ABSTRACT

The current study examines how organizational career management – i.e. activities undertaken by schools in order to plan and manage teachers’ careers – relates to teachers’ career self-management – i.e. teachers steering their careers by means of searching for opportunities, networking, or seeking supervisory support. Moreover, it examines the mediating roles of occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation in this relationship. Mediation analysis in SPSS, using the PROCESS macro of survey data from 220 Dutch secondary school teachers, showed that positive relationships between organizational career management and career self-management were mediated by occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation.

Introduction

Employees’ career development is seen as one of the topics central to HRD (Park and Rothwell Citation2009; Mehdiabadi et al. Citation2017; Shuck et al. Citation2018). That is, as the range of possible occupational and educational choices in Western societies has increased dramatically (OECD Citation2011), employees are expected to engage in lifelong learning in order to stay broadly employable (Baruch, Szűcs, and Gunz Citation2015). Moreover, since organizations have flattened and promotion-based career cultures are disappearing, employees at all levels should be in charge of their career development (Shuck et al. Citation2018). Consequently, employees are recommended to engage more in career self-management, referring to employees showing proactivity with respect to steering their career, by means of searching for career opportunities, networking, or seeking supervisory support and positioning oneself (cf. King Citation2004; Mihail Citation2008).

Despite this emphasis on the individual employee, career management also remains an important responsibility for organizations, as they still provide the context within which career development takes place (De Vos and Cambré Citation2017). However, while scholars indeed increasingly agree that career development should be owned by employees, but supported by organizations and facilitated by managers, studies suggest that this is still more wishful thinking than reality Inkson and King (Citation2011). Hence, more knowledge is needed on how (managers within) organizations can actually support and facilitate career development of employees at all levels (Inkson and King Citation2011; Shuck et al. Citation2018). The current paper addresses this need for knowledge by examining how organizational career management, which refers to the activities undertaken by organizations to plan and manage employees’ careers (cf. Baruch and Budhwar Citation2006), can support career self-management.

More specifically, the paper does so by focussing on the educational context, because organizational career management and career self-management have become increasingly relevant for this particular context for several reasons. First, due to the rise of ‘new public management’ in the 1980s, a shift has taken place towards the greater accountability of public sector organizations in general (Hood Citation1995) and schools in particular (Bouwmans, Runhaar, Wesselink et al. Citation2017). Therefore, formal career decisions – for instance related to renewal or dismissal of contracts or to promotion to higher salary scales – are increasingly made on the basis of teacher performance (e.g. Grissom et al. Citation2017). However, the difficulty of measuring teacher performance, due to the numerous intervening variables, is widely acknowledged (e.g. Rothstein Citation2010). So in order to prevent teachers from having to depend on principals’ judgments on performance data, which can be misinterpreted or incomplete teachers should make an effort in positioning themselves, which is seen as a core aspect of career self-management (De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens Citation2009).

Second, although there are relatively few management positions or other growth opportunities in schools for which teachers can apply and although salaries are mostly fixed, there are numerous other (more informal) ways in which teachers can develop themselves throughout their careers. Especially, teachers’ roles in the ‘secondary process’ have changed considerably over the years (Scheerens Citation2009). Teachers can, for instance, specialize in giving individual guidance to pupils in the role of mentor or in initiating educational innovations in the role of teacher leader. These kinds of roles require specific kinds of competencies and can be allocated to teachers, based on their competences and ambitions. This requires teachers to know what they want and what they are capable of. Moreover, they should be aware of the available opportunities and what it takes to be considered a suitable candidate by their supervisors. In other words: teachers should engage in career self-management (De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens Citation2009).

Third, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sciences (ECS) in The Netherlands, where the current study took place, has invested deeply in strengthening the teacher profession, the assumption being that the quality of education is mainly determined by the quality of the teacher corps. These investments have, for instance, been targeted at enhancing the quality requirements for teacher education programs; enhancing the quality of novice teacher induction programs; increasing teacher opportunities to obtain a Master or even PhD degree; more salary grades for teachers, resulting in an increase in growth opportunities within the teacher profession (ECS Citation2007). The last couple of years, Dutch schools have been developing and implementing strategic HR policies and practices in order to link all the measures, initiated by ECS, to their own educational goals (see, for instance, Runhaar and Sander, Citation2013). Although schools have made progress in HR implementation, still more knowledge is needed, especially on how schools can support teachers’ career development (Knies and Leisink Citation2017).

Next to the direct relationship between organizational career management and career self-management, the current paper also examines the mechanisms underlying this relationship. More specifically, the study examines the mediating roles of teachers’ occupational self-efficacy – i.e. the conviction that one can successfully execute the behaviour that is needed to meet the demands one encounters in work situations (Schyns and Von Collani Citation2002) – and teachers’ learning goal orientation – the motivation to constantly improve one’s competencies (VandeWalle Citation1997). Including these mediating variables, the study adheres to the so-called ‘process model‘ of strategic human resources management (SHRM) (e.g. Purcell and Hutchinson Citation2007; Nishii andWright Citation2008) which states that HR policies (like organizational career management) affect employee behaviour (like career self-management) via employees’ attitudes (like occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation). The theoretical section will elaborate more specifically on the choice for these mediating variables.

In sum, two central research questions are formulated: To what extent does the organizational career management initiated by schools affect teachers’ career self-management?’ And: To what extent is this relationship mediated by teachers’ occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation?

Study context: Dutch secondary education

In The Netherlands, children are admitted to a secondary school when they are around 12 years of age (OECD Citation2009). There are three types of secondary education: (1) four years of pre-vocational secondary education (VMBO); (2) five years of higher general secondary education (HAVO); and, (3) six years of pre-university education (VWO). Most secondary schools combine some or all of these three types of education in order to easily facilitate the transfer of pupils from one type to another OECD (Citation2009). Schools are mostly clustered under one school board that covers various schools within a region and that includes all school types as described above. Schools can be divided over various locations. Often, one of the board members is responsible for HR policy: policy which is explicitly targeted at attracting, retaining, developing and rewarding teachers in such a way that it results in optimal individual and school performance (Runhaar and Runhaar Citation2012). Every school has a school administration. Amongst other actors, like a controller or a facility manager, the administration consists of a principal and one or more HR officers who execute the centrally formulated HR policy.

As mentioned in the introduction, the Dutch Ministry Education, Culture and Sciences has implemented different types of measures in order to strengthen the teacher profession. Parallel to this, schools have started to implement a so-called ‘Integrated Personnel Policy’; meaning that all HR practices are aligned to school goals (‘vertical integration’) and to each other (‘horizontal integration’) (Boselie, Dietz, and Boon Citation2005). Vertical integration means, for instance, that in a school where the incorporation of e-learning in education is highly valued, teachers have the opportunity to develop themselves in this area. Horizontal integration implies that teachers who show innovativeness in designing e-learning methods are appraised and even rewarded for their efforts. The HR concept which dominates the government’s policy documents has evolved since then and is increasingly being inspired by the business sector (ECS Citation2007). It comprises career development and mobility; education and training; conditions of employment and reward; performance appraisal; and participation (for more information, Runhaar and Runhaar Citation2012; Runhaar and Sanders Citation2013).

Secondary schools are represented by the Council for secondary education (in Dutch: VO-Raad). The Council is the primary negotiator on educational and personnel policy with the Ministry of ECS and other interested parties, like labour unions (for more, see EACEA Citation2009). The Council has been facilitating the implementation of HR policies in secondary schools, for instance by means of training principals and providing them with literature. The quality of HR policies in schools is monitored by the Dutch Educational Inspectorate. Recent research shows that school boards on average have made progress in formulating HR policy plans that are closely linked to their education policy and that the execution of these plans by the principals varies across schools (Knies and Leisink Citation2017). The Dutch educational context is comparable to that of most other western countries where schools are increasingly being held accountable for student outcomes and, consequently, for teacher quality and HR practices (OECD Citation2011). Hence, the study has relevance beyond this specific context.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

As stated already in the introduction, scholars increasingly attribute the responsibility of managing one’s career to employees (e.g. Arthur, Khapova, and Richardson Citation2016). Hence, individual employees are viewed as the primary actors in steering their own careers (Mihail Citation2008). Steering one’s career involves all those activities that allow teachers to assess their own talents and capabilities in the view of career opportunities at their schools as well as the activities teachers may undertake to realize their ambitions (De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens Citation2009; Quigley and Tymon Citation2006). These actions are: creating opportunities, for instance by developing skills which may be needed to attain one’s career goal; enhancing one’s visibility, for example, by making one’s supervisor aware of one’s accomplishments; asking advice to experienced colleagues related to one’s career development; and establishing relationships, via networking, with colleagues within or outside one’s department with whom one discusses career wishes (cf Noe Citation1996; De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens Citation2009). In the educational context, these actions can take various forms. For instance: teachers can ask their supervisors what budget is available for professional development and apply for following a specific courses (creating opportunities); teachers can inform their supervisors when they have achieved a success like the implementation of a new pedagogical method (enhancing one’s visibility); teachers can observe one another and exchange feedback in order to formulate input for professional development plans (asking advise); and teachers can contact professors and ask them for assistance while writing a PhD proposal or connect to teachers with a specific role that they aspire themselves (networking).

The current study examines whether organizational career management can support teachers’ career self-management, through enhancing teachers’ occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation. The choice for these specific variables and the mediation model is based on job demands-resources theories (for an overview, see Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007), which state that when available resources are perceived to exceed the demands imposed on employees (like career self-management), the situation will be appraised as a ‘challenge’, resulting in employees trying to meet the demands (Folkman Citation1984). On the other hand, if demands are perceived as exceeding the available resources (i.e. the situation is experienced as a ‘threat’), employees will try to avoid these demands Folkman (Citation1984). Translated to the current study, this implies that career self-management can be seen as a challenge because it holds the potential for competence development and recognition. For instance, career self-management can lead to being allowed to follow a course or to being offered challenging tasks. However, the search for career opportunities can just as easily be disappointing or accompanied with negative feedback from others. Career self-management can therefore also be perceived as a threat. Whether employees tend to focus either on the challenging or the threatening aspects of the demand depends on the availability of personal and organizational resources (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007), with personal resources mediating the effects of organizational resources on work outcomes (e.g. Simbula, Guglielmi, and Schaufeli Citation2011; Salanova et al. Citation2010). The current paper therefore proposes that organizational career management (as a situational resource) will affect career self-management via occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation (as personal resources). The following sections will elaborate further on the expected positive relationship between organizational career management and teachers’ career self-management and the expected mediating roles of occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation in this relationship.

Organizational career management and career self-management

In contrast with former times, where career management systems were targeted at advancing employees through an organization’s hierarchical layers, contemporary career systems comprise a much wider range of mobility patterns, like horizontal movement or temporary project work (Baruch, Szűcs, and Gunz Citation2015; Park and Rothwell Citation2009). Organizational career management therefore includes a wide range of interventions that focus on matching the career needs of individuals and schools in the form of (in)formal activities, like providing opportunities for professionalization, promotion, and career advice (cf. De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens Citation2009) career counselling, performance feedback, and contemporary learning (Eby, Allen, and Brinley Citation2005). This makes the concept suitable for the educational sector where relatively few hierarchical layers and little opportunities for performance-related pay exist but where a variety of roles teachers can apply for are present (see the section on the context of the study). Organizational career management can for instance take the form of development centres where teachers can reflect on their strengths and weaknesses and where they can be coached in formulating personal development plans. As such it can be helpful for teachers in steering their own career. Therefore, the current study focusses on practices related to learning and development and not solely on HR practices like performance appraisal and reward, associated with the more ‘traditional’ view on organizational career management.

Inherent to the contemporary understanding of organizational career management is the insight that both the school administration (including HR departments) as well as daily supervisors have their responsibilities. On one hand, this means that school administrations adopt procedures and regulations such as promotion and development opportunities and, on the other hand, that supervisors use these procedures and regulations when discussing employee performance and development and matching employee career wishes with the career opportunities available (De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens Citation2009). Therefore, organizational career management, as delivered by school administration in the form of rules and procedures, and organizational career management as implemented by supervisors in the form of ‘supervisor career support’, are regarded as two different constructs (see also De Oliveira, Cavazotte, and Alan Dunzer Citation2017). The way daily supervisors make sense of policy and rules may vary. Hence, their actual implementation can differ from the intended policy, leading to different perceptions among employees (cf Wright and Nishii Citation2008). Indeed, various studies show that HR policies, such as organizational career management, affect employees’ behaviour via the enactment of these policies by line managers (Knies and Leisink Citation2013).

Based on the foregoing elaboration, the first hypothesis was formulated as:

H1: The more teachers perceive organizational career management – as delivered by school administration and, subsequently, in the form of career support from their supervisors – the more they will engage in career self-management.

Occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation as mediators in the relationship between organizational career management and career self-management.

There are several reasons to expect that organizational career management can activate teachers’ occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation. Regarding occupational self-efficacy, the social cognitive theory (Bandura Citation1977) states that the social environment can enhance an individual’s occupational self-efficacy by the delivery of positive feedback (‘social persuasion’) and by offering opportunities to learn from others (‘vicarious experience’). It is to be expected that in situations where – due to the presence of organizational career management – reflection on competencies and discussions about future career steps are more common, teachers will exchange more mutual feedback. Moreover, when all teachers are stimulated to steer their careers, this will also stimulate them to help each other, for instance by sharing experiences, thereby increasing one another’s self-efficacy. This expectation is supported by studies showing positive links between organizational and supervisory support on the one hand and occupational self-efficacy of employees (Schyns and Von Collani Citation2002) and teachers in particular (Klaeijsen Citation2015) on the other hand.

Regarding learning goal orientation, there is a growing body of work suggesting that although individuals may possess dispositional goal orientations, it is also likely that they develop different ‘state goal orientations’ in response to situational cues (DeShon and Gillespie Citation2005). For instance, studies show that goal orientation can be stimulated by means of goal setting and feedback (e.g. Kozlowski and Bell Citation2003). Translating these findings to the current study, school administration and direct supervisors encouraging reflection on career ambitions by means of professional development plans, or stimulating the exchange of feedback by means of career discussions, might serve as situational cues which stimulate teachers to adopt a learning goal orientation.

Self-efficacy and learning goal orientation are interrelated (VandeWalle Citation2003). More specifically, goal orientations are based on implicit theories about one’s abilities, such as intelligence and personal skills (Dweck Citation2000). More specifically, learning goal orientation is associated with the belief that – with effort – one can learn how to deal with difficult situations. This belief closely links to the concept of self-efficacy and leads to the expectation that individuals with a high learning goal orientation possess self-efficacy and, therefore, that occupational self-efficacy precedes learning goal orientation.

Based on the above, the second hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H2: The more teachers perceive organizational career management – as delivered by school administration and, subsequently, in the form of career support from their supervisors – the stronger their occupational self-efficacy (H2a) and, in turn, their learning goal orientation (H2b).

There are reasons to expect that once teachers’ occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation are activated, this will lead to more career self-management. Related to occupational self-efficacy, research has shown a positive relationship between people’s self-efficacy and their tendency to appraise difficult tasks as being a challenge rather than a threat and, consequently, their tendency to engage in these tasks rather than to avoid them (Jerusalem and Schwarzer Citation1992). The expectation is that this also applies to career self-management. For example, the higher one’s self-efficacy, the more one will be convinced of one’s competencies, which will consequently make it easier for teachers to position themselves and to enhance one’s visibility (one of the career self-management activities). Moreover, self-efficacy may embolden teachers to face certain risks that accompany career self-management such as meeting resistance or negative feedback from others. Resistance or negative feedback can for instance occur when: the supervisor does not recognize the picture the teacher presents; or when a supervisor rejects one’s request for a course or a new task; or when someone else is granted the promotion one is aiming for. In these kinds of situations, the conviction that one only learns through ‘failure’ – which is inherent in self-efficacy – will encourage teachers to keep moving forward despite possible disappointments as an outcome of their engagement in career self-management activities (Bandura Citation1977).

Furthermore, based on goal orientation theory (Dweck Citation2000), it is reasonable to expect that individuals with strong learning goal orientation are more likely to engage in career self-management. Persons with a strong learning goal orientation are likely to view career self-management as a challenge and an opportunity to learn because they continuously search for ways of improving their knowledge and skills (VandeWalle Citation2003; van der Rijt, Van den Bossche, van de Wiel et al. Citation2012). Moreover, teachers with a strong learning goal orientation, are likely to see both positive and negative feedback as relevant information that helps them to improve their capabilities (Tuckey, Brewer, and Williamson Citation2002) and should therefore be less discouraged by the risks associated with career self-management and focus on its potential for personal development. Again assuming that occupational self-efficacy precedes learning goal orientation, the third hypothesis was formulated as:

H3: The stronger teachers’ occupational self-efficacy (H3a) and, in turn, their learning goal orientation (H3b), the more they will engage in career self-management.

Combined, the former hypotheses resulted in the last hypothesis, representing the whole mediation model:

H4: The positive relationship between organizational career management – as delivered by school administration and, subsequently, in the form of career support from their supervisors – and teachers’ career self-management, will be mediated by teachers’ occupational self-efficacy (H4a) and, in turn, their learning goal orientation (H4b).

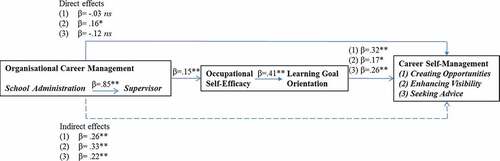

All proposed relationships are summarized in :

Methods

Respondents

Data were collected through an online survey among 220 teachers working in 20 teams at three secondary education schools. The three schools were spread over the western, southern, and middle part of the Netherlands. The sample included one school with four teams, situated in one location, offering education only at the highest level (see the section on ‘Study Context’ for a description of the Dutch educational levels). A second school consisted of 12 teams, spread over three locations, offering education on all different levels. A third school consisted of four teams, situated on one location, offering education on all levels.

The mean age was 43 (standard deviation of 12.4); 53.6% were men; 1.9% finished secondary vocational education, 75.8% finished higher vocational education, and 22.3% finished university.

Procedure

The principals of the three schools were members of one of the authors’ professional network. The principals showed interest in the survey since they had been busy with improving their HR systems and were therefore curious to find out how HR practices were perceived by their teachers. The principals asked teachers, through their team leaders, to fill out the questionnaire. More specifically, teachers received an e-mail wherein the study goals were explained and which contained a link to the online questionnaire. Teachers were also assured that their responses would be treated with the utmost confidentiality. The data were only used by the researchers; no details regarding individual teachers were shared with others.

Instruments

Career Self-Management. In order to measure career self-management, the items of an existing scale, developed by Noe (Citation1996) were used. The items – which can be found in Noe (Citation1996) – were translated to Dutch and validated in the study of De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens (Citation2009). The latter scale was slightly adjusted in order to fit the educational sector and, therefore, to enhance the acceptance of the items among teachers. For instance, the word ‘organization’ was replaced by the word ‘school’; the word ‘career development’ by ‘professional and career development’; and the word ‘line manager’ by ‘supervisor’. Principal Component Analysis (varimax rotation) showed that, in contrast to theory but in line with the findings of Noe (Citation1996), the scale consisted of three subscales, namely: Creating Opportunities; Enhancing One’s Visibility; and Seeking for Advice. Appendix 1 gives an overview of the items and the factor loadings and Cronbach’s Alphas of the three subscales.

Organizational Career Management was measured with the scales of De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens (Citation2009). The original items are listed in the article of the De Vos, Dewettinck, and Buyens (Citation2009). These scales were originally targeted at for-profit organizations. Therefore, some items (for instance one on succession planning) were deleted and replaced with items that were more in line with recent developments in Dutch HR policies (for instance, the Ministry of Education recently implemented a wider range of pay scales for teachers). Principal Component Analysis (varimax rotation), as seen in Appendix 2, shows the items and their loadings on two factors and presents, on the diagonal, the Cronbach’s Alphas of two subscales (i.e. organizational career management as delivered by the school administration and by supervisors).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and correlations between all study variables (Pearson’s r and Kandall’s Tau).

Occupational Self-Efficacy. In order to measure occupational self-efficacy, the six-item scale of Schyns and Von Collani (Citation2002) was used. An example item is: ‘Whatever happens in my work, I can usually cope with it’. Cronbach’s alpha in our study was α = .81.

Learning goal orientation, was measured by a five-item scale developed by VandeWalle (Citation1997), and consists of items such as: ‘I am prepared to do challenging tasks from which I can learn a lot’. Cronbach’s Alpha was α = .85.

Control variables. Pre-structured questions were used to determine gender (1 = male; 2 = female) and teachers’ highest finished educational level (1 = secondary vocational education; 2 = higher education; 3 = university). Age was measured by asking respondents to give their age in years.

Data analyses

Bivariate correlation analyses were conducted in order to examine how study variables correlated to control variables (Pearson’s r was calculated for interval variables and Kandall’s Tau for categorical variables). In order to test the hypotheses, the total indirect effect of organizational career management as delivered by school administration on teachers’ career self-management through HR practices as delivered by teachers’ supervisors, their occupational self-efficacy and their learning goal orientation was investigated. Bootstrapping procedures were used to obtain estimates of the indirect effects and to test their significance by using confidence intervals (Preacher and Hayes Citation2008). The PROCESS macro for SPSS 22.0, as developed by Hayes (Hayes Citation2013) and available for download at http://afhayes.com was used. This macro makes it possible to include multiple mediators in one model simultaneously and to compare the specific indirect effects associated with each mediator. Moreover, using the macro makes it possible to measure the direct effects between independent and dependent variables. Indirect effects were concluded to be statistically significant in case a zero was not included in the 95% confidence interval of the estimate (Preacher and Hayes Citation2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics

shows the means, standard deviations of variables and correlations between them. It shows that all study variables were related to each other, except that occupational self-efficacy was not related to the career self-management activity of seeking advice nor to organizational career management as delivered by school administration (β = . 11 and .12, respectively).

Where it comes to the control variables, gender appeared to be related to age (r = −.21, p < .01) and education (r = −.20, p < .01) meaning that female teachers were younger and lower educated than their male counterparts. Also, female teachers displayed lower levels of occupational self-efficacy than their male counterparts (r = −.17, p = <.01). Regarding age, the data showed that the older the teacher, the higher their occupational self-efficacy (r = .14, p < .05) and the lower their learning goal orientation (r = −.14, p < .05) and seeking for advice (r = −.30, p < .01). Finally, the higher one’s educational level, the higher one’s occupational self-efficacy (r = .12, p < .05) and the more one creates opportunities (r = .11, p < .05).

Testing the hypotheses

shows the direct effects between all study variables. shows the significance of the various direct and indirect relationships. Due to the categorical nature of gender and education, the control variables were not entered in the equation.Footnote1

Table 2. Results from Mediation Process Analyses; direct relationships among independent, mediating, and outcome variables.

Table 3. Results from mediation process analyses: total, direct, and indirect effects of organizational career management on three forms of career self-management as dependent variables.

The first hypothesis predicted a positive relationship between organizational career management, as delivered by school administration and subsequently in the form of career support from their supervisors, on the one hand, and teachers’ career self-management on the other (H1). shows that organizational career management as delivered by school administration was positively related to that delivered by supervisors (β = .85, p < .01). In turn, organizational career management by supervisors was directly related to all three career self-management activities (β = .21, .34, and .21, p < .01, respectively, ). Mediation analyses showed that the positive relationships between organizational career management as delivered by administration and all forms of career self-management were mediated by supervisory support (see models (1) in ). These outcomes suggest that school-wide policies and procedures that stimulate teachers’ career self-management affect teachers’ behavioural response via the career support provided by their supervisors. It should be noted that a direct effect of organizational career management as delivered by the school administration on teachers’ seeking advice remained (β = .16, p < .05; ).

The second hypothesis, which predicted a positive relationship between teachers’ perceptions of organizational career management on the one hand and their occupational self-efficacy (H2a) and, in turn, learning goal orientation (H2b) on the other, could be confirmed. More specifically, organizational career management as delivered by school administration did not relate to teachers’ occupational self-efficacy (see , β = −.05, ns) whereas career management as delivered by supervisors did positively relate to occupational self-efficacy (β = .15, p < .01). The same was true for learning goal orientation. Also here, no effect was found of career management as delivered by school administration (see : β = .06, ns), whereas the support form supervisors did positively affect teachers’ learning goal orientation (β = .11, p < .05). These outcomes indicate that also here the effect of school-wide policies and procedures on teachers’ responses was transferred through the support of their supervisors. Moreover, the results of the mediation process analyses suggest that self-efficacy preceded learning goal orientation (models (4) of ).Footnote2

The third hypothesis (H3), in which positive relationships between teachers’ occupational self-efficacy (H3a) and learning goal orientation (H3b) on the one hand and their engagement in career self-management on the other were predicted, could be confirmed. More specifically, occupational self-efficacy appeared to be positively related only to the activity of creating opportunities (see : β = .20, p < .01) and not to enhancing one’s visibility or seeking advice (β = 17 and β = −.10, ns. respectively). Teachers’ learning goal orientation however positively affected their engagement in all career self-management activities (see : β = .32, p < .01; β = .17, p < .05; β = .26, p < .01).

Also here, the results of the mediation process analyses suggest that self-efficacy preceded learning goal orientation (models (4) of ).Footnote3

Finally, the fourth hypotheses included all study variables and predicted that the positive relationships between organizational career management – as delivered by school administration and, subsequently, in the form of career support from supervisor – and teachers career self-management would be mediated by teachers’ occupational self-efficacy and, subsequently, their learning goal orientation. Models (4) of indeed were significant for all career self-management activities, thus supportive for the fourth hypothesis.

It should be noted that for all three forms of career self-management, most variance was explained by the two forms of organizational career management (18/26, 28/33, 18/22, respectively, see models (1) of ). The mediators thus added a relatively small amount of explained variance.

summarizes the most important findings:

Discussion and conclusions

Career development is at the heart of HRD, but deserves more attention in research. Especially, more research is needed on how (managers within) organizations can actually support career development of employees at all levels. The current study tried to meet this call for knowledge by examining how schools can support teachers’ engagement in career self-management, operationalized as creating career opportunities, seeking career advice and enhancing one’s visibility. More specifically, the study aimed to answer two central questions: To what extent does the organizational career management initiated by schools affect teachers’ career self-management? and: To what extent is this relationship mediated by teachers’ occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation?.

By answering these questions, two main conclusions can be drawn. First, the study revealed that the more teachers perceived that their schools undertook activities to plan and manage teachers’ careers – like matching individual careers to school needs by means of (in)formal activities, such as providing opportunities for professionalization or promotion and career advice – the higher teachers’ engagement in career self-management was (see the results regarding Hypothesis 1, p. 17/18). Hence, the first conclusion is that organizational career management initiated by schools indeed can affect teachers’ career self-management. It was found, however, that organizational career management, as delivered by the school administration in the form of policies, procedures and practices, affected teachers’ career self-management through the career support as delivered by teachers’ supervisors. The theoretical implication of this finding is that it is worthwhile to distinguish between organizational career management as delivered by school administration (including HR departments) on one hand and career support delivered by daily supervisors on the other. In line with the process model of SHRM (e.g. Wright and Nishii Citation2008; Purcell and Hutchinson Citation2007) and empirical evidence (e.g. Knies and Leisink Citation2013), the results suggest that HR policies like organizational career management affect employees’ behaviour via the enactment of these policies by line managers.

The second conclusion is that the link between organizational career management and teachers’ career self-management could be further explained by teachers’ occupational self-efficacy and, subsequently, their learning goal orientation (research question 2). Apparently, the more teachers perceived the presence of school-wide procedures and regulations concerning career management and the more they perceived career support from their supervisors, the higher their occupational self-efficacy and their learning goal orientation subsequently was (see the results regarding Hypothesis 2a/b, p. 18). In turn, the results indicate that these higher levels of self-efficacy and learning goal orientation supported teachers’ engagement in career self-management (see the results regarding Hypotheses 3a/b and 4a/b, p. 19). The theoretical implication of these findings for organization career management studies is that it is worthwhile to include employees’ attitudinal responses to career policies in examining their effects on employee behaviour. As such it, again, confirms the process model of SHRM (Purcell and Hutchinson Citation2007). Moreover, the results support job-demands-resources-theory (e.g. Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007), which state that employees’ tendency to approach or avoid certain demands (like career self-management) depends on the availability of organizational resources (like organizational career management) and personal resources (like occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation) with personal resources mediating the effects of organizational resources.

The mediating effects of self-efficacy and learning goal orientation were, however, relatively small which indicates that other variables may have played a role as well. One could, for instance, imagine that the organizational culture in schools can facilitate or hinder teachers’ career self-management. Schools have often been characterized as ‘political arenas’ wherein teachers have to navigate and learn desirable behaviour (Kelchtermans Citation2005). This, for instance, could be the result of the double role principals often have. That is, they are on one hand – as educational leaders – expected to guide teachers’ professional development and on the other hand – as managers – expected to control the quality and efficiency of education. These, sometimes conflicting, roles can lead to teachers not daring to be vulnerable, which career self-management requires, but instead stimulate teachers to employ strategic power to pursue their interests (Christensen Citation2013). In terms of demands-resources-theory, for future studies, it is recommended to search for other personal resources (like political skills or role clarity) as well.

The results showed some remarkable effects of the three control variables; level of education, gender and age. Regarding the first, the higher educated teachers in the current sample, displayed higher levels of occupational self-efficacy and created more career opportunities. In the light of ensuring equity in career opportunities in organizations among all employees, this is something for supervisors to keep in mind. Maybe, lower educated personnel should be coached or stimulated to engage in career self-management more intensely than their higher educated colleagues. Regarding gender, female teachers in our sample appeared to be lower educated and to display lower levels of occupational self-efficacy than men. As proposed and proved in career research in other contexts (e.g. O’Neil and Bilimoria Citation2005) it may well be that gender plays a role in teachers’ career development. Hence, it would be worthwhile to dig further into the issue in future research. Finally, regarding age, the older the teacher, the higher his/her occupational self-efficacy and the lower his/her learning goal orientation and seeking of advice. This is an interesting finding as well and indicates that supervisors should take teachers’ age into account. As is the case in employees in general (Kanfer and Ackerman Citation2004) teachers’ careers consist of different phases characterized by different core concerns and different professional development needs (Louws et al. Citation2017). This may well have an impact on their career wishes as well. The theoretical implication of these findings is that in search for the effects of career systems, it is worthwhile to take demographic characteristic of employees into account as well.

The current study was conducted in the public sector, in Dutch schools in particular. There are several reasons why employees’ motivation and behaviour in this sector may differ from employees working in profit sectors. For instance, it has been found that employees working in public sectors in general seem to place greater value on service to society than do employees in private organizations (Perry Citation2000). This may well be true for teachers that are known to be intrinsically motivated to take care of others (O’Connor Citation2008). On the other hand, the work environment of these service-oriented employees often inhibit their possibilities to actually achieve their higher order goals. For instance, the lack of autonomy and procedural constraints are found to have detrimental effects on employees’ motivation and their job satisfaction (Wright and Davis Citation2003). Moreover, as governmental policies are often subject to change, it is difficult to stabilize organizational policies like organizational career management (Burchielli Citation2006). All these factors at individual, institutional and national levels may well play a role in teachers’ engagement in career self-management activities and should be taken into account when aiming to translate the current findings to other contexts.

In addition to the discussion of the findings, there are some limitations of the study that need to be pointed out. First, teachers’ responses to organizational career management were based on their perceptions and not the ‘objective’ presence or absence of organizational career management. Future studies could incorporate other data sources, like supervisors’ perceptions of the presence of organizational career management or documentary analyses as provided by HR departments for instance. Moreover, data could include performance reviews and examples of the supervisor review process. Finally, teachers’ perceptions were measured with predefined question and therefore limited by the way variables were operationalized by researchers. Future studies could include open questions in the survey or interviews in order to yield richer and also more concrete picture of how schools can support career self-management.

A second limitation is related to the way the two forms of organizational management were operationalized. More specifically, the items that supposed to measure organizational career management as delivered by direct supervisors, were not literally targeted at the supportive behaviour of supervisors. Although these items, as opposed to the items related to the existence of school-wide policies, were formulated in terms of ‘I’ and ‘me’ and as such focused on personal experiences, the question remains whether the items really measured the concrete supportive behaviours of teachers’ supervisors. Hence, for future studies, it is recommended to include items derived from scales like ‘empowering leadership’ (Amundsen and Martinsen Citation2014) or ‘managerial coaching’ (Heslin, Vandewalle, and Latham Citation2006) as means to measure these kinds of behaviours.

Third, the data used are cross-sectional. Although the analyses were bootstrapped, the nature of the data does not allow drawing causal relationships between study variables. Therefore, the findings reported in this paper, including those concerning multiple mediators, should be interpreted with caution. Longitudinal techniques are necessary to determine the exact direction of relationships.

Practical implications

The findings from the current study suggest that the Dutch approach to career development, as adopted by government and school boards, is promising and that it may be built on by educational policy officers from other countries. More specifically, given the positive relationship between school-wide organizational career management and teachers’ career self-management, schools are recommended to keep investing in ways to stimulate teachers’ career development. The items shown in Appendix 2 may be used by school administrators and HR professionals as a starting point in shaping career management practices in their schools. In dialogue with teachers, these practices can be adjusted and complemented in such a way that these suit teachers’ needs. Moreover, the finding that supervisors play an important role in effectuating school-wide career management policies and procedures suggests that executing their HR role should be acknowledged as being an important aspect of their function description. Indeed, line managers in organizations in general (e.g. Purcell and Hutchinson Citation2007) and in education specifically (e.g. Vekeman, Devos, and Valcke Citation2016) are seen as important actors in effectuating HR policies, like organizational career management. However, a mismatch between ‘intended’ and ‘actual HR’ can easily occur (Wright and Nishii Citation2008). Reasons are, for example, a lack of awareness among line managers about available HR practices or a lack of competencies to implement them (Akingbola Citation2013), or a mismatch between what was developed by HR departments and line managers’ or teachers’ needs (Runhaar and Sanders Citation2013) are named as causes. Therefore, for management development (MD) trajectories for supervisors in schools, it is recommended that these should include HR theory and give room for managers to learn how to make usage of HR practices. Regarding the latter, one could think of role plays as means to train how to hold a conversation with teachers about their strengths and weaknesses and about their career ambitions. Combined with having HR practitioners available within the school, supervisors can be supported in enacting their roles in an effective way (e.g. Roberts Citation2007).

Since self-efficacy and learning goal orientation appear prerequisites for career self-management, schools are recommended to invest in creating working environments that foster these variables in teachers. Regarding the first, Bandura (Citation1993) states that because people’s sense of self-efficacy is partly based on the positive feedback they get from others, individual self-efficacy partly depends on the collective self-efficacy in a school. Hence, creating a culture wherein successes and strengths of people are accentuated seem important. Moreover, because teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs increase as a result of the cooperation between teachers (OECD Citation2009), schools are further advised to enhance teachers’ collaboration, which can take many forms, varying from the exchange of materials to working together on learning methods or discussing student’s performance. Regarding learning goal orientation, schools should put effort in creating a so-called ‘situational learning goal orientation’ (Button, Mathieu, and Dennis Citation1996), meaning a work environment that supports learning goal orientation. This can for example be done by stressing the importance of teachers’ learning by providing them with time and funding for professional development activities. Furthermore, because acknowledging teachers’ individual learning needs appears to be preferable to school-wide interventions (OECD Citation2009) supervisors should as much as possible assure that teachers can attend a course or training, or become a member of learning networks when they find that they need it. Finally, recognizing teachers’ engagement in professional development activities, their innovative ideas and new solutions to problems proves other strategies to strengthen teachers’ motivation to keep on developing themselves (OECD Citation2009).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (112.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Notes

1. As a test, the analyses were conducted with and without control variables and similar results were yielded.

2. In order to confirm the mediation effects as proposed in hypotheses 2a and b, additional mediation was conducted with occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation as outcome variables. These analyses indeed showed insignificant direct and significant indirect effects of organizational career management on these two outcome variables. Moreover, this indirect effect on learning goal orientation appeared to be transferred through occupational self-efficacy. For the sake of clarity, these outcomes are not included in the main text of the paper but provided in the supplementary material (Table IV).

3. Also here, in order to confirm the mediation effects as proposed in hypotheses 3a and b, additional mediation was conducted with occupational self-efficacy and learning goal orientation as independent variables and the different forms of career self-management as dependent variables. As Table IV of the supplementary material shows, these analyses showed that learning goal orientation acted as a mediator in the relationships between occupational self-efficacy on the one hand and the different forms of career self-management on the other.

References

- Akingbola, K. 2013. “A Model of Strategic Nonprofit Human Resource Management.” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organisations 24 (1): 214–240. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9286-9.

- Amundsen, S., and Ø. L. Martinsen. 2014. “Empowering Leadership: Construct Clarification, Conceptualization, and Validation of a New Scale.” The Leadership Quarterly 25 (3): 487–511. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.009.

- Arthur, M. B., S. N. Khapova, and J. Richardson. 2016. An Intelligent Career: Taking Ownership of Your Work and Your Life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bakker, A. B., and E. Demerouti. 2007. “The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 22 (3): 309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115.

- Bandura, A. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84: 191–215.

- Bandura, A. 1993. “Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning.” Educational Psychologist 28: 117–148. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3.

- Baruch, Y., N. Szűcs, and H. Gunz. 2015. “Career Studies in Search of Theory: The Rise and Rise of Concepts.” Career Development International 20: 3–20. doi:10.1108/CDI-11-2013-0137.

- Baruch, Y., and P. S. Budhwar. 2006. “A Comparative Study of Career Practices for Management Staff in Britain and India.” International Business Review 15 (1): 84–101. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2005.11.001.

- Boselie, P., G. Dietz, and C. Boon. 2005. “Commonalities and Contradictions in HRM and Performance Research.” Human Resource Management Journal 15 (3): 67–94. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2005.tb00154.x.

- Bouwmans, M., P. Runhaar, R. Wesselink, and M. Mulder. 2017. “Stimulating Teachers’ Team Performance Through Team-oriented Hr Practices: The Roles Of Affective Team Commitment and Information Processing.” The International Journal Of Human Resource Management 1–23. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1322626.

- Burchielli, R. 2006. “The Intensification of Teachers’ Work and the Role of Changed Public Sector Philosophy.” International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management 6: 146–160. doi:10.1504/IJHRDM.2006.010391.

- Button, S. B., J. E. Mathieu, and M. Z. Dennis. 1996. “Goal Orientation in Organizational Research: A Conceptual and Empirical Foundation.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 67 (1): 26–48. doi:10.1006/obhd.1996.0063.

- Christensen, E. 2013. “Micropolitical Staffroom Stories: Beginning Health and Physical Education Teachers’ Experiences of the Staffroom.” Teaching and Teacher Education 30: 74–83. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.11.001.

- De Vos, A., and B. Cambré. 2017. “Career Management in High Performing Organizations: A Set‐Theoretic Approach.” Human Resource Management 56 (3): 501–518. doi:10.1002/hrm.2017.56.issue-3.

- De Vos, A., K. Dewettinck, and D. Buyens. 2009. “The Professional Career on the Right Track: A Study on the Interaction between Career Self-Management and Organisational Career Management in Explaining Employee Outcomes.” European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology 18 (1): 55–80. doi:10.1080/13594320801966257.

- De, Oliveira, L. B., F. Cavazotte, and R. Alan Dunzer. 2017. “The Interactive Effects of Organisational and Leadership Career Management Support on Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1–21. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1298650.

- DeShon, R. P., and J. Z. Gillespie. 2005. “A Motivated Action Theory Account of Goal Orientation.” Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (6): 1096–1127. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1096.

- Dweck, C. S. 2000. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality and Development. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

- EACEA. 2009. Key Data on Education in Europe. Brussels: Eurydice.

- Eby, L. T., T. D. Allen, and A. Brinley. 2005. “A Cross-Level Investigation of the Relationship between Career Management Practices and Career-Related Attitudes.” Group and Organisation Management 30 (6): 565–596. doi:10.1177/1059601104269118.

- Folkman, S. 1984. “Personal Control and Stress and Coping Processes: A Theoretical Analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 46: 839–852. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839.

- Grissom, J. A., M. Rubin, C. M. Neumerski, M. Cannata, T. A. Drake, E. Goldring, and P. Schuermann. 2017. “Central Office Supports for Data-Driven Talent Management Decisions: Evidence from the Implementation of New Systems for Measuring Teacher Effectiveness.” Educational Researcher 46 (1): 21–32. doi:10.3102/0013189X17694164.

- Hayes, A. F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Heslin, P. A., D. Vandewalle, and G. P. Latham. 2006. “Keen to Help? Managers‘ Implicit Person Theories and Their Subsequent Employee Coaching.” Personnel Psychology 59 (4): 871–902. doi:10.1111/peps.2006.59.issue-4.

- Hood, C. 1995. “The ‘New Public Management’ in the 1980s: Variations on a Theme.” Accounting, Organisations and Society 20: 93–109. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(93)e0001-w.

- Inkson, K., and Z. King. 2011. “Contested Terrain in Careers: A Psychological Contract Model.” Human Relations 64 (1): 37–57. doi:10.1177/0018726710384289.

- Jerusalem, M., and R. Schwarzer. 1992. “Self-Efficacy as a Resource Factor in Stress Appraisal Processes.” In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action, edited by R. Schwarzer, 195–213. Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

- Kanfer, R., and P. L. Ackerman. 2004. “Aging, Adult Development, and Work Motivation.” Academy of Management Review 29 (3): 440–458. doi:10.5465/amr.2004.13670969.

- Kelchtermans, G. 2005. “Teachers’ Emotions in Educational Reforms: Self-Understanding, Vulnerable Commitment and Micropolitical Literacy.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21 (8): 995–1006. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009.

- King, Z. 2004. “Career Self-Management: Its Nature, Causes and Consequences.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 65 (1): 112–133. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00052-6.

- Klaeijsen, A. C. 2015. “Predicting Teachers‘ Innovative Behaviour: Motivational Processes at Work.” Doctoral Dissertation. Heerlen: Open University

- Knies, E., and P. Leisink. 2013. “Leadership Behavior in Public Organisations: A Study of Supervisory Support by Police and Medical Center Middle Managers.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 34 (2): 108–127. doi:10.1177/0734371X13510851.

- Knies, E., and P. L. M. Leisink. 2017. De Staat Van Strategisch Personeelsbeleid (HRM) in Het Vo [The State of Strategic HRM in Secondary Education]. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

- Kozlowski, S. W. J., and B. S. Bell. 2003. “Work Groups and Teams in Organisations.” In Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organisational Psychology, edited by W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, and R. J. Klimoski, 333–375. Vol. 12. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Louws, M. L., K. Van Veen, J. A. Meirink, and J. H. van Driel. 2017. “Teachers’ Professional Learning Goals in Relation to Teaching Experience.” European Journal of Teacher Education 40 (4): 487–504. doi:10.1080/02619768.2017.1342241.

- Mehdiabadi, A. H., G. Seo, W. D. Huang, and S. H. C. Han. 2017. “Building Blocks of Contemporary HRD Research: A Citation Analysis on Human Resource Development Quarterly between 2007 and 2013.” New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 29 (4): 20–34. doi:10.1002/nha3.20197.

- Mihail, D. M. 2008. “Proactivity and Work Experience as Predictors of Career-Enhancing Strategies.” Human Resource Development International 11 (5): 523–537. doi:10.1080/13678860802417668.

- Ministry of ECS. 2007. Actieplan Leerkracht Van Nederland [Action Plan for Teachers in the Netherlands]. The Hague: Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

- Nishii, L. H., and P. M. Wright 2008. Variability within organizations: Implications for strategic human resource management. In D. B. Smith (Ed.), The people make the place: Dynamic linkages between individuals and organizations (pp. 225–248). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

- Noe, R. A. 1996. “Is Career Management Related to Employee Development and Performance?” Journal of Organisational Behavior 17: 119–133. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199603)17:2<119::AID-JOB736>3.0.CO;2-O.

- O‘Neil, D. A., and D. Bilimoria. 2005. “Women‘s Career Development Phases: Idealism, Endurance, and Reinvention.” Career Development International 10 (3): 168–189. doi:10.1108/13620430510598300.

- O’Connor, K. E. 2008. “You Choose to Care”: Teachers, Emotions and Professional Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (1): 117–126. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.008.

- OECD. 2009. Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Environments: First Results from TALIS. Paris: Organisation for economicco-operation and development.

- OECD. 2011. Education at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Park, Y., and W. J. Rothwell. 2009. “The Effects of Organizational Learning Climate, Career-Enhancing Strategy, and Work Orientation on the Protean Career.” Human Resource Development International 12 (4): 387–405. doi:10.1080/13678860903135771.

- Perry, J. L. 2000. “Bringing Society In: Toward a Theory of Public-Service Motivation.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10 (2): 471–488. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024277.

- Preacher, K. J., and A. F. Hayes. 2008. “Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models.” Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–891.

- Purcell, J., and S. Hutchinson. 2007. “Front Line Managers as Agents in the HRM‐performance Causal Chain: Theory, Analysis and Evidence.” Human Resource Management Journal 17 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/hrmj.2007.17.issue-1.

- Quigley, N. R., and W. G. Tymon Jr. 2006. “Toward an Integrated Model of Intrinsic Motivation and Career Self-Management.” Career Development International 11 (6): 522–543. doi:10.1108/13620430610692935.

- Rijt, J., P. van der Van Den Bossche, M. W. van de Wiel, M. S. Segers, and W. H. Gijselaers. 2012. “The Role of Individual and Organisational Characteristics in Feedback Seeking Behaviour in the Initial Career Stage.” Human Resource Development International 15 (3): 283–301. doi:10.1080/13678868.2012.689216.

- Roberts, S. A. 2007. Re-thinking staff management in independent schools: an exploration of a human resource management approach (Doctoral dissertation, Murdoch University).

- Rothstein, J. 2010. “Teacher Quality in Educational Production: Tracking, Decay, and Student Achievement.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125 (1): 175–214. doi:10.1162/qjec.2010.125.1.175.

- Runhaar, P., and H Runhaar. 2012. “Hr Policies and Practices in Vocational Education and Training Institutions: Understanding The Implementation Gap Through The Lens Of Discourses.” Human Resources Development International 15: 609–625.

- Runhaar, P., and K. Sanders. 2013. “Implementing Human Resources Management (Hrm) Within Dutch Vet Schools: Examining The Fostering and Hindering Factors.” Journal Of Vocational Education & Training 65 (2): 236-255.

- Salanova, M., W. Schaufeli, I. Martínez, and E. Breso, E. 2010. “How Obstacles and Facilitators Predict Academic Performance: The Mediating Role of Study Burnout and Engagement.” Anxiety, Stress & Coping 23 (1): 53–70. doi:10.1080/10615800802609965.

- Scheerens, J. 2009. Review and Meta-Analyses of School and Teaching Effectiveness. The Netherlands: Department of Educational Organisation and Management

- Schyns, B., and G. Von Collani. 2002. “A New Self-Efficacy Scale and Its Relation to Personality Constructs and Organisational Variables.” European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology 11: 219–241. doi:10.1080/13594320244000148.

- Shuck, B., K. McDonald, T. S. Rocco, M. Byrd, and E. Dawes. 2018. “Human Resources Development and Career Development: Where are We, and Where Do We Need to Go.” New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 30 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1002/nha3.2018.30.issue-1.

- Simbula, S., D. Guglielmi, and W. B. Schaufeli. 2011. “A Three-Wave Study of Job Resources, Self-Efficacy, and Work Engagement among Italian Schoolteachers.” European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology 20 (3): 285–304. doi:10.1080/13594320903513916.

- Tuckey, M., N. Brewer, and P. Williamson. 2002. “The Influence of Motives and Goal Orientation on Feedback Seeking.” Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology 75 (2): 195–216. doi:10.1348/09631790260098677.

- VandeWalle, D. 1997. “Development and Validation of a Work Domain Goal Orientation Instrument.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 57: 995–1015. doi:10.1177/0013164497057006009.

- VandeWalle, D. 2003. “A Goal Orientation Model of Feedback-Seeking Behavior.” Human Resource Management Review 13: 581–604. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2003.11.004.

- Vekeman, E., G. Devos, and M. Valcke. 2016. “Human Resource Architectures for New Teachers in Flemish Primary Education.” In Educational Management Administration And Leadership 44 (6): 970-995.

- Wright, B. E., and B. S. Davis. 2003. “Job Satisfaction in the Public Sector: The Role of the Work Environment.” The American Review of Public Administration 33 (1): 70–90. doi:10.1177/0275074002250254.

Appendix 1. Factor structure Career Self-Management items and reliability of subscales.

Appendix 2. Factor structure HRM items and reliability of subscales.