied with the available materials and were obviously not fully aware of materials adapted or created by their teachers. Along the same vein, the teachers’ estimate of the use of information and computer technology (ICT) to support mixed-ability students was more optimistic than that of the students. An exception to this pattern was found in the perception of the use of multimodal input. Here, the students’ agreement was higher than the teachers’.

Figure 4. Stakeholder perceptions of diversity-sensitive materials and resources (1 = strongly disagree; bars represent 95% CI).

With regard to the materials used in the observed geography lesson, it became evident that resources were limited: Handouts could only be provided as black and white copies and the students were not equipped with personal digital devices. To provide multimodal and multicoloured input (albeit limited to the visual mode), a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation was displayed throughout the lesson. It was also used for process scaffolding by showing an advanced organiser, tasks, scaffolds, and time limits. Some degree of differentiation according to quantity on the task level was observable as there were extra tasks for early finishers. The task structure was based on Bloom’s taxonomy, using cognitive discourse functions (describe, explain, discuss) to indicate different levels of cognitive demand.

When assessing the teaching materials and resources for their CLIL lessons, the teacher placed a strong emphasis on multimodality to facilitate understanding both on the content and language level. They reported that they often adapted or designed their own materials to maintain a consistent layout, frequently combining texts from German geography textbooks and authentic sources (e.g. from the BBC) to provide recent data on a topic. In addition to task sheets, they prepare skills pages for lessons focused on methodological competences and subject-specific literacy. For example, in the observed lesson the teacher introduced the age and gender diagram along with differentiated goals and purposes for the verbalisation of data, modes and styles of communication, and corresponding academic genres, tapping into ideas of pluriliteracies (e.g. Meyer et al. Citation2015). From the perspective of multiliteracies pedagogy (Kalantzis et al. Citation2016), the students also engaged in different modes of presentation (visual, audio, textual, etc.), thus activating a variety of senses in the learning process.

In the focus group interviews, the students expressed their dissatisfaction with the available materials and resources. Due to a lack of CLIL textbooks, they said they worked primarily with handouts. The students were aware that some teachers created these handouts themselves. They acknowledged that there was a digital projector available in the geography room of which the teacher made frequent use. In general, due to the lack of technical equipment, ICT was not used very often in the CLIL classes at that school. The students noted that while materials contain a certain degree of language and content support such as vocabulary lists, they all agreed that the most helpful support is provided by the teacher themselves and stated that whether or not they understood a topic depended on their teacher to a great extent.

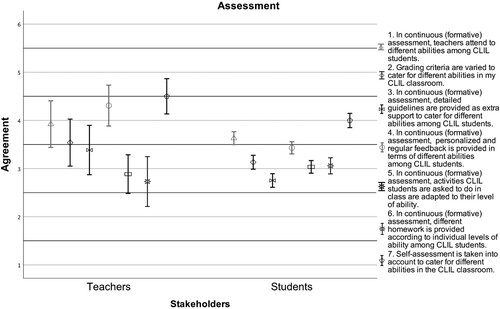

(D) Assessment

Apart from short optional tests or flexible forms such as presentations, assessment in CLIL is predominantly formative and final grades on school reports are based on (teacher testimonials of) in-class performance throughout the lower and intermediate levels of secondary education in Germany. Since the large majority of student participants was on an intermediate level, items focusing on (written) summative assessment were excluded from the analyses.

The survey revealed that teachers consider mixed abilities only to a limited degree when it comes to formative assessment and the rating of in-class performance (). The teachers’ responses on whether they adapt or vary assessment criteria and offered detailed guidelines to support students of different abilities were ambivalent, while the students tended to disagree. The students also witnessed the use of personalised and regular feedback to support students individually less frequently than the teachers. Both groups tended to disagree that different homework was assigned according to individual abilities. This result might have been impacted by the fact that no homework may be assigned at all-day schools on the lower and intermediate levels of secondary school. Finally, both groups agreed that self-assessment is used in the CLIL classroom. However, students saw this less frequently than teachers.

Figure 5. Stakeholder perceptions of diversity-sensitive assessment (1 = strongly disagree; bars represent 95% CI).

Although no specific form of assessment took place in the sample lesson, it was discussed in the interviews. The teacher said that, with the exception of short tests, assessment was largely formative and based on students’ participation during the lessons. This included their contribution to discussions and commitment to individual, pair, and group work as well as the oral and written learning products they created.

The teacher underlined that they considered students’ different needs, learning prerequisites and abilities when assessing their performance. The teacher addressed the reluctance of some students to speak up in class by offering them ample opportunities to hand in written assignments. However, the teacher stressed that they also encouraged all students to practice speaking in the foreign language, for developing communicative competence in English is an important goal of CLIL. When assessing students’ participation, the teacher explained that they pay attention to cognitive demand and depth of processing by giving more weight to higher-order than to lower order-thinking skills. The students’ communicative performance was considered in assessment, albeit with a lower weight than content (which is congruent with official assessment guidelines that explicitly mention a primacy of content in assessment; MSW Citation2012). In addition to teacher-centred assessment, they stated that they used self-assessment checklists at lower secondary level. The teacher was optimistic that through regular formative feedback and scaffolded learning, the students would gradually become more autonomous and self-regulated in dealing with unfamiliar materials and thus be prepared for the requirements of upper secondary CLIL.

According to the students, the assessment criteria were usually laid out by the teacher in the first lesson of a school year. However, the degree of transparency depended on the teacher and adherence to these criteria varied. Some students raised the suspicion that their former teacher ‘used a dice’ to determine their grades as many felt they had been treated unfairly. Their current teacher, in contrast, was perceived to grade them more fairly and transparently, as the teacher readily informed them of their current grades and offered advice on how to improve them.

6. Discussion

6.1. Core findings and perspectives for further research

On the basis of a multi-perspective mixed-method study, this article sought to explore the question: What are (the two main stakeholders’, i.e. teachers’ and students’, perceptions of) current measures taken to create diversity-sensitive, differentiated learning environments in CLIL lessons? While the quantitative survey allowed for a general overview and identified general trends and differences in the perceptions of the two main stakeholders, the qualitative data offered a second, more in-depth angle on the actual implementation of a diversity-sensitive approach to CLIL. In the following, the results of the survey will be critically discussed in the light of the classroom study and major conclusions will be highlighted.

With regard to diversity-sensitive CLIL, four major areas were scrutinised to inform further research and suggestions for improvement with respect to CLIL in practice (see a-d above). Firstly, students’ content and language-related support was the area that was evaluated most positively by both groups. Despite divergent average perceptions on the item on support through content-related strategies, the results showed that differentiation and diverse support seems to be the rule rather than the exception. The finding that students assess teachers’ subject-specific competence more positively than their communicative competence might not always be fully accurate, but it may point to the challenges teachers experience due to the fact they did not usually study the content subject in English and are (subject-specific literacy) learners themselves. On the one hand, this is an advantage for this facilitates a change of perspectives and sympathy for learners, yet, on the other hand, this might affect teaching quality and effectiveness, which is generally related to teacher expertise. The findings also brought forth the monolingual habitus that some teachers seem to transfer to CLIL from the English class or the use of German as a lifeline rather than in order to systematically foster subject-specific literacy in two languages as demanded by CLIL recommendations.

Secondly, concerning methodology and groupings, both students and teachers perceive CLIL classes as student- rather than teacher-centred as well as task- and/or project-oriented and inclusive with regard to different abilities, which is a good basis for effective and diversity-sensitive CLIL. While teachers are also somewhat positive with respect to the remaining items apart from the one on variability of classroom layouts, students are often less positive, in particular with respect to teachers’ adequate repertoire of methods/techniques to cater to different abilities, the use of mixed-ability groupings and peer mentoring, the application of cooperative principles, and personalised attention. Since some of their perceptions widely diverged from those of their teachers, more research on the reasons for this disagreement is needed. Evidently, the students did not feel sufficiently supported in classroom activities. On the one hand, this might indicate that the potential of using different support strategies has not been fully exploited so far. On the other hand, the insights from the interviews also underlined that teacher behaviour and their relationship to their students play a significant role – not only as a direct influence, but also as an indirect one in the form of a positive or negative catalyst of student perceptions. While further (classroom) research is needed to better understand both divergent perceptions and how methodology and groupings can be used to effectively support students of different abilities in CLIL, the case study also demonstrated in an exemplary way how peer and teacher support could be embedded in a task-based learning environment.

Thirdly, a lack of materials and resources which take into account different abilities was lamented by both stakeholder groups. This is a problem that is aggravated by both the insufficient ICT (information and computer technology) resources at many schools in NRW and the limited selection of adequate CLIL textbooks. Even though the major publishing houses offer textbooks for nearly all CLIL subjects, often in separate editions for CLIL streams and modularised CLIL programmes, they are generally of limited use. They mostly constitute adaptations from the corresponding monolingual textbooks, translated into the respective target language and supplemented by tasks and exercises on terminology and discourse functions. However, as confirmed by the survey, they do not pay enough attention to different abilities of learners. Moreover, unlike their monolingual counterparts, many CLIL textbooks are not specifically designed to meet the demands of the individual curricula of the 16 German states, but are published in a unified edition with limited conformity to the guidelines. In practice, the survey revealed that this leads teachers to either adapt available materials or devote a significant amount of time and energy to create their own to adequately support their students. Teacher cooperation also plays a vital role in this respect. To cater to different abilities in CLIL, high-quality materials which offer various levels of differentiation with regard to both content and language need to be made available. In this context, the limited availability of ICT resources, particularly with regard to digital devices and media, constitutes a major obstacle. Such technologies are a major requirement to foster twenty-first century skills and multiliteracies via multimodal input. However, this apparent lack of appropriate materials might as well be regarded as an opportunity to critically reflect the use of traditional (printed) materials in a more inclusive, diversity-sensitive learning environment dedicated to fostering twenty-first century skills. From this perspective, learners are understood as designers rather than mere consumers of learning materials, i.e. they extract information from various (authentic) resources to produce their own, usually multimodal texts that reflect their learning process.

A fourth point of departure for further research are the findings on assessment, which is obviously more resistant to change than teaching. There seems to be ample room for improvement with regards to diversity-sensitive assessment, which generally received the lowest ratings from teachers and students. Only self-assessment seems to be implemented somewhat more regularly. Therefore, further research could focus on how continuous in-class assessment can be used to support students of different abilities in CLIL. Transparency and the dual focus on content and foreign language learning, which requires a more differentiated approach to formative assessment than in monolingual content subjects, deserves particular attention in this respect. The teacher in the case study provided an example of good practice by applying differentiated assessment criteria to cater to different types of students, focusing either on participation in class discussions or learning effort and written work. Such an approach could be followed in creating evaluation schemes for formative assessment that include content-related as well as language-related rubrics. The weight of these rubrics could be flexibly adjusted to the learners’ abilities. Another instrument for formative assessment that has been proven to support learning in foreign language contexts (Bellingrodt Citation2011; Ballweg Citation2017) are portfolios, which allow for teacher as well as self-assessment and encourage learners to take ownership of their learning.

6.2. Limitations

This study focused on stakeholder perceptions of current classroom practice. This approach provides a limited perspective on the subject matter, since these perceptions gathered in the survey are subjective and will most likely not even be identical among students of the same class. Responses to some items may be confounded with, e.g. sympathy for a teacher or be distorted by effects of social or professional desirability on the part of the teacher. It can also be called into question whether students can reliably and validly supply the information about CLIL teaching that was asked of them as they are no trained teaching experts and have limited knowledge of and awareness for the mechanics and processes of teaching – this is even highly challenging for teachers and subject to distorted perceptions. Yet, at the same time, students’ similar tendencies and patterns comparable to those of teachers are indicative of differentiated perspectives and perceptions, i.e. their valuable contributions to the results in the present study.

In addition, the sample was limited to only fourteen schools in North Rhine-Westphalia, which is problematic in view of the fact that CLIL research has frequently pointed to the heterogeneity of CLIL practice (Nikula, Dalton-Puffer, and García Citation2013), not only between but also within countries and states. This implies that fourteen schools were not sufficient to capture current CLIL practice in all its forms, but the survey could only provide a broad general impression.

To ensure comparability and at the expense of content specificity, the cross-national nature of the study also imposed constraints on the formulation of items and the inclusion of further, more context-specific ones.

The aforementioned limitations apply also to the qualitative data, which are subject to further restrictions. The basis of just one lesson and interviews with one teacher and a group of six students is very small. It still enriched the survey by shedding light on contradictory aspects or those hard or impossible to consider in a questionnaire. For example, it uncovered in greater detail the methods, teaching/learning strategies and scaffolding techniques that the teacher used to meet the needs of their students, thereby drawing attention to inspiring examples of good practice and revealed some practical limitations to differentiated learning in diverse classrooms. But due to its size, the classroom study can only offer a restricted view of classroom practice to supplement the survey data. It was planned and would have been desirable to include more classroom observations and interviews to obtain deeper and more reliable insights into actual CLIL practice and perceptions thereof, which was impossible due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

6.3. Prospects

The present study was conducted in the context of the cross-national ADiBE project (Pérez Cañado et al. Citation2019), which includes contributions from Spain, Italy, UK, Finland, Austria and Germany. It has broken new ground in CLIL research, as it is the first international project to investigate the area of diversity-sensitive, mixed ability CLIL teaching. In doing so, it explicitly promotes an agenda of ‘CLIL for all’. The findings of this first phase of the ADiBE project lay the groundwork for further research on heterogeneity in CLIL and will inform the development and improvement of learning materials, teacher training modules and pedagogical video guides.

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge Thomas Janzen and Stephan Gabel’s contribution to conducting the survey and data analysis. We would also like to thank Stewart Campbell for proofreading and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Philipp Siepmann

Dr Philipp Siepmann is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the English Department at the University of Münster, Germany. After completing a teaching degree (M.Ed./first state exam) from Ruhr-University Bochum in 2010, he wrote a doctoral dissertation on transnational cultural studies in the EFL classroom and received his PhD in 2014 from the same university. He then took up pre-service teacher training at the Zentrum für schulpraktische Lehrerausbildung Duisburg, where he obtained a teaching certification (second state exam) in 2015. Between 2010 and 2019, he taught English and CLIL Geography at several secondary schools in North Rhine-Westphalia. He joined the English Language Education team in Münster in 2019, where he is currently working on his postdoctoral research project on oral examinations in the foreign language classroom. His research interests also include CLIL as well as cultural and literary learning.

Dominik Rumlich

Dr Dominik Rumlich is currently full professor of English Language Education (ELE) at the University of Paderborn, Germany. In 2009, he completed a teaching degree (first state exam) in English and geography at the University of Duisburg-Essen, where he also received a PhD on the basis of a quantitative, two-year longitudinal CLIL study with 1,400 participants six years later. Afterwards, he was junior/associate professor of ELE at the University of Münster and, for a year in between, held a position as interim chair of psycholinguistics, second language acquisition (including ELE) at the University of Wuppertal. He also worked as a part-time teacher of English at several secondary schools. His international experience includes, among others, a one-year study-abroad programme at the University of Waikato, New Zealand, and guest lectureships at the Universities of Antwerp, Eastern Finland, and Uppsala, Edge Hill University, and Fort Hays State (KS). His areas of teaching and research include CLIL, assessment, affective-motivational determinants of language learning, learning strategies, and empirical research methods (esp. quantitative). He is currently also involved in research projects on the digitalisation of language learning/teaching, young adult fiction in the language classroom, the transition between primary and secondary school, and teacher education.

Frauke Matz

Dr Frauke Matz is chair of English Language Education (ELE) at the University of Münster, Germany. She studied English and History at the University of Essen, Germany, where she completed her 1st state exam in 2000 and received her PhD in 2006. She continued her studies at the University of Wolverhampton, England, where she completed her Masters of Arts in English Studies as well as the TESOL Trinity College Certificate. She received her Graduate teacher status from CILT London in cooperation with the University of Birmingham in 2006 and her Fully Qualified Teacher Status in 2007. Before working as a lecturer at the University of Duisburg-Essen she worked as a teacher for English and History (CLIL) at a secondary school in Düsseldorf. Prior to becoming a full professor at the University of Münster, she held a position as interim chair of English Language Education both at the University of Gießen (2016) and Münster (2017–18). Her areas of research include cultural learning and cosmopolitan approaches to English language education, muliliteracies, aspects of inclusion as well as alternative forms of assessment.

Ricardo Römhild

Ricardo Römhild is a research assistant and lecturer at the English Department at the University of Münster, where he is part of the English Language Education team. In 2015, he completed his studies of English, Geography, and Educational Studies at Friedrich Schiller University Jena. He then worked as a Fulbright German Teaching Assistant at Lycoming College in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, USA, before earning his teaching certification at Studienseminar Koblenz. He joined the English Language Education team at WWU Münster in October 2018 and has since been working on his PhD. His research interests include cultural learning and global education, education for sustainable development, as well as media and (documentary) film didactics.

Notes

1 For a more comprehensive discussion of the notion of diversity underlying the ADiBE project, see Pérez-Cañado’s introduction to this volume.

References

- Abendroth-Timmer, D. 2009. “Zur sprachenpolitischen Bedeutung und motivationalen Wirkung des Einsatzes von bilingualen Modulen in sprachlich heterogenen Lerngruppen.” In Bilingualer Unterricht macht Schule: Beiträge aus der Praxisforschung. 2nd ed., D. Caspari, W. Hallet, A. Wegner, and W. Zydatiß, 177–192. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

- Apsel, C. 2012. “Coping with CLIL: Dropouts from CLIL Streams in Germany.” International CLIL Research Journal 4 (1): 47–56.

- Ballweg, S. 2017. “Lernendenautonomie und Portfolioarbeit? Zum selbstbestimmten Handeln von Studierenden bei der Portfolioarbeit im DaF-Unterricht.” In Inhalt und Vielfalt – Neue Herausforderungen für das Sprachenlernen und -Lehren an Hochschulen, edited by C. Harsch, H. P. Krings, and B. Kühn, 109–120. Bochum: AKS Verlag.

- Baumert, J., and O. Köller. 1998. “Nationale und internationale Schulleistungsstudien: Was können sie leisten, wo sind ihre Grenzen?” Pädagogik 50 (6): 12–18.

- Bellingrodt, L. C. 2011. ePortfolios im Fremdsprachenunterricht. Empirische Studien zur Förderung Autonomen Lernens. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Breidbach, S., and B. Viebrock. 2012. “CLIL in Germany: Results from Recent Research in a Contested Field of Education.” International CLIL Research Journal 4 (1): 5–16.

- Cummins, J. 1979. “Cognitive/Academic Language Proficiency, Linguistic Interdependence, the Optimum Age Question and Some Other Matters.” Working Papers in Bilingualism 19: 121–129.

- Dallinger, S., K. Jonkmann, and J. Hollm. 2018. “Selectivity of Content and Language Integrated Learning Programmes in German Secondary Schools.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (1): 93–104. doi:10.1080/13670050.2015.1130015.

- Denman, J., E. van Schooten, and R. de Graaff. 2018. “Attitudinal Factors and the Intention to Learn English in Pre-Vocational Secondary Bilingual and Mainstream Education.” Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics 7 (2): 203–226. doi:10.1075/dujal.18005.den.

- Diehr, B., and D. Rumlich. 2021. “Zur Einführung in den Themenschwerpunkt.” Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen 50 (1): 3–14. doi:10.2357/FLuL-2021-0001.

- Fortune, T. W. 2011. “Struggling Learners and the Language Immersion Classroom.” In Immersion Education: Practices, Policies, Possibilities, edited by D. J. Tedick, D. Christian, and T. W. Fortune, 251–270. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Frisch, S. 2021. “Bilinguales Lernen in der Grundschule: Einblicke in sprachliche und naturwissenschaftliche Kompetenzen.” Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen 50 (1): 31–49.

- Genesee, F. 2007. “French Immersion and at-Risk Students: A Review of Research Evidence.” The Canadian Modern Language Review 63 (5): 654–687.

- Glaap, A.-R. 2001. Schulversuch bilingualer Unterricht an Realschulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Abschlussbericht. Accessed 6 March 2021. https://www.schulministerium.nrw.de/sites/default/files/documents/BerichtRL.pdf.

- Kalantzis, M., B. Cope, E. Chan, and L. Dalley-Trim. 2016. Literacies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- KMK (Kultusministerkonferenz). 2013. Konzepte für den bilingualen Unterricht – Erfahrungsbericht und Vorschläge zur Weiterentwicklung. Accessed 17 October 2013. https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2013/201_10_17-Konzepte-bilingualer-Unterricht.pdf.

- Küppers, A., and M. Trautmann. 2013. “It Is Not CLIL That is a Success – CLIL Students Are! Some Critical Remarks on the Current CLIL Boom.” In Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Europe: Research Perspectives on Policy and Practice, edited by S. Breidbach and B. Viebrock, 285–296. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

- Leisen, J. 2010. Handbuch Sprachförderung im Fach – Sprachsensibler Fachunterricht in der Praxis. Bonn: Varus.

- Mentz, O. 2008. “Bilingualer Unterricht für alle?” Der Bilinguale Unterricht 1: 6–9. Accessed 6 March 2021. https://www.klett.de/sixcms/media.php/321/KTD_44_s3-4.pdf.

- Meyer, O., D. Coyle, A. Halbach, K. Schuck, and T. Ting. 2015. “A Pluriliteracies Approach to Content and Language Integrated Learning – Mapping Learner Progressions in Knowledge Construction and Meaning-Making.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 28 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1080/07908318.2014.1000924.

- MSB (Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen). 2021a. CertiLingua. Online. Accessed 6 March 2021. https://www.certilingua.net.

- MSB (Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen). 2021b. Bilingualer Unterricht in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Accessed 23 February 2021. https://www.schulministerium.nrw.de/themen/schulsystem/unterricht/lernbereiche-und-unterrichtsfaecher/bilingualer-unterricht-nordrhein.

- MSW (Ministerium für Schule und Weiterbildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen). 2012. Bilingualer Unterricht Erdkunde deutsch-englisch in der Sekundarstufe I. Accessed 6 March 2021. https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/cms/upload/bilingualer_Unterricht/documents/HR_BU_EkE_SekI_0912.pdf.

- Nikula, T., C. Dalton-Puffer, and A. L. García. 2013. “CLIL Classroom Discourse: Research from Europe.” Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 1 (1): 70–100. doi:10.1075/jicb.1.1.04nik.

- Ohlberger, S., and C. Wegner. 2018. “Bilingualer Sachfachunterricht in Deutschland und Europa. Darstellung des Forschungsstands.” HLZ 1 (1): 45–89. Accessed 6 March 2021. https://www.herausforderung-lehrerinnenbildung.de/index.php/hlz/article/view/2390/2386.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2020. “CLIL and Elitism: Myth or Reality?” The Language Learning Journal 48 (1): 4–17. doi:10.1080/09571736.2019.1645872.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L., D. Coyle, T. Ting, T. Nikula, C. Dalton-Puffer, F. Matz, T. Jerez Montoya, et al. 2019. ADiBE Project. CLIL for All: Attention to Diversity in Bilingual Education. Accessed 6 March 2021. https://adibeproject.com/.

- QUA-LIS NRW. 2021. Was ist sprachsensibler Fachunterricht? Accessed 6 March 2021. https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/cms/sprachsensibler-fachunterricht/sprachsensiblerfachunterricht/sprachsensibler-fachunterricht.html.

- Rumlich, D. 2016. Evaluating Bilingual Education in Germany: CLIL Students’ General English Proficiency, EFL Concept and Interest. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

- Rumlich, D. 2020. “Bilingual Education in Monolingual Contexts: a Comparative Perspective.” The Language Learning Journal 48 (2): 115–119. doi:10.1080/09571736.2019.1696879.

- Schrandt, C. 2003. “Evaluierung des bilingualen Unterrichts an Berliner Realschulen: Leistungsmessungen in der Zielsprache Englisch.” PhD diss., Freie Universität Berlin [Mircofiche].

- Schwab, G. 2013. “Bili für alle? Ergebnisse und Perspektiven aus einem Forchungsprojekt zur Einführung bilingualer Module an einer Hauptschule.” In Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Europe: Research Perspectives on Policy and Practice, edited by S. Breidbach and B. Viebrock, 297–314. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

- Schwab, G., J.-U. Keßler, and J. Hollm. 2014. “CLIL goes Hauptschule – Chancen und Herausforderungen bilingualen Unterrichts an einer Hauptschule. Zentrale Ergebnisse einer Longitudinalstudie.” Zeitschrift Für Fremdsprachenforschung 25 (4): 3–37.

- Vollmer, H. J. 2010. “Förderung des Spracherwerbs im bilingualen Sachfachunterricht.” In Bilingualer Unterricht: Grundlagen, Methoden, Praxis, Perspektiven. 5th ed., edited by G. Bach and S. Niemeier, 131–150. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

- Wode, H. 1995. Lernen in der Fremdsprache: Grundzüge von Immersion und bilingualem Unterricht. Ismaning: Hueber.