ABSTRACT

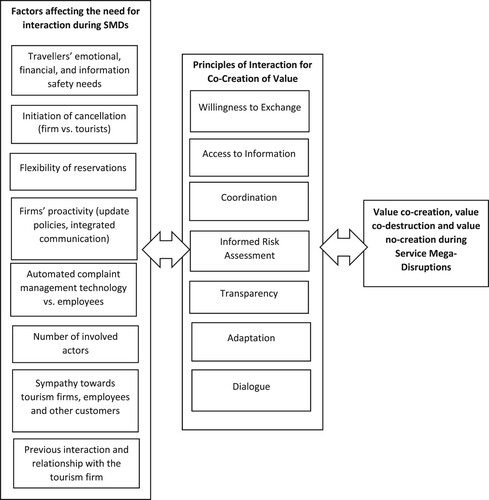

This study investigates the principles and the factors influencing interaction for resource integration during service mega-disruptions (SMDs) in the tourism ecosystem. Utilizing qualitative data from semi-structured interviews conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, this article reveals that interaction principles of willingness to exchange, access to information, dialogue, transparency, coordination, adaptation, and informed risk assessment lead to value co-creation (VCC). Failure to follow these principles leads to value no-creation (VNC) or value co-destruction (VCD). During SMDs, the most critical factors influencing interaction for resource integration are traveller’s safety needs, initiation of travel cancellation, sympathy, proactivity, omnichannel communication, the effectiveness of technology and employees as well as the number of involved actors. Forced indifference in VNC is uncovered, where firms’ constraints hinder their engagement despite tourists’ desire for interaction. This study contributes to the understanding of value dynamics during SMDs and calls for further exploration of multiple stakeholders’ perspectives in such contexts.

1. Introduction

The tourism industry is highly vulnerable to crises, including the COVID-19 outbreak, resulting in extensive travel cancellations and disruptions (Hall, Citation2010; Neuburger & Egger, Citation2021). Pandemics, such as COVID-19, cause service mega-disruptions (SMDs) in the tourism ecosystem, leading to challenges and uncertainties for tourists (Kabadayi et al., Citation2020).

Effective interaction for resource integration during SMDs is critical due to the contagion effects of travel plan changes caused by emergency conditions, fear, and frustration (Kabadayi et al., Citation2020). Unlike other services, tourists feel more vulnerable as they travel to distant destinations (Buhalis et al., Citation2019). Tourist vulnerability is exacerbated during SMDs due to constant changes, misinformation, and uncertainty (Roth-Cohen & Lahav, Citation2022). The well-being of stakeholders in the tourism ecosystem is at great risk, necessitating increased interaction for value co-creation (VCC) and avoiding value co-destruction (VCD) and value no-creation (VNC) (Sthapit & Jiménez-Barreto, Citation2019).

Empirical investigations of tourists’ interaction challenges during SMDs remain sparse within the literature. While existing studies primarily examine aspects like hoteliers’ preparedness and corporate social responsibility during SMDs (Ou et al., Citation2021; Wong et al., Citation2021), limited attention is given to the intricacies of interactional VCC, VCD, during SMDs, especially in terms of co-recovery (e.g. Assiouras et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2021; Sthapit et al., Citation2022), and VNC. The COVID-19 pandemic's impact on the tourism ecosystem, characterized as an SMD, presents a distinctive context for probing resource integration and interaction challenges due to its intricate crisis nature, ambiguous responsibilities, and profound stakeholder repercussions (Femenia-Serra et al., Citation2022).

This study investigates tourists’ interaction challenges during SMDs through interviews with tourists who have experienced COVID-19-related travel plan disruptions. VCC is closely linked with the service-dominant logic (S-D logic), which is metaphorically intricate and therefore challenging to adopt in empirical studies (Grönroos & Voima, Citation2013). Thus, our study’s theoretical foundation hinges on Prahalad and Ramaswamy’s (Citation2004) DART model, encompassing dialogue, information access, risk assessment, and transparency. Additionally, we adopt Makkonen and Olkkonen’s (Citation2017) concept that interactions involve exchange, adaptation, coordination, and communication. By scrutinizing instances where these principles fall short, our aim is to enhance the dynamics of the DART model and explore its interplay with VCD and VNC (Makkonen & Olkkonen, Citation2017).

This study contributes to the tourism literature on SMDs by enhancing our understanding of the factors that drive the need for interaction and the characteristics of successful interactions during these periods. Moreover, it extends our knowledge of the role of interaction in generating not only VCC but also VCD and VNC.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. SMDs and VCC

Kabadayi et al. (Citation2020) conceptualize SMDs as ‘unforeseen service market disturbances caused by a pandemic [which] occur on a massive scale affecting multiple stakeholders and service ecosystems simultaneously which cannot be easily recovered from’ (p. 810). Therefore, the difference between a regular service disruption and an SMD is that an SMD affects entire service ecosystems, while a regular disruption occurs on a micro-level. SMDs affect the dynamics of the value creation processes (VCC, VCD, and VNC). Government actions and policies, such as travel bans and lockdowns, disrupt service ecosystems leading to disruption of demand in the tourism ecosystem (Kabadayi et al., Citation2020).

Service-dominant logic (S-D logic) explains how VCC happens at different levels, such as individual and societal (Vargo et al., Citation2020). VCC refers to a resource integration process in which all the actors involved in the process use resources and turn them into value (Sthapit & Björk, Citation2020). However, the VCC process can be rather disharmonious and chaotic at times (Fisher & Smith, Citation2011), particularly during SMDs. VCD is the ‘interactional process between service systems that results in a decline in at least one of the systems’ well-being’ (Plé & Chumpitaz Cácaras, Citation2010, p. 431). To balance the dichotomy of VCD and VCC, Makkonen and Olkkonen (Citation2017) introduced VNC which is when there is an ‘indifference to the actor perceived value outcome’ (p. 518). Research on VNC is in general scarce, but there are some notable exceptions found in the tourism literature (see Sthapit, Citation2019; Sthapit & Björk, Citation2020).

2.2. The role of interaction in VCC during SMDs

S-D logic recognizes that VCC is an interactional collaborative process where reciprocal communication and knowledge sharing between actors is fundamental (Assiouras et al., Citation2023). SMDs disrupt tourists’ plans not only because they cannot travel anymore (e.g. travel bans) but also because their safety needs (informational, physical, financial, and emotional) are changed (Berry et al., Citation2020). During SMDs, actors of the tourism ecosystem reevaluate their resources and how to turn them into value (Assiouras et al., Citation2022). The risk of VCD and VNC is high during SMDs, so the need for effective interaction is increased (Sharples et al., Citation2022). Interconnectedness, agility, and realignment of practices protect system viability and resilience (Assiouras et al., Citation2022; Bethune et al., Citation2022) by facilitating firms and tourists to find better solutions to their disrupted travel plans and thus VCC.

The importance of actors’ abilities to activate co-creative processes has been highlighted as a fundamental precondition for VCC within the S-D logic approach (Vargo et al., Citation2020). Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004) emphasise interaction and how this facilitates VCC by pointing out dialogue, access to information, risk assessment, and transparency (DART) as building blocks. To realize VCC, there needs to be a dialogue around issues of interest to all actors, the actors need to be equal, and joint problem solvers (Williams et al., Citation2015). Hence, actors should have access to information to be able to make an assessment (risk versus benefits) of their actions and decisions. In our study, we have adopted Prahalad and Ramaswamy’s DART model (Citation2004) as a basis for our theoretical framework. Some adjustments are made by acknowledging that interaction not only leads to VCC but can also result in VCD and VNC (Makkonen & Olkkonen, Citation2017).

2.3. The role of dialogue during SMDs

Dialogue ‘require[s] deep engagement, lively interactivity, empathetic understanding, and a willingness by both parties to act, especially when they’re at odds’ (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2002, p. 10). During SMDs, upheavals in firms’ practices and customers’ needs lead to increased information asymmetry that risks disrupting VCC. Dialogue helps actors to identify more personalized solutions by facilitating knowledge sharing, learning, adaptation, coordination, and decreasing conventional information asymmetry (Seeger, Citation2006). In that way, the interaction episodes successfully lead to equitable exchanges and long-term trustworthy relationships (Makkonen & Olkkonen, Citation2017). However, there is a risk that dialogue can lead to cognitive dissonance, cynicism, and distrust, especially when dialogue is perceived as instrumentally and superficially employed (Crane & Livesey, Citation2003).

2.4. Access to information during SMDs

Consumers must access immediate and timely information (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). In the age of the ‘crisis of immediacy’, consumers expect to get content, expertise, and personalized solutions in real-time (Bethune et al., Citation2022). Tourists are likely to switch between channels (Capriello & Riboldazzi, Citation2020). The responsibility of firms is not limited to offering a multichannel approach for interaction, with little or no integration (e.g. social media chats). Firms should adopt an omnichannel approach integrating all channels, thus offering a seamless experience (Buhalis et al., Citation2020).

SMDs increase the need for accurate and timely information (Bethune et al., Citation2022). Additionally, tourists aim to find information and emotional support by using any available platform of communication with the firm (Yu et al., Citation2021). Tourists with the right information at the right time feel safer (Chemli et al., Citation2022), leading to more willingness to exchange, fewer travel cancellations, and improved revisit intentions (Yu et al., Citation2021).

2.5. Transparency during SMDs

Transparency is a necessary condition of effective dialogue (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). Transparency is defined as the open flow of information amongst stakeholders to decrease information asymmetry (Holzner & Holzner, Citation2006). When service systems are disrupted, transparency contributes to greater perceived organizational credibility, policy predictability, perceived employee effort, service quality, and positive behavioural intentions (Merlo et al., Citation2018). For instance, during SMDs tourism firms should be open about the potential risks and problems related to compensations. Signalling theory suggests that transparency is a strong signal of a firm’s goodwill (Merlo et al., Citation2018). However, during service disruptions, there are concerns that transparency can raise uncertainty and have legal consequences (Seeger, Citation2006).

2.6. Risk assessment during SMDs

Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004) argue that successful communication and dialogue are characterized by risk assessment. Transparency should enable actors’ sense-making of benefits and risks and not only be plain information disclosure (Albu & Wehmeier, Citation2014). During SMDs, actors feel more vulnerable and aim to adapt to complex situations (Buhalis et al., Citation2019). Information should be carefully balanced in terms of quality and quantity to facilitate an effective risk assessment (Bethune et al., Citation2022). Customers should feel empowered and share responsibility in the VCC process by establishing an appropriate level of expectations, building trustworthy relationships, and decreasing an overestimation of costs in comparison to benefits (Merlo et al., Citation2018). The use of simple language and targeted personalized messages based on the actors’ level of risk and efficiency are necessary for effective risk assessment, resulting in an increased willingness to exchange (Liu-Lastres et al., Citation2019). Otherwise, consumer fatigue and a lowering of sense-making capabilities will increase uncertainty, confusion, and panic (Albu & Wehmeier, Citation2014) leading to VCD or VNC.

3. Methods

This study aims to explore and understand tourists’ challenges during SMDs. It adopts an interpretative constructivist approach since it is assumed that humans construct meaning-making through their experience of the world (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2009). In-depth semi-structured interviews were used as they can generate rich data while ensuring a thematic focus and structure. Interviews allowed the researchers to explore new angles, supporting the explorative approach (Alvesson, Citation2011). Semi-interview interviews provided more in-depth knowledge and insights about tourists’ experiences of challenges related to SMDs.

3.1. Sample and data collection

Purposive snowball sampling was used to reach individuals who had experienced COVID-19-related travel cancellations. The varied backgrounds of interviewees in this study ensured the validity of the qualitative data collected (Jordan & Moore, Citation2018). The final sample of interviewees included 20 females and 17 males resulting in 37 interviewees in total (see Appendix 1). Once theoretical saturation (that point in time when it is not possible to distinguish any new insights from the interviews) occurred (Matteucci & Gnoth, Citation2017), the data collection was halted which is the reason for this specific number of interviewees. The semi-structured interviews were conducted online, via Skype or Zoom, during the COVID-19 pandemic (between March and May 2020) and were recorded in audio and video. The interviews ranged from 45 min to 70 min and the transcription consisted of 287 pages.

3.2. Analysis

Before starting coding, the authors familiarize themselves with the data by reading through the data set (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The collected data were analyzed by three authors who read and coded the material independently. The study’s aim functioned as a common point of reference and guidance for the analysis. The coding procedure was influenced by grounded theory which advocates three steps of coding: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). Open coding involves creating simple shortcodes, axial coding refers to categorizing the open codes, and selective coding involves relating the axial codes to descriptions of the studied phenomenon. This approach was chosen because it allowed the development of categories but also identified relationships between these categories (Pidgeon & Henwood, Citation1997). Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) view this as a ‘lite’ version of grounded theory since it is akin to thematic analysis and because the authors do not subscribe to the theoretical commitments that come with an ‘orthodox’ application of grounded theory.

provides an overview of the open codes, axial codes, and selective codes developed during the analysis. The coding started with open coding which was the process of constructing short and simple codes by moving quickly, yet carefully, through the data (Charmaz, Citation2006). The next step was axial coding which was the process of relating the categories identified during the open coding. The third and final step was selective coding which was the process of putting the relations between the axial codes into rich descriptions of the focal phenomena (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). Two independent researchers checked the coding.

Table 1. Open, axial, and selective codes developed during the analysis.

4. Findings

Several interaction challenges during the SMD were identified, based on data analysis. The open and axial codes have been aggregated into three selective codes: (a) getting in contact, (b) getting the right information, and (c) getting the right solution (see ).

4.1. Getting in contact

During the COVID-19 SMD, participants faced challenges in communicating with tourism firms. Lockdowns disrupted normal working patterns, and firms had to implement technology and remote work processes, resulting in reduced operational capacity. This coincided with increased demand for services, causing extremely long waiting times for contacting firms, leading to tourist annoyance. Some tourists, particularly those with lower safety needs, chose to abandon services rather than wait for hours being on hold with call centres. The difficulty in contacting firms resulted in a non-integration of resources among actors, leading to VNC if tourists were indifferent or unwilling to invest more resources (e.g. time) (Makkonen & Olkkonen, Citation2017).

“I wasn’t waiting for the money … or calling the company to return my money because I do know that companies are very slow” – Participant 7

Participants were critical of tourism firms’ preparedness, agility, and willingness to allocate additional resources, such as more employees, to provide information and assistance (Kabadayi et al., Citation2020). Particularly, participants with non-flexible/refundable reservations with airlines felt that they faced numerous obstacles and that firms failed to address their needs, leaving them stranded and stressed.

“So, yeah, in this situation, I was really pushy and … I cannot say mad, it's just like confusion because I was there and could not get home. It was desperate times.” – Participant 36

“It was really difficult to get a hold of anybody.” – Participant 1.

“It was very difficult to find somebody who could cancel my ticket. […] So, it is because you are talking with the robot.” – Participant 24.

SMDs add turbulence and complexity to tourism which in itself already is ‘hostile’ to unfamiliar destinations (Buhalis et al., Citation2019), amplifying anxiety and vulnerability among tourists. Various communication channels, including face-to-face, telephone conversations, email, and social media are used by tourists to engage with firms (Buhalis, Citation2020). The expectation is that for these channels to be integrated through an omnichannel approach that offers consistency, flexibility, personalization, and convenience in communication (Mishra et al., Citation2021).

“I felt a lot better after we had the face-to-face contact with the customer service manager at the airport.” – Participant 28

Unlike larger firms, small tourism firms maintained their communication infrastructure during the SMD, enabling access to information and meaningful dialogue due to the smaller volume of calls, emails, and cancellations. For example, small independent hotels and local tour operators demonstrated better communication abilities. Participants highlighted their positive experiences with firms that exhibited understanding, flexibility, and frequent communication. This fostered trust and had an impact on VCC.

“They said, ‘whatever happens, you will get the money back.’ (…) I think how firms respond is important. So how you communicate is important. The frequency of communication is important.” – Participant 29

“There was talk about the airlines not responding, but in fact, it is the travel agent, […] the frustration, anger, and my wife have the same feeling. We could still survive the loss of the money, but there was no contact. No consideration of us as a customer.” – Participant 19.

“The Airbnb that we booked was not a problem. Even though the ‘free’ cancelation date was over, we simply explained our situation and it was alright.” – Participant 33.

“Now we have to wait [to see what happens with the hotel bookings]. We have to ask higher up.” – Participant 28.

“I said, look, you are probably overworked due to all the complaints. I know it is not your fault. I know if I shouted at you, it is not going to make any difference, but I would like an answer. And the woman at the end of the line said, “it is really nice to speak to somebody who is not shouting at me. Hang on. I will see what I can do.” I am fairly calm about it because I know things will get settled sooner or later.” – Participant 14

4.2. Getting the right information

Tourists felt they were not adequately informed and updated about refund processes, particularly regarding their flights. This lack of immediate and timely information hinders meaningful dialogues (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). During uncertainty, consumers’ experiences are inextricably linked to the provision and foresight of emotional, financial, and information safety (Berry et al., Citation2020; Bethune et al., Citation2022).

“The communication was not the best with them because they were cancelling flights and the communication was quite “short” […] I have not received any emails from Ryanair yet about my cancellation because I asked for a refund, but still, I do not have any email that confirms the cancellation.” – Participant 4

“If the company is very passive and does not do anything, that will piss me off. But if the company shows, you know, that they do at least try to communicate and keep you updated and so on as a passenger, then you know, I will be more understanding.” – Participant 3

“We have lots of emails. And all these emails are not that clear. So the information in these emails was confusing. Full of information and full of excuses from their company but not with any practical action.” – Participant 26

“So, no one knew what was to be done or not … unprofessional. One employee saying something and the other the opposite.” – Participant 11

“I am also in a travel group on Facebook called Girls Love Travel. And that is all they talk about. Everyone has different experiences and kind of getting their suggestions and advice for how they are able to get a refund.” – Participant 1

“ … it’s a little bit confusing when most airlines and the agent are sending you kind of same emails. And whom do you respond to?” – Participant 36

4.3. Getting the right solution

Participants did not face any issues when cancelling flexible and refundable bookings. They used the websites of tourism firms (e.g. airlines, car rental, hotels), OTAs (e.g. Booking.com), or contacted local travel agents (TAs).

Tourism firms provided various solutions for cancelled travel plans, including credit vouchers, refunds, or rescheduling. However, rescheduling often held little value due to the uncertain situation (e.g. still risking quarantine when arriving at the destination), leaving participants dissatisfied with the lack of solutions.

“They gave me only two choices, going in August [2020] or 2021. A refund was not discussed.” – Participant 34

However, tourism firms primarily engaged in one-way information sharing to control interactions, disappointing participants who desired dialogue. Simply put, tourism firms adopted a mode of plain information disclosure approach (Albu & Wehmeier, Citation2014). This approach, coupled with persuasive or aggressive messaging to influence choices and discourage refund applications eroded trust and generated frustration and anger among tourists, resulting in VCD.

“Why can they not process the refunds now? You must think about that. About cashflows, I suppose, as a business or I wouldn’t like to be in that situation. But you. You should be talking to your customer.” – Participant 19

“I am not satisfied because I don’t like that they insist on the voucher, Come on. I said that I like to get a refund. Why am I rechallenge with that? Not only this. You know, I clicked on the Website because they say that you must click on the link if you want to have the refund. And then again, it talks about the voucher. Well, come on. No, I'm not satisfied with this.” – Participant 16

Some participants advocated honesty and transparency from tourism firms so they could help them by accepting a voucher or rescheduling. Moreover, if firms are transparent about their difficulties and the risks associated with various solutions it is perceived as goodwill, leading to reciprocity and VCC (Murphy & Laczniak, Citation2018).

“And they are not quite transparent about how they are doing. They are almost bankrupt because of this COVID. I read this on the news. Why don't they tell me that so I can help them.” – Participant 1.

“The customer service representative was very friendly, but she explained that based on the current firm’s policies I cannot get a refund or a voucher if I cancel my booking. In a rather honest way, she advised me to wait because many flights would be cancelled, or their departure time would be changed. If that happens, I could get a voucher. I appreciated that honesty but obviously, it wasn’t the best solution. Finally, the time of departure was changed, and I got a voucher” – Participant 34.

“Especially for paying more for the change … I wrote many emails, but they never answered. I got them on the phone once again after that but the employees at the calling centre were not informed of the necessary course of action to be taken and whether conditions would enable me to have a voucher for another flight that had a schedule change” – Participant 11

“So, Airbnb has a feature called something like. Let's say something like unforeseen circumstances, some option like that. And I said, OK, this looks interesting. So, I clicked it. I put my story and I got a full refund for all my Airbnbs” – Participant 15

5. Discussion and conclusions

5.1. Conclusion

During SMDs, tourists encounter various challenges in interacting with tourism firms which can result in VCD or VNC. First, the volume of travel cancellations increases customers’ need for interactions with tourism firms. Second, the limited proactive measures taken to introduce an SMD functional interaction system led to unsatisfactory interaction experiences characterized by reduced access to information, coordination, risk assessment, transparency, adaptation, coordination, and dialogue (see ). Sceptical tourists attribute these ineffective interactions to firms’ reluctance to engage and communicate during SMDs, particularly in the case of airlines, certain OTAs, and a few hotels.

During SMDs, the necessity of interaction is influenced by various factors, including travellers’ safety needs (informational, financial, physical, and emotional), the actor (firm or customer) initiating the travel, flexibility in travel reservations, firms’ proactivity in developing an adaptive SMD interaction system, the number of involved actors, the level of sympathy towards tourism firms and their employees, and past interaction experiences and relationships with specific tourism firms or the industry as a whole (see ). These factors not only influence the demand for interaction but also the possible paths toward VCC, VCD, and VNC.

During SMDs, customer-initiated travel cancellations are primarily driven by customers’ safety needs. Those with high safety needs aim to interact with tourism firms to cancel or modify their travel plans, thus avoiding VCD. For example, stressed customers with high emotional safety needs may desire to cancel their arrangements well in advance. Travellers who are away from home experience face the highest need for interaction. When customers have flexible reservations (e.g. refundable, rebookable without fees), they interact easily with tourism firms as they did before the SMD, typically without experiencing VCD. However, in the case of non-flexible reservations, customers with high safety needs encounter challenges and failed interactions (VCD) especially when tourism firms primarily adhere to pre-SMD interaction practices rather than implementing an SMD interaction system.

On the other hand, firm-initiated travel cancellations follow a slightly different interaction pattern for resource integration. The lack of proactivity from tourism firms in establishing SMD interaction systems becomes the main catalyst for escalating interaction episodes. Firms, especially airlines, that proactively cancel services and offer user-friendly, transparent, and adaptable methods of interaction (e.g. through websites) can bypass the need for multiple interaction episodes (e.g. chatbots, social media) and mitigate VCD. However, customer safety needs remain important in cases of firm-initiated cancellations. For instance, customers with financial safety needs, especially for expensive reservations, feel compelled to interact with tourism firms particularly when proposed solutions lead to VCD. Nevertheless, customers with a positive relationship and trust in a firm exhibit a reduced desire for interaction, especially those with moderate or low safety needs. They display patience and expect that a solution leading to VCC will be eventually reached.

In both firm and customer-initiated cancellations, travellers with high safety need to resort to multiple channels of communication due to failed interaction episodes. However, existing communication infrastructure and interaction practices (e.g. chatbots) are primarily designed for normal periods, resulting in additional failed interaction episodes. Dialogue and risk assessment prove ineffective, leading to increased VCD, even if favourable solutions (e.g. refunds) are eventually provided. For instance, customers with urgent travel needs can become trapped in a cycle of cancellations and new bookings, incurring extra costs and emotional exhaustion. Customers with lower safety needs invest less effort in interacting with firms, often simply visiting websites or making a single phone call, displaying a more indifferent approach that leads to VNC.

Human interaction with employees becomes crucial in addressing consumer tensions arising due to SMDs. Dialogue emerges as a fundamental tool for effective problem-solving and VCC. Frontline employees play an increasingly important role in facilitating dialogue, adaptation, coordination, risk assessment, and problem-solving and, ultimately, VCC, in turbulent and complex environments.

The need for interaction increases with the involvement of multiple actors in the planned travels. However, a higher number of interactions often results in a greater likelihood of failed interaction episodes due to firms’ low willingness to engage, poor coordination, and limited adaptation. For instance, reservations made through online travel agents require successful interaction between more than two actors, which may not be feasible during an SMD. Nevertheless, the presence of multiple actors does not always lead to VCD, especially when one of the actors implements an adaptive SMD interaction system that facilitates VCC. Our findings demonstrate how Airbnb and Booking.com enable interaction and VCC by offering user-friendly systems (e.g. special website sections) that allow free-of-charge changes and cancellations to their bookings during SMDs. Customers who booked through small TAs also experienced less VCD or VCC due to their long-standing trust-based relationships with them and since these TAs handled all the interactions with other tourism firms.

During SMDs, the effectiveness of interaction related to VCC is compromised. SMDs can evoke tourists’ sympathy toward tourism firms and their employees, if organizations demonstrate honesty and transparency. To some extent, tourists understand the complexities and evolving nature of the situation, which makes it challenging to establish contact with tourism firms and obtain accurate information. Nonetheless, tourists’ expectations for transparency and explanations from tourism firms increase as well. Our findings reveal that transparency during interactions can enhance tourists’ sympathy. Unfortunately, many tourism firms become less transparent during SMDs (e.g. airlines, OTAs) to safeguard their short-term financial well-being. Tourists were unethically coerced into accepting unfavourable solutions such as rescheduled itineraries or credit vouchers, which failed to protect their emotional, financial, and information safety. Overall, tourists require strong signals of goodwill from tourism firms, and failure to provide such signals results in scepticism and diminished sympathy towards them.

5.2. Theoretical contribution

This study contributes to the understanding of VCC, VCD, and VNC in the context of SMDs (Assiouras et al., Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2021; Sthapit et al., Citation2022). The findings extend the literature to highlight the role of tourists’ sympathy towards tourism firms and their employees during SMDs. Tourists’ sympathy arises from the recognition that SMDs are complex and require collaboration among all involved actors to achieve VCC. Existing literature has limited research on consumer sympathy toward tourism firms and their employees (e.g. Baker & Kim, Citation2018) and this study expands on that discussion by incorporating perspectives from VCC literature that emphasise the role of sympathy and solidarity in fostering stronger relationships and value (Roth-Cohen & Lahav, Citation2022). However, our study also demonstrates that sympathy has its limits, which can be related to discomfort and the need for reciprocal sympathy from tourism firms (Prior & Marcos-Cuevas, Citation2016). Tourists expect tourism firms to not only respond to their requests but also exhibit a deep understanding of their emotional, financial, and information safety (Berry et al., Citation2020).

Additionally, this study sheds light on the role of omnichannel communication and information and communication (ICT) technology in VCC during SMDs. While omnichannel communication is well-known for its importance in successful retailing, it has received limited attention in complaint management (Miquel-Romero et al., Citation2020) and no attention at all in the context of SMDs. During SMDs, omnichannel communication can provide tourists with access to adequate, objective, transparent, and timely information, enabling risk assessment and dialogue with tourism firms, ultimately leading to VCC. Furthermore, this study extends previous research on the role of technology as a facilitator of VCC (e.g. Čaić et al., Citation2018) by examining its impact in the context of SMDs. The findings emphasize that automated technology may lack adaptability, flexibility, and interactivity in complex and turbulent environments.

This study also relates to the concept of VNC (Makkonen & Olkonen, Citation2017; Sthapit, Citation2019; Sthapit & Björk, Citation2020), suggesting that indifference to value outcomes may be forced due to firms’ constraints rather than a genuine lack of interest. The findings suggest that tourists desired interaction and resource integrations but were unable to do so due to the firms (airlines, OTAs) not engaging in the process. Tourism firms’ apparent indifference may be a result of being on the verge of bankruptcy or having exhausted their resources, rather than a true indifference to value outcomes. VNC arguably occurred, but the tourism firms are probably not indifferent to their forced indifference. We, therefore, propose that the VNC concept should consider whether indifference is forced or not.

5.3. Practical implications

In terms of practical implications, tourism firms should develop agility and emotional intelligence to ensure humanity and solidarity during SMDs (Johnson & Buhalis, Citation2022). They should provide tourists with adequate access to information and establish a transparent dialogue to find solutions to disrupted travel plans, facilitating VCC. Clear communication through an omnichannel strategy, delivering concise and up-to-date information, is critical for keeping customers well-informed.

To effectively use limited resources in disrupted contexts, a triage assessment system (TAS) can be employed, commonly used in the health industry (Moore & Bone, Citation2017). Tourism firms should prioritize tourists facing safety deficits, such as vulnerable travellers, those stranded away from home, or with imminent departures. Technology and employees play crucial roles in a TAS system. Technology supports processes and prioritization, while employees utilize emotional intelligence and agility to co-create mutually satisfactory solutions.

Enhancing resilience, crisis management, and effective responses, require the establishment of processes and systems for SMDs are necessary (Bethune et al., Citation2022). A specific system of interaction with a cross-organization and cross-ecosystem perspective should be established pre-SMDs, prioritizing tourists with the biggest safety needs. This system should proactively and reactively evaluate and prepare for possible disruptions, facilitate emergency services and responses during crises, mitigate impacts, and empower resilience in the aftermath. Designated websites, social media accounts, video calls, chat services, and contact phone lines should be established to facilitate the co-creation of mutually agreeable alternatives.

The study also highlights the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning in enabling an effective TAS system. These technologies can prioritize information sharing, determine appropriate platforms for each traveller, and identify those customers who require more employee interaction and dialogue. Vulnerability, level of travel experience, familiarity with systems and processes, age and experience, languages spoken, and available budgets are some of the criteria to be used in the triage process. However, technology does not necessarily lead to VCC (Kirova, Citation2021). Automated chatbots should not be used to provide personalized solutions but rather direct customers to the right services. The limitations of technology in providing personalized solutions based on safety needs can be addressed by empowered frontline employees with accommodating communication styles. Therefore, hiring and training employees with flexible conditions is necessary to increase a firm’s communication capacity before an SMD occurs.

5.4. Limitations and future research

This study has certain limitations that should be addressed in future research. Firstly, it utilized a qualitative research approach, which makes it challenging to generalize the insights. To overcome this limitation, future research could utilize quantitative approaches to measure the relationships identified in our study and establish causality. Secondly, this study focused solely on the tourist perspective. Future research should adopt an approach that incorporates the viewpoints of service providers and governments as key actors. This would enable the identification of the expectations and challenges of other actors regarding dialogue, access to information, transparency, and risk assessment during SMDs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Albu, O. B., & Wehmeier, S. (2014). Organizational transparency and sense-making: The case of Northern Rock. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2013.795869

- Alvesson, M. (2011). Interpreting interviews. Sage.

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Assiouras, I., Skourtis, G., Giannopoulos, A., Buhalis, D., & Karaosmanoglu, E. (2023). Testing the relationship between value co-creation, perceived justice and guests’ enjoyment. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(4), 587–602.

- Assiouras, I., Vallström, N., Skourtis, G., & Buhalis, D. (2022). Value propositions during service mega-disruptions: Exploring value co-creation and value co-destruction in service recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 97, 103501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103501

- Baker, M. A., & Kim, K. (2018). Other customer service failures: Emotions, impacts, and attributions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(7), 1067–1085. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348016671394

- Berry, L. L., Danaher, T. S., Aksoy, L., & Keininghan, T. L. (2020). Service safety in the pandemic age. Journal of Service Research, 23(4), 391–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520944608

- Bethune, E., Buhalis, D., & Miles, L. (2022). Real time response (RTR): Conceptualizing a smart systems approach to destination resilience. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 23, 100687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100687

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buhalis, D. (2020). Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2019-0258

- Buhalis, D., Harwood, T., Bogicevic, V., Viglia, G., Beldona, S., & Hofacker, C. (2019). Technological disruptions in services: Lessons from Tourism and Hospitality. Journal of Service Management, 30(4), 484–506. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-12-2018-0398

- Buhalis, D., López, E. P., & Martinez-Gonzalez, J. A. (2020). Influence of young consumers’ external and internal variables on their e-loyalty to tourism sites. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 15, 100409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100409

- Buhalis, D., & Sinarta, Y. (2019). Real-time co-creation and nowness service: lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 563–582.

- Čaić, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Mahr, D. (2018). Service robots: Value co-creation and co-destruction in elderly care networks. Journal of Service Management, 29(2), 178–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-07-2017-0179

- Capriello, A., & Riboldazzi, S. (2020). How can a travel agency network survive in the wake of digitalization? Evidence from the Robintur case study. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(9), 1049–1052. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1590321

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Chemli, S., Toanoglou, M., & Valeri, M. (2022). The impact of Covid-19 media coverage on tourist’s awareness for future travelling. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1846502

- Crane, A., & Livesey, S. (2003). Are you talking to me? Stakeholder communication and the risks and rewards of dialogue. In J. Andriof, S. Waddock, B. Husted, & S. S. Rahman (Eds.), Unfolding stakeholder thinking: Relationships, communication, reporting and performance (pp. 39–52). Greenleaf.

- Femenia-Serra, F., Gretzel, U., & Alzua-Sorzabal, A. (2022). Instagram travel influencers in #quarantine: Communicative practices and roles during COVID-19. Tourism Management, 89, 104454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104454

- Fisher, D., & Smith, S. (2011). Cocreation is chaotic: What it means for marketing when no one has control. Marketing Theory, 11(3), 325–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593111408179

- Grönroos, C., & Voima, P. (2013). Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0308-3

- Hall, C. M. (2010). Crisis events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.491900

- Holzner, B., & Holzner, L. (2006). Transparency in global change: The vanguard of the open society. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Johnson, A. G., & Buhalis, D. (2022). Solidarity during times of crisis through co-creation. Annals of Tourism Research, 97, 103503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103503

- Jordan, E. J., & Moore, J. (2018). An in-depth exploration of residents’ perceived impacts of transient vacation rentals. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1315844

- Kabadayi, S., O’Connor, G. E., & Tuzovic, S. (2020). Viewpoint: The impact of coronavirus on service ecosystems as service mega-disruptions. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(6), 809–817. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-03-2020-0090

- Kirova, V. (2021). Value co-creation and value co-destruction through interactive technology in tourism: The case of ‘La Cité du Vin’ wine museum, Bordeaux, France. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(5), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1732883

- Liu, X., Li, H., Zhou, H., & Li, Z. (2021). Reversibility between ‘cocreation’and ‘codestruction’: Evidence from Chinese travel livestreaming. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(1), 18–30.

- Liu-Lastres, B., Schroeder, A., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2019). Cruise line customers’ responses to risk and crisis communication messages: An application of the risk perception attitude framework. Journal of Travel Research, 58(5), 849–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518778148

- Makkonen, H., & Olkkonen, R. (2017). Interactive value formation in interorganizational relationships: Dynamic interchange between value co-creation, no-creation, and co-destruction. Marketing Theory, 17(4), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593117699661

- Makkonen, H., & Olkkonen, R. (2017). Interactive value formation in interorganizational relationships: Dynamic interchange between value co-creation, no-creation, and co-destruction. Marketing Theory, 17(14), 517–535.

- Matteucci, X., & Gnoth, J. (2017). Elaborating on grounded theory in tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 65, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.003

- Merlo, O., Eisingerich, A., Auh, S., & Levstek, J. (2018). The benefits and implementation of performance transparency: The why and how of letting your customers ‘see through’ your business. Business Horizons, 61(1), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.09.007

- Miquel-Romero, M. J., Frasquet, M., & Molla-Descals, A. (2020). The role of the store in managing postpurchase complaints for omnichannel shoppers. Journal of Business Research, 109, 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.057

- Mishra, R., Singh, R. K., & Koles, B. (2021). Consumer decision-making in Omnichannel retailing: Literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12617

- Moore, B., & Bone, E. A. (2017). Decision-making in crisis: Applying a healthcare triage methodology to business continuity management. Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning, 11(1), 21–26.

- Murphy, P. E., & Laczniak, G. R. (2018). Ethical foundations for exchange in service ecosystems. In The SAGE handbook of service-dominant logic, 149.

- Neuburger, L., & Egger, R. (2021). Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 1003–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1803807

- Ou, J., Wong, I. A., & Huang, G. I. (2021). The coevolutionary process of restaurant CSR in the time of mega disruption. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102684

- Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (1997). Using grounded theory in psychological research. In N. Hayes (Ed.), Doing Qualitative Analysis in Psychology, (pp. 245–275). Psychology Press.

- Plé, L., Cáceres, Chumpitaz, R. (2010). Not always co-creation: introducing interactional co-destruction of value in service-dominant logic. Journal of services Marketing, 24(6), 430–437.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2002). The co-creation connection. Strategy and Business, Second Quarter 2002/ (27), 50–61.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

- Prior, D. D., & Marcos-Cuevas, J. (2016). Value co-destruction in interfirm relationships: The impact of actor engagement styles. Marketing Theory, 16(4), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593116649792

- Roth-Cohen, O., & Lahav, T. (2022). Cruising to nowhere: Covid-19 crisis discourse in cruise tourism Facebook groups. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(9), 1509–1525. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1940106

- Seeger, M. W. (2006). Best practices in crisis communication: An expert panel process. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 34(3), 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880600769944

- Sharples, L., Fletcher-Brown, J., Sit, K., & Nieto-Garcia, M. (2022). Exploring crisis communications during a pandemic from a cruise marketing managers perspective: An application of construal level theory. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(19), 3175–3190.

- Sthapit, E. (2019). My bad for wanting to try something unique: Sources of value co-destruction in the Airbnb context. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(20), 2462–2465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1525340

- Sthapit, E., & Björk, P. (2020). Towards a better understanding of interactive value formation: Three value outcomes perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(6), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1520821

- Sthapit, E., & Jiménez-Barreto, J. (2019). You never know what you will get in an Airbnb: Poor communication destroys value for guests. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(19), 2315–2318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1475469

- Sthapit, E., Stone, M. J., & Björk, P. (2022). Sources of value co-creation, co-destruction and co-recovery at Airbnb in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 1–28. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10 .1080/15256480.2022.2092249.

- Stoyanova-Bozhkova, S., Paskova, T., & Buhalis, D. (2022). Emotional intelligence: A competitive advantage for tourism and hospitality managers. Tourism Recreation Research, 47(4), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1841377

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Vargo, S. L., Koskela-Huotari, K., & Vink, J. (2020). Service-dominant logic: Foundations and applications. In The Routledge handbook of service research insights and ideas (pp. 3–23). New York: Routledge.

- Wilder, K. M., Collier, J. E., & Barnes, D. C. (2014). Tailoring to customers’ needs: Understanding how to promote an adaptive service experience with frontline employees. Journal of Service Research, 17(4), 446–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670514530043

- Williams, N. L., Inversini, A., Buhalis, D., & Ferdinand, N. (2015). Community crosstalk: An exploratory analysis of destination and festival eWOM on Twitter. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(9-10), 1113–1140. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1035308

- Wong, I. A., Ou, J., & Wilson, A. (2021). Evolution of hoteliers’ organizational crisis communication in the time of mega disruption. Tourism Management, 84, 104257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104257

- Yu, M., Li, Z., Yu, Z., He, J., & Zhou, J. (2021). Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 outbreak. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(19), 2699–2705. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1752632

Appendix 1

The participants’ characteristics and types of travel cancellations.