ABSTRACT

Employing Dutch longitudinal information on 1250 second-generation Moroccan and Turkish migrants we investigate cultural assimilation using attitude questions on marriage and sexuality (including measures of homophobia). Two theoretical approaches guide our analyses. First, it is expected that the family of origin may push migrants in a more conservative direction. Second, it is expected that aspects of individual achievement in social, cultural and socioeconomic domains may pull migrants in more liberal directions. We find that Moroccan and Turkish migrants have considerably more conservative values about marriage and sexuality than natives, but there is also variation within the second generation. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses for migrants indicate that the role of parents is particularly important: migrant children of religiously more orthodox parents and children of parents who were poorly integrated socially and culturally in their youth, currently have more conservative values about marriage and sexuality, even when individual characteristics are controlled for. Of the various aspects of individual achievement, we find that especially social integration of the second generation is a relevant predictor of liberal values, and not socioeconomic indicators of integration. These results remain significant in a stringent longitudinal test which minimises the bias due to reverse causation.

Introduction

One of the most striking and much-debated aspects of immigration to Western Europe lies in the norms and values that migrants have (Koopmans Citation2015). Whereas norms and values in the Western world have become considerably more liberal over the past decades, many non-Western migrants originate from Muslim countries where norms and values generally are traditional. Conservative norms and values in these countries can be found in several important life domains, including gender equality, sexuality, marriage, family, religion, and politics (Norris and Inglehart Citation2012). Cultural differences between natives and Muslim migrants have played an undisputed role in debates about assimilation theory. According to the classic view, cultural differences between natives and immigrants will gradually diminish over time and will set in motion assimilation processes in various other domains as well, thereby improving the economic situation of immigrant groups and encouraging their integration into social networks of a host society (Gordon Citation1964). In contemporary views, this exogenous causal influence of cultural assimilation is no longer accepted, but the concept of cultural assimilation – sometimes called ‘acculturation’ – remains important (Alba and Nee Citation1999).

In various studies on cultural assimilation, the second generation plays an important but complex role. Because norms and values are acquired in a multifaceted process of socialisation (Bronfenbrenner Citation1986), migrants from the second generation clearly have more potential to adapt to more liberal norms and values of the destination country than their parents who migrated themselves. At the same time, however, members of the second generation are exposed to competing pressures: they experience liberal values from their peers, the media, and the schools and workplaces they encounter, but they may also be socialised into conservative values by their parents and in their ethnic community. It therefore is plausible that especially second-generation Muslim migrants experience these opposing forces in their everyday life. The outcome of this process with several cross-pressures is uncertain and probably also depends on various contextual-level conditions (neighbourhoods, organisations, countries).

Some authors argue that under conditions of ethnic conflict and religious tensions, the second generation is even more strongly influenced by their ethnic or religious community. Under such circumstances, members of the second generation would respond negatively to discrimination and hold on to more conservative values of their ethnic group to protect themselves, a phenomenon called reactive ethnicity or oppositional culture (Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Wimmer and Soehl Citation2014). Other authors advocate a multiculturalist perspective and argue that the second generation has a dual identity in which some values become more liberal whereas others remain conservative, especially when these values are related to visible religious symbols of the origin group such as wearing a head scarf or special food laws (Verkuyten Citation2005). Neo-assimilation theory, in contrast, has argued that second-generation migrants are more likely to adapt to the values of a destination country when there is no new influx of migrants. In other words, it is argued that when the process of generational replacement is blocked, cultural assimilation will become more likely (Alba and Nee Citation1999). Since in most Western countries the inflow of migrants has continued, a scenario of assimilation is less likely in this view.

Although the debate about the cultural values of migrants is as old as Gordon’s classic study on assimilation, systematic empirical evidence on cultural assimilation has only recently become available. Of the studies that directly examined the values of migrants, most focus on gender-role attitudes, as this is one of the important dividing lines between Western Europe and the Muslim world (Inglehart and Norris Citation2003). Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel (Citation2009) showed that in Germany, second-generation migrants with a Muslim background had more conservative gender-role attitudes than native Germans although the second generation was clearly more liberal than the first generation. Religiosity had a negative impact on support for gender equality whereas education had a positive effect. Kashyap and Lewis (Citation2013) established that in the UK, Muslim migrants were more conservative about family issues than natives, as indicated by attitudes about premarital sex, abortion, and homosexuality; the gap was smaller, however, when migrants were compared to British natives who are religious. Spierings (Citation2015) compared Turks in Western Europe and in Turkey and showed that parental attitudes were less predictive of children’s gender-role attitudes when children grew up in Europe, a finding that is in line with assimilation theory. Probably the most elaborate study was presented by Idema and Phalet (Citation2007) who documented that Turkish adolescent women in Germany were more egalitarian about gender roles than their mothers, whereas adolescent men were not different from their fathers. Gender-role attitudes among adolescents were associated with several family background factors, in particular parental religiosity and mother’s education, but individual characteristics of the adolescents such as educational attainment and language proficiency proved important as well (Idema and Phalet Citation2007).

In summary, most studies on cultural assimilation stress the importance of religion for understanding traditional gender-role attitudes, but some authors also find fairly weak associations between gender-role attitudes and measures of religiosity (Scheible and Fleischmann Citation2013).

Research questions and approach

In the present paper, we examine the values of second-generation Muslim migrants towards premarital sex, unmarried cohabitation, single parenthood, divorce, and homosexuality. In the Western world, most of these so-called family values have become more liberal over time (Thornton and Young-DeMarco Citation2001; Kraaykamp Citation2002), a shift which has been considered an important driving force behind the Second Demographic Transition (Van de Kaa Citation1987). In the Netherlands, which is the country that we study, many people were opposed to divorce and unmarried cohabitation in the 1950s and 1960s and many people disapproved of homosexual relationships and premarital sex. Since then, tolerance of these behaviours has grown enormously (Kraaykamp Citation2002) and the Netherlands is now one of the most liberal societies in Western Europe in this respect (Arts, Hagenaars, and Halman Citation2003). In the Muslim world, in contrast, family values are strongly governed by religious doctrines and generally much more conservative. Premarital sex, unmarried cohabitation, and homosexual relations are considered sinful in most traditional interpretations of Islamic law and there are sometimes (violent) sanctions against those who break these rules (Yip Citation2009; Chesler Citation2010). A massive shift in a liberal direction will therefore be unlikely but some degree of change among migrants is likely, so it is important to examine who has become more liberal and who has not.

To explain the degree of assimilation in values about marriage and sexuality within the second generation of Muslim migrants, we advocate a theoretical distinction between influences of family background features and influences of individual characteristics. The first concept belongs to a more general line of research in which family resources are studied as an important source of inequality in society. In this field, aspects of family background including father’s and mother’s education and occupation, parental income, unemployment, and parents’ social and cultural capital, have proven to influence children’s socioeconomic attainment (Teachman, Paasch, and Carver Citation1997; McLanahan Citation2004; Breen et al. Citation2009). The second concept belongs to a branch of research that studies how higher education, the pivotal example of an individual achievement factor, tends to liberalise the social, cultural, and political values that adolescents have (Hyman and Wright Citation1979; Kalmijn and Kraaykamp Citation2007).

To investigate cultural assimilation, our first, descriptive research question is: (1) How do the values about marriage and sexuality of second-generation Muslim migrants compare to natives? We compare second-generation migrants with Dutch natives, but we recognise the religious heterogeneity within the second generation as well as within the native majority group. Our second, more explanatory research question zooms in on the population of Muslim migrants: (2) To what extent are family background characteristics and individual characteristics associated with the values about marriage and sexuality of second-generation Muslim migrants? In dealing with this question, we investigate what factors pull second-generation migrants into a more conservative direction, and what factors are pushing them into a more liberal direction. Hereby, we do not intend to say that individual migrants do not make choices or are passive actors in this process, instead, the concepts of push and pull actually illustrate the various cross-pressures that migrants are facing.

We answer our questions by analysing a recent nationally representative longitudinal survey in the Netherlands (NELLS). These data contain a systematic oversample of persons who were born in Morocco and Turkey and persons born in the Netherlands with Moroccan or Turkish parents. Our main set of analyses is based on the first wave of NELLS, and is therefore cross-sectional. The NELLS was repeated among the same respondents after four years. As a result, some of our hypotheses can also be tested by looking at individual changes in values. Given the short time between the waves (four years), the amount of cultural change is expected to be limited so that these latter tests will be conservative. If we do find effects in our longitudinal models, we are more confident that the effects are not affected by selection bias or biased by reverse causation. For example, cultural assimilation could lead to more acceptance and hence, better social integration, or a lack of cultural assimilation could reduce opportunities for upward economic mobility. In cross-sectional models the effects of, for instance, social integration on cultural values could thus be biased by reversed causality. In longitudinal models, such reverse effects are reduced.

The Dutch migration context is comparable to that in many other Western European countries. The Netherlands had large influxes of labour migrants during the 1970s and 1980s, especially from Morocco and Turkey, and this has triggered a continuous stream of (chain-)immigration. Contemporary migration is still overwhelmingly from Muslim countries but the sending countries have changed, as have the reasons for migration, now being a mix of asylum seekers and economic migrants. There are some serious tensions between segments of the Dutch population and Muslim citizens and attitudes among the Dutch population on Muslims migrants are to some extent polarised (Meuleman, Lubbers, and Kraaykamp Citation2016). While the second generation has made considerable steps in education and occupational attainment, levels of unemployment among Muslims migrants remain high, especially among young men. This mix of ethnic tensions and economic inequality is clearly not a favourable context for cultural assimilation (Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Alba and Nee Citation1999).

Theoretical background and hypotheses

From various theoretical traditions, expectations can be derived on the presence or absence of cultural assimilation of second-generation migrants with respect to values about marriage and sexuality (Berry Citation1997; Rudmin Citation2009; Norris and Inglehart Citation2012; Voas and Fleischmann Citation2012). Our discussion on theory is divided into two subsections, one that relates to pull (family) factors that may keep children integrated in traditional ethnic and religious communities with more conservative values about marriage and sexuality, and one that discusses push (individual) factors that may facilitate cultural assimilation in a liberal direction.

Theoretically, it is preferable to investigate these family and individual influences in combination. One would expect that possible influences of parents on children’s values about marriage and sexuality will be predominantly indirect, via immigrant children’s own traits. In other words, parental influences will (in part) be mediated by individual socioeconomic and social influences. Alternatively, we could argue that there will be direct effects of family characteristics on children’s values, independently of children’s own individual characteristics. Direct effects may emerge through parental control and authority. For example, university educated migrants may be persuaded by their parents to hold on to religious doctrines, making it more difficult for them to express liberal views on important family matters.

Family characteristics

A first line of reasoning addresses forces that pull children into a more conservative direction in their thinking on various aspects of family life. The moral values that people have are largely developed during a process of primary socialisation, via modelling or direct instruction (Bandura Citation1977; Grusec and Hastings Citation2008). Hence, characteristics of parents play a pivotal role in this process. Our general expectation is that a lack of integration of parents in the host society will be associated with more conservative values about marriage and sexuality among their children. We make a distinction between socioeconomic, cultural, and social dimensions of parental integration, as these correspond to the standard dimensions of assimilation (Gordon Citation1964; Berry Citation1997; Rudmin Citation2009).

A major indication of parental integration in a host society can be found in their socioeconomic position. Many immigrant parents have lower status jobs and have attained only limited education and mostly in the origin country (Van Tubergen Citation2005). We expect that the lower parents’ socioeconomic status, the more conservative the values of children will be (adjusted for the child’s own socioeconomic status). Not only is a lower socioeconomic position generally related to more conservative values (also among parents), we also expect that migrant children who grew up in economic adversity, may blame the destination country for not providing a more supportive opportunity structure to migrants. This may result in a negative stance towards the host society, which in turn may lead to a rejection of the typical liberal values of that society (Wimmer and Soehl Citation2014).

Cultural integration of parents is conceptualised in two ways. First, we consider parents’ religious behaviours and beliefs (Voas and Fleischmann Citation2012; Doebler Citation2013). Most dominant interpretations of Islamic rules are strict when it comes to issues of sexuality, marriage, and divorce (Kandiyoti Citation1988; Esposito Citation2002; Inglehart and Norris Citation2003; Yip Citation2009). So, the more orthodox parents are in terms of their own religion, the more conservative the values of their children will be. Several studies in the past have shown that religiosity is transmitted from parents to children (Kelley and De Graaf Citation1997) and this is particularly true for migrants (De Hoon and van Tubergen Citation2014). Hence, the effect of parental religiosity on children’s values will probably be closely related to children’s own religious beliefs and behaviours. Note that such religious influences are not unique for Islam; many religions, especially in their orthodox interpretations, disapprove of sex outside of marriage, homosexuality, unmarried cohabitation, and divorce (Hyde and Delamater Citation2014). Second, we consider the degree to which parents have adopted cultural traditions that are typical for the Netherlands. Examples are viewing Dutch television and eating Dutch dishes. We expect that a cultural orientation towards the host society among parents will also affect children’s values.

Children’s cultural assimilation may also be blocked by the degree to which parents are integrated in the social domain. If migrant parents have little contact with Dutch neighbours and friends, children will be exposed to a more homogeneous ethnic community while growing up. The ethnic community can socialise the child into more conservative values and it can also strengthen the process of parental socialisation. Being exposed to the conservative views of one’s parents will have a stronger influence on children if parents’ views are similar to the views of the larger network to which the child is exposed. Having limited opportunities to interact with natives when migrant children are young also leads to a stronger sense of ethnic identity and so, indirectly affects a child’s adoption of the more conservative values grounded in their ethnic and religious community.

Individual characteristics

A second approach considers individual resources that may push children into a more liberal direction in comparison to their parents. Surely, the attainment of valuable resources makes (cultural) assimilation easier, because it enlarges all kinds of opportunities in life. Moreover, it is expected that personal investments in acquiring human capital will enlarge the bond with a destination society leading to a greater acceptance of a country’s cultural climate, including views on family issues (Kelley and De Graaf Citation1997). We again make a distinction between socioeconomic and social characteristics. Note that an individual’s own religiosity is not considered because this characteristic is cultural in nature; it is a parallel outcome rather than an explanatory variable.

Socioeconomic success of second-generation migrants mostly finds its origin in education. Institutions of higher education communicate values directly and in Western countries these values are often egalitarian and liberal. Moreover, schooling is believed to augment a person’s breadth of perspective which reduces intolerance and increases support for ‘new’ types of living arrangements (Hyman and Wright Citation1979; Kalmijn and Kraaykamp Citation2007). Next, having paid work should, according to classic assimilation theory, also foster the adoption of more liberal values. A lack of economic success among migrant children could lead to resentment towards the host society and result in a rejection of that society’s dominant norms and values. Conversely, having economic success may lead to a more positive view of the host society which in turn may encourage a reconsideration of one’s original values.

We conceptualise the social integration of children by looking at their own social contacts and network composition. It is generally believed that more frequent contact with native friends and neighbours will nurture cultural assimilation. From exposure theory (Kroska and Elman Citation2009), it follows that more intensive contact with people who hold liberal views on marriage and sexuality will eventually push second-generation migrants in a more liberal direction. Of course, the causality runs in both directions here: having liberal values probably fosters social integration just as exposure to natives in a social network makes values more liberal (Martinovic Citation2013). A longitudinal design – as used in this paper – is needed to disentangle these effects.

Data and measurement

To test our hypotheses concerning cultural assimilation we analyse data from the NEtherlands Longitudinal Lifecourse Survey (NELLS: Tolsma et al. Citation2014). The first wave of the data collection of the panel survey NELLS took place in 2009/2010 and used a face-to- face approach in combination with a self-completion questionnaire. Within NELLS a two-stage sampling procedure was applied in which first a quasi-random selection of 35 municipalities by region and urbanisation took place. In the second stage, a random selection of respondents from the population registers based on age (15–45 years) and ethnic background was taken. People of Moroccan and Turkish origin, as the major migrant groups in the Netherlands, were oversampled. The response rate of the first wave of NELLS is 52% which is good for a study that involves ethnic minorities. Response rates for Turks and Moroccans were a little bit lower: 50% and 46% respectively (Tolsma et al. Citation2014). The NELLS-data are representative for the Dutch population except that women and 35–45-year-olds are slightly overrepresented, while residents of large cities are somewhat underrepresented.

The initial sample was N = 5312 in wave 1. At the end of the questionnaire in wave 1, respondents were asked whether they could be contacted again. Respondents who answered positively on this question and with complete information in wave 1 were approached for questioning in wave 2 (83.9%). On average, there is a four-year gap between wave 1 and wave 2. The average response in wave 2 is 75%, but again response of people from Turkish and Moroccan decent is slightly lower (for a complete description, see codebook).

Before analysing data from wave 1, we excluded respondents who did not hand in the written questionnaire in which their family values were measured (n = 410), or had missing values on the relevant attitude items (n = 28), respondents with migration backgrounds other than Moroccan or Turkish (n = 419), and first-generation migrants who arrived after age 12 (n = 748). Of the remaining 3707 cases, 1250 were of Moroccan or Turkish origin and 2457 were of Dutch origin. In the migrant sample, 42% were born in the Netherlands and 58% were born abroad but migrated before age 12. This latter group – sometimes called the 1.5 generation – is also considered as belonging to the second generation in our analysis since this group has been educated in the Netherlands. To deal with missing information on some of the other independent characteristics, we applied multiple imputation in Stata. In the longitudinal panel analyses, our final sample consists of 581 respondents (due to panel attrition). Respondents of Dutch origin were only included in the descriptive statistics, not in the regression models.

Measurements

The NELLS asked a series of questions on family values. We have selected five items that in previous research have been associated with conservative family values (Thornton and Young-DeMarco Citation2001; Kalmijn and Kraaykamp Citation2007). People could give their opinion on marriage with two statements ‘living together is a good alternative for marriage’ and ‘couples that have children should be married’ on a five-point scale running from (1) totally disagree to (5) totally agree. Three items referred to people’s opinion on homosexuality, getting a divorce, and premarital sex. With the question ‘Do you think the following activities are right or wrong?’ respondents could answer (1) always wrong, (2) almost always wrong, (3) sometimes wrong, and (4) never wrong. We constructed a scale by first standardising each item and then taking the mean across items (α = .71 for the migrant sample). Higher scores indicate more conservative values. Note that all scales discussed below were constructed in this fashion.

Parental socioeconomic position first was indicated by their educational level. To measure parental schooling, we took the maximum score of mother’s and father’s educational attainment using an eight-point scale running from (1) no primary education, to (8) university degree. Foreign degrees were recoded to a comparable degree in the Dutch school system. Father’s occupational status was measured with an ISEI-score (ranging between 11 and 89) of father’s professional activities when a respondent was aged 12–14 years, or at a prior time in case of temporary unemployment. We also measured father’s employment indicating whether the father was in paid labour at that time (1 = paid work). An index for maternal employment was constructed using three questions indicating whether mother worked for pay when the respondent was (1) a toddler, (2) in primary school, and (3) in secondary school.

Cultural characteristics of parents are measured first with indicators of parental religious orthodoxy in the respondent’s youth. We used four questions on parental religious behaviours, respectively ‘reading the Koran’, ‘wearing a head scarf’ (mother), ‘taking part in Ramadan’, and ‘refraining from alcohol use’ with answers (1) no and (2) yes, and a single question on father’s visiting of religious services, running from (1) for never, to (7) for more than once each week. The five (standardised) items were combined into a scale (α = .75). Second, we use a scale of cultural integration via the following three activities of parents when the respondent was growing up: watching Dutch television, reading books or newspapers in Dutch, and preparing meals originating from the Dutch cuisine (with answers (1) no and (2) yes). Since this scale is a count of dichotomous items, we report no Cronbach’s α.

As an extra measure of parents’ cultural integration, we included whether the father adhered to a Sunnite or another Muslim denomination (1 = Sunnite). Sunni and Shia are the two major denominations of Islam and sufficient variation within the migrant groups of both Turkish and Moroccan descent exists. Although differences between Sunnites’ and Shiites’ normative rules are not formally defined, generally the Sunnite branch is perceived as being more strict when it comes to family values.Footnote1 Note that those who did not indicate that they were Sunnite largely chose ‘other Islam’ (88%). We also constructed the variable parents intermarried (1 = yes) that indicates if one of the respondent’s parents was born in the Netherlands.

To measure parents’ social integration, we include one item of whether parents had Dutch friends and acquaintances visiting in their home when the respondent was growing up. Although this is a single-item construct, it is a direct indicator of the concept that we want to measure. We calculated the correlation between parents’ social integration and their cultural integration (into Dutch culture), and this was r = .46, which is very good and gives us confidence in the social integration measure. We cannot rule out that there is reporting bias in this domain but previous studies on the quality of retrospective measures suggest that reporting bias on behavioural items is not dramatic (Hardt and Rutter Citation2004). Moreover, the bias can both be upward due to the tendency to make perceptions in the past in line with the present, and downward due to measurement error (de Vries and de Graaf Citation2008).

To measure an individual’s integration in the socioeconomic domain, we first use respondent’s schooling, measured as the highest educational level a person attained, or a respondent’s current level (when in education) in years, and ranges from 4 years for primary school (not completed), to 16.5 years for a university master degree. We also included whether a respondent was either employed in paid work (1 = working), or in school (1 = in full-time education). Finally, we constructed two measures that indicate the financial wealth of the second-generation migrants. First, we measured being a home owner (1 = yes). Second, we calculated a poverty index with answers on five questions about the respondents’ financial position (e.g. unable to replace broken things, lagging behind with paying the rent/mortgage). The scale consists of the number of financial problems (0–5).

Migrants’ social integration in the NELLS questionnaire is measured with four variables. First, we used a personal network module in which respondents were asked about the five most important contacts they had. Using this measure, we constructed a count of the number of majority (i.e. Dutch) friends that a person has (recoded to any versus none). Second, we constructed a relative measure of contact with majority neighbours. This was based on questions about personal contact with Dutch and Turkish/Moroccan (depending on the group) neighbours, with answers running from (1) never to (7) (almost) every day. We subtracted the number of Turkish/Moroccan contacts from the number of Dutch contacts. Third, we constructed a relative measure of contact with majority colleagues or school mates. This variable was constructed in the same way as the measure for neighbours. Finally, a person’s number of high-status weak ties is measured with the question ‘Do you have friends, acquaintances or family members with the following occupations … ’. Respondents had to answer this question for a list of occupations of which we picked the high-status occupations: engineer, company director/manager, real estate broker, lawyer/councillor, accountant, and musician/artist/writer. A scale is constructed taking the number of friends and relatives with a high-status occupation.

displays means, standard deviations, minima, and maxima of all the variables (for migrants) before imputation. For reasons of interpretation all variables, except dichotomous variables, are standardised in the regression models.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the variables.

Research plan and models

To begin, we present a simple bivariate comparison of native Dutch and second-generation Moroccans and Turks on all five indicators of conservative values (). This addresses our first question: how conservative or liberal are the values of migrants when compared to natives? In this analysis, the scale of values was constructed for the full sample (migrants and natives combined). In the explanatory analyses, to begin we limit the analysis to second-generation migrants from the first wave of NELLS and estimate OLS regression models that provide us with information on whether family characteristics and individual characteristics affect cultural assimilation with respect to values about marriage and sexuality (). Finally, we present a longitudinal panel analysis on a restricted sample of second-generation migrants (due to panel attrition) predicting conservatism in values about marriage and sexuality in wave 2 while controlling for values in wave 1 (). To check if panel attrition affects our results, we replicated the cross-sectional models that we estimated in the first wave using only the cases for which we have complete data (both in wave 1 and 2). As a sensitivity analysis we tested whether effects were different for Moroccan and Turkish respondents but none of the interactions were statistically significant. There are also no remarkable differences in terms of the responses to the attitude statements so we feel safe in combining the two groups as meaningful examples of Muslim migrants in the Netherlands.

Table 2. Attitudes towards family issues for natives and migrants by origin country in the Netherlands.

Results

Descriptive results

shows differentiation in values about marriage and sexuality between native Dutch respondents and second-generation migrants from the first wave of NELLS. The degree of conservatism in five aspects of family life is presented using the original coding. As it comes to support for cohabitation as an alternative for marriage, about 42% of the Moroccans and 43% of the Turks subscribe to this statement (agree), while 70% of all native Dutch do. For the issue of having children without being married, the native-migrant divide is larger; 72% of all Dutch find that this is acceptable against only 27% of the Moroccans and 23% of the Turks. also reveals large differences in attitudes towards homosexuality and premarital sex. Among migrants, around 41–43% state that homosexuality is ‘always’ or ‘almost always wrong’, while this is only 8% among natives. Premarital sex is considered ‘(almost) always wrong’ by 45% of the Moroccans and 40% of the Turks, against only 7% of the natives. With respect to the acceptance of divorce, similar albeit smaller differences are found. Although there is a clear divide between migrants and natives, it is also interesting to see that there is considerable variation within the migrant group. A sizeable minority of Moroccan and Turkish respondents have liberal views, for example, more than 30% of them find homosexuality ‘never wrong’ and 26% of the Moroccans and 30% of the Turks agree with the statement that sex before marriage is ‘never wrong’. So, it is relevant to study variation within the migrant population.

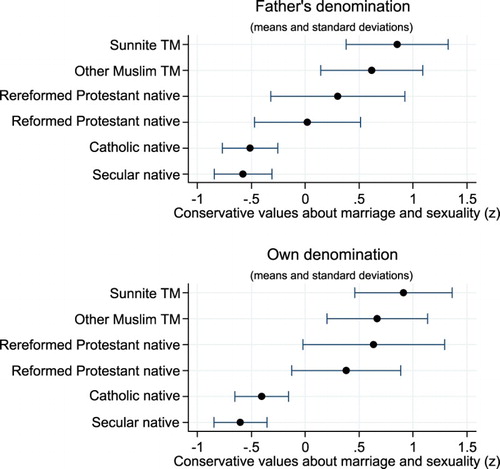

A first indication whether conservatism in values about marriage and sexuality is related to family influences may be found in by looking at people with and without a religious upbringing. This distinction is also made for natives, which makes a comparison all the more interesting, although it is clear that different types of religious backgrounds are compared. For Protestants, we make a distinction between Reformed Protestants, who in the Netherlands form the more liberal segment of Protestants, and Rereformed Protestants, who are the more orthodox denomination (De Graaf and Te Grotenhuis Citation2008). Other, mostly Orthodox Protestants are included in the Rereformed group. We used father’s religious denomination in the top panel of to study differences and we use the scale of family values as an outcome (constructed for the full sample). For descriptive reasons, we also break down values about marriage and sexuality by the respondent’s own religious denomination, presented in the bottom panel. presents means as well as standard deviations of the scores. Standard deviations tell us how much cultural diversity there is in each religious group.

Figure 1. Level and diversity of values about marriage and sexuality for natives and second-generation migrants by denomination

Overall a clear pattern is observed. People with a non-religious and a Roman-Catholic background are least conservative in their values, while respondents originating from a Muslim background are the most conservative. We see that Rereformed Protestants are clearly more conservative than Reformed Protestants in terms of their values about marriage and sexuality. Sunnites are more conservative than other Muslim migrants. Although migrants from Moroccan and Turkish origin clearly show more conservatism in their values about marriage and sexuality than natives, the gap is clearly smaller when a comparison is made with Rereformed Protestants.

When we focus on a respondent’s own religious denomination (bottom panel of ), we see those belonging to native religious groups are more conservative as observed looking at father’s denomination. This may seem plausible since those who left the faith were probably more liberal. We also see that the native-migrant gap becomes smaller, especially when comparing current Protestants to non-Sunni migrants. Sunni migrants, however, remain the most conservative group, also when current denomination is considered.

If the religious groups are ordered in terms of the orthodoxy of the religious denominations as they exist in the Netherlands and in the migrant’s origin countries, as is attempted in , there seems to be a more or less linear association between the degree of religious orthodoxy and an individual’s conservative values about marriage and sexuality. At the same time, however, we see that scores in the Muslim groups are more diverse than they are in the secular native group. That there is more diversity underscores the importance of focusing on migrants and calls for explanatory analyses of the differences within this population. This is what will be done in the remainder of the paper.

Regression results

presents an ordinary least squares regression for our measure of conservatism in values about marriage and sexuality among migrants. Four models are estimated. Models 1 and 2 include parental socioeconomic, cultural, and social characteristics. Models 3 and 4 add individual socioeconomic and social characteristics. These models estimate effects of family and individual characteristics on values and deal with the issue of mediation of family influences by individual effects. Since all continuous variables are standardised, coefficients can be interpreted as effect sizes (standardised coefficients for continuous independent variables and Cohen’s d for dichotomous independent variables).

Table 3. Regression of conservative values about marriage and sexuality: Moroccan and Turkish migrants.

Model 1 in indicates that older migrants are less conservative than younger ones, that those who migrated before age 12 are more conservative than those who were born in the Netherlands, and that Turkish migrants are slightly more conservative than Moroccan migrants. There is no gender difference. The socioeconomic integration of a person’s parents only seems of moderate importance. A higher level of parental schooling, however, is associated with less conservatism. Although it proved irrelevant for a person’s values whether the father was working when the respondent was young and what his occupational status was, having had a working mother is associated with more liberal values.

When adding aspects of parents’ social and cultural integration into the model, all socioeconomic aspects of the parents lose significance. So, of the family background factors, we find that primarily social and cultural aspects matter. First, it seems that children from a Sunnite Muslim father hold more conservative values on family life and that having one Dutch parent is associated with more liberal values. Most importantly, the results show that parental religious orthodoxy is highly relevant in predicting conservatism in the second generation. Of the continuous variables, this one has the largest effect in the table (standardised b = .249). In contrast, a social orientation of parents towards Dutch society by inviting Dutch acquaintances in their home reduces conservatism of values about marriage and sexuality among their children. Also, the consumption of Dutch cultural products by parents as in reading Dutch books, watching Dutch television and preparing Dutch meals, is associated with more liberal values among their children.

In Model 3, individual aspects of socioeconomic integration are added. As expected, socioeconomic success of second-generation migrants is associated with more liberal values. Migrants who are employed and who have accomplished a higher level of schooling have less conservative values. The effect of education that we find for migrants seems small compared to the effects of education on values that are usually found in majority populations (Kalmijn and Kraaykamp Citation2007). Little influence is found of the financial aspects of integration; owning a home and experiencing poverty do not significantly affect a person’s values about marriage and sexuality. Model 4 includes individual social characteristics of second-generation migrants. It shows that having a majority friend and having frequent contact with majority neighbours are both associated with more liberal values on family issues. These findings suggest that being embedded in an ethnic community reduces opportunities for cultural assimilation.

From both Model 3 and 4 it is striking to observe that, although central individual characteristics have a clear impact on values, the effect of parental religious orthodoxy remains highly significant. Only 14% of the effect of parental religious orthodoxy is mediated by all individual characteristics. One explanation for this is that parental religiosity is only weakly associated with children’s social and socioeconomic integration. Additional correlational analyses show that religious orthodoxy in the parental generation is not associated with children’s education or with children’s involvement in majority networks. For this reason, the two forces – family and individual – have much room to work independently of each other, working simultaneously as pull and push factors in the assimilation process. Mediation of the other parental effects, such as effects of their social integration and their consumption of majority culture is somewhat more successful as these effects decline or become insignificant in Model 4. The full model explains nearly one-fifth of the total variance in values.

In , we present results of our longitudinal dynamic analyses employing both waves of the NELLS data. As a dependent variable, we again employ our measure of conservatism in values. Unfortunately, panel attrition causes a reduction of a little more than 50% in the number of respondents in our models. So, as a robustness check we first compare the full model, including all relevant family and individual variables for all cases (, Model 4), to the same model for cases that remained in the sample in wave 2 (, Model 1). So, the independent and dependent variables are the same, only the sample size is different. We conclude that the two models show virtually identical results which suggest that panel attrition was mainly non-selective.

Table 4. Regression of conservative values about marriage and sexuality with panel data: Moroccan and Turkish migrants.

In Model 2 of , we use migrants’ values measured in wave 2 as a dependent variable. In Model 3, we add our wave-1 measure of conservative values to study individual changes in conservatism. By doing so, we to some extent control for issues of selectivity and reverse causality. The correlation between values about marriage and sexuality in wave 1 and wave 2 is r = .68, which shows that there is a considerable amount of stability in migrant’s values. We also calculated the correlation between waves for respondents of Dutch origin and find a higher correlation (r = .81). In other words, there appears to be more cultural change among migrants than among Dutch natives. This is not evidence of assimilation, however, because when we compare the means of the (unstandardised) scales in the two waves, we see no significant difference (t = .02). More detailed analyses show that there are changes in a liberal direction as well as changes in a conservative direction. Note that we abstain from analysing how changes in the independent individual variables affect changes in values, in part because many of these independent variables do not change or only to a limited extent (due to a limited time frame).

Model 3 shows that parental religious orthodoxy has a significant effect on value change. Hence, parental orthodoxy blocks second-generation migrants from becoming more liberal (b = .096). It can also mean that migrant children have a greater chance of becoming more conservative over time when parents were orthodox in a person’s childhood. Possibly, this may be understood by pre-migration factors that refer to already existing differences between migrants in orthodoxy. Another explanation could be retreat from Dutch society by children with an orthodox background, something that is perhaps triggered by a lack of acceptance by the majority. The other indicator of parents’ cultural integration no longer has a significant effect in the panel model, suggesting that there is no further change in a conservative direction as a result of parents’ lack of adaptation to the Dutch culture. This also applies to the effects of social integration and being of Sunnite background and having intermarried parents; these effects are no longer significant in the panel model (Model 3) and thus do not predict change in our panel design.

On the other side, some individual characteristics also remain significant in the panel model (Model 3). Social integration, as exemplified by having contacts with majority neighbours (b = −.090), and having majority friends (b = −.190), does foster the adoption of more liberal values. Although these effects are smaller in the panel design (cf. Model 2 and 3), they are clearly not fully explained by reverse causality, with liberal values leading to more integration. Interesting is that hardly any significant effects are found from integration in the socioeconomic domain. These effects were (occasionally) significant in the cross-sectional design but are not strong enough to generate change in values. So, cultural change is predominately nurtured by social mixing, and not so much by migrants being economically successful.

Conclusion and discussion

Employing information on 1250 second-generation Moroccan and Turkish migrants in the Netherlands, in this article we investigated the prominent and topical issue of cultural assimilation with respect to values about marriage and sexuality. Values were measured with statements on homosexuality, premarital sex, cohabitation, and divorce. We show that migrants are considerably more conservative than natives. For example, about 40% of people with a Moroccan or Turkish background (almost) always find homosexuality wrong and disapprove of premarital sex. Among natives, these percentages are 8% and 7%, respectively. The gap between migrants and natives is smaller when native Protestants are the reference group, especially when Rereformed Protestants are considered. In comparison to the Rereformed, primarily the Sunnite Muslims seem more conservative than natives, not the other Muslim migrants. Note, however, that Rereformed Protestants currently comprise only a small fraction of the Dutch majority population of that age (15–47), that is, 15% in our sample. The large majority of natives in the Netherlands are secular and when comparing Muslims to secular natives, the gap is large. At the same time, we emphasise that differences are more strongly connected to religion, and especially orthodox religiosity, than to the Muslim faith per se.

Our descriptive analyses also indicate much diversity in values in the migrant population and our main goal therefore was to explain variation within the migrant community. Why do some migrants adapt to the dominant liberal stance in values about marriage and sexuality in the Netherlands, while others retreat and hold on to conservative opinions in these matters? Two theoretical approaches guided this aim. First, it was expected that various family factors may push migrants towards a more conservative stance on family issues, and second it is recognised that individual characteristics of social and socioeconomic integration may pull migrants to a more liberal direction.

Our cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses revealed foremost that the role of parents is very important for Muslim migrants’ values. Currently, children are more conservative in their values about marriage and sexuality when during their childhood, parents displayed more traditional religious behaviours and when parents were socially and culturally less well integrated in Dutch society. Even when individual indicators of educational attainment, financial position, and integration in Dutch social networks are controlled for statistically, these parental influences often remained significant. In a more stringent longitudinal design, the effect of social integration seems no longer significant but the effect of parents’ religious orthodoxy still is. Moreover, we find that the influence of parents’ religiosity is hardly mediated by individual characteristics. Of all variables that we considered, parental religious orthodoxy has one of the strongest effects. Of the two indicators of parents’ cultural integration, attachment to traditional Muslim faith thus seems clearly more influential than variation in the degree to which parents adapt to the Dutch culture.

We also considered individual determinants of values about marriage and sexuality. As expected we find that educational attainment and having a job are associated with more liberal values. Poverty and home ownership are not associated with these values. Moreover, the socioeconomic effects that were significant in the cross-section disappear in a longitudinal design. In contrast, we find that the social integration of the respondent, as indicated by contact with majority neighbours and having majority friends, is associated with less conservative values. The causal direction could be interpreted the other way around here, since having liberal values also may foster intergroup contact. In our longitudinal test, however, we found that effects of both aspects of social integration on values remain significant, suggesting that the causal direction is – at least partly – in the predicted direction: from ‘social to cultural’. In summary, of the individual determinants, we conclude that social aspects of integration are more relevant for cultural assimilation than socioeconomic aspects of integration. This conclusion echoes our findings for parents: we considered social, cultural, and socioeconomic characteristics of parents and never found any net significant effects of parents’ socioeconomic characteristics.

How do we evaluate the main results of this paper in a more theoretical sense? The finding that parental effects are strong while individual socioeconomic effects are weak may be (partly) understood by considering theoretical notions of socialisation (Bandura Citation1977; Bronfenbrenner Citation1986). In this literature, it is generally acknowledged that human development and learning must be understood in the context in which it occurs. Most important is the family context that constitutes the direct social environment of a person, the setting in which a person is raised. Less important for social learning are aspects of meso- and macro-level contexts that encompass the (sub)cultures that people are part of, being workplaces, schools, and peer networks. Accordingly, the development of children’s norms and values may be understood best by looking at aspects of socialisation in the family (parents’ religiosity and parents’ social contacts). Features of the broader environment outside the family, as in schooling and having work, would appear less important, also because the topics of marriage and sexuality are closely connected to a person’s private life.

Our research certainly holds some drawbacks. First, our longitudinal design is restricted to the inclusion of a measurement of conservative values about marriage and sexuality from wave 1 in our model, while preferably also changes in all independent characteristics should be studied in a fixed-effects approach. This however, proved difficult because of the limited number of respondents (in wave 2) and accordingly a limited amount of change in the independent characteristics (e.g. getting work, promoted, a degree). Second, the time interval that we studied (four years) may be relatively short to observe change in the dependent variable. For this reason, our longitudinal tests have been quite conservative, which is why we prefer to rely on both the cross-sectional and longitudinal results. Third, our research is restricted to second-generation migrants from Moroccan and Turkish origin. Recently, various migrants with refugee statuses have arrived in Western European countries. It seems interesting to study whether these mostly Muslim migrants encounter similar challenges of cultural assimilation as the offspring of Muslim labour migrants from the late 1970s and 1980s. Fourth, it could be interesting to explicitly compare effects of parental religious orthodoxy among migrants and natives when it comes to attitudes on marriage and sexuality.

What are the implications of our study for the debate on cultural assimilation of Muslim migrants in Western societies? Two main implications stand out. First, our study shows that an orthodox religious orientation of parents of second-generation migrants hinders their integration in the cultural domain, and thereby in the broader society. So, it seems that pre-migration factors (already existing differences between migrants in orthodoxy and type of religious convictions within the sending country) play an important role in explaining cultural integration in the next generation. In other words, a considerable part of the problem of cultural assimilation – in so far as one would perceive this as a problem – lies in the conservative cultural characteristics that (some) parents have brought with them in the process of migration, and not primarily in what happens in the receiving societies. Second, we established that socioeconomic aspects of integration in the receiving society play only a limited role in understanding cultural assimilation. Cultural assimilation seems more likely when there is more social mixing, and not so much when migrants achieve economic success. Subsequently, we believe the most favourable opportunities to reduce cultural differences between groups lie in patterns of social integration in a receiving society.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the sociology colloquium at Radboud University for their thoughtful comments, and Niels Spierings, three anonymous reviewers and the editor of Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies for valuable suggestions on previous versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. It was not possible to distinguish Shiites from other Muslim denominations. We therefore chose to focus on the distinction between Sunnite and all other denominations.

References

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 1999. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” In The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience, edited by C. Hirschman, P. Kasinitz, and J. DeWind, 137–160. New York: Sage.

- Arts, W., J. Hagenaars, and L. Halman. 2003. The Cultural Diversity of European Unity: Findings, Explanations and Reflections from the European Values Study. Leiden: Brill.

- Bandura, A. 1977. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press.

- Berry, J. W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46 (1): 5–34.

- Breen, R., R. Luijkx, W. Muller, and R. Pollak. 2009. “Nonpersistent Inequality in Educational Attainment: Evidence from Eight European Countries.” American Journal of Sociology 114 (5): 1475–1521. doi: 10.1086/595951

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1986. “Ecology of the Family as a Context for Human Development: Research Perspectives.” Developmental Psychology 22 (6): 723–742. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

- Chesler, P. 2010. “Worldwide Trends in Honor Killings.” Middle East Quarterly 17 (2): 3–11.

- de Vries, J., and P. de Graaf. 2008. “Is the Intergenerational Transmission of High Cultural Activities Biased by the Retrospective Measurement of Parental High Cultural Activities?” Social Indicators Research 85: 311–327. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9096-4

- De Graaf, N. D., and M. Te Grotenhuis. 2008. “Traditional Christian Belief and Belief in the Supernatural: Diverging Trends in the Netherlands between 1979 and 2005?” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47 (4): 585–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00428.x

- De Hoon, S., and F. van Tubergen. 2014. “The Religiosity of Children of Immigrants and Natives in England, Germany, and the Netherlands: The Role of Parents and Peers in Class.” European Sociological Review 30 (2): 194–206. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcu038

- Diehl, C., M. Koenig, and K. Ruckdeschel. 2009. “Religiosity and Gender Equality: Comparing Natives and Muslim Migrants in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (2): 278–301. doi: 10.1080/01419870802298454

- Doebler, S. C. 2013. “Religion, Ethnic Intolerance and Homophobia in Europe? A Multilevel Analysis Across 47 Countries.” PhD thesis, University of Manchester.

- Esposito, J. L. 2002. What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gordon, M. M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grusec, J. E., and P. D. Hastings. 2008. Handbook of Socialization. Theory and Research. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hardt, J., and M. Rutter. 2004. “Validity of Adult Retrospective Reports of Adverse Childhood Experiences: Review of the Evidence.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 45: 260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

- Hyde, J. S., and J. D. Delamater. 2014. Understanding Human Sexuality (Chapter 20: Ethics, Religion and Sexuality). McGraw-Hill (online).

- Hyman, H. H., and C. R. Wright. 1979. Education’s Lasting Influence on Values. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Idema, H., and K. Phalet. 2007. “Transmission of Gender-role Values in Turkish-German Migrant Families: The Role of Gender, Intergenerational and Intercultural Relations.” Zeitschrift für Familienforschung 19 (1): 71–105.

- Inglehart, R., and P. Norris. 2003. “The True Clash of Civilizations.” Foreign Policy 135: 63–70.

- Kalmijn, M., and G. Kraaykamp. 2007. “Social Stratification and Attitudes: A Comparative Analysis of the Effects of Class and Education in Europe.” The British Journal of Sociology 58 (4): 547–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00166.x

- Kandiyoti, D. 1988. “Bargaining with Patriarchy.” Gender & Society 2 (3): 274–290. doi: 10.1177/089124388002003004

- Kashyap, R., and V. A. Lewis. 2013. “British Muslim Youth and Religious Fundamentalism: A Quantitative Investigation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (12): 2117–2140. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2012.672761

- Kelley, J., and N. D. De Graaf. 1997. “National Context, Parental Socialization, and Religious Belief: Results from 15 Nations.” American Sociological Review 62 (4): 639–659. doi: 10.2307/2657431

- Koopmans, R. 2015. “Religious Fundamentalism and Hostility against Out-groups: A Comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (1): 33–57. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.935307

- Kraaykamp, G. 2002. “Trends and Countertrends in Sexual Permissiveness: Three Decades of Attitude Change in the Netherlands, 1965–1995.” Journal of Marriage and Family 64: 225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00225.x

- Kroska, A., and C. Elman. 2009. “Change in Attitudes About Employed Mothers: Exposure, Interests, and Gender Ideology Discrepancies.” Social Science Research 38 (2): 366–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.12.004

- Martinovic, B. 2013. “The Inter-ethnic Contacts of Immigrants and Natives in the Netherlands: A Two-sided Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (1): 69–85. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.723249

- McLanahan, S. 2004. “Diverging Destinies: How Children Are Faring Under the Second Demographic Transition.” Demography 41 (4): 607–628. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033

- Meuleman, R., M. Lubbers, and G. Kraaykamp. 2016. “Attitudes on Migration in a European Perspective. Trends and Differences.” In Trust, Life Satisfaction and Attitudes on Immigration in 15 European Countries, edited by J. Boelhouwer, G. Kraaykamp, and I. Stoop, 32–54. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

- Norris, P., and R. Inglehart. 2012. “Muslim Integration into Western Cultures: Between Origins and Destinations.” Political Studies 60 (2): 228–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00951.x

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96. doi: 10.1177/0002716293530001006

- Rudmin, F. 2009. “Constructs, Measurements and Models of Acculturation and Acculturative Stress.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 33 (2): 106–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.12.001

- Scheible, J. A., and F. Fleischmann. 2013. “Gendering Islamic Religiosity in the Second-generation Gender Differences in Religious Practices and the Association with Gender Ideology among Moroccan- and Turkish-Belgian Muslims.” Gender & Society 27 (3): 372–395. doi: 10.1177/0891243212467495

- Spierings, N. 2015. “Gender Equality Attitudes among Turks in Western Europe and Turkey: The Interrelated Impact of Migration and Parents’ Attitudes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (5): 749–771. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.948394

- Teachman, J. D., K. Paasch, and K. Carver. 1997. “Social Capital and the Generation of Human Capital.” Social Forces 75: 1343–1359. doi: 10.1093/sf/75.4.1343

- Thornton, A., and L. Young-DeMarco. 2001. “Four Decades of Trends in Attitudes toward Family Issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s.” Journal of Marriage and Family 63: 1009–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01009.x

- Tolsma, J., G. Kraaykamp, P. De Graaf, M. Kalmijn, and C. Monden. 2014. Netherlands Longitudinal Lifecourse Study-NELLS Panel Wave 1 2009 and Wave 2 2013-versie 1.1.

- Van de Kaa, D. J. 1987. “Europe’s Second Demographic Transition.” Population Bulletin 42: 1–59.

- Van Tubergen, F. 2005. The Integration of Immigrants in Cross-National Perspective: Origin, Destination, and Community Effects. Wageningen: Ponsen & Looijen.

- Verkuyten, M. 2005. “Ethnic Group Identification and Group Evaluation among Minority and Majority Groups: Testing the Multiculturalism Hypothesis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (1): 121–138. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.121

- Voas, D., and F. Fleischmann. 2012. “Islam Moves West: Religious Change in the First and Second Generations.” Annual Review of Sociology 38: 525–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145455

- Wimmer, A., and T. Soehl. 2014. “Blocked Acculturation: Cultural Heterodoxy among Europe’s Immigrants.” American Journal of Sociology 120 (1): 146–186. doi: 10.1086/677207

- Yip, A. K. T. 2009. “Islam and Sexuality: Orthodoxy and Contestations.” Contemporary Islam 3 (1): 1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11562-008-0073-8