Abstract

Objective

We have reviewed the success of laparoscopic calculi surgeries in geriatric patients.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on the laparoscopic ureterolithotomy surgeries performed at our central between January 2014 and January 2019 to treat upper ureteral calculi in geriatric patients. Among the patients who underwent these surgeries, we evaluated data on 24 cases whose records could be fully retrieved.

Results

The age interval of the patients was 60–73 years, and the mean age was 63 ± 3.43 years. The size of the calculi was 19–24 mm, and mean size was 20.2 ± 2.5 mm. Because stone disease was present previously, 5 of these patients underwent endoscopic intervention, whereas two underwent open surgery. Sixteen of these patients had a history of unsuccessful shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) or ureterorenoscopy. The calculi-free rate was 100%. According to the modified Clavien classification, no major perioperative and postoperative complications were observed. The duration of hospital stay was 1–3 days, and the mean duration of stay was 1.6 ± 0.9 days.

Conclusion

We believe that owing to the high success and low complication rates, laparoscopic ureterolithotomy can be the first option of treatment for geriatric patients with impacted large calculi, with a history of unsuccessful SWL or ureterorenoscopy (semirigid, flexible).

Introduction

Aging is an inevitable process with biological, chronological, and social aspects. Owing to the increase in life expectancy and increase in the elderly population, the approach toward elderly patients has gained more importance. Urolithiasis is one of the various urological problems that affect the elderly and constitutes a significant portion of the problems that lower their quality of life.

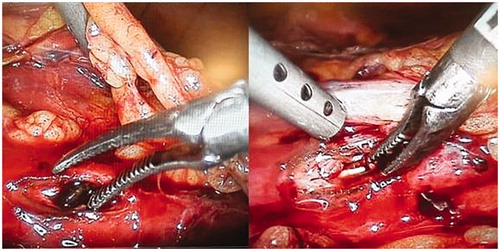

It is estimated that ureteral calculi are observed in nearly 15% of the population, and it is known that it accounts 20% of all of urolithiasis cases [Citation1]. Impacted ureteral calculi are described as stones that stay at the same site for over 2 months and cause hydronephrosis or hinder the transition of contrast matter to the distal part of the stone, as observed on intravenous urography [Citation2] (). The treatment modality of proximal ureteral calculi has changed drastically owing to the improvements in technology, endourological devices, and techniques used [Citation3]. Although it is known that compared with kidney stones, ureteral calculi are more resistant to shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) that is applied from outside the body to fragment them, SWL is still preferred as a treatment method because it is minimally invasive [Citation4,Citation5]. When SWL is ineffective, there arises a need for performing surgery for treatment. The aim of the surgical treatment of ureteral calculi is to completely eliminate stones with minimal morbidity. To achieve it, semirigid and flexible ureterorenoscopy can be sufficient in most cases, whereas open surgery, laparoscopic ureterolithotomy, and antegrade percutaneous methods can be required for large and impacted proximal ureteral calculi [Citation6] (). Owing to major developments in the field of endourology, minimally invasive surgeries have replaced open surgeries in the treatment of large upper ureteral calculi. This study reviews the success of laparoscopic calculi surgeries in geriatric patients. These surgeries have been described as the principal method to be preferred, rather than just an option, since the 2012 European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines.

Materials and methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on the transperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy surgeries performed at the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Training and Research Hospital between January 2014 and January 2019 to treat impacted upper ureteral calculi in patients >60 years of age. This surgical method has been preferred owing to the presence of impacted proximal ureteral calculi in all patients who underwent laparoscopic ureterolithotomy. Patients with radiopaque-impacted proximal ureteral stone of >15 mm that was separately measured via computed tomography and intravenous pyelography and those who had a stone localized at the upper border of the ureteropelvic junction and the 4th lumbar vertebrae were defined as patients with impacted proximal ureteral calculi. Among these, patients with unilateral kidney stone were excluded from the study.

All patients had undergone noncontrast computed abdominal tomography. Whether the stone was opaque was confirmed directly via radiography. Complete urinalysis, urine culture, antibiogram, serum creatine level measurement and coagulation profiles of the patients were requested, and the results were evaluated. The aforementioned exclusion criteria were applied, and 24 cases with fully accessible records were assessed.

Results

Overall, 24 geriatric patients underwent transperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy. The age interval of the patients was 60–73 years, and the mean age was 63 ± 3.43 years. Five (20.8%) of these patients were female, whereas 19 (79.2%) were male. The size of the calculi was 19–24 mm, and their mean size was 20.2 ± 2.5 mm. Because stone disease was present previously, five patients underwent ureterorenoscopy (URS), whereas two of them underwent open surgery. Sixteen (66.6%) of these patients had a history of unsuccessful SWL or URS. The mean duration of the surgery was 90.8 ± 12.1 min. Nineteen (79.1%) of the patients had an intraoperative DJ stent placed in them. According to the planned calculi surgery, the calculi-free rate was 100%. No major perioperative and postoperative complications were observed. According to the modified Clavien classification, 21 patients were reported to be grade 1, whereas three patients were reported to be grade 2. The duration of hospital stay was 1–3 days, with a mean of 1.6 ± 0.9 days (). Ureteral stricture was not observed in any of the patients during the intravenous pyelography follow-up, which was performed 3 months later.

Table 1. Patient demographics and surgery characteristics.

Discussion

Worldwide, the aged population is increasing. As a natural consequence of this, health problems and diseases have become more common. WHO also estimates that by 2025, nearly 1.2 billion individuals will be over the age of 60 years, and by 2050, the elderly age population worldwide will reach 2 billion, with 80% of this elderly population living in developing countries [Citation7].

Urolithiasis is one of the common causes of hospitalization among geriatric patients. Considering that complicating factors are observed more frequently in geriatric patients, determining the suitable treatment for these patients and commencing it immediately is of great importance for avoiding potential serious complications [Citation8]. In cases in which primary treatment options – URS, SWL, or percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL) – are unsuccessful or expected to be unsuccessful, laparoscopic surgery can be performed if the surgeon has an adequate level of experience in surgery of upper and middle ureteral calculi. In up-to-date guidelines, laparoscopic surgery is an alternative to open surgery that is recommended as a treatment modality for treating urolithiasis in selected cases or in cases in which other treatment methods have failed.

SWL and URS are the most preferred methods for treating ureteral calculi [Citation3]. Moreover, preferable treatment modality of large upper and middle ureteral calculi is a subject of debate [Citation9]. Especially in impacted calculi, SWL and URS have lower rates of success; in cases in which the stone size is >1 cm, the effectiveness of SWL decreases from 84% to 42%. Although 7% of ureteral calculi cases treated endourologically require a repetition of the treatment, open surgery might be required in 1–10% of these cases [Citation10]. In such patients with complications, open surgery is advantageous owing to its high success rate in one session/application. However, open surgery prolongs the hospital stay and requires additional analgesic treatment. The success rate of laparoscopic ureterolithotomy is the same as that of open surgery and can even be considered superior to open surgery in terms of reduced need for analgesics, shorter hospital stay, and positive recovery and cosmetic results [Citation11–13]. According to the EAU Guidelines, indications for laparoscopic calculi surgery include the presence of large impacted ureteral calculi, failure of minimally invasive procedures, different surgical needs for a concurrent indication, and technological shortcomings [Citation14].

URS is undoubtedly the least invasive surgical method for large upper ureteral calculi. It is superior in terms of the operation time, blood loss, and hospital stay; however, the success rate of URS in terms of stone-free results is lower than that of laparoscopic surgery [Citation15]. Moreover, in procedures such as URS and PNL, the associated risk of sepsis is higher than that associated with the laparoscopic method in cases of impacted calculi owing to the increase in pressure that occurs in the collecting duct system. It is known that the intraureteric pressure at rest is 0–5 cm H2O. Urosepsis that might occur postoperatively owing to the increase in pressure is caused by the liquids administered to the closed system during surgery; therefore, the laparoscopic method can be considered as a step ahead of the other methods.

Neto et al. previously compared SWL and semirigid URS in a total of 24 patients who underwent laparoscopic ureterolithotomy as a primary or salvage treatment method for upper ureteral calculi of 8–33 mm; they determined the success rates of these methods to be 35%, 62%, and 93%, respectively. The said study also reported that the requirement for additional procedures was less for treatment in patients who underwent surgery via the laparoscopic method [Citation9]. In another study, Ko et al. compared data from 71 patients who underwent laparoscopic ureterolithotomy in whom the laparoscopic procedure was performed for upper ureteral calculi of >15 mm without first attempting SWL and URS with data from 32 patients in whom semirigid URS/pneumatic lithotriptor were used to fragment calculi of similar sizes during the same period. In this study, it was found that in primary treatment of upper ureteral calculi, the stone-free rate was significantly higher in patients who underwent laparoscopic ureterolithotomy than URS (93% vs. 68%) [Citation16].

Laparoscopic surgery performed for ureteral calculi can be performed retroperitoneally or transperitoneally. Studies conducted to date have not demonstrated the superiority of one approach over the other. In a randomized prospective study in which both approaches were compared, it was concluded that their success rates are similar. However, in patients who underwent the procedure transperitoneally, pain, need for analgesics, incidence of ileus, and duration of hospital stay were found to be significantly higher [Citation17].

Advantages of the transperitoneal approach are that it ensures a larger working site, better visibility, and better definable anatomical markers [Citation18]. The most significant disadvantage of the retroperitoneal approach is the limited working site. Apart from this disadvantage, there is no need for colon mobilization, and the risk of visceral organ damage is still lower via the retroperitoneal approach than via the transperitoneal approach. Furthermore, the risk of peritoneal cavity contamination owing to postoperative urinary incontinence and rate of postoperative ileus are lower via the retroperitoneal approach [Citation11,Citation19].

Our study was compatible with the literature in terms of the stone-free rate. Considering that the average calculus size was nearly 20 mm, it can be seen that the mean duration of the surgeries was relatively short in our study. In healthcare centers, such as ours, that have an adequate amount of laparoscopic surgery experience, performing laparoscopic ureterolithotomy provides a significant advantage in terms of operation times for large impacted calculi. No major perioperative or postoperative complications were observed in any of the patients. According to the modified Clavien classification, 21 patients were reported to be grade 1, whereas three patients were reported to be grade 2. As anticipated, the duration of hospital stay reported for laparoscopic ureterolithotomy was longer than that reported for URS but rather shorter than that reported for open ureterolithotomy. However, the low number of cases and retrospective design are the limitations of our study.

Conclusion

Although SWL and URS are considered as primary treatment options, retroperitoneal or transperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy can be preferred as an efficient and reliable treatment method especially for treating impacted and large ureteral calculi and in patients in whom primary treatment methods have failed. Especially in geriatric patients, laparoscopic ureterolithotomy is a preferable safe option because it ensures stone-free results in one session and does not increase the intraurethral pressure. Taking into account the small sample size of our cohort, well-designed studies with a larger sample size are needed to confirm our results.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Randomized trial of efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2005;174:167–172.

- Goel R, Aron M, Kesarwani PK, et al. Percutaneous antegrade removal of impacted upper-ureteral calculi: still the treatment of choise in developing countries. J Endourol. 2005;19:54–57.

- Segura JW, Preminger GM, Assimos DG, et al. Ureteral Stones Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on the management of ureteral calculi. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997;158:1915–1921.

- Anderson KR, Keetch DW, Albala DM, et al. Optimal therapy for the distal ureteral stone: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy. J Urol. 1994;152:62–65.

- Eden CG, Mark IR, Gupta RR, et al. Intracorporeal or extracorporeal lithotripsy for distal ureteral calculi? Effect of stone size and multiplicity on success rates. J Endourol. 1998;12:307–312.

- Grasso M, Bagley D. A 7.5/8.5 French actively deflectable, flexible ureteroscope: a new device for both diagnostic and therapeutic upper urinary tract endoscopy. Urology. 1994;43:435–441.

- Kalache A, Gatti A. Active ageing: a policy framework. Adv Gerontol. 2003;11:7–18.

- Akbari NR. Percutaneous nephrolithotripsy complication in the elderly. Aging Male. 2007;10:77–87.

- Lopes Neto AC, Korkes F, Silva JL, et al. Prospective randomized study of treatment of large proximal ureteral stones: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus ureterolithotripsy versus laparoscopy. J Urol. 2012;187:164–168.

- El-Moula MG, Abdallah A, El-Anany F, et al. Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: our experience with 74 cases. Int J Urol. 2008;15:593–597.

- Feyaerts A, Rietbergen J, Navarra S, et al. Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy for ureteral calculi. Eur Urol. 2001;40:609–613.

- Soares RS, Romanelli P, Sandoval MA, et al. Retroperitoneoscopy for treatment of renal and ureteral stones. Int Braz J Urol. 2005;31:111–116.

- El-Feel A, Abouel-Fettouh H, Abdel-Hakim AM, et al. Laparoscopic transperitoneal ureterolithotomy. J Endourol. 2007;21:50–54.

- Turk C, Knoll T, Petrik A, et al. EAU guidelines on urolithiasis. Vienna, Austria: European Association of Urology; 2011.

- Zhu H, Ye X, Xiao X, et al. Retrograde, antegrade, and laparoscopic approaches to the management of large upper üreteral stones after shockwave lithotripsy failure: a four-year retrospective study. J Endourol. 2014;28:100–103.

- Ko YH, Kang SG, Park JY, et al. Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy as a primary modality for large proximal ureteral calculi: comparison to rigid ureteroscopic pneumatic lithotripsy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:7–13.

- Singh V, Sinha RJ, Gupta DK, et al. Transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: a prospective randomized comparison study. J Urol. 2013;189:940–945.

- Harewood LM, Webb DR, Pope AJ. Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy: the results of an initial series, and an evaluation of its role in the management of ureteric calculi. Br J Urol. 1994;74:170–176.

- Gaur DD, Rathi SS, Ravandale AV, et al. A single-centre experience of retroperitoneoscopy using the balloon technique. BJU Int. 2001;87:602–606.