ABSTRACT

Apart from linguistic diversity and multilingualism, empirical research into diversity is only in its beginnings in the Austrian educational context. CLIL research, on the other hand, is well-established but has not tended to focus on pedagogical practices. This study explores teachers’ and students’ self-reported experiences in Austrian CLIL classrooms with regard to the phenomenon of diversity and the pedagogical practices addressing it. This mixed-methods study used the research instruments (questionnaires, interview guides) developed in the ADiBE project. Three Viennese secondary schools with two classes each participated in the study. In total, 132 students answered the questionnaires. Six focus group interviews with 6–8 participants were conducted (one for each participating class). Teacher questionnaires were distributed in but also beyond the participating schools (N = 30), and eight teachers from the participating schools were interviewed. With regard to the phenomenon of diversity as such, our results suggest a system-inherent ambivalence between segregation and egalitarianism. Concerning pedagogical practices during CLIL lessons, such as language scaffolding, learner-centred design or use of German, the responses of students and teachers show that different aspects of classroom reality carry different weight with the two groups of participants.

1. Introduction

Since its beginnings in the early 1990s, CLIL has established itself in Austria, both as a teaching programme and as a research focus. This is reflected in a wide range of CLIL realisations in schools from primary to upper secondary level as well as in a rich and increasingly growing research literature that covers such diverse topics as CLIL programmes, student learning outcomes, teacher motivation and CLIL classroom discourse. One topic area that has attracted surprisingly little attention so far, however, is at the heart of the ADiBE project: diversity in CLIL and how this is identified, catered for and integrated in educational practices.

While the reasons for this oversight might be multi-layered, reflecting factors such as the comparative recency of CLIL, its original nature as a fringe educational endeavour, researchers’ interests or, more generally, the education system and its underlying ideology of grouping learners according to supposed academic abilities, present-day Austrian educational realities certainly call for concerted research efforts focusing on learners as individuals, recognising and responding to their diverse competences, skills and abilities. Furthermore, and as typical of twenty-first century societies, the population of school-goers in Austria is generally highly dynamic and socio-linguistically varied, a diversity that permeates all school types and levels. At the same time, CLIL has been developing into a more mainstream undertaking. The resulting heterogeneity of learners who are increasingly engaged in educational practices in two languages has thus become part and parcel of Austrian school realities and merits focused research.

In an endeavour to address this research gap, this paper presents the Austrian part of the ADiBE project by combining quantitative and qualitative datasets exploring teacher and student notions and experiences of pedagogical practices in relation to diversity. Before zooming in on the study itself, we start by sketching Austrian CLIL policies and pertinent research findings.

2. CLIL in Austria

2.1. Policy and practice

Similar to other European countries, Austrian educational language policy combines the national language, i.e. German, as the default language of schooling with foreign language (FL) teaching. While compulsory from grade 1 and theoretically inclusive of a range of languages, FL teaching is practically restricted to English for almost all learners up to grade 7 and for a majority until the end of their secondary education (Nagel et al. Citation2012). Given this unique role that English plays as a second/foreign language in Austrian schools, it is not surprising that, with very few exceptions, CLIL in Austria actually means CEIL, i.e. Content and English Integrated Learning (Dalton-Puffer, Nikula, and Smit Citation2010). This has been the case since the first grassroots undertakings emerged in the 1990s, when usually highly engaged and enthusiastic teachers, often with double degrees in English and another subject, decided to use English for some of their content teaching. These CLIL initiatives generally received positive feedback and encouragement from school heads, parents and learners, but for a good decade there was surprisingly little support and guidance from the educational authorities. This resulted in many CLIL practices retaining their nature of being bottom-up and flexible, but also of being fleeting and often not sustainable (Dalton-Puffer Citation2007).

With the turn of the century, however, such grassroots CLIL started to be complemented by structured CLIL programmes, two of which are in focus in this paper: the ‘Dual Language Programme’ (DLP) in selected Viennese schools (at primary and secondary levels) and ‘CLIL for HTL (= Höhere Technische Lehranstalten)’ in all Austrian higher technical colleges. The DLP, which started in 2006, offers CLIL in a modular format with ‘increased authentic language input through team teaching with Native Speaker Teachers (NSTs)’ (Vienna Board of Education Citation2016, 3). Which topics and subjects are taught in CLIL depends on the local conditions at each DLP school and on the availability of subject and native speaker teachers.

While the DLP is an educational project that schools need to apply for, ‘CLIL for HTL’ was instituted by ministerial decree in 2011, enforcing CLIL for all students in Austrian higher technical colleges (HTL). This school type (ISCED 5V; BMBWF Citation2018) combines general upper secondary education with a technical specialisation, such as IT, electrical or mechanical engineering or mechatronics, thus allowing graduates to enrol at university at the same time as providing them with the technical expertise required by business and industry. As a consequence of this double-barrelled educational aim, obligatory foreign language teaching is limited to English only and to two weekly lessons, resulting in generally lower proficiency levels than in other upper secondary school types. Highly aware of the work-related relevance of English for their graduates’ professional future, however, HTLs actively engaged in early CLIL activities. A nationwide survey revealed that in 2007/08, 65% of all HTLs used some form of English-medium content teaching and many more intended to do so in the future (Dalton-Puffer et al. Citation2009; Hüttner, Dalton-Puffer, and Smit Citation2013). In 48 interviews undertaken at five different schools, teachers and students expressed their positive views of CLIL practices as such while at the same time criticising what they perceived as a lack of coherence and structure. Reacting to such evaluations, the Federal Ministry of Education introduced the afore-mentioned top-down regulations that have made CLIL obligatory for all HTL students in at least 72 lessons in grades 11 and 12 and 40 lessons in grade 13. Which subjects, topics and teachers are chosen is in the remit of the individual school when developing their localised CLIL programme. Recommendations specify that English and content teachers should work together and that technical subjects should be prioritised over general academic ones (BMB Citation2011).

No matter whether grassroots or programme-based, CLIL implementations in Austria generally display a high degree of situatedness in that local factors play a crucial role in what CLIL actually looks like. What programmes do offer, though, is some structure and continuity, and in the case of the DLP also some extra support in the form of native speaker teachers. As regards student selection, the two programme-based implementations considered in this paper differ: ‘CLIL for HTL’ involves all students and is thus non-selective, while DLP schools do select for their CLIL groups by interviewing applicants, even if in a rather low-threshold manner. Additionally, it is important to know that, irrespective of CLIL, the Austrian educational system is fundamentally selective as it splits all students into two strands after the four primary years (ISCED 1): AHS (= Allgemeinbildende höhere Schulen; academic secondary schools, ISCED 2 and 3G) offer pre-academic education, while ‘middle schools’ (ISCED 2) focus on pre-vocational education. Repeatedly criticised for entrenching a socio-economic divide (OECD Citation2017, 7), the choice parents have to make after primary school causes a systematic type of student selection that runs through all of secondary and tertiary education, implying that any secondary-level educational programme is selective to a certain degree.

2.2. CLIL research in Austria

Reflecting the diverse but widespread practice of CLIL in Austria, the Austrian CLIL research scene can be described as active and multi-facetted. One current, dominant area relates to the perspectives of the participants, particularly in the HTL context, since this was the first school type with obligatory CLIL. Studies by Hüttner, Dalton-Puffer, and Smit (Citation2013), Smit and Finker (Citation2018) or Döring (Citation2020) all indicate that participants appear appreciative and motivated regarding their CLIL education, describing CLIL lessons as more relaxed, collaborative and student-friendly due to more explaining and a slower pace in contrast to their traditional lessons. Yet these studies also report issues relating to practical implementation and pedagogic design. For similar results in a different upper secondary school type see Bauer-Marschallinger (Citation2019, Citation2020), whose participants voiced a need for a more scaffolded approach to help them navigate challenging input and express their thoughts. With regard to CLIL teachers at lower secondary level, Gierlinger (Citation2017) found that they often struggle with conceptualising the role of language for their content teaching.

In relation to pedagogical practices, Dalton-Puffer et al. (Citation2018) observed that the verbalisations of content-oriented cognitive operations shape and drive subject-specific discourse in CLIL lessons across a range of subjects. Throughout the lessons, teachers regularly model such cognitive discourse functions and frequently co-construct them with learners. Similarly, Hüttner and Smit (Citation2018), who analysed episodes of negotiating political positions, found that the teacher and students often collaboratively produce such argumentative sequences, with the teacher taking on the role of ‘expert’, scaffolding the process. Hüttner and Smit (Citation2018) also report that sometimes teachers draw on their L1 to scaffold knowledge construction. This matches the results of several studies in the Austrian context observing that the L1 is often used as a ‘fall-back option that facilitates comprehension and fluency’ (Smit and Finker Citation2018, 18; see also Dalton-Puffer Citation2007; Gierlinger Citation2015). In this regard, Gierlinger (Citation2015) identified several didactic purposes for L1 use on the basis of video-taped lessons at lower secondary level, teacher interviews and stimulated recall reflections. These didactic purposes include classroom management, giving instructions, terminology- and content-related recaps for clarification and comprehension as well as considering language deficits.

Apart from the studies mentioned above, relatively little attention has been paid to pedagogical practices in the classroom, which also seems to be the case for the international CLIL research scene. While many CLIL researchers have elaborated pedagogical principles for CLIL lessons or materials (see, for instance, Ball, Kelly, and Clegg Citation2015; Banegas Citation2017; Mehisto, Marsh, and Frigols Citation2009; Meyer Citation2013; Moore and Lorenzo Citation2015), few CLIL studies examine teachers’ reported or observed pedagogical practices. In one such study, based on lesson observation and teacher interviews, de Graaff, Koopman, and Westhoff (Citation2007) identified several effective pedagogical practices in CLIL settings. Their list includes scaffolding content-related concepts, explicit linguistic instruction, interactive and output-oriented activities, and fostering compensation strategies (e.g. the use of dictionaries). Also in the Dutch context, van Kampen, Admiraal, and Berry (Citation2018) found that CLIL teachers report that they, generally, design more communicative lessons and pay more attention to scaffolding compared to their traditional lessons but also that they would not explicitly discuss aspects of language or subject literacy. Some teachers, however, felt that their CLIL lessons did not differ from their traditional lessons (see also Badertscher and Bieri [Citation2009] for similar results from Switzerland). In Norway, Mahan, Brevik, and Ødegaard (Citation2021) and Mahan (Citation2020) found that CLIL teachers use the L2 over 80% of the time and also employ a range of scaffolding techniques to facilitate comprehension, such as the use of visual support and body language, creating opportunities for the negotiation of meaning or the clarification of terminology as well as frequent linking to previous knowledge. However, Mahan (Citation2020) observed little meta-cognitive and task-solving scaffolding, like modelling thinking processes and communication strategies.

Considering that only relatively few studies have dealt with pedagogical practices in general, it is not surprising that even less attention has been paid to pedagogical practices catering for different levels of ability. One rare example would be Lialikhova (Citation2019), who examined peer interaction and scaffolding in a class of 9th grade history learners at different levels of ability. She found that while mid- and high-achievers could collaboratively engage with demanding content, the low-achieving group needed the teacher's scaffolding to perform the tasks. Therefore, Lialikhova (Citation2019) calls for better language support and scaffolding more generally to be implemented in CLIL, a suggestion that resonates with other researchers in the field (e.g. Roussel et al. [Citation2017] or Madrid and Pérez Cañado [Citation2018]). Madrid and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018), who reviewed relevant literature concerning diversity and CLIL, present a list of viable strategies to cater to different needs in CLIL, including, for example, ensuring learner-centred, flexible teaching methods that enable differentiated instruction and individualised pedagogical practices (see also Pérez Cañado, Citationthis issue, who offers a conceptualisation of diversity in CLIL and how it can be catered for in an integrated way). Furthermore, Madrid and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018) mention team-teaching, rapport, safe learning environments, ongoing feedback, ICT, multiple intelligences and articulating clearly and slowly. Although awareness concerning diversity in CLIL settings has somewhat increased, Madrid and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018) stress that there is a considerable lack of research and teacher resources, including teaching materials and in-service training. This implies that focused attention on this particular issue is also warranted for CLIL in the Austrian education system.

As mentioned above, in Austria all learners are split into different lower and then upper secondary level school types in grades 5 and 9. An ideological battleground for decades, segregation on the systemic level is widely seen as ‘paying off’ in terms of homogeneity within the segregated sectors, a position that is strongly contested by educational experts in view of growing societal diversity and heterogeneity (e.g. Biewer, Proyer, and Kremsner Citation2019; Feyerer Citation2019), although not necessarily in society at large. In a nutshell, in our view the Austrian education system is characterised by a significant amount of ambivalence with regard to diversity and equity, a co-existence of segregationism and egalitarianism. The position of CLIL amidst this ambivalence is quite complex: CLIL is partially bottom-up and teacher-driven, partially top-down and system-inherent, with some of it a matter of choice or selection and some of it not. In view of such multi-layered parameters, it can be expected that CLIL learner groups will vary in terms of diversity and it is certainly important to find out more about the range of pedagogical practices encountered in such scenarios, including how teachers and students perceive them.

As a first paper to address such concerns, we have formulated the following five research questions, which are also central to the ADiBE project:

RQ1: How do participants see diversity?

RQ2: How do teachers support students during CLIL lessons?

RQ3: To what extent is German used as support for weaker students?

RQ4: How do students support one another?

RQ5: To what extent is CLIL more learner-oriented?

3. Study design

For the present article we analysed the data collected with the ADiBE questionnaires (teachers, students) and semi-structured interviews (individual teachers, student focus groups; for more information on the instruments and the piloting process for their validation see Pérez Cañado, Rascón Moreno, and Cueva López, Citation2021). The questionnaires were translated into German collaboratively by the German and Austrian teams; some technical terms were adapted to fit the Austrian educational context as well as the students’ expected background knowledge. Answers to our research questions were pursued by way of a quantitative analysis of relevant questionnaire items as indicated in the results sections. The analysis of the interview and focus-group transcripts was conducted by all authors engaging jointly in iterative rounds of qualitative content analysis (Dörnyei Citation2007). After a first-level deductively and inductively combined coding of all transcript segments relevant for the research questions, a second-level comparative coding resulted in the overall themes of understanding of diversity, teacher support, including the use of German, peer support and learner-centredness.

3.1. Participants

In response to the research invitation we sent to our network of CLIL teachers, three Viennese schools participated in the Austrian arm of the study in the autumn of 2019. This purposeful convenience sampling (Dörnyei Citation2007) allowed us to collect student data from the questionnaires and focus groups in two classes per school. Four of the classes were in the lower level of two AHS schools that have participated in the Vienna Board of Education's DLP since 2006/07 and 2012/13 respectively. The other two classes were at an HTL. Seventh grade students in Austria are typically 12–13 years old and eleventh graders 16–17. The number of students per class (20–26 for the lower level AHS and 15–24 for HTL) is not unusual for the grade/school type ().

Table 1. Average age of students; number of questionnaires and participants in focus groups.

The 132 student questionnaires confirmed the tendency for more girls to choose CLIL in AHS schools and for more boys to attend an HTL. Ten of the 93 AHS students had experience of CLIL from primary school. Whereas only 20.6% of AHS students nationwide spoke a language other than German at home in the academic year 2018/19, 40.2% in Vienna fell into this category; the equivalent statistics for HTLs were 19.6% and 38.3% (Statistik Austria Citation2019). Some of the CLIL classes in the project reflect this division while others do not, with the proportion of students who speak only German at home varying from 33.3% (HTL_g11_B) to 80% (AHS1_g8). English was spoken at home by students attending three of the four AHS classes (4.5–20.0% per class). Other home languages were Croatian (6), Serbian or Turkish (4 each), Slovak, Spanish, Italian, Arabic or Tagalog (3 each), Bosnian, Romanian or French (2 each) and Chinese, Dari, Georgian, Hungarian, Indian, Japanese, Pashto, Polish or Russian (1 each).

Fifteen teachers at each school type filled in the questionnaire: ten at AHS1, five at AHS2, seven at the HTL in Vienna and another eight via an Austrian-wide CLIL mailing list or personal contacts. Eight teachers were also interviewed. Nearly two thirds of the respondents at the AHSs were female (60.0%); the opposite was true at the HTLs, with 66.7% being male. The age range was similar at both school types but the average age was somewhat higher at the HTLs. In Austria, almost all AHS teachers and some HTL teachers have two subjects; specialist teachers at HTLs tend just to teach in one subject area. This explains why more than 15 subject areas are taught ().

Table 2. Number of teacher questionnaires and interviews; gender and age; subject area(s) taught.

In terms of the teachers’ self-assessed CEFR levels, four of the English teachers and one native speaker at an AHS chose C2, as did two of the English teachers, a native speaker, and three content teachers at an HTL; the other two language teachers and five content teachers selected C1. It is well known that the English component of the school-leaving examination in Austria is defined as being at level B2; the other seven content teachers without a foreign language as their other subject identified with this level, presumably aware of how good students’ English is in the final year of school. Two of the HTL teachers assessed themselves as being at level A2. In relation to the number of years of teaching experience, the AHS teachers appear to start teaching CLIL at an earlier stage in their careers than the HTL teachers. Apart from the two native speaker teachers, 80% of the teachers in both school types spoke German as their mother tongue and two HTL teachers had multilingual home backgrounds (German and English; German, Turkish and Bosnian). Two of the AHS teachers did not respond to either of the language items.

4. Results

In the following five subsections, the results of each research question are presented by school type (AHS, HTL). With the exception of research question 1, questionnaire items were selected which covered similar ground to information extracted from the interviews with students and teachers.

RQ1: How do participants see diversity?

In one group, learners reported some initial differences but felt that these have mostly been levelled out by the third/fourth year of CLIL. Some also mentioned that they and their peers had been selected for participation in the CLIL stream so ‘certain basic skills’ (AHS1_g8_S) could be expected. Therefore, they also rejected the idea of creating different tasks for learners of different abilities in tests. Only one student mentioned their dyslexia and the fact that the English teacher gave them more time to write their test. During the lessons, they would also not expect differentiated tasks, as ‘you should try to reduce differences and not increase them’ (AHS1_g8_S). At the same time, these learners seemed to be aware of having different weaknesses and talents as they claimed to be playing to their different strengths during group work.

Similarly, the AHS teachers felt that their CLIL classes were less diverse in terms of ability levels than their mainstream classes as a result of the initial selection process. Yet, reacting to the students’ view that they were all similarly gifted, some AHS teachers appreciated the students’ sense of equality but disagreed, nonetheless. When talking about learner differences, the AHS teachers appeared to focus more on content-related issues as they assumed that these were independent of the choice of working language whereas their students mostly talked about their English proficiency.

In the HTL context, similar observations were made. Like their AHS counterparts, the HTL students negated that there was any diversity in academic abilities that would need to be catered for, as indicated in statements like ‘we are all rather at the same level’ (HTL_g11_B_S) or ‘we all speak English equally well’ (HTL_g11_A_S).

Just like the AHS teachers, the HTL teachers could not confirm such a lack of diversity, reporting differences in English language skills and subject-specific abilities. Moreover, T7 felt that the use of a foreign language would widen the gap between weaker and stronger students, pushing those learners with good English skills while ‘handicapping’ less skilled learners.

Since this research question emerged from the interview data a posteriori, no questionnaire items were identified covering this particular point. Nonetheless, it appeared crucial to document how the participants of our study understand and experience diversity to contextualise the results provided below.

RQ2: How do teachers support students during lessons?

For the AHS teachers and students, the quantitative results for all three areas show a divergence between how much of a desirable behaviour is reported by the teachers versus how much of it seems to be perceived by the students. Interestingly, student perception of language support is stronger (85% agree) than what teachers report to practise (approx. 60% agree), while for the other two aspects (content support: students 46.3% vs. teachers 53.3%; teaching methods: students 50.6% vs. teachers 59.9%) the opposite is the case, albeit with less divergence. The perceived prevalence of language support may be connected to the fact that in both AHS schools, native speaker teachers are a regular feature of CLIL lessons, where they often help during group and individual work.

The AHS teachers interviewed reported that they would not plan for diversity strategically because their students were already handpicked and were thus not as diverse as mainstream groups. Moreover, they simply would not have the time to consider this aspect extensively in their planning. However, they argued that the existence of different needs and levels of ability was always at the back of their minds more globally. In other words, they prepare materials that try to support a variety of learners by targeting a healthy mix of learner styles, modalities, levels of difficulty and social formats, etc. The teachers also stressed the importance of clear, purposeful tasks, allowing all learners to contribute something.

Spontaneous and individual help was mentioned by all teachers as a means to ensure that all learners are well supported. They all maintained that they would always provide help individually while the learners were working through the lesson. This was mirrored in the student focus groups, as students said they got individual support whenever they asked for it, be it via further explanation, repetition, teacher-elicited peer explanations or slowed-down video clips. Interestingly the learners did not interpret the different modalities and task types found on worksheets and in activities as addressing learner diversity. With regard to the AHS dataset, RQ2 can be summarised by T2's statement, ‘I do think we cater for different ability levels, but not an awful lot’.

In the quantitative HTL dataset, we also find a divergence between teacher and student perceptions: students report getting more language and content support than the teachers say they give. In fact, 40% of the HTL teacher respondents indicated that they give neither language nor content support. It is only in the area of support through teaching methodology that the teachers had a somewhat more affirmative perception of their own practices than was reported by the students, this being in parallel to the AHS respondents. However, we cannot assume that students in general have a highly reflective approach to questions of teaching methodologies, their rationales and purposes.

The HTL interview data both echoed and enriched the quantitative results. As far as the students could say on the basis of their still limited CLIL experience, there was no explicit attention paid to learners with different academic strengths. What teachers tended to do was to combine CLIL units with less demanding contents. Additionally, the HTL students mentioned that teachers provided additional materials in English, either as YouTube videos or self-produced written notes. The latter include explanations or definitions of important technical vocabulary. Technical or other words are also topicalised in class, where online tools are used to translate and explain them.

The two HTL teachers’ accounts mirror the students’ reports. While they did not differentiate between learners in terms of academic strengths, they were acutely aware of possible differences in English proficiency levels. T8 mentioned that they catered for such differences by staggering the targeted communication skills by year. Their CLIL lessons in 11th grade aim at receptive skills combined with non-language output, while by the 13th grade, students also engage in role plays, discussions and staging meetings. T7, on the other hand, put the students in mixed-language-ability groups to complete their tasks.

On the level of assessment and across school types, Austrian national legislation for all classes that are not officially integrative forecloses individualised summative assessment practices. Exceptions occur when someone has an official diagnosis of dyslexia but only for language subjects (thus not CLIL). This means that teachers cannot legally differentiate between ability levels in summative assessment. Across both school types, it is apparent that assessment in CLIL is largely formative in nature, practised as capturing what students can do and the amount of effort they put into their work.

RQ3: To what extent is German used as support for weaker students?

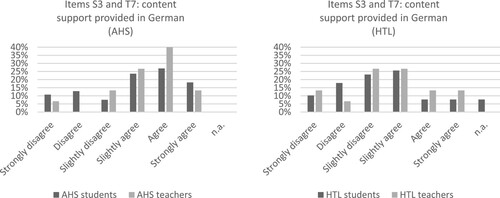

The item in the questionnaires (S3 and T7) on using German to provide additional support for weaker students expressly refers to parts of a lesson being repeated. Here, too, in both school types teachers were slightly more affirmative than students about this practice ().

As both AHS schools follow the Vienna Dual Language Programme, where the use of L1 German has a fixed role in the overall concept, it is not surprising that AHS answers in the survey showed higher frequencies of L1 use than the HTL answers. In that sense, it was somewhat unexpected to see in the interviews that L1 use practices actually varied as much in the AHSs as in the HTL, presumably depending on individual teachers’ preferences.

All AHS teachers reported using the L1 at least sometimes. T3, T4 and T5 all said that they used German purposefully to ensure comprehension by all learners, especially weaker students. Reasons for using the L1 include clarifying vocabulary (e.g. via glossaries or writing words on the blackboard), explaining difficult concepts, revising content or adding a different perspective. T4 usually introduces new content in German to ensure that everybody understands and only later switches to English. Some teachers also mentioned that they would switch to either language in order to keep up interest but code-switching could also happen randomly and students were always allowed to do so. During group work, learners are encouraged to use English, especially by the native speaker teachers but, again, learners could always just switch.

AHS students found the L1 important for their understanding of content irrespective of their academic strengths and appreciated systematic teacher attention to this aspect, for example in the shape of bilingual worksheets, glossaries and key terms on the board in both languages. Their experience of L1 use varied from teacher to teacher, having to expressly ask some teachers for translations. In terms of cross-language repetition, the usual sequence appears to be first in English, then in German, but learners would appreciate some variation there.

Much in the same way, none of the HTL interview partners topicalised German as support specifically for weaker students but the use of German was seen as making CLIL lessons more accessible in general, especially when dealing with topics that are already considered difficult in German. To reach all ‘blockages from forming already at this point’. T8, on the other hand, did not consider switching to German necessary for the topics selected for CLIL since they were simple enough. Students reported on diverse practices that usually depend on the teacher: some stick to English exclusively, others use German maybe also to help themselves, while others again combine both languages for explaining technical vocabulary and/or for introducing and later revising certain topics. In the latter case, English can be used for the first or the second phase, with German reserved for the other one. Such a pedagogical use of translanguaging was also suggested by one student (in HTL_g11_A), who recommended that the key points of a topic should be made available in German while developing it in class in English.

RQ4: How do students support one another?

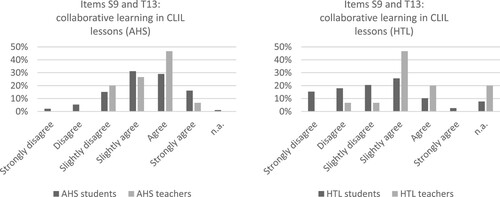

While the AHS responses showed a tendency on the positive side for teachers and students, with the usual penchant for greater teacher optimism, the HTL responses diverged strongly: 80% of students reported a low incidence of pair or group work, while approximately 90% of the teachers’ responses were on the positive side ().

Mutual student support is not an official feature of the AHS classrooms (as would be formal study groups or tandems, for example) but certainly seems to be a regular feature inherent in most AHS CLIL lessons. The AHS teachers repeatedly mentioned peer support, pair work and group work as means to balance out different learning paces, ability levels and talents but also to help weaker students cope.

In keeping with this, AHS students said they asked one another for explanations and divided up group work so that everyone could work to their strengths (or so they say). They emphasised particularly how much they liked to prepare peer presentations and claimed they could understand content better and remember more details when something was presented by a peer. The same seems to be true of HTL students, where one student group wished they had more group and pair work so that students could explain topics to one another: ‘students among themselves always understand one another better than when the teacher explains it’ (HTL_g11_B_S).

In both sets of teacher interviews, it seems that pair or group work is generally considered a viable way to support students in fulfilling tasks. However, the interviewees said that they usually do not form groups following a specific pedagogical aim. Instead, they organise groups based on circumstantial factors like seating arrangements or student preference, for the most part. Yet, some added that they would vary the type of social interaction as well as group composition in order for students with different talents or weaknesses to collaborate. T8, for example, organises the learners in mixed-language-ability groups when doing CLIL tasks.

RQ5: To what extent is CLIL more learner oriented?

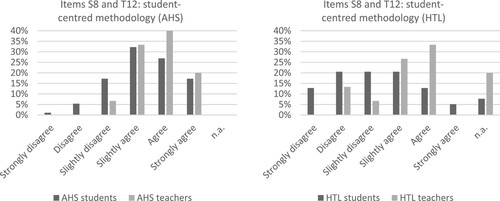

The AHS participants, teachers (93.3%) more so than students (76.4%), agreed that their CLIL lessons were learner-centred. Similarly, the HTL teachers (60%) were more optimistic about learner orientation than their students; here, just a third of the students (33.3%) agreed that they were given space for independent work in class ().

The interview data reflect these figures for the most part. The AHS interviewees appeared more convinced that their CLIL lessons were learner-centred than the HTL ones. Especially the AHS students in the focus groups strongly felt that their CLIL classes were very learner-oriented, more so than in the survey. They reported that they were more active in CLIL than in regular classes, mostly due to the more frequent use of action-based worksheets. Following the students’ accounts, worksheets also seem to go hand-in-hand with group-work mode and project-based learning (e.g. conducting experiments in chemistry). They said that they appreciated taking their own notes and working independently while also acknowledging their own responsibility for their learning. This way, they would ‘remember everything much more easily’ and ‘learn much more intensely, even the little details’ (AHS2_g8_S).

The majority of the AHS teachers, too, described their CLIL lessons as learner-centred and interactive in the interviews, mentioning gamification, task-based learning, competency-based learning or multimodality. Some even felt that this was the best part about their CLIL teaching, appreciating the collaborative and ‘hands-on’ nature of CLIL tasks. However, not all teachers agreed, but not for obvious reasons. In fact, the interviewees seemed to have different conceptualisations of what labels like student-centredness or teacher-centredness or teacher-guided would entail. For example, the chemistry and maths teachers (T1 + T2 respectively) considered their teaching to be teacher-centred, although the way the lessons were described painted a learner-centred and active picture, and the learners, too, reported that they experienced these lessons as learner-oriented and engaging. In the case of chemistry, the teacher stated that many experiments were conducted by students but since she would be the one ‘calling the shots’, i.e. giving instructions during experiments, T2 felt that her teaching was centred on the teacher.

In the HTL context, the teachers described their CLIL lessons as mostly learner-oriented as well. They reported that they usually adopted the role of the coach, with ‘students having to work while I’m guiding them through’ (T8). In guiding learners, one of the HTL teachers added that they paid particular attention to quiet and struggling students. The HTL students, however, did not seem to perceive their CLIL lessons as more learner-centred than their regular classes, reporting a mix of teacher- and learner-centredness, as argued by this student: ‘Most teachers just do their normal teaching in English instead of German but don't change anything else. But CLIL should be connected to group work so that you could try out English’ (HTL_g11_B_S). Echoing the results of the survey, these students would appreciate more hands-on tasks and group work especially in CLIL. From their point of view, CLIL should ideally involve more opportunities for independent work and peer interaction.

5. Discussion

Although our data set is limited in various ways – it is based on convenience sampling and consists exclusively of reported data – the results have underlined its strong exploratory nature. As the first study to address diversity in Austrian CLIL practices, its findings offer initial depictions of how teachers and students perceive and deal with the range of skills in CLIL lessons. While the two CLIL formats in focus here, referred to as DLP and ‘CLIL for HTL’, are certainly not representative of all CLIL in Austria, they are well established and long-standing programmes whose differences in age levels (lower vs. upper secondary levels), regional spread (Vienna vs. Austria) and student groups involved (selected groups vs. all students of a school type) offer results that gain in depth and robustness because they can be compared and contrasted with one another. Such a triangulation of findings is at the core of the following summative answers this study provides to the five research questions:

RQ1: How do participants see diversity?

RQ2: How do teachers support students during CLIL lessons?

RQ3: To what extent is German used as support for weaker students?

RQ4: How do students support one another?

RQ5: To what extent is CLIL more learner-oriented?

When compared with previous studies, these results reconfirm, firstly, that a structured approach to CLIL is generally met with appreciation (see Hüttner, Dalton-Puffer, and Smit Citation2013; Döring Citation2020). Teachers have no trouble describing and arguing for their pedagogically motivated CLIL practices and students of both age groups involved express their appreciation of, or wish for, regularity and continuity of doing CLIL, preferably in a student-centred way aiming for project-based and collaborative learning (see Bauer-Marschallinger Citation2019, Citation2020). Secondly, this study reiterates the generally shared view in Austrian CLIL classes that it is a bilingual educational experience that profits from a principled use of both English and German (see Dalton-Puffer Citation2007; Gierlinger Citation2015; Smit and Finker Citation2018).

At the same time, the findings reveal how differently teachers and students seem to evaluate their shared CLIL practices. Looking at the use of peer support and group work, for instance, the teachers report planning collaborative activities in a pedagogically purposeful way in order to balance out different abilities, strengths and weaknesses while their students do not seem to be aware of this. In contrast to the findings in Hüttner, Dalton-Puffer, and Smit (Citation2013) and Döring (Citation2020), the HTL students reported few such activities and wished for more opportunities for peer support. Furthermore, the teachers’ rationale behind using the L1 does not always seem entirely clear to the learners, who would appreciate more transparency in L1 use, particularly for explaining and learning complex topics. Yet, the teachers in our study are convinced they use the L1 purposefully, similar to the results reported in Gierlinger (Citation2015).

These results point towards the fact that the teachers in our study are not very explicit and transparent in their pedagogical practices. In other words, their pedagogical practices are invisible to learners, who thus miss out on the chance to take control of their own learning (see Bernstein’s [Citation1975] notion of invisible vs. visible pedagogy). However, when it comes to scaffolding language, the picture is somewhat reversed since students feel supported whereas teachers report not providing any linguistic support. This might have to do with the teachers’ understanding of their own role during CLIL, namely that of a content teacher rather than a language teacher (see Bauer-Marschallinger Citation2019; Dalton-Puffer Citation2007; Gierlinger Citation2017). Yet, these teachers appear to reformulate and translate passages, unpacking dense content and challenging disciplinary language in order to ensure student comprehension, without being aware of doing so. Obviously, without awareness, teachers cannot be explicit in their scaffolding, i.e. when modelling subject-specific thinking processes and strategies, a result matching the findings by Mahan (Citation2020). Ultimately, in diverse educational settings in particular, explicit scaffolding might be key to helping learners construct subject-specific knowledge themselves.

Another noticeable difference between teacher and student evaluations concerns the degree of student-centredness enacted in CLIL lessons. The AHS participants agree on this account but the HTL students reveal a very different experience from their teachers. While this stark difference might be a reflection of the small HTL database of interviews, including only two teachers and two student groups, who, additionally, had little CLIL experience at the time, it is interesting when combined with the very limited, not to say absent CLIL teacher education available, particularly for HTL technical teachers. In contrast to the Dutch teachers reported on in de Graaff, Koopman, and Westhoff (Citation2007) or van Kampen, Admiraal, and Berry (Citation2018), HTL teachers, employed for their technical expertise, can draw on very little teacher education background in general, and even less so when it comes to doing CLIL. While some in-service training is organised in some provinces, it is mostly on an ad-hoc basis rather than culminating in an additional qualification. Although our database is certainly too small to draw any far-reaching conclusions, this chasm between teacher and student views on student-centredness could indicate a need for more CLIL-focused teacher professional development in some HTLs.

Although the present study is limited by its small sample size, we suggest that a general insight which can be derived from it lies in the importance of explicitness: for teachers to make their pedagogies visible to the students and for teachers and learners to enter into conversations about their own perceptions of classroom realities, be it with regard to degrees of student-centredness or with regard to teachers’ spontaneous scaffolding reactions when students struggle with language. More research into all these aspects is definitely desirable, as is work on teacher development for CLIL educational practices that make the diversity challenge manageable.

Finally and arguably most importantly within the ADiBE project, this study has unveiled a rather complex understanding of ‘diversity in CLIL’ amongst our participants. Reflecting the educational system that intends to reduce diversity through splitting up learners at two points, all learner groups insisted on their being equal in academic abilities. Such an equality ethos is structurally entrenched in the relevant legislation that explicitly rules out the grading of students based on differently demanding tasks. This, however, is not actually mirrored in the pedagogical practices teachers seem to enact in class. Both teachers and students report on student-sensitive support being offered by teachers and sometimes also by other students. In other words, different academic skills or learning speeds are acknowledged and responded to in class, albeit in an incidental and pedagogically invisible manner. Such in-class practices seem to be conceptualised independently of the (written) teaching materials used to support learning. This interpretation of what diversity in academic skills encompasses seems to restrict differences in academic skills to ad hoc reactions to learner needs in class, while at the same time uncoupling it from visible pedagogy and a systematic, long-term strategy for dealing with learner diversity, in keeping with the widespread ideology of segregationism and egalitarianism in Austrian education. In view of the exploratory nature of our study, we cannot claim that such a restricted understanding of ‘diversity’ is at the heart of Austrian CLIL more generally but, given its wide impact on pedagogical decisions, it certainly warrants more research into the extent to which CLIL in Austria really is for all.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Silvia Bauer-Marschallinger

Silvia Bauer-Marschallinger is a lecturer in English language teaching at the KPH Vienna/Krems and the University of Vienna, Austria, training pre-service primary and secondary teachers. Currently working on the completion of her doctoral studies, her research interests include CLIL, language teaching and learning, and language-aware history didactics.

Christiane Dalton-Puffer

Christiane Dalton-Puffer is professor in English linguistics at the University of Vienna, Austria. Her research interests are in CLIL, classroom interaction, and the intertwining of language and content in formal education. She co-edits a book series on multilingual learning.

Helen Heaney

Helen Heaney is a senior lecturer at the University of Vienna, Austria involved in the teacher education, linguistics and language competence strands. Her special interests are in CLIL, language testing and assessment, innovative approaches to language teaching and learning, and reading comprehension.

Lena Katzinger

Lena Katzinger is a research assistant at the English Department, currently completing her MEd in teaching English and Czech as a foreign language.

Ute Smit

Ute Smit is professor of English Linguistics at the University of Vienna, Austria. Her applied linguistic research focuses mainly on English in, and around, education. Besides involvement in various international research projects, Ute is a board member of ICLHE (Integrating Content and Language in Higher Education).

Notes

1 All quotes were translated by the authors.

References

- Badertscher, H., and T. Bieri. 2009. Wissenserwerb im Content-and-Language Integrated Learning. Bern: Haupt Verlag.

- Ball, P., K. Kelly, and J. Clegg. 2015. Putting CLIL into Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Banegas, D. L. 2017. “Teacher-Developed Materials for CLIL: Frameworks, Sources, and Activities.” Asian EFL Journal 19 (3): 31–48.

- Bauer-Marschallinger, S. 2019. “With United Forces: How Design-Based Research Can Link Theory and Practice in the Transdisciplinary Sphere of CLIL.” CLIL Journal 2 (2): 7–23. doi:10.5565/rev/clil.19.

- Bauer-Marschallinger, S. 2020. “Involving Students in Educational Design: How Student Voices Contribute to Shaping Transdisciplinary CLIL History Materials.” Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning 2 (2): 107–117. http://jpll.org/index.php/journal/article/view/29.

- Bernstein, B. 1975. Class Codes and Control: Theoretical Studies Towards a Sociology of Language. vol. 3. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Biewer, G., M. Proyer, and G. Kremsner. 2019. Inklusive Schule und Vielfalt. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag.

- BMB (Federal Ministry of Education). 2011. Allgemeines Bildungsziel, schulautonome Lehrplanbestimmungen, didaktische Grundsätze und gemeinsame Unterrichtsgegenstände an den Höheren Technischen und Gewerblichen (einschließlich Kunstgewerblichen) Lehranstalten. BGBl_II_Nr_300_2011: Anlage 1. www.ris.bka.gv.at.

- BMBWF (Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research). 2018. Austrian Educational System. www.bmbwf.gv.at/dam/jcr%3A652bbca0-b5a9-4bd8-a283-f969149d2486/bildungssystemgrafik_2018e.pdf.

- Dalton-Puffer, C. 2007. Discourse in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Classrooms. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Dalton-Puffer, C., S. Bauer-Marschallinger, K. Brückl-Mackey, V. Hofmann, J. Hopf, L. Kröss, and L. Lechner. 2018. “Cognitive Discourse Functions in Austrian CLIL Lessons: Towards an Empirical Validation of the CDF Construct.” European Journal of Applied Linguistics 6 (1): 5–29. doi:10.1515/eujal-2017-0028.

- Dalton-Puffer, C., J. Hüttner, V. Schindlegger, and U. Smit. 2009. “Technology-Geeks Speak Out: What Students Think About Vocational CLIL.” International CLIL Research Journal 1 (2): 1–25.

- Dalton-Puffer, C., T. Nikula, and U. Smit. 2010. “Language Use and Language Learning in CLIL: Current Findings and Contentious Issues.” In Language Use and Language Learning in CLIL Classrooms, edited by C. Dalton-Puffer, T. Nikula, and U. Smit, 279–291. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- de Graaff, R., G. J. Koopman, and G. Westhoff. 2007. “Identifying Effective L2 Pedagogy in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL).” VIEWS: Vienna English Working Papers 16 (3): 12–19. http://anglistik.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/dep_anglist/weitere_Uploads/Views/Views_0703.pdf.

- Döring, V. 2020. “Student Voices on CLIL: Suggestions for Improving Compulsory CLIL Education in Austrian Technical Colleges (HTL).” CELT Matters 4: 1–11.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2007. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Feyerer, E. 2019. “Kann Inklusion unter den Strukturen des segregativen Schulsystems in Österreich gelingen?” In Ist inklusive Schule möglich? Nationale und internationale Perspektiven, edited by E. Feyerer, J. Donlic, E. Jaksche-Hoffman, and H. K. Peterlini, 61–76. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Gierlinger, E. 2015. “‘You Can Speak German, Sir’: On the Complexity of Teachers’ L1 Use in CLIL.” Language and Education 29 (4): 347–368. doi:10.1080/09500782.2015.1023733.

- Gierlinger, E. M. 2017. “I Feel Traumatized: Teachers’ Beliefs on the Roles of Languages and Learning in CLIL.” In Integrating Content and Language in Higher Education: Perspectives on Professional Practice. Selected Papers from the IV International Conference Integrating Content and Language in Higher Education 2015, edited by J. Valcke, and R. Wilkinson, 97–116. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Hüttner, J., C. Dalton-Puffer, and U. Smit. 2013. “The Power of Beliefs: Lay Theories and their Influence on the Implementation of CLIL Programmes.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16 (3): 267–284. doi:10.1080/13670050.2013.777385.

- Hüttner, J., and U. Smit. 2018. “Negotiating Political Positions: Subject-Specific Oral Language Use in CLIL Classrooms.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (3): 287–302. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1386616.

- Lialikhova, D. 2019. “‘We Can Do It Together!’ – But Can They? How Norwegian Ninth Graders Co-constructed Content and Language Knowledge Through Peer Interaction in CLIL.” Linguistics and Education 54: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2019.100764.

- Madrid, D., and M. L. Pérez Cañado. 2018. “Innovations and Challenges in Attending to Diversity Through CLIL.” Theory into Practice 57 (3): 241–249. doi:10.1080/00405841.2018.1492237.

- Mahan, K. R. 2020. “The Comprehending Teacher: Scaffolding in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL).” The Language Learning Journal 18 (4): 1–15. doi:10.1080/09571736.2019.1705879.

- Mahan, K. R., L. M. Brevik, and M. Ødegaard. 2021. “Characterizing CLIL Teaching: New Insights from a Lower Secondary Classroom.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24 (3): 401–418. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1472206.

- Mehisto, P., D. Marsh, and M. J. Frigols. 2009. Uncovering CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning in Bilingual and Multilingual Education (reprint). München: Macmillan and Hueber (Macmillan books for teachers).

- Meyer, O. 2013. “Introducing the CLIL-Pyramid: Key Strategies and Principles for CLIL Planning and Teaching.” In Basic Issues in EFL Teaching and Learning, 2nd ed., edited by M. Eisenmann, 295–313. Heidelberg: Winter (Anglistische Forschungen, Bd. 420).

- Moore, P., and F. Lorenzo. 2015. “Task-based Learning and Content and Language Integrated Learning Materials Design: Process and Product.” The Language Learning Journal 43 (3): 334–357. doi:10.1080/09571736.2015.1053282.

- Nagel, T., A. Schad, B. Semmler, and M. Wimmer. 2012. “Austria.” In Language Rich Europe: Trends in Policies and Practices for Multilingualism in Europe, edited by G. Extra, and K. Yağmur, 83–90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2017). Education Policy Outlook: Austria. www.oecd.org/education/Education-Policy-Outlook-Country-Profile-Austria.pdf

- Pérez Cañado, M. L., D. Rascón Moreno, and V. Cueva López. 2021. “Identifying difficulties and best practices in catering to diversity in CLIL: instrument design and validation.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13670050.2021.1988050.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. this issue. “Guest Editorial.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Submitted.

- Roussel, S., D. Joulia, A. Tricot, and J. Sweller. 2017. “Learning Subject Content Through a Foreign Language Should Not Ignore Human Cognitive Architecture: A Cognitive Load Theory Approach.” Learning and Instruction 52: 69–79. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.04.007.

- Smit, U., and T. Finker. 2018. “CLIL in Austrian Technical Colleges (HTL): An Analysis of Classroom Practices Based on Systematic Video-Based Lesson Observations.” In Formen der Mehrsprachigkeit. Sprachen und Varietäten in sekundären und tertiären Bildungskontexten. With assistance of Philip C. Vergeiner, edited by M. Dannerer, and P. Mauser, 229–246. Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag (Stauffenburg Linguistik, Band 102).

- Statistik Austria. 2019. Schülerinnen und Schüler mit nicht-deutscher Umgangssprache im Schuljahr 2018/19. https://www.statistik.at/wcm/idc/idcplg?IdcService=GET_PDF_FILE&RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased&dDocName=029650.

- van Kampen, E., W. Admiraal, and A. Berry. 2018. “Content and Language Integrated Learning in the Netherlands: Teachers’ Self-Reported Pedagogical Practices.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (2): 222–236. doi:10.1080/13670050.2016.1154004.

- Vienna Board of Education. 2016. Modern Language Initiatives. http://www.schulentwicklung.at/joomla/images/stories/Sprachinitiativen/Fremdsprachenmodell_SJ_16_17.pdf.