ABSTRACT

Evidence-based practice (EBP) has been launched, spread, and established in social work in Sweden in the last decade. Today, impact studies and ‘what works’ are the recommended approaches, and medical ways to understand and examine social problems thus are prioritised over the broad social science perspectives on which social work rests. This development has culminated in an institutionalised system called ‘state governing of knowledge’. We analyse the Swedish EBP movement as an ‘epistemic community’, directing our attention to the ways in which evidence is constructed and proclaimed valid for policy and practice. Empirically, we build on documents from various actors involved in EBP in social work and on results from our on-going research on documentary practices in the social services. We identify four strategies that key actors use within the Swedish EBP community to contest, redefine, and constrain the academic knowledge base of social work: efforts to (1) construct a (state) knowledge bureaucracy, (2) standardise social work research, (3) exclude important aspects of social work expertise, and (4) govern social work practice. All four strategies are supported by ‘improvement rhetoric’ that aims at justifying the project.

ABSTRAKT

Evidensbaserad praktik (EBP) har lanserats, spridits och etablerats i socialt arbete i Sverige under det senaste decenniet. Idag är effektstudier högt värderade och “what works” förekommer som honnörsord inom offentlig förvaltning. Denna typ av medicinska sätt att förstå och undersöka sociala problem prioriteras framför de breda samhällsvetenskapliga perspektiv som socialt arbete vilar på. Utvecklingen har kulminerat i ett institutionaliserat system som kallas statlig kunskapsstyrning. Vi analyserar den svenska EBP-rörelsen som en “epistemisk gemenskap”, och riktar vår uppmärksamhet mot hur evidens konstrueras och lanseras som primär måttstock för praktik och policyarbete. Vår empiri består av dokument från olika aktörer som är involverade i EBP inom socialt arbete och på resultat från vår pågående forskning om dokumenteringspraktiker i socialtjänsten. Vi identifierar och analyserar fyra strategier som används av nyckelaktörer inom den svenska EBP-gemenskapen för att utmana, omdefiniera och begränsa den akademiska kunskapsbasen för socialt arbete: ambitionen att 1) konstruera en (statlig) kunskapsbyråkrati, 2) standardisera socialt arbete, 3) bortse från viktiga aspekter av expertis inom socialt arbete, och 4) reglera socialt arbete. Alla fyra strategier stöds av en förbättringsretorik som syftar till att rättfärdiga EBP-projektet.

Introduction

The shift from a welfare focus to a health focus for many problems that were previously defined as social in nature is a distinct trend with profound effects on social work practice and research. Medicalisation and individualisation processes have led to the prioritisation of medical ways of understanding and studying conditions such as abuse, criminality, or mental illness (Conrad & Schneider, Citation1992), at the expense of the broad social science perspectives on which social work rests. A parallel trend is the introduction of New Public Management – a set of doctrines of which one is to evaluate and measure performance and to make public service providers accountable (e.g. Hood, Citation1991; Hood & Heald, Citation2006; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011; Power, Citation1997). In Sweden, this development has been accompanied by various reforms and the establishment of a National Council of Governing of Knowledge to ensure a so-called evidence-based practice (EBP) in health care and social work. Despite differences between the fields, the original definition of evidence-based medicine (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, Citation1996) is also referred to as the guiding star for evidence-based social work: ‘ … integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research’ (SOU, Citation2008, p. 22). Drawing on the Swedish case, we will raise and discuss several questions about how knowledge is valued, recognised and mobilised when the policy process is driven by bureaucracy with strong public funding rather than by the academy.

The policy-driven phenomenon that we discuss in this text was initially called ‘State governing of knowledge’ [in Swedish: statlig kunskapsstyrning] by the Swedish authorities. The term certainly evokes unhappy associations (such as perhaps Stalinist policies), which might be the reason for the sudden name change to ‘The Council for Governing with Knowledge’. Nevertheless, it is a matter of well-thought-out strategies for implementing EBP in health care (Hasselbladh & Bejerot, Citation2007) and social services, backed by a strong administrative apparatus (Jacobsson, Lappalainen, & Meeuwisse, Citation2017). The initiative mainly derives from The National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW), whose task is to monitor and control health care and social services. We will try to disentangle and illustrate these strategies as they are enacted in the field of social work.

In Sweden, state governing of knowledge is part of an expansive policy with extensive claims. The authorities strive to spread evidence-based practices throughout most welfare areas, such as health care, social services, and education. The term ‘evidence’ is not used to describe just any type of knowledge but rather a very specific kind. It relies upon a positivistic philosophy of science within which the quantifiable has a superior value and where the gold standard is represented by randomised controlled trials and meta-studies of such research. The often-repeated catchphrases ‘what works’ and ‘best practice’ sum up the ambition to convert the results of these meta-studies into clinical guidelines. Such guidelines are expected to improve the quality of services and make decisions and working methods transparent to all. In comparison with many other countries, the Swedish programme of evidence-based social work has been ‘radical’ in the sense that it almost exclusively focuses on the effects of specific treatment and assessment instruments of various kinds (Bergmark, Bergmark, & Lundström, Citation2011).

Harlow, Berg, Barry, and Chandler (Citation2013), among others, point out how EBP and the reconfiguration of social work (in Sweden and the United Kingdom) are connected to the current trends of neoliberalism and managerialism, promoting efficiency and effectiveness in the delivery of social care. Clarke (Citation2004) argues that neoliberal ideas are implemented through the ‘organizational glue’ of managerialism where techniques of scrutiny such as audit and performance management facilitate the exercise of management from a distance. These means serve to fulfil the objective of removing politics from policy by replacing political aspects with seemingly neutral scientific techniques. Similar Foucauldian arguments are put forward by, for example, Kurunmäki and Miller (Citation2006), who talk about the ‘Modernising Government Agenda’, and by Ozga (Citation2008, p. 266) who uses the term ‘The Governance Turn’. In order to ‘govern at a distance’ (Rose & Miller, Citation2010), an array of sophisticated instruments is produced for the steering of policy, says Ozga (Citation2008), obscuring power relations in the disguise of ‘science’. Consequently, governance shades into governmentality (Rose, O'Malley, & Valverde, Citation2006).

In line with many other Swedish researchers in social work (e.g. Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2006; Hertz, Citation2014; Hydén, Citation2008; Topor, Citation2010), we fear that important knowledge in social work will be lost with an overly unilateral emphasis on ‘evidence-based practice’. We are concerned about the almost imperialistic stance taken by EBP proponents and disturbed by their attacks on social work research, practice, and education. It should be noted that the Swedish evidence movement could be – and has been – interpreted in a different way. In contrast to our description of a forceful and strategic promotion of EBP, it has been compared to an enlightenment project with a slow start, where practitioners’ reluctance and academic disbelief were to be overcome. Eventually, the story goes, small victories in turning sceptics have become more frequent, thus explaining the growing success of implementing EBP (e.g. Sundell, Soydan, Tengvald, & Anttila, Citation2010; Svanevie, Citation2011). Rather than interpreting EBP as the result of good or bad implementation, we will seek to determine how the new knowledge system is designed, what knowledge is lost in the process, and with what consequences. We especially focus on the strategies and rhetoric employed by key actors within the Swedish evidence movement in social work. How is the ‘EBP package’ constructed as the most valid, relevant, and robust source of knowledge for social work? What knowledge and perspectives are at risk of being constrained and with what consequences for social work research and practice?

Theory and methodology

Departing from a social constructionist perspective and a related methodological stance, we ignore the taken-for-granted value of ‘evidence’ (e.g. Atkinson & Gregory, Citation2008). We direct our attention to the ways in which such evidence is constructed and proclaimed valid for policy and practice (cf. Morrell, Citation2008). When so-called meta-analyses of systematic reviews are presented as offering generalisable evidence of ‘what works’, the underlying conditions, assumptions, and interpretations are erased or appear to be self-evident. From our position, however, we understand expertise and evidence as socially embedded in power relations and cultural contexts of struggle for political and epistemic authority (cf. Strassheim & Kettunen, Citation2014, among others). In line with Timmermans and Berg (Citation2003), who studied the standards of evidence-based medicine, we argue that evidence-based social work is in itself a series of constructions. The meanings of evidence are never self-evident but instead always dependent on convention, interpretation and socially organised action (cf. Atkinson & Gregory, Citation2008).

It has been suggested that influential interest groups define the meaning of evidence in EBP and have the character of an ‘epistemic community’ (Morrell, Citation2008). Haas (Citation1992, p. 3) defines epistemic community as ‘of a network professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area’. The Swedish network of professionals that we identify as an EBP epistemic community is composed of both researchers and civil servants. In the inner circle, we find a few researchers, some with academic roots in psychology. For several years, this rather small research community has been tightly linked to central bureaucracy, particularly the National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW), through collaboration, various assignments and commissioned work. This closeness to state authorities has given them opportunities to build and refine networks, and has created a direct link to significant civil servants. Thereby a small number of likeminded researchers have become very influential in policy making. In return, this group of scholars provide scientific legitimacy to the authorities. Although their research is not markedly prominent within the discipline of social work (nor other social sciences), their elaborated contacts with international networks within the elite of the global evidence movement (e.g. Campbell Collaboration) provide them with a nimbus of scientific excellency.

Members of an epistemic community are tied together by their shared belief or faith in the truth and the applicability of particular forms of knowledge (Haas, Citation1992). They are allied based on four unifying characteristics: (i) a shared set of normative and principled beliefs that provide a value-based rationale for the social action of community members; (ii) shared causal beliefs that serve as the basis for explaining the linkages between possible policy actions and desired outcomes; (iii) shared notions of validity, i.e. internally defined criteria for weighing and validating knowledge in the domain of their expertise; and (iv) a common policy enterprise to which their professional competence is directed, presumably out of the conviction that human welfare will be enhanced as a consequence (Haas, Citation1992).

We analyse the key actors in the Swedish EBP movement as an epistemic community in this sense, and our material for analysis consists of various sources. We have critically scrutinised governmental reports and documents from various actors involved in EBP in social work, surveys conducted by the authorities to implement such reforms, and statements on EBP published in popular science magazines and scientific journals and on government websites.Footnote1 We have focused especially on EBP activities over the past decade when the project seems to have reached an expansion phase, on the verge of consolidation. This material, mainly launched by the state, displays an unanimous and unilateral perspective on EBP, less nuanced than what seems to be the case internationally. The academic work on EBP – both by its proponents and critics – is also richer in perspectives, putting forward a variety of arguments and ways of reasoning. Even though many sceptic voices are raised against EBP, they are diverse and lack a common policy agenda. In this sense, they do not form an epistemic community as defined by Haas (Citation1992).

We have discerned four strategies employed by key actors within the Swedish EBP community that contest, redefine and constrain the academic knowledge base of social work research and practice: (1) constructing a (state) knowledge bureaucracy, (2) standardising social work research, (3) excluding important aspects of social work expertise, and (4) governing social work practice. Obviously, the different strategies intertwine and overlap and are not as isolated in practice as we suggest here. In addition, all four strategies are permeated and supported by an unquestioned belief in rationality and perfectibility, visible in the justifying rhetoric that describes the project (cf. Best, Citation2006).

Constructing a (state) knowledge bureaucracy

How then is the ‘national governing of knowledge’ policy defined and carried out and how did it come about? It can be described as a political and administrative application of the evidence-based medicine that began to emerge in the US in the mid-1980s (Fernler, Citation2011), and that was implemented in Swedish health care in the 1990s (Hasselbladh & Bejerot, Citation2007). The expansion of the evidence movement to new countries and new fields of practice – not only social work but also, for instance, education and management studies (e.g. Learmonth & Harding, Citation2006) – has been paralleled by demands for rational governance. As in many other countries in the West, the overall idea in the Swedish project has been to subsume ‘curing and caring’ under the same roof in terms of organisation, management, and resource allocation (see, e.g. Kurunmäki & Miller, Citation2006). The original governmental quest for evidence-based practice in social work was vague and ambiguous, opening up for interpretations (Denvall & Johansson, Citation2012). As we will see, the vague EBP project has subsequently been specified, for instance regarding rhetorical claims and key actors.

Rhetorical work

The construct comprehensive governing of knowledge for healthcare and social services’ was outlined in a Swedish governmental report from 2014 (Ds, Citation2014, p. 9). It contains not only descriptions of organisational changes, but also convincing arguments and testimonies of the superiority of EBP. A thorough rhetorical analysis would need far more space than is allowed here, but to give a few examples, let us consider the definition of ‘governing of knowledge’ in the above-mentioned report:

… a system that aims to increasingly provide an evidence-based practice in order to disseminate quality-guaranteed knowledge to be applied in different public sectors, whereas non-evidence-based or harmful practices are weeded out. (Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Ds, Citation2014:9, p. 51; our translation)

EBP proponents tend to be over-explicit rather than subtle in their rhetoric, for example by using metaphorical language. In one journal article, Swedish key actors belonging to the epistemic EBP community describe their general ambition as a ‘mission’:

… to pull social work practice out of the world of opinions and untested knowledge and introduce it into the world of evidence and awareness about what works and what is potentially harmful in social work interventions. (Sundell et al., Citation2010, p. 714)

A current discourse in social work on ‘the user perspective’ is furthermore picked up emphasising both patient and service user rights to information about ‘what works’ (e.g. Gambrill, Citation2001; SOU, Citation2008:18). Originally, this was referred to as ‘the consumer perspective’ within evidence-based medicine (cf. the patient’s choice; Sackett et al., Citation1996), based on mainly economic arguments (Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2006).

Key actors

In Sweden, the EBP reform has not been driven by requests from social work professionals, nor scholars in social work (Bergmark et al., Citation2011). Although there are exceptions, many have been sceptical about the EBP project. Instead, actors in the central bureaucracy have been the prime movers seeking support among significant authorities and stakeholders at different governmental levels (see Pearce & Raman, Citation2014, for similar processes in the UK). Since the 1990s, a stepwise reorganisation of government agencies has been part of a rational planning process at the highest level of government, which reached its goal with the establishment of the National Council of Governing of Knowledge. The process was directed by official reports (particularly SOU, Citation2012:33), with the aim of bringing order in the health and care systems regarding accountability, effectiveness, and knowledge management. A series of key actors were driving forces and building blocks in this construction. shows the authorities that have assumed a key responsibility for development towards evidence-based social work.

Table 1. Key actors.

The National Council for Governing of Knowledge includes, among others, authorities such as NBHW and Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment (SBU). It also includes the research council Forte, which for many years has funded research conducted in social work. The designated task of the research council is to ‘create a bridge between the research community and the authorities’ (Ds, Citation2014:9, p. 7). The municipalities (where social services are located in Sweden) are represented by SALAR in an advisory body (called ‘the group of principals’). The National Board of Health and Welfare has a key role in this construction: its director-general is chairman of both the Council and the advisory body. Furthermore, NBHW has established close contacts with international networks within the evidence movement, for example as co-founders and co-financers of the Campbell Collaboration (Sundell et al., Citation2010).

Another important key actor for the EBP community is SBU. On their web page and in various brochures, SBU presents itself as an independent, objective authority with the qualifications to determine ‘what works’ in health care and social services. Under the headline ‘Our mission’, SBU’s claims are far-reaching:

Which treatment is the best? How to diagnose in the best possible way? How to use resources to the greatest possible benefit? SBU provides reliable answers to such questions. We are an independent state authority, commissioned by the government to evaluate health care methods from an integrated medical, economic, ethical, and social perspective.Footnote2 (our translation)

Furthermore, in a report to the government, SBU (Citation2015) expressed the request that it should also be able to ‘order’ research based on needs that they identify:

The perception of what is important may differ between researchers and users. If research is directed too unilaterally from the perspective of researchers and private financiers, there is a risk that not enough attention is paid to what users think is important. (SBU, Citation2015, p. 15, our transl.)

Undoubtedly, SBU is a central policy-making actor in an influential power structure. With a seemingly apolitical and objective agenda, the new knowledge bureaucracy is designed to have a say in the whole research process, affecting what questions can be asked, what knowledge can be produced and what counts as (scientific) knowledge.

Standardising social work research

SBU’s mission is not restricted to finding out ‘what works’ for patients and clients; it also points social work research in a certain direction: towards more impact and outcome studies. In a popular science magazine issued by SBU, it is implied that academia gives priority to the wrong type of research (SBU, Citation2016, pp. 2–3; see also Socialstyrelsen, Citation2010). A group of Swedish scholars who are closely affiliated with the authorities repeatedly claim that there is a shortage of impact evaluations in social work. Olsson and Sundell (Citation2016), for example, reported that 13% of 2334 dissertations from seven different disciplines (criminology, psychiatry, psychology, social work, sociology, public health, and health care sciences) aimed to investigate the effects of various interventions. The authors regard this figure to be alarmingly low, describing it as a danger to the evidence project. (From another perspective, it also could be seen as a reasonable, perhaps even high figure, given the vast field of inquiry within each and every discipline in question). SBU has further turned to the social work departments at Swedish universities, offering a 2-day course to teach academics to conduct a systematic review in the EBP-stipulated way. The academic tradition of reviewing relevant literature in research projects is deemed inappropriate.

SBU carries out its systematic research reviews according to a certain model and with the help of a handbook that prescribes in detail how reviews of scientific literature should be conducted in a reliable and systematic way (SBU, Citation2014). The evaluations are made by experts in the given field, with support from SBU’s office. The experts are guided step by step by a number of assessment templates with questions to be asked of all articles that may or may not be included in the final review. Systematic reviewing is a genre in itself that involves a reductionist method of rejecting studies with a ‘low degree of evidence’. For example, the number of included studies can be boiled down to a fraction of the original database search, as Topor (Citation2010) noted when examining the sampling process for one such review: of almost 2000 hits, less than 2% of the studies qualified for inclusion.

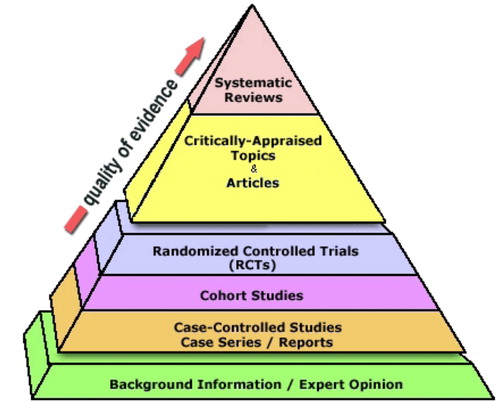

The superiority of the systematic review is illustrated in numerous models, often in pyramid form, and it is apparent that most research within Swedish social work is deemed inadequate according to the EBP yardstick:

http://cairns.health.qld.libguides.com/searching-evidence/levelsevidence. Copyright 2006-2011. Trustees of Dartmouth College and Yale University. All Rights Reserved. Produced by Jan Glover, David Izzo, Karen Odato and Lei Wang.

For obvious reasons, the lion’s share of all systematic reviews that SBU has conducted so far has consisted of compilations of quantitative studies. Some efforts have gone into developing manuals for systematic analysis of qualitative research, but most of it seems to revolve around attempts to squeeze the unruly qualitative material into templates for quantitative assessment. The reviews thus also lean on a quantitative logic and mostly concern patient or client experiences of certain aspects of various interventions. It is thus likely that qualitative studies are either not included at all or that their specific contributions are simplified or destroyed in the process.

Excluding social work expertise

In the previous section, we discussed the limiting definitions of social work research imposed by the SBU. What remains is a bluntly carved out research practice: the study of (i) interventions, influenced by (ii) a medical perspective carried out with (iii) specific scientific methods. The recruitment of experts for conducting systematic reviews is guided by the same narrow definition. This delimitation was reflected in a questionnaire that was distributed by SBU to all professors and associate professors of social work in Sweden. The heading was, ‘What is your expertise in the social service area?’ The agency wanted to take stock of the expertise for future work with systematic reviews. The questions were exclusively formulated around a specific ‘intervention’ (e.g. method ABC, DEF, or GHI) for a defined ‘target’ (e.g. families of patients with dementia, clients with substance use disorders, etc.). Completing the questionnaire made clear that none of our department’s eight professors in social work possessed any expertise in the social service area. Not even colleagues who clearly defined themselves as experts in child welfare, addiction, or aging research could claim expertise because of the narrow definitions of ‘intervention’.

SBU’s restricted inventory of academic experts in the social services inevitably results in a very small group of available experts to be contracted for SBU service (e.g. to conduct systematic reviews or meta-analyses of such reviews). By narrowing down the selection of experts to those belonging to the same field of science, or more specifically, those who share the assumptions underpinning the EBP movement, SBU representatives manage in a circular exercise to exclude all perspectives other than their own. This practice is reasonable when no differences in opinion are desired or even expected. Furthermore, the expert groups put together by SBU will inevitably be coloured by a sort of intellectual conflict of interest because participants are selected beforehand just because they share the same assumptions and celebrate the EBP yardstick. Such intellectual conflict of interest is particularly serious when it comes to the allocation of scarce funding (cf., Björkstén & Graninger, Citation2008).

A similar process of distilling expertise is visible in the selection of ‘consensus panels’ that are staged when no or weak evidence is found for a particular intervention. A panel of experts is gathered to share experiences of a working method and subsequently agree on best practice. In a report from National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2014), access to experts for consensus panels was investigated through a survey administered to both professors and experienced social workers. Social workers’ answers to the question of whether they had ‘particular experience of one or more specific working methods within the area’ revealed that they gave a considerably wider meaning to ‘working methods’ than do authorities. The author of the report describes that some of the social workers even had difficulties naming a precise working method (e.g. Addiction Severity Index or Adolescent Drug Abuse Diagnosis), and instead they stated ‘institution for treatment’, ‘institutional assessments of families’, or simply ‘don’t understand the question’ (p. 23). This result is noteworthy. To these social workers, it is likely that social work in terms of, for example, providing care and support to youngsters at an institution, is viewed as an intervention per se. From the point of view of the EBP community, such a broad definition of an intervention is unthinkable. An intervention is not an intervention if it is not packed and parcelled as a distinct insertion of X that can cause effect Y (cf., Jensen & Vembye, Citation2017).

Governing social work practice

Measuring social work requires clear definitions, simplicity, and documentation, leaving distinctive marks on how social work is to be performed. As in many other countries, the standardisation trend has grown stronger in Swedish social work and is visible in an increasing reliance on manuals and various assessment tools (see, for example, Björk, Citation2016; Harlow et al., Citation2013; Martinell Barfoed & Jacobsson, Citation2012). Whereas an optimistic view predicts increased professionalism through standardised social work (e.g. Jergeby, Citation2008), the more pessimistic view expects the work to be overly controlled by manuals, triggering a de-professionalisation (e.g. Ponnert & Svensson, Citation2016). Regardless of whether there is more or less professionalism, social work interventions that are not properly packaged – e.g. preventive work that is neither manual-based nor named to signal an association with evidence-based methods – obviously runs the risk of being deselected, despite appreciation among both clients and professionals (Jacobsson & Martinell Barfoed, Citation2016, pp. 322–323).

What do we learn from empirical research in fields of social work where standardised practice is widespread? Our own observational studies within the social services show that the (large) number of instruments, plans, and methods make it likely that technical and procedural issues will overshadow the client-oriented purpose of these instruments, plans, and methods (Jacobsson & Martinell Barfoed, Citation2016). Manual-based social work is immersive: software is to be handled, computers repaired, rules followed and double checked with colleagues, checklists ticked off, etc. According to Björk (Citation2016), standardised instruments come with a laboratory logic that conflicts with the logic of care. Wampold and colleagues have convincingly shown that psychotherapy is a socially situated practice where interpersonal processes are critical to its success (Kim, Wampold, & Bolt, Citation2006; Wampold, Citation2001). Most likely, the same applies to social work. For example, parents with experience in childcare investigations seem to care more or as much about the person and personal chemistry than the method (Jacobsson & Martinell Barfoed, forthcoming). Even when concrete methods are discussed, the professional is emphasised as a person, as when a mother during an interview talks about the Marte Meo intervention as ‘Thomas’ (i.e. the professional who implemented the method). How do you know if it is the Marte Meo method or Thomas in person who gives the desired effect? Do you even need to know?

The goal of turning the results of meta studies into guidelines for practice makes it particularly important to scrutinise the evidence base for these guidelines. In contrast to the EBP community, critics from various disciplines are less certain about the validity and merits of the EBP methodology. Jensen and Vembye (Citation2017), for instance, put the EBP causal logic to the test from the perspective of philosophy of causation, examining almost 1500 causal claims in six Danish systematic reviews on the field of education. They found that the principal logic behind these reviews makes ‘ … a radical break with all recent theories of causation, because contextual factors around the causes and effects are washed away in the inferred causal claims’ (Jensen & Vembye, Citation2017, p. 1). Given this weakness, the authors claim, it will not be clear what works for whom, in what circumstances and how. Thus, the mere translation from systematic reviews into guidelines is a complicated process with several pitfalls that may lead to erroneous deduction (e.g. Bergmark, Citation2007). In addition, despite a clearly recommended intervention, the professional is the one to decide whether it applies to a particular case or situation. This interpretative aspect of guidelines and decision-making is under-acknowledged by the EBP community, claims medical researcher Greenhalgh (Citation2012). Similar arguments have been raised from scholars in social work (e.g. Björk, Citation2016).

The ideal of evidence-based social work has managed to gain a strong foothold in Sweden despite criticism because it is built as a well-funded, state-owned bureaucratic project with clear directions for both practitioners and researchers. Another reason is the difficulty to establish lasting forms of cooperation between universities and social workers in the field, especially as there are little opportunities for Swedish social workers to engage in further academic education as part of their employment. To many employers it seems more crucial that the staff attends a 3-day course in the XYZ method or a 2-day training in the ABC form. Some perceive social work education as insufficient preparation for practical work (Engelmark, Citation2013). There have also been proposals for radically shortened social work education due to staff shortages within the Swedish social services. Such a concentrated education would most likely give priority to skills in standardised social work, at the expense of a broader education in social sciences.

Conclusion

In Sweden, the evidence project has revived a battle about the object of knowledge of social work. It stems from a tension that has always existed but where the balance of forces has varied over time. Brante (Citation2003) discussed this battle in terms of the different logics of Academia and the (neoliberal) Welfare State. According to Academia, the object of knowledge is broadly defined as social problems and the purpose is to understand and explain social problems with the help of theories of social science. According to the Welfare logic, the object of knowledge is much more narrowly defined as the relationship between the professional and the client with the aim to evaluate the most effective interventions. From each of these different views of what counts as valid knowledge, it is difficult to accept the other’s arguments. Brante (Citation2003) was right when he feared that the Welfare logic would be given priority at the expense of the other.

Key figures within the state bureaucracy have persistently and step by step launched, distributed and established a bureaucratic version of evidence-based social work in Sweden. We have described the main strategies of this reform work, aimed at breaking resistance among practitioners, challenging current social work research, and drawing more funding to activities connected to their task. The efforts to implement evidence-based social work are also characterised by a certain improvement rhetoric that justifies the project and denigrates present-day social work and social work research.

What conclusions can be drawn regarding the efforts to shape or, from a more sceptical perspective, tame social work research into a discipline preoccupied with ‘interventions’, ‘outcomes’ and the causal link between them? First of all, EBP lobbyists have taken on the project of spreading methods they claim will produce ‘knowledge that really matters’ (cf., Haas, Citation1992), disregarding differences in epistemological positions. The pursuit of this specific kind of policy-relevant knowledge ignores the academic tradition of honouring debate, difference, and disagreements. The belief that disparity benefits academic creativity and scientific achievements acknowledges the fact that quality can be defined in various ways, and excellence can be the object of intense conflict (Lamont, Citation2009). The EBP community tends to regard all such disputes as obstacles to be overcome (Newman, Citation2017), whereas critics have argued that the whole idea of identifying a best practice for all similar cases rests on a naive assumption about a single truth, ignoring politics and the possibilities of incommensurable ontological and epistemological positions (Stranding, Citation2017).

Second, the EBP community has underestimated the difficulties of transferring EBP into practical social work. In the medical field (with its longer tradition of ‘evidence-based medicine’), standardised guidelines seem to have little effect on actual clinical decision making (McGlynn et al., Citation2003). Doctors use guidelines in their own way and revise them when needed based on their own experiences, using so-called tacit knowledge (Greenhalgh, Citation2012). From the perspective of the EBP community, such practice would be judged incorrect. From another perspective the same practice would be seen as a manifestation of professionalism.

Finally, the rationalistic assumptions underpinning the ideal of evidence-based practice, require ideal conditions stripped of complexity. It is fair to conclude that efforts to eliminate the unpredictable messiness of social work come at a cost: a profound loss of meaning. So far, the Swedish radical version of EBP is more an evidence-based policy than evidence-based practice. We have pointed out a number of inherent problems and difficulties in putting the ideal into practice. It remains to be seen how the field of social work responds to, adjusts to and manages the task.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to professor Rosmari Eliasson-Lappalainen who contributed to this text in the capacity of a wise and initiated discussion partner. Many thanks also to participants at the social work conference in Lund, 2016, who commented an early version and inspired us to develop the analysis further.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Katarina Jacobsson is professor of social work at Lund University, Sweden. With a general interest in qualitative methodology and sociology of knowledge, her current projects deal with documenting practices among human service workers. A selection of previous work includes studies of bribery (‘Accounts of Honesty’ in Deviant Behavior) and medical staff’s use of categories (‘Categories by heart’ in Professions and Professionalism). A text on methodology, ‘Interviewees with an agenda’ (with M Åkerström) is published in Qualitative Research.

Anna Meeuwisse is professor of social work at Lund University, Sweden. Her fields of research include comparative social work, social policy and welfare state change, civil society and transnational social movements. She has co-edited several textbooks in social work in use at various universities in the Scandinavian countries. Recent publications include studies of social workers’ attitudes (e.g. ‘Social workers’ attitudes to privatization in five countries’ in Journal of Social Work) and research on Europeanization of civil society (e.g. Europeanization in Sweden, co-edited with R. Scaramuzzino, in print at Berghahn Books).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* An earlier version of this text in Swedish was published in a festschrift for a colleague. The present text in English, however, has undergone significant rework both theoretically and in terms of content. [Jacobsson, K., Lappalainen, R. E., & Meeuwisse, A. (2017). “Statlig kunskapsstyrning” – en exkluderingsprocess. In B. Andersson, F. Petersson, & A. Skårner (Eds.), Den motspänstiga akademikern (pp. 107–134). Malmö: Egalité]

1 We also draw on results from our research group’s ethnographic studies on documentary practices in health care and social services, where efforts to implement evidence-based social work are followed by a growing burden of paperwork (e.g. Hjärpe, Citation2016; Carlstedt & Jacobsson, Citation2017; Martinell Barfoed, Citation2018).

2 http://www.sbu.se/sv/om-sbu/vart-uppdrag/ (date of access: 171018)

3 http://www.sbu.se/sv/publikationer/kunskapsluckor/ (date of access: 171018).

References

- Atkinson, P., & Gregory, M. (2008). Constructions of medical knowledge. In J. A. Holstein & J. F. Gubrium (Eds.), Handbook in constructionist research (pp. 593–608). New York: SAGE.

- Bergmark, A. (2007). Riktlinjer och den evidensbaserade praktiken: en kritisk granskning av de nationella riktlinjerna för missbrukarvård i Sverige. Nordisk alkohol- och narkotikatidskrift, 5, 515–525.

- Bergmark, A., Bergmark, Å, & Lundström, T. (2011). Evidensbaserat socialt arbete. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Bergmark, A., & Lundström, T. (2006). Mot en evidensbaserad praktik? Om färdriktningen i socialt arbete. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 2, 99–113.

- Best, J. (2006). Flavor of the month. Why smart people fall for fads. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Björk, A. (2016). Evidence-based practice behand the scenes. How evidence in social work is used and produced (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:900625/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Björkstén, B., & Graninger, G. (2008). Allergi: kampen om en folksjukdom. Stockholm: Atlantis.

- Brante, T. (2003). Konsolideringen av nya vetenskapliga fält – exemplet forskning i socialt arbete. In Socialt arbete. En nationell genomlysning av ämnet. Högskoleverkets rapportserie 2003:16 R (133–196).

- Carlstedt, E., & Jacobsson, K. (2017). Indications of quality or quality as a matter of fact? “open comparisons” within the social work sector. Statsvetenskaplig tidskrift, 119(1), 47–69.

- Clarke, J. (2004). Dissolving the public realm? The logics and limits of neo-liberalism. Journal of Social Policy, 33(1), 27–48. doi: 10.1017/S0047279403007244

- Conrad, P., & Schneider, J. (1992). Deviance and medicalization: From badness to sickness. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Denvall, V., & Johansson, K. (2012). Kejsarens nya kläder – implementering av evidensbaserad praktik i socialt arbete. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 1, 26–45.

- Ds. (2014:9). En samlad kunskapsstyrning för hälso- och sjukvård och socialtjänst. Departementserien. Regeringskansliet: Socialdepartementet.

- Engelmark, L. (2013). Försoning mellan metod och relation?, (Ledare) Socionomen. Retrieved from http://socionomen.nu/reportage/forsoning-mellan-metod-och-relation.

- Fernler, K. (2011). Kunskapsstyrningens praktik – kunskaper, verksamhetsrationaliteter och vikten av organisation. In I. Bohlin & M. Sager (Eds.), Evidensens många ansikten. Evidensbaserad praktik i praktiken (pp. 131–162). Lund: Arkiv.

- Forte. (2015a). Forskning möter samhälle. Fortes underlag till regeringens forskningspolitik inom hälsa, arbetsliv och välfärd 2017–2027. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare.

- Forte. (2015b). Från fokus på innehåll till fokus på nytta. Regeringsuppdraget S2014/4995/SAM. Retrieved from https://forte.se/app/uploads/2015/04/komsam-regeringsuppdrag.pdf.

- Gambrill, E. (2001). Social work: An authority-based profession. Research on Social Work Practice, 11(2), 166–175. doi: 10.1177/104973150101100203

- Greenhalgh, T. (2012). Why do we always end up here? Evidence-based medicine’s conceptual cul-de-sacs and some off-road alternative routes. Journal of Primary Health Care, 4(2), 92–97. doi: 10.1071/HC12092

- Haas, P. (1992). Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization, 46(1), 1–35. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300001442

- Harlow, E., Berg, E., Barry, J., & Chandler, J. (2013). Neoliberalism, managerialism and the reconfiguring of social work in Sweden and the United Kingdom. Organization, 20(4), 534–550. doi: 10.1177/1350508412448222

- Hasselbladh, H., & Bejerot, E. (2007). Webs of knowledge and circuits of communication: Constructing rationalized agency in Swedish health care. Organization, 14(2), 175–200. doi: 10.1177/1350508407074223

- Hertz, M. (2014). Förtroendekrisen mellan Socialstyrelsen och det sociala arbetet fortsätter”, Debatt. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 1, 85–89.

- Hjärpe, T. (2016). Measuring social work. Quantity as quality in the social services. Statsvetenskaplig tidskrift, 119(1), 23–46.

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Hood, C., & Heald, D. (2006). Transparency: The key to better governance? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hydén, M. (2008). Evidence-based social work på svenska – att sammanställa systematiska kunskapsöversikter. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 1, 3–19.

- Jacobsson, K., Lappalainen, R. E., & Meeuwisse, A. (2017). “Statlig kunskapsstyrning” – en exkluderingsprocess. In B. Andersson, F. Petersson, & A. Skårner (Eds.), Den motspänstiga akademikern (pp. 107–134). Malmö: Egalité.

- Jacobsson, K., & Martinell Barfoed, E. (2016). Trender i socialt arbete. In A. Meeuwisse, H. Swärd, S. Sunesson, & M. Knutagård (Eds.), Socialt arbete – en grundbok (pp. 313–330). Stockholm: Natur och Kultur.

- Jacobsson, K., & Martinell Barfoed, E. ((forthcoming)). Socialt arbete på pränt. Malmö: Gleerups.

- Jensen, H. S., & Vembye, M. H. (2017). How the Laws of Education Lie. Manuscript submitted to Nordic Studies in Education.

- Jergeby, U. (Ed.). (2008). Evidensbaserad praktik i socialt arbete. Göteborg: Gothia Förlag.

- Kim, D.-M., Wampold, B. E., & Bolt, D. M. (2006). Therapist effects in psychotherapy: A random-effects modeling of the national institute of mental health treatment of depression collaborative research program data. Psychotherapy Research, 16(2), 161–172. doi:10.1080/ 10503300500264911 doi: 10.1080/10503300500264911

- Kurunmäki, L., & Miller, P. (2006). Modernising government: The calculating self, hybridisation and perforemance measurement. Financial Accountability and Management, 22(1), 87–106. doi: 10.1111/j.0267-4424.2006.00394.x

- Lamont, M. (2009). How professors think. Inside the curious world of academic judgment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Learmonth, M., & Harding, N. (2006). Evidence-based management: The very idea. Public Administration, 84(2), 245–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00001.x

- Martinell Barfoed, E., & & Jacobsson, K. (2012). Moving from ‘gut feeling’ to ‘pure facts’: Launching the ASI interview as part of in-service training for social workers. Nordic Social Work Research, 2(1), 5–20. doi: 10.1080/2156857X.2012.667245

- Martinell Barfoed, E. (2018). From stories to standardised interaction: Changing conversational formats in social work, Nordic Social Work Research. doi: 10.1080/2156857X.2017.1417154

- McGlynn, E. A., Asch, S. M., Adams, J., Keesey, J., Hicks, J., DeCristofaro, A., & Kerr, E. A. (2003). The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615

- Morrell, K. (2008). The narrative of ‘evidence based’ management: A polemic. Journal of Management Studies, 45(3), 613–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00755.x

- Newman, J. (2017). Deconstructing the debate over evidence-based policy. Critical Policy Studies, 11(2), 211–226. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2016.1224724

- Olsson, T. M., & Sundell, K. (2016). Research that guides practice: Outcome research in Swedish PhD theses across seven disciplines 1997-2012. Prevention Science, 17(4), 525–532. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0640-9

- Ozga, J. (2008). Governing knowledge: Research steering and research quality. European Educational Research Journal, 7(3), 261–272. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2008.7.3.261

- Pearce, W., & Raman, S. (2014). The new randomised controlled trials (RCT) movement in public policy: Challenges of epistemic governance. Policy Sciences, 47, 387–402. doi: 10.1007/s11077-014-9208-3

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform. A comparative analysis new public management, governance, and the neo-weberian state (3rd ed). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ponnert, L., & Svensson, K. (2016). Standardisation – the end of professional discretion? European Journal of Social Work, 19(3-4), 586–599. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2015.1074551

- Power, M. (1997). The audit society: Rituals of verification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rose, N., & Miller, P. (2010). Political power beyond the state: Problematics of government. The British Journal of Sociology, 271–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01247.x

- Rose, N., O'Malley, P., & Valverde, M. (2006). Governmentality. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 2, 83–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.2.081805.105900

- Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M. C., Gray, J. A. M., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn't. British Medical Journal, 312(71). doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71.

- SALAR. (2017). Utvecklingen av socialtjänstens kunskapsstyrning. Viktiga delar återstår. Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting. Retrieved from https://skl.se/download/18.47796ff915cac6799e45a7b6/1497862206307/Utveckling_socialtjanstens_kunskapsstyrning_170619.pdf.

- SBU. (2014). Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården. En handbok. Stockholm: Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services.

- SBU. (2015). Kunskapsbehov och vetenskapliga kunskapsluckor. Rapport till Socialdepartementet. Retrieved from http://www.sbu.se/contentassets/48f98e5ec9504a78af65b85bbb4c4e0e/kunskapsbehov-och-kunskapsluckor_sbu_s2014-8929-sam-delvis.pdf.

- SBU. (2016). Medicinsk och social vetenskap & praxis. Information från SBU. 2016: 1, s. 2-3.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2010). Effektutvärderingar i doktorsavhandlingar. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2014). Konsensuspaneler om psykosociala arbetsmetoder. Enkäter till forskare och socialarbetare. Retrieved from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/19345/2014-1-30.pdf.

- SOU. (2008:18). Evidensbaserad praktik inom socialtjänsten– till nytta för brukaren. Stockholm: The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.

- SOU. (2012:33). Gör det enklare! Slutbetänkande av statens vård- och omsorgsutredning. Stockholm: The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.

- Stranding, A. (2017). Evidence-based policymaking and the politics of neoliberal reason: A response to Newman. Critical Policy Studies, 11(2), 227–234. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2017.1304226

- Strassheim, H., & Kettunen, P. (2014). When does evidence-based policy turn into policy-based evidence? Configurations, contexts and mechanisms. Evidence & Policy, 10(2), 259–277. doi: 10.1332/174426514X13990433991320

- Sundell, K., Soydan, H., Tengvald, K., & Anttila, S. (2010). From opinion-based to evidence-based social work: The Swedish case. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(6), 714–722. doi: 10.1177/1049731509347887

- Svanevie, K. (2011). Evidensbaserat socialt arbete. Från idé till praktik (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:455430/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Timmermans, S., & Berg, M. (2003). The gold standard. The challenge of evidence-based medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Topor, A. (2010). Medikaliseringen av det psykosociala fältet. Om en kunskapssammanställning från socialstyrelsen, IMS. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 1, 67–81.

- Wampold, B. E. (2001). Contextualizing psychotherapy as a healing practice: Culture, history, and methods. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 10(2), 69–86.