ABSTRACT

While the language portrait (LP) is a visual research method that can make visible speakers’ multilingualism, this article considers how and why speakers may use the LP to make elements of their linguistic repertoire invisible. Analysing the portraits created by three primary school students in Luxembourg, I explore why these young people omitted different linguistic resources in the visual representation of their linguistic repertoire. Combining subject-based perspectives on multilingualism grounded in the lived experience of language with scholarship on silence and visual silence, instances of such erasures are explored in light of their formal, content and functional dimensions. More specifically, I analyse how visual silence can function as a strategy to align the LP with how speakers understand their linguistic repertoire and sense of self, and explore visual silence as a subversive act of resistance against curricular languages at school. The conclusion highlights the affordances of the LP as a visual, creative method that can support subject-based approaches to multilingualism and offers speakers a potentially empowering way to visually and discursively affirm their linguistic repertoire, with visual silence constituting an intentional strategy within this process of representation.

Introduction

The music is not in the notes, but in the silence in between. Various musicians have been credited for this quote, and it speaks to the importance of silence in meaning-making – this is not only true for music, but also for semiotic interactions more widely. As such, silence can be an important communicative resource that has been researched in discursive contexts and in other modalities. In this paper, I focus on silence in the visual mode by exploring visual silence in the language portrait (LP). This creative research method opens up visual-discursive spaces to explore speakers’ understandings and representations of their complex linguistic repertoires and lived experience of language. In educational contexts in particular, where students’ home languages are often ignored, dismissed and silenced if they are not part of the official curriculum, the LP has evolved from a language awareness exercise to an instrument that can make students’ multilingualism visible (Tabaro Soares, Duarte, and Meij Citation2020, 1). However, the present analysis focuses on a different functional aspect of the LP, namely its use by young people to erase linguistic resources from the representations of their linguistic repertoires. The resulting absences in these visualisations are conceptualised as visual silence. Based on three portraits created by primary school students in Luxembourg as part of a wider study on young people’s lived experience of language and language education policy (Muller Citation2020), I explore such instances of visual silence in light of its formal, content and functional dimensions and also address interactional and ethical aspects. This analysis is framed by an innovative approach that combines subject-based approaches to multilingualism with scholarship on silence and visual silence.

Subject-based approaches to multilingualism, visual methodologies and the language portrait

The theoretical framing of this paper builds on subject-based approaches to multilingualism that place the speaker and their sense of self at the centre of analysis, and employs a visual methodology centred on the language portrait to explore young people’s visual and discursive representations of their linguistic repertoires. Research on the complex linguistic repertoires and language practices of multilingual speakers has been growing over the last few decades following the multilingual turn (May Citation2014). In applied language studies and sociolinguistics more specifically, biographical and subject-based approaches to multilingualism have formed a productive research strand and explore how multilingual speakers feel and think about the languages and language practices in their lives (Kramsch Citation2009; Busch Citation2017). The linguistic repertoire has emerged as a key concept for such approaches and, drawing on a subject-based biographical framework, Busch (Citation2017) defines the linguistic repertoire as intersubjective, relational and comprising not only of semiotic resources but also the lived experience of language. This notion refers to the emotional and bodily dimensions of language including beliefs, attitudes and ideologies that are connected to a speaker’s semiotic resources.

The interest in how speakers make sense of their multilingualism has also marked other fields of inquiry under the affective turn (Pavlenko Citation2013). In recent years, a growing number of studies have adopted subject-based perspectives grounded in the experiences of research participants in multilingual inquiries, and have also employed visual methodologies (see e.g. Kalaja and Pitkänen-Huhta Citation2018). The latter have become more commonplace through the visual turn which, first emerging in the 1990s in applied language studies, has proliferated an increased interest in the use of visual methods and creative inquiries (Kalaja and Pitkänen-Huhta Citation2018; Bradley and Harvey Citation2019; Chik and Melo-Pfeifer Citation2020). Such methodologies include, for instance, photo and video elicitations, collages or drawings, with the LP falling under the latter category. As such, the LP provides a multimodal, collaborative and self-reflective framework in which individuals can visually and verbally represent their linguistic repertoire by colouring in a blank body silhouette (Busch Citation2012). The creative process of visually producing an LP and the subsequent discussion that involves both discursive explanations and references to the portrait provide detailed insights into speakers’ understandings of their linguistic repertoire and lived experience of language. In this light, the LP generates multimodal data in which visual representations and discursive explanations exist in tandem as a ‘situational and context-bound production’ (Busch Citation2018, 7).

It is arguably impossible to completely eradicate power imbalances during data generation and this especially applies to studies involving young people as the structural, societal power imbalances between young people and adults as demographic groups also permeate interactions such as research interviews. The LP offers a multimodal, creative methodology that encourages more evenly balanced interactional grounds. For instance, the complementary, reciprocal nature of image and language in the meaning-making process can allow individuals to play to their strengths when articulating their perspectives. The entire creative process allows the participant to reflect on and become aware of their language practices (Busch Citation2018, 6), and through the reflexive visualisation processes taking place before and during the drawing stages, the participant can first engage with the task at hand before involving the researcher (Literat Citation2013, 85). This can provide participants with more interactional agency in sharing their creation with the researcher and in framing their responses and contributions rather than being only reactive to questions (Chik Citation2019, 30).

The LP has been employed in a variety of contexts (for an overview, see Busch Citation2021, 200), and this body of research has provided important theoretical and methodological contributions to subject-based research on multilingualism using visual methodologies. While previous LP research has focused on visible elements that are included in the drawings, the present analysis explores elements that are absent from portraits. This analytical focus builds on a spatial metaphor that underpins Busch’s conceptualisation of the linguistic repertoire as an inherently fluid, multi-layered, ‘heteroglossic realm of constraints and potentialities’ where ‘different forms of language use come to the fore, then return to the background, they observe each other, keep their distance from each other, intervene or interweave into something new, but in one form or another they are always there’ (Citation2017, 356). This spatial metaphor lays important groundwork on which I expand in this paper: rather than focusing on elements that feature in the foreground – those that speakers included and visually represented in their portraits, the analysis explores elements that were pushed to the background through an omission from the visualisation. As such, I explore young people’s understandings of linguistic resources that they constructed as peripheral in their repertoire and analyse their decisions to erase these not only in the visual representation captured by the LP, but also in the resulting discussions through discursive distancing. Such intentional erasures are conceptualised as visual silence.

(Visual) silence

Silence is sometimes overlooked as being a mere acoustic phenomenon resulting from the absence of speech. However, research has highlighted its key role as ‘a legitimate part of the communicative system comparable with speech’, within which silence acts as ‘a dynamic, emergent, and contingent resource deployed strategically in communicative events’ (Jaworski Citation1992, xiii; Citation2016a, 330). On an acoustic and linguistic level, silence can take the form of absence of speech, and it can also emerge on a content level when information is withheld or omitted. As such, it can accomplish a myriad of functions in other modalities, which warrants Jaworski’s conceptualisation of silence as an ‘embodied, multimodal and material’ resource that is a part of social practice, engages with other semiotic resources, can have communicative intent and can express emotions and subject positions (Citation2016a, 330).

Scholarship on silence has also studied its relation to power. As such, silence can be linked to authority and control in asymmetrical power structures, within which some groups are able to influence dominant discourses and silence other, minoritised groups. However, silence can also act as a mechanism of resistance and defiance and in this light, Jaworski (Citation2016b, 441) highlights that there may exist only a fine line between oppressive forms of silence on one hand, and resisting or affirming forms of silence on the other hand. For instance, minoritised groups can use silence as a means of resistance to challenge established power relations. In an educational context, Gilmore (Citation1985) explores this function of silence among students in the US. In classrooms where students are usually positioned in ways that have little power, teachers were found to resort to silence as a means of control and some students used it as a way to defy such power relations.

Drawing on a broad conceptualisation of silence as a communicative resource, several scholars have researched its extension in the visual media and the arts. I build specifically on scholarship on visual silence by Jaworski (Citation1992, Citation1997, Citation2016a, Citation2016b) and Kwiatkowska (Citation1997) to analyse its communicative intent, ability to express emotions and subject positions, as well as negotiate power relations. Jaworski (Citation2016b, 437) describes three main categories in which visual silence can present itself in art: abstract monochrome art with minimal contrast, absences in representational/figurative paintings, and conceptual art that includes metadiscursive or metaphorical references to silence. The LP can be categorised as a representation/figurative visual artefact, although it is important to note that it is not created or analysed for its artistic merit per se. Rather, it serves as a tool to explore speakers’ subjective understandings of their linguistic repertoires. Moreover, I build on Kwiatkowska’s (Citation1997) conceptualisation of visual silence as the absence of an element whose presence is expected. Expanding this understanding beyond artistic paintings, Kwiatkowska illustrates how this can also apply to, for instance, objects and behaviours in everyday situations in which there is a marked absence that is visually identifiable. A recent illustrative example of this could be photographs of empty supermarket shelves during the Covid-19 pandemic, where the absence of goods and products is striking. In what follows, I expand on the definition of visual silence as I apply this notion to LP data.

Language regimes and linguistic repertoires in the Luxembourgish education system

The language portraits analysed in this paper were created by primary school students in Luxembourg who omitted from their drawings one or more languages that they are taught and speak at school. Students in Luxembourg navigate an education system that is often celebrated as a model multilingual education system in the European context (Scheer Citation2017), as 40.5% of curricular time is dedicated to language teaching (Kirsch Citation2018, 40). Simultaneously, this education system has also been shown to contribute to the reproduction of social stratification by disproportionately disadvantaging students with a low socioeconomic status and/or a language minoritised background (SCRIPT and LUCET Citation2016; OECD Citation2016). The educational language regime centres on the three officially recognised languages of the state: Luxembourgish, German and French. At primary school level, German plays an essential role as it is used as the medium of instruction and for teaching basic literacy skills, in addition to being a curricular language subject. French is used in a playful way during Kindergarten and in Year one, while becoming a full language subject towards the end of Year two. Luxembourgish is taught for an hour per week.

While this educational language regime and the corresponding official trilingualism recognised by the 1984 Language Law suggest a stable triglossia, the language situation in this small state in central Europe is more complex. This is connected, in part, to the high linguacultural diversity of the resident population: in 2020, 47.4% of the total 626,100 residents did not have Luxembourgish citizenship (STATEC Citation2020b, 11). The continuous increase of this percentage in recent decades has contributed to shifts in traditional patterns of language use (Horner and Weber Citation2008). Luxembourgish retains its status as a predominately spoken language, and it is used increasingly in writing in the new media (Wagner Citation2013; de Bres and Franziskus Citation2014). German has become the ‘least socially used’ of the three officially recognised languages (Tavares Citation2020, 235). In addition, a large number of cross-border workers contribute to the strong presence of French as a spoken lingua franca, as the majority of these workers come from mainly France and Belgium, with a smaller number coming from Germany (206,000 in total in 2020; STATEC Citation2020b, 15). Varieties of Portuguese are also widely spoken as there exists a large lusophone community, with Portuguese nationals constituting the largest minority group at almost 15% of the total population (STATEC Citation2020a).

This linguistic diversity is also reflected in classrooms: in 2019/20, only 33.7% of all primary school students indicated that Luxembourgish was their most used home language (MENJE and SCRIPT Citation2021, 16). Of primary school students with Luxembourgish citizenship (45.9%), 61.7% reported Luxembourgish as their most used home language (MENJE and SCRIPT Citation2021, 13, 16). For students with non-Luxembourgish citizenship, Portuguese was reported to be the most commonly used home language (39.8%), followed by French (19.6%) (MENJE and SCRIPT Citation2021, 16). Indeed, Romance-languages (e.g. Portuguese, French, Italian) are likely used in the home by a much larger percentage of students regardless of their citizenship, as these languages have a strong presence among the general population in Luxembourg.

Despite the linguacultural diversity of the student population, all students in the Luxembourgish state education system go through German-medium education. This may seem surprising to an outside perspective as German does not feature as a widely used language in many communities or societal domains (Scheer Citation2017; Tavares Citation2020), and may be virtually absent from the extracurricular lives of many students – especially those with a Romance-language background (Weber Citation2009, 200). Moreover, the teaching of highly formal French at school is underpinned by an emphasis on ‘orthographic and grammatical correctness’ that targets ‘conceptual-written perfection’ (Weber and Horner Citation2010, 248; Scheer Citation2017, 92). Yet, there is an important presence of non-standard, vernacular and contact varieties of French spoken in many families, communities and other spaces in Luxembourg that are not built on at school (Weber Citation2009). Thus, there exist disconnections between institutional language regimes, individual linguistic repertoires and wider language practices that can influence how young people in Luxembourg may understand and represent their linguistic repertoires.

Exploring the linguistic repertoires of primary school students in Luxembourg

The data set analysed in this paper is part of a wider study that was conducted with 34 students aged between 10 and 13 who were in their penultimate year of primary school in Luxembourg city (Muller Citation2020). The aim of the study was to explore students’ lived experience of language and language education policy through traditional qualitative research methods (interviews and participant observation) and creative, visual methods (e.g. language portraits). Fieldwork entailed a total of 12 weeks split up into 4 research phases. During each phase, I was present at school to interact with students and observe their day-to-day realities in the classroom, and in each phase, participants could take part in an interview. In the first phase, the interview was based on general questions surrounding their language biographies and served to familiarise students with an interview context. The second research phase was based on language portrait interviews, the third phase used ethnographic chats (Selleck Citation2017), and the final research phase was dedicated to one-on-one interviews that explored participants’ individual perspectives and experiences in more depth.

The data analysed in this paper stems solely from the second, four-week-long fieldwork phase in January 2018 where participants could take part in semi-structured interviews during which they created and discussed a language portrait. I conducted 19 interviews with 33 participants in self-selected constellations of one, two or three students. At the beginning of each interview, I provided participants with instructions that were adjusted and expanded after the first couple of interviews in order to anticipate questions that participants had asked about the task. These instructions aligned with key elements suggested by Busch (Citation2018, 8), and included the following guidelines: ‘This exercise is about drawing your languages into the silhouette. Before you start drawing, it would be good if you could reflect on the different languages in your life: these can be languages that you speak well, or that you don’t speak so well, or where you just know a few words. You can ask yourself: where do I speak them, when, and with whom? And what do these languages mean to me?’ This prompt intentionally included the phrasings ‘your languages’ and ‘languages in your life’ in order to open up a wide space of interpretation. Participants had access to felt pens, colour pencils and a piece of paper with a body silhouetteFootnote1 on it. Some started discussing their drawings during the creative process, while for others I initiated the conversation after students had finished drawing using the prompt ‘explain your portrait and what you have drawn’. The emerging discussion was then guided by further prompts and questions. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Twenty-nine of the total 33 LPs were retained for analysis, as 4 were created in misalignment with the task.

The data set was subject to a multimodal analysis: I first prioritised the discursive data which was analysed thematically following the steps laid out by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). This was then complemented with a compositional analysis of the LP drawings which focused on included and excluded elements, the ways in which elements were represented, and connections to discursive data. The absence of elements from the LPs, conceptualised here as visual silence, was only identified and subsequently explored as a salient theme during the analysis, as it was prominent in eight portraits. It was particularly German and French, the main school languages, that were erased: German was excluded from seven portraits, French from six and Luxembourgish from three. In what follows, instances of visual silence are explored through individual case studies of three focal students. These students, their LP drawings and their discursive explanations were selected because they provide insight into some of the common motivating reasons behind visual silence in this data set, which heavily oriented towards the affective value and lived experience of language more than perceived language competency. Each case study will address the formal, content and functional dimensions of visual silence in the LP. In other words, the analysis will explore how visual silence is achieved in the visual form of the portrait, how it features on the content level where languages have been in- and excluded, and what function it achieves.

Jessica: German and French are super important for school but not for my life

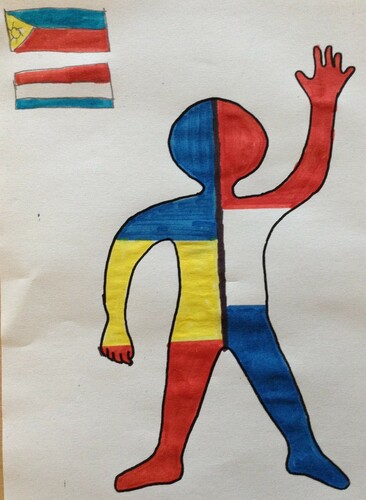

Jessica () divided her portrait through a vertical split, and the two resulting halves include the colours of the Philippine national flag on the left and the Luxembourg national flag on the right. Both flags are also depicted on the top left of the silhouette. Jessica explained that the Philippine flag had a double representational function and symbolised English as one of her home languages as well what she called ‘Filipino’. The latter was connected to her Filipino heritage as Jessica’s mother was born in the Philippines. Although Jessica stated that her proficiency in Filipino is limited to a few words, she felt connected to this language. The right side of the silhouette represents Luxembourgish; Jessica’s other home language.

Regarding the form of visual silence in this LP, it might not be immediately obvious at the surface level that one or more languages were excluded from this drawing as it appears to be fully coloured in. Indeed, the white space of the Luxembourg flag is part of its design and has no symbolic meaning beyond this. Thus, the visual silence only becomes apparent when analysing the content of the portrait from which Jessica excluded German and French. Already at the beginning of the interview, while Jessica was drawing, she shared her plan to only include Luxembourgish and English (and ‘Filipino’):

Jo ech schwätze soss keng Sprooch (.) doheem xxx

Ou? Mee sou an dengem Liewen?

Jo an Däitsch och mee net sou gär

A Franséisch?

Hunn ech guer net gär

An dofir wëlls de déi net molen

Nee

Yes I don’t speak any other language (.) at home xxx

Really? But like in your life?

Yes and German but not too happily

And French?

I don’t like at all

And that’s why you don’t want to draw them

No

(…) An Däitsch a Franséisch sos de wollts de net molen?

Nee well déi sinn net ee vun de wichtege Sproochen an déi sinn net fir mech eng haapt (…) fir mech bedeiten se nëmme fir d'SCHOUL ‘t ass wichteg fir d'Schoul well mäi Papp seet (.) d'Schoul ass wichteg ELO fir dech well ech sinn nach an der Primär dass du an enge gudde Lycée kënns (.) Franséisch probéieren ech ëmmer besser ze kréie well ech och net sou gutt do sinn an ech wëll an enger gudder Schoul ginn (.) jo (.) dofir fannen ech dass (.) Däitsch a Franséisch si mega wichteg fir d'SCHOUL awer net fir m::- mäi fir mäi Liewe sou ongeféier

(…) And German and French you said you didn’t want to draw?

No they are not one of the important languages and for me they are not a main (…) for me they only mean [something] for SCHOOL it is important for school because my dad says (.) school is important for you NOW because I am still in primary so that you get into to a good secondary school (.) French I always try to get better [grades] because I’m also not so good there and I want to go to a good school (.) yes (.) that’s why I think that (.) German and French are super important for SCHOOL but not for m::- my for my life kind of

Thus, Jessica’s lived experience with German and French is marked by the co-existence of a lack of personal, emotional significance and a belief in their instrumental value. Although Jessica discursively reproduces dominant discourses about the instrumental value of German and French for academic progression in the Luxembourgish education system, she also resists these languages and discourses through the visual silence resulting from their absence in the portrait and by discursively distancing herself from them on an emotional level. In doing so, she draws a line between languages that have a highly positive affective value for her and that she emotionally identifies with, and those that lack these qualities. As such, the function of visual silence in this instance can be interpreted as an act of resistance against German and French as school languages.

Regina: German is not something I honestly have from my life

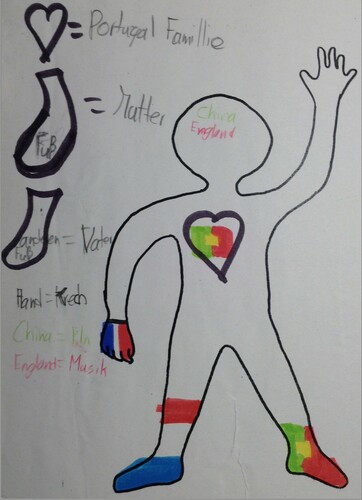

Regina () speaks Portuguese, Luxembourgish and French in the home and used national flags, body symbolisms, strategic placements within the silhouette and written country names in the creation of her portrait. In addition, the key on the left includes explanations and personal associations connected to the various elements in the drawing. As such, Portuguese is represented by the Portugal national flag which features twice, and is explicitly associated with her family and her father specifically. Luxembourgish is represented by the Luxembourg national flag in one foot and is associated with her mother. French is drawn in a hand using the colours of the French national flag and is associated with pre-Kindergarten nursery (Crèche). Finally, ‘China’ and ‘England’ are written inside the head of the silhouette and are connected to film and music respectively.

Contrary to Jessica’s portrait, Regina’s drawing features a lot of white space that is not coloured in. This is not symbolic of the visual silence that will be discussed shortly, but rather enabled the strategic placement of the representational elements within the silhouette. Again, the visual silence becomes apparent on the content level of this LP, where German was excluded. This may appear surprising as German features in the written text in and around the portrait.

In the following extract, Regina explains her motivation to exclude German:

Jo wou ass Däitsch?

Dat hunn ech net?

Wëlls de dat net molen?

Nee dat sinn déi Haptsproochen (…) ech hunn déi Sprooche gemaach net well et déi Haptsprooche si mee well et déi déi ech (.) wéinst eppes vu mengem Liewe kennen. Däitsch ass net eppes wat ech éierlech aus mengem Liewen hunn

Mee vu wou hues du dat dann?

Aus dem (.) just aus der Schoul. Ech hunn dat réischt an der Schoul geléiert. Franséisch hunn ech léiwer aus der Crèche well do hunn ech och meng dräi BFF [best friend(s) forever] Kolleginnen ehm (.) kennegeléiert. (…) et [Däitsch] ass dat wat ech an der Schoul geléiert hunn, net un enger Haptsaach. Zum Beispill Lëtzebuergesch hätt ech och kéinte wechloossen well dat hunn ech an der Spillschoul geléiert mee ech hu Lëtzebuergesch geholl well et ass dat wat ech mat (.) menger Mama méi schwätzen (.) dat ass och vu menger Mama ehm (.) kënnt. Portugal hunn ech egalwéi misse mole well dat ass vu menger Famill (…)

Yes where is German?

I don’t have that?

You don’t want to draw that?

No those are the main languages (…) I put those languages not because they are the main languages but because they are those that I (.) know because of something from my life. German is not something I honestly have from my life

But from where do you have it then?

From the (.) just from school. I only learnt that in school. French I rather have from the Crèche because there I uhm (.) met my three BFF [best friend(s) forever] friends. (…) it [German] is that which I learnt in school, not from a main thing. For example Luxembourgish I also could have left out because I learnt that in Kindergarten but I included Luxembourgish because it is that which I speak more with (.) my mummy because that is also something that uhm (.) comes from my mummy. Portugal I had to draw either way because that is from my family (…)

Regina’s consideration of the hypothetical omission of Luxembourgish provides further insight into the visual silence surrounding German. She explains that she learnt Luxembourgish in a school context just like German, but included the former in her portrait because it has become a main home language that she speaks with her mother, and as a result associates positive emotions and affective value with it. This affective dimension and connections to her personal, extra-curricular life are absent for German. Thus, the notion of space combined with a strong orientation towards the affective dimension of language underpin Regina’s decision to erase German from her portrait. On a functional level, the resulting visual silence symbolises this emotional disconnection.

Elma: I’m not from there

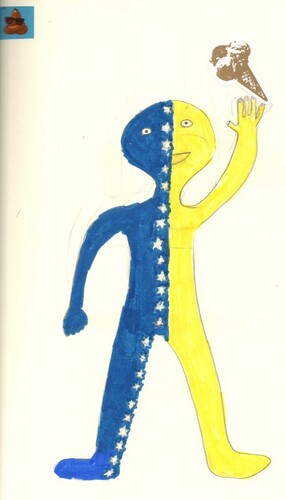

Elma’s () main home language is Bosnian and she also indicated to sometimes speak Luxembourgish with her older sibling. Elma created her own LP body silhouette from scratch and fully covered it with the Bosnia national flag. This LP, unlike the majority of portraits created within the scope of the wider research project, embraces a monolingual and monocultural sense of self.

Prior to starting the drawing process, Elma queried if French had to be included in her portrait:

Muss ech Franséisch dra maachen?

(.) ‘t ass wéi s DU wëlls (.) ne

((hehe))

Ech maache kee Franséisch [dran

[Ech och net

Oder (.) dach (.) oh keng Anung mol kucken

Do I have to put French in?

(.) it’s up to YOU (.) right

((hehe))

I won’t put French [in

[Me neither

Or (.) maybe I will (.) oh I don’t know we’ll see

(…) firwat wollts du de [Bosnesche] Fändel molen?

Ma well meng Eltere vun do [Bosnien] kommen an da kommen ech am Fong OCH vun do also bëssen

Ah sou? Sou bëssen?

((laacht))

Wéi mengs de dat sou bëssen?

Ma wa si do gebuer sinn an allen zwee jo da sinn ech jo och Bosnierin

Mee war s du scho geplënnert?

Nee et ass net dat ech sinn hei gebuer ginn (.) mee am Fong sinn ech Bosnierin well meng Elteren och xxx an jo (.) dat ass meng Haptsprooch an sou eppes

Mee am Fong du kanns jo awer nach aner Sprooche schwätze wéi Bosnesch ne?

Jo mee ehm (.) ech komme jo net vun do an dat ass meng Iwwerleeung also. Wa meng Mamm sou keng Ahunung vun do kéim a mäi Papp vu do da géif ech déi zwee soen also déi zwee Länner

(…) why did you want to draw the [Bosnia] flag?

Well because my parents come from there [Bosnia] and then I actually ALSO come from there well a bit

Oh really? A bit?

((laughs))

What do you mean by a bit?

Well if they are born there both of them yes then I am also Bosnian

But have you moved already?

No it’s not that I was born here (.) but actually I am Bosnian because my parents also xxx and yes (.) that is my main language and something like that

But actually you are also able to speak other languages than Bosnian right?

Yes but uhm (.) I’m not from there and that is my reasoning. If my mum I don’t know came from there and my dad from there then I would say those two well those two countries

Considering the many dimensions of visual silence in the language portrait

After having analysed the language portraits of three focal students, the discussion now brings together the dimensions of form, content and function of visual silence in the LP and concludes with interactional and ethical considerations. The form of visual silence in the LP is its most elusive dimension. In many instances, white spaces in the drawing that have not been coloured in do not represent an intended symbolism. As the above analysis has shown, visual silence can feature in LPs that have been fully coloured in as well as in those that feature white spaces. As a result, it is rather the content dimension of visual silence that is a key characterising feature, as it is on this level that languages are included or erased by the creator of the portrait. As for the functions of visual silence, it firstly serves a negative referential function by concealing information. There is also a strong connection between erased languages and the lived experience of language (Busch Citation2017), as most instances of visual silence in an LP were connected to negative affective values, a lack of personal significance and negative lived experiences (particularly at school).

In discussing interpersonal dimensions of silence, Jaworski (Citation2016a) highlights that this can be connected to power, which is also salient for visual silence in the LP. Indeed, the three focal students featured in this paper used visual silence to challenge and resist languages used at school. Indeed, some participants constructed school as an institutional space in which German (and French) are seen as mere school languages that are recognised only for their instrumental value. At primary school level, German and French play an immensely important role in students’ lives as they are exposed to them on a daily basis. These languages influence students’ educational experience and trajectory, and at primary school level they have no choice over their exposure to German and French or the extent to which they employ them in their schooling. However, in the creation of a language portrait, students used this ‘powerful tool to (…) represent their linguistic identities and language diversity’ (Tabaro Soares, Duarte, and Meij Citation2020, 3), and self-positioned towards German and French with some choosing to reject them as mere school languages that have little to no emotional significance in their personal lives.

My analysis has illustrated that these young people expressed resistance against languages that dominate their daily lives at school and in this light, I argue that visual silence in the LP can be self-empowering. However, it is important to critically engage with the interactional and ethical dimensions of this, as probing into visual silence may break the silence intended by the LP creator. For all instances of visual silence that occurred within the scope of the wider research project, my knowledge of students’ linguistic repertoires resulted from a longer immersive fieldwork period. Thus, while erasures in students’ LPs may not have been immediately visible on the surface level of their drawings to an outside observer, I was able to draw on my background knowledge to identify erased languages. Based on such identifications and in cases where students did not address erasures themselves, I used prompting questions to encourage students to discuss languages they had excluded. However, it is not always possible for researchers to be aware of erasures in the LP. Particularly if researchers are unfamiliar with a participant’s language biography, they may have no expectations about which languages could be included in the portrait. Moreover, the interactional aspects of identifying and probing for visual silence are indicative of power imbalances relating to who can ask questions in research settings, and explicitly addressing erased languages in this way may not be appropriate in all contexts. I argue that my probing for visual silence with this set of young people in this specific research setting expanded the platform within which participants could express their defying stances and negative affective orientations towards erased languages. My own positionality as a sympathetic, active listener who had observed participants’ attitudes towards erased languages at school provided a reinforcing frame to their explanations of such exclusions. However, individuals in other research settings may wish to erase languages and lived experience of language linked to, for instance, traumatic events which can render active probing for them ethically problematic.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have built on an intersection between subject-based approaches to multilingualism, the language portrait as a visual research method and scholarship on (visual) silence to analyse the deliberate erasure of elements in language portraits created by young people in a multilingual educational context. The analysis sheds light on an aspect of LP research that has not been addressed in depth to date by exploring instances of visual silence and discursive distancing, how they are connected to the affective dimension and lived experience of language, and illustrating how visual silence presented a strategy for students to align the visual representations of their linguistic repertoires with their understandings of the latter and their sense of self. In this process, visual silence symbolises a certain degree of emotional distance from linguistic resources which were perceived to be peripheral to such understandings. In many instances, the visual erasure of and discursive distancing from German and French created subversive acts of resistance against these languages which, imposed by the educational language regime, are connected to negative lived experience and negative affective values for some of these young people.

From a methodological viewpoint, my analysis illustrates how the LP as a creative, participant-centred method can be used as a validating and self-empowering tool through which individuals can represent their linguistic repertoire and how they relate to it. Visual silence can offer an important strategy to accomplish this. Moreover, the insights provided in this paper contribute to the body of existing LP research as I not only demonstrate the importance of analysing excluded elements, but also analyse a less often seen monolingual portrait. From a broader theoretical viewpoint, this paper contributes to subject-based approaches to multilingualism, as it highlights the complexity inherent in the linguistic repertoire and its connection to the lived experience of language. This influences how speakers visualise their linguistic resources and experiences in the LP. Moreover, the focus on young people in education is not new in subject-based multilingualism research, and indeed many studies in this area have contributed to making visible the multilingual repertoires and language practices of young people that can often be invisibilised in educational spaces. This paper makes an important contribution to this area of scholarship through its focus on how young people choose to make invisible elements of their multilingualism. Not only in Luxembourg but in other educational contexts as well, visual methods can deepen insights into students’ experiences with language in- and outside of school, which is particularly important in educational contexts marked by inequalities and disconnections between educational language regimes and students’ linguistic repertoires.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, Dr Verena Platzgummer and the participants of the AILA 2021 Symposium 160 ‘Speaking Subjects – Biographical methods in multilingualism research’ for their helpful questions and comments on previous drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Muller

Sarah Muller is an Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Languages and Cultures at the University of Sheffield. Her research interests include educational sociolinguistics, multilingualism, language ideologies and language (education) policy.

Notes

1 Source: www.heteroglossia.net

2 Original interview data in Luxembourgish, English translations are mine. Transcription conventions:

WORD = emphasis

((word)) = descriptions

(…) = content omitted

(.) = brief pause

- = interruption of speech

[ = onset of overlapping speech

xxx = unintelligible speech

:: = elongated sound

References

- Bradley, J., and L. Harvey. 2019. “Creative Inquiry in Applied Linguistics: Language, Communication and the Arts.” In Voice and Practices in Applied Linguistics: Diversifying a Discipline, edited by C. Wright, L. Harvey, and J. Simpson. York: White Rose University Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Busch, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33 (5): 503–523.

- Busch, B. 2017. “Expanding the Notion of the Linguistic Repertoire: On the Concept of Spracherleben — The Lived Experience of Language.” Applied Linguistics 38 (3): 340–358.

- Busch, B. 2018. “The Language Portrait in Multilingual Research: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations.” Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies 2018: 1–11.

- Busch, B. 2021. “The Body Image: Taking an Evaluative Stance Towards Semiotic Resources.” International Journal of Multilingualism 18 (2): 190–205.

- Chik, A. 2019. “Becoming and Being Multilingual in Australia.” In Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words, edited by P. Kalaja and S. Melo-Pfeifer, 15–32. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Chik, A., and S. Melo-Pfeifer. 2020. “What Does Language Awareness Look Like? Visual Methodologies in Language Learning and Teaching Research (2000–2018).” Language Awareness 29 (3–4): 336–352.

- de Bres, J., and A. Franziskus. 2014. “Multilingual Practices of University Students and Changing Forms of Multilingualism in Luxembourg.” International Journal of Multilingualism 11 (1): 62–75.

- Gilmore, P. 1985. “‘Gimme Room’: School Resistance, Attitude, and Access to Literacy.” Journal of Education 167 (1): 111–128.

- Horner, K., and J.-J. Weber. 2008. “The Language Situation in Luxembourg.” Current Issues in Language Planning 9: 69–128.

- Jaworski, A. 1992. The Power of Silence: Social and Pragmatic Perspectives. Thousand Oak, CA: Sage.

- Jaworski, A. 1997. “Introduction: An Overview.” In Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by A. Jaworski, 3–14. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

- Jaworski, A. 2016a. “Silence and Creativity: Re-mediation, Transduction, and Performance.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Creativity, edited by R. H. Jones, 322–335. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jaworski, A. 2016b. “Visual Silence and Non-normative Sexualities: Art, Transduction and Performance.” Gender and Language 10 (3): 433–454.

- Kalaja, P., and A. Pitkänen-Huhta. 2018. “ALR Special Issue: Visual Methods in Applied Language Studies.” Applied Linguistics Review 9 (2–3): 157–176.

- Kirsch, C. 2018. “Young Children Capitalising on their Entire Language Repertoire for Language Learning at School.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 31 (1): 39–55.

- Kramsch, C. 2009. The Multilingual Subject: What Foreign Language Learners Say about their Experience and Why it Matters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kroskrity, P. 2000. “Regimenting Languages: Language Ideological Perspectives.” In Regimes of Language: Ideologies, Polities, and Identities, edited by P. V. Kroskrity, 1–34. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Kwiatkowska, A. 1997. “Silence Across Modalities.” In Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by A. Jaworski, 329–337. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Literat, I. 2013. ““A Pencil for your Thoughts”: Participatory Drawing as a Visual Research Method with Children and Youth.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12 (1): 84–98.

- May, S. 2014. The Multilingual Turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and Bilingual Education. New York: Routledge.

- MENJE and SCRIPT. 2021. Statistiques globales et analyse des résultats scolaires: année scolaire 2019/2020. https://men.public.lu/fr/publications/statistiques-etudes/fondamental/19-20-ef-statistiques-globales.html

- Muller, S. 2020. “The Lived Experience of Language (Education Policy): Multimodal Accounts by Primary School Students in Luxembourg [unpublished].” PhD thesis, The University of Sheffield.

- OECD. 2016. Education Policy Outlook: Luxembourg [online]. Accessed 15 October 2020. http://www.oecd.org/education/Education-Policy-Outlook-Country-Profile-Luxembourg.pdf

- Pavlenko, A. 2013. “The Affective Turn in SLA: From ‘Affective Factors’ to ‘Language Desire’ and ‘Commodification of Affect’.” In The Affective Dimension in Second Language Acquisition, edited by D. Gabryś-Barker and J. Bielska, 3–28. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Pennycook, A., and E. Otsuji. 2014. “Metrolingual Multitasking and Spatial Repertoires: ‘Pizza mo Two Minutes Coming’.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 18 (2): 161–184.

- Scheer, F. (2017). Deutsch in Luxemburg: Positionen, Funktionen und Bewertung der deutschen Sprache. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto.

- SCRIPT and LUCET. 2016. PISA 2015 Nationaler Bericht Luxemburg. Luxemburg: Ministerium für Bildung, Kinder und Jugend, SCRIPT (Service de Coordination de la Recherche et de l’Innovation pédagogiques et technologiques [online]. Accessed 24 September 2020. http://www.pisaluxembourg.lu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/pisarapport2015_de.pdf

- Selleck, C. 2017. “Ethnographic Chats: A Best of Both Method for Ethnography.” Sky Journal of Linguistics 30: 151–162.

- STATEC. 2020a. Affichage de tableau – Population par nationalités détaillées 2011 – 2020 [online]. Accessed 20 January 2021. https://statistiques.public.lu/stat/TableViewer/tableViewHTML.aspx?ReportId=12859&IF_Language=fra&MainTheme=2&FldrName=1

- STATEC. (2020b). Le Luxembourg en chiffres – 2020 [online]. Accessed 18 September 2020. https://statistiques.public.lu/fr/publications/series/luxembourg-en-chiffres/2020/luxembourg-en-chiffres/index.html

- Tabaro Soares, C., Duarte, J. and Meij, M. (2020). “Red is the Colour of the Heart’: Making Young Children’s Multilingualism Visible Through Language Portraits.” Language and Education 2020: 1–20.

- Tavares, B. 2020. “Multilingualism in Luxembourg: (Dis)Empowering Cape Verdean Migrants at Work and Beyond.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2020 (264): 95–114.

- Wagner, M. 2013. “Luxembourgish on Facebook: Language Ideologies and Writing Strategies.” In Social Media and Minority Languages: Convergence and the Creative Industries, edited by E. H. Gruffydd Jones and E. Uribe-Jongbloed. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Weber, J.-J. 2009. Multilingualism, Education and Change. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Weber, J.-J., and K. Horner. 2010. “Orwellian Doublethink: Keywords in Luxembourgish and European Language-in-Education Policy Discourses.” Language Policy 9 (3): 241–256.