ABSTRACT

Social work focuses on the social relationships, which the COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact. The article explores Finnish social workers’ reflections on utilising digital environments in client relationships during the pandemic. The article is framed by relationship-based social work. The data consist of two datasets that together form a continuum: Finnish social workers’ personal diaries from mid-March to the end of May 2020, and interviews with 17 diary writers conducted in April and May 2021. The research questions are: What kind of challenges related to relationships can be identified in the early phase of the pandemic? What were the facilitators for conducting relationships as the pandemic continues? What kind of practice began to emerge as the pandemic proved to be long-standing? The diaries and interviews were analysed using thematic analysis. Three themes were identified: relationships drifting into danger, reconstitution of relationships and emerging opportunity for relationship-based social work. The results demonstrate serious challenges, but also new opportunities, as well as temporal variation and contextual change related to relationship-based social work during the pandemic.

TIIVISTELMÄ

Sosiaalityön fokus on sosiaalisissa suhteissa, joihin COVID-19-pandemia vaikutti merkittävästi. Artikkelissa tutkitaan suomalaisten sosiaalityöntekijöiden kokemuksia digitaalisten toimintaympäristöjen hyödyntämisestä asiakassuhteissa pandemian aikana. Tutkimuksen kehyksenä toimii suhdeperustainen sosiaalityö. Kaksiosainen aineisto muodostaa jatkumon: suomalaisten sosiaalityöntekijöiden maaliskuun puolivälistä toukokuun loppuun vuonna 2020 pitämät päiväkirjat ja päiväkirjaa pitäneiden 17 sosiaalityöntekijän haastattelut, jotka toteutettiin huhti-toukokuun aikana vuonna 2021. Molemmat aineistot analysoitiin hyödyntäen temaattista sisällönanalyysia, jonka avulla paikannettiin kolme teemaa: asiakassuhteiden vaarantuminen, asiakassuhteiden uudelleen rakentuminen ja uusien mahdollisuuksien ilmaantuminen suhdeperustaisessa sosiaalityössä. Tulokset osoittavat suhdeperustaiseen sosiaalityöhön pandemian aikana liittyneitä merkittäviä haasteita, mutta myös uusia mahdollisuuksia, sekä aikaan ja paikkaan sidoksissa olevaa muutosta.

Introduction

Social work focuses on the social relationships, connections and people in relation to their environments. Reflections on relationship-based social work have deep roots (Howe, Citation1998; Ruch, Citation2005; Trevithick, Citation2003), but in the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions regarding face-to-face contacts were recommended to be avoided as much as possible. The solution was to utilise digital environments, raising the question of the possibilities of building relationships digitally (Banks et al., Citation2020; Pascoe, Citation2022). In the current article, we explore Finnish social workers’ reflections on utilising digital environments in building relationships with clients during the pandemic. In Finland, the digital leap was extensive (Fiorentino et al., Citation2022), making the Finnish context interesting to analyse. The present study covers two empirical phases of the pandemic: the springs of 2020 and 2021.

There is always a relationship between a practitioner and client that is contextual by nature, regardless of the issue discussed or technique used (Howe, Citation1998; Ruch, Citation2018). However, the status of relationship-based social work has tended to rise and fall with wider contextual, for example, administrative and political, changes (Howe, Citation1998). In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in relationship-based social work practice (Järveläinen et al., Citation2021; Murphy et al., Citation2013), but relationship-based social work has also been challenged in the context of neoliberalism, outcome-driven practice and austerity, indicating that some social workers have acted more as techno-bureaucrats than relationship-based practitioners (Hingley-Jones & Ruch, Citation2016). In Finland, the field of relationship-based social work can be described as tensioned. Heavy workloads, juridification, bureaucratisation and administrative pressures related to managerialism, such as increasing reporting tasks, have challenged the promotion of relationship-based social work. At the same time, there is a strong tradition in Finland both in researching and conducting relationship-based social work, reciprocity and partnership in social work–client relationships and creating a dialogue in this relationship (Hall et al., Citation2014; Järveläinen et al., Citation2021; Vornanen & Pölkki, Citation2018).

Information and communication technology (ICT) is currently utilised broadly and has become more extensively used in social work during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fiorentino et al., Citation2022; Mishna et al., Citation2021; Pink et al., Citation2022). However, the utilisation of ICT has been initiated slower in social work than elsewhere in society, and the potential benefits of ICT in social work have not been fully acknowledged (Harrikari et al., Citation2021; Pink et al., Citation2022). In Finnish social work, ICT has been utilised mainly in managerial work, communication between professionals and documentation. Other forms of digitalisation, such as video conferencing with clients, were quite rarely used before the pandemic, but the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it a digital leap (Pyykönen et al., Citation2022).

Both opportunities and risks are present when discussing digitalisation and social work (Steiner, Citation2021). Although social workers have expressed their technological optimism (Nordesjö et al., Citation2022), digital tools are simultaneously viewed as a threat to social work relationships (Pascoe, Citation2022; Steiner, Citation2021). Digitalisation has been seen as offering new opportunities for social work in establishing and maintaining relationships. However, according to Steiner (Citation2021), applying technologies requires continuous ethical discretion because digital environments are not passive tools, and their implementation has effects on social work contexts. ICT should not reduce responsibility, neglect basic humanity or exclude people from social work. Also, a lack of adequate training, confidentiality, professionalism and resources have been regarded as the challenges of digitally mediated social work (Boddy & Dominelli, Citation2017; Goldkind et al., Citation2019; Pascoe, Citation2022). According to Pascoe (Citation2022), the core principles of social work, such as active partnership between social workers and clients and a holistic approach to clients’ life situations, are disrupted by technology. ICT creates a new realm of spatial possibilities when it comes to forming relationships (Fiorentino et al., Citation2022) compared with traditional home visits, where corporeality, senses and intuitions are present (Manthorpe et al., Citation2021; Pink et al., Citation2022). Critical and creative ways of perceiving, thinking and acting related to client relationships and digitalisation have been called for both prior to (Goldkind et al., Citation2019) and during the pandemic (Ferguson et al., Citation2022).

Several studies on the COVID-19 pandemic and social work have made it evident how extensive and drastic the impact on societal restrictions has been on both working and everyday lives (e.g. Ferguson et al., Citation2022; Harrikari et al., Citation2021; Manthorpe et al., Citation2021; Ross et al., Citation2021). During the first months of the pandemic, the recommendations for social distancing forced social work to take a digital leap. Social work has faced significant challenges during the pandemic, but it has also demonstrated its capacity to adapt, mobilise resources and develop new practices (e.g. Ferguson et al., Citation2022; Harrikari et al., Citation2021). In the current article, we take part in these discussions in the frame of relationship-based social work in an increasingly digitalised environment. Technologies, as such, are not in our focus but are viewed more as establishing spaces for relationship-based social work through their enabling and constraining elements (Fiorentino et al., Citation2022). The goal is to shed light on social workers’ experiences of how relationships with clients changed and were constituted when utilising digital environments during different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The data were collected in two phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: the first phase focuses on the beginning of the pandemic in the spring of 2020 and the second phase one year later, in the spring of 2021, where the pandemic was proving to be long-standing and new practices emerged in social work. We seek to answer the following questions: What kinds of challenges related to relationships can be identified in the early phase of the pandemic? What were the facilitators for conducting relationships as the pandemic continued, and what kind of practices began to emerge as the pandemic proved to be long-standing? The data consist of 33 personal diaries that social work professionals created from mid-March to the end of May 2020 and interviews with 17 diary writers conducted in April and May 2021. The diaries and interviews were analysed using thematic content analysis.

Relationship-based social work and digitalising environments

Theoretical conceptions of relationship-based practice vary, referring to the different ways of working (Hingley-Jones & Ruch, Citation2016; Murphy et al., Citation2013). Usually, psychodynamic and system-based approaches have been highlighted (e.g. Howe, Citation1998; Ruch, Citation2018; Vornanen & Pölkki, Citation2018). Trevithick (Citation2003) views relationship-based practice in relation to an assessment from a psychosocial perspective, and Ruch (Citation2018) suggests that relationship-based social work is not only about empathy, respect, reliability, engagement and partnership but that it is also antioppressive practice in which inclusiveness is an integral component of professional intervention. Empirical studies have focused on professional relationships as enabling and promoting change and alleviating distress (Rollins, Citation2020).

We see relationship-based social work, such as that by Ruch (Citation2005), as highly multifaceted and complex by nature and grounded on humanistic principles and reflectivity (also Rollins, Citation2020). The relations of power are always present in terms of the assignment of the organisation and environment in which the encounter occurs. Social workers should be aware of that and use their power in an empowering way. We understand the relationship between client and social worker as a negotiable, contextual and temporal phenomenon. Encounters between social workers and clients include and manifest beliefs, assumptions, interpretations, understandings and misunderstandings and monologues and dialogues (Hall et al., Citation2003; Parton & O’Byrne, Citation2000). We see creating a working alliance, confidentiality, mutual respect and social presence between the social worker and client as a basis of relationship-based social work. By ‘social presence’, we mean the experiences of the partner of the communication being fully present, salient to the person and encountering responsibility (LaMendola, Citation2010). Social presence is created through responsiveness, open communication and dialogue (Fiorentino et al., Citation2022). The digital environment alters the encounter: the social presence and confidential atmosphere must be created through digital devices, without traditional face-to-face contact.

Relationship-based social work practice is, at the same time, a goal and tool for promoting change. The importance of relationship-based social work and social workers’ communication skills has been highlighted by empirical studies conducted among service users (Beresford et al., Citation2008; Simpson, Citation2017). Fostering trust, communicating effectively, making appropriate assessments and synchronising interventions can lead to better results from the service users’ point of view (Simpson, Citation2017). In the context of digital social work, it is essential to consider how these elements become realised while utilising digital environments and remote connections.

The research on online therapy has demonstrated that forming alliances between professionals and clients in online services is possible and that online relationships can be convenient, safe and empowering (van de Luitgaarden & van der Tier, Citation2018). However, van de Luitgaarden and van der Tier (Citation2018) point out that applying mental health research to the social work field can be problematic because the emphasis in social work lies more on contextual and psychosocial issues. Therefore, more analyses are required in social work research on the role of communication, forming working alliances and conducting assessments in digital environments.

There have been some debates in the literature regarding whether ICT alters interpersonal interactions (Byrne & Kirwan, Citation2019) and what follows from the lack of physical proximity. These concerns are particularly justified when it comes to relationship-based work with vulnerable groups. Emmanuel Levinas suggests that the ‘face speaks’ and that ‘the face’ is a foundation of ethics (Citation1995, p. 87) while responsibility emerges in face-to-face contact; that is, by encountering a face, a person becomes aware of the other's vulnerability (Domrzalski, Citation2010). Responsibility is an inevitable part of authentic relationships, and seeing another face increases one's responsibility; hence, face-to-face contact can be viewed as a cornerstone of moral and ethical agency (Levinas, Citation1995). We may, however, ask what the ‘imperative of responsibility’ (Steiner, Citation2021, p. 3365) is now because it seems that the social, spatial and temporal effects of digital technologies extend to all areas of society. The question remains regarding how ICT technologies can be used to empower service users in social work. ICT forms a special space for encounters between professionals and clients (Fiorentino et al., Citation2022; Granholm, Citation2016; Nordesjö et al., Citation2022). Thus, one of the key questions is how the ICT infrastructure can enable encountering and promoting dialogue.

Materials and methods

The data consist of two datasets that together form a continuum. Data collection began right after the Finnish government applied the Emergency Powers Act on 16 March 2020 and declared lockdowns. We recruited social workers from a closed Facebook group (more than 3,000 professional Finnish social workers as members) to write diaries about the observations, thoughts, experiences and feelings they faced during the first wave of pandemic. The diaries were written from 19 March 2020 to 31 May 2020. We asked the social workers to write about the following: (1) ‘What kinds of observations and experiences do you have about the phenomena and challenges that occur in the lives of social work clients during the pandemic?’ (2) ‘What challenges do social work and its practices face during a pandemic?’ (3) ‘What kind of thoughts does the pandemic period evoke in you as a social work professional?’ The social workers pondered about creating and maintaining relationships with clients, as well as the challenges and opportunities related to relationships in these exceptional circumstances, which enabled us to analyse the data through relationship-based social work. In total, 33 diaries (93,292 words) were returned in digital form via secured email. The participants were all women, aged 30–53 years, working in different areas of social work (adult social work, elderly care, child protection, disability services, services for immigrants and substance users).

The second dataset, collected from 4 March 2021 to 25 May 2021, consists of personal interviews (154,064 words) of the same social workers who had written the diaries. A request to participate in an interview was sent to all of them; however, only 17 diary writers signed up, and reminders were not sent because participation was voluntary and the number of interviewees and information they provided was regarded as sufficient. The profiles of the interviewed social workers were similar to that of the diary writers regarding age and areas of social work. The personal interviews were conducted through MS Teams and audio-recorded. In the interviews, we asked the social workers to reflect on their experiences of the effects of the pandemic on their work, what kind of changes have occurred since the beginning of the pandemic and what they had learned from working in pandemic conditions after one year. One of the main themes we asked was the relationships between clients and social workers in digital environments. Moreover, we asked the interviewees to reflect on the early phase of the pandemic, how practices were adapted to the new circumstances and how they viewed their clients’ situations. The interview data allowed us to establish a comparative follow-up setting, analyse temporal variations and shed light on the changes in building and maintaining relationships as the pandemic progressed.

In terms of data analysis, we combined data-driven and theory-informed qualitative thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Clarke & Braun, Citation2017), which provided a flexible approach for developing themes and allowed for an active researcher role. The reading of the data was framed by our preunderstanding of relationship-based social work from the literature. We first familiarised ourselves with the data and then extracted, both from the diaries and interviews, data samples where the relationships between social workers and clients were described. The samples were divided into rough thematic groups in a preliminary sense and set on a chronological timeline. Second, we refocused on our research questions based on the preliminary findings, and as the analysis progressed, we identified certain patterns of meaningful themes (e.g. Clarke & Braun, Citation2017): relationships drifting into danger, reconstitution of relationships and emerging opportunities for relationship-based social work. Finally, the themes were reviewed against the data (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017), and the analysis ended in a dialogue between the data and literature. Hence, the data analysis phases overlapped. The quotations from the diaries are marked with the first letter D and interviews with the letters ‘Int’ before the date.

Ethics

In terms of research ethics, the guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK, Citation2019) were followed. Detailed information about the research project was delivered to the participants. The participants were informed of the voluntary nature regarding their writing the diaries and participating in the interviews. Regarding the diaries, the participants were informed that sending a diary meant giving one's consent. Likewise, giving an affirmative answer to the interview invitation meant a consent to the interview. The background information was kept minimal: age, gender, professional title, education and the main client group were asked. Social workers participated in the study as individual licenced professionals, and the organisations they worked in were not known. If the diaries or interviews contained any identifiable information, the research teams anonymised the data.

Results

Relationships drifting into danger

In terms of conducting relationship-based social work in the context of the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, the following question arose: How would it be possible to maintain and start relationships with clients? Successful implementation of relationship-based social work requires a supportive organisational base, as well as training, supervision and leadership (Ward et al., Citation2018). When the pandemic started and restrictions were put into place, it soon became obvious that both the social work organisations and their workers had different capabilities and orientations to work remotely (also Pascoe, Citation2022; Pink et al., Citation2022). The readiness for the transition and change in working culture seemed to vary. Our data suggest that there were no overall guidelines or organisational instructions to utilise digital environments, which, in turn, led to chaotic and puzzling times, thus endangering the maintenance and formation of relationships with clients. In addition, during the first weeks of the pandemic, many meetings with clients were cancelled by social workers or the clients themselves:

The past week was marked by confusion, chaos and cancellation of appointments. (D4/20/03/25)

I am confused by how poorly social workers perceive the contexts, whether remote connections are suitable or not. (D29/20/03/30)

Each social worker has been left to their own discretion on assessing the necessity of contacts. Some employees think that all appointments can be handled online and do not have any necessary contacts. How equally are clients being treated? (D7/20/04/04)

Relationship-based social work can be seen as a primary tool for social work assessment (Ruch, Citation2018). The social workers regarded digitalised environments as something that made the assessment more complicated. Some social workers suggested that remotely conducted assessments can lead to wrong situational analyses and a deficient holistic picture (see also Pascoe, Citation2022). In the early phase of the pandemic, debates on the risks concerning digital devices and environments were frequent, especially because of a lack of organisational instructions. The diaries demonstrated – sometimes even excessively so – the responsibility of an individual social worker to judge how to conduct client relationships:

At the same time, we are instructed to work remotely but are still forced to take responsibility for all clients and meet them face to face without any protective equipment or the possibility of being tested. The employee is left alone to decide what encounters are necessary and what are not. (D7/20/04/04)

Reconstitution of relationships

Our data demonstrate that, to uphold relationships with clients, the use of digital tools increased as the COVID-19 pandemic continued, but it did so at a varying pace in different organisations and locations. One of the earliest mentions of this change in social workers’ attitudes towards the adoption of digital tools was at the end of March 2020; this reflection came from a social worker who had already developed digitally mediated social work before the pandemic. She described how there was suddenly a huge need for their pioneering working methods:

We don't have to give any justifications for doing social work digitally [anymore]. Now, everyone wants to know how to do it. (D29/20/03/30)

I tried to get instructions from the supervisor, but we all were equally clueless, so I also tried to keep the superior informed of the current news. Some employees haven't yet acquired equipment to work remotely, so I try to promote that as well. (D4/20/03/25)

We were obliged to find creative ways to help people. We realised that this would all be hard, especially for those already in weak positions. This is a really difficult situation. We figured out that this was the time to roll up our sleeves and get to work. (Int5)

The digital connection functioned surprisingly well. The client could stay at home and control the situation more than in my office. This made the setting more equal. (D17/20/04/16)

For some clients, this seems to fit surprisingly well. Some are more active and participative. It seems easier to focus on the agenda. This has been a huge insight for me, who has always sworn in the name of face-to-face meetings. (D30/20/03/23)

Emerging opportunity for relationship-based social work?

The interviews conducted a year after the diary writing indicated some changes in utilising the digital environment in client relationships. Not only the social workers, but also many clients were now more familiar with digital environments and devices. The pandemic era brought many challenges, but it also offered emerging opportunities for relationships and relationship-based social work. New ways of doing the work were developed, which some of the interviewees called the ‘new normal’ (Int7). The benefits of working remotely with clients were seen as ‘a possibility’ (Int9) because it saved time on travelling, fostered flexibility in planning work and allowed working hours to be used more efficiently:

With clients living 200 kilometres away, you ask if it is worth travelling as matters can be handled remotely. At the same time, you can save nature, work time, people and everything. (Int1)

A digital service path with a chat feature, different tests, and home tasks were introduced. – Clients do independent tasks in between meetings, and the meetings vary between face to face, digital encounters and phone calls. (Int12)

The interviews demonstrated that the social workers could decide how to act in client relations and how to form and maintain relationships. Practical knowledge accumulated gradually: there must be face-to-face contact at least once in the early phase of the relationship; ‘otherwise something will be missing’ (Int1). The negotiations between the social worker and client became the key element in assessing and deciding how the relationships would be maintained and which methods would be applied. ‘We had to and wanted to leave it to the social workers’ discretion’ (Int7). It has been frequently suggested that face-to-face encounters and remote meetings through digital devices could be applied as a hybrid model (see Pink et al., Citation2022). The hybrid model gave room for professional discretion to decide whether to meet face-to-face or remotely, which of the options would work best and how to apply the digital devices in each situation (also Manthorpe et al., Citation2021; Pink et al., Citation2022). However, the decision should be made together with mutual understanding:

Remote meetings suit some client situations but must be discussed with them. It must be a mutual decision whether to meet face to face or remotely. Remote meetings are okay, but every now and then, you must see the client face to face. (Int3)

The pandemic is a shared experience. [–] And this could be used in creating interactions. (Int4)

Discussion

The current study has focused on social workers’ reflections on utilising digital environments in their relationships with clients in the context of the COVID‒19-pandemic. We analysed Finnish social workers’ reflections based on two sets of data covering two stages of the pandemic: the early phase of the pandemic in spring 2020 and one year later. The goal has been to understand the relationship between digitalising environments and relationship-based social work.

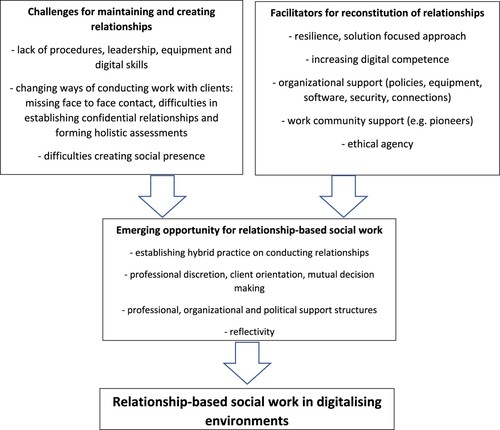

At the beginning of the pandemic, the client relationships in social work were largely in danger because of the restrictions to face-to-face contacts and varying abilities to utilise digital environments. The organisations were unprepared because of a lack of procedures, leadership, equipment and digital skills (). Some of the social work organisations decided to stop all face-to-face meetings with clients, while other units and employees were capable of utilising digital tools or decided to continue face-to-face meetings, especially with the most vulnerable clients. In addition to risks, the facilitators for relationships in digitalising environments and for change were also identified, such as social workers’ resilience, a solution-focused approach and increasing digital competence. Support from the organisation and work community was also needed. Ethical agency, professional discretion and critical reflection, which are at the core of relationship-based social work, gave reassurance to implement digital environments as a part of encountering clients.

Figure 1. Challenges and facilitators of relationship-based social work in digitalising environments.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the same ethical, practical and organisational critiques were presented as in Pascoe's (Citation2022) study in Northern Ireland context. Her findings highlight negative outcomes of technology on relationship-based social work. In the Finnish context, as the pandemic continued and proved to be long-standing, new practices to maintain and form relationships with clients emerged and became established. The results demonstrate how the contextual change of social work during the COVID-19 pandemic brought not only serious challenges, but also new opportunities to relationship-based social work and options to diversify, add flexibility and even strengthen relationships with clients. However, in terms of the quality of relationship-based social work in the postpandemic period, the balance between challenges and opportunities depends on how social work will be capable of making this change.

The drastic change in the social work context caused by the COVID-19 pandemic raised the question of how to conduct, start and maintain meaningful and effective social work relationships. The results suggest that, more than just the technique, conducting social work relationships in digital environments requires special orientation, sensitivity, knowledge and skills in communication and interaction (e.g. Byrne & Kirwan, Citation2019; Howe, Citation2018). Our data indicate that social workers have the opportunity to hybridise interactions with clients because of their expertise in relationships.

Social work professional discretion was used when the ways, methods and techniques to conduct relationships with clients were considered (also Manthorpe et al., Citation2021). Some of the social workers were pleased to find new opportunities to work with clients, and negotiations with clients were highlighted. Using various channels to maintain and form relationships can, at its best, lead to more intensive communication, and digital devices can boost social presence quite well (Simpson, Citation2017). Although face-to-face contact was preferred in many cases, social presence was seen as possible to gain with appropriate devices, learning to utilise digital environments and professional skills in interaction. The same skills in interaction can be utilised in digital environments with creativity and overcoming both technical and attitudinal barriers. On the other hand, social workers’ partly differing preferences on conducting client relationships need to be critically scrutinised. It is crucial to reflect on whether the utilisation of digital environments is based on their convenience from the perspective of a social worker, on their efficiency related to organisational goals or on the client's situation and need (Granholm, Citation2016; Ross et al., Citation2021). The basis for relationship-based social work lies in organisational facilities and culture and in the social workers’ and clients’ skills to create interaction and dialogue in digital environments while attempting to understand how digitally mediated communication can support relationship-based social work (see Byrne & Kirwan, Citation2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic has offered a fundamental lesson for social work (Manthorpe et al., Citation2021); the pandemic has created a space for social work to reflect relationship-based social work: what its current position is and how it can be utilised in different situations and environments. In our data, some social workers reflected on ‘waking up’ with traditional relationship-based social work, for example, that related to the significance of encounters and face-to-face interactions with clients. On the other hand, it has been learned how relationships with clients can be effectively conducted in specific contexts in digital and remote environments (also Pink et al., Citation2022); these insights related to the possibilities of hybrid relationship-based social work are worth taking advantage of.

As for the limitations of the current study, participation during the COVID-19 pandemic likely required special effort, and it is possible that the participants who attended this research were exceptionally active social workers. When applying the results, it must be noted that the participants worked in different social work areas where the role of relationship-based social work may vary. However, our aim was to obtain a holistic picture of relationship-based social works’ relation to digital environments in a pandemic context, not compare different fields of social work. In terms of digital techniques, it must be kept in mind that remote work was conducted not only through video conferencing, but also by phone, which contains a different interacting environment. In addition, the study is framed by the Finnish welfare system. However, despite these contextual differences, the reflections of Finnish social workers in the present study are relatively similar to research in different contexts (e.g. Manthorpe et al., Citation2021; Pink et al., Citation2022; Ross et al., Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marjo Romakkaniemi

Dr. Marjo Romakkaniemi, Ph.D. is Senior Research Fellow at the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Lapland. Her research interests include the advancement of professional knowledge in social work, social work in mental health, in rehabilitation and with disabled people.

Kivistö Mari

Dr. Mari Kivistö, Ph.D. is a University Lecturer in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Lapland. Her research has focused on social work and digitalisation, social work in disability services, and recovery-orientation in mental health services.

Harrikari Timo

Dr. Timo Harrikari, PhD, is a Research Professor at the National Institute for Health and Welfare THL, Finland. Harrikari’s research interest include child welfare, young offenders, probation and disaster social work.

Fiorentino Vera

Vera Fiorentino, Ms. Soc. Sc., is a Junior Research Fellow at the University of Lapland. Her research interests cover social work practices in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, implementing social services in digital forms and global crisis. She is currently doing research on the changes the COVID19-pandemic caused in social work practice.

Leppiaho Tuomas

Tuomas Leppiaho, B. Soc. Sc., is a master’s student in political sciences and a research assistant in the ‘PANDA’-research group at the University of Lapland. His main interest areas are in political theology, global drug policies, and ontopolitical conflicts and socio-economical sustainability in the Arctic region.

Hautala Sanna

Sanna Hautala, Ph.D. is a Professor of Social Work at the University of Lapland. Her main research interests are research of substance abuse, social work in catastrophes, and processes of recovery.

References

- Banks, S., Tian, C., De Jonge, E., Shears, J., Shum, M., Sobočan, A. M., Strom, K., Truell, R., Úriz, M. J., & Weinberg, M. (2020). Practising ethically during COVID-19: Social work challenges and responses. International Social Work, 63(5), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820949614

- Beresford, P., Croft, S., & Adshead, L. (2008). “We don’t see her as a social worker”: A service user case study of the importance of the social worker’s relationship and humanity. British Journal of Social Work, 38(7), 1388–1407. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm043

- Boddy, J., & Dominelli, L. (2017). Social media and social work: The challenges of new ethical space. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1224907

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Byrne, J., & Kirwan, G. (2019). Relationship-based social work and electronic communication technologies: Anticipation, adaptation and achievement. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2019.1604499

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Domrzalski, R. (2010). Suffering, relatedness and transformation: Levinas and relational psychodynamic theory. Advocates’ Forum, 23–34.

- Ferguson, H., Kelly, L., & Pink, S. (2022). Social work and child protection for a post-pandemic world: The re-making of practice during COVID-19 and its renewal beyond it. Journal of Social Work Practice, 36(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2021.1922368

- Fiorentino, V., Romakkaniemi, M., Harrikari, T., Saraniemi, S., & Tiitinen, L. (2022). Towards digitally mediated social work: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on encountering clients in social work. Qualitative Social Work. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250221075603

- Goldkind, L., Wolf, L., & Freddolino, P. P. (2019). Digital social work: Tools for practice with individuals, organizations, and communities. Oxford University Press.

- Granholm, C. (2016). Social work in digital transfer: Blending services for next generation. Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Social Studies.

- Hall, C., Juhila, K., Matarese, M., & Van Nijnatten, C. (eds.). (2014). Analysing social work communication: Discourse in practice. Routledge.

- Hall, C., Kurri, K., Partanen, T., Juhila, K., Parton, N., Pösö, T., & Wahlströn, J. (eds.). (2003). Constructing clienthood in social work and human services: Interaction, identities and practices. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Harrikari, T., Romakkaniemi, M., Tiitinen, L., & Ovaskainen, S. (2021). Pandemic and social work: Exploring Finnish social workers’ experiences through a SWOT analysis. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(5), 1644–1662. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab052

- Hingley-Jones, H., & Ruch, G. (2016). “Stumbling through?” relationship-based social work practice in austere times. Journal of Social Work Practice, 30(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2016.1215975

- Howe, D. (1998). Relationship-based thinking and acting in social work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 12(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650539808415131

- Howe, D. (2018). Foreword. In G. Ruch, D. Turney, & A. Ward (Eds.), Relationship-based social work: Getting to the heart of practice (2nd ed., pp. 7–9). Jessica Kinsley Publishers.

- Järveläinen, E., Rantanen, T., & Toikko, T. (2021). Meanings of a client-employee relationship in social work: Client’s perspectives on desisting from crime. Nordic Social Work Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2021.1981984

- LaMendola, W. (2010). Social work and social presence in an online world. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 28(1‒2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228831003759562

- Levinas, E. (1995). Ethics and infinity: Conversations with Philippe Nemo. Duquesne University Press.

- Manthorpe, J., Harris, J., Burridge, S., Fuller, J., Martineau, S., Ornelas, B., Tinelli, M., & Cornes, M. (2021). Social work practice with adults under rising second wave of COVID-19 in England: Frontline experiences and the use of professional judgement. British Journal of Social Work, 51(5), 1879–1896. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab080

- Mishna, F., Bogo, M., Root, J., Sawyer, J.-L., & Khoyry-Kassabri, M. (2012). “It just crept in”: The digital age and implications for social work practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, 40(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-012-0383-4

- Mishna, F., Milne, E., Bogo, M., & Pereira, L. F. (2021). Responding to COVID-19: New trends in social workers’ use of information and communication technology. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49(4), 484–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00780-x

- Murphy, D., Duggan, M., & Stephen, J. (2013). Relationship-based social work and its compatibility with the person-centred approach: Principled versus instrumental perspectives. British Journal of Social Work, 43(4), 703–719. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs003

- Nordesjö, K., Scaramuzzino, G., & Ulmestig, R. (2022). The social worker-client relationship in the digital era: A configurative literature review. European Journal of Social Work, 25(2), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1964445

- Parton, N., & O’Byrne, P. (2000). Constructive social work: Towards a new practice. Palgrave.

- Pascoe, K. M. (2022). Remote service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: Questioning the impact of technology on relationship-based social work practice. British Journal of Social Work, 52(6), 3268–3287. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab242

- Pink, S., Ferguson, H., & Kelly, L. (2022). Digital social work: Conceptualising a hybrid anticipatory practice. Qualitative Social Work, 21(2), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250211003647

- Pyykönen, A.-M., Lammintakanen, J., & Pehkonen, A. (2022). Syrjiikö digitalisointi ihmisiä sosiaalipalveluissa? [Does digitalisation discriminate people in social services?] (Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiön julkaisu 50). Kunnallisalan Kehittämissäätiö.

- Rollins, W. (2020). Social worker-client relationships: Social workers perspectives. Australian Social Work, 73(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1669687

- Ross, A. M., Schneider, S., Muneton-Castano, Y. F., Caldas, A. S., & Boskey, E. R. (2021). “You never stop being a social worker”: experiences of pediatric hospital social workers during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Work in Health Care, 60(1), 8–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2021.1885565

- Ruch, G. (2005). Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: Holistic approaches to contemporary child care social work. Child and Family Social Work, 10(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00359.x

- Ruch, G. (2018). Theoretical frameworks informing relationship-based practice. In G. Ruch, D. Turney, & A. Ward (Eds.), Relationship-based social work: Getting to the heart of practice (2nd ed., pp. 37–54). Jessica Kinsley Publishers.

- Simpson, J. E. (2017). Staying in touch in the digital era: New social work practice. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 35(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2017.1277908

- Steiner, O. (2021). Social work in digital era: Theoretical, ethical and practical considerations. British Journal of Social Work, 51(8), 3358–3374. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa160

- TENK. (2019). The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland: Finnish national board on research integrity TENK guidelines 2019 (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK publications 3/2019). https://tenk.fi/sites/default/files/2021-01/Ethical_review_in_human_sciences_2020.pdf.

- Trevithick, P. (2003). Effective relationship-based practice: A theoretical exploration. Journal of Social Work Practice, 17(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/026505302000145699

- van de Luitgaarden, G., & van der Tier, M. (2018). Establishing working relationships in online social work. Journal of Social Work, 18(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316654347

- Vornanen, R., & Pölkki, P. (2018). Reciprocity and relationship-based approach in child welfare. In M. Törrönen, C. Munn-Giddings, & L. Tarkiainen (Eds.), Reciprocal relationships and well-being (pp. 109–125). Routledge.

- Ward, A., Ruch, G., & Turney, D. (2018). Introduction. In G. Ruch, D. Turney, & A. Ward (Eds.), Relationship-based social work: Getting to the heart of practice (2nd ed., pp. 13–16). Jessica Kinsley Publishers.