ABSTRACT

This paper critically analyses the meaning and use of translanguaging as an inclusive pedagogical strategy in the context of a bilingual deaf education classroom where there are asymmetrical sensorial experiences of being deaf and being hearing, and different access to ‘codified’ (either speech or sign-language) resources. The pedagogical opportunities and constraints of translanguaging are examined through an analysis of the meaning-making resources among deaf and hearing interlocutors in face-to-face interaction. Using two short excerpts from an English class with two deaf pupils, a hearing teacher of the deaf and hearing communication support worker the authors analyse ways in which the modes of image, sound and speech, gesture and signing, gaze, body posture are coordinated in the spatial context for meaning-making. A multimodal and layered analysis of two short turn sequences describes ways in which modes are integrated and coordinated in the spatial layout of the classroom in ways that either facilitate or inhibit inclusive communication. Strategies for the analysis and deployment of multimodal resources that may facilitate the inclusive potential of translanguaging in this interactional context are discussed.

Introduction

Translanguaging and inclusivity in deaf education

The theory and practice of translanguaging has brought to the fore classroom approaches that potentially include, and create a social space for, learners who are deaf with diverse signed, spoken and written language repertoires, and cultural identities (García and Wei Citation2014; Seltzer and Collins Citation2016). This paradigm offers possibilities for an accessible and inclusive learning experience where different signed, spoken and written languages are understood and equally valued (Creese and Blackledge Citation2010); where students are enabled to use their whole linguistic repertoires, and where communication across language asymmetries is facilitated (Mendoza Citation2020).

Whilst the affordances of translanguaging strategies of deaf lecturers has been richly described (Holmström and Schönström Citation2018; Lindahl Citation2015), questions remain about the extent to which translanguaging enables a linguistically equitable and inclusive learning context in deaf education classrooms (De Meulder et al. Citation2019). We argue that these possibilities need to be carefully examined using methodologies that consider the different sensory orientations of learners who are deaf and the sensorial accessibility and sensorial asymmetries (De Meulder et al. Citation2019) of classroom interaction among deaf and hearing learners and teachers. This requires an approach that embraces the modal complexities of the deaf education classroom where the different possibilities of ‘seeing’ and ‘hearing’ need to be effectively coordinated around pedagogical intentions.

In the UK educational context, the majority of teachers of deaf children are hearing. However, as in the setting for this study, many work in bilingual teams with deaf colleagues and are expected to be competent in the use of British Sign Language (BSL). Whilst this situation could be considered suboptimal for some deaf learners, it is nonetheless representative of the current context and, as such, a driver for the study questions around the modal challenges of the classroom, and the consequences of the simultaneous and sequential use of modes for inclusive meaning-making (Lindahl Citation2015; Snoddon Citation2017; Tapio Citation2014).

The communicative context

The communicative challenges of the learning environment for deaf learners in terms of the presentation and availability of information through different modes are well documented (Crandell and Smaldino Citation2000; Sahlén et al. Citation2019). However, less is understood of the pedagogical challenges involved in coordinating different modes to deliver information in a meaningful way.

For many deaf pupils the establishment of visual attention is a prerequisite for sharing information (Dye, Hauser, and Bavelier Citation2008; Matthews and Reich Citation1993). The cognitive demands involved in watching a teacher or interpreter whilst also attending to other visual stimuli, such as whiteboards, practical experiments or textbooks need to be managed in the classroom (Christensen Citation2010). For educators, this entails consideration of the shared communication space, and coordination of the simultaneous and sequential presentation of visual information.

The classroom also presents specific acoustic problems for learners, with or without state-of-the-art listening technologies, in terms of listening and participation (Wheeler, Gregory, and Archbold Citation2004). Issues of noise, reverberation, directionality and distance, even for learners with good listening abilities, can inhibit opportunities to initiate or follow group conversations (Ching et al. Citation2006), and following spoken language delivery over long periods is challenging and tiring (Hornsby et al. Citation2014). In this context, where shared visual attention is a crucial prerequisite for interaction (Tomasello Citation2003), educators must manage the sensory demands of the environment. When visual and auditory distractions become too many, learners are likely to withdraw from participation, and communication breakdowns are common (Martin et al. Citation2011).

To make learning environments and communication more inclusive of learners with different sensorial resources, teachers routinely deploy a range of multimodal resources, including signed, spoken and written languages and ‘blended’ strategies that enhance the visibility of spoken language (Knoors and Marschark Citation2012). The use of multiple modes of communication to facilitate learning and optimize language development are endorsed in the specification for Mandatory Qualifications that govern UK teacher of the deaf training (DfE Citation2018). However, ways in which such resources can be effectively coordinated has not been systematically analysed. Educators, therefore, do not know what works well (or less well) in terms of facilitating inclusive communication and learning.

The research context

The examination of the affordances of translanguaging for creating an inclusive learning environment needs an approach that goes beyond description of the languages and communication strategies in use. Rather, we need to understand more about the quality and efficiency of the interaction and embrace the full multimodality of communication. Such an approach has been exploited in multimodal studies of hearing-hearing interaction that have examined different aspects of classroom interaction such as the teacher’s orchestration of different modes and role of eye gaze in the facilitation of classroom discussion (Bourne and Jewitt Citation2003), as well as the relation between speech and gesture (Lim Citation2019); how children use different modalities of gesture, movement and gaze to build action and participate with classroom peers (Flewitt Citation2006; Kyratzis & Johnson Citation2017); the role of embodied orientation and posture in the accomplishment of turn-allocation and speaker nomination (Bezemer Citation2008; Fasel Lauzon and Berger Citation2015); the significance of pauses and gaps and silences that we might interpret in the deaf education context as the absence of language (Matsumoto Citation2018); the role of touch (Taylor Citation2014) and the importance of classroom layout and the positioning of people and materials (Lim Citation2019).

This work has been increasingly referenced in the translanguaging research signaling the importance of the context of interaction or spatial repertoires as well as the integral role of embodied communication (gesture, eye gaze, nodding, shrugs and smiles) in meaning-making across different biographical and linguistic histories (Creese Citation2017; Otsuji and Pennycook Citation2010). However, this research generally focuses on interlocutors who share the sensorial attributes of hearing and sight.

In deaf-hearing interaction the alignment of resources is more complex and precarious (Kusters et al. Citation2017). Translanguaging research from this perspective has identified ways in which educators integrate different modes in classroom communication. Lindahl (Citation2015), for example, reports ways in which Swedish Sign Language, Signed Swedish (SSS), written Swedish and fingerspelling interact to enable ‘cross-linguistic dialogue’ (Lindahl Citation2015, 137). Other scholars have investigated the simultaneous use of modes such as the use of mouthing, eye gaze and body posture while signing (Vermeerbergen, Leeson, and Crasborn Citation2007) and the use of gesturing while speaking (Kusters Citation2017); the sequential use of modes (signing, mouthing, fingerspelling and pointing) to support text-related learning activities (Tapio Citation2014) and the blended use of modes that serve to make visible the structure of English within a sign language utterance. Whilst all of these strategies can be described as examples of translanguaging in action, blended strategies that enhance the visibility of spoken languages are often not accessible or comprehensible for deaf learners and their use should be critically examined (Scott and Henner Citation2021).

The coordination of embodied multimodal resources (touch, gesture and eye-gaze) is also recognized in interactions between deaf infants and their caregivers (Feldman Citation2012; Lam and Kitamura Citation2010) and detailed multimodal analysis of child and parent interaction has examined how these resources facilitate mutual understanding in the presence of sensorial asymmetries (Adami and Swanwick Citation2019). However, the contingent use of these resources to ensure inclusive communication in the classroom has not been examined. Missing from the research is attention to the learner experience and an examination of the extent to which this is an inclusive experience, that is, how deaf learners access the multimodal content and make ‘meaningful sense of what they see and hear’ (Mayer Citation2016, 41).

Methodology

To examine the inclusivity of meaning-making afforded by translanguaging in deaf-hearing classroom interaction we work with a social semiotic conceptualization of communicative acts as inclusive of all modal resources. This approach brings conceptual tools from multimodal analysis to examine the co-occurring and synchronized use of image, sound, gesture, gaze and body posture (Jewitt Citation2008, Citation2009; Kress and van Leeuwen Citation1996; Norris Citation2004). We undertook a close multimodal analysis of interaction in an educational context among deaf pupils and hearing adults. We observed three sessions of which two were video recorded. We focus here on excerpts from an English class with two deaf pupils (A and B), a hearing qualified teacher of the deaf (T) and a hearing communication support worker (C).

Participants

At the time of recording A and B were aged 11 and in their first year of secondary school. They both have different communication resources that are influenced by their migration trajectories, home situations, profiles of deafness and use of technologies. A is Romanian and came to the UK via Spain approximately three years before the recording. He is severely deafFootnote1 and uses hearing aids. In A’s household mainly Romanian is used, with little English. He is learning BSL and English in school and says that he understands and speaks a little Romanian and a little Spanish. B is Czech Roma and came to the UK aged seven months. B reports using Czech and English at home and she is learning BSL and English in school. She is moderately deaf Footnote2 and uses hearing aids. At the time the data were collected, assessments of the pupils’ home languages had not been undertaken and although it is likely that both have some form of home-sign, this information is not available. The absence of protocols for gathering this information is an issue for practitioners. Both adults are hearing and speak English. They both have proficiency in BSL and Signature qualifications.Footnote3 T has skills to a level for ‘complex language use in all types of social and professional interaction’ equivalent to C1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). C has skills to a level for understanding and using varied BSL in a range of work and social situations. The language choices of the adults in this scenario are driven by the diverse signed and spoken language skills and communication preferences of the learners, and the objective to make the lesson content accessible to the full group.

Data collection

The data below were extracted from a small corpus totaling two hours of recorded video from observed classes. There were also interviews conducted with all participants, as well as sessions where T and C watched the recordings and discussed the use of resources in the classes and the excerpts analysed below. The data that we present are taken from an English class held with participants A and B, T and C. The instructions were given to conduct the lesson as normal, despite the researcher and camera being present. Throughout the observation and recording the researcher was seated outside of the layout shown in and taking notes. We identified two excerpts for analysis from the same English lesson that show the density of multimodal resources deployed by the interlocutors in contrasting communicative situations: a case of the smooth unfolding of the interaction and a case in which the flow of interaction is disrupted. In the data, there were many other activities and communicative practices covered in the classes, for example, a memory game with cards, where touch was a crucial communicative resource. However, most of the other activities did not demonstrate such a density of resources, particularly regarding teaching materials used. The excerpts were shared with T and C, whose reflections on the communication practices and contextual background information supported the analysis process.

Data analysis

Our analysis centres on (1) the multimodal resources used in each participant’s turn, (2) how resources are used in the spatial context of the communication and (3) how the resources are coordinated in this space which enables (or constrain) inclusive communication. We examine turns in two interaction sequences. These are presented through screen shots and tiered transcription. We used the software program ELANFootnote4 for annotation as it allows for fine-grained, multi-tiered annotations and analysis. Automatic time-alignment of annotations and video and frame-by-frame viewing permitted the pinpointing of the simultaneous and sequential deployment of modes used in communication. Transcriptions take place in segmented tiers (which the researchers determine), ours included: voice, gesture, turn, sign, body orientation/movement, facial expression and gaze for each participant. During the analysis process, we worked with a hearing registered BSL-English interpreter and a Deaf BSL instructor, trainer and interpreter. They aided us with the segmentation and transcription of tiers and provided additional professional perspectives on the language use, learning context and classroom set-up.

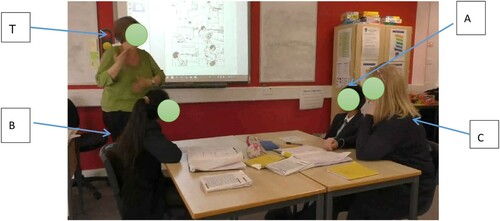

The spatial context: classroom layout and positions

The participants were situated as shown in : T is standing at the board, while A, B and C are sitting along the sides of a table facing each other. As a starting point for this analysis, we identify the communicative opportunities and challenges of this layout and highlight the significance of embodied resources (turning, movement and eye gaze) for inclusivity. B and C can see each other without turning, but both have to look away from each other and sideways to see T and the smartboard. A has to turn away from the board and T to see C. T will need to deploy a range of auditory and visual resources to render her explanations accessible to both pupils. With her back to the board she has sight of A, B and C but will have to turn away from them to refer to the board. Signed interactions will not reach her when she is turned away and her spoken commentary may not reach the pupils when she is facing the board. The placement of T in front of the smartboard means that the pupils can follow her multimodal delivery and refer to the smartboard, when the timing allows, but they cannot look at the materials in front of them, or at each other or at C, and capture the visual aspects of T’s delivery at the same time.

Excerpt 1 analysis: ‘smooth interaction flow’

Excerpt 1 is approximately 40 seconds in length and occurs 16 minutes after recording started and 10 minutes before excerpt 2. Pupils take turns to read aloud written English sentences from the board and suggest the missing words for the gaps. The activity makes use of the smartboard; the pupils do not need to refer to any of the books or papers on the desks in front of them. The character of the exchange requires interaction between pupil and teacher rather than among each other. In this excerpt, A is asked to read ‘I will meet you in _____ an hour’ with ‘half’ being the required word for the gap.

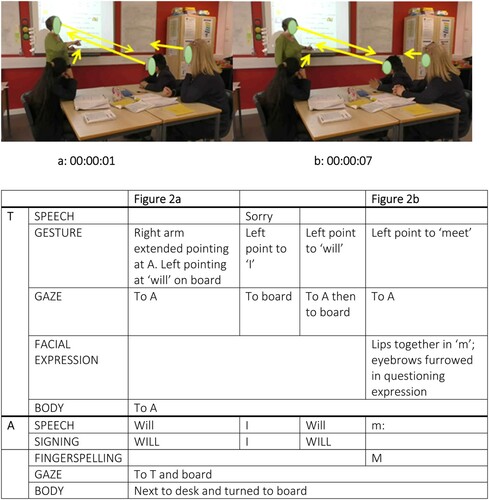

a: T invites A to begin reading word-by-word by extending her right arm to point at A, whilst pointing with her left hand to the word on the board. She begins with ‘will’ and then corrects leftward to ‘I’ at the beginning of the sentence. A follows T’s hand movement along with the board. He simultaneously reads aloud the written English whilst signing and/or fingerspelling the word in question.

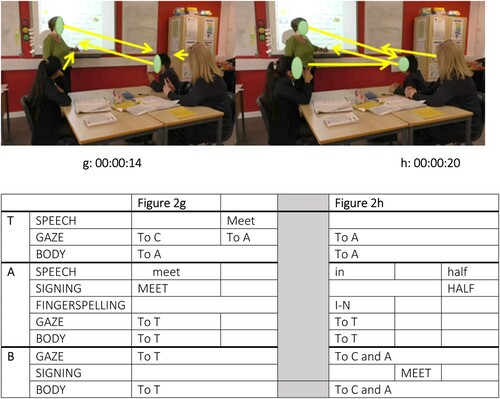

Figure 2. (a): 00:00:01, (b): 00:00:07, (c): 00:00:09 (d): 00:00:12, (e): 00:00:13, (f): 00:00:14, (g): 00:00:14 and (h): 00:00:20.

b: T is pointing at the word ‘meet’. A hesitates and starts with an extended ‘m’ sound (the lengthened sound is represented by ‘:’ in the transcription below). T brings her lips together to confirm that the word begins with lips together making an ‘m’ sound, but furrows her eyebrows in a questioning expression, inviting A to continue the attempt at the word.

c: A fingerspells M-E-E-T whilst simultaneously saying ‘make’. The incongruence of the first attempt by A prompts T to question ‘what’s that’ using speech, whilst retaining a questioning facial expression with eyebrows furrowed and left hand remaining pointing to ‘meet’ on the board. A responds to T’s question by repeating ‘make’ in speech and clarifying by simultaneously signing MAKE.

d: T opens up the activity for B to contribute. She does this by slightly orienting her body towards B and by changing her gaze to look at B, whilst using her voice to ask B if she knows the word. A moves his gaze from T towards B as well. B responds by nodding an affirmation that she knows the word.

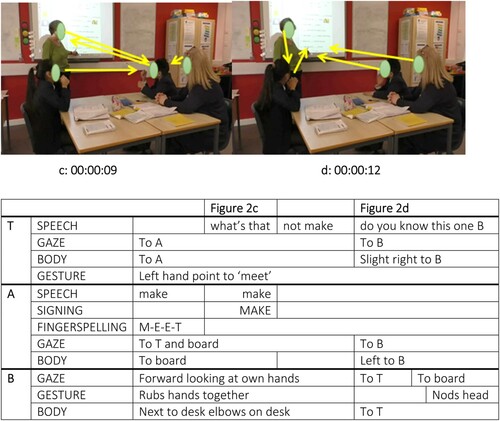

e: C begins to move her body towards A and moves her gaze to him. She then moves her right hand within A’s peripheral vision and waves it horizontally to attract his attention. T asks B to provide the answer using speech ‘what’s it’. B then provides the answer ‘meet’ using speech.

f: A responds to C’s hand wave by turning to look at C who then signs MEET. T’s visual attention is attracted by C signing. She slightly turns her body rightwards towards A and C and gaze towards C and uses speech to reinforce the answer ‘meet’.

Over a 2 second period, the elicitation of the word ‘meet’ is taken up by all the participants using different modes.

g: Almost as soon as A sees C beginning the sign for MEET, he also starts signing MEET whilst turning rightwards and directing his gaze back to T. A and C are nearly simultaneous in their timings of signing MEET. A also uses speech, begun a fraction of a second after he starts the sign MEET, to say ‘meet’. T directs her gaze back to A and confirms his answer of ‘meet’ using speech, and then turns towards the board and moves her hand along to the next word which A continues to read aloud. The excerpt continues (represented by the gray section in the table below) with A reading the remainder of the sentence and simultaneously signing or fingerspelling word-by-word.

h: A continues the end of the sentence ‘in half’. Whilst he is doing this, B turns her body and gaze towards C and A and signs MEET, which resolves the 4-way elicitation of the word that has involved the use of signs, speech, fingerspelling, eye gaze, body movement and gesture.

Resources in meaning-making

In this episode spoken language becomes dominant, especially in relation to the focus on A’s pronunciation. In seeking to work inclusively T makes use of a range of semiotic resources both simultaneously and in sequence, offering her interlocutors a wide range of audio-visual inputs. She combines the use of pointing, gaze and body orientation to direct attention and questions to individuals, simultaneously using speech and signs. When she is pointing towards the text on the board she also adds mouth movement (pursing of lips) to give phonetic cues and she uses facial expression to offer feedback (2a).

C’s contribution is mediated through gestures in A’s eye line to attract his visual attention (2e). The pupils use the resources available to them to contribute to the activity. A combines speech with signs and fingerspelling and B uses speech and signs; through gaze they both signal their focus of attention. Among all of the interlocutors signs, speech, fingerspelling, eye gaze, body movement and gesture are combined as they all differently express MEET (2g).

Spatial context

This layout allows T to manage the interactions using eye gaze and to give multimodal input without losing attention to the board (2a–2d). In this configuration, T can use eye gaze, body movement and pointing to manage the pupil’s attention, select her addressee, provide input in both speech and sign and respond to pupils’ contributions. T’s positioning in this space allows her to involve B by shifting body movement and eye gaze but not lose A’s visual attention. This coordination of resources is potentially challenged in this space when shared attention among the full group is lost as the pupils look away from T in order to attend to each other’s and/or C’s contribution, such as when B offers ‘MEET’ and when C intervenes to support A.

Coordination

The synchronized coordination of resources among the interlocutors facilitates an inclusive outcome. By virtue of the layout, T can see pupils and vise versa and can monitor attention to the text on the board and responses: interactions are synchronized between T and A. When B contributes, this is seen by T and timing is allowed for A to turn for B’s contribution. Further, C’s intervention could have disrupted A’s attention from T, but this is seen by T (again because of the layout and T’s positioning at that specific moment), and so she waits for A to see the sign and turn back before confirming with spoken ‘MEET’ and pointing to text. A resolves this with T, and at the same time, B responds to C, also confirming with the sign ‘MEET’.

Excerpt 2 analysis: ‘disrupted interaction flow’

Excerpt 2 begins 25 minutes after recording started. This took place half-way through the lesson, and the exchange that we analyze is just over 1 minute in length. Pupils are given a picture sequence story that shows a person cooking and then burning her breakfast. The teacher uses the picture story to elicit vocabulary items related to cooking in preparation for a planned writing task. The character of the exchange and task requires A and B to pay attention to and interact with T. Their gaze needs to be turned sideways towards T as well as looking at the picture story that each pupil has on the table in front of them to retrieve elicited information by T.

The excerpt starts as T is explaining the meaning of the term ‘frying pan’ (which is shown in the picture story) and how this differs from other sorts of pans.

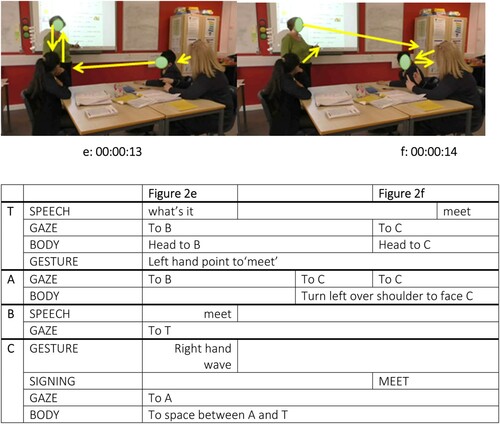

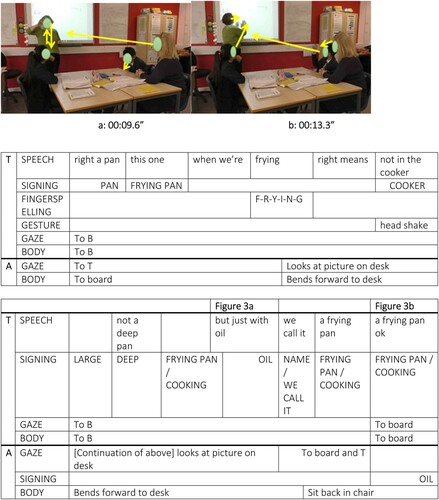

a: T uses a combination of signing, fingerspelling, and speech to explain the use of a frying pan. (As T’s turn is long, it is represented in two transcription tables, one directly beneath the other.) During her turn, she uses the terms ‘oil’ in speech and OIL signed simultaneously. She then repeats with speech ‘frying pan’ and signs FRYING PAN twice with her body orientation and her gaze directed towards B. On the second instance she simultaneously turns back towards the board in preparation for writing ‘frying pan’. A’s gaze is held on the paper from the moment when T fingerspells F-R-Y-I-N-G until nearly the end of T’s turn.

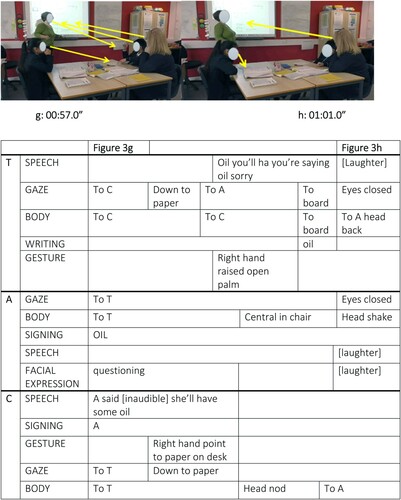

Figure 3. (a): 00:09.6”, (b): 00:13.3”, (c): 00:19.4”, (d): 00:23.5”, (e): 00:26.8”, (f): 00:36.0”, (g): 00:57.0” and (h): 01:01.0”.

b: A moves his gaze up towards T and the board area and moves his body to sit back in his chair. While T is turning towards the board, A begins to sign OIL with the aim of contributing ‘oil’ as a vocabulary item to be written up on the board.

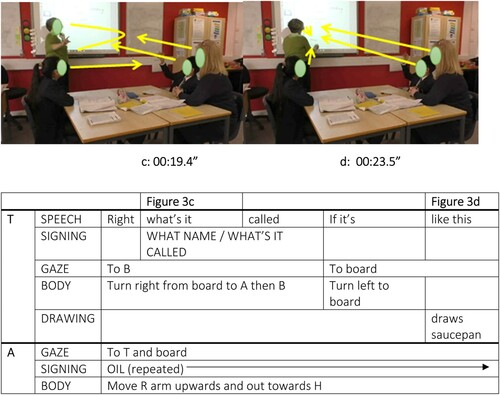

c: T turns quickly from the board towards A and B and then back towards the board while she attempts to elicit the word ‘saucepan’ and by signing WHAT whilst saying ‘what’s it called’. At the same time A is repeatedly signing OIL.

d: T then uses speech ‘if it’s like this like a big pan’ whilst drawing a picture of a saucepan on the board. As she is turned away from the main communication space, due to drawing on the fixed smartboard, it cannot be assumed that either pupil is able to follow her speech. A continues to sign OIL until T completes her drawing of a saucepan on the smartboard. At this point A stops, perhaps realizing that the timing of the interaction is out of sync and that he does not have joint attention with T to achieve his aim.

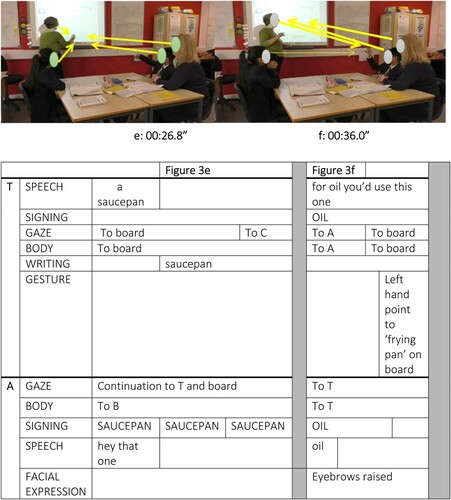

e: During his turn, A signs SAUCEPAN and simultaneously says ‘hey that one’. Yet, he does this whilst T is writing the word ‘saucepan’ on the board so again, because of the layout of the space, her gaze is necessarily to the board. A switches his gaze and body position towards B who initiates an exchange with C. However, A is not involved in their exchange. In this instance, T’s use of multiple modes has succeeded in the aim of eliciting the vocabulary item, however, due to spatial orientation, the answer is not picked up on. T subsequently expands on her explanation of ‘saucepan’. This segment is not transcribed below and is represented by the gray box.

f: Then T’s gaze goes back to A, who signs OIL again and says once ‘oil’. T and A now have established joint attention. T sees A signing OIL. She then states ‘for oil you’d use this one’, simultaneously signing OIL when she says ‘oil’, and subsequently points to the words ‘frying pan’ which she previously wrote on the board.

T then explains the differences between a frying pan and saucepan and completes a drawing of a frying pan on the board, which takes nearly 20 seconds and is represented by the second gray block in the above table.

g: The other participants pick up on the out of sync nature of the interaction. C intervenes towards T by saying ‘A was saying [inaudible] that she [the woman in the picture] will have some oil’. C simultaneously signs A when saying A and then uses her right index finger to point to the woman on the piece of paper in front of A. She thus clarifies the aim of A’s signing OIL. When C says ‘she’ll have some oil’, A takes one more turn signing OIL again whilst gazing at T, then down at the paper, and then back at T again.

h: The excerpt finishes with T writing ‘oil’ on the board and with T, C and A laughing, acknowledging the miscommunication occurred and subsequently resolved. Only B and C have gaze lines in h below as A and T’s eyes are closed whilst laughing.

Resources in meaning-making

T makes use of a range of semiotic resources, both simultaneously and in sequence, to pursue her pedagogical aims; these include gaze, pointing, face expression and body orientation, combined with speech, signing, fingerspelling, writing and drawing. However, in this case, the inclusivity is disrupted when the coordination of modes within the visual space breaks down.

Spatial context

Although the spatial layout is similar with excerpt 1 the character of this activity requires the pupils to refer to the picture in front of each of them on the table as well as to T and the vocabulary list on the board to their side (3a). T is actively writing on the board as the pupils contribute (3b). This serves a pedagogical purpose but necessitates frequent shifts in body orientation (particularly for T) and gaze (for all participants). This compromises T’s ability to visually monitor the pupils’ attention and, when she is turned away, the pupils’ signed contributions do not reach her (3d) and her simultaneous spoken expression does not reach them (3d).

Coordination

These spatial challenges, combined with the sensorial asymmetries and conflicting demands on the interlocutors, lead to ‘dis-synchrony’ in the interaction and turn-taking. We see this when A gazes down at the paper (3a) and misses out on much of T’s multimodal rendering of ‘frying pan’, including her simultaneous use of ‘oil’ (spoken) and OIL (signed). This results in A being out of sync with the new vocabulary item (‘frying pan’) and its explanation. He assumes that the lesson is still following the format of contribution and writing on the board and seeks to have OIL ‘oil’ written up. Only later does A realize that his contribution is out of sync with T’s actions. Later in the sequence, a similar glitch in synchronization reoccurs when A’s response and contribution of SAUCEPAN and ‘hey that one’ does not reach T as she turns to write on the board. The actions are eventually brought back into sync by the intervention of C who has had a more comprehensive view, and hearing, of the whole interaction and uses speech, sign and gesture to capture T’s attention and reinforce A’s contribution. This enables the communication between A and T to be reestablished as T writes ‘oil’ on the board. A and T recognize the un-synching of turns, and T re-syncs the interaction to move forward.

Discussion and conclusions

These findings reveal the complexities of orchestrating the linguistic and embodied components of translanguaging in action, and what is involved in the context of a mixed group of interlocutors where there are sensory asymmetries and different languaging preferences among learners. The educational setting of this interaction espouses a bilingual approach that includes the use of BSL and spoken/written English according to individual pupil repertoire but a bilingual classroom pedagogy – that is inclusive of all learners – presents specific modal challenges and opportunities.

The range of semiotic resources used by T, including the use of signed and spoken languages, are intentionally inclusive of the two deaf learners and their different communication preferences. Signed language and spoken language are used in conjunction with written and visual resources and embodied strategies to convey meaning, and to take and offer turns in the interaction.

However, for all interlocutors to be able to visually follow the unfolding of the interaction, the use of space has to be coordinated with the simultaneous and sequential use of multimodal resources. These intersemiotic correspondences (Lim Citation2019) are intrinsic to inclusive communication where the character of the activity requires shared attention. This is achieved when the interaction is teacher-centered, that is, when T can orchestrate and maintain the pupil’s visual attention. However, the inclusive possibilities of the use of different resources by T are not optimized where the multiple demands on the pupil’s visual attention are not synchronized.

Because of the different modalities of production, all participants are capable of simultaneous production of signs (in the semiotic sense) normally associated with two different languages, that is, spoken English and BSL. These possibilities for simultaneity, especially in the presence of writing activity, on the one hand, provide multiple opportunities for deaf learners to access the target content but equally provide multiple representations of meaning that need to be attended to and be connected.

Inclusivity breaks down when the use of modes is not sufficiently coordinated according to the possibilities and constraints of the space, and the sensory needs of participants. Reasons for these glitches can, in part, be explained by the different sensorial orientations of the hearing and deaf interlocutors. The alignment or synching of modes may be generally less intuitive for hearing than for deaf teachers. This difference has been found in the early development literature in comparisons between deaf and hearing caregivers (Traci and Koester Citation2010) but has not been systematically compared in the classroom context. The power relations among the deaf and hearing interlocutors (Poza Citation2017) may also contribute to misfires where teacher communication decisions, dominated by a reliance on spoken language, are less than contingent on pupil-initiated contributions (De Meulder et al. Citation2019).

If we understand translanguaging to be a natural component of bilingual classroom pedagogy that is hospitable to the full communicative repertoires of learners, meaning-making practices associated with this framework that include the integration of different modes in classroom communication need to be problematized in the context of deaf education. Translanguaging in this context does not guarantee an inclusive experience for learners, and indeed can give rise to confusion and a fragmented language experience if the semiotic resources are not sufficiently coordinated in both space and time around the sensorial asymmetries of the interlocutors. At best, translanguaging can provide the ‘understructure’ (Prada Citation2019) for inclusive practices that then need to be enacted with an understanding of the sensory conditions of the interaction.

This work underlines the insights into meaning-making and communication that a multimodal analysis can deliver. However, extending this work to encompass interaction that presents sensory and communication asymmetries, brings conceptual and methodological challenges in terms of annotation, accessible reporting and the representation of signed languages, positioning and objects, alongside transcription of spoken language. We echo the need for software programs that can support the complexity of analysis and forms of presentation of data deploying across multiple dimensions and parameters (Adami and Swanwick Citation2019; Lim Citation2019; Swanwick Citation2016).

In practice, whilst we do not anticipate teaching professionals engaging in a similarly detailed process, a lot could be learnt from the close observation of even short interactional episodes to map out the classroom layout, positions and resources of the participants, analyse the auditory and visual attention demands of the setting and the coordination possibilities of these intersecting resources. In particular, the three analytical dimensions we have identified, that is, (1) resources used in meaning-making, (2) spatial context and (3) coordination through time, could provide a navigational aid also for teaching professionals’ observation of and reflection on their own practices in the classroom.

The conceptualization and implementation of translanguaging opens up inclusive communication possibilities for deaf education classroom interaction but at the same time exposes complex challenges in terms of the coordination of multiple modes. The layout of the communicative space combines with the participants’ sensory asymmetries to determine in complex ways which multimodal configurations at every given moment include or exclude participation in the interaction. By moving away from a focus on linguistic behavior to embrace the multimodal and multisensorial aspects of communication, this work highlights the impact of sensory asymmetries on inclusivity and how we might fine tune the quality and efficiency of interaction to bring this about.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participants, as well as the deaf and hearing BSL interpreters who worked with us during the analysis stage. We gratefully acknowledge the funding received from Leeds Arts and Humanities Research Institute and the School of Education, University of Leeds in supporting the Signs beyond Borders Project, during which this research was carried out.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ruth Swanwick

Ruth Swanwick is Professor of Deaf Education at Leeds University in the School of Education. Her research activities encompass childhood deafness, language and learning, inclusive and bilingual education and teacher development.

Samantha Goodchild

Samantha Goodchild is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Multilingualism at the Center for Multilingualism in Society across the Lifespan (MultiLing), University of Oslo, Norway. Her research interests include multilingualism and the relationship between language, ideologies and space, and collaborative research. She is co-founder and co-director of Language Landscape.

Elisabetta Adami

Elisabetta Adami is Associate Professor in Multimodal Communication at the University of Leeds, UK. Her research specialises in social semiotic multimodal analysis with a current focus on issues of culture and translation. She has published on sign-making practices in place, in digital environments, and in face-to-face interaction. She is editor of Multimodality & Society and leads Multimodality@Leeds.

Notes

1 A person with a severe hearing loss will not be able to hear the speech of others without hearing technology.

2 A person with a moderate hearing loss will find it difficult to hear soft sounds and quiet speech without hearing technology.

3 Signature is an awarding body for deaf communication qualifications in the UK.

4 ELAN is a computer programme created by the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. More information and the programme itself can be downloaded here: https://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/elan/. (Wittenburg et al. Citation2006).

References

- Adami, E., and R. Swanwick. 2019. “Signs of Understanding and Turns-as-Actions: A Multimodal Analysis of Deaf–Hearing Interaction.” Visual Communication 18: 1470357219854776.

- Bezemer, Jeff. 2008. “Displaying Orientation in the Classroom: Students’ Multimodal Responses to Teacher Instructions.” Linguistics and Education 19: 166–178.

- Bourne, Jill, and Carey Jewitt. 2003. “Orchestrating Debate: A Multimodal Analysis of Classroom Interaction.” Literacy 37: 64–72.

- Ching, Teresa Y. C., Emma van Wanrooy, Mandy Hill, and Paola V. Incerti. 2006. “Performance in Children with Hearing Aids or Cochlear Implants: Bilateral Stimulation and Binaural Hearing.” International Journal of Audiology 45: S108–S112.

- Christensen, K. M. 2010. Ethical Considerations in Educating Children Who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Crandell, Carl C., and Joseph J. Smaldino. 2000. “Classroom Acoustics for Children with Normal Hearing and with Hearing Impairment.” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 31: 362–370.

- Creese, A. 2017. “Translanguaging as an Everyday Practice.” In New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education (Bilingual Education & Bilingualism 108), edited by B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, and Å W, 1–9. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2010. “Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching?” The Modern Language Journal 94 (1): 103–115.

- De Meulder, M., A. Kusters, E. Moriarty, and J. J. Murray. 2019. “Describe, Don't Prescribe. The Practice and Politics of Translanguaging in the Context of Deaf Signers.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (10): 892–906.

- DfE. 2018. Specification for Mandatory Qualifications for Specialist Teachers of Children and Young People who are Deaf. London: Crown copyright.

- Dye, Matthew W. G., Peter C. Hauser, and Daphne Bavelier. 2008. “Visual Attention in Deaf Children and Adults.” In Deaf Cognition Foundations and Outcomes, edited by M. Marschark and P. Hauser, 252–263. New York; Oxford: University Press.

- Fasel Lauzon, Virginie, and Evelyne Berger. 2015. “The Multimodal Organization of Speaker Selection in Classroom Interaction.” Linguistics and Education 31: 14–29.

- Feldman, Ruth. 2012. “Parent–Infant Synchrony: A Biobehavioral Model of Mutual Influences in the Formation of Affiliative Bonds.” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 77 (2): 42–51.

- Flewitt, Rosie. 2006. “Using Video to Investigate Preschool Classroom Interaction Education Research Assumptions and Methodological Practices.” Visual Communication 5: 25–50.

- García, Ofelia, and Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Pivot.

- Holmström, I., and K. Schönström. 2018. “Deaf Lecturers’ Translanguaging in a Higher Education Setting. A Multimodal Multilingual Perspective.” Applied Linguistics Review 9 (1): 90–111.

- Hornsby, Benjamin W. Y., Krystal Werfel, Stephen Camarata, and Fred H. Bess. 2014. “Subjective Fatigue in Children with Hearing Loss: Some Preliminary Findings.” American Journal of Audiology 23: 129–134.

- Jewitt, Carey. 2008. “Multimodality and Literacy in School Classrooms.” Review of Research in Education 32 (1): 241–267.

- Jewitt, Carey. 2009. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Knoors, Harry, and Marc Marschark. 2012. “Language Planning for the 21st Century: Revisiting Bilingual Language Policy for Deaf Children.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 17 (3): 291–305.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 1996. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Kusters, Annelies. 2017. “Gesture-based Customer Interactions: Deaf and Hearing Mumbaikar's Multimodal and Metrolingual Practices.” International Journal of Multilingualism 14 (3): 283–302.

- Kusters, A., M. Spotti, R. Swanwick, and E. Tapio. 2017. “Beyond Languages, Beyond Modalities: Transforming the Study of Semiotic Repertoires.” International Journal of Multilingualism 14 (3): 219–232.

- Kyratzis, Amy, and Sarah Jean Johnson. 2017. “Multimodal and Multilingual Resources in Children's Framing of Situated Learning Activities: An Introduction.” Linguistics and Education 41: 1–6.

- Lam, Christa, and Christine Kitamura. 2010. “Maternal Interactions with a Hearing and Hearing-Impaired Twin: Similarities and Differences in Speech Input, Interaction Quality, and Word Production.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 53 (3): 543–555.

- Lim, Fei Victor. 2019. “Investigating Intersemiosis: A Systemic Functional Multimodal Discourse Analysis of the Relationship Between Language and Gesture in Classroom Discourse.” Visual Communication 20: 1–25.

- Lindahl, Camilla. 2015. “Signs of Significance: A Study of Dialogue in a Multimodal, Sign Bilingual Science Classroom (English).” (Stockholm: Stockholm University PhD thesis.

- Martin, Daniela, Yael Bat-Chava, Anil Lalwani, and Susan B. Waltzman. 2011. “Peer Relationships of Deaf Children with Cochlear Implants: Predictors of Peer Entry and Peer Interaction Success.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 16 (1): 108–120.

- Matsumoto, Yumi. 2018. “Challenging Moments as Opportunities to Learn: The Role of Nonverbal Interactional Resources in Dealing with Conflicts in English as a Lingua Franca Classroom Interactions.” Linguistics and Education 48: 35–51.

- Matthews, T. James, and Carol F. Reich. 1993. “Constraints on Communication in Classrooms for the Deaf.” American Annals of the Deaf 138 (1): 14–18.

- Mayer, Connie. 2016. “Rethinking Total Communication: Looking Back, Moving Forward.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies in Language, edited by Marc Marschark and Patricia Elizabeth Spencer, 32–44. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Mendoza, A. 2020. “What Does Translanguaging-for-Equity Really Involve? An Interactional Analysis of a 9th Grade English Class.” Applied Linguistics Review 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2019-0106.

- Norris, Sigrid. 2004. Analyzing Multimodal Interaction: A Methodological Framework. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Otsuji, E., and A. Pennycook. 2010. “Metrolingualism: Fixity, Fluidity and Language in Flux.” International Journal of Multilingualism 7 (3): 240–254.

- Poza, L. 2017. “Translanguaging: Definitions, Implications, and Further Needs in Burgeoning Inquiry.” Berkeley Review of Education 6 (2): 101–128.

- Prada, J. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Translanguaging in Linguistic Ideological and Attitudinal Reconfigurations in the Spanish Classroom for Heritage Speakers.” Classroom Discourse 10 (3-4): 306–322.

- Sahlén, Birgitta, Kristina Hansson, Viveka Lyberg-Åhlande, and Jonas Brännström. 2019. “Spoken Language and Language Impairment in Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Children: Fostering Classroom Environments for Mainstreamed Children.” In Evidence-based Practices in Deaf Education, edited by Harry Knoors and Marc Marschark, 129–148. New York, NY: University of Oxford Press.

- Scott, J. A., and J. Henner. 2021. “Second Verse, Same as the First: On the use of Signing Systems in Modern Interventions for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children in the USA.” Deafness & Education International 23 (2): 123–141.

- Seltzer, K., and B. Collins. 2016. “Navigating Turbulent Waters: Translanguaging to Support Academic and Socioemotional Well-being.” In Translanguaging with Multilingual Students, edited by T. Kleyn and O. Garcia, 140–160. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

- Snoddon, Kristin. 2017. “Uncovering Translingual Practices in Teaching Parents Classical ASL Varieties.” International Journal of Multilingualism 14 (3): 303–316.

- Swanwick, R. 2016. Languages and Languaging in Deaf Education: A Framework for Pedagogy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Tapio, Elina. 2014. “The Marginalisation of Finely Tuned Semiotic Practices and Misunderstandings in Relation to (Signed) Languages and Deafness.” Multimodal Communication 3 (2): 131–142.

- Taylor, Roberta. 2014. “Meaning Between, in and Around Words, Gestures and Postures - Multimodal Meaning-Making in Children's Classroom Discourse.” Language and Education 28 (5): 401–420.

- Tomasello, Michael. 2003. Constructing a Language: A Usage-based Theory of Language Acquisition. London: Harvard University Press.

- Traci, Meg Ann, and Lynne Sanford Koester. 2010. “Parent-Infant Interactions: A Transactional Approach to Understanding the Development of Deaf Infants.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language and Education, edited by Marc Marschark and Patricia Elizabeth Spencer, 2nd ed., 200–213. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Vermeerbergen, Myriam, Lorraine Leeson, and Onno A. Crasborn. 2007. “Simultaneity in Signed Languages: A String of Sequentially Organised Issues.” In Simultaneity in Signed Languages: Form and Function, edited by Myriam Vermeerbergen, Lorraine Leeson, and Onno A. Crasborn, 1–25. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Wheeler, Alexandra, Susan Gregory, and Sue Archbold. 2004. Supporting Young People with Cochlear Implants in Secondary School. London: RNID.

- Wittenburg, P., H. Brugman, A. Russel, A. Klassmann, and H. Sloetjes. 2006. “ELAN: A Professional Framework for Multimodality Research.” Proceedings of LREC 2006, fifth International conference on language resources and evaluation.