ABSTRACT

This ADiBE case study explores an innovative, integrated approach to addressing diversity in secondary classrooms in England, where more than one language is used and learned. We position diversity in multilingual and multicultural communities where schooling seeks to provide meaningful learning experiences for all students and guide learners towards being and becoming global citizens. Within a UK context, underpinning values emphasise social justice and inclusion embodied in classroom practices that actively involve teachers as researchers with their learners – in terms of ‘curriculum-making’ and reinterpreting the impact of diversity on ‘successful’ learning communities. This research analyses contextual and exploratory factors that enable diverse learners with diverse needs to engage in learning partnerships with each other and their teachers. Using a framework to capture collaborative professional learning, synergies are explored between two different approaches to bilingual learning – English as an Additional language (EAL) and Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). The case study identifies potentially rich sites for building pedagogic capital and explores how diversity can enable more young people to feel valued, respected and successful bilingual learners in formal schooling.

1. The context

As our educational landscape is undergoing unprecedented changes, displacement, migration and global movement of peoples are presenting teachers with challenges and opportunities as rapidly shifting demographics require educators to reconceptualise values-driven curriculum and classroom practices to meet the needs of diverse learners. Described by Vertovec (Citation2007) as ‘superdiversity’, schools across the UK are increasingly educating students from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds who need to learn English as an Additional Language (EAL). Over 1,620,000 EAL students in maintained schools in England speak, or engage with, languages other than English (LOTE) at home (DfE Citation2020). In contrast, however, the learning of other modern foreign languages (MFL), such as Spanish or French, in UK schools is in severe decline – that is, except for heritage languages such as in Welsh or Gaelic-medium schools. The UK continues to lag behind other European countries in terms of linguistic capital. Only 32% of young people feel confident reading and writing in another language, compared to the rest of the EU’s 89%. These data emphasise that students rarely have bilingual experiences in schools – such as Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) – compared to their counterparts throughout Europe. Moreover, the situation differs significantly across the UK’s four jurisdictions. It could be argued, for example, that the impact of policies in England ‘hinders’ mainstream language learning. This linguistic conundrum is fundamental to situating this study in England, where a potential multicultural, multilingual richness is being played out in many classrooms as students speak languages other than English at home or in their local community, compared to the paucity of opportunities for ‘mainstream’ monolingual students to engage in bilingual education, fundamental for broadening concepts and deepening values for global citizenship. The need to support teachers in developing pedagogic approaches that not only promote ‘learning how to live with difference and learning how to learn through difference’ (Messiou and Ainscow Citation2020, 671), but also create opportunities for mainstream modern language learning leads to periods of turbulence in relation to ways of thinking and working (Ainscow et al. Citation2006), which fuel pedagogic dilemmas.

However, grasping the ‘pedagogic’ nettle, this research study explored how diversity might be a stimulus for fostering ‘successful’ learning in a multilingual, multicultural school community in an area of social and economic deprivation in England. Seeking to explore the notion of teachers as ‘designers of learning’, this study is built on the premise that pedagogy lies in the space between broad principles, specific teaching methods and classroom practices. According to Paniagua and Istance (Citation2018, 27):

combining approaches means moving beyond the fragmented focus on specific pedagogical innovations to highlight the importance of the creative work of teachers and schools when adjusting, adapting, mixing and updating the clusters of innovative pedagogies.

Our research is located in a state secondary school in England promoting professional learning, which builds on teachers’ contextual knowledge (Feldman and Herman Citation2015) and cultural knowledge (Gay Citation2018). Articulating these ‘knowledges’ involved addressing a significant shift from top-down policy prerogatives to bottom-up teacher-led, sustainable pedagogic evolution. That is the contextual conditions needed to promote and transform CLIL and EAL values-driven combined pedagogies into practice, underpinned by teachers’ knowledges and responsiveness to diverse student needs, are brought into focus. Whilst it could be argued that all classrooms are diverse, here we use the term to indicate multilingual, multicultural dynamic learning communities. Moreover, given the challenging socio-economic status of the case study school community, where over forty-two languages are spoken, the locus for combining EAL, CLIL and MFL approaches, provides a fertile ground for understanding the necessary conditions for embracing bilingual learning. In this context, bilingual learning includes EAL and LOTE (Spanish and French). Since secondary schooling prioritises the study of subject disciplines, our conceptual framework detailed in 2.0, positions subject and language teachers in one professional learning community together, fostering change and building ‘pedagogical capital’ (Cuban Citation2013).

2. Exploring pedagogic ‘seeds for change’

Whilst Pagiagua and Istance (2018, 15) believe that innovation in teaching is a ‘problem-solving process rooted in teachers’ professionalism and a normal response to addressing the daily changes of constantly changing classrooms’, they acknowledge that pedagogy is a complex business. They urge a move to explore in-depth the processes involved in combining pedagogic approaches to unravel ‘potential seeds for change’.

Across all parts of the UK, educational policies promote equality and inclusion, stating that all students should have equal access to the mainstream curriculum (Harris and Leung Citation2011). Whilst this policy has led to some successful instances of ‘mainstreaming’ EAL learners across the UK and other anglophone countries, more generally, mainstreaming has been instrumental in positioning EAL students as similar to fluent monolingual English-speaking students except for linguistic competence (de Jong and Harper Citation2005; Leung Citation2012). This has resulted in undifferentiated mainstream classrooms (Costley and Leung Citation2009, 152) that provide some form of access to an English, monolingual/monocultural curriculum, but where expectations are mainly to conform to westernised literacy outcomes.

A growing body of literature foregrounds supportive EAL mainstream environments emphasising the importance of critical pedagogic moves such as classroom talk, multimodal resources, the use of home languages and translanguaging pedagogies, and an awareness of cultural diversity and pluriliteracies. These studies, however, have led to limited changes in everyday classroom practices, suggesting that insufficient preparation for mainstream teachers working in culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms (Conteh Citation2012; Foley et al. Citation2018) raises pedagogic concern. There is an urgency to critically challenge the notion of diversity as a political ideal that may recognise difference yet characterises it as neutral (Reeves Citation2004).

The value position adopted by more recent research (Foley et al. Citation2018) focuses on transforming monolingual, English-only mainstream environments into those built on principles of social justice, equity and inclusion, where the powerful engines of mainstreaming and inclusion can be used to drive a critique of dominant languages, literacies, cultures and power structures that shape teaching and learning. Expanding teachers’ pedagogic repertoires to those that foster linguistic and culturally responsive approaches moving away from ‘assimilate or fail’ ideologies, positions diversity at the core of classroom practices (Foley et al. Citation2018). These observations support Leung’s (Citation2005, 95) claim that

diverse interpretations and practices of EAL within the teaching profession signal a lack of clear and coherent understanding of EAL pedagogy. None of this would matter if EAL students were performing on par with other students. But there are signs of long-term underperformance.

Pérez-Cañado (Citation2020, 2) notes the ‘craze, critique, conundrum, and controversy’ which CLIL research engenders, raising well-documented contentious issues, such as ‘elitism’ and exclusion; the paucity of robust research; the lack of clarity about its definition, purposes and goals; the benefits of CLIL programmes; teacher training and so on. Such critical debates are welcome and serve academic and professional communities well (e.g. Cenoz, Genesee, and Gorter Citation2014; Dalton-Puffer et al. Citation2014; Bruton Citation2015; Van Mensel et al. Citation2020). What is clear, however, is that there is no one pedagogic approach that can be described as the CLIL approach. The complexity of bilingual education and the conditions in which it flourishes is appropriately likened by Garcia to the banyan tree ‘allowing for growth in different directions at the same time and grounded in the diverse social realities from which it merges’ (Citation2009, 17).

In his article What does the research on Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) tell us about EAL? Morton (Citation2018, 57) refers to a ‘timely’ pedagogic trend that demonstrates ‘a convergence of goals’ by adding ‘a focus on subject-literacy to that on content and language.’ Whilst it could be argued that EAL practices have increasingly embraced academic literacies (Gibbons Citation2018) and critical literacies (Janks Citation2010), the CLIL agenda has only recently moved towards pluriliteracies (Meyer et al. Citation2015), foregrounding the development of literacy skills across languages and subject disciplines. Similarly, Halbach’s (Citation2020) literacies’ approach to language learning resonates with ‘a view of language, and tools for teaching, to help move beyond structure-based views of language’ (Dale Citation2020). What has become clear as EAL and CLIL pathways move closer together is that sharing context-responsive pedagogic understanding provides ‘a way of bringing together a range of pedagogical or methodological principles and perspectives’ (Morton Citation2018, 57).

Given the exponential uptake of CLIL on a global scale offering ‘enriched curricular options’, provision is predictably inconsistent. Yet in England, limited support by successive governments, the absence of comprehensive national policies to address the low status of languages, alongside the paucity of linguistic competence amongst subject teachers in LOTE, has meant that despite constant innovative, pioneering work by teachers, educators and researchers, conditions for developing CLIL are limited. They are significantly different in the UK than in mainland Europe. As Dobson (Citation2020, 508) emphasises – ‘context is everything’.

Therefore, given the ‘unforgiving complexity of teaching’ (Cochran-Smith Citation2003, 4), building a shared and realistic understanding of tasks and activities, their underlying values, purposes and outcomes as practiced responsive pedagogies, provides a fundamental ‘point de départ’ for the ‘seed for change’.

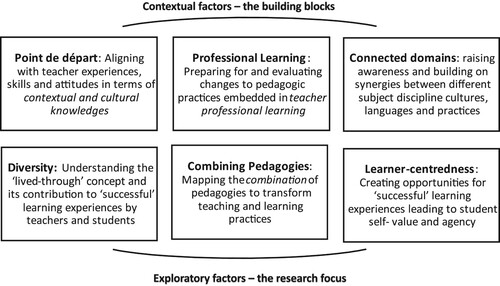

3. The conceptual framework – teachers as designers

Since teachers’ practice-based understanding is embedded in their own subject disciplinary and cultural identities, attitudes and experiences, which may conflict with alternative theoretical principles and their enactment in the classroom, there was a need to work with the complexity of how connections, relations, interactions and processes of individuals interact in and across the classrooms:

between the creator and their concerns, emotions, people, ideas and other resources, places and spaces and their practices as they are lived and experienced in the unfolding processes and activities. (Barnett and Jackson Citation2020)

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for teachers as designers (adapted from Paniagua and Istance Citation2018).

The framework starts with contextual factors to situate pedagogic developments in a given school community, including its socio-economic circumstances and position in national performance league tables. Factors, such as these, crucially build on teacher contextual and cultural knowledge to explore shared context-embedded professional learning. The point de départ explores current teacher thinking in terms of agreed school improvement goals. Connected domains require teachers from different subject disciplines to work together to analyse thinking, share new ideas and build a repertoire to achieve those common goals. The exploratory factors () identify the focus of the ADiBE professional learning – investigating how diversity might lead to successful learning through combining pedagogies (in this case, literacies approaches in EAL and CLIL) – putting the learners’ needs and aspirations at the core i.e. learner-centredness. The Conceptual Framework, therefore, guided the investigative processes of this study and led to our research questions. All factors are interconnected, as indicated in the first part of this article.

4. The case study

The school is a large state 11–18 secondary school with socio-economic circumstances significantly below the national average (). 45% of students have safe-guarding records, and approximately 60% are EAL learners compared to the national average of 15.6%. Around 80% of newly arrived migrants (NAM) are not yet competent in English. Forty-two other languages are spoken. Approximately 18% of learners are Gypsy-Roma compared to a national average of 0.3%. Gypsy Roma are the lowest-achieving demographic group in England.

Table 1. Profile of the case study school.

The product of an amalgamation of two ‘failing’ schools in 2011, by 2014, the school was considered ‘inadequate’ after national inspection. A subsequent inspection (2016) judged the school to ‘require improvement.’ In 2017 a new school was relaunched under a different headteacher with clearly stated values drawing together diversity, cultures, literacies and languages. The new senior leadership (SMT) recognised the urgency of developing a relevant curriculum that met the needs of diverse learners embracing literacies across languages. A more integrated literacies approach for multilingual learners was actioned in the School Development Plan, integrating CLIL and EAL principles to create an accelerated curriculum for learners with little or no English to access curriculum content successfully whilst learning English. This provided a ‘safe’ learning space to prepare for the mainstream ‘aspire’ curriculum. The Deputy Headteacher had previously undertaken CLIL professional development and introduced alternative approaches in the new accelerated curriculum, including the PEALit (Prepare for EAL and Literacy) programme focusing on literacy skills. Whilst upskilling, the teachers focused initially on the accelerated curriculum, intending to expand new approaches across all subjects in both the accelerated and aspire curriculums, each accounting for approximately 50% of the cohort, thereby opening the door for CLIL development across subject disciplines. At the time of the study, combined approaches (EAL and CLIL) were being experimented in English and MFL and the accelerated EAL curriculum through History and Geography.

In 2017, the school was designated ‘good,’ with national inspectors noting that the school ‘celebrates the richness of language and culture … Leaders have developed links with schools across … the UK and Europe, making the school a hub of language teaching and learning.’ Ofsted (Citation2020) also acknowledged leaders’ commitment to ensuring access to a broad curriculum in spite of challenges learners face noting that

New students, often speaking little or no English or with specific barriers to learning, follow an accelerated curriculum where they are rapidly equipped to fluently speak, read and write.

4.1 Research design

Case study as a ‘specific, unique, bounded system’ (Stake Citation2005, 445) framed this qualitative longitudinal research using the school as the unit of analysis with nested elements (Thomas Citation2011), including national inspection, the wider school community and individual classroom learning. Following Yin (Citation2009), this study maps a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, involving key players – teachers, school leaders and students (Merriam Citation1998; Stake Citation2005) where the boundaries between phenomena and context are not evident, and in which multiple sources of evidence are used.

Our methodology sought to capture pedagogic developments. The conceptual framework () provided us with a ‘point de depart,’ (cognisant of pedagogic changes over the previous two years) to map ‘professional learning’ (teacher preparedness to share practice) and ‘connectedness’ (practitioners from different disciplines learning from each other) as context-embedded factors. These, in turn, supported a focus on the exploratory factors (diversity, student centredness and combined pedagogies), which guided and informed the research questions as follows:

(RQ1) How do learners and teachers conceptualise diversity within their school?

(RQ2) How do learners and teachers perceive learning in this multilingual context?

(RQ3) In what ways do teacher perceptions of diversity shape combined practices in EAL-CLIL multilingual classrooms?

4.2 Phase 1

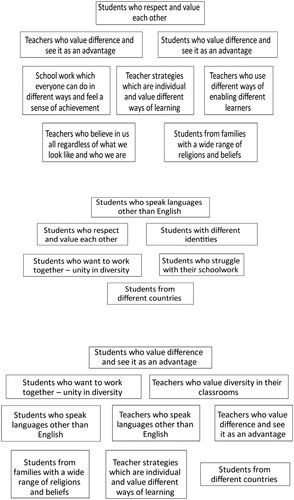

In phase 1, representative students of the age and cultural profile of the school were invited by their teachers to volunteer to form focus groups (see ). In some instances, the focus groups required student interpreters. Fifty-three students participated in sixteen focus group discussions and a prioritisation task. Seven teachers – 3 MFL teachers [LTs] and 4 accelerated curriculum teachers [ACTs] and 2 senior teachers – [HT] and [DHT] agreed to semi-structured interviews (Appendix 1). A purposeful sampling of the teachers included those closely involved with the accelerated curriculum and those interested in connecting key pedagogic principles to the aspire curriculum (EAL, subject teachers and language teachers).

Table 2. Data collection.

The student focus groups and teacher interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using contiguity-based thematic analysis procedures to code and classify data in three interrelated stages (Maxwell Citation2013). The first stage focused on student data to identify themes relating to diversity (RQ1) and learning (RQ2); the second stage analysed the teacher data initially using the student themes and extended these to include new ‘teacher’ themes (RQ3). The final stage combined the second stage data thematic categories with those from the conceptual framework focusing on the a priori themes of diversity, learner-centredness and combined pedagogies () from both student and teacher perspectives (RQ3) (Bryman Citation2004). These data provided a framework for continued development beyond this study.

The student data yielded three key coded themes with sub-themes: the nature of diversity; successful learning (including bilingual learning, classroom organisation, pedagogic approaches, resources and assessment); and ‘lived’ experiences (individual perceptions and evaluations). Sub-themes included identity, feeling valued, belonging, literacies, progression. Two additional themes emerged from the teacher data: professional learning and support; and context-specific issues (such as Ofsted inspection pressures to sustain school improvement). The analysis across all stages was supported by repeated reading and intercoder reliability by the research team drawing on transcripts, coding and analysis stages. The student focus group card-sorting task provided opportunities for rich discussion and photographic evidence as complementary data.

4.3 Phase 2

Phase 2 consisted of two initial researcher-led teacher workshops. Pedagogic approaches were openly discussed, analysing CLIL and EAL principles with increasing attention to literacy skills and subject literacies. A further workshop for accelerated curriculum (EAL) leaders, a group of History and Geography subject leaders as well as accelerated curriculum and Modern Languages teachers engaged in sharing classroom practices and explored how combining pedagogies, underpinned by (subject) literacies and pluriliteracies principles, might enhance learning for all students.

Throughout eight subsequent virtual teacher-initiated workshops, teachers and researchers together explored designing learning for and through diversity. The primary data source consisted of detailed researcher field notes supplemented where possible by audio-recorded data. Two units of study were co-constructed and piloted – slavery (including modern-day slavery) and dark tourism – in English, Spanish and French. Whilst detailed analysis of the workshops and materials produced is beyond the remit of this article, ‘next steps’ along the pedagogic design pathway were used to inform the next iteration of the framework. In line with university and BERA regulations, ethical practices were followed with permissions from all participants, including requisite safeguarding procedures (British Educational Research Council Citation2011).

5. Findings

This section presents the findings in relation to the exploratory factors of the conceptual framework, as indicated by the research questions. The discussion section aligns the exploratory factors with the contextual factors to map out the ‘next steps’.

5.1. RQ1. How do teachers and learners conceptualise diversity within their schools?

Both student and teacher data revealed a broad yet consistent shared understanding of diversity within the school, focussing especially on ethos and valuing languages, cultures and abilities. Teachers were mindful of socioeconomic factors; ‘I've got a child in my tutor group who can't afford shoes’ [LT2].

Students talked about the ‘positive contagion’ (Fullan and Langworthy Citation2014) in the school, which fostered a sense of ‘togetherness’, allowing those from different backgrounds, languages, religions and cultures to feel included and valued. The students across the age range felt a sense of equity; ‘everyone has got different skills, no one can judge them’ [KS3.S1]. Teachers focussed on celebrating different cultures and embedding belonging and diversity into the accelerated curriculum. One student stated ‘the things that make us different is the thing that makes us special’ [KS3.S3]. Several groups pointed to the ‘language of the month,’ used to promote different languages and traditions:

I think that it’s good that other languages and countries get more exposure, because there might be some people from like England or something that don’t know about that … [KS5.S2]

The school message of ‘respect’ was highlighted as a visible ‘living concept’ reflected in the Respect Charter – ‘we might be different by our culture but as people we’re the same and equal’ [KS5.S2]. Students were constantly challenged to consider the value of their own contribution to diversity within their learning environments.

It was also recognised by staff that leadership in the school was vital in promoting messages of respect and attitudes of acceptance. ‘If I go back five years, we were not acknowledging the diversity in this school … it comes down to understanding the young people in the community’ [DHT]. The Head teacher described learning languages through interactions with students and staff to ‘live’ the values in terms of language and culture: ‘Children don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care. So, it’s that nurture. Nurture is fundamental’ [HT].

This attitude was regarded highly by teachers in the school:

Every time [the headteacher] sees me, she says something in Spanish … it means a lot and I think the children can see this … It means respect and tolerance about differences and diversity. Here languages are really valued. [LT1]

5.2 RQ2. How do learners and teachers perceive learning in this multilingual context?

5.2.1 ‘Successful’ learning

Teachers spoke about the importance of inclusion in terms of culturally responsive content relevant to learners’ cultural and social heritage in lessons – for example History themes make visible that ‘we understand a little bit more about them and we want to learn as well from them’. [ACT4]

In most of the schemes of work the Holocaust is predominantly just focussing on the Jewish populations that were killed, but a lot of our students are from Roma backgrounds, and it's underreported a lot about the Roma genocide, so we try and incorporate that to reflect the students that we're teaching. As teachers at this school, it's always at the back of our minds how can we make those links. [ACT2]

We use our local history, all those CLIL topics, wherever we can find a link. They're not just learning about it in the classroom, they're seeing it in their city, and what we're trying to do is make them feel that they belong. [DHT]

It doesn’t matter what their starting point is if we’re getting it right. Otherwise, we’re not pitching our curriculum at the right place - we’re not giving them the right diet, we need to look at what we do [HT].

Every time I do a presentation, I do my top button, I do my tie. And I speak loudly. I show them the activity, ask them questions, give them more information. And I'm really proud that I'm confident and that’s where my anxiety disappears. [KS3.S2]

When you look back at your progress from just saying simple words and then seeing now you can like pull off whole sentences. You can hold like a normal intelligent conversation. It makes you appreciate how far you’ve come. [KS5.S1]

5.2.2 Lived experiences

Independent learning was emphasised by teachers. Creative tasks were prioritised, giving students ‘the freedom to talk about what is interesting for them, but in a different language.’ For example, students created their own songs and poems in Spanish, described by several teachers as ‘inspiring’.

We have creative projects where students make their own songs, they learn about rhythm and rhyme. That's really very, very cognitively high load but we've specifically chosen them because of the storytelling and actually makes it accessible to the students. [DHT]

Placing the learner at the centre was key to the school ethos. Complacency was not an issue as staff were constantly encouraged to dig deeper to diversify learning and teaching practices. It was the ‘point de depart’ for the teacher-led design workshops. ‘It was just being brave enough to do something different and nobody else was coming up with any solutions for us’ [HT]. There was recognition of the importance of leadership: ‘it’s about empowerment, leadership at every single level and I think that I’ve always been really clear about this. Our middle leaders are the key to this place’ [DHT].

Student data corroborated the accessibility and motivational elements of their learning experiences, reflected in ‘learner-centredness’. The range of topics – such as past and future technologies, famous historical figures and different cultures – went alongside language learning. One student accessed different insights ‘giving you like this different feeling – we are going inside the culture’ [KS5.S3].

5.3 RQ3 In what ways do teacher perceptions of diversity shape combined practices in EAL-CLIL multilingual classrooms?

A shared understanding of serving the community and the constant search for effective ways of building on diversity in the classroom was evidenced through on-going professional dialogue. Given the challenging contextual issues, professional dialogue between teachers and researchers during the workshops in Phases 1 and 2 laid the foundations for mapping suggestions for a shared transformative learning trajectory, for ‘digging deeper’ into combining classroom practices and creating shared spaces for working together – having the confidence to acknowledge uncertainty and understand that pedagogic change takes time. In particular, working with teachers of Language(s), Geography and History tackled fundamental questions concerning the epistemic nature of subject disciplines and the languages and skills needed to enable young people to become more independent, responsible learners.

5.3.1 Affordances of professional learning

Professional learning was seen as fundamental to sustaining the school’s development. Teachers described a collaborative exploration of (re)designing learning through

a pedagogic space … aware of the way domains organise their teaching designs and how these domains can be better connected and combined to make innovations more effective. [ACTeacher4]

I'm a PEALit coach. I'm paired with somebody else in the school … . and that gives you an opportunity to hear what they're doing in other subjects. We pick apart lessons and think how can we make that even more EAL friendly. If you are somebody who has come to the country and you have no English, how you could access? [ACT1]

5.3.2 Contextual issues and future goals

The teacher and school leader interviews provided insights into the extensive challenges of transforming a ‘failing school’. The impact of ‘labels’ and the constant pressure to improve cut deep. Contextual issues embedded in the complexity of such a socio-linguistic and multicultural diverse community were constant. Behavioural issues were understood in offering a relevant and accessible experience – ‘I think number one – understand your context and really understand it’ [ACT]. The urgency to bring about change led the SMT to readdress contextual demands and find alternatives – the impetus leading to the development of an accelerated curriculum (EAL):

I felt very strongly that we were giving our teachers an impossible task … We've got large groups of children who speak the same or similar languages and so it's not possible to immerse, so that wasn't working. We got to the point where we just said we need to do something different. [HT]

Teachers accepted that such challenges bring both failures and enlightenment, and that there are no panaceas. All young adolescents need understanding: ‘We focus on behaviour. Not behaviours as in bad behaviour but behaviours for learning’ [DHT]. They viewed PEALit as an exciting opportunity to share and learn with other staff members across the school and ‘become more content teachers and have more knowledge of the curriculums.’ [ACT 1] The sharing of approaches between subject disciplines and curricular areas had fostered, in the head teachers’ view, ‘an open, transparent culture’:

It’s not about you create something, you keep it to yourself. It’s not about competitiveness. It’s about how we support one another and I think that’s embedded in everything we do. [HT]

However, there was also a sense that much more work needed to be done; ‘constantly evolving and as we develop, we look very strategically at each of the subjects … . it’s just the CLIL pedagogy. It’s how do we teach somebody a subject in a language that they don’t have much command of’ [DHT].

In thinking how PEALit based on EAL-CLIL principles enacted in EAL settings (accelerated curriculum) could be spread out across the school and across disciplines (aspire curriculum), so that all staff could benefit, the head teacher recognised that the school ‘was not quite there yet,’ but that the potential was there to transform teaching and learning:

That [PEALit] will be the thing that will move us to the next level because if we can get high quality teaching and learning in every classroom, we’re going to have children who are engaged. It’s not rocket science. [HT]

6. Discussion: teachers as designers

The data provide rich insights into the complexity of diversity and bilingual education and how developing the notion of teachers as designer is being played out in one specific case study school. The exploratory factors of the conceptual framework provide detailed indicators of ways in which addressing diversity involves student-centred learning and pedagogic approaches, which teachers perceive as combining both EAL and CLIL for curriculum-making. The data provide a strong, shared, values-driven understanding of diversity by teachers and students across the entire age range. Linguistic and cultural diversity is perceived as a strength of the school, where students constantly reiterate a shared sense of belonging and feeling of living ‘global citizenship’ and the active ‘international’ framing of opportunities for all. A sense of pride emerged through encouragement to celebrate difference yet to respect and accept each other – being different feels ‘special’. The multilingual, multicultural ethos is not only reflected in the learner profile but also in that of staff, with teachers from a range of cultures and linguistic backgrounds matched by a transparent willingness from monolingual English-speaking teachers to learn other languages from and with learners.

Constant reference was made to how languages are valued – at odds with mainstream education in the UK. Students acknowledge learners have ‘different meanings’ including linguistic and learning needs alongside a range of abilities requiring different kinds of support from teachers and from each other. Reference was also made to diversity in terms of socio-economic status and the need to address poverty and safety through creating comfortable, inclusive learning spaces. The data suggest a shared sense of responsibility towards sustaining diversity as an identifiable feature of the school community exemplified through the Respect programme to ensure learning experiences are positive, challenging and meaningful for everyone.

Learners perceived their own learning as being essentially learner-centred with increasing freedom to express themselves in different modalities with support. They described opportunities for developing confidence ‘to be yourself’, nurturing their own identities through task relevance, valuing their own achievements, interests, creativity and cultural histories and backgrounds. At the same time, some students recognised that through addressing sensitive yet pertinent social issues, embedded in their school and local communities, they were developing a multicultural identity and new understandings of self and citizenship as they studied in cross-cultural meeting sites (Grant and Sleeter Citation2007).

We believe, therefore, that exploratory factors of the framework serve to map out the progress made in transforming a ‘failing’ school into a ‘good’ school (national inspection criteria). Whilst most of the data were consistently positive about achievements, thus far identifying the necessary conditions for growing ‘seeds for change,’ the contextual factors emphasised the importance of creating a dialogic space ‘where curriculum meets pedagogy’ (Lambert and Biddulph Citation2015). The workshops provided the locus for mapping ways of moving to the ‘next level’ [HT] going beyond and guarding against complacency and over-celebratory, tokenistic or tolerant approaches to increasing pedagogic capital. Here, difficult questions about the quality of learning were foregrounded alongside a challenging professional learning agenda, thereby laying the foundations for subsequent points de départ.

Initial discussion focussed on the nature of disciplinary knowledges and skills – what makes a ‘good’ geographical argument? What is an ethical decision? Who writes history? Strategies such as the STEEPLE framework fuelled discussion about working towards task-design making visible connections between language and subject literacies skills – what is the language of argumentation and how can this be learned and used? However, building on students’ cultural and linguistic life experiences initiated discussion around how an integrated and enriched curriculum might promote curriculum-making and ‘behaviours for learning’ with learners. This points to delving deeper into the nature of culturally responsive pedagogies (Pratt and Foley Citation2019) that disrupt traditional notions of cultural assimilation into ‘monolingual’ and ‘monocultural’ classrooms.

Given the recent history of the school, there is clear motivation to continue experimenting with student-centred task-design in culturally and socially sensitive ways, serving a community in challenging socio-economic circumstances. Moreover, there was a sense that increasingly involving students in relevant real-world learning will foster the emergence of a culturally responsive curriculum so that staff and students are learners together and teachers are inspired by and inspire their learners.

7. Along the pathway

There is no conclusion as such to this study since it defines and charts the on-going work of teachers as designers of learning, transforming a failing school into a successful one. At this point along the pathway, rooted in such contextual specificities, the necessary conditions for dynamic curriculum-making and learning partnerships become clear. First, conceptualisations of diversity are seen by teachers and students as enriching ways of being and becoming within the school and not as a barrier. Second, student-centred learning enacted and reported by learners encourages them to have self-belief in their own identities, their own strengths and to ‘live’ global citizenship. Third, the values-driven contextual and exploratory factors have impacted the drive for increasing numbers of subject teachers to engage in school-based professional learning, which embraces EAL-CLIL pedagogic principles, combining knowledges in a context for change led from within. Educational change takes time, transformative or adaptive pedagogies need to grow and be nurtured. A research partnership between teachers and learners, other educators and academic researchers evolves to transform principles into more sustainable classroom practices.

From professional learning (workshops) emerged ‘actionable knowledge – a form of self-organization that is fluid, dynamic and emergent’ (Antonacopoulou Citation2007) and pedagogic thinking, reflected in Mora’s (Citation2015) stance that literacies promote ‘new ecologies and literacy practices that emerge in different physical and virtual spaces where second language users dwell and operate.’

The shift from exploring CLIL approaches in EAL to teaching other subjects through English – initially for those students following the accelerated curriculum but extending to the aspire curriculum and to other languages – has significant implications. These include transparent senior leadership support for professional teacher learning across the school; sharing professional knowledge through combined pedagogies as a means to explore successful learning and satisfying national measures; teachers feeling valued and ‘safe’ when taking risks yet feeling challenged and inspired; promoting practices to encourage students to ‘extend the school curriculum by engaging with new and often troubling ideas with teachers they trust’ providing a lens on enquiring the world (Young Citation2019, 15); learning partnerships where learners are constantly challenged to progress and equipped with strategies for visibly achieving goals (Hattie Citation2009); teachers who are prepared to be learners working alongside educators and researchers to pioneer research-informed praxis. That is, the framework used in this study supports teachers as designers by providing cyclical guidance for EAL and CLIL teaching and learning practices which are ‘essentially problematic, iterative, and always improvable’ (Laurillard Citation2012), building on previous exploration, current evaluations and reflections for mapping next steps.

However, the limitations of a study such as this must also be recognised. The data gathered were from teachers deeply committed to change, given the extraordinary context they were working in and the ‘gruelling’ impact [ACT1] of moving from a ‘failing’ to a ‘good’ school. Whilst they had asked students as class representatives to participate, very few were negative about their experiences. This suggests further work might take account of a broader range of learners – talking with students in their home language alongside classroom observations would have added depth. The highly active SMT had ‘unusually’ participated in CLIL professional learning and the EAL team was engaged in co-designing the innovative PEALit programme in the aspire curriculum. This case study is not intended for generalisations – it is a given that the contextual and exploratory factors are embedded in individual case sites. Indeed, those factors significantly impacted the change process from ‘constant scrutiny’ to supportive innovative professional learning, empowering teachers to design curricula with their students.

Yet, it may be that the Conceptual Framework itself has the potential to be adapted and used more widely. Certainly, the point de départ is critical, as is planning for and supporting a commitment to professional learning as an on-going endeavour. Moreover, we feel the potential of connecting domains, especially in secondary schools holds excellent potential for teachers as designers in multilingual settings –sharing practices involves trust and time, with continued support for teacher preparation. In this case, the CLIL door was kept open since a focus on EAL also meant a focus on language and literacies not only for EAL learners but also through the potential of combined pedagogies, subsequently planned for all learners to enjoy bilingual learning, setting out specific challenges and next steps.

This study suggests that a future locus for CLIL development in England could be explored in multilingual, multicultural schools, which might have been previously overlooked due to demands on developing English progression. However, when EAL teachers and subject teachers combine their efforts as designers of ‘accessible’ bilingual learning and involve the integration of literacies approaches prevalent in EAL adapted for CLIL classes across languages and cultures, the findings suggest potential worthy of serious exploration. We suggest, therefore, that the values-driven contextual and exploratory factors () used to guide this study provide a useful framework for building pedagogic capital where teachers and learners are designers of learning. This framework can be shared, adopted and adapted across other diverse, bilingual and multilingual contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Do Coyle

Do Coyle holds Chair in Languages Education and Classroom Learning at Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh and leads the Language, Interculturality and Literacies Research Hub.

Kim Bower

Kim Bower holds Chair in Innovation in Languages Education at the Sheffield Institute of Education, Sheffield Hallam University and is President of the Association of Language Learning.

Yvonne Foley

Yvonne Foley is Head of Institute for Education, Teaching and Leadership (IETL) and Senior Lecturer at Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh.

Jonathan Hancock

Jonathan Hancock is Research Associate at Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh.

References

- Ainscow, M., T. Booth, A. Dyson, P. Farrell, J. Frankham, F. Gallannaugh, A. Howes, and R. Smith. 2006. Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. London: Routledge.

- Antonacopoulou, E. 2007. “Actionable Knowledge.” In International Encyclopaedia of Organization Studies, edited by S. Clegg, and J. Bailey. London: Sage.

- Barnett, R., and N. Jackson. 2020. Ecologies for Learning and Practice: Emerging Ideas, Sightings and Possibilities. London: Routledge.

- Barwell, R. 2005. “Integrating Language and Content: Issues from the Mathematics Classroom.” Linguistics and Education 16 (2): 205–218. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2006.01.002.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 2006. Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future. Boulder: Paradigm.

- British Educational Research Council (BERA). 2011. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research 2011. London: BERA.

- Bruton, A. 2015. “CLIL: Detail Matters in the Whole Picture. More Than a Reply to J. Hüttner and U. Smit (2014).” System 53: 119–128. doi:10.1016/j.system.2015.07.005.

- Bryman, A. 2004. Social Research Methods. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cenoz, J., F. Genesee, and D. Gorter. 2014. “Critical Analysis of CLIL: Taking Stock and Looking Forward.” Applied Linguistics 35 (3): 243–262. doi:10.1093/applin/amt011.

- Cochran-Smith, M. 2003. “The Unforgiving Complexity of Teaching: Avoiding Simplicity in the Age of Accountability.” Journal of Teacher Education 54 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1177/0022487102238653.

- Conteh, J. 2012. Teaching Bilingual and EAL Learners in Primary Schools. London: Sage Publications.

- Costley, T., and C. Leung. 2009. “English as an Additional Language Across the Curriculum: Policies in Practice.” In Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Classrooms: New Dilemmas for Teachers, edited by J. Miller, A. Kostogriz, and M. Gearon, 151–171. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Coyle, D. 2018. “The Place of CLIL in (Bilingual) Education.” Theory Into Practice 57 (3): 166–176. doi:10.1080/00405841.2018.1459096.

- Coyle, D., P. Hood, and D. Marsh. 2010. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cuban, L. 2013. “Why so Many Structural Changes in Schools and so Little Reform in Teaching Practice?” Journal of Educational Administration 51 (2): 109–125.

- Dale, E. M. 2020. On Language Teachers and CLIL: Shifting the Perspectives. Amsterdam: Kenniscentrum Onderwijs en Opvoeding.

- Dalton-Puffer, C., A. Llinares, F. Lorenzo, and T. Nikula. 2014. “‘You Can Stand Under My Umbrella’: Immersion, CLIL and Bilingual Education. A Response to Cenoz, Genesee, and Gorter (2013).” Applied Linguistics 35 (2): 213–218.

- de Jong, E. J., and C. A. Harper. 2005. “Preparing Mainstream Teachers for English-Language Learners: Is Being a Good Teacher Good Enough?” Teacher Education Quarterly 32 (2): 101–124.

- Department for Education (DfE). 2020. Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics: January 2020. London: Department of Education.

- Dobson, A. 2020. “Context Is Everything: Reflections on CLIL in the UK.” The Language Learning Journal 48 (5): 508–518. doi:10.1080/09571736.2020.1804104.

- Feldman, A., and B. C. Herman. 2015. “Teacher Contextual Knowledge.” In Encyclopedia of Science Education, edited by R. Gunstone. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Foley, Y., C. Anderson, J. Conteh, and J. Hancock. 2018. Initial Teacher Education and English as an Additional Language. Research Report: Bell Foundation/Unbound Philanthropy.

- Fullan, M., and M. Langworthy. 2014. A Rich Seam: How new Pedagogies Find Deep Learning. London: Pearson.

- Garcia, O. 2009. Bilingual Education in the Twenty-First Century: A Global Perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gay, G. 2018. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. 3rd Edition. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gibbons, P. 2018. “What Is Academic Literacy and Who Should Teach It?” EAL Journal 6: 56–62.

- Grant, C. A., and E. Sleeter. 2007. Doing Multicultural Education for Achievement. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Halbach, A. 2020. “English Language Teaching Goes CLIL: Fostering Literacy and Language Development in Secondary Schools in Spain.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language Education Curriculum Design, edited by P. Mickan, and I. Wallace. Oxford: Routledge.

- Harris, R., and C. Leung. 2011. “English as an Additional Language: Challenges of Language and Identity in the Multi-Lingual and Multi-Ethnic Classroom.” In Becoming a Teacher: Issues in Secondary Education, edited by J. Dillon, and M. Maguire, 203–215. New York: Open University Press.

- Hattie, J. A. C. 2009. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge.

- Janks, H. 2010. Literacy and Power. London and New York: Routledge.

- Järvinen, H. M. 2005. “Language Learning in Content-Based Instruction.” In Investigations in Second Language Acquisition, edited by A. Housen, and M. Pierrard, 433–456. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Lambert, D., and M. Biddulph. 2015. “The Dialogic Space Offered by Curriculum-Making in the Process of Learning to Teach, and the Creation of a Progressive Knowledge-led Curriculum.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 43 (3): 210–224. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2014.934197.

- Laurillard, D. 2012. Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology. London: Routledge.

- Leung, C. 2005. “English as an Additional Language Policy: Issues of Inclusive Access and Language.” Prospect 20 (1): 95–113.

- Leung, C. 2012. “English as an Additional Language Policy-Rendered Theory and Classroom Interaction.” In Multilingualism, Discourse, and Ethnography, edited by S. Gardner, and M. Martin-Jones, 222–240. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lyster, R. 2007. Learning and Teaching Languages Through Content: A Counter-Balanced Approach. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

- Maxwell, J. A. 2013. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. 3rd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Merriam, S. B. 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Messiou, K., and M. Ainscow. 2020. “Inclusive Inquiry: Student-Teacher Dialogue as a Means of Promoting Inclusion in Schools.” British Educational Research Journal 46 (3): 670–687. doi:10.1002/berj.3602.

- Meyer, O., and D. Coyle. 2017. “Pluriliteracies Teaching for Learning: Conceptualizing Progression for Deeper Learning in Literacies Development.” European Journal of Applied Linguistics 5 (2): 199–222.

- Meyer, O., D. Coyle, A. Halbach, T. Ting, and K. Schuck. 2015. ““A Pluriliteracies Approach to Content and Language Integrated Learning: Mapping Learner Progressions in Knowledge Construction and Meaning-Making.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 28 (1): 41–57.

- Mora, R. A. 2015. “Rethinking today’s language ecologies: New questions about language use and literacy practices” [Webinar]. In Global Conversations in Literacy Research. Available at https://youtu.be/CMLnXwx3lRY.

- Morton, T. 2018. “What Does the Research on Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Tell us About EAL?” EAL Journal 6: 56–62.

- OECD. 2018. Education 2030: The Future of Education and Skills. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/.

- Ofsted. 2020. Inspection of December 2019. Ofsted Inspection Report. https://files.ofsted.gov.uk/v1/file/50143397.

- Paniagua, A., and D. Istance. 2018. Teachers as Designers of Learning Environments: The Importance of Innovative Pedagogies.” Educational Research and Innovation. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Pérez-Cañado, M. L. 2020. “What’s Hot and What’s Not on the Current CLIL Research Agenda: Weeding Out the non-Issues from the Real Issues. A Response to Bruton (2019).” Applied Linguistics Review.

- Pratt, L., and Y. Foley. 2019. “Using Critical Literacy to ‘do’ Identity and Gender.” In Social Justice Re-Examined: Dilemmas and Solutions for the Classroom Teacher, edited by R. Arshad, T. Wrigley, and L. Pratt, 72–91. London: UCL Institute of Education Press.

- Reeves, J. 2004. “‘Like Everybody Else’: Equalizing Educational Opportunity for English Language Learners.” TESOL Quarterly 38: 43–66.

- Stake, R. E. 2005. “Qualitative Case Studies.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln, 443–466. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Thomas, G. 2011. “A Typology for the Case Study in Social Science Following a Review of Definition, Discourse, and Structure.” Qualitative Inquiry 17 (6): 511–521.

- Van Mensel, L., P. Hiligsmann, L. Mettewie, and B. Galand. 2020. ““CLIL, an Elitist Language Learning Approach? A Background Analysis of English and Dutch CLIL Pupils in French-Speaking Belgium.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 33 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/07908318.2019.1571078.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-diversity and its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods Fourth Edition, Vol. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Young, M. 2019. “Conceptualising the Curriculum.” In Re-Examining the Curriculum. London: BERA Research Intelligence Spring 2019.

Appendices

Appendix 1a: Semi-Structured Teacher Interview Questions

Teacher semi-structured interview questions bank*

1. Diversity

What are the challenges of diversity in ability/cultures/languages/societal and economic factors?

What kind of support techniques or strategies do you use?

What’s the role of English/mother tongue in differentiation for individual learners?

What kind of training (if any) have you been offered/undertaken for teaching CLIL/English?

2. Classroom learning

What kinds of learner needs present themselves in CLIL/accelerated English classes?

What kind of methods/activities/groupings do you use when differentiating?

How do you personalize support (for individuals/small groups)? How about peer support among students?

Is there any cross-curricular/departmental/school planning to ensure individual needs are met across?

3. Materials and resources

What materials do you use to cater for different abilities/ other needs among learners?

Do you adapt materials to differentiate? How?

What’s the role of technology in teaching and learning to meet individual needs?

4. Professional Learning and Teacher Development

How does CLIL and EAL/accelerated English impact on your practice?

How do you collaborate with your colleagues to support learners’ individual needs?

What is the role of other adults, e.g. multi-professional teams, parents, community?

5. Reflections

What are the successes and where to next?

What needs attention to improve learner and teacher learning?

How would you describe your experiences?

* note the interviews evolved into conversations where data was gathered through transcribing these conversations but which were guided by some of the above.

Appendix 1b: Student Focus Group discussion questions

Student semi-structured interview questions bank*

1. Diversity

What do you understand by diversity? What different kinds are there?

What kind of support strategies do you use for learning?

How many languages do you speak? When do you use English / or your first language?

How do you know you are making progress in English?

2. Classroom learning

How do you learn best in class (CLIL /accelerated English)?

What kind of grouping do you prefer?

How does your teacher give you the support you need?

Does your work link with other areas of the curriculum?

3. Materials and resources

What materials help you most?

Do you have individual worksheets?

What kind of technology do you use?

4. Reflections

What have you achieved? What are your successes? and where to next?

What difficulties did you have? How are they resolved?

How would you describe your learning?

Appendix 2

24 Cards used for Prioritisation Task in Student Focus Groups

Pupils were asked to select up to nine cards from the list below, put them in order of priority and preference (Diamond 9) that reflected their understanding of diversity

Teachers who speak languages other than the main language of school

Teachers who use different ways of enabling different learners to learn

Teachers from different countries

Teachers who value diversity in their classrooms

Teachers who value difference and see it as an advantage

Teachers who believe in us regardless of what we look like and who we are

Teacher strategies which are individual and value different ways of learning

Schools which welcome our families and communities

Schools which celebrate our cultural and linguistic unity

School work which everyone can do in different ways and feel a sense of achievement

Students who respect and value each other

Students with different (cultural) identities

Students from families with different religions and beliefs

Students who struggle with their schoolwork

Students who are successful in school

Students with physical abilities and disabilities

Students who do not feel excluded or problematic

Students from less advantaged homes

Students from more advantaged homes

Students who speak languages other than English

Students from different countries

Students feel a sense of achievement

Students who want to work together – unity in diversity

Students who value difference and see it as an advantage