ABSTRACT

With the launching of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia have been confronted with both growing business opportunities and emerging challenges. How do ethnic Chinese businesses and their associations respond to the BRI, and by extension, a rising China? How do transnationalism and the nation-states shape their engagement strategies? What are the implications of the Southeast Asian experience for an understanding of diaspora transnationalism? Drawn upon empirical studies conducted in Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines, and by examining the emergence of the new structural characteristics of Chinese business associations, we argue that these associations have formed institutionalised transnational interactions with China through a variety of mechanisms to facilitate cross-border flows of capital, goods, people, and information. Resultant from various policies instituted by the Southeast Asian states, this economic transnationalism has not led to the dilution of the national identity and political loyalty of ethnic Chinese towards their respective countries. We conclude that the institutionalised transnationalism has operated within a ‘dual embeddedness’ structure in which the state is involved as a key network node in the transnational socio-economic field connecting China and the region.

Introduction

There are numerous studies on the important role of diaspora Chinese since China’s reform and opening-up in 1978, with ethnic Chinese from outside of mainland China contributing to about 70% of foreign direct investment to China and its international trade (Peterson Citation2013; Long and Yiwei Citation2018; Martínez-Zarzoso and Rudolf Citation2020). Most of these studies, however, were based upon data before the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has constituted China’s most significant diplomatic and economic strategy, covering over 4 billion population in more than 60 nations. According to the CIMB ASEAN Research Institute (Citation2018), BRI projects in ASEAN countries amount to more than US$739 billion, including US$98.5 billion in Malaysia, US$70.1 billion in Singapore, and US$9.4 billion in the Philippines (Liu Citation2022a).

While Southeast Asia’s attitudes toward a rising China have been described as ‘fraught … anguished, and complex’ (Strangio Citation2020, 5–7), the significant changes brought about by China and their corresponding socio-economic influences warrant a closer (re)examination of the Chinese communities in the region, including their new strategies of engaging a more powerful (ancestral) homeland and the role of the state in regulating their transnationality. Focusing on the response to the BRI by the region’s Chinese business associations, this article analyses the emerging characteristics of ethnic Chinese transnational networks in the new era.

It has been argued that ‘transnational Asia’ (Liu Citation2018) has a profound historical and cultural foundation and a major salient characteristic of Chinese associations in post-war Southeast Asia has been their transnationality in facilitating the flows of goods, capital and ideas. The transnational engagement with China and among the diasporas has played an important part in the globalisation of Southeast Asia. With the world changing rapidly, China’s rise has developed new patterns amongst the Chinese diaspora transnationals, which is reflected in their diversity, mobility and networks, as described by some studies of Chinese diasporas in different geographical areas, like Australia, Africa and Europe (see Gao Citation2022; Park Citation2022; Wu Citation2022 in this issue). In the context of Asia, and with the BRI’s inception, Chinese diaspora voluntary organisations (especially business associations) are proactively engaged in building or renewing connections with China. The large body of existing literature on the BRI tends to focus on geo-politics, infrastructure, and trade, and it rarely explores the transnational process from a diaspora perspective. They mainly examine China’s political and economic interests and are concerned with new (mainland) Chinese capitalism behind the transnational strategy, paying lesser attention to the role of ethnic Chinese businesses, which are considered only as one of many related partners in China’s overseas investment projects, rather than as central foci (Flinta and Zhu Citation2019; Liow, Liu, and Gong Citation2021; Liu, Tan, and Lim Citation2022). Moreover, while the studies of Chinese associations in Southeast Asia have been undertaken from multiple perspectives, they are seldom put into the context of the BRI and the larger ramifications for the Chinese diaspora. Collectively, Southeast Asian Chinese account for about 80% of diaspora Chinese population in the world. Although their share of population in the region is only about 4–6%, their contribution to the region’s economic and trade activities is much larger (Gomez and Hsiao Citation2013; Priebe and Rudolf Citation2015). The integration of ethnicity, business, investment and the political economy, therefore, will shed new lights to the changing characteristics of not only a rising China but also the diaspora Chinese.

Focusing on the intersections of Chinese business associations in Southeast Asia and the BRI, this article employs Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines as case studies for three reasons. Firstly, they represent different levels of economic development and diverse patterns of ethnic relationship, with Singapore as a developed economy, Malaysia as a middle-income nation and the Philippines being somewhat behind. The Chinese account for different percentages in the three multi-racial countries, 75%, 26% and 2%, respectively, and the three countries’ Chinese population ranked number 3, 5, and 7, respectively among 130 countries in the world with a sizeable diaspora Chinese population (Li and Li Citation2013). The diverse economic and racial patterns thus afford an illuminating picture of the interplay between ethnicity, economy and the state. Secondly, all three nations have actively engaged with the BRI, from their own nations’ interests, through serving as a financial and transport hub (Singapore), a site of massive infrastructure projects (Malaysia), and bilateral trade and investment (the Philippines). The growing presence of the BRI in these countries, just like in other ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) nations, provides a major platform through which Chinese business associations interact with the local and Chinese states and reconstruct ethnic identities. Thirdly, ethnic Chinese in the three countries have well-developed voluntary organisations, represented mainly by business associations which exerted considerable influence on ethnic Chinese communities (Santasombat Citation2017). While their roles continue to evolve and have been subject to the growing power of the nation-states, business associations remain as a major force in representing ethnic Chinese communities locally as well as between their respective nations and China on issues pertaining to commerce, trade and investment.

This essay addresses the following questions: How have ethnic Chinese business associations structurally responded to various transnational forces linked with the BRI in their respective nations and the region? What are the dynamics, patterns and mechanisms of transnational networks that these associations have constructed with China institutionally? What roles have the states (in China and Southeast Asia) played in the transnational engagement of the diaspora? What implications can be drawn for an understanding of the entanglement of transnationalism, ethnic and national interests and the state at a time of China rising?

From a theoretical perspective, this article engages the growing literature on transnationalism and its critique. Since the 1990s transnationalism has become a main paradigm in migrant studies, such as refugees, immigrant entrepreneurs, migrants’ networks (e.g. Koser Citation2007; Ren and Liu Citation2019). In recent years, the role of immigrant organisations has received growing attention in transnationalism studies. Scholars have found that immigrant transnationalism has been channelled through organisations as a collective force to contribute to the improvement of the homeland’s economic and social development, or as an immigrant strategy to enhance their own transnational ability, whether historically or currently (Portes and Fernández-Kelly Citation2016; Lamba-Nieves Citation2018). Immigrant organisational transnational practices vary significantly across particular communities, nationalities, countries and ethnic groups (Moya Citation2005; Mügge Citation2011; Lampert Citation2014; Portes and Fernández-Kelly Citation2016). However, these studies have concentrated mainly on migrant organisations in Europe and the United States. Although there are some studies on immigrant organisations in an Asian context (e.g. Ren and Liu Citation2015; Zhou and Liu Citation2016; Santasombat Citation2017; Zhou Citation2017), they do not scrutinise the recent political and economic environments within which a rising China shapes the region in an unprecedented manner. As Guo (Citation2022) pointed out in this special issue, the new age is changing the nature of Chinese diasporas, and we need to reimagine and develop new analytical constructs for Chinese diasporas transnationalism. Guo characterises new Chinese transnationals in terms of hypermobility, hyperdiversity and hyperconnectivity, in relation to practices and identities. This article examines the emerging characteristics of organised transnationalism in the Asian context by developing the concept of institutionalised transnationalism as an analytical tool to explore the transnationality of ethnic Chinese business associations in Southeast Asia.

Institutionalised transnationalism in this study refers to regular and constant cross-border social and economic practices that have been institutionalised through governmental, business, and societal institutions for the purpose of promoting mutually beneficial agendas. With the BRI’s inroads in Southeast Asia, ethnic Chinese business associations have been involved in this transnational project thanks in part to their ethnic and cultural linkages with the (ancestral) homeland. The number of participants in ASEAN Overseas Chinese Entrepreneur Convention, held in Yunnan province since 2013, increased steadily. By 2019 more than 400 overseas Chinese organisations and nearly 5000 diaspora Chinese entrepreneurs have established links with Yunnan (Kunming Daily Citation2018, Citation2019). Both Chinese and Southeast Asian governments have engaged business associations as interlocutors to seize upon opportunities presented by the BRI, which has, in turn, led to the establishment and strengthening of various mechanisms and structures.

Existing literature has identified two types of relationships between the state and transnationalism. One is a passive mode in which states respond to diasporas’ transnational practices, and the other is an active one in which states initiate, maintain and promote diasporas’ transnational activities. The arrival of Chinese migrants in Australia and Africa in the last thirty years is a typical manifestation of the state’s involvement in transnationalism (Gao Citation2022 and Park Citation2022 in this issue). These relationships have been conceptualised variously as state transnationalism, state-led transnationalism or new modes of transnational governance (Margheritis Citation2007; Portes, Escobar, and Radford Citation2007; Weeks and Weeks Citation2015; Caggiano Citation2018). An emerging consensus is that states can and do serve as active instruments to advance the transnationalism agenda within and beyond their boundaries (Chin and Smith Citation2015). To distinguish our position from the above discussions, we emphasise the formation of state-centric transnational network, highlighting the fact that the Chinese state is not only involved as a dynamic element in the institutionalised transnationalism, but also enters into transnational networks as a connective node and a key player.

Data for this study were collected from multi-sited fieldwork conducted in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur (KL) in Malaysia, and Manila in the Philippines from May 2018 to June 2019. Singapore, KL and Manila are key political and commercial centres with heavy ethnic Chinese concentrations. We scrutinise twenty-nine major Chinese business associations which have been extensively engaged in transnational practices centred around the BRI. These associations were selected to achieve a sampling of the different structural types, including 5 federated ones (2 from Singapore, 2 from Malaysia, 1 from the Philippines), 17 regional (4 from Singapore, 5 from Malaysia, 8 from the Philippine), and 7 newly established (5 from Malaysia, 2 from the Philippine). Apart from analysing their materials (printed, online, or unpublished), archival and media data, we also use mixed methods, including in-depth interviews and participatory observations. The interviewees include associations’ leaders, members, administrators, and officials from the three countries and China in order to understand their perspectives on engaging Chinese businesses in the region. There were 31 key informants interviewed, including 7 from Singapore, 11 from Malaysia, 10 from the Philippines and 3 from China. For participant observations, we attended formal events (e.g. BRI commercial exhibitions, monthly meetings of the associations, and receptions for Chinese delegations) and informal activities (e.g. social gatherings relating to Chinese business).

New structural characteristics of ethnic Chinese business communities

There are three types of Chinese business associations based on their different structures. One is the federated business associations such as the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SCCCI), the Federation of Filipino Chinese Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FFCCCII), and the Associated Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia (ACCCIM). They are the large umbrella organisations, representing Chinese business communities in the local society and have tens or hundreds of affiliated organisational members. The second type of is regional associations, which are named after the locality where they were set up and spread out nation-wide, such as the Cebu Fil-Chinese Chamber of Commerce in the Philippines and the Malacca Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Malaysia. The third type of associations is classified by different sectors of commerce and industry, such as the Lumber Merchants Association in the Philippines, and the Selangor Chinese Engineering Association in Malaysia. As they are mainly concerned with domestic affairs in a specific industry rather than transnational engagement, this paper does not include them.

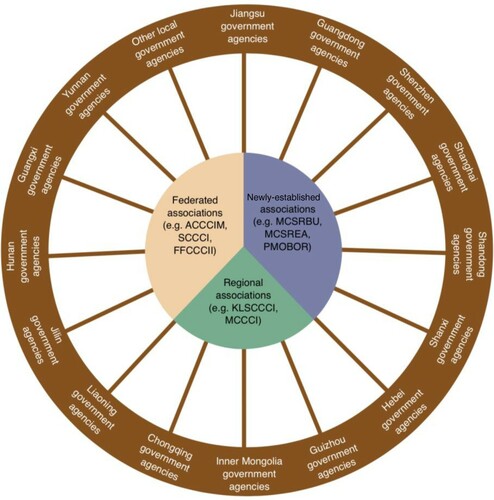

BRI’s inroads into Southeast Asia and the growing opportunities presented by a rising China have led to three different patterns of responses from the Chinese business communities: the reorganisation of existing business associations, the formation of new BRI-specific associations, and the creation of new regional business associations ().

Table 1. New structural characteristics of ethnic Chinese business associations.

First, business associations set up sub-committees specifically to grab the opportunities afforded by the increasing economic connections with China. The ACCCIM established in 2014 the Malaysia-China Economic Trading and Investment Committee, International Exposition Team and the Task Force on China Investment in Malaysia to further enhance the mutual relations in trade and investment. As one of the five constitutes chambers of the National Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia (NCCIM), the ACCCIM in 2016 founded the Belt and Road Committee in NCCIM to coordinate BRI-related projects. Similarly, the FFCCCII leadership emphasised that it could provide consultation services for enterprises from China seeking to invest in the Philippines, through a planned special committee.

Second, BRI-specific business associations and affiliated agencies were newly established to promote and coordinate the BRI projects. These associations consist of local entrepreneurs who already have investment or intend to invest in China. Its membership is mostly ethnic Chinese, like the Malaysia China Silk Route Business Chamber (MCSRBC)and the Malaysia-China Silk Road Entrepreneurs Association (MCSREA), although some are multi-ethnic. For example, Persatuan Muafakat One Belt One Road (PMOBOR) was founded in 2016 in Malaysia, with multi-ethnic members including Malays and Indians. However, two vice presidents and secretary-general are all ethnic Chinese, who account for half of the committee members (PMOBOR website). The Singapore Business Federation (SBF), a multi-ethnic business federation but with a majority Chinese composition in membership and leadership, set up in 2016 a BRI Portal jointly with the Lianhe Zaobao, an influential Chinese newspaper. The web portal (beltandroad.zaobao.com/beltandroad) has Chinese and English versions, providing one-stop business service and other information pertaining to the BRI in ASEAN. The Philippine Silk Road International Chamber of Commerce (PSRICC) was established in 2016 and 90% of its members are ethnic Chinese. Although these associations were established only recently, they have developed fast. The MCSRBC membership expanded to about 800 in two years (Liang Citation2017).

Third, new modes of regional business organisations have been created in response to economic interactions between Southeast Asia and specific regions in China. They included the Singapore Guangdong Enterprise Association (focusing on business links with Guangdong), and the Malaysian Shamchun Chamber of Commerce (aiming to promote the relationship between Malaysia and Shenzhen). These associations are mostly made up of entrepreneurs originating from, or having business ties with, specific regions in China.

Since the 1980s a large number of new Chinese immigrants have come to Southeast Asia. Coming from places that are different from the older generation of immigrants, they established their own business associations to tap on rising opportunities from commercial linkages between the host countries and their places of origin. They are usually named after the provinces they originate from, such as the Malaysia Shandong Community, Philippine Hunan Chamber of Commerce, and Singapore Jin Business Club (Jin refers to Shanxi province).

Chinese business associations have been shaped by their leadership in terms of business concentrations, socio-political backgrounds, and global exposure. Ong Tee Keat, the MCSRBC’s founder and director of several companies, served as Malaysia’s Transport Minister and Deputy Parliament Speaker. The founding of MCSRBC is attributed to Ong’s background in business and politics as well as his transnational vision and activities. According to him, ‘To establish the organisation, it took me one year and a half to do the preparations, including recruiting members and liaising with China’. Similarly, Teo Siong Seng, the SBF chairman from 2014 to 2020, is the Managing Director of Pacific International Lines, whose business is across Asia, Europe, the Americas, and Africa. He is an honorary president of the SCCCI and served as a Nominated Member of Parliament of Singapore. Teo’s global entrepreneurial exposure and local political experience facilitated the launch of the joint BRI portal and BRI-related activities such as BRI forums and regular surveys on economic opportunities brought about by China.

The emergence of the new structural characteristics demonstrates the increasing interactions between ethnic Chinese business communities and China. While traditional associations were reinvigorated with the new dynamics, the creation of business associations contributed to the organisational restructuring of the Chinese communities. Collectively, they form the backbone of organised transnational networks that transcend the national boundaries.

Dynamics of organised transnational networks

Diaspora business associations’ deepened interaction with China has been driven by historical and current transnational forces in the macro context, including their extensive linkages, and growing economic relations between China and ASEAN (both as a collective entity and individual members). Furthermore, the pull and push factors exerted by the states of China and Southeast Asia constitute another vital driving force behind the emergent transnational networks.

The macro context

Extensive social and business networks between Southeast Asian Chinese business associations and China emerged after the late nineteenth century, when the Qing dynasty began courting wealthy overseas Chinese for support, leading to the establishment of business associations such as the SCCCI. After China’s reform and opening-up in 1978, business associations in Southeast Asia were among the first organisations to restore contacts with China. These long-standing socio-economic linkages served as a foundation for the present networks (Liu Citation1998; Li and Chan Citation2018).

Growing China-ASEAN trade, economic and social ties have deepened significantly since the commencement of the ASEAN-China Dialogue Relations in 1991. The formation of the China–ASEAN Free Trade Area in 2010 created an economic entity with a combined GDP of $6.6 trillion, 1.9 billion people and a total trade of $4.3 trillion. By 2020 China had become the largest trading partner of ASEAN for eleven consecutive years, while ASEAN replaced the EU to become China’s largest trade partner since early 2020 (State Council of the PRC Citation2020). Chinese FDI to ASEAN countries doubled between 2013 and 2018, to $14 billion (Liu Citation2022a). Against this backdrop, multi-layered transnational flows of capital, goods, ideas and people have increased in both pace and intensity through governmental and societal institutionalised channels, such as the China-ASEAN Exposition and the China-Southeast Asia High-Level People-to-People Dialogue.

The intra-regional connectivity, the core of the BRI, has been further facilitated by technological and transportation advancement. There were about 600 weekly commercial flights between Singapore and different cities in China prior to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, while the Philippine Airlines increased the number of flights to more than 120 weekly between Manila and major Chinese cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Xiamen.

Enter the state

One of the main criticisms against transnationalism is that its neglection of the state (e.g. Waldinger Citation2015). Our case demonstrates that the state has indeed played a significant part in shaping the operations and outcomes of institutionalised transnationalism, and in this process, the state has deeply and structurally connected with the diaspora networks as the ‘networked state’ (Liu Citation2018; Liu, Fan, and Lim Citation2021).

The states in China and Southeast Asia, respectively, have their own agendas and interests in engaging transnationalism. On the part of China, diaspora is considered as an asset in promoting economic globalisation (such as FDI and businesses going abroad, embodied by the BRI) and enhancing the country’s political ambitions (the revitalisation of the Chinese nation and territory unification). Chinese President Xi Jinping spoke on various occasions that diaspora Chinese have advantages in capital, technologies, and local networks, allowing them to contribute to cooperation between China and foreign countries (ACFROC Citation2018). The ‘Action Plan for the Belt and Road Initiative’, prepared jointly by the National Commission for Development and Reform, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce, underscored the need to ‘leverage the unique role of overseas Chinese and the Hong Kong and Macao Special Administrative Regions, and encourage them to participate in and contribute to the BRI’ (State Council of the PRC Citation2015).

The Southeast Asian governments supported their ethnic Chinese business communities’ economic linkages with China to advance their own national interests. The Malaysian politicians (especially during the premiership of Najib Razak from 2009 to 2018) indicated that the Chinese business community and its organisations were irreplaceable partners and could help boost bilateral trade. Rodrigo Duterte, the president of the Philippines, praised Chinese business associations for their support in taxation, anti-drugs, and employment and commended Chinese associations for forging stronger economic ties between the Philippines and the neighbouring countries (Philippine Chaoshan Chamber of Commerce Citation2017). In launching the Global Hua Yuan Collaborative Network organised in 2016 by a new migrant association, Minister Chan Chun Sing applauded that ‘such networks by Chinese community groups can play a new role in connecting Singapore with the rest of the world’ (Leong Citation2016).

Besides such public endorsements, the states facilitated the institutionalisation of transnational networks. The Chinese government established new platforms to help ethnic Chinese’s participation in the BRI frameworks. The central government has organised the biennial Global Overseas Chinese Industrial and Commercial Convention (GOCICC) since 2015. The two previous events were attended by some 1000 participants, representing hundreds of overseas Chinese business and professional organisations from more than 100 countries. In 2017 two online platforms, the Overseas Chinese and BRI Information Releasing Platform (OCBIRP) and the Website for the Coordination of BRI Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurial Organizations (WCBOCER), were set up for diaspora Chinese entrepreneurs, involving more than 270 entrepreneurial organisations (WCBOCER Citation2020).

The Southeast Asian states’ promotion of local Chinese interaction with China through the BRI has been driven by their own agendas of taking advantage of economic opportunities presented by a rising China. Malaysia was one of the first countries to participate in the BRI framework in which the volumes of bilateral trade had exceeded US$ 100 billion (Bai Citation2019). The then Prime Minister Mahathir stated in 2019 that he was ‘fully in support of the Belt and Road Initiative’ and hoped that Malaysia ‘will benefit from the project’, while calling for ‘longer, bigger’ trains to bridge the distance between the East and the West (Liu Citation2022b). The Philippines signed in 2017 the Six-Year Development Program to boost trade with and investment from China (The Philippine Star Citation2017). Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong emphasised in 2018 that Singapore is an ‘early and strong supporter’ of the BRI (Cheong Citation2018). The government has established a set of effective institutions and mechanisms in connecting Singapore and China under the BRI fabrics which include both government agencies, the private sector, and business associations (Liu, Fan, and Lim Citation2021).

The Chinese governments dispatched a large number of delegations to strengthen linkages with diaspora business communities. According to the SCCCI’s annual reports, it received 116 Chinese delegations between 2015 and 2018. In the same period the ACCCIM hosted 125 overseas visitors and delegations, of which more than half were from China (ACCCIM Citation2018). The Malaysia-Foshan Chamber of Commerce was founded in 2016 with sponsorship by the Foshan government in Guangdong, which appointed a local contact for the association’s set-up. It is tasked with assisting Foshan enterprises in handling government-related matters concerning inbound investment to Malaysia, such as company registration, business licensing, import and export approval documents (Malaysia-Foshan Chamber of Commerce Citation2016). Duterte included representatives of Chinese business associations in his entourage in his China state visit, which was also the case of Najib’s China visits on a number of occasions.

Whilst being supportive of the local-Chinese’ interactions with China, the Southeast Asian states have taken various steps to ensure that their engagement is confined to the economic arena and not at the expenses of their national identity. As Lee Hsien Loong wrote in the Foreign Affairs in June 2020, the existence of a significant number of ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia is a politically sensitive issue, especially for Singapore:

Singapore is the only Southeast Asian country whose multiracial population is majority ethnic Chinese. In fact, it is the only sovereign state in the world with such demographics other than China itself. But Singapore has made enormous efforts to build a multiracial national identity and not a Chinese one. And it has also been extremely careful to avoid doing anything that could be misperceived as allowing itself to be used as a cat’s-paw by China. (Lee Citation2020)

The then Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean highlighted in 2018 the role of Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations (SFCCA), a consortium of more than 300 locality/kinship/business associations, to be an important bridge for Singapore: “first, a bridge between our people; second, a bridge between new and old; and third, a bridge between countries [i.e., for ‘a deep understanding of China and maintains many connections and networks in China’] (Teo Citation2018). In the 2019 National Day Rally, Lee Hsien Loong said that while having a shared culture helps foster good relations between Singapore and China, ‘even as we engage and cooperate with each other, we should always remember that we are Singaporean. We have our own history and culture, and also our own perspectives and political stands on current affairs” (Lai Citation2019).

Chinese associations have taken actions to solidify their national identity. Between 2015 and 2018 the ACCCIM participated in 334 government consultation meetings, signing 35 MOUs with state agencies, submitting 63 proposals and 10 reports to the government (ACCCIM Citation2018). Disputing the allegations by a US-funded Think Tank on China’s political influences among voluntary associations in Singapore, the SFCCA President Tan Aik Hock stressed that his organisation had taken various measures to strengthen national identity and moved away from being influenced politically by external sources (Lianhe Zaobao Citation2019). Responding to the government’s call to better integrate newcomers into the nation’ social fabric, the SFFCA set up a new Chinese Cultural Centre with an aim ‘to integrate newcomers to Singapore and showcase the local Chinese identity’. At the opening of the $110 million, 11-storey centre in 2017, the then SFCCA president Chua Thian Poh said that some Chinese values transcend race, and ‘act as pillars of support for racial harmony and social stability’ in multi-racial Singapore (Sim Citation2017). According to Carmelea Ang See, managing director of the Kaisa Heritage Foundation in the Philippines, ‘Southeast Asian Chinese are citizens of their countries first, Southeast Asians second, Chinese third’ (Strangio Citation2020, 269–270).

Driven by their own profit-seeking interests in a growing market, Southeast Asian Chinese have engaged with China through various institutional mechanisms. The entry of the states into the transnational arena and their overall supportive (albert cautious) policies have strengthened business associations’ networks with China. Reinforcing our earlier studies on ‘dual embeddedness’ in which local political integration and business transnationalism have been simultaneously pursued by diaspora Chinese associations (Ren and Liu Citation2015), business associations’ engagement with China in taking advantage of the BRI opportunities has not led to the dilution of national identity with Southeast Asia. Apart from the fact that majority of Southeast Asian Chinese are local born citizens who have well-entrenched political identification with their nations, the networked states, which have structurally connected with the diaspora networks to enhance national agendas, have played a significant role in the making of dual embeddedness and undivided national identity.

Patterns of state-centric transnational networks

There are two layers in the state-centric transnational network that connect ethnic Chinese business communities in Southeast Asia with the Chinese state. In terms of vertical representation, the top layer of the network is built in partnership with the central governmental agencies, such as China Overseas Exchange Association (COEA), All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce (ACFIC), China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT), Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council (OCAO, which has been incorporated into the United Front Work Department of CPC Central Committee since 2018), and All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese (ACFROC). In this layer of the network, the larger federated associations such as the SCCCI, FFCCCII, and ACCCIM are the most active players from Southeast Asia in mediating links are.

As the largest business organisation in Singapore, the SCCCI was regarded as one of the undisputed leaders in the Chinese community before independence in 1965 (Liu Citation1998). Presently it has 156 organisational members, which account for nearly half of the total 300 business associations in Singapore. The FFCCCII was founded in 1954 and has 155 member organisations from 14 regions, representing Chinese companies, entrepreneurs, and business associations in the Philippines. Founded in 1921, the ACCCIM is similarly the oldest and largest national organisation of Chinese chambers of commerce and industry in Malaysia, with 17 constituent chambers located in 13 states and over 100,000 members.

Endowed with substantial historical capital, economic resources, and organisational capacity, these federated or central associations have not only served as effective intermediaries to communicate with the local governments in representing the voices of Chinese merchants but have collected and disseminated information from international counterparts. In the business community’s interaction with the Chinese central government, these associations act as the prioritised interlocutors.

Beneath the top-layer network which typically involves a small number of the federated pinnacle organisations, the next layer is formed with the local government agencies in China by a large number of associations, displaying two major structures in its operation.

The ‘axis-spoke’ pattern () denotes the mode whereby the associations (‘axis’) build self-centric transnational networks with multiple local government agencies from different provinces (the ‘spokes’), with the federated associations and newly established associations serving as the main actors. The axis-spoke network pattern has flourished largely because of the BRI’s advancement in Southeast Asia. China’s ‘going-out’ policy has pushed more local government agencies to overseas to build connections with diaspora Chinese, which dovetails with Chinese business-people’s search for economic opportunities.

The ‘axis-spoke’ pattern of the network is reflective by the ACCCIM and Malaysia-China Chamber of Commerce (MCCC)’s activities. From 2015 to 2018, ACCCIM received 125 foreign delegations, and about 70% are from China (mostly local governments). It organised 56 overseas business trips, with more than half going to different cities in China (ACCCIM Citation2018). In the same period, the MCCC received more than 20 Chinese delegations per month (MCCC Citation2015). Newly established associations actively participate in building networks with the Chinese governments too. The MCSRBC visited more than 10 provinces since its founding and set up branches in cities and provinces (Liang Citation2017).

The other network pattern is a linear model, in which the network is built in a one-to-one structure, with one association directing at a specific local Chinese government entity. Regional associations play an important part in this pattern constructed between associations and the relevant regions in China. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor signed a MOU with the Economy, Trade and Information Commission of Shenzhen municipality in 2016, while the Malaysia Shandong Community provides business services for Shandong enterprises doing business in Malaysia and other ASEAN countries. The Malaysia Shandong Community signed in 2018 an agreement with the Shandong provincial government, assisting the latter to set up an overseas liaison office to recruit overseas Chinese professionals.

In short, Chinese business associations in Southeast Asia vertically construct multi-layered state-centric transnational networks in different patterns, and the Chinese governments from central to local constitute the key network nodes. Through such institutionalised network, different types of business associations identify their respective counterparts, thus enhancing their transnational practices.

Transnational mechanisms

Under the fabrics of the BRI, Chinese business associations in Southeast Asia have established different patterns of networks with China. Four major mechanisms have emerged in this process, including entering into MOU agreements, building regular commercial and trading platforms, establishing collaborative mechanisms, and publishing and circulating materials on business information.

Entering into cooperative MOUs or agreements is a common mechanism in the initial stage of networking. The MOU typically states the specific measures that the two parties will undertake in the partnership, such as establishing communication platforms, exchanging trade information, and holding regular joint activities. Expectantly, the larger federated associations are usually the ones that sign the most MOUs with the Chinese governmental and commercial agencies. As of June 2018, the ACCCIM had signed 75 cooperation agreements, and more than half of them were with partners from China. The SCCCI signed MOUs with various organisations from Chongqing, Shanghai, Beijing and other Chinese cities between 2015 and 2019.

Chinese business associations built regular commercial and trading platforms in the form of commercial exhibitions, investment conventions, business investigations, economic forums and overseas workshops. lists samples of major commercial platforms organised by business associations in Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore in recent years.

Table 2. Samples of the commercial and trading platforms organised by ethnic Chinese business associations.

Some platforms consist of multiple formats of activities. As one of most comprehensive business platforms in Southeast Asia, the Malaysia-China Entrepreneur Conference (MCEC) originates from the ASEAN-CHINA partnership forum held in 2002. After nine years of preparation, the MCCC developed it into an annual event. The MCEC started in 2011 and has been held eight times (since 2014 by the MCCC and China alternately). By 2019, the MCEC had been held in China for three times, in Xiamen (2014), Chengdu (2016) and Nanjing (2018), co-organised by the local provincial and municipal agencies, including the Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export, Department of Commerce, and Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese. The number of attendants ranged from 500 to 1500 each time. The conference has been organised into multiple forms, including commercial exhibitions and economic forums. One of the highlights has been business matching sessions, which ‘aim to combine China’s technology and capital with Malaysia’s geographical advantages, resources and talents to create greater and more sustainable economic benefits’ (MCCC Citation2018, 14). At the fifth conference in 2015, contracts valuing more than US$2.3 million were signed, and the amount was increased to more than US$10 million in the subsequent conference (MCCC Citation2016; Citation2017). ‘Through eight years of development, the MCEC has become a famous brand of the MCCC and an important institutionalised platform for the enterprises from both Malaysia and China to build networks to develop new trade and investment opportunities’, MCCC vice president told us. The growing importance of technology in the collaboration not only reflects the new emphasis on the Digital Silk Road after 2019, but the intention of the Malaysian (Chinese) businesspeople in working with China in this area. Said Malaysia-China Business Council Chairman Tan Kok Wai,

China has made tremendous progress on new and pioneering technologies where we can learn so much from, especially when we are formulating plans to move forward to meet the challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and China will be an important partner to help us achieve the goal. (cited in Liu Citation2022b)

Some platforms focus only on specific activities, such as commercial exhibitions, business forums or workshops. Since 2017 the SCCCI and the Singapore government agencies have jointly organised a series of overseas market workshops and customised training courses for Singaporean enterprises and professionals. ‘These workshops are intended to provide a deeper understanding of the overseas markets, particularly in China, and to obtain specialised market knowledge, establish networks, and help their companies in their internationalisation efforts’ (SCCCI Citation2017, 61). The 11 overseas workshops in 2017 and 2018 covered topics such as the trends of smart industry, the development of the food catering industry, and the mindsets of the new Chinese economy. These workshops usually last one week and are held in different cities, including Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing and Qingdao. The workshop participants were arranged to visit local key enterprises and meet with local entrepreneurs and officials.

Establishing transnational collaborative mechanisms is another channel to facilitate Chinese associations’ interactions with China. In 2015 the ACCCIM set up joint working platforms with the Department of Commerce of Guangdong Province to co-organise annual key projects relating to the BRI (ACCCIM Citation2015). The MCCC has been appointed since 2014 as the Guangdong Tourism Cooperation and Promotion Centre in Malaysia and by the Chengdu Overseas Exchange Association as its Overseas Liaison Office. Similarly, the Singapore Tianfu Business Association cooperates with the Chengdu municipal government to function as its Singapore representative office. In the meantime, the SCCCI set up overseas representative offices in Shanghai (in 2012) and in Chongqing (in 2017) for the purposes of assisting Singaporean companies in China while attracting Chinese companies to venture into Southeast Asia through Singapore. In 2018 the Shanghai representative office provided consultancy services to 352 Singaporean companies and organised 10 forums, seminars and networking events in Singapore and China, with a total of 1281 Singaporean companies participated in them (SCCCI Citation2018).

Transnational flow of information is an integral component of institutionalised transnationalism. Some larger and well-financed associations build information networks by publishing and circulating business information, such as the Chinese Enterprise published by the SCCCI, Federation Today by the FFCCCII, and ACCCIM Bulletin by the ACCCIM, and Malaysia-China Business Magazine by the MCCC. All these periodicals are bilingual (Chinese and English) and published 4–6 issues annually. Pertaining to the contents, every publication has its own focus and readership. Chinese Enterprise focuses on economic and trade topics such as the local and regional economy, business information, and new government regulations. Besides the chambers’ members, the publications are distributed to government departments, local business organisations, and foreign embassies in Singapore. Since 2015 the magazine has been available online, contributing further to the circulation of business intelligence overseas, especially in Greater China.

As the only magazine in Malaysia that concentrates on Malaysia-China economic cooperation, the Malaysia-China Business Magazine’s contents have developed from covering only the Association’s activities in the early days to an inclusive magazine pertaining to bilateral trade, investment, manufacturing, finance, agriculture, tourism and legal consultation. An interviewee told us, ‘the magazine is free to give out and mainly circulates in Malaysia and China. Each issue of the magazine has 20,000 copies and about 25% of them are distributed in China, mainly for the government agencies and industrial and commercial organisations’.

Through the above four major mechanisms centred in ethnic Chinese business associations, which supplement the government-to-government collaboration on the BRI (e.g. Liu, Tan, and Lim Citation2022), the states from China and Southeast Asia have played an active role as initiator, partner or collaborator in the making of the associations’ transnational networks, which form the core of the institutionalised state-centric transnationalism. This transnationalism is state-centric, also because the Southeast Asian governments have taken various policy measures to ensure their ethnic Chinese citizens’ political loyalty and national identity firmly rest with the countries of their residence, not their (ancestral) homeland.

Conclusion

Since the BRI’s launch in 2013, Chinese business associations in Southeast Asia have strived to tap on the huge economic opportunities by engaging with respective governmental agencies in China through establishing, renewing, or enhancing transnational networks. They have played a prominent role due to their historical capital and continuing economic influences, thus facilitating the dynamic emergence of new structural characteristics to accommodate the growing economic opportunities. Not only have traditional organisations been revitalised, but also have more business associations been newly created. A rising China and the BRI serve as a conducive external impetus for internal restructuring of ethnic Chinese organisations, highlighting the interconnectedness between the transnational and national.

These associations have constructed intensive and institutionalised transnationalism through a series of mechanisms. Driven by their respective national agendas but also seeking to maximise the mutual interests, the states in ASEAN and China have played significant roles in facilitating the development of transnational linkages. The networked states have not only acted as initiators and promoters of ethnic Chinese associations’ transnationalism, but the Chinese governments have entered into the structure of the transnational networks as connective nodes.

Our analysis furthers the existing discussion on the relationship between the state and transnationalism and demonstrates their structural interdependence, in which not only can states coordinate in tandem with ethnic transnational forces, but also integrate into the transnational process through the adjustment of states’ roles in globalisation. The new data in the context of the BRI presented in this paper also reinforce our earlier argument that Chinese diaspora transnationalism has operated within a ‘dual embeddedness’ structure in which the state is involved in the transnational field with diasporic organisations serving as a bridge between individual migrants and state actors in transnational practices and integration processes (Ren and Liu Citation2015; Zhou and Liu Citation2016; Liu 2018). Collectively, these studies point to the indispensable roles of institutionalised transnationalism and networked states in a new understanding of the changing dynamics of global diaspora and their linkages with the (ancestral) homeland.

Furthermore, a rising China has significant ramifications for the ethnic and national identities of Southeast Asian Chinese. Economic transnationalism does reinforce ethnic Chinese cultural affinity to China and may lead to fluid identity, thus amplifying ethnic elements in the national political economy. This in turn presents ethnic Chinese in the region with complex challenges, such as how to balance their political identity with ethnic identity (e.g. Liu Citation2016; Ching Citation2016; Strangio Citation2020). How they perform a (precarious) balancing act between transnational engagement and national identity is another key issue worthy of further explorations. Our essay emphasises that business associations have formed institutionalised transnational interaction with China by way of cross-border flowing of people, goods, capital, information and practices. In the meantime, we argue that these associations are keenly aware of the divide – however blurring it might be–between economic connections with China as a huge market and the political loyalty to their respective countries where they were born or had been naturalised. This positioning has been further strengthened by the respective governments’ effort in buttressing their citizens’ undivided political identity. There is no evidence showing that national identity has been compromised for economic gains, though this cannot be taken for granted as a fixed modality.

In the final analysis, ethnic Chinese business associations have constructed multi-layered and diverse transnational networks over the past years. They have served as an intermedium to bridge the Southeast Asian region with China in trade and investment activities. The formation of institutionalised transnationalism, therefore, calls for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the entanglement of Chinese ethnicity, state and transnationalism at a time of China rising and emerging new regional order within which diaspora is an indispensable force with their own aspirations, identities and agendas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACCCIM. 2018. “ACCCIM Brainstorming Workshop.” ACCCIM Bulletin 115 (5): 1–5.

- ACCCIM (Associated Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia). 2015. “Establishment of Joint Collaboration Between ACCCIM and Department of Commerce of Guangdong Province.” ACCCIM Bulletin 95 (2): 29.

- ACFROC (All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese). 2018. “The Reform and Innovation of the ACFROC in the New Era: An In-depth Study and Implementation of Xi Jinping’s Important Exposition on Overseas Chinese Affairs”. http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0817/c40531-30235809.html.

- Bai, Tian. 2019. “Ambassador’s View: Performing the Symphony of Mutual Learning and Common Prosperity of Civilizations.” The People’s Daily, May 3. http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2019/0503/c40531-31061964.html.

- Caggiano, Sergio. 2018. “Blood Ties: Migration, State Transnationalism and Automatic Nationality.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (2): 267–284.

- Cheong, Danson. 2018. “Belt and Road Initiative a Focal Point for Singapore’s Ties with China”. Straits Times April 8.

- Chin, Ku Sup, and David Smith. 2015. “A Reconceptualization of State Transnationalism: South Korea as an Illustrative Case.” Global Networks 15 (1): 78–98.

- Ching, Frank. 2016. Beijing Seeks Loyalty from Ethnic Chinese Settled Abroad. Business Times. May 4.

- CIMB Southeast Asia Research Institute. 2018. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur: CIMB Southeast Asia Research Sdn Bhd.

- Flinta, Colin, and Cuiping Zhu. 2019. “The Geopolitics of Connectivity, Cooperation, and Hegemonic Competition: The Belt and Road Initiative.” Geoforum 99: 95–101.

- Gao, Jia. 2022. “Riding the Waves of Transformation in the Asia-Pacific: Chinese Migration to Australia Since the Late 1980s.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (4): 933–950. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1983955.

- Gomez, Terence E., and Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao. 2013. Chinese Business in Southeast Asia: Contesting Cultural Explanations, Researching Entrepreneurship. Oxon: Routledge.

- Guo, Shibao. 2022. “Reimagining Chinese Diasporas in a Transnational World: Toward a New Research Agenda.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (4): 847–872. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1983958.

- Koser, Khalid. 2007. “Refugees, Transnationalism and the State.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (2): 233–254.

- Kunming Daily. 2018. “The 16th ASEAN Overseas Chinese Entrepreneur Conference opened in Kunming and signed 5 Projects Valuing CNY 2.62 billion.” June 13. http://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1603144809841921032&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- Kunming Daily. 2019. “The 16th ASEAN Overseas Chinese Entrepreneur Conference Will Be Held Next Week.” June 6. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1635588409945959870&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- Lai, Linetter. 2019. “National Day Rally 2019: Singapore Wants to Remain Good Friends with US, China; Must Always Be Principled in Approach, Says PM Lee.” Straits Times, August 18.

- Lamba-Nieves, Deepak. 2018. “Hometown Associations and the Micropolitics of Transnational Community Development.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (5): 754–772.

- Lampert, Ben. 2014. “Collective Transnational Power and its Limits: London-Based Nigerian Organizations, Development at ‘Home’ and the Importance of Local Agency and the ‘Internal Diaspora’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (5): 829–846.

- Lee, Hsien Loong. 2020. “The Endangered Asian Century: America, China, and the Perils of Confrontation.” Foreign Affairs 99 (4): 52–64.

- Leong, Weng Kam. 2016. “Chinese Networks Can Play Wider Role: Chun Sing.” Straits Times, November 21.

- Li, T. E., and E. T. H. Chan. 2018. “Connotations of Ancestral Home: An Exploration of Place Attachment by Multiple Generations of Chinese Diaspora.” Population, Space and Place 24 (8): e2147.

- Li, P. S., and E. X. Li. 2013. “The Chinese Overseas Population.” In Routledge Handbook of the Chinese Diaspora, edited by Chee-Beng Tan, 31–44. Oxon: Routledge.

- Liang, Jieying. 2017. “Chairman Tan Sri Ong Tee Keat: Entrepreneurs Between Malaysia and China, Open Up New Routes.” Business Century 7: 12–13.

- Lianhe Zaobao. 2019. “US Think Tank Alleged That the Communist Party of China Is Influencing the Singapore Public Opinions Through Local Chinese Community, and the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations refute the allegation.” July 19.

- Liow, Joseph, Hong Liu, and Xue Gong. 2021. Research Handbook on the Belt and Road Initiative. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Liu, Hong. 1998. “Old Linkages, New Networks: The Globalization of Overseas Chinese Voluntary Associations and Its Implications.” The China Quarterly 155: 582–609.

- Liu, Hong. 2016. “Opportunities and Anxieties for the Chinese Diaspora in Southeast Asia.” Current History 115 (784): 312–318.

- Liu, Hong. 2018. “Transnational Asia and Regional Networks: Toward a New Political Economy of East Asia.” East Asian Community Review 1 (1): 33–47.

- Liu, Hong. 2022a. The Political Economy of Transnational Governance: China and Southeast Asia in the 21st Century. London: Routledge.

- Liu, Hong. 2022b. “Beyond Strategic Hedging: Mahathir’s China Policy and the Changing Political Economy in Malaysia, 2018–2020.” In Asian Geopolitics and the US-China Rivalry, edited by Felix Heiduk, 159–176. London: Routledge.

- Liu, Hong, Xin Fan, and Guanie Lim. 2021. “Singapore Engages the Belt and Road Initiative: Perceptions, Policies, and Institutions.” The Singapore Economic Review 66 (1): 219–241.

- Liu, Hong, Kong Yam Tan, and Guanie Lim. 2022. The Political Economy of Regionalism, Trade, and Infrastructure: Southeast Asia and the Belt and Road Initiative in a New Era. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

- Long, Dengao, and Li Yiwei. 2018. “Forty Years of Overseas Chinese Investment in China: Development, Implications, and Trends.” Huaqiao Huaren Lishi Yanjiu [Overseas Chinese History Studies] 4: 1–13.

- Malaysia-Foshan Chamber of Commerce. 2016. “Introduction.” http://www.mfcc.my/introduction/Malaysia Shandong Community. 2013. “Introduction.” http://www.masshandong.com/index.php?m=text&a=index&classify_id=367.

- Margheritis, Ana. 2007. “State-led Transnationalism and Migration: Reaching Out to the Argentine Community in Spain.” Global Networks 7 (1): 87–106.

- Martínez-Zarzoso, I., and R. Rudolf. 2020. “The Trade Facilitation Impact of the Chinese Diaspora.” The World Economy 43 (9): 2411–2436.

- MCCC (Malaysia-China Chamber of Commerce). 2015. “The 25th Anniversary of the MCCC.” Malaysia-China Business Magazine 55: 50.

- MCCC (Malaysia-China Chamber of Commerce). 2016. “Thousands of Entrepreneurs Attend the 5th MCEC, New Developments in Malaysia-China Business.” Malaysia-China Business Magazine 56: 3–7.

- MCCC (Malaysia-China Chamber of Commerce). 2017. “Introduction of the 7th MCEC.” Malaysia-China Business Magazine 63: 34–36.

- MCCC (Malaysia-China Chamber of Commerce). 2018. The 7th Malaysia-China Entrepreneur Conference Souvenir Book. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysia-China Chamber of Commerce.

- Moya, Jose C. 2005. “Immigrants and Associations: A Global and Historical Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (5): 833–864.

- Mügge, L. M. 2011. “Diversity in Transnationalism: Surinamese Organizational Networks.” International Migration 49: 52–75.

- Park, Yoon Jung. 2022. “Forever Foreign? Is There A Future for Chinese People in Africa?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (4): 894–912. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1983953.

- Peterson, G. 2013. Overseas Chinese in the People’s Republic of China. Oxon: Routledge.

- Philippine Chaoshan Chamber of Commerce. 2017. “The Establishment Ceremony of the Philippines Chaoshan Chamber of Commerce.” https://www.sohu.com/a/164534161_698126.

- Philippine Star. 2017. “Phl, China Sign Joint Dev’t Plan.” March 19. PMOBOR (Persatuan Muafakat One Belt One Road) website. http://obor.my/en/home/.

- Portes, A., Cristina Escobar, and Alexandria Radford. 2007. “Immigrant Transnational Organizations and Development: A Comparative Study.” International Migration Review 41 (1): 242–281.

- Portes, A., and P. Fernández-Kelly. 2016. The State and the Grassroots: Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Priebe, J., and R. Rudolf. 2015. “Does the Chinese Diaspora Speed Up Growth in Host Countries?” World Development 76: 249–262.

- Ren, Na, and Hong Liu. 2015. “Traversing Between Transnationalism and Integration: Dual Embeddedness of New Chinese Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Singapore.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 24 (3): 298–326.

- Ren, Na, and Hong Liu. 2019. “Domesticating ‘Transnational Cultural Capital’: The Chinese State and Diasporic Technopreneur Returnees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (3): 2308–2327.

- Santasombat, Yos. 2017. Chinese Capitalism in Southeast Asia: Culture and Practices. Singapore: Springer.

- SCCCI (Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry). 2015. “SCCCI Shanghai Representative Office-IE-SCCCI Singapore Enterprise Centre.” SCCCI Annual Report, 130.

- SCCCI (Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry). 2017. “Introducing New Overseas Market Workshops.” SCCCI Annual Report, 61.

- SCCCI (Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry). 2018. “Singapore Enterprise Centre @ Shanghai (SEC).” SCCCI Annual Report, 82.

- Sim, Royston. 2017. “New Chinese Cultural Centre Essential to Singapore’s Success, Says K. Shanmugam.” Straits Times, January 30.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2015. “Action Plan on the Belt and Road Initiative.” http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/publications/2015/03/30/content_281475080249035.htm.

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2020. “ASEAN Has Become the Largest Trade Partner of China.” http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-07/15/content_5527163.htm.

- Strangio, S. 2020. In the Dragon’s Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese Century. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Teo, Chee Hean. 2018. “Speech by DPM and Coordinating Minister for National Security, Teo Chee Hean, at the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations 16th Council investiture ceremony on 7 October 2018.” https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/dpm-teo-chee-hean-singapore-federation-chinese-clan-associations-16th-council.

- Waldinger, Roger. 2015. The Cross-Border Connection: Immigrants, Emigrants, and Their Homelands. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- WCBOCER (Website for the Coordination of BRI Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurial Organizations). 2020. http://www.chinaqw.com/zhwh2012/index.shtml.

- Weeks, Gregory, and John Weeks. 2015. “Immigration and Transnationalism: Rethinking the Role of the State in Latin America.” International Migration 53 (5): 122–134.

- Wu, Jinting. 2022. “A Hierarchy of Aspirations Within a Field of Educational Possibilities: The Futures of Chinese Immigrants in Luxembourg.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (4): 951–968. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1983956.

- Zhou, Min. 2017. Contemporary Chinese Diasporas. Singapore: Springer.

- Zhou, Min, and Hong Liu. 2016. “Homeland Engagement and Host-Society Integration: A Comparative Study of New Chinese Immigrants in the United States and Singapore.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 57 (1–2): 30–52.