ABSTRACT

As increasingly more upper secondary schools mainstream bilingualism via an array of strategies, databases collecting students’ appraisals of their bilingual experiences become invaluable for informing practice. This paper discusses how the ADiBE Interview Protocol was adapted to efficiently collect candid appraisals from 99 students attending a high school in highly monolingual southern Italy. Students welcomed the opportunity to shape their instruction, generating a database of commentaries from which 11 thematic issues emerged: three related to improved language competence, personal growth and general satisfaction, while eight themes called for attention to methods, materials, classroom management and even scheduling. Appraisals are presented, alongside brief discussions regarding implications for teacher-training, task-diversity, task-choice and translanguaging strategies for optimizing the shared L1 in monolingual classrooms. That said, appraisals also unveiled expectations for native-speaking English-fluent Content-experts, which, in contexts such as ours, is not only unrealistic, but depreciates Content-experts who, although may not be fluent in English, know content very well. Appraisals indicate that students appreciate the opportunity for receiving bilingual instruction and are willing to put in extra work to learn ‘complex upper secondary content through a foreign language’, a challenge they feel could be rendered more manageable via more learner-centred, language-aware and inclusive pedagogies.

1. Introduction

This article contributes to the ‘ADiBE Movement’, Attention to Diversity in Bilingual Education, which, as Pérez Cañado (Citationn.d.) describes in the Introduction of this Special Issue, is a coordinated and concerted effort to raise awareness on the issue of diversity within bilingual classrooms across Europe. While diversity exists within any classroom, with bilingual education at upper secondary, where complex disciplinary content is already difficult in L1, differences in foreign language competence may contribute to furthering existent diversity. Other articles within this Special Issue have thoroughly reviewed the literature on this challenge, as also details regarding the administration and analyses of data obtained from the ADiBE Quantitative Likert-Survey and the ADiBE Qualitative Interview Protocol conducted with small focus groups (see Article 1 for details). This article contributes to the ADiBE initiative in three ways. Firstly, it illustrates how the ADiBE Interview Protocol can be organized to elicit detailed, written appraisals from all students; Secondly, contrary to some more multilingual contexts reported in this Issue, results here regard a bilingual initiative situated in a highly monolingual region of Europe, not dissimilar to many contexts throughout the world; Finally, we illustrate how, by examining a large body of students’ candid appraisals of their bilingual experience, it is possible to delineate concrete strategies that schools and teachers can use to support their learners, despite less-than-ideal(ized) bilingual contexts.

2. Research context

Descriptive details render qualitative data obtained from specific instructional contexts useful and informative for other contexts (Denzin and Lincoln Citation1994): This section therefore details crucial features regarding the CLIL-scenario of this study.

2.1. CLIL in Italy

Like in many European countries, CLIL in Italy initiated as a grassroots movement, mainly among language teachers. Providing authentic contexts for using the target-FL, which in Italy is primarily English, CLIL was welcomed as a way to improve FL-education in Italy, one of the least multilingual countries in Europe (Eurobarometer Citation2006). It was therefore surprising when, during the 2014–2015 school reformFootnote1 the Italian Ministry of Education mandated that non-lingua Content-teachers with C1-Level English competence, implement CLIL in their content-classrooms during students’ final year(s) in upper secondary. Universities were recruited to offer CLIL-Teacher-Training courses which primarily focused on helping Content-teachers achieve C1-Level English competence and, although pedagogy-training was included, these focused primarily on FL-pedagogies. Unfortunately, not many achieved C1-level English competence in a short time, few understood the relevance of FL-pedagogy for Content-instruction and, in the end, even fewer were interested in teaching already complex content in English (Di Martino and Di Sabato Citation2012), a language more foreign to Content-teachers than the students they teach.

2.2. Mainstreaming bilingual instruction in Calabria

This study involved students enrolled in the Bilingual Stream at one of the first state-run high schools mainstreaming bilingualism in the highly monolingual reality of southern Italy. Having one of the weakest economies in Europe (Eurostat Citation2020), Calabria is not a popular destination for foreign companies, tourists and English-speaking Content-graduates of Anglophone universities. Since few experienced Content-teachers readily embrace bilingualism, schools here face the dilemma ‘(A) start a little bilingualism with less-than-ideal teachers or (B) wait for fully-qualified teachers to go full-on bilingual?’: the school in this case opted for A. Four years prior to this study, the school had launched an International Steam based on four IGCSE (International General Certificate of Secondary Education) Certifications: Travel & Tourism; English as a Second Language; Combined Science; Information and Communication Technology. shows how these 2-year courses are merged into the 5-year national curriculum of 27–31 hours per week. Since school days in Italy end around 13:30, IGCSE lessons were appended to the regular schedule so that students stay on for only two extra hours every week. Students’ performance in IGCSE coursework is not averaged into grades of curricular coursework. At the time of this research, of the ca. 1200 students at the school, 129 were enrolled in the International Stream and the pioneer class of Year-4 had just initiated coursework in Information and Communication Technology.

Table 1. Organization of the four IGCSE courses throughout, and in relation to, students’ regular 5-year curricular coursework.

2.3. Profile of students, teachers and the school

To help readers evaluate the findings below, this section clarifies some important points regarding the various stakeholders. Firstly, since IGCSE-coursework represents extracurricular activity, students and families are highly motivated, sustaining additional non-evaluated coursework for five years. Secondly, since the school’s own Content-teachers are unwilling to teach the IGCSE courses, families enrolled in the International Stream contribute ca. €400/yearFootnote2, covering tuition with external teachers, textbooks and the four certifications. Thirdly, although students sit an English placement test, since the IGCSE coursework is adjunct to the regular curriculum to which all students have right-of-access, this test cannot exclude anyone from the International Stream. Therefore, students’ appraisals below mentioning ‘weak English’, either their own or their teachers’, should be interpreted with this in mind.

The external teachers had varying degrees of English fluency and teaching experience: The ESL teacher was a native English speaker, recent graduate of English from a UK university with little prior teaching experience and not fluent in Italian; the T&T teacher was Italian, graduate of an Italian university, owned a travel agency, had some experience teaching local tourism agents and was fluent in English; the CombSci teacher was Italian, Biology graduate from an Italian university, researched and taught at the local university, easily understood the IGCSE-textbook but rarely spoke English; the ICT teacher was Italian, graduate in Computer Sciences from an Italian university, worked in ICT, had no teaching experience and, at the time of data-collection, had only held one lesson so students were unable to comment on this teacher’s choice of methods or language(s).

Finally, why these teachers and why these certifications? Without CLIL-teachers with more appropriate professional profiles and without its own Content-experts, the school was obliged to prioritize Content-knowledge over CLIL-expertise. As for the IGCSE certifications, although some debate their standard (BBC Citation2006; The Guardian Citation2018), the school considered these certifications a straightforward strategy for mainstreaming bilingualism. According to the Cambridge IGCSE site (Citation2020), this school is not alone: ‘IGCSE is [an] international qualification for 14–16 year olds […] taken in over 150 countries and in more than 4800 schools around the world.’ While Year-4 and -5 students are older than that targeted for the CombSci and ICT certificates, A-level curricula would not be feasible since these students must nonetheless complete their 12-subject national curriculum.

3. Methods

3.1. Student voice: students’ voices

‘Student voice is a concept and a set of approaches that position students alongside credentialed educators as critics and creators of education practice’ (Cook-Sather Citation2020, 182). Educators gathering students’ voices on learning experiences must be sincerely respectful (Rudduck and McIntyre Citation2007), welcome candid criticisms and even voices questioning practices that we adults make (Berryman and Eley Citation2017). However, even in Norway, where a tradition of respecting children’s voices became national curriculum policy in 2020, students hesitate to speak candidly: ‘I feel like teachers should be able to take criticism, especially when they’re giving us criticism all the time. But I don’t feel comfortable giving them any criticism as I don’t know how they will take it’ (Jones and Bubb Citation2021, 8). Not surprisingly, therefore, student voice research is often longitudinal (Mager and Nowak Citation2012), spanning many years, during which rapport, trust and reciprocal respect are established between teachers and students, thereby liberating sincere students’ voices.

Therefore, with one-off interviews conducted by an external researcher, such as the case here, it becomes especially important for students to feel they can trust the researcher as conduit to those who could shape their learning experience: politely stated by a student in this study, ‘my best whishes (sic) goes to our teachers and I hope that they will consider my suggestions’. By collecting students’ appraisals, we recognize their ability to not only evaluate the education they are receiving, but also make pragmatic suggestions for improvement (Withers Citation2009). Indeed, Cook-Sather (Citation2009) proposes using high school students’ voices in teacher-training ‘to complicate the traditional model according to which educational theorists and researchers generate pedagogical knowledge and pass it down to teachers with students at the end of this transfer’ (178). Eliciting voices from high school students establishes a win-win situation for all: for students, voicing ‘fosters critical awareness of their educational experiences and opportunities and the confidence and vocabulary to assert what they need and want as learners’; teachers trained to listen to students’ voices become more ‘committed to eliciting and acting upon students’ perspectives not only during their preparation but also throughout their careers’ (ibid).

3.2. Eliciting and collecting all voices

As described in Article 1 of this Issue (Pérez Cañado, Rascón Moreno, and Cueva López Citationn.d.), the ADiBE Interview Protocol includes questions delineated through double-fold piloting and validation, organized into five question-blocks: linguistic aspects; methodology and groupings; materials and resources; assessment; teacher collaboration and development. Interview questions (hereafter ‘interview’) paralleled those in the Likert survey (hereafter ‘survey’) and, by following-up the survey, provided students an opportunity to further elaborate on their bilingual experience. Data were collected on a per class basis, taking approximately 2.5 hours to implement both survey and interview tools through a 3-Phase process. In Phase-1 (ca. 60 min), following a short introduction to the ADiBE Project, students accessed the online 40-item Likert-survey, working individually but guided through each Likert-item by the researcher, in plenary. This gave the researcher a preliminary window into students’ bilingual experience: e.g. questions such as ‘what do you mean by groupings?’ and overheard mutterings such as ‘we rarely work in groups’ and ‘we’re always grouped with the same people sitting nearby … so boring … ’

In Phase-2 (ca. 80 min), the interview, commentaries in Phase-1, sottovoce or otherwise, were used to group students with peers they usually do not work with. The ADiBE interview question-blocks (see Appendix 5 of Article 1, this Issue) were organized into activity sheets containing one question-block per sheet. To establish an atmosphere of meaningful reflection and trust between students within each group, students were instructed to first discuss the questions among themselves before writing a group answer to hand in and then sharing their group’s opinions in plenary. This process gave groups time to cohere and reflect more deeply on their bilingual experience. In addition, since students did not know the external researcher, while students discussed the question-blocks in the safe-space of small groups, the researcher circulated and chatted with each group, thereby establishing rapport and trust. Phase-2 aimed to put students into an ‘appraising mind-set’, ready to provide, in Phase-3, a final ‘Overall Personal Appraisal’ which was honest, well-thought-out and thus meaningful and informative. In Phase-3 (ca. 10 min), students shared, individually, in writing, and through an online platform, ‘Final Appraisals and suggestions for your teachers and school’. These Overall Personal Appraisals (hereafter ‘appraisal’) were anonymous and students were encouraged to use whichever language they wished (English or Italian), to express themselves most clearly.

4. Findings & implications

4.1. General profile of cohort

presents general information regarding the 129 students enrolled in the International Stream. It is noteworthy that 97 (i.e. 75%) were female. The home-language profile reflected the highly monolingual local environment: 98% (n = 127) reported Italian as their home-language and only 10 students mentioned four other home-languages: Albanian (n = 1); Ukrainian (n = 2); English (n = 7).

Table 2. General information regarding cohort.

The school welcomed this research on their bilingual initiative, suspending lessons for 2.5 hours for Year-2, 3 and 4 students. Since data collection took place six weeks into a new academic year, Year-1 students were not yet sufficiently settled to provide meaningful appraisals. Therefore, while all 129 students of the International Stream participated in the Likert-survey, written ‘Overall Personal Appraisals’ were collected from only the 99 students of Years 2–4.

4.2. Emergent themes

Of the 99 written appraisals from Year-2, -3 and -4 students, 24 were in English with an average length of 46.8 words per appraisal, comparable to those in Italian (49.5 words/appraisal). One appraisal from a Year-2 student (‘Euro-gol di cuadrado’) was difficult to interpret and excluded. A researcher coded the remaining 98 appraisals into themes. Since students wrote freely, appraisals related to the ADiBE survey but were not delimited by these Likert-items. shows the 11 themes emerging from the 98 appraisals and the frequency of each. Some appraisals represented a token for only one thematic issue, while others covered several, so counted as one token per relevant theme (). Multiple mentions of the same theme within a single appraisal counted as only one token for that theme. Three teachers (two from the school) analysed the appraisals independently and, where discrepancies arose, the teachers and the researcher discussed interpretations and agreed on final thematic allocation(s). This resulted in a consensus of 219 tokens distributed across 11 themes, organized, for ease of discussion, into five categories.

Table 3. Thematic issues emerging from the appraisals and the frequency (n) each theme was mentioned.

Table 4. Example of how appraisals containing multiple thematic issues were treated.

Appraisals written in English use this font, are presented as is, including mistakes, while appraisals translated from Italian are presented in italics and translated so to preserve the spirit of students’ voices. Appraisals from students of different years are presented, each tagged for respondent number/year: [55/3°] indicates respondent 55, from Year-3.

4.3. Areas for improvement

Although 76% of the tokens ‘called for change’, this should not be interpreted as students’ dissatisfaction with their experience but probably eagerness to optimize the rare opportunity to be heard, as voiced by a Year-4 student during Phase-2 of data collection: ‘Nobody ever asks us how we’d like to learn’.

4.3.1. Methods, materials, groupings

The most frequently mentioned issues regarded instructional strategies, with 43 appraisals inviting teachers to use different materials and resources (theme 1.1) and 27 requesting methods and groupings that favour more student-centred pedagogies (theme 1.2). Only nine students mentioned both themes in their appraisals, which means 61 of the 98 students would welcome different instructional strategies:

English is the language of the ‘future’ and students should be prepared for a future world; there should be much more project work in groups so we collaborate and relate to others in a variety of contexts and through a variety of ways [15/2°].

I’d like to have in our lessons more creative and own projects [64/3°].

We could improve speaking simulating a conversation with people that we can meet in another country [70/3°].

When a science lesson becomes boring, the teacher could involve students in different activities, such as doing experiments which would fulfil the interest of the class [96/4°].

Teachers could improve the lessons and learning by involving us in different activities which might complement the school subjects, and providing more precise explanations using power point or worksheets [88/4°].

Most calls for ‘different materials and resources’ did not simply re-echo the digital modalities mentioned in the Likert-survey (IWBs, power-points, etc.) but reflected students’ appreciation for holistic heuristic strategies that go ‘beyond the book’:

Attract the attention of the entire class by referring to the reality we experience first-hand and have us discuss these … [65/3°].

It would be useful to do more work that brings forth our creativity which I believe is a fundamental element in today’s society and can therefore inspire young minds such as ours to create something useful! [26/2°].

It would be necessary to do activities which are not based only on the textbook [93/4°].

I think that the teaching method of the professors, however correct it is to read and explain using books, should change with regard to learning, having students work in groups because it helps understand better, giving us opportunities to compare and relate with each other [7/2°].

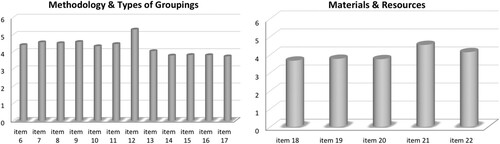

Appraisals calling for alternatives to traditional teacher-led spiegare/explaining triangulated with results from the 40-item Likert-survey (see Appendix 2 of Article 1 for survey-item wording; descriptive statistics obtained using SPSS). For example, survey-item-12 ‘our CLIL classroom work is teacher-led’ received the highest agreement of all 40 survey-items (5.30 ± 0.75: (left)), consistently across all four Years (p = 0.495; Kruskal–Wallis). Likewise, while the average Likert rating across all 40 survey-items was 4.25 (±1.42), survey-items suggesting teachers used ‘group-learning’ received low agreement (item-13: 4.05 ± 1.38; item-14: 3.79 ± 1.60; item-15: 3.79 ± 1.60). Likewise, survey-items stating that ‘teachers used’ or ‘created their own’ diversity-sensitive materials also received among the lowest agreement ( (right); item-19: 3.77 ± 1.58; item-20: 3.75 ± 1.63). Finally, at least one appraisal in each class mentioned teachers’ heavy reliance on textbooks, rather worrying considering the low agreement for survey-item-18, ‘the textbook takes into account different levels of achievement among students’ (3.67 ± 1.59).

Figure 1. Likert ratings given to items in two categories of the ADiBE survey: See text for explanations of how these quantitative survey-results triangulated with students’ appraisals.

Implication-1: Content-teachers might more readily cater to diversity if trained to (1) appreciate the benefits of student-centred, dialogic learning; (2) transform textbook information into active and interactive tasks, thereby providing student-centred instruction that is level-appropriate and content-relevant; (3) contextualize school subjects within everyday experiences (National Research Council Citation2000).

4.3.2. Awareness of diversity

That teachers need to become more aware of diversity was voiced in 15% of the appraisals, with 19 comments requesting ‘more differentiation’ to acknowledge individual strengths and 14 requesting ‘attention to students’ struggles’:

Teachers should push students to do always more and give different homework to the best students [61/3°].

The teachers could focus more on group projects personalized so that every group should be diverse and versatile, with different skills and abilities [58/3°].

It is necessary to take into consideration the identity and predisposition of each student, without setting aside the passions and characteristics that distinguish each person [91/4°].

Dedicate particular attention to students who are having problems learning the subject or generally with the foreign language: give them suggestions, different assignments, dedicate more time and attention to them. It’s important to speak a lot because, in this way, students can learn the language well, but at the beginning, it is important to speak more slowly to help those students who, unlike others, may not understand immediately. Not all of us have the same level of English and sometimes, those weaker don’t feel up to the demands of the course so it is crucial to align this difference and help those who struggle to understand [20/2°].

These appraisals triangulated with the fact that survey-item-3, ‘my CLIL teachers provide different homework according to individual levels of ability’, received the second-lowest affirmation of all 40 Likert-items (3.15 ± 1.82: mode 2). That their teachers are not catering to diversity sits uncomfortably with students’ awareness that teachers can see diversity:

It would be nice to work more often in groups that are even, not always good people together, and weaker students separately, so we can compare with each other and never be bored [50/3°].

Students do not doubt teachers’ abilities to notice differences but would simply like ‘profiling’ to benefit learning. Indeed, requests for teachers to attend to diversity reflected a high degree of trust in teachers’ professional abilities to tailor instruction, which could be as simple as knowing when and how to optimize L1:

Professors should try to help weaker students individually without lowering the level of the class [38/3°].

It may be opportune to provide homework that allow individual students to train regarding topics that they find difficult, of course following suggestions from the teacher [33/2°].

To improve the programme, we must do more activities in class which allow us to collaborate and compare with each other. Naturally, these activities must be coordinated by the teacher, and if necessary he/she should correct us and help us [45/3°].

If the subject is difficult to understand in English, it’s necessary to explain it in the mother tongue of the students to whom one is explaining [19/2°].

Like this last comment, many appraisals from Year-2 students called upon their teachers to remember that students’ English competence could, not only determine academic performance, but may represent a potential source of emotional distress for those with weaker language skills:

Not everyone has the same level of English, so more attention should be given to those who might feel or who are at a disadvantage compared to others, maybe giving easier homework to those who need it [35/2°].

Not all students in this Stream have the same level and really too often, teachers don’t pause in front of such disparities. I believe it is NECESSARY that teachers pay more attention to the various difficulties of the students with lower levels (difficulty speaking, understanding the lesson, etc.). This International Stream offers work opportunities to ALL, it is only fair that every student can fully benefit from this for enriching their competence [22/2°: capitals in original].

I believe that we students need to be stimulated from all points of view, so maybe working on different capabilities or using different methods that are a little more alternative. It is necessary to concentrate on individual differences to avoid creating discomfort or displeasure between us since, being adolescents, we tend to be emotional and easily discouraged [28/2°].

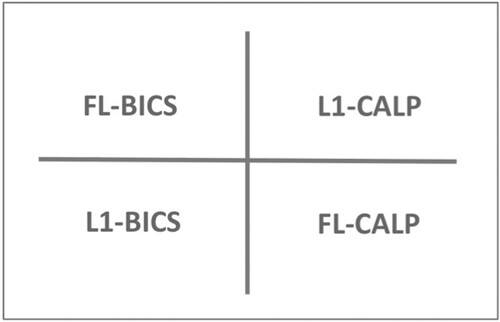

Implication-2: Students in this Bilingual Stream experience a complexity of tensions: they are invested in an experience highlighting ‘English’, the very thing which might generate (yet another) source of adolescent angst. Teachers’ ability to manage diversity is essential in all contexts but becomes crucial in bilingual classrooms. Remediation may ‘offer choice’ and/or ‘consider diversity as resource’: teachers might allow students to choose between different types of tasks, homework and projects which are designed to nonetheless enable all students to gain comparable content comprehension and mastery of language. Projects/activities may also value non-lingual abilities (artistic, musical, graphic, theatrical, etc.), allow students ‘to stay in my comfort zone and do what I do well’ but nonetheless encourage students to occasionally ‘take on a task which challenges me this time around’ (Dweck Citation2006). Finally, in monolingual realities, L1 represents a powerful instructional tool if deployed through rigorous translanguaging procedures (see Celic and Seltzer Citation2013; Li and Garcia Citation2016). As one student suggested in layman’s terms, ‘Italian and English should both be used to help us understand content, by simplifying many times and in different ways’ [51/3°]. For example, by making explicit the notions of Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP: Cummins Citation1984), teachers could introduce a simple FL/L1-vs.-BICS/CALP Grid (), and guide students through the explicit and strategic use of L1-BICS or L1-CALP as translanguaging scaffolds into content presented through the FL-CALP of textbooks. This would allow teachers to remain anchored to textbooks while encouraging students to actively and collaboratively discuss content while consciously and systematically using various registers in both the FL and L1 (Ting Citation2020).

Figure 2. A FL/L1-vs.-BICS/CALP Grid clearly delineates the language codes available within a bilingual classroom, all of which can be deployed through translanguaging tasks designed to facilitate content comprehension and the mastery of disciplinary discourse in both students’ L1 and the CLIL-language of instruction (FL).

4.3.3. Teachers’ competences

While most of what happens in classrooms relate to ‘teachers’ competence’, themes 3.1 and 3.2 captured appraisals referring to, respectively, ‘how teachers managed the bilingual classroom’ and ‘teachers’ English proficiency’.

Appraisals in theme 3.1 ranged from suggestions for managing classroom dynamics, to calls for recognizing what students feel they need to learn:

In class, it is often the same people speaking, leaving little room for classmates: professors should show interest towards students who are more timid, also encouraging these students to express themselves [30/2°].

Things can be improved a lot, for example, by explaining in English and not only in Italian, having us do simulations to prepare us for the tests, preparing more activities (also as group-work) which would stimulate us to speak in English [85/4°].

I think that the most important thing is to improve speaking skills because nowadays we would like to go work abroad so we firstly need to speak enough well and to do this it is important that the teacher speaks english* fluently and he/she should let us speak in english* too but not repeating by heart but we need to feel like english* students. While for the exam it is important that we know how to write the concepts clearly without translating from italian*. In my opinion the Program could send more mother tongue teacher to our international school [77/3°; *sic].

Implication-3: The bilingual classroom should welcome the participation of even students with weak language skills. By recognizing L1 as a valid code in bilingual classrooms, L1/FL can intersect BICS/CALP at different levels (): for example, teachers could instruct students to ‘re-explain that concept to your 12-year-old cousin in Milan/Melbourne’ thereby liberating students from ‘repeating by heart’. Secondly, cultivating BICS/CALP-awareness would reinforce students’ confidence in their ability to ‘write properly in English at the exam’, which also benefits students’ academic writing in L1 (Grandinetti, Langellotti, and Ting Citation2013). Finally, by making explicit all language codes available within the FL/L1-vs.-BICS/CALP Grid, it becomes obvious that it is not the teacher’s level of FL-competence that matters but how well students can, at the end of the day, use all language-codes on the Grid to efficiently and correctly language about content.

Interestingly, students’ clear understanding of what needs learning and their ability to delineate good solutions contrasted with frequent and unrealistic request for ‘mother-tongue teachers’. Twenty-five appraisals, mostly from Year-3 (n = 11) and Year-4 (n = 9) students, called for fluent, if not native English speakers. In fact, while many Year-2 students requested that teachers respond to their struggles by using L1 when necessary, older students requested their teachers stop speaking in L1 and use English. This probably reflects the fact that earlier coursework with English-fluent teachers gave way to teachers who rarely spoke English (see Section 2.3). Some attributed the lack of English-fluent Content-teachers to poor institutional organization:

The school should reduce class size and not worry about how many classes are created in this International Stream or whether this Stream makes the school look good but concentrate on English learning, assigning ONLY mother tongue English teachers [59/3°: capitals in original].

Schools that decide to embark on bilingual projects should be conscious of the fact that it is fundamental to have professors who are prepared in the subject matter and in English (maybe even mother tongue), and should not be, every year, dealing with the lack of professors who are good in the subject but without a minimal level of English flanked by mother tongue English professors who, in theory, should serve to translate but whose presence helps little [90/4°].

Others expect English-fluent Content-teachers to come equipped with special features:

Having more native speakers that also know the students’ first language would improve our learning of a Foreign language [62/3°].

Teachers should be mother-tongue and understand the weakest and strongest points of each student, so providing an adequate and personalized evaluation of each student [54/3°].

I think it's necessary a mother tongue teacher that is able to understand the different talents of the students [68/3°].

Implication-4: These appraisals highlight a need for ‘user-training’, i.e. helping students and their families formulate realistic expectations about instructional methodologies rather than teachers’ English competence. Indeed, students know what they need, appreciate effective pedagogy, the successful management of diversity, and where necessary, can even provide suggestions for improvement:

While I've grown a lot and made steady progress studying ESL, thanks to my amazing teacher who took into consideration both strong and weak points of everyone in the class, I can say that the way things went with Combined Sciences is totally different. Not only is the preparation of the teacher insufficient to help us achieve our goal (getting a certification) but also I don't really appreciate the way the lessons are structured and all the topics covered in the syllabus (way too many for such a short time alloted (sic)). I'd suggest that the teachers be more aware of the ultimate goal they are supposed to attain along with the students and engage them with more compelling practical activities that help us put into practise what we have learned [98/4°].

4.3.4. School-level organization

Although item-34 of the Likert-survey regarding ‘the presence of multi-professional teaching-teams’ received the lowest agreement of all 40 Likert-items (3.12 ± 1.95: mode 1), no appraisals mentioned the need for teaching-teams. Rather, 10 of the 14 appraisals regarding school-level (re)organization revealed students’ eagerness to optimize their bilingual experience: ‘increase the hours to do more lessons’ [83/4°], ‘ … more activities’ [47/3°], ‘ … even in the afternoon’ [52/3°]. Their bilingual courses also deserved better time-tabling and more serious consideration: ‘I would prefer the lessons would be in the morning in the first hours, cause to do it at the six(th) hour is really annoying and not useful at all’ [74/3°]; ‘Our work here should be averaged into our school grades’ [90/4°].

While 11 students suggested enriching their bilingual experience through interactions with English-speaking students, travel and short-term exchanges, improvements in in situ methodology is nonetheless necessary: ‘Travelling is obviously the first method to help learning languages, but also using word-games, show images and conversing between ourselves in class would help us learn from our own mistakes and that of others’ [94/4°].

4.4. Positive appraisals

Of the 50 positive appraisals about the programme, almost half (n = 22) mentioned improvements in English language competence, the lingua franca valued for future prospects:

Thanks to this programme, in particular thanks to the ESL subject, English has become part of my daily life, no longer confined to only the school environment [95/4°].

Studying these subjects in English has helped me learn not only formal aspects of the English language but also content regarding physics, chemistry, biology, tourism and now, information technology [92/4°].

Students also noted that their bilingual experience involved ways of learning that have, and are, contributing to personal growth that goes beyond simply ‘more English’, and is worth the effort:

When I started the first year with ESL I was confident that it would be easy since I already had a good level of English. But I was wrong, getting a very low grade on the first test, which surprised me. My teacher explained to me that the ESL course is intended to help me develop ‘skills’ that are usually not developed in the Italian school curriculum and I should approach EFL as a ‘new topic’ in which we will learn how to write summaries, reports, reviews etc. As I started getting into this ‘British’ mentality, I realized that these skills will be very useful when I enter in the world of work [97/4°].

Last year I had problems because of my shyness but my professor insisted I talk in front of the class. At first I did not like this, but with time, I understood that she did this to help me overcome this obstacle [31/2°].

What I like most about this bilingual programme the use of English, which I can use in the future for work and travel, cumulating experiences which are essential for my growth. Even if this calls for more effort, I am sure that it will pay off in time [14/2°].

4. Conclusions

Students’ voices showed that they are lucidly aware of the potential benefits of bilingual instruction and are willing to invest extra effort. To date, there are ‘no carefully designed and validated questionnaires, interview, or observation protocols which concomitantly tap into catering for diversity in CLIL programmes, are adapted to different scenarios for further iterations, and factor in stakeholder perspectives’ (c.f. Article 1 of this Special Issue). Here, we have illustrated how the ADiBE Interview Protocol was adapted to collect appraisals and suggestions from a large cohort of students (n = 99) enrolled in a bilingual programme in a highly monolingual context. In fact, the depth of insights and concreteness of solutions offered by students, confirms that students are indeed capable and valuable ‘critics and creators of education practice’ (Cook-Sather Citation2020, 182). At upper secondary, bilingual education means ‘learning complex content through a foreign language’. This rather unappealing proposition is definitely justified if ‘foreign language’ sparks change in Content-instruction so that ‘lessons are more engaging, using more up-to-date methods and materials’ [40/3°]. Students themselves identified various student-centred methods for harnessing diversity and individuality to motivate collaboration and learning, listing reasonable suggestions for how materials, classroom-dynamics, homework and even school-level organization could be tweaked to help them overcome difficulties.

The only unrealistic request was for mother-tongue/English-fluent Content-graduates. If the motivation to learn English is its function as a lingua franca, as voiced here, insistence on a ‘mother-tongue-ideal’ is not only non-productive (Seidlhofer Citation2001), it overlooks the fact that bilingual education represents an opportunity for improving Content-instruction. In fact, even when explained in students’ L1, upper secondary Content is already challenging, not because the Content-teacher does not speak L1 fluently. Appraisals indicate that CLIL-initiatives should help stakeholders focus less on how well the Content-teacher speaks English (or the target CLIL foreign language) but more on whether instructional strategies support the comprehension of complex content and help students master the complex discipline-appropriate ways of languaging about content.

To conclude, as high schools in various socio-demographic contexts, with varying degrees of mono/multi-lingualism, mainstream bilingualism in various ways (Pérez-Cañado Citation2012), empirically derived databases of students’ voices from various bilingual classrooms becomes invaluable for improving on-going programmes, informing teacher-training, guiding new initiatives and also redirecting unrealistic expectations towards attainable and useful objectives. Indeed, the database of students’ voices reported here has already been used in a professional development programme to help teachers at another school in the same city to also mainstream bilingualism. By poring through students’ appraisals, teachers in the second school have been able to ‘see learning through the eyes of students’ (Hattie and Yates Citation2014, xi), prompting originally reluctant Content-teachers to shift their attention away from ‘I don’t speak English’ towards discussions regarding how they might implement the various pragmatic solutions students had suggested so to instil more inclusive methodologies, task-types, groupings, materials, homework, etc. In monolingual contexts such as ours, bilingual initiatives at upper secondary should be interpreted as an opportunity to evolve Content-instruction towards more learner-centred and inclusive pedagogies: how else can students ‘understand complex content presented through a foreign language’?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yen-Ling Teresa Ting

Y-L. Teresa Ting is Assistant Professor of English Linguistics at the University of Calabria, Italy. She researches how findings from cognitive neuroscience can guide the design of CLIL/EMI instructional materials, especially for STEM at higher levels. Some of her CLIL-materials have received international awards (ELTons Award 2013) and been incorporated into students’ textbooks (e.g. Cambridge University Press ‘Talent’ Series).

Notes

1 Regolamenti Applicativi 2010 (d.p.R. n. 88 and n. 89): ‘The teaching of one non-linguistic subject through a foreign language starting in (1) the last year of all lyceums and technical high schools and (2) in the third year (of five) at linguistic high schools, where a second CLIL-language is added in the fourth year.’ (see: https://miur.gov.it/normativa1; https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2010/06/15/137/so/128/sg/pdf).

2 Some have argued that CLIL is ‘elitist’ (Bruton Citation2011): To help readers evaluate the financial weight of this tuition, note the following: the gross annual starting salary for teachers in Italy ranges from €22,000 to €29,000 (https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/teachers-salaries-2021_en); locally, the net hourly wage of housekeepers starts at €8.00.

References

- BBC News. 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/education/6177592.stm.

- Berryman, M., and E. Eley. 2017. “Succeeding as Māori: Māori Students’ Views on our Stepping up to the Ka Hikitia Challenge.” New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 52: 93–107.

- Bruton, A. 2011. “Is CLIL so Beneficial, or Just Selective? Re-Evaluating Some of the Research.” System 39: 523–532.

- Cambridge IGCSE. 2020. https://www.cambridgeinternational.org/about-us/what-we-do/facts-and-figures/.

- Celic, C., and K. Seltzer. 2013. Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide for Educators. https://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Translanguaging-Guide-March-2013.pdf.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2009. ““I Am Not Afraid to Listen”: Prospective Teachers Learning from Students.” Theory Into Practice 48 (3): 176–183.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2020. “Student Voice Across Contexts: Fostering Student Agency in Today’s Schools.” Theory Into Practice 59: 182–191.

- Cummins, J. 1984. Bilingual Education and Special Education: Issues in Assessment and Pedagogy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 1994. Handbook of Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Di Martino, E., and B. Di Sabato. 2012. “CLIL in Italian Schools: The Issue of Content Teachers’ Comptence in the Foreign Language.” In Teaching Approaches to CLIL, edited by R. Breeze, F. Jimenez Berrio, C. Llamas Saiz, C. Martinez Pasamar, and C. Tabernero Sala, 71–82. Universidad de Navarra: Pamplona.

- Dweck, C. S. 2006. Mindset: How You Can Fulfil Your Potential. London: Robinson.

- Eurobarometer. 2006. Europeans and Their Languages. Special Eurobarometer 243. Brussels: European Commission.

- Eurostat. 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/regions/.

- Grandinetti, M., M. Langellotti, and Y.-L. T. Ting. 2013. “How CLIL Can Provide a Pragmatic Means to Renovate Science Education – Even in a sub-Optimally Bilingual Context.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16: 354–374.

- The Guardian. 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/jul/10/exams-political-decisions-igcse-gcse-universities.

- Hattie, J., and G. Yates. 2014. Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn. London: Routledge.

- Jones, M.-A., and S. Bubb. 2021. “Student Voice to Improve Schools: Perspectives from Students, Teachers and Leaders in ‘Perfect’ Conditions.” Improving Schools 24: 233–244.

- Li, W., and O. Garcia. 2016. “From Researching Translanguaging to Translanguaging Research.” In Research Methods in Language and Education, Encyclopedia of Language and Education, edited by K. King, Y.-J. Lai, and S. May, 1–14. Switzerland: Springer.

- Mager, U., and P. Nowak. 2012. “Effects of Student Participation in Decision Making at School. A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Empirical Research.” Educational Research Review 7: 38–61.

- National Research Council. 2000. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Pérez-Cañado, M. L. 2012. “CLIL Research in Europe: Past, Present, and Future.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 15 (3): 315–341.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. n.d. Introduction of this Issue.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L., D. Rascón Moreno, and V. Cueva López. n.d. Article 1 of this Issue.

- Rudduck, J., and D. McIntyre. 2007. Improving Learning Through Consulting Pupils. London: Routledge.

- Seidlhofer, B. 2001. “Closing a Conceptual Gap: The Case for a Description of English as a Lingua Franca.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 11 (2): 133–158.

- Ting, Y.-L. T. 2020. “The Symbiotic Energy of [Complex Content] + [Foreign Language]: Translanguaging Towards Disciplinary Academic Literacy.” In Examining Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Theories and Practices, edited by L. Khalyapina, 37–61. Philadelphia: IGI Global.

- Withers, M. 2009. “Why the Student Experience Matters.” New England Journal of Higher Education 24: 17–19.