ABSTRACT

This article asks how policy responses to migration in Italy have been shaped both by issue salience and by changing configurations on the centre right of Italian party politics both prior to and following the 2015 ‘migration crisis’. We show that, first, the increased politicisation of ‘irregular’ arrivals into Italy after 2015 changed migration from a relatively ‘quiet’ policy issue to one of ‘loud’ politics meaning that it was highly salient to the public. This salience significantly advantaged the Lega, who by this point had already transformed into an archetypal, European populist radical right party, but could now campaign successfully nationally and dominate the nominal ‘centre-right’ coalition. Second, the imposition when in government between June 2018 and September 2019 by the Lega of policies for migrants and asylum-seekers that focussed solely on prevention and removal and ended what remained of prior policy drift. We show that both trends conform to theoretical expectations regarding the relative power of interest groups and public opinion over public policy that are contingent on public issue salience, which we show to be the most plausible determinant of variation in migration policy, rather than public attitudes or party positions, during the period.

Introduction

This article asks how policy responses to migration in Italy have been shaped, before and after the 2015 ‘migration crisis’, both by the salience of immigration and by changing configurations on the centre right of Italian party politics. We show how two key components of contemporary migration to Italy elide into a set of issues that facilitate understanding of the changing ‘centre-right’, in terms of factions, role, positions and effects on policy. The first component, which has been by far the most prominent, focuses on migrants and refugees arriving by boat across the Mediterranean. Although clearly a European story, the radical right, anti-immigration Lega (before 2018 known as the Lega Nord) primarily benefited from, but also contributed to, the resulting politicisation of immigration, which saw their popularity grow – and later fall – markedly. The Italian ‘centre-right’ was thus transformed into a Lega-led national, nationalist and radical right political movement, aligned with the remnants of Forza Italia and Fratelli d’Italia as more junior partners, in a manner that would be impossible without Italy's unique electoral coalition arrangements and is likely to have effects that are far longer-lasting than the rise in the salience of immigration following the spike in irregular arrivals by boat across the Mediterranean.

The second aspect of contemporary Italian migration is actually a much longer-standing and decidedly national rather than European story. It centres on what could be called the everyday realities of migration to Italy where around 10 per cent of the Italian population are immigrants but where the political economy of contemporary Italian migration has not led to a recognisable migration policy (Einaudi Citation2007). Pastore (Citation2016) likened Italian migration policy to a ‘zombie policy’ because the ideas informing it have long since died but the policy continues to shamble on, echoing the theoretical notion of ‘policy drift’ (Hacker Citation2004). While migrant workers have become central to some areas of economic activity, routes for regular migration from outside the EU to Italy have been effectively closed. During the 2000s, the ‘centre-right’ governments of Silvio Berlusconi had pursued a pragmatic approach to irregular migration including regularisations (see , below). However, as we argue, the combination of these two issues and the reconfiguration of the ‘centre-right’ ended this relatively ‘quiet politics’ policy equilibria, transforming it into ‘loud politics’ and making it ever more difficult to develop a migration policy consistent with the presence of a significant immigrant population, associated legal obligations and societal and economic needs (Ambrosini and Panichella Citation2016).

In considering how Italian immigration politics and the centre-right changed before, during and after the 2015 ‘crisis’ we are necessarily dealing with multiple, overlapping dynamics that cannot be simplified into neatly identified, singular causal relationships. The ‘migration crisis’ after 2015 received widespread popular and academic attention as, variously, a humanitarian crisis, a crisis of seemingly flawed governance and a political crisis of widespread disquiet and, arguably, radicalisation and polarisation. Although to some extent a pan-European (and beyond) phenomenon, the ‘migration crisis’ was particularly acute in all of the above aspects in Italy. Similarly, Italian immigration politics broadly includes migration policy and governance, party positions, public opinion and immigration as an electoral issue. Furthermore, segmenting and analysing the constantly fluctuating Italian party system and its centre-right is a complicated task, arguably more so than in comparable party systems. Finally, in taking, we think necessarily, a broad view of both the ‘migration crisis’ and ‘migration politics’, we bring together multiple academic literatures, including those on migration governance, public policy, public opinion and electoral studies.

The article proceeds as follows: we first define the centre-right in Italy as well as the Lega's dubious but increasingly important membership of it; we then introduce our key theoretical arguments; outline how migration governance has changed in Italy in recent decades; outline how this can be explained by, first, changing political supply, particularly on the ‘centre-right’, and, second, by changing political demand as a result of the ‘crisis’.

What is the Italian centre-right?

A large number of political parties have at least some claim to hold the mantle of the ‘centre-right’ in Italy according to academic typologies (e.g. Mair and Mudde Citation1998). The particular electoral and ideological fluidity and fragmentation of Italian politics combine to make using these methods complicated (Bartolini, Chiaramonte, and D’Alimonte Citation2004). By 2019, Forza Italia and the relatively minor Alternative Popolare, Unione di Centro and Popolari per l’Italia were the only Italian members of the European People's Party (EPP), although, tellingly, Italy also provided an additional nine members of the EPP in the past, more than any other country.Footnote1

Most Italian parties have since 1993 also formed electoral coalitions. The 2018 coalition of the Lega, Forza Italia, Fratelli d’Italia, Noi con Italia and Unione di Centro, as well as a long list of minor and regional parties, was commonly labelled as the centre-right coalition, giving each member a nominative claim to being ‘centre-right’. A similar electoral coalition was formed for the 2013 election, though in that year the more centrist, Christian democrat Unione di Centro and Scelta Civica (which would go on to form 2018s Noi con l’Italia) had a perhaps more credible ideological claim to being ‘centre-right’.

In terms of experts surveys, the 2017 Chapel Hill Experts Survey (Polk et al. Citation2017) classified Unione di Centro, Alternative Popolare and Centro DemocraticoFootnote2 as ‘Christian democrat’ and Forza Italia as ‘conservative’.Footnote3 For the 2018 election, the Manifesto Project classified Civica PopolareFootnote4 and Noi con Italia as Christian democrat and Forza Italia and Fratelli d’Italia as ‘conservative’ (Volkens et al. Citation2020).Footnote5

The decreasingly relevant Forza Italia and its predecessors probably remain the closest Italy has to a typical centre-right party, despite its populistic or ‘personal party’ character (Diamanti Citation2007; McDonnell Citation2013). Fratelli d’Italia, formed in 2012 by critics of Berlusconi, also had both a nominative and, albeit weaker, ideological claim to being centre-right. It brings together both Christian democrat and liberal roots from Forza Italia and ‘post-fascist’ tendencies from Movimento Sociale Italiano/Alleanza Nazionale, though the latter had moved to the centre, or at least to a form of ‘proto-conservativism’ (Ignazi Citation2003).

The Lega as the Italian centre-right's functional yet dubious heir?

The Lega has long taken part in the ‘centre-right’ electoral coalition and, after 2018, dominated right-wing politics and government in Italy, having transformed itself into a national party that, by combining Euroscepticism and anti-immigration rhetoric, became an archetypal radical right party, participating in pan-European populist radical right transnational parties. Already in 2005, Ignazi (Citation2005, 333) could state that ‘the Northern League has shifted from its position as regionalist protest party to an actor more akin to other European extreme right parties, particularly in its authoritarian and antiimmigrant rhetoric’. Unlike many populist radical right parties, however, the Lega repeatedly joined governing coalitions and governed major Italian regions. Keen to please the longstanding ‘anti-politics’ section of its voters, it had played the role of unhappy subordinates and outsiders in previous centre-right administrations, often vocalising dissent on immigration and multiculturalism. While Tarchi (Citation2018) characterised them as a thorn in the side of the centre-right, Massetti (Citation2015, 486–87) argued that immigration ‘had turned the electoral advantage of the radical right vis-à-vis other parties (especially those on the centre-right) into an office advantage of the centre-right coalition’. In exchange, in 2008, the Lega received the Ministry of the Interior, ‘which became a crucial element in setting the government's direction on immigration and security policies’ to the disquiet of Catholic-minded sections of the centre-right (Tarchi Citation2018, 149). In this sense, the unusual electoral system has meant that centre-right voters had already become inoculated to voting – at least implicitly – for strident anti-immigration policies prior to the Lega winning pre-eminence over the nominatively centre-right coalition.

Rather than being tamed by the practicalities of office-holding, the Lega's actions in government after 2008 only served to make it more popular and more focused on its three key issues of federal reform, immigration and law and order (Albertazzi and McDonnell Citation2010). It also was able to retain its ‘one foot in, one foot out’ position in government, while plainly influencing policy (Albertazzi, McDonnell, and Newell Citation2011). At this point, the electoral manifestos of centre-right parties gave little attention to the issue of immigration, which Massetti (Citation2015) explains to be the result of the heterogenous positions between the parties and within the parties, with the sole exception of the Lega.

By the mid-2010s, Raniolo (Citation2016, 59) identified important shifts on the centre-right with together ‘Salvini for the Lega … Giorgia Meloni for the Fratelli d’Italia … and Silvio Berlusconi for Forza Italia’ representing the centre-right, with the former acting as leader and the latter ‘for the first time in 20 years … no longer the protagonist but, at best, the supporting actor’ (see also De Giorgi and Tronconi Citation2018). For Raniolo, this represented the culmination of, first, crisis – driven not least by the scandal-prone Berlusconi – and, then, radicalisation, so that ‘the internal equilibrium within the centre-right had shifted radically’. Thereafter, with Forza Italia discredited further following the breakdown of the Nazareno Pact with the centre-left Partito Democratico (Democratic Party), the Lega's ascendency in the centre-right coalition only rose further, to the point that it could seriously consider forming a government without other ‘centre-right’ parties and thus using its electoral advantage to its own office advantage. As such, the rise of the M5S neutered Berlusconi's post-Democrazia Cristiana niche of being the lynchpin of right-wing coalition-building in a context of bipolarism. Ultimately the M5S and Lega, united by populism, albeit in different forms (Caiani Citation2019), would form a government, even if the former held ‘ambiguous’ attitudes to migration and had claimed to side with migrants, blaming the ‘migration crisis’ on poor state management – though by 2018 in government this had transformed into a more explicitly nativist position. The popularity of the Lega and Salvini soared through 2019 reaching a peak in the polls of just under 40 per cent. Following Salvini's unsuccessful attempt to bring down the M5S-Lega coalition in August 2019, the Lega saw some decline in its support with concomitant growth in support for the equally anti-immigration FdI (Zapperi Citation2020).

‘Quiet’ and ‘loud’ politics

Our theoretical starting point for understanding policy outcomes is Freeman’s (Citation1995) analysis of the politics of immigration in liberal democrat states, in which he argues that migration polices are likely to be more expansive in terms of numbers admitted and inclusive in terms of rights extended than would seem to be consistent with more restrictive public attitudes to migration. He also sees this as leading to eventual policy convergence as ‘concentrated’ business interests advocate a more open approach to labour migration when compared to the more diffuse and necessarily less well-organised general public. In a later iteration of the argument, Freeman (Citation2006) does recognise scope for variation by policy type and distinct national contexts, but his argument remains that interests and the underlying distribution of costs and benefits are likely to determine migration policy. Lahav and Guiraudon (Citation2006) added nuance to this ‘gap’ argument by bringing in a more diverse range of actors, venues and stages of the policy process than simply national governments and policy outcomes while also arguing that national governments and various other bodies have circumvented public opinion – as well as other national institutions – through the use of intergovernmental governance at EU level, albeit with ‘contradictory and adhocratic’ motives and outcomes (Guiraudon Citation2003, 263). This presents the puzzle of why Italian migration policy has, seemingly, changed so radically – and further in line with public opinion – in recent years? Moreover, in terms of the focus of this special issue (Hadj Abdou et al, Citation2022), what was the role of the ‘centre-right’ in these changes?

We start by incorporating insights from the broader public policy literature and, in particular, four theoretical propositions. First, Culpepper (Citation2010) distinguished between two scenarios under which the relationship between business interests and public policy would vary: ‘quiet’ and ‘loud’ politics. In the ‘quiet’ scenario, policy makers allow business groups to influence public policy according to their interests, making use of their ‘technical expertise’. However, if the salience of the issue rises amongst the public – ‘loud politics’ – policy-makers have no choice but to defer to public attitudes on the issue. Second, Sharp (Citation1999), instead of analysing the role of interest groups, argues that public opinion sometimes matters in public policy but this is contingent on a number of factors such as institutional venues, distribution of attitudes, salience, and the emotionality or complexity of the issue, amongst other things. Third, Busemeyer, Garritzmann, and Neimanns (Citation2020) use the particular issue of education policy to test their theoretical extension of Culpepper's model by introducing a further division between ‘loud’ and ‘loud, but noisy’ politics, with the latter a result of a salient and highly polarised issue, resulting in regular policy changes.

Furthermore, we postulate that times of ‘quiet’ politics – enabled by low issue salience – leads not only to interest group influence but also to ‘policy drift’ (Hacker Citation2004). The concept of policy drift means that public policy can change without reform via gradual inaction and/or a failure to respond to changing contexts that render the original policy qualitatively different when implemented (a ‘zombie policy’). Given the more institutional nature of much public policy scholarship, the concept's influence has been high. Policy drift has typically been explained by multiple veto points or political resistance to change; we posit that a further explanation can be the low public issue salience of an issue combined with the quiescence of interest groups to the outcome of the drift. When the issue then increases in salience and ‘loud politics’ returns, the drift is more likely to stop and the policy be ‘reinstitutionalised’, i.e. brought back under literally interpreted and/or updated legislation that marks a radical rupture for the policy as implemented. This policy drift reversal (Shpaizman Citation2017) has been argued to be the result of it becoming ‘politically risky’ to maintain the drift; we argue that public issue salience plays a key role in this calculus, alongside public attitudes that, as we show below, are typically more stable.

The effect of the ‘migration crisis’ on Italian migration politics represents a novel, important and useful case to consider these theoretical propositions because of the level of politicisation of the issue. We make use of numerous data sources with formal accounts of shifts in both public and party positions regarding immigration and bring in the notion of public issue salience, considering its causes and effects as defined by the public opinion literature (see Dennison Citation2019 for a review), which has been shown to predict the vote share of radical right parties in western Europe (Dennison and Geddes Citation2019) via emotional activation of latent, more stable political attitudes and values and leading to a long list of political behaviours. Finally, the results of our analysis speaks to theoretical questions regarding the relationship between party positional changes and public attitudes more generally.

Italian migration governance

This section presents an overview of recent changes to Italian migration governance, divided into four periods: before the 2015 ‘crisis’; the initial reaction to the crisis; Salvini's 2018–2019 political use of the crisis as Interior Minister; and, responses during Giuseppe Conte's second administration after August 2018. There were already events and developments that were identified as containing crisis-like elements before 2015, including mass loss of life in the Mediterranean and clear legacies associated with Italy's status as a country of immigration from the late 1980s onwards (Caponio and Cappiali Citation2018). One such is that ‘irregularity’ and ‘illegality’ have been central to the governance of migration, to political framing of the issue and to interactions between migrants and the Italian state (Tuckett Citation2018).

Migration governance before 2015

outlines the main legislative developments in Italy since 1986. In spite of increased restrictions in the 1970s and 1980s (Colombo and Sciortino Citation2004), foreigners on Italian soil doubled in the 1980s and again in the 1990s, to 1.2 million. In response, for much of the 1990s and 2000s Italy operated a ‘back-door’ migration policy. Hundreds of thousands of migrants entered the country, many of them either were or, more usually, would become irregular because the original basis of their permission to enter on a short-term visa, for example, had expired (Zincone Citation1999). Their status was then corrected via regularisations, including that of the centre-right's 2002 Bossi-Fini Law when around 634,000 people had their status regularised. This approach initially stabilised the system but over time led to ‘policy drift’ because of a ‘de facto weakening’ of the efficiency of regularisation, itself partially the result of EU enlargement (Finotelli and Arango Citation2011, 502).

Table 1. Key policy actions throughout four recent time periods of Italian migration governance.

Freeman's (Citation1995, Citation2006) account of the dynamics of labour migration policy seemed to hold during the years of the ‘centre-right’ Berlusconi government where the coalition government contained the Lega Nord led by Umberto Bossi as well as the Alleanza Nazionale led by Gianfranco Fini. Bossi had declared during the campaign that he wanted to hear ‘the sound of cannons’ as a response to relatively small numbers of boat arrivals in the early 2000s (Geddes Citation2008). However, in government, Bossi was loyal to Berlusconi while the Lega Nord's influence was moderated by business and Christian democrat elements in the coalition that ‘succeeded in gaining the role of the moderate and bargaining-oriented component, thus acquiring far more relevance in the political arena’ (Ignazi Citation2003, 994). The Lega Nord had to manage its ‘dual identity’ combining a governing role locally, regionally and nationally with its characteristics as a movement (Albertazzi and McDonnell Citation2005). While anti-globalisation had become prominent in Lega Nord rhetoric prior to Salvini's leadership, there was a need to retain appeal to businesses in the party's northern heartlands where there was a continued demand for migrant labour. As Woods (Citation2009, 174) observes:

Many of the smaller businesses that the Lega is devoted to protecting turn to immigrants to meet their labour needs. This practical need for immigrant labour has led to the Lega adopting an interesting approach to immigration. In the context of northern identity and the protection of a way of life, the Lega has remained steadfast in its condemnation of global migration and the integration of Others into Padanian culture. But the Lega has accepted the notion of temporary or seasonal workers as a way to meet labour needs.

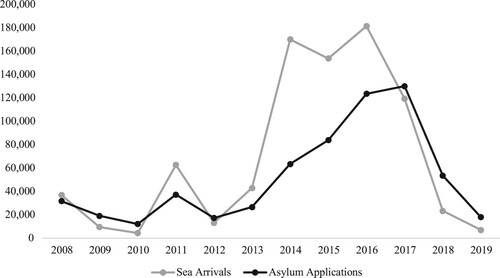

For migration management, the intention had been that Italian migration policy would be managed by annual decreti flussi (flow decrees), but these served more as ex post instruments to absorb migrants who were already in Italy. An effect of the financial crisis after 2008 was to lead to a reduction in work permits issued by both the Berlusconi government and its successor, the technocratic government led by Mario Monti between November 2011 and April 2013. In 2008, 172,000 work permits were issued. By 2019, this number had fallen to 12,850 for waged workers and a further 18,000 for seasonal and temporary workers. Moreover, 2008 also saw the adoption of the ‘Security Package’, proposed by the Lega's Interior Minister Roberto Maroni and approved by the centre-right coalition, which included ‘Urgent measures in the field of public security’ increasing a climate of criminalisation towards irregular migrants. However, it should be noted that the centre-left's 2002 Turco-Napolitano law also included securitising components that received strong support from FI and UdC (Massetti Citation2015). As shows, regular routes to Italy for non-EU migrants had effectively been closed before the ‘migration crisis’.

Figure 1. Quotas for non-EU migrant workers (Decreto Flussi). Sources: ISPI and Ministry of Interior.

Monti's technocratic government failed to build solid electoral support, precluding the opportunity to renew Italian migration policy. The 2013 general election was seen to herald the end of the Second Republic and potential emergence of a Third Republic given the breakthrough by the populist, anti-system Five Star Movement/Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S) (D’Alimonte Citation2013). In 2013, the M5S took 25.5 per cent of the vote, bringing to an end the transition to a bipolar party system. The centre-right lost almost 8 million votes while the centre-left lost 3.5 million and the new party of ex PM Mario Monti failed to make an impact. Wracked by scandal, the Lega had a disastrous performance at the 2013 general election with just 4.1 per cent of the vote. In December 2013, Salvini replaced Umberto Bossi as party leader.

The Lega saw modest growth in support at the 2014 EP elections when it got 6.1 per cent of the vote and four MEPs (including Salvini). While the performance was poor, the campaign was significant because it marked the birth of the Lega as a national and nationalist party in prototypical European radical right terms, replacing its previous focus on the status of northern Italy with attention to problems seen as Italy-wide, such as the negative effects of the Euro and immigration: ‘nowadays the enemy is Rome no longer: it is Brussels, European institutions, and the threat to the national sovereignty posed by the EU’ (Brunazzo and Gilbert Citation2017, 631).

Initial governance of the ‘crisis’: 2015–2018

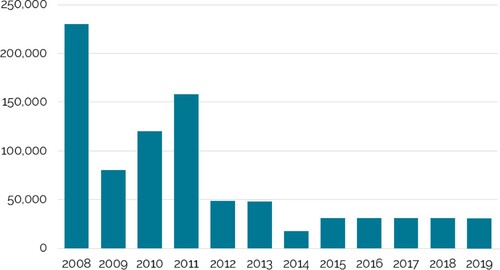

Despite the fact that most migrants to Italy enter via regular routes, images of desperate people clinging precariously to boats became the defining image of the ‘migration crisis’ – if not migration moreover – after 2015. Italy saw a significant increase in boat arrivals after 2014, although, as shows, there was soon after a steep decline in such arrivals as well as in asylum applications (because people could not actually get to Italy to make a claim). Numbers were falling long before Salvini became Interior minister in June 2018. The decline was a result of measures introduced by his predecessor from the centre-left Partito Democratico as Interior Minister, Marco Minniti, including controversial cooperation with Libya (as well as other transit countries) to stop onwards movement across the Mediterranean (Gargiulo Citation2018).

Two key points inform the ways in which this boat migration was politicised. The first is that it drew from existing understandings and framing of the immigration issue in Italy and associations with irregularity, illegality and abuse. The negative politicisation of migration was closely linked to these existing frames and their effects on migrants. Second, boat arrivals were also articulated as a European issue. On the day he was elected party leader in December 2013, Salvini declared that his number one objective was to reclaim sovereignty from Brussels (Albertazzi, Giovannini, and Seddone Citation2018). In the wake of the migration crisis and failed efforts at EU-wide solidarity, Salvini lambasted other EU member states and EU institutions as well as targeting NGOs engaged in search and rescue missions whom Salvini likened to traffickers, keeping ‘the Lega's populist and anti-systemic style but focusing on issues that are perceived as problems throughout Italy, such as the participation in the euro and mass immigration’ (Reuters Citation2019).

Salvini's governance of the ‘crisis’: 2018–2019

At the 2018 general election mainstream centre right and centre left parties saw their vote share crumble to less than third of the total. The big winners were the M5S, although the big post-election winners were the Lega who secured just over 17 per cent at the election but saw their vote share at the 2019 European Parliament elections soar to 33 per cent.

Migration policy under the ultimately short-lived Lega-M5S coalition in power between June 2018 and September 2019 was driven by Salvini as Interior Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, who stated upon appointment that Italy would no longer be ‘Europe's refugee camp’ and proceeded to dramatically increase both external and internal controls. In November 2018, the ‘Decree-Law on Immigration and Security’ – also known as the ‘Salvini decree’ – was passed, introducing a package of 42 articles. Among other things, this abolished humanitarian protection status for migrants, reduced barriers to stripping migrants of Italian citizenship, lengthened the naturalisation process, stopped asylum seekers from accessing reception centres and introduced a fast-track expulsion system for ‘dangerous’ asylum seekers (Pettrachin Citation2020; Geddes and Pettrachin Citation2020). The lower house passed the bill with 396 in favour and 99 opposed.

Typically, in January 2019, a German NGO-operated ship, SeaWatch 3, that had rescued 47 migrants attempted to enter Italian ports, which Salvini described as a provocation and to which he refused to allow access, tweeting #portichiusi (‘closed ports’) and adding that he was happy to send whatever aid was necessary to the ship. M5S leader Luigi di Maio echoed the sentiment, inviting the ship to instead sail to Marseille (Reuters Citation2019). In June 2019, new, so-called security decrees targeted NGOs by threatening fines of up to €1 million for ships ‘ignoring bans and limitations’ on accessing Italian waters, with seizure of the ships of repeat offenders. The text of the measures openly and explicitly contravened the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, leading to a war of words between the UN and the Italian government (Borelli Citation2020), reflective of an openly bombastic and non-conciliatory policy approach of the period, aimed directly at public opinion.

Migration governance during the Conte II government

In August 2019, Salvini collapsed the M5S-Lega coalition government led by Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte in what proved to be an unsuccessful bid to engineer a general election and profit from his strong vote share in the 2019 EP elections and soaring opinion poll ratings. Instead, the M5S and PD formed a new government, again led by Conte. The M5S and PD, first, agreed to review Salvini's ‘security decrees’ in line with concerns expressed by President Mattarella and, second, appointed a non-political technocrat who had worked for decades in the Ministry of the Interior, Luciana Lamorgese, as Interior Minister in an attempt to depoliticise the immigration issue (Pietromarchi Citation2019), in direct contrast to Salvini's strategic politicisation. Soon after, an NGO ship carrying 82 migrants rescued at sea was allowed to dock in Lampedusa, with the PD indicating that the migrants would be shared among European countries (ibid). However, pro-migration Italian legal groups bemoaned the likelihood that, even should Salvini's reforms be scrapped, the underlying logic of blocking migrants was one that descends from and is reinforced by the EU. Conte resuscitated rhetoric looking to reform the EU's Dublin system with greater solidarity between member states while Salvini, now out of office, claimed the policy volte-face regarding NGO ships showed that the new government ‘hate the Italians’.

Political supply

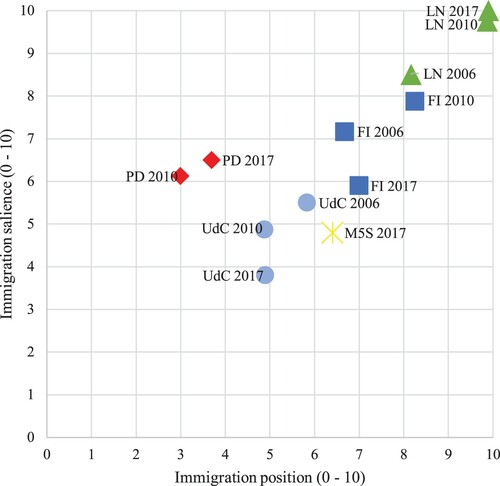

To explain these changes in policy, we first turn to formally identifying trends in the immigration preferences and priorities of Italian parties and particularly those of the ‘centre right’ coalition. First, we use the Chapel Hill Experts Survey (CHES; Polk et al. Citation2017). The CHES estimates party positions and the salience, primarily as the average score given by a panel of experts on 0–10 scales, on a range of policy issues for national parties in a variety of European countries, including Italy. The survey was first conducted in 1999, with subsequent waves in 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2017.

We show that effects of the ‘migration crisis’ on the Italian party system – in terms of parties’ relative policy positions and saliences – has generally been highly limited and, in some cases, counterintuitive. We suggest that this is because earlier crises in Italian politics had already fragmented and undermined mainstream right-wing parties, meaning that populist right-wing parties were already well-established in Italy prior to 2015. Although the ‘migration crisis’ had minimal effects on parties’ relative positions and saliences, it dramatically transformed their relative popularity and governing status as the fairly static political supply interacted with the highly volatile political demand that we outline after. The very significant exception to this static supply during the ‘migration crisis’ is in geographic rather than policy spatial terms, i.e. the expansion into southern Italy of the re-branded Lega.

shows four key changes in party immigration stances between 2006 and 2017. First, the Lega Nord radicalised their immigration position and its salience between 2006 and 2010 and have stayed put – albeit in the most radical position possible – thereafter. Second, FI also radicalised its immigration position and its salience, but this was between 2006 and 2010, after which they have actually significantly softened and quietened on the matter. Third, what was the primary Christian democrat party – Unione di Centro – became more pro-immigration between 2006 and 2010 and then did not change its position by 2017. It continuously devoted less salience to the topic during that time. Finally, the M5S were first included in the 2014 wave of the CHES.Footnote6 However, that wave did not estimate immigration salience, only estimating immigration position. In that year, the M5S were measured as relatively pro-immigration (4.3) compared to their 2017 score of 6.4. This increased anti-immigration positioning by the M5S – aside from the more minor shift by the relatively pro-immigration PD – represents the only significant shift towards a more anti-immigration policy by any major Italian party during the migration crisis. The 2019 CHES showed practically no changes in the immigration positions or salience of each of the parties.Footnote7

Figure 3. Immigration policy and salience of selected Italian parties, 2006–2017.

Notes: Polk et al. (Citation2017). Each score represents average response of 15 experts on 0–10 scale. Source: Polk et al. (Citation2017).

Three additional trends in Italian politics are noteworthy at this point. First, the broad left-right and GAL-TAN (Green-Alternative-Libertarian and Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist) positioning of both the Unione di Centro and FI have remained largely stable across every wave of the CHES since 1999, suggesting broad ideological stability. Second, the same left-right and GAL-TAN positioning of the Lega Nord changed radically between 1999, when they scored 7.0 and 6.2 respectively on the two measures, and 2006, when they scored 8.7 and 8.8 on the two measures. During that time, the Lega Nord also became more Eurosceptic, from 3.2 to 1.5, and gave more salience to European integration, from 2.1 to 6.7, a score that increased to 8.9 by 2014, after the Eurozone crisis.

Political demand

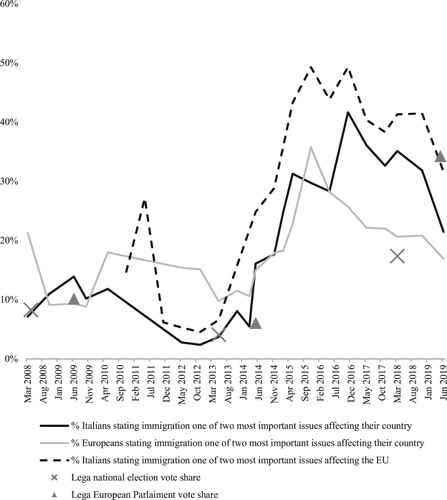

With the relative lack of change in political supply during the years of the ‘migration crisis’, at least in terms of policy positions, established, we now consider how the ‘migration crisis’ affected Italian migration politics on the demand side. We show that the public issue salience of immigration grew from being very much a secondary issue between 2008 and 2014 to, thereafter, being a primary issue, both in terms of what Italians see as salient for Italy and for the EU. This salience was more durable than in other European countries, while Italian attitudes to immigration actually grew steadily more positive. Notably, support for the Lega came after rather than preceded this growth in public salience. Finally, the dynamics of demand have important geographic components, with salience being evenly spread but attitudes being far more negative in the south, making the area fertile electoral ground for the, now national, Lega.

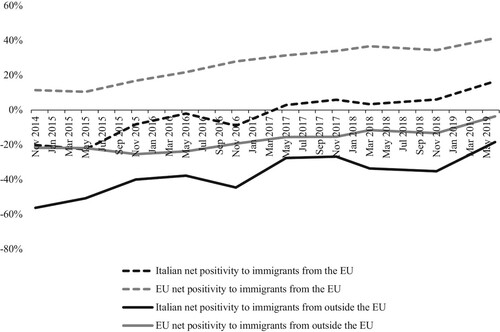

As shown in , Italian attitudes to both EU and non-EU immigrants have consistently become more positive since the ‘migration crisis’. By June 2019 more Italians held a positive view of EU immigrants than a negative one, while the net negativity towards non-EU immigrants was significantly diminished. In both of these senses, Italian trends have been the same as pan-EU trends, however, with a lower constant on both measures in Italy (Dennison and Geddes Citation2019).

Figure 4. Italian and EU attitudes to immigration from outside the EU and other EU member states.

Notes: Eurobarometer, 2014–2019. All 28 EU member states surveyed. ‘Please tell me whether each of the following statements evokes a positive or negative feeling for you. Immigration of people from other EU Member States / Immigration of people from outside the EU’. Net positivity = Very positive + Fairly positive − Fairly negative − Very negative.

We find little evidence of attitudinal polarisation during the same period. In November 2014, responses regarding immigration of people from other EU member states had a standard deviation of 0.14, in June 2019 this had risen to 0.16; a minor change when compared to the change in net positivity. Second, the change in standard deviation of responses regarding ‘immigration from outside the EU’ did not change at all, staying level at 0.15.

In , we can see that between 2014 and 2019 the percentage of Italians stating that immigration is one of the two most important issue affecting their country increased markedly, from around 5 per cent to a peak of over 40 per cent in May 2017, before partially declining. Prior to 2014 it had been steadily declining. We can see that this figure followed a similar trajectory to the pan-European trajectory, until 2016 when the public salience of immigration began to climb again. We conclude that the ‘migration crisis’, in the Italian popular mindset, lasted longer than elsewhere in Europe. We also see that when Italians are asked about the most important issue affecting the EU – rather than their own country – they are more likely to respond with ‘immigration’, a common trend across Europe (Eurobarometer, 2014–2019). Finally, we see that the increase in Lega vote share followed the salience of immigration, a trend that has been noted across western Europe (Dennison and Geddes Citation2019; Dennison Citation2020).

Figure 5. The salience of immigration amongst Italian and European citizens and the national and European Parliament election vote shares of Lega Nord, 2008–2019.

Notes: Eurobarometer, 2009–2019. All 28 EU member states surveyed. Around 1000 respondents per member state. What do you think are the two most important issues facing (our country/the EU) at the moment?

Finally, given the strong geographical aspect to both voting – with Lega still doing far better in the north – and migration – overwhelmingly also in the north but with boat landings in the south – we also consider how attitudes vary by region. As we can see in , southern Italians have considerably more negative views of immigration, both from in and out of Europe. Despite that, the salience of immigration is fairly even in the country, and even slightly higher in the north (a trend that had been more noticeable in the past). These seemingly incongruous trends actually reflect those across Europe partially due to the ordinal nature of the salience question which is naturally affected by the far higher salience of unemployment in the south. Italians remain far more dissatisfied with their democracy than other Europeans, a long-term trend and both a cause and effect of the highly fragmented and volatile party system.

Table 2. Regional variation in attitudes to immigration, Europe and democracy.

Italian electoral dynamics during the ‘migration crisis’: static supply meets dynamic demand?

The centrality of the transformation of public issue salience of immigration to explaining the rise to prominence within the nominal centre-right of the Lega and, thereafter, the departure from the previous policy equilibrium regarding immigration is highlighted by voting dynamics at the 2018 Italian election. According to the 2018 ITANES Italian election panel survey, 62 per cent of Italians believed Italy received too many immigrants, when measured as the percentage of respondents who responded with less than four on a 1–7 scale asking whether Italy received too many (1) or ‘we could easily take more immigrants’ (7). Of these voters, 40 per cent voted for the M5S and only 20 per cent voted for Lega. However, when we only consider the 22 per cent of voters who responded that immigration was one of the two most important issue affecting Italy, Lega and the M5S received an equal proportion of voters, around 30 per cent each. When only those who believe Italy is already receiving too many immigrants and that immigration was one of the two most important issue affecting Italy are included, Lega won the most votes of any party. Given that only 13 per cent of the ITANES sample report voting Lega in 2018, compared to 36 per cent reporting voting M5S – an under- and over-estimate, respectively – Lega's support amongst these attitudinal segments is likely to be higher in the population than in the sample. Lega's actions when in government, and in control of the Ministry of the Interior particularly, almost certainly secured the support of a significantly larger pool of these voters from M5S who could, and did, echo Salvini's rhetoric and support his policy packages.

Conclusion

This article considered how the ‘migration crisis’ has affected Italian immigration politics, particularly that of the centre-right. While acknowledging the complexity of this relationship, we argued for the existence of a number of key trends. First, the rise in public issue salience regarding immigration, resulting from the politicisation of irregular arrivals by sea and longer-standing framing of migration as irregular, illegal and abusive into Italy, which was integral to the already transformed Lega's ability to campaign successfully nationally and dominate the nominal centre-right coalition. Second, the domestic imposition while in government between June 2018 and September 2019 by the Lega of considerably more repressive migration policies. These trends conform to our theoretical expectations of the relative power of interest groups and public opinion over public policy being contingent on public issue salience, which we show to be the most plausible determinant of variation in migration politics, rather than variation in public attitudes or party positions, during the period. We further posited that an explanation for the previous policy drift was the low public issue salience of the issue.

We identified four periods of Italian migration policy for the purposes of this analysis. First, during the period before the ‘migration crisis’ we saw lower public interest and policy ‘toughness’ that often later gave way to regularisations or was balanced by certain rights-based initiatives. Second, in the period 2015–2018 we saw increasing public interest and a centre-left government attempting to reassert external control via deals with Libya, for example, though few internal changes. In short, an attempt to return to the status quo ante. Third, during Salvini's tenure in the Ministry of the Interior, we identified harsher rhetoric and significantly harsher internal policies. Finally, with the creation of the PD-M5S coalition, there were signs of increased leniency albeit in a highly politicised and unstable context.

In terms of policy supply, however, the CHES data clearly indicates that the migration crisis had little impact in terms of party positions on immigration or the emphasis they gave to those issues. The Christian democrat parties became more pro-immigration while FI placed less emphasis on immigration than it had in 2010. The Lega continued to hold a highly anti-immigration position and continued to campaign heavily on this issue, though this was already the case by 2010 and followed its marked radicalisation in the early 2000s. The only party to take on a more anti-immigration position during the ‘migration crisis’ was the M5S. For followers of Italian politics this may seem counterintuitive as the focus on immigration in Italian political rhetoric has undoubtedly increased in the past five years. We argue that this is primarily because of the increased electoral support, visibility and office-holding of parties – primarily the Lega – that were already highly anti-immigration, at least in theory, and that their increased popularity is primarily demand-driven as the public issue salience of immigration has increased markedly. In terms of political demand, we show an increase in Italian positivity to both EU and non-EU immigration during the period, in line with pan-European trends. The salience of immigration mattered highly to the electoral and policy changes during the ‘migration crisis’. Previously, the high salience of immigration was the preserve of the north, but during the crisis it also rose in the south, where attitudes to migrants had long been more negative, the combination of which created a fertile electoral soil for the Lega to build southern support. The demand side figures also show how the issues of immigration and Europe had the potential to become fused via notions of accountability and Euroscepticism. Moreover, the slow and lagged (compared to rates of irregular arrivals) decline in the salience of immigration suggests that ‘crises’ in the public mind take time to fade away.

Theoretically, it seems that the ‘migration crisis’ transformed Italian migration politics from being (relatively) ‘quiet’ to ‘loud’ to use Culpepper’s (Citation2010) terminology and thus breaking the logic of Freeman (Citation1995) and the policy drift of Hacker (Citation2004), even if both had already been under strain in the decade prior. Immigration is, however, by no means a new topic in Italian political debate, even if it had never before received such salience relative to other issues. As such, we might conclude that immigration is intermittently a high salience issue and we should expect lability (see Breunig and Koski Citation2018) in future migration policy, something we are already seeing in the short time since Salvini was removed from the position of Interior Minister. The scenario of ‘capture’ by organised interests is therefore likely to be over, along with policy drift, so long as the public issue salience remains high.

Acknowledgements

Thanks Dr Andrea Pettrachin for research assistance with this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Democrazia Cristiana (a member from 1976 to 1994); Partito Popolare Italiano (1994–2002); Centro Cristiano Democratico (1994–2002); Cristiani Democratici Uniti (1995–2002); Rinnovamento Italiano (1998–2004); the previous incarnation of Forza Italia (1994–2009); Unione Democratici per l’Europa (1999–2015); Il Popolo della Libertà (2009–2013); and Nuovo Centrodestra (2013–2017).

2 CD places itself in the centre-left coalition and is perhaps best described as ‘Christian left’.

3 Three years earlier, it classified the Unione di Centro as ‘Christian democrat’ and the Forza Italia, Fratelli d’Italia and Nuovo Centrodestra as ‘conservative’.

4 A centrist group of parties lead by a member of the Alternative Popolare, but which formed a part of the centre-left electoral coalition.

5 For the 2013 election, TMP classified Unione di Centro as Christian democrat and Fratelli d’Italia, Il Popola della Libertà (Forza Italia's predecessors) and Lista Lavoro e Libertà as ‘conservative’.

6 FdI were also first included in 2014 and, unsurprisingly, already took a highly anti-immigration position (8.75).

7 Lega (9.9, 9.9); FI (7; 5.8); FdI (9.8; 9.9); M5S (6.5; 5.5); PD (3.1; 6.8).

References

- Albertazzi, Daniele, Arianna Giovannini, and Antonella Seddone. 2018. “‘No Regionalism Please, We Are Leghisti!’ The Transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the Leadership of Matteo Salvini.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (5): 645–671.

- Albertazzi, Dr Daniele, and Duncan McDonnell. 2005. “The Lega Nord in the Second Berlusconi Government: In a League of Its Own.” West European Politics 28 (5): 952–972.

- Albertazzi, Daniele, and Duncan McDonnell. 2010. “The Lega Nord Back in Government.” West European Politics 33 (6): 1318–1340.

- Albertazzi, Daniele, Duncan McDonnell, and James L. Newell. 2011. “Di Lotta e Di Governo: The Lega Nord and Rifondazione Comunista in Office.” Party Politics 17 (4): 471–487.

- Ambrosini, Maurizio, and Nazareno Panichella. 2016. “Immigrazione, occupazione e crisi economica in Italia.” Quaderni di Sociologia 72 (December): 115–134.

- Bartolini, Stefano, Alessandro Chiaramonte, and Roberto D’Alimonte. 2004. “The Italian Party System between Parties and Coalitions.” West European Politics 27 (1): 1–19.

- Borelli, Silvia. 2020. “Pushing Back Against Push-Backs: A Right of Entry for Asylum Seekers Unlawfully Prevented from Reaching Italian Territory.” Diritti Umani e Diritto Internazionale, no. 1/2020.

- Breunig, Christian, and Chris Koski. 2018. “Interest Groups and Policy Volatility.” Governance 31 (2): 279–297.

- Brunazzo, Marco, and Mark Gilbert. 2017. “Insurgents against Brussels: Euroscepticism and the Right-Wing Populist Turn of the Lega Nord since 2013.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 22 (5): 624–641.

- Bull, Anna Cento. 2010. “Addressing Contradictory Needs: The Lega Nord and Italian Immigration Policy.” Patterns of Prejudice 44 (5): 411–431.

- Busemeyer, Marius, Julian Garritzmann, and Erik Neimanns. 2020. A Loud but Noisy Signal?: Public Opinion and Education Reform in Western Europe. Cambridge Studies in the Comparative Politics of Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/loud-but-noisy-signal/2BE73266F8A69275E7D14FA784B7FFC0.

- Caiani, Manuela. 2019. “The Populist Parties and their Electoral Success: Different Causes Behind Different Populisms? The Case of the Five-Star Movement and the League.” Contemporary Italian Politics 11 (3): 236–250.

- Caponio, Tiziana, and Teresa M. Cappiali. 2018. “Italian Migration Policies in Times of Crisis: The Policy Gap Reconsidered.” South European Society and Politics 23 (1): 115–132.

- Colombo, Asher, and Giuseppe Sciortino. 2004. “Italian Immigration: The Origins, Nature and Evolution of Italy’s Migratory Systems.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 9 (1): 49–70.

- Culpepper, Pepper. 2010. Quiet Politics and Business Power: Corporate Control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- D’Alimonte, Roberto. 2013. “The Italian Elections of February 2013: The End of the Second Republic?” Contemporary Italian Politics 5 (2): 113–129.

- De Giorgi, Elisabetta, and Filippo Tronconi. 2018. “The Center-Right in a Search for Unity and the Re-emergence of the Neo-Fascist Right.” Contemporary Italian Politics 10 (4): 330–345.

- Dennison, J. 2019. “A Review of Public Issue Salience: Concepts, Determinants and Effects on Voting.” Political Studies Review 17 (4): 436–446.

- Dennison, James. 2020. “How Issue Salience Explains the Rise of the Populist Right in Western Europe.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 32 (3): 397–420.

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes. 2019. “A Rising Tide? The Salience of Immigration and the Rise of Anti-Immigration Political Parties in Western Europe.” The Political Quarterly 90 (1): 107–116.

- Diamanti, Ilvo. 2007. “The Italian Centre-Right and Centre-Left: Between Parties and ‘the Party’.” West European Politics 30 (4): 733–762.

- Einaudi, Luca. 2007. Le politiche dell’immigrazione in Italia dall’Unità a oggi. Roma: Laterza.

- Emanuele, Vincenzo, and Aldo Paparo. 2018. Gli Sfidanti al Governo: Disincanto, Nuovi Conflitti e Diverse Strategie Dietro Il Voto Del 4 Marzo 2018. Rome: Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali.

- Finotelli, Claudia, and Joaquín Arango. 2011. “Regularisation of Unauthorised Immigrants in Italy and Spain: Determinants and Effects.” Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 57 (3): 495–515. doi:https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.251.

- Freeman, Gary. 1995. “Modes of Immigration Politics in Liberal Democratic States.” International Migration Review 29 (4): 881–902. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2547729.

- Freeman, Gary. 2006. “National Models, Policy Types, and the Politics of Immigration in Liberal Democracies.” West European Politics 29 (2): 227–247.

- Gargiulo, Enrico. 2018. “Una Filosofia Della Sicurezza e Dell’ordine. Il Governo Dell’immigrazione Secondo Marco Minniti.” Meridiana 91: 151–173.

- Geddes, Andrew. 2008. “Il Rombo Dei Cannoni? Immigration and the Centre-Right in Italy.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (3): 349–366.

- Geddes, Andrew, and Andrea Pettrachin. 2020. “Italian Migration Policy and Politics: Exacerbating Paradoxes.” Contemporary Italian Politics 12 (2): 1–16.

- Guiraudon, Virginie. 2003. “The Constitution of a European Immigration Policy Domain: A Political Sociology Approach.” Journal of European Public Policy 10 (2): 263–282.

- Hacker, Jacob S. 2004. “Review Article: Dismantling the Health Care State? Political Institutions, Public Policies and the Comparative Politics of Health Reform.” British Journal of Political Science 34 (4): 693–724.

- Hadj Abdou, L., T. Bale, and A. Geddes. 2022. “Centre-Right Parties and Immigration in an Era of Politicisation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (2): 327–340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853901.

- Ignazi, Piero. 2003. Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ignazi, Piero. 2005. “Legitimation and Evolution on the Italian Right Wing: Social and Ideological Repositioning of Alleanza Nazionale and the Lega Nord.” South European Society and Politics 10 (2): 333–349.

- Lahav, Gallya, and Virginie Guiraudon. 2006. “Actors and Venues in Immigration Control: Closing the Gap Between Political Demands and Policy Outcomes.” West European Politics 29 (2): 201–223.

- Mair, Peter, and Cas Mudde. 1998. “The Party Family and Its Study.” Annual Review of Political Science 1 (1): 211–229.

- Massetti, Emanuele. 2015. “Mainstream Parties and the Politics of Immigration in Italy: A Structural Advantage for the Right or a Missed Opportunity for the Left?” Acta Politica 50 (4): 486–505.

- McDonnell, Duncan. 2013. “Silvio Berlusconi’s Personal Parties: From Forza Italia to the Popolo Della Libertà.” Political Studies 61 (S1): 217–233.

- Pastore, Ferruccio. 2016. “Zombie Policy: Politiche Migratorie Inefficienti Tra Inerzia Politica e Illegalità;” Il Mulino, no. 4/2016.

- Pettrachin, Andrea. 2020. “Opening the ‘Black Box’ of Asylum Governance: Decision-Making and the Politics of Asylum Policy-Making.” Italian Political Science Review / Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 50 (2): 191–212.

- Pietromarchi, Virginia. 2019. “With Salvini Gone, What’s Next for Italy’s Migration Policy?” Al Jazeera, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/09/salvini-italy-migration-policy-190910121122318.html.

- Polk, Jonathan, Jan Rovny, Ryan Bakker, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Jelle Koedam, et al. 2017. “Explaining the Salience of Anti-Elitism and Reducing Political Corruption for Political Parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Data.” Research & Politics 4 (1): 2053168016686915.

- Raniolo, Francesco. 2016. “The Center-Right’s Search for a Leader: Crisis and Radicalization.” Italian Politics 31 (1): 59–79.

- Reuters. 2019. “Italy Pressures Dutch and French over Storm-Tossed Migrant Rescue Ship.” Reuters, January 25. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-italy-idUSKCN1PJ18X.

- Sharp, Elaine. 1999. The Sometime Connection: Public Opinion and Social Policy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Shpaizman, Ilana. 2017. “Policy Drift and Its Reversal: The Case of Prescription Drug Coverage in the United States.” Public Administration 95 (3): 698–712.

- Tarchi, Marco. 2018. “Voters Without a Party: The ‘Long Decade’ of the Italian Centre-Right and Its Uncertain Future.” South European Society and Politics 23 (1): 147–162.

- Tuckett, Anna. 2018. Rules, Paper, Status: Migrants and Precarious Bureaucracy in Contemporary Italy | Anna Tuckett. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Urso, Ornella. 2018. “The Politicization of Immigration in Italy. Who Frames the Issue, When and How.” Italian Political Science Review / Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 48 (3): 365–381.

- Volkens, Andrea, Tobias Burst, Werner Krause, Pola Lehmann, Merz Matthieß Theres, Regel Nicolas, Weßels Sven, and Lisa Bernhard / Zehnter. 2020. The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2020a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2020a.

- Woods, Dwayne. 2009. “Pockets of Resistance to Globalization: The Case of the Lega Nord.” Patterns of Prejudice 43 (2): 161–177.

- Zapperi, Cesare. 2020. “Se si votasse oggi alla Camera? Salvini e Meloni da soli non bastano, serve Forza Italia.” Corriere della Sera. June 6, 2020. https://www.corriere.it/politica/20_giugno_06/se-si-votasse-oggi-salvini-meloni-non-bastano-serve-forza-italia-a11b74f8-a760-11ea-b358-f13973782395.shtml.

- Zincone, Giovanna. 1999. “Illegality, Enlightenment and Ambiguity: A Hot Italian Recipe.” South European Society and Politics 3 (3): 45–82.