ABSTRACT

Traditionally bilingual Maltese school populations are increasingly linguistically diverse, due to intensified migration flows. To shed light on central issues to be addressed by policy makers, school administrators, researchers and teacher trainers, collective beliefs of Maltese primary school teachers regarding their conceptual understanding and pedagogical actions concerning multilingualism are investigated. Through the application of Q methodology and focus group interviews, data from twenty-one in-service teachers from six different colleges were collected. Using inverted factor analysis, three factors were extracted for each of the components (understanding and pedagogy). Detailed narratives for each group of collective teachers’ beliefs were described and supplemented with teachers’ validating comments. Findings indicate that having a positive understanding of multilingualism does not necessarily imply positive pedagogical beliefs and vice versa. In Malta’s inherently bilingual education system, teachers tend to accept and welcome children’s languages in their classrooms and encourage the learning of additional languages. However, possibly due to a lack of adequate training on the subject, there is scepticism regarding whether and how to effectively draw on multilingualism in the classroom. Additionally, the need arises for more teacher autonomy and agency to make decisions regarding classroom language practices, and for a more comprehensive Maltese national language education policy.

Introduction

Occupancy and colonisation have given the Maltese islands a long history of multilingualism. In the last century, a language conflict was brought to the forefront as Italian, English and Maltese struggled for official recognition (Brincat Citation2017). This conflict, known as the Language Question, resulted in Malta’s current bilingual state, with Maltese and English being recognised as the official languages of the country in 1934 (Brincat Citation2011), alongside Maltese Sign Language, which gained its official status in 2016 (Paggio and Gatt Citation2018). Both Maltese and English are spoken by 95% and 85% of the population respectively (Camilleri Grima Citation2016) and are present in all domains in society, including administration, the media and education (Vella Citation2013). Camilleri Grima (Citation2016) describes this successful bilingual reality as an intrinsic necessity to value the Maltese language ‘for identity and self-preservation, while adopting English for instrumental reasons in order to fit in with the rest of the world’ (2). However, Malta’s linguistic ecology is more complex. The island’s inhabitants were influenced by a range of other languages, such as Arabic, Latin, Sicilian, French and Italian to name but a few (Brincat Citation2017). With Italy being an important economic partner and a majority of Maltese terms being of Italian or Sicilian origin, Italian is an optional, but highly popular subject in school and is still widely spoken by the Maltese, even if less so than before the turn of the century (Caruana Citation2013). More recently, Malta’s linguistic contexts were further diversified by the considerable influx of migrants from all over the world (Caruana, Scaglione, and Vassallo Gauci Citation2019). Bringing their own languages, cultures, beliefs and traditions, immigrants have transformed predominantly monocultural yet bilingual workplaces and classrooms into increasingly multicultural and multilingual ones (Paris and Farrugia Citation2019).

Ever since the beginning of the country’s formal education in the nineteenth century, the Maltese education system has been at least bilingual (Camilleri Grima Citation2013). As English gains importance when students progress through the system (Caruana, Scaglione, and Vassallo Gauci Citation2019), academic teaching in primary schools is carried out in Maltese and English in equal measures. In addition, everyday communication amongst students, teachers, administration staff, parents and non-academic staff as well involves the extensive use of both Maltese and English, albeit to different respective degrees. Not only are all teachers at primary school level required to teach Maltese and English and therefore expected to be fluently bilingual, but their ‘ingrained bilingual habits’ (Camilleri Grima Citation2013, 565) make Malta a particularly intriguing case of an inherently bilingual education system. Nearly 30 years ago, Camilleri (Citation1995) already illustrated how codeswitching, understood as alternating between multiple languages in the context of a single conversation, was extremely common in Maltese schools to increase the interaction between teachers and students and promote active participation in class. Today, at least in overt terms, bilingualism in the Maltese education system seems not anymore the combination of clearly separated languages without any inferences between them, but is rather conceptualised as a more fluid communicative translingual practice, where speakers potentially possess one non-compartmentalised linguistic system (García and Otheguy Citation2020). In terms of policy, while the previous curriculum still represented a strict Maltese-English language allocation approach which encouraged language separation and discouraged codeswitching, the current National Curriculum Framework for All (NCF, Ministry for Education and Employment Citation2012) shifts the focus onto the content being learned, irrespective of the language used, as long as it facilitates student learning. On the same lines, Malta’s official language policy for the early years clearly endorses the important role of language mediation in facilitating comprehension and knowledge construction (Ministry for Education and Employment Citation2016). The document strongly promotes bilingual and multilingual development as it encourages young students to adopt positive attitudes towards Maltese and English as well as other languages. The same desire to promote foreign language learning is also clear in the aforementioned NCF (Ministry for Education and Employment Citation2012) in order to sustain ‘the high competency levels in foreign language teaching and learning developed by young people in Malta during the compulsory schooling’ (7). To this end, it aims to give the opportunity to primary school children to study at least one other language apart from Maltese and English in an informal and semi-formal manner by introducing a Foreign Language Awareness Programme (FLAP), which encourages an appreciation towards other languages and cultures and helps students to make an informed decision regarding the language to study in secondary school.

Over the past few years and within a relatively short period of time, the total number of non-Maltese students in pre-primary, primary and secondary formal education was seen to more than double, from 4.5 per cent in 2013 up to 9.7 per cent in 2017 (National Statistics Office Citation2018). Based on the long history of language contact in Malta on a societal level (Brincat Citation2017) and the fact that all Maltese are brought up as functional bilinguals, a common expectation in the Southern European state is that teachers are relatively comfortable with an increased linguistic diversity in their classrooms and newer multilingual practices in educational settings are being conceptualised. As a matter of fact, studies carried out in other countries seem to indicate that multilingual teachers are more favourably disposed towards multilingualism (Calafato Citation2019). With regard to the increased linguistic diversity due to migration trends, recent research has however found that Maltese teachers feel unsure about translingual practices (Panzavecchia and Little Citation2020) and do not possess the necessary skills to adapt their teaching activities to the needs of migrant students (Caruana, Scaglione, and Vassallo Gauci Citation2019).

It seems as if the relatively recent addition of migrant languages, has put Maltese-English bilingualism out of balance and the reasons for teachers’ insecurity about how to handle multilingualism in classrooms might be multifaceted. On the one hand, language mediation practices seem to be commonly accepted with respect to the official languages of schooling. On the other hand, the monitored situation for other languages present in the classroom potentially still represents schools in the sense of ‘effective institutions of social erasure and control’ (García and Otheguy Citation2020, 18), which focus rather on plurilingualism as opposed to translanguaging. In addition, the concept of multilingualism is theoretically not completely understood due to its complexity. To contribute with new knowledge about multilingualism in bilingual education, the current investigation examines not only multilingualism’s positive aspects, but also some of the perennial challenges faced by learners and teachers of different languages (Ticheloven et al. Citation2019) in increasingly diverse settings. Acknowledging such complexity in line with the fissures in the additive and monoglossic view of multilingualism described by García and Otheguy (Citation2020) increases our understanding of the opportunities and difficulties regarding this dynamic phenomenon for individuals and societies (Lundberg Citation2019a) and in particular for teachers acting as key policy arbiters (Menken and García Citation2010) through their active decision-making (Borg Citation2003) in the classroom. The way they personally experience an increasingly linguistically diverse classroom context and negotiate the use of language(s) for communication and learning, makes teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism fascinating and compelling. In the present study, teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism are separated into (1) a conceptual and (2) a pedagogical component. The study aims to investigate collective beliefs in both components and sheds light on central challenges and issues, that needed to be addressed by policy makers, school administrators, educational researchers and teacher trainers. Hence, the following research questions are asked:

How do Maltese primary school teachers understand the concept of multilingualism?

What are Maltese primary school teachers’ pedagogical beliefs about multilingualism?

A sociocultural approach to teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism

Teachers’ decisions are understood to be the result of conscious and subconscious thinking processes, influenced by teachers’ personal and professional past experiences (Lundberg Citation2019a; Panzavecchia and Little Citation2020), present situations and future aspirations. Educators negotiate their pedagogical practices based on their preferences and understandings of central concepts. In the present research project, no differentiation between knowledge and beliefs was made, as these mental constructs are often impossible (Pajares Citation1992) and unnecessary to distinguish. For reasons of simplicity, the term teachers’ beliefs will be used in the remainder of this paper.

The (re)formation of teachers’ beliefs is a dynamic process, where teachers’ pre- and in-service education can play an influential role (Gorter and Arocena Citation2020). Borg (Citation2011) argues that teacher training can help educators to become more aware of their beliefs, review and revise them, and eventually put them into practice. Tillema (Citation1997) adds that teachers’ beliefs should be critically discussed in light of alternative subjective theories in teacher education. Lundberg (Citation2019b) for instance, found that teachers who were given professional training on multilingualism had more positive views towards multilingual students and pluralistic approaches in language teaching. However, according to an analysis carried out by the European Commission (Citation2019), more than half of all in-service teachers in Malta are not motivated to attend CPD courses or are unable to do so because of other responsibilities.

An inconsistency between policy and practice, and between beliefs and practice does not apply exclusively to the Maltese context. While many teachers believe that multilingualism should be promoted and that minority students should be encouraged to use and continue to develop their native languages (De Angelis Citation2011), they seem to fall back on rather monolingual beliefs when teaching (Portolés and Martí Citation2020). In addition to a lack of skills mentioned above, contextual aspects, such as external pressures by authorities to strictly separate languages, greatly influence and potentially hinder teachers from adopting practices that reflect their beliefs and local policies. In other words, taking into consideration the socio-cultural environment is of prime importance for better understanding the dynamic and reciprocal processes between teachers’ beliefs and practices. Despite the awareness of local school traditions and peer influence among teachers, in particular regarding novice teachers seeking to substantiate their newly adapted beliefs with personal experience, research in the field has only showed a limited focus on a collective perspective to teachers’ beliefs (England Citation2017). In the present study, individuals might be the source of information, but our methodological choices allow the investigation of collective beliefs and emergent patterns in the selected participant sample. Consequently, and in line with a sociocultural turn of teacher cognition (Li Citation2020) that places more focus on the ‘complex socially, culturally, and historically situated contexts’ (Johnson Citation2006, 239) in which teachers act and make decisions, the present paper sees teachers’ beliefs as a situated and socially shared concept. Therefore, the paper aims to gain a better understanding of dominant collective beliefs about multilingualism from the perspective of primary school teachers in Malta.

Materials and methods

For the purpose and aims of the present study, Q methodology (henceforth Q; Brown Citation1980) was chosen. This increasingly popular approach in educational research (Lundberg, de Leeuw, and Aliani Citation2020) empirically measures the lived experiences and opinions of individuals (McKeown and Thomas Citation2013) and aims to capture shared perspectives amongst a purposefully-selected group of participants (Watts and Stenner Citation2012). Relatively recently, Q has been used to investigate multicultural teacher education (Yang and Montgomery Citation2013) and preschool teachers’ perspectives on linguistic diversity in the United States (Sung and Akhtar Citation2017) and teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in Sweden (Lundberg Citation2019a) and German-speaking Switzerland (Lundberg Citation2019b). While Q methodology cannot be used to generalise in a statistical sense, it does provide researchers with an approach that aims at uncovering the patterns of perspectives about a certain phenomenon within a particular context.

Participants (P-set)

Twenty-one teachers from primary schools in different geographical areas of Malta were recruited using non-probability sampling. The schools’ student populations varied with regard to the percentage of learners with a migrant background and were numbered accordingly (see ). Most participating teachers were female and could be regarded as novice teachers with less experientially informed beliefs due to their limited teaching experience of five years or less (Basturkmen Citation2012).

Table 1. Demographic overview of participating teachers.

Instrument construction

In line with the two research questions, two sets of statements, also known as Q samples, were developed (see Appendix). As this study is a replication study of those by Lundberg (Citation2019a, Citation2019b), Q samples applied in Sweden and Switzerland were used as a baseline. They were however culturally-tailored to reflect the Maltese cultural and linguistic context. Informal meetings and discussions with teachers helped decide on the most appropriate terminology to avoid ambiguity in relation to multilingualism. For instance, items regarding the provision of language support for students and the criteria for this such entitlement were added. Another example was the term ‘multilingual students’ used in Lundberg (Citation2019a, Citation2019b), which was changed to ‘migrant students’, when a specific reference to students who have relatively recently come to Malta was intended. As a result of these careful adaptations, certain items were removed and others added with regard to the baseline Q samples.

As Q provides participants with the language they require to label their beliefs (Ernest Citation2001), a pilot study involving the ranking exercise and focus groups with two teachers helped with reviewing the clarity of the statements. Moreover, the appropriateness of the instructions given to the participants regarding the ranking was tested. The result of this process was a first sample of 41 statements aimed at discovering participants’ conceptual understanding of multilingualism and a second sample of 34 statements related to participants’ view on pedagogical practices concerning multilingualism.

Data collection

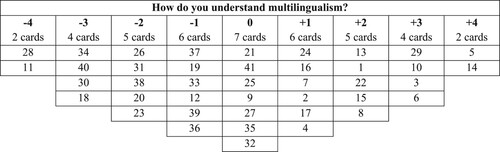

The first author visited each college and collected data in a face-to-face manner. First, the study was introduced and informed consent was collected from all participants. Second, demographic information from all the participants was gathered (see ). Thirdly, for each component, participants were presented with physical item cards and a distribution grid with a scale ranging from −4 (strongly disagree) to +4 (strongly agree). For each value, the card limit was indicated as shown in . Then, participants were instructed to rank-order all items of the first component onto the first distribution grid allowing them to visualise their viewpoint with regard to the first research question. The procedure, which forces participants to carefully and critically reflect on their beliefs, was repeated for the second component. Finally, the participants were asked to transfer the reference numbers for each card onto an A4 replica chart. In order to provide richer data and build a more detailed narrative of why the participants ranked the statements the way they did, and their general views on the statements they felt most strongly about, as well as to reduce researcher bias, three focus group sessions with two participants each were held following sorting.

Data analysis and interpretation

The collected data was then inserted into the software programme KADE (Banasick Citation2019), where correlations between individual Q sorts were calculated. Centroid factor analysis clustered similar Q sorts and three factors in each component (understanding and pedagogy) were retained for rotation based on statistical considerations (explained variance and eigenvalue). Following Varimax rotation, all twenty-one Q sorts were found to load significantly on either one of the three factors for the understanding component, and twenty out of twenty-one Q sorts loaded significantly on either one of the three factors for the pedagogy component. To load significantly at the p < 0.01 level, sorts had to reach a certain similarity with at least one factor (+/− 0.40 in the first component, +/− 0.44 in the second component). Hand-flagging these defining sorts confirmed the three-factor solution in both components. To facilitate the interpretation of the condensed data reached through factor analysis, factor arrays (), consisting of the merged and weighted responses for all the participants loading on a particular factor was created for all factors in both components.

To arrive at a holistic description of each factor, factor arrays, top and bottom items and distinguishing statements were used for within factor interpretation. In a second step, across factor interpretation, mostly drawing on differences between pairs of factors, was used to further enrich the descriptions. Finally, comments from focus groups were used to validate our interpretations and add another layer of qualitative information.

Results

The three factors which emerged from the analysis of the understanding component are described first, followed by the three factors from the pedagogy component. Each factor is labelled according to the factor number and the component (e.g. Factor 1U). Factor descriptions are followed by a section on consensus across factors. To facilitate reference to the Q samples in the Appendix, statement numbers and their ranked position in the respective factor array (e.g. 5: +4) are provided in the descriptions. ()

Table 2. Demographic and statistical overview of significant loadings per factor in both components.

Understanding component

Factor 1U

The group of ten participants who loaded on this factor consists mostly of teachers who are in frequent contact with migrant students. This is the only factor where all the participants are University graduates with a teaching degree. Also, the three participants having a Master’s level qualification in education loaded on this factor.

These participants tend to agree that multilingualism is the key to effective communication (5: +4) and that someone who can communicate in more than two languages is multilingual (14: +4). They strongly believe in multilingualism as bringing personal and social advantages, including that it broadens their personal horizon (29: +3), develops verbal skills (3: +3) and produces cognitive advantages (6: +3). They also believe that multilingual students have better chances for employment (10: +3) and that multilingualism does not hinder the communication of social values (30: −3). These participants neither believe that multilingualism leads to negative changes in school (28: −4), nor see it as frustrating (23: −2). Neither do they believe that multilingual students must speak all of their languages fluently (18: −3), because they do not switch between different independent language systems (40: −3). In fact, nine out of these ten participants stated that they can speak three or more languages and specified the levels at which they speak them, thus, positioning themselves as multilingual speakers even though they do not speak all their languages at the same level of proficiency.

Factor 2U

All four participants in this group have less than five years teaching experience and none of them had ever attended professional development courses on language teaching or multilingualism. Two significantly loading participants on this factor do not have a teaching qualification.

These participants strongly believe that multilingualism in the classroom can be frustrating (23: +4). This may be the reason why they also think that students with a migrant background should be competent in English and/or Maltese (26: +3). They see some benefits to multilingualism, including that it is the key to effective communication (5: +3) and provides possibilities for contacts (8: +4). They also believe that students with a migrant background are not ashamed of using their native language (34: −4). However, Factor 2U does not see benefits from mother tongues being spoken at home (27: −3) and strongly believes in a bilingual education context, as illustrated in the following quote:

Get them used to speaking in Maltese and in English only, that’s what [our superiors] tell us. Don’t talk to him in Italian, for example. So, he’ll learn. I have a learning support assistant who speaks Italian, I tell her don’t talk to him in Italian. (Female Teacher from College 5)

Factor 3U

Three out of the seven participants who loaded on this factor teach in colleges with lower percentages of learners with a migrant background. Their understanding of multilingualism seems to fall between that by Factors 1U and 2U.

These teachers agree that multilingual students have a bigger vocabulary (13: +4) and that monolingually-raised children can become multilingual (25: +3). They also believe that multilingual students do not necessarily speak all of their languages fluently (18: −3). Unlike the teachers in Factor 1U, they do not see the benefits of multilingualism as a priority, but they do consider multilingualism to be a resource when learning a new language (1: +3), as well as being a valuable resource for society (10: +1). Moreover, they could not decide on whether multilingualism in the classroom is frustrating (23: 0), potentially because they do not think that multilingual students have problems at school (20: −4). However, they are quite certain that multilingualism is not discussed enough in education (31: −3).

Pedagogy component

Factor 1P

This group of eight participants consists of all those without much contact with students with a migrant background in their schools. All except one are University graduates with a teaching degree, and most described themselves as being bilingual with minimal knowledge of languages other than Maltese and English.

These participants tend to agree that they treat every student the same, regardless of their mother tongue (20: +4) and that language support in Maltese and/or English should be provided based on the students’ competence level, regardless of their citizenship (14: +4). They believe that students with a migrant background need additional support to learn Maltese (4: +3), but are unsure whether Maltese students and students with a migrant background should learn Maltese separately (8: 0). They also strongly believe that students with a migrant background should not be dispensed from language classes (1: −3) or from the FLAP (22: −4). Moreover, they disagree that students should be discouraged from using their mother tongues in class (30: −3). With regards to policy issues, the teachers who loaded on this factor firmly believe that multilingualism is a right at school (9: +3) and that schools should have access to multilingual material (11: +3). They are also convinced that a ‘Maltese and English only’ policy is not the way forward for local state schools (29: −3). Rather, both Maltese and students with a migrant background should be competent in more than two languages (12: −4).

Factor 2P

All three participants who loaded on this factor are teachers in schools with a large migrant student population and have a University teaching degree or equivalent. However, none has attended courses on language teaching or multilingualism in the past three years.

These participants strongly believe that students with a migrant background need additional support to learn Maltese (4: +4) and those who speak neither Maltese nor English should take a language preparatory course before attending regular classes (24: +4), because a common language is important (3: +3). Like participants loading on Factor 1P, they believe that language support should be provided based on students’ level of competence, rather than citizenship:

I had a student who was born in Malta because her mother is Russian and her father is Maltese, but they are separated. So, this girl lives with her mother, she never sees her father and she speaks in Russian at home. So, she should have had support for Maltese. Just because she has a Maltese ID card, it doesn’t mean she has to learn Maltese with the Maltese students. (Female Teacher from College 1)

Why should schools change? If you go to France, they will tell you to abide by their rules. We are too accommodating in Malta. (Female Teacher from College 1)

In line with Factor 2 in the first component, Factor 2P indicates a certain level of fear with regards to reports written against them for using more than one language in class:

Once I had a report that mentioned that I said ‘head, thorax and abdomen’ in English in a Maltese lesson. I should have shown them a picture and told them in Maltese. (Female Teacher from College 1)

As this factor does not want migrant students’ mother tongues to be spoken in class (30: +3), it can be concluded that the above quote only applies to the official languages of the country: English and Maltese.

Factor 3P

Most participants loading on this factor work in schools with a large migrant student population and have less than six years’ teaching experience, many of them without a teaching related degree.

These participants strongly agree that a common language is important (3: +4) and that students with a migrant background who speak neither Maltese nor English should take a language preparatory course before attending regular classes (24: +4). According to these teachers, Maltese students and students with a migrant background should learn Maltese separately (8: +3) because the latter need additional support (4: +3). They strongly believe that students with a migrant background should be allowed to use their mother tongues in the classroom (30: −3) and are not convinced that language teaching should be carried out entirely in the target language (17: 0). However, they do not see the need to be informed when students are taking mother tongue lessons outside school hours (33: −3).

They do not believe that a ‘Maltese and English only’ policy is the way forward for local state schools (29: −3). Rather, students with a migrant background should not be dispensed from the FLAP (22: −4), even though trilingualism should not be imposed on everyone (6: −4). In general, Factor 3P seems to advocate for more systemic changes with regard to multilingualism:

Schools should change their way of teaching. We are catering for Malta of twenty years ago. The teacher is expected to change but not the school. There are still limited resources and time … . The school needs to change the approach. (Female Teacher from College 1)

Consensus across factors

Statistically, the first and the third factor in each component are the most populated ones and share a relatively high intercorrelation, indicating that there exists a considerable consensus between these two factors. However, even across all factors, there seem to be collective beliefs subjectively true for all participating teachers. One of the strongest consensuses for the understanding component was the disagreement with the statement that someone who speaks both Maltese and English is considered to be monolingual (11: −4 in all factors). Interestingly enough, the participants did not believe that speakers of Maltese and English are multilingual either. In fact, most participants seemed to understand multilingualism as two plus a minimum of one more language:

If two, bilingual. If more, multilingual. (Female Teacher from College 5 loading on Factors 2U and 1P)

Bilingual? If you know just one and you learn another then you’re not multilingual. (Male Teacher from College 2 loading on Factor 1U)

This resonates also with Maltese primary school teachers’ view of students with a migrant background as being in the process of becoming multilingual, as they position them as early speakers of both Maltese and English:

In truth, I don’t think they have any difficulties with learning English … . Even Maltese. I had children who didn’t know them and were high achievers in them. If there is a will, they can learn anything. (Female Teacher from College 5 loading on Factors 2U and 1P)

The participants in all three factors of the understanding component also agreed that multilingualism is not discussed often enough in education (31: −2, −3, −3 respectively). This is supported by numerous comments from the focus group interviews referring to teachers’ lack of training about multilingualism and students with migrant backgrounds.

We are not given any training on how to teach a foreign language. (Female Teacher from College 1 loading on Factors 1U and 3P)

We never even spoke about it once in four years. (Female Teacher from College 5 loading on Factors 2U and 1P)

In the pedagogy component, all factors were in agreement that migrant students need additional support to learn Maltese (4: +3, +4, +3 respectively) and that such language support in Maltese and/or English should be provided based on the students’ level of competence, regardless of their citizenship (14: +4, +2, +2 respectively). In addition, factors show consensus that migrant students should not be dispensed from the FLAP (22: −4, −3, −4 respectively), indicating the belief that awareness of additional languages should continue to be encouraged, even if the students are already multilingual.

Discussion

The present Q methodological study uncovered a variety of teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. Similar to those in Sweden (Lundberg Citation2019a), primary school teachers in Malta loaded on rather positive factors (1U/1P), where benefits of multilingualism are acknowledged and a multilingual environment with dynamic language use is seen to have welcoming effects on individuals and the society. Teachers’ reported endorsement of multilingualism and linguistic diversity in the classroom has also been found in several other contexts (Lundberg Citation2019b; Portolés and Martí Citation2020; Sung and Akhtar Citation2017). Further, the study reported somewhat negative or critical factors (2U/2P) that advocate for language separation and oppose changing their practices in line with newer local policies and greater linguistic diversity. Finally, a third pair of factors (3U/3P) represents a combination of the previous factors in the respective components and adopts a more pragmatic stance, centring around the needs of their students, whilst also understanding that support needs to be given in situations where students speak different languages and difficulties in communication arise.

In contrast to the Swedish context (Lundberg Citation2019a) no clear connection between the local contexts (with regard to the percentage of migrant student population) and factor allocations could be drawn. Instead, loading on particular factors described in this study rather seems a question of qualification, training and teaching experience. For instance, Factor 2U only consists of teachers with less than six years of experience and no participation in CPD courses concerning the topic. In the absence of extensive experientially informed beliefs (Basturkmen Citation2012), their more critical stance might be grounded in their own experiences as students in schools or deep-seated monolingual and monoglossic traditions in the socio-cultural environment. Here, the influence of older and more experienced peers on the one hand and authorities on the other one, could have been highly impactful. However, the more experienced teachers that decided to participate in the present study and those with a higher teacher qualification (e.g. Bachelor’s or Master’s degree) showed a more positive understanding of multilingualism.

A crumbling monoglossic view of multilingualism asks for more training

Confirming previous findings from Malta (Caruana, Scaglione, and Vassallo Gauci. Citation2019; Panzavecchia and Little Citation2020), participants in the present study seem to lack the necessary skills to adapt their teaching to the needs of learners with a migrant background. During focus group discussions, several teachers mentioned the effects of lacking support, training and human resources on their teaching practice with regard to increasingly diverse student populations. This claim stands however in contrast to low response rates regarding the attendance of CPD courses in Malta (European Commission Citation2019).

As teachers’ beliefs are largely resistant to change once they have been ingrained (Pajares Citation1992), teacher training needs to be particularly effective (Borg Citation2011; Portolés and Martí Citation2020). As shown in Lundberg (Citation2019b), an intense and mandatory CPD led to an overwhelmingly positive understanding of multilingualism in German-speaking Switzerland. Similar to the Swiss context, where the second component showed a high degree of insecurity regarding pedagogical actions, Maltese teachers particularly ask for more practical information, for example about pedagogical translanguaging. Here, the study by Gorter and Arocena (Citation2020) illustrates how in-service teachers in the Basque Country were able to adapt, at least temporarily, more positive beliefs of translanguaging approaches after only four days of lectures.

While more training for teachers is certainly vital, the fact that participating teachers expect a report written against them for applying translanguaging strategies, suggests that the bilingual Maltese school system covertly still follows a monolingual and monoglossic tradition (García and Otheguy Citation2020). Even though the language allocation policy in the former curriculum may have often been violated by Maltese teachers, as it is frequently done in other similar contexts (Menken and García Citation2010), and local educational language policies have now shifted towards a more holistic view of multilingualism, some teachers are still fearful of drawing on a variety of languages during their lessons. Potentially important in that respect is the majority of novice teachers in the present study. Compared to their more experienced colleagues, they might be less secure and confident to practically enact the described paradigmatic shift.

On being and becoming multilingual

Consensus across factors was found regarding terminology regarding multilingualism and related concepts in the Maltese context. The participants agree that all students in Malta are bilingual or in the process of becoming so, irrespective of their nationality. However, the assumption that possessing a Maltese ID card is indicative of a child who can speak Maltese (and English) at a high proficiency level is considered a disservice to the student by participants in the study. The fact that some children are eligible for the available services but others with the same needs are not, simply based on citizenship, is considered to be highly unjust by teachers. It is understood that the needs of foreign speakers of Maltese (and English) would be different to the needs of native speakers. When adding the specific needs of newly arrived migrants to the different needs of those with more confidence and knowledge in the language(s) of schooling (Ticheloven et al. Citation2019), it becomes clear how complex translanguaging pedagogy’s comprehensive and purposeful integration into Maltese school culture is and what demands on teachers this involves.

In general, it seems as if collective teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in Malta are largely in line with plurilingual education described as ‘kinder and more gentle than the monolingual educational practices of the past’ (García and Otheguy Citation2020, 23). However, the ultimate goal might still be native-like proficiency in the official languages of the country, Maltese and English, with competence in any other language, including migrant students’ mother tongues, as subordinate additions. In that matter, it seems the findings from Malta are in line with those from the European nation state Sweden (Lundberg Citation2019a) and also from multilingual Switzerland (Lundberg Citation2019b).

Implications for practice

The results discussed in this study allow the presentation of several implications for practice. Firstly, teachers reported a lack of support or appropriate training opportunities for teachers when teaching linguistically diverse classes. The variety of collective teacher beliefs outlined in this study should lead to more targeted short- and long-term support and a general adaptation of teacher in- and pre-service education programmes. Secondly, similar to other publications from the same context (Caruana, Scaglione, and Vassallo Gauci Citation2019; Panzavecchia and Little Citation2020), results here confirm the absence of professionally-trained staff to help teachers translate theory into practice. Consequently, more pre- and in-service teacher training related to multilingualism and language learning needs to be established. Thirdly, teachers need to be granted more autonomy and agency to make decisions, which allow a change of focus from strict language separation in an additive to a more holistic view of multilingualism (García and Otheguy Citation2020), and to make use of practices such as translanguaging which allow students to draw on all available linguistic repertoires. As this shift inevitably leads to tensions between traditional and more progressive stances, teachers need to be trusted and allowed to experiment (Lundberg Citation2019b). Finally, the present study clearly illustrates the increasing need for a more comprehensive national language education policy in Malta closely in line with supra-national ones, for example those by the Council of Europe. Such a policy would need to take into account the varying levels of student diversity in different schools in order to meet the diverse needs of all students attending mainstream schools and in particular those with a migrant background. To further raise the awareness about multilingualism and linguistic diversity among Maltese teachers and eventually lead to fewer inconsistencies between policy and practice, teachers ought to feel heard and seen during the creation of such a policy. Lundberg, de Leeuw, and Aliani (Citation2020) suggest Q methodology as a suitable tool for a participatory approach to policy formation that should lead to an increased sense of responsibility and accountability for a policy among the various groups of stakeholders, not least that of teachers.

Limitations and future research directions

The results of this study only reveal the collective beliefs of twenty-one primary school teachers in Malta. Thus, it is not the intention to make generalisations about teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism. However, the results show that there seem to be similar viewpoints about multilingualism in Malta as in other contexts, indicating some level of transferability. When recruiting participants for the study, less interest was shown by teachers in schools with a low migrant learner population. Teachers having over ten years’ experience, whose beliefs might correspond more clearly with their actual teaching practices (Basturkmen Citation2012), were also difficult to recruit. Even though focus groups were added to Q methodology to add more depth to the data, the present study did not investigate the practical manifestations of the reported beliefs, which could be explored by carrying out classroom observations. Further, a similar study could be carried out amongst secondary school teachers to explore if teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism change in different levels of the Maltese school system.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to investigate multilingualism from the point of view of primary school teachers in Malta who personally experience linguistic diversity on a daily basis in the classroom. Q methodology revealed collective teachers’ beliefs illustrating a general trend towards an openness to having children from multilingual backgrounds in Maltese classes (Factors 1U/1P and 3U/3P). Showing the diversity of views in this inherently bilingual education system, a minority of teachers view multilingualism as the cause of frustration and lack of communication in the classroom (Factors 2U/2P). Those teachers feel restricted by fears of being reprimanded by their superiors, both within the local schools and the education department, for implementing novel teaching methods in line with the philosophical underpinnings of translanguaging. Consequently, schools ought to be given more autonomy to make decisions based on their own individual needs, whilst teachers should be provided with adequate training and trusted with more agency to adapt to the needs of the students in their class. Finally, an up-to-date national language education policy, possibly created through a participatory approach, might close the gap between Maltese teachers’ beliefs and their practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rebecca Camenzuli

Rebecca Camenzuli is a primary school teacher. She has a Master’s Degree in Access to Education from the University of Malta, specialising in Culturally Responsive Education.

Adrian Lundberg

Adrian Lundberg is assistant professor of Education at Malmö University in Sweden. His research focuses on educational issues at the crossroads of multilingualism, equity and policy.

Phyllisienne Gauci

Phyllisienne Gauci is resident academic at the Faculty of Education, University of Malta. Her research interests revolve around second language acquisition, teacher training, language mediation and multilingualism.

References

- Banasick, S. 2019. “KADE: A Desktop Application for Q Methodology.” Journal of Open Source Software 4 (36): 1–4.

- Basturkmen, H. 2012. “Review of Research Into Correspondence Between Language Teachers’ Stated Beliefs and Practices.” System 40: 282–295.

- Borg, S. 2003. “Teacher Cognition in Language Teaching: A Review of Research on What Language Teachers Think, Know, Believe, and do.” Language Teaching 36: 81–109.

- Borg, S. 2011. “The Impact of in-Service Teacher Education on Language Teachers’ Beliefs.” System 39: 370–380.

- Brincat, J. M. 2011. Maltese and Other Languages: A Linguistic History of Malta. St. Venera: Midsea Books.

- Brincat, J. M. 2017. “The Language Question and Education: A Political Controversy on a Linguistic Topic.” In Yesterday's Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, edited by R. G. Sultana, 161–181. San Gwann, Malta: Publishers Enterprises Group.

- Brown, S. R. 1980. Political Subjectivity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Calafato, R. 2019. “The non-Native Speaker Teacher as Proficient Multilingual: A Critical Review of Research from 2009–2018.” Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics. Revue internationale De Linguistique Generale 227: 102700.

- Camilleri, A. 1995. Bilingualism in Education: The Maltese Experience. Heidelberg, Germany: Julius Groos Verlag.

- Camilleri Grima, A. 2013. “A Select Review of Bilingualism in Education in Malta.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16 (5): 553–569. doi:10.1080/13670050.2012.716813.

- Camilleri Grima, A. 2016. “Young Children Living Bilingually in Malta.” Lingwistyka Stosowana 17 (2): 1–13.

- Caruana, S. 2013. “Italian in Malta: A Socio-Educational Perspective.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16 (5): 602–614. doi:10.1080/13670050.2012.716816.

- Caruana, S., S. Scaglione, and P. Vassallo Gauci. 2019. “Multilingualism and the Inclusion of Migrant Learners in Maltese Schools.” In Teacher Education Matters: Transforming Lives … Transforming Schools, edited by C. Bezzina, and S. Caruana, 330–343. Msida, Malta: University of Malta.

- De Angelis, G. 2011. “Teachers’ Beliefs About the Role of Prior Language Knowledge in Learning and how These Influence Teaching Practices.” International Journal of Multilingualism 8 (3): 216–234.

- England, N. 2017. “Developing an Interpretation of Collective Beliefs in Language Teacher Cognition Research.” TESOL Quarterly 51: 220–238. doi:10.1002/tesq.334.

- Ernest, J. M. 2001. “An Alternate Approach to Studying Beliefs About Developmentally Appropriate Practices.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 2 (3): 337–353.

- European Commission. 2019. “Education and training monitor country analysis”. Malta.

- García, O., and R. Otheguy. 2020. “Plurilingualism and Translanguaging: Commonalities and Divergences.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1080/13670050.2019.1598932.

- Gorter, D., and E. Arocena. 2020. “Teachers’ Beliefs About Multilingualism in a Course on Translanguaging.” System 92: 102272.

- Johnson, K. E. 2006. “The Sociocultural Turn and its Challenges for Second Language Teacher Education.” TESOL Quarterly 40 (1): 235–257.

- Li, L. 2020. Language Teacher Cognition: A Sociocultural Perspective. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-51134-8.

- Lundberg, A. 2019a. “Teachers’ Beliefs About Multilingualism: Findings from Q Method Research.” Current Issues in Language Planning 20 (3): 266–283. doi:10.1080/14664208.2018.1495373.

- Lundberg, A. 2019b. “Teachers’ Viewpoints About an Educational Reform Concerning Multilingualism in German-Speaking Switzerland.” Learning and Instruction 64, doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101244.

- Lundberg, A., R. R. de Leeuw, and R. Aliani. 2020. “Using Q Methodology: Sorting out Subjectivity in Educational Research.” Educational Research Review 31: 100361. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100361.

- McKeown, B., and D. B. Thomas. 2013. Q Methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781483384412.

- Menken, K., and O. García. 2010. Negotiating Language Policies in Schools: Educators as Policymakers. New York: Routledge.

- Ministry for Education and Employment. 2012. A National Curriculum Framework for All.

- Ministry for Education and Employment. 2016. A Language Policy for the Early Years in Malta and Gozo.

- National Statistics Office. 2018. https://nso.gov.mt/en/Pages/NSO-Home.aspx

- Paggio, P., and A. Gatt. 2018. “Introduction.” In The Languages of Malta, edited by P. Paggio, and A. Gatt, 1–6. Berlin, Germany: Language Science Press.

- Pajares, M. F. 1992. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Educational Research: Cleaning up a Messy Construct.” Review of Educational Research 62 (3): 307–332.

- Panzavecchia, M., and S. Little. 2020. “Language use in the Primary Classroom: Maltese Teachers’ Views on Multilingual Practices.” EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages 7 (1): 108–123. doi:10.21283/2376905X.11.184.

- Paris, A., and M. Farrugia. 2019. “Embracing Multilingualism in Maltese Schools: From Bilingual to Multilingual Pedagogy.” Cahiers Internationaux de Sociolinguistique 16: 117–140. doi:10.3917/cisl.1902.0117.

- Portolés, L., and O. Martí. 2020. “Teachers’ Beliefs About Multilingual Pedagogies and the Role of Intial Training.” International Journal of Multilingualism 17 (2): 248–264. doi:10.1080/14790718.2018.1515206.

- Sung, P., and N. Akhtar. 2017. “Exploring Preschool Teachers’ Perspectives on Linguistic Diversity: A Q Study.” Teaching and Teacher Education 65: 157–170. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.004.

- Ticheloven, A., E. Blom, P. Leseman, and S. McMonagle. 2019. “Translanguaging Challenges in Multilingual Classrooms: Scholar, Teacher and Student Perspectives.” International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–24. doi:10.1080/14790718.2019.1686002.

- Tillema, H. H. 1997. “Stability and Change in Student Teachers’ Beliefs.” European Journal of Teacher Education 20 (3): 209–212. doi:10.1080/0261976970200301.

- Vella, A. 2013. “Languages and Language Varieties in Malta.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16 (5): 532–552. doi:10.1080/13670050.2012.716812.

- Watts, S., and P. Stenner. 2012. Doing Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method and Interpretation. Los Angeles and London: SAGE Publications.

- Yang, Y., and D. Montgomery. 2013. “Gaps or Bridges in Multicultural Teacher Education: A Q Study of Attitudes Toward Student Diversity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 30: 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.10.003.

Appendix

Statements for understanding component

Multilingualism is a resource when learning a new language.

The mother tongue is the person’s preferred language across most domains.

Multilingualism develops verbal skills.

Multilingualism increases the capacity to use effective reading strategies.

Multilingualism is the key to effective communication.

Multilingualism produces cognitive advantages.

Multilingualism allows new perspectives on surroundings.

Multilingualism provides possibilities for contacts.

Multilingual students are more flexible in their thoughts.

Multilingual students have better chances for employment.

Someone who speaks both Maltese and English is considered to be monolingual.

Students who speak neither Maltese nor English as a first language have difficulties with learning these languages.

Multilingual students have a bigger vocabulary.

Someone who can communicate in more than two languages is multilingual.

Multilingual students are a valuable resource for society.

Multilingual students show greater acceptance for other cultures.

Multilingual students can support monolingual students in language classes.

Multilingual students can speak all their languages fluently.

Someone who learns one or more additional languages as an adult is considered to be multilingual.

Multilingual students often have problems at school.

Multilingual students can observe their own culture from different perspectives.

Multilingualism provides possibilities to participate in an international study and work context.

Multilingualism in the classroom can be frustrating.

Multilingualism is more than just verbal language use.

Monolingually-raised children can become multilingual.

Migrant students’ parents need to be competent in English and/or Maltese for successful collaboration between school and parents.

Migrant students benefit from their mother tongue being spoken at home.

Multilingualism leads to negative changes in school.

Multilingualism broadens my personal horizon as a teacher.

Multilingualism hinders the communication of social values.

Multilingualism is discussed too often in education.

Multilingualism is a consequence of mass immigration.

Multilingual language use leads to fuzzy lines between separate languages.

Migrant students are ashamed of using their native language.

Multilingualism’s potential is not exhausted in school.

The school is heavily shaped by the students’ multilingualism.

Maltese primary state schools are multilingual.

Being multilingual in different scripts hinders students’ literacy.

Migrant students taking mother tongue lessons outside school hours feel more secure in their identity.

When multilingual students switch between languages, they switch between different independent language systems.

The mother tongue is the language a person learns first.

Statements for pedagogy component

Migrant students should be dispensed from Maltese language classes.

Multilingualism is an important topic to be discussed in schools.

A common language is important.

Migrant students need additional support to learn Maltese.

Multilingual students should not learn additional languages but focus on the ones they already know.

Everybody should be functionally trilingual.

Migrant students have a right to language lessons to further their competence in their mother tongue.

Maltese students and migrant students should learn Maltese separately.

Multilingualism is a right at school.

Migrant students should be assessed in their mother tongue.

Schools should have access to multilingual material.

Competencies in more than two languages are unnecessary.

Cooperation with the multilingual students’ parents is vital for the students’ success.

Language support in Maltese and/or English should be provided based on the students’ level of competence in the language, regardless of their citizenship.

A common attitude towards multilingualism is important within the teaching staff.

Schools should change their way of teaching due to society’s increased multilingualism.

Language teaching should be done entirely in the target language.

Students should be encouraged to use their full linguistic repertoire.

The school needs more concrete guidelines concerning multilingualism.

I treat every student the same, regardless of their mother tongue.

In my school, it is normal to see students’ multilingualism in practice.

Migrant students should be dispensed from the Foreign Language Awareness Programme (FLAP).

Multilingualism should be part of teachers’ education.

Migrant students who speak neither Maltese nor English should take a language preparatory course before they take part in regular classes.

Teachers should be informed about which language/s students speak at home.

Migrant students have the right to receive individual support in their mother tongue.

Teaching staff should receive information and training about multilingualism.

Being allowed to use all their languages during lessons helps multilingual students in their learning.

We need a ‘Maltese and English only’ policy in our state schools.

I don’t understand migrant students’ mother tongues, so I don’t want them to use them.

Classroom teachers should collaborate closely with language support teachers.

A central task of the teacher is to systematically support the development of students’ multilingual identity.

Teachers need to know when migrant students are taking mother tongue lessons outside school hours.

Parents and students should receive information about multilingualism.