ABSTRACT

Nordic countries are considered international leaders in producing combinable data on their citizens’ encounters with public institutions, as well as the digitalisation of public services. Public-sector professionals increasingly collaborate with private IT companies in developing data analytics products for cost saving and cost-efficiency. This article presents the results of a two-year ethnographic study of a collaboration between the Knowledge Team of a public-sector organisation and a private-sector IT company for developing and maintaining a data management system in one Finnish regional healthcare and social service organisation. The data management system is defined as a data analytics product that provides management with information about clinical and financial aspects of organisation management. We combine perspectives of science and technology studies and the sociology of professions to situate our research on the data management system as a boundary object within the broader context of professional work. Via our theoretical framework, we examine the negotiation process through which the data management system becomes a boundary object in practice. This process includes not only the accommodation of diverse epistemic cultures but also organisational and professional hierarchies that empower some experts to shape the data management system towards their visions and interests. This article applies the ‘boundary object’ concept to elucidate structural power differentials in public–private partnerships and multi-professional collaborations.

Introduction

Recent developments in data-driven healthcare and social services have increasingly shifted attention to the data analytics industry and to public–private partnerships that aim to build data analytics products for the public sector. The data analytics industry and its products are expected to solve cost-effectiveness problems (Beer, Citation2018; Dencik et al., Citation2019). The need for public healthcare and social services to better manage costs and compensation has intensified business opportunities for IT and analytics companies (Hogle, Citation2016). Research on data analytics products provides important insights into knowledge production in public healthcare and social services.

Data analytics is also on the agenda in Finland, with efforts made to address the cost pressures and efficiency needs of public healthcare and social services by developing models for so-called knowledge-based management (with the slogan ‘leading with knowledge’); here, decision making is guided by data analytics–derived information (e.g., Kivinen & Lammintakanen, Citation2013; Leskelä et al., Citation2019). Data management systems (DMSs) are examples of data analytics products that provide management with information about clinical and financial aspects of organisations’ management. These systems focus on creating business value out of healthcare and social service data via online dashboards to allow different types of end users to track, for example, patient flows, treatment decisions, paths, outcomes and costs in real time. The emphasis is on establishing patterns and trends, which may lead to minimalisation of costs and improvement of treatment outcomes.

In this article, we study the case of a public–private partnership in which a public organisation partners with a private-sector IT company to develop a DMS based on a new experimental idea of comparable healthcare and social data in what are called Social and Healthcare Information Packets (SHIPs). For healthcare and social service organisations, SHIPs have introduced a new reporting model that has been developed by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, as well as the Finnish Innovation Fund (SITRA) since 2015 (Helén, Citation2019; SITRA, Citation2016; Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö, Citation2020). The DMS utilises healthcare, social services and financial data, which are extracted from separate electronic patient healthcare information systems, customer social service information systems and financial systems. The DMS visualises, for example, trends and patterns of service usage, patient flows and total costs within and between public-sector organisations, units and municipalities. Yet, as we demonstrate below, the production of these data analytics appears laborious and difficult in practice because of continual challenges linked to extraction and integration of different types of data and a vast number of simultaneous developments requested and coordinated by different actors, among other reasons.

Because the DMS has been developed in a multi-professional public–private partnership involving IT experts, medical experts, software developers, data workers in healthcare and social services, and project managers, among other relevant actors, we bring together science and technology studies (STS) and the sociology of professions (Abbott, Citation1988, Citation2005) to situate our study on the DMS as a boundary object (Bowker & Star, Citation1999; Star & Griesemer, Citation1989) within a broader context of professional work and power dynamics among experts. Our study unpacks the organisational and professional power relations and hierarchies in the public–private partnership and multi-professional collaboration and captures the mechanisms through which particular interests and visions are inscribed into data-driven technology. Our research also advances the scant scholarship on the products of the data analytics industry that crucially influence how data are utilised in decision making in healthcare and social services (Beer, Citation2018). It enhances the theoretical and empirical understanding of the DMS as a boundary object over time and across boundaries in public–private partnerships, as well as professionals’ contributions to public–private partnerships and multi-professional collaboration.

Here, we first present the theoretical framework, consisting of the concepts of boundary objects and boundaries in the STS and sociology of professions literature. Second, we present the ethnographic methodology. Third, drawing on our empirical materials, we depict how the DMS as a boundary object is enacted in collaborative practices and what kinds of power dynamics are involved in its making. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of our findings for further research on public–private partnerships and DMSs.

Boundary objects and boundaries in public–private partnerships

We approach the case DMS as a boundary object that brings together different expert groups. Star and Griesemer (Citation1989) conceptualised a ‘boundary object’ to capture how scientists balance different categories and meanings. The concept continues to attract scholarly interest across research topics, such as in information systems (e.g., Doolin & McLeod, Citation2012), health care (e.g., Keshet et al., Citation2013), education (e.g., Seale et al., Citation2015), software development teams (e.g., Barrett & Oborn, Citation2010) and innovation and design processes (Clausen & Yoshinaka, Citation2007).

Star and collaborators (Bowker & Star, Citation1999; Star & Griesemer, Citation1989) emphasised the inclusive aspects of boundary objects, where artefacts fulfil a bridging function between diverse communities of practice and their divergent viewpoints. Boundary objects enable collective action that rests on knowledge sharing and production across different groups without the need to reach a consensus. For Star and her collaborators, boundaries emerge as conditions for communication, inclusion and exchange when collaborators need to interact with each other’s differential but intersecting social worlds. This perspective enhances a relational and ecological approach to knowledge sharing and production sensitive to symbolic strategies, for example, in defining the content and institutional contours of actors’ professional activity.

In a later article, Star (Citation2010) discussed the three components of boundary objects—namely, interpretive flexibility, the structure of work process needs and arrangements and the dynamic relationship between ill-structured and better tailored uses of the objects. Interpretive flexibility refers to boundary objects’ elasticity in satisfying the informational requirements of several communities. As Star and Griesemer (Citation1989) explained:

Boundary objects are plastic enough to adapt to the local needs and constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites. They are weakly structured in common use and become strongly structured in individual-site use. (p. 393)

We also apply Abbott’s (Citation1988, Citation2005) ecological perspective on professional life to capture the power dynamics between experts and different professions as part of a competitive but relational system of expert labour. Abbott’s (Citation1988, Citation1995, Citation2005) approach to professions advances the theorisation of the boundary object; it does so by providing such tools as boundaries to understand the interrelatedness of different groups of experts seeking resources, alliances and support across ecologies of professions as they vie to control access to expertise and shape boundary objects in their interests in the public–private partnership. Abbott’s approach is also useful for understanding the temporal development of collaborative relations between experts, which involve competition and struggle alongside inclusion and knowledge sharing (Abbott, Citation1988; Waring & Latif, Citation2017).

In this article, we show how the theorisation and use of the boundary object can be fruitfully enriched by Abbott’s ecological perspective to examine how technical systems like DMSs are enacted via organisational and professional hierarchies in a multi-professional public–private partnership. The undemocratic dynamics of professional power involving, for example, gendered hierarchies in health care are well recognised (Kuhlmann, Citation2006; Wrede, Citation2008). The boundary work (Gieryn, Citation1983) of professionals often focusses on maintaining, defending and expanding claims to professional jurisdiction over specific tasks within professional knowledge systems. Various forces – both internal and external – create potentialities for gains and losses of jurisdiction. Professions seise openings and reinforce or cast off their earlier jurisdictions. Each jurisdictional event that happens to one profession pushes adjacent professions into new openings or new defeats (Abbott, Citation1988, Citation1995). In his later theorisation of ‘linked ecologies’, Abbott (Citation2005, p. 248) highlighted the three following components of an ecology: actors, locations and the relations between them. He stressed that the competitive boundary work of professionals often involves balancing between bridging and creating boundaries to achieve common goals. Bridging can be enhanced by such mechanisms as ‘hinges’ and ‘avatars’. Hinges provide dual rewards for actors from different ecologies (Abbott, Citation2005, p. 255), as does the DMS in our study. Avatars are ‘institutionalised hinges’ that represent the interests of one ecology in an adjacent ecology (Abbott, Citation2005, pp. 265–266). In our research, we consider individual professionals to be avatars whose double ecology memberships or professional moves from one ecology to another create alliances between ecologies. These avatars enable and sustain common practices around the DMS via their highly appreciated expertise and dominant organisational positions.

The DMS in the making operates as a boundary object that unites divergent intersecting social worlds of experts from public- and private-sector organisations because of shared interests. Yet, the collaboration on the DMS also implies competing interests that influence the shaping of the DMS, as we explore below in terms of boundary processes. We suggest that power dynamics and hierarchies are salient dimensions of public–private partnership and multi-professional collaboration that are deeply materialised into data-driven technologies.

Ethnographic methodology

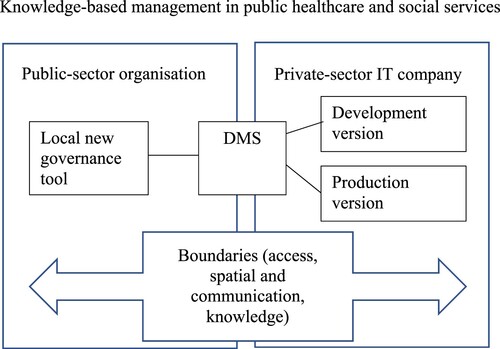

This article is based on a two-year ethnographic fieldwork study conducted at a Finnish regional healthcare and social service organisation, where we followed the construction of data-driven technologiesFootnote1, in which a public-sector organisation and a private-sector IT company served as collaborators. Access to software development processes involving private businesses proved difficult (Kitchin, Citation2017; Seaver, Citation2017), and our first attempt to access a public–private partnership, which included a large international IT company, was rejected. Thus, we made a second attempt via a public-sector organisation where we had already been conducting fieldwork, through which we knew about the DMS collaboration with the company and the collaborative meetings. In the first phase, we gained access to the development meetings, and a little later, we attended the maintenance meetings. The former focussed on developing new features for the DMS and the latter on maintaining the version in production (see ). Both were chaired by the IT company’s experts and organised every second week via conference calls. The number and composition of participants varied depending on the agenda, among other things. The IT company expert team was represented by at most six experts working as managers and software developers, and occasionally, experts from the subcontractor. The Knowledge Team of the public-sector organisation consisted of about 16 experts working as middle managers, data workers in healthcare and social services, IT architects, subject experts (e.g., in SHIPs) and software developers. Still, only five Knowledge Team members and two medical expertsFootnote2 participated regularly in the collaborative meetings.

Table 1. Collaboration.

As we accessed the work on DMS through the customer organisation, we could not gain insight into the DMS design or power dynamics in the work organisation at the IT company as well as between the IT company and other customer organisations. Thus, these aspects are covered in less detail here. Our access to the research site was also gradual and selective. We did not get access to everywhere at once, but rather it was continuously negotiated in our communication with the Knowledge Team members and their managers. These access constraints impacted on the current focus of our paper that highlights the ways in which power dynamics surfaced in the discussions and negotiations on various components and updates of the DMS, work division, interests around its functioning and prioritisation of development needs, to mention just a few aspects. The meetings’ online character facilitated access to them. It also made our participation and note taking less visible, and thus, less disturbing for others than if we had been in the same room.

In this article, we mainly draw on our fieldnotes on collaboration produced by observing about 120 h of collaborative meetings, Knowledge TeamFootnote3 meetings, training in the use of the DMS and daily data work taking place from early 2019.Footnote4 Our ethnographic practice of ‘being there’ (Pritchard, Citation2011) involved both authors’ co-presence (Beaulieu, Citation2010) during most collaborative meetings, team(s) meetings and team members’ daily work. We observed them together or separately in shared physical or virtual spaces during the meetings, between the meetings, before and during trainings they organised and working in their workstations or offices.

Our data analysis was guided by the following research questions:

How does the DMS bring together different groups of experts and provide conditions and space for collaboration?

How do experts draw on power relations to influence the negotiation of the meanings of DMS towards their interests?

To answer these questions, we conducted theory-driven thematic data analysis (Ryan & Russell, Citation2003). Data analysis proceeded in four stages. First, all observation notes were thoroughly read, and all relevant passages linked to the concepts of a DMS as a boundary object and boundaries among expert groups were copied into the article manuscript. Second, the relevant passages were re-read in relation to the collaborators’ visions of the DMS. Third, the passages were re-read in relation to professional dynamics and hierarchies among experts. This stage of analysis resulted in identifying the three following types of boundaries and their impact on the DMS: access, spatial and communication, and knowledge boundaries. Finally, we re-analysed the material to capture the temporal dimension of collaboration and boundaries.

Results

Our results are structured on two interrelated issues. First, we discuss how DMS was enacted as a boundary object by each collaborator. Then, we examine how the identified boundaries affected the shaping of the DMS.

The data management system as a boundary object

Like boundary objects (e.g., Star & Griesemer, Citation1989, p. 408), the DMS was simultaneously abstract and concrete, standardised and customised, general and specific. Akin to many technical systems, it had never become a finished product (Johnson & Verdicchio, Citation2017). The DMS’s elasticity in satisfying the informational requirements of several collaborators was linked to enacting different versions of the DMS (see ). The IT company mobilised two versions, which we call a production version and a development version. The production version was the most current version of the DMS that was sold to customers and possibly configured for each customer organisation to meet the data and local needs. In this way, the production version served as a local new governance tool for customer organisations. Simultaneously, the development version was continuously developed with the collaborating customer organisation. Thus, the DMS became internally heterogeneous to accommodate diverse epistemic cultures without needing a consensus among the collaborators (Star & Griesemer, Citation1989).

Our interviews with the IT company’s expertsFootnote5 revealed that the first DMS prototypes from the mid-2010s brought about symbiotic relationships between the collaborators. Yet, this version was based on developments from the 1990s. As the collaboration started a few years before our fieldwork, we focus on the versions of the DMS and power dynamics at the current phase of collaboration. The studied public organisation was one of the first customer organisations in which management perceived the DMS as a promising governance tool that could enhance the ongoing re-organisation of public service delivery in this hospital district. The collaboration between the IT company and public organisation appeared to be a win-win solution: The public organisation had no resources or expertise to build the tool, whereas the IT company had limited expertise about the analytical needs and data of Finnish public healthcare and social services. National-level developments, such as the Finnish Innovation Fund’s experiment on the development of comparable healthcare and social data in the form of SHIPs, have provided a novel direction for the development of DMS since 2016 (SITRA, Citation2016; Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö, Citation2020).

Since the beginning of the collaboration, the companies have changed remarkably, including in ownership and market expansion. When our fieldwork started, the organisation of DMS production was divided into two different but intersecting projects at the company, supported by collaborative meetings (see ). These meetings created a temporarily limited socio-technical space (Clausen & Yoshinaka, Citation2007; Pedersen et al., Citation2020), where the intensive negotiation, sharing and translation of knowledge between collaborators took place. In this collaboration, supported by management and medical experts, the Knowledge Team represented the interests of the public healthcare and social service organisation. The team had two main aims, which were as follows: (a) to tailor the development version of the DMS to the context-sensitive needs of the organisation and (b) to ensure proper functioning of the production version regarded as the new local governance tool.

The first task expressed the needs of powerful actors within the public organisation. Effort was made to develop new data analytics and visualisations to facilitate data-informed decision making in the organisation. Here, new DMS features, and their configurations were requested, discussed, planned and developed. Because the DMS was pricy for the public organisation, management was pressured to influence its development such that it would provide insights into ways to make current and future delivery of public services more cost-efficient. For example, the Knowledge Team members expected the data analytics to enable continuous improvements through intensive measurement and comparison, for example, of treatment results and costs at the level of the organisation, the unit or even the individual professional (Fieldnotes, 17 April 2019).

The public organisation’s needs were particularly heterogeneous because they came from different sources, such as top management, the financial administration, various hospital units, healthcare centres and municipalities. The Knowledge Team strove to prioritise the inquiries and translate them into development ideas before passing them to the IT company to seek technological solutions. It became clear that the Knowledge Team exercised power to determine which aspects and whose interests were considered during the development work (Levina & Vaast, Citation2005; Thomas et al., Citation2008). The development version of the DMS appeared to reflect the choices, interests and futuristic visions of powerful actors within and between the collaborating organisations. We also observed that the organisations did not influence the development of the DMS equally. For instance, many development ideas that were central to the public organisation lagged behind the schedule or were not developed sufficiently.

The second task of the Knowledge Team, which aimed at ensuring the proper functioning of the production version, reflected the needs of the Knowledge Team members and other groups of professionals in the organisation. Here, the Knowledge Team also functioned as a voice for different groups of users reporting problems with the system. Maintenance meetings focussed on overall service management and resolving, for example, service tickets covering bugs and improvements. Some tickets were resolved in an ad hoc fashion under strong time pressure. The DMS was also continuously enlarged with new data. Every month, three to five Knowledge Team members spent time validating new loading of data into the DMS. The existing features were also constantly updated under the changing national regulations.

Boundaries and power dynamics

Our analyses pinpoint three types of boundaries – access, spatial and communication, and knowledge boundaries – that affected the shaping of the DMS in line with the interests and visions of collaborating organisations.

Access boundaries

Access boundaries include the two following dimensions: (a) inclusion or exclusion from the collaborative meetings and other forms of communication between collaborating organisations and (b) differential user rights to different components of the DMS. The expert team of the IT company arranged, thematically framed and distributed the meeting invitations to carefully selected Knowledge Team members perceived to have crucial expertise. Over time, the IT company experts loosened the policy and allowed the Knowledge Team members and the medical expert some right to invite participants. Because of his high hierarchical position and his professional knowledge of medical practice and technological needs of the organisation, the medical expert exercised the most power to control access (and user rights from the Knowledge Team). We even witnessed a situation in which the medical expert decided who must leave the meeting and move on to other tasks.

The organisational hierarchies enabled professional power dynamics in the access to and representation of different groups of experts in the meetings (see ). The expertise of professionals that belong to well-organised professions with well-defined jurisdictions (see Abbott, Citation1988) and technical expertise (Susskind & Susskind, Citation2015), such as the medical profession and IT experts, were better represented and their expertise sought during the meetings. Moreover, these experts strongly advocated for the interests of the financial administration and the top-level management of the public-sector organisation. Other experts with more diverse and less-defined jurisdictions that involved more women’s work (e.g., data workers in healthcare and social services) were either unrepresented or underrepresented in the collaboration. Our results indicate that there are gendered power relations not only among healthcare experts (Wrede, Citation2008) but also between healthcare and social services, as well as in organisations involved in the building of the DMS.

Professional disparities were especially visible in the development meetings that focussed on new features of the DMS. Throughout the fieldwork, the medical expert offered hints about some private meetings between him, top management, a few Knowledge Team members and the IT company experts; he suggested that, during these meetings, some particular development ideas, such as a secret version of data analytics only for the superiors, were discussed (Fieldnotes, 20 May 2020). This suggests that some central developments were agreed on in meetings that we could not access.

The IT company experts exercised power in predominantly distributing DMS testing rights to medical experts and key Knowledge Team members. This endorsed these experts’ domination of the shaping of the DMS. Other Knowledge Team members had to inquire about testing rights separately, but because of their heavy workloads, they seldom did.

The Knowledge Team, including the medical expert, exercised power to determine the technical affordances designed for end users in terms of which data analytics different types of users could access. For example, a situation arose where a Knowledge Team member informed the company that a particular group of users did not need to know about certain analytics. The medical expert supported her opinion by adding, ‘It is a matter of hygiene that they do not see too much data’ (Fieldnotes, 22 April 2020). The legislation on data protection was only briefly mentioned in the meetings and rarely used as a reason for access rights restrictions.

Spatial and communication boundaries

The collaboration was distributed spatially and communicatively and was performed in different physical and online locations. For example, the expert teams involved in the collaboration could be located in different cities, buildings or floors of the same building. These spatial boundaries were bridged by communication technologies (e.g., email, phone, Skype and Teams).

During collaborative meetings (see ), the Knowledge Team hardly ever disturbed the pre-planned agenda of the meetings by shaping the discussions towards team needs and interests or asking more actively for access to testing new features under development. The overall pattern in the meetings was that one to three Knowledge Team members and medical experts participated actively and most listened to the meetings and spoke only when asked something. We noticed that their silence was partly caused by their lack of access to DMS testing. Collaborative meetings were centred on the Knowledge Team members’ inquiries about the schedules of new DMS releases or features so that they could better manage their usual work, and the Knowledge Team’s sharing of development ideas. Yet, the IT company’s expert team was often unable to provide an exact timeline or meet the agreed schedules.

The continual organisational changes in the public-sector organisation influenced communication. It appeared that some experts were carefully selected to participate in some meetings, while others were excluded. Furthermore, the tight schedules of a few key Knowledge Team members affected the agenda and length of the meetings; for instance, some issues were postponed to later meetings or delegated to discussion via informal communication channels. Yet, the IT company experts were the ones who made these decisions. They also flexibly cancelled the meetings without longer explanations, which significantly decreased the number of formal collaborative meetings. Further, they controlled communication with subcontracting companies responsible for particular DMS components.

The communication patterns changed over time. Communication seemed to deepen as the experts came to know each other better, which enhanced knowledge sharing in the pursuit of better technological solutions. Besides the formal meetings, a few Knowledge Team members were in regular contact with the IT company experts because they had expertise essential to the DMS development. They appeared to have more possibilities to influence DMS development. Over time, the medical expert became more demanding and impatient about this development. He criticised the IT company for the slow pace. Yet, communication appeared exceptionally difficult when the expert team of the IT company was unfamiliar with the substance of the Knowledge Team’s work:

Medical expert decisively reminds the project manager of IT company about the crucial development being on hold for half a year. Then he continues to explain how a requested feature should work and asks whether the software developer from the IT company gets the idea.

The software developer of the IT company replies, fairly puzzled, ‘No, I am not sure because I am not familiar with the practices behind it.’ (Fieldnotes, 6 May 2020)

Knowledge boundaries

Knowledge boundaries represent different types of knowledge recognised as exerting power in the collaboration, including the following: (a) technical expertise, (b) knowledge of SHIPs, (c) understanding of patient and financial data and the data repository of the public organisation, (d) medical expertise and (e) less recognised expertise in social work and its customer data. For the IT company, the pattern was clear: Project managers were in charge of formal collaboration meetings, supported by software architects and developers. The latter were often responsible for demonstrating new features or system updates in the making to the Knowledge Team. The IT company’s experts were especially keen to hear the Knowledge Team’s development ideas, needs and feedback on the ongoing developments, especially from the medical experts and a key Knowledge Team member with know-how in SHIPs.

The knowledge boundaries were visible between the IT company experts and the Knowledge Team and among the Knowledge Team members. For example, the technological solutions by the IT company’s expert team were often implicitly and sometimes explicitly criticised by the medical expert because of their unsuitability for clinical management or being on hold for six months. One collaborative meeting was particularly marked by the medical expert’s discontent – as a representative of the paying customer organisation – with the pace of development. While the Knowledge Team member failed to deliver information central to the project progression because of his other work tasks, the medical expert blamed the IT company experts for the slow progress (Fieldnotes, 6 May 2020).

The Knowledge Team expected the IT company experts to solve practical problems by providing technology, but the IT company experts were often unable to understand and respond to the Knowledge Team’s needs because of a lack of expertise in medical and social services, as well as rather vaguely formulated developmental needs. Thus, the continuous assistance of certain Knowledge Team members was required to provide well-defined datasets and explanations of the analytics they wanted. Many developments continued through our fieldwork, which indicated how difficult it could be to build technological solutions suitable to the practical issues and needs of Finnish healthcare and social services.

In our discussions with Knowledge Team members, some mentioned that the collaboration became laborious because of the turnover of IT company experts with healthcare knowledge. This may also explain why the collaboration appeared to have grown more cumbersome during our fieldwork. On many occasions, the medical expert pointed out that technological solutions sometimes even hampered the usability of the system. This reinforced our observation of the importance of the Knowledge Team members’ expertise in the DMS development and maintenance. The IT company’s team seemed to be able to do little without those members’ insights, despite drawing on a variety of sources – such as literature reviews and customer experiences – to suggest useful developments.

To bridge the knowledge gap and generate a better tailored DMS, the Knowledge Team members provided extra consultation and materials to the IT company experts, for example, on the terminology used (Fieldnotes, 30 October 2019). During the meetings, the Knowledge Team repeatedly explained why some technological solutions did not match their needs, and thus, requested additional improvements to the DMS. The Knowledge Team repeatedly explained to the IT company experts the logics of healthcare and social services, as well as the restrictions on data views and types of data to be included and excluded in the analytics:

Two medical experts make an assumption about how diagnoses are used. IT company expert says that he’s got a lecture from [name of a person]. ‘I should have the slides somewhere. [...] I can’t say anything for sure before I check them.’ (Fieldnotes, April 17, 2019)

In the development meeting, the medical expert proposes several changes to DMS that seem crucial for the public-sector organisation. Subcontractor’s IT expert thanks for feedback by saying that ‘excellent to hear feedback and suggestions’ as there has been broken telephone effect in getting feedback through IT company. A bit later, he adds that it would be effective to hear feedback before [a new feature] is put into production. In the next meeting, some medical expert’s wishes were fulfilled, and the IT team was ready to demonstrate them, but the medical expert was absent. (Fieldnotes, 18 September 2019; 30 October 2019)

The knowledge boundaries among members of the Knowledge Team were strengthened by organisational hierarchies. The medical expert, who held a significant organisational position, also played a dominant role in all the meetings. The Knowledge Team members were often silent and waited to be called on before commenting unless they had know-how central to the DMS, such as in SHIPs, data(bases) or IT infrastructure. As Halford et al. (Citation2010) pointed out, ‘The exercise of power is closely tied to knowledge’ (p. 445) that is hierarchically structured in organisations. As DMS maintenance, operation and development activities centred on healthcare data and SHIPs knowledge, the dominant position in the meetings was held by the medical expert and the Knowledge Team members whose expertise touched on these types of knowledge. This hierarchy was also visible in terms of whose work the medical expert appraised or was called upon in the meetings. Over time, the experts in data(bases) were also increasingly recognised in the meetings.

The knowledge of social work and services was more broadly underrepresented in both the Knowledge Team and the collaboration. The Knowledge Team members who worked with social services data were not heard much, nor was their knowledge sought to the same extent as those who worked with healthcare data at the meetings. Consequently, the presence of some Knowledge Team members was more anticipated than others by the medical expert and the IT company experts. The medical expert did not hesitate to express his opinions, ideas and feedback to the IT company. Sometimes, the IT company experts directly asked for his feedback:

After having presented the meeting agenda, the IT company’s expert directs the first question to the medical expert and asks whether DMS now works better than before? The medical expert affirms and thanks and expresses the need to finger and twiddle with the system. He also adds that the development is going in a better direction and having more actions is always good. (Fieldnotes, 27 May 2020)

Because of the numerous development ideas, the IT company experts started to ask for a list of priorities. Yet, it became clear that even when developments were crucial, the Knowledge Team faced challenges in setting internal priorities and communicating them to the IT company unless these ideas came from the financial administration. Often, the IT company was offered a general statement from the medical expert that they were interested in all types of analytics that would lead to cost savings. The medical expert encouraged the company to take the initiative in search of such analytics. Yet, obtaining more specific feedback on the developments was often difficult and undermined by some Knowledge Team members’ lack of access to the system:

IT company’s expert expresses a need for the prioritisation of requested developments. The medical expert answers generally that ‘if normal use is laborious, it should be a high priority to fix it.’ He also praises the whole design as developed well and encourages other Knowledge Team members to express their thoughts and user experiences. A[n] HR manager asks for the timetable and the IT company’s expert says that this version is in production. One Knowledge Team member answers that ‘some of us are here only as listeners, we have not been able to test the system yet.’ IT company’s expert expresses his frustration with lack of feedback and suggests a new demonstration. The Knowledge Team members back the idea. HR department middle managers that participate in this meeting are also interested in participating in an additional demonstration to get a better overview of the system and its potential for their use. (Fieldnotes, 29 April 2020)

The developments appeared to focus on aspects associated with cost savings; one of the major interests of the public-sector organisation was to reduce costs through automation and data analytics, and thus, increase the efficiency of public services delivery. The Knowledge Team and medical expert welcomed all possible DMS features and development ideas that assisted with budget estimation and cost-effectiveness. Real-time data analytics were the goal. At the meetings, the medical expert mentioned that one-month-old data analytics were already outdated for the organisation (Fieldnotes, 15 April 2020). Yet, our observations indicated that the DMS was far from reaching this goal despite the resources and efforts invested in it over the past years.

The comparability of information, such as annual expenses across units and municipalities, patient and customer flows, and care paths moved towards the top of the priority list as central to generating cost savings. In autumn 2019, the issue of annual comparisons was classified as small-scale development work. The IT company noted that ‘comparability between years is important to take into account at the end of year’ (Fieldnotes, 30 October 2019). Yet, in the course of our fieldwork, the issue increased in importance, partly because of the municipal decision makers’ demand for more information on how payment shares were counted by the public-sector organisation, specifically, its financial administration. The issue of municipal decision makers’ interests in data regarding expenses was mentioned across observed meetings by different Knowledge Team members. Often, the municipalities’ records on the costs did not match those in the DMS, and they demanded clarification about that (Recurring fieldnotes). In comparison, (middle) managers of the public organisation (e.g., chief physicians, head nurses), as anticipated groups of DMS users, had limited or no possibility of influencing DMS development and implementation.

Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we have enriched the theorisation of the boundary object with Abbott’s ecological approach to professions as a theoretical lens to enhance our understanding of the impact of organisational and professional hierarchies on shaping a DMS for public healthcare and social services in Finland. Our study makes three contributions. First, it enhances the theoretical and empirical understanding of the DMS as a boundary object over time and across boundaries in a public–private partnership. We provide insights into how both organisations acted towards and with three versions of the same DMS (see ), which created conditions for collaboration by serving the interests of several stakeholders. Our study showed how this is possible but involves transcending traditional public–private boundaries (Hogle, Citation2016). For the IT company, the DMS was a new promising data analytics product; although elements of it had originated in the 1990s, the prototype took shape from the mid-2010s. The prototype enabled collaboration based on the intersecting aspirations and interests of the IT company and some public organisations in Finland. Each production version of the DMS was a result of power dynamics materialised into the building of the development version. The production version was systematically updated; it was a rather universal product and portable from context to context, allowing it to be configured separately for each customer organisation.

For the management of public organisations, the DMS was a new governance tool promoting a new model of thinking, intended to be locally adapted to respond to the cost-savings and cost-efficiency needs of the organisation, which go far beyond the traditional tasks of public healthcare and social services. The DMS represented the public-sector organisation management’s aspiration to move towards knowledge-based decision making that informs value-based delivery of public services. Each development cycle provided an opportunity for the public organisation to shape the DMS according to its needs. The production version was a version the organisation could no longer change, but they had some influence over improvement of its functioning. Over time, the public organisation’s unfulfilled aspirations and continuous problems with the functioning of the DMS became more evident and endangered the position of the DMS as a boundary object (see Thomas et al., Citation2008).

As a second contribution, our research extends the previous analysis of power dynamics in the collaboration on boundary objects (Barrett & Oborn, Citation2010; Carlile, Citation2004), as well as research on innovation and design processes (Clausen & Yoshinaka, Citation2007), by covering the organisational and professional hierarchies that materialise in technical systems, influencing the data-driven future built in public–private partnerships. Our study also provides new insights into the operation of knowledge boundaries and the identification of new types of boundaries – access and spatial and communication boundaries. It demonstrates the ways in which power dynamics hindered negotiations and compromise in the search for technological solutions that were central to the delivery and organisation of healthcare and social services.

The identified types of boundaries not only connected but also divided the collaborators and their experts (Kerosuo, Citation2001). When the experts enacted the identified boundaries, they also exercised professional power and drew on avatars (Abbott, Citation1988, Citation2005) in the co-construction of shared understandings around the DMS as a boundary object and hinge. The medical expert acted as a powerful avatar in creating an alliance between the collaborating organisations. Access boundaries showed the exclusive character of collaborative meetings, as well as the creation of technological affordances defining possible and impossible actions and interactions with the DMS as designed for various groups of users (see Costanza-Chock, Citation2020; Hyysalo, Citation2016) by a narrow group of powerful experts. Limited user feedback on developments reinforced organisational hierarchies that empowered certain professional groups over others in their influence over future DMS developments. Spatial and communication boundaries emphasised the importance of transparency in coordinating collaboration and communication as prerequisites for knowledge sharing and production. Knowledge boundaries unmasked the hierarchy of power among different types of expertise recognised and valorised in the collaboration and influenced by organisational and professional hierarchies. The medical profession and financial administration played a central role in setting development priorities but possibly hindered the usability of the DMS for user groups excluded from the collaboration.

Access and knowledge boundaries were intertwined, obscuring the organisational change of moving towards knowledge-based decision making. The change required further developments of the DMS, transformation of structures, and work practices of current healthcare and social service professionals. Additional resources also need to be delegated to the training of current and potential users. Yet, because of power dynamics materialised into the shaping of the DMS, its logic sometimes appeared difficult to grasp, even for Knowledge Team members and especially healthcare and social service professionals, whose work was organised in line with the logic of electronic patient and customer information systems in which they register patient and customer data. Thus, the DMS analytics were not directly applicable and understandable for the ordinary users of the organisation.

As a third contribution, our study relates to the political dimension of the DMS, in which organisational and professional hierarchies, including gender relations, materialise as a product of certain social orders, which have the potential to produce other social and normative orders. The observed collaboration was rooted in the gendered character of professional hierarchies not only between different experts and their professional groups but also between social work and health care. Our study shows how collaboration on the DMS was monopolised by the male-dominated, well-organised professions, such as medicine and the tech industry, in contrast to experts from female-dominated and less organised occupations with a more diverse educational and professional background, such as social workers, nurses, data workers and project managers. This result suggests that the devaluation of women’s work (e.g., Kuhlmann, Citation2006; Wrede, Citation2008) in the public sector continues as female professionals as co-designers and future users of new data analytics products remain less influential.

When some groups of professionals are undervalued or excluded from DMS development work, it is no surprise that they experience usability problems with information systems (e.g., Kaipio et al., Citation2017; Wisner et al., Citation2019). Their exclusion from development work and top-down decisions made on the DMS may also undermine trust in data-driven systems (Henriksen & Bechmann, Citation2020; Steedman et al., Citation2020), which may explain the passivity of some Knowledge Team members during the collaborative meetings. Moreover, earlier research indicated that some of these professional groups negatively experience power dynamics inherent in the implementation of information systems, where technical knowledge is more powerful, for example, than nurses’ work experience, leading to healthcare practitioners’ disappointment with these systems (Nilsson et al., Citation2016). The universalistic design principles and top-down assumptions for current and future users not only ignore their expertise but also undermine their influence on the shaping of technical systems for their needs. In this respect, our study echoes the findings of international scholarship (e.g., Broussard, Citation2018; O’Neil, Citation2016) that highlight the homogeneity of development teams involved in the design of contemporary data-driven technologies. We argue that a better understanding of power dynamics, including gender relations inherent in public–private partnerships and materialised in data-driven technologies, could result in building tools that would better fulfil the promises of data-driven public healthcare and social services in Finland and beyond.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the public organisation and the experts for providing access to the observed meetings and events. We are grateful to our research group members, Prof. Ilpo Helén and Dr Heta Tarkkala, for their comments on the first version of the article. Furthermore, we are grateful for the anonymous reviewers’ constructive feedback, which helped improve the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marta Choroszewicz

Marta Choroszewicz (email: [email protected]) is a postdoctoral researcher in sociology at the Department of Social Sciences, University of Eastern Finland. Her research has broadly investigated social inequalities in the professions. Currently, she is working on the ‘Data-Driven Society in the Making’ project, focussing on the data-driven welfare state, algorithmic decision making, and the mechanism of inequalities related to technology development and deployment.

Marja Alastalo

Marja Alastalo (email: [email protected]) is a university lecturer in sociology at the University of Eastern Finland. Her fields of expertise are science and technology studies and the sociology of quantification. In her empirical studies, she has explored population and migration statistics, indicators, standardisation of statistics in the EU and social research methods. Currently, she is working on the ‘Data-Driven Society in the Making’ research project, focussing on data-driven technologies and practices in public social and health care and their effects on knowledge production and governance.

Notes

1 This article is part of the ‘Data-Driven Society in the Making’ research project (funded by the Academy of Finland 2018–2022, no. 317303) on the development and implementation of data-driven practices in social and healthcare services in Finland.

2 There were two medical experts: an external one who participated irregularly and an internal one that played a central role in the collaboration as he represented the interests of the organisational management.

3 The number and configuration of the team changed from one to two during the fieldwork. For consistency and better anonymity of the research subjects, we refer to the Knowledge Team throughout the article. For the same reason, we do not provide job titles or other personal details when we refer to our fieldwork.

4 The observations resulted in a huge corpus of handwritten fieldnotes taken by each author (7 to 10 A5 notebooks, each with 80 leaves), which are available only in paper form.

5 Four experts were interviewed as part of the project.

References

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press.

- Abbott, A. (1995). Things of boundaries. Social Research, 62(4), 857–882.

- Abbott, A. (2005). Linked ecologies: States and universities as environments for professions. Sociological Theory, 23(3), 245–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2751.2005.00253.x

- Barrett, M., & Oborn, E. (2010). Boundary object use in cross-cultural software development teams. Human Relations, 63(8), 1199–1221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709355657

- Beaulieu, A. (2010). Research note: From co-location to co-presence: Shifts in the use of ethnography for the study of knowledge. Social Studies of Science, 40(3), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312709359219

- Beer, D. (2018). Envisioning the power of data analytics. Information, Communication & Society, 21(3), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1289232

- Bowker, G., & Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. MIT Press.

- Broussard, M. (2018). Artificial unintelligence: How computers misunderstand the world. MIT Press.

- Carlile, P. R. (2004). Transferring, translating, and transforming: An integrative framework for managing knowledge across boundaries. Organization Science, 15(5), 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0094

- Clausen, C., & Yoshinaka, Y. (2007). Staging socio-technical spaces: Translating across boundaries in design. Journal of Design Research, 6(1/2), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1504/JDR.2007.015563

- Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice. Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. The MIT Press.

- Dencik, L., Redden, J., Hintz, A., & Warne, H. (2019). The “golden view”: Data-driven governance in the scoring society. Internet Policy Review, 8(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.2.1413 doi:10.14763/2019.2.1413

- Doolin, B., & McLeod, L. (2012). Sociomateriality and boundary objects in information systems development. European Journal of Information Systems, 21(5), 570–586. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2012.20

- Gieryn, T. F. (1983). Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: Strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. American Sociological Review, 48(6), 781–795. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095325

- Halford, S., Lotherington, A. T., Obstfelder, A., & Dyb, K. (2010). Getting the whole picture? New information and communication technologies in healthcare work and organization. Information, Communication & Society, 13(3), 442–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180903095856

- Helén, I. (2019). Price for a life: An essay on becoming of data-driven market governmentality. Proceedings of the STS Conference Graz 2019, Critical Issues in Science, Technology and Society Studies, 6 - 7 May 2019. https://diglib.tugraz.at/download.php?id=5e29a105b8dfa&location=browse

- Henriksen, A., & Bechmann, A. (2020). Building truths in AI: Making predictive algorithms doable in healthcare. Information, Communication & Society, 23(6), 802–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1751866

- Hogle, L. F. (2016). Data-intensive resourcing in healthcare. BioSocieties, 11(3), 372–393. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-016-0004-5

- Hyysalo, S. (2016). Sosiologinen materia-toimijaverkostoteoreettisen tutkimustarinan ohennus. Sosiologia, 53(3), 275–291.

- Johnson, D. G., & Verdicchio, M. (2017). Reframing AI discourse. Minds and Machines, 27(4), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-017-9417-6 doi:10.1007/s11023-017-9417-6

- Kaipio, J., Lääveri, T., Hyppönen, H., Vainiomäki, S., Reponen, J., Kushniruk, A., & Vänskä, J. (2017). Usability problems do not heal by themselves: National survey on physicians’ experiences with EHRs in Finland. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 97, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.010

- Kerosuo, H. (2001). Boundary encounters as a place for learning and development at work. Outlines. Critical Social Studies, 3(1), 53–65. https://tidsskrift.dk/outlines/article/view/5128

- Keshet, Y., Ben-Arye, E., & Schiff, E. (2013). The use of boundary objects to enhance interprofessional collaboration: Integrating complementary medicine in a hospital setting. Sociology of Health Illness, 35(5), 666–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01520.x

- Kitchin, R. (2017). Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154087

- Kivinen, T., & Lammintakanen, J. (2013). The success of a management information system in health care - A case study from Finland. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 82(2), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.05.007

- Kuhlmann, E. (2006). Modernising health care. Reinventing professions, the state and the public. The Policy Press.

- Leskelä, R.-L., Haavisto, I., Jääskeläinen, A., Helander, N., Sillanpää, V., Laaksonen, V., Ranta, T., & Torkki, P. (2019). Tietojohtaminen ja sen kehittäminen: tietojohtamisen arvointimalli ja suosituksia maakuntavalmistelun pohjalta. Valtioneuvoston selvitys- ja tutkimustoiminnan julkaisusarja 42. Valtioneuvoston kanslia.

- Levina, N., & Vaast, E. (2005). The emergence of boundary spanning competence in practice: Implications for implementation and use of information systems. MIS Quarterly, 29(2), 335–363. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148682

- Nilsson, L., Eriksén, S., & Borg, C. (2016). The influence of social challenges when implementing information systems in a Swedish health-care organization. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(6), 789–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12383

- O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown.

- Pedersen, S., Dorland, J., & Clausen, C. (2020). Staging: From theory to action. In C. Clausen, D. Vinck, S. Pedersen, & J. Dorland (Eds.), Staging collaborative design and innovation: An action-oriented participatory approach (pp. 20–36). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Pritchard, K. (2011). From “being there” to “being […] where”: Relocating ethnography. Qualitative Research in Organisations and Management: An International Journal, 6(3), 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465641111188402

- Ryan, G. W., & Russell, H. B. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569

- Seale, J., Nind, M., Tilley, L., & Chapman, R. (2015). Negotiating a third space for participatory research with people with learning disabilities: An examination of boundaries and spatial practices. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 28(4), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2015.1081558

- Seaver, N. (2017). Algorithms as culture: Some tactics for the ethnography of algorithmic systems. Big Data & Society, 4(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717738104

- SITRA. (2016). Sote-tiedosta tekoihin. Palvelupaketit raportoinnin työkaluna - ja mitä niillä voidaan seuraavaksi tehdä. https://www.sitra.fi/julkaisut/sote-tiedosta-tekoihin/

- Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö. (2020). Sote-tietopaketit – raportointityökalu kunnille. https://stm.fi/sote-tietopaketit

- Star, S. L. (2010). This is not a boundary object: Reflections on the origins of a concept. Science. Technology and Human Values, 35(5), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624 doi:10.1177/0162243910377624

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, “translations” and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

- Steedman, R., Kennedy, H., & Jones, R. (2020). Complex ecologies of trust in data practices and data-driven systems. Information, Communication and Society, 23(6), 817–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1748090 doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1748090

- Susskind, R. E., & Susskind, D. (2015). The future of the professions: How technology will transform the work of human experts. Oxford University Press.

- Thomas, R., Sargent, L., & Hardy, C. (2008). Power and participation in the production of boundary objects (Working paper series). Cardiff Business School. https://www.coursehero.com/file/25942210/Thomas-et-al-power-and-participation-in-the-production-of-boundary-objectsdoc/

- Waring, J., & Latif, A. (2017). Of shepherds, sheep and sheepdogs? Governing the adherent self through complementary and competing “pastorates”. Sociology, 52(5), 1069–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517690680

- Wisner, K., Lyndon, A., & Chesla, C. A. (2019). The electronic health record’s impact on nurses’ cognitive work: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 94, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.03.003

- Wrede, S. (2008). Unpacking gendered professional power in the welfare state. Equal Opportunities International, 27(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610150810844910