ABSTRACT

Discussions of and trainings on policy practice in social work often focus on the normative and technical aspects of this type of social work intervention. Discussions do not delve sufficiently into concepts and aspects of politics, such as power, which are staple in the political science discourse. This theoretical article proposes situational, relational, and more individualistic conceptions of power relations that may be utilised in teaching policy practice in social work. The proposed understanding of power relations offers a method of training social work students to become well-prepared policy actors, and focuses on six areas of teaching policy practice: conscious analysis of the context of interaction with other actors; reflection on power differentials; the purposeful development of one’s power differentials; thoughtful work with symbols of power; the selection of appropriate strategies for managing power clash and gaining power; and the new ethical issues connected with the above areas. Social work scholars and educators can utilise the offered conceptual frame for teaching future social work practitioners how to promote changes in particular social work institutional settings.

ABSTRAKT

Diskuse a příprava v politické praxi sociální práce se často zaměřuje na normativní a technické aspekty tohoto typu intervence v sociální práci. Důkladně se nediskutují aspekty politiky a koncepty, které tvoří jádro diskursu politických věd. Příkladem může být koncept moci. Předkládaný teoretický článek nabízí situační, vztahový a více individualizovaný koncept mocenských vztahů, který lze využít ve vzdělávání v politické praxi sociální práce. V textu představené porozumění mocenským vztahům nabízí možný způsob, jak připravit studenty sociální práce jako budoucí kvalitně vybavené aktéry politických změn. Text diskutuje šest oblastí vzdělávání v politické praxi: uvědomělou analýzu kontextu interakce s ostatními aktéry politiky, reflexi rozdílů ve zdrojích moci, cílevědomé budování vlastních zdrojů moci, promyšlené nakládání se symboly moci, volbu vhodných strategií pro zvládání mocenských střetů a získání moci, a nakonec nové etické problémy spojené s předcházejícími oblastmi. Vzdělavatelé v sociální práci mohou využít nabízený konceptuální rámec pro přípravu budoucích sociálních pracovníků jako tvůrců změn ve specifických institucionálních podmínkách sociální práce.

Introduction

Traditionally a domain of the more radical and activistic social workers, the policy aspect of social work has developed significantly over the last two decades, and recently, policy practice has become an increasingly inherent part of mainstream social work; it is evidenced in the following examples: (i) articles and books on policy practice in social work are being published in peer-reviewed journals and prestigious publishing houses; (ii) groups of scholars involved in policy practice have been established; and (iii) social work students are now trained to promote policy changes (in some social work schools). From these sources, we can come to understand why policy practice is important (Figueira-McDonough, Citation1993), what current theoretical base(s) it has (Feldman, Citation2020), what the extent of policy practice is or could be (Colby, Citation2018), and who can make change and how (Ellis, Citation2008).

Although social work education can utilise examples of the exceptional practice of social workers promoting policy changes (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2015; Weiss-Gal & Gal, Citation2020; Weiss-Gal et al., Citation2020; Amann & Kindler, Citation2021; Zogata-Kusz, Citation2022), it still mainly focuses on shaping social workers’ “service provider role” and social work students find themselves unprepared for policy engagement (Woodcock & Dixon, Citation2005; Burzlaff, Citation2020; Apgar & Luquet, Citation2022). Reflecting the development of the social work self-definition (Ornellas et al., Citation2018), it is sufficient for us now to understand that there are widely-shared assumptions about social workers as “social change agents” who struggle for a more just world and question constituted hegemony (Gramsci, Citation2000). The daily fulfilment of the global social work mission (The International Federation of Social Workers/The International Association of Schools of Social Work, Citation2014) is, essentially, a day-to-day counter-hegemony struggle (Fraser, Citation2022). Undoubtedly, the social work political mission is ambitious. To succeed in policy arenas and to encourage social change and development, social work students must be knowledgeable about the power relations of which they will be part. That is why there is a significant need for comprehensive theorising on (i) what power is; (ii) how it arises, flows, and how structures overlap; (iii) how the nature of power relations in institutional settings is shaped; and (iv) how social work education can utilise power for the professional preparation of social work students as future social change agents, future policy actors (Weiss-Gal & Gal, Citation2014; Aviv et al., Citation2021).

This article addresses the question of how can the conceptualisation of power relations be utilised in teaching policy practice in social work? Despite the fact that the paper is a conceptual article, the models of power relations and power clashes are also explained via the empirical examples that the author has inductively gathered during experienced social work practice ( and ); these examples also come from routine life in a locality affected by the expressed event () as well as the practice of the author’s colleague ().

Table 1. The empirical illustration of power relation.

Table 2. The empirical illustration of the bureaucratic clash.

Table 3. The empirical illustration of the institutional clash.

Table 4. The empirical illustration of the ideational clash.

The formation of social work institutional settings

Historical institutionalists explain that human life is embedded in the routinely expected ways of solving or preventing particular human problems, otherwise referred to as institutions (North, Citation1990). Every society creates its institutions: in contemporary societies, we can identify health, education, justice, security, and the like. These are (1) expressed via specific policies formalised within distinct bureaucratic apparatuses (government ministries), and (2) run by Departmental administrators and specialised workers (professionals such as doctors, teachers, lawyers, and police officers). When people, for example, fall ill or are assaulted or threatened, they are able to then find help and support within the scope of these institutions, policies, and professionals. The thus described horizontal institutional structure simplifies the reality. Actually, there are no apparent boundaries among institutional sectors. Institutions and institutional sectors are liquid (Meyer, Citation2019): blurred, overlapping, and variable despite that they are created by formal policies, programmes, ministerial/departmental competencies, and professionals’ roles.

Besides the horizontal structure, we can also delineate the vertical institutional structure as well. The above bureaucratic apparatuses play an essential role here. A pluralist perspective (Dahl, Citation1961) explains the division of bureaucracies via levels when decisions are made and distinguishes between supranational, national, regional, local/municipal, and street levels (Peters, Citation2012). It is known that regional and local levels may have varying degrees of in/dependence on/from the national and central government and its departments (Penninx, Citation2009). In democratic societies, the authority of a central government is partially limited (Peters, Citation2012), and a mixture of social and political actors with diverging interests can formulate, promote, and achieve common objectives (Torfing et al., Citation2012).

Before moving on, we must relate to the need for integration interconnection among the state, private bodies, and NGOs into our conception of institutional settings. The cross-sector organisational structuration is an output of the process called agencification, which is marked by the distribution of the duties of the state to more or less independent organisations or contractual agencies (Pollitt et al., Citation2004). To some degree, for-profit and non-profit organisations and agencies have gained autonomy from the state and governments. Therefore, diverse organisations and agencies create an organisational environment that is integral to particular settings of institutions described above. High officials, authorised representatives, managers, or specialists from the state, organisations, and agencies are important policy actors in specific horizontal and vertical institutional settings.

The just presented three-dimensional institutional structure represents the social work institutional settings. We can summarise that the social work institutional settings are full of complexity, blurred boundaries, overlapping authorities, variable difficulties, and changeable opportunities to influence policy.

Some readers may demur the idea of such complexity. They may say we live in neo-liberal times; thus, the neo-liberal zeitgeist and its hegemony make the social work institutional settings much simpler. I agree that social work as a profession has been continually under attack ideologically, politically, and financially (Garrett, Citation2018). Even in the most generous Nordic welfare states, the effects of neo-liberalism have forced social workers to change the nature of social work practice (Kananen, Citation2014; Marthinsen, Citation2019). However, resistance is possible. Based on past experiences with social work under Colonialism, Nazism, and Communism (Kunstreich, Citation2003; Lorenz, Citation2004; Špiláčková, Citation2014; Ferguson et al., Citation2018), a few social workers (and other professionals) participating in resistances maintained, often informally and at a significant cost, strictly controlled areas of life, including banned social institutions and organisations. Therefore, it is plausible to avoid such a simplification of the social work institutional settings and interpret them in an even more complex manner; this is due to the fact that they include some space for resistance (a counter-hegemonic struggle) in those institutional areas that are more deeply afflicted by the neo-liberal zeitgeist (Strier & Bershtling, Citation2016).

The positioning of social workers

Social workers practice social work in all institutional sectors, levels, and organisations. From the horizontal view, we can find social workers providing their demanding jobs in all institutions and organisations under the influence of various ministerial commands; in organisations such as hospitals, prisons, schools, rest homes, child protection agencies, and diverse state, region, or municipality departments of authorities. From the vertical point of view, social workers are (i) direct deliverers of services to people in need, (ii) administrators of social services, (iii) specialists with precious knowledge, and (iv) policymakers at the municipal, regional, and state level. From the cross-sector organisational view, social workers are mainly employees of public (state, regional, and municipal), non-profit, and for-profit organisations; thus they (i) are subordinated to highly varied organisational missions; (ii) fulfil various tasks dependent on various organisational aims; and (iii) experience diverse organisational cultures that shape their practice.

The three dimensional view on positioning of social workers produces a highly heterogeneous picture of social workers in positions subordinated to diverse institutional and organisational imperatives. Moreover, in varied positions, social workers can changeably either resist or yield to the neo-liberal hegemony (Strier & Bershtling, Citation2016; Feldman, Citation2022; Timor-Shlevin et al., Citation2022; Timor-Shlevin, Citation2022). Again, experience with social work in a totalitarian regime has shown the highly contentious relationship between social work and the nation-state and its prevailing ideology (Lorenz, Citation2004; Ferguson et al., Citation2018). Like many other professionals, such as lawyers, doctors, or teachers, some percentage of the social worker profession opt to follow a regime (un)consciously and become “agents of hegemony”, while others operate as “counter-hegemony agents”. Thus, even in the modern and seemingly nonviolent neo-liberal zeitgeist (Garrett, Citation2018), it is plausible to understand social workers as both (un)conscious agents of the neo-liberal hegemony (providers of neo-liberalised services) and, at the same time, counter-hegemony agents (critical, radical, and activist social workers).

Institutional and organisational imperatives, accompanied by the resistance to or compliance with the neo-liberal hegemony, create miscellaneous expectations connected to social workers’ ability to promote changes, which we understand as social workers’ power.

Power and the dynamics of power relations among policy actors

Power is probably one of the most ambiguous and vague terms in social science. Power is treated differently, and its meaning is changeable. Every field (political science, political philosophy, sociology, economics, or anthropology) and school (elitism, pluralism, Marxism, corporatism, professionalism, technocracy, post-structuralism, and feminist theory) is based on diverse foundations and emphasise various aspects of social and material reality when defining power.

Being focused on the policy practice of social workers, I hold an interactionist view focused on individuals in a particular context. In my understanding, power is an omnipresent element of social reality (Foucault, Citation1990) that determines organisation of social interactions among policy actors in particular institutional settings. Following Latour (Citation1984), Whitehead (Citation2010), and Arendt (Citation2013), whose work on power helps to conceptualise it more individualistically, I am focused on (i) the perception of power differentials such as force, authority, influence, knowledge, or control of resources that leads to (ii) localisation of what has been constructed as “a power of someone” in social interactions. Nonetheless, let me start from the very beginning.

What is power? Power is not an institution, a structure, or the particular strength of an individual; power is not a rule leading to subjugation or a general system of domination (Foucault, Citation1990). It is an omnipresent element of reality that can be found in all social interactions. It is not in macrostructures; rather, it’s spread throughout the social system (Foucault, Citation1980). Even though power has a structural nature, it “is never anything more than a relationship that can, and must, be studied only by looking at the interplay of the terms of the relationship” (Foucault, Citation2006; as cited in Lynch, Citation2014, p. 21). While respecting the structural nature of power, which Foucault (Citation1980) expressed via the composite term power/knowledge, I am focused on an interpersonal level where power manifests itself in relationships among people. In that sense, Arendt (Citation2013) describes power as a ubiquitous power potential that springs up when people interact. In that sense, power is a situational, relational, changeable, and unreliable entity – a potential, potency, or capacity – helping overcame significant obstacles in a particular context. It refers to something that can modify or alter the world through our actions (Popitz, Citation2017); to something that needs to be actualised through interactions among people (Arendt, Citation2013). Power is neither just a chance to enforce our will against the will of others (Weber, Citation1978) nor ascendancy over (i) resources (Dahl, Citation1961), (ii) agendas (Bachrach & Baratz, Citation1970), and (iii) ideational components of reality creation (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016) or interests shaping (Lukes, Citation2005). In compliance with Foucault (Citation1990), I believe that power cannot be possessed. Power is – not permanently – negotiated, given, and taken in social interaction among people.

Power is a situational, relational, changeable, and unreliable potency or capacity of social workers to promote desired changes (or prevent unwanted changes). It is obvious, however, that the concept of power itself is not very helpful in explaining the reality of political competition among actors in the social work institutional structure delineated above. What needs to be done in that matter is to shift our attention to power relations.

Whitehead (Citation2010) conceptualised power relations as a competition among constructions of power based on a perception of power symbols. The other is situationally seen as powerful when (and only when) one acknowledges their potential capacity to do something. In interactions, power is exhibited through particular symbols such as a muscular figure, a gun, a suit, a title or degree, an articulacy, or wealth. Given the uneven distribution of power among actors, power relations are characterised by an asymmetry in the perceived potential capacity among actors. When the other is perceived as powerful, then they become endowed with power. Considering Latour’s work (Citation1984), different manifestations of power (perceived symbols of power) can be added that significantly influence the actual actions of actors; what matters is not what one is really capable of, but instead, what is believed in one’s capacity to do something.

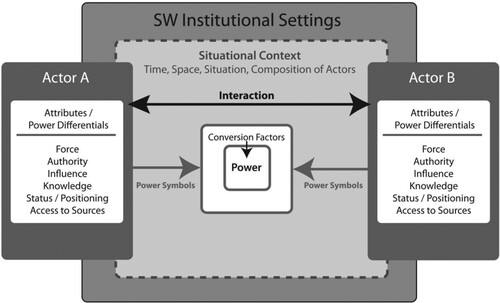

Using above, imagine a situation where actors A and B interact. Each of them carries certain attributes, which we understand here as “power differentials”: they are both physically constituted in some way, hold a certain job position, have a certain education, enjoy a certain authority, earn a certain reputation, and have certain access to resources. They are bearers of two specific configurations of power differentials manifesting themselves through power symbols. As such, both actors perceive the other as specifically powerful. The social work institutional settings and situational context of their interaction contains a specific mix of the so-called “conversion factors” (see Sen, Citation1999, Citation2009), enabling the functioning of a particular combination of power differentials towards a gain of power. It causes, for example, the symbols of actor A can prevail. Consequently, actor B acknowledges actor A’s potential capacity to do something and submit, which is the act of power endowing (see the illustration in ).

Amartya Sen (Citation1999, Citation2000) has described the conversion factors as personal and social aspects of reality, such as characteristics of individuals and social or environmental conditions, which enable the conversion of means into ends in the frame of individuals’ day-to-day functioning. Besides, Sen has differentiated conversion opportunities from factors. Although these very similar aspects of reality directly do not enable the conversion, they create favourable conditions for the potential conversion of means into ends. I utilise Sen’s conception as follows: suppose the conversion factors are present in the context of interaction among actors (see ); specific mixtures of time, space, situation, and compositions of actors with their characteristics produce specific conditions, which are different for each interacting actor. While tempting, one cannot simply label these conditions as conversion factors because of differences between the conversion factor and the opportunity reside in the end – a real power gain, which means having potency or capacity to promote desired changes. Some of these conditions were conversion factors, and others were conversion opportunities for the actor who has successfully promoted desired changes. In contrast, for those actors who have not promoted changes, these conditions were just conversion opportunities or even conversion obstacles.

It is reasonable to consider the described social work institutional settings to be complex, making understanding power relations arrangement very difficult. Besides social workers and social work or social services organisations, many other professions and organisations enter policy arenas, knowledge platforms, inter-professional networks, or teams, and all of them are interested in promoting their ideas. There is no transparent and steady actor A and B competition, but rather multitude of actor A and B power contests – highly situational and changeable interactions among diverse actors from various institutional sectors, levels, and organisations. The power contest among actors can be understood as different kinds of clashes of power differentials through power symbols, which give rise to a particular actor’s power.

Clash of powers: the typology

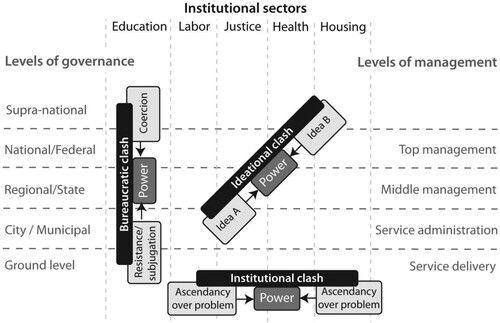

Inspired by Carstensen and Schmidt (Citation2016, Citation2018), I offer three ideal types of power clashes. Dahl’s (Citation1961) conception of power as the control of observable behaviour lays the foundation for thinking about the bureaucratic clash. Schattschneider’s (Citation1960) or Bachrach and Baratz’s (Citation1970) enhancements of the pluralist approach, in which agenda-setting and gatekeeping play an essential role, mark lines of the institutional clash. Finally, Lukes’s third dimension of power (Lukes, Citation2005) and Carstensen and Schmidt (Citation2016) conception of ideational competition offer a suitable basis for defining the ideational clash. I utilise the above knowledge to conceptualise three types of power clashes among policy actors while promoting desired policy changes (see ).

First, the bureaucratic clash among actors is caused by the unbalanced intentional interactions among superior and subordinate actors while governing society or running organisations (Dahl, Citation1961; Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, Citation2018). We suppose various power differentials to be activated during this clash. While the higher positioned actors can use their formal authority, access to resources, and the ability to distribute rewards and punishments (Dahl, Citation1961; Etzioni, Citation1961; Howe, Citation1986), the lower positioned actors, such as social workers, can use their specific knowledge, the complexity of the problems they solve, and the trust of the people they work with (Lipsky, Citation2010; Freidson, Citation1986; Howe, Citation1986). In this clash, interactions among actors take place in terms of top-down and bottom-up competitions resulting in coercion, resistance, or subjugation (see the illustration in ). The notion of the bureaucratic clash has made the possibility of social workers’ resistance more conceivable. In his brilliant study, Howe (Citation1986) illustrated how labyrinthine and uncontrollable frontline work with children at risk has enabled social workers to resist managerial control. Also, more recent research indicates an array of possibilities in our highly neo-liberalised times (Strier & Bershtling, Citation2016; Feldman, Citation2022; Timor-Shlevin et al., Citation2022). Among other things, social workers can use their discretion and operate “under the radar” of ministerial control (Timor-Shlevin & Benjamin, Citation2022, p. 138); they can also focus more on important problematic aspects of peoples’ lives than on prescribed procedures (Timor-Shlevin, Citation2022).

Second, besides coercion, there is dominion over societal problems, which has crystallised along with the routinely expected ways of solving or preventing these problems (the crystallisation of formal and informal institutions). The institutional clash is shaped by the dominion over recognised problems (Meyer, Citation2019). Formal institutional arrangements and the authority of professions (Freidson, Citation1986) and specialists (Hayek, Citation1980) who have proved their ability to solve or prevent a particular recognised problem allow only selected actors to participate in policymaking. As such, mobilisation of bias, agenda-setting, and game-keeping are the main components of institutional power clash (Bachrach & Baratz, Citation1970; Gaventa & Cornwall, Citation2001). In this clash, interactions among actors take place in terms of horizontal cross-institutional competitions (see the illustration in ). The notion of the institutional clash sheds light on social workers’ competition with other professionals and specialists. It is essential to understand that in particular social work institutional settings, institutionalised professional knowledge creates an ascendancy of a professional over a problem. In light of the fact that social workers do not dominate any institutional field but are instead spread throughout the institutional structure, they inevitably compete with, for example, physicians and health professionals in hospitals (Wilson, Citation2020), or tutors and psychologists in prisons (Hubíková et al., Citation2021), while activating their professional knowledge. Moreover, in neo-liberalised services, social workers compete with economists while negotiating for the budget (Timor-Shlevin & Benjamin, Citation2022).

Thirdly, the ideational clash is neither mainly vertical nor horizontal, but is actually demarcated throughout the social work institutional settings (see the illustration in ). The competition among actors is about the mobilisation of myths, symbols, ideologies, and rumours that re-structuralise actors’ interests (Lukes, Citation2005; Gaventa & Cornwall, Citation2001). Moreover, affecting other actors’ casual beliefs (ideas) directly through persuasion or imposition or indirectly by influencing the structuration of thoughts (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, Citation2018) is another crucial account in that matter. In this clash, interactions among actors take place in terms of diagonal competitions among ideas. The notion of the ideational clash uncovers the problem of ideology competition in social work. Bodies of beliefs manifest themselves in ideas of what is a problem, why is important to solve it, who should be involved, where they should operate and how, at what cost, and what are the expected benefits. These are mostly normative questions that produce normative answers. Social work innovations based on counter-hegemony principles such as social justice, human rights, collective responsibility, and respect for diversities (IFSW/IASSW, Citation2014) produce ideas of recognition (Fraser & Honneth, Citation2003; Krumer-Nevo, Citation2020; Timor-Shlevin, Citation2022). These ideas compete with conservative and systemic ideas dominating a field (Chambon, Citation2013) and producing answers influenced by othering (Krumer-Nevo, Citation2020; Timor-Shlevin, Citation2022).

Obviously, all three clashes do not appear separately. In the demanding policy practice of social workers all clashes often come about simultaneously and overlap in various ways. How can we prepare future generations of social workers who will routinely enter policymaking for success in these clashes? If our ambition is to educate future social workers as policy actors, we must radically change social work education. The rationale behind this need is the actual reality of social work education that is ready to prepare professionals who deliver services, but not for those who supposed to be actively involved in policymaking. My suggestions follow the answer to question: how can the conceptualisation of power relations be utilised in teaching policy practice in social work?

Discussion: the suggestions for teaching policy practice in social work

The above understanding of power can be utilised in social work education in several ways; the elements of and above demonstrate this. Educators can increase students’ competencies in the areas of (i) conscious analysis of the context of interaction with other actors; (ii) reflection on power differentials, whether it be one’s own or others’; (iii) the purposeful development of one’s power differentials; (iv) thoughtful work with symbols of power; (v) the selection of appropriate strategies for managing power clash and gaining power; and (vi) the new ethical issues connected with the above areas.

In the following section, I suggest a broad body of scholarship that may be useful for enriching a conceptual foundation that enables in-depth thinking about the policy engagement of social workers. Due to the limited scope of the paper, is impossible to add further references to additional prominent scholars who shape thinking in a particular field, discipline, or theory. Therefore, I offer just general suggestions of where to find suitable conceptual support.

Conscious analysis of the context of interaction with other actors is to analyse the context of the interaction among policy actors; educators neither rely on traditional socio-ecological theories that focus on the role of the environment while social workers work with people in need, nor on the critical theories focusing on social structure in terms of relations between powerful and oppressed. It seems appropriate to use the diverse streams of political science discourse that would imply a suitable addition to social policy, which focus mainly on systems of care, assistance, and support by appropriately selected elements of public policy. In public policy courses, students can gain knowledge about the nature of prevailing ideology and its hegemony, social and institutional structure, political actors, political processes, and changeable relations among these; students can learn how the structure, actors, and processes can be analysed and for what the results of the analyses can be utilised in social work practice. Knowledge of the nature of the context of interaction between actors is essential for understanding the dynamics of power formation; and in particular, knowledge of the specific configurations of time, space, situation, and composition of actors and their positioning is essential.

Reflection on power differentials focuses on an actor’s individual attributes that enable them to acquire power under favourable conditions in a particular context. During their studies, students should acquire the conceptual and analytical equipment to critically reflect on their attributes to acquire power (and those of other actors) in a specific ideological, institutional, and organisational context. Looking at , it is clear that we have encountered significant limitations here, as most of these attributes haven’t been thoroughly conceptualised in social work. The meanings of terms such as authority, influence, or knowledge are vague. Educators can design courses that remove the vagueness of these concepts while creating a framework that encourages critical reflection on specific configurations of power differentials.

Purposeful development of one’s power differentials denotes that in addition to the awareness of power differentials, fostering students’ understanding of their attributes in competition with other actors is also crucial. So, it can be seen that the purposeful development of one’s configuration of power differentials is desirable here. If social workers want to be competitive over a long period in interactions with lawyers, doctors, managers, high officials, and others, then they must systematically develop their power differentials. Education can shape students’ willingness to broaden and deepen their knowledge, nurture their reputation, build formal or informal authority, expand their access to resources, or reflect on their direct or indirect influence on other actors. It is an extension of the concepts of self-care and self-development to the level of policy practice. The day-to-day policy engagement of social workers implies specific demands on the personality of the social worker and their power differentials.

Thoughtful manipulation with power symbols is probably the most important, and likely ethically questionable. Education should prepare students to work consciously with those elements of their professional and personal role that speak to other actors and manifest their potential. In essence, symbol manipulation makes other actors believe that a particular social worker is the bearer of a preferred potential. In education, one can imagine specific courses developing social workers’ (non-)verbal communication in the highly competitive environment of policy practice. Here, existing courses on communication with clients and concepts such as active listening can be appropriately used. However, they need to be expanded to include communication strategies in different types of political negotiations; this is where proved courses in political communication and persuasion come directly into play.

Strategies for managing power clashes and gaining power consider the high complexity of the context of possible interactions with other actors, future social workers will need effective strategies to manage bureaucratic, institutional, and ideological clash in a specific ideological, institutional, and organisational context. Theories of (neo)pluralism and managerialism offer several insights on building a conceptual framework of possible strategies to manage bureaucratic clashes. Theories of (neo)professionalism or inter-professional and inter-organisational theories produce knowledge that enables the formulation of possible strategies for facing institutional clashes. Finally, discursive institutionalism and the diverse range of constructivist theories dealing with agency produce valuable knowledge for designing possible strategies for overcoming ideational clashes. Educators can formulate these possible strategies as certain theoretical assumptions about the course of competition between actors. Moreover, researchers can subsequently test and refine them in a present ideological, institutional, and organisational context, causing students to have validated guidance on how to enter, persist, and succeed in the clashes.

New ethical issues are being addressed through our proposals for social work education, as they indicate a possible rise of several ethical issues of well-elaborated policy practice in social work. Education should reflect this. New ethical problems and dilemmas directly related to a social worker’s political role will need to be described. In particular, the area of the unintended consequences of acquired dominance in bureaucratic, institutional, and ideological clashes or the consequences of wielding gained power. It is essential to consider how easily power could be transformed into various forms of violence. Undoubtedly, future social workers should be aware of their enormous responsibility after gaining power. As powerful, social workers should sensitively recognise the thin red line that separates them from transformation into oppressors. Therefore, careful ethical training of students in political practice is a great challenge for educators.

Conclusion

The article contributes to policy practice discourse by offering a way to consider how social work scholars can enrich a conceptual foundation that enables in-depth thinking about policy engagement by social workers. Moreover, there is a need to prepare students (future social workers) as policy actors routinely engaged in politics and policymaking. In that case, social work scholars and educators should have a suitable conceptual frame for teaching future social work practitioners how to promote changes in particular contexts. The demanding social work political role, a day-to-day counter-hegemony struggle of particular social workers, can be fulfilled if, and only if, social work practitioners routinely use a rich and proper conceptual gear to reach a deep horizon of understanding of how to succeed in a rough political competition in the neo-liberal zeitgeist.

Geolocation information

Brno, Czech Republic, European Union

Acknowledgements

Author would like to thank Professor John Gal for his cordial attitude, precise guidance, and helpful feedback, as well as his dear colleague, Lucie Novotna, for her critical comments in every stage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roman Balaz

Roman Balaz is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Policy and Social Work, Masaryk University, Czech Republic, and a Fulbright Alumni at the Center for the Study of Europe, Boston University, USA. He is interested in policy practice in social work, especially in work with marginalized groups in transition democracies.

References

- Amann, K., & Kindler, T. (2021). Social workers in politics–a qualitative analysis of factors influencing social workers’ decision to run for political office. European Journal of Social Work, 25(4), 655–667.

- Apgar, D., & Luquet, W. (2022). Linking social work licensing exam content to educational competencies: Poor reliability challenges the path to licensure. Research on Social Work Practice, 0(0), 1–10.

- Arendt, H. (2013). The human condition. University of Chicago Press.

- Aviv, I., Gal, J., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2021). Social workers as street-level policy entrepreneurs. Public Administration, 99(3), 454–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12726

- Bachrach, P. & Baratz, M. (1970). Power and poverty: Theory and practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Burzlaff, M. (2020). Policy Practice–Eine Einführung mit Fokus auf Curricula Sozialer Arbeit. In G. Rieger, & J. Wurtzbacher (Eds.), Tatort Sozialarbeitspolitik. Fallbezogene Politiklehre für die Soziale Arbeit (pp. 27–51). Beltz Juventa.

- Carstensen, M. B., & Schmidt, V. A. (2016). Power through, over and in ideas: Conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534

- Carstensen, M. B., & Schmidt, V. A. (2018). Power and changing modes of governance in the euro crisis. Governance, 31(4), 609–624.

- Chambon, A. (2013). Recognising the other, understanding the other: A brief history of social work and otherness. Nordic Social Work Research, 3(2), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2013.835137

- Colby, I. C. (2018). The handbook of policy practice. Oxford University Press.

- Dahl, R. (1961). Who governs? Democracy and power in an American city. Yale University Press.

- Ellis, R. A. (2008). Policy practice. In I. C. Colby (Ed.), Comprehensive handbook of social work and social welfare, social policy and policy practice (pp. 129–143). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Etzioni, A. (1961). A comparative analysis of complex organizations. Free Press.

- Feldman, G. (2020). Making the connection between theories of policy change and policy practice: A new conceptualization. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(4), 1089–1106. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz081

- Feldman, G. (2022). Disruptive social work: Forms, possibilities and tensions. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(2), 759–775. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab045

- Ferguson, I., Ioakimidis, V., & Lavalette, M. (2018). Global social work in a political context: Radical perspectives. Policy Press.

- Figueira-McDonough, J. (1993). Policy practice: The neglected side of social work intervention. Social Work, 38(2), 179–188.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality: An introduction. Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M. (2006). 19. December 1973. In Psychiatric power (pp. 143–171). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fraser, N. (2022). Gender, Race, and Class through the Lens of Labor. Benjamin Lecture 1 [video]. https://criticaltheoryinberlin.de/benjamin_lectures/2022/.

- Fraser, N., & Honneth, A. (2003). Redistribution or recognition? Verso.

- Freidson, E. (1986). Professional powers. A study of the institutionalization of formal knowledge. University of Chicago Press.

- Gal, J., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2015). The 'Why' and the 'How' of policy practice: An eight-country comparison. British Journal of Social Work, 45(4), 1083–1101. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct179

- Garrett, P. M. (2018). Welfare words: Critical social work & social policy. Sage.

- Gaventa, J., & Cornwall, A. (2001). Power and knowledge. In P. Reason, & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Hanbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp. 70–80). Sage Publication.

- Gramsci, A. (2000). The gramsci reader: Selected writings, 1916-1935. NYU Press.

- Hayek, F. A. (1980). Individualism and economic order. University of Chicago Press.

- Howe, D. (1986). Social workers and their practice in welfare bureaucracies. Gower.

- Hubíková, O., Havlíková, J., & Trbola, R. (2021). Social work goals in the context of their weak institutional anchoring. Sociální Práce, 21(5), 5–21.

- The International Federation of Social Workers/The International Association of Schools of Social Work. (2014). The Global definition of Social Work. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/.

- Kananen, J. (2014). The nordic welfare state in three eras: From emancipation to discipline. Ashgate.

- Krumer-Nevo, M. (2020). Radical hope: Poverty-aware practice for social work. Policy Press.

- Kunstreich, T. (2003). Social welfare in nazi Germany. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 14(2), 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J059v14n02_02

- Latour, B. (1984). The powers of association. The Sociological Review, 32(1_suppl), 264–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00115.x

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy, 30th anniversary edition: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lorenz, W. (2004). Towards a European paradigma of social work. Studies in the history of modes of social work and social policy in Europe [Thesis]. Dresden: Technischen Universität Dresden.

- Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A radical view (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lynch, R. A. (2014). Foucault's theory of power. In D. Taylor (Ed.), Michel foucault: Key concepts (pp. 13–26). Routledge.

- Marthinsen, E. (2019). Neoliberal regimes of welfare in scandinavia. In S. A. Webb (Ed.), The routledge handbook of critical social work (pp. 302–311). Routledge.

- Meyer, R. E. (2019). A processual view on institutions. A note from a phenomenological institutional perspective. In T. Reay, T. B. Zilber, A. Langley, & H. Tsoukas (Eds.), Institutions and organizations: A process view (pp. 33–41). Oxford University Press.

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance (political economy of institutions and decisions). Cambridge University Press.

- Ornellas, A., Spolander, G., & Engelbrecht, L. K. (2018). The global social work definition: Ontology, implications and challenges. Journal of Social Work, 18(2), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316654606

- Penninx, R. (2009). Decentralising integration policies. Managing migration in cities, regions and localities. Policy Network.

- Peters, G. B. (2012). Governance as political theory. In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of governance (pp. 19–32). Oxford University Press.

- Pollitt, C., Talbot, C., Caulfield, J., & Smullen, A. (2004). Agencies: How governments do things through semi-autonomous organizations. Springer.

- Popitz, H. (2017). Phenomena of power. Columbia University Press.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semi-sovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

- Sen, A. K. (1999). Commodities and capabilities. Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. K. (2000). Development as freedom. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Strier, R., & Bershtling, O. (2016). Professional resistance in social work: Counterpractice assemblages. Social Work, 61(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sww010

- Špiláčková, M. (2014). Soziale Arbeit im Sozialismus: Ein Beispiel aus der Tschechoslowakei (1968-1989). Springer-Verlag.

- Timor-Shlevin, S. (2022). Between othering and recognition: In search of transformative practice at the street level. European Journal of Social Work, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2022.2092456

- Timor-Shlevin, S., & Benjamin, O. (2022). The struggle over the character of social services: Conceptualising hybridity and power. European Journal of Social Work, 25(1), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2020.1838452

- Timor-Shlevin, S., Hermans, K., & Roose, R. (2022). In search of social justice-informed services: A research agenda for the study of resistance to neo-managerialism. British Journal of Social Work, 0(0), 1–17.

- Torfing, J., Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., & Sørensen, E. (2012). Interactive governance: Advancing the paradigm. Oxford University Press.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society. University of California Press.

- Weiss-Gal, I., & Gal, J. (2014). Social workers as policy actors. Journal of Social Policy, 43(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279413000603

- Weiss-Gal, I., & Gal, J. (2020). Explaining the policy practice of community social workers. Journal of Social Work, 20(2), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318814996

- Weiss-Gal, I., Gal, J., Schwartz-Tayri, T., Gewirtz-Meydan, A., & Sommerfeld, D. (2020). Social workers’ policy practice in Israel: Internal, indirect, informal and role contingent. European Journal of Social Work, 23(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1499614

- Whitehead, A. N. (2010). Process and reality. Simon and Schuster.

- Wilson, H. (2020). Social work assessment: What are we meant to assess? Ethics and Social Welfare, 14(1), 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2019.1686046

- Woodcock, J., & Dixon, J. (2005). Professional ideologies and preferences in social work: A British study in global perspective. British Journal of Social Work, 35(6), 953–973. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch282

- Zogata-Kusz, A. (2022). Policy advocacy and NGOs assisting immigrants: Legitimacy, accountability and the perceived attitude of the majority. Social Sciences, 11(2), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020077