ABSTRACT

This paper reports on the outcomes of a study on stakeholder perspectives on catering for diversity in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Spain. It is part of the large-scale SWOT analysis conducted in Europe within the project ‘CLIL for All: Attention to Diversity in Bilingual Education (ADiBE)’. The research has involved the administration of two sets of questionnaires to 926 informants (742 students and 184 teachers) within 15 secondary schools of four provinces. After framing the topic against the backdrop of the project, the paper will expound on the objectives, methodology, variables, and procedure employed in this particular study in Spain. The bulk of the article will outline its main findings in relation to the five main fields of interest which have been canvassed: linguistic aspects, methodology and types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher coordination and development. Across-group comparisons will be carried out to determine whether there are statistically significant differences between both cohorts. A diagnosis of where we currently stand in Spain in the process of catering for diversity in CLIL will be provided in light of these results and a future CLIL agenda will be carved out on the basis of these findings.

1. Introduction

This paper is aimed at focusing on the results drawn from a study on the perspectives which different stakeholders involved in the implementation of CLIL in a sample of high schools in Spain have on the topic of catering for diversity. Even though attention will now be paid to both students and teachers, parents’ opinions have also been polled and they will be analyzed in subsequent research (cf. final article in this issue). From our point of view, it is crucial to consider the perspectives of all the stakeholders involved in the implementation of CLIL programs in order to get an updated and comprehensive picture of what the current situation is concerning CLIL implementation with regard to attention to diversity. This statement is in line with Barrios Espinosa (Citation2019, 1), who highlights that one of the reasons why stakeholders’ viewpoints should be considered is the following: ‘the interest […] lies in the fact that their interpretations and beliefs are crucial to understand how the CLIL program is socially viewed, understood and constructed, and the expectations it raises’.

This article stems from the Erasmus+ KA201 ‘CLIL for All: Attention to Diversity in Bilingual Education’ (ADiBE) project, funded by the European Commission.Footnote1 In order to obtain data regarding attention to diversity in bilingual education (henceforth BE), there is a number of different lines of action derived from ADiBE, including the design, validation, and application of questionnaires in different European schools.

Particularly, this paper describes a representative sample of 926 informants in Spanish institutions as regards five fields of interest: linguistic aspects, methodology and types of groupings, materials and resources, assessment, and teacher coordination and development. Data has been gathered and will permit us to make a diagnosis of the way attention to diversity is catered for in CLIL, bearing in mind the students’ and teachers’ viewpoints.

After focusing on the prior research into the topic under study, the different objectives will be specified, the methodology will be described (including research design, sample, variables, instruments, procedure, and statistical methodology), and both global and specific results will be discussed. Finally, the main conclusions that can be drawn as a result of this study will be expounded on.

2. Prior research

Although BE has only been officially implemented in Spanish schools in the last few years, studies into aspects such as attention to diversity are still scarce, ‘at an embryonic stage’ (Madrid Fernández and Pérez Cañado Citation2018, 242), or ‘very much in their infancy’ (op.cit.: 246). While different aspects such as its assessment, characterization, definition, evolution, implementation, or success have been more or less deeply studied so far, there are issues, such as the one under study, that still represent a niche that requires further research.

More specifically, with regard to the research already carried out, a distinction can be drawn between theoretical, qualitative, and quantitative accounts, as suggested by Madrid Fernández and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018, 242–244) in the second section of their paper (cf. also Pérez Cañado Citationin this issue a, for an overview).

In the third group there are references to different types of variability that may play a relevant part in CLIL. Such is the case of ‘varying linguistic levels in English as a second language’, ‘socioeconomic status’ (henceforth, SES) usually taking parents’ educational level as a proxy, ‘social milieu’, and ‘type of school’.Footnote2

Although ‘segregation’, defined by Rundell (Citation2021, 3) as ‘the policy of keeping people from different groups, especially different races, separate’, and originally considered as the opposite of ‘integration’ (meaning ‘the policy of bringing these groups together’), conveyed a general meaning, it can now be found in some publications referring to the fact that the access to BE is elitist and, therefore, fosters segregation. That is the case of Bruton (Citation2013) and Gortázar and Taberner (Citation2020, 219), among others. As far as secondary education is concerned, the latter state that ‘School segregation by socioeconomic characteristics in secondary education in the Autonomous Community of Madrid is the highest in Spain and second highest amongst OECD countries’.

However, the Spanish Association for Bilingual Education (Asociación Enseñanza Bilingüe Citation2020, 1), in their reply to the aforementioned paper, specify that access to the program is open for all public schools in the region and in the same conditions established in previous calls, regardless of the students’ SES.Footnote3 In addition, in their study, Madrid Fernández and Barrios Espinosa (Citation2018) arrive at the conclusion that neither SES nor other features can account for differences between CLIL and non-CLIL groups.Footnote4

Moreover, Barrios Espinosa (Citation2019, 5) underlines the role played by BE as an instrument of social cohesion due to the fact that ‘it is aimed to facilitate the whole population access to quality education in foreign languages that was formerly the prerogative of the elite’.

Liasidou (Citation2013) provides information about the intersection between English language learning and special educational needs (henceforth, SEN). Thus, students in bilingual programs may have to cope not only with their needs related to disability, but also with the linguistic ones.Footnote5

Coordination plays a key role for the learning-teaching process to be successful, particularly in these educational contexts: ‘In this sense, it is acknowledged that meeting students’ diverse needs entails a systemic and interdisciplinary approach in order to address effectively and efficiently their full continuum of needs’ (op.cit.: 11). Therefore, all the stakeholders involved in BE should work as a team.

Needless to say, the students’ academic achievement will necessarily be affected by their ‘diversity, their special needs and interests, multiple intelligences and cognitive styles’ (Madrid Fernández and Barrios Espinosa Citation2018, 30).

After dealing with some general ideas on the relationship between BE and attention to diversity (as well as inclusion), matters such as what the situation is like both in the United States and in Europe will be tackled, then delving into the specific case of Spain.

With regard to the current situation in the United States, a distinction can be drawn between the approaches that cultivate bilingualism (e.g. dual immersion) and the ones minimizing it (e.g. pull-out). Scanlan (Citation2011) focuses on one of the groups of students that are traditionally marginalized (namely, the ones in linguistically diverse families) and on the so-called ‘segregation by language’. Providing them with appropriate educational services can be regarded as another challenge and the growth of this group is impressive (Scanlan Citation2011, 5).

In line with this, Somers (Citation2017) focuses on inclusion in CLIL programs of immigrant minority language students, a term he uses to refer to ‘children with an immigration background, either as newly arrived immigrants or descendants of immigrants, whose home language(s) is/are neither the ambient majority language (or any other official language) nor the additional language of instruction in their CLIL programme’ (op.cit.: 499). This is another issue that should receive more attention in research. These students tend to succeed in the development of multilingualismsince, apart from their mother tongue, they are taught in a second and a third language thanks to CLIL (Somers Citation2017, 514).

Among the strategies proposed by Scanlan (Citation2011, 7) in his conceptual framework proposal, it can be mentioned that he foregrounds that ‘[…] support services for bilingual students must be integrated into the broader service delivery system in the school’ and that school leaders should consider, among others, both ‘in-school supports for bilingual students and home-school collaboration strategies for bilingual families’.

In turn, Cioè-Peña (Citation2017, 907) underscores that these bilingual special education students ‘are often passed over and continually left on the margins of inclusive classrooms, schools and society, leaving them in what can be considered an intersectional gap’. In her literature review, Cioè-Peña (Citation2017, 907) mentions some of the legislation in this country, including the Bilingual Education Act (BEA, Citation1968), No Child Left Behind (NCLB, Citation2001), and the Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; Castle Citation2004), among others.

As far as the European context is concerned, the different papers in this special issue provide more information regarding specific countries such as Austria (Bauer-Marschallinger et al. Citationin this issue), Finland (Nikula et al. Citationunder review), Germany (Siepmann et al. Citationin this issue), Italy (Ting Citationunder review), and the United Kingdom (Coyle et al. Citationin this issue). Finally, the last paper presents a cross-European perspective (Pérez Cañado Citationin this issue b).

As for Spain, in some cases, both segregation and attention to diversity issues are sometimes closely associated with the establishment of different admission criteria in the various regions. The reason for this is that, although there are specific legal documents dealing with these topics published by the central government, the regions in Spain are (to a certain extent) in charge of certain education matters, including not only attention to diversity, but also CLIL, among many others.

Due to the fact that during the early stages of CLIL implementation in Spain the resources available were limited, decisions had to be taken concerning what students would benefit from CLIL and what would receive the traditional non-CLIL teaching. Thus, CLIL was not mainstream in public education.

Therefore, this was one of the main concerns since this involves not only a lack of egalitarianism already pinpointed by scholars such as Bruton (Citation2013, Citation2015) or Paran (Citation2013), but also some ‘prejudice and discrimination against non-CLIL learners’ (Madrid Fernández and Pérez Cañado Citation2018, 242). In fact, it may be even perceived that ‘[…] bilingualism is a program for gifted students and thus too challenging for children with dis/abilities’ (Kremer-Sadlik Citation2005; Marinova-Todd et al. Citation2016; in Cioè-Peña Citation2017, 908).

In addition, Durán-Martínez, Martín-Pastor, and Martínez-Abad (Citation2020) as well as Durán-Martínez (Citation2021) highlight the two main challenges currently faced by the educational system in this country, as stated by the latter: ‘an inclusive approach to education and fostering bilingual programs within mainstream education’. The former highlight among the main results of their research the fact that some students with SEN end up quitting BE throughout the academic year, receive more support in Primary Education (PE) than in Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE), and that the main reason for this is the students’ difficulties.Footnote6 In the case of PE, Martín-Pastor and Durán Martínez (Citation2019) underline that nearly half of the 160 schools analyzed in their research do not even mention attention to diversity in their bilingual projects.

Unfortunately, the research conducted by Pérez Cañado (Citation2018, 27) also reaches the conclusion that there is still room for improvement in this front in both PE and CSE and, therefore, ‘[…] resources, materials, guidelines, and clear-cut lines of action should be set in place to ensure that CLIL is working adequately for all types of achievers, particularly now that we are moving from bilingual sections to bilingual schools’.

In line with the ideas above, Madrid Fernández and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018, 245–246) compile some of the lines of action that can be utilized in order to facilitate both inclusion and attention to diversity bearing in mind not only current legislation, but also the guidelines in Spain and Europe, as well as specialists’ proposals and teaching staff’s strategies.

3. Objectives

This paper is aimed at outlining the outcomes of a study on student and teacher perspectives on catering for diversity in CLIL in Spain, and at determining the existence of across-group differences between both cohorts. Attention to diversity in the approach from linguistic, methodological, and organizational angles is here described.

This general objective can be divided into two key metaconcerns which prove essential for this research project and consist of six component corollaries:

Metaconcern 1 (Identification of CLIL student and teacher perspectives on catering for diversity)

To identify stakeholder perspectives vis-à-vis linguistic aspects.

To identify stakeholder perspectives concerning methodology and types of groupings.

To identify stakeholder perspectives in relation to materials and resources.

To identify stakeholder perspectives as regards assessment.

To identify stakeholder perspectives pertaining to teacher coordination and organization.

Metaconcern 2 (Across-cohort comparison)

In turn, the second main objective intends to determine whether there are any statistically significant differences between the perspectives of the two cohorts: students and teachers.

4. Method

4.1. Research design

This paper reports on findings of the ADiBE project relating to its first objective/output: to identify difficulties and best practices in catering to diversity in intercultural and content integrated language learning and teaching. It shows the opinions gathered from students and teachers in Spanish schools. This investigation is an instance of primary research, and within it, of survey research, as it includes questionnaires and interviews.

This study can be claimed to have multiple triangulation as another of its features, since three types of triangulation have been followed:

Data triangulation, given that, both questionnaires and interview protocols were employed with students and teachers (and that involves, within them, not only foreign language (FL) and non-linguistic area (NLA) teachers, but also teaching assistants (TAs)).

Investigator triangulation, since, for each province, different members of the research team administered the questionnaires and conducted the interviews.

Location triangulation, due to the fact that data have been collected from several provinces and regions.

4.2. Sample

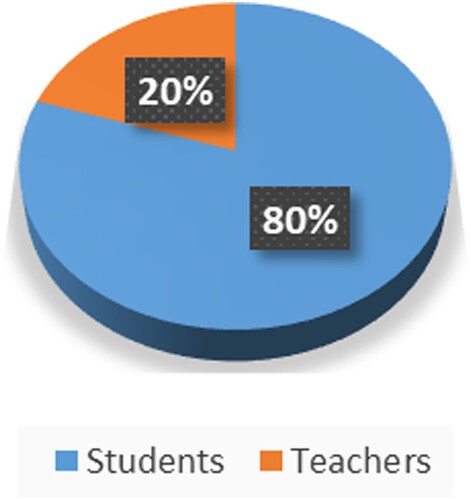

The Spanish sample is comprised of 742 students and 184 teachers, that is to say, of 926 informants in total. They belong to 15 bilingual secondary schools of Córdoba (seven), Granada (two), Jaén (four), and Zaragoza (two). The first three are provinces of Andalusia and the last one is a province of Aragón. A Spanish institution based in Morocco was also involved. In contemplating the number of participants who have completed the questionnaires, it is discernible that a larger percentage of students have taken part in comparison to teachers (80% as against 20%) (cf. ). The vast majority of them (75%) are in the third or fourth year of CSE.

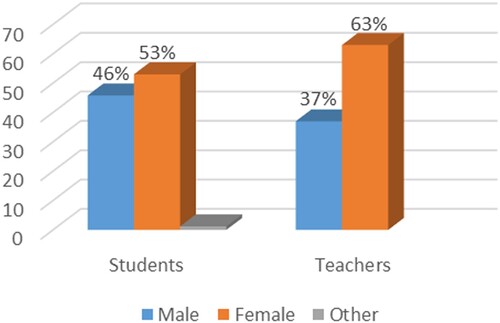

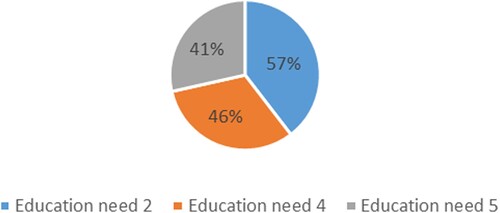

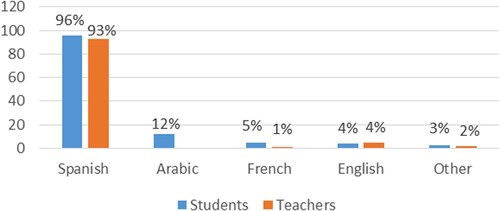

With regard to gender, a relatively similar amount of male (46%) and female (53%) students have taken part in the study, whereas teachers display a higher percentage of female (63%) than male (37%) participants (cf. ). Taking into consideration the principal language of the informants, Spanish is clearly the predominant one. It is interesting to note, on the one hand, that an additional language is spoken at the homes of over 20% of learners, the main ones being Arabic to a greater extent, and French and English to a lesser extent; and, on the other hand, that English is the mother tongue of 4% of practitioners (cf. ).

Figure 3. Breakdown of the overall sample in relation to language(s) spoken at home (students) or mother tongue (teachers).

4.2.1. Students

Examining each group separately, beginning with students, we find that most of them are learners aged 14 and 15 (the former, 22% and the latter, 41%). Around a fifth are younger (21%) and the rest are 16–19 (slightly over 14%). They have been enrolled in a bilingual program for either less than three years (39%) or since the start of Primary Education (45%). A minority of them have experienced bilingual education also as preschoolers (16%). When asked to name the subjects taught through English, the following answers were provided: Biology and Geology (60%), Music (55%), Geography and History (42%), Physical Education (38%), Mathematics (34%), Physics and Chemistry (31%), Art (22%), Citizenship and Human Rights Education (18%), Economy (13%), and Technology (9%).

The last identification question had to do with the percentage of each of those subjects that they estimated was taught in the FL. If they are ordered according to 80% or higher amount of class time with exposure to English, the ranking is as follows: Music (73%), Art (49%), Physical Education (45%), History and Geography (36%), Biology and Geology (35%), Physics and Chemistry (27%), Citizenship and Human Rights Education (21%), Mathematics (21%), Economy (18%) and Technology (9%).

4.2.2. Teachers

The identification variables at the start of the teacher questionnaire also allow for a precise depiction of this cohort. There is a predominance of teachers in the age group 41–59 (61%), the remaining being younger (39%). More than half of them are NLA teachers (57%), over a third are FL teachers (36%), and a small number of them are TAs (4%). The rest of practitioners (3%) consider themselves none of the above categories. The variety of subjects taught by NLA teachers tallies with the data from students. However, the amount of class time of each subject instructed through English is dissimilar for both groups. For teachers it is usually higher, but not always. The participating teachers of Art, Music, and Physical Education acknowledge less exposure to English in their lessons.

The majority of respondents are civil servants who are teaching in their allocated destination (64%), have an adequate level of English, i.e. B2 or higher (88%), and are not the bilingual coordinator at the school (87%). Regarding overall teaching experience, most teachers have been teaching between 11 and 20 years (44%), many have been teaching for less than ten years (28%), and a minority of them have devoted to the profession more than 21 years (28%). To conclude, when exploring bilingual teaching experience, it emerges that they have not usually been involved in a program of this type for more than five years (62%), although there is an important number of them (38%) that have already gained experience in bilingual teaching for over five years.

4.3. Variables

The study integrates sets of identification (subject) variables for the two distinct participants. They are similar, albeit more numerous for teachers. The variables for students are: grade, age, gender, language(s) spoken at home, years studied in a bilingual program, subjects studied in English, and exposure to English within school. Those of the other cohort, teachers, collaborating in the questionnaire are: grade, age, gender, mother tongue, type of teacher, employment situation, English level, subjects taught in English, percentage of subject taught in English, bilingual coordinator, overall teaching experience, and bilingual teaching experience.

4.4. Instruments

The opinions shown in this paper have been gathered by means of the survey tool for students and a similar one for teachers which were jointly created in English by the European ADiBE project members. No further modification was made to them apart from their mere translation into Spanish. Thus, it can also be claimed about these versions that they are qualitative and quantitative instruments whose design has been based on recent research outcomes and that they have undergone the rigorous design and validation process detailed in Pérez Cañado, Rascón Moreno, and Cueva López (Citationin this issue). The students’ questionnaire was group-administered, whereas the teacher’s tool was self- and group-administered. The other instruments that have been used for this study are the also original interview protocols. Thanks to them information could be obtained to complement the data collected through the questionnaires and, consequently, a complete picture of how attention to diversity in CLIL is functioning in Spain can be drawn. These four tools can be found in their original English versions annexed to the aforementioned paper.

4.5. Procedure

The questionnaires were administered online or in printed format to the whole bilingual class and participating teachers. To fill in the versions set up on Survey Monkey, computers or mobile phones were used. The researchers did the survey with the students, reading each item aloud and explaining it to ensure understanding. Teachers either filled them in online or in printed format, preferably on the day of our visit to the school, after an initial introduction was made to present the project, clarify key concepts, and give precise instructions for their completion. Around 25 min were enough for students and ten for teachers to complete the surveys.

For the interviews, researchers, with the help of the teacher, selected a sample of ten students of various language ability levels and genders from each bilingual class. They were interviewed after the administration of the questionnaire, during tutoring hours, during recess, or at any other time that the school considered appropriate. With the teachers involved in the bilingual program the focus group interview was conducted at a time when (almost) everyone was available. If prior consent was given, it was recorded. Simultaneously, the researcher(s) took notes, on the interview protocol, of the main ideas that emerged. Around 30 min were necessary, sometimes a few more in the case of interviews with teachers.

4.6. Statistical methodology

The data collected have been analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program in its 22.0 version. For Metaconcern 1, descriptive statistics have been used. Therefore, both central tendency and dispersion measures have been calculated. In turn, for Metaconcern 2 the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test has been employed with the aim of unearthing the existence of statistically significant differences in each of the blocks between the two stakeholders. Together with it, the effect size has also been obtained through Rosenthal’s R. For the semi-structured interviews, Grounded Theory analysis (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967) has served as the framework of reference for categorizing, synthesizing, and identifying emerging patterns in the open-response data.

5. Results and discussion

First, the perspectives on catering for diversity in CLIL will be identified (Metaconcern 1) by means of a close inspection of each individual cohort. The principal tendencies discovered will be alluded to and any salient exceptions will be pointed out. Second, a comparison between the results obtained from the two stakeholders, students and teachers, will be made (Metaconcern 2). It should be noted that, as the questionnaires use a 1–6 point Likert scale (see Pérez Cañado, Rascón Moreno, and Cueva López Citationin this issue), answers will be considered to be agreeing with the statements made when yielding a mean higher than 4, to a lesser extent, and over 5, to a greater extent.

5.1. Global results

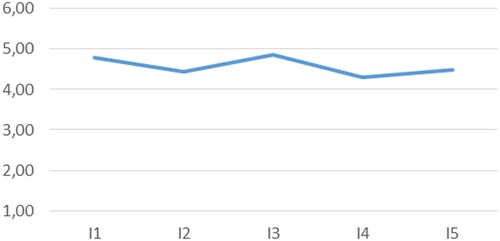

The student participants believe that they receive scaffolding in class (items 1 and 2), especially of linguistic type, and that their teachers repeat parts of a lesson in their first language more often than not (item 3) to help them understand the content they are learning. They just slightly agree, though, when asked whether practitioners’ communication skills in the FL (item 4) and practitioners’ specialized knowledge of the subject (item 5) help learners with different abilities (cf. ).

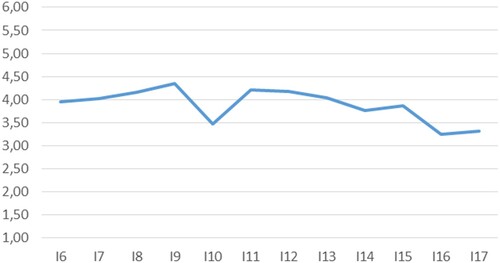

Concerning methodology and types of groupings, results are relatively homogenous. Learners partially agree with nine of the twelve statements of this block, which enquire about: lessons being sensitive to students with different abilities (item 6), the teacher having an adequate repertoire of methods to help them (item 7), student-centered work (item 8), cooperative learning (item 9), task-/project-based classroom work (item 11), teacher-led work (item 12), different types of groupings (item 13), personalized attention (item 14), and use of peer mentoring and assistance strategies to help different types of learners (item 15). Contrarily, they slightly disagree that multiple intelligences are used (item 10) and classroom layouts are varied to meet the needs of different types of learners (item 16), and that they have newcomer classes to support the integration of learners into CLIL (item 17) (cf. ).

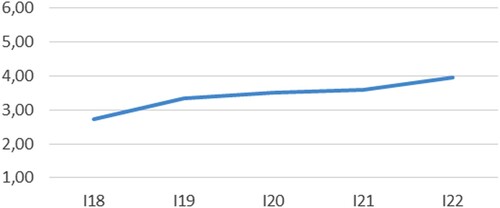

The learners’ impressions of materials and resources show mixed responses. While students slightly disagree that they are exposed to materials which take into account their different levels of ability, be they textbooks (item 18), adapted materials (item 19), or materials created by the teacher (revealing fully mixed responses, item 20), results are slightly more positive in relation to use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) (item 21) and, above all, to the use of a combination of visual, textual, and/or numeric input to cater for diversity (item 22) (cf. ).

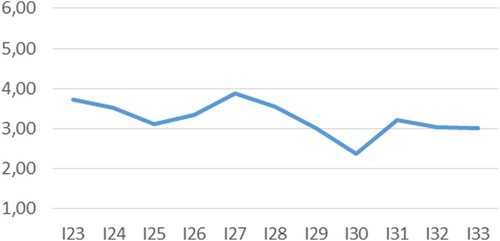

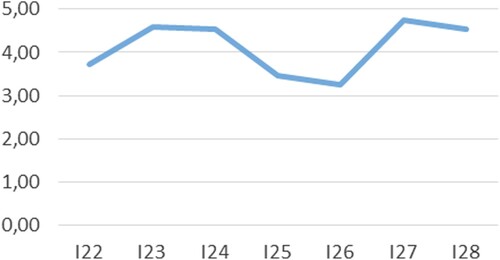

As regards evaluation, the data gathered are less satisfactory. Not all students agree (means are close to 4) that their teachers cater for different abilities in continuous (item 23) and final assessment (item 24), and that in continuous assessment they provide detailed guidelines as extra support (item 27), as well as personalized and regular feedback (item 28) in terms of different abilities. To make it worse (means are close to 3), students in general slightly disagree that: practitioners vary the grading criteria (item 25), their own performance has improved as a result of teachers taking into account different abilities (item 26), in continuous assessment the class activities are adapted (item 29), in final assessment several strategies are adopted (items 31 and 32), and self-assessment is being taken into account to cater for diversity (item 33). Learners even disagree that homework is provided according to individual levels of ability (item 30). No mean in this block reaches 4 in the scale (see ).

Vis-à-vis teacher coordination and development, an optimistic outlook can be detected. Students slightly agree that, at school, they have the support of multi-professional teams to make their classroom more inclusive in terms of ability (item 34), there is parental support and engagement (item 39), and there is a support system to help them with their CLIL classes with which they are satisfied (item 40). On a quite positive side, this cohort acknowledges that there is a guidance counsellor who helps those with different needs and their families (item 35) and that the teaching figures who form part of the bilingual program are sufficiently prepared to cater for different abilities (items 36-38). There is not much consensus, though, in connection with NLA teachers and TAs (cf. ).

Teachers find it challenging to teach CLIL classes with learners who have different levels of ability in the FL (item 1) and in general (item 2), and not all agree that it is equally challenging to address this type of diversity in the CLIL and non-CLIL classrooms (items 3 and 4). They believe that they provide scaffolding (items 5 and 6), which is congruent with students’ opinions, although they only slightly agree that they repeat parts of a lesson in their first language to help them understand the content they are learning (item 7). They have a self-complacent view of their communication skills in the target language (item 8) and think their specialized academic language (item 9) is sufficient to cope with different abilities in their CLIL classroom (cf. ).

In line with the first items of the previous block, teachers slightly disagree that it is easy to design a CLIL lesson that caters for students with different abilities (item 10). Pertaining to most of the various issues about methodology and types of groupings, they partially agree, on a general basis, that: they have an adequate repertoire of methods at their disposal to help learners with different abilities (item 11), their classroom work is student-centered (item 12) –which is congruent with their partially disagreeing that it is teacher-led (item 16)–, they base classroom work on cooperative learning principles (item 13), they plan for multiple intelligences (item 14), they use task-/project-based classroom work, they use mixed-ability groups, they provide personalized attention, and they vary classroom layouts (item 20), all these behaviors to meet the needs of different types of learners in CLIL. Particularly salient is the use by the majority of teachers of peer mentoring and assistance strategies aiming towards it (item 19). Finally, as was the case in the student questionnaire, practitioners slightly disagree about the existence at their school of newcomer classes to support the integration of learners into CLIL (obtaining the lowest mean, item 21) (cf. ).

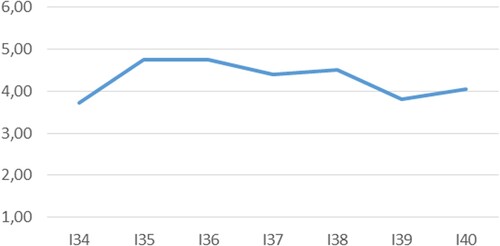

This cohort projects somewhat more positive perspectives on the whole in relation to materials and resources as they either slightly agree (item 22: having access to materials and resources that already take into account different levels of ability among students) or agree (items 23 and 24: normally adapting and creating them; and items 27 and 28: finding ICT useful and using a combination of visual, textual, and/or numeric input to address diversity in terms of ability) with the aspects in this category, with the exception of those about adapting and creating materials for an academically diverse group being easy (items 25 and 26), with which they slightly disagree (cf. ).

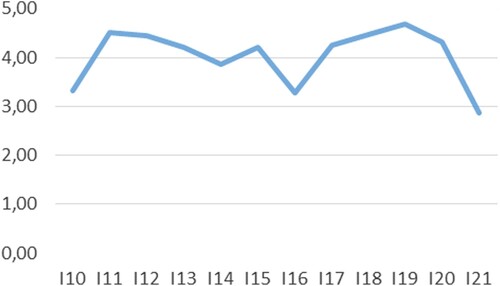

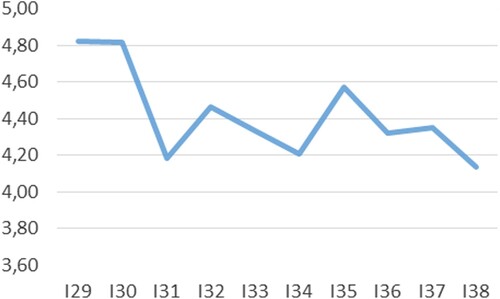

An undeniably better conclusion on assessment can be drawn from this stakeholder. Not only do teachers partially agree with the vast majority of items in this block (31-34 and 36-38), including those with which the learner cohort disagrees, but also they predominantly attend to different abilities in their continuous (item 29) and final assessment (item 30), and adapt the activities they ask their students to do in class to their level of ability (item 35). The opposite scenario revealed by the student appraisal of this category can be reported now: no mean is below 4 in the scale (see ).

Pertaining to coordination, the first of the two global aspects analyzed in the fifth block, teachers evince coordination/collaboration with their colleagues in the bilingual program in order to cater for different abilities (item 39) and they find the support of multi-professional teams essential for that purpose (item 40). The outlook here is eminently positive considering that they also state that at their school they have a guidance counsellor who helps learners with different needs and their families (the one yielding the highest mean in the survey: 5.22, item 42), they encourage parental support and engagement towards CLIL (item 43), and there is a support system in place to cater for different abilities in CLIL with which they are satisfied (item 44). The exception to these positive results is their opinions about the preparation of TAs and attention to diversity. NLA and FL teachers only slightly agree that language assistants are sufficiently prepared for that (item 41), thus partly concurring with students’ perceptions, which included NLA teachers in this group too (cf. ).

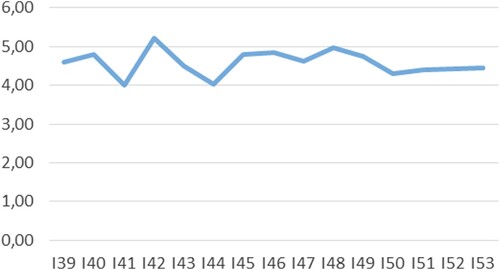

The last nine items of the block address teacher development. A prevailing tendency to express further education needs in different issues that allow them to cater for different abilities in the CLIL classroom can be pointed out. Practitioners would welcome more training in linguistic scaffolding techniques, student-centered methodologies, the use of different classroom organizations, and how to design and adapt materials, together with having access to more materials (items 45-49). Although not all agree, further education in how to collaborate/coordinate with colleagues, engage with parents, assess students, and critically analyze their own teaching practice from the perspective of serving learners of different abilities (in CLIL) also seems to be necessary (items 50-53) (cf. ).

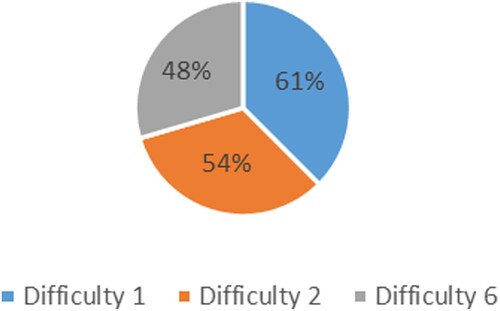

Now, the ranking of the top three most important difficulties, best practices, and further education needs according to teachers will be reported on. Those that were ranked in either first, second or third place with higher frequency are: finding it challenging to teach CLIL classes with learners who have different levels of ability in the FL (61% of respondents included it at the top three) and of ability in general (according to 54% of the sampled teachers), and finding it difficult to cater for different abilities without the support of multi-professional teams (obtaining 48% of answers) –cf. , on difficulties; using a combination of visual, textual, and/or numeric input, organizing student-centered classroom work, and scaffolding language to support different abilities (ranked high by 56%, 43%, and 38% of practitioners, respectively) – cf. , on best practices; and needing further education in student-centered methodologies, needing access to more materials, and needing further education in how to design and adapt materials which allow them to cater for different abilities in CLIL (each of these items indicated by 57%, 46%, and 41% of teachers) –cf. , on teacher development.

It is worth mentioning that the difficulty, best practice, and teacher development need that was more often selected in each ranking (i.e. combining values 1-3) was also the one unveiled as most important (value 1). In addition, these outcomes totally coincide with the analysis of the correlated items in the previous blocks, which yielded some of the highest means in the survey.

Harmony between the information derived from the interview protocols and the opinions witnessed in the surveys is prevalent. Teachers request additional support measures so that attention can be given to all types of learners now that the move is increasingly being made from bilingual sections to fully bilingual schools. Multi-professional teams are fundamental and practitioners clarified in the interviews that, although at their school they have a guidance counsellor who helps learners with different needs and their families (as stated in the questionnaire), rarely is s/he an expert in CLIL, so their help is limited. These demanded measures include teacher training to cater for diversity in bilingual programs, a bank of materials and resources for students of a range of levels, which are still lacking, reducing the teacher-student ratio so that more time can be devoted to the different types of learners according to ability, raising the number of sessions where TAs are present, diversifying student-centered methodologies together with continuous and final assessment, and increasing teacher coordination for this inclusive purpose in CLIL.

5.2. Specific results

Turning now to Metaconcern 2 (objective f), the differences between cohorts previously specified have been empirically corroborated by means of the application of the Mann–Whitney U test. Statistically significant differences can be detected across the entire survey, in 33 out of the 37 that could be compared (i.e. in a high 90% of them). The disparities are shared between the two groups in terms of linguistic aspects (two in favor of teachers and two in favor of students) and methodology and types of groupings (six in favor of teachers and four in favor of students) to a greater extent, and in terms of teacher collaboration and development (three in favor of teachers and one in favor of students), to a lesser extent. Nevertheless, in relation to materials and resources, and assessment it is teachers who always yield a significantly higher mean (five to zero, and ten to zero, respectively). Thus, there is usually broader agreement among practitioners with the statements expressed in the survey (26 cases), and especially in its third and fourth blocks, than among students (seven cases).

Similar results according to this non-parametric statistical test employed have been found on only four occasions: item 6-2, item 15-11, item 17-13, and item 44–40 (teachers-students), dealing with scaffolding the content of the CLIL lessons as a strategy to support different abilities, using task-/project-based classroom work, using mixed-ability groups, and being satisfied with the support system which the school currently has in place to cater for different abilities in CLIL, respectively, substantiating the incongruous responses (cf. ).

Table 1. Mann–Whitney U Test results of the across-cohort comparison.

6. Conclusion

As regards our first metaconcern, the overall conclusion that can be reached from the CLIL student and teacher perspectives on catering for diversity that have been identified is that Spain is still on its way to a favorable implementation of the CLIL approach for all learners. From the across-cohort comparison the second metaconcern consists in, it can be derived that their opinions are quite dissimilar across the whole survey, and particularly with respect to materials and resources, and assessment. They are usually in favor of practitioners. This points to the convenience of conducting further research engaging other stakeholders, like families, that are also involved in the implementation of CLIL programs.

Important steps towards the successful provision of CLIL to entire schools are being taken, but a CLIL agenda that seriously considers the designing of adequate materials, of pedagogical and assessment tips, and of teacher training programs to attend to diversity must be carved out. Luckily, at the time of writing it can be stated that the ADiBE project has already designed and piloted original materials that offer ‘differentiation triangulation’ on three levels of activity and from an interdisciplinary perspective, is in the process of taping a series of pedagogical videoguides that provide brief answers to key questions stemming from the whole transnational research published in this special issue, and has designed and piloted a course at the teacher training center of Córdoba (Spain) to guide teachers from more controlled to freer practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antonio Vicente Casas Pedrosa

Dr Antonio Vicente Casas Pedrosa is Associate Professor at the Department of English Philology of the University of Jaén, Spain. His research interests are in descriptive English linguistics (including English morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics), Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), and new technologies in language teaching.

Diego Rascón Moreno

Dr Diego Rascón Moreno is Associate Professor at the Department of English Philology of the University of Jaén, Spain. His research interests are in Applied Linguistics, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), values education, and new trends in language teaching.

Notes

1 Further information about this project can be found at https://adibeproject.com/.

2 According to Madrid Fernández and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018, 243–244), further information about these issues can be found in Julius and Madrid Fernández (Citation2017); Anghel, Cabrales, and Carro (Citation2016), Fernández-Sanjurjo, Fernández-Costales and Arias Blanco (published online in 2017 and printed in 2019) and Rascón Moreno and Bretones Callejas (Citation2018); Alejo and Piquer-Píriz (Citation2016); and Madrid Fernández and Barrios Espinosa (Citation2018), respectively.

3 Furthermore, Pérez Cañado (Citation2020) questions the validity of some of the beliefs regarding elitism, drawing the conclusion that ‘the charge of elitism certainly needs to be questioned’ (op.cit.: 15). This scholar (2021) has done so, ‘dismantling the assumptions put forward by Bruton (2019) as regards egalitarianism […]’, among other beliefs.

4 Nevertheless, the research conducted by scholars such as Fernández-Sanjurjo, Fernández-Costales, and Arias Blanco (Citation2019, 661) concludes that ‘participants with lower socio-economic status obtain lower scores than those coming from more privileged backgrounds’.

5 Cf. Madrid Fernández and Pérez Cañado (Citation2018, 244) for a taxonomy of the types of special needs that should be accounted for in the CLIL classroom.

6 In turn, Julius and Madrid Fernández (Citation2017) focus on Spanish university programs.

References

- Alejo, R., and A. Piquer-Píriz. 2016. “Urban vs. Rural CLIL: an Analysis of Input-Related Variables, Motivation and Language Attainment.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 29 (3): 245–262.

- Anghel, B., A. Cabrales, and J. M. Carro. 2016. “Evaluating a Bilingual Education Programme in Spain: The Impact Beyond Foreign Language Learning.” Economic Inquiry 54 (2): 1202–1223.

- Asociación Enseñanza Bilingüe. 2020. “Respuesta al estudio: `La incidencia del programa bilingüe en la segregación escolar por origen socioeconómico en la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid: Evidencia a partir de PISÁ, de Lucas Gortázar y P. A. Taberner.” Accessed February 7, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/yxeb3mu8.

- Barrios Espinosa, M. E. 2019. “The Effect of Parental Education Level on Perceptions About CLIL: A Study in Andalusia.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. doi:10.1080/13670050.2019.1646702.

- Bauer-Marschallinger, S., C. Dalton-Puffer, H. Heaney, L. Katzinger, and U. Smit. in this issue. “CLIL for all? An Exploratory Study of Reported Pedagogical Practices in Austrian Secondary Schools.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.

- Bilingual Education Act (Public Law No. 90-247: 783-820). 1968. Washington, DC: United States Congress. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/y3vq9f4c.

- Bruton, A. 2013. “CLIL: Some of the Reasons why … and why not.” System 41: 587–597.

- Bruton, A. 2015. “CLIL: Detail Matters in the Whole Picture. More Than a Reply to J. Hüttner and U. Smit (2014).” System 53: 119–128.

- Castle, M. 2004. H.R.1350 – 108th Congress (2003–2004): Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (Public Law No. 108-446: 2647-2808). Accessed February 7, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/yy6yvycg.

- Cioè-Peña, M. 2017. “The Intersectional Gap: How Bilingual Students in the United Stated are Excluded from Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (9): 906–919.

- Coyle, D., K. Bower, Y. Foley, and J. Hancock. in this issue. “Teachers as Designers of Learning in Diverse Bilingual Classrooms: A UK Case Study.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.

- Durán-Martínez, R. 2021. “Is bilingual education inclusive in Spain? An analysis of students with special educational needs in compulsory education.” Abstract of the poster to be presented at Working CLIL Virtual 2021. Second International Colloquium. A series of workshops and posters on Integration, Innovation & Inclusion in CLIL. p. 49. Porto (Portugal), March, 26-27 2021. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/y3yasj9u.

- Durán-Martínez, R., E. Martín-Pastor, and F. Martínez-Abad. 2020. “¿Es inclusiva la enseñanza bilingüe? Análisis de la presencia y apoyos en los alumnos con necesidades específicas de apoyo educativo.” Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía 72 (2): 65–82.

- Fernández-Sanjurjo, J., A. Fernández-Costales, and J. M. Arias Blanco. 2019. “Analysing Students’ Content-Learning in Science in CLIL vs. non-CLIL Programmes: Empirical Evidence from Spain.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22 (6): 661–674.

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Gortázar, L., and P. A. Taberner. 2020. “La incidencia del programa bilingüe en la segregación escolar por origen socioeconómico en la Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid: Evidencia a partir de PISA.” REICE. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 18 (4): 219–239.

- Julius, S. M., and D. Madrid Fernández. 2017. “Diversity of Students in Bilingual University Programs: A Case Study.” The International Journal of Diversity in Education 17 (2): 17–28.

- Kremer-Sadlik, T. 2005. ““To be or not to be Bilingual: Autistic Children from Multilingual Families.” In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, edited by J. Cohen, K. T. McAlister, K. Rolstad, and J. MacSwan, 1225–1234. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. https://tinyurl.com/y4kxla49 (last access: February, 7th 2021).

- Liasidou, A. 2013. “Bilingual and Special Educational Needs in Inclusive Classrooms: Some Critical and Pedagogical Considerations.” Support for Learning. British Journal of Learning Support 28 (1): 11–16.

- Madrid Fernández, D., and M. E. Barrios Espinosa. 2018. “A Comparison of Students’ Educational Achievement Across Programmes and School Types with and Without CLIL Provision.” Porta Linguarum 29: 29–50.

- Madrid Fernández, D., and M. L. Pérez Cañado. 2018. “Innovations and Challenges in Attending to Diversity Through CLIL.” Theory Into Practice 57 (3): 241–249.

- Marinova-Todd, S. H., P. Colozzo, P. Mirenda, H. Stahl, E. Kay-Raining Bird, K. Parkington, K. Cain, et al. 2016. “Professional Practices and Opinions About Services Available to Bilingual Children with Developmental Disabilities: An International Study.” Journal of Communication Disorders 63: 47–62. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/y2dcg5rp.

- Martín-Pastor, E., and R. Durán Martínez. 2019. “La Inclusión Educativa en los Programas Bilingües de Educación Primaria: un Análisis Documental.” Revista Complutense de Educación 30 (2): 589–604.

- Nikula, T., K. Skinnari, and K. Mård-Miettinen. under review. “Diversity in CLIL as Experienced by Finnish CLIL Teachers and Students.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.

- No Child Left Behind (Public Law No. 107-110: 1425-2094). 2001. Washington, DC: United States Congress. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/y2ucfbty.

- Paran, A. 2013. “Content and Language Integrated Learning: Panacea or Policy Borrowing Myth?” Applied Linguistics Review 4: 317–342.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2018. “The Effects of CLIL on L1 and Content Learning: Updated Empirical Evidence from Monolingual Contexts.” Learning and Instruction 57: 18–33.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. 2020. “CLIL and Elitism: Myth or Reality?” The Language Learning Journal 48 (1): 4–17.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. in this issue a. “Guest Editorial.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. in this issue b. “Inclusion and Diversity in Bilingual Education: A European Comparative Study.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L., D. Rascón Moreno, and V. Cueva López. in this issue. “Identifying Difficulties and Best Practices in Catering to Diversity in CLIL: Instrument Design and Validation.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.

- Rascón Moreno, D., and C. M. Bretones Callejas. 2018. “Socioeconomic Status and its Impact on Language and Content Attainment in CLIL Contexts.” Porta Linguarum 29: 115–135.

- Rundell, M., ed. 2021. . Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (MEDAL3). Oxford: Macmillan. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://www.macmillandictionary.com/.

- Scanlan, M. 2011. “Inclusión. How School Leaders Can Accent Inclusion for Bilingual Students, Families, & Communities.” Multicultural Education 4: 5–9.

- Siepmann, P., D. Rumlich, F. Matz, and R. Römhild. in this issue. “Attention to Diversity in German CLIL Classrooms: Multi-Perspective Research on Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.

- Somers, T. 2017. “Content and Language Integrated Learning and the Inclusion of Immigrant Minority Language Students: A Research Review.” International Review of Education. Journal of Lifelong Learning 63: 495–520.

- Ting, Y. L. T. under review. “Are CLIL Classrooms Harnessing ‘Diversity’ to Optimize Learning? Comparing Italian Contexts: One ‘That Must’ and One ‘That Wants to’.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism XX/X: XX–XX.