ABSTRACT

In this article we theorize a new organizational face of political parties that we term the ‘party-on-the-net’, defined as a set of digital partisan activist roles enabled by the affordances of digital technologies. We first explain the conceptual advantages of understanding parties’ media hybridization as an organizational face rather than as a specific party subtype. Then, we provide a taxonomy of digital partisan roles comprising the party-on-the-net and its links with traditional party bureaucracies and functions. We define and discuss ten roles on the basis of two general organizational variables, namely functional alignment with party structures and influence over core party decisions. Finally, after illustrating each of these roles through examples across different geographical regions, we consider how our framework can help scholars to develop hypotheses for further empirical scrutiny. We focus on the relative prevalence of the party-on-the-net within subtypes of digital parties, its relation to other organizational faces, and its development under different institutional scope conditions.

The centrality of digital technologies for political communication, participation, and activism has only increased during the last two decades, hybridizing the strategies of political actors and the manner in which they organize state-society linkages (Chadwick, Citation2017). As principal vehicles of political participation and mobilization, political parties have rapidly adapted to these changes, becoming increasingly capable of devising strategies that exploit digital opportunity structures across online and offline arenas. Scholarly work has granted significant attention to how digital technologies incentivized parties to modify core organizational processes, from political messaging and campaigning, funding, and decision-making, to interest-aggregation and the mobilization of support (Barberà et al., Citation2019; Chadwick & Stromer-Galley, Citation2016; Gibson et al., Citation2017; Guess et al., Citation2021; Kreiss, Citation2016; Lobera & Portos, Citation2021; Roemmele & Gibson, Citation2020; Scarrow, Citation2015). Some scholars have gone even further, theorizing digital parties as a new contemporary subtype of partisan organization. These parties are conceived as making the ‘connective’ and participatory logic of digital platforms constitutive of new visions of party democracy and therefore offering more dynamic and adaptive (though not necessarily more inclusive) forms of political participation (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Deseriis, Citation2020; Gerbaudo, Citation2019; Hartleb, Citation2013).

Despite the many contributions of this literature, we contend that focusing on political parties as the main unit of analysis carries limitations in terms of how we understand and study hybridization within party organizations. While some scholars acknowledge that modes of affiliation and partisan involvement have diversified and become more fluid and ‘multi-speed’ (Scarrow, Citation2015), the line of analysis goes mainly from the party outwards. This focus obscures the fact that not only linkage functions and membership types are hybridizing, but also a broader spectrum of partisan activity and activism that spans from followers and audiences all the way up to politicians and party leaders (Vaccari & Valeriani, Citation2016). A second limitation has been the association of digital parties with enhanced internal democracy and a small sample of European cases – mainly the Spanish party Podemos, the Italian Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S), and small pirate parties. This case selection bias curtails the fact that hybridization is a pervasive phenomenon cutting across most, if not all, party types and forms (Gerbaudo, Citation2021).

These limitations underline the need to widen our understanding of the relationship between digital affordances and party politics: How does hybridization affect different types of party organization? More specifically, how can we account for the myriad of hybrid organizational arrangements and partisan activities being enabled by digital affordances? And how do these relate to more conventional ‘non-digital’ functions within political parties?

To tackle these questions, we adopt a sociological perspective that allows for the study of hybridization as a process affecting partisan roles and role functions across any type of party organization. A role traditionally refers to patterned actions shaped by the position an individual or group occupies within a social institution or organization. Following Goffman (Citation1972:, p. 76), in this article we shift the unit of role analysis from the individual to the system of activity where different roles intersect. Thus, we define the partisan digital activist role-set as a stable group of positions within a party organization that are shaped by the affordances of digital technologies, embodying practices and patterns of action that link traditional and digital forms of social interaction and political communication in the service of a political party.

As we explain ahead, moving the discussion from digital parties to partisan digital activist roles provides several advantages for understanding digital partisan hybridization. First, it dissolves the insider/outsider frontier of party organizations to consider a broader role-set of digitally-enabled forms of partisan activity and routine involvement beyond membership. In this regard, we acknowledge that certain partisan roles involve repertoires of action that intendedly foster support for a party organization while simultaneously blurring its boundaries, thus encouraging ‘organizational hybridity’ (Chadwick, Citation2007). Second, this role-set can be understood as a distinct organizational face of party organization (Katz & Mair, Citation1993) that we denominate ‘the party-on-the-net’ (PoNet), which co-exists with other organizational faces parties usually develop. This conceptual move avoids reductive dichotomies found in the study of digital parties (i.e., digital vs non-digital parties, or legacy vs digital native parties) while opening a treatment of hybridization based upon the study of how concrete digitally-enabled roles articulate with other party structures and functions. Third, our framework facilitates a more comprehensive and integrated consideration of concepts and findings spread across multiple literatures and subfields that do not often engage with each other (i.e., party politics, social movement studies, communication and media studies, organizational sociology), offering a novel approach to examine and discuss parties’ digital hybridization.

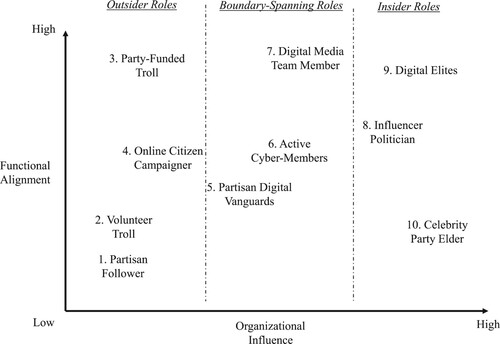

The article is organized as follows. In the first two sections, we conceptualize the PoNet as an organizational face and provide an original taxonomy of digital partisan activist roles based on two variables: the level of functional alignment of different roles with the party organization, and the degree of influence these roles enjoy within the party’s bureaucratic structure. Combining analytical reasoning with inferences drawn from an extensive and interdisciplinary review of the literature, we identify ten roles, comprising outsider activist roles, ‘boundary-spanning’ ones at the interface of party structures and civil society, and insider roles constituting the elite-side of digital partisan politics. Finally, we discuss general theoretical expectations regarding how the PoNet may intersect with other organizational faces, as well as relevant factors conditioning party organization and behavior, outlining relevant hypotheses for future empirical inquiry.

1. The party-on-the-Net: a new organizational face of political parties

Richard Katz and Peter Mair (Citation1993, p. 594) coined the concept of ‘organizational face’ to distinguish distinct subsystems within party organizations organized around their own ‘set of resources, constraints, opportunities, and patterns of motivation.’ Abandoning classical dichotomies used for the analysis of political parties (i.e., parliamentary vs. extra-parliamentary, leadership vs. bureaucracy, etc.), they contended that modern party organizations had become highly diversified and specialized, and that a full analysis should encompass how different bureaucratic subsystems relate to one another. In their original treatment, Katz and Mair identified three such subsystems, the party-in-public office (PPO), the party-on-the-ground (PoG), and the party central office (PCO), with the first roughly corresponding with election-dependent, office-holding politicians, the second with party members, local party committees, and party activists, and the third with the party’s executive leadership and core staff.

This approach opened an avenue for the study of political parties as organizational prisms rather than as unitary organizations, showing that the interrelation between distinct types of functional positions in each bureaucracy results in patterns of influence and competition that explain organizational adaptation and change. For example, mass parties of integration granted more influence to the PoG (i.e., via structures such as the party congress), while contemporary catch-all parties display a more influential PPO profile (Katz & Mair, Citation1993, p. 605). Similarly, each face configured general functional expectations, with the PoG being characterized by requirements in terms of voluntary membership, permanence, and regularity, and the PCO marked by elite centrality and staff expertise, often becoming the dominant locus of decision for all other faces.

By systematizing these distinctions and their implications, Katz and Mair’s approach inspired a generation of scholars interested in the internal functioning and evolution of political parties, facilitating classification and comparison within and across countries (Bardi et al., Citation2017; Ignazi, Citation2020; Katz & Mair, Citation2009; Poguntke et al., Citation2016; van Biezen, Citation2000). At the same time, it opened further opportunities for nuancing and extending the original tripartite conception of organizational faces. For example, Carty (Citation2004) proposed to see some parties as ‘stratarchical’ franchise systems where each face could operate with autonomy, while Heaney and Rojas (Citation2015) argued that parties can present a fourth face, the ‘party in the street’ (PiS). Studying the interactions between the US Democratic Party and the anti-war movement after 9/11, these authors emphasized the many overlapping and informal patterns of interaction, collaboration, and influence between parties and social movements. They ultimately showed how activists can hold ambiguous and shifting positions across the insider/outsider divide, assuming a changing partisan-movement orientation at different points in time.

We consider that the study of parties’ organizational faces is a conceptual and analytically insightful way to discuss how the digital sphere has reconfigured the ‘internal life of parties’ (Katz, Citation2002). Extending the notion that parties are heterogenous organizations where different faces coexist and often compete with each other, we claim that digital affordances affect and enable a variety of roles, which may differ in terms of their influence or salience within parties’ organizational processes. However, thinking in terms of hybridized partisan roles forces us to reconsider three important limitations in the current literature. First, we know that parties comprise roles that go beyond their internal bureaucracies, with membership and partisan action extending beyond the boundaries of the organization – blending with activism in the street, in state institutions, and so forth. Understanding hybridization within party organizations thus entails understanding how roles in the boundaries of political parties also rely on the affordances of digital media. Second, although the literature on political parties has generally assumed that organizational faces are composed of distinctive positions and functions, these have been understood in rather static terms. In fact, despite Katz and Mair’s best efforts to explain the dynamics and tensions arising from the intersection between organizational faces, the range of positions within each of the faces remains abstract and unclear. Lastly, although Katz and Mair briefly sketched some of these positions, they did not explain why and how these positions vary along each organizational face. As a consequence of these shortcomings, we lack a detailed mapping of how political parties’ organizational faces are composed of positions that (a) relate to one another within each face and across them, and (b) depend upon different structural constraints such as power distribution, functional alignment with party leadership, resource dependency, etc.

To overcome these limitations, we draw upon Goffman’s (Citation1972) sociological distinction between actor, role, and role-set. Actors are conceived as individuals (or collectives of individuals) transitionally or structurally positioned in specific roles, with roles defined as sets of normative demands brought upon them depending on their specific organizational position. When a particular individual say, is elected to public office, the normative demands expected by others will shift according to their new position. However, as Goffman (Citation1972:, pp. 75–76) argued, these normative demands – and therefore the role enactment of the actor – will vary depending on their relevant audiences. The politician performs one role when interacting with party officers, and another when interacting with their voters. This multi-faceted nature of roles is defined as role-sets, or bundles of roles that actors activate depending on their relevant audiences and the rewards provided by the institutions in which they act (Abrutyn & Lizardo, Citation2022).

Consequently, we contend that political parties’ organizational faces are composed not of individual or formally defined positions, but rather of role-sets that relate to one another. Because contemporary political parties present a significant bundle of roles involving digital affordances, we argue that the PoNet can be identified as a separate organizational face of political parties spanning a distinctive set of role positions marked by digital hybridization.

Conceiving the PoNet as an organizational face rather than a party subtype enables in turn a re-evaluation of partisan digital activism. Although several formats of digital activism have been identified in the literature (Karpf, Citation2017, p. 7), categorizations of partisan activism tend to follow a membership-oriented focus, seeking to elucidate how parties can marshal digital technologies and affordances to develop new organizational models or flexibilise the engagement of its members (Vaccari & Valeriani, Citation2016, p. 296; Gibson et al., Citation2017; Scarrow, Citation2015). Consequently, scholars focus on the hybridization of parties’ members, volunteers, or sympathetic audiences, rather than meso-level cadres or even party elites. On the contrary, our conception of the PoNet underscores the fact that party-related engagement can be highly heterogenous in its composition and functioning, with digital partisan activism stretching across its organizational boundaries. In other words, we conceive of hybridization as affecting not only members and supporters, but also boundary-spanning and insider roles that comprise functions related to coordination, communication, and leadership within a party organization.

Furthermore, given the multiple and simultaneous affordances offered by digital and social media technologies (i.e., networking, communication, visibility), we expect digital activist roles to be functionally diverse and differentially distributed across party structures. Hence, the PoNet cuts across different party families, organizational models, and political ideologies – although certain roles and organizational patterns are arguably more characteristic of some party types than others. This way, as our analysis ahead indicates, the PoNet can align with – or diverge from – other organizational faces to different degrees; for example, in certain cases digital roles could complement and reinforce the influence of the PiS, while in more electoral or populist parties they could be expected to serve the interests of specific party elites.

2. The PoNet from within: a taxonomy of digital partisan activist roles

To analyze the structuration of the PoNet, we consider two general axes of variation across partisan digital activist roles: functional alignment and organizational influence. Functional alignment refers to the degree to which a particular role is tightly coupled with the objectives of the prevailing party’s organizational face – as defined by the balance of power in each organization. Organizational influence, on the other hand, taps onto the relative influence of a role over strategic decision-making within the party’s organizational structure. We understand these variables in ordinal terms, seeking to expand the taxonomical property space of the partisan roles enabled by digital technologies (Elman, Citation2005, p. 308).Footnote1

On this basis, we analytically assess an array of concepts disseminated in the literature on political parties, social movements, and digital media politics, resulting in a taxonomy of ten digital activist roles. Ahead, we discuss these roles according to a three-partite segmentation of the property space of the PoNet: (a) outsider roles, (b) boundary-spanning roles, and (c) insider roles. We use intuitive labels to denominate role positions, seeking to avoid terminological proliferation and providing an inclusive framework that bridges findings across subfields.

2.1. Of partisan citizens and trolls: outsider roles

At the bottom left-hand side, we locate the looser affiliation roles enabled by the emergence of digital technologies. The least influential and aligned role, the digital partisan follower, represents the rank-and-file of the PoNet: individuals who through voluntary actions, such as sharing tweets or commenting posts, help promote the party brand in the digital sphere but nevertheless lack any formal commitment to the organization or direct interaction with it. As such, their activism is highly independent but limited in scope, reduced to a passive consumption of partisan communications or a more active promotion of partisan stances – either among their immediate acquaintances or through their social media networks (Cantijoch et al., Citation2016, p. 39; Scarrow, Citation2015, p. 31).

With a higher degree of alignment is the online citizen campaigner role. This role is associated with the contribution of digital technologies to ‘devolved electioneering’ party strategies, where online volunteers and ‘digitally-enabled activist networks’ assume functions that previously lied in the hand of formal members and official staff – such as canvassing or fund-raising. This arguably grants them more relative autonomy and tactical control over local operations (Gibson Citation2015: 187; Chadwick & Stromer-Galley Citation2016). This form of digital ‘citizen-initiated campaigning’ appears to be more common among weakly institutionalized, movement-like parties, which are more tolerant to multi-speed forms of affiliation and participation, and could be found in the campaigns of many outsider candidates and insurgent factions – as in the case of Barack Obama, Jeremy Corbyn, and Bernie Sanders.

In-between these more civic roles we locate two contentious ones, which we designate the volunteer troll and party-funded troll. The volunteer troll refers to individuals who, without any formal link with a party, devote their time to patrol social media content on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or the comment section of newspapers, for the purpose of ‘politically-tinged cyberaggression’ (Bauman, Citation2020, p. 6). Although some readers might find the decision to include trolling as a form of activism unusual, we see this role as the contentious counterpart of the partisan follower, even if the repertoire of choice is abusive or even illegal. Moreover, while we expect volunteer trolls to have extremely low organizational influence, they are a step upwards in terms of functional alignment in comparison to partisan followers. This is because the act of 'trolling’ implies a more active form of digital engagement than mere ‘following’ or ‘sharing’, with trolls investing time in screening and posting messages to create offense and ‘lure the unwary into pointless debate’ (Coles & West, Citation2016).

The party-funded troll plays a similar function but has more direct (and sometimes even clandestine) links to a party organization. These links can be personalized and associated with an individual politician, although party-sponsored trolling – given their generally illicit character – is often part of concerted strategies requiring significant insider orchestration or approval at high levels of the party (Grimme et al., Citation2017). For instance, the ‘troll army’ of the ruling Turkish party Justice and Development (AKP) was organized by the party’s vice-chairman, counting with a core team of around 30 people managing 6000 individuals (Bulut & Yörük, Citation2017).Footnote2

2.2. Of dual activism and cyber-vanguards: boundary-spanning roles

At the center of we situate three roles with hybrid insider/outsider functions – what organizational sociologists call ‘boundary-spanning’ roles given their key bridging position between internal and external actors within a social network or organization (Curnin, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2018).

The first of them are partisan digital vanguards. While the original concept of ‘digital vanguard’ was coined by Gerbaudo (Citation2017) to describe the tech-savvy activist collectives leading the high-visibility ‘power accounts’ of contemporary digital movements, such as the Spanish 15M Movement, Occupy Wall Street, #MeToo or Black Lives Matter, we argue that in certain contexts, these activists can adopt partisan positions, using their sharp skills and visibility to engage in electoral mobilization (McAdam & Tarrow, Citation2010; Penney, Citation2017). While this partisan stance might be temporary, it is nevertheless crucial for understanding the nexus between the PoNet and contentious actors. For example, the digital activists at the forefront of the mass anti-government protests shaking up Argentina and Brazil between 2012 and 2016 were initially skeptic of openly siding with opposition parties, self-organizing partly in response to the latter’s perceived weakness and complacency. However, their strong anti-government stance led them to ally with the opposition and to coordinate with them a series of protest and election-oriented actions, both online and offline (Gold & Peña, Citation2021). While in Argentina the groups opted to remain anonymous, in Brazil some leading figures decided to join parties and use their digital visibility to run for office, with a few of them getting elected to Congress while remaining active online.

Given the digital savviness and assertive militancy, we consider partisan digital vanguards can enjoy a more influential position within a party organization compared to citizen campaigners, even if this position is contextual and transient as a result of their contentious orientation. In fact, the ideological and strategic dilemmas they face in terms of balancing their activist identity and autonomy with partisan objectives is expected to restrict functional alignment (Gerbaudo, Citation2017; Heaney & Rojas, Citation2015), and there is evidence that the more aggressive and polarizing frames vanguard activists privilege in their digital communications can deter engagement from conservative party elites (Hacker & Pierson, Citation2020; Lobera & Portos, Citation2021). This suggests that this role may be more compatible with insurgent parties or outsider candidates, who are more inclined to the development of extra-institutional strategies.

The second role comprises active cyber-members. We extend the term beyond Scarrow’s definition – limited to members formally registered through an online platform and ‘encouraged to use on-line tools to campaign on the party’s behalf’ (Citation2015:, p. 30) – to encompass a broader array of partisan sympathizers, low-ranked and local party officials, campaign staff, non-members, journalists, and even celebrities, who show a clear partisan affinity and actively promote partisan political content in digital media platforms and networks. This role captures the activities of partisan sympathizers that have achieved a higher level of influence and/or centrality in digital circles and platforms, and therefore function as ‘opinion leaders’ (Dubois & Gaffney, Citation2014).

Cyber-members play a key intermediating role between the digital and non-digital domains. For instance, they often engage in militant ‘dual-screening’, this is, the simultaneous and frequent engagement ‘with political content at different levels of activity across older and newer platforms’ (Vaccari & Valeriani, Citation2018, p. 369), while relying on social media to leverage partisan ‘lean forward’ engagement practices – such as introducing comments or elaborating interpretations about salient events (Vaccari et al., Citation2015, p. 1056). We expect parties that recognize the advantage these committed cyber users can provide for mobilizing voters to align their repertoires and collaborate with them more closely. For example, they might grant them voice during campaigns or rallies or provide them with privileged material or ‘leaks’ to be distributed in the hybrid media sphere. These patterns are evident in the case of cyber-members that have a sizable online followership, such as Megan Rapinoe and Paul Krugman supporting Democratic Party candidates, or former Brazilian footballer Ronaldinho endorsing Jair Bolsonaro.

Differing from the previous two categories, we locate the role of digital media team members closer to the insider side of . This is because media team-related roles emerge from the institutionalization of a digital function within a party organization, generally tasked with designing, managing, and/or implementing a party’s online strategy, and are expected to have very high functional alignment. Thus, as far as political parties experience organizational pressures to adopt more decentralized advocacy strategies enabled by new digital technologies, they have increasingly shifted to a professionalized model of online activism. This model involves hiring ‘staffers with specialized skills in technology, digital, data, and analytics’ from outside the political field and granting them influence over electoral strategies or occupying senior roles within the PCO (Karpf, Citation2017; Kreiss, Citation2016, p. 208). Some of these roles, as in the case of top media strategists or consultants, may enjoy substantial independence from institutional hierarchies and party elites, and even serve multiple parties or candidates simultaneously.

A paradigmatic example of a leading digital media team member is Joe Rospars, who owned the company behind Howard Dean’s media presence in 2003 and was put in charge of the New Media department during Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. His division was made ‘responsible for everything related to the Internet beyond the technical areas, including all of the organizing, communications, and fundraising aspects of what is happening online’ (Aaker & Chang, Citation2009, p. 3), coordinating several dozens of party staffers. Similar trajectories can be found across large party organizations in most countries, with famous digital strategists ranging from Steve Bannon in the US to Gianroberto Casaleggio (the digital entrepreneur behind the rise of Beppe Grillo and the Italian M5S party), to Jaime Durán Barba (a famous Ecuadorian consultant who worked in various campaigns in Latin America).

2.3. Of digital influence and party elites: insider roles

The three remaining categories comprise the elite side of the PoNet, involving roles with high organizational influence which vary in terms of their level of functional alignment and core characteristics. Starting off with the role of influencer politician, this category comprises insider figures who have developed a substantial online presence and routinely use social media to communicate with different publics and engage in ‘performed connectivity’, digitally packaging the professional and/or private side of their lives to establish a more informal, interactive, spontaneous, and personalized connection with their supporters, portraying themselves as ‘acting out their politics’ (Street, Citation2019; Wood et al., Citation2016).

The increasing importance of digital followership as a metric of political appeal entails that ‘digital visibility’ has become a source of influence and status within a party organization, enabling different degrees of autonomy from authorities in the POC and the PPO. The case of Donald Trump is illustrative of this: a political outsider who had constructed a public persona ‘from populist circuses of pro wrestling and New York tabloids, via reality television and Twitter’ (Sullivan 2016, quoted in Street, Citation2019, p. 6), and whose amateurish yet more authentic political communication style allowed him to displace established Republican elites and mobilize insider factions (Macwilliams, Citation2016). With different styles, similar stances can be found in other countries. In Canada, the popularity of Justin Trudeau has been linked with a carefully crafted, casual and progressive ‘sunny ways’ public brand that Trudeau promoted both on- and offline prior and after his election (Lalancette & Raynauld, Citation2019, p. 891). Similarly, Matteo Salvini’s social media presence, supported by a well-resourced media team, has been considered central for his ability to take control over the political messaging of the renovated Lega Nord in Italy, bypassing the party elite (Albertazzi et al., Citation2018).

A step upwards in influence and alignment points to digital leadership positions within a party with major input in the overall party agenda and strategy. For this reason, we refer to this role as digital elite, as we consider that its centrality can be expected in the more hybrid cyber-party organizations that not merely rely on digital technologies and platforms to enhance electoral strategies, but incorporate their logics into core organizational processes and identity (Deseriis, Citation2020; Gerbaudo, Citation2019; Vittori, Citation2020). A salient example is the founder of the anti-establishment M5S party Beppe Grillo, a charismatic comedian who acquired his political popularity due to his political blogging. With the support of the already mentioned Gianroberto Casaleggio, Grillo launched his blog and organized the use of Meetups to create the ‘networked activist base’ of the M5S at both local and national levels (Deseriis, Citation2020, p. 1776). Similar cases can be found in the leadership of other iconic digital parties, such as the Spanish Podemos, referred by Kioupkiolis and Pérez (Citation2019) as a ‘transmedia party’, and among the leadership and membership of pirate parties, which explicitly seek to conflate a digital activist network with an electoral organization (Otjes, Citation2020; Paulin, Citation2020).Footnote3

The last role is an unusual, analytically deducted category, comprising an elite position that combines a high level of influence with a low level of functional alignment. We denominate this role the celebrity party elder, which refers to a partisan elite activist who enjoys a significant degree of moral or charismatic authority but is not constrained by bureaucratic hierarchies, given their official retirement from institutionalized party politics. Due to this autonomy, elder figures operate as ‘rogue insiders’: they are highly associated with a party brand but enjoy considerable independence from it. Some characteristics of elder roles have been noted in the literature. For instance, Anderson (Citation2010) examined how former US presidents tend to become preoccupied with their historical legacy and the lessons they want to see passed to newer generation of political leaders. While these aims can be promoted in a number of ways, elder political figures often assume a ‘custodian function’ by commenting on the suitability of the strategies adopted by their former parties. These opinions may not sit well with current political leaders, with Anderson (Citation2010:, p. 76) noting that the Clinton and Bush administrations were often annoyed by the ‘freelance diplomacy’ of former president Jimmy Carter.

New digital affordances arguably deepen the capacity of celebrity party elders to influence internal debates and shape public opinion. Although we may be witnessing the ascendance of the first generation of such figures, we already note akin behaviors. While former US presidents tend to refrain from attacking their successors, Barack Obama, who remains highly popular among democrats and independents, has frequently used Twitter to criticize then President Trump for inciting the Capitol Hill attack, while actively supporting Biden’s campaign. Similarly, former Brazilian president Lula da Silva, who was disqualified for running for office after his 580-day imprisonment, has been overly critical in social media of both Jair Bolsonaro’s government and some decisions undertaken by his own party, the Workers’ Party (PT). We expect this role to become more prominent as future generations of party leaders gain elder status. Indeed, it is not hard to imagine figures like Beppe Grillo, Pablo Iglesias, or perhaps Donald Trump, remaining active both online and offline to influence partisan debates after their formal retirement .

Table 1. Digital Partisan Activist Roles and Examples.

The above taxonomy does not aim to be exhaustive, not only because other positions could be identified in countries that are not usually covered in the related literature, but also because the PoNet is an emergent organizational face experiencing continuous change and adaption. However, we consider that the ten roles described above offer a comprehensive and illustrative set of role positions, and therefore facilitate an indicative mapping of the organizational space that other roles could virtually occupy.

3. Discussion: a relational approach to partisan digitalization

In this section we discuss how a perspective centered on the PoNet as an organizational face enables new conceptualizations and expectations regarding the functioning of digital parties and the relationship between the PoNet and other faces. As discussed above, our ordinal distinction between types of roles within the PoNet entails that (1) the boundaries between these roles are fuzzy; (2) many of the tasks involved are not mutually exclusive, as individuals can occupy multiple roles simultaneously but also move between certain roles more or less easily (i.e., from digital follower to troll); and (3) any political party can support the development of some but not necessarily all PoNet roles, and therefore scholars must identify the components of this role-set on a case-by-case basis. Taking these propositions into account, we establish below a set of hypotheses that can guide further lines of theoretical elaboration and empirical research on the PoNet, its relation to other organizational faces, and its behavior under different scope conditions.

3.1. Subtypes of digital party organization

First, the taxonomy makes clear that restricting the digital party type to ‘participationist’ and anti-elitist parties advocating for digital democracy practices is overly reductive, particularly because leading proponents of this view began to acknowledge the problematic synergy that digital technologies can have with vertical mode of party-society relations (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Gerbaudo, Citation2018; Kriesi, Citation2014). Our approach offers a more parsimonious and encompassing definition of the ‘digital party’ as a type of party organization where the PoNet prevails over all other organizational faces, independently of their ideological orientation and/or types of linkages with constituencies. Drawing upon this definition, we hypothesize that depending on the types of digital roles that prevail within a party’s organizational structure, three ideal subtypes can be distinguished: the digital populist party, the digital campaign party, and the digital movement party.

We expect the first to develop in cases where digital insider/elite roles prevail over more intermediate and outsider positions, and therefore exert an ordering influence over the other organizational faces. To the extent that digital technologies are leveraged to support more effective vertical models of linkage, this would point in the direction of leader-centric, hollowed-out party organizations such as the UK Brexit Party, described as a ‘digital startup’ and, according to its founder, inspired on both the M5S and the uni-personal Dutch PVV (Peña, Citation2021, p. 648). A less radical form would entail the use of digital technologies in a plebiscitarian fashion, mobilizing the base of the party at the expense of its bureaucracy. Both the M5S and Podemos have been described as moving in this direction (Gerbaudo, Citation2019).

In contrast, the digital campaign party develops when intermediate activist roles prevail, with digital vanguards or digital media teams gaining functional authority and becoming the core of partisan mobilization. In these cases, digital vanguards could decide to align with the goals of party elites and become the digital wing of a party, contributing to electoral mobilization. Alternatively, some grassroots digital activist or vanguard leaders could translate their visibility into celebrity status and use it to access public office. Many of the leaders of the Movimento Brazil Livre, instrumental during the impeachment campaign of President Rousseff, later joined political parties and ran for office (Gold & Peña, Citation2021). Alternatively, if media teams prevail, we could be in the presence of a new digital variant of the ‘business firm’ party, where a small group of political entrepreneurs set the party agenda positions on the advice of a well-resourced team of public relations and digital media specialists (Hopkin & Paolucci, Citation1999).

Finally, the digital movement party presumes a strong alignment of outsider, intermediate, and elite roles, and a dedicated attempt to maximize the influence of grassroots PoNet roles across the entire party organization. Relying on digital technologies and collaborative platforms, key party functions would aspire to contribute to the deliberative ideal of online democracy, while members, politicians, and elites are expected to share an explicit digital activist orientation. As with traditional movement parties, the difficulty of maintaining this horizontal balance in light of both internal and external pressures (Kitschelt, Citation2006) makes this configuration rare and rather unstable, with pirate parties being the closest to a successful case.

3.2. Complementarities and tensions between organizational faces

In cases where the PoNet does not prevail over other organizational faces, scholars can disentangle how subsets of digital activist roles become coherent (or not) with more conventional party types. In this sense, our taxonomy facilitates an analytical discussion of diverse alignments, complementarities, and tensions that may arise between the PoNet and other organizational faces.

A first issue relates to questions about trajectories of digital hybridization. Assuming that in most parties the PoNet emerged after and atop other faces, digital partisan activist roles are initially expected to complement the preexisting balance of power between faces, and the general party type orientation. For instance, an affinity has been noted between populist leaders and ‘outsider’ digital roles, which enable the former to balance their exclusive elite-oriented identity by deploying vertical linkages with voters and sympathizers. Some scholars consider this affinity to be stronger among contemporary right-wing populist parties – as they are more capable of reconciling elites' influence and visibility with low-influence but functionally-aligned cadres (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Hacker & Pierson, Citation2020).

However, just as Katz and Mair (Citation1993:, pp. 614–16) considered that the mass media would lead to the decline of the PCO because ‘most of the services it provides can now be secured through alternative means’, we expect these initial alignments to change over time, as the salience of digital affordances put PoNet roles in conflict or competition with other party roles and functions. Thus, it is unsurprising that the digital populist affinity seems to be stronger during electoral campaigns rather than periods in which these parties occupy public office, when populist leaders need to rely on organizational structures outside of the PoNet – particularly the PPO – to solve daily problems related to governance. Similarly, Lobera and Portos (Citation2021, p. 1432) suggest that social media affordances favor a closer alignment between the PiS and the PoNet, benefiting resourceful PiS activists who rely on social media to ‘hack’ the official campaign and become ‘central actors of new political intermediations in the digital public sphere.’

A second related but understudied trend is the central role of digital media teams within contemporary party politics. While much of the literature has focused on the ‘death of the party cadre’ within a particular subset of Western European digital parties (Gerbaudo, Citation2019; Hendriks, Citation2021), contemporary party organizations are developing re-centralizing hybrid strategies that may grant greater influence to boundary and insider digital roles, such as digital media teams or influencer politicians. This trend raises important questions in terms of how the historical development of the PoNet will affect the internal distribution of power across other faces. For example, where do media team members locate in terms of partisan bureaucratic composition? And how do different elite roles leverage digital affordances in their (or their party’s) favor? While current findings suggest a constant decline of the PCO in favor of new entanglements between the PoNet, the PoG/PiS, and the PPO, we need more studies outside of Europe and the US that could inform new patterns of hybridization over time.

3.3. The PoNet across different institutional contexts

Finally, future work can also explore how the relative salience of the PoNet, and its roles vary across different institutional conditions. For example, an emergent literature has focused on extreme examples of party digitalization, such as pirate parties. However, these organizations emerged in stable multiparty systems within European parliamentary democracies, and therefore are much less likely to be found in other institutional contexts. By limiting our analysis to these conditions, scholars miss not only insights about how parties outside of Europe are merging the role-set of the PoNet with other organizational faces, but also regarding the conditions under which specific types of hybridization are most likely to emerge from. Although we lack further comparative studies on these trends, we can already notice that less institutionalized party systems seem to increase the likelihood of certain roles becoming more autonomous from the PPO and PCO, such as grassroots digital vanguards or influencer politicians. When combined with multiparty systems – as in the cases of Brazil or Italy – these actors could even trump the PPO, leading the creation of a new party or aligning internal cadres in their favor.

Similarly, we lack studies mapping and understanding how PoNet roles work beyond democratic regimes. Based on current findings, we hypothesize that roles with low organizational influence might be used for the support of autocratic regimes, with more ‘insider’ roles being vertically replaced by the party in office (PPO). However, opposition parties might simultaneously develop what we have termed above a ‘digital campaign’ subtype, with intermediate activist roles prevailing in order to develop contentious strategies. Although plausible, the degree to which this combination can be found across authoritarian regimes remains an open question.

4. Conclusion

This article provides a theorization of political parties’ digital hybridization through the conceptualization of a new organizational face, which we term the party-on-the-net. After fleshing out the many possibilities this concept provides for understanding the variegated internal composition of political parties, we define and theorize ten digital activist roles located within, outside, and in the boundaries of party organizations. We show how these roles go beyond but also combine with traditional forms of party organization, membership, and partisan militancy. By fleshing out the affordances of each role and their interrelation within the PoNet, our framework opens new possibilities for analyzing party hybridization in any political setting.

Our approach to party hybridization undertakes a different perspective to that of current studies posing that digital technologies are leading to the thinning of party organizations. We contend that to the extent that digital partisan activist roles associated with the PoNet are coherent with most, if not all, party forms and linkage strategies, we need further comparative studies to disentangle its differential effects and characteristics across countries and regions. As such, we outline three fruitful areas of research: the conceptualization of new subtypes of digital parties, the analysis of complementarities and tensions between parties’ organizational faces, and the disentanglement of the scope conditions under which certain roles are more likely to prevail over others. Better understanding variation in how the PoNet develops over time will most likely lead to more accurate and generalizable expectations regarding party hybridization, including different types of parties and a wider set of institutional conditions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the feedback provided by colleagues at the 2021 ECPR Joint Sessions Workshop ‘New Parties, New Party Members' (and especially to Oscar Barberà), the ‘The Conservative Dilemma: Digital Surrogate Organizations and the Future of Liberal Democracy’ Workshop, organized by the Social Science Research Council and the Institute for Data, Democracy and Politics at the George Washington University, and the 2022 ECPR Joint Sessions Workshop ‘Movement Parties: their rise, variety, and consequences’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alejandro M. Peña

Alejandro M. Peña is senior lecturer in international politics. He researches on contentious politics, international political sociology, and Latin American Politics, among other topics.

Tomás Gold

Tomás Gold is a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Notre Dame and research fellow at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies. His work focuses on explaining the dynamic interactions between political parties, social movements, and civil society organizations seeking to generate both cultural and political change, with a particular interest in conservative and free-market advocacy.

Notes

1 Though many people use the notions of taxonomy and typology interchangeably, we adopt the term taxonomy as most role positions are empirically inferred rather than theoretically deducted. See Bailey (Citation1994).

2 While most literature tends to associate this type of trolling with illiberal regimes, there is substantial evidence that more democratic and liberal governments and institutions sponsor troll-like activities, with comprehensive studies pointing to party-sponsored trolling in the US, Brazil, Italy, or India, among many others (Bradshaw & Howard, Citation2017).

3 While the first pirate party was created in Sweden in 2006 as an experimental organizational form, the Pirate Party International now declares 39 members.

References

- Aaker, J., & Chang, V. (2009). Obama and the Power of Social Media and Technology.

- Abrutyn, S., & Lizardo, O. (2022). A motivational theory of roles, rewards, and institutions. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12360

- Albertazzi, D., Giovannini, A., & Seddone, A. (2018). ‘No regionalism please, we are Leghisti !’ The transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. Regional & Federal Studies, 28(5), 645–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1512977

- Anderson, L. (2010). The ex-presidents. Journal of Democracy, 21(2), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.0.0166

- Bailey, K. D. (1994). Typologies and taxonomies: An introduction to classification techniques. Sage Publications.

- Barberà, O., Barrio, A., & Rodríguez-Teruel, J. (2019). New parties’ linkages with external groups and civil society in Spain: A preliminary assessment. Mediterranean Politics, 24(5), 646–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2018.1428146

- Bardi, L., Calossi, E., & Pizzimenti, E. (2017). Which face comes first? The ascendancy of the party in public office. In T. Poguntke, P. Webb, & S. E. Scarrow (Eds.), Organizing political parties: Representation, participation, and power (First edition). OUP.

- Bauman. (2020). Political cyberbullying: Perpetrators and targets of a new digital aggression. Praeger.

- Bennett, W. L., Segerberg, A., & Knüpfer, C. (2018). The democratic interface: Technology, political organization, and diverging patterns of electoral representation. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11), 1655–1680. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348533

- Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2017). Troops, trolls and troublemakers: A global inventory of organized social media manipulation. Oxford Internet Institute. https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/07/Troops-Trolls-and-Troublemakers.pdf.

- Bulut, E., & Yörük, E. (2017). Digital populism: Trolls and political polarization of twitter in Turkey. International Journal of Communication, 11, 4093–4117.

- Cantijoch, M., Cutts, D., & Gibson, R. (2016). Moving slowly up the ladder of political engagement: A ‘spill-over’ model of internet participation. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(1), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12067

- Carty, R. K. (2004). Parties as franchise systems: The stratarchical organizational imperative. Party Politics, 10(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068804039118

- Chadwick, A. (2007). Digital network repertoires and organizational hybridity. Political Communication, 24(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600701471666

- Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system: Politics and power (Second Edition). OUP.

- Chadwick, A., & Stromer-Galley, J. (2016). Digital media, power, and democracy in parties and election campaigns: Party decline or party renewal? The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(3), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216646731

- Coles, B. A., & West, M. (2016). Trolling the trolls: Online forum users constructions of the nature and properties of trolling. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.070

- Curnin, S. (2016). Organizational boundary spanning. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance (pp. 1–5). Springer.

- Deseriis, M. (2020). Digital movement parties: A comparative analysis of the technopolitical cultures and the participation platforms of the Movimento 5 Stelle and the Piratenpartei. Information, Communication & Society, 23(12), 1770–1786. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1631375

- Dubois, E., & Gaffney, D. (2014). The multiple facets of influence: Identifying political influentials and opinion leaders on Twitter. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(10), 1260–1277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214527088

- Elman, C. (2005). Explanatory typologies in qualitative studies of international politics. International Organization, 59(2), 293–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818305050101

- Gerbaudo, P. (2017). Social media teams as digital vanguards. Information, Communication & Society, 20(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1161817

- Gerbaudo, P. (2018). Social media and populism: An elective affinity? Media. Culture & Society, 40(5), 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718772192

- Gerbaudo, P. (2019). The digital party: Political organisation and online democracy. Pluto Press.

- Gerbaudo, P. (2021). Are digital parties more democratic than traditional parties? Evaluating Podemos and Movimento 5 Stelle’s online decision-making platforms. Party Politics, 27(4), 730–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819884878

- Gibson, R. (2015). Party change, social media and the rise of ‘citizen-initiated’ campaigning. Party Politics, 21(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812472575

- Gibson, R., Greffet, F., & Cantijoch, M. (2017). Friend or Foe? Digital technologies and the changing nature of party membership. Political Communication, 34(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1221011

- Goffman, E. (1972). Encounters: Two studies in the sociology of interaction. Penguin University Books.

- Gold, T., & Peña, A. M. (2021). The rise of the contentious right: Digitally intermediated linkage strategies in Argentina and Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society, 63(3), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2021.23

- Grimme, C., Preuss, M., Adam, L., & Trautmann, H. (2017). Social bots: Human-like by means of human control? Big Data, 5(4), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2017.0044

- Guess, A. M., Barberá, P., Munzert, S., & Yang, J. (2021). The consequences of online partisan media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(14), e2013464118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2013464118

- Hacker, J. S., & Pierson, P. (2020). Let them eat Tweets: How the right rules in an age of extreme inequality. Liveright Publishing.

- Hartleb, F. (2013). Anti-elitist cyber parties?: Understanding the future of European political parties. Journal of Public Affairs, 13(4), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1480

- Heaney, M., & Rojas, F. (2015). Party in the street: The antiwar movement and the Democratic Party after 9/11. CUP.

- Hendriks, F. (2021). Unravelling the new plebiscitary democracy: Towards a research agenda. Government and Opposition, 56(4), 615–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.4

- Hopkin, J., & Paolucci, C. (1999). The business firm model of party organisation: Cases from Spain and Italy. European Journal of Political Research, 35(3), 307–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00451

- Ignazi, P. (2020). The four knights of intra-party democracy: A rescue for party delegitimation. Party Politics, 26(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818754599

- Karpf, D. (2017). Analytic activism. Digital listening and the new political strategy. OUP.

- Katz, R., & Mair, P. (1993). The evolution of party organizations in Europe: The three faces of party organization. American Review of Politics, 14(4), 593–617.

- Katz, R. S. (2002). The internal life of parties. In K. R. Luther, & F. Muller-Rommel (Eds.), Political parties in the New Europe (pp. 87–118). OUP.

- Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (2009). The cartel party thesis: A restatement. Perspectives on Politics, 7(4), 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709991782

- Kioupkiolis, A., & Pérez, F. S. (2019). Reflexive technopopulism: Podemos and the search for a new left-wing hegemony. European Political Science, 18(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0140-9

- Kitschelt, H. (2006). Movement parties. In handbook of party politics, edited by R. Katz and W. Crotty (pp. 278–290). London: SAGE Publications.

- Kreiss, D. (2016). Prototype politics: Technology-intensive campaigning and the data of democracy. OUP.

- Kriesi, H. (2014). The populist challenge. West European Politics, 37(2), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.887879

- Lalancette, M., & Raynauld, V. (2019). The power of political image: Justin trudeau, Instagram, and celebrity politics. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(7), 888–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217744838

- Lobera, J., & Portos, M. (2021). Decentralizing electoral campaigns? New-old parties, grassroots and digital activism. Information, Communication and Society, 24(10), 1419–1440. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1749697

- Macwilliams, M. C. (2016). Who decides when the party doesn’t? Authoritarian voters and the rise of Donald Trump. PS: Political Science and Politics, 49(4), 716–721. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096516001463

- McAdam, D., & Tarrow, S. (2010). Ballots and barricades: On the reciprocal relationship between elections and social movements. Perspectives on Politics, 8(2), 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592710001234

- Otjes, S. (2020). All on the same boat? Voting for pirate parties in comparative perspective. Politics, 40(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395719833274

- Paulin, A. (2020). An overview of ten years of liquid democracy research.

- Peña, A. M. (2021). Activist parties and hybrid party behaviours: A typological reassessment of partisan mobilisation. Political Studies Review, 19(4), 637–655.

- Penney, J. (2017). Social media and citizen participation in ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ electoral promotion: A structural analysis of the 2016 Bernie Sanders Digital Campaign. Journal of Communication, 67(3), 402–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12300

- Poguntke, T., Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P. D., Allern, E., Aylott, N., Bardi, L., Costa-Lobo, M., Cross, W. P., Deschouwer, K., Eneydi, Z., Fabre, E., Farrell, D., Gauja, A., Kopeký, P., Koole, R., Verge Mestre, T., Müller, W., Pedersen, K., Rahat, G., … van Haute, E. (2016). Party rules, party resources and the politics of parliamentary democracies. Party Politics, 22(6), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068816662493

- Roemmele, A., & Gibson, R. (2020). Scientific and subversive: The two faces of the fourth era of political campaigning. New Media & Society, 22(4), 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819893979

- Scarrow, S. (2015). Beyond party members: Changing approaches to partisan mobilization. OUP.

- Street, J. (2019). What is donald trump? Forms of ‘celebrity’ in celebrity politics. Political Studies Review, 17(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918772995

- Vaccari, C., Chadwick, A., & O’Loughlin, B. (2015). Dual screening the political: Media events, social media, and citizen engagement. Journal of Communication, 65(6), 1041–1061. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12187

- Vaccari, C., & Valeriani, A. (2016). Party campaigners or citizen campaigners? How social media deepen and broaden party-related engagement. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(3), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216642152

- Vaccari, C., & Valeriani, A. (2018). Dual screening, public service broadcasting, and political participation in eight western democracies. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(3), 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218779170

- van Biezen, I. (2000). On the internal balance of party power: Party organizations in new democracies. Party Politics, 6(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068800006004001

- Vittori, D. (2020). Membership and members’ participation in new digital parties: Bring back the people? Comparative European Politics, 18(4), 609–629. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00201-5

- Wang, D., Piazza, A., & Soule, S. A. (2018). Boundary-spanning in social movements: Antecedents and outcomes. Annual Review of Sociology, 44(1), 167–187. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041258

- Wood, M., Corbett, J., & Flinders, M. (2016). Just like us: Everyday celebrity politicians and the pursuit of popularity in an age of anti-politics. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(3), 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148116632182