ABSTRACT

The Facebook Ad Library promises to improve transparency and accountability in online advertising by rendering personalised campaigns visible to the public. This article investigates whether and how journalists have made use of this tool in their reporting. Our content analysis of print journalism reveals several different use cases, from high-level reporting on political campaigns to uncovering specific wrongdoings such as disinformation, hate speech, and astroturfing. However, our interviews with journalists who use the Ad Library show that they remain highly critical of this tool and its manifold limitations. We argue that these findings offer empirical grounding for the public regulation of ad archives, since they underscore both the public interest in advertising disclosures as well as the growing reliance of journalists on voluntary and incomplete access frameworks controlled by the very platforms they aim to scrutinise.

I. Introduction

Since 2018, major advertising platforms have started to publish ad archives: public databases documenting advertisements sold on their services. These reforms respond to mounting concerns about the lack of transparency and accountability in this industry. Several governments are now poised to regulate ad archives by law, as in Canada’s Elections Modernization Act and the EU’s proposed Digital Services Act. Lively academic debate has ensued as to the merits of ad archives, including a growing body of evidence pointing to the shortcomings of existing self-regulatory efforts.

Now, over three years since the launch of the Facebook Ad Library, the earliest and most expansive platform ad archive, this article offers a first attempt to map its impact in practice. It asks not what usage this tool could enable but rather what usage it has enabled. In particular, this paper examines journalists as a key user group, central to public accountability processes. It inquires whether and how journalists have made use of Facebook Ad Library in their reporting, and whether these practices contribute to accountability in online advertising.

This paper proceeds as follows: Section II describes the Ad Library and its features, the policy concerns that drove its creation, and its relevance to watchdog journalism. Section III provides a content analysis of ad archive journalism: through an inductive, quantitative pilot study, we generate a typology of different journalistic usages of the Ad Library. On this basis we perform a quantitative analysis of print journalism sampled from the LexisNexis database in order to appraise the composition and scale of this phenomenon. Section III then describes interviews with relevant journalists, which review their experiences with and attitudes towards the Ad Library. In light of these findings, Section IV assesses the Ad Library’s contribution to transparency and accountability in platform governance.

II. Background

The ad Library and its features

The Ad Library documents a selection of ads that appeared on Facebook.Footnote1 It lists the ad content as well as metadata such as buyer name, amount spent, and demographic reach by region, age and gender (Facebook, Citation2021a). The Ad Library is available through a browser interface as well as an automated programming interface (API). Currently, the Ad Library focuses primarily on ‘ads about social issues, elections and politics’ (Facebook, Citation2021a). Advertisers seeking to publish ads in this category must apply for prior authorisation, and Facebook enforces this rule through human and automated monitoring. Facebook maintains lists of political ‘issues’ for several jurisdictions in order to operationalise their classifications (Facebook, Citation2021b). Other (commercial) ads receive a lower level of transparency: they are only visible as long as they are active on the platform, with restricted search functionalities and less metadata (Facebook, Citation2021a).

The Ad Library has been criticised extensively for its faulty design and implementation (Rieke & Bogen, Citation2018; Leerssen et al., Citation2019; Mozilla, Citation2019; Edelson et al., Citation2019; Edelson et al., Citation2020; Silva et al., Citation2020; Hounsel et al., Citation2019; Grygiel & Sager Citation2020; Kreiss & Barrett, Citation2020). To name some of the most significant shortcomings: the Ad Library’s demographic data does not disclose the targeting mechanisms involved; its audience and spend data are insufficiently granular; the browser interface and API are restrictive and unreliable; the focus on political and issue ads is restrictive, and definitions are ambiguous and subjective; the identification of these ads in practice has proven inconsistent, leading to both false positives and false negatives; and data are not standardised across different platforms. Analysis by Edelson et al. (Citation2020) also showed that ads had been retroactively removed from the Ad Library, calling into question the reliability of its archival function.

Background and rationale

Ad archives emerged as a response to mounting criticism of online advertising following the US presidential election and UK Brexit campaign of 2016. Much of this criticism is closely connected to the personalised distribution of microtargeted ads, and the resulting lack of a public record. A personalised ad is in principle only visible to the specific audience members it targets and leaves no trace after its distribution. In the legacy media, by contrast, ads are public in the sense that they are equally accessible to all audience members, in addition to commonly being preserved by institutions such as newspaper and television archives (Birkner et al., Citation2018). The non-public and ephemeral nature of online advertising makes it more akin to direct marketing via email or telephone, which has raised comparable policy concerns around transparency and accountability (e.g., Miller, Citation2009).

The policy concerns related to transparency of online advertising are several. First, political microtargeting might undermine electoral accountability, by allowing campaigners to signal different campaign promises to different constituencies (e.g., Dobber et al., Citation2019). This ‘fragmentation of the marketplace of ideas’ (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., Citation2018) is also seen to undermine the capacity for public deliberation, since political actors can no longer observe and respond to the microtargeted ads of their rivals (Gorton, Citation2016). As a result, the capacity for ‘dark advertising’ may also engender false and inflammatory messaging, by foreclosing the ability of rival campaigners, media actors and other third parties to rebut, critique or otherwise sanction such transgressions. Similarly, dark ads provide cover for ‘dark money’ advertising funded by special interests and foreign governments (Kim et al., Citation2018). A related concern is that targeting leads to algorithmic discrimination, which may exclude people from valuable content, and, conversely, overexpose vulnerable groups to harmful or manipulative content (Bodo et al., Citation2017; Dobber et al., Citation2019; Ali et al., Citation2019). Here, too, personalisation may frustrate the ability to detect and address wrongdoings. Although empirical evidence exists for many of the above claims (Kim et al., Citation2018; Ali et al., Citation2019), a lively debate persists about the overall significance of these microtargeting concerns relative to other policy concerns in media governance (Heawood, Citation2018; Benkler et al., Citation2018).

Seen in this light, the Facebook Ad Library represents a potentially significant shift in the affordances of online microtargeting: by creating a public record of personalised advertising messages, it may help to diagnose and address many the above harms. However, the governance literature on transparency and accountability warns that such assumptions about the salutary effects of information disclosure should be approached critically (Flyverbom, Citation2019), and that much depends on whether watchdogs organisations, particularly the media, actually use the available information for accountability purposes.

The ad Library as a tool for watchdog journalism

The governance literature emphasises that transparency is not a guarantee for accountability, but merely a precondition (e.g., Meijer, Citation2014). The accountability effects of transparency are not self-executing, but depend on relevant stakeholders to actually use the available information and attach consequences to it (Bovens, Citation2007). In practice, however, disclosures may lack a ‘critical audience’ with the capacity and interest to fulfil this role (Kemper & Kolkman, Citation2019). In the context of online campaigning, Katherine Dommett has therefore warned that ‘it is not clear whether citizens are aware of, or could easily discover the existence of, [ad] archives’ (Dommett, Citation2020).

Scholarship routinely asserts the governance benefits of public transparency, but these are almost never tested empirically (Safarov et al., Citation2017). What little evidence we do have, mostly from the open government context, indicates that most public transparency resources are underused, and almost never consulted by individual citizens (Meijer, Citation2014; Quarati & De Martino, Citation2019). This literature emphasises the importance of mediation by specialised stakeholders who process open data and recirculate its insights to general audiences (Meijer, Citation2014; Fung, Citation2013; Lourenco, Citation2016). Journalists in particular are highlighted as key users of open data and as agents of public accountability (Lourenco, Citation2016; Fung, Citation2013; Meijer, Citation2014). Research by Kate Dommett into the UK media’s digital campaigning coverage has already shown that platform disclosure policies, including ad archives, can both enable and constrain reporters on topics of public interest (Dommett, Citation2021). This paper builds on such findings by focusing the affordances of one specific tool, the Facebook Ad Library, for reporters across different (regional and topical) contexts.

What role do journalists play in public accountability? Formally, journalists have no power to impose sanctions on other stakeholders such as platforms or advertisers. Instead, their reporting can act as a catalyst for other forms of accountability, such as electoral, legal or social accountability (Norris, Citation2014; Bovens, Citation2007). Norris (Citation2014) observes that watchdog journalism can contribute to accountability in two ways: a more concrete primary function of revealing specific instances of malfeasance, and a more diffuse secondary function of informing public deliberation and democratic self-governance. The Ad Library could conceivably contribute to both functions since, as discussed, the opacity of online advertising is associated with both individual wrongdoings and with the barriers to public deliberation. Journalism about the personalised targeting of ads could also constitute what Nicholas Diakopoulous has termed ‘algorithmic accountability reporting’ which ‘seeks to articulate the power structures, biases, and influences that computational artifacts play in society’ (Diakopoulos Citation2015).

To study watchdog journalism empirically, Norris (Citation2014) outlines three areas of inquiry: ‘(1) whether journalists accept their role as watchdogs, (2) whether they act as watchdogs through their coverage in practice, and (3) whether this activity serves as an effective accountability mechanism by mobilising voters, policymakers or other democratic forces’. In other words: attitudes, coverage, and impact. We explore attitudes and coverage through a combination of content analysis and interviews. Taken together, these also provide starting points for the assessment of impact.

III. Content analysis

Methods

Given the exploratory nature of this research, we first performed an inductive, qualitative pilot study in order to generate a typology of journalistic references to the Ad Library. This provided the basis for a large-scale quantitative analysis of articles via the LexisNexis database. Together, these analyses illustrate the general substance, scale and geographic distribution of Ad Library journalism.

Pilot study

Our pilot study took place in May 2020. We studied articles referencing the Facebook Ad Library through Google Search and Google News, based on keyword searches for < ‘Facebook’ AND ‘Ad Library’ OR ‘Ad Archive’>. News articles containing concrete references to Ad Library data were selected for analysis. In total we collected 38 such articles. Through qualitative, inductive analysis, we devised a typology of different forms of usage (Mayring, Citation2000). In particular, our analysis focused on the types of data involved, whether any wrongdoing was asserted, and the norms or standards invoked. This typology was operationalised and refined iteratively into a protocol for large scale quantitative analysis, which we discuss below.

Content analysis protocol

From our pilot study it immediately became clear that many journalistic references to the Ad Library consisted of describing the Ad Library as a phenomenon, rather than actually using the data it offers. Announcements and updates to the Ad Library made headlines regularly as it was updated, expanded, and gradually rolled out across the globe (e.g., ‘Facebook Is Taking Steps to Safeguard Canada’s Oct. 21 Federal Election’). These articles, which we term ‘metacoverage’, were filtered out from further analysis since they do not involve any usage of the Ad Library as a tool for transparency (‘Non-metacoverage’). More specifically, we filtered out articles lacking references to actual data from the Ad Library such as concrete spending figures or advertising messages, as well as articles that reference Ad Library data solely to illustrate its affordances.

For articles that actually use the Ad Library, we distinguished between two types following Norris (Citation2014) aforementioned distinction between the primary and secondary functions of watchdog journalism: calling attention to wrongdoing, and disseminating information in service of public deliberation. We operationalised this distinction by coding whether the article purported to expose any potential wrongdoing related to Facebook advertising cited from the Ad Library, based on criticism supplied by the author or a quoted source (‘Wrongdoing reported’). Wrongdoing in this account can include potentially unlawful activity but also anything described as harmful or unethical. Such allegations must be made explicitly in the article by either the author or a quoted source. For instance, reporting on wrongdoing includes articles involving allegations of false or misleading advertisements, voter suppression, foreign interference or violations of campaign finance laws. Ad Library usage without any wrongdoing, our pilot study showed, typically focused on spending trends and messaging strategies for political advertising.

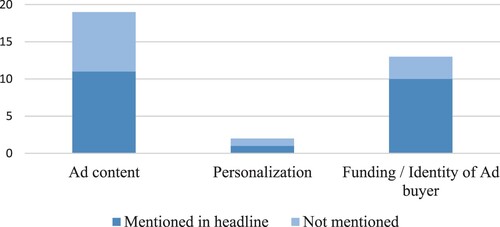

We also coded for three specific subcategories of wrongdoing identified during the pilot study: First, wrongdoing related to advertising content, such as misleading or hateful content (‘Wrongdoing category: Content of the advertisement’). Second, wrongdoing related to personalisation practices, such as discriminatory, manipulative or exclusionary targeting (‘Wrongdoing category: Personalisation’). Third, wrongdoing related to the identity of the ad buyer and the origin of their funds, such as deceptive or clandestine ad funding schemes (e.g., ‘astroturfing’), the involvement of foreign entities, and the violation of election spending restrictions (‘Wrongdoing category: Identity of the ad buyer & origin of funds’). As a proxy for the prominence of wrongdoing within the overall article, we code for each category whether the allegation is described solely in the body text or also in the article headline. In addition, we code whether the wrongdoing is described as a potential violation of applicable Laws (‘Violation of Law’) and Terms of Service (‘Violation of Terms of Service’), in order to clarify the norms and sanctions at stake: whether it concerns a more ‘soft’ form of accountability based on reputation and publicity, or a ‘hard’ form of accountability grounded in binding norms and sanctions. We also code whether the ad in question is political or non-political (‘Political Ad’), which we operationalise as any ad without an apparent commercial purpose, as well as any ad that is described in the article as having been classified as ‘political’ by Facebook.

Sample

Our sample was collected from the LexisNexis news archive of print media. We performed keyword searches in the publication categories ‘Newspapers’ and ‘Magazines’ and for the regions United Kingdom, United States, Germany and the Netherlands. The United Kingdom and the United States were selected due the prevalence of political microtargeting in these countries, as well as the fact that the Ad Library was launched in these countries before any other. Germany and the Netherlands were selected as additional countries with comparable levels of socioeconomic development yet with relatively smaller-scale political microtargeting industries, as well as due to language considerations.

Our sampling used the keywords <‘Facebook’ AND ‘ad library’ OR ‘ad archive’>. The keywords ‘ad library’ and ‘ad archive’ were combined because nomenclature is not consistent across outlets; the New York Times, for instance, tends to use ‘archive’, and the Washington Post ‘Library’. This likely results from Facebook’s own inconsistency on the topic: the company initially branded the tool as an ‘Archive’, but later rebranded to ‘Library’ (Grygiel & Sager, Citation2020). In Germany and the Netherlands, we also included the keywords ‘Advertentiebibliotheek’ and ‘Werbebibliothek’, respectively, which are local names for the Ad Library. This approach has certain limitations in detecting Ad Library-related journalism that departs from these referencing conventions, which we discuss in Section V. We searched for articles published between May 2018 (when the Ad Library first became operational) and August 2020. This returned a total of 203 articles, excluding 5 duplicates.

Inter-coder reliability

A sample of 58 articles (28% of all articles) was double coded by two coders to calculate intercoder reliability (Krippendorff’s alpha). below lists the results. We were not able to calculate Krippendorff’s alpha for the variables ‘Wrongdoing category: Personalisation’ and ‘Wrongdoing norm: Violation of Law’ since there were not enough cases where these categories applied. A Krippendorff’s alpha of .80 is often seen as the norm of strong reliability, and the cut-off point is .67 (Riffe et al., Citation2014).

Table 1 – Inter-coder reliability scores

Findings

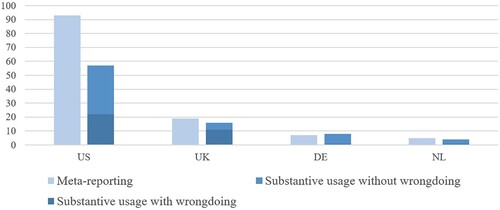

Our results show that the Facebook Ad Library was referenced in at least 203 print newspaper and magazine articles in the selected countries. The bulk was published in the United States and the United Kingdom, with 150 and 29 articles respectively, compared to Germany’s 15 and the Netherlands’ 9. The list of publishers is likewise dominated by US outlets, with only one UK outlet breaking the top 5: AdWeek (33 articles), the New York Times (31 articles), CE Notificias Financeras (25 articles), the Washington Post (21 articles), and The Guardian (17 articles). Together, they account for 62% of our findings, with the remainder being supplied by 48 other outlets. It is worth noting that many of the non-US publications in our sample were in fact reporting about US advertisements, particularly in the United Kingdom and particularly for stories that actually identified potential wrongdoing (discussed below).

In terms of substance, 118 out of 203 articles in our sample, or 58%, consist of metacoverage that merely describes the tool rather than actually using the data on offer (see ).

As for the articles that do use Ad Library data, shows that 50 out of 85 do not allege any particular wrongdoing based on this data (see ). As discussed, these articles typically focus on campaign coverage, for instance reporting on aggregate spending trends (e.g., ‘Biden Pours Millions Into Facebook Ads, Blowing Past Trump’s Record’) or messaging (e.g., ‘Trump Campaign Facebook Ad Strategy: Paint Biden As A Socialist’). Although the majority appears to focus on election and referendum campaigns, other issues are also reported on occasionally. To take one notable example, the Washington Post cited the Ad Library to report on the FBI’s use of Facebook ads to recruit Russian informants. Ad Library usage is not always central to the article’s topic but can also be used more incidentally as context for other stories.

As for articles about possible wrongdoing, shows that 19 counts related to the content of the ad, 13 to the identity of the ad buyer, and only 2 to personalisation. Here it bears repeating that the Ad Library provides only limited information on personalisation techniques. Just under two thirds of these articles (22/34) mention these issues in the headline as well as in the body text (see ).

A possible violation of the law was alleged in 4 cases. In 9 cases, the ads were also described as violating Facebook’s Terms of Service.

Content-based wrongdoings mostly involved allegedly false or misleading statements. Accusations of hate speech were also found, for instance regarding Trump advertisements involving alleged Nazi symbols. Wrongdoings related to the identity of the ad buyer typically focused on the misleading use of astroturf groups and the listing fake or misleading names in relevant disclosures to Facebook (e.g., ‘In Virginia House Race, Anonymous Attack Ads Pop Up on Facebook’).

Only two articles in our sample involved commercial ads: one about false ads for solar panels and another about misleading ads for HIV medicine. Here it bears repeating that the Ad Library’s functionalities for commercial ads are restricted substantially compared to political ads.

IV. Interviews

Building on the above content analysis, we also interviewed journalists to discuss their experiences in using the Ad Library. Recalling Norris (Citation2014) three empirical aspects of watchdog journalism—attitudes, coverage, and impact—the above content analysis demonstrates coverage, and these interviews allow us to explore attitudes. Extensive survey research has already examined the self-conception of journalists as public watchdogs in a general sense (e.g., Weaver et al., Citation2007), but no research has yet focused on their perception of the Ad Library as a means to this end. Our aim here is not to develop claims that generalise across journalism writ large, but rather, through qualitative, in-depth interviews (McCracken, Citation1998) to unpack the particular motives and experiences of journalists who have used the Ad Library.

Methods

We approached 16 journalists with experience using the Ad Library, and 12 of them agreed to be interviewed. Participants were selected based on published work identified in the content analysis pilot study, combined with snowball sampling. Our aim in sampling was to obtain a diversity of perspectives, in terms of participants’ location, venue, and beat. We prioritised journalists with multiple publications based on the Ad Library, but also included several with only one or two relevant publications. Due to language considerations, our selection was limited to journalists working in English or Dutch. Interviews were conducted in the period September-November 2020 via Zoom videoconferences. provides an overview of participants and their titles and affiliations at the time of our interviews, which we publish with their permission. In some cases, relevant work was published on a freelance basis, or with a former employer; these outlets are listed in brackets.

Table 2 - Overview of interviewees

The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format, with an interview guide based on the following questions:

Use cases: How, if at all, has the Ad Library appeared in your work?

Research processes: Could you describe your process in using the Ad Library?

Attitudes: What is your opinion on the usefulness of the Ad Library as a tool for journalists?

Outlook: Do you intend to use the Ad Library in future?

We discuss our findings in the corresponding order.

Findings

Use cases

The use cases mentioned by participants mirrored the results of our content analysis: participants were able to make good use of spending and content data, but lamented the lack of targeting data. In addition, participants also highlighted the role of the Ad Library as a means to evaluate the enforcement of Facebook’s own policies, such as ad pricing and content rules.

Reporting on ad spending and funding sources: A majority of the journalists we spoke to (7/12) highlighted the Ad Library’s insights into ad spending, for instance as a means to ‘follow the money’ (Coen van de Ven) or ‘to see who’s been spending what and how’ (Mark Scott). Madelyn Webb, a disinformation researcher, used the Ad Library because ‘there’s interesting stories to be told about who is spending money on particular misleading narratives.’ Rik Wassens recounted that his editors also emphasised the significance of spending in their headlines: ‘The amount of money. That is absolutely the most newsworthy. I don’t write the headlines myself but they do show you how the institutions view things, and there you go: ‘Socialist Party sends €50,000.’

Participants also highlighted the role of the Ad Library in detecting new actors and sources of funding. According to Jeremy B. Merrill, ‘[w]hat’s interesting about these ads from the Ad Library–it’s not often that the ad ran, it’s who this group is that now exists. It’s some group that you’ve never heard of before, that’s running ads. […] The story then is that there’s this group, and that they’re spending 10,000 dollars or whatever.’ Examples from participants include anti-union astroturfing groups, lobbying funded by energy and fossil fuel companies, as well as propaganda from Chinese and Turkish state media related to the oppression of Uighurs and Kurds.

A specific use case for spending data highlighted by Jeremy B. Merrill was researching Facebook’s differential pricing policies: by comparing spend and view data per campaign, he was able to show that the Biden campaign had been charged higher rates on average than the Trump campaign. Mark Scott described how the Ad Library helped to uncover unlawful campaign finance practices in the United Kingdom: ‘The dollar or euro spend in specific races has been interesting because it provides a clear example, for instance in the UK 2019 election, of people breaking the law: candidates using money in their constituency that they weren’t supposed to.’

Journalists nonetheless faced important obstacles in researching ad spending through the Ad Library. The data was insufficiently granular, since it is disclosed in general ranges rather than precise amounts. Participants also reported difficulties in overseeing spending by entities with multiple Facebook pages and accounts. Furthermore, the names provided under ‘paid for’ disclosures were often imprecise, referring to non-existent organisations or proxy organisations. In these instances, the Ad Library merely served a starting point for investigation, and other forms of research were necessary to uncover, if possible, the true origin of funds. In the words of Nick Garber, ‘I had to do some digging to understand that the group that was named as the sponsor had ties to a much larger parent organisation.’ Likewise, Jeremy B. Merrill recounted: ‘I had to do a whole bunch of shoe-leather reporting to figure it out’.

Reporting on targeting practices: Almost all participants expressed interest in targeting practices and complained that the Ad Library failed to offer meaningful information about this issue (8/12). The Ad Library offers highly generic reach data and no concrete information as to the targeting mechanisms involved. Only in exceptional cases could this reach data be used to infer targeting strategies, according to Coen van de Ven:

Where does it deviate? With all the political party data you tend to see a certain distribution in terms of age, location, and it’s almost never surprising. And so if there’s an exception, that’s when I start paying attention. That’s when I think: How can that be? If I see a 100% female reach, then I know: this wasn’t targeted at men. That’s an assumption I’m allowed to make. […] So, I’m happy that it exists, it’s better than nothing. But I’m still missing a lot. It’s not the transparency we as journalists or other researchers were hoping for.

Reporting on ad contents and content policy enforcement: Other use cases related to the content of advertisements, and, relatedly, how Facebook enforces their content policies. Media watchdog researchers used the Ad Library regularly to search for harmful content. Kayla Gogarty from Media Mattters described her routine as follows: ‘I basically have sets of pages that I would follow almost on a daily basis, particularly to look for repeat offenders—accounts that we know will frequently post misinformation in their ads.’ Two participants used to the Ad Library to detect manipulated media, by cross-referencing ad content with original sources. Gogarty also recounted assisting other colleagues at Media Matters in using the Ad Library, for instance helping their LGBTQ program team to trace the spread of anti-trans Facebook advertising.

Related to the above, several journalists (4/12) described how they used the Ad Library to detect gaps and inconsistencies in Facebook’s Terms enforcement. As Madelyn Web of First Draft put it: ‘Every time they say they’re gonna take something down, we can find examples of it. […] When they announced the QAnon takedown, I was like ‘hmm, okay’, so I went to the Ad Library’. Kayla Gogarty: ‘If there’s a new Facebook policy that’s coming out, I’ll go and check: are these ads not following this policy, might they have slipped through the cracks?’ Ryan Mac considered holding Facebook accountable his primary use case for the Ad Library: ‘What I do is corporate accountability. It’s not necessarily holding up a press release about what the company’s doing, it’s: here’s what the company says it’s going to do, and here’s what it’s doing wrong.’ For instance, he used the Ad Library to show that Facebook had enforced its rules on clickbait inconsistently, allowing Trump to run numerous ads that violated the company’s policies. ‘It’s the Facebook policy, and so you want it to be applied equally across something as consequential as the US election. If it’s not, that’s giving a candidate by definition an unfair advantage. And that’s a story.’

Research processes

We discussed how journalists discover relevant information in the Ad Library. Participants engaged in both proactive research consisting of browsing or analysing Ad Library data, as well as reactive research prompted by third-party tips. One telling example comes from Nick Garber, who was directed to the Ad Library by a labour union representative he interviewed, ultimately leading him to discover an anti-union influence network. New policy announcements from Facebook were another important prompt to check the Ad Library. Ryan Mac, one of the most prolific reporters of Ad Library stories in our sample, put it as follows: ‘I’m sure there’s a reporter out there who checks the Ad Library every day, but for most journalists it’s a sporadic thing that they’ll check now and then when they have a tip.’ Others made a habit of searching the Ad Library more regularly. Indeed, two of the journalists we spoke to, Madelyn Webb and Matt Novak, did claim to check the Ad Library every morning, at least during elections.

Most participants lacked the expertise to make use of the API themselves (10/12), and either stuck to the browser interface (6/12) or enlisted the help of specialists to gather data through the API (4/12). Two journalists in our sample preferred to work with data collected independently through volunteers with browser plugins, which automatically collect data about the advertisements shown to individual participants as they browse the web, rather than relying solely on Ad Library data. They used the Ad Library mostly to enrich and corroborate their independent observations. For instance, Jeremy Merrill described his involvement in the NYU Ad Observatory, which combines data from browser plugins and the Ad Library with a view to supporting journalists in reporting on online political advertising.

Attitudes towards the Ad Library

We discussed how participants perceived the usefulness of the Ad Library as a tool for journalists. The responses indicated a love/hate relationship: the Ad Library was considered an improvement over the default opacity of political microtargeting, but most participants remained sharply critical of its flaws and shortcomings. Only two participants had no particular criticisms of the tool, and these were both once-off users who did not use the Ad Library regularly.

The perceived advantages of the Ad Library related to the use cases it enabled, described above, such as corporate accountability and the combating of disinformation. Two participants articulated a more general desire to bring visibility to personalised messaging and exposing it to public deliberation and scrutiny. Eric van den Berg remarked:

What always surprises me is that a lot of things happen which reach a very large audience, but still seem to enjoy a kind of relative invisibility. Journalists don’t write about it, and as a result the standards for what constitutes normal behaviour seem to be very different. I think the things that the VVD [The Netherlands’ incumbent political party] gets up to on Facebook would lead to shocked reactions in Parliament.

Against these benefits, participants offered many criticisms of the Ad Library. Most common was the lack of targeting information, discussed previously. The lack of granularity in both reach and spending was also a recurring theme. Mark Scott, who reported on elections in both the United States and Europe, highlighted that European versions of the Ad Library were even less detailed than the US version. Participants also criticised the reliability and user-friendliness of both the API and the browser tool. Tracking overall campaign spending was difficult since platforms presented spending data per Page, whereas campaigns often operated multiple Pages. Two participants also expressed concerns that the data risked misleading non-expert journalists, who might for instance mistake reach data for targeting data, or Page spending for total campaign spending. Another drawback journalists mentioned was that Ad Library research was time-consuming, and difficult to accommodate in their busy schedules.

Outlook

Most participants were interested in continuing to use the Ad Library, though few had concrete ideas or plans. Participants from the Netherlands already intended to continue using the tools for the upcoming elections of Spring 2021 and predicted that attention for the tool would increase as Facebook advertising grew in scale and significance for domestic political campaigns. Participants also described how they were helping to make the Ad Library more visible and accessible amongst their peers, for instance by organising public webinars for investigative journalists, internal seminars for newspaper colleagues, Twitter bots repurposing Ad Library data, and the aforementioned NYU Ad Observatory.

V. Discussion

Our paper confirms that the Facebook Ad Library has supported watchdog journalism. We find evidence for both the primary watchdog function of calling attention to wrongdoing by powerful actors (in this case: Facebook and its advertisers) as well as the secondary watchdog function of disseminating general information about public affairs (in this case: microtargeted political campaigns). As regards the primary watchdog function, these stories tend to revolve around calling attention to influence networks and astroturf operations, as well as monitoring ad content for hate speech and disinformation. Another recurring issue was the consistency and fairness of platform policy enforcement, especially their content policies but also other aspects such differential pricing between campaigns. Turning to the secondary watchdog function, these stories tended to focus on campaign reporting, in particular on spending trends and to a lesser extent messaging and targeting strategies. In addition to these recurring themes, the Ad Library also featured in a range of more unexpected and niche topics, from FBI recruitment ads to scams targeting elderly Trump voters.

We observe a notable geographic discrepancy in Ad Library usage: it is most prevalent in the US, less so in the United Kingdom and less still in Germany and the Netherlands. It goes beyond the scope of this paper to offer an exhaustive explanation for these discrepancies, but the most readily apparent factor seems to be that political microtargeting simply takes place on a far larger scale in the United States (Dobber et al., Citation2019). In the Netherlands and Germany, by contrast, political advertising budgets are only a fraction of those in the US, and it stands to reason that the issue does not receive the same level of attention. Of course, these circumstances may change. Interview participants from the Netherlands predicted that online advertising would increase in future elections, as would usage of the Ad Library.

We found more metacoverage about the Ad Library than actual usage. Arguably, this suggests that this tool has been successful for Facebook at least as a PR measure, generating coverage about their efforts to create transparency, without necessarily receiving scrutiny of the practices at issue. Still, we do find evidence that such scrutiny takes place at least in some cases, leaving it up for discussion whether the public interest value of this watchdog journalism justifies the accolades that we find Facebook to have received.

As for attitudes, our interviewees’ opinions on the Ad Library might be summarised as ‘better than nothing’. They perceived a strong public interest in public advertising transparency, and considered the Ad Library a significant improvement over the status quo ante of total opacity. However, most participants remained sharply critical of the numerous shortcomings in the Ad Library’s present implementation, including but certainly not limited to the lack of targeting data and the lack of user-friendliness. Many of the most specialised journalists still preferred to work with alternative data collection methods such as data scraping via browser plugins. But Facebook has recently started cracking down on these independent collection methods (e.g., Sellars, Citation2020), leaving journalists all the more reliant on the inferior offerings of the Ad Library.

Impact: from publicity to accountability?

Publicity does not guarantee accountability. The power of the press over platforms and their advertisers is indirect and contingent on its (perceived) ability to mobilise an effective response from other stakeholders, such as end users, voters, governments, or regulators. Given that dominant platforms such as Facebook are able to act with relative impunity towards many of these stakeholders (Moore & Tambini, Citation2018), watchdog journalism might too be ‘disconnected from power’– as transparency measures often are (Ananny & Crawford, Citation2018). How, and when, might it make a difference?

The strongest evidence of accountability we find in cases where the advertising is alleged to violate formal rules, such as platform Terms of Service and/or applicable laws. These cases typically lead to removal of the ads in question and could also trigger legal action. The causal chain from information disclosure to repercussion is relatively short and accountability thus relatively plausible and tangible.

In other cases, our findings are at most suggestive of softer, more diffuse forms of political accountability. Straightforward campaign reporting that does not involve any particular wrongdoing could still conceivably contribute to electoral accountability of campaigners towards voters, by exposing targeted campaigns to a broader public and thus mitigating the ‘fragmentation’ of political campaigning associated with political microtargeting (Dobber et al., Citation2019). This is especially likely in cases where reporters aim to highlight inconsistencies in messaging towards different constituencies, such as Matt Novak’s article at GizModo highlighting that ‘Trump’s New Facebook Ads Claim He’s Peacenik Who Also Loves Assassinations’. Other articles do not address consistency as explicitly but could still have some plausible constraining or ‘defragmenting’ effects. For instance, reports observing that ‘Trump’s deluge of Facebook ads have a curious absence: coronavirus’ can be conceived of as catalysing a more informed public discourse about the priorities of this campaign, a form of public accountability which might feed into any number of more proximate accountability processes. In addition to electoral accountability towards voters, this campaign reporting could conceivably catalyse other forms of social and political accountability (Bovens, Citation2007), for instance by spurring legislative or regulatory reforms. As an empirical matter, more detailed process tracing would be needed to demonstrate any such effects conclusively.

It is worth noting that both disinformation and astroturfing, two of the most common forms of wrongdoing identified through the Ad Library, are not always prohibited by Facebook or by the law. Here too, watchdog journalism depend on ‘soft’ forms of public accountability. In principle, journalistic fact-checking of microtargeted ads could offer a direct corrective to disinformation in the minds of citizens, but a growing empirical literature raises questions about the efficacy of this approach (Walter et al., Citation2020). If reporting on such issues is to have any accountability effect, therefore, it depends primarily on its capacity to catalyse a response from governments, platforms or other influential actors in advertising governance.

The journalism we describe here does not fit neatly in the bucket of ‘algorithmic accountability reporting’ (q.v. Diakopoulos, Citation2015). Our content analysis shows that algorithmic personalisation rarely features in Ad Library journalism, and instead points towards other aspects of platform advertising besides algorithmic decision making that warrant transparency in their own right, such as ad content, spending and buyer identities, (q.v. Leerssen, Citation2020). Our interviews clarify that this lack of algorithmic accountability reporting is certainly not for a lack of journalistic interest – many of our participants were in fact eager to investigate targeting practices – but rather a lack of data access. As we discuss further below, this illustrates clearly how Facebook’s disclosure policies constrain and shape reporting practices.

Critical perspectives on Ad Library journalism

Having discussed some of the Ad Library’s benefits, we now turn to more critical reflections. Firstly, the public interest value of Ad Library journalism is not given but debatable. Two of the journalists we spoke to already raised tentative questions about merely descriptive campaign reporting based on Ad Library spending data; was this not so much more ‘low-hanging fruit’ or ‘horse-race coverage’ (q.v. Aalberg et al., Citation2012)? Particularly where Ad Library reporting merely restates aggregate spending data without further contextualisation or analysis, the public interest value of this reporting need not be overstated. Indeed, besides the high-minded ideals of watchdog journalism, more mundane considerations such as mere novelty and availability may also factor into Ad Library usage.

Secondly, the Ad Library’s limitations and inaccuracies may even pose risks to journalism. First, its data may not always be reliable; for instance, journalists depend on Facebook to identify political ads even though we know this process to be inaccurate. Second, the available data may divert attention away from other, unauthorised topics, such as reporting on microtargeting or on non-advertising content. Recalling Facebook’s ongoing crackdown on independent data collection, they appear to be pursuing a carrot-and-stick approach in which, through the selective granting and withholding of relevant data, reporting is confined to approved topics. In this light, our research illustrates and underscores the concern, also voiced by others including Dommett (Citation2021), that their control over public transparency resources may help platforms to exercise undue influence on journalistic agendas.

A related concern, voiced by several participants, is that the presentation and ordering of the Ad Library’s data could mislead reporters, especially non-experts. Given that the journalists we spoke to tended to be highly critical of the Ad Library and aware of its shortcomings, the risk of deception may not be particularly acute at present. It could exacerbate in future, should the Ad Library become more popular amongst a broader set of journalists. Academic partnerships may have a role to play here: projects such as the NYU Ad Observatory and the University of Amsterdam Verkiezingsobservatorium now seek to assist non-expert journalists in using the Ad Library.

Limitations

It bears repeating that our sample of LexisNexis articles does not capture all journalistic usage of the Ad Library, and therefore understates the overall scale of this phenomenon. The most fundamental limitation of our approach is that our sample does not include online journalism, which is appreciable but more difficult to operationalise in any consistent or comprehensive fashion. Indeed, our interviews and pilot study indicate that certain online, tech-focused outlets are particularly frequent users of the Ad Library, including ProPublica, The Markup, and Buzzfeed News. Even broader conceptions of journalism might also consider Ad Library usage by NGOs and activist groups, such as the widely-cited research by UK think-tank InfluenceMap about oil and gas companies advertising on Facebook (Influencemap, Citation2019). Our analysis of print media, then, is by no means exhaustive of the journalism in this space but should merely be seen as indicative of its general order of magnitude, geographical distribution, and composition.

A related limitation is that our keyword-based sampling does not capture usage which does not reference the Ad Library explicitly. We did not cover reporting that neglects to cite the Ad Library, uses non-standard nomenclature such as ‘public database’, or simply cites ‘Facebook’ as a generic source. One might expect this approach to bias our content analysis towards metacoverage, on the theory that metacoverage is more likely to explicitly refer to the Ad Library by name. However, with supplemental testing we detected no such bias. As detailed in Appendix II, alternative keywords such as <‘facebook’ AND ‘political ads’> still return comparable rates of metacoverage.

Related to the above, there may be instances where the Ad Library surfaced an initial lead for journalists, even if it did not feature as a source in any ultimate publication. For instance, Washington Post reporter Nitasha Tiku recounted on Twitter how she started reporting on Facebook’s pharmaceutical advertising policies after she ‘fell into a Facebook Ad Library rabbit hole’.Footnote2 The Ad Library is not used as a source in the published article, but it did start Tiku towards a newsworthy investigation.

Finally, we have not yet charted in detail the interaction between journalists and other researchers in this space. Numerous stories in our sample did not rely on original journalistic research, but instead originated from academic studies of the Ad Library. Accordingly, our sample may somewhat overstate the degree to which journalists actually use the Ad Library, rather than reporting on Ad Library research conducted by others such as academics.

VI. Conclusion

This article has shown that, for all its flaws, the Ad Library has started to find uptake in journalistic practice. Our findings may serve as both an encouragement and a warning.

On the one hand, we have shown how the Ad Library has enabled new forms of watchdog journalism about online ad campaigns and, in some instances, wrongdoings such as hate speech, disinformation, and astroturfing. Even where no particular wrongdoing is uncovered, this reporting could conceivably strengthen public deliberation in and about microtargeting practices. These findings lend empirical weight to the rationale of public ad archives as a tool for public accountability, and underscore the role of journalists in realising these goals.

On the other hand, the growing reliance on this tool by journalists also poses risks. First, the data shared by Facebook has been shown to be incomplete and inaccurate, and could potentially mislead journalists. Second, this new resource may also divert attention from issues that Facebook refuses to document in similar detail, such as their targeting practices and non-advertising content. Indeed, given that most articles did not report on any particular wrongdoing, but instead consisted of either relatively uncritical campaign reporting or, even more commonly, coverage about the Ad Library itself, it could be argued that this tool has received outsized attention relative to the actual watchdog journalism it has enabled.

This research has several implications for the regulation of ad archives, as is now being prepared in various jurisdictions. Given that journalists are starting to rely on this data, ensuring its accuracy, comprehensiveness and consistency is all the more urgent. At the same time, our findings underline that this issue may be less critical in countries where political microtargeting is less prevalent compared to hotspots such as the United States and the United Kingdom.

Future research might build on these findings in various ways. As mentioned, more detailed process tracing could help to demonstrate how and when reporting on online ads triggers accountability effects in particular instances. Usage by other groups besides journalists also merits attention, such as by rival campaigners, consumers, commercial entities, regulators and courts (cf. Kwoka, Citation2016). From teenagers trawling the Ad Library for discount codes (Griffin, Citation2020), to courts and parliamentary committees citing it as evidence (Campaign Legal Center v FEC, Citation2020; Grygiel & Sager, Citation2020), our newfound public access to personalised advertising campaigns may have wide-ranging consequences, which this article has only begun to chart. More generally, future research might examine other tools through which platforms structure access to their data, such as CrowdTangle, and how these affect our capacity for public accountability.

Supplement Material

Download (9.5 KB)Supplement Material

Download MS Word (19.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank our interview participants for their time and insight, and Laura Edelson for her valuable input. We are also grateful to the editors and anonymous peer reviewers of Information, Communication and Society for their thoughtful, insightful, and thorough assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paddy Leerssen

Paddy Leerssen is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam. [email: [email protected]]

Tom Dobber

Tom Dobber is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Amsterdam. [email: [email protected]]

Natali Helberger

Natali Helberger is a University Professors at the University of Amsterdam. [email: [email protected]]

Claes de Vreese

Claes de Vreese is a University Professors at the University of Amsterdam. [email: [email protected]]

Notes

1 Readers should note that the Ad Library’s policies and affordances change frequently and may have changed since our time of writing. Our description is based on public Facebook policies as of July 2021, which are available through the archival tools Perma.cc (Facebook, Citation2021a) and Wayback Machine (Facebook, Citation2021b).

References

- Aalberg, T., Strömbäck, J., & de Vreese, C. (2012). The framing of politics as strategy and game: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 162–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427799

- Ali, M., Sapiezynski, P., Bogen, M., Korolova, A., Mislove, A., & Rieke, A. (2019). Discrimination through optimization: How Facebook’s Ad delivery Can lead to biased outcomes. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, Vol. 3(No. CSCW)), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359301

- Ananny, M., & Crawford, K. (2018). Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability. Social Media + Society, 20(3), 973–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816676645

- Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

- Birkner, T., Koenen, E., & Schwarzenegger, C. (2018). A Century of Journalism History as Challenge Digital archives, sources, and methods: Digital archives, sources, and methods. Digital Journalism, 6(9), 1121–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1514271

- Bodo, B., Natali, H., & De Vreese, C. (2017). Political microtargeting: A manchurian candidate or a dark horse? Internet Policy Review, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2017.4.776

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x

- Campaign Legal Center v. Federal Elections Commission. (2020). Complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief. Case 1:20-cv-00588. https://www.fec.gov/resources/cms-content/documents/clc_200588_complaint.pdf

- Diakopoulos, N. (2015). Algorithmic accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digital Journalism, 3(3), 398–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.976411

- Dobber, T., Ó Fathaigh, R., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. (2019). The regulation of online political micro-targeting in Europe. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1440

- Dommett, K. (2020). Regulating digital campaigning: The need for precision in Calls for transparency. Policy & Internet, 12(4), 432–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.234

- Dommett, K. (2021). The inter-institutional impact of digital platform companies on democracy: A case study of the UK media’s digital campaigning coverage. New Media & Society, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816676645

- Edelson, L., Lauinger, T., & McCoy, D. (2020). A Security analysis of the Facebook Ad library. Proceedings - IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP. https://doi.org/10.1109/SP40000.2020.00084

- Edelson, L., Sakhuja, S., Dey, R., & McCoy, D. (2019). An Analysis of United States Online Political Advertising Transparency. arXiv:1902.04385 [cs.SI].

- Facebook. (2021a). What is the Facebook Ad Library and how do I search it?. Facebook Business Help Center. https://www.facebook.com/business/help/214754279118974?id=288762101909005 [https://perma.cc/67MB-ULNV]

- Facebook. (2021b). Ads about Social Issues, Elections or Politics. Facebook Business Help Center. https://web.archive.org/web/20210415224853if/

- Flyverbom, M. (2019). The digital prism: Transparency and managed visibilities in a datafied world. Cambridge University Press.

- Fung, A. (2013). Infotopia: Unleashing the Democratic power of transparency. Politics & Society, 41(2), 183–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329213483107

- Gorton, W. (2016). Manipulating citizens: How political campaigns’ Use of behavioral Social Science harms democracy. New Political Science, 38(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393148.2015.1125119

- Griffin, A. (2020, August 11). Tiktok user reveals ingenious Facebook trick to find hidden discount codes. The Independent, https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/discount-codes-facebook-ad-library-tik-tok-a9665221.html

- Grygiel, J., & Sager, W. (2020). Unmasking uncle Sam: A Legal test for identifying State media. UC Irvine L. Rev, 11.

- Heawood, J. (2018). Pseudo-public political speech: Democratic implications of the Cambridge analytica scandal. Information Polity, 23(4), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-180009

- Hounsel, A., Mathias, J. N., Werdmuller, B., Griffey, J., Hopkins, M., Peterson, C., & Feamster, N. (2019). Estimating Publication Rates of Non-Election Ads by Facebook and Google. Draft article. https://github.com/citp/mistaken-ad-enforcement/blob/master/estimating-publication-rates-of-non-election-ads.pdf

- InfluenceMap. (2019). Big Oil’s Real Agenda on Climate Change. https://influencemap.org/report/How-Big-Oil-Continues-to-Oppose-the-Paris-Agreement-38212275958aa21196dae3b76220bddc

- Kemper, J., & Kolkman, D. (2019). Transparent to whom? No algorithmic accountability without a critical audience. Information, Communication & Society, 22(14), 2081–2096. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1477967

- Kim, Y., Hsu, J., Neiman, D., Kou, C., Bankston, L., Yun Kim, S., Heinrich, R., Baragwanath, R., & Raskutti, G. (2018). The stealth media? Groups and targets behind divisive issue campaigns on facebook. Political Communication, 35(4), 515–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1476425

- Kreiss, D., & Barrett, B. (2020). Democratic tradeoffs: Platforms and political advertising. Ohio State Technology Law Journal, 16(493), 493–519.

- Kwoka, M. (2016). FOIA, Inc. Duke Law Journal, 65(1461), 1361–1437.

- Leerssen, P. (2020). The soap Box as a black Box: Regulating transparency in Social Media recommender systems. European Journal of Law and Technology, 11(2).

- Leerssen, P., Ausloos, J., Zarouali, B., Helberger, N., & De Vreese, C. (2019). Platform Ad archives: Promises and pitfalls. Internet Policy Review, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1421

- Lourenco, P. (2016). Evidence of an open government data portal impact on the public sphere. International Journal of Electronic Government Research, 12(3), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEGR.2016070102

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

- Mccracken, G. (1998). The long interview. Sage.

- Meijer, A. (2014). Transparency. In M. Bovens, R. Goodin, & T. Schillemans (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public accountability. Oxford University Press.

- Miller, J. (2009). Regulating robocalls: Are automated Calls the sound of, or a threat to, democracy? Michigan Technology Law Review, 16(1), 213–253.

- Moore, M., & Tambini, D. (2018). Digital dominance: The power of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple. Oxford University Press.

- Mozilla. (2019). Data Collection Log — EU Ad Transparency Report. Mozilla Ad Transparency. https://adtransparency.mozilla.org/eu/log/

- Norris, P. (2014). Watchdog journalism. In M. Bovens, R. Goodin, & T. Schillemans (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public accountability (pp. 525–543). Oxford University Press.

- Quarati, A., & De Martino, M. (2019). Open government data usage: a brief overview. IDEAS ‘19: Proceedings of the 23rd International Database Applications & Engineering Symposium.

- Rieke, A., & Bogen, M. (2018). Leveling the Platform: Real Transparency for Paid Messages on Facebook. UpTurn Report. https://www.upturn.org/static/reports/2018/facebook-ads/files/Upturn-Facebook-Ads-2018-05-08.pdf

- Riffe, D., Lacy, S., Watson, B., & Fico, F. (2014). Analyzing media messages. Using quantitative content analysis in research. Routledge.

- Safarov, I., Meijer, A., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2017). Utilization of open government data: A systematic literature review of types, conditions, effects and users. Information Polity, 22(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-160012

- Sellars, A. (2020). Facebook’s threat to the NYU Ad Observatory is an attack on ethical research. NiemanLab. https://www.niemanlab.org/2020/10/facebooks-threat-to-the-nyu-ad-observatory-is-an-attack-on-ethical-research/

- Silva, M., Santos de Oliveira, L., Andreou, A., Olma Vaz de Melo, P. G., & O., Benevenuto, F. (2020). Facebook Ads Monitor: An Independent Auditing System for Political Ads on Facebook. WWW ‘20: Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020

- Walter, N., Cohen, J., Holbert, L., & Morag, Y. (2020). Fact-Checking: A meta-analysis of what works and for whom. Political Communication, 37(3), 350–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1668894

- Weaver, D. H., Beam, R. H., Brownlee, B. J., Voakes, P. S., & Cleveland Wilhoit, G. (2007). The American journalist in the 21st century: US News people at the Dawn of a New millennium. Routledge.

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, F., Möller, J., Kruikemeijer, S., Ó Fathaigh, R., Irion, K., Dobber, T., Bodo, B., & De Vreese, C. (2018). Online political microtargeting: Promises and threats for democracy. Utrecht Law Review, 14(1), 82. doi:10.18352/ulr.420